1. Introduction

Natural products and their bioactive properties have demonstrated improved interest across pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries. This trend reflects growing societal awareness of biodiversity conservation, sustainable economic, and cultural practices. Within the skincare sector, the valorization of industrial byproducts has emerged as a key strategy, fostering innovation while aligning with circular economy principles [

1,

2].

Blackberry byproducts (

Rubus spp. cultivar Xavante) – including seeds, peels, and pulp – are particularly remarkable due to their high concentrations of polyunsaturated fatty acids, tocopherols, tocotrienols, phytosterols, and carotenoids, as reported in recent literature [

3,

4,

5]. These bioactive compounds demonstrate multifunctional properties, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging effects, along with hydration enhancement and skin barrier reinforcement [

1,

4,

6,

7]. Such attributes position them as highly promising candidates for advanced cosmetic formulations.

The synergistic interaction of these bioactive compounds enhances their efficacy in cosmetic formulations, providing multi-target cellular protection across skin layers through complementary mechanisms of action. Therefore, blackberry byproducts have considerable potential as valuable ingredients in cosmetic products, providing multifaceted benefits for skin health and appearance [

2,

5,

6,

8]. The valorization of blackberry (

Rubus spp.) by-products represents a significant industrial opportunity, simultaneously enhancing commercial yield through full use of raw materials [

4,

5,

8] while establishing sustainable production systems that minimize agro-industrial waste.

The choice of processing methods for these oils is crucial to obtaining high-quality oil [

5,

8]. An innovative method that has proven effective is supercritical CO

2 (scCO

2) extraction [

4,

5,

8]. This extraction method enables low-temperature recovery of high-quality oils while operating under oxygen- and light-free conditions for preserving thermo- and photo-sensitive bioactive compounds. Furthermore, it demonstrates superior selectivity to fatty acids and eliminates the need for hazardous organic solvents compared to conventional extraction techniques [

8].

Despite their demonstrated bioactivity, the practical application of plant-derived oils faces substantial technological limitations due to intrinsic physicochemical properties including volatility, poor aqueous solubility, and susceptibility to oxidative and thermal degradation [

7]. Nanotechnology-based delivery systems, particularly biodegradable polymeric nanocapsules, have emerged as an innovative solution to these challenges. These nanocarriers successfully encapsulate bioactive compounds within protective nanostructures, shielding them from environmental stressors while enabling controlled release [

7,

9].

Polymeric nanocapsules are nanoscale delivery systems (100-500 nm) characterized by an oil-filled core surrounded by a stabilizing polymeric shell. This unique architecture offers several advantages: (1) it maximizes active ingredient loading while minimizing polymer requirements, (2) the polymeric barrier effectively isolates encapsulated compounds from surrounding tissues, and (3) prevents premature degradation or uncontrolled release of bioactive components. [

9,

10,

11]. These materials are useful tools for improving the delivery of bioactives to the skin, allowing controlled release of the active ingredients over prolonged periods and under specific conditions [

12,

13].

Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) is a polymer extensively used in the development of such systems. It has suitable properties as a biodegradable, biocompatible, low-cost, non-toxic, and compatible biomaterial. Therefore, it can improve the biological activity of blackberry byproducts on the skin [

2,

14,

15]. However, no previous paper was devoted to preparing PCL nanocapsules containing blackberry seed oil (BSO) for cosmetic purposes to increase collagen production.

Considering the reported bioactive and antioxidant properties of blackberry (Rubus spp.) byproducts and their economic/sustainability benefits, this study aimed to develop and characterize poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanocapsules encapsulating supercritical CO₂-extracted blackberry seed oil in order to enhance the stability and the skin delivery. This innovative approach seeks to enhance the BSO characteristics and potentiate its biological action on the skin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Blackberry fruits (

Rubus spp. cultivar Xavante) were collected in the field station of the State University of the Central-West of Paraná at the CEDETEG campus (Guarapuava, Paraná State, Brazil). All procedures for seed separation, drying, milling, and subsequent characterization of the milled material were performed according to the method previously detailed [

5].

2.2. Oil Extraction

The blackberry seed oil (BSO) was extracted via supercritical CO₂ (scCO

2) extraction [

16] using a home-made laboratory-scale supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) unit consisted of a 62.4 cm

3 extraction vessel, a high-pressure syringe pump for pressure control, and ultra-thermostatic bath to maintain temperature. The extraction vessel was carried with 30 g of milled blackberry seeds in each extraction. The extraction conditions were: 70°C, 25 MPa, 60 min static extraction, and a CO

2 flow of 2.0 mL.min

-1 (2.00 g.min

-1) and 180 min dynamic extraction. These conditions correspond to the highest yield extraction obtained from a previous publication [

5]. The oil extract with scCO

2 (BSO) was collected at 18 °C and 1 atm.

2.3. UHPLC–ESI–Q-TOF–MS Analysis

Three microliters of the blackberry seed oil samples were directly injected into an Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatograph (UHPLC, Shimadzu, Nexera X2) system, coupled to a Quadruple-Time of Flight mass spectrometer (Q-TOF-MS, Bruker, Impact II) system, equipped with Shim-pack XR-ODS III column (2.0 × 75 mm, 1.6 μm) Shimadzu. The Q-TOF-MS system was equipped with an Electrospray ionization (ESI) source and a Micro Channel Plate (MCP) detector. Mobile phases A and B were used: A (ultrapure water) and B (acetonitrile). The gradient elution was as follows: 0.0-2.0 min 5% B; 2.0-3.0 min 30% B; 3.0-10 min 95% B, 10.0-14.0 min 95% B; 14.0–15.0 min 5% B. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL.min-1 and a column oven temperature at 40°C. The operating parameters of ESI were capillary voltage of 4500 V, argon (Ar) at 200°C, pressure of 4 bar, and flow rate of 8 L.min-1 in negative mode. The MS system settings were m/z = 50–1950 (mass range). Calibration of the Q-TOF-MS system was performed with a sodium formate solution (10 mmol.L-1).

2.4. Preparation of Blackberry Seed Oil-Loaded Nanocapsules (NCBSO)

Suspensions of poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanocapsules loaded with blackberry seed oil (NCBSO) were prepared using the interfacial deposition method of preformed polymer, as described by Fessi et al. (1989) [

17]. Briefly, PCL (0.057 g) was dissolved in acetone (20 mL) under magnetic stirring at 3,500 rpm at 24.2 °C. Subsequently, sorbitan monooleate (Span 80) (0.0878 g) and BSO (0.3055 g) were added and kept under stirring at 40°C (Fisatom, model 713, São Paulo, Brazil) until complete solubilization of the organic phase components. The organic phase was then dripped at a flow rate of 2.5 mL/min into the aqueous phase composed of 50 mL of water containing polysorbate 80 (Tween 80) (0.2135 g). The mixture was maintained under vigorous magnetic stirring at 3.500 rpm at 40°C for 15 minutes. The organic solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator (Tecnal, model TE-211, Piracicaba, Brazil) until a final volume of 10 mL. Under the same conditions, PCL nanocapsules containing the typical medium chain triglycerides (MCT) were prepared as a negative control (NC-C).

2.4.1. Characterization of Blackberry Seed Oil-Loaded Nanocapsules (NCBSO)

2.4.1.1. Physicochemical Characterization of Nanocapsules

The mean particle size, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential were achieved after diluting a sample of the nanocapsule suspension (NCBSO) in ultrapure water at a 1:500 ratio. All measurements were conducted using the Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, United Kingdom). The samples were analyzed in triplicate. pH Values were measured using a digital potentiometer (Digimed, São Paulo, Brazil), which had been previously calibrated with pH 4.0 and 7.0 buffer solutions. The pH was directly measured in each colloidal suspension after its preparation.

2.4.1.2. Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy Coupled with Field Emission (FE-SEM)

The morphological and superficial evaluation of the samples was carried out using a MYRA 3 LMH scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) with field emission. Firstly, 1 mL of nanocapsules suspension (NCBSO) was diluted in 9 mL of ultrapure water, in the proportion of 1:10 (v/v). This solution was kept under magnetic stirring for 30 min at room temperature (Fisatom, model 752A, São Paulo, Brazil). Then the 10 mL of the solution was mixed in equal parts with 1% (w/v) solution of phosphotungic acid. The mixture was kept under magnetic stirring for 30 min. A 5 μL aliquot of the final suspension was deposited onto a 200-mesh copper TEM grid coated with carbon film followed by air-drying at room temperature (25 ± 2°C) for 24 h. The grid was examined, under the microscope (Tescan, Mira 3, Brno, Czech Republic) operated at an accelerating voltage of 30 to 300 kV.

2.5. Study of Physicochemical Stability of the NCBSO and NC-C

The nanocapsules loaded with blackberry seed oil (NCBSO) and control nanocapsules (NC-C) were subjected to stability studies under three storage conditions: (1) ambient temperature (25 ± 2°C), (2) accelerated conditions (37 ± 1°C), and (3) refrigerated conditions (4 ± 1°C), with protection from light exposure for 90 days. Physicochemical parameters including hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential were analyzed at predetermined intervals (0, 30, 60, and 90 days) using dynamic light scattering (DLS). All measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3). Physicochemical characterization was analyzed by Student’s t-test. The analyses were carried out with the software GraphPadPrism® 5.04 version (San Diego, CA, USA) and the significance level was p < 0.05.

2.6. Cell Culture

Human fibroblast cell line CCD1072Sk was cultivated in RPMI 1640 culture medium (Gibco Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 20% of fetal bovine serum, (Gibco Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and 1% of penicillin 100 U.mL-1/streptomycin 100 µg.mL-1 antibiotic solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cell growth was monitored daily in an inverted phase microscope, and the culture medium changed every 2 days. At pre-confluence, cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco Life Technologies, Paisley, UK).

2.7. MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

The MTT cytotoxicity assay was performed according to Mosmann (1983) [

18]. Cells were suspended in culture medium with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, counted in a Neubauer chamber, and plated in a 96-well plate (1.10

3 cells/well). After starvation, cells were treated with culture media supplemented with the BSO and NCBSO at 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 µg.mL

-1. After 24 h, the medium was replaced by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide test (MTT) (0.05 mg.mL

-1) and cells were incubated for 3 h. After this period, the MTT solution was removed and 100 µL of DMSO was added for formazan crystals solubilization. Cytotoxicity was assessed by the microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Multiskan FC, Waltham, MA, USA) at 590 nm. The optical density (OD) values were converted to % of cell viability using Equation 1:

2.8. Collagen Production Assay

Collagen production in human dermal fibroblasts treated with BSO and NCBSO was quantified using Picrosirius red staining [

19]. Cells were seeded in 12 well plates and treated, in triplicate, with BSO and NCBSO (10, 50 and 100 µg.mL

-1). The plates were incubated for 72 h in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO

2 at 37

o C. After this period, the culture medium was removed, and the wells were washed three times with PBS. Bouin’s solution was added and kept for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the plates were rinsed again with PBS and 1.5 mL of Sirius red solution was added (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The plates were then incubated for 1 h at 37

oC/5% CO

2. After this period, 1 mL of 0.01 mol.L

-1 hydrochloric acid solution was added and kept for 30 seconds. This step was repeated 3 times. Then, 1 mL of 0.1 mol.L

-1 NaOH was added, and the plates were homogenized for 30 minutes. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Multiskan

®FC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The optical density (OD) values were also converted to % using the Equation 1.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

The results were statistically analyzed using the GraphPadPrism® 5.04 version (San Diego, CA, USA). Tukey’s test was used to confirm differences between means considering a p-value lower than 0.05 (p < 0.05) as representative of statistical significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Characterization of the Blackberry Seeds Oils

Chemical characterization of blackberry seed oil (BSO) constituents was performed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS). Analysis was carried out in negative ionization mode, enabling simultaneous acquisition of precursor ion data from a single injection. Exploratory compound identification was achieved by comparing observed m/z values with literature-reported mass spectra (

Table 1), with subsequent classification.

Several compounds identified in this study have demonstrated biological activities and are reported in other

Rubus species, including: (a) organic acids (quinic, shikimic, citric, malic, and fumaric acid) [

20,

21,

22]; (b) carotenoids (lutein/zeaxanthin) [

23]; (c) flavonoids (quercetin-3-glucoside and (-)-catechin) [

24,

25]; (d) linoleic acid [

5]; and (e) cinnamic and hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (3,4-dimethoxycinnamic acid) [

26,

27]. 5-Hydroxyferulic acid (Ferulic acid derivative) was not previously reported in blackberry extracts. However, their biosynthetic precursors have been identified in the chemical profile of blackberries [

28]. Ellagitannins (e.g., casuarictin, potentillin) and their derivatives (valoneic acid dilactone) were identified in blackberry fruit extracts using HPLC-ESI-MS [

29]. In our study, these hydrolysable tannins were detected in blackberry seed oil (cultivar Xavante).

3.2. Nanocapsules Characterization

3.2.1. Determination of Mean Diameter, Polydispersity Index (PDI), and Zeta Potential of NCs

Both formulations presented an average diameter of 266.75 ± 2.01 nm (NCBSO) and 243.17 ± 3.88 nm (NC-C). Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between these nanoformulations, indicating that the oil did not present a detrimental effect on the size [

30].

Table 2 summarizes the results obtained.

The obtained diameter values were consistent with those reported in previous studies for essential oil-loaded nanocapsules, such as rosemary essential oil nanocapsules and

Lavandula angustifolia Mill. essential oil nanocapsules [

31]. Although these studies evaluated essential oils, the observed similarities in nanoparticle size suggest a corresponding encapsulation behavior. As previously reported [

10], polymeric nanoparticles typically exhibit diameters ranging from 100 to 300 nm. This size distribution is influenced by multiple factors, including formulation parameters (e.g., surfactant type and concentration), preparation method (e.g., nanoprecipitation, emulsion-diffusion), core composition (e.g., oil polarity and viscosity), polymer properties (e.g., molecular weight, hydrophobicity), drug-loading status (presence/absence of active pharmaceutical ingredients).

The polydispersity index (PDI), scaled from 0 to 1, quantitatively reflects the size uniformity of nanoparticles in suspension, where values approaching 0 indicate monodisperse systems with narrow size distributions [

32]. All formulated nanocapsules exhibited PDI values below 0.5, demonstrating homogeneous nanoparticle population, unimodal size distribution behavior, and optimal colloidal stability suitable for pharmaceutical applications. [

33]. A uniform particle size distribution is obtained when the organic and aqueous phases are rapidly mixed to form a homogeneous dispersion [

10,

34].

The zeta potential reflects the electrostatic stabilization efficiency of colloidal systems, where absolute values ≥30 mV indicate suitable interparticle repulsion forces. This electrostatic barrier prevents aggregation by overcoming van der Waals attraction forces, even during Brownian motion-induced collisions, thereby maintaining system stability [

10,

35,

36]. The NCBSO formulation exhibited a pH of 5.51 ± 0.38 closely matching the physiological pH range of healthy skin (4.5-5.5). This intrinsic compatibility with cutaneous pH homeostasis, combined with demonstrated colloidal stability, suggests excellent suitability for topical applications while minimizing risks of irritation or barrier disruption. [

37].

Thus, the physicochemical characteristics of the nanoparticles play a crucial role in the bioactivity of the polymeric nanocapsules, influencing drug release, stability, and interaction with biological membranes. The nanometric size of the particles results in a high surface area. This enhances interaction with biological membranes and facilitates cellular absorption. As a result, the therapeutic efficacy of the encapsulated active is improved. Additionally, nanoparticles enable controlled release, allowing targeted and suitable drug delivery into skin [

9,

10,

35].

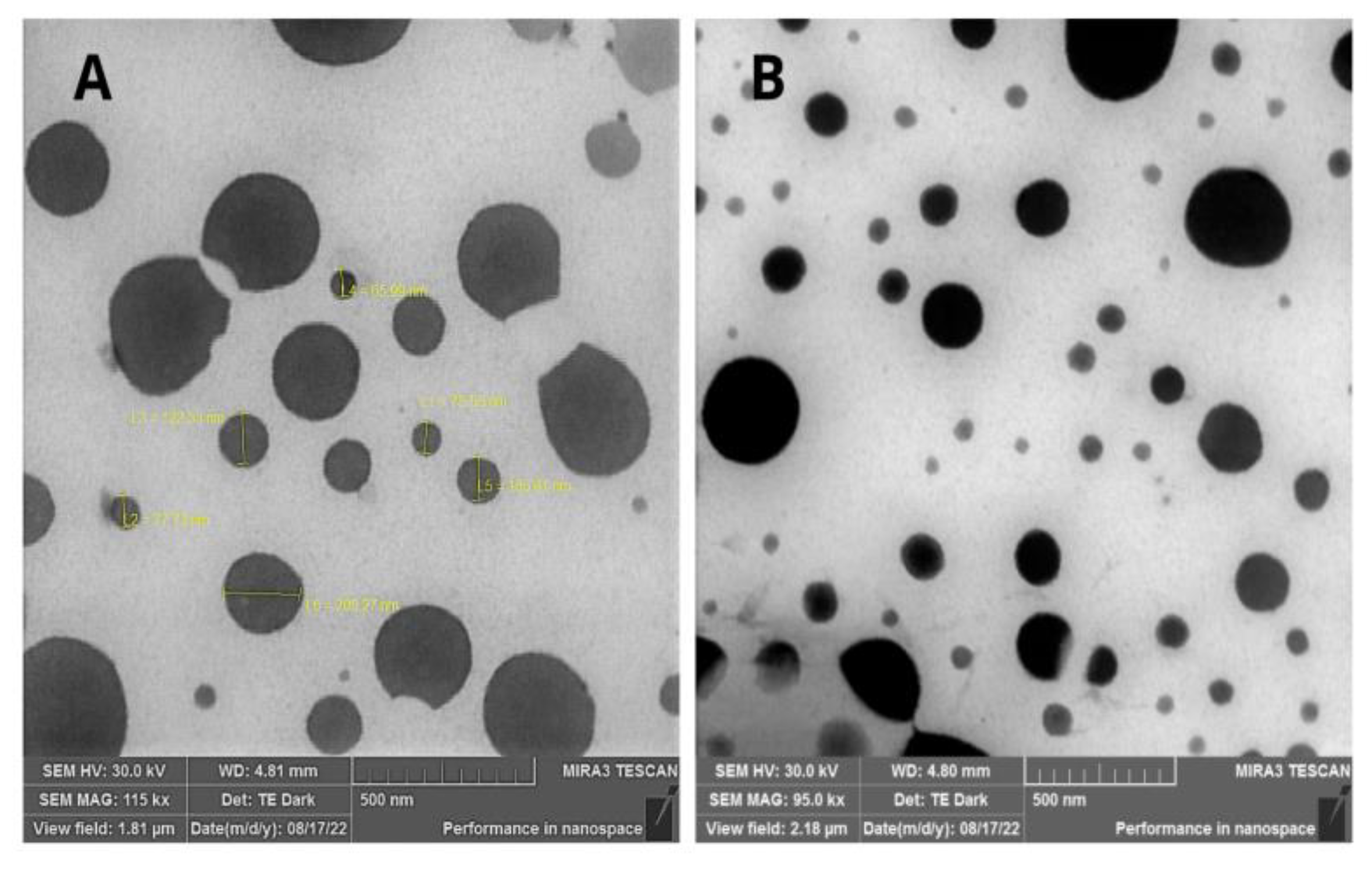

3.2.2. Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy Coupled with Field Emission (FE-SEM)

Figure 1 depicts the photomicrographs obtained for NCBSO. It was possible to observe particles with a well-defined spherical shape and a smooth and uniform surface. The diameter of the particles corresponded to that determined by DLS.

FE-SEM images revealed the core-shell architecture of the polymeric nanocapsules by displaying a discrete darker periphery corresponding to the PCL polymeric wall and a lighter central region associated with the oily core containing BSO [

38]. This morphology is consistent with both the known film-forming properties of PCL and previous reports of nanocapsules prepared via interfacial deposition method of preformed polymer using this polymer [

20,

39,

40].

3.3. Study of Physicochemical Stability of the NCBSO and NC-C

Polymeric nanocapsules are promising carriers for topical application, offering high stability to active ingredients and improving their concentration and distribution [

2,

14,

15]. These properties are especially advantageous for plant-based compounds, which are known for their low stability [

1,

13,

41,

42,

43]. However, the long-term stability of these nanoparticles remains a challenge, as poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanocapsules can undergo degradation in aqueous media [

44,

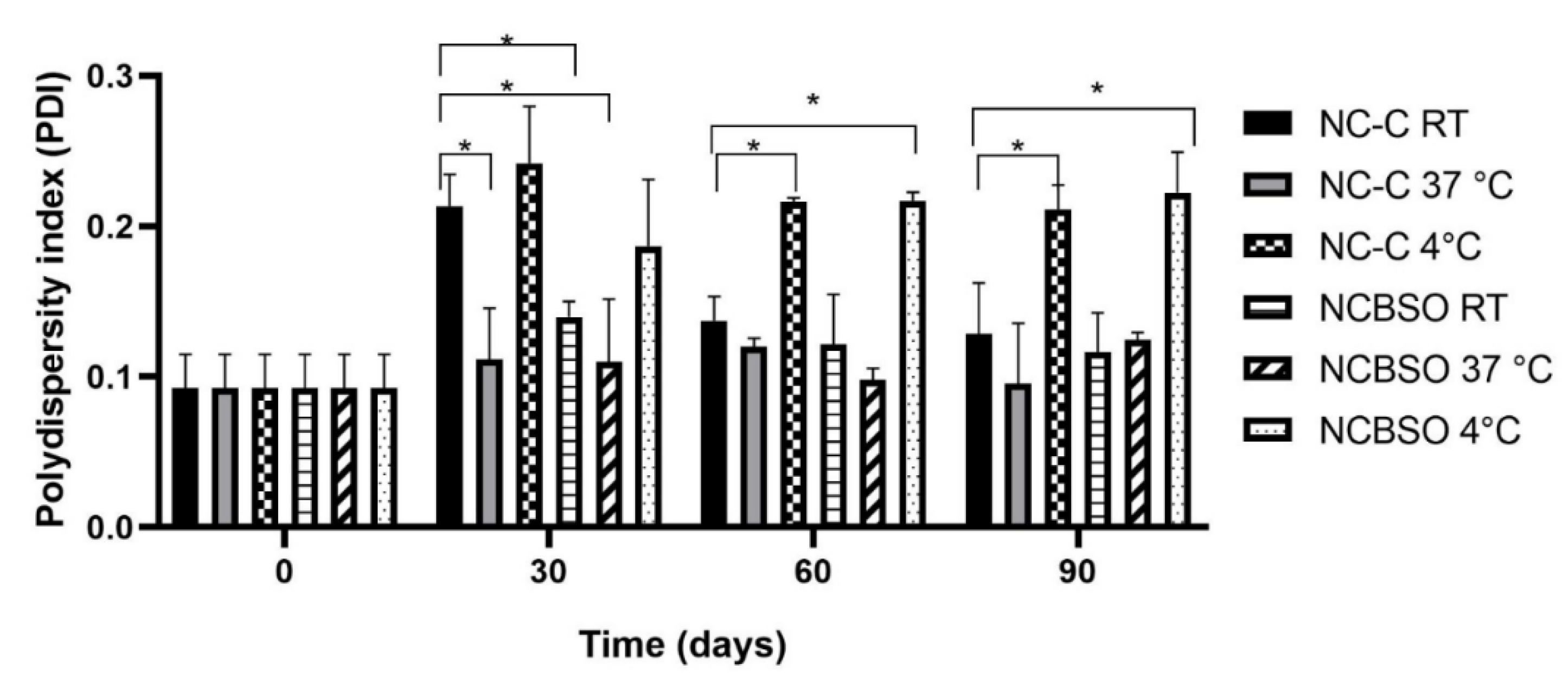

45]. Thus, the stability study was performed at different temperatures for evaluating the physicochemical behavior at different temperatures. The results are depicted in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Macroscopic evaluation revealed that both NC-C and NCBSO retained their characteristic milky-white opalescence throughout the 90-day stability study. The formulations exhibited no detectable signs of instability, including precipitation, chromatic variation, or phase separation under the tested storage conditions (4°C, room temperature, and 37°C). This colloidal homogeneity and absence of macroscopic alterations demonstrated the physical stability of the nanocapsule systems. Therefore, PCL-based nanocapsules exhibited macroscopic stability, maintained by persistent Brownian motion that prevented particle flocculation and coalescence during extended storage periods [

10,

45]. In addition, the PCL nanocapsules maintained their nanometric size, remaining below 300 nm throughout the study period and under different storage temperature conditions. This stable colloidal behavior ensures uniform dispersion homogeneity while preserving nanocarrier properties, demonstrating potential as an advanced delivery platform for blackberry seed oil (BSO) in pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications.

However, as shown in

Figure 2, some stored samples demonstrated an increase in the polydispersity index (PDI) from day 30. Although this feature may be considered a physicochemical problem, the values remained within the pharmaceutically acceptable range (<0.3) throughout the study period. In addition, the temperature-dependent behavior likely reflects enhanced droplet mobility and incipient aggregation dynamics. Although the NCBSO and NC-C formulations presented different oils in the oily core, the behavior in terms of polydispersity was very similar, which evidenced the reproducibility of the nanoencapsulation method used [

9,

10,

11].

Zeta potential analysis revealed no significant influence of BSO nanoencapsulation on surface charge characteristics, as demonstrated by comparing the NC-C and NCBSO formulations (p > 0.05) in

Figure 3. However, storage temperatures provided a perceptible effect, in which samples maintained at 37°C revealed significantly lower zeta potential (p < 0.05) comparing to those stored at 4°C and room temperature. Despite this, most of the zeta potential values were adequate as these data were higher than |30 mV|, which is usually considered appropriate to provide repulsive force to achieve a physical colloidal stability [

11,

45].

These changes in zeta potential values may be associated with PCL hydrolysis in both NC-C and NCBSO. This result was previously achieved by Camargo et al. (2020) [

45], who reported the degradation of PCL nanoparticles with a similar composition after 90 days of storage at room temperature. Stability assessments confirmed that the nanocapsule suspensions maintained their critical physicochemical parameters within suitable limits throughout the 90-day study period, demonstrating acceptable variations across all storage conditions (4°C, RT, and 37°C). This adequate stability in the face of temperature variation suggests robust formulation design capable of preserving the macroscopic colloidal stability, the particle size distribution, and the surface charge characteristics. This colloidal stability was also attributed to the effect of the surfactant system, composed of Span 80 and Tween 80, which appropriately stabilizes the oily core of the nanocapsules [

9,

39,

45].

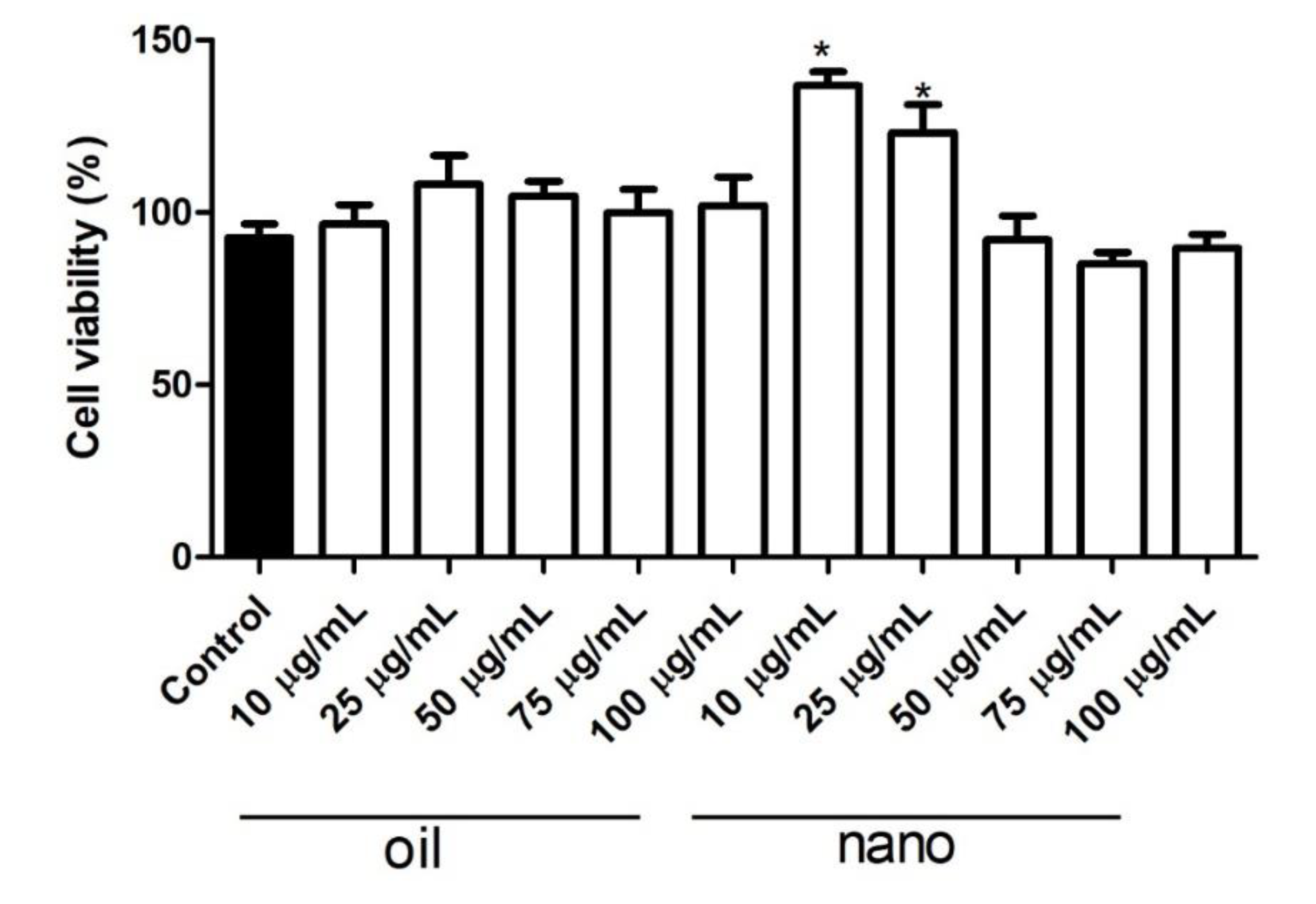

3.4. MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

Figure 4 shows the MTT assay result. At the tested concentrations (10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg.mL

-1), BSO and NCBSO presented no cytotoxic effect to the human fibroblast cell line

CCD1072Sk. According to the ISO 10993-5:2009 standard, a product is considered cytotoxic when cell viability is reduced to lower than 70%, which was not observed in this study [

46]. In particular, NCBSO not only prevented cytotoxicity but also induced a significant increase in cell viability at concentrations of 10 and 25 μg.mL

-1 (p < 0.05) by providing a cytoprotective effect [

31,

47,

48]. The observed increase in cell viability with NCBSO can be attributed to the controlled release and antioxidant potential of bioactive compounds from BSO, resulting in lower cytotoxicity. Thus, the BSO nanoencapsulation offers an actual, sustainable, and innovative approach to enhancing the safety of fatty oils in cosmetic and pharmaceutical contexts.

Manssor et al. (2022) [

49] synthesized titanium nanoparticles via three distinct methods (

Cassia fistula extract,

Bacillus subtilis mediation, and hydrothermal synthesis) and evaluated their cytotoxicity in L929 mouse fibroblasts. The

Cassia fistula-derived nanoparticles exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity compared to other synthesis routes, which the authors attributed to residual organic solvents from the extraction process. In contrast, our study utilized supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, a solvent-free approach that yielded both the blackberry seed oil and derived nanocapsules with no detectable cytotoxicity.

Grajzer et al. (2021) [

50] demonstrated that raspberry seed oil extracted via supercritical CO₂ and its derived nanoemulsion exhibited selective cytotoxicity, significantly reducing viability in colon and breast cancer cell lines while remaining non-toxic to human dermal fibroblasts. This differential activity was attributed to bioactive compounds in the oil that specifically target cancer cell pathways without affecting normal cells.

Multiple studies with nanoencapsulated natural products have demonstrated that the nanoencapsulation process not only preserves product safety but may even reduce cytotoxicity in certain cell lineages [

31,

51,

52,

53,

54]. These findings confirm that nanoencapsulation serves as an effective strategy to protect bioactive compounds from oxidative degradation, enhance physicochemical stability, optimize delivery and tissue penetration, and maintain or improve biological safety profiles.

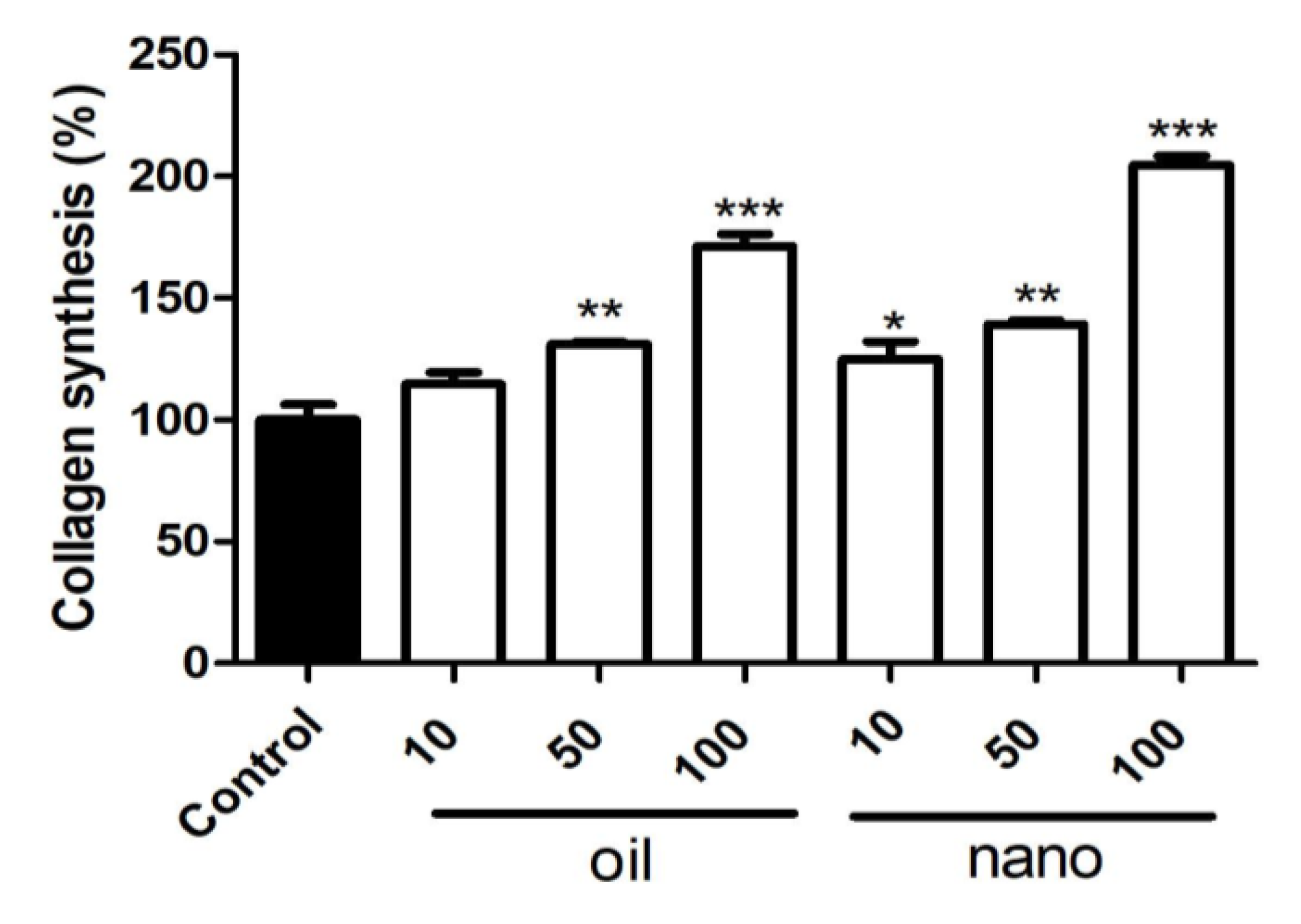

3.5. Collagen Production Assay

The impact of BSO and NCBSO on collagen production in CCD1072Sk cells was positive as shown in

Figure 5. NCBSO exhibited a more pronounced effect at 10, 50, and 100 µg.mL

-1, suggesting that nanoencapsulation enhances this desirable collagen stimulating property of BSO. The results revealed a dose-dependent increase in collagen production following treatment with both BSO and NCBSO compared to the negative control (

Figure 5). At the highest concentration tested (100 µg.mL

-1), BSO and NCBSO induced a significant elevation in collagen production by 170% and 200% compared to untreated cells (p < 0.01), respectively. In particular, NCBSO significantly enhanced collagen production compared to free BSO at 100 µg·mL⁻¹ (p < 0.05), leading to improved collagen-boosting performance.

A previous study reported the role of blackberry in skin repair and extracellular matrix modulation. Aksoy et al. (2020) [

55] described that

Rubus tereticaulis P.J. Müll. enhances wound healing by promoting collagen synthesis. Similarly, Meza et al. (2020) [

2] demonstrated that

Rubus fruticosus L. extract upregulates elastin gene transcription, stimulates tropoelastin production, and inhibits leukocyte and fibroblast-derived elastase activity. Although further investigation is needed, these findings suggest that blackberry-derived compounds may simultaneously enhance collagen and elastin synthesis—key mechanisms for improving skin tonicity and elasticity. Such dual activity highlights their potential as promising bioactive ingredients for cosmetic applications.

Other studies related to nanostructures loaded with plant-derived bioactive compounds have similarly demonstrated enhanced collagen synthesis, corroborating the findings of this study. For instance, Hajialyani et al. (2018) [

56] reported that nanostructured curcumin significantly improved wound healing in a murine model by promoting collagen deposition, increasing myofibroblast proliferation, stimulating capillary formation, and enhancing wound contraction. Likewise, Pires et al. (2020) [

57] found that nanoencapsulated

Caryocar brasiliense Cambess oil accelerated dermal regeneration and markedly upregulated type I collagen production. This enhanced collagen synthesis may be attributed to the ability of nanostructures to improve the bioavailability of active compounds while facilitating the cellular uptake of growth factors and cytokines critical for tissue repair.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and characterized poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanocapsules encapsulating supercritical CO₂-extracted blackberry (Rubus spp. Xavante cultivar) seed oil (BSO), demonstrating their potential as a sustainable and bioactive ingredient for skincare applications. UHPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS analysis revealed that BSO contains bioactive compounds (e.g., phenolic acids, carotenoids, tannins, flavonoids, and unsaturated fatty acids). The optimized nanocapsules (NCBSO) exhibited ideal physicochemical properties—nanometric size, low polydispersity, and negative zeta potential, while maintaining colloidal stability over 90 days under different storage conditions. NCBSO showed no cytotoxicity and significantly enhanced collagen production in human fibroblasts, confirming that nanoencapsulation increased this bioactivity. PCL nanocapsules demonstrated promising potential for the topical delivery of blackberry seed oil, overcoming the limitations of the free compounds and supporting its application in sustainable cosmeceutical formulations.

Author Contributions

BSO extraction and chromatographic characterization were performed by Mariana D. Miranda and Madeline S. Correa. Nanocapsule preparation was carried out by Mariana D. Miranda and Guilherme dos Anjos Camargo. Physicochemical characterization and stability assessment were conducted by Amanda Jansen, Brenda A. Lopes, and Jessica Mendes Nadal. Cell-based studies, including MTT assay and collagen production, were performed by Daniela F. Maluf, Mariana D. Miranda, Luana C. Teixeira, and Ana P. Horacio. FE-SEM analysis was conducted by Jane Manfron. Statistical analysis and manuscript writing were performed by Patrícia M. Döll-Boscardin, with manuscript revision by Jessica Mendes Nadal. The study was supervised by Paulo Vitor Farago, who also contributed to the final manuscript writing.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian funding agencies for financial support and scholarships: M. S. Correa thanks the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel – Brazil (CAPES - Finance Code 001, grant number 88882.381633/2019-01); P. V. Farago is grateful for Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (grant number 310806/2025-9).

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the C-LABMU/UEPG for supporting instrumental analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ekiert, H.M.; Szopa, A. Biological Activities of Natural Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, D.; Li, W.H.; Seo, I.; Parsa, R.; Kaur, S.; Kizoulis, M.; Southall, M.D. A Blackberry-Dill Extract Combination Synergistically Increases Skin Elasticity. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 2020, 42, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, A.P. F.; et al. Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) Residues: A Comparison with Conventional Methods. Food Research International 2015, 77, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustinelli, G.; et al. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Berry Seeds: Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity. Journal of Food Quality 2018, 2018, 6046074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.S.; Fetzer, D.L.; Hamerski, F.; Corazza, M.L.; Scheer, A.P.; Ribani, R.H. Pressurized Extraction of High-Quality Blackberry (Rubus spp. Xavante Cultivar) Seed Oils. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2021, 176, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluf, D.F. Cytoprotection of Antioxidant Biocompounds from Grape Pomace: Further Exfoliant Phytoactive Ingredients for Cosmetic Products. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammari, N.; et al. Nanocapsules Containing Saussurea lappa Essential Oil: Formulation, Characterization, Antidiabetic, Anti-Cholinesterase and Anti-Inflammatory Potentials. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 593, 120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, M.S.; et al. Supercritical CO₂ with Co-Solvent Extraction of Blackberry (Rubus spp. Xavante Cultivar) Seeds. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2022, 189, 105702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; et al. Polymeric Nanocapsules as Nanotechnological Alternative for Drug Delivery System: Current Status, Challenges and Opportunities. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffazick, S.; et al. Characterization and Physicochemical Stability of Nanoparticulate Polymeric Systems for Drug Delivery. Química Nova 2003, 26, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarai, B.M. Polymeric Nanoparticles. Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications 2020, 308–324. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, P.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Biocompatible Nanoparticles and Vesicular Systems in Transdermal Drug Delivery for Various Skin Diseases. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2019, 555, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordorski, B.; Landriscina, A.; Friedman, A. Chapter 3 - An Overview of Nanomaterials in Dermatology. Nanoscience in Dermatology 2016, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, P.C.; et al. Polymer-based Biomaterials for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications: A Focus on Topical Drug Administration. European Polymer Journal 2023, 187 868. [CrossRef]

- Janmohammadi, M.; Nourbakhsh, M.S. Electrospun Polycaprolactone Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering: A Review. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials 2018, 68, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetzer, D.L.; Cruz, P.N.; Hamerski, F.; Corazza, M.L. Extraction of Baru (Dipteryx alata Vogel) Seed Oil Using Compressed Solvents Technology. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2018, 137, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fessi, H.; et al. Nanocapsule Formation by Interfacial Polymer Deposition Following Solvent Displacement. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1989, 55, R1–R4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. Journal of Immunological Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanovska, A.; et al. Cell Viability and Collagen Deposition on Hydroxyapatite Coatings Formed on Pretreated Substrates. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2021, 258, 123978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.P.; et al. Rubus ulmifolius Schott Fruits: A Detailed Study of Its Nutritional, Chemical and Bioactive Properties. Food Research International 2019, 119, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; et al. Composition of Sugars, Organic Acids, and Total Phenolics in 25 Wild or Cultivated Berry Species. Journal of Food Science 2012, 00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra-Rojas, Q.; et al. Organic Acids, Antioxidants, and Dietary Fiber of Mexican Blackberry (Rubus fruticosus) Residues cv. Tupy. Journal of Food Quality 2018, 2018, 950761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.S.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Alves, G.; Silva, L.R. Blackberries and Mulberries: Berries with Significant Health-Promoting Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 12024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadi, H.E.; Bouzidi, H.E.; Selama, G.; et al. Characterization of Rubus fruticosus L. Berries Growing Wild in Morocco: Phytochemical Screening, Antioxidant Activity and Chromatography Analysis. European Food Research and Technology 2021, 247, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellappan, S.; Akoh, C.C.; Krewer, G. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Georgia-Grown Blueberries and Blackberries. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2002, 50, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadernowski, R.; Naczk, M.; Nesterowicz, J. Phenolic Acid Profiles in Some Small Berries. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2005, 53, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Lahlou, R.A.; Silva, L.R. Phenolic Compounds from Cherries and Berries for Chronic Disease Management and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, M.; et al. Blackberry (Rubus ulmifolius Schott): Chemical Composition, Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Two Edible Stages. Food Research International 2019, 122, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, T.J.; Howard, L.R.; Prior, R.L. Ellagitannin Composition of Blackberry As Determined by HPLC-ESI-MS and MALDI-TOF-MS. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2008, 56, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassot, J.M.; Ribas, D.; Silveira, E.F.; Gruenspan, L.D.; Pires, C.C.; Farago, P.V.; et al. Beclomethasone dipropionate-loaded polymeric nanocapsules: Development, in vitro cytotoxicity, and in vivo evaluation of acute lung injury. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.M.; et al. Lavandula angustifolia Essential Oil-Loaded Nanocapsules and Biological Activity on Fibroblasts. International Journal of Development Research 2021, 11, 46106–46110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayata, N.; Abdelwahed, W.; Chehna, M.F.; Charcosset, C.; Fessi, H. Preparation of Vitamin E Loaded Nanocapsules by the Nanoprecipitation Method: From Laboratory Scale to Large Scale Using a Membrane Contactor. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2012, 423, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Y.; Hwang, J.B.; Bang, S.H.; Darby, D.; Cooksey, K.; Dawson, P.L.; Park, H.J.; Whiteside, S. Formulation and Characterization of α-Tocopherol Loaded Poly-ε-Caprolactone (PCL) Nanoparticles. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwalter, C.E.; Pagels, R.F.; Wilson, B.K.; Ristroph, K.D.; Prud'homme, R.K. Flash Nanoprecipitation for the Encapsulation of Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Compounds in Polymeric Nanoparticles. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2019, 143, e58757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. Nanoparticles Types, Classification, Characterization, Fabrication Methods and Drug Delivery Applications. In Natural Polymer Drug Delivery Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P.M.; Praça, F.G.; Mussi, S.V.; Figueiredo, S.A.; Fantini, M.C.A.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Torchilin, V.P.; Bentley, M.V.L.B. Liquid Crystalline Nanodispersion Functionalized with Cell-Penetrating Peptides Improves Skin Penetration and Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Lipoic Acid After In Vivo Skin Exposure to UVB Radiation. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2020, 10, 1810–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Wendtner, M.H.; Korting, H.C. The pH of the Skin Surface and Its Impact on the Barrier Function. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology 2006, 19, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.M.; et al. Diphenyl Diselenide Loaded Poly(ε-caprolactone) Nanocapsules with Selective Antimelanoma Activity: Development and Cytotoxic Evaluation. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2018, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, S.; Devi, B.; Kandimalla, R.; Sharma, K.K.; Sharma, A.; Kalita, K.; Kataki, A.C.; Kotoky, J. Chloramphenicol Encapsulated in Poly-ε-caprolactone-Pluronic Composite Nanoparticles for Treatment of MRSA-Infected Burn Wounds. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2971–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.P.; et al. Poly-ε-caprolactone Nanocapsules Loaded with Copaiba Essential Oil Reduce Inflammation and Pain in Mice. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 642, 123147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, F.C.; et al. Nanostructured Systems Containing an Essential Oil: Protection Against Volatilization. Química Nova 2011, 34, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihranyan, A.; Ferraz, N.; Strømme, M. Current Status and Future Prospects of Nanotechnology in Cosmetics. Progress in Materials Science 2012, 57, 875–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brum, A.A. S.; et al. Lutein-Loaded Lipid-Core Nanocapsules: Physicochemical Characterization and Stability Evaluation. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2017, 522, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, A.; et al. A Comparative Study of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) Essential Oil-Based Polycaprolactone Nanocapsules/Microspheres: Preparation, Physicochemical Characterization, and Storage Stability. Industrial Crops and Products 2019, 140, 111669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, G.A.; et al. Stability Testing of Tacrolimus-Loaded Poly(ε-caprolactone) Nanoparticles by Physicochemical Assays and Raman Spectroscopy. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2020, 111, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 10993-5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. In Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices 2009, 42. International Organization for Standardization. ISO 10993-5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. In Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices 2009, 42.

- Codevilla, C.F.; Bazana, M.T.; Silva, C.B.; Barin, J.S.; Menezes, C.R. Nanostructures Containing Bioactive Compounds Extracted from Plants. Ciência e Natura 2015, 37, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, Z.A. A.; et al. Role of Nanotechnology for Design and Development of Cosmeceutical: Application in Makeup and Skin Care. Frontiers in Chemistry 2019, 7, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; et al. Effect of Currently Available Nanoparticle Synthesis Routes on Their Biocompatibility with Fibroblast Cell Lines. Molecules 2022, 27, 6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grajzer, M.; et al. Bioactive Compounds of Raspberry Oil Emulsions Induced Oxidative Stress via Stimulating the Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and NO in Cancer Cells. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 5561672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józsa, L.; et al. Enhanced Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Self-Nano and Microemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems Containing Curcumin. Molecules 2022, 27, 6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, N.S.; et al. Nanoencapsulation of Buriti Oil (Mauritia flexuosa L.f. ) in Porcine Gelatin Enhances the Antioxidant Potential and Improves the Effect on the Antibiotic Activity Modulation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, D.S.; Joseph, J.; Vineeth, C.A.; John, A.; Abraham, A. Green Synthesis of Cuminum cyminum Silver Nanoparticles: Characterizations and Cytocompatibility with Lapine Primary Tenocytes. Journal of Biosciences 2021, 46, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavasoli, M.; Tatari, M.; Samadi Kazemi, M.; Taghizadeh, S.F. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Cuminum cyminum Essential Oil Loaded SLN Nanoparticle. Nanomedicine Journal 2022, 9, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, H. ; Demirbağ,, Ç. Evaluation of Biochemical Parameters in Rubus tereticaulis Treated Rats and Its Implications in Wound Healing. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2020.

- Hajialyani, M.; Tewari, D.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Nabavi, S.M.; Farzaei, M.H.; Abdollahi, M. Natural Product-Based Nanomedicines for Wound Healing Purposes: Therapeutic Targets and Drug Delivery Systems. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 5023–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, J.; et al. Healing of Dermal Wounds Property of Caryocar brasiliense Oil Loaded Polymeric Lipid-Core Nanocapsules: Formulation and In Vivo Evaluation. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 150, 105356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).