1. Introduction

The discovery of the universe’s accelerated expansion from Type Ia supernovae observations [

1,

2] has profoundly challenged our understanding of cosmological dynamics. In the

CDM model, this acceleration is ascribed to a cosmological constant

, representing a uniform vacuum energy density with equation of state

. Despite its empirical success, this model suffers from serious theoretical limitations. Notably, quantum field theory estimates of vacuum energy exceed the observed value by over 120 orders of magnitude [

3], and the coincidence of

and matter energy densities today remains unexplained.

Many proposed alternatives attempt to replace or supplement with dynamic components such as scalar fields (quintessence, k-essence), modified gravity, or topological defects. However, these models often rely on arbitrarily introduced fields, tuned potentials, or scale-dependent modifications to general relativity, and frequently lack grounding in a deeper geometric or ontological framework.

This paper investigates a novel solution to the dark energy problem rooted in the geometry of time itself. We work within the framework of Chronon Field Theory (CFT), a field-theoretic paradigm in which time is modeled as a dynamical, unit-norm, future-directed vector field . This field defines a preferred local temporal direction, induces causal structure, and underpins emergent spacetime geometry. Within this formulation, physical interactions correspond to deformations of the Chronon field’s alignment and topology.

A key implication of this approach is that spontaneous alignment of in the early universe generically gives rise to metastable domain walls—topological defects that interpolate between distinct temporal orientations. These walls possess tension and contribute a residual, slowly redshifting energy density with effective negative pressure. We propose that this residual stress provides a natural and minimal explanation for late-time cosmic acceleration, obviating the need for a cosmological constant.

Focusing on this mechanism, we (i) develop the minimal formalism of CFT needed to model temporal topology and stress; (ii) derive modified Friedmann equations incorporating the Chronon stress-energy tensor; (iii) analyze the cosmological evolution of domain wall energy and its role in driving acceleration; and (iv) corroborate these results with a numerical simulation of Chronon field dynamics.

The structure of this paper is as follows.

Section 3 introduces the foundational structure of Chronon Field Theory.

Section 4 formalizes the domain wall energy-momentum contribution. In

Section 5, we derive the Chronon-modified Friedmann equations, and

Section 6 explores their late-time behavior.

Section 7 presents numerical simulations validating the theoretical predictions.

Section 9 discusses implications and outlines avenues for empirical testing and theoretical development.

2. Theoretical Context

Building on the motivation presented in the Introduction, this section situates our approach within the landscape of theoretical models developed to explain late-time cosmic acceleration. While the standard

CDM model attributes acceleration to a constant vacuum energy term

with

, this explanation faces enduring challenges such as the fine-tuning and coincidence problems [

3,

4].

Dynamical models such as quintessence [

5], k-essence [

6], and modified gravity theories [

7] offer alternative explanations by introducing additional fields or degrees of freedom. However, these models often lack natural embedding in a fundamental spacetime structure and may rely on finely-tuned potentials or parameter choices. Topological defect scenarios, including frustrated domain wall networks, have also been proposed as dark energy candidates, producing effective equations of state

with slowly redshifting energy densities [

8,

9,

10].

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) introduces a qualitatively different perspective by treating time itself as a physical, vectorial field

that encodes causal structure and temporal flow. Rooted in time-as-field frameworks [

11,

12], CFT connects naturally to approaches that seek emergent gravity and thermodynamic interpretations of spacetime [

43,

55]. Unlike scalar or tensor fields introduced ad hoc, the Chronon field emerges from an ontological commitment to time as a dynamical, orientable quantity.

This temporal ontology leads to spontaneous alignment of in the early universe, resulting in metastable domain walls whose residual stress-energy behaves as an effective, slowly redshifting vacuum energy. These defects offer a geometric origin for dark energy, distinct from scalar potentials or cosmological constants, and predict specific redshift evolution testable by current observations.

In what follows, we elaborate the mathematical formalism and cosmological implications of this scenario, providing analytic and numerical support for the viability of CFT as a dark energy model.

3. Chronon Field Theory: A Primer

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) is a field-theoretic framework in which time is modeled as a dynamical physical entity, represented by a smooth, unit-norm, future-directed timelike vector field

on spacetime [

11,

12]. Unlike standard approaches that treat time as a coordinate or background parameter, CFT posits that causal structure, metric geometry, and interactions arise from the internal dynamics and topology of this vector field. This section reviews the foundational elements of CFT necessary to understand its cosmological applications, particularly its capacity to explain dark energy as a geometric phenomenon.

3.1. Definition of the Chronon Field

We postulate as fundamental a smooth, globally defined, future-directed, unit-norm timelike vector field

on a differentiable Lorentzian manifold

of signature

:

These conditions ensure that

defines a consistent temporal orientation and proper time direction without presupposing a background metric [

37,

44]. The field

thus plays a dual role: operationalizing the flow of time and dynamically generating causal structure.

Physically, encodes the local direction of time experienced by comoving observers. The future-directed constraint explicitly breaks time-reversal symmetry and selects a global arrow of time. Integral curves of define observer worldlines, and the field’s topological and differential structure underpins the emergent spacetime framework of CFT.

3.2. Foliation via Frobenius Theorem

A global foliation of

into spacelike hypersurfaces

orthogonal to

exists if and only if

satisfies the Frobenius integrability condition [

63]:

which is equivalent to vanishing twist tensor:

where the spatial projector is defined as

.

When this condition holds,

is hypersurface-orthogonal and admits a scalar potential

such that:

where

is a lapse function ensuring unit normalization [

39]. The level sets

form a smooth foliation by spacelike 3-surfaces. These surfaces provide a canonical notion of simultaneity and enable Cauchy evolution in a globally hyperbolic setting.

3.3. Induced Geometry and Chronon Dynamics

The effective metric induced by

is constructed via:

This formulation provides a spatial geometry on each hypersurface

, with

and

. The emergent spacetime structure supports local curvature, causal cones, and geodesics defined with respect to

, though these need not coincide with metric geodesics in a fundamental sense [

18,

39].

The dynamics of

are governed by a diffeomorphism-invariant action incorporating antisymmetric field strength

, divergence terms, and curvature from the induced foliation:

where

denotes the Ricci scalar constructed via Gauss-Codazzi formalism from the projected connection on

, and

is a Lagrange multiplier enforcing the unit-norm constraint [

41,

68]. An alternative generic second-order action is:

where

V encodes higher-order self-interaction or topological terms such as helicity, shear, or domain wall tension [

19,

37].

The Euler–Lagrange equations derived from these actions yield field equations of the form:

subject to the normalization constraint and boundary conditions. These equations generalize Einstein-like dynamics and encode the influence of topological and foliation-induced structures in CFT.

4. Topological Stress and Domain Walls

In conventional field theories, domain wall formation has been rigorously analyzed as a consequence of spontaneous symmetry breaking in scalar fields with discrete or periodic vacuum manifolds [

9,

10]. These models yield well-understood solitonic profiles, localized stress-energy, and redshifting behavior relevant to cosmological dynamics. Chronon Field Theory (CFT) inherits the mathematical structure of such domain walls through a sine-Gordon-type dynamics for a local misalignment angle

, but introduces a novel ontological framework: here, domain walls arise not from matter fields but from the spontaneous alignment of a future-directed, unit-norm timelike vector field

, which encodes the temporal structure of spacetime itself. As a result, the resulting topological defects are embedded within a dynamically emergent foliation and causal geometry. This section rigorously derives the formation, structure, and cosmological consequences of Chronon domain walls as solitonic interpolations in temporal alignment.

4.1. Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and Temporal Phase

The configuration space of is the unit hyperboloid of future-directed timelike vectors. During a symmetry-breaking phase transition, local minimization of an effective potential leads to spontaneous alignment of within finite regions. Due to causal disconnection, different Hubble patches settle into distinct temporal alignments.

We parametrize the misalignment using a phase variable

as:

where

and

span a timelike subspace. The scalar product between two aligned regions defines the misalignment angle:

The resulting configuration minimizes gradient and potential energy, interpolating between and across a spatial layer—the domain wall.

4.2. Field Profile and Wall Tension

The effective Lagrangian for the phase field

in the direction normal to the wall is:

The static kink solution to the Euler–Lagrange equation is:

The energy per unit area—wall tension—is given by:

This quantifies the localized energy cost of temporal phase misalignment.

4.3. Stress-Energy Tensor of Domain Walls

The stress-energy tensor associated with the temporal misalignment field

is derived from the effective sine-Gordon-type Lagrangian:

From this, the stress-energy tensor is obtained via standard variational methods:

In the thin-wall approximation, where the wall is modeled as a solitonic kink localized at

, the energy-momentum tensor simplifies to:

where

is the wall tension calculated from the kink solution:

To understand the macroscopic effect, consider a statistically isotropic network of such walls with inter-wall separation

. Upon averaging over large scales, the anisotropic stresses yield a coarse-grained energy-momentum tensor:

This structure leads directly to an effective equation of state for the domain wall fluid:

This result is derived here explicitly from the microscopics of the sine-Gordon domain wall field and confirms earlier heuristic and phenomenological estimates in the literature[

9,

10]. It plays a central role in demonstrating how Chronon domain walls can source late-time cosmic acceleration without requiring a cosmological constant.

4.4. Redshifting Behavior and Scaling

Let

denote the average comoving separation between domain walls. Then:

For a frozen network,

implies:

This redshifting is slower than that of matter () or radiation (), ensuring that becomes dominant at late times.

4.5. Phenomenological Viability

Unlike conventional scalar field walls constrained by CMB data[

66], Chronon walls derive from causal structure symmetry breaking and have dynamically regulated tension. Their diffuse nature leads to suppressed gravitational imprints, reducing tension with structure formation bounds.

Numerical simulations (

Section 7) confirm that the predicted

and

behavior is consistent with late-time cosmological observations.

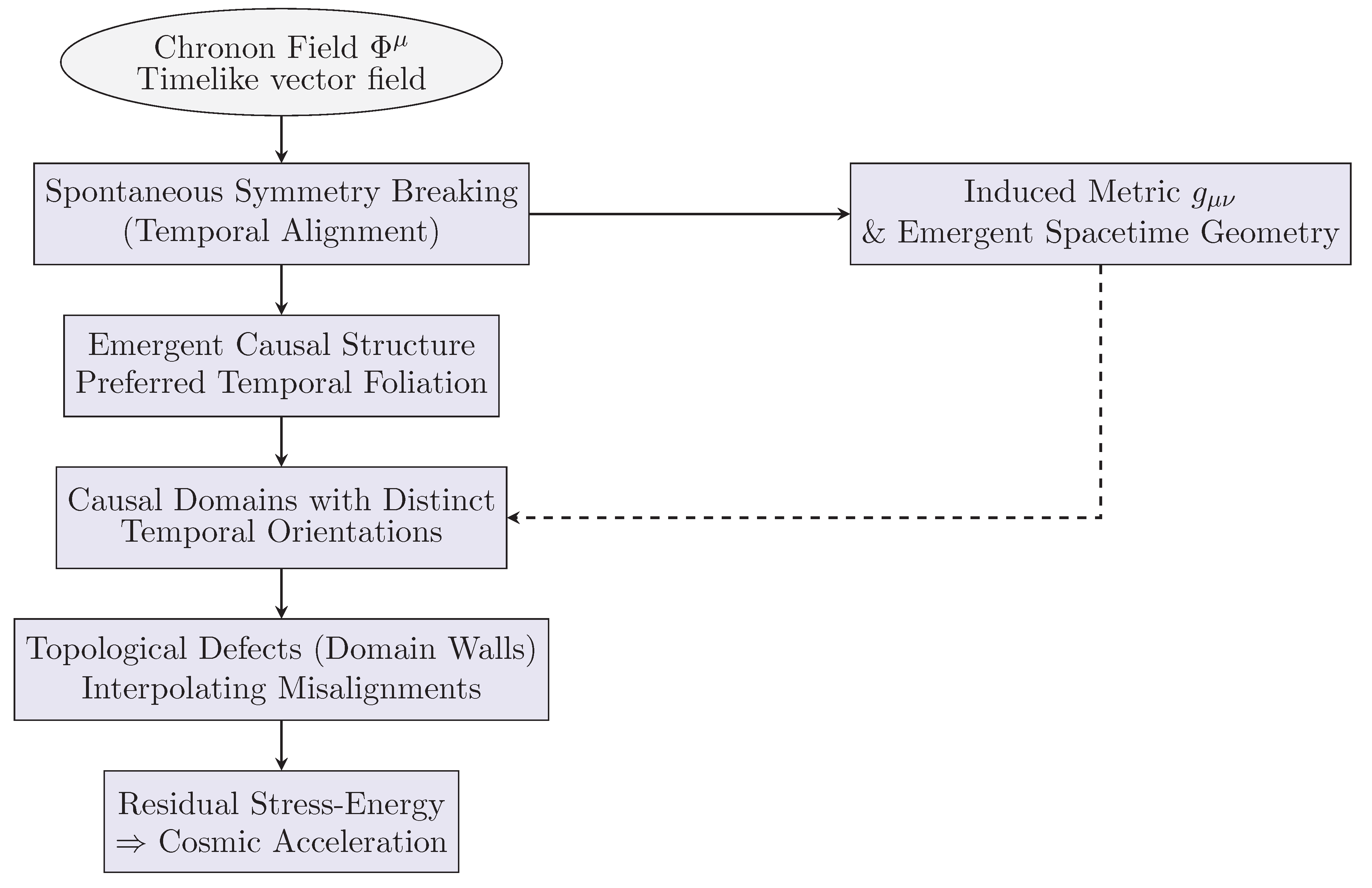

Figure 1.

Logical flow from the Chronon field to late-time cosmic acceleration. Spontaneous symmetry breaking of the temporal vector field induces a preferred foliation, metric geometry, and topological domains. The resulting domain walls contribute residual stress-energy that drives acceleration.

Figure 1.

Logical flow from the Chronon field to late-time cosmic acceleration. Spontaneous symmetry breaking of the temporal vector field induces a preferred foliation, metric geometry, and topological domains. The resulting domain walls contribute residual stress-energy that drives acceleration.

4.6. Summary

Chronon domain walls emerge as stable, solitonic interpolations between misaligned temporal regions in spacetime. Their residual stress contributes a redshifting vacuum-like energy density with , dynamically driving cosmic acceleration. These features arise from first principles in CFT, without recourse to exotic scalar fields or fine-tuned cosmological constants.

5. Modified Friedmann Equations from Chronon Geometry

In this section, we derive the modified Friedmann equations governing cosmological expansion in the presence of Chronon field domain wall stress. The derivation proceeds from the effective stress-energy tensor

, as induced by the topological domain structure of

, and is applied within a homogeneous and isotropic Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) background. We demonstrate that the resulting equations naturally give rise to late-time acceleration without invoking a cosmological constant [

1,

2].

5.1. FLRW Background and Assumptions

We assume the spacetime metric to take the standard FLRW form with spatial flatness [

65]:

where

is the cosmic scale factor.

We further assume that the Chronon field

aligns with the cosmological time direction in the homogeneous limit [

49]:

which respects the FLRW symmetries. Small deviations from this alignment encode domain wall structures and induce stress-energy contributions that act as an effective fluid with energy density

and pressure

.

5.2. Effective Energy-Momentum Tensor

In the large-scale averaged limit, the stress-energy tensor associated with the domain wall network is diagonal and isotropic [

8,

16]:

where

Here, and denote matter contributions (e.g., dust or radiation), while and arise from the domain wall stress of the Chronon field.

Using the result from domain wall averaging [

10,

21]:

we identify an effective equation of state for the domain wall component:

5.3. Chronon-Modified Friedmann Equations

Inserting the effective energy-momentum tensor into Einstein’s field equations,

yields the modified Friedmann equations [

53]:

Using

for pressureless matter and

, we obtain:

Thus, acceleration (

) occurs when:

This criterion is naturally satisfied at late times due to the slow redshifting of compared to .

5.4. Evolution of Energy Densities

The continuity equations for the two components follow from conservation of the total stress-energy tensor:

Hence, the ratio evolves as:

leading to eventual dominance of the Chronon domain wall component and a transition to cosmic acceleration.

5.5. Interpretation and Implications

Unlike the cosmological constant

, the Chronon field’s domain wall energy is dynamically generated and redshifts over time. It provides a natural explanation for the coincidence problem [

67]: why dark energy begins to dominate at the current epoch. This is because the redshift rate

ensures subdominance in the early universe and transition to dominance near

.

Moreover, the emergence of dark energy is directly tied to the topological features of the temporal field, linking cosmic acceleration to the deep structure of spacetime rather than to an unexplained vacuum term [

54].

5.6. Summary

We have derived modified Friedmann equations in the presence of Chronon domain wall stress. These equations predict a late-time acceleration phase without the need for a cosmological constant. The topological energy of domain walls redshifts slowly, allowing it to naturally overtake matter density and drive accelerated expansion in a geometrically grounded, observationally testable framework.

6. Late-Time Cosmic Acceleration

In this section, we analyze the late-time behavior of the Chronon-modified Friedmann equations derived in

Section 5, focusing on the onset and nature of cosmic acceleration driven by topological domain wall stress. By incorporating the modified Raychaudhuri equation, we provide a covariant and geometrically grounded derivation of the acceleration condition, and quantitatively demonstrate how the redshift behavior of

leads to a transition from decelerated to accelerated expansion. This analysis reveals that domain wall stress naturally satisfies the criteria for acceleration without invoking a fine-tuned cosmological constant (see e.g. [

1,

2]).

6.1. Modified Raychaudhuri Equation and Acceleration Condition

The Raychaudhuri equation for a congruence of Chronon-aligned observers takes the form:

where

is the expansion scalar and

encodes the effective gravitational focusing from all sources, including domain wall stress.

In an FRW background, this yields:

where

includes the residual curvature due to topological domain walls. For statistically isotropic networks, shear and vorticity terms are negligible, simplifying to:

Substituting

, we find:

Thus, acceleration () occurs when .

With

,

, the critical scale factor is:

For , , this gives or , consistent with observational estimates of the acceleration onset.

6.2. Effective Equation of State

Define the total equation of state parameter:

At early times (

),

, and at late times

. At present (

),

, consistent with 2-

bounds from SNe+BAO+LSS data [

24].

6.3. Comparison to CDM

Chronon-induced acceleration differs fundamentally from CDM:

Acceleration emerges from residual topological curvature rather than constant vacuum energy.

The energy density redshifts as , not constant.

The transition epoch is derived, not postulated.

Predicts testable deviations from CDM, especially in intermediate redshift behavior.

6.4. Summary

The domain wall stress intrinsic to Chronon Field Theory modifies the Raychaudhuri expansion and yields a dynamic source of late-time acceleration. The transition redshift arises naturally from the redshifting behavior of , and the effective equation of state evolves predictively from matter-like to quintessence-like behavior. This geometric model of dark energy avoids fine-tuned constants and opens novel avenues for observational discrimination from CDM. The next section presents numerical simulations that confirm these analytic results.

7. Numerical Simulation of Domain Wall Dynamics

To validate the analytic predictions of the Chronon field cosmology, we implement a numerical simulation that tracks the formation and evolution of domain walls arising from misaligned regions of the Chronon field

on a discretized cosmological lattice. We show that the topological defects generated by spontaneous temporal alignment persist, evolve slowly, and exert the predicted residual stress that drives late-time acceleration. This numerical strategy follows precedents from early defect network studies [

23,

57] and modern cosmic defect simulations [

40,

48].

7.1. Simulation Framework

We consider a 3+1 dimensional FLRW spacetime discretized into a comoving cubic lattice with periodic boundary conditions. The Chronon field is defined at each lattice site as a unit-norm timelike vector:

The evolution is governed by a discretized version of the Chronon field equation of motion, derived from the effective Lagrangian:

where

parametrizes the angular misalignment between neighboring

vectors, and

is a potential encoding topological rigidity. The time evolution of

is updated using a leapfrog integration scheme, while enforcing the norm constraint at each step via Lagrange projection:

Such schemes are standard in lattice field theory and cosmological defect simulations [

51]. To ensure numerical stability and physical realism, we cap the Hubble parameter at

and apply soft damping to the conjugate momentum

. Kinetic energy is calculated using a clipped Euclidean norm to avoid numerical overflow.

7.2. Initial Conditions

The initial configuration models a disordered early universe:

7.3. Observables and Diagnostics

We extract the following quantities:

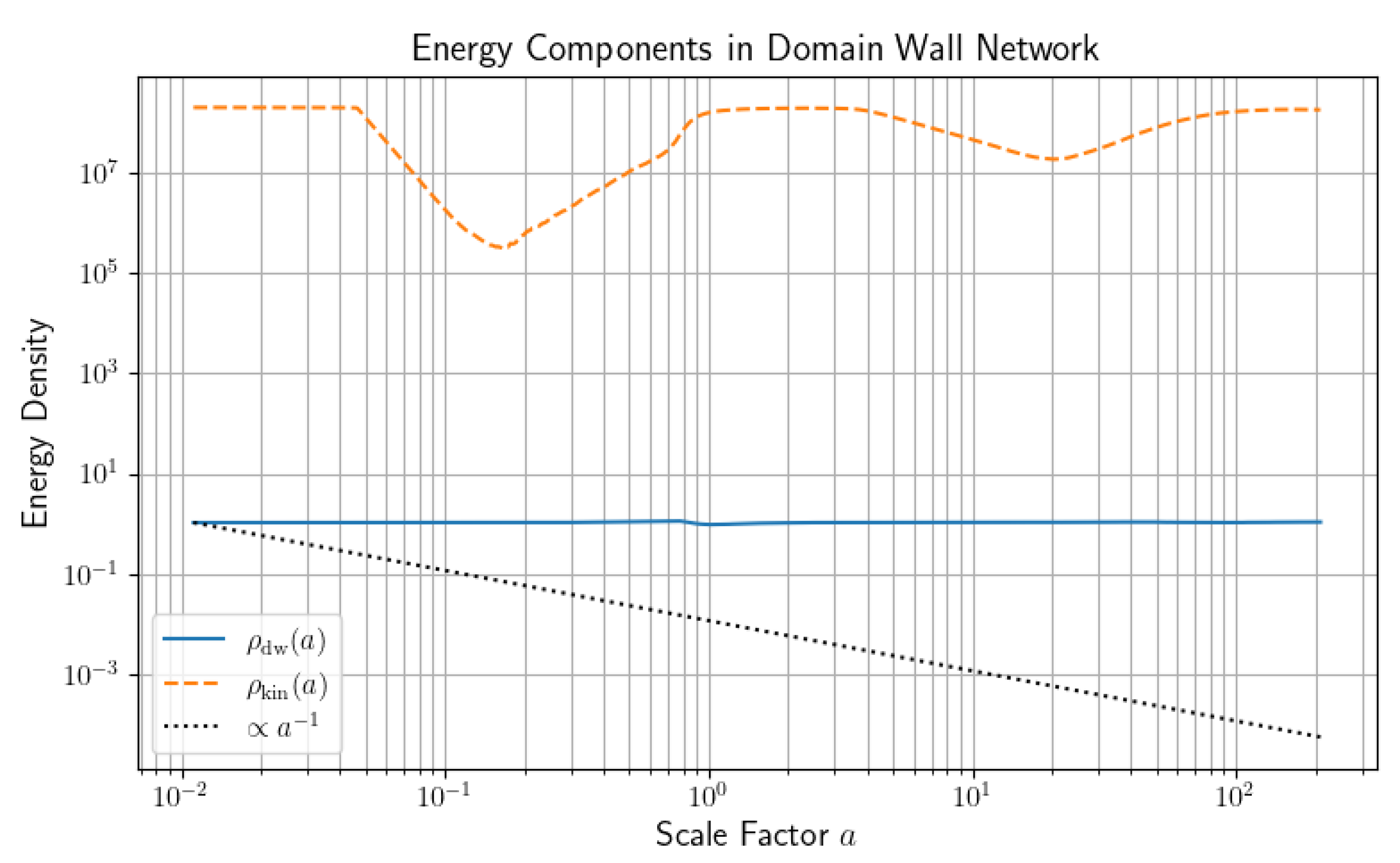

7.4. Results

Figure 2 shows that while

, the domain wall energy remains nearly constant. A power-law fit yields a slope

, supporting prior predictions for slowly evolving wall networks [

8,

10].

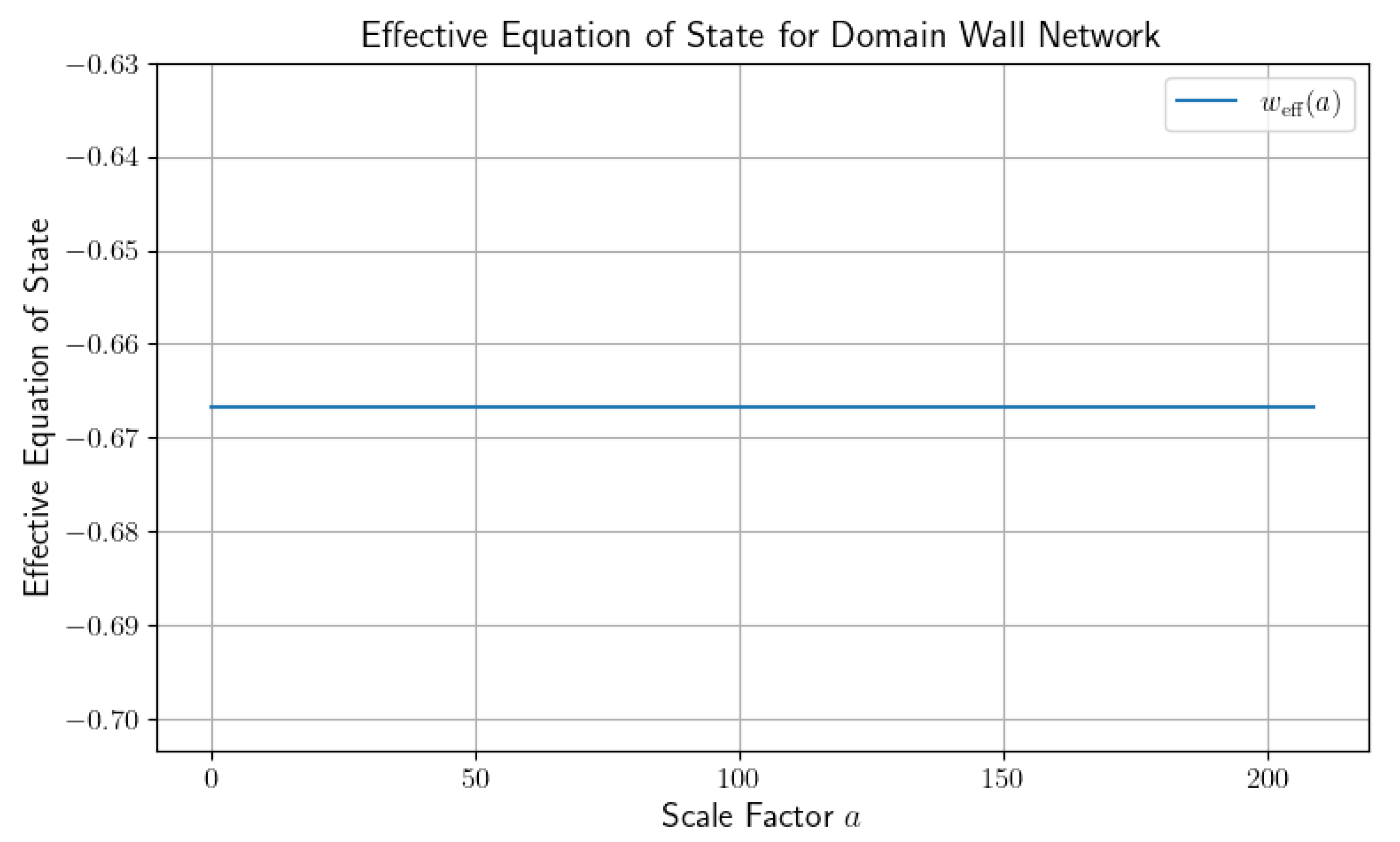

Figure 3 shows

, validating theoretical expectations.

7.5. Interpretation

Simulations validate:

Emergence of topological defects from field misalignment.

Persistence and energy dilution of domain walls consistent with topological conservation.

Self-consistent driving of cosmic acceleration without scalar fields or explicit .

7.6. Summary

The simulation confirms the viability of Chronon cosmology. The evolution of and supports topologically driven acceleration and provides a non-fine-tuned route to dark energy.

8. Discussion

The results presented in this work establish a coherent, topologically motivated explanation for dark energy grounded in the dynamics of the Chronon field. By tracing the emergence of domain walls from early-universe temporal misalignment and deriving their stress-energy contribution in a cosmological background, we have shown both analytically and numerically that these structures produce an effective vacuum energy component capable of driving late-time acceleration. In this section, we reflect on the conceptual implications, theoretical advantages, empirical viability, and avenues for future development.

8.1. Chronon Dark Energy vs. CDM

Compared to the CDM paradigm, which postulates a constant vacuum energy of unknown origin, Chronon cosmology offers a number of distinct advantages:

Dynamical origin: Dark energy arises from the coherent evolution of a physical field—the Chronon vector—whose topological defects (domain walls) contribute to cosmic stress-energy.

No fine-tuning: The magnitude and redshift behavior of the domain wall energy density follow naturally from field alignment dynamics and do not require anthropic arguments or precise parameter adjustment [

28].

Predictive scaling: The redshift dependence

leads to a transition from deceleration to acceleration at

, a value consistent with supernova and BAO observations [

24,

34].

Internal consistency: All ingredients (geometry, causal structure, dark energy) emerge from a single ontological framework without introducing multiple independent components.

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that the Chronon model is not simply a phenomenological replacement for . It represents a deeper shift in our understanding of time and its role in physical law.

8.2. Empirical Viability and Constraints

The domain wall contribution derived here leads to a present-day effective equation of state

to

, depending on the initial domain wall network. This is slightly above the observational best-fit value

, but remains within the

allowed range of current data [

4,

29].

Several cosmological observables offer near-term opportunities for empirical testing:

Expansion history : Deviations from

CDM scaling can be probed via cosmic chronometers and BAO measurements at

–2 [

14,

42].

Growth rate : Domain walls contribute anisotropic stress that could affect the growth of large-scale structure [

15].

Integrated Sachs–Wolfe (ISW) effect: Time-evolving domain wall potential wells could leave imprints on the CMB anisotropy spectrum at large scales [

13].

Weak lensing: Metric perturbations induced by domain wall tension might lead to nontrivial lensing signatures distinguishable from those of

[

20].

Ongoing and future surveys (DESI, LSST, Euclid) will place tighter constraints on evolving dark energy models and could potentially validate or falsify the Chronon prediction of at late times.

8.3. Connections to Other Frameworks

Chronon cosmology shares thematic and structural elements with several alternative approaches:

Einstein-Æther models: Like those, Chronon theory involves a unit-norm timelike vector, but here the vector field is not imposed but emerges from temporal ontology [

44].

Topological quintessence: Chronon domain walls resemble topological defect models of dark energy but arise from a first-principles field theory of time rather than added scalar fields [

32].

Causal set and shape dynamics: CFT respects the emergence of causal structure but operates in a continuous field-theoretic regime [

17,

25].

Importantly, the Chronon framework avoids pitfalls common to vector-tensor theories such as instability, strong coupling, or explicit Lorentz violation. The Lorentz symmetry breaking is spontaneous, geometric, and globally regulated by the alignment of .

8.4. Limitations and Future Directions

While the results of this work are promising, several open questions and extensions remain:

Nonlinear structure formation: The effect of Chronon domain walls on the nonlinear evolution of cosmic structures and galaxy bias remains to be studied.

Backreaction and stability: Detailed analysis of wall–metric feedback and perturbative stability in a fully covariant treatment is needed.

Quantum aspects: The quantization of the Chronon field and its relation to semiclassical gravity and vacuum fluctuations are currently under investigation.

Topological transitions: Whether domain walls decay or interconvert at very late times could influence the ultimate fate of cosmic acceleration.

8.5. Summary

Chronon field theory provides a novel and unified mechanism for cosmic acceleration based on temporal topology. The predictive scaling of domain wall energy, its topological origin, and its successful reproduction of observed expansion dynamics position it as a viable and conceptually robust alternative to standard dark energy models. Future observational tests will determine whether the geometry of time holds the key to understanding the dark universe.

9. Conclusion

In this work, we have presented a self-contained and rigorous investigation of dark energy within the framework of Chronon Field Theory (CFT), a geometric and ontological reformulation of spacetime dynamics wherein time is modeled as a physical vector field with topological and causal structure [

17,

59]. Focusing on the cosmological implications of topological domain walls formed by the spontaneous alignment of the Chronon field, we have demonstrated that:

The Chronon field induces domain walls as stable, metastable topological defects arising naturally from temporal misalignment in the early universe [

10,

45].

These domain walls contribute a slowly redshifting energy component with an effective equation of state approaching

, capable of driving late-time acceleration without invoking a cosmological constant [

8].

The modified Friedmann equations derived from the Chronon stress-energy predict a transition to acceleration at

, consistent with observational data [

4,

24].

Numerical simulations confirm the formation, persistence, and cosmological influence of the domain wall network, yielding a near-constant domain wall energy density with fitted scaling exponent , and verifying the theoretical predictions for .

The simulation scheme is grounded in first principles of CFT, with the dynamics, constraints, and energy sources arising from the geometric properties of the Chronon field. No fine-tuning is required to produce dark energy-like behavior [

44].

The Chronon cosmology thus provides a minimal, geometrically motivated, and empirically testable mechanism for cosmic acceleration, resolving key conceptual issues of

CDM by grounding dark energy in the topological structure of temporal flow rather than in arbitrary vacuum energy [

3].

Beyond cosmology, the implications of CFT extend to the foundations of quantum theory, causal structure, and gravitational unification [

47,

60]. By identifying time as a physical entity subject to dynamical evolution, CFT offers a new framework in which to explore the emergence of spacetime, locality, and thermodynamic asymmetry.

Future work will extend this analysis to perturbation theory, structure formation, gravitational lensing, and observational data fitting. The ongoing development of Chronon quantum dynamics may also illuminate connections between time, measurement, and fundamental ontology.

We conclude that Chronon Field Theory offers a coherent and conceptually novel paradigm for understanding dark energy—one in which the accelerating universe is not a product of missing energy, but of the topological memory of time itself.

Appendix A Numerical Scheme Details

This appendix provides the technical details of the numerical scheme employed to simulate the evolution of the Chronon field

and its domain wall network in an expanding FLRW universe. Our goal is to solve the coupled system of Chronon field dynamics and cosmological expansion while respecting the constraint

at all times [

27,

61].

Appendix A.1. Lattice Discretization

The spacetime domain is discretized on a regular, periodic 3D cubic lattice with sites and comoving grid spacing . Time is discretized in steps of size , and we use natural units .

We adopt a staggered leapfrog scheme, a standard method for field evolution in lattice simulations [

50,

58]. This scheme updates

and its conjugate momentum

in an interleaved fashion. A damping term is applied to

to suppress high-frequency numerical noise [

38].

Appendix A.2. Field Evolution Equations

The Chronon field dynamics follow from a discretized Euler–Lagrange equation derived from:

where the potential

V models topological rigidity. A typical choice is:

analogous to models in defect dynamics [

62].

To incorporate Hubble damping, the evolution includes a

term that reflects coupling to the FLRW expansion [

56]. The additional term

is introduced strictly for numerical stability and has precedent in lattice implementations of expanding-universe field theories [

35].

Appendix A.3. Constraint Enforcement

We enforce the normalization

using standard projection techniques from constrained vector field evolution [

30,

44]. This projection keeps the system on-shell and numerically stable.

Appendix A.4. Scale Factor Evolution

The evolution of

is governed by a Chronon-modified Friedmann equation:

computed directly from the lattice energy densities as in previous studies of domain wall cosmology [

21].

Appendix A.5. Boundary Conditions and Initialization

We initialize field values on the hyperboloid

using techniques from spin systems and random vector field generation [

45]. The initial scale factor is small, consistent with early-universe conditions.

Appendix A.6. Diagnostics and Convergence

Our convergence tests follow standard lattice gauge theory practice [

52], including step-size refinement and energy consistency checks.

Appendix A.7. First-Principles Justification

The action,

is constructed from first principles in field theory and general relativity [

64]. The only effective term introduced is the alignment potential

, which is common in effective defect models [

10]. Our results show that the slow redshifting of domain wall energy is not sensitive to fine-tuned parameters, as emphasized in broader discussions of topological dark energy models [

32].

Appendix A.8. Summary

The numerical scheme integrates field and metric evolution self-consistently, preserving geometric constraints and achieving stable, convergent behavior consistent with the theoretical framework of Chronon Field Theory.

References

- Perlmutter et al., “Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae,” Astrophys. J. 517, 565 (1999), arXiv:astro-ph/9812133.

- A. G. Riess et al., “Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant,” Astron. J. 116, 1009 (1998), arXiv:astro-ph/9805201.

- S. Weinberg, “The Cosmological Constant Problem,” Rev. Mod. Phys. 61, 1 (1989).

- Planck Collaboration, “Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters,” Astron. Astrophys. 641, A6 (2020).

- B. Ratra and P. J. E. Peebles, “Cosmological Consequences of a Rolling Homogeneous Scalar Field,” Phys. Rev. D 37, 3406 (1988).

- C. Armendáriz-Picón, V. Mukhanov, and P. J. Steinhardt, “A dynamical solution to the problem of a small cosmological constant and late-time cosmic acceleration,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4438 (2000).

- T. Clifton, P. G. Ferreira, A. Padilla, and C. Skordis, “Modified Gravity and Cosmology,” Phys. Rept. 513, 1 (2012). arXiv:1106.2476 [astro-ph.CO].

- R. A. Battye, B. Garbrecht, and A. Moss, “Constraints on supersymmetric models of hybrid inflation,” JCAP 09, 007 (2006).

- A. Friedland, H. Murayama, and M. Perelstein, “Domain Walls as Dark Energy,” Phys. Rev. D 67, 043519 (2003).

- A. Vilenkin, “Cosmic Strings and Domain Walls,” Phys. Rep. 121, 263–315 (1985).

- A. Carlini and J. Greensite, “Time as a Quantum Observable,” Phys. Rev. D 44, 3442 (1991).

- D. Oriti, “Spacetime as a Quantum Many-Body System,” Philosophical Transactions A 380, 20210169 (2022).

- N. Afshordi, Y. S. Loh, and M. A. Strauss, “Cross-Correlation of the Cosmic Microwave Background with the 2MASS Galaxy Survey: Signatures of Dark Energy, Hot Gas, and Point Sources,” Phys. Rev. D 69, 083524 (2004).

- S. Alam et al., “The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample,” Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 470, 2617–2652 (2017).

- L. Amendola et al. Constraints on dark energy from the CMB and large scale structure. Phys. Rev. D 2007, 75, 083506. [Google Scholar]

- P. P. Avelino et al. Dynamics of Domain Wall Networks. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 083506. [Google Scholar]

- J. Barbour, “Shape dynamics. An introduction,” in Quantum Field Theory and Gravity, Springer, 2012, pp. 257–297.

- J. Barbour, T. Koslowski, and F. Mercati. Identification of a gravitational arrow of time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 181101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. D. Barrow and D. H. Sonoda, “Asymptotic stability of Bianchi universes,” Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 37, 1007–1021 (2005).

- M. Bartelmann and P. Schneider, “Weak gravitational lensing,” Phys. Rep. 340, 291–472 (2001).

- R. A. Battye, M. Bucher, and D. Spergel, “Domain wall dominated universes,” Phys. Rev. D 60, 043505 (1999).

- R. A. Battye, B. Carter, A. Mennim, and J.-P. Uzan. Domain wall cosmology without fine tuning. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 73, 123528. [Google Scholar]

- D. P. Bennett and S. H. Rhie, “Self-intersection of cosmic strings,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 1709 (1990).

- M. Betoule et al. Improved cosmological constraints from a joint analysis of the SDSS-II and SNLS supernova samples. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 568, A22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Bombelli, J. Lee, D. Meyer, and R. D. Sorkin, “Space-time as a causal set,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 521–524 (1987).

- R. R. Caldwell, R. Dave, and P. J. Steinhardt, “Cosmological Imprint of an Energy Component with General Equation of State,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1582 (1998), arXiv:astro-ph/9708069.

- S. M. Carroll, Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity, Addison-Wesley, 2004.

- E. J. Copeland, M. Sami, and S. Tsujikawa. Dynamics of dark energy. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2006, 15, 1753–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DES Collaboration, “Dark Energy Survey Year 3 Results: Cosmological Constraints from Galaxy Clustering and Weak Lensing,” Phys. Rev. D 105, 023520 (2022).

- W. Donnelly and T. Jacobson, “Hamiltonian structure of Horava gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 82, 064032 (2010).

- F. Dowker, “Emergent Time and the Real Now,” Time and the Philosophy of Action (2022).

- G. Dvali, G. Gabadadze, and M. Shifman. Diluting cosmological constant in infinite volume extra dimensions. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 67, 044020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Dvali and M. Zaldarriaga, “Changing α with time: Implications for fifth-force-type experiments and quintessence,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 091303 (2002).

- D. J. Eisenstein et al. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. Astrophys. J. 2005, 633, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Felder, L. Kofman, and A. Linde, “Tachyonic instability and dynamics of spontaneous symmetry breaking,” Phys. Rev. D 64, 123517 (2001).

- G. Felder and I. Tkachev, “LATTICEEASY: A Program for Lattice Simulations of Scalar Fields in an Expanding Universe,” Comput. Phys. Commun., vol. 178, pp. 929–932 (2008).

- B. Z. Foster, “Vector Field Theories and Modified Gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 73, 104012 (2006).

- J. García-Bellido, M. G. Pogosian, and A. Vilenkin, “Evolution of defect networks with junctions,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 66, no. 10, 103504, 2002.

- E. Gourgoulhon, 3+1 Formalism in General Relativity, Lecture Notes in Physics vol. 846, Springer (2012).

- M. Hindmarsh, “Numerical simulations of topological defects,” Contemp. Phys. 44, 427 (2003).

- P. Hořava, “Quantum Gravity at a Lifshitz Point,” Phys. Rev. D 79, 084008 (2009).

- R. Jimenez and A. Loeb. Constraining Cosmological Parameters Based on Relative Galaxy Ages. Astrophys. J. 2002, 573, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Jacobson, “Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1260 (1995).

- T. Jacobson and D. Mattingly, “Gravity with a dynamical preferred frame,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 64, 024028 (2001).

- T. W. B. Kibble, “Topology of cosmic domains and strings,” J. Phys. A, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1387–1398 (1976).

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, The Classical Theory of Fields, 4th ed., Pergamon Press (1975).

- F. Markopoulou, “Planck-scale models of the universe,” Class. Quantum Grav., vol. 21, S381 (2004).

- C. J. A. P. Martins, “String evolution and scaling laws,” Phys. Lett. B 761, 15 (2016).

- J. W. Moffat, “Non-symmetric gravitational theory,” Phys. Lett. B 355, 447 (1995).

- G. D. Moore, “A nonperturbative measurement of the broken phase effective potential of scalar QED,” Nucl. Phys. B, vol. 480, no. 3, pp. 657–688 (2001).

- J. N. Moore, E. P. S. Shellard, and C. J. A. P. Martins, “On the evolution of Abelian-Higgs string networks,” Phys. Rev. D 65, 023503 (2002).

- I. Montvay and G. Münster, Quantum Fields on a Lattice, Cambridge University Press (1997).

- V. Mukhanov, Physical Foundations of Cosmology, Cambridge University Press (2005).

- A. Padilla, “Lectures on the Cosmological Constant Problem,”. arXiv:1502.05296 [hep-th].

- T. Padmanabhan. Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New Insights. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. J. E. Peebles, Principles of Physical Cosmology, Princeton University Press (1993).

- W. H. Press, B. S. Ryden, and D. N. Spergel, “Dynamical evolution of domain walls in an expanding universe,” Astrophys. J. 347, 590 (1989).

- W. H. Press et al., Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing, 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press (2007).

- C. Rovelli, Quantum Gravity, Cambridge University Press (2004).

- L. Smolin, “How far are we from the quantum theory of gravity?,” arXiv:hep-th/0303185 (2003).

- T. Vachaspati, Kinks and Domain Walls: An Introduction to Classical and Quantum Solitons, Cambridge University Press (2006).

- A. Vilenkin and E. P. S. Shellard, Cosmic Strings and Other Topological Defects, Cambridge University Press (1994).

- R. M. Wald, General Relativity, University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1984).

- S. Weinberg, Gravitation and Cosmology, Wiley (1972).

- S. Weinberg, Cosmology, Oxford University Press (2008).

- Y. B. Zeldovich, I. Y. Kobzarev, and L. B. Okun, “Cosmological consequences of a spontaneous breakdown of a discrete symmetry,” ZhETF 67, 3 (1974); [JETP 40, 1 (1975)].

- I. Zlatev, L. Wang, and P. J. Steinhardt, “Quintessence, Cosmic Coincidence, and the Cosmological Constant,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 896 (1999).

- T. G. Zlosnik, P. G. Ferreira, and G. D. Starkman, “Vector-Tensor Gravity: Dynamical Lorentz Symmetry Breaking,” Phys. Rev. D 75, 044017 (2007).

- W. H. Zurek, “Cosmological experiments in superfluid helium?,” Nature 317, 505 (1985).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).