Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

01 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A resilient architecture that remains functional under conditions of noise, signal dropout, or partial modality access;

- A coordinated representation learning approach using intra-transformer cross-attention layers;

- Demonstration of strong performance across multimodal and unimodal testing scenarios;

- Elimination of dependency on pre-imputation or signal restoration for training with incomplete data.

2. Related Work

2.1. Unimodal Approaches to Sleep Staging

2.2. Multimodal Fusion in Sleep Analysis

2.3. Handling Missing and Noisy Data

2.4. Coordinated Representations in Multimodal Models

3. Methodology: MedFuseSleep Framework

3.1. Dataset and Multistage Signal Preprocessing

- Stage Consolidation: Following established precedent [12], we merge N3 and N4 into a single deep sleep class. Movement and unscored segments are discarded to maintain label integrity.

- Subject-Level Filtering: Subjects missing at least one of the five AASM-standardized sleep stages (Wake, REM, N1, N2, N3) are excluded. This guarantees representation completeness in downstream supervised training.

- Edge Trimming: Since prolonged wakefulness often occurs at recording boundaries, we symmetrically trim the edges of recordings where Wake dominates other stages:

- Resampling and Filtering: Both EEG and EOG signals are resampled to 100Hz. A FIR bandpass filter is applied: [0.3–40] Hz for EEG, [0.3–23] Hz for EOG. This removes both low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise.

- Spectral Feature Extraction: We perform Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) using a 2-second Hamming window and 1-second stride (256-point window). This yields 128-dimensional frequency features per frame.

- Windowing: The entire signal is segmented into non-overlapping 30-second epochs. Each epoch is labeled based on a majority-vote strategy among overlapping frames.

- Data Partitioning: A stratified 70/30 split is used for training and testing. From the training set, 100 subjects are reserved for validation to ensure temporal separation and subject-independence.

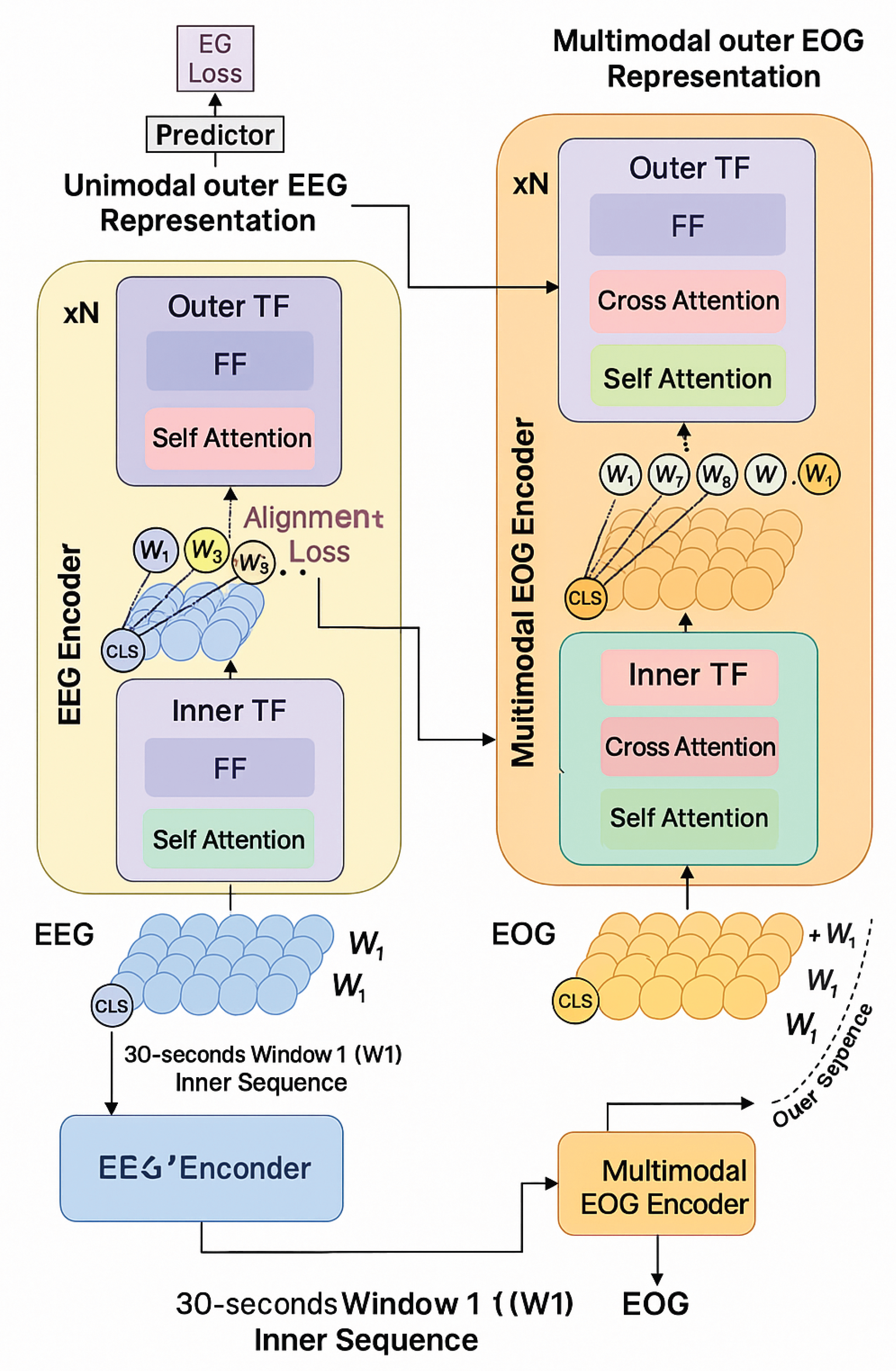

3.2. Hierarchical Temporal Transformer Design

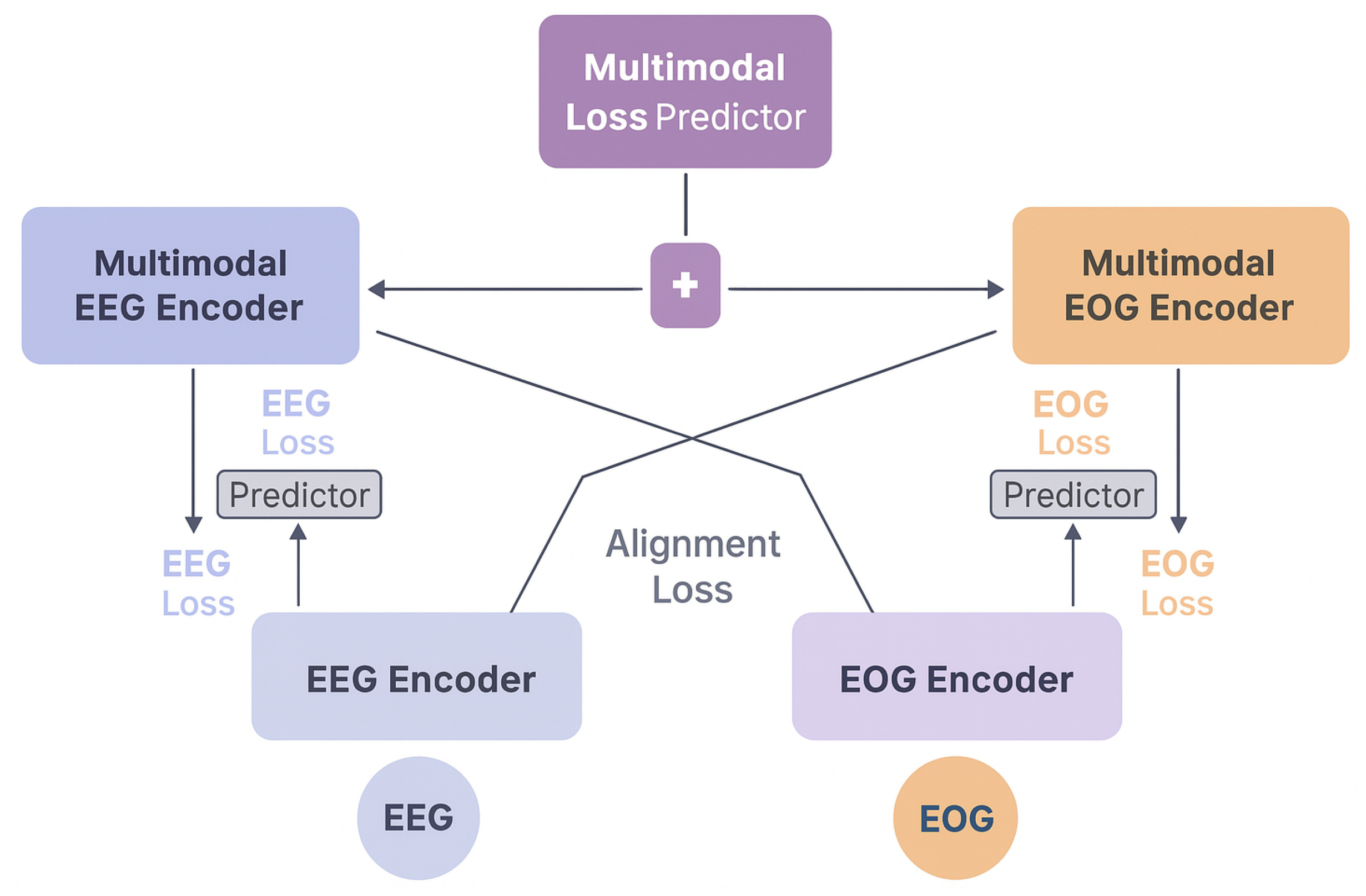

3.3. Coordinated Multimodal Interaction

3.4. Multi-Loss Training Objective

- Cross-Entropy Loss (CE): Supervised loss on the final fusion output:

- Multi-View Supervision (MS): Separate heads predict sleep stages using modality-specific outputs:

- Contrastive Alignment Loss (AL): We use InfoNCE-style alignment [54] to enforce cross-modal consistency. For batch size B, and modality pairs :where is a temperature coefficient and .

3.5. Benchmark Architectures for Comparative Evaluation

- Early Fusion: Raw modality inputs are concatenated before transformer encoding. All interactions are implicitly learned via shared attention layers. However, this structure is brittle to missing modalities and lacks interpretability.

- Mid-Late Fusion (Non-Coordinated): Separate modality encoders are trained independently. Final features are fused via summation. This lacks any intermediate cross-modal interaction and serves as a strong minimalist baseline.

4. Experiments

4.1. Training Configuration and Implementation Details

| Fusion Strategy | Variant | EEG+EOG | EEG Only | EOG Only | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc | MF1 | Acc | MF1 | Acc | MF1 | |||||

| Early Fusion | Vanilla | 89.1 ± 0.0 | 0.847 ± 0.001 | 81.7 ± 0.3 | 58.0 ± 1.4 | 0.403 ± 0.025 | 42.5 ± 1.9 | 43.6 ± 10.3 | 0.201 ± 0.111 | 29.2 ± 8.1 |

| +AL | 89.2 ± 0.0 | 0.849 ± 0.000 | 81.9 ± 0.2 | 49.7 ± 14.4 | 0.298 ± 0.179 | 39.4 ± 13.8 | 34.0 ± 4.7 | 0.094 ± 0.066 | 21.6 ± 9.1 | |

| +MS | 89.4 ± 0.1 | 0.851 ± 0.002 | 82.1 ± 0.3 | 81.7 ± 1.1 | 0.742 ± 0.015 | 65.8 ± 1.0 | 77.7 ± 1.5 | 0.686 ± 0.018 | 62.4 ± 1.2 | |

| +MS+AL | 89.5 ± 0.1 | 0.853 ± 0.002 | 82.3 ± 0.2 | 87.1 ± 1.7 | 0.820 ± 0.021 | 79.7 ± 1.6 | 83.4 ± 3.0 | 0.770 ± 0.036 | 74.0 ± 2.3 | |

| Mid-Late Fusion | Vanilla | 89.1 ± 0.1 | 0.848 ± 0.002 | 81.6 ± 0.2 | 85.4 ± 0.4 | 0.797 ± 0.006 | 78.2 ± 0.7 | 75.4 ± 2.3 | 0.639 ± 0.039 | 59.1 ± 2.5 |

| +AL | 89.2 ± 0.1 | 0.848 ± 0.002 | 81.7 ± 0.3 | 85.7 ± 0.3 | 0.800 ± 0.004 | 78.2 ± 0.6 | 74.8 ± 2.3 | 0.627 ± 0.036 | 57.2 ± 3.0 | |

| +MS | 89.2 ± 0.1 | 0.849 ± 0.002 | 81.6 ± 0.1 | 87.7 ± 0.2 | 0.828 ± 0.003 | 80.1 ± 0.2 | 84.9 ± 0.2 | 0.787 ± 0.002 | 74.4 ± 0.2 | |

| +MS+AL | 89.3 ± 0.1 | 0.851 ± 0.002 | 81.9 ± 0.1 | 88.0 ± 0.2 | 0.831 ± 0.003 | 80.4 ± 0.2 | 85.2 ± 0.1 | 0.792 ± 0.002 | 75.1 ± 0.1 | |

| MedFuseSleep (Ours) | +MS+AL | 89.5 ± 0.1 | 0.853 ± 0.002 | 82.3 ± 0.3 | 88.2 ± 0.2 | 0.834 ± 0.003 | 80.8 ± 0.4 | 85.3 ± 0.1 | 0.792 ± 0.001 | 75.3 ± 0.3 |

| XSleepNet [12] | - | 88.8 | 0.843 | 82.0 | 87.6 | 0.826 | 80.7 | - | - | - |

| SleePyCo [14] | - | - | - | - | 87.9 | 0.830 | 80.7 | - | - | - |

| SleepTransformer [13] | - | - | - | - | 87.7 | 0.828 | 80.1 | - | - | - |

4.2. Evaluation Under Standard Multimodal Settings

- Without any auxiliary loss, all three fusion models achieve competitive performance, with Mid-Late slightly outperforming others in the unimodal condition.

- The addition of MS loss consistently improves classification performance across all models, particularly in unimodal EEG or EOG testing scenarios.

- The addition of AL further enhances interaction-aware learning in the Early and MedFuseSleep models, particularly in multimodal conditions.

4.3. Robustness to Missing Modalities

- Mid-Late fusion models degrade the least under missing modality conditions, likely due to their architectural separation between modalities.

- AL alone leads to instability in the Early fusion design, while its combination with MS loss alleviates this issue.

- MedFuseSleep significantly outperforms all other fusion strategies under missing modality settings, exceeding even unimodal specialist models trained on a single modality.

| Fusion Strategy | Variant | Acc | MF1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unimodal | EEG Only | 56.1 ± 0.019 | 0.351 ± 0.029 | 43.7 ± 3.5 |

| EOG Only | 80.6 ± 2.1 | 0.722 ± 0.030 | 69.5 ± 2.0 | |

| Early Fusion | Vanilla | 77.9 ± 2.9 | 0.669 ± 0.046 | 68.6 ± 4.4 |

| +AL | 81.1 ± 1.2 | 0.730 ± 0.017 | 70.4 ± 1.1 | |

| +MS | 81.1 ± 1.0 | 0.730 ± 0.015 | 70.2 ± 1.2 | |

| +MS+AL | 83.1 ± 0.5 | 0.758 ± 0.007 | 72.2 ± 0.6 | |

| Mid-Late Fusion | Vanilla | 81.7 ± 0.3 | 0.702 ± 0.007 | 73.9 ± 0.4 |

| +AL | 82.2 ± 0.7 | 0.746 ± 0.009 | 70.2 ± 0.7 | |

| +MS | 84.2 ± 0.5 | 0.774 ± 0.008 | 73.2 ± 1.0 | |

| +MS+AL | 83.8 ± 1.1 | 0.769 ± 0.016 | 73.0 ± 1.5 | |

| MedFuseSleep (Ours) | +MS+AL | 84.0 ± 1.2 | 0.771 ± 0.017 | 73.0 ± 0.7 |

| XSleepNet [12] | - | 75.5 ± 2.6 | 0.641 ± 0.040 | 61.7 ± 4.3 |

4.4. Handling Noisy Modalities

- Unimodal EEG models experience the most significant degradation in performance.

- MedFuseSleep and Mid-Late maintain superior stability across noisy input scenarios, confirming the benefit of modular architecture and multi-loss supervision.

- Early fusion is more sensitive to modality noise without auxiliary supervision; however, adding AL and MS mitigates this.

- MedFuseSleep achieves the best accuracy and Macro-F1 in noisy conditions, closely followed by Mid-Late.

4.5. Training with Modality-Incomplete Data

- Adding unimodal patients improves performance across all predictors, particularly when their number is comparable to or slightly exceeds the multimodal subset.

- When both unimodal streams are added simultaneously, the model generalizes better even without paired inputs, suggesting robust shared latent representations.

- Extreme imbalance—where unimodal data outnumbers multimodal data substantially—leads to a decrease in complementary modality performance, due to weak supervision in cross-modal alignment.

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

- Cross-modality benefit: Incorporating multiple modalities during training—even when some are absent at inference—provides a consistent performance uplift across all evaluation settings.

- Effective representation fusion: The Coordinate-aware fusion strategy employed by MedFuseSleep captures semantically aligned yet modality-specific information, enabling the model to effectively synthesize knowledge from partially available data streams.

- Robust training strategies: Training with samples containing incomplete modalities fosters resilience in downstream predictions, even under high signal noise or dropout scenarios.

References

- A. Brzecka, J. Leszek, G. M. Ashraf, M. Ejma, M. F. Ávila-Rodriguez, N. S. Yarla, V. V. Tarasov, V. N. Chubarev, A. N. Samsonova, G. E. Barreto et al., “Sleep disorders associated with alzheimer’s disease: a perspective,” Frontiers in neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 330, 2018.

- A. K. Patel, V. Reddy, and J. F. Araujo, “Physiology, sleep stages,” in StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- R. B. Berry, R. Brooks, C. E. Gamaldo, S. M. Harding, C. Marcus, B. V. Vaughn et al., “The aasm manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events,” Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Darien, Illinois, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2012.

- E. Alickovic and A. Subasi, “Ensemble svm method for automatic sleep stage classification,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 1258–1265, 2018.

- Y. Li, K. M. Wong, and H. de Bruin, “Electroencephalogram signals classification for sleep-state decision–a riemannian geometry approach,” IET signal processing, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 288–299, 2012.

- V. Bajaj and R. B. Pachori, “Automatic classification of sleep stages based on the time-frequency image of eeg signals,” Computer methods and programs in biomedicine, vol. 112, no. 3, pp. 320–328, 2013.

- L. Fraiwan, K. Lweesy, N. Khasawneh, H. Wenz, and H. Dickhaus, “Automated sleep stage identification system based on time–frequency analysis of a single eeg channel and random forest classifier,” Computer methods and programs in biomedicine, vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 10–19, 2012.

- O. Tsinalis, P. M. Matthews, Y. Guo, and S. Zafeiriou, “Automatic sleep stage scoring with single-channel eeg using convolutional neural networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.01683, 2016.

- A. Supratak and Y. Guo, “Tinysleepnet: An efficient deep learning model for sleep stage scoring based on raw single-channel eeg,” in 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 2020, pp. 641–644.

- A. Supratak, H. Dong, C. Wu, and Y. Guo, “Deepsleepnet: A model for automatic sleep stage scoring based on raw single-channel eeg,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 25, no. 11, pp. 1998–2008, 2017.

- H. Phan, F. Andreotti, N. Cooray, O. Y. Chén, and M. De Vos, “Seqsleepnet: end-to-end hierarchical recurrent neural network for sequence-to-sequence automatic sleep staging,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 400–410, 2019.

- H. Phan, O. Y. Chén, M. C. Tran, P. Koch, A. Mertins, and M. De Vos, “Xsleepnet: Multi-view sequential model for automatic sleep staging,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2021.

- H. Phan, K. Mikkelsen, O. Y. Chén, P. Koch, A. Mertins, and M. De Vos, “Sleeptransformer: Automatic sleep staging with interpretability and uncertainty quantification,” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 2456–2467, 2022.

- S. Lee, Y. Yu, S. Back, H. Seo, and K. Lee, “Sleepyco: Automatic sleep scoring with feature pyramid and contrastive learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.09452, 2022.

- J. Pradeepkumar, M. Anandakumar, V. Kugathasan, D. Suntharalingham, S. L. Kappel, A. C. De Silva, and C. U. Edussooriya, “Towards interpretable sleep stage classification using cross-modal transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.06991, 2022.

- E. Eldele, Z. Chen, C. Liu, M. Wu, C.-K. Kwoh, X. Li, and C. Guan, “An attention-based deep learning approach for sleep stage classification with single-channel eeg,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 29, pp. 809–818, 2021.

- M. Perslev, S. Darkner, L. Kempfner, M. Nikolic, P. J. Jennum, and C. Igel, “U-sleep: resilient high-frequency sleep staging,” NPJ digital medicine, pp. 1–12, 2021.

- Z. Jia, Y. Lin, J. Wang, R. Zhou, X. Ning, Y. He, and Y. Zhao, “Graphsleepnet: Adaptive spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for sleep stage classification.” in IJCAI, 2020, pp. 1324–1330.

- D. Ramachandram and G. W. Taylor, “Deep multimodal learning: A survey on recent advances and trends,” IEEE signal processing magazine, vol. 34, no. 6, pp. 96–108, 2017.

- D. Lahat, T. Adali, and C. Jutten, “Multimodal data fusion: an overview of methods, challenges, and prospects,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 103, no. 9, pp. 1449–1477, 2015.

- S. F. Buck, “A method of estimation of missing values in multivariate data suitable for use with an electronic computer,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 302–306, 1960.

- D. B. Rubin, “Multiple imputations in sample surveys-a phenomenological bayesian approach to nonresponse,” in Proceedings of the survey research methods section of the American Statistical Association, vol. 1. American Statistical Association Alexandria, VA, USA, 1978, pp. 20–34.

- I. R. White, P. Royston, and A. M. Wood, “Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice,” Statistics in medicine, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 377–399, 2011.

- D. J. Stekhoven and P. Bühlmann, “Missforest—non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data,” Bioinformatics, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 112–118, 2012.

- B. Bischke, P. Helber, F. Koenig, D. Borth, and A. Dengel, “Overcoming missing and incomplete modalities with generative adversarial networks for building footprint segmentation,” in 2018 International Conference on Content-Based Multimedia Indexing (CBMI). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

- W. Lee, J. Lee, and Y. Kim, “Contextual imputation with missing sequence of eeg signals using generative adversarial networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 151 753–151 765, 2021.

- A. Comas, C. Zhang, Z. Feric, O. Camps, and R. Yu, “Learning disentangled representations of videos with missing data,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, pp. 3625–3635, 2020.

- W. Cao, D. Wang, J. Li, H. Zhou, L. Li, and Y. Li, “Brits: Bidirectional recurrent imputation for time series,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 31, 2018.

- J. Yoon, W. R. Zame, and M. van der Schaar, “Estimating missing data in temporal data streams using multi-directional recurrent neural networks,” IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 1477–1490, 2018.

- S. Pachal and A. Achar, “Sequence prediction under missing data : An rnn approach without imputation,” 2022.

- Y. Shen and M. Gao, “Brain tumor segmentation on mri with missing modalities,” in International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging. Springer, 2019, pp. 417–428.

- H. Nolan, R. Whelan, and R. B. Reilly, “Faster: fully automated statistical thresholding for eeg artifact rejection,” Journal of neuroscience methods, vol. 192, no. 1, pp. 152–162, 2010.

- N. Bigdely-Shamlo, T. Mullen, C. Kothe, K.-M. Su, and K. A. Robbins, “The prep pipeline: standardized preprocessing for large-scale eeg analysis,” Frontiers in neuroinformatics, vol. 9, p. 16, 2015.

- M. Jas, D. A. Engemann, Y. Bekhti, F. Raimondo, and A. Gramfort, “Autoreject: Automated artifact rejection for meg and eeg data,” NeuroImage, vol. 159, pp. 417–429, 2017.

- H. Banville, S. U. Wood, C. Aimone, D.-A. Engemann, and A. Gramfort, “Robust learning from corrupted eeg with dynamic spatial filtering,” NeuroImage, vol. 251, p. 118994, 2022.

- P. Atrey, M. Hossain, A. El Saddik, and M. Kankanhalli, “Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: A survey,” Multimedia Syst., vol. 16, pp. 345–379, 11 2010.

- L. Breiman, “Bagging predictors,” Machine learning, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 123–140, 1996.

- C. Chatzichristos, S. Van Eyndhoven, E. Kofidis, and S. Van Huffel, “Coupled tensor decompositions for data fusion,” in Tensors for data processing. Elsevier, 2022, pp. 341–370.

- T. Baltrušaitis, C. Ahuja, and L.-P. Morency, “Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy,” IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 423–443, 2018.

- C. Hazirbas, L. Ma, C. Domokos, and D. Cremers, “Fusenet: Incorporating depth into semantic segmentation via fusion-based cnn architecture,” in Asian conference on computer vision. Springer, 2016, pp. 213–228.

- Y. Wang, W. Huang, F. Sun, T. Xu, Y. Rong, and J. Huang, “Deep multimodal fusion by channel exchanging,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, pp. 4835–4845, 2020.

- A. Nagrani, S. Yang, A. Arnab, A. Jansen, C. Schmid, and C. Sun, “Attention bottlenecks for multimodal fusion,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 34, pp. 14 200–14 213, 2021.

- J. Lu, J. Yang, D. Batra, and D. Parikh, “Hierarchical question-image co-attention for visual question answering,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 29, 2016.

- Y.-H. H. Tsai, S. Bai, P. P. Liang, J. Z. Kolter, L.-P. Morency, and R. Salakhutdinov, “Multimodal transformer for unaligned multimodal language sequences,” in Proceedings of the conference. Association for Computational Linguistics. Meeting, vol. 2019. NIH Public Access, 2019, p. 6558.

- J. Li, D. Li, C. Xiong, and S. Hoi, “Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.12086, 2022.

- J. Li, R. Selvaraju, A. Gotmare, S. Joty, C. Xiong, and S. C. H. Hoi, “Align before fuse: Vision and language representation learning with momentum distillation,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 34, pp. 9694–9705, 2021.

- J. Yu, Z. Wang, V. Vasudevan, L. Yeung, M. Seyedhosseini, and Y. Wu, “Coca: Contrastive captioners are image-text foundation models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01917, 2022.

- A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, . Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin, “Attention is all you need,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 30, 2017.

- J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, “Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

- A. Radford, J. W. Kim, T. Xu, G. Brockman, C. McLeavey, and I. Sutskever, “Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.04356, 2022.

- S. F. Quan, B. V. Howard, C. Iber, J. P. Kiley, F. J. Nieto, G. T. O’Connor, D. M. Rapoport, S. Redline, J. Robbins, J. M. Samet et al., “The sleep heart health study: design, rationale, and methods,” Sleep, pp. 1077–1085, 1997.

- G.-Q. Zhang, L. Cui, R. Mueller, S. Tao, M. Kim, M. Rueschman, S. Mariani, D. Mobley, and S. Redline, “The national sleep research resource: towards a sleep data commons,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, pp. 1351–1358, 2018.

- A. Rechtschaffen, “A manual for standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages in human subjects,” Brain information service, 1968.

- A. Radford, J. W. Kim, C. Hallacy, A. Ramesh, G. Goh, S. Agarwal, G. Sastry, A. Askell, P. Mishkin, J. Clark et al., “Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision,” in International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- J. L. Ba, J. R. Kiros, and G. E. Hinton, “Layer normalization,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.06450, 2016.

- V. Nair and G. E. Hinton, “Rectified linear units improve restricted boltzmann machines,” in Proceedings of the 27th international conference on machine learning (ICML-10), 2010, pp. 807–814.

- H. Phan, K. P. Lorenzen, E. Heremans, O. Y. Chén, M. C. Tran, P. Koch, A. Mertins, M. Baumert, K. Mikkelsen, and M. De Vos, “L-seqsleepnet: Whole-cycle long sequence modelling for automatic sleep staging,” 2023.

- P. Shaw, J. Uszkoreit, and A. Vaswani, “Self-attention with relative position representations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.02155, 2018.

- Y. Huang, J. Lin, C. Zhou, H. Yang, and L. Huang, “Modality competition: What makes joint training of multi-modal network fail in deep learning?(provably),” arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.12221, 2022.

- M. Ma, J. Ren, L. Zhao, D. Testuggine, and X. Peng, “Are multimodal transformers robust to missing modality?” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 18 177–18 186.

- A. Paszke, S. Gross, S. Chintala, G. Chanan, E. Yang, Z. DeVito, Z. Lin, A. Desmaison, L. Antiga, and A. Lerer, “Automatic differentiation in pytorch,” in NIPS-W, 2017.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

- I. Loshchilov and F. Hutter, “Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.03983, 2016.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- Endri Kacupaj, Kuldeep Singh, Maria Maleshkova, and Jens Lehmann. 2022. An Answer Verbalization Dataset for Conversational Question Answerings over Knowledge Graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.06734 (2022).

- Magdalena Kaiser, Rishiraj Saha Roy, and Gerhard Weikum. 2021. Reinforcement Learning from Reformulations In Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 459–469.

- Yunshi Lan, Gaole He, Jinhao Jiang, Jing Jiang, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2021. A Survey on Complex Knowledge Base Question Answering: Methods, Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 4483–4491. Survey Track.

- Yunshi Lan and Jing Jiang. 2021. Modeling transitions of focal entities for conversational knowledge base question answering. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers).

- Mike Lewis, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Veselin Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2020. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7871–7880.

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. 2019. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Pierre Marion, Paweł Krzysztof Nowak, and Francesco Piccinno. 2021. Structured Context and High-Coverage Grammar for Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (2021).

- Pradeep K. Atrey, M. Anwar Hossain, Abdulmotaleb El Saddik, and Mohan S. Kankanhalli. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia Systems, 16(6):345–379, April 2010. ISSN 0942-4962. [CrossRef]

- Meishan Zhang, Hao Fei, Bin Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yixin Cao, Fei Li, and Min Zhang. Recognizing everything from all modalities at once: Grounded multimodal universal information extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, and Tat-Seng Chua. Universal scene graph generation. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Jingkang Yang, Xiangtai Li, Juncheng Li, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. Learning 4d panoptic scene graph generation from rich 2d visual scene. Proceedings of the CVPR, 2025.

- Yaoting Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yuecheng Zhang, Shuicheng Yan, Ziwei Liu, Jiebo Luo, and Hao Fei. Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.12605, 2025.

- Hao Fei, Yuan Zhou, Juncheng Li, Xiangtai Li, Qingshan Xu, Bobo Li, Shengqiong Wu, Yaoting Wang, Junbao Zhou, Jiahao Meng, Qingyu Shi, Zhiyuan Zhou, Liangtao Shi, Minghe Gao, Daoan Zhang, Zhiqi Ge, Weiming Wu, Siliang Tang, Kaihang Pan, Yaobo Ye, Haobo Yuan, Tao Zhang, Tianjie Ju, Zixiang Meng, Shilin Xu, Liyu Jia, Wentao Hu, Meng Luo, Jiebo Luo, Tat-Seng Chua, Shuicheng Yan, and Hanwang Zhang. On path to multimodal generalist: General-level and general-bench. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2025.

- Jian Li, Weiheng Lu, Hao Fei, Meng Luo, Ming Dai, Min Xia, Yizhang Jin, Zhenye Gan, Ding Qi, Chaoyou Fu, et al. A survey on benchmarks of multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632, 2024.

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553):436–444, may 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608.

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.1090, 2014.

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. In The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pp. 1–6. IEEE, aug 2013. ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3. URL http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=6706748. [CrossRef]

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014.

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024a.

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, “Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions,” TPAMI, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 664–676, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2151–2161, 2020a.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 11513–11521, 2022.

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4232–4241, 2022.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 7692–7699, 2020b.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9871–9881, 2022.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion, 100:101919, 2023.

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09541, 2018.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11719, 2023a.

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357, 2024.

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, pages 15460–15475, 2022a.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics, 37(1):9–27, 2011.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 22(3), 2021.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2593–2608, 2023b.

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05250, 2016.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021a.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021b.

- K. Papineni, S. K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11255, 2023a.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR, abs/2309.05519, 2023c.

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024b.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv, 2019.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024c.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022b.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023b.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024,, 2024d.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 11:1–10, 01 2021.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05127, 2024.

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022c.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy, 11(12):2411, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management, 57(6):102311, 2020c.

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022.

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: a conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(4):1–22, 2018b.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023d.

- P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 41(2):50:1–50:32, 2023c.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023a.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023e.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 34(9):5544–5556, 2023d.

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03044, 2(3):5, 2015.

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 23(8):1177–1193, 2012.

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).