1. Introduction

In recent years, China has faced intensifying population ageing, with rural labor shortages emerging as a critical constraint on rural revitalization. Agricultural automation and intelligentization represent an irreversible trend for the future of farming [

1,

2,

3]. With continuous advancements in technology, agricultural robots have emerged as a viable solution to replace human labor in repetitive agricultural tasks. These robots not only significantly enhance operational efficiency and quality but also inject new momentum into sustainable agricultural development. Their immense potential and promising prospects have garnered significant attention within the global agriculture technology sector [

4,

5,

6]. Among the core technologies for agricultural robots, positioning systems play a pivotal role, serving as the fundamental enabler for autonomous navigation operations [

7,

8,

9].

In open-field environments, RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) enabled GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems) provide centimeter-level positioning accuracy, which has become the primary technical dependency for current agricultural robot navigation systems [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, in occluded environments, GNSS signals suffer from degradation or even loss of fixed solutions, leading to drastic declines in positioning accuracy that severely compromise the reliability of autonomous navigation. Therefore, achieving continuous and precise robot localization in weak or GNSS-denied environments has emerged as a key research focus in agricultural robotics [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Cao et al. [

23] proposed a neural network-based predictive MEMS-SINS error feedback correction method. This approach trains the neural network during GPS (Global Positioning System) availability and utilizes the trained model to predict MEMS-SINS errors during GPS outages. In four 50-second simulated GPS-denied experiments, the method achieved an average position error of 3.8m. Shen et al. [

24] proposed a Radial Basis Function-based Multilayer Perceptron-assisted Cubature Kalman Filter to compensate for position and velocity errors during GPS outages. In a 500-second GPS signal interruption test, the algorithm's mean square error below 23.11m. Liu et al. [

25] addressed the challenge of cumulative errors in MEMS-INS during GPS signal loss by developing a neural network-aided GPS/MEMS-INS integrated navigation system. Experimental simulations under GPS-denied conditions demonstrated that this approach outperformed traditional frameworks using Standard Kalman Filter and Unscented Kalman Filter, achieving approximately 65% improvement in velocity and positional accuracy. Zhang et al. [

26] proposed a BDS (BeiDou Navigation Satellite System) outage endurance method for agricultural machinery navigation. By designing a Self-Calibrating Variable-Structure Kalman Filter for BDS/INS data fusion, this approach maintains straight-line tracking accuracy within limited durations. In robotic platform trials, during 20-second simulated BDS outages, the method achieved an average lateral deviation of 0.31m on linear paths and an average positioning discrepancy of 0.77m between INS (Inertial Navigation System) and BDS on rectangular paths. However, cumulative errors inherent to the INS system limit its long-term operational viability. Wei et al. [

27] addressed the challenge of GNSS signal occlusion in orchard environments by implementing a Kalman Filter-based fusion framework integrating GNSS and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data. To mitigate motion-induced distortion in LiDAR scans, an odometry-aided correction method was applied, enabling autonomous navigation for agricultural robots. Experimental results demonstrated a mean lateral deviation of less than 11cm between actual and planned trajectories. However, the validity of GNSS signal availability during trials remains unverified, as the experiments did not isolate GNSS signals to quantify environmental signal degradation levels. Hu et al. [

28] proposed a laser-based localization method for agricultural robots, which achieves robot positioning by fusing ToF (time-of-flight) measurements from laser scanning with point cloud features acquired by a LiDAR receiver. Experimental results demonstrated that the average maximum deviations during straight-line and curvilinear motion were 4.1cm and 6.2cm, respectively. This method is primarily applicable to GNSS-denied indoor environments such as hangars and greenhouses, requiring unobstructed visibility between the LiDAR and receiver. However, its effectiveness is limited in outdoor scenarios due to potential occlusions. The aforementioned research studies provide valuable insights into achieving continuous and precise robot localization in weak or GNSS-denied environments. However, they still face limitations such as relatively low localization accuracy and suboptimal stability.

To address the aforementioned issues, this study proposes a neural network-based SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm. The algorithm integrates the local accuracy of LiDAR-inertial odometry with the global stability of GNSS. It achieves multi-sensor observed pose coordinate system unification through coordinate system alignment preprocessing, optimizes SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) poses via outlier filtering and drift correction, and dynamically adjusts the weights of poses from distinct coordinate systems via a neural network according to the GDOP (Geometric Dilution of Precision). These mechanisms collectively enhance the robot's localization accuracy and stability in weak or GNSS-denied environments. A wheeled differential-drive robotic platform was developed to preliminarily validate the algorithm's performance. Furthermore, field experiments were conducted in actual orchard environments to investigate the algorithm's effectiveness under orchard terrain conditions and tree-obstructed scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algorithm Framework

The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm proposed in this study achieves continuous and precise positioning for robots in weak or GNSS-denied environments by integrating LIO-SAM (tightly-coupled lidar inertial odometry via smoothing and mapping) [

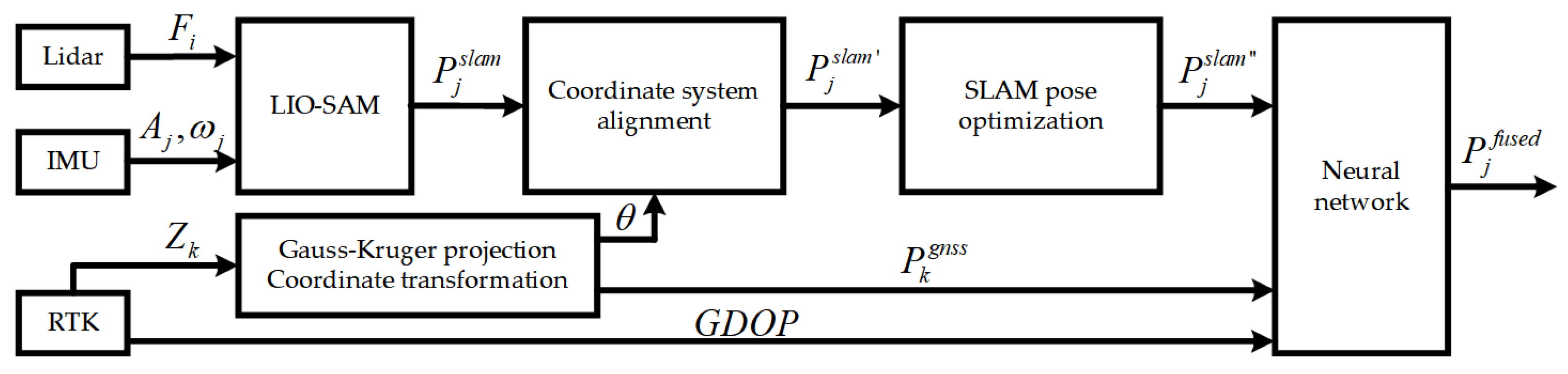

29] and dual-antenna RTK measured positioning and orientation data. This study adopts a loosely coupled approach, where the SLAM and GNSS subsystems operate independently. A neural network-based dynamic weight adjustment fusion localization algorithm was designed to perform data integration. The overall framework is illustrated in

Figure 1, with the corresponding nomenclature provided in Table 1. First, the point cloud data from LiDAR and the acceleration and angular velocity from IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) are coupled into LIO-SAM to obtain the observed pose of the center point of the drive wheel axis in the SLAM coordinate system. Subsequently, the real-time dynamically measured positioning orientation data from the dual antennas are subjected to Gauss-Kruger projection and coordinate transformation to obtain the observed pose of the center point of the drive wheel axis in the GNSS coordinate system. Then, coordinate system alignment preprocessing is implemented to unify the coordinate system of multi-sensor observed poses, followed by outlier filtering and drift correction to optimize the SLAM poses. Finally, the observed poses from two distinct coordinate systems and the GDOP are fed into the neural network model to dynamically adjust the optimization weights of each observed pose, thereby outputting the fused pose.

2.2. SLAM/GNSS Fusion Localization Algorithm

2.2.1. LiDAR-Inertial Odometry

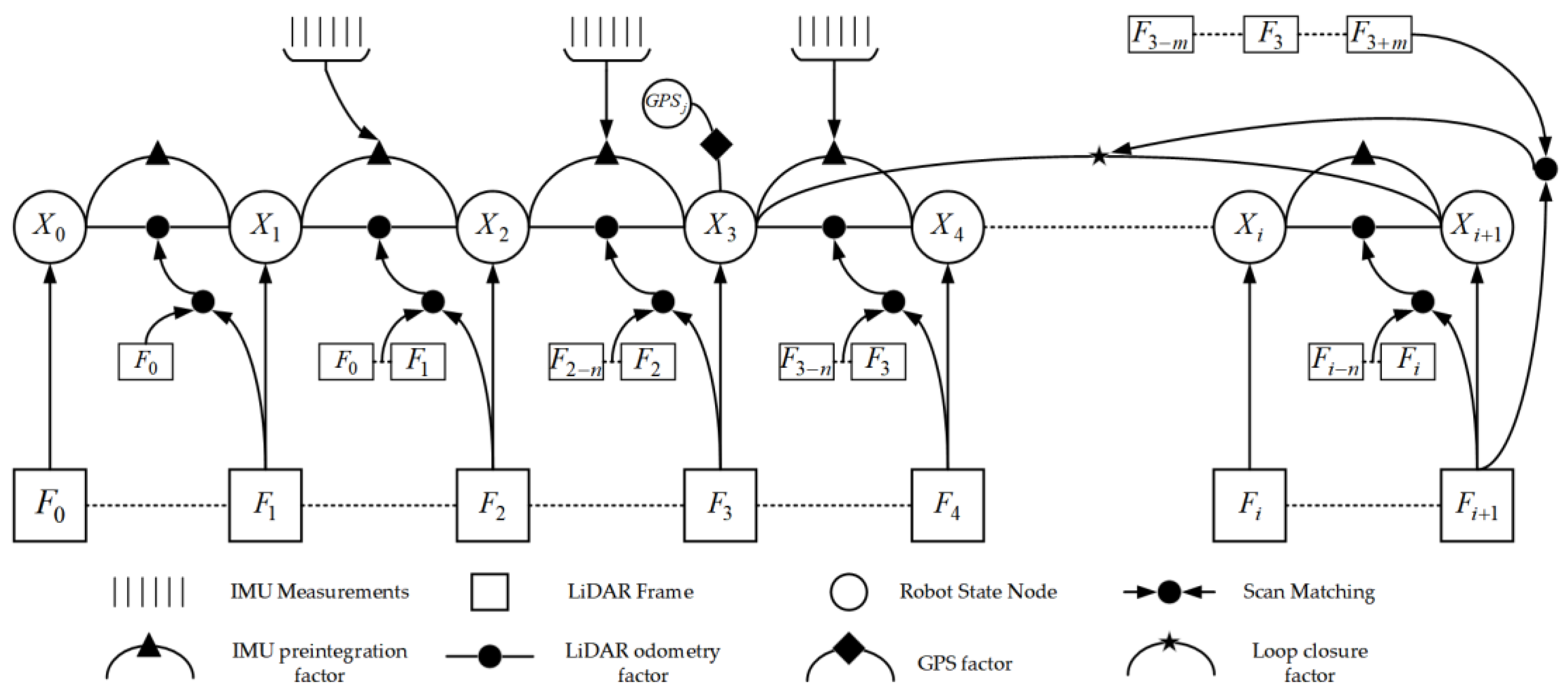

The research employs the LIO-SAM algorithm for state estimation. This algorithm constructs a factor graph optimization framework, as shown in

Figure 2, incorporating four key factors: IMU preintegration factor, LiDAR odometry factor, GPS factor, and loop closure factor. By applying nonlinear optimization methods to optimize the factor graph, the system achieves globally consistent robot poses, enabling high-precision state estimation and map construction.

The IMU pre-integration factor efficiently computes the relative motion increments between consecutive LiDAR keyframes i and i+1 by pre-integrating IMU data. These increments include positional increment

velocity increment

and rotational increment

, which are incorporated as constraints into the factor graph for optimization. The IMU pre-integration formulation is expressed as follows:

where g is the acceleration of gravity;

is the time interval between two neighboring keyframes;

and

are the velocities at the moments i and i+1;

and

are the positions at the moments i and i+1;

is the rotation matrix transpose at the moment i; and

is the rotation matrix at the moment i+1.

The LiDAR odometry factor first extracts features from preprocessed point cloud data using a curvature-based method, categorizing them into edge features and planar features, while introducing the concept of LiDAR keyframes. A sliding window approach is then employed to construct a point cloud map containing a fixed number of recent LiDAR scans. Finally, the point-to-edge distance

and point-to-plane distance

are utilized to formulate pose estimation equations.

where k, u, v and w are feature indices in the corresponding set;

,

and

are points on edge features; and

,

,

and

are points on planar features.

The GaussNewton method is used to solve for the optimal transformation by minimizing:

where

is the pose at moment i+1;

is the edge feature transformed to the world coordinate system; and

is the planar feature transformed to the world coordinate system.

The relative pose transformation between two adjacent keyframes is computed:

where

is the pose at moment i.

The GPS factor provides global positional constraints to the system by integrating GPS measurement data. Upon receiving GPS observations, the data is transformed into a local Cartesian coordinate system. When new nodes are added to the factor graph, the corresponding GPS factor is associated with these nodes to establish spatial constraints.

The loop closure factor employs a simple yet effective Euclidean distance-based detection method. The algorithm first searches historical keyframes to identify candidate loop closure frames that are temporally distant but spatially proximate. Subsequently, scan-to-map optimization is performed to estimate the relative pose transformation between the current keyframe and the candidate frame. This transformation is then incorporated as a loop closure factor into the factor graph for global trajectory optimization.

2.2.2. Coordinate System Alignment

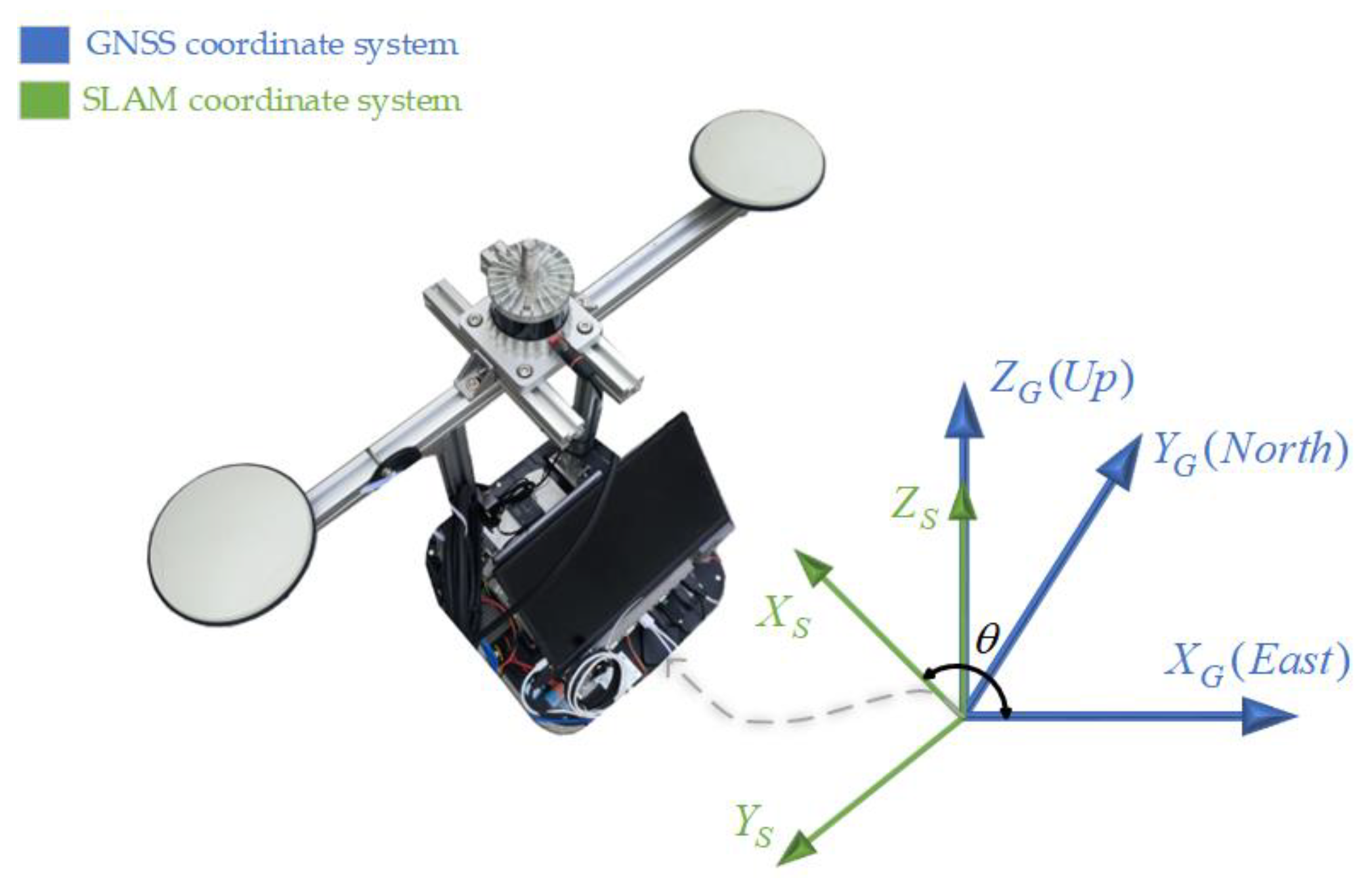

The SLAM coordinate system is defined with its origin at the initial position of the center point of the drive wheel axis. Its positive X-axis aligns with the robot's forward direction, while the positive Y-axis is oriented towards the robot's left side following the right-hand rule. The GNSS coordinate system shares the same origin but adopts an ENU (East-North-Up) frame convention, with the positive X-axis pointing to geodetic east and the positive Y-axis to geodetic north. The arbitrary initial orientation of the robot typically results in a fixed angular deviation θ about the Z-axis between the SLAM and GNSS coordinate systems, as shown in

Figure 3. To enable fusion of observed poses from these two distinct coordinate systems, coordinate system alignment is required.

During the system initialization phase, the initial heading angle θ is obtained through dual-antenna RTK measurements. The SLAM coordinate system is then rotated about the Z-axis by -θ to align with the GNSS coordinate system, resulting in an intermediate coordinate system MID that serves as the base coordinate system for SLAM. By establishing the coordinate transformation relationship from the SLAM coordinate system to the MID coordinate system, positional coordinates in the SLAM coordinate system can be transformed into the MID coordinate system, thereby achieving unification of the coordinate system for multi-sensor observed poses. The transformation is formulated as follows:

where

,

and

are the position coordinates under the SLAM coordinate system;

,

and

are the position coordinates under the MID coordinate system; and

is the rotation matrix from the SLAM coordinate system to the MID coordinate system.

2.2.3. SLAM Pose Optimization

During the implementation of the LIO-SAM algorithm for simultaneous localization and mapping, sporadic localization outliers may emerge in the LiDAR-inertial odometry. These localization outliers, characterized by abrupt pose jumps at specific timestamps, often result from dynamic object interference, sensor noise, or feature matching errors. These localization outliers must be filtered out to enhance the system's temporal continuity and operational stability. The pose outlier detection proceeds by first computing the Euclidean displacement between the current and previous poses in the SLAM coordinate frame. If this displacement exceeds a predefined threshold, the current pose is identified as an outlier. The system then substitutes the outlier with a linearly extrapolated pose derived from the previous pose data, as formalized below:

where

,

and

are the x, y coordinates and heading angle at the current moment;

,

and

are the x, y coordinates and heading angle at the previous moment;

,

and

are the rate of change of x, y coordinates and heading angle at the previous moment; and

is the time interval between the current moment and the previous moment.

GNSS data is not entered into the LIO-SAM framework because LIO-SAM does not fully utilize GNSS information [

30]. The radar inertial odometers may have accumulated errors due to drift during long time operation of the system. When the quality of the GNSS signal is high, the drift of the radar inertial odometer can be suppressed by using the coordinate data under the GNSS coordinate system as a global position constraint, thus reducing the cumulative error and improving the stability of the system. When RTK has a fixed solution and the GNSS signal quality is high, calculate the difference between the pose in the GNSS coordinate system and the pose in the SLAM coordinate system. When the difference exceeds the set distance threshold or angle threshold, correct the position coordinates in the SLAM coordinate system. Since this is designed for wheeled robots moving on a plane, we only consider distance deviations in the X and Y directions and heading angle deviation. The correction formula is as follows:

where

,

and

are the x, y coordinates and heading angles after correction;

,

and

are the x, y coordinates and heading angles before correction; and

,

and

are the x, y coordinates and heading angle differences.

2.2.4. Neural Network-Based Dynamic Weight Adjustment

LIO-SAM assigns fixed observation weights to both GNSS and LiDAR odometry [

30]. However, in practical scenarios, the signal quality of GNSS significantly differs between open and obstructed environments. The fixed-weight strategy fails to adequately account for the environmental sensitivity of GNSS signal quality, resulting in high-quality observations not being fully leveraged. Given the powerful adaptive and nonlinear mapping capabilities of neural networks, this study proposes a neural network model with dynamic weight adjustment. It adaptively adjusts the weights of poses from two distinct coordinate systems based on the magnitude of GDOP through end-to-end training, aiming to achieve the fusion of SLAM and GNSS poses.

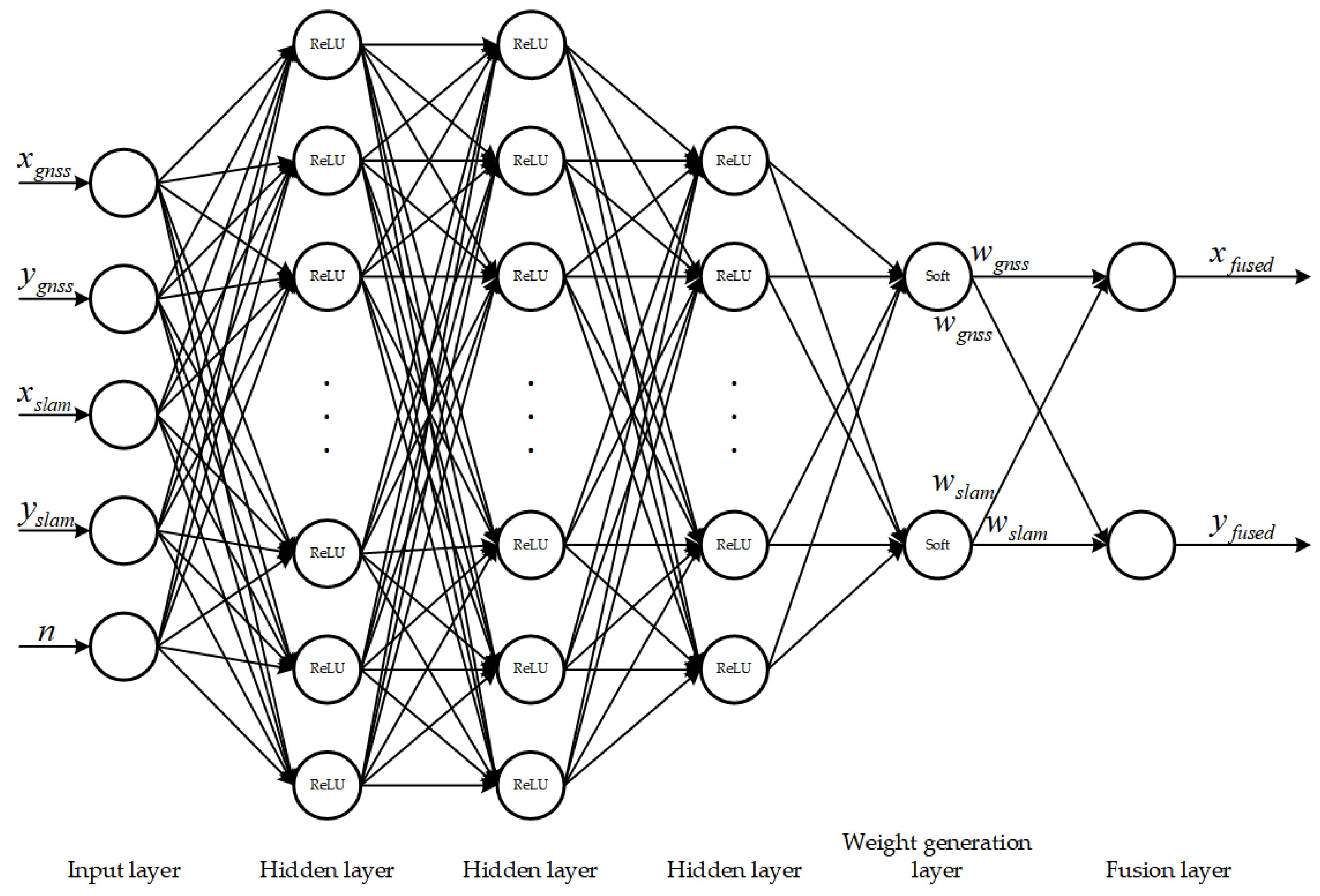

The structure of the neural network model is shown in

Figure 4. The input layer contains 5-dimensional features: the 2D SLAM position coordinates after preprocessing of coordinate system alignment, 2D GNSS position coordinates, and the GDOP. The first and second hidden layers are fully connected layers with 128 neurons each, using the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) as the activation function for feature extraction. The third hidden layer is also a fully connected layer with 64 neurons and ReLU activation, designed to further compress features. The fourth weight generation layer is a fully connected layer with 2 neurons, employing the Softmax function as the activation function to output normalized weights for GNSS and SLAM poses. The fifth fusion layer is a parameter-free mathematical operation layer that performs weighted summation of SLAM and GNSS position coordinates to output the fused position coordinates. The fusion formula is as follows:

where

is the weight of GNSS position;

is the weight of SLAM position;

and

are the position coordinates in GNSS coordinate system;

and

are the position coordinates in SLAM coordinate system; and

and

are the fused position coordinates.

This study adopts the MAE (Mean Absolute Error) as the loss function, which computes the mean absolute error

between the fused position coordinates and the ground truth position coordinates. The mathematical formulation is defined as follows:

where

is the fusion position coordinate of the i-th sample;

is the ground truth position coordinate of the i-th sample; and N is the total number of samples.

The training dataset was collected in real-world environments by controlling the robot to maneuver repeatedly between open and obstructed areas. During this process, 5-dimensional input data were continuously recorded, while 2-dimensional ground truth output data were acquired using a total station. After temporal synchronization, the raw data were processed to create a custom dataset, which was then split into 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 32, and trained for 100 epochs. The ReduceLROnPlateau strategy was applied for learning rate decay.

Finally, the fused heading angle is obtained by performing a weighted summation of the SLAM and GNSS heading angles. The fusion formula is defined as follows:

where

is the heading angle in the GNSS coordinate system;

is the heading angle in the SLAM coordinate system; and

is the fused heading angle.

2.3. Robotic Platform Experiments

2.3.1. Experimental Platform

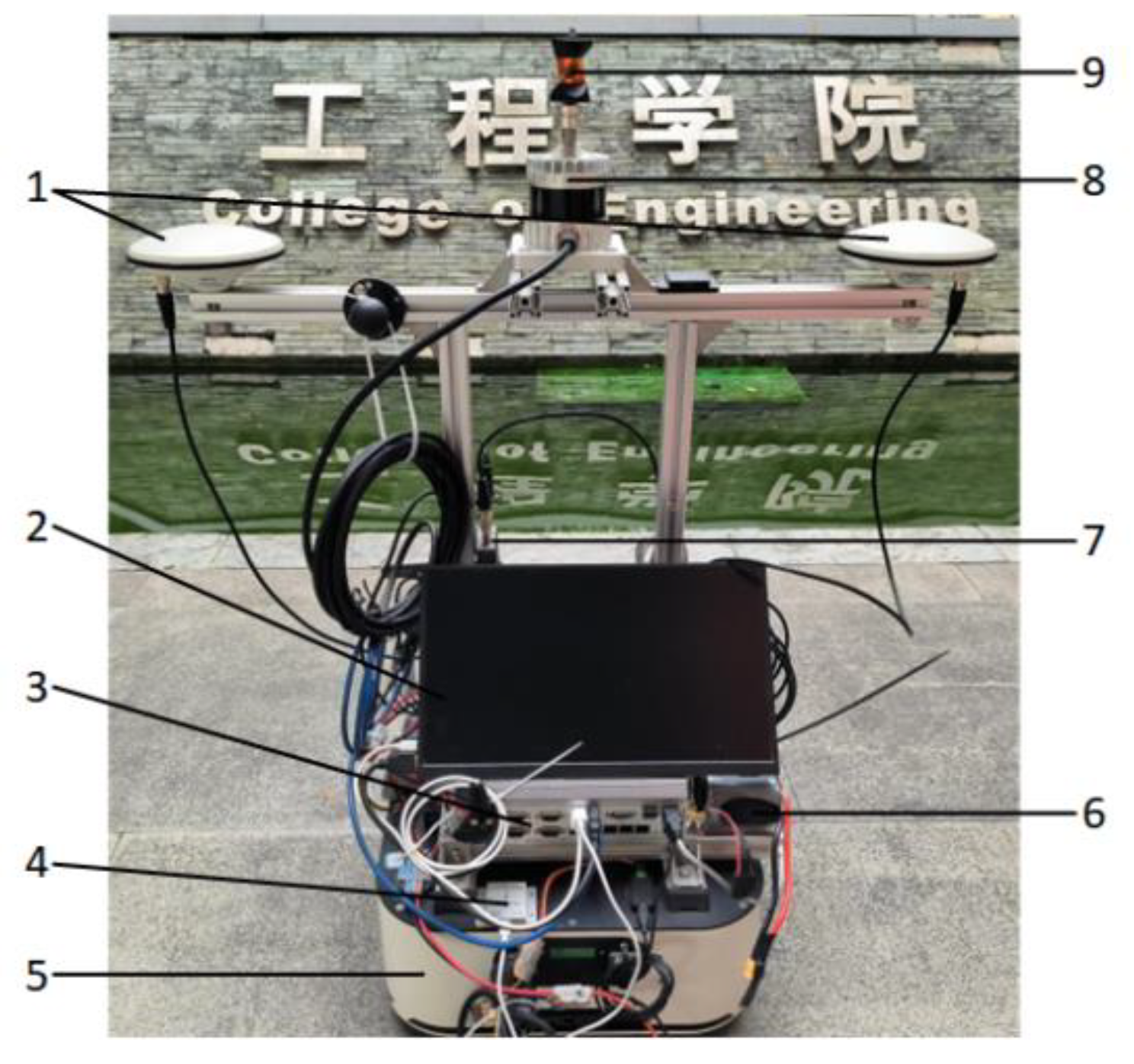

To preliminarily validate the performance of the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm, a robotic platform was developed based on the AgileX TRACER MINI wheeled differential chassis, with its physical prototype shown in

Figure 5. The hardware components of the platform include: Yentek G3750F-P4 embedded industrial computer (Intel i9-13900 processor, 32GB RAM); Unicorecomm UM982 satellite receiver (10Hz output frequency, horizontal positioning accuracy: 0.8cm +1ppm, heading accuracy: 0.1° per 1m baseline); WHEELTEC N100 IMU (400Hz output frequency, accelerometer/gyroscope/magnetometer linearity <0.1%); Ouster OS1 3D LiDAR (10Hz point cloud output, 128 scan lines); Display screen and 24V power supply. The software component consists of a localization system based on the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm. This system is developed within the ROS (Robot Operating System) framework using C++ and deployed on the embedded industrial computer. The satellite receiver's positioning and heading data, along with the IMU's inertial attitude data, are input to the localization system via serial port, while the LiDAR's point cloud data is streamed via Ethernet. The localization system employs neural networks to perform multi-sensor data fusion, continuously outputting the robot's fused pose.

2.3.2. Experimental Protocol

The robotic platform experiments were conducted at the College of Engineering, South China Agricultural University, with the experimental scenario shown in

Figure 6. A Leica MS60 total station in automated tracking mode was utilized to record the robot's ground truth position coordinates in real-time by tracking a prism mounted on the robot. The total station operates at a 10Hz measurement frequency, achieving a positioning error of 1mm within a 100m range. A rectangular path was planned with the starting point set in an area of high GNSS signal quality to facilitate coordinate system alignment during the system initialization phase. The robot was remotely controlled to approximately follow the predefined path, transitioning from GNSS-available zones to GNSS-denied zones, then back to GNSS-available zones. During the robot's walking process, the position coordinates in GNSS coordinate system, position coordinates in SLAM coordinate system and fused position coordinates output from the localization system are recorded in real-time. Three repeated trials were conducted under identical experimental conditions. Following temporal synchronization and uniform time sampling of the data, the following metrics were calculated: the average position deviation

throughout the whole process, the average position deviation

in areas of high GNSS signal quality, the average position deviation

in transitional zones experiencing signal degradation or recovery, the average position deviation

in GNSS-denied environments, and the average velocity

. These metrics were used to evaluate the localization accuracy and stability of the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm.

2.4. Orchard Experiments

2.4.1. Experimental Platform

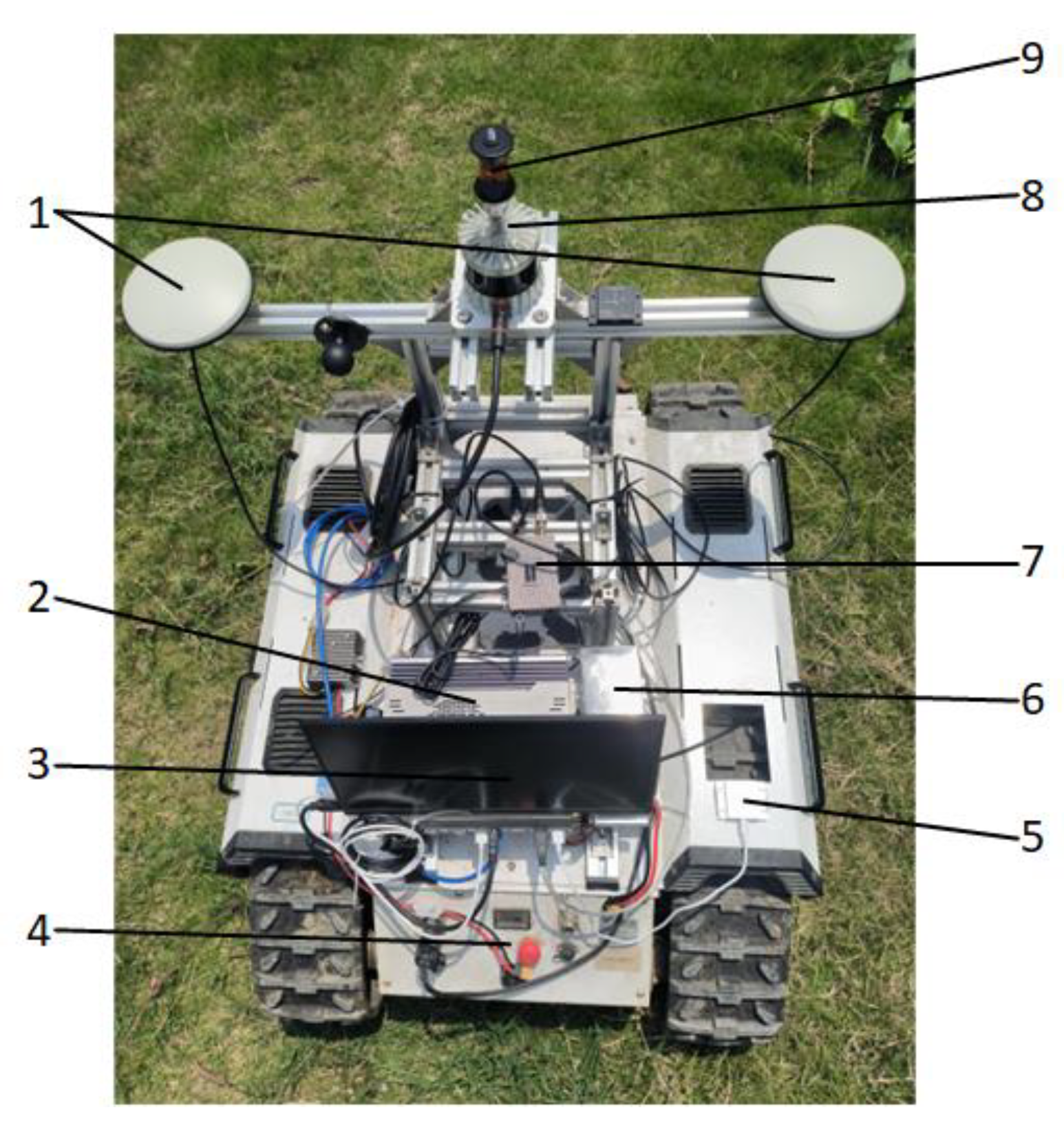

To investigate the operational performance of the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm in actual orchard terrains and tree-obstructed environments, the aforementioned software and hardware systems were ported to an AgileX BUNKER tracked differential chassis. Its key technical specifications are summarized in

Table 2, and the physical prototype is shown in

Figure 7.

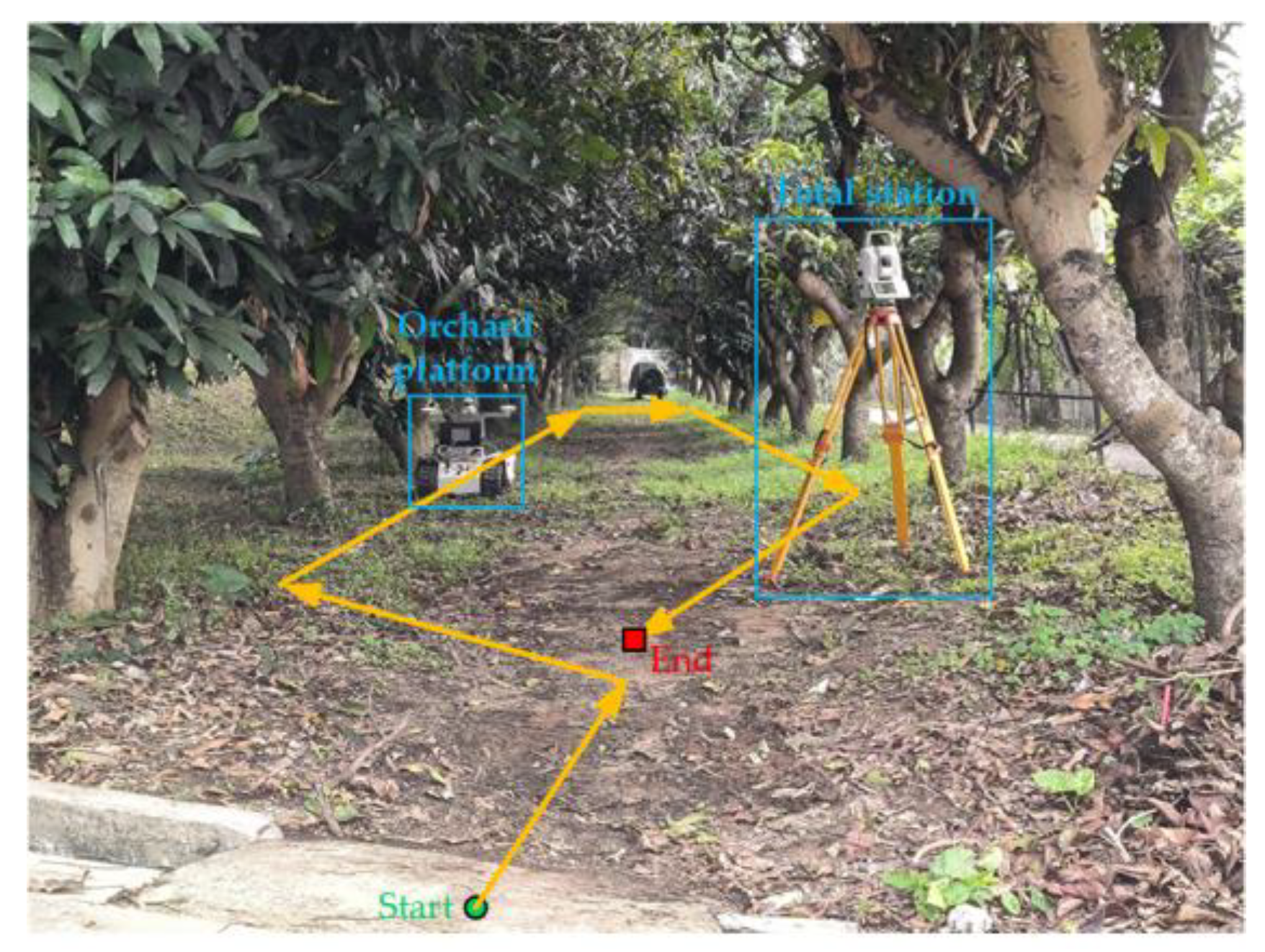

2.4.2. Experimental Protocol

The orchard experiments were conducted at the Horticultural Teaching and Research Base of South China Agricultural University, with the experimental scenario depicted in

Figure 8. A rectangular path was planned with the starting point positioned in a GNSS high-signal-quality area to facilitate coordinate system alignment during initialization. The robot was remotely controlled to approximately follow the predefined path. Throughout the traversal, both the fused position coordinates from the localization system and the ground truth position coordinates from the total station were recorded in real-time. Three repeated trials were conducted under identical experimental conditions. Following temporal synchronization and uniform time sampling of the data, the following metrics were calculated: the average position deviation

throughout the whole process, the average position deviation

in areas of high GNSS signal quality, the average position deviation

in transitional zones experiencing signal degradation or recovery, the average position deviation

in GNSS-denied environments, and the average velocity

. These metrics were utilized to evaluate the localization accuracy and stability of the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm in actual orchard terrains and tree-obstructed environments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Robotic Platform Experimental Results

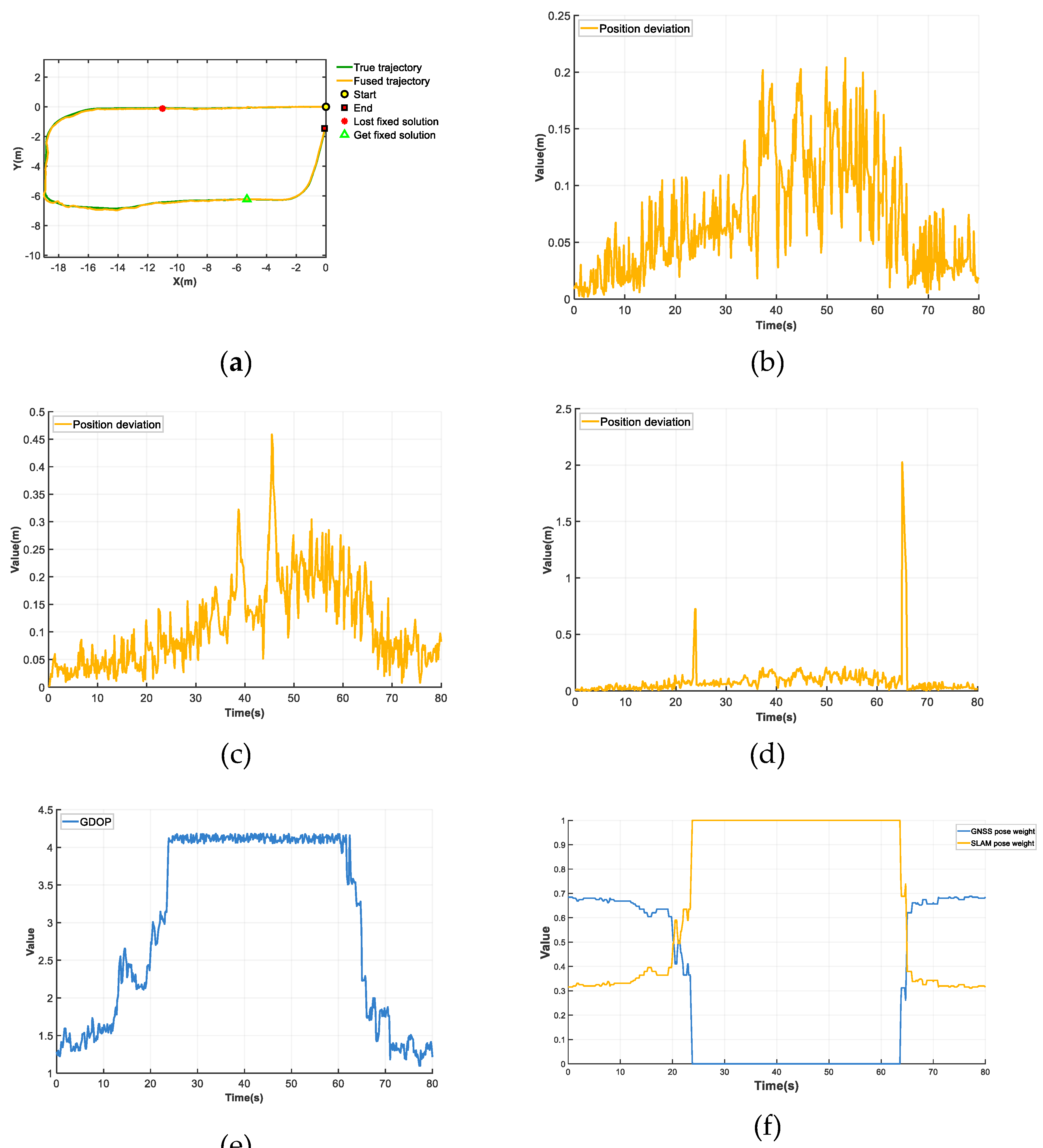

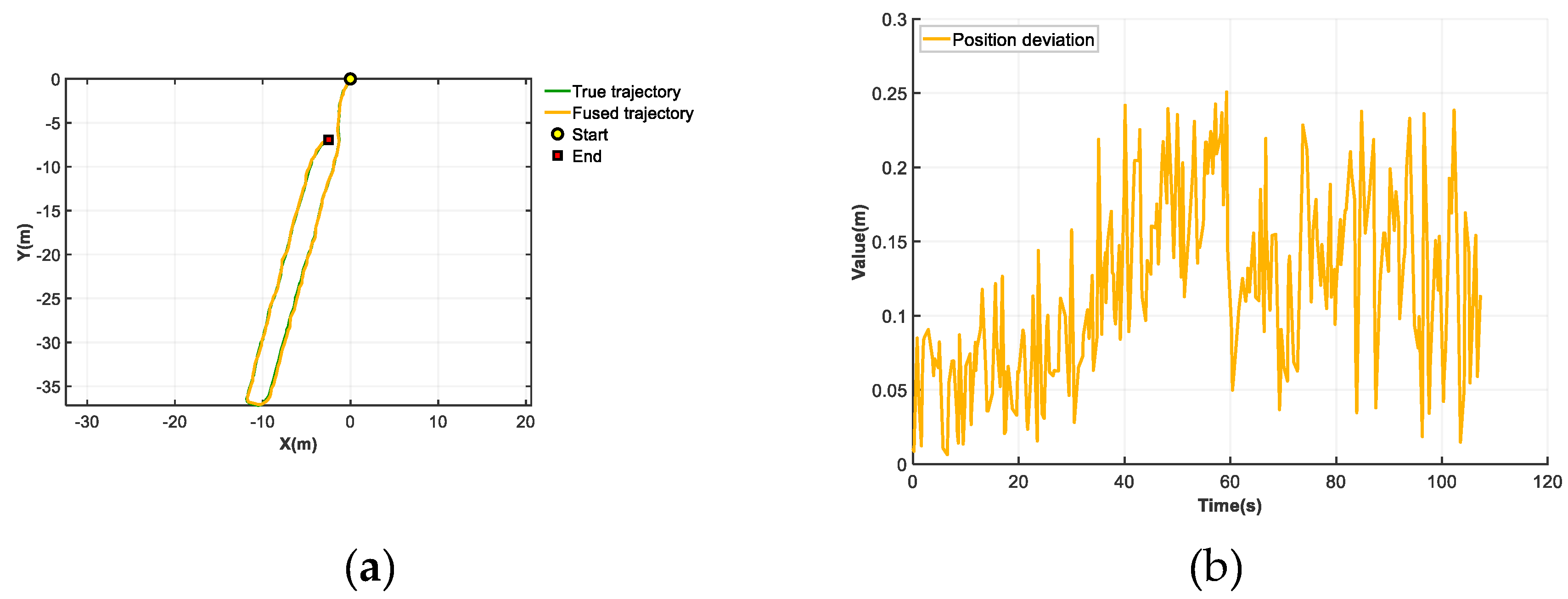

The fused trajectory versus the ground truth trajectory from the robotic platform experiment 1 is shown in

Figure 9 (a). The position deviation over time for the localization system employing the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm is shown in

Figure 9 (b). The position deviation over time for the SLAM localization subsystem without pose optimization is shown in

Figure 9 (c). The position deviation over time for the fixed-weight fusion localization system is shown in

Figure 9 (d). The GDOP over time is shown in

Figure 9 (e), while the time-varying weights assigned to SLAM and GNSS poses are shown in

Figure 9 (f).

During the intervals of 0-19.8s and 65-80s, the GDOP remained low, indicating high GNSS signal quality. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm optimized the SLAM pose through outlier filtering and drift correction. The weights assigned to GNSS and SLAM poses showed not much difference and remained stable, resulting in an average positional deviation of 0.03m in these segments. During the 19.9s-23.5s interval, the GDOP gradually increased, indicating a progressive degradation in GNSS signal quality. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm dynamically adjusted the weights via the neural network, with the GNSS pose weight continuously decreasing while the SLAM pose weight correspondingly increased. This resulted in an average positional deviation of 0.06m for this segment. During the 60.7s-64.9s interval, the GDOP gradually decreased, indicating a progressive improvement in GNSS signal quality. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm dynamically adjusted the weights via the neural network, with the SLAM pose weight continuously decreasing while the GNSS pose weight correspondingly increased. This resulted in an average positional deviation of 0.08m for this segment. During the 23.8s-60.5s interval, the GDOP exceeded 4, indicating virtually no GNSS signals. The RTK fixed solution was lost, and the GNSS pose weight was set to 0, while the SLAM pose weight was assigned a value of 1. The system thus relied solely on LiDAR odometry for localization. This segment exhibited an average positional deviation of 0.11m with no significant dispersion in localization error, demonstrating stable performance over extended durations.

The results from three repeated trials are summarized in

Table 3. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm achieved the following metrics:

= 0.07m,

= 0.04m,

= 0.06m,

= 0.10m,

= 0.57m/s. Compared to the SLAM algorithm without pose optimization, the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm reduced the whole process average position deviation by 37%. Compared to the fixed-weight fusion localization algorithm, the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm achieved a 74% reduction in average position deviation during transitional segments with GNSS signal degradation or recovery. Experimental results on the robotic platform demonstrate the superior positioning accuracy and stability of the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm in weak or GNSS-denied environments.

3.2. Analysis of Orchard Experimental Results

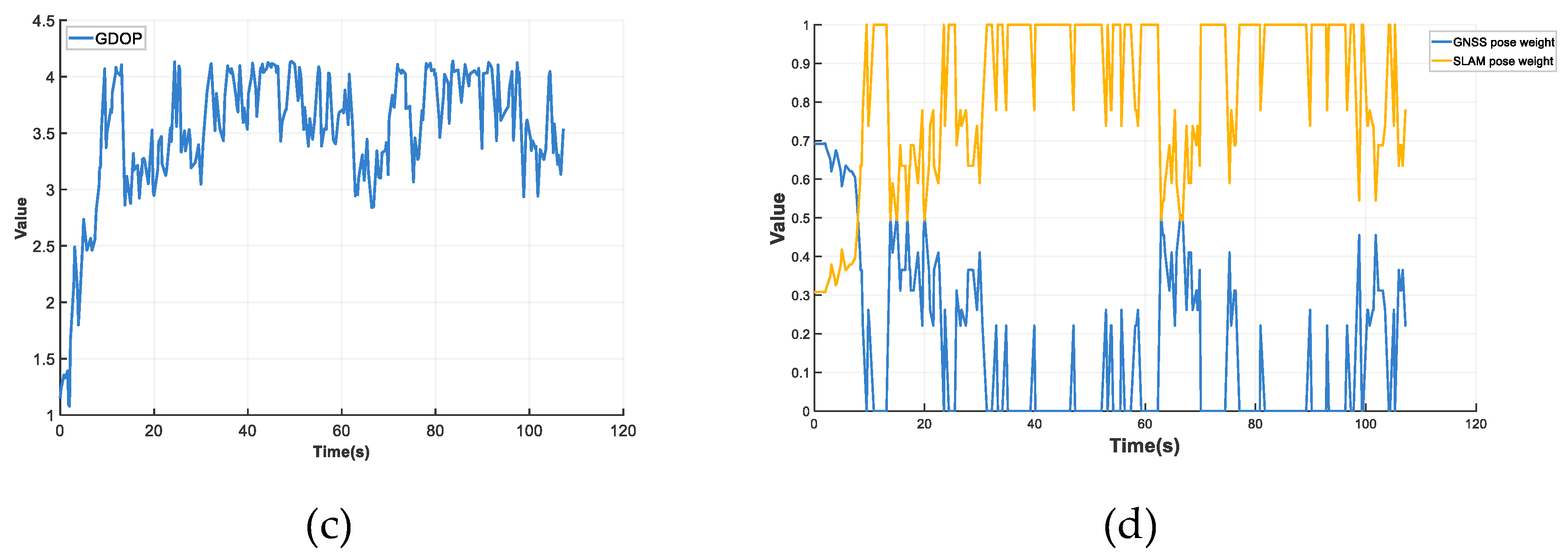

The fused trajectory versus the ground truth trajectory from the orchard experiments 1 is shown in

Figure 10 (a). The deviation d between the fused positions and ground truth positions over time is shown in

Figure 10 (b). The GDOP over time is shown in

Figure 10 (c), while the time-varying weights assigned to SLAM and GNSS poses are shown in

Figure 10 (d).

During the 0-9.5s interval, the robot transitioned from an open area to a tree-obstructed zone. The GDOP gradually increased, indicating a progressive degradation in GNSS signal quality. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm dynamically adjusted the weights via the neural network, resulting in a continuous decrease in the GNSS pose weight and a corresponding increase in the SLAM pose weight. During the 9.8s-107.3s interval, the robot operated entirely within a tree-obstructed environment. The GDOP fluctuated between 2.8552 and 4.1664, indicating low and highly fluctuating GNSS signal quality. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm dynamically adjusted the pose weights via the neural network, with both GNSS and SLAM weights continuously adapting to real-time GNSS signal quality variations.

The results from three repeated trials are summarized in

Table 4. The SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm achieved the following metrics:

= 0.12m,

= 0.06m,

= 0.11m,

= 0.14m,

= 0.55m/s. Experimental results in the orchard demonstrate that the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm maintains high localization accuracy and stability even under conditions of low and highly fluctuating GNSS signal quality, meeting the operational requirements of most agricultural robots.

3.3. Discussion

The requirement to position the robot's starting point in high GNSS signal quality areas for coordinate system alignment during initialization imposes limitations on the applicability of the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm across diverse operational scenarios.

Since the total station cannot directly provide ground truth heading angles for tracked mobile devices, this study omitted heading angle deviation as an experimental metric. Future research could focus on acquiring accurate ground truth heading angles for robots in GNSS-denied environments to further analyze the heading angle accuracy of the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm.

Typical agricultural machines operate at a speed of 1 to 1.5 m/s, but experimental average speed described above was only about 0.5 m/s. At velocities exceeding 1 m/s, the algorithm may sacrifice positional precision to maintain real-time performance. Subsequent studies can add high-speed testing scenarios to verify the accuracy and stability of the algorithm at typical farm machine operating speeds.

In real agricultural scenarios, dust generated during robotic operations and frequent precipitation during the rainy season can have an impact on the point cloud quality of the LiDAR. Suspended particulate matter in the dust scatters the laser light, resulting in noticeable noise. Raindrops reflect and absorb the laser light, resulting in anomalous increases or disappearances in the point cloud. The distortion of LiDAR point cloud data will affect the effectiveness of the algorithm to a certain extent, so in subsequent research we need to consider how to eliminate these effects as much as possible to improve the stability of the algorithm in harsh environments. For example, a waveform recognition algorithm can be used to analyze the reflectivity size and orientation of the noise and set an appropriate threshold to filter the noise. Or a deep learning based denoising method can be used to develop a noise filtering network based on semantic information.

4. Conclusions

To address the issue of agricultural robot loss of control caused by GNSS signal degradation or loss in complex agricultural environments such as farmland and orchards, this study proposes a neural network-based SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm. It achieves multi-sensor observed pose coordinate system unification through coordinate system alignment preprocessing, optimizes SLAM poses via outlier filtering and drift correction, and dynamically adjusts the weights of poses from distinct coordinate systems via a neural network according to the GDOP. These mechanisms collectively enhance the robot's localization accuracy and stability in weak or GNSS-denied environments.

To preliminarily validate the performance of the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm, robotic platform experiments were conducted. The experimental results demonstrate that, at an average speed of 0.57m/s, the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm achieves an overall average position deviation of 0.07m, with average position deviation of 0.04m in areas of high GNSS signal quality, 0.06m in transitional zones experiencing signal degradation or recovery, and 0.10m in fully GNSS-denied environments. Compared to the SLAM algorithm without pose optimization, the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm reduced the whole process average position deviation by 37%. Compared to the fixed-weight fusion localization algorithm, the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm achieved a 74% reduction in average position deviation during transitional segments with GNSS signal degradation or recovery. These results validate the superior positioning accuracy and stability of the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm in weak or GNSS-denied environments.

To investigate the operational performance of the SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm in actual orchard terrains and tree-obstructed environments, orchard field experiments were conducted. The experimental results demonstrate that, at an average speed of 0.55m/s, the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm achieves an overall average position deviation of 0.12m, with average position deviation of 0.06m in high GNSS signal quality zones, 0.11m in transitional sections under signal degradation or recovery, and 0.14m in fully GNSS-denied environments. These results validate the proposed SLAM/GNSS fusion localization algorithm maintains high localization accuracy and stability even under conditions of low and highly fluctuating GNSS signal quality, meeting the operational requirements of most agricultural robots.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z., J.H., J.W., and Y.C.; methodology, H.Z., J.H., J.W., and Y.C.; validation, H.Z., J.W., and Y.C.; formal analysis, H.Z., Y.C., J.W., and Z.L.; investigation, H.Z., J.W., and F.X.; resources, H.Z. and J.H.; data curation, H.Z., J.W., Y.C., Z.L., J.H., and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z., J.W., Y.C., and F.X.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., J.W., and J.H.; visualization, H.Z., J.W., Y.C., and P.W.; supervision, J.H.; project administration, H.Z. and J.W.; funding acquisition, J.H. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Special Fund for Hunan innovative province construction project (2023NK1020), Key R&D Plan Project of Shandong Province (2022SFGC0202).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Luo, X.W; Hu, L; He, J; Zhang, Z.G.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhang, W.Y.; Liao, J; Huang, P.K. Key Technologies and Practice of Unmanned Farm in China[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2024, 40(1): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Z; Jiang, Y.X. Industrialization Trends and Multi-arm Technology Direction of Harvesting Robots[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery.2024, 55(10): 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Q.; Tang, S.Y.; Luo, X.F.; Dong, J.W.; Xu, N. Research and Application Status of Path Planning for Agricultural Inspection Robots. Agric. Equip. Veh. Eng. 2025, 63, 18–24. [CrossRef]

- 4. Wang, N; Han Y.X; Wang, Y.X; Wang, T.H.; Zhang, M; Li, H. Research Progress of Agricultural Robot Full Coverage Operation Planning[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2022, 53(s1): 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M, Ji, Y.H.; Li S.C.; Cao R.Y.; Xu H.Z.; Zhang, Z.Q. Research Progress of Agricultural Machinery Navigation Technology[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2020, 51(4): 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhou, Z.Q. Current Status and Trends of Agricultural Robotics Development. Agric. Equip. Technol. 2024, 2025, 51(01).

- Chen, Y, Zhang, T.M; Sun, D.Z.; Peng, X.D.; Liao, Y.Y. Design and experiment of locating system for facilities agricultural vehicle based on wireless sensor network[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2015, 31(10): 190-197. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tang, G.Y.; Fu, Z.Y.; Deng, H.G.; Fan, J.N.; Wu, C.C. Research progress on autonomous agricultural machinery technology and automatic parking methods in China[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2025, 41(10): 15-27. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Gong, L.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y.M. Development Trends of Agricultural Robots[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2022, 53(7): 1-22,55. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.P.; Zhang, Z.G.; Luo, X.W; Wang, H; Huang, P.K.; Zhang, J. Design of automatic navigation operation system for Lovol ZP9500 high clearance boom sprayer based on GNSS[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2018, 34(1): 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Luo, X.W.; Zhao, Z.X.; Huang, P.S. Trajectory Tracking Control Method Based on Kalman Filter and Pure Pursuit Model for Agricultural Vehicle[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2009, 40(Z1): 6-12. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.C.; He, Z.B.; Xia, Z.Z.; Peng, J.Y.; Wu, T.H. Design of navigation immune controller of small crawler-type rape seeder[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2019, 35(7): 12-20. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.T.; Liu, B. Design and Path Planning of Agricultural Machinery Automatic Navigation System Based on GNSS[J]. Test Meas. Technol. 2024, 38, 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.T; Gao, L, Bai, X.P.; Li, T.C.; Liu, X.G. Review of research on automatic guidance of agricultural vehicles[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2015, 31(10): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.Y.; Zhou, J. Current Situation of Navigation Technologies for Agricultural Machinery[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2014, 45(9): 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.W.; Liao, J.; Hu, L.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Zang, Y.; Wang, P.; He, J. Research progress of intelligent agricultural machinery and practice of unmanned farm in China[J]. Journal of South China Agricultural University. 2021, 42(6): 8-17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.W.; Xu, Z.S.; Huang, Z.D.; Jing, J.S.; Niu, R.X. Inter-rows Navigation Method of Greenhouse Robot Based on Fusion of Camera and LiDAR[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2023, 54(3): 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Yousuf S, Kadri MB. Information Fusion of GPS, INS and Odometer Sensors for Improving Localization Accuracy of Mobile Robots in Indoor and Outdoor Applications[J]. Robotica. 2021; 39(2): 250-276. [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, Y.X,; Chen, Y.L.; Jin, C.Q.; Du, J. Development of autonomous navigation controller for agricultural vehicles[J]. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. 2020; 13(4): 70–76. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, Z.Y.; Yang, N.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, Y.W.; Feng, X.P. Research Progress and Prospects of Key Navigation Technologies for Facility Agricultural Robots[J]. Smart Agriculture. 2024, 6(5): 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ji, J.; Pan, D.; Zhao, L.J.; Li, M.S. Localization Method for Agricultural Robots Based on Fusion of LiDAR and IMU[J]. Smart Agriculture. 2024, 6(3): 94-106. [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Li, J.X.; Zhu, D.K.; Guo, J.; Su, B.F. GPS/INS navigation based on adaptive finite impulse response-Kalman filter algorithm[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2019, 35(3): 75-81. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J.; Fang, J.C.; Sheng, W.; Bai, H.X. Adaptive neural network prediction feedback for MEMS-SINS during GPS outage[J]. Journal of Astronautics. 2009, 30(06). [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J.; Cao, H.; Liu, J. Dual-optimization for a MEMS-INS/GPS system during GPS outages based on the cubature Kalman filter and neural networks[J]. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 2019, 133106222-106222. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Hao, L.L; Huang, S.J.; Zhu, S.Y. A New Study of Neural Network Aided GPS/MEMS-INS Integrated Navigation[J]. Journal of Geomatics Science and Technology. 2014, 31(04): 336-341. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Wang J; Zhang, Z.G.; He, J; Hu, L; Luo, X.W. Self-calibrating Variable Structure Kalman Filter for Tractor Navigation during BDS Outages[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery. 2020, 51(3): 18-27. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.F.; Li, Q.L.; Sun, Y.T.; Sun, Y.J.; Hou, J.L. Research on Orchard Robot Navigation System Based on GNSS and Lidar[J]. Journal of Agricultural Mechanization Research. 2023, 45(10): 55-61+69. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L; Wang, Z.M.; WANG P; HE J; JIAO J.K.; Wang C.Y.; Li, M.J. Agricultural robot positioning system based on laser sensing[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2023, 39(5): 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. LIO-SAM: Tightly-coupled Lidar Inertial Odometry via Smoothing and Mapping[J]. 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Pan, G.S.; Huang, F.X.; Wang, X.; Gao, W. LiDAR-IMU-RTK fusion SLAM method for large-scale environment[J]. Journal of Chinese Inertial Technology. 2024, 32(09): 866-873. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).