Background

Urbanization and population growth have led to increased solid waste generation in cities globally, creating significant public health and environmental challenges [

1,

2]. In developing countries, municipal authorities are often overwhelmed by the volume and complexity of waste streams, lacking both the financial and logistical capacity to manage solid waste effectively [

3,

4]. In Uganda, solid waste collection coverage remains below 50% in most municipalities, and uncollected waste contributes to flooding, vector proliferation, and general environmental degradation [

5,

6].

Public Private Partnerships have emerged as a governance tool to improve service delivery by leveraging private sector efficiency, technology, and capital investment [

7,

8]. PPPs in solid waste management involve contractual agreements where the private sector assumes responsibility for some or all waste management functions, often with performance-based remuneration [

9,

10]. Empirical evidence from cities in Asia, Europe, and Africa has shown that PPPs can lead to better service coverage, improved operational efficiency, and cost reduction [

11,

12,

13]. However, the success of PPPs is contingent upon community engagement and acceptance. Community knowledge and attitudes significantly influence the uptake and sustainability of PPP-based services [

14,

15]. Studies in Ghana, Nigeria, and Tanzania have shown that residents with limited knowledge of how PPPs function are less likely to support such initiatives, especially when financial contributions are required [

16,

17,

18]. Furthermore, skepticism towards private operators, fears of job losses in the public sector, and concerns over rising user fees often fuel community resistance [

19,

20].

In Uganda, the integration of PPPs in waste management is still in its infancy. Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) has piloted PPP models with varied success, but outside of Kampala, few municipalities have adopted this model comprehensively [

5]. Jinja Municipality, a key industrial and commercial hub, generates substantial quantities of waste but has struggled to manage them effectively due to constrained municipal capacity and limited budgetary allocations. Despite being earmarked for potential PPP adoption, no comprehensive studies have examined the community’s readiness for this transition. Understanding community perceptions, knowledge, and willingness to engage with PPPs is essential to inform policy design and implementation. Without community buy-in, even well-funded and technically sound PPP projects may fail to deliver sustainable results [

21,

22]. This study therefore seeks to fill a critical knowledge gap by exploring the community knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to accept the PPP approach in Jinja Municipality.

Methods

Study Design. This study employed a cross-sectional design integrating both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The mixed-methods approach enabled triangulation of findings to gain comprehensive insights into community knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to participate in PPP for solid waste management.

Study Setting. The study was conducted in Jinja Municipality, located in Eastern Uganda. The municipality comprises three administrative divisions: Jinja Central, Walukuba-Masese, and Mpumudde-Kimaka. It is a major industrial and commercial hub, with diverse socio-economic activities contributing to significant solid waste generation.

Study Population. The target population included adult residents (aged 18 years and above) who lived or operated businesses within Jinja Municipality. Key informants were drawn from municipal officials responsible for environmental health and solid waste management.

Eligibility Criteria. Inclusion criteria: Adult residents or workers in Jinja Municipality (aged 18+), residing in the area for more than one month, and consenting to participate.

Exclusion criteria: Individuals under the influence of substances during data collection or those unable to provide informed consent.

Sample Size Determination. The sample size for the quantitative component was calculated using the Leslie Kish formula, assuming a 50% prevalence of PPP awareness, a 95% confidence interval, and a 6% margin of error. This yielded a minimum sample size of 267. Additionally, 10 key informants were purposively selected for qualitative interviews.

Sampling Procedure. A multistage sampling strategy was employed. First, parishes within each division were selected using simple random sampling. Villages were subsequently selected within the parishes. Households and businesses were chosen using systematic random sampling (every 5th unit), with one eligible respondent interviewed per unit. For qualitative interviews, purposive sampling identified individuals with direct involvement in waste management policy and operations.

Data Collection Tools and Procedures. Quantitative data were collected using pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaires translated into Lusoga for better comprehension. These included both open- and close-ended questions covering socio-demographics, knowledge of PPP, attitudes, and willingness to engage in the PPP model.

Qualitative data were collected through key informant interviews using an interview guide. Interviews were conducted in English or Lusoga, recorded, and later transcribed for analysis.

Quality Control. Research assistants were trained in data collection, ethical conduct, and use of tools. Pre-testing of tools was conducted in a non-study area, and daily reviews of completed questionnaires were undertaken to ensure consistency and completeness.

Data Management and Analysis. Quantitative data were entered using EpiData and analysed using STATA version 14. Univariate analysis described frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, and means (±SD) for continuous variables. Knowledge was scored based on responses to six items and categorized as no, low, fair, or good knowledge. Attitudes were assessed using a Likert scale, categorized as positive or negative. The qualitative data were analyzed thematically. Transcripts were coded manually, and themes were derived in line with the study objectives. Triangulation enhanced the reliability of findings.

Ethical Considerations. Permission was sought from Makerere University School of Public Health and Jinja Municipal Council. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured, and participation was voluntary.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

A total of 267 respondents participated in the study, yielding a 100% response rate. The mean age was 34.7 years (SD ± 9.8). More than half were female (53.6%). Regarding education, 40.5% had completed primary education, and 23.2% had attained tertiary education. Business was the most common occupation (54.3%), while civil servants made up 7.1% of the sample. The majority (61.4%) were married, and most respondents had resided in Jinja Municipality for over one year (87.3%).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

| Variable |

Frequency (N=267) |

Percentages (100%) |

| Sex |

|

|

| Male |

124 |

46.4 |

| Female |

143 |

53.6 |

| Age category |

|

| 18-20 |

9 |

3.4 |

| 21-29 |

95 |

35.6 |

| 30-39 |

85 |

31.8 |

| 40-49 |

41 |

15.4 |

| 50 and above |

37 |

13.9 |

| Education level |

|

| Never attended school |

4 |

1.5 |

| Primary |

108 |

40.5 |

| Secondary |

93 |

34.8 |

| Tertiary |

62 |

23.2 |

| Religion |

|

|

| Catholic |

79 |

29.6 |

| Protestant |

93 |

34.8 |

| Pentecostal |

29 |

10.9 |

| Muslim |

66 |

24.7 |

| Marital status |

|

| Single |

79 |

29.6 |

| Married |

164 |

61.4 |

| Widowed |

8 |

3.0 |

| Separated/Divorced |

16 |

6.0 |

| Occupation |

|

| Peasant |

28 |

10.5 |

| Business man/woman |

145 |

54.3 |

| Civil servant |

19 |

7.1 |

| Others |

75 |

28.1 |

Waste Generation Characteristics

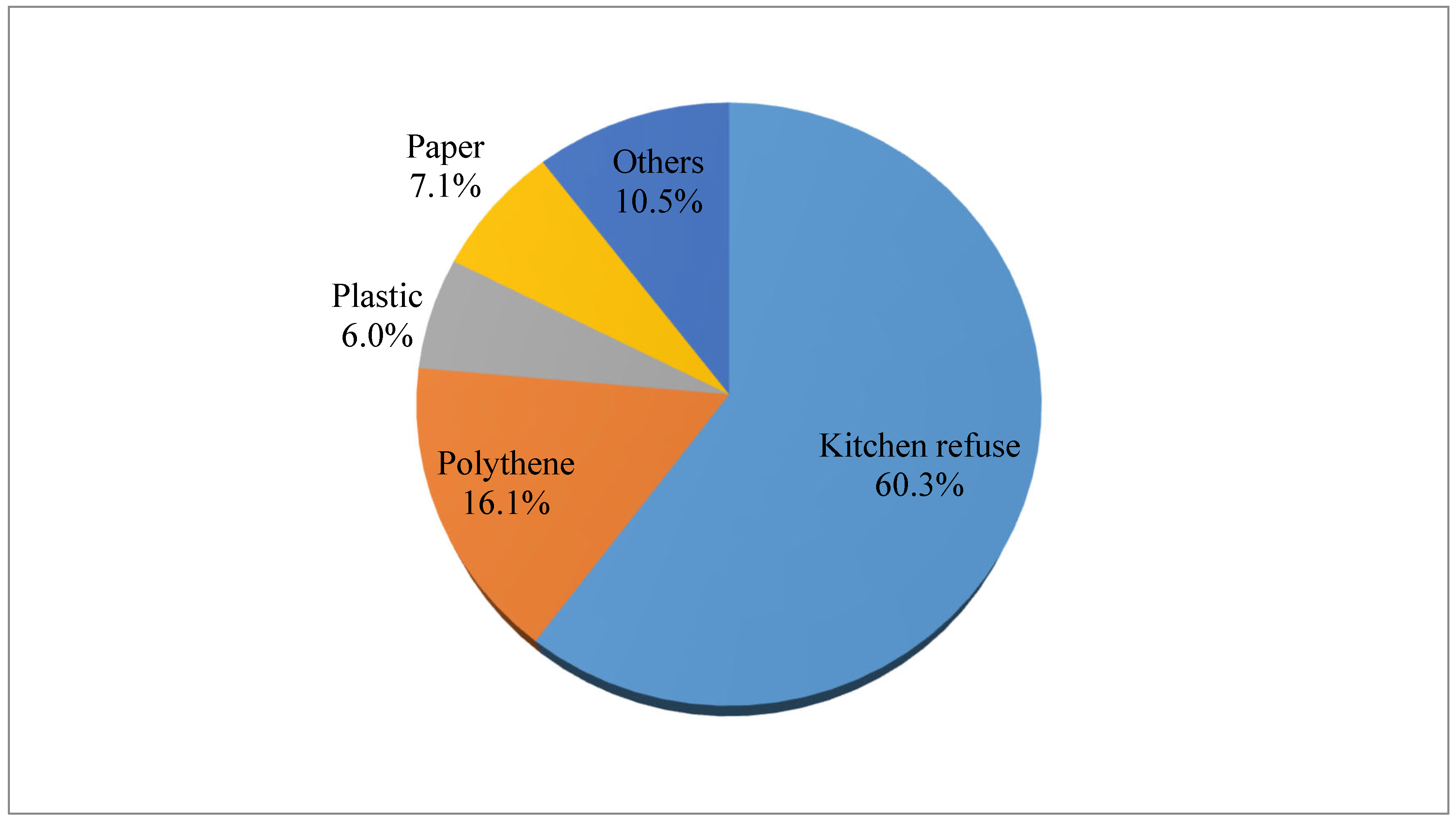

Most respondents (60.3%) reported decomposable waste as the main type generated, followed by polythene (16.1%) and plastics (6.0%). Industrial and medical waste was also reported, particularly among respondents near commercial and health facilities.

Figure 1.

Main category of waste generated by respondents.

Figure 1.

Main category of waste generated by respondents.

Knowledge of Public Private Partnerships (PPP) Only 42.3% of respondents had heard of the PPP approach. Knowledge was scored across six dimensions, including understanding of services, partners, advantages, and disadvantages. A majority (60.7%) had no knowledge, while 7.1% demonstrated good knowledge.

Table 2.

General knowledge levels on PPP among respondents.

Table 2.

General knowledge levels on PPP among respondents.

| Variable |

Willingness to take up PPP N (%) |

Total |

| No (n=167) |

Yes (n=99) |

267 |

| Knowledge on services under which PPP can be applied |

|

|

|

| Know less or equal to one program |

152(90.5) |

85(85.9) |

237 |

| Knows at least two programs |

16(9.5) |

14(14.1) |

30 |

| Knowledge about partners involved in PPP approach |

|

|

|

| Knows at least two |

24(14.3) |

29(29.3) |

53 |

| Less or equal to one partner |

144(85.7) |

70(70.7) |

214 |

| Knowledge about advantages of PPP approach |

|

|

|

| Wrong or no answer |

123(73.2) |

43(43.4) |

166 |

| Mentions at least one |

45(26.8) |

56(56.6) |

101 |

| Knowledge about the disadvantages of PPP approach |

|

|

|

| Wrong or no answer |

164(97.6) |

97(98.0) |

161 |

| Mentions at least one |

4(2.4) |

2(2.0) |

06 |

Attitudes Toward PPP Attitudes were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, later categorized into positive or negative. Most respondents (60.7%) exhibited negative attitudes toward the PPP model, expressing skepticism about service quality, cost, and community involvement.

Table 3.

Overall attitude scores of respondents.

Table 3.

Overall attitude scores of respondents.

| Variable (respondents attitudes) |

Willingness to take up PPP N (%) |

Total |

| No (n=167) |

Yes (n=99) |

267 |

| PPP ensures more regular cleanups than public sector |

|

|

|

| Agree |

44(26.2) |

22(22.2) |

66 |

| Disagree |

124(73.8) |

77(77.8) |

201 |

| PPP is a way of job creation in the community |

|

|

|

| Agree |

49(29.2) |

19(19.2) |

68 |

| Disagree |

119(70.8) |

80(80.8) |

199 |

| PPP is less costly compared to public sector |

|

|

|

| Agree |

94(56.0) |

56(56.6) |

150 |

| Disagree |

74(44.0) |

43(43.4) |

117 |

| With PPP approach, the town will look cleaner with no solid waste |

|

|

|

| Agree |

38(22.6) |

18(18.2) |

46 |

| Disagree |

130(77.4) |

81(81.8) |

221 |

| Solid waste can be managed by private sector without government aid |

|

|

|

| Agree |

60(35.7) |

51(51.5) |

111 |

| Disagree |

108(64.3) |

48(48.5) |

156 |

| PPP brigs about full community participation |

|

|

|

| Agree |

85(50.6) |

48(48.5) |

133 |

| Disagree |

83(49.4) |

51(51.5) |

134 |

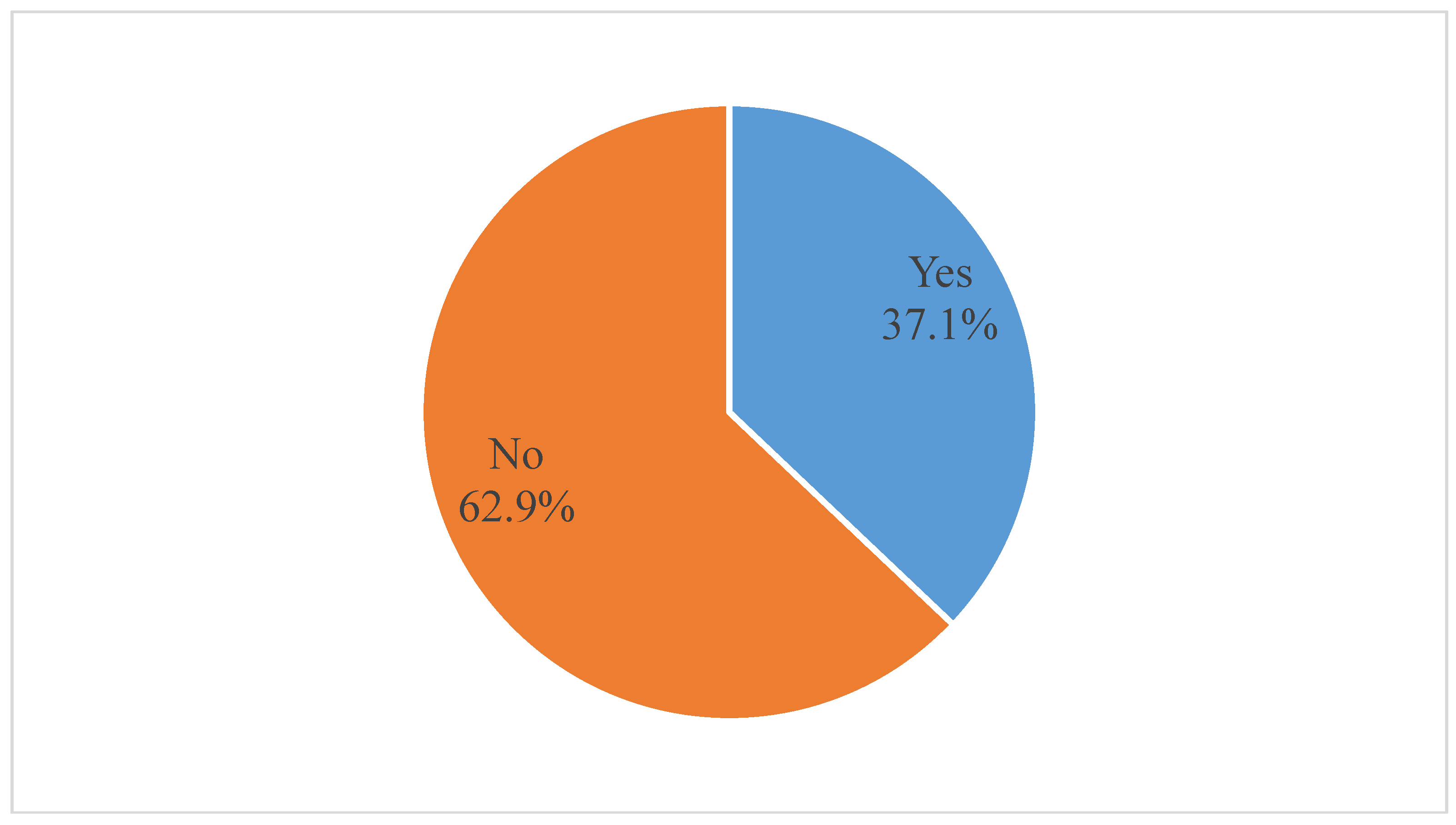

Willingness to Accept PPP

Only 99 respondents (37.1%) expressed willingness to accept the PPP model for solid waste management. Of these, 64.6% were willing to pay a fee, with most indicating a preferred range of 100–1000 UGX monthly.

Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents willing to accept the PPP approach.

Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents willing to accept the PPP approach.

Qualitative Findings

Key informants highlighted low community awareness and mistrust toward private waste handlers. However, they acknowledged the potential benefits of PPP including increased efficiency, employment creation, and cost-sharing. “Community attitudes are often negative, especially regarding payment. But if sensitized, many would see the benefits.” (Health Inspector, Jinja Municipality). These findings corroborate the quantitative data, emphasizing the importance of public engagement and transparent communication in PPP adoption.

Discussion

This study explored community knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to accept the Public Private Partnership approach for solid waste management in Jinja Municipality, Uganda. The results highlight significant knowledge gaps, prevailing negative attitudes, and moderate levels of willingness to participate in PPP-led waste services. The majority of respondents demonstrated limited knowledge about PPPs. Over 60% had never heard of the concept, and less than 10% showed good understanding. These findings align with prior studies in low- and middle-income countries where community awareness of governance mechanisms such as PPPs remains low [

10,

14]. The situation in Jinja is compounded by the lack of existing PPP implementation in the area, making it difficult for residents to conceptualize the operational, financial, and governance aspects of such models [

18,

23]. Knowledge deficiencies have direct implications for public acceptance. As shown in similar urban studies in Lagos and Dar es Salaam, communities with low exposure to PPP frameworks often view them with suspicion [

13,

15]. Misinformation about privatization, fear of increased user costs, and concerns about reduced government responsibility contribute to these attitudes [

12,

19]. The low knowledge levels in this study may also stem from the relatively low education attainment among respondents, where the majority had only completed primary education.

Community attitudes toward the PPP model were largely negative, with 60.7% of participants expressing scepticism or resistance. This reflects concerns over affordability, trust in private sector delivery, and doubts about service improvements. Such negative perceptions are consistent with global literature on PPP implementation barriers [

20]. However, the results also suggest an opportunity for change, as over one-third of the community expressed willingness to participate if properly informed and if the services were affordable. The qualitative data reinforce the quantitative findings. Key informants acknowledged the community's general lack of information but were optimistic about the potential for behaviour change through public sensitization. Similar outcomes have been observed where community awareness campaigns, stakeholder dialogues, and participatory planning helped build trust in PPP initiatives [

22,

24].

Willingness to pay for services, while modest, is a promising signal. Most respondents who were open to PPP-supported waste management preferred to contribute between 100 and 1,000 UGX per month. These values, though low, demonstrate that communities are not entirely opposed to payment-based waste services, especially when affordability is ensured [

16,

17]. This supports the polluter-pays principle and suggests that small fees if transparently managed could support sustainable municipal services. The general observation from the data supports previous findings that socio-demographic factors such as education and occupation influence PPP acceptability. Tailored communication strategies, particularly targeting those with lower education and informal occupations, would therefore be critical in scaling support [

14,

18].

In light of these findings, municipalities like Jinja should consider phased implementation of PPPs, starting with pilot programs in select divisions. Demonstrating the effectiveness of the model through cleaner environments and improved service delivery could help win public trust. Furthermore, involving local leaders and community-based organizations can create a sense of ownership and accountability, enhancing program sustainability [

7,

8]. This study underscores the importance of community engagement in PPP planning and deployment. For Jinja Municipality, success will depend on addressing knowledge gaps, improving public attitudes through education, and ensuring affordability and transparency in service provision. If these elements are integrated, PPP can serve as a transformative model for urban waste management in Uganda.

Study Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study was its mixed-methods design, which allowed for a comprehensive assessment of community perspectives through both quantitative surveys and qualitative key informant interviews. The inclusion of a relatively large and diverse sample from multiple divisions within Jinja Municipality enhances the representativeness of the findings. Furthermore, the use of local languages during data collection helped improve respondent understanding and response accuracy. However, the study also has limitations. As a cross-sectional design, it captures community perceptions at one point in time and cannot account for changes over time or establish causality. The reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for response bias, particularly concerning attitudes and willingness to pay. Despite these limitations, the findings provide valuable baseline information to guide policy and program development for PPP in urban waste management.

Conclusions

This study provides vital insights into the community's readiness for Public Private Partnership implementation in solid waste management within Jinja Municipality. The findings revealed low levels of knowledge and largely negative attitudes toward PPPs among residents, with limited awareness of how such models operate and what benefits they might offer. Despite these barriers, a significant proportion of the population expressed a willingness to engage with the PPP model, especially when services are clearly communicated and affordability is assured. The results affirm that the success of PPP initiatives is closely tied to public understanding and trust. Addressing informational gaps and misconceptions, fostering transparency, and encouraging stakeholder participation will be central to the effective roll-out of any PPP model in this context. When well-designed and community-centered, PPPs have the potential to significantly enhance solid waste service delivery, promote sustainability, and contribute to improved public health and environmental outcomes in Jinja and beyond.

Recommendations

To facilitate successful adoption of the Public Private Partnership model for solid waste management in Jinja Municipality, it is essential to prioritize comprehensive community sensitization campaigns that explain the benefits and responsibilities of PPPs in locally understandable terms. Active stakeholder engagement, including local leaders and civil society, should be integral to the planning and decision-making processes to foster community ownership and trust. The municipality should initiate pilot projects in selected areas to demonstrate effectiveness, accompanied by affordable, context-sensitive payment models. Transparent monitoring systems must be established to ensure accountability and encourage feedback. Strengthening local institutional capacity and conducting ongoing research will be key to refining and sustaining PPP efforts over the long term.

References

- Abarca Guerrero, L., G. Maas, and W. Hogland, Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. 2013.

- Pires, A., G. Martinho, and N.-B. Chang, Solid waste management in European countries: A review of systems analysis techniques. Journal of environmental management, 2011. 92(4): p. 1033-1050.

- Karak, T., B.R. M., and P. and Bhattacharyya, Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Composition, and Management: The World Scenario. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2012. 42(15): p. 1509-1630.

- Kumar, S., et al., Assessment of the status of municipal solid waste management in metro cities, state capitals, class I cities, and class II towns in India: An insight. Waste management, 2009. 29(2): p. 883-895.

- Okot-Okumu, J. and R. Nyenje, Municipal solid waste management under decentralisation in Uganda. Habitat international, 2011. 35(4): p. 537-543.

- UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme, 2002. Solid Waste Management: Assessment of the Current Waste Management System. Osaka/Shiga: UNEP IETC. 2002. Volume 1.

- Klijn, E.-H. and G.R. Teisman, Governing public-private partnerships: Analysing and managing the processes and institutional characteristics of public-private partnerships, in Public-private partnerships. 2000, Routledge. p. 102-120.

- Ahmed, S.A. and M. Ali, Partnerships for solid waste management in developing countries: linking theories to realities. Habitat international, 2004. 28(3): p. 467-479.

- Leigland, J., Public-private partnerships in developing countries: The emerging evidence-based critique. The World Bank Research Observer, 2018. 33(1): p. 103-134.

- Hodge, G.A. and C. Greve, The challenge of public-private partnerships: Learning from international experience. 2005: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- McDavid, J.C., Solid-waste contracting-out, competition, and bidding practices among Canadian local governments. Canadian Public Administration, 2001. 44(1): p. 1-25.

- Jamali, D., A study of customer satisfaction in the context of a public private partnership. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 2007. 24(4): p. 370-385.

- Aliu, I.R., O.E. Adeyemi, and A. Adebayo, Municipal household solid waste collection strategies in an African megacity: Analysis of public private partnership performance in Lagos. Waste Management & Research, 2014. 32(9_suppl): p. 67-78.

- Godfrey, L., et al., Solid Waste Management in. Regional development in Africa, 2020: p. 235.

- Kassim, S.M. and M. Ali, Solid waste collection by the private sector: Households’ perspective—Findings from a study in Dar es Salaam city, Tanzania. Habitat international, 2006. 30(4): p. 769-780.

- Rahji, M. and E.O. Oloruntoba, Determinants of households’ willingness-to-pay for private solid waste management services in Ibadan, Nigeria. Waste management & research, 2009. 27(10): p. 961-965.

- Ezebilo, E. and E. Animasaun, Households’ perceptions of private sector municipal solid waste management services: a binary choice analysis. International Journal of Environmental Science & Technology, 2011. 8: p. 677-686.

- Oteng-Ababio, M., Private sector involvement in solid waste management in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area in Ghana. Waste Management & Research, 2010. 28(4): p. 322-329.

- Bloomfield, P., The challenging business of long-term public–private partnerships: Reflections on local experience. Public Administration Review, 2006. 66(3): p. 400-411.

- Farvacque-Vitkovic, C.D. and M. Kopanyi, Municipal finances: A handbook for local governments. 2014: World Bank Publications.

- Damghani, A.M., et al., Municipal solid waste management in Tehran: Current practices, opportunities and challenges. Waste management, 2008. 28(5): p. 929-934.

- Asase, M., et al., Comparison of municipal solid waste management systems in Canada and Ghana: A case study of the cities of London, Ontario, and Kumasi, Ghana. Waste management, 2009. 29(10): p. 2779-2786.

- Lohri, C.R., E.J. Camenzind, and C. Zurbrügg, Financial sustainability in municipal solid waste management–Costs and revenues in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Waste management, 2014. 34(2): p. 542-552.

- Baud, I., et al., Quality of life and alliances in solid waste management: contributions to urban sustainable development. Cities, 2001. 18(1): p. 3-12.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).