1. Introduction

The association between the gut microbiota composition and clinical outcomes of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as inhibitors targeting cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), programmed death 1 (PD-1), and its ligand (PD-L1), was demonstrated in various cancer cohorts [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Although the mechanism of gut microbiota-mediated regulation of response to ICIs is not fully understood, the gut microbiota is known to exert a critical impact on local and systemic immunity. It constantly interacts with other components of the intestinal barrier, i.e., the mucus layer, epithelial cells, and lamina propria – a connective tissue containing the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (the largest component of the immune system) [

6,

7]. In normal physiological conditions, this interaction provides a homeostatic relationship between the intestinal microorganisms and the host. However, the loss of barrier integrity may lead to uncontrolled luminal antigen translocation to the host internal environment and trigger local and systemic inflammation, which, in cancer patients, may affect immune responses at the tumor site and the clinical outcomes of the ICIs.

Despite growing evidence suggesting an involvement of the gut microbiota in shaping immune response in cancer patients undergoing ICI therapy, the intestinal barrier state and mucosal immune system activity in those patients are poorly explored. To date, a limited number of studies have reported the differences in the intestinal barrier function between patients with favorable and unfavorable outcomes of ICIs. For instance, Ouaknine Krief et al. (2019) found that high baseline citrulline level (≥20 μM) in blood plasma, which reflects proper intestinal epithelial cell function, correlated with better response and clinical benefit to the ICI therapy and longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving the anti-PD-1 therapy [

8]. Another study revealed a higher abundance of inflammatory cells, such as dendritic cells, monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils, in fecal samples of progressors than non-progressors in a cohort of melanoma patients receiving the anti-PD-1 antibodies, which implies increased activation of inflammatory immune responses within the intestinal mucosa in the subgroup with poor clinical outcomes [

2].

The primary goal of the present study was to evaluate the intestinal barrier functionality in advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy and analyze its association with the clinical outcomes of immunotherapy. Therefore, the concentration of zonulin, calprotectin, and secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in stool samples collected from those patients before the start (at baseline) and during treatment. Zonulin is considered a biomarker of intestinal permeability. It is known as a physiological modulator of intercellular tight junctions (TJs) that are localized near the apical surface of adjacent epithelial cells and control the passage of luminal antigens via the paracellular pathway. Zonulin binding to a specific receptor on the surface of intestinal epithelium activates a cascade of biochemical events that induce TJ disassembly, followed by increased permeability (increased passage of luminal antigens) and activation of mucosal immunity. The zonulin pathway is part of a defensive mechanism that initiates immune responses against antigens to remove them from the microbial ecosystem. Therefore, it may play an important role in maintaining homeostasis in the intestinal mucosa. However, disruption of intestinal barrier integrity (reflected by increased zonulin levels) may also contribute to the development of various chronic inflammatory diseases [

9,

10,

11]. On the other hand, fecal calprotectin is a biomarker reflecting intestinal inflammation. It belongs to the family of calcium-binding proteins constitutively expressed in neutrophils and other cells that regulate inflammatory processes and exhibit antibacterial and antiproliferative activity. During intestinal inflammation, neutrophils are recruited to the intestinal mucosa, and their numbers positively correlate with the concentration of fecal calprotectin [

12]. Finally, fecal SIgA is regarded as a biomarker of intestinal immunity. It is the dominant Ig in the mucosal secretions and plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis in the intestinal mucosa. Firstly, it protects the intestinal epithelium against pathogens through the process known as ‘immune exclusion’. SIgA stimulates pathogen cross-linking and entrapment in the intestinal lumen, which facilitates their clearance from the gastrointestinal tract through peristalsis. Secondly, SIgA provides homeostasis in the intestinal mucosa through the interaction with commensal microbiota. On the one hand, SIgA coating of non-pathogenic species may prevent their invasion into the intestinal mucosa. On the other hand, it may promote intestinal colonization by commensal species by supporting their adhesion to the mucus layer or acting as a nutritional source [

13,

14]. Furthermore, SIgA was shown as a key component of the gut environment that shapes the oral tolerance to food proteins, potentially by preventing their translocation through the gut barrier [

15].

In the present study, ELISA results indicated that the baseline concentration of fecal SIgA was significantly higher in patients with favorable clinical outcomes than those with unfavorable ones. Moreover, the analyzed biomarkers were elevated in most of the patients (concerning the reference ranges [

9,

16,

17,

18]). High baseline concentrations of intestinal barrier state biomarkers significantly correlated with survival outcomes; in the cases of fecal zonulin and fecal SIgA, it was a positive correlation, while in the case of fecal calprotectin, a negative correlation. Taking into account that fecal SIgA level was associated with improved clinical outcomes in the study cohort, the fraction of stool microbiota coated with Igs was purified from the total stool microbiota, and bacterial composition of the Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction and total stool microbiota was characterized using V3-V4 region of 16SrRNA gene sequencing. It was found that the Ig-bound stool microbiota shared a substantial subset of genera with the total stool microbiota, however, at different abundances. Moreover, there were differences in the microbial profiles of the Ig-bound stool microbiota between patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes and their changes during treatment. Taken together, our findings suggest that the functionality of the intestinal barrier and immunity play a role in shaping the anti-cancer responses in advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy. Future studies that will provide a mechanistic insight into this aspect are warranted.

4. Discussion

Although the association between the gut microbiota composition and clinical outcomes of ICIs was demonstrated in various cohorts of cancer patients [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], the influence of the intestinal barrier functionality (that mutually interacts with the gut microbiota) on the immunotherapy efficacy has not been extensively studied so far. Therefore, in our study, the intestinal barrier state biomarkers, fecal zonulin, fecal calprotectin, and fecal SIgA, were quantified in advanced melanoma patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy, before the start and during treatment, to analyze their association with clinical outcomes. As a result, there were found no statistically significant differences in the intestinal barrier permeability and inflammation (reflected by the concentrations of fecal zonulin [

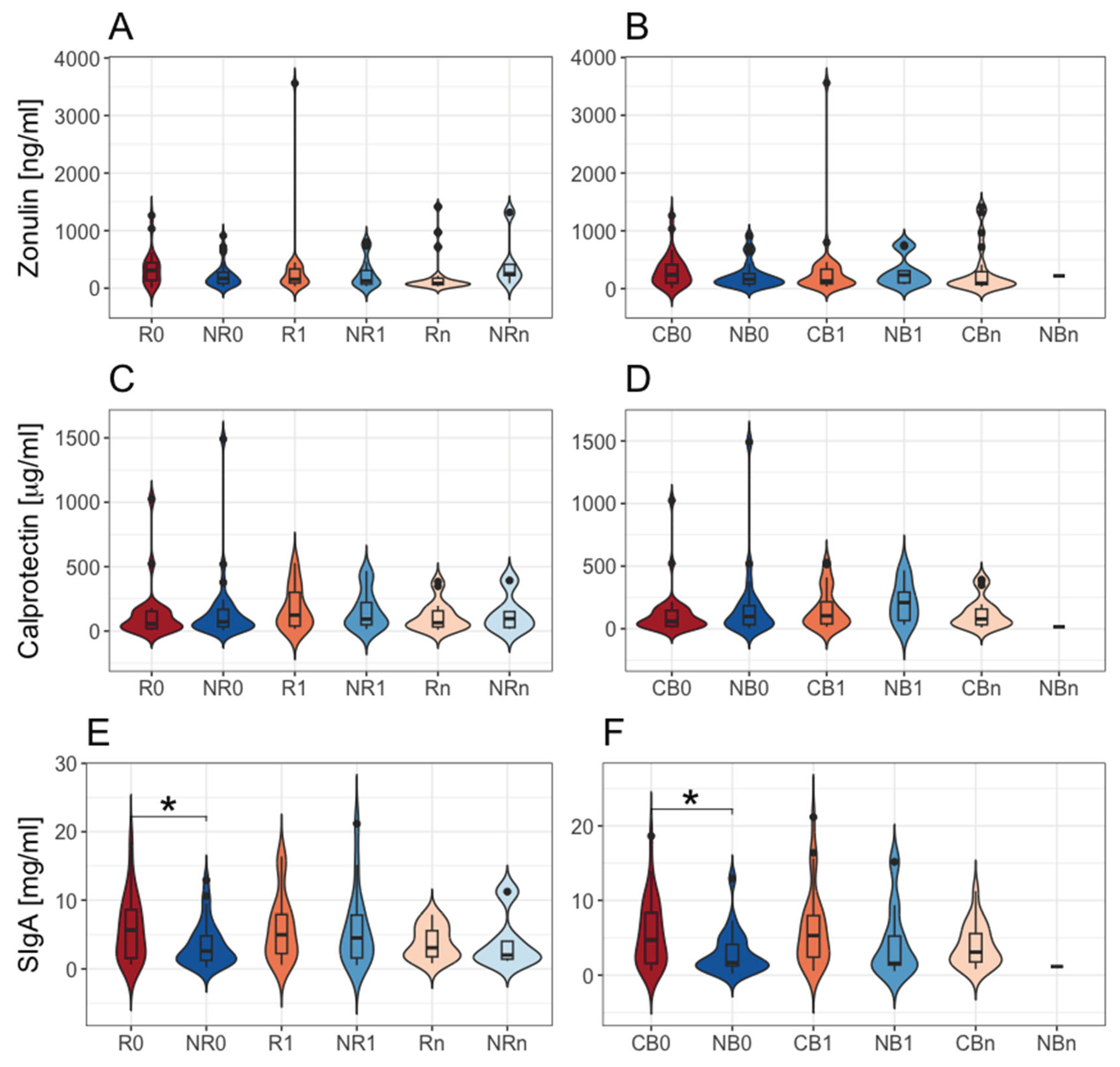

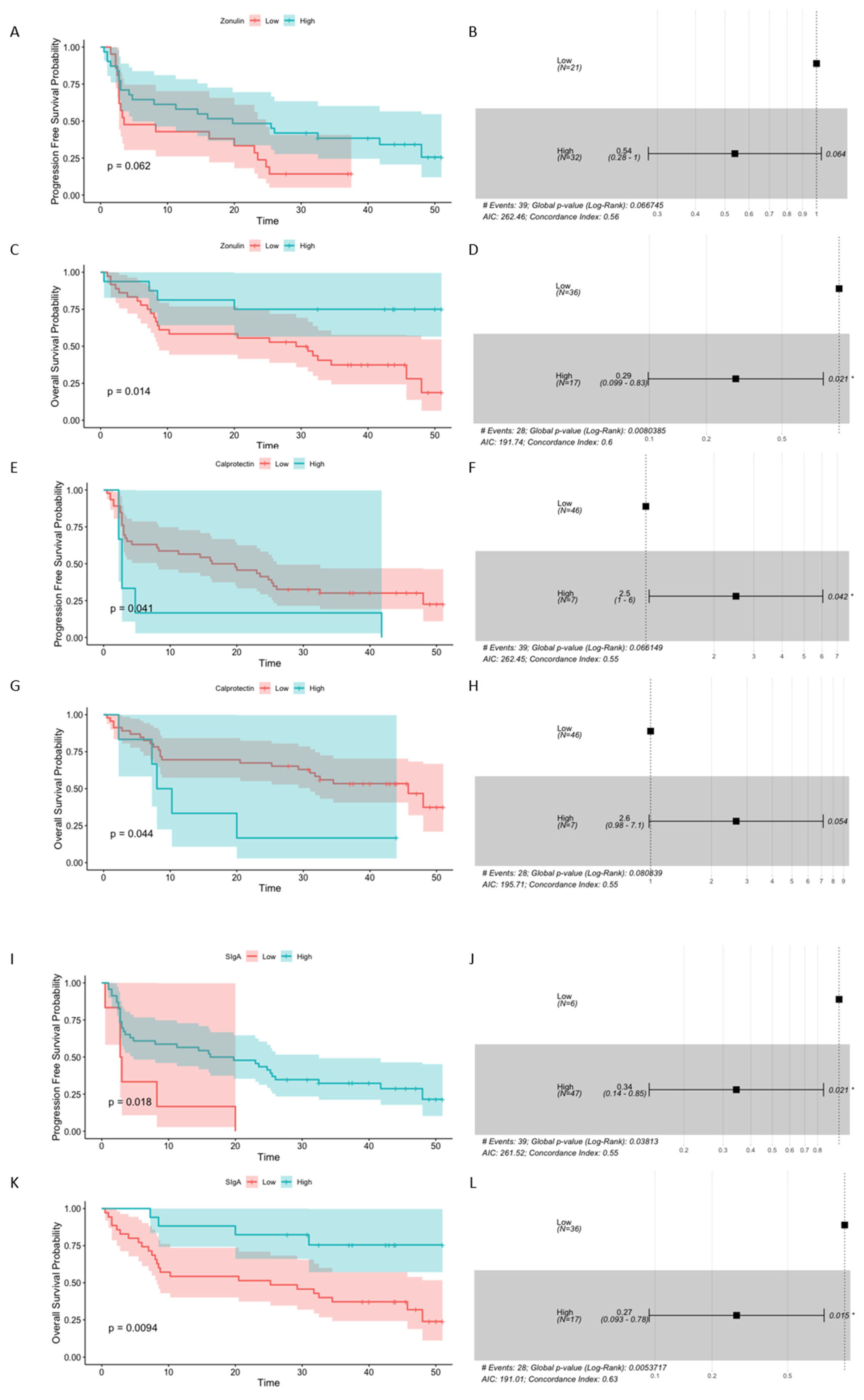

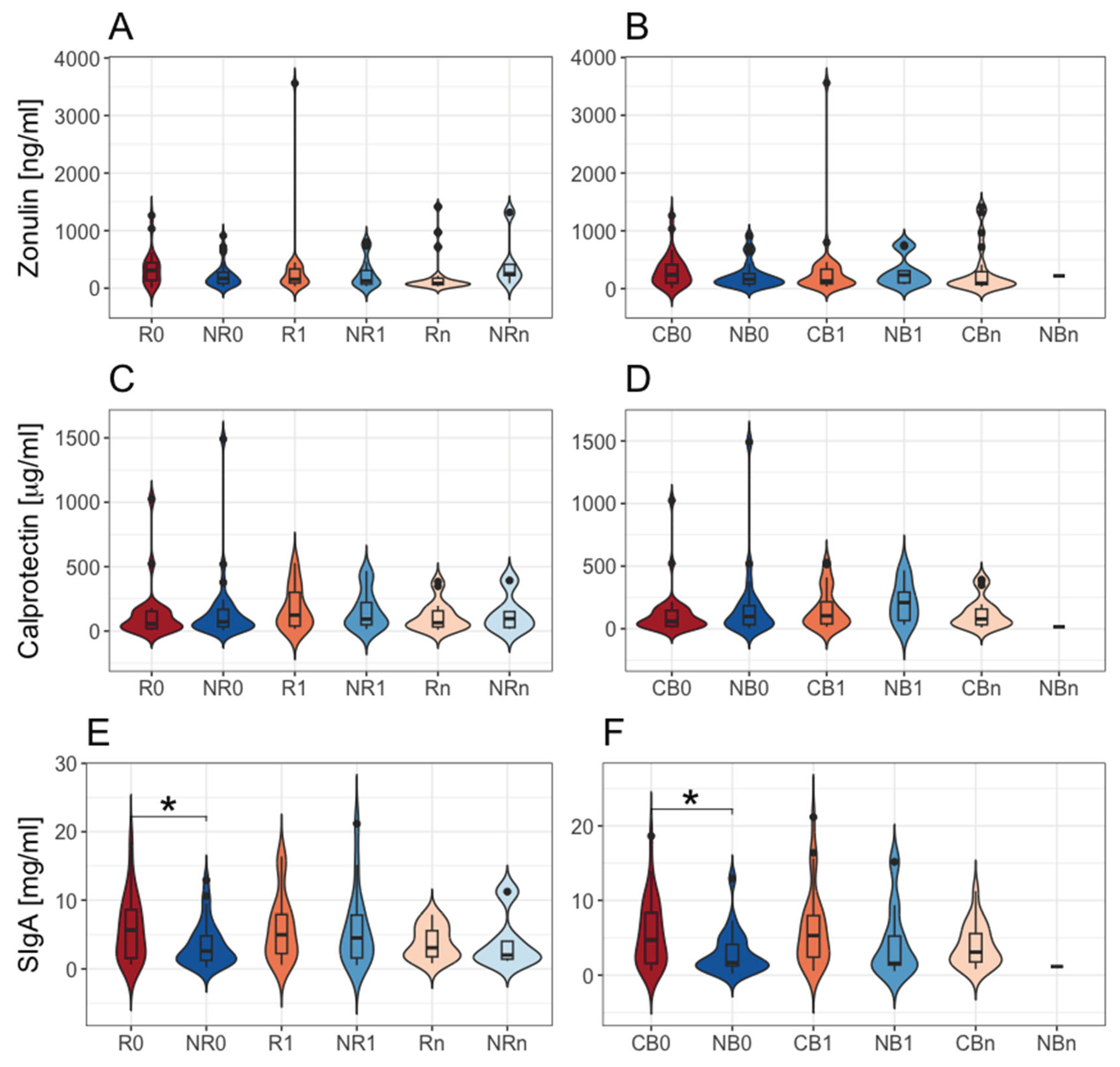

10] and calprotectin [

12], respectively) between patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes (

Figure 1A–D). However, the level of fecal SIgA at baseline was significantly higher in the R and CB subgroups as compared to the NR and NB subgroups, respectively (

Figure 1E and F), suggesting an association between intestinal immunity and response/clinical benefit from the anti-PD-1 therapy in the study cohort. Moreover, the investigated intestinal barrier state biomarkers were significantly associated with survival outcomes. In detail, high baseline concentration of fecal zonulin predicted longer OS, high baseline fecal SIgA level – longer PFS and OS, whereas high baseline concentration of calprotectin – shorter PFS and OS (

Figure 3). In line with our findings, other studies also reported some differences in the functioning of the intestinal barrier between cancer patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes of ICIs. For instance, it was shown that NSCLC patients with baseline plasma citrulline levels higher than 20 μM (reflecting properly functioning enterocytes) more frequently received clinical benefits from the anti-PD-1 therapy and had longer PFS and OS than those with lower citrulline levels [

8]. Moreover, in a cohort of melanoma patients receiving the anti-PD-1 therapy, patients with PD had an increased abundance of inflammatory cells in their fecal samples compared to non-progressors [

2]. Another study reported lower baseline fecal calprotectin levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who clinically benefited from the ICI therapy (anti-CTLA-4 and/or anti-PD-L1 therapy) in comparison to those with PD [

32]. Moreover, trends in the changes of fecal calprotectin levels during treatment in patients with HCC were comparable to those observed in the intestinal permeability biomarkers, i.e., serum zonulin and lipopolysaccharide binding protein (LBP), and opposite to those observed in

Akkermansia to

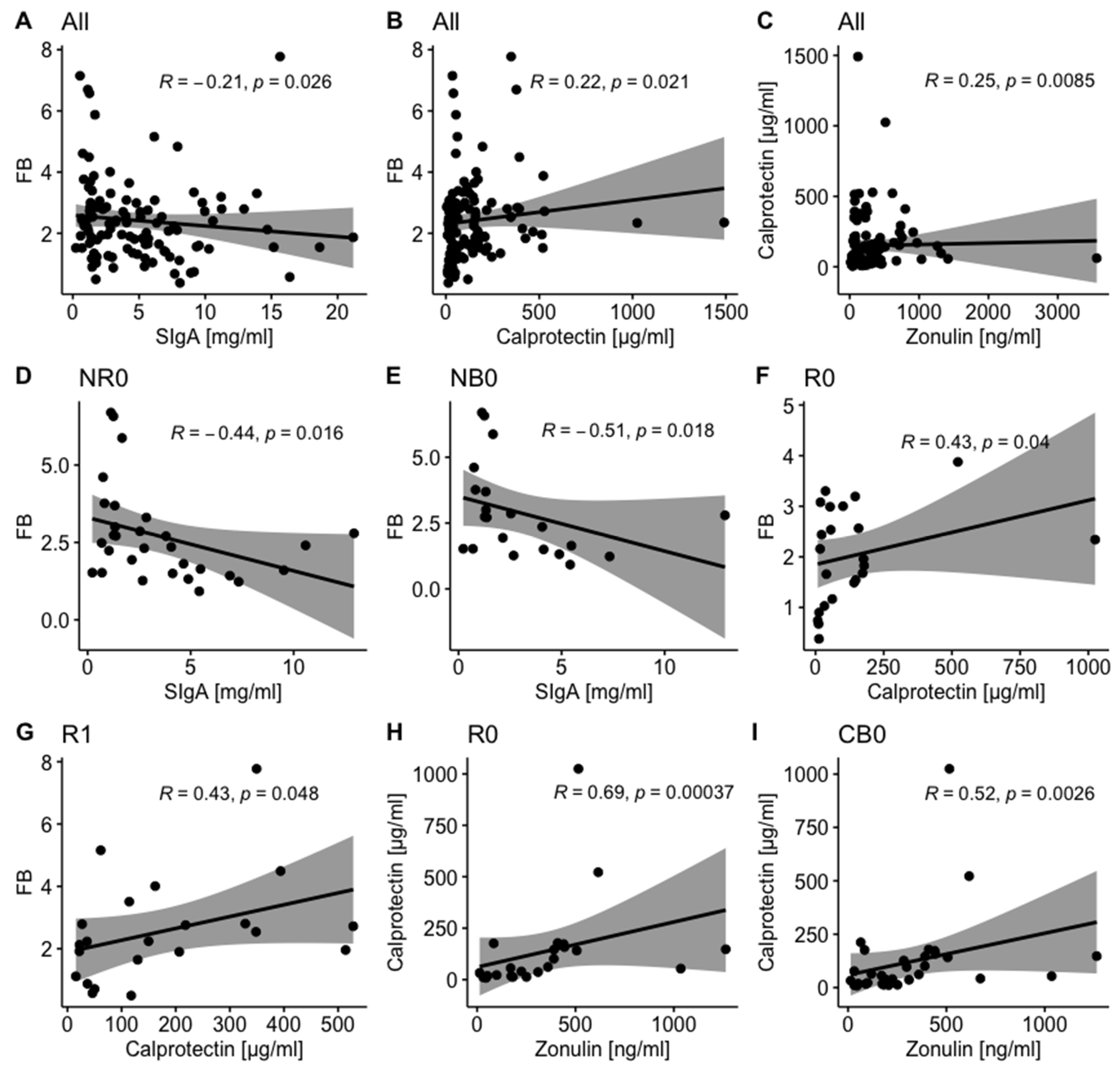

Enterobacteriaceae ratio and the gut microbiota alpha diversity. In our study, a positive correlation between fecal zonulin and fecal calprotectin levels was observed in all samples and patients with favorable clinical outcomes at baseline (

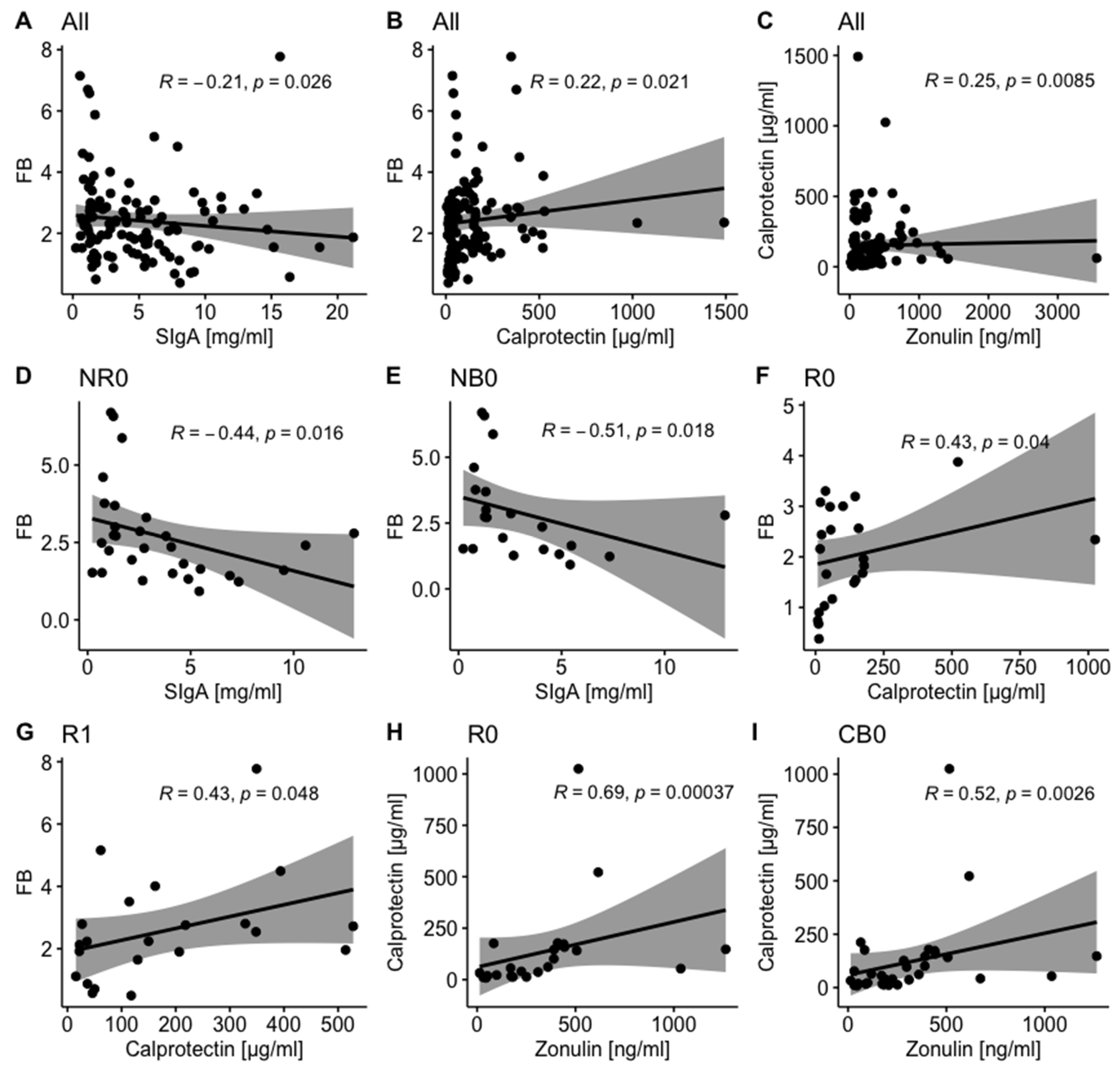

Figure 2C, H, and I). In line with our findings, Coutzac et al. (2020) found that serum zonulin correlated with serum inflammatory proteins, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) in metastatic melanoma patients undergoing anti-CTLA-4 therapy [

33]. In our cohort, fecal calprotectin also positively correlated with the F/B ratio in the total stool microbiota in all samples and the R subgroup at T

0 and T

1 (

Figure 2B, F, and G). The F/B ratio is considered a biomarker of intestinal homeostasis, and any disruptions in its value may reflect gut microbiota dysbiosis and have been reported in various diseases, such as obesity, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [

30,

31]. It is worth noting that the relative abundance of

Bacteroidota (formerly

Bacteroidetes,

Figure S1A) and

Bacteroidetes to

Firmicutes (B/F) ratio were increased in the baseline total stool microbiota of the R subgroup compared to the NR subgroup (as reported in our previous paper [

3]). These findings imply the link between the total stool microbiota enrichment in

Bacteroidota phylum members and lower intestinal inflammation and favorable clinical outcomes of anti-PD-1 therapy in the study cohort. In line with that, the association between decreased B/F ratio in the total stool microbiota and intestinal and systemic inflammation (reflected by fecal calprotectin and plasma C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels, respectively) was indicated in obese subjects [

34]. Consistently, several

Bacteroidota phylum members were found to possess anti-inflammatory and epithelium-reinforcing properties [

35]. On the other hand, the F/B ratio in the total stool microbiota was negatively associated with fecal SIgA in all samples and patients with unfavorable clinical outcomes at baseline (

Figure 2A, D, and E). A similar trend was observed in a study on a porcine model [

36]. Moreover, another study demonstrated that the

Bacteroides ovatus, a member of the

Bacteroidota phylum, elicited higher fecal SIgA production in mice than other analyzed species [

37]. Noteworthy, the concentration of fecal SIgA tended to be lower after monocolonization with

Bacillota,

Actinomycetota, or

Pseudomonadota phylum representatives compared to

Bacteroidota phylum members. These findings revealed that properly functioning intestinal immunity may reduce intestinal inflammation and provide homeostatic interaction between the gut microbiota and host. Overall, there were different trends in the correlation between analyzed biomarkers in patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes (

Figure 2), which implies activation of distinct mechanisms within the intestinal mucosa in those subgroups.

Collectively, our findings indicate that the intestinal barrier may affect treatment efficacy in cancer patients receiving ICIs, potentially through the interaction with the gut microbiota and mucosal immunity, and consequently modulate immune responses at the tumor site. The association between analysed intestinal barrier state indicators and survival outcomes reveals their potential as predictive/prognostic biomarkers in cancer patients undergoing ICI therapy. However, several aspects should be considered during the evaluation of biomarker clinical utility and the establishment of accurate cut-off points for patient stratification. Firstly, in the current study, the biomarker concentrations were elevated in most patients, and estimated biomarker cut-off levels that predicted improved or poor survival outcomes were also increased (from 2.7 to 4.2 times higher than upper limit of the normal range), regarding the reference range [

9,

16,

17], apart from the concentration of fecal SIgA predicting longer PFS, which was within normal limits [

16]. These results revealed disrupted intestinal barrier functionality in advanced cancer patients, implying that specific reference ranges should be established for such cohorts. Secondly, elevated concentrations of investigated biomarkers may not only be associated with tumors, but also with coexisting diseases, such as autoimmune, infective, or metabolic diseases [

10,

12,

38]. Thirdly, other factors may change the concentration of intestinal barrier state biomarkers, such as age [

9,

39], tumor stage [

38], and diet [

40,

41]. On the other hand, the intestinal barrier and immunity may become a therapeutic targets to improve clinical outcomes of ICIs in cancer patients. There are several potential interventions to modulate their functioning, e.g., through pharmaceutical intervention, prebiotics and probiotics, diet and supplements, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) [

42]. For instance, Renga et al. (2022), in a study on a murine model of melanoma, demonstrated that indole-3-carboxaldehyde (known to contribute to the maintenance of the intestinal barrier homeostasis) prevented intestinal damage associated with ICI-induced colitis and simultaneously did not interfere with the anticancer activity of anti-CTLA-4 therapy [

43].

As baseline concentration of fecal SIgA was increased in patients with favorable clinical outcomes (

Figure 1E and F) and its high baseline level correlated with longer PFS and OS (

Figure 3I – L) in the study cohort, the Ig-bound fraction of total stool microbiota was purified, and its bacterial composition alongside the total stool microbiota composition was analyzed. The Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction could consist of microorganisms coated with IgA, IgG, and IgM. However, those coated with IgAs should constitute the largest fraction as SIgA is the dominant Ig produced in the intestinal secretions, while both IgG and IgM were found to be produced in much lower amounts in the gut [

13].

The analysis indicated that the Ig-bound stool microbiota of advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy was dominated by

Bacillota phylum members regardless of clinical outcome or collection time point (

Figure 4B and D). For comparison,

the Bacillota phylum was also the dominant one in the total stool microbiota; however, its dominance was less evident (

Figure 4A and C). Noteworthy,

the Bacillota phylum that elicited Ig responses in our cohort, was enriched in the baseline fecal microbiota of metastatic melanoma patients, who benefited from the anti-CTLA-4 therapy and more frequently experienced treatment-induced colitis [

44]. These findings demonstrated that

Bacillota phylum members influenced intestinal and systemic immunity. Consistently with the trends observed at the phylum level, beta diversity analysis indicated that the Ig-bound stool microbiota and the total stool microbiota shared a substantial subset of bacterial genera (

Figure 7A); however, the genera' relative abundance patterns differed between them (

Figure 7B). In line with that, some bacterial genera were detected only in the total or Ig-bound stool microbiota. While the presence of unique taxa in the total stool microbiota implies that a subset of bacteria was not coated with Igs, the detection of unique genera in the Ig-bound stool microbiota was unexpected. Differences in the genera’s relative abundance patterns between the microbiotas may resulted from the variations in the induction of Ig responses between bacterial genera, as it was demonstrated by Yang et al. (2020) [

37]. On the other hand, they (and the detection of unique genera in the Ig-bound stool microbiota) may be associated with the process of fraction purification that could lead to the enrichment in rare microorganisms. As a result, efficient amplification of their sequences and identification were feasible in the Ig-bound stool microbiota, but masked by the diversity in the total stool microbiota. It was shown that primers used for amplification may preferentially bind to certain sequences, leading to differential amplification efficiency. Consequently, some microbial groups could be overrepresented while others, particularly rare taxa, underrepresented or missed entirely [

45]. Furthermore, factors such as the number of PCR cycles, annealing temperatures, and the presence of inhibitors could introduce biases during amplification. Overamplification could lead to the dominance of certain sequences, masking the presence of rare microorganisms [

46].

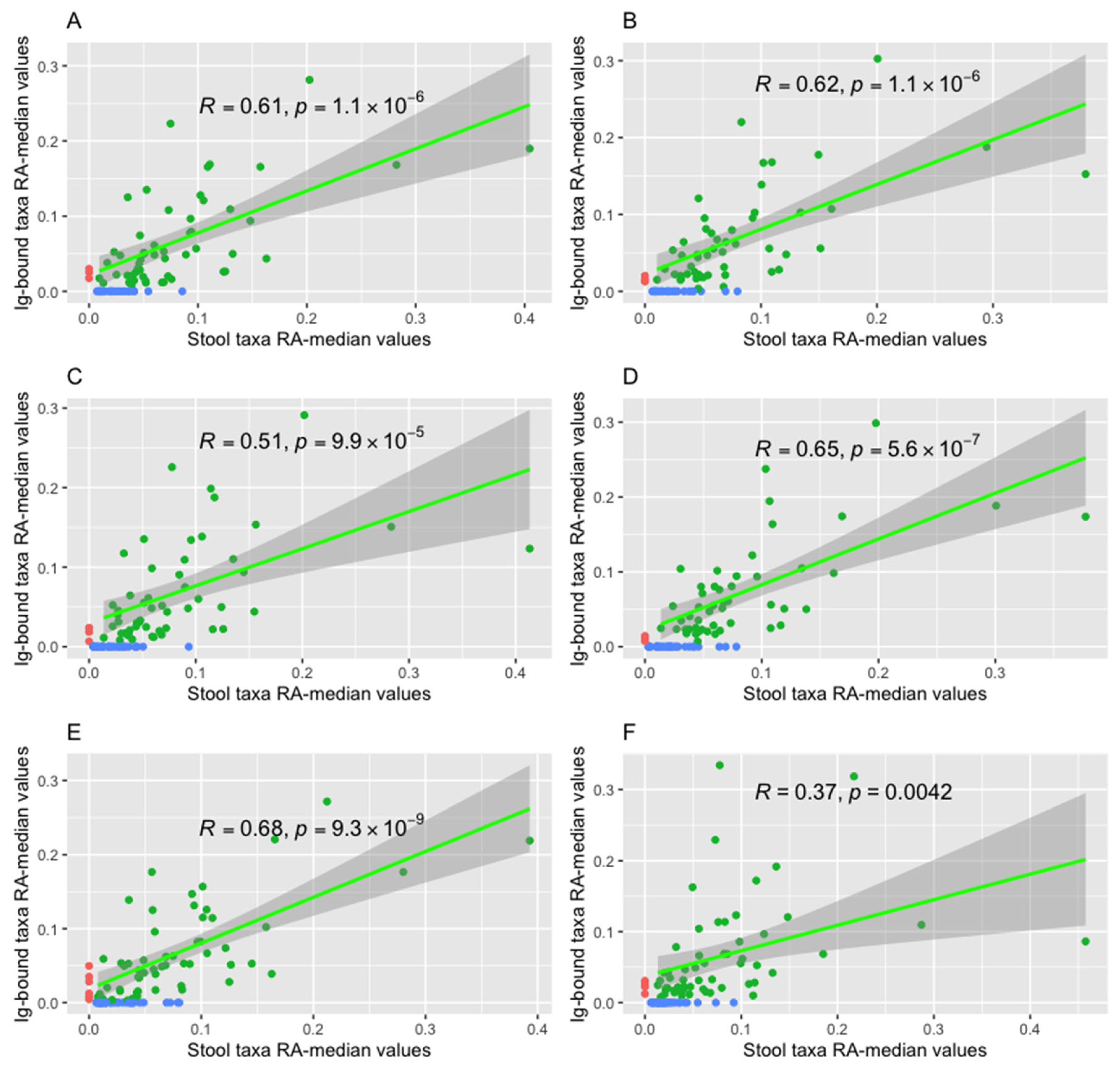

Furthermore, it was found that the relative abundance median values of bacterial genera in the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota correlated positively in all advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy and subgroups of patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes at T

0 and T

1 (

Figure 8 and

Figure S3). However, the Spearman’s

ρ value have changed during treatment, and trends in the changes were opposite between patients with distinct clinical outcomes (

Figure 8 and

Figure S3). These findings suggest that the anti-PD-1 therapy may affect Ig production in the intestines. This, in turn, may exert an impact on immune responses at the tumor site and clinical outcomes of the immunotherapy, as the most evident differences were found in the comparison between patients, who benefited from the anti-PD-1 therapy and those, who progressed. The impact of the anti-PD-1 therapy on the Ig production may also trigger the development of late adverse effects. Consistently, changes in the Ig-bound stool microbiota composition were observed during the anti-PD-1 therapy at the phylum (

Figure 5) and genus level (the DAA,

Figure 6). These changes were more noticeable in patients with unfavorable clinical outcomes than those with favorable ones (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The DAA also revealed that the highest variance in the relative abundance of bacterial genera in the Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction between patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes was at baseline (expressed as the number of differentially abundant genera); during treatment, the differences in the microbial signatures between subgroups were less evident (

Figure 6). Noteworthy, fecal SIgA level was also higher at baseline in patients with favorable clinical outcomes as compared to those with unfavorable ones. These findings also imply that anti-PD-1 therapy could exert an impact on the Ig response. In line with that, previous studies demonstrated the association between PD-1 expression on Peyer’s patches (PPs) T cells and IgA production [

47,

48,

49]. Kawamoto et al. (2012) indicated that PD-1 deficiency was associated with an excessive generation of T follicular helper (T

FH) cells with altered phenotypes that lead to impaired selection of IgA

+ B cells in the germinal centers (GCs) of PPs [

47,

48]. As a result, the IgAs produced in PD-1-deficient mice had reduced bacteria-binding capacity. That caused compositional alterations in the gut microbiota (a decrease in the anaerobic bacteria,

Bifidobacterium genus, and

Bacteroides genus, and an increase in the

Enterobacteriaceae family as compared to wild-type mice). Gut microbiota dysbiosis and associated disruption of epithelial integrity resulted in an excessive activation of the whole body immune system and an expansion of self-reactive B and T cells and auto-antibody production. Additionally, Zhang et al. (2015) demonstrated that intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in mice decreased PD-1/PD-L1 interaction on PP CD4

+ T cells [

49]. Lower PD-1/PD-L1 expression correlated with reduced production of cytokines involved in the proliferation and differentiation of IgA

+ B cells, such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF- β1) and interleukin-21 (IL-21), impaired intestinal IgA synthesis, and mucosal integrity. Collectively, these findings suggest that PD-1/PD-L signaling plays an important role in the regulation of IgA production and, consequently, affects the composition of the gut microbiota, intestinal barrier, and systemic immunity. All of these factors were found to exert an impact on clinical outcomes of ICIs in cancer patients [

8,

50]. To our knowledge, the influence of anti-PD-1 therapy on IgA production in the intestinal mucosa and, consequently, its effect on treatment efficacy has not been studied so far. However, changes in the Ig-bound stool microbiota composition during treatment (

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 8, and

Figure S3), especially those observed in patients, who did not respond or benefit from the anti-PD-1 therapy suggest that: firstly, anti-PD-1 antibodies, introduced to advanced melanoma patients, affected SIgA generation, leading to distinct effects in patients with favorable and unfavorable clinical outcomes; secondly, in patients who did not benefit from the immunotherapy, anti-PD-1 antibodies inhibited the PD-1/PD-L interaction in the intestinal mucosa and therefore, affected IgA production; thirdly, changes in the SIgA production affected the gut microbiota composition, and consequently the whole-body immune system and clinical outcomes of anti-PD-1 therapy. In line with that, the composition of the total stool microbiota has changed during treatment, i.e., there were alterations in the relative abundance patterns at the phylum level (

Figure S1B, E, and F) and at the genus level indicated in the DAA (

Figure S2A and B). Noteworthy, changes in the total stool microbiota composition during the anti-PD-1 therapy, similarly to trends observed in the Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction, were more evident in patients with unfavorable clinical outcomes (

Figures S1 and S2), supporting our assumption that anti-PD-1 antibodies could affect the gut microbiota through the disruption of IgA generation. On the other hand, there were found no statistically significant changes in the intestinal barrier state biomarker levels during treatment within study subgroups (

Figure 1), which indicates a lack of profound influence of the anti-PD-1 therapy on the intestinal barrier functionality. However, it is worth noting that the median fecal SIgA concentration tended to decrease at T

n (as compared to the baseline median level) in the R subgroup, while in the NR subgroup, it increased ~2 times at T

1, being comparable to that observed in the R subgroup at T

1, and decreased at T

n, being comparable to that observed at baseline (

Figure 1). Accordingly, Kawamoto et al. (2012) reported that despite of reduced bacteria-binding capacity in the PD-1-deficient mice, the concentration of free IgA in intestinal secretions was higher in them than in wild-type mice [

47,

48].

Taken together, our study demonstrated that alterations in the Ig responses, potentially associated with the introduction of anti-PD-1 antibodies, could affect the composition of the gut microbiota in advanced melanoma patients, and, therefore, influence the clinical outcomes of the immunotherapy. However, intestinal immunity responses could also shape anti-cancer immune responses through the modification of the functional potential of the gut microbiota. It was reported that bacterial antigen coating by SIgA may affect the function of the targeted microbe [

51], and not necessarily its abundance. Briefly, Rollenske et al. (2021), in a study on a murine model monocolonized with

Escherichia coli, demonstrated that exposure of the intestinal mucosa with a single transitory microbe induced the generation of antigen-specific dimeric SIgA that targeted a wide range of membrane-associated antigens. Monoclonal IgA (mIgA) binding to bacterial antigens exerted distinct alterations in microbial function and metabolism (also when mIgAs targeted the same antigens). The outcome on the target bacterium was shaped by the context and specificity of mIgAs. On the other hand, surface-binding mIgAs induced generic functional effects on the bacteria associated with their motility and susceptibility to bile acids. In our study, we found numerous correlations between the particular relative abundances of bacterial ASVs in the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota in the R and NR subgroups at baseline (

Table S2). Moreover, these correlations differed between those subgroups, and a subset of them was opposed. Among bacterial taxa in the Ig-bound stool microbiota that correlated with taxa in the total stool microbiota, and their correlations were opposed in the R vs. NR subgroups, there were those indicated in previous studies as favorable or unfavorable in cancer patients undergoing ICI therapy, such as

Akkermansia muciniphila,

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii,

Bacteroides sp., and

Bifidobacterium sp. [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56]. According the findings of Rollenske et al. (2021) [

51], observed correlations indicate that the presence or absence of bacterial taxa does not fully reflect their functional activities and their influence on anti-cancer immune responses (both favorable and unfavorable), as they may be changed by Ig coating. This phenomenon may explain, at least partially, the existing discrepancies between microbiome studies in cancer patients treated with ICIs and extend our understanding of the complexity of host immunity-gut microbiota interaction. To our knowledge, our study is the first one that investigated the composition of the Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction in advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy and shed light on the association between intestinal immunity and clinical outcomes of the immunotherapy. Future studies are required to provide mechanistic insight into the association between PD-1 antibodies and SIgA production and the relationship between intestinal immunity, gut microbiota, and anticancer immune responses. Moreover, it should be also investigated whether the introduction of SIgAs targeting specific microbial antigens (that may induce diverse functional changes [

51]) could constrain gut microbes for mutualistic behavior within the host intestine or lead to their eradication from the gastrointestinal tract and serve as a strategy to improve the clinical outcomes of the ICI therapy. Richards et al. (2021) demonstrated that passive oral administration of human recombinant Sal4 SIgA (specific for the O5 antigen of

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium lipopolysaccharide) led to the entrapment of the pathogen within the intestinal lumen and remarkably reduced its invasion into the gut-associated lymphoid tissue in mice [

57]. This study indicated that specific SIgAs have the potential to combat pathogenic species. If the targeted modification of the gut microbiota through SIgAs was achievable, it would provide an alternative to conventional FMT, which possess several limitations, such as risk of pathogen transfer, stool toxicity, low reproducibility, and transient long-term outcome [

58].

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the study comprised a small number of patients, which limited the power of statistical analyses. Secondly, the V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene sequencing, which was performed to analyze the composition of the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota, allowed only for the detection of bacterial and archaeal sequences, while viruses and fungi could also be present in these microbial communities. Therefore, it is recommended to use whole-genome sequencing to provide a comprehensive analysis of the composition and functional potential of the investigated microbiotas. Thirdly, the specificity of Igs, their microbe-binding capacity, and antigens that elicited Ig responses (potential food allergies) were not analyzed in our study. Thus, future mechanistic studies that will extend our understanding of the role of intestinal immunity in shaping anti-cancer immune responses are warranted.

Figure 1.

The comparison of intestinal barrier state biomarker concentrations, i.e., fecal zonulin (A and B), fecal calprotectin (C and D), and fecal secretory immunoglobulin A – SIgA (E and F) in advanced melanoma patients before anti-PD-1 therapy initiation – at T0 (0) and during treatment – at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders (R) or non-responders (NR), and patients with clinical benefit (CB) or patients with no clinical benefit (NB), according to the clinical outcome. Statistics were performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test; p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as significant (*: p-values ≤ 0.05). The figures show that a high baseline level of fecal SIgA was associated with response and clinical benefit from the anti-PD-1 therapy in advanced melanoma patients. Statistically significant differences in the biomarker levels between noncorresponding subgroups, i.e., subgroups with distinct clinical outcomes to the anti-PD-1 therapy at different collection time points, are not marked in the figures. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 1.

The comparison of intestinal barrier state biomarker concentrations, i.e., fecal zonulin (A and B), fecal calprotectin (C and D), and fecal secretory immunoglobulin A – SIgA (E and F) in advanced melanoma patients before anti-PD-1 therapy initiation – at T0 (0) and during treatment – at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders (R) or non-responders (NR), and patients with clinical benefit (CB) or patients with no clinical benefit (NB), according to the clinical outcome. Statistics were performed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test; p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as significant (*: p-values ≤ 0.05). The figures show that a high baseline level of fecal SIgA was associated with response and clinical benefit from the anti-PD-1 therapy in advanced melanoma patients. Statistically significant differences in the biomarker levels between noncorresponding subgroups, i.e., subgroups with distinct clinical outcomes to the anti-PD-1 therapy at different collection time points, are not marked in the figures. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 2.

The mutual correlations between intestinal barrier state biomarkers, i.e., fecal zonulin, fecal calprotectin, and fecal secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) and

Firmicutes to

Bacteroidota (FB) ratio in the total stool microbiota in advanced melanoma patients. The correlations were examined in all analyzed samples and the study subgroups at particular collection time points, i.e., before anti-PD-1 initiation at T

0 (0) and during therapy at T

1 and T

n (1 and n, respectively). Patients were categorized into subgroups: responders (R) or non-responders (NR) and patients with clinical benefit (CB) or those with no clinical benefit (NB) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. Statistics were performed using the Spearman’s Rank Correlation Test. The

p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Figure 2A–C show the trends observed in all analyzed samples; 2D – in the NR0 subgroup; 2E – in the NB0 subgroup; 2F – in the R0 subgroup; 2G – in the R1 subgroup; 2H – in the R0 subgroup; 2I – in the CB0 subgroup. There were found distinct correlations between analyzed biomarkers in advanced melanoma patients with favorable vs. unfavorable clinical outcomes of anti-PD-1 therapy. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 2.

The mutual correlations between intestinal barrier state biomarkers, i.e., fecal zonulin, fecal calprotectin, and fecal secretory immunoglobulin A (SIgA) and

Firmicutes to

Bacteroidota (FB) ratio in the total stool microbiota in advanced melanoma patients. The correlations were examined in all analyzed samples and the study subgroups at particular collection time points, i.e., before anti-PD-1 initiation at T

0 (0) and during therapy at T

1 and T

n (1 and n, respectively). Patients were categorized into subgroups: responders (R) or non-responders (NR) and patients with clinical benefit (CB) or those with no clinical benefit (NB) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. Statistics were performed using the Spearman’s Rank Correlation Test. The

p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Figure 2A–C show the trends observed in all analyzed samples; 2D – in the NR0 subgroup; 2E – in the NB0 subgroup; 2F – in the R0 subgroup; 2G – in the R1 subgroup; 2H – in the R0 subgroup; 2I – in the CB0 subgroup. There were found distinct correlations between analyzed biomarkers in advanced melanoma patients with favorable vs. unfavorable clinical outcomes of anti-PD-1 therapy. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

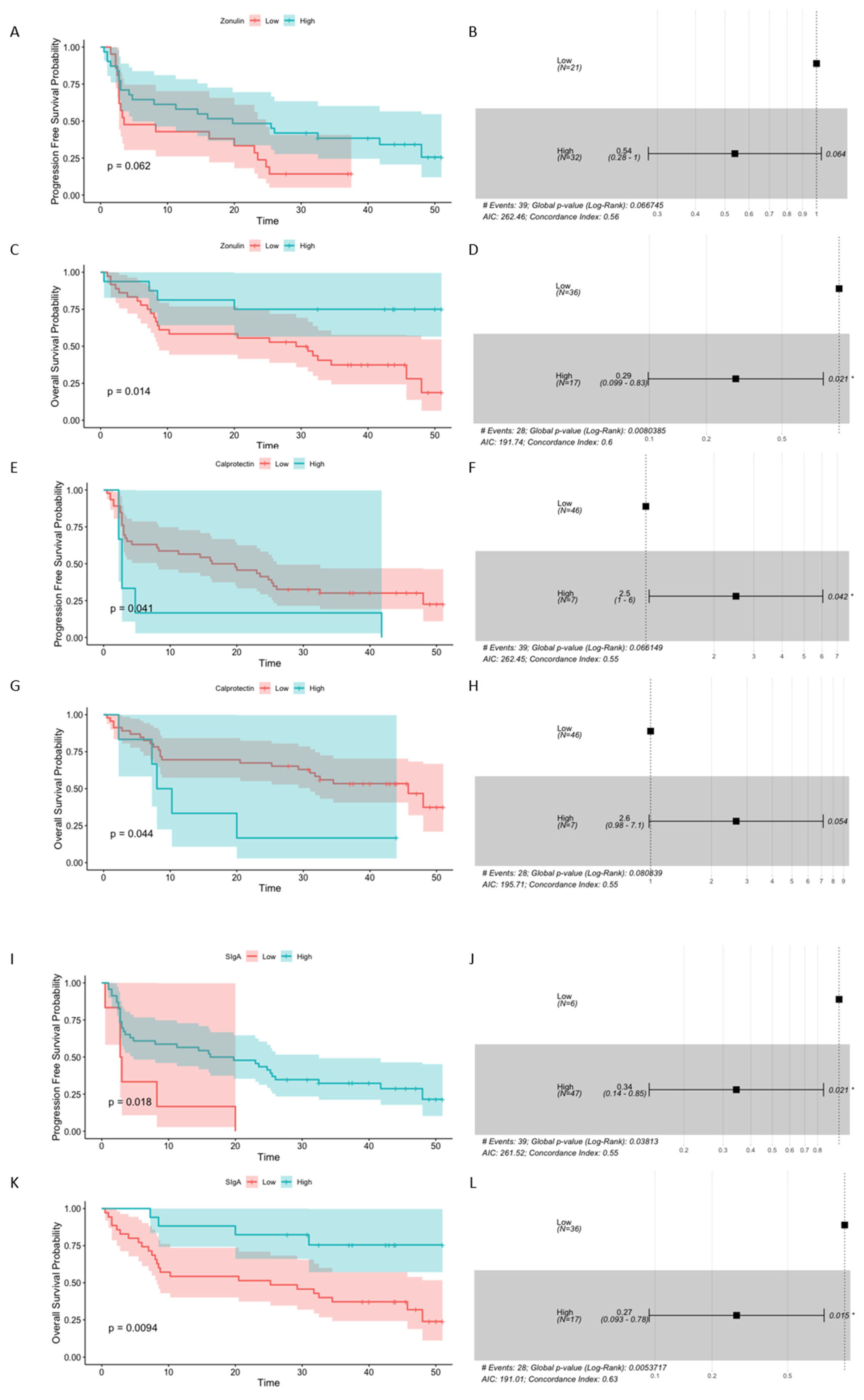

Figure 3.

The association between the baseline concentrations of investigated intestinal barrier state biomarkers, i.e., fecal zonulin (A–D), fecal calprotectin (E–H), and fecal secretory immunoglobulin A – SIgA (I–L) and survival outcomes, expressed as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), in advanced melanoma patients enrolled in the treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies. On the left side of the graph, there are presented Kaplan–Meier curves of the probability of PFS (A, E, and I) and OS (C, G, and K) according to high and low levels of investigated biomarkers, which were compared using the Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) Test; p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Vertical ticks show censored data. The central line is the median PFS or OS probability, and the shaded area shows a 95% confidence interval. The maximally selected rank statistics were used to determine optimal cut-off points of biomarker levels. The Cox proportional hazard regression was used to examine the effects of high vs. low baseline concentrations of biomarkers on survival outcomes. On the right side (B, D, F, H, J, and L), there are presented hazard ratio (HR) and score (log-rank) test two-tailed p-value from Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (*: p-value ≤ 0.05). HR > 1 indicates an increased risk of disease progression or death, while HR < 1 – a decreased risk. The figures show that high fecal zonulin and fecal SIgA levels at baseline were associated with improved survival outcomes in advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy, while high baseline fecal calprotectin level – with poor survival outcomes. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 3.

The association between the baseline concentrations of investigated intestinal barrier state biomarkers, i.e., fecal zonulin (A–D), fecal calprotectin (E–H), and fecal secretory immunoglobulin A – SIgA (I–L) and survival outcomes, expressed as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), in advanced melanoma patients enrolled in the treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies. On the left side of the graph, there are presented Kaplan–Meier curves of the probability of PFS (A, E, and I) and OS (C, G, and K) according to high and low levels of investigated biomarkers, which were compared using the Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) Test; p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Vertical ticks show censored data. The central line is the median PFS or OS probability, and the shaded area shows a 95% confidence interval. The maximally selected rank statistics were used to determine optimal cut-off points of biomarker levels. The Cox proportional hazard regression was used to examine the effects of high vs. low baseline concentrations of biomarkers on survival outcomes. On the right side (B, D, F, H, J, and L), there are presented hazard ratio (HR) and score (log-rank) test two-tailed p-value from Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (*: p-value ≤ 0.05). HR > 1 indicates an increased risk of disease progression or death, while HR < 1 – a decreased risk. The figures show that high fecal zonulin and fecal SIgA levels at baseline were associated with improved survival outcomes in advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy, while high baseline fecal calprotectin level – with poor survival outcomes. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

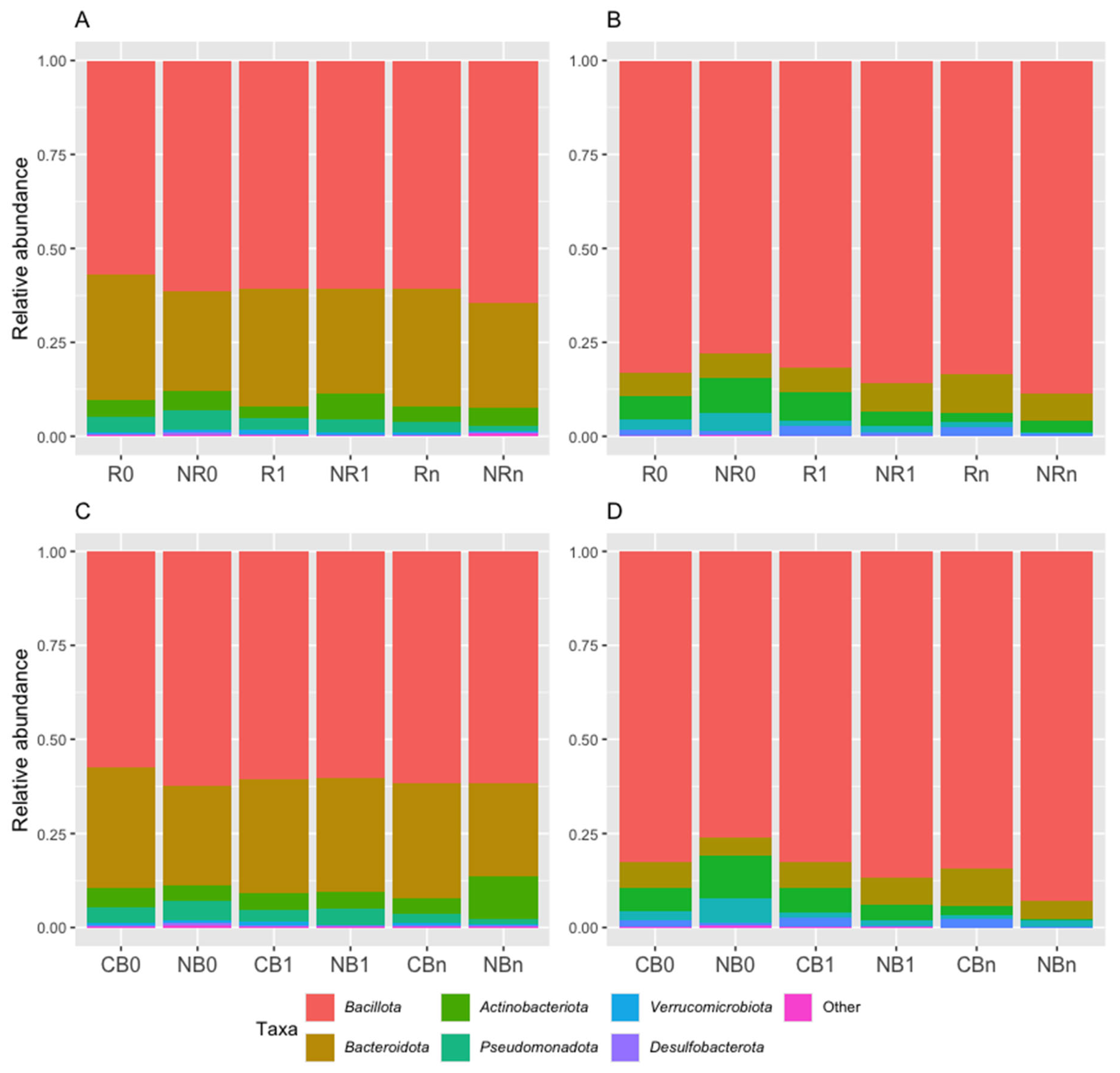

Figure 4.

Taxonomic profiles as averaged relative abundances of bacterial taxa in the total stool microbiota (A and C) and immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota (B and D) at the phylum level in advanced melanoma patients undergoing the anti-PD-1 therapy, before its start – at T0 (0) and during treatment – at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders – R or non-responders – NR (A and B) and as patients with clinical benefit – CB or patients with no clinical benefit – NB (C and D) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The total stool microbiota was dominated by phyla Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes) and Bacteroidota (formerly Bacteroidetes), while in the Ig-bound stool microbiota, there was a remarkable dominance of phylum Bacillota members in all study subgroups. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 4.

Taxonomic profiles as averaged relative abundances of bacterial taxa in the total stool microbiota (A and C) and immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota (B and D) at the phylum level in advanced melanoma patients undergoing the anti-PD-1 therapy, before its start – at T0 (0) and during treatment – at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders – R or non-responders – NR (A and B) and as patients with clinical benefit – CB or patients with no clinical benefit – NB (C and D) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The total stool microbiota was dominated by phyla Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes) and Bacteroidota (formerly Bacteroidetes), while in the Ig-bound stool microbiota, there was a remarkable dominance of phylum Bacillota members in all study subgroups. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

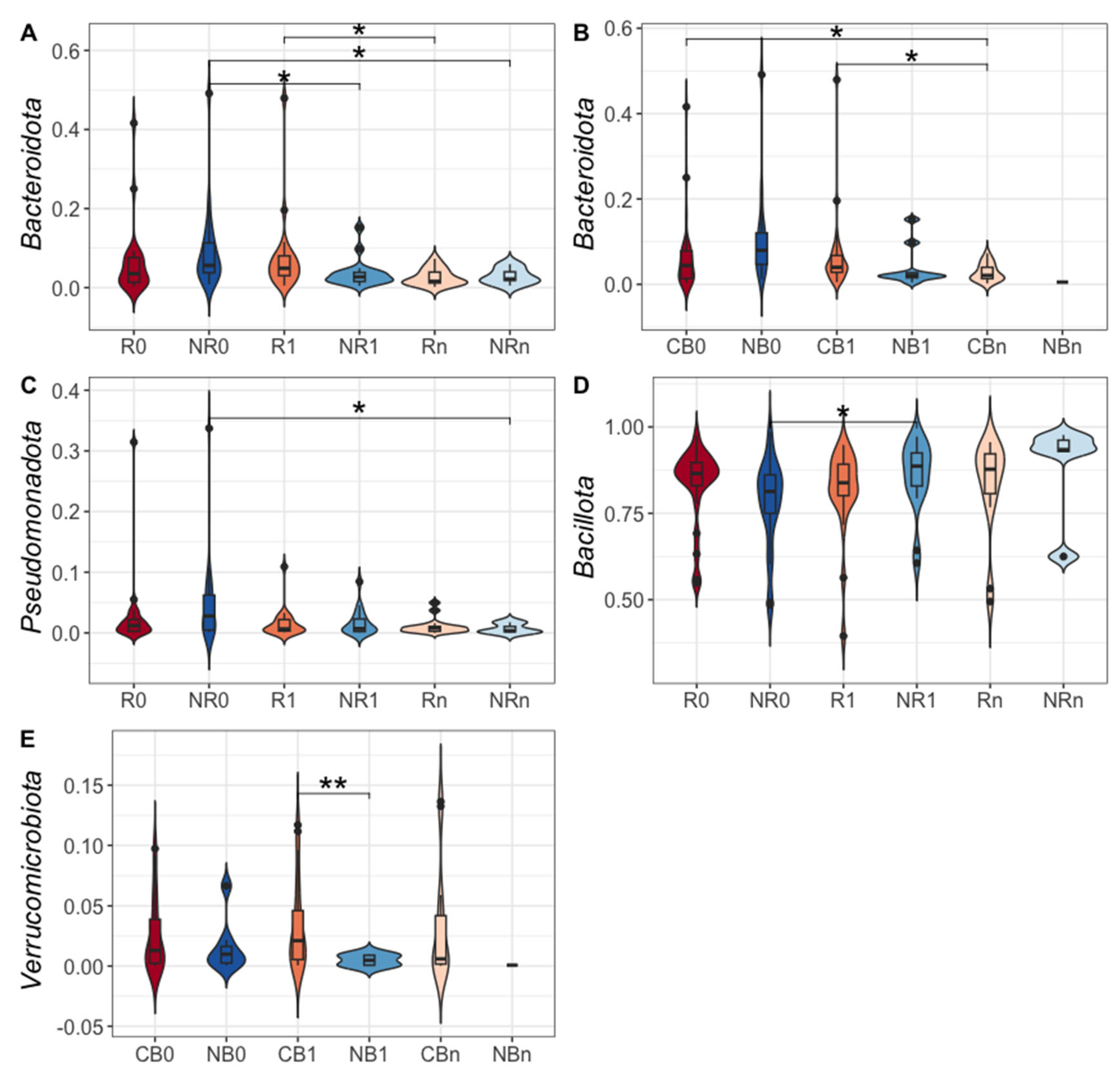

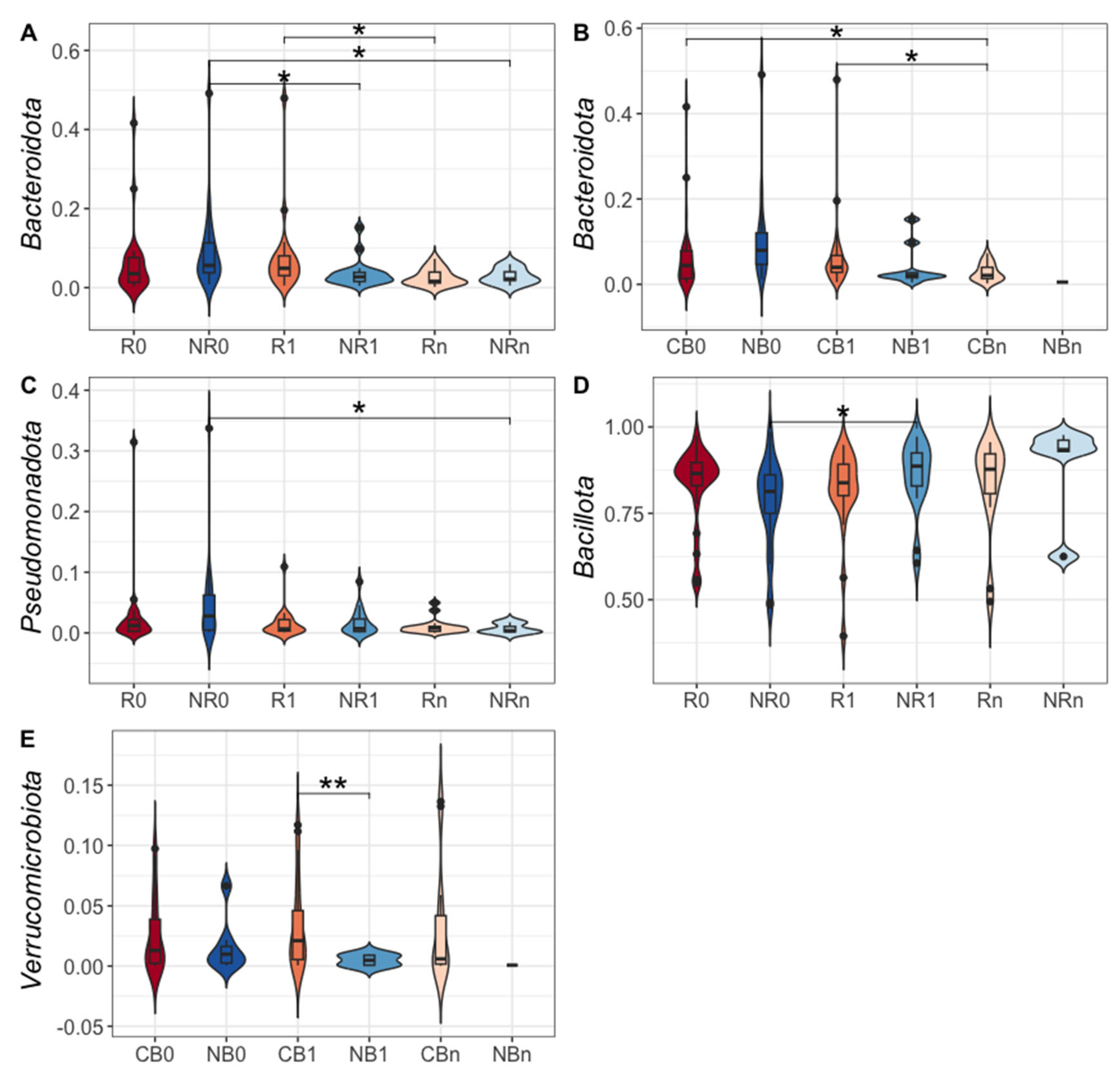

Figure 5.

The comparison of the relative abundances of phyla: Bacteroidota – formerly Bacteroidetes (A and B), Pseudomonadota – formerly Proteobacteria (C), Bacillota – formerly Firmicutes (D), and Verrucomicrobiota – formerly Verrucomicrobia (E) in the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota between advanced melanoma patients receiving the anti-PD-1 therapy, before the its start at T0 (0) and during treatment at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders – R or non-responders – NR (A, C, and D) and patients with clinical benefit – CB or patients with no clinical benefit – NB (B and E) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The p-values describing the statistical significance of the differences in the relative abundances of particular phyla between study subgroups were calculated with the Student’s t-test. The p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as significant (*: p-value ≤ 0.05, **: p-value ≤ 0.01). Statistics indicated a decrease in the relative abundances of phyla Bacteroidota and Pseudomonadota and an increase in phylum Bacillota during anti-PD-1 therapy in the NR subgroup. A decrease in the relative abundance of Bacteroidota was also observed in the R and CB subgroups during treatment. Moreover, there was a higher relative abundance of Verrucomicrobiota phylum in the CB vs. NB subgroup at T1. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 5.

The comparison of the relative abundances of phyla: Bacteroidota – formerly Bacteroidetes (A and B), Pseudomonadota – formerly Proteobacteria (C), Bacillota – formerly Firmicutes (D), and Verrucomicrobiota – formerly Verrucomicrobia (E) in the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota between advanced melanoma patients receiving the anti-PD-1 therapy, before the its start at T0 (0) and during treatment at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders – R or non-responders – NR (A, C, and D) and patients with clinical benefit – CB or patients with no clinical benefit – NB (B and E) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The p-values describing the statistical significance of the differences in the relative abundances of particular phyla between study subgroups were calculated with the Student’s t-test. The p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as significant (*: p-value ≤ 0.05, **: p-value ≤ 0.01). Statistics indicated a decrease in the relative abundances of phyla Bacteroidota and Pseudomonadota and an increase in phylum Bacillota during anti-PD-1 therapy in the NR subgroup. A decrease in the relative abundance of Bacteroidota was also observed in the R and CB subgroups during treatment. Moreover, there was a higher relative abundance of Verrucomicrobiota phylum in the CB vs. NB subgroup at T1. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

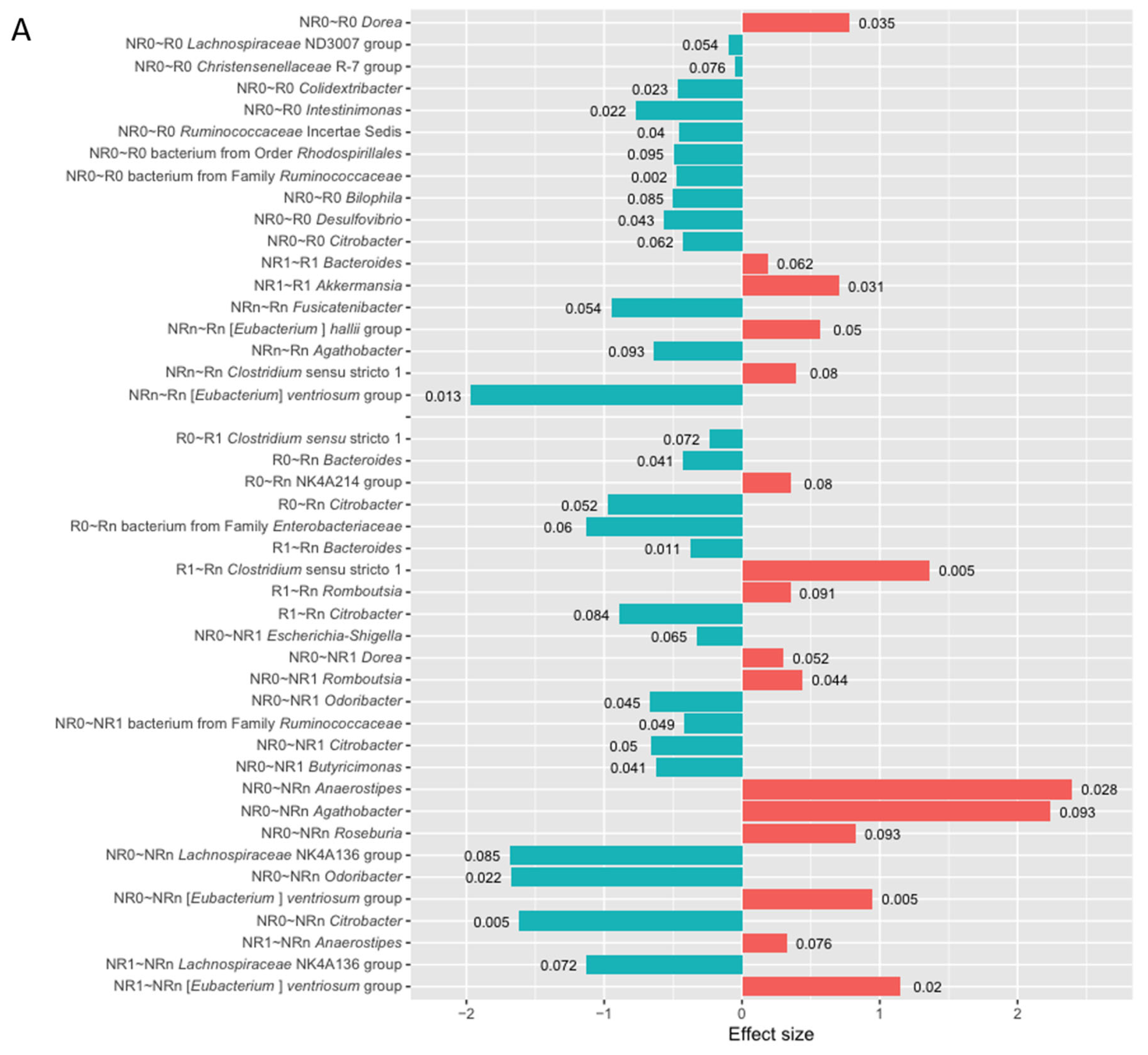

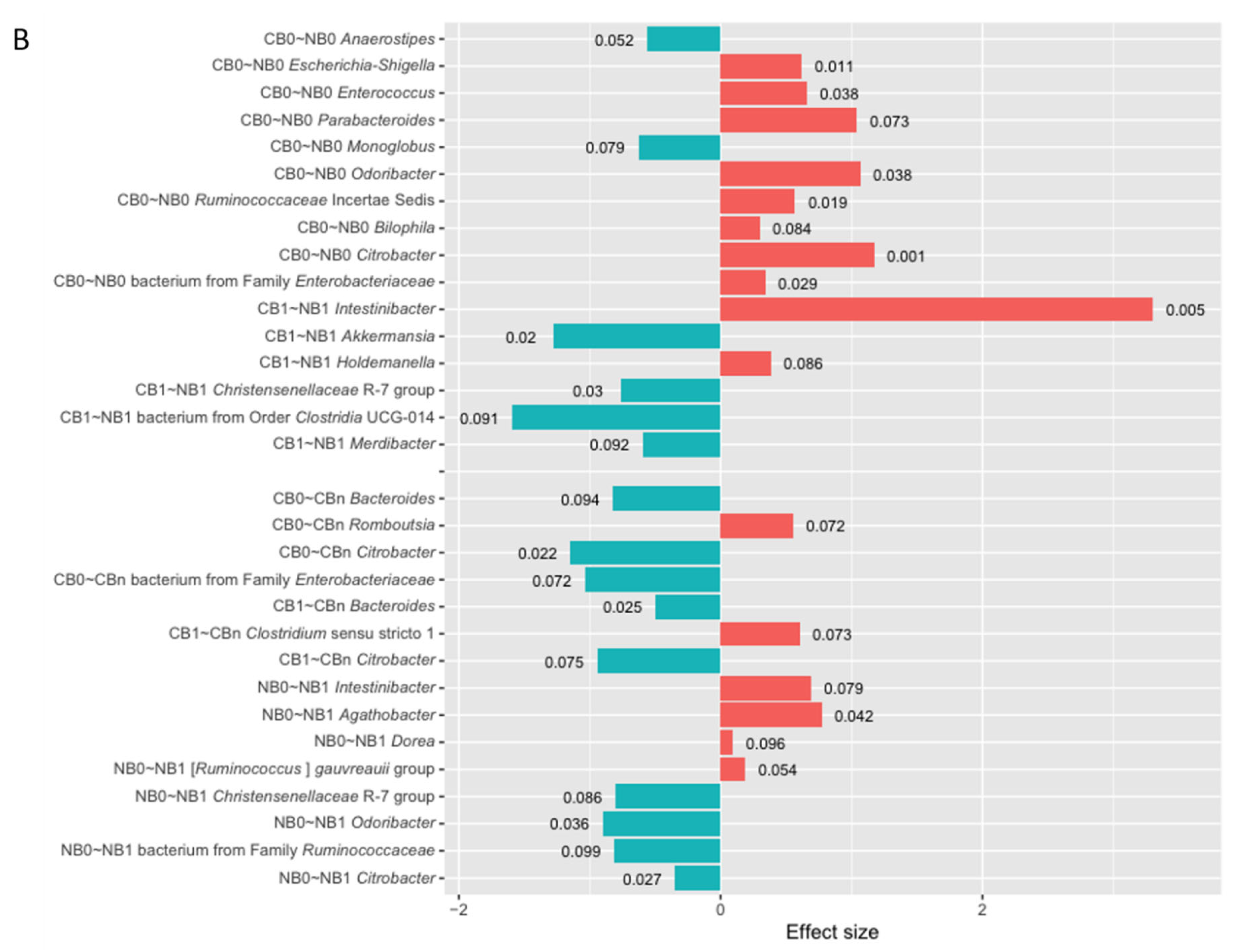

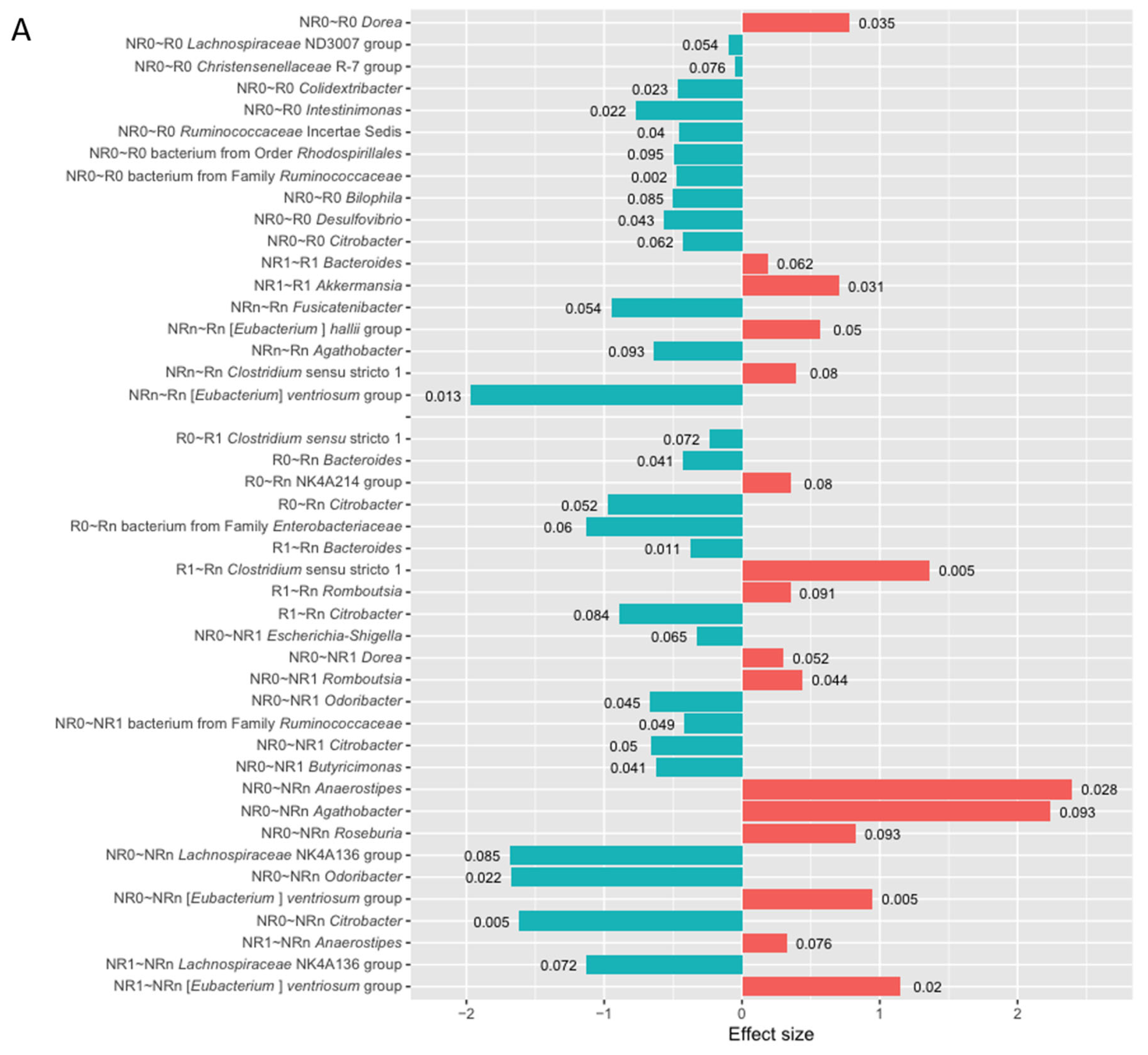

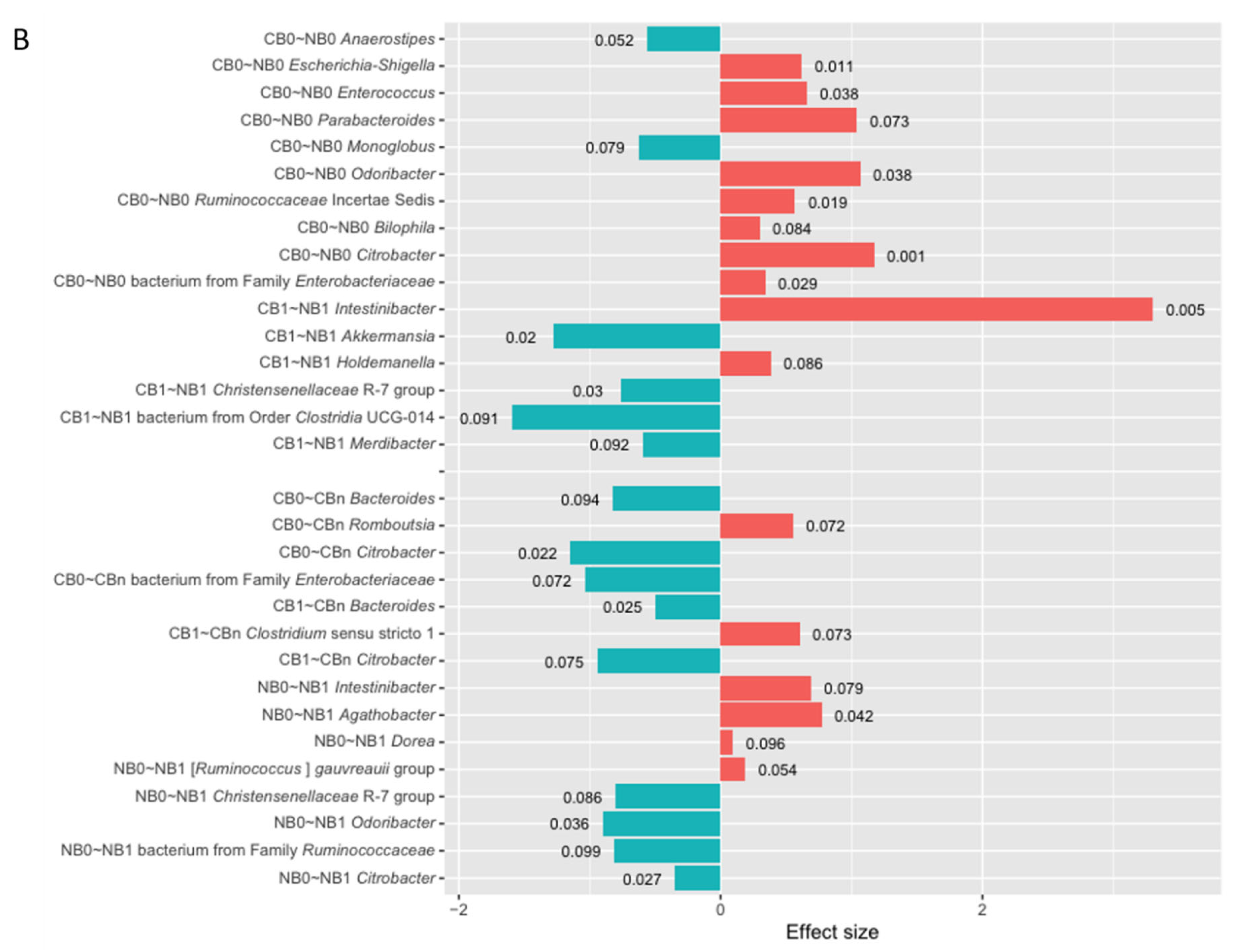

Figure 6.

The differentially abundant genera in the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota between advanced melanoma patients with favorable vs. unfavorable clinical outcomes of the anti-PD-1 therapy, before its start – at T0 (0) and during treatment – at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively) identified in the differential abundance analysis (DAA) performed using ANOVA-like Differential Expression version 2 (ALDEx2) tool. Moreover, changes in the relative abundances of genera during treatment (T0 vs. T1, T0 vs. Tn, and T1 vs. Tn) within those subgroups were also indicated with the DAA. Patients were classified as responders – R or non-responders – NR (A) and as patients with clinical benefit – CB or patients with no clinical benefit – NB (B) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The figures illustrate only the statistically significant results (The Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, p-value < 0.1 was regarded as significant). The p-values describing the statistical significance of the DAA results were placed at the tips of the bars. The direction of changes in the relative abundances of taxa between the two subgroups being compared was assessed based on the effect size values. The first group of the two being compared is considered a reference group, whereas the second one is a tested group (group designations are placed on the left side of the graph at the beginning of the following lines; ‘reference group~tested group’). A positive effect size (red bars) suggests a higher relative abundance of a particular taxon in the tested group compared to the reference group, while negative (blue bars) – lower. Effect size also measures the biological significance of the observed differences (the larger the effect size, the more substantial the difference between subgroups). The names of the differentially abundant taxa are placed on the left side of the graph (next to the subgroup designation). The DAA indicated that the Ig-bound stool microbiota signatures were associated with clinical outcomes of the anti-PD-1 therapy and have changed during treatment. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 6.

The differentially abundant genera in the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota between advanced melanoma patients with favorable vs. unfavorable clinical outcomes of the anti-PD-1 therapy, before its start – at T0 (0) and during treatment – at T1 and Tn (1 and n, respectively) identified in the differential abundance analysis (DAA) performed using ANOVA-like Differential Expression version 2 (ALDEx2) tool. Moreover, changes in the relative abundances of genera during treatment (T0 vs. T1, T0 vs. Tn, and T1 vs. Tn) within those subgroups were also indicated with the DAA. Patients were classified as responders – R or non-responders – NR (A) and as patients with clinical benefit – CB or patients with no clinical benefit – NB (B) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The figures illustrate only the statistically significant results (The Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, p-value < 0.1 was regarded as significant). The p-values describing the statistical significance of the DAA results were placed at the tips of the bars. The direction of changes in the relative abundances of taxa between the two subgroups being compared was assessed based on the effect size values. The first group of the two being compared is considered a reference group, whereas the second one is a tested group (group designations are placed on the left side of the graph at the beginning of the following lines; ‘reference group~tested group’). A positive effect size (red bars) suggests a higher relative abundance of a particular taxon in the tested group compared to the reference group, while negative (blue bars) – lower. Effect size also measures the biological significance of the observed differences (the larger the effect size, the more substantial the difference between subgroups). The names of the differentially abundant taxa are placed on the left side of the graph (next to the subgroup designation). The DAA indicated that the Ig-bound stool microbiota signatures were associated with clinical outcomes of the anti-PD-1 therapy and have changed during treatment. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

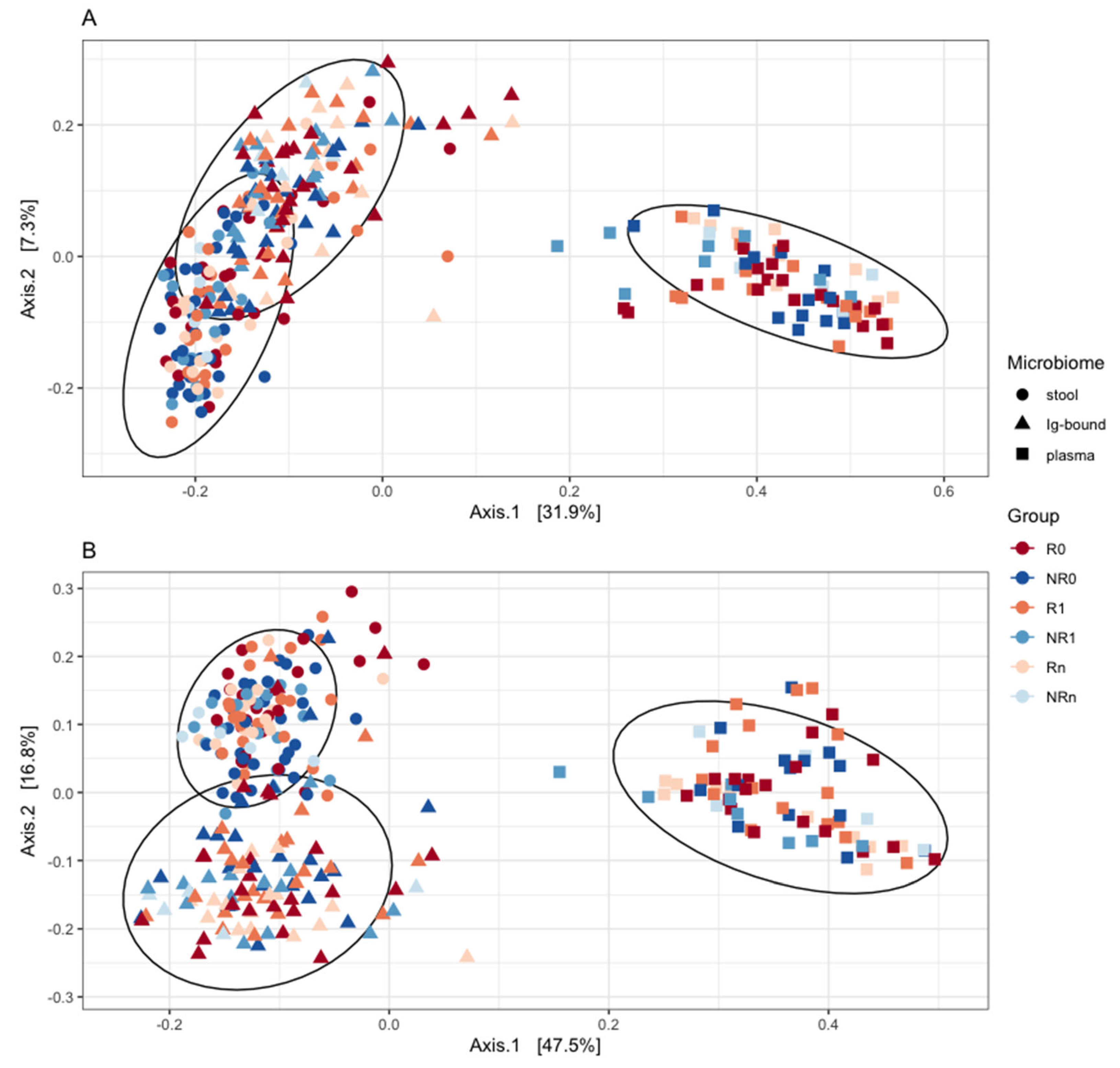

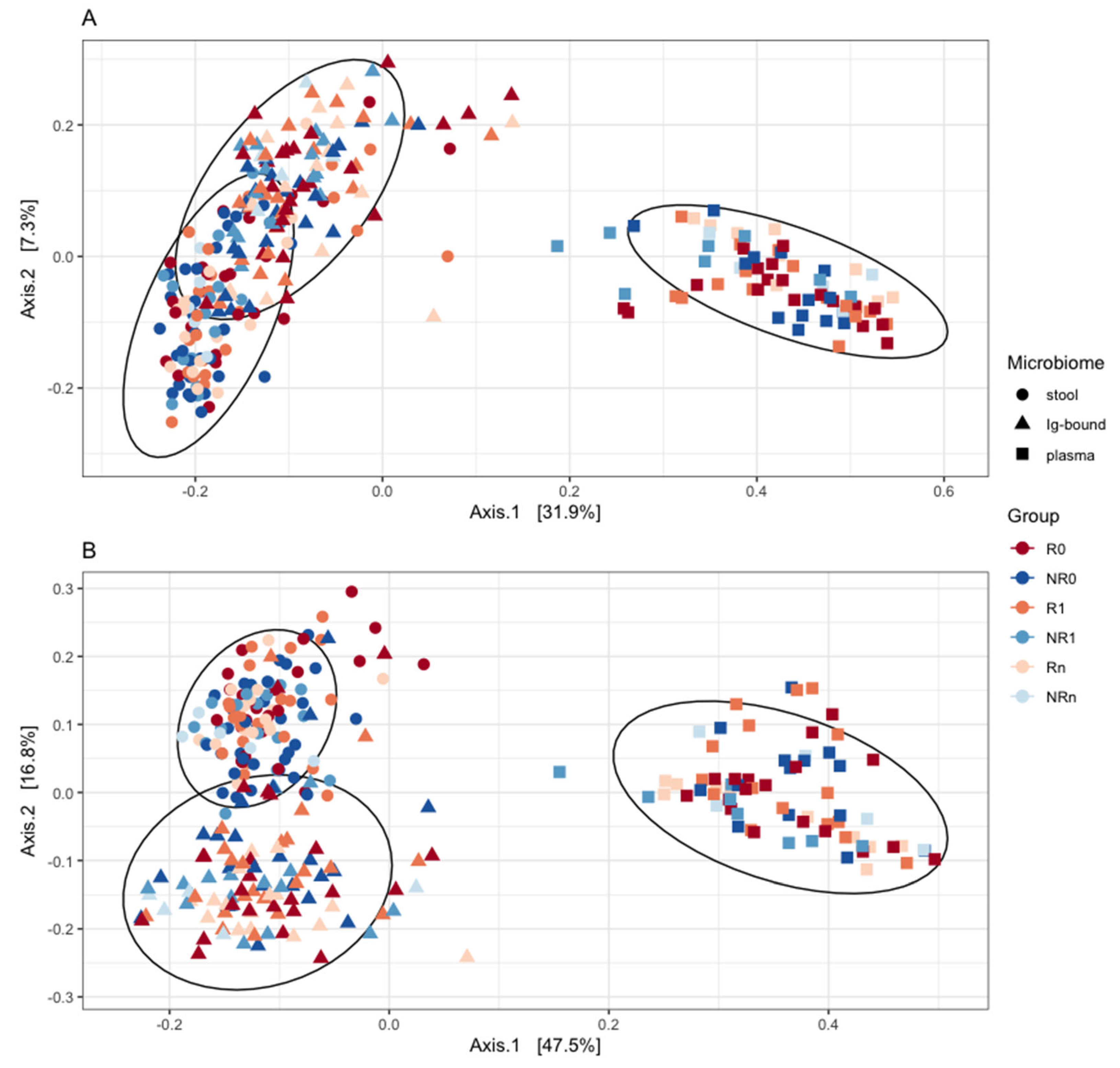

Figure 7.

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on a quantitative distance measures (A; weighted-UniFrac) and a qualitative distance measures (B; unweighted-UniFrac) was performed to compare the similarities and dissimilarities between the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota (indicated by triangles) and total stool microbiota (indicated by dots) at the genus level (beta diversity analysis). The circulating cell-free microbial DNA – cfmDNA (plasma; indicated by squares) of the same patients (published in a separate paper [

26]) was added to the plot for reference purposes to better visualize distances between the microbiotas. The microbiota composition was analyzed in advanced melanoma patients before – at T

0 (0) and during anti-PD-1 therapy – at T

1 and T

n (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders (R) or non-responders (NR) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The figures demonstrate that the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota shared a subset of taxa (A), but at different abundances (B). Moreover, the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota grouped separately from the circulating cfmDNA (A and B). PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 7.

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on a quantitative distance measures (A; weighted-UniFrac) and a qualitative distance measures (B; unweighted-UniFrac) was performed to compare the similarities and dissimilarities between the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota (indicated by triangles) and total stool microbiota (indicated by dots) at the genus level (beta diversity analysis). The circulating cell-free microbial DNA – cfmDNA (plasma; indicated by squares) of the same patients (published in a separate paper [

26]) was added to the plot for reference purposes to better visualize distances between the microbiotas. The microbiota composition was analyzed in advanced melanoma patients before – at T

0 (0) and during anti-PD-1 therapy – at T

1 and T

n (1 and n, respectively). Patients were classified as responders (R) or non-responders (NR) according to the clinical outcome of the immunotherapy. The figures demonstrate that the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota shared a subset of taxa (A), but at different abundances (B). Moreover, the Ig-bound and total stool microbiota grouped separately from the circulating cfmDNA (A and B). PD-1 – programmed death 1.

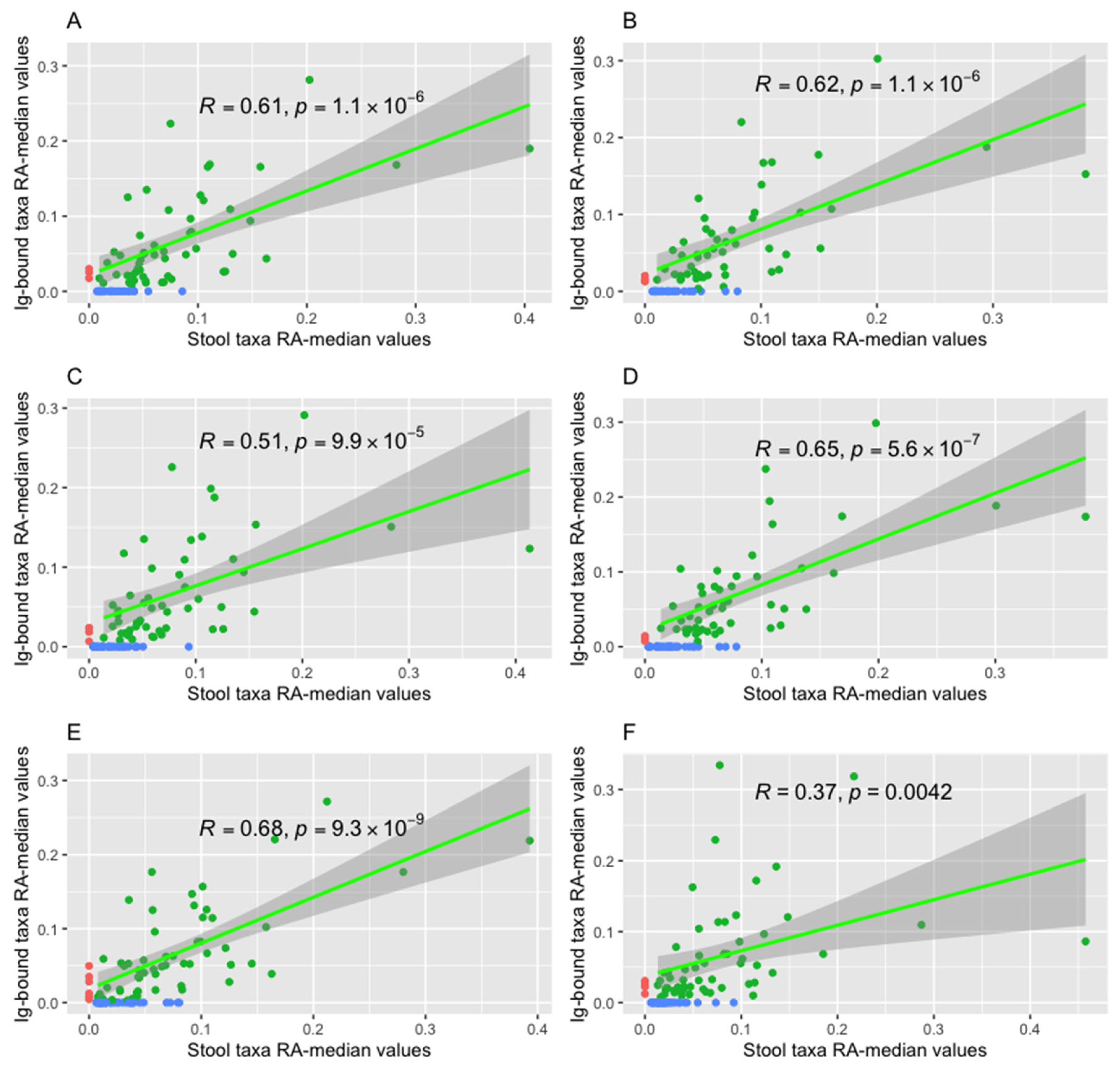

Figure 8.

The correlations between the relative abundance (RA) median values of bacteria (at the genus level) detected in the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota fraction and total stool microbiota (green dots and line) were analyzed in all advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy (A and B), and subgroups of patients with clinical benefit – CB (C and D) or no clinical benefit – NB (E and F) from the immunotherapy, before its start – at T

0 (0; A, C, and E) and during treatment – at T

1 (1; B, D, and F). Statistics were performed using the Spearman’s Rank Correlation Test. The

p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Figure 8A and B show the trends observed in all patients at T

0 and T

1, respectively; 8C and D – in the CB0 and CB1 subgroups, respectively; 8E and F – in the NB0 and NB1 subgroups, respectively. Genera detected only in the total stool microbiota (blue dots) or in the Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction (red dots) were also indicated in the figures. The figures demonstrate positive correlations between the RA median values of genera in the Ig-bound stool microbiota and total stool microbiota in all advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy, and the CB and NB subgroups at T

0 and T

1. In patients with favorable clinical outcomes, there was an increase in the Spearman’s

ρ value during treatment, while in those with unfavorable ones, there was an opposite trend. PD-1 – programmed death 1.

Figure 8.

The correlations between the relative abundance (RA) median values of bacteria (at the genus level) detected in the immunoglobulin (Ig)-bound stool microbiota fraction and total stool microbiota (green dots and line) were analyzed in all advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy (A and B), and subgroups of patients with clinical benefit – CB (C and D) or no clinical benefit – NB (E and F) from the immunotherapy, before its start – at T

0 (0; A, C, and E) and during treatment – at T

1 (1; B, D, and F). Statistics were performed using the Spearman’s Rank Correlation Test. The

p-value ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Figure 8A and B show the trends observed in all patients at T

0 and T

1, respectively; 8C and D – in the CB0 and CB1 subgroups, respectively; 8E and F – in the NB0 and NB1 subgroups, respectively. Genera detected only in the total stool microbiota (blue dots) or in the Ig-bound stool microbiota fraction (red dots) were also indicated in the figures. The figures demonstrate positive correlations between the RA median values of genera in the Ig-bound stool microbiota and total stool microbiota in all advanced melanoma patients undergoing anti-PD-1 therapy, and the CB and NB subgroups at T

0 and T

1. In patients with favorable clinical outcomes, there was an increase in the Spearman’s

ρ value during treatment, while in those with unfavorable ones, there was an opposite trend. PD-1 – programmed death 1.