Introduction

Temporal superposition refers to a condition where a physical system exists at several points in time instead of staying fixed in one moment. This idea mirrors the way particles in quantum mechanics can stay in multiple states until someone observes them. Belenchia et al. (2020) supported this view through a model that used detectors controlled by quantum states across separate time branches. They presented time as a wave with interference patterns and shifting amplitudes. Moreover, Rubino et al. (2021) confirmed this through experiments that combined forward and reverse flows of time using a qubit. This theory separates itself from classical physics, which treats time as a straight and one-way movement. The model treats time as something observable that reacts to measurement instead of serving as a neutral setting. This view opens the possibility of effects that stretch across different times, where one act of observation gathers many potential moments into a single present. Therefore, the theory sees time not as a passive container of events but as a part of the system that shifts along with quantum states and wavefunctions.

Theory: Time as a Wave

Temporal superposition refers to a condition where a system exists across several time points instead of occupying only one. In fact, this mirrors how particles in quantum mechanics exist in a superposition of positions or states. Belenchia et al. (2020) described this through a structure where detectors act across separate time branches controlled by a quantum state. Moreover, a system under temporal superposition permits interactions between moments that classical physics treats as unrelated. As a result, time behaves like a wave with measurable amplitudes, states, and outcomes. This behavior corresponds to the wavefunction Ψ used in standard quantum theory. Rubino et al. (2021) supported this idea with experimental work showing the coexistence of forward and reverse temporal dynamics in thermodynamic systems, controlled by a qubit. Temporal superposition makes it possible to extract information about field correlations that would otherwise require multiple observations across distinct timelines (Memon et al., 2024).

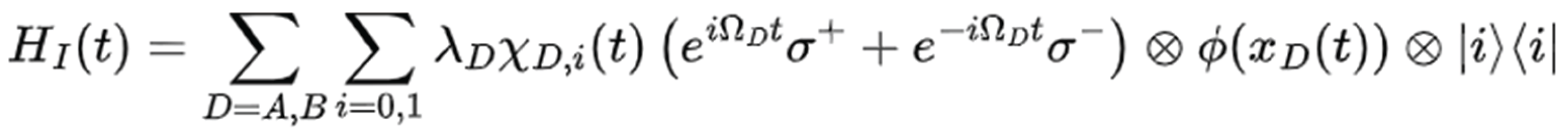

To describe time as a wave, the paper adopts a wavefunction-style model based on prior quantum field formulations. The Hamiltonian of the system, as modeled by Belenchia et al. (2020), integrates spatial smearing, energy gaps, and control qubit encoding as follows:

Each symbol corresponds to a physically grounded parameter:

Each symbol corresponds to a physically grounded parameter: is the energy gap of detector , is the coupling constant, represents the time control function, and is the scalar field at the detector’s location. The operators represent quantum transitions between energy states. What this equation suggests is that time behaves as a dynamic variable influenced by quantum states, not as a fixed, external parameter. The commutator structure from this model allows interference terms to show nonlocal correlations across time (Khrennikov, 2019). This idea supports the view that time, just like position, collapses to a single outcome only when something observes it.

Furthermore, this model works through a temporal Hilbert space that captures the quantum structure of time itself. In this space, each possible time state holds a distinct amplitude. Also, the full temporal wavefunction becomes a weighted sum across those basis states:

To represent the moment of temporal collapse, one applies a projection operator

, which selects a single time outcome:

This formalism shows how a single “now” forms from many possible moments through quantum selection. It does not require changes to operators based on space or to the usual structure of spacetime. Aharonov and Bohm (1961) explored similar views through time operator models. Muga et al. (2008) later extended these ideas in work on open quantum systems and theories of measurement.

Comparison with Classic Experiments

Classic quantum experiments, especially Wheeler’s delayed-choice setup, suggest that future measurements can appear to affect the past. In these studies, a photon’s path remains undefined until a detector is added or removed, even though the photon has already passed the slits. Wheeler explained this as a reversal in the order of explanation, where later choices define earlier histories (Ellerman, 2015; Waaijer & Van Neerven, 2024). However, many physicists now agree that this does not mean real retrocausality takes place. The state of the system remains in superposition until a measurement occurs. Therefore, nothing in these experiments requires information to travel backward in time. The confusion arises from assuming a particle had a fixed path before observation, which standard quantum mechanics never claims. Both the standard delayed-choice and its modified forms yield the same results because the order of operations does not change the final quantum state (Waaijer & Van Neerven, 2024).

This paper proposes a deeper shift in perspective. Instead of focusing on the particle, it treats time itself as part of the superposed system. In this model, interference does not occur between physical paths alone but between possible time states. To illustrate, just as two overlapping sound waves can combine or cancel out depending on their timing, different temporal states may produce interference when coherently superposed. As a result, the act of observation collapses not only spatial probabilities but also temporal ones. The observer does not simply learn where the particle is; the observer also determines when the particle becomes real. This idea extends beyond classical delayed-choice logic because it suggests that time behaves like a wave and carries its own uncertainty until measured. Therefore, the collapse of the “now” becomes a physical event, not just a mental one.

What Makes This Theory New

This theory includes time as an observable rather than a fixed background. Instead of assuming that time flows independently of quantum states, it suggests that time behaves as a measurable quantity that collapses into a single value during observation. The process called “quantum selection” refers to the resolution of many possible time outcomes into one experienced moment; this follows a pattern similar to how a particle’s position collapses into one definite state in space. This idea does not aim to reject previous models. Instead, introduces a shift in how time may be involved directly in the measurement process. The claim does not rely on new particles or forces but on reinterpreting the structure of quantum events through the lens of time superposition. Therefore, this model offers a conceptual revision without requiring an empirical contradiction of established quantum results.

Thought Experiments

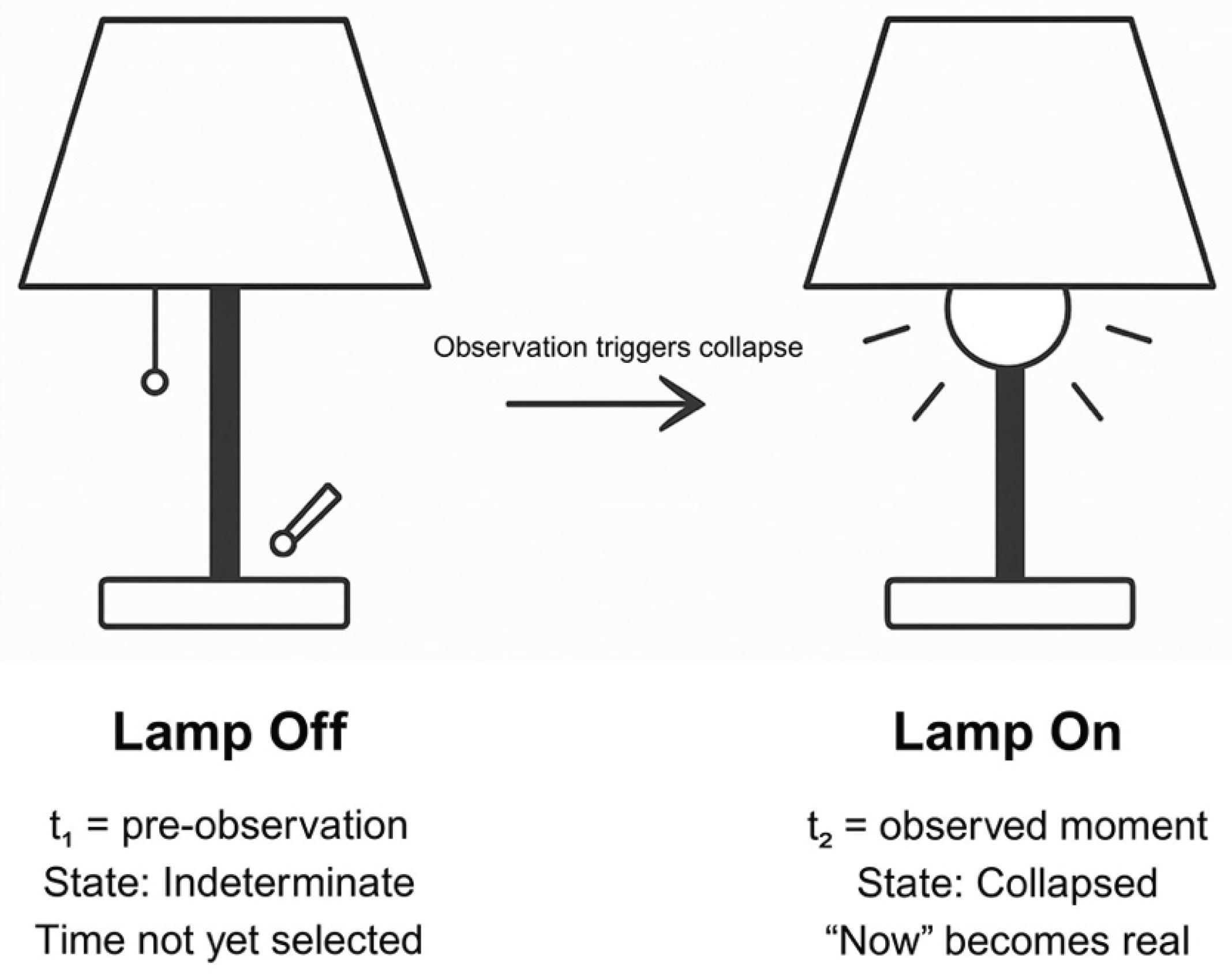

A simple thought experiment involving a light bulb can help clarify how this paper treats time as observer-dependent. As shown in the figure, imagine a lamp beside your bed. You flip the switch expecting the light to turn on. At that moment, let t₁ represent the system before observation—before the bulb either lights up or remains dark. You do not know if the bulb works, if the lamp is plugged in, or if any part of the circuit will respond. That uncertainty holds all possibilities in superposition. Then, at t₂, the bulb either glows or stays unlit. This marks the point where observation collapses the uncertainty and selects one result. The change is not gradual. The switch leads to an immediate, definite state. Likewise, in quantum theory, no moment in time becomes real until it is measured. According to Pylkkänen (2016), the wave function does not describe a real object but only probabilities that define what could happen. In this theory, the same idea applies to time. The observer does not merely witness an existing timeline but draws one possibility into presence. The state at t₁ includes all possible time outcomes. The act of measurement chooses just one, and that becomes the experienced “now.” All other options vanish without becoming real. Furthermore, this idea matches Bohm’s model of active information, which says a quantum field’s form—not its force—guides how events unfold. Like a radar that informs a ship’s direction without touching it, the observer selects a time without forcing anything. Pylkkänen (2016) described this as a guiding form, not a mechanical push. The LibreTexts (2016) light bulb analogy reinforces this: t₁ is the moment the switch is flipped, when nothing has yet appeared. The bulb may light or not. At t₂, the observer sees the result and gives it meaning. Observation becomes the event that triggers existence. Time does not roll forward on its own. Instead, each moment of attention causes one real version of time to appear. This model suggests that without observation, time remains dark and undecided. Each flip of the switch generates a single outcome. Without it, nothing unfolds. This means time is not a line already drawn but a field full of unrealized paths. The observer does not walk through a prewritten script. The observer activates the script one line at a time (Goldstein, 2024). This theory claims that the present moment is not an automatic continuation of the past. Rather, it is the result of a selection. Like a bulb in a room, the moment lights up only when someone enters and looks. This simple difference—between what exists before the look and what appears because of it—defines the central claim. Time exists only when it becomes the “now.”

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the observer-dependent collapse of temporal superposition. At t₁, the system holds multiple possible time states. Observation collapses this superposition into a single outcome at t₂, similar to a light bulb that activates only when observed.

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the observer-dependent collapse of temporal superposition. At t₁, the system holds multiple possible time states. Observation collapses this superposition into a single outcome at t₂, similar to a light bulb that activates only when observed.

This idea connects with the famous question, “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” The point of this thought experiment is not about sound but about existence. Without observation, the event has no confirmed outcome. Likewise, in this theory, time does not unfold into a real moment unless an observer resolves it. The tree’s sound and the present moment both depend on the act of becoming known.

Proposed Experiment

If time behaves like a wave, then time should allow for interference patterns in a way similar to spatial wave interference. This paper proposes a hypothetical test based on this assumption. In theory, if time holds a superposition of possible moments, then experimental setups should show interference patterns across those moments. One method to explore this involves time-bin qubits, which encode quantum information in the arrival time of single photons. Qubits cause visible interference effects when early and late time bins meet under strict phase control. Researchers apply unbalanced Mach–Zehnder interferometers to split the photon paths and later join them again. In this setup, time separation replaces physical distance as the main variable. Because of this structure, even small changes in phase between the temporal bins cause either constructive or destructive interference. This behavior points to the idea that time acts as a measurable wave property rather than as a passive background for events (Afek et al., 2023).

Moreover, experiments with optical clocks now support this idea through precise measurement of time-related behaviors. These clocks reach accuracy levels as fine as 10⁻¹⁸, which allows researchers to observe extremely short time intervals. The coherence time in these systems often lasts several milliseconds, which makes it possible to capture subtle interference patterns over time. In such experiments, two events that occur at different moments can interact just like two beams of light that meet in space. Therefore, when researchers detect patterns of constructive and destructive interference between separate photon emissions, they gain strong reason to believe that time behaves like a wave. This approach already informs progress in time-based quantum communication and relies on technologies that exist and work today (Afek et al., 2023).

If detectors resolve photon arrival times with high precision, interference visibility should follow a cosine pattern. The formula V(δt) = cos(ωδt) expresses how the visibility drops as detectors gain enough resolution to distinguish time bins. This predicts a measurable threshold where time collapse removes coherence. For instance, modern time-bin photon detectors now resolve arrival intervals at picosecond scales, which aligns with the δt values where this formula predicts a visibility drop due to temporal decoherence. Because of this, existing optical technologies already fall within the predicted resolution window where the effects of temporal collapse may be directly observed

Furthermore, models based on Earth-observing instruments, such as CERES, add an indirect form of validation. Simulations using plane electromagnetic waves have shown that when sources are random in phase and spatial distribution, interference disappears. However, when sources share direction and phase, the interference term remains significant (Kato et al., 2020). These conditions suggest that even in large-scale, noisy environments, coherence in time can still appear. Therefore, if a controlled system isolates coherent events across short time intervals—like in quantum optical setups—the emergence of interference patterns may become testable. This experiment does not aim to measure time directly. Instead, it observes the consequences of how time behaves when photons travel through systems designed to treat time as a dynamic quantity. Such findings could support the theory that time emerges through wave-based mechanisms, not through static or absolute progression.

Compatibility with Einstein’s Framework

This theory does not contradict Einstein’s framework of relativity. It agrees with the flexibility of spacetime coordinates and does not change the geometry described by Lorentz invariance or general relativity. Instead, it adds a new layer. It treats the present not as a slice of a block universe but as a quantum selection from many possible moments. This collapse does not affect spacetime structure itself. It simply suggests that what becomes real may depend on resolution, not on a timeline drawn in advance. The theory stays within the bounds of accepted physics while extending its interpretation.

Arrow of Time

Entropy once stood as the main reason scientists believed time moved in one direction. The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that entropy rises in an isolated system. That led many to believe the universe flows toward disorder, and time must move forward as a result. Clausius first linked entropy to time, and Eddington supported this with his “arrow of time” idea. He claimed the universe moves toward more randomness, so time must flow toward the future (Ben-Naim, 2020; Price, 2008). However, several scholars now dispute this idea. Ben-Naim (2020) argues that entropy does not depend on time at all. He says entropy is a state function, which means it describes a condition but not how that condition changes. For him, the universe’s entropy cannot “increase with time” because time does not affect it. He even calls the “entropy equals time’s arrow” idea misleading. He rejects the claim that thermodynamics alone explains why time moves forward. Price (2008) also says that the laws of physics remain time-symmetric. If so, then time must appear to move forward due to something else, not because entropy pushes it.

The theory in this paper suggests that time’s arrow may come from how quantum systems collapse into single moments. In objective collapse models, each observation causes the wave function to reduce to one outcome. This collapse does not stretch across time. It happens in one instant, which then becomes the present. The flow of time, then, may emerge from many such collapses. Each collapse selects one “now,” and each new “now” replaces the previous one (Price, 2008). Time seems to move forward because we live in a world that updates itself one collapse at a time. Quantum Darwinism adds a helpful layer to this idea. It says that some results survive over others because the environment copies those results the most. These stable outcomes look like classical reality. That process also builds the sense of time moving from one event to the next. Therefore, instead of time flowing like a river, time may click forward like a slideshow. Each collapse lights up a new slide, and entropy does not push this forward. The wave function’s behavior, guided by observation, may do it instead.

Broader Implications

This theory opens connections to several fields beyond physics. It provides a new way to think about consciousness and metaphysics. Instead of treating time as a neutral background, this theory treats time as something selected or resolved through interaction. Therefore, consciousness may not only observe time but also take part in its resolution. For example, a mind may not passively see a moment. It may help create the moment through attention. This idea overlaps with some interpretations of consciousness that link awareness to quantum measurement (Pylkkänen, 2016). Moreover, metaphysical questions about what exists and when it exists gain a new framework. Time does not bring things into reality. Selection brings them forward, and this means reality builds itself from choices, not from a single path. Not only that, but reality across time may shift based on when and how a system gets resolved. Some interpretations extend this idea by suggesting a universal observer—often called “God”—who stands outside time and observes all potential outcomes (Youvan, 2025). In this view, even if no human mind collapses time, the act of divine awareness may still resolve it. This theory changes how we define existence. It does not say everything exists all at once. Instead, it claims that only one outcome becomes real after selection. Because of this, the idea redefines reality as something that unfolds from measurements, not something already fixed across time.

Addressing Objectives

Some critics may argue that the theory lacks a defined equation of time or rests on speculative reasoning without empirical grounding. However, the paper does not claim to provide measurable predictions at this stage. Instead, it presents a conceptual model that treats time as a selectable variable within quantum systems. It invites thought experiments and theoretical simulations rather than experimental validation at this point. For this reason, one must read it as a foundation for new approaches, not as a replacement for current quantum mechanics. Moreover, the theory frames time as part of the resolution process, which allows it to intersect with existing quantum interpretations such as Bohmian mechanics and Quantum Darwinism (Pylkkänen, 2016; Price, 2008). Future work can build on this idea through quantum simulations. For instance, one can test whether temporally entangled systems under time-as-wave assumptions yield distinct outcomes when subjected to phase-controlled measurements (Thomsen, 2021). Another direction may involve designing coherent state models where time-bin qubits resolve through variable delay gates, much like spatial wave interference (Afek et al., 2023). Not only that, but optical clock experiments can examine whether minute shifts in resolution timing lead to observable interference. These proposals do not aim to confirm the theory as fact. They aim to show that time may not operate as a passive container but as an active property that emerges through resolution.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper proposes that time does not unfold in a continuous stream but collapses into the present through observation, just like other quantum variables. Moreover, it suggests that time exists as a superposition of possible moments, which only become real when someone—or something—observes them. This model treats “now” as a result of quantum selection, not a fixed point in a flowing sequence. Furthermore, the theory draws from established quantum mechanics and aligns with experimental designs such as time-bin qubit interference and precise optical clock resolution. Also, it stays consistent with Einstein’s relativity while offering a new way to think about the arrow of time, consciousness, and reality itself. Because of this, the theory invites new experiments and interpretations that connect physics, metaphysics, and the act of observation into one evolving picture.

Multi-Dimensional Time (Future Work)

This paper has treated time as a single dimension that collapses into the present through observation. However, future research may explore the idea that time includes more than one dimension, just as space does. One axis may serve as a classical timeline, while another may follow quantum behavior, subject to uncertainty and collapse. For this reason, a two-dimensional model of time may resolve current limits on defining a time operator in quantum systems. Moreover, such a model could explain how the present becomes real without contradicting relativity. The structure may also connect with theories in string physics or two-time models, where different time directions serve different functions. This added layer could allow new predictions about how time appears, disappears, or behaves across scales. Because of this, the theory may one day link quantum timing and classical flow within one unified model.

References

- Afek, I., Moses, N., Glick, L., & Eisenberg, H. S. (2023). Temporal interferometry and quantum coherence in time-bin qubit systems. npj Quantum Information, 9, 78. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M. (2016). Retrocausality, Wheeler’s delayed choice, and simulation theory: Reinterpreted via the participatory universe, ‘it from bit’, time travel and the Everett/Wheeler hypothesis. AET RaDAL. [CrossRef]

- Belenchia, A., Castro-Ruiz, E., Budroni, C., Zych, M., Brukner, Č., Mann, R. B., & Henderson, L. J. (2020). Quantum temporal superposition: The case of QFT. Physical Review Letters, 125(13), Article 131602. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, A. (2020). Entropy and Time. Entropy, 22(4), 430. [CrossRef]

- Biology LibreTexts. (2016, May 27). 1.2: The scientific process. In Principles of Biology. OpenStax CNX. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Principles_of_Biology/01%3A_Chapter_1/01%3A_The_Process_of_Science/1.02%3A_The_Scientific_Process.

- Ellerman, D. (2015). Why delayed choice experiments do not imply retrocausality. Quantum Studies: Mathematics and Foundations, 2(2), 183–199. [CrossRef]

- Gambini, R., & Pullin, J. (2023). Quantization of spherically symmetric loop quantum gravity coupled to a scalar field and a clock: The asymptotic limit. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.05766.

- Goldstein, S. (2024). Bohmian mechanics. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2024 Edition). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2024/entries/qm-bohm/.

- Kato, S., Loeb, N. G., Rutan, D. A., & Rose, F. G. (2020). Effects of electromagnetic wave interference on observations of the Earth radiation budget. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer, 253, 107157. [CrossRef]

- Khrennikov, A. (2019). Get rid of nonlocality from quantum physics. Entropy, 21(8), 806. [CrossRef]

- Memon, Q. A., Al Ahmad, M., & Pecht, M. (2024). Quantum computing: Navigating the future of computation, challenges, and technological breakthroughs. Quantum Reports, 6(4), 627–663. [CrossRef]

- Price, H. (2008). The Flow of Time: Arrow or Carousel? Retrieved from https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/8894/1/Arrow_Time_v2.pdf.

- Pylkkänen, P. (2016). Quantum theory, active information and the mind-matter problem. In E. Dzhafarov, S. Jordan, R. Zhang, & V. Cervantes (Eds.), Contextuality from quantum physics to psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 325–334). World Scientific. [CrossRef]

- Rubino, G., Manzano, G., & Brukner, Č. (2021). Quantum superposition of thermodynamic evolutions with opposing time’s arrows. Communications Physics, 4, Article 251. [CrossRef]

- Sacha, K., & Zakrzewski, J. (2018). Time crystals: A review. Reports on Progress in Physics, 81(1), 016401. [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, K. (2021). Timelessness strictly inside the quantum realm. Entropy, 23(6), 772. [CrossRef]

- Waaijer, M., & Van Neerven, J. (2024). Delayed choice experiments: An analysis in forward time. Quantum Studies: Mathematics and Foundations, 11, 391–408. [CrossRef]

- Youvan, D. C. (2025, January). The universal meta-limitation: Exploring the observer problem across quantum mechanics, Gödelian systems, and emergent phenomena [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).