1. Introduction

Nomadism is a way of life which is specific to certain populations and is characterised by constant mobility from one environment to another in search of suitable living [

1,

2]. In Africa, there are an estimated 50 million nomads living in several countries, and this population is made up of three major groups: herders, migrant fishermen and farmers [

3]. Nomads are renowned for their ability to adapt and live in difficult environments (desert, steppe, mountainous areas), and the reasons for their mobility include the changing seasons of the year, the structure and size of the family, the type of activity carried out by the group, wars and conflicts [

4,

5]. As a result of this lifestyle, nomads are among the communities most vulnerable to exclusion from basic social services such as education and healthcare. Furthermore, periodic exposure to the risks of disease through migration, seasonal periods, difficult hygienic conditions, untimely response to disease, inadequate information, and close contact with livestock puts them at greater risk of diseases (NTDs, polio, tuberculosis) and epidemics/pandemics (like cholera, monkeypox, COVID-19, measles) [

6,

7]. The resulting health implications are that they are among the communities in Africa with the highest morbidity and mortality rates for a number of preventable diseases, and that they can often be reservoirs or vectors for certain diseases [

8]. In line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 "to enable all people to live in good health and promote well-being at all ages"[

9]. Studies have been carried out in certain African countries that are home to these populations, described by the WHO and UNICEF as "difficult to reach"[

10], with the aim of improving their access to basic health services. In Cameroon, there is a dearth in data on the health situation of nomadic populations, which is why we conducted this study on the determinants of adherence to vaccination and other basic health care services among nomadic populations in northern Cameroon. The general objective of the study was to determine the perceptions and practices that influence the use of health care in general and vaccination in particular among nomadic populations in Cameroon. The results obtained are to be used not only to enrich the literature but above all to develop strategies to increase the use of health services by nomadic populations.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

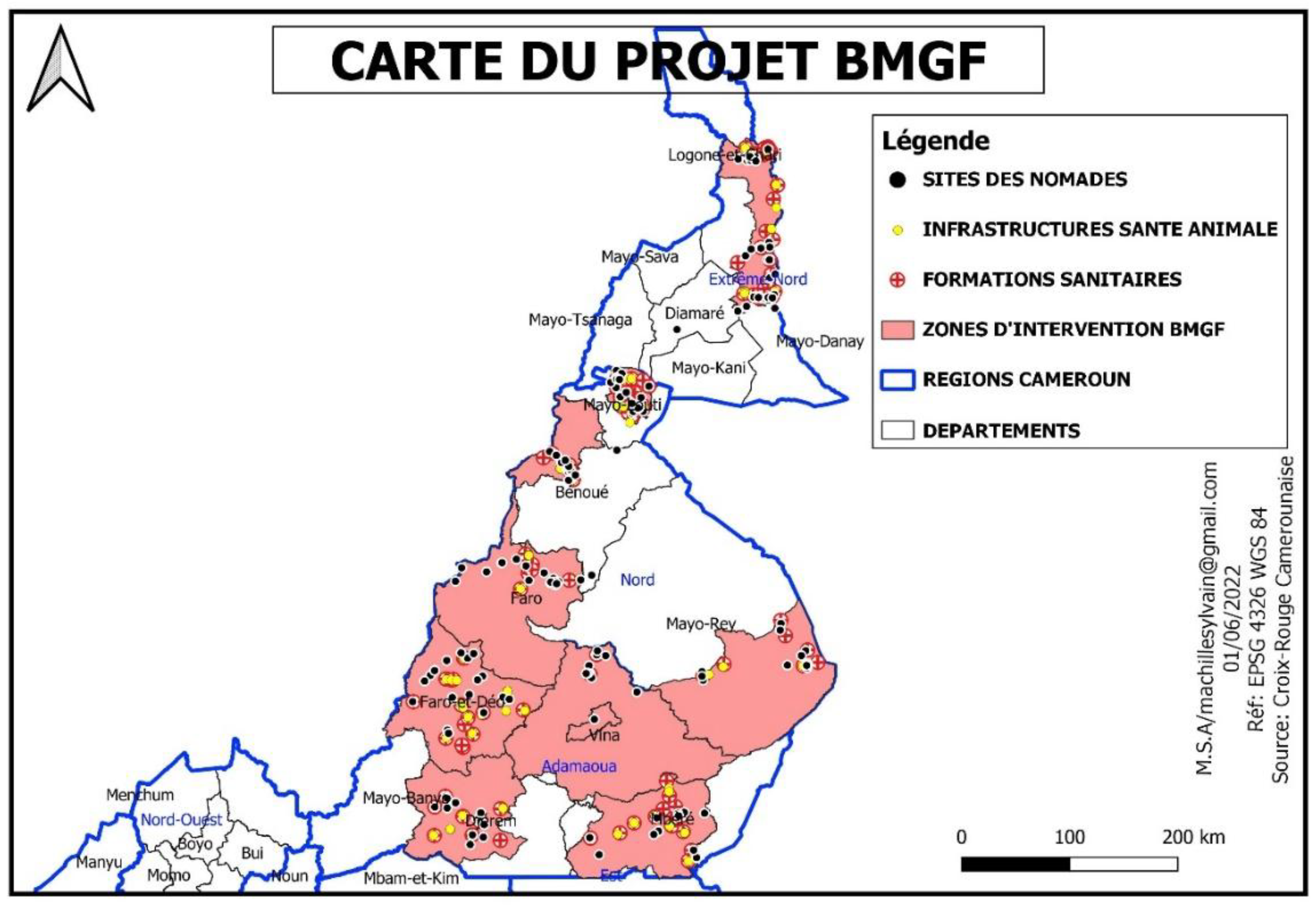

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in ten health districts in 03 regions: Adamawa (04 districts), North (02 districts) and Far North (04 districts) regions of Cameroon. (

Figure 1)

We included consenting nomads, 18 years and above in March of 2022. A Nomad was considered as a person or a group of people without a fixed habitation, who regularly move from one place to another one, usually in search of good pasture for animals. Those who had a fixed habitation for more than three years were excluded from the study and considered as sedentary in the locality. We did an exhaustive sampling of camps, including all the nomad camps in our study area.

Procedure

Following the acquisition of necessary administrative authorizations, a comprehensive process was undertaken to meticulously establish a framework for the investigation. The initial phase encompassed engagements with personnel from various health districts, during which consultations were held with both health area staff and community health workers. The principal objective of these deliberations was to meticulously identify and document the geographic locations of nomadic encampments within their respective regions.

Data Collection

Data collected included participants' sociodemographic characteristics, their source of information about health care and vaccination, their knowledge and attitude towards vaccination, their beliefs about disease causes, challenges encountered while requesting health care, and suggestions to address those challenges in order to improve uptake. All of this data was gathered immediately in a data entry application designed in Kobo Tool Box for remote data gathering. Interviewers were recruited from the surrounding areas and trained in data collection techniques. As a result, data were collected in local languages for people who could not communicate in French or English.

Data Analysis

Data collected were export for analysis in SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Mean ± standard deviation was used for description of normally distributed variables, while median (interquartile range) were used for skewed variables.

Ethical Consideration

This study was conducted within the scope of a project implemented by Cameroon red cross in its current activities and funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The project aimed to census nomad population to have a clear data base to follow-up immunization activities in this population. Prior to the inclusion of participants, the survey was approved and undertaken by the regional delegation of health for the three regions, as well as local administrative and traditional authorities. The objectives and purpose of the study were explained to community leaders, camps’ chief and each participant. Due to low literacy rate in this population and some logistic and contextual constraints, a written informed consent was not requested. Verbal consent was considered, and the participant was free to accept or refuse without any penalty, as well as to withdraw from the study at any time during the interview. Data were collected and managed anonymously.

3. Results

Overall, data were collected from 141 camps, 42 in Adamawa region, 35 in Far-North region and 64 in North region. The mean number of sites per year for each nomad group was 2.3 ± 0.9, with a minimum of one site and a maximum of 5 sites. Moreover, nomad groups were living in each site for 5.7 ± 3.1 months in average.

Determinants of Immunization Uptake

About 1 participant out of 5 had never heard about immunization (21.5%), and up to 25% of the population didn’t know the use of the immunization. Moreover, half of the study population was unable to cite at least one vaccine-preventable disease (51.3%).

Concerning the accessibility of the immunization service, 64.8% declared it was available while 71.2% said it was accessible. Most of the responders said vaccines can prevent disease (73.5%). About a quarter of participants didn’t vaccinate their children (24.2%). Among those who had used vaccination services, 68.2% had an immunization card. Challenges faced during immunization program were poor information, long distance, lack of time to go to the facility, bad attitude of staff respectively for 6.1%, 5.9%, 3.0% and 2.2% of the population respectively. Bringing vaccination points closer to camp (50.6%) and using door-to-door strategy (53.5%) were the most suggested improvements to increase the uptake of the service by the population (

Table 2).

Determinants of Other Health Care Service Uptake

Poor hygiene was the most cited cause of disease (65.7%), followed by “Bad air” (29.8%) and witchcraft (18.4%). One-third of the participants thought some diseases couldn’t be cured in health facilities, traditional healers been the alternative for 68.2% of participants.

The Median time to nearest health facility was 45 minutes (IQR: 20 – 90), with three quarter of participants going by foot. The majority of nomads had to pay in advance (80%) for healthcare services, and just 5.0% was prepaid by insurance. The cost was considered affordable by just 47.4% of study population. Most of the participants (61.3%) were using health care services only for some of their health problems, as the offer meets only some of their needs. Care that should be added to health service offer were management of malnutrition (55.9%) and mosquitoes net (56.4%). (

Table 3)

4. Discussion

The aim of our study was to determine the perceptions and practices that influence the use of healthcare in general and vaccination in particular by nomadic populations in Cameroon. The survey took place in 141 nomadic camps, where we interviewed 826 participants, 510 of whom were men. The majority (49.4%) were aged between [25 and 45]. The mean number of nomadic camp relocations per year was 2.3 ± 0.9.

Determinants of Vaccination

The study showed that around one in five participants had never heard of vaccination, 25% of participants were unaware of the effects of vaccination and half of the population were unable to name at least one vaccine-preventable disease. However, belief in vaccines was high. In the light of this information, we can see that the nomads are not sufficiently informed about vaccination and the diseases it prevents, despite the existence of numerous awareness-raising strategies implemented by the players involved in the fight against vaccine-preventable diseases. This lack of information, despite the good belief in vaccination, may be linked to the participants' level of education. This emphasises the constraints and difficulties experienced by awareness-raising initiatives. The majority of responders (71.2%) acknowledged to having access to and availability of immunisation services. We should also point out that more than half of the participants had vaccinated their kids, and that 68.2% of those who did so had their vaccination records with them. Contrary to popular belief, this condition is not significantly different among those who are sedentary, which may show that the expanded programme of immunisation is open to all populations. Long distances, a lack of time to get to the medical facility, and the staff's unfavourable attitude towards the populace are obstacles that prevent the population from receiving immunisations. These issues were also noted in research conducted in Africa by Victoria M. Gammino et al.2020[

8], and Sangaré et al.2012 in Mali[

11]. This similarity in results could be indicative of the fact that nomads face the same health-seeking difficulties regardless of the country in which they live. The suggestions made by the participants to increase the use of the vaccination service were to bring the vaccination points closer to the nomad camps and to use a door-to-door strategy. These suggestions are in line with the difficulties that these populations face in getting their children vaccinated.

Determinants of Health Care Services Utilization

Regarding perceptions of health care seeking, a third of participants think that not all illnesses are treated in health services. The identified attitudes show that nomadic populations preferred the use of traditional medicine as an alternative (68.2%), and the majority of participants (61.3%) only go to health services for specific illnesses. These results are consistent with those found by Djimet Seli et al.2017 in Chad.[

12] who discovered a variety of reasons for these beliefs and practises, including the perception of some illnesses as a supernatural experience, the proximity of the marabouts, and the low cost of treatment by the marabouts. Given that the Cameroonian and Chadian nomad camps share the same broad geographical area, i.e. the Southern Sahara, and have comparable culture and behaviours, these conditions could possibly be applicable to our study group[

13]. Moreover, this high rate of consultation of traditional medicine is in agreement with the results of the Third Cameroonian Household Survey (ECAM III)[

14], which reported a low rate of consultation of formal health structures in favour of informal structures in the Far North of Cameroon. With respect to the cost of care and method of payment, the participants (80.0%) paid for their care in advance and the costs were affordable for 50.0% of the participants. These results are in line with those obtained in surveys carried out in Cameroon in previous years, which showed that 70.4% of health funding comes directly from households and that around 50% of Cameroonians use all their income for health care [

14,

15].

A limitation of this study is that the results obtained do not allow us to say whether the determinants identified are linked to the use of vaccination and other health care seeking behaviour, and in what way they influence it.

The results obtained in this study reflect health determinants linked specifically to the lifestyle and culture of nomadic peoples on the one hand, and on the other hand the realities and/or difficulties encountered in accessing healthcare throughout Cameroon, regardless of ethnicity or culture.

5. Conclusions

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

Despite the study's limitations, the complete insights gained shed light on the intricate web of influences influencing healthcare and immunisation among nomadic groups. Our findings highlight the need for targeted, context-sensitive solutions by analysing issues entrenched in their lifestyle and culture, as well as the broader healthcare challenges confronting the entire nation. The highlighted gaps in awareness, combined with access barriers to healthcare, need the development of creative techniques that bridge informational divides, facilitate closeness to treatment, and provide door-to-door services. Finally, our research contributes to a more nuanced knowledge of healthcare disparities and vaccination practises among nomadic tribes, allowing for the development of evidence-based policies that value cultural variety while striving for equitable health outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AGMN and EG; methodology, AGMN, GSW, and EG; software, GSW; validation, AGMN, GSW, KNF, CW, and EG; formal analysis, GSW and KNF; investigation, AGMN, CW, and EG; resources, CW; data curation, GSW; writing—original draft preparation, AGMN, GSW, KNF, and EG; writing—review and editing, AGMN and KNF; visualization, KNF; supervision, AGMN; project administration, AGMN, GSW, KNF, CW, and EG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive direct funding. However, it was conducted as part of the operational activities of the Enhanced Nomadic Community Engagement in Cameroon project, implemented by the Cameroon Red Cross with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was implemented as part of an operational public health project led by the Cameroon Red Cross, with the support of national health authorities. Authorization to conduct the study was obtained from the Regional Delegations of Public Health in the Adamawa, North, and Far North regions of Cameroon, as well as from local administrative and traditional authorities.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Prior to data collection, authorization was obtained from community leaders after the purpose and objectives of the project were thoroughly explained to them. Given the low literacy levels among participants and field constraints, written consent was not feasible. Participation was entirely voluntary, and individuals were free to decline or withdraw at any time during the interview process.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Requests can be directed to Dr. Aimé Mbonda at aimembonda450@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all those who contributed to the successful implementation of the project Enhanced Nomadic Community Engagement in Cameroon. Special thanks are extended to the staff and volunteers of the Cameroon Red Cross for their invaluable support in data collection and field coordination. The authors also express their appreciation to the national authorities who authorized, validated, and supported this work at various administrative and health system levels.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Despois, J. Nomades et nomadisme au Sahara. Ann Géographie. Persée - Portail des revues scientifiques en SHS 1964, 73, 494-495. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves MB et I. “Qu’est-ce qu’être nomade ?” [Internet]. ArchéOrient - Le Blog. 2021 [cité 7 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: https://archeorient.hypotheses.org/16742.

- Bank, A.D. Nigeria : la BAD appuie l’intégration des nomades dans le système scolaire [Internet]. Banque africaine de développement - Faire la différence. African Development Bank Group; 2019 [cité 7 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: https://www.afdb.org/fr/projects-and-operations/selected-projects/afdb-project-integrates-nomadic-peoples-into-mainstream-education-in-nigeria-79.

- Bernus E, Centlivres-Demont M. Problèmes actuels des pasteurs nomades.

- de Bruijn M, van Oostrum K, Obono O, Oumarou A, Boureima D. Mobilités nouvelles et insécurités dans les sociétés nomades Fulbé (peules) : Etude de plusieurs pays en Afrique Centrale de l’ouest (Niger-Nigeria).

- Schelling E, Wyss K, Diguimbaye C, Béchir M, Taleb MO, Bonfoh B, et al. Towards Integrated and Adapted Health Services for Nomadic Pastoralists and their Animals: A North–South Partnership. Handb Transdiscipl Res. 1 janv 2008;277.

- Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Waltner-Toews D, A. Whittaker M, Tanner M. One Health, une seule santé [Internet]. éditions Quae; 2020 [cité 7 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: https://www.quae-open.com/produit/151/9782759230976/one-health-une-seule-sante.

- Gammino, V.M.; Diaz, M.R.; Pallas, S.W.; Greenleaf, A.R.; Kurnit, M.R. Health services uptake among nomadic pastoralist populations in Africa: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. Public Library of Science 2020, 14, e0008474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Objectif de Développement Durable - Santé et Bien-Être pour tous [Internet]. Développement durable. [cité 7 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/fr/health/.

- World Health Organization. Rapport sur la santé dans le monde: 2005: donnons sa chance à chaque mère et à chaque enfant [Internet]. Organisation mondiale de la Santé; 2005 [cité 7 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43132.

- Sangaré, M.B. Accès aux Soins de Santé des Communautés en Milieu Nomade, Cas des Communes de Ber et Gossi à Tombouctou au Mali". Université des Sciences, des Techniques et des Technologies de Bamako; 2012 [cité 7 mars 2023]; Disponible sur: https://www.bibliosante.ml/handle/123456789/1523.

- Seli, D. Les barrières à la demande de service de vaccination chez les populations nomades de Danamadji, Tchad. ASC Work Pap Ser [Internet]. African Studies Centre Leiden (ASCL); 2017 [cité 2 mars 2023]; Disponible sur: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/51982.

- PEOPLE OF AFRICA - The Diversity of African People | African Race | Real Africa [Internet]. [cité 11 juill 2023]. Disponible sur: https://www.africanholocaust.net/peopleofafrica.htm#w.

- CAMEROUN - Troisième Enquête Camerounaise auprès des Ménages (2007) [Internet]. [cité 11 juill 2023]. Disponible sur: http://nada.stat.cm/index.php/catalog/18.

- Owoundi, JP. Poids des Dépenses de Santé sur le Revenu des Ménages au Cameroun.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).