1. Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a severe pulmonary complication of connective tissue disease that can lead to significant morbidity and mortality [

1]. ILD has a significant impact on health and mortality. According to the Global Burden of Disease data, approximately 4.7 million people worldwide were living with ILD in 2019 [

2]. The prevalence of ILD has been on the rise over the past decades, with global estimates varying from 6 to 71 cases per 100,000 people. The impact of ILD extends beyond the disease itself, as patients often require ongoing treatments such as medications, oxygen supplementation, and frequent clinical follow-ups, which can place a burden on healthcare systems through increased resource consumption [

2].

Sonographic Interstitial Syndrome (SIS) is a term used to describe the main manifestation of ILD, characterised by vertical lines extending from the lung interface. SIS is a major diagnostic sign of ILD and represents one of the most significant visual artefacts seen on lung ultrasound (LUS) images (3–5). SIS, also known as B-lines [

5], comet tails [

6], lung rockets [

7], or light beams [

8], is, in essence, a set of hyperechoic vertical lines that arise from the pleural line and extend to the bottom of the LUS image [

9,

10]. However, B-Lines are not exclusively a pathological finding because they can sometimes be observed in healthy individuals under certain conditions, particularly in elderly patients [

11]. In such cases, isolated B-lines may appear in small numbers, symmetrically distributed, and confined to specific lung zones. This pattern contrasts with pathological B-lines, which are typically numerous, asymmetrical, and diffusely spread across multiple lung regions. Recognising these qualitative distinctions is essential for avoiding misdiagnosis when interpreting lung ultrasound scans. One of the biggest challenges in expanding the use of LUS is the steep learning curve; it takes considerable training and experience to accurately perform and interpret LUS videos [

12]. This presents a major barrier to access, particularly in healthcare settings where trained professionals are scarce.

Several studies have utilised AI to enhance the robustness of the classifications and to learn more distinctive features from input LUS frames [

13,

14]. Some have shown the potential to classify COVID-19 patients from healthy patients, while others have explored AI tools’ capabilities in the automated detection of B-lines associated with conditions like pulmonary oedema and pneumonia (15–24). All these studies focused on frame-level analysis. Using frame-based data to train AI algorithms requires extensive clinician annotation efforts. Indeed, manual annotation of the data, particularly frame-by-frame labelling, is laborious and time-consuming, particularly due to the extensive number of frames that require labelling by clinicians. Beyond the logistical burden, relying solely on individual frames also poses a conceptual limitation: it may fail to capture temporal dynamics critical for accurate diagnosis. Unlike frame-based Deep Learning (DL) models that only examine static images, clinicians typically rely on the entire LUS video to examine lung conditions. They consider the dynamic changes, such as the movement and appearance of B-lines, and temporal changes, such as the texture, intensity, or spread of B-lines over the videos. These aspects provide contextual information for an accurate diagnosis.

Recent advances in AI have enabled real-time interpretation in ultrasound imaging, particularly where lightweight models are essential for deployment in remote or point-of-care (POC) settings. This advancement in AI models enables ultrasound video interpretation within noticeably short timeframes. Several studies reported high inference speeds for video interpretation—typically reported between 16 and 90 frames per second (FPS), depending on the chosen architecture and available computational resources (25–30). These studies have successfully demonstrated the feasibility of real-time AI implementation in multiple US applications, such as tumour segmentation, plaque detection, and cardiac assessments, where timely and accurate interpretation is critical for clinical decision-making. Therefore, exploring similar real-time AI tools for LUS is a promising yet insufficiently explored area of research, considering that clinical diagnostic decisions in LUS are based not on static frames like chest x-rays but on the temporal relationships between consecutive frames, such as the presence or absence of B-lines and evolving artefact patterns within LUS frames. These dynamic features require an AI tool that can process real-time videos holistically rather than relying solely on frame-by-frame analysis.

To date, only a single study has focused on using AI to classify entire LUS videos: Khan et al. [

31] introduced an efficient method for LUS video scoring, focused in particular on COVID-19 patients. Using intensity projection techniques, their approach compresses entire LUS videos into a single image. The compressed images enable automatic classification to assess the patient’s condition, eliminating the need for frame-by-frame analysis and allowing for effective scoring without the need for frame-by-frame analysis. A convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the ResNet-18 architecture, the ImageNet-pretrained model, is then used to classify this compressed image, with the predicted score assigned to the entire video. This method reduces computational overhead and minimises error propagation from individual frame analysis while maintaining a high classification accuracy.

In contrast, our study employs a video-based training method, where a CSwin transformer is trained on a dataset of LUS videos [

32]. This method involves utilising a transformer model to capture dynamic changes and feature progression across LUS frames, enabling it to learn how patterns, such as the movement or spread of B-lines, evolve throughout an LUS video rather than examining individual frames in isolation. Initially developed for natural language processing, CSwin transformer algorithms are DL neural networks that can also analyse temporal connections among images, such as in video classifications (33–36). Video-based training, instead, involves assigning a label to an entire video based on its content, allowing the model to classify whether a given video represents a healthy or unhealthy score. This work’s novelty lies in using the CSwin Transformer, for the first time in the context of LUS with advanced data filtering techniques before training. By carefully selecting the most relevant frames in an LUS video dataset, the model can better focus on distinguishing features between classes, healthy and non-healthy videos, and avoid being influenced by irrelevant frames containing features unrelated to the target classifications. This approach improves the model’s performance by focusing on the most relevant frames and lowers computational demands.

4. Discussion

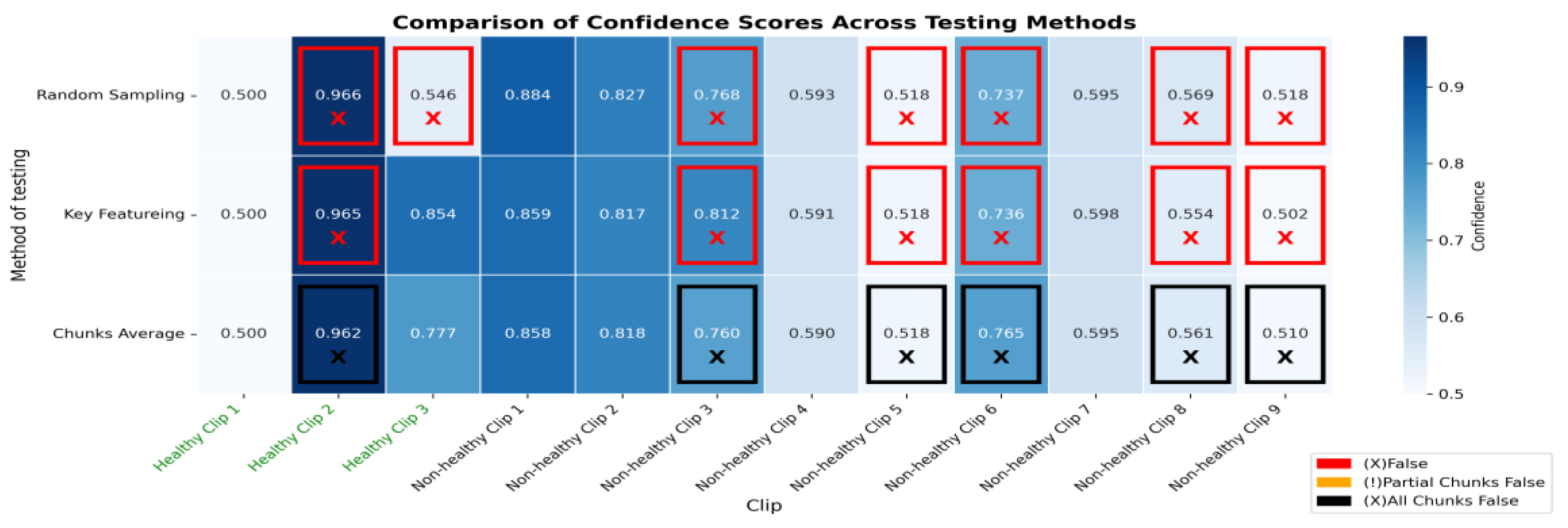

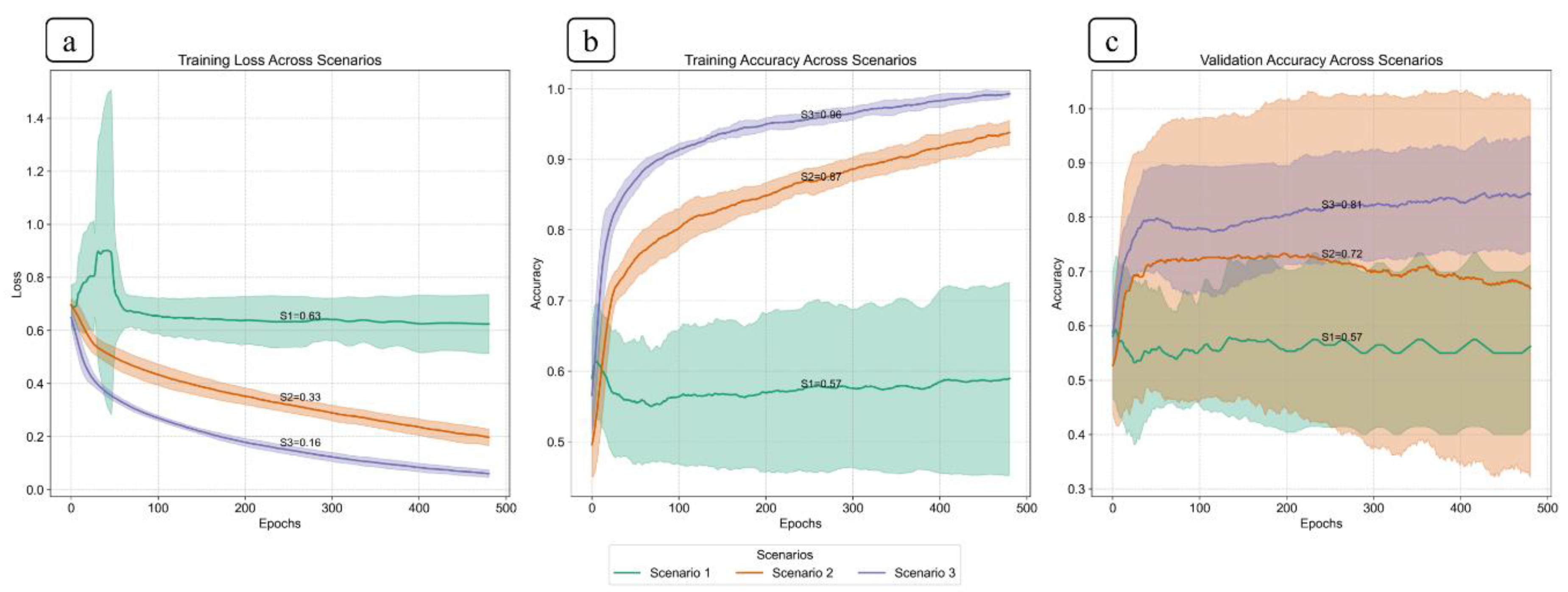

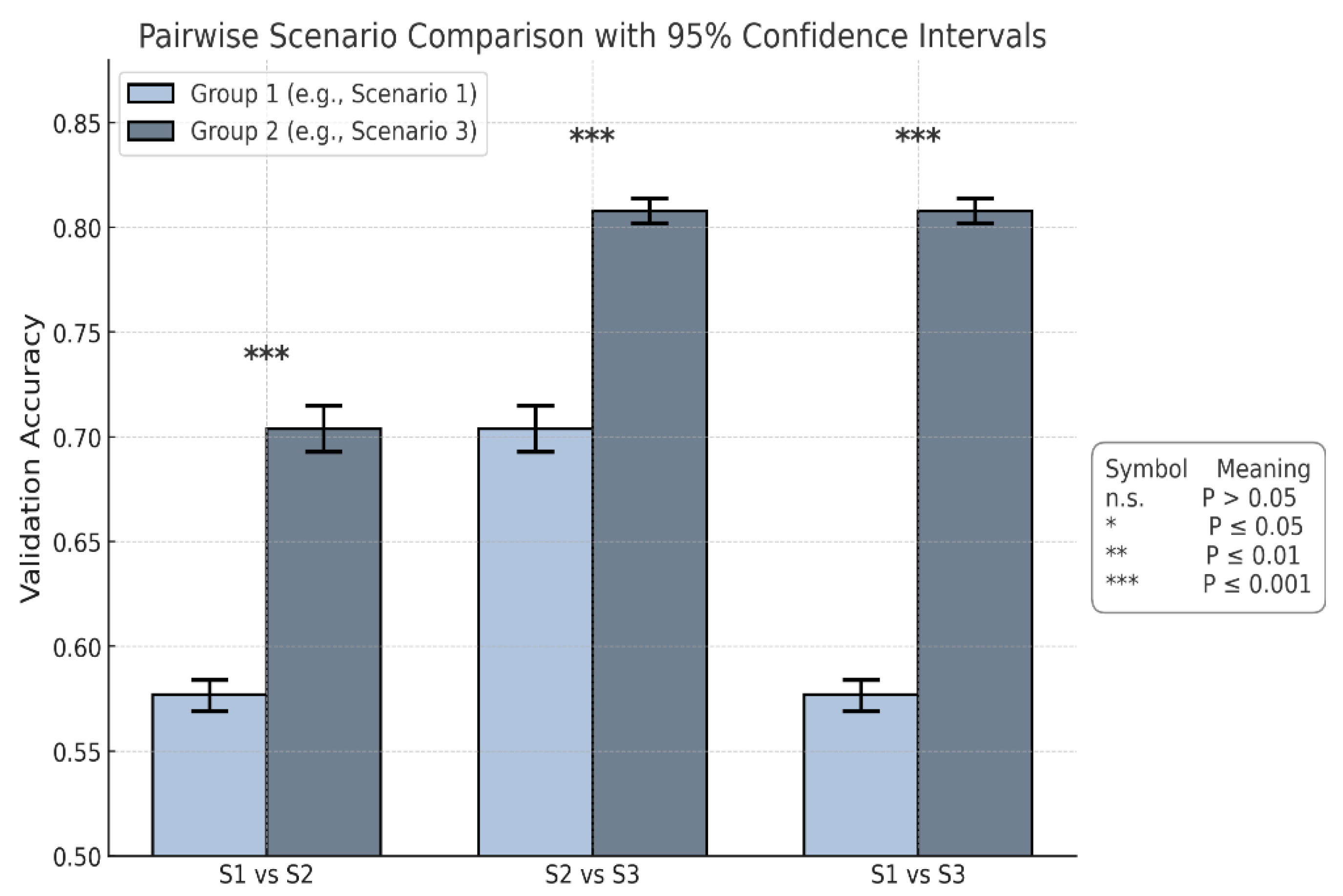

The findings in this study highlight the effectiveness of selective frame filtering in improving model performance via video-based training with the CSwin Transformer, as demonstrated in Scenario 3 (S3). The experimental training performed in S3 features the significance of our approach in selecting frames within videos prior to the training process, as it can significantly influence the model’s performance and result in apparent differences across all performance metrics when compared to Scenario 1 (S1) and Scenario 2 (S2). The statistical result verifies that the frame filtering implemented in S3 drastically improves the model’s ILD classification accuracy. The ANOVA analysis (p < 0.001) proves the presence of differences, and Tukey’s HSD shows that all pairwise comparisons between the three scenarios are statistically significant. Furthermore, Cohen’s d values exceeding 8 highlight substantial effect sizes. When considering the confidence intervals, Scenario 3 had the highest mean accuracy (0.808), suggesting it delivered the strongest performance overall.

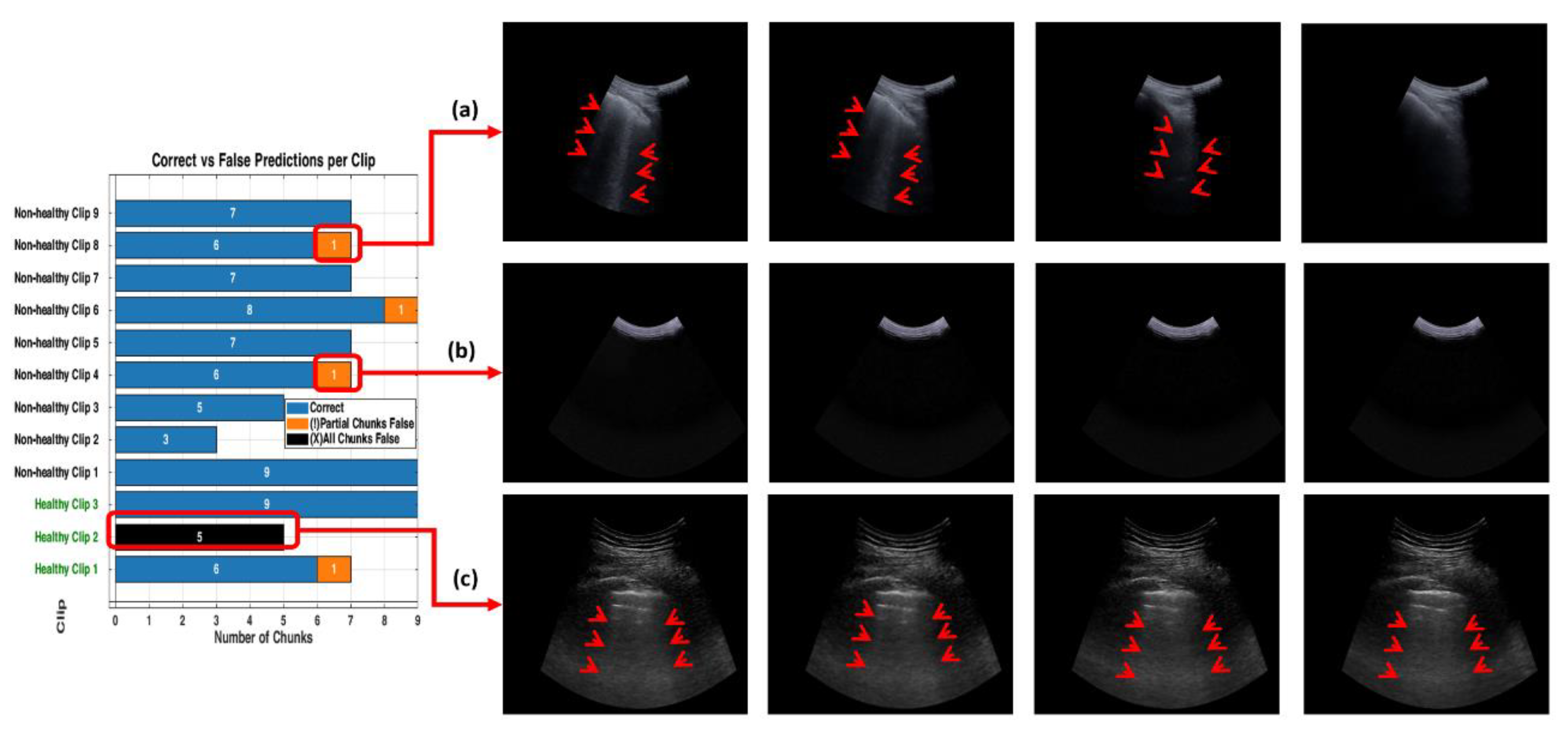

Overall, this work highlights the effectiveness of filtering frames from each LUS video applied prior to training, leading to high classification performance in Scenario 3. The improved performance of the model in this scenario can be attributed to the removal of misleading frames, driving the model to focus on those that prominently feature key diagnostic frames, such as B-lines. This technique allowed the model to distinguish between healthy and non-healthy videos accurately. The misclassifications observed within all testing methods show the model’s nuanced performance. Within non-healthy videos, for instance, video 8 (

Figure 14a) shows key diagnostic features—specifically B-lines—where the model correctly classified most of the chunks, although some errors still occurred. This implies that while the model can identify important markers of IS, it could encounter challenges when processing chunks containing only a few frames with diagnostic features visible (B-lines). The misclassification in video 3 (

Figure 14b) presents an interesting case. Although the chunk was classified as healthy, the frames were empty or contained non-diagnostic content. This outcome can be interpreted positively, demonstrating the model’s sensitivity to non-diagnostic content within the LUS video. Though the model erroneously flagged this case as a negative, its ability to correctly classify non-diagnostic chunks shows its strong spatial reasoning in each small chunk. This indicates that the model does not overlook any LUS video segments but instead scans each segment in a small portion of frames to make context-aware classification. The model’s ability to correctly label empty or featureless frames as healthy demonstrates that the model has learned to associate the absence of diagnostic features with a healthy class label. This highlights the model’s capability to rely on the presence of diagnostic markers for accurate decision-making.

For the healthy videos, classification accuracy demonstrated inconsistent performance, as detailed in

Section 3.3. Although videos 1 and 3 were mostly classified correctly across all three testing methods (RS, KF, and CA), video 2 was completely misclassified. This may be attributed to the short lines resembling B-lines, as illustrated in

Figure 14c. In the normal lung, horizontal reverberation artefacts are called A-lines. However, under suboptimal conditions—such as poor probe angling or inadequate proper skin contact—A-lines can interact with the pleural interface, producing vertical lines known as Z-lines. These vertical lines, presenting as low-intensity and poorly defined, originate from the pleural line and may resemble B-lines [

41,

42]. This misclassification shows the model’s susceptibility to vertical artefacts that mimic true B-lines and reveals a diagnostic limitation in distinguishing pathological features from normal ones. One plausible reason for this limitation could be that the training dataset does not include enough examples of healthy example frames, especially those with normal features like Z-lines.

Compared to existing literature, which primarily used a frame-based DL model [

13,

14], this research emphasises the advantages of a video-based approach that accounts for the temporal relationships between LUS frames. As frame-based models often lose critical dynamic information across an entire LUS video, the video-based model in this study captures temporal variations from LUS frames for accurate diagnosis. Although prior research has applied AI to classify individual LUS frames, the classification of entire LUS videos has not been widely explored. In only a single study, the use of a method to compress a video into a single-image representation sacrifices the temporal depth that may be necessary for thorough diagnostic analysis [

31]. In contrast, our AI model captures these temporal variations to improve accuracy and address a gap in video-based LUS classification, demonstrating how selective filtering techniques enhance model performance. This work addresses this gap and demonstrates how selective filtering of LUS frames improves the performance of the video-based model.

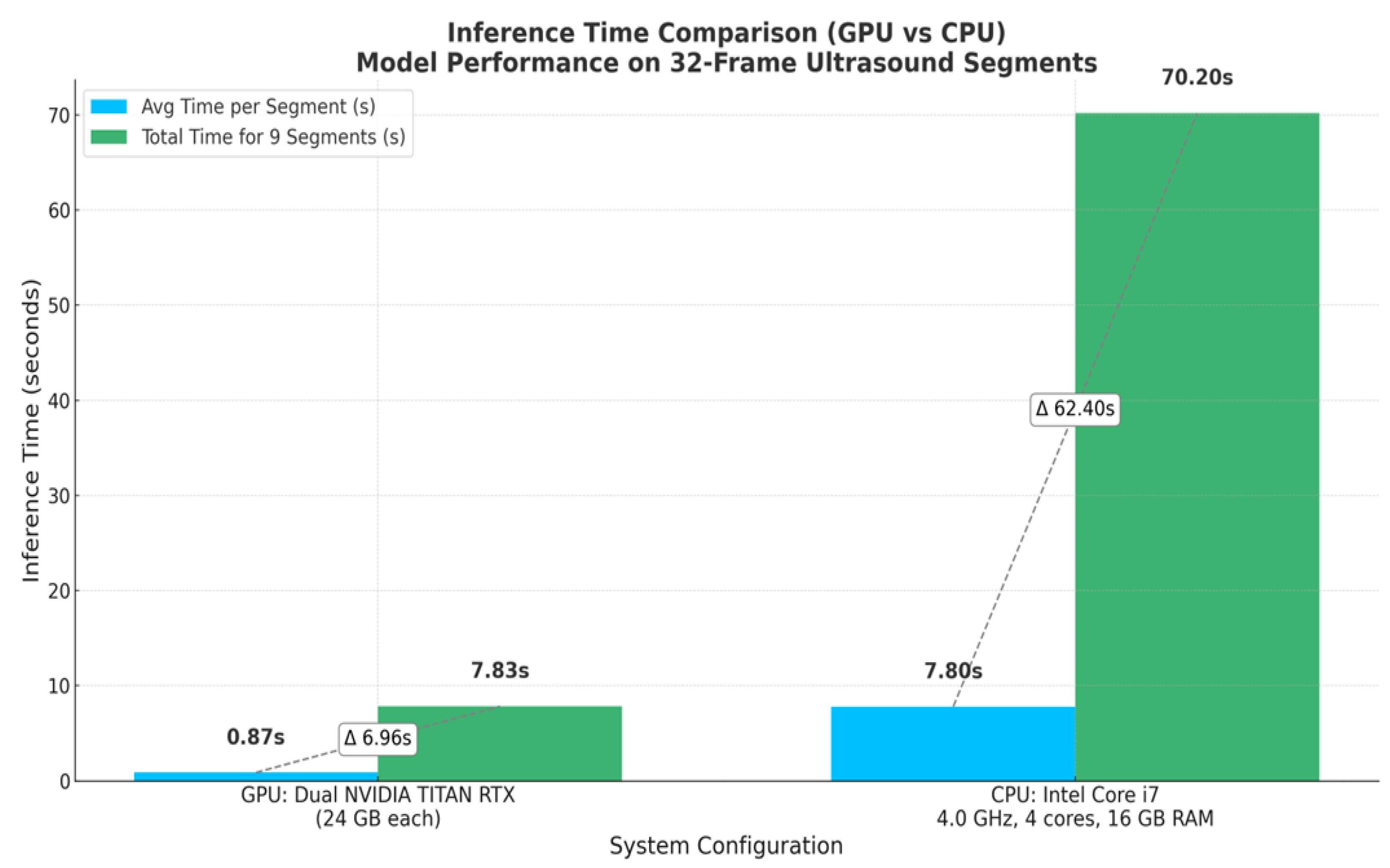

Additionally, the developed model shows practical viability for real-time inferencing, achieving an average latency time of 0.87 seconds per segment, 32 frames each (approximately 37 FPS), which exceeds the threshold for real-time clinical deployment (25–30). In this context, real-time inferencing means that the model can process video at a rate equal to or faster than the ultrasound machine’s frame acquisition (30 FPS ), thereby enabling medical experts to receive immediate diagnostic feedback during scanning. This level of performance not only validates the model’s suitability for point-of-care (POC) use but also highlights its potential for integration into mobile computing platforms. It can be valuable in remote and emergency settings with limited computational resources and time.

Despite the promising results noted in this study, the dataset used was relatively small, particularly for healthy videos in the testing phase. This reflects the nature of data collection in clinical settings where non-healthy cases are more commonly recorded. In addition to the challenges of dataset size, an important consideration is the inherent complexity of LUS acquisition. The captured LUS videos may contain portions representing healthy and non-healthy regions, as seen in the testing videos in

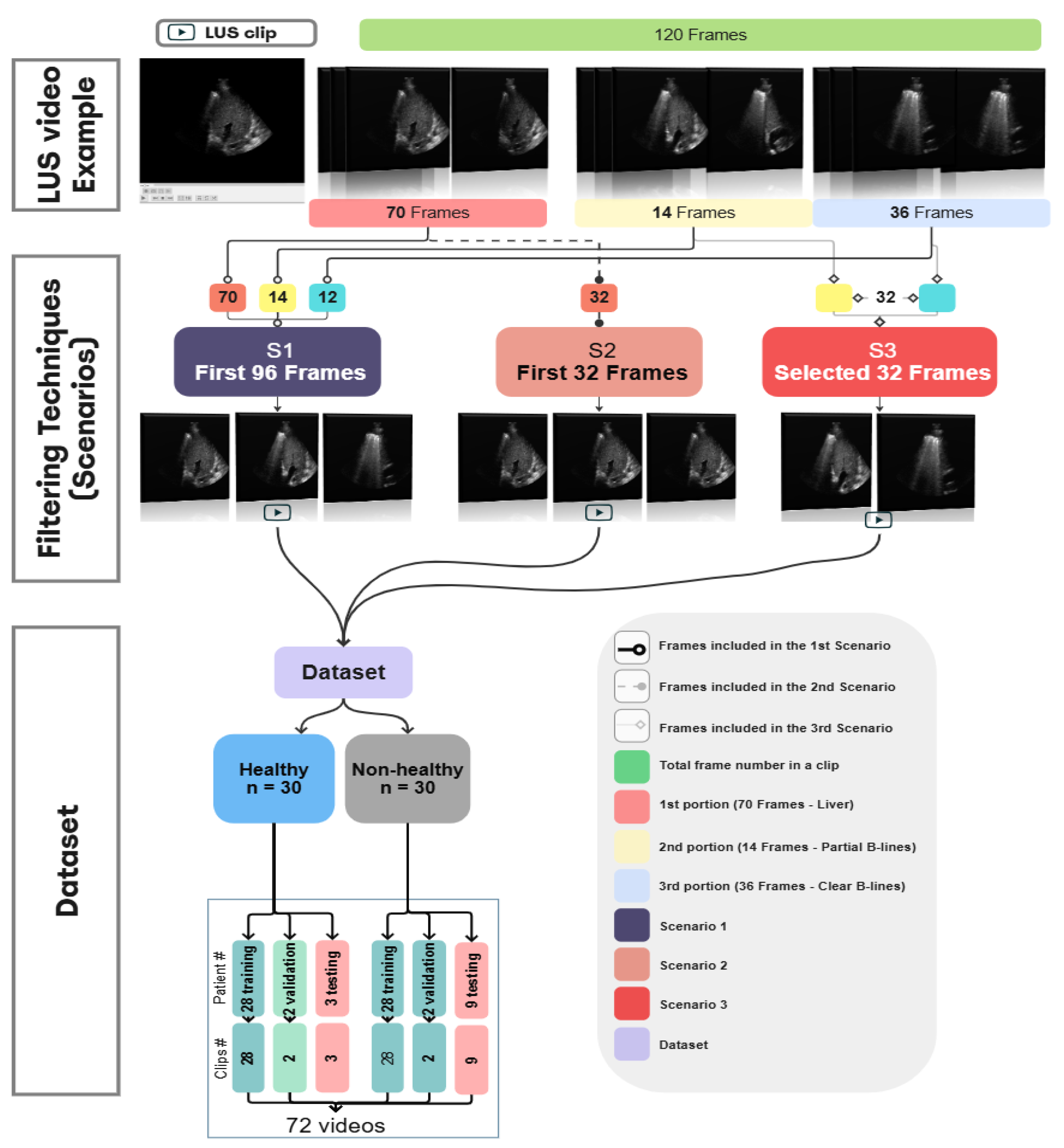

Figure 14b. As the sonographer performs the acquisition, based on their hands-on experience and the patient’s status, they may be able to capture key diagnostic features within the LUS video. They may include a mix of diagnostic and non-diagnostic frames. Therefore, LUS acquisition, while convenient and portable, can introduce variability in the quality and consistency of the captured frames within LUS videos. The quality of the captured LUS videos can be influenced by both the patient’s status and the sonographer’s expertise. Depending on these factors, the captured video might include a mix of representative diagnostic and non-diagnostic or non-representative frames within the LUS video. Including all the captured videos can impact the model’s performance and cause ambiguity during training, as evident in Scenario 1 (S1), where raw LUS videos contain a mix of representative and non-representative frames (96 frames). In Scenario 2 (S2), a small number of frames from 32 without applying any filtering were used. However, this approach did not address the presence of non-informative or irrelevant content, as within the 32 frames, a mix of representative diagnostic and non-diagnostic or non-representative frames may be present. Therefore, the filtering technique was implemented during training to address the variability in LUS videos in S3, where it minimised the number of frames from 96 to 32. Applying the filtering technique in S3, where the representative portions of the ultrasound videos are only included, allows the model to focus on relevant features, such as B-lines in pathological cases, contributing to improved performance during evaluation.

Another limitation of this work is that the model developed in Scenario 3 (S3) was trained using a fixed-length sequence input of 32 frames per LUS video, and it is constrained to work only on videos as inputs of the same length during inference. This limit may impact the model’s ability to generalise to LUS videos with varying frame lengths, potentially limiting adaptability. Therefore, inputs of LUS video exceeding 32 frames require being segmented into multiple chunks (video segments). Future research could investigate the adaptation of LUS videos with variable sequence lengths to handle videos of different durations. Future work could also explore training AI lightweight classifiers for the frame selection process, which could speed up the workflow and improve the model’s accuracy. Furthermore, assessing the model with even larger datasets will be a more rigorous test of generalizability for the model. It will also be interesting to verify whether similar improvements in the performance of this approach can be replicated for other LUS disease classifications beyond IS.

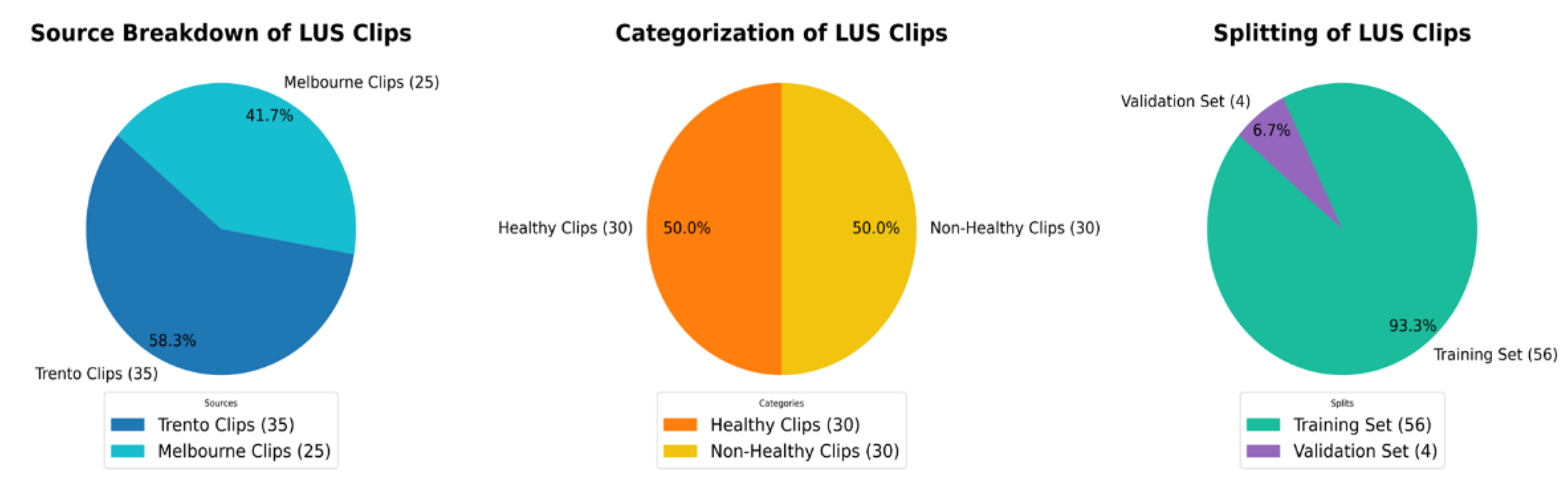

Figure 1.

The above pie charts show the distribution and splitting of the LUS dataset used in this work. Dataset, 58.3% of videos [

35] are from Trento datasets, and 41.7% [

25] are from Melbourne datasets. All videos are equally divided into 50% [

30] healthy and 50% [

30] non-healthy classes. For training and validation, the dataset is split into 93.3% [56] and 6.7% [

4] respectively.

Figure 1.

The above pie charts show the distribution and splitting of the LUS dataset used in this work. Dataset, 58.3% of videos [

35] are from Trento datasets, and 41.7% [

25] are from Melbourne datasets. All videos are equally divided into 50% [

30] healthy and 50% [

30] non-healthy classes. For training and validation, the dataset is split into 93.3% [56] and 6.7% [

4] respectively.

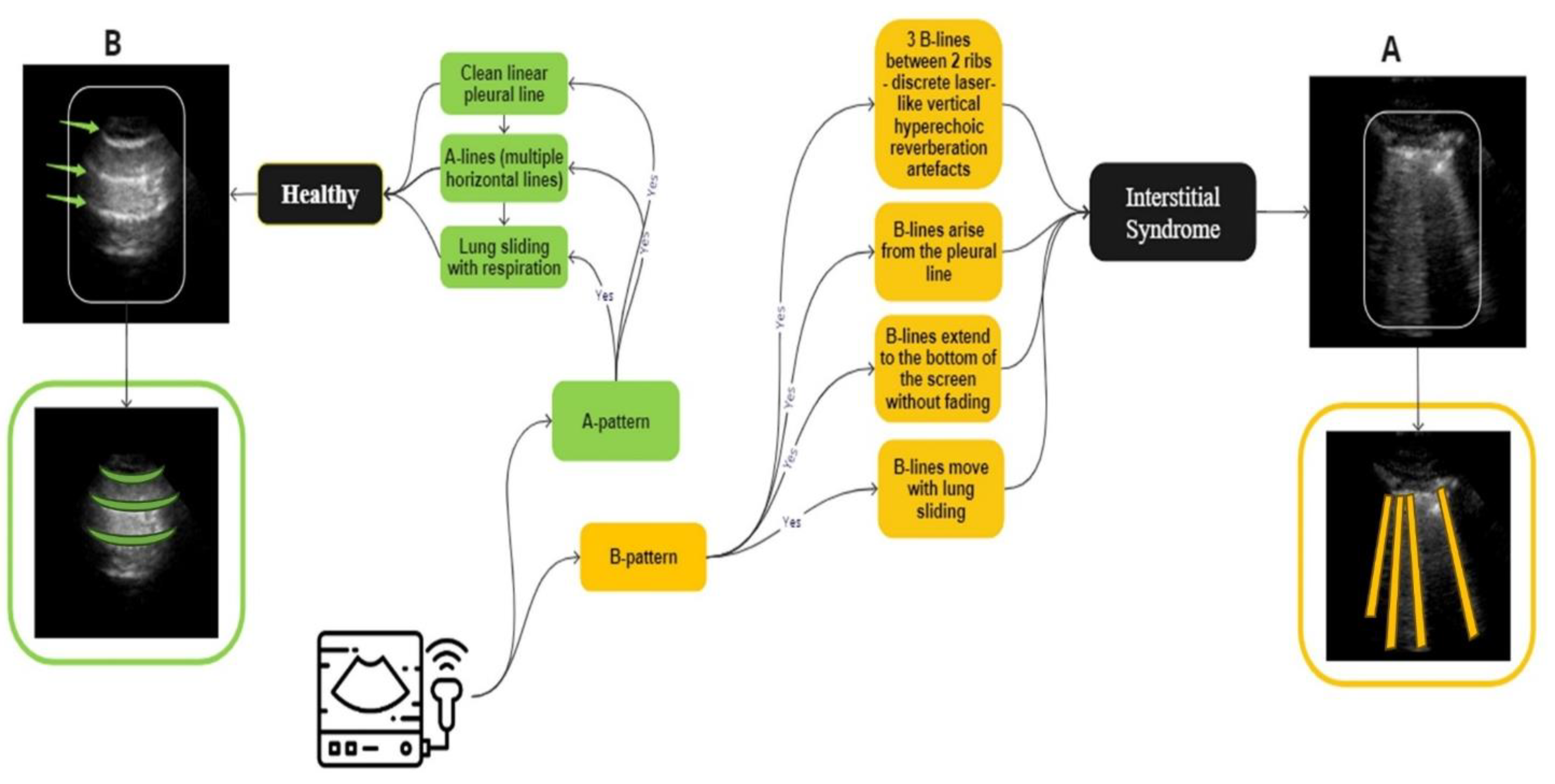

Figure 2.

An overview of the guidelines for identifying IS and normal LUS videos used in the labelling process. A, (marked in yellow), IS is distinguished by the presence of three B-lines. These B-lines are associated with four key characteristics: they move in tandem with lung sliding and lung pulse, extend to the bottom of the screen without fading, and appear laser-like. In contrast, B, representing a healthy lung (marked in green), which is defined by A-lines, which defined as horizontal spaced, echogenic lines that appear below the pleural line.

Figure 2.

An overview of the guidelines for identifying IS and normal LUS videos used in the labelling process. A, (marked in yellow), IS is distinguished by the presence of three B-lines. These B-lines are associated with four key characteristics: they move in tandem with lung sliding and lung pulse, extend to the bottom of the screen without fading, and appear laser-like. In contrast, B, representing a healthy lung (marked in green), which is defined by A-lines, which defined as horizontal spaced, echogenic lines that appear below the pleural line.

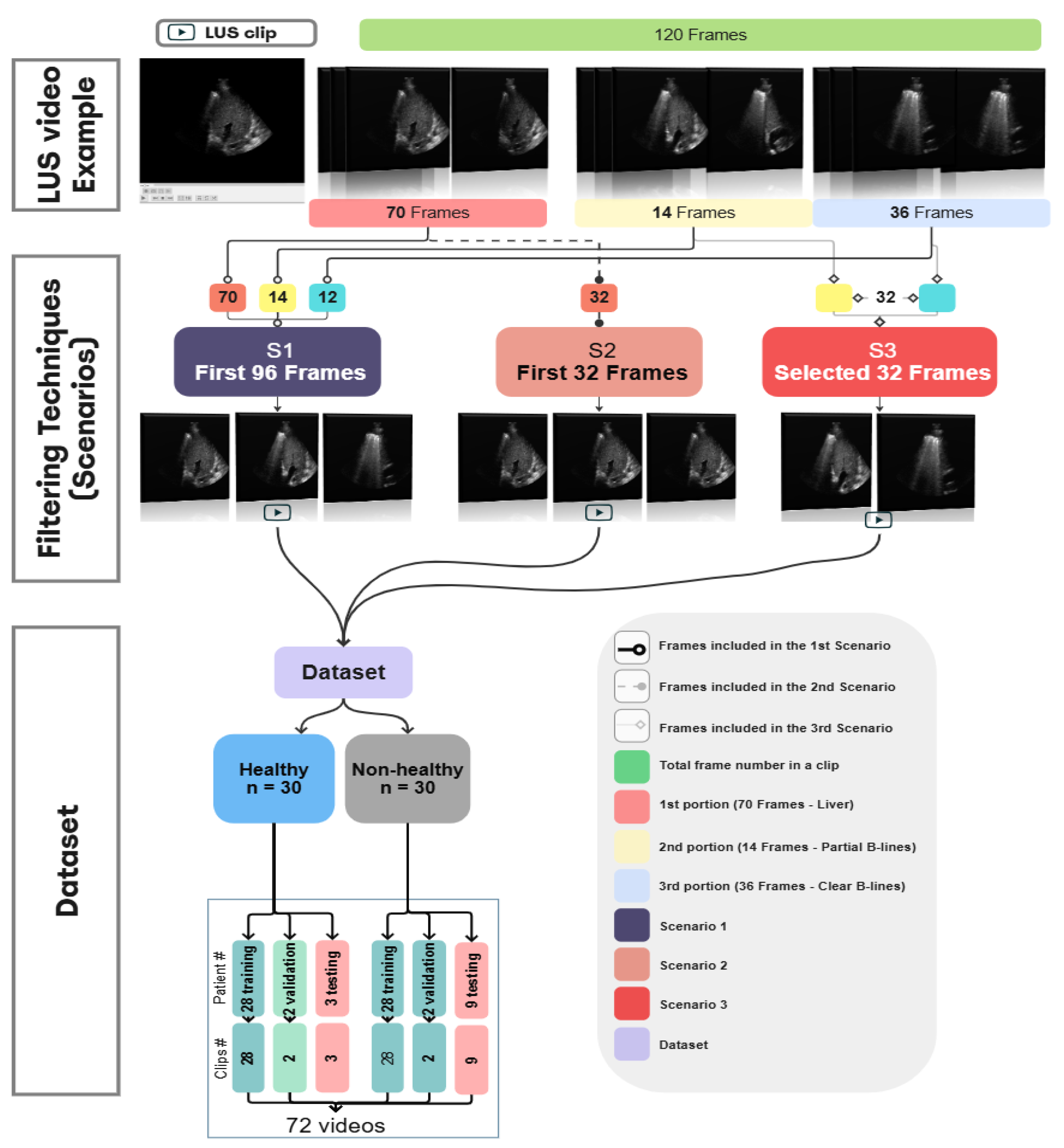

Figure 3.

A three-step process diagram illustrates the selection, filtering, and dataset splitting of Lung LUS videos used in the training of our models. The process begins with an example of 120 frames segmented into multiple portions, followed by applying 3 different scenarios where each one has different types and numbers of frames. This clip, consisting of 120 frames, is selected for illustration purposes and is not representative of all samples in the dataset, as actual video lengths varied. In this example, approximately 70 frames show the liver region, 14 frames include mixed features of liver with partial B-lines images, and 36 frames show clear B-lines. In S1, the first 96 frames cover the liver and the B-line regions. S2 included the first 32 consecutive frames, regardless of anatomical content. S3 targeted 32 diagnostically relevant frames from expert-annotated segments corresponding to liver, partial B-lines, and clear B-lines. These filtered datasets were constructed independently and used separately during model training and evaluation to assess how different temporal sampling strategies influence classification performance.

Figure 3.

A three-step process diagram illustrates the selection, filtering, and dataset splitting of Lung LUS videos used in the training of our models. The process begins with an example of 120 frames segmented into multiple portions, followed by applying 3 different scenarios where each one has different types and numbers of frames. This clip, consisting of 120 frames, is selected for illustration purposes and is not representative of all samples in the dataset, as actual video lengths varied. In this example, approximately 70 frames show the liver region, 14 frames include mixed features of liver with partial B-lines images, and 36 frames show clear B-lines. In S1, the first 96 frames cover the liver and the B-line regions. S2 included the first 32 consecutive frames, regardless of anatomical content. S3 targeted 32 diagnostically relevant frames from expert-annotated segments corresponding to liver, partial B-lines, and clear B-lines. These filtered datasets were constructed independently and used separately during model training and evaluation to assess how different temporal sampling strategies influence classification performance.

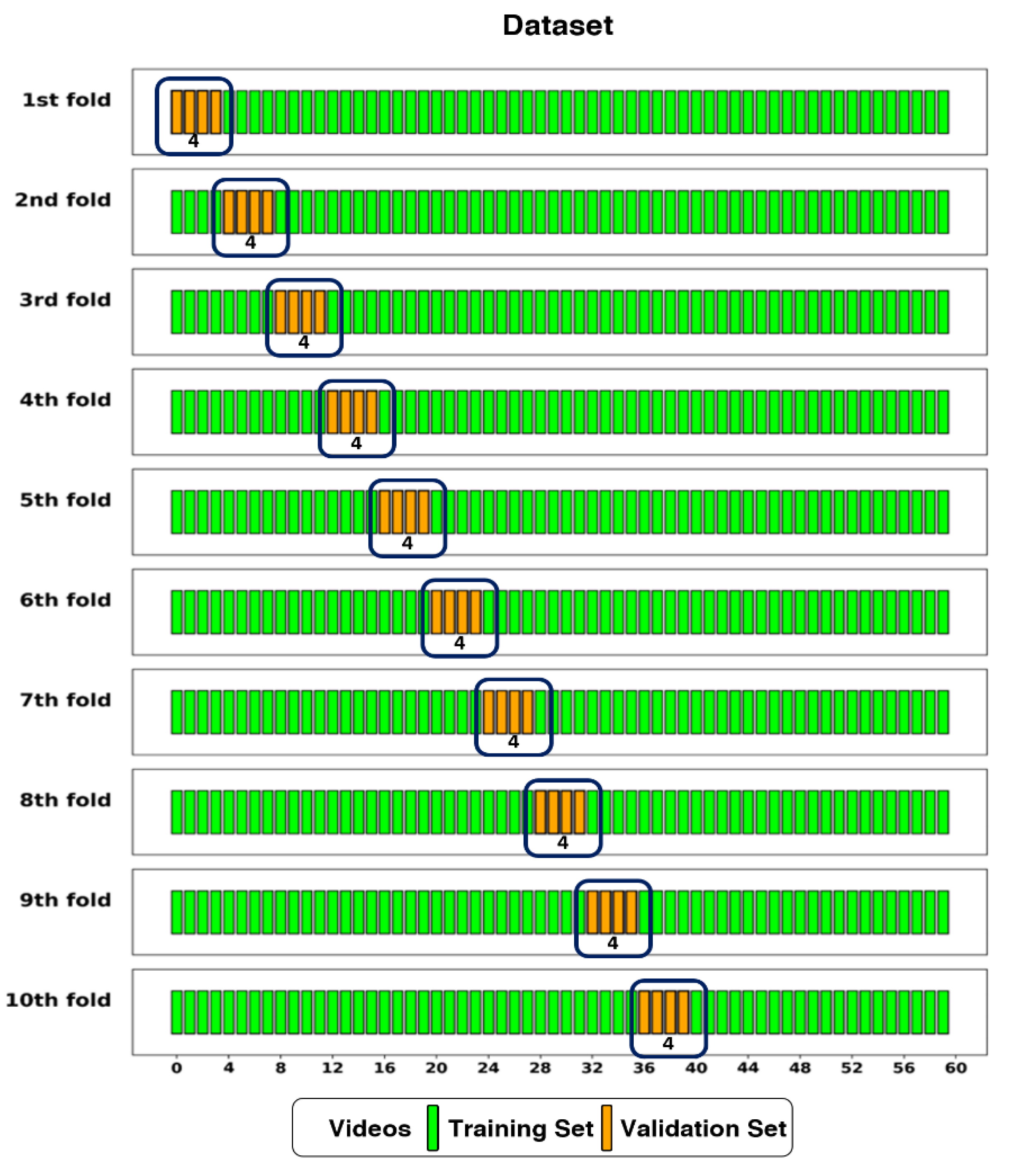

Figure 4.

The dataset split into training and validation sets using 10-fold cross-validation. The Dataset had 56 videos (one per patient) assigned to the training set, and 4 videos to the validation set in each fold.

Figure 4.

The dataset split into training and validation sets using 10-fold cross-validation. The Dataset had 56 videos (one per patient) assigned to the training set, and 4 videos to the validation set in each fold.

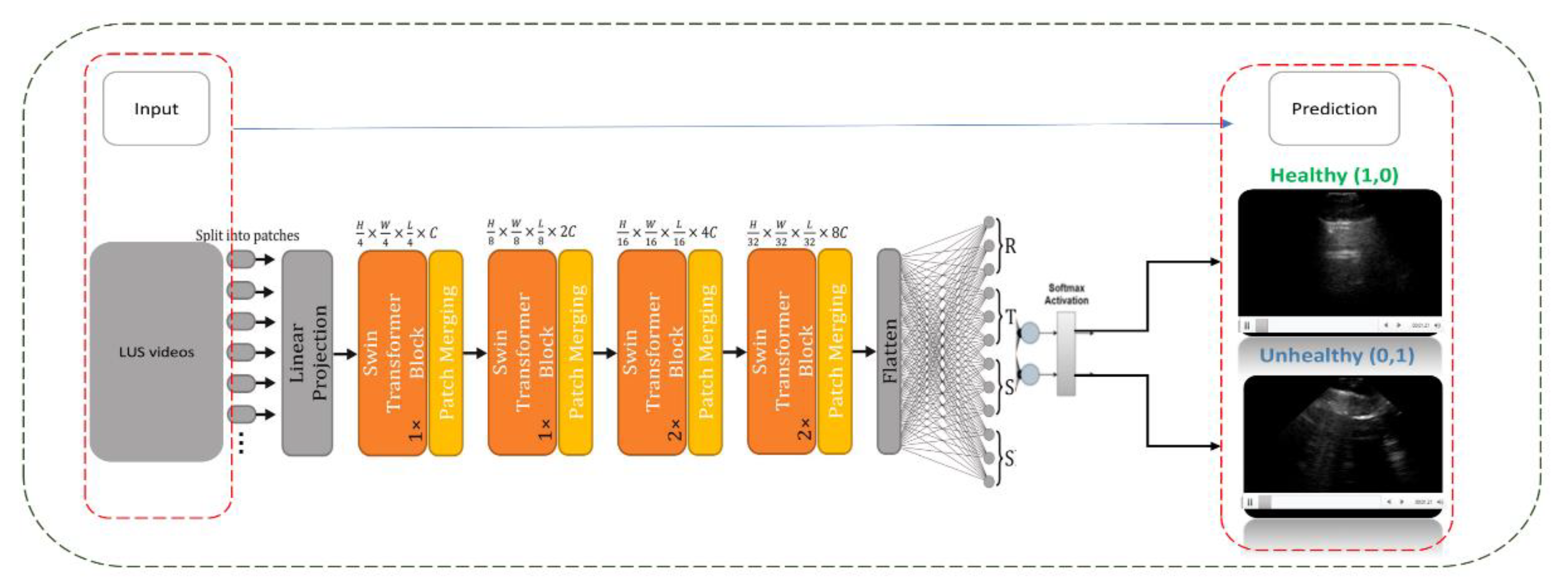

Figure 5.

This diagram shows the architecture of a CSwin Transformer model applied to Lung Ultrasound (LUS) video training. The input LUS videos are segmented into patches and processed through a series of transformer blocks and patch merging operations. The model output is a binary classification, identifying the lung condition as either ‘Healthy’ or ‘Unhealthy’ based on SoftMax activation.

Figure 5.

This diagram shows the architecture of a CSwin Transformer model applied to Lung Ultrasound (LUS) video training. The input LUS videos are segmented into patches and processed through a series of transformer blocks and patch merging operations. The model output is a binary classification, identifying the lung condition as either ‘Healthy’ or ‘Unhealthy’ based on SoftMax activation.

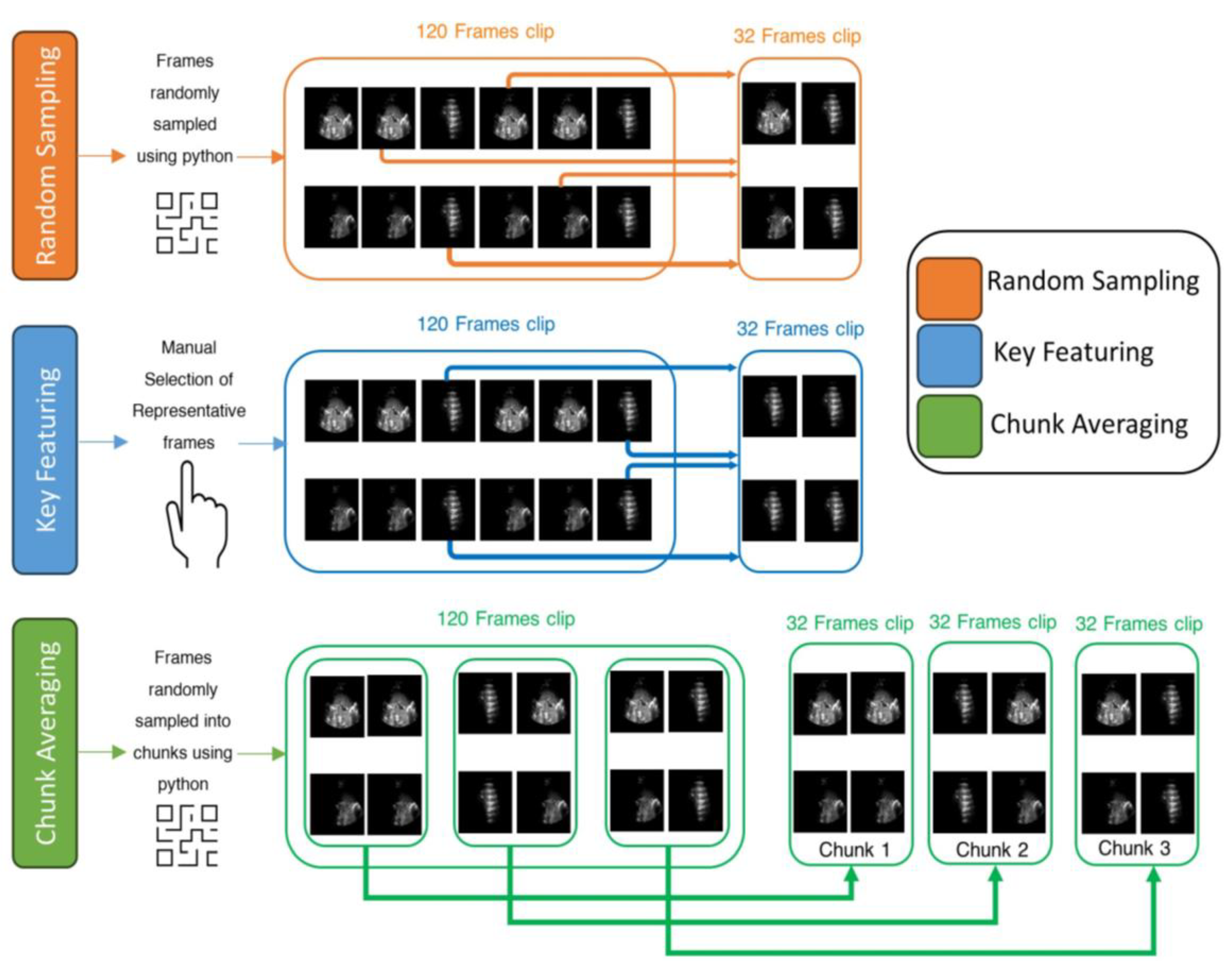

Figure 6.

An example of three frame selection methods for testing: Random Sampling (orange), Key Featuring (blue), and Chunk Averaging (green), applied to an example video of 120-frame.

Figure 6.

An example of three frame selection methods for testing: Random Sampling (orange), Key Featuring (blue), and Chunk Averaging (green), applied to an example video of 120-frame.

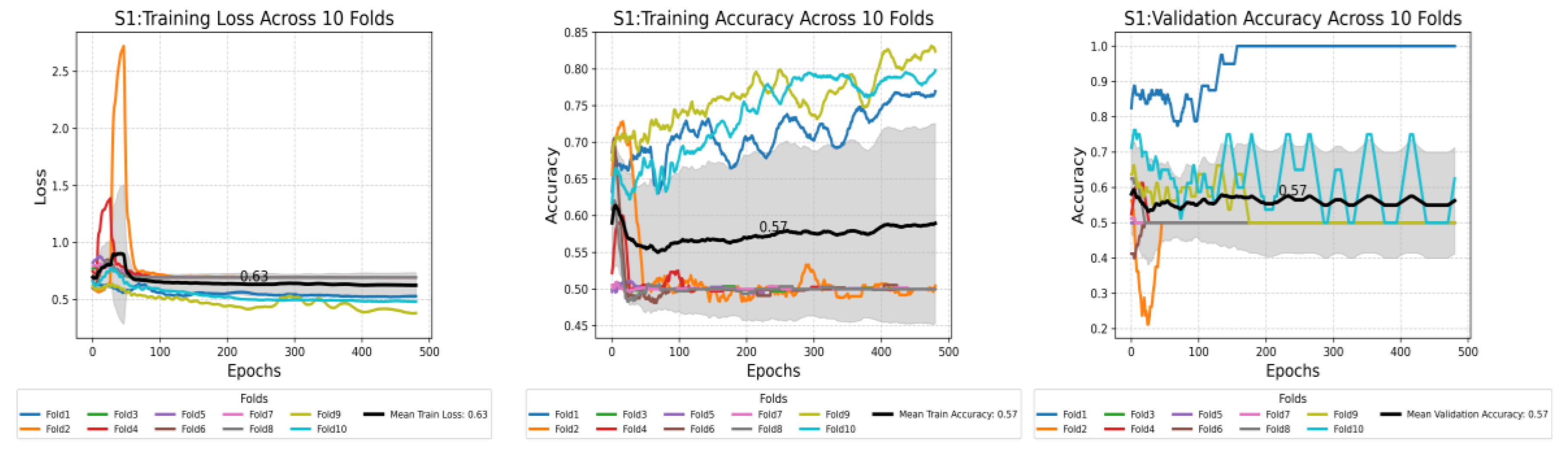

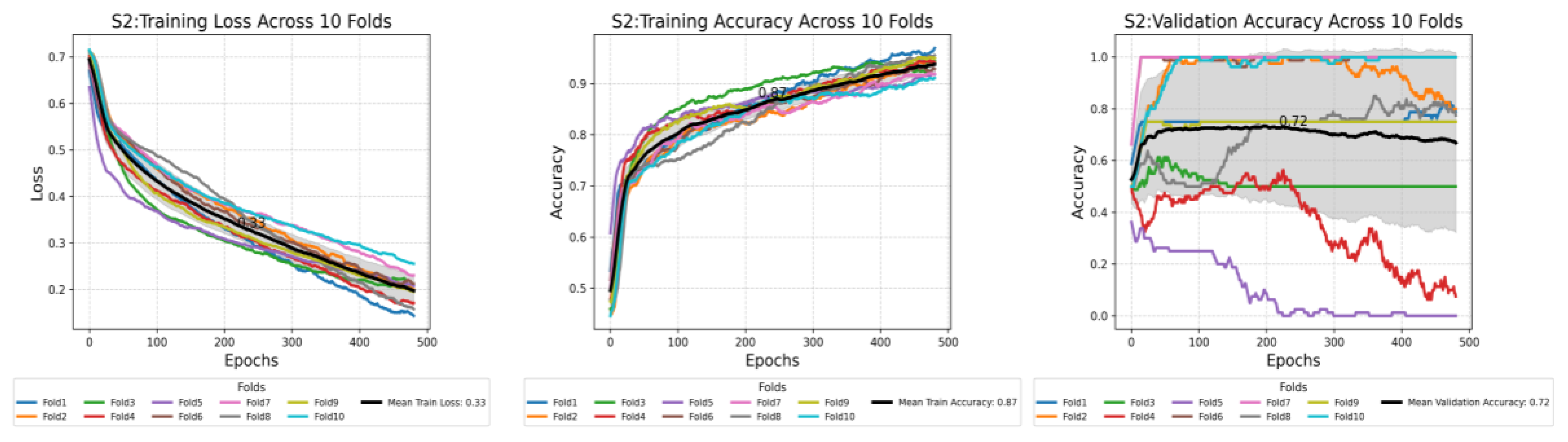

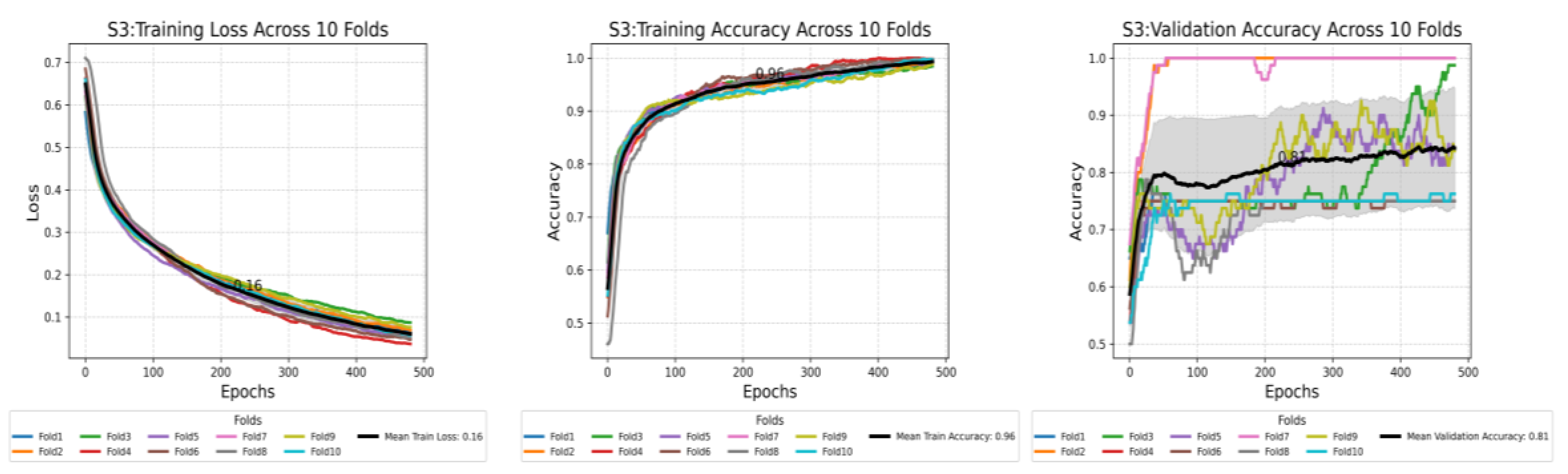

Figure 7.

This plot shows the compression of training loss (a), training accuracy (b), and validation accuracy (c) against three different scenarios used in this study. Each plot displays the average performance metric over 500 epochs, with the shaded area representing the standard deviation. Furthermore, each plot displays all the values at the midpoint epoch for each scenario, along with legends, to facilitate easy reference to the values.

Figure 7.

This plot shows the compression of training loss (a), training accuracy (b), and validation accuracy (c) against three different scenarios used in this study. Each plot displays the average performance metric over 500 epochs, with the shaded area representing the standard deviation. Furthermore, each plot displays all the values at the midpoint epoch for each scenario, along with legends, to facilitate easy reference to the values.

Figure 8.

Pairwise comparison of mean validation accuracy between scenarios, based on 10-fold cross-validation. Each pair (e.g., S1 vs S2) shows the mean and 95% confidence interval for both scenarios. Scenario 3 outperform Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 with clear non-overlapping intervals, indicating statistically significant differences in performance.

Figure 8.

Pairwise comparison of mean validation accuracy between scenarios, based on 10-fold cross-validation. Each pair (e.g., S1 vs S2) shows the mean and 95% confidence interval for both scenarios. Scenario 3 outperform Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 with clear non-overlapping intervals, indicating statistically significant differences in performance.

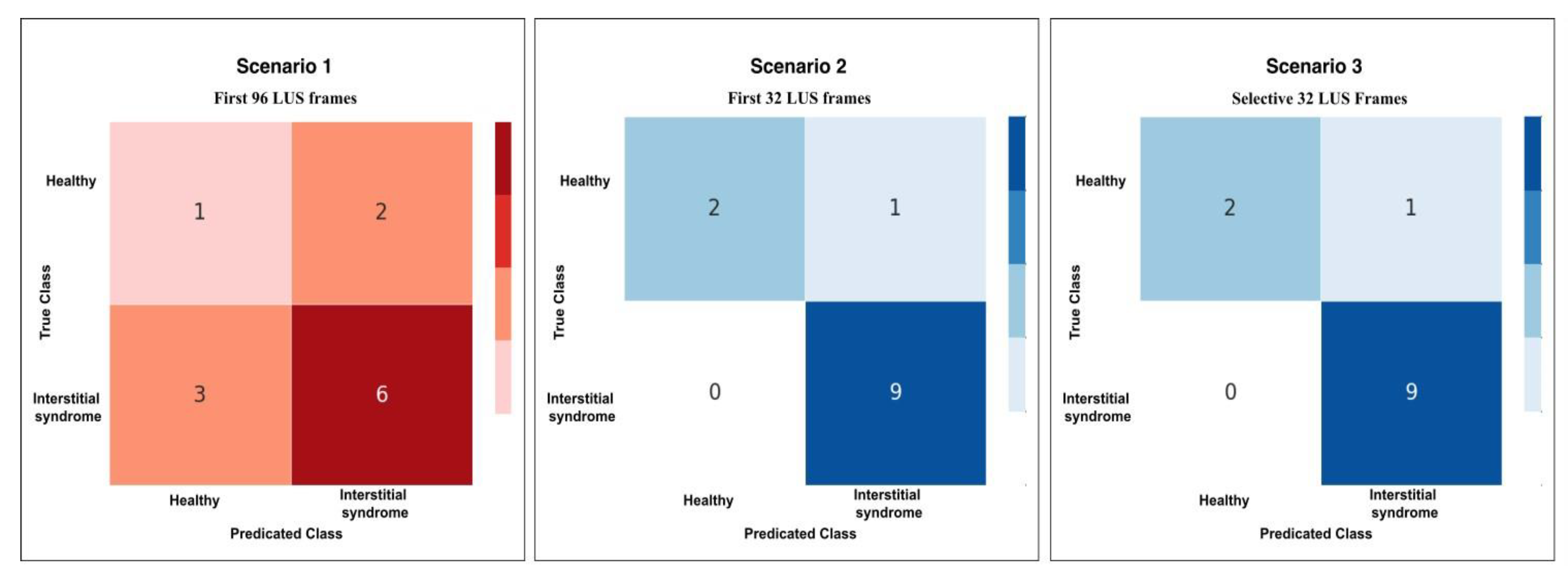

Figure 9.

This plot shows the confusion matrix of the best trained model on the unseen test set of 12 videos (3 healthy and 9 non-healthy) within three training scenarios: From left, Scenario 1 with 5 misclassifications, medial, Scenario 2 and 3 with 1 misclassification.

Figure 9.

This plot shows the confusion matrix of the best trained model on the unseen test set of 12 videos (3 healthy and 9 non-healthy) within three training scenarios: From left, Scenario 1 with 5 misclassifications, medial, Scenario 2 and 3 with 1 misclassification.

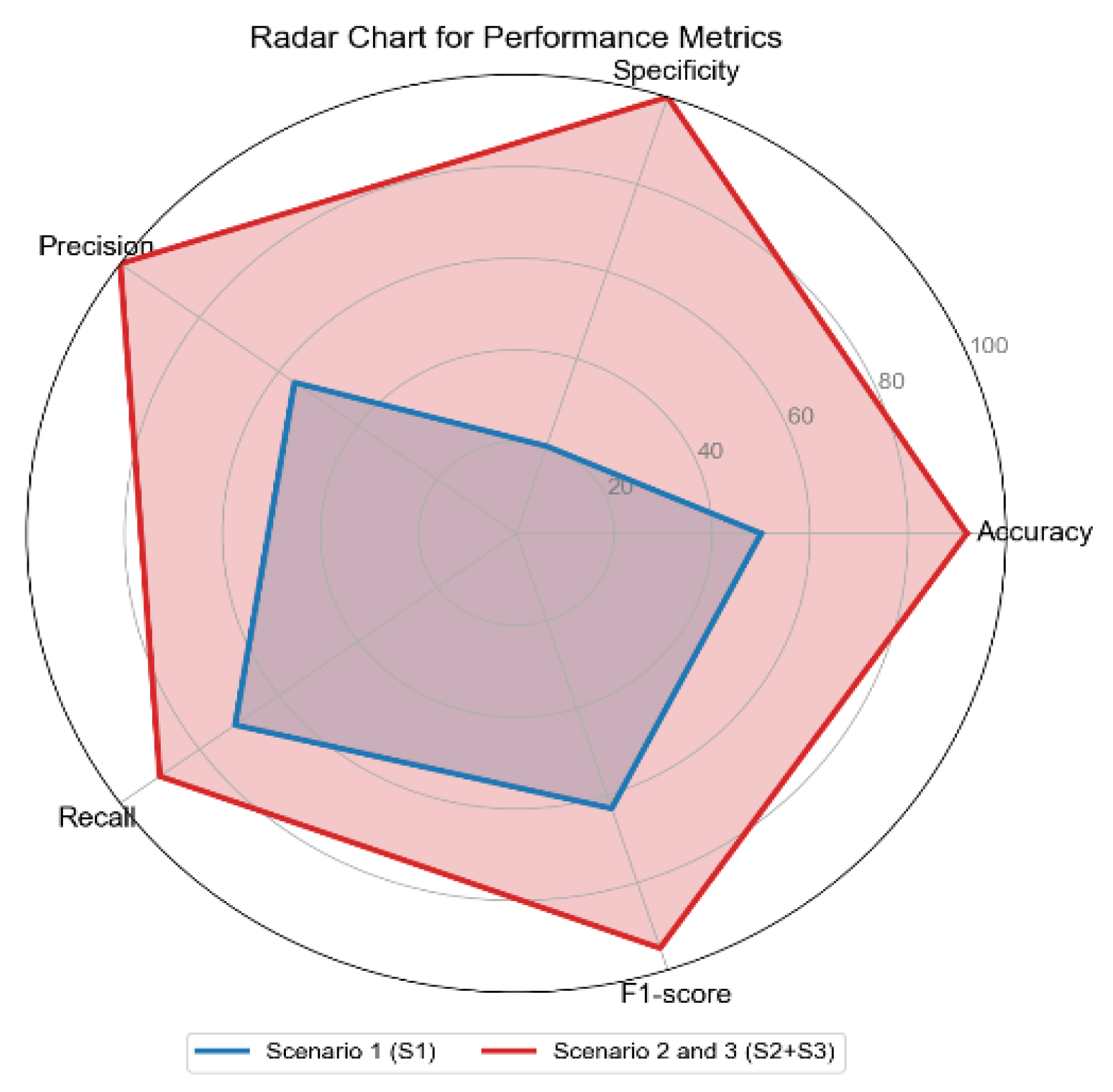

Figure 10.

The radar chart shows the performance metrics for all scenarios: Scenario 1 (S1), Scenario 2 and 3 combined (S2+S3), across performance metrics: Accuracy, Specificity, Precision, Recall, and F1-score.

Figure 10.

The radar chart shows the performance metrics for all scenarios: Scenario 1 (S1), Scenario 2 and 3 combined (S2+S3), across performance metrics: Accuracy, Specificity, Precision, Recall, and F1-score.

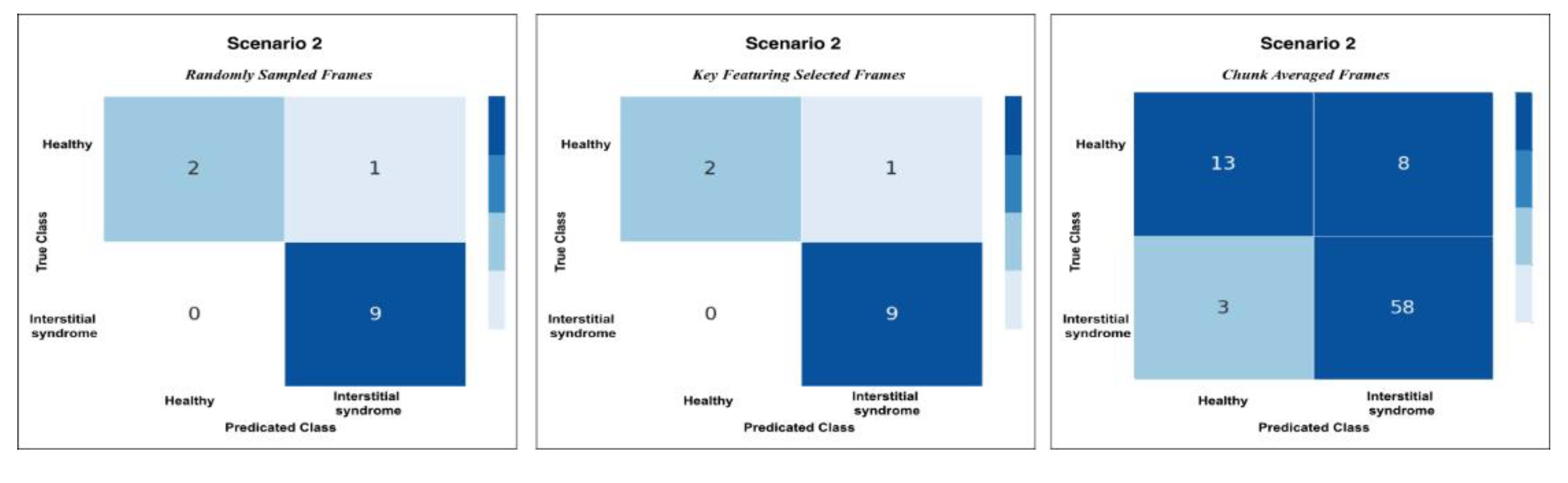

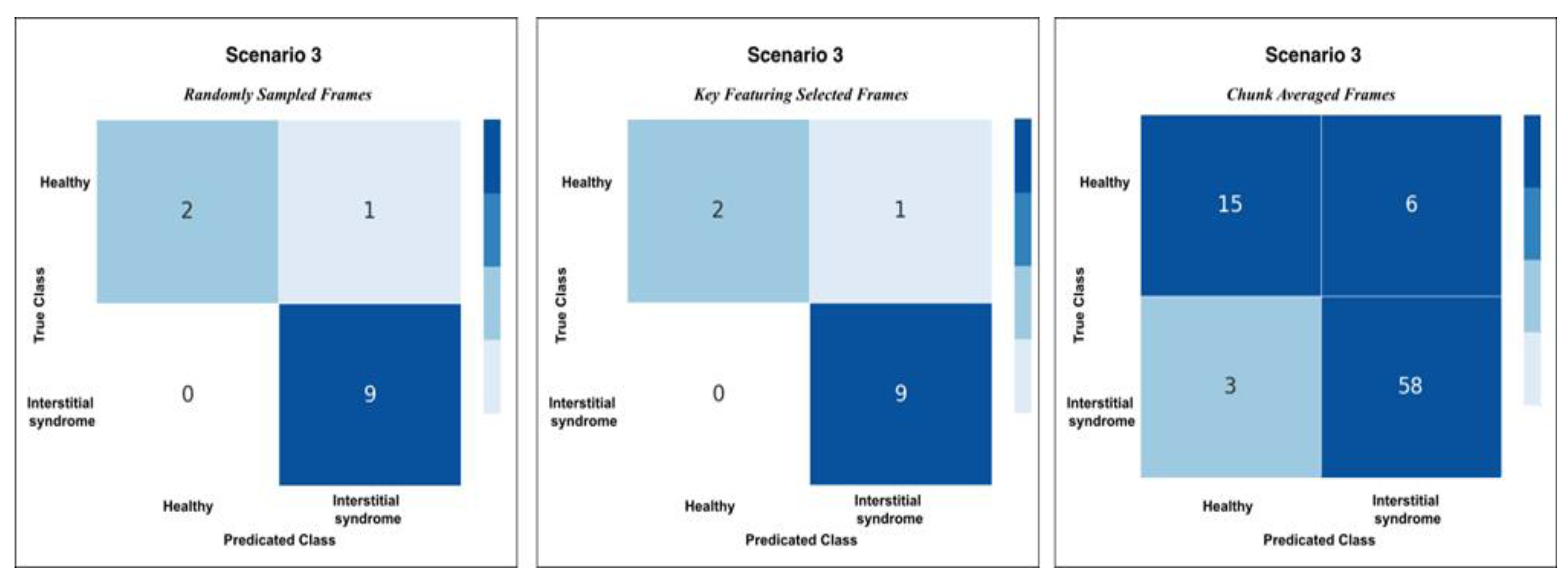

Figure 11.

Confusion matrices for Scenario 3 using the three methods of testing; RS, KF, and CA methods. Both RS and KF achieved 92% accuracy classification, while CA, showed minor misclassifications with an accuracy 89%.

Figure 11.

Confusion matrices for Scenario 3 using the three methods of testing; RS, KF, and CA methods. Both RS and KF achieved 92% accuracy classification, while CA, showed minor misclassifications with an accuracy 89%.

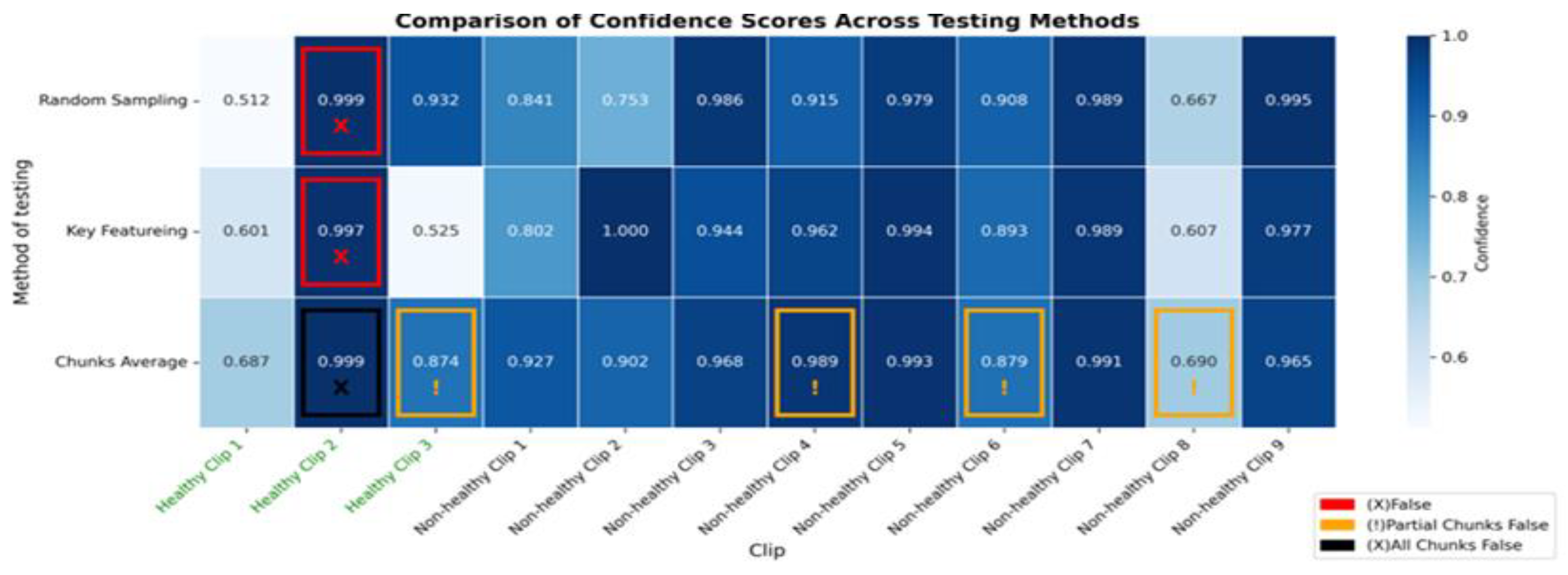

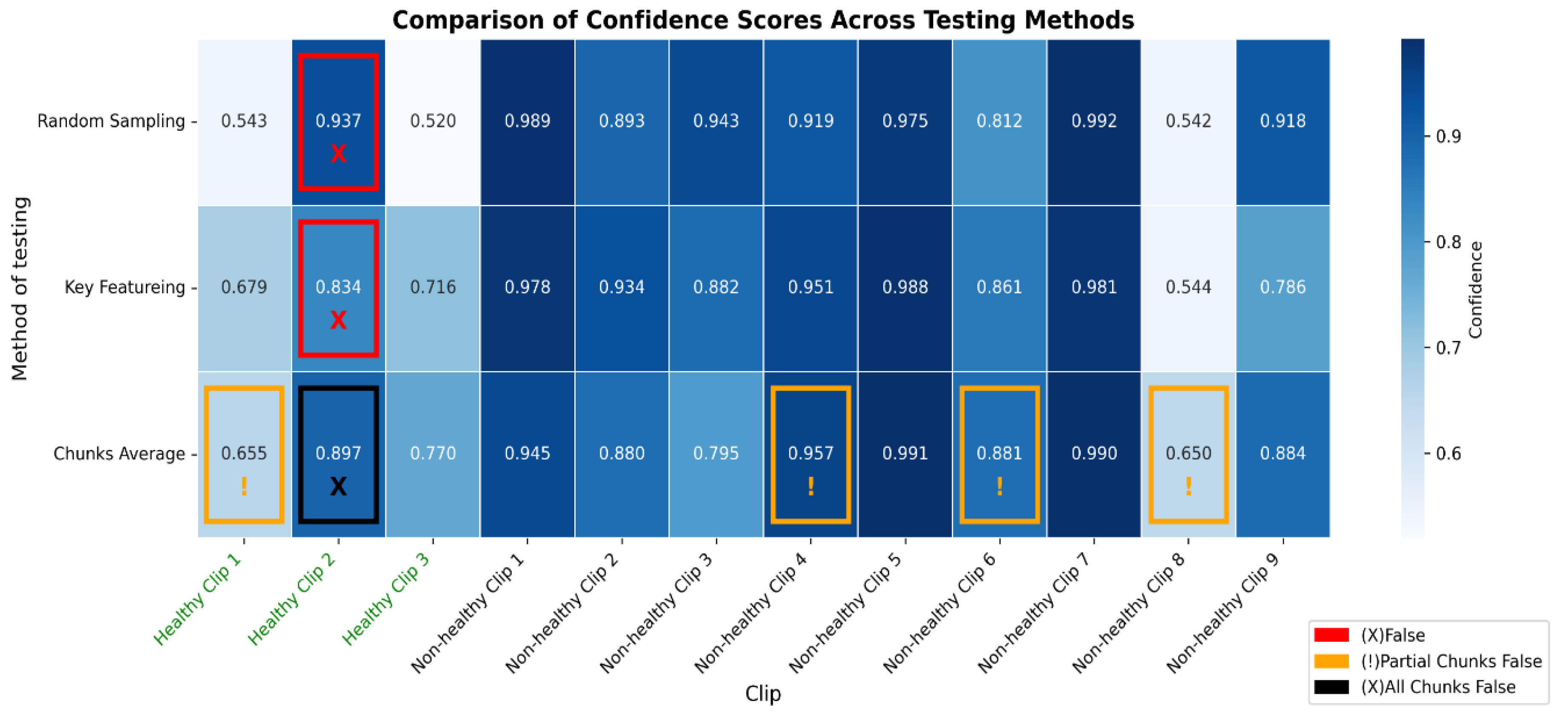

Figure 12.

The heatmap provides a comparison of confidence scores across three different testing methods—RS, KF, and CA—applied to both healthy and non-healthy videos. Each square in the heatmap shows how confident the model was in its misclassifications for each video using the corresponding method. Darker shades of blue represent higher confidence levels (~0.7 to 1.0), while lighter shades indicate lower confidence (~0.5 to 0.7). The colour legend at the bottom indicates false (red), partial false (orange), and completely false chunks (black).

Figure 12.

The heatmap provides a comparison of confidence scores across three different testing methods—RS, KF, and CA—applied to both healthy and non-healthy videos. Each square in the heatmap shows how confident the model was in its misclassifications for each video using the corresponding method. Darker shades of blue represent higher confidence levels (~0.7 to 1.0), while lighter shades indicate lower confidence (~0.5 to 0.7). The colour legend at the bottom indicates false (red), partial false (orange), and completely false chunks (black).

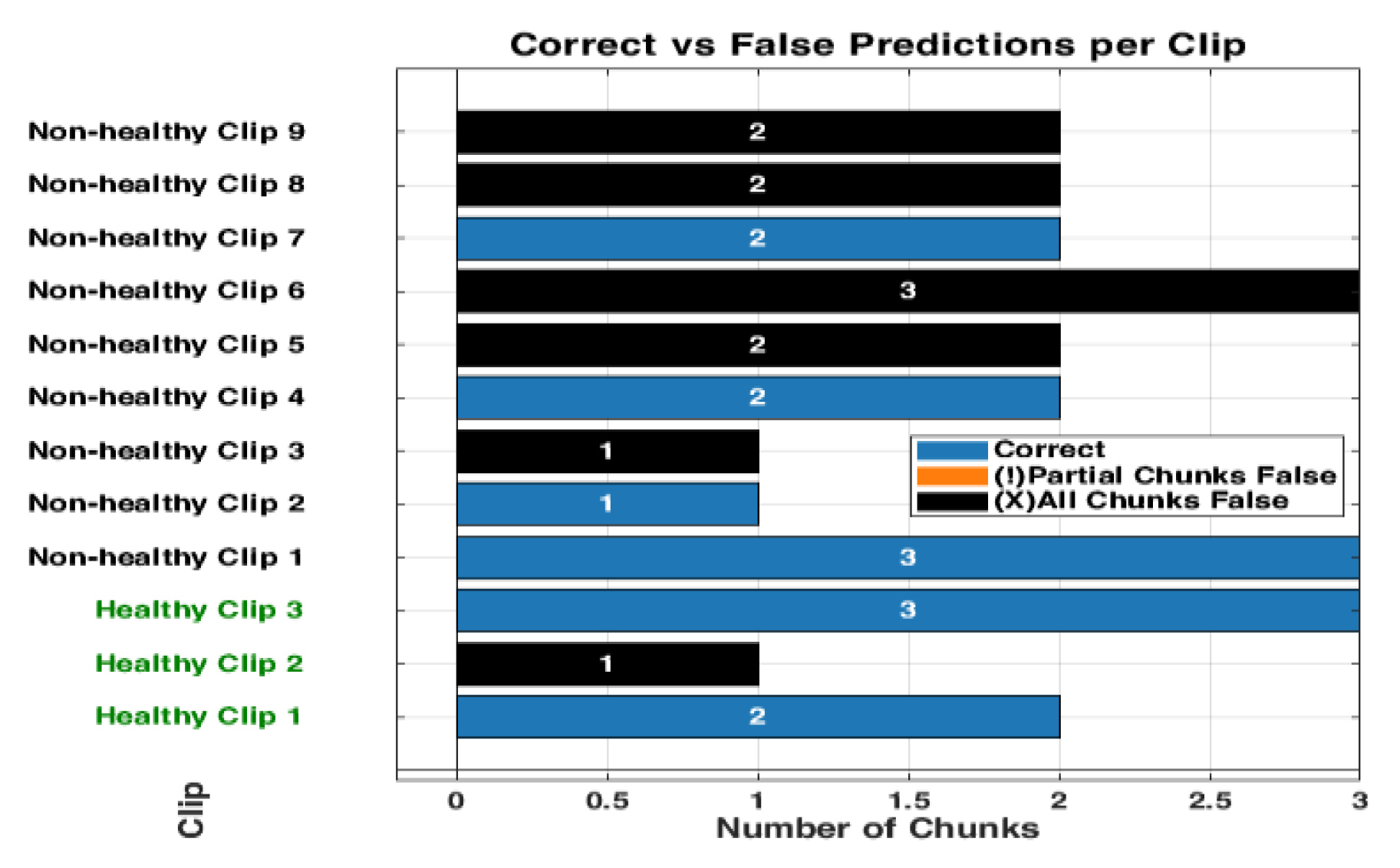

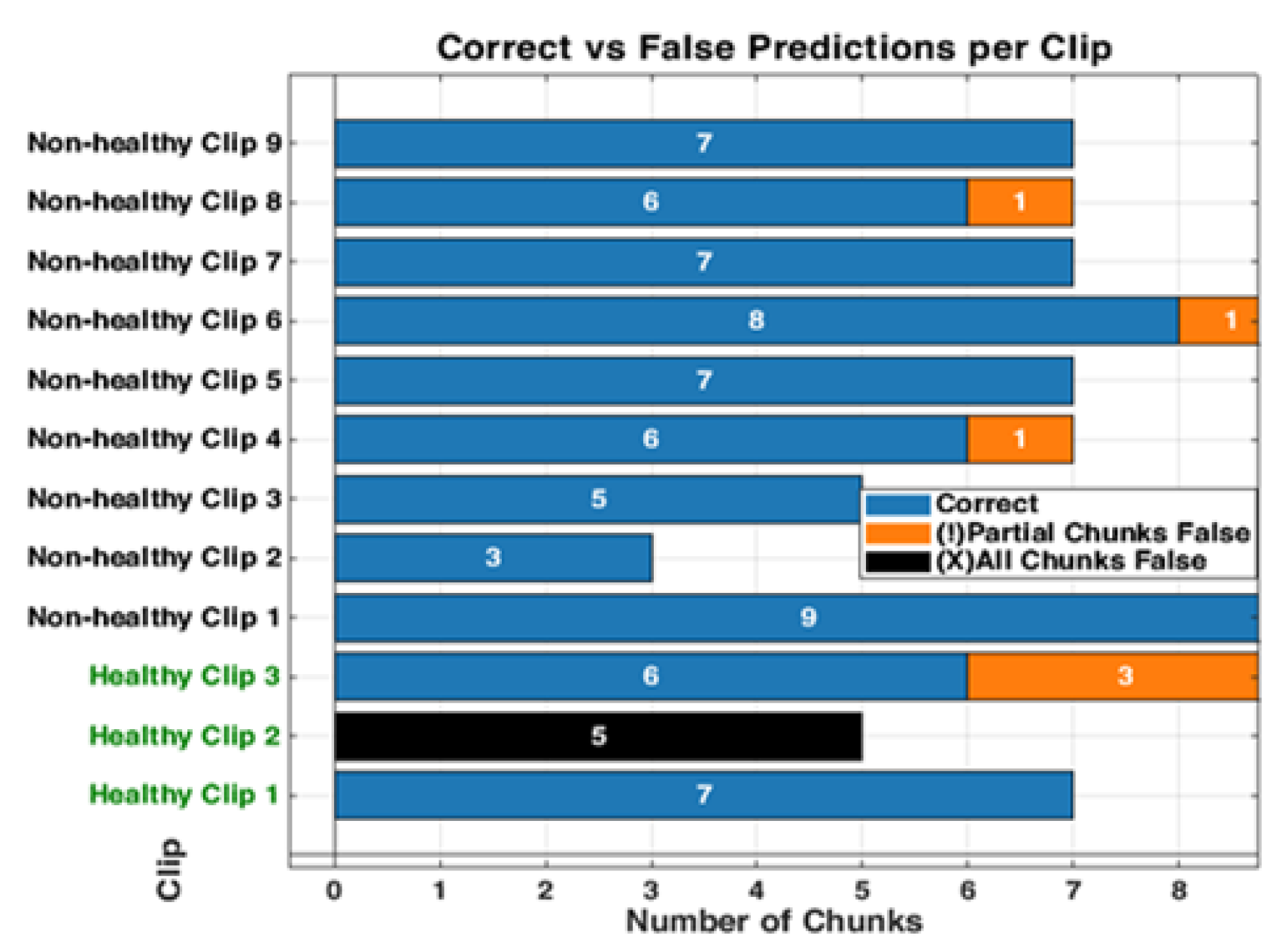

Figure 13.

The bar graph shows the classification performance on 12 testing videos. Each of those bars is segmented to present each chunk, showing the correct classifications in blue and partial misclassifications in orange, and all chunks false in black. The horizontal axis defines the number of chunks, while the vertical axis enumerates the videos that belong either to a healthy or non-healthy video. The orange segments are to indicate where certain chunks in a video are misclassified, while the blue segments reflect the correctly classified segments.

Figure 13.

The bar graph shows the classification performance on 12 testing videos. Each of those bars is segmented to present each chunk, showing the correct classifications in blue and partial misclassifications in orange, and all chunks false in black. The horizontal axis defines the number of chunks, while the vertical axis enumerates the videos that belong either to a healthy or non-healthy video. The orange segments are to indicate where certain chunks in a video are misclassified, while the blue segments reflect the correctly classified segments.

Figure 14.

The figure shows examples of misclassifications for testing LUS videos. The blue bars represent correctly classified chunks in each video, while the orange boxes show the chunks that were misclassified by the model. LUS frames from chuck, non-healthy video 8 and video 4, (labelled “a” and “b” respectively), the model correctly classified most chunks in video 8 but flagged one chunk incorrectly and displays frames with visible B-lines (indicative of IS). In non-healthy video 4 (labelled “b”), which LUS frames show a nearly empty and no diagnostic features found, the model misclassified one chunk. In Healthy video 2 (labelled c), the model misclassified all chunks, as shown by the black bar. The LUS frames from this video display A-Lines artefacts.

Figure 14.

The figure shows examples of misclassifications for testing LUS videos. The blue bars represent correctly classified chunks in each video, while the orange boxes show the chunks that were misclassified by the model. LUS frames from chuck, non-healthy video 8 and video 4, (labelled “a” and “b” respectively), the model correctly classified most chunks in video 8 but flagged one chunk incorrectly and displays frames with visible B-lines (indicative of IS). In non-healthy video 4 (labelled “b”), which LUS frames show a nearly empty and no diagnostic features found, the model misclassified one chunk. In Healthy video 2 (labelled c), the model misclassified all chunks, as shown by the black bar. The LUS frames from this video display A-Lines artefacts.

Figure 15.

This figure compares the inference time performance between a dual-GPU setup and an Intel Core i7 CPU when processing 32-frame ultrasound segments. Blue bars indicate the average inference time per segment, while green bars represent the total time required to process 9 segments (equivalent to a 288-frame LUS video). Dashed lines and Δ annotations highlight the differences between per-segment and total processing times. The GPU system achieves real-time performance with an average of 0.87 seconds per segment, whereas the CPU setup requires approximately 7.8 seconds per segment.

Figure 15.

This figure compares the inference time performance between a dual-GPU setup and an Intel Core i7 CPU when processing 32-frame ultrasound segments. Blue bars indicate the average inference time per segment, while green bars represent the total time required to process 9 segments (equivalent to a 288-frame LUS video). Dashed lines and Δ annotations highlight the differences between per-segment and total processing times. The GPU system achieves real-time performance with an average of 0.87 seconds per segment, whereas the CPU setup requires approximately 7.8 seconds per segment.

Table 1.

This table shows how patients and videos were divided into training, validation, and testing sets.

Table 1.

This table shows how patients and videos were divided into training, validation, and testing sets.

| Healthy Patients (H) |

Non-healthy Patients (NH) |

Training Set |

Validation Set |

Testing Set (Unseen) |

Total |

| % |

no |

% |

no |

% |

no |

Videos/ Patients |

| 33 |

39 |

≈ 78% |

56

(26H + 26NH) |

≈ 6 % |

4

(2H + 2NH) |

≈ 17 % |

12

(3H +9 NH) |

72 |

Table 2.

presents the mean validation accuracy, 95% confidence intervals, and pairwise statistical comparisons between the 3 scenarios in this work. The best-performing scenario is highlighted in bold.

Table 2.

presents the mean validation accuracy, 95% confidence intervals, and pairwise statistical comparisons between the 3 scenarios in this work. The best-performing scenario is highlighted in bold.

| Scenario |

Mean Accuracy |

95% Confidence

Interval

|

Compared To |

Mean

Difference

|

p-value |

Cohen’s d |

Effect Size Interpretation |

| Scenario 1 |

0.577 |

[0.569, 0.584] |

S2 |

0.127 |

*** |

9.69 |

Extremely large |

| Scenario 2 |

0.704 |

[0.693, 0.715] |

S3 |

0.104 |

*** |

8.54 |

Extremely large |

| Scenario 3 |

0.808 |

[0.802, 0.814] |

S1 |

0.231 |

*** |

24.10 |

Extremely large |

Table 3.

Performance metrics across scenarios (S1–S3).

Table 3.

Performance metrics across scenarios (S1–S3).

| |

Performance metrics |

| Accuracy |

Specificity |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| Scenario 1 (S1) |

50% |

20% |

56% |

71% |

63% |

| Scenario 2 (S2) |

92% |

100% |

100% |

90% |

95% |

| Scenario 3 (S3) |

92% |

100% |

100% |

90% |

95% |