Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Study On Processing Parameters of The Wet Spinning Technique

2.3. Production of Wet Spun PHA Fibres

2.4. Morphological Analyses

2.5. Chemical Analysis

2.6. Thermal Analysis

2.7. Mechanical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of the PHA Fibre Production Process

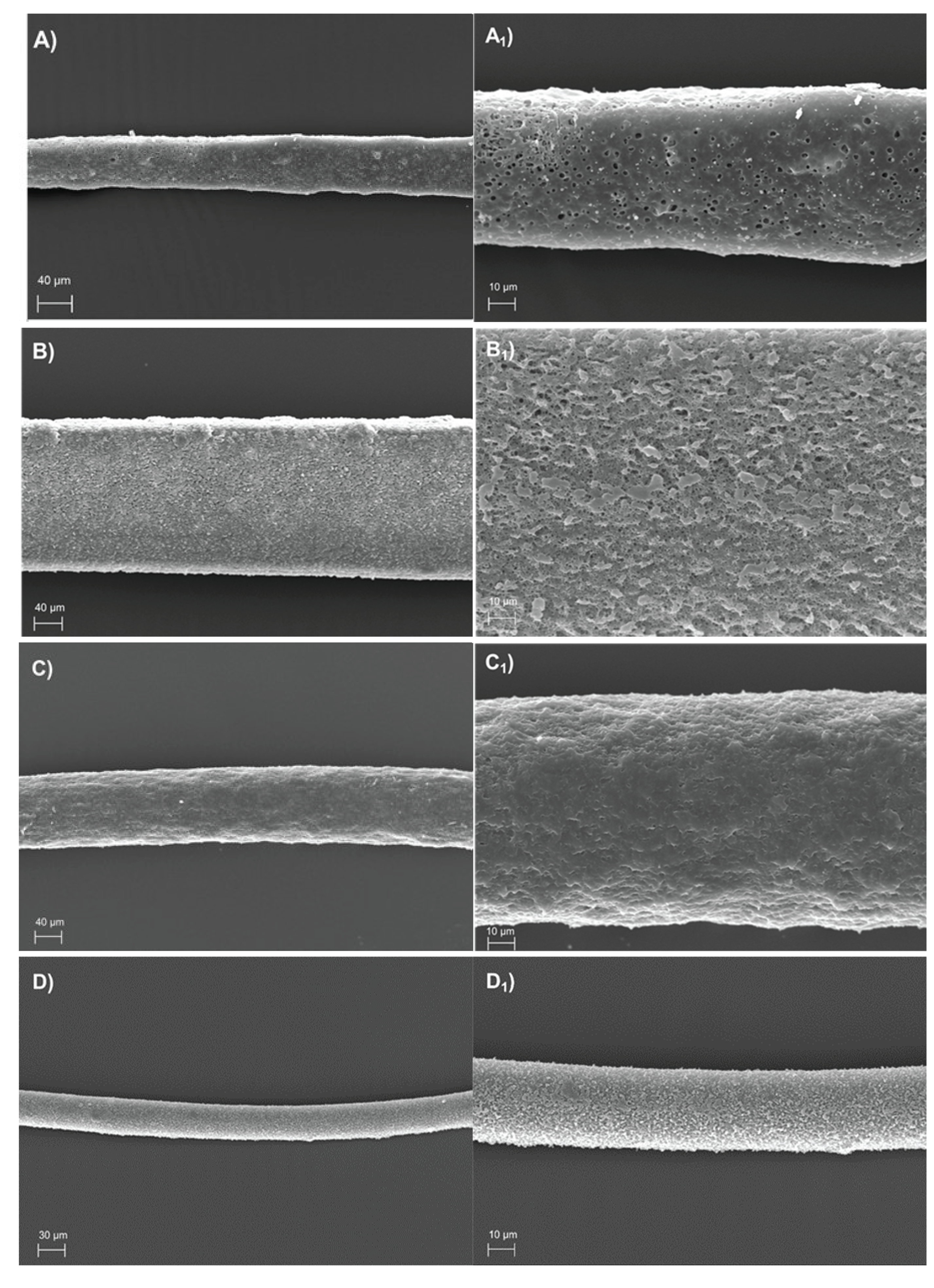

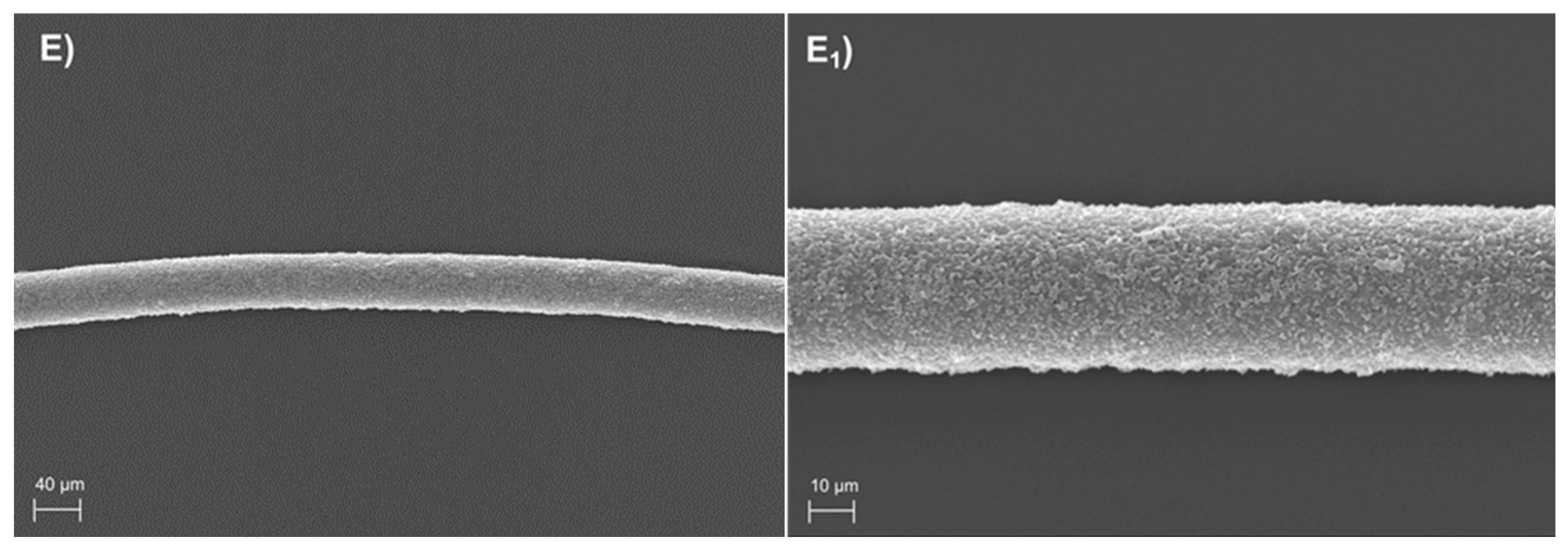

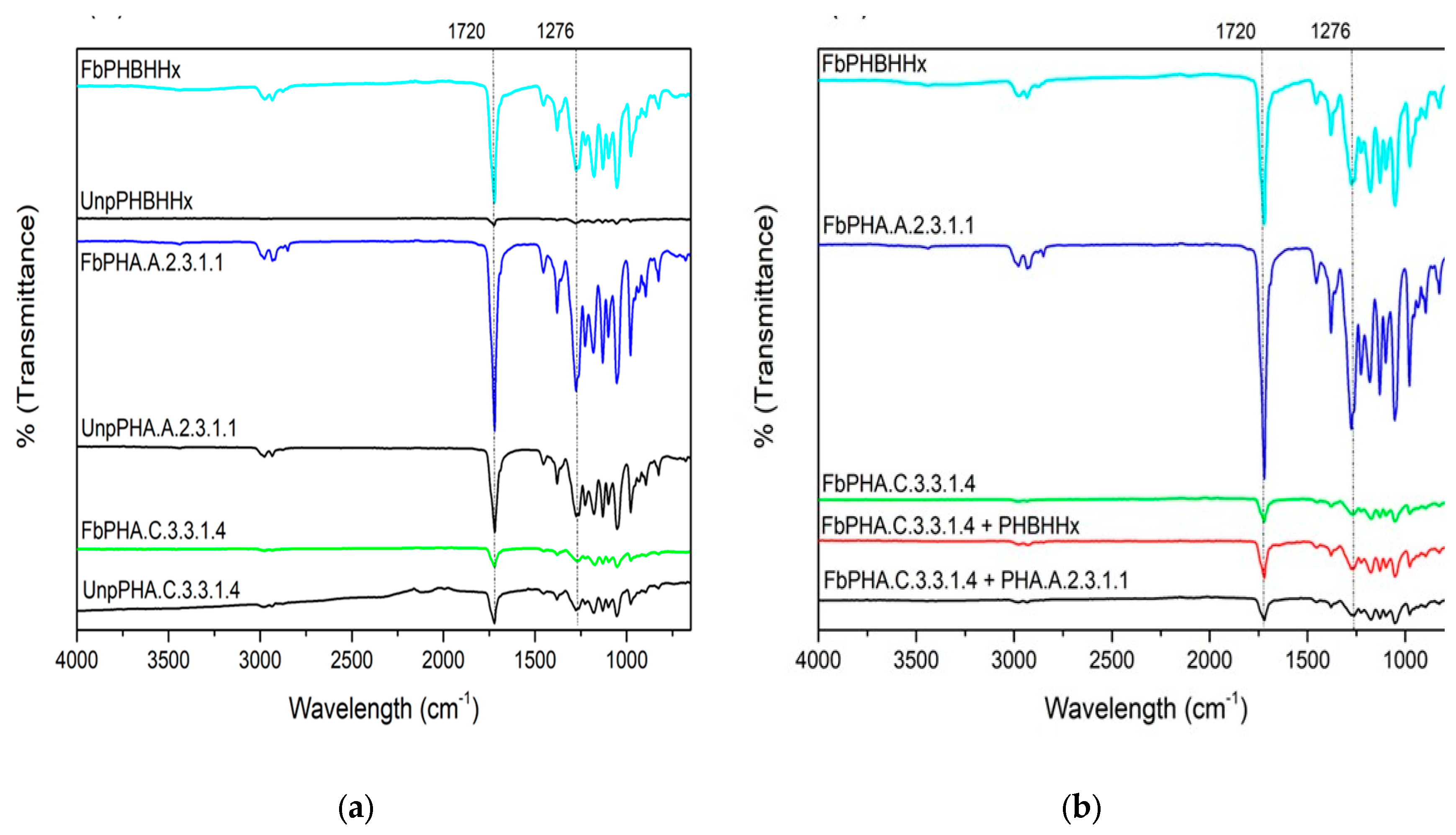

3.2. Morphological and Diameter Analysis of the PHA-Produced Fibres

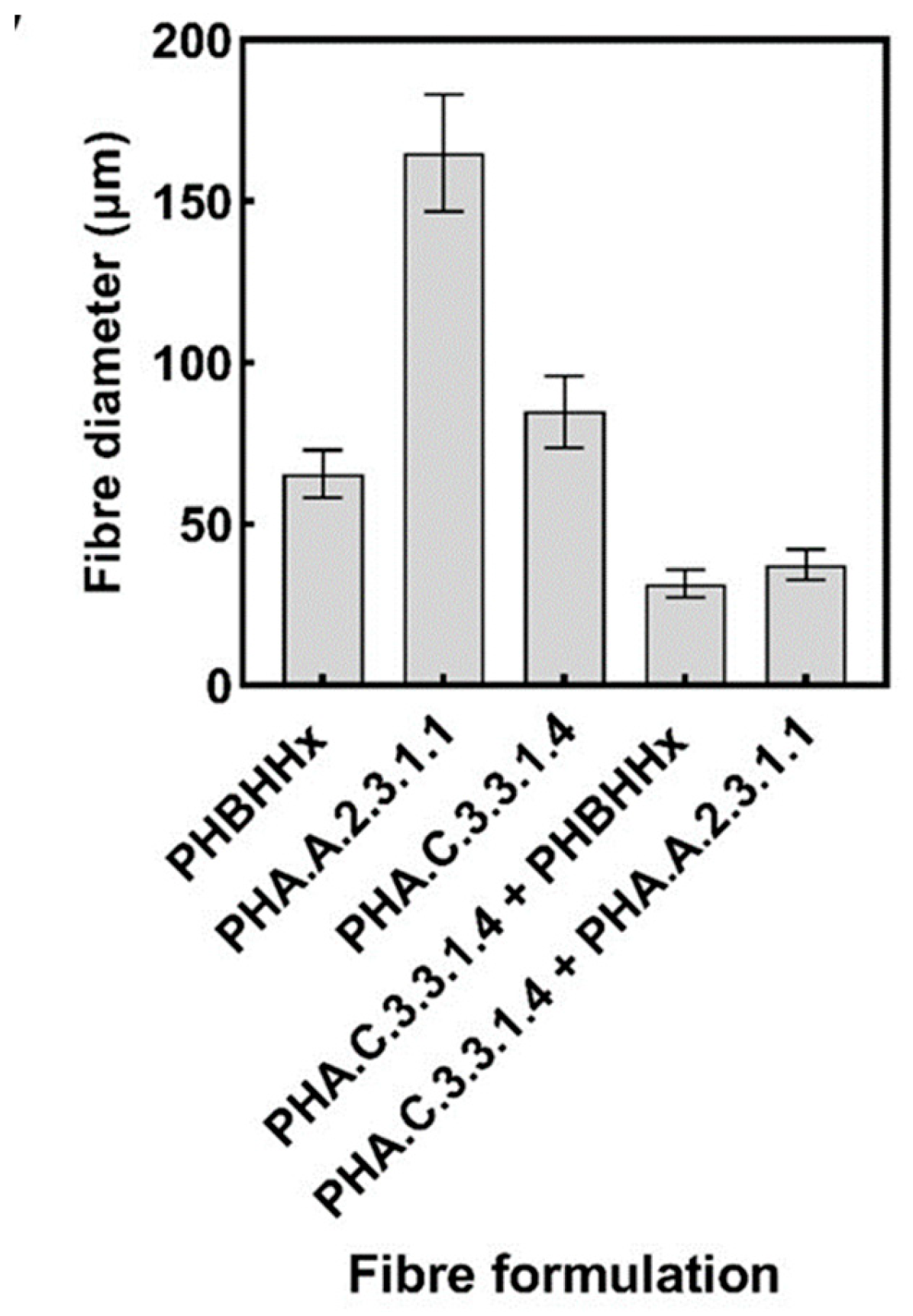

3.3. Chemical Analysis

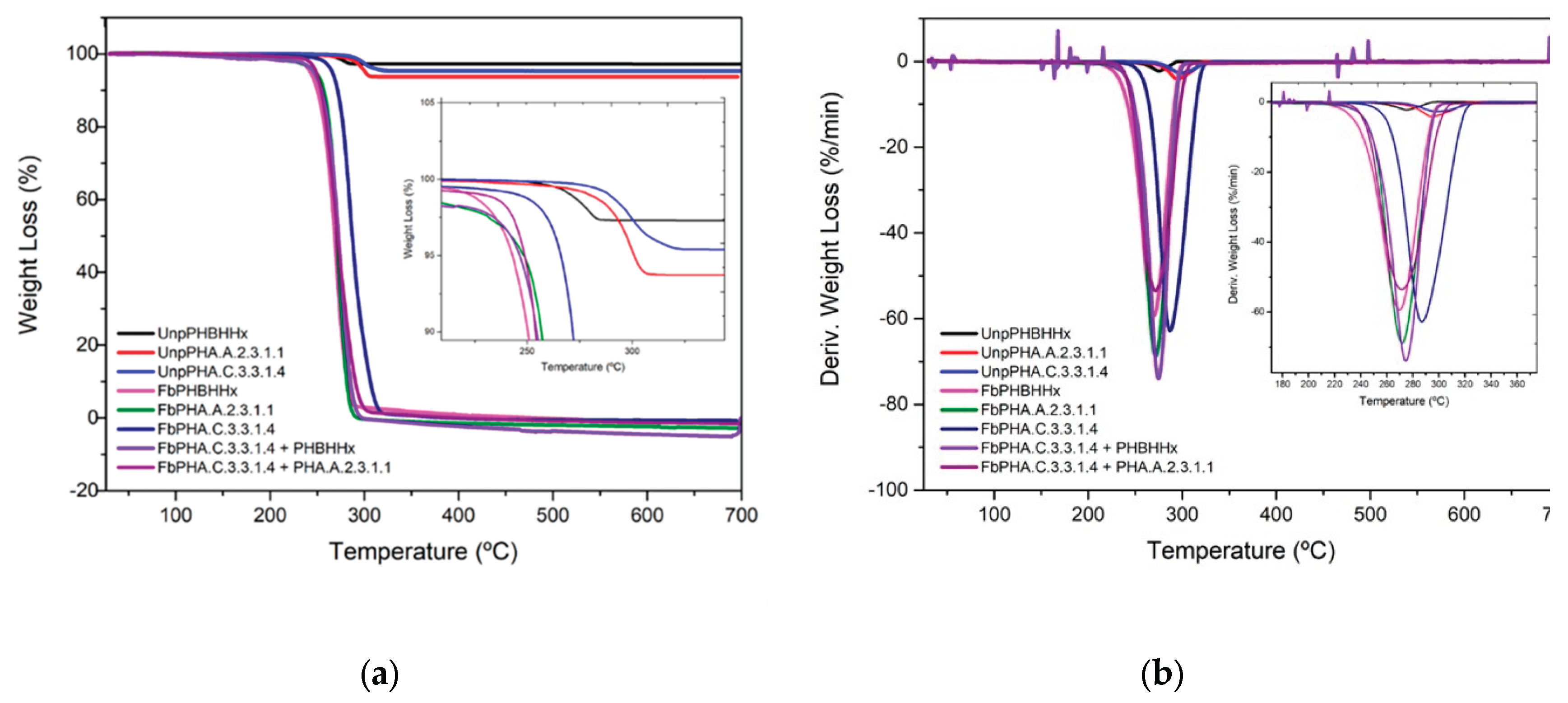

3.4. Thermal Characterization

3.5. Mechanical Properties of the PHAs-Produced Fibres

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayanathara Thathsarani Pilapitiya, P.G.C.; Ratnayake, A.S. The World of Plastic Waste: A Review. Cleaner Materials 2024, 11, 100220. [CrossRef]

- Atiwesh, G.; Mikhael, A.; Parrish, C.C.; Banoub, J.; Le, T.A.T. Environmental Impact of Bioplastic Use: A Review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07918. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Lalnundiki, V.; Shelare, S.D.; Abhishek, G.J.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, D.; Kumar, A.; Abbas, M. An Investigation of the Environmental Implications of Bioplastics: Recent Advancements on the Development of Environmentally Friendly Bioplastics Solutions. Environ Res 2024, 244, 117707. [CrossRef]

- Research, G.V. Bioplastics Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Biodegradable, Non-Biodegradable), By Application, By Region, And Segment Forecasts; 2023;

- Rosenboom, J.G.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Bioplastics for a Circular Economy. Nat Rev Mater 2022, 7, 117–137. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X.; Zhao, Z.-M.; Dong, T.; Anderson, A.; et al. Sustainable Bioplastics Derived from Renewable Natural Resources for Food Packaging. Matter 2023, 6, 97–127. [CrossRef]

- Vanheusden, Chris; Vanminsel, Jan; Reddy, Naveen; Ethirajan, Anitha;Buntinx, M. Fabrication of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) Fibers Using Centrifugal Fiber Spinning: Structure, Properties and Application Potential. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15.

- Siracusa, Valentina and Blanco, I. Polymers Analogous to Petroleum-Derived Ones for Packaging and Engineering Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1641.

- Ali, S.S.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Elsamahy, T.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Li, F.; Kornaros, M.; Zuorro, A.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Bioplastic Production in Terms of Life Cycle Assessment: A State-of-the-Art Review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2023, 15, 100254. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.; Priyadarshanee, M.; Vandana; Das, S. Polyhydroxyalkanoates, the Bioplastics of Microbial Origin: Properties, Biochemical Synthesis, and Their Applications. Chemosphere 2022, 294, 133723. [CrossRef]

- Kaniuk, Ł.; Stachewicz, U. Development and Advantages of Biodegradable PHA Polymers Based on Electrospun PHBV Fibers for Tissue Engineering and Other Biomedical Applications. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2021, 7, 5339–5362. [CrossRef]

- Sanhueza, C.; Acevedo, F.; Rocha, S.; Villegas, P.; Seeger, M.; Navia, R. Polyhydroxyalkanoates as Biomaterial for Electrospun Scaffolds. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 124, 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Naser, A.Z.; Deiab, I.; Darras, B.M. Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) and Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), Green Alternatives to Petroleum-Based Plastics: A Review. RSC Adv 2021, 11, 17151–17196. [CrossRef]

- Madison, L.L.; Huisman, G.W. Metabolic Engineering of Poly(3-Hydroxyalkanoates): From DNA to Plastic. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 1999, 63, 21–53. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Chung, A.-L.; Wu, L.-P.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.-C.; Chen, G.-Q. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoate Block Copolymer P3HB- b -P4HB. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3166–3173. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Cho, I.J.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.Y. Microbial Polyhydroxyalkanoates and Nonnatural Polyesters. Advanced Materials 2020, 32. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Garcia, D.; Fenollar, O.; Fombuena, V.; Lopez-Martinez, J.; Balart, R. Improvement of Mechanical Ductile Properties of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) by Using Vegetable Oil Derivatives. Macromol Mater Eng 2017, 302, 1600330. [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Chen, G.-Q. Grand Challenges for Industrializing Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). Trends Biotechnol 2021, 39, 953–963. [CrossRef]

- McAdam, B.; Brennan Fournet, M.; McDonald, P.; Mojicevic, M. Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and Factors Impacting Its Chemical and Mechanical Characteristics. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2908. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.J.; Neoh, S.Z.; Sudesh, K. A Review on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) [P(3HB-Co-3HHx)] and Genetic Modifications That Affect Its Production. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; Keshavarz, T.; Roether, J.A.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Roy, I. Medium Chain Length Polyhydroxyalkanoates, Promising New Biomedical Materials for the Future. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports 2011, 72, 29–47. [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.J.; Neoh, S.Z.; Sudesh, K. A Review on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) [P(3HB-Co-3HHx)] and Genetic Modifications That Affect Its Production. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Md.K.; Novembre, L.; Greco, A.; Sannino, A. Polyhydroxyalkanoates, A Prospective Solution in the Textile Industry - A Review. Polym Degrad Stab 2024, 219, 110619. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.S.; Marinho, E.; Seabra, C.L.; Evenou, C.; Lamartine, J.; Fromy, B.; Costa, S.P.G.; Homem, N.C.; Felgueiras, H.P. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Cytocompatible Coaxial Wet-Spun Fibers Made of Polycaprolactone and Cellulose Acetate Loaded with Essential Oils for Wound Care. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 277, 134565. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.S.; Silva, A.F.G.; Pereira-Lima, S.M.M.A.; Costa, S.P.G.; Homem, N.C.; Felgueiras, H.P. Tunable Spun Fiber Constructs in Biomedicine: Influence of Processing Parameters in the Fibers’ Architecture. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 164. [CrossRef]

- Kopf, S.; Åkesson, D.; Skrifvars, M. Textile Fiber Production of Biopolymers – A Review of Spinning Techniques for Polyhydroxyalkanoates in Biomedical Applications. Polymer Reviews 2023, 63, 200–245. [CrossRef]

- Kundrat, V.; Matouskova, P.; Marova, I. Facile Preparation of Porous Microfiber from Poly-3-(R)-Hydroxybutyrate and Its Application. Materials 2019, 13, 86. [CrossRef]

- Singhi, B.; Ford, E.N.; King, M.W. The Effect of Wet Spinning Conditions on the Structure and Properties of Poly-4-hydroxybutyrate Fibers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2021, 109, 982–989. [CrossRef]

- Degeratu, C.N.; Mabilleau, G.; Aguado, E.; Mallet, R.; Chappard, D.; Cincu, C.; Stancu, I.C. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHBV) Fibers Obtained by a Wet Spinning Method: Good in Vitro Cytocompatibility but Absence of in Vivo Biocompatibility When Used as a Bone Graft. Morphologie 2019, 103, 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Alagoz, A.S.; Rodriguez-Cabello, J.C.; Hasirci, V. PHBV Wet-Spun Scaffold Coated with ELR-REDV Improves Vascularization for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomedical Materials 2018, 13, 055010. [CrossRef]

- Puppi, D.; Pirosa, A.; Morelli, A.; Chiellini, F. Design, Fabrication and Characterization of Tailored Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-(R)-3-Hydroxyexanoate] Scaffolds by Computer-Aided Wet-Spinning. Rapid Prototyp J 2018, 24, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; He, S.; Qiu, L.; Wang, M.; Gao, J.; Gao, Q. Continuous Dry–Wet Spinning of White, Stretchable, and Conductive Fibers of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate- Co -4-Hydroxybutyrate) and ATO@TiO 2 Nanoparticles for Wearable e-Textiles. J Mater Chem C Mater 2020, 8, 8362–8367. [CrossRef]

- Puppi, D.; Morelli, A.; Chiellini, F. Additive Manufacturing of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate)/Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Blend Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 49. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.S.; Silva, A.F.G.; Seabra, C.L.; Reis, S.; Silva, M.M.P.; Pereira-Lima, S.M.M.A.; Costa, S.P.G.; Homem, N.C.; Felgueiras, H.P. Sodium Alginate/Polycaprolactone Co-Axial Wet-Spun Microfibers Modified with N-Carboxymethyl Chitosan and the Peptide AAPV for Staphylococcus Aureus and Human Neutrophil Elastase Inhibition in Potential Chronic Wound Scenarios. Biomaterials Advances 2023, 151, 213488. [CrossRef]

- Puppi, D.; Chiellini, F. Wet-Spinning of Biomedical Polymers: From Single-Fibre Production to Additive Manufacturing of Three-Dimensional Scaffolds. Polym Int 2017, 66, 1690–1696. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, A.; van Walsum, G.P.; Um, B.-H. Acetic Acid Removal from Pre-Pulping Wood Extract with Recovery and Recycling of Extraction Solvents. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2019, 187, 378–395. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P. Comparing the Use of Chloroform to Petroleum Ether for Soxhlet Extraction of Fat in Meat. Anim Prod Sci 2023, 63, 1445–1449. [CrossRef]

- Puppi, D.; Pirosa, A.; Morelli, A.; Chiellini, F. Design, Fabrication and Characterization of Tailored Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-(R)-3-Hydroxyexanoate] Scaffolds by Computer-Aided Wet-Spinning. Rapid Prototyp J 2018, 24, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhou, G.; Knight, D.P.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X. Wet-Spinning of Regenerated Silk Fiber from Aqueous Silk Fibroin Solution: Discussion of Spinning Parameters. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Ma, B.; He, C.; Guo, X.; Nie, J.; Ma, G. A Review: Current Status and Emerging Developments on Natural Polymer-Based Electrospun Fibers. Macromol Rapid Commun 2022, 43. [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.; Wang, S.-Y.; Puppi, D.; Gazzarri, M.; Migone, C.; Chiellini, F.; Chen, G.-Q.; Chiellini, E. Additive Manufacturing of Poly[( R )-3-Hydroxybutyrate- Co -( R )-3-Hydroxyhexanoate] Scaffolds for Engineered Bone Development. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2017, 11, 175–186. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pan, D.; He, H. Morphology Development of Polymer Blend Fibers along Spinning Line. Fibers 2019, 7, 35. [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Shibahara, K.; Nakane, K. Melt-Electrospun Polyethylene Nanofiber Obtained from Polyethylene/Polyvinyl Butyral Blend Film. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 457. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Kazarian, S.G.; Sato, H. Simultaneous Visualization of Phase Separation and Crystallization in PHB/PLLA Blends with In Situ ATR-FTIR Spectroscopic Imaging. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 9074–9085. [CrossRef]

- Trakunjae, C.; Boondaeng, A.; Apiwatanapiwat, W.; Kosugi, A.; Arai, T.; Sudesh, K.; Vaithanomsat, P. Enhanced Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Production by Newly Isolated Rare Actinomycetes Rhodococcus Sp. Strain BSRT1-1 Using Response Surface Methodology. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1896. [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Ventosa, A. Screening and Comparative Assay of Poly-Hydroxyalkanoates Produced by Bacteria Isolated from the Gavkhooni Wetland in Iran and Evaluation of Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate Production by Halotolerant Bacterium Oceanimonas Sp. GK1. Ann Microbiol 2015, 65, 517–526. [CrossRef]

- Otaru, A.J.; Alhulaybi, Z.A.; Dubdub, I. Machine Learning Backpropagation Prediction and Analysis of the Thermal Degradation of Poly (Vinyl Alcohol). Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16, 437. [CrossRef]

- Dehouche, N.; Idres, C.; Kaci, M.; Zembouai, I.; Bruzaud, S. Effects of Various Surface Treatments on Aloe Vera Fibers Used as Reinforcement in Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx) Biocomposites. Polym Degrad Stab 2020, 175, 109131. [CrossRef]

- Berrabah, I.; Dehouche, N.; Kaci, M.; Bruzaud, S.; Deguines, C.H.; Delaite, C. Morphological, Crystallinity and Thermal Stability Characterization of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate)/Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Bionanocomposites: Effect of Filler Content. Mater Today Proc 2022, 53, 223–227. [CrossRef]

- Vanheusden, C.; Samyn, P.; Goderis, B.; Hamid, M.; Reddy, N.; Ethirajan, A.; Peeters, R.; Buntinx, M. Extrusion and Injection Molding of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx): Influence of Processing Conditions on Mechanical Properties and Microstructure. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4012. [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.; Díez-Vicente, A. Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate)/ZnO Bionanocomposites with Improved Mechanical, Barrier and Antibacterial Properties. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 15, 10950–10973. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.L.; Androsch, R. Crystallization of Poly[(R)-3-Hydroxybutyrate]. In; 2019; pp. 119–142.

- Vahabi, H.; Michely, L.; Moradkhani, G.; Akbari, V.; Cochez, M.; Vagner, C.; Renard, E.; Saeb, M.R.; Langlois, V. Thermal Stability and Flammability Behavior of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) Based Composites. Materials 2019, 12, 2239. [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Weisen, A.R.; Lee, Y.; Aplan, M.A.; Fenton, A.M.; Masucci, A.E.; Kempe, F.; Sommer, M.; Pester, C.W.; Colby, R.H.; et al. Glass Transition Temperature from the Chemical Structure of Conjugated Polymers. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 893. [CrossRef]

- Seymour, R.B.; Carraher, C.E. Mechanical Properties of Polymers. In Structure—Property Relationships in Polymers; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1984; pp. 57–72.

- Puchalski, M.; Kwolek, S.; Szparaga, G.; Chrzanowski, M.; Krucińska, I. Investigation of the Influence of PLA Molecular Structure on the Crystalline Forms (α’ and α) and Mechanical Properties of Wet Spinning Fibres. Polymers (Basel) 2017, 9, 18. [CrossRef]

- Asim, M.; Paridah, M.T.; Chandrasekar, M.; Shahroze, R.M.; Jawaid, M.; Nasir, M.; Siakeng, R. Thermal Stability of Natural Fibers and Their Polymer Composites. Iranian Polymer Journal 2020, 29, 625–648. [CrossRef]

- Singhi, B.; Ford, E.N.; King, M.W. The Effect of Wet Spinning Conditions on the Structure and Properties of Poly-4-hydroxybutyrate Fibers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2021, 109, 982–989. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, J.K. Back to Basics: The Coagulation Pathway. Blood Res 2024, 59, 35, doi:10.1007/s44313-024-00040-8.

- Mirbaha, H.; Scardi, P.; D’Incau, M.; Arbab, S.; Nourpanah, P.; Pugno, N.M. Supramolecular Structure and Mechanical Properties of Wet-Spun Polyacrylonitrile/Carbon Nanotube Composite Fibers Influenced by Stretching Forces. Front Mater 2020, 7. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Pinto, T. V.; Santos, R.M.; Correia, N. Sustainable and Naturally Derived Wet Spun Fibers: A Systematic Literature Review. Fibers 2024, 12, 75. [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.; Beuerlein, K.-U.; Luzha, G.; Drechsler, K. Effect of Extrusion Parameters on Short Fiber Alignment in Fused Filament Fabrication. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 2443. [CrossRef]

- Pecorini, G.; Braccini, S.; Simoni, S.; Corti, A.; Parrini, G.; Puppi, D. Additive Manufacturing of Wet-Spun Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate- Co -3-hydroxyvalerate)-Based Scaffolds Loaded with Hydroxyapatite. Macromol Biosci 2024, 24. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Zhang, G.; Shi, M.; Suo, Z. Fracture, Fatigue, and Friction of Polymers in Which Entanglements Greatly Outnumber Cross-Links. Science (1979) 2021, 374, 212–216. [CrossRef]

- Feijoo, P.; Samaniego-Aguilar, K.; Sánchez-Safont, E.; Torres-Giner, S.; Lagaron, J.M.; Gamez-Perez, J.; Cabedo, L. Development and Characterization of Fully Renewable and Biodegradable Polyhydroxyalkanoate Blends with Improved Thermoformability. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 2527. [CrossRef]

| Polymer | Mw (Da) | Mw/Mn |

|---|---|---|

| PHBHHx | 291000 | 4.51 |

| PHA.A.2.3.1.1 | 256423 | 3.30 |

| PHA.C.3.3.1.4 | 215659 | 2.10 |

| *Tonset (°C) | ªTMax (°C) | % Mass Loss | Tg (ºC) | Tm (ºC) | Xc (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unprocessed polymers |

PHBHHX | 263.4 | 275.7 | 2.80 | -3,44 | 103.3/119.9 | 24.9 |

| PHA.A.2.3.1.1 | 286.8 | 297.8 | 6.20 | 135.8/157.6 | 42.9 | ||

| PHA.C.3.3.1.4 | 288.2 | 300.4 | 4.60 | -24,8 | 167.2 | 19.7 | |

| Fibres | PHBHHX | 240.1 | 270.0 | 97.46 | - | 110.8/130.6 | 10.9 |

| PHA.A.2.3.1.1 | 252.3 | 272.0 | 100.71 | - | 162.6 | 25.1 | |

| PHA.C.3.3.1.4 | 267.3 | 292.0 | 98.71 | - | 171.1 | 25.0 | |

| PHA.C.3.3.1.4 / PHBHHX | 248.3 | 274.0 | 100.28 | - | 158.3 | 11.0 | |

| PHA.C.3.3.1.4 / PHA.A.2.3.1.1 | 243.4 | 272.0 | 98.06 | - | 166.6 | 46.4 | |

| PHBHHX | 240.1 | 270.0 | 97.46 | - | 110.8/130.6 | 10.9 |

| Properties | PHBHHx | PHA.A.2.3.1.1 | PHA.C.3.3.1.4 | PHA.C.3.3.1.4 / PHBHHx | PHA.C.3.3.1.4 / PHA.A.2.3.1.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Mass (dtex) | 1.65±44.9 | 3.96±64.0 | 4.12±57.9 | 1.46±37.7 | 0.96±11.40 |

| Tenacity (cN/dtex) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Elongation (%) | 18±180.4 | 0.9±43.7 | 136±90.5 | 74±98.1 | 10±144.7 |

| Linear Mass (dtex) | 1.65±44.9 | 3.96±64.0 | 4.12±57.9 | 1.46±37.7 | 0.96±11.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).