1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, the vision of integrating service robots into everyday home life has gained significant attention in both industry and academia. Technological forecasts and public discourse have repeatedly emphasized the transformative potential of robotics in domestic settings, suggesting that robots may eventually play a central role in assisting with day-to-day household activities [

1]. Despite this enthusiasm, real-world adoption remains relatively limited, and public acceptance continues to face numerous challenges.

A major obstacle lies in the general perception of robotics technology, particularly within the European context. Data collected from a large-scale survey conducted in 2012 revealed a rather skeptical attitude among citizens regarding the presence of robots in the home [

2]. While robots were widely acknowledged as useful in high-risk or dangerous situations—such as bomb disposal, industrial automation, or disaster response—there was considerable discomfort with the idea of robots engaging in personal or sensitive roles. For example, many survey participants expressed disapproval of robotic assistance in caregiving scenarios involving vulnerable populations like children, elderly individuals, or people with disabilities. In fact, only a small minority (13%) supported the idea of prioritizing robots for domestic functions such as cleaning and household maintenance.

Even within the robotics research community, there has long been a lack of consensus regarding what specific functions home-based robots should fulfill. The ambiguity stems from the complex and varied nature of home environments, where cultural, spatial, and interpersonal factors play significant roles. Some scholars, such as Pantofaru et al. [

3], have attempted to explore more defined use cases by focusing on home organization tasks—like tidying up and managing household storage. Their research indicated that robots could offer tangible benefits in these areas by reducing human effort and enhancing household efficiency. Similarly, Bell et al. [

4] examined scenarios in which robots could take on responsibilities typically associated with maintaining cleanliness and order in domestic settings.

Although few service robots have made a successful leap into the consumer market, their limited presence has nonetheless allowed researchers to investigate how users respond to such technologies in real-world conditions. One particularly insightful study by Bauwens et al. [

5] outlined the primary considerations that influence a user’s willingness to adopt robotic solutions at home. Their findings suggest that three interrelated factors determine acceptance:

Practical Usefulness: The robot must perform tasks that are clearly beneficial and simplify the user’s daily life.

Contextual Integration: The robot should fit seamlessly into the home’s physical layout, routine habits, and user expectations.

Cost-Effectiveness: The value provided by the robot must justify the investment, making affordability a significant factor in decision-making.

Despite these insights, many research initiatives have historically focused on individual components of robot design—such as mechanical engineering, navigation, or human-robot interaction—without adopting a truly interdisciplinary approach. As a result, these systems often fall short of addressing the holistic needs of real home users.

In this paper, we advocate for a more integrative and user-centered methodology for designing domestic service robots. Our approach is grounded in the belief that robots should not exist as separate, conspicuous machines, but instead should be embedded within familiar household objects. We refer to these augmented items as robjects—a portmanteau of “robot” and “object.” Robjects maintain the aesthetic and functional characteristics of everyday items while discreetly incorporating robotic capabilities.

The key advantage of robjects lies in their natural integration into the domestic environment. Since they adopt the physical and symbolic roles of pre-existing household objects, they are more likely to be accepted by users and to complement existing home ecosystems. Moreover, robjects are designed to enhance collaboration with humans, minimizing the demand for users to adapt to complex technologies. Instead, the focus shifts toward intuitive interaction, shared control, and adaptive behavior.

These design principles are not merely theoretical; similar ideas have already seen practical success in certain industrial and commercial applications. In

Section 2, we examine several existing systems that exemplify this hybrid approach. Later, in

Section 3, we introduce a concrete implementation of a robject and discuss preliminary results from our user studies, which shed light on the practical effectiveness and user response to our design.

Through this work, we aim to demonstrate that reimagining domestic robots as robjects—and adopting a holistic, interdisciplinary design philosophy—can accelerate both technological development and public acceptance, ultimately making service robotics a functional and welcomed component of everyday home life.

2. State of the Art

Research efforts in the field of domestic robotics have steadily evolved, with particular emphasis on embedding intelligence into home environments. One key focus has been enhancing smart home systems to recognize and adapt to user activities, facilitating more responsive and supportive interactions between residents and automated systems [

6]. Another central theme involves the integration of autonomous service robots into residential settings, particularly to assist aging populations and support independent living [

7].

Numerous European research initiatives have been launched to explore these challenges, often combining robotics with smart home technologies to assist elderly users. For example, the Robot-Era project [

8] focuses on developing a range of robotic platforms capable of operating both indoors and outdoors. These robots are designed to deliver personalized services within smart homes, enhancing the autonomy and safety of older adults.

The GiraffPlus project [

9] introduces a telepresence robot into a network of home sensors capable of monitoring user behavior and health indicators. By contextualizing sensor data, the system aims to provide meaningful insights and enable remote caregiving. Similarly, the ACCOMPANY project [

10] emphasizes companionship and support, building robotic systems that interact naturally with users while being fully integrated into intelligent environments. The project explores how such systems can improve emotional well-being and promote social inclusion.

Another significant initiative, MOBISERV [

11], investigates cutting-edge technologies aimed at enhancing the lifestyle of elderly individuals in both home and institutional settings. This project incorporates proactive health monitoring and lifestyle support. CompanionAble [

12] focuses on combining robotic systems with ambient intelligence to create caregiving environments that can reduce the burden on human caregivers. The HOBBIT project [

13] takes a more socially focused approach, creating an assistive robot designed to offer physical help while engaging in socially appropriate behavior to ensure user comfort and trust.

These projects, while diverse in their implementation, often share one common feature: their robots typically resemble human-like figures or anthropomorphic designs. This tendency stems from the desire to foster familiarity and trust, especially when assisting vulnerable populations such as the elderly. However, this also introduces complexity in terms of cost, social acceptability, and long-term user engagement.

Some projects take a broader approach, decoupling robotic systems from specific demographic applications. For instance, RUBICON [

14] investigates large-scale, adaptive sensor-actuator networks without anchoring their utility to a singular domain such as elder care. This flexible design allows for reconfigurable applications, including environmental control, user interaction, and automation, setting the stage for more modular and adaptable smart environments.

Interestingly, very few studies have focused on service robot interactions tailored specifically for children. An exception is the MOnarCH project [

15], which explores how small, mobile robots can engage with children in hospital settings. Despite its health care context, the insights on robot-child interaction design, emotional response, and usability are highly relevant to domestic scenarios. The MOnarCH robots, though still humanoid in appearance, provide valuable data on how young users perceive and interact with robotic companions.

In addition to technical research, there is a growing recognition of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in robotic development. Traditionally, engineering and computer science have dominated this field; however, new approaches increasingly involve artists, designers, and social scientists. A noteworthy example is the University of Hertfordshire’s Robot House project [

16], where artists lived alongside robotic systems in a smart home to study everyday human-robot interaction. This lived-in experimental setup offered profound insights into how design, behavior, and aesthetics influence user perception and acceptance of domestic robots. Such immersive, participatory research methods are paving the way for more user-centered and socially attuned robot design practices.

While many service robots developed in research labs fail to meet commercial expectations or focus only on niche aspects, a few notable exceptions have successfully transitioned into market-ready products. The Kiva Systems [

17], for example, revolutionized warehouse automation by focusing on collaboration with human workers and optimizing logistics. Baxter [

18], developed by Rethink Robotics, was designed as a safe, affordable, and flexible robotic coworker for manufacturing environments. Both of these systems emphasize human-robot collaboration, practical functionality, and economic viability rather than anthropomorphism or full autonomy.

These commercial successes align with the findings of Takayama et al. [

19], who observed that users generally respond more positively to robots that work *with* humans rather than *replacing* them. This collaborative dynamic is crucial, especially in domestic settings where emotional comfort, trust, and social interaction play vital roles.

Building on this principle, our research aims to extend the concept of cooperative robotics into child-centric domestic environments. Inspired by earlier studies that highlight tidying and home organization as meaningful tasks for robotic intervention [

3,

4], we propose the design of a robotic assistant specifically tailored to help children keep their rooms clean and organized. This approach not only addresses a common household challenge but also encourages children to engage with robotic systems in a playful, educational, and non-intrusive manner.

By merging insights from existing assistive robotics projects with child-centered interaction strategies, we aim to develop solutions that are both functionally effective and emotionally resonant. Our project contributes to the growing body of work focused on human-robot synergy within the home, with a unique emphasis on usability, subtlety, and user-driven design.

3. The Ranger Robot

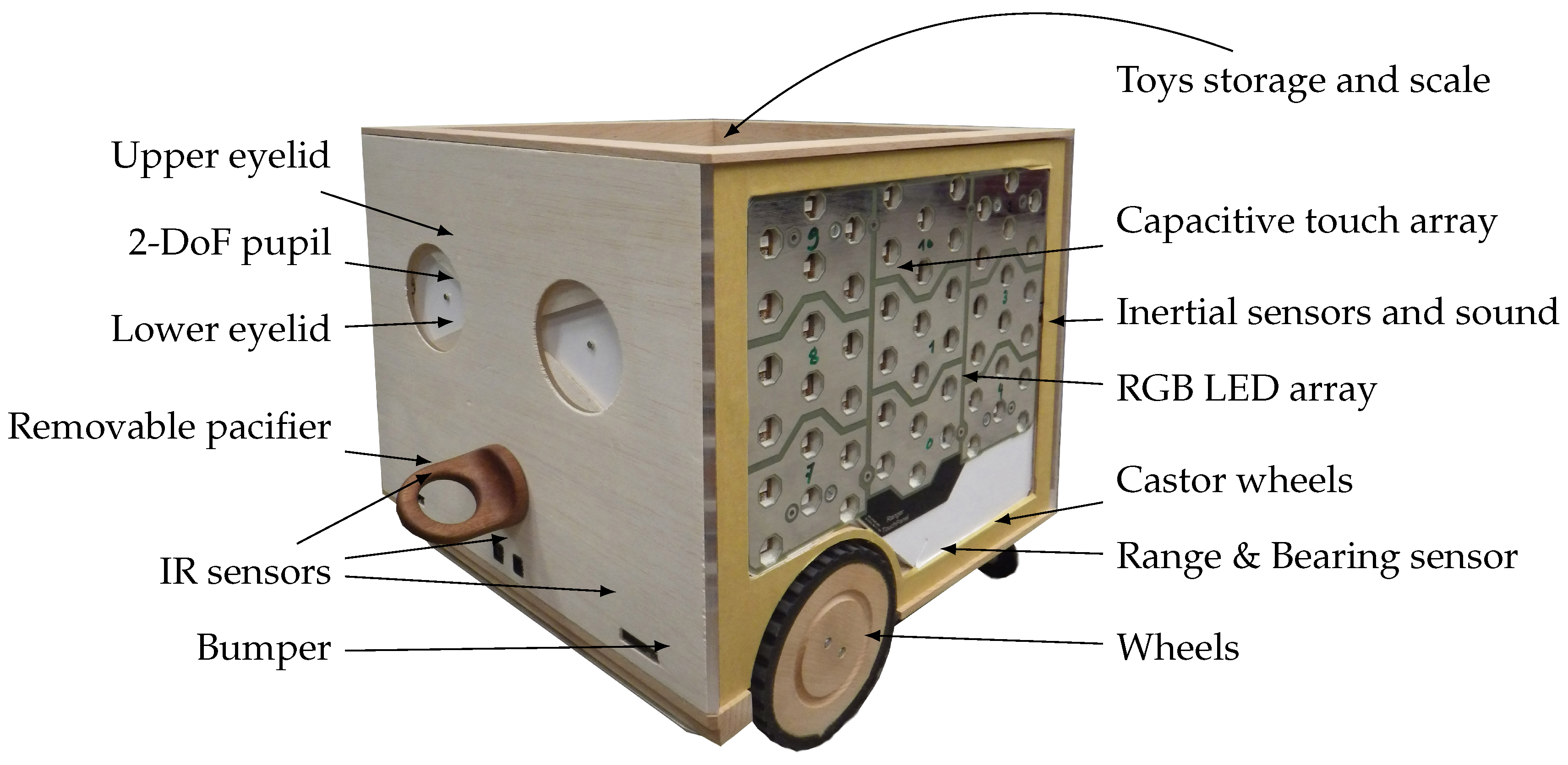

The

Ranger robot (see

Figure 1) is inspired by a familiar item found in many children’s rooms—a wooden toy storage box. This everyday object has been transformed into a

robject, meaning an object enhanced with robotic capabilities. The transformation was executed by a multidisciplinary team composed of mechatronics engineers, interaction designers, ethnographers, and roboticists. The primary aim of this

augmentation was to enhance the object’s functionality through robotics and mechatronics, while leveraging existing interactions and affordances to ensure smooth integration into a child’s environment. Ethnographic insights ensured the design would be acceptable within the family ecosystem.

The resulting

Ranger robot retains the original wooden box shape but is augmented with several technological components: wheels for mobility, mechanical eyes, inertial sensors, distance and ground sensors, a bumper, internal balance mechanisms, capacitive touch sensors, LED panels embedded behind the wooden surface, a sound system, eyeglasses, a detachable pacifier, and a range-and-bearing (R&B) system. These additions allow it to detect other Rangers, recognize its charging station, and identify a beacon indicating the designated play area (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 for details).

The physical design of the Ranger is optimized to foster interactions that motivate children to tidy their rooms. Instead of focusing solely on maximizing robotic functionalities, the design strategy emphasized ecosystem compatibility, child capabilities, and interaction quality. For instance, the robot is not equipped with arms, as these would unnecessarily increase cost and complexity. Instead, its functionality relies on interaction design principles that turn the child into an active participant. By retaining the recognizable features of a storage box, the Ranger increases its acceptance among both children and parents.

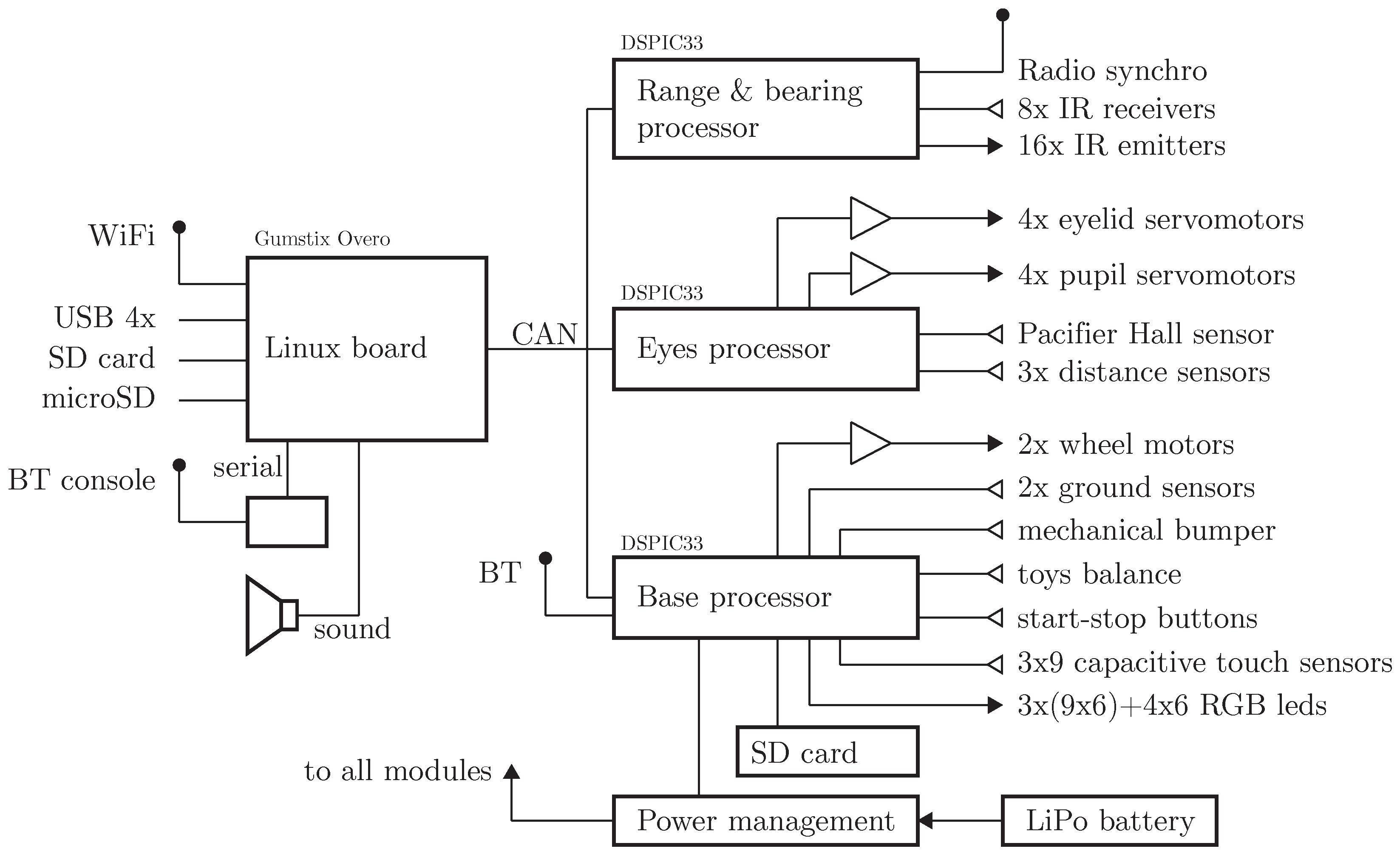

The internal system architecture is shown in

Figure 4. The Ranger robot operates with four processors: a primary embedded computer running Linux, responsible for wireless connectivity, data storage, and audio functions; and three microcontrollers connected via a CAN bus that handle real-time tasks such as power management, sensor input, and actuator control. The ASEBA framework [

20] is used for system control and serves as the interface with ROS-based controllers. ROS is also utilized for SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) and navigation.

Figure 3.

An image taken during user tests in families.

Figure 3.

An image taken during user tests in families.

Figure 4.

Electronic architecture of the ranger robot featuring four processors and USB-expandable Linux board.

Figure 4.

Electronic architecture of the ranger robot featuring four processors and USB-expandable Linux board.

The outer design includes a neutral wooden surface that serves as a projection screen, illuminated from behind by 186 RGB LEDs capable of creating a range of animated light patterns. The mechanical eyes, which lack digital screens, maintain a realistic and consistent appearance. Eyelids offer expressive capabilities and close when the robot is inactive. Eyeglasses of different colors serve both to protect the eye mechanisms and to distinguish between multiple Rangers assigned to different toy categories. The pacifier is made of wood and contains a magnet that allows it to be attached to the Ranger’s “mouth.” In some experiments, a PrimeSense RGB-D sensor connected via USB to the Linux board has been used for improved navigation and obstacle detection.

3.1. Ranger Use Scenario

The intended scenario involves a room setup where several Rangers are stored under a bed, each docked at a dedicated recharging station equipped with an R&B beacon (see

Figure 1). This space serves as their "home," where they typically remain in a dormant state with their eyes closed. Their activity is governed by a finite state machine, with a simplified version illustrated in

Figure 5.

Children interact with the Rangers using a controller device called the “collector,” which can hold up to three pacifiers. This collector, visible at the bottom center of

Figure 1, also includes a beacon. To begin playing, the child identifies which Ranger contains the desired toys by the color of its eyeglasses. The child then activates the Ranger by removing its pacifier. After placing the pacifiers into the collector, positioned in their play area, the selected Ranger wakes up and navigates toward the collector’s beacon.

When playtime is over, the child can return the Ranger to its station by placing the pacifier back in its mouth, prompting the robot to return home and enter sleep mode (and recharge). If the battery is low, the Ranger can autonomously return to its charging station. To encourage consistent interaction, the Ranger exhibits behaviors that engage the child emotionally—it appears "sad" and "hungry" when not filled with toys and shows "happiness" when toys are successfully deposited. This behavioral feedback loop fosters positive engagement and motivates children to keep their environment tidy.

3.2. Validation

To assess the viability, user acceptance, and initial interaction patterns associated with the ranger robot, we conducted a preliminary short-term field study involving 14 participating families, as described in [

21]. Each family had at least one child within the target age range, and all testing was conducted in a familiar home environment to ensure ecological validity.

In this study, a single ranger prototype was discreetly installed in the child’s bedroom. Meanwhile, a researcher engaged the family in a conversation in a separate room, without drawing attention to the robot’s presence. After this brief interaction, the family was invited to enter the child’s room, where they encountered the ranger for the first time in a naturalistic setting. The goal was to observe spontaneous interactions, reactions, and acceptance without external prompts or guidance.

Unbeknownst to the participants, the ranger robot was not operating autonomously but was instead being remotely controlled by an experimenter stationed in a third room. This was accomplished using a hidden camera system and followed a structured interaction script. The experimental protocol was based on the Wizard-of-Oz methodology [

22], in which a human operator simulates autonomous behavior to test interaction scenarios before full autonomy is implemented. This approach allowed for flexible control and ensured consistency across households while capturing genuine user responses.

The 14 families were divided into two experimental groups, each exposed to a different interaction paradigm. In the first group, the ranger robot exhibited a reactive behavior model: it remained stationary and waited to respond only after the child initiated an interaction. In contrast, the second group experienced a proactive ranger, which moved autonomously around the room, seeking out objects on the floor and attempting to engage the child more assertively.

Observational data and interaction metrics collected during the study demonstrated a high level of acceptance across both groups. Families responded positively to the presence and behavior of the ranger robot, with many children showing curiosity, willingness to interact, and in some cases, emotional attachment to the device. Notably, the results indicated that in households where the ranger exhibited reactive behavior, there was a marginally significant increase in the number of toys that were placed into or removed from the robot. This suggests that even with a minimalist behavioral strategy, the ranger was effective in promoting engagement and task-oriented interaction.

These findings underscore the importance of designing interaction models that align with user expectations and existing behavioral patterns. While proactive behavior may seem advantageous from a technological standpoint, it does not necessarily lead to higher user engagement. The study demonstrates that a less complex, reactive approach can yield comparable—if not better—results in certain scenarios.

The insights gathered from this initial study serve as a foundation for future work. The next phase of research will involve long-term deployments of the ranger robot in home environments resembling the configuration shown in

Figure 1. These extended trials aim to investigate how sustained interaction unfolds over time, particularly once the initial novelty has diminished. Understanding long-term usage patterns will be critical in refining the ranger’s behavior model, assessing its role in fostering routines such as tidying up, and evaluating its enduring impact on both children and their caregivers.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we introduced and explored the concept, design rationale, and initial validation of the ranger robot—a novel robotic storage solution designed to encourage children to participate in tidying up their rooms through interactive and playful engagement. By embedding robotic functionality into a familiar household object, the ranger exemplifies a new class of interactive systems referred to as robjects, or robotic objects. These systems blur the boundary between utility and companionship, embedding robotics into everyday life in a non-disruptive, user-centered manner.

The design philosophy behind ranger draws inspiration from successful industrial robotic systems that emphasize intelligent human-robot integration rather than complete autonomy. Such systems demonstrate that high performance can be achieved not merely through technological sophistication, but through strategic collaboration between human users and robotic assistants. This approach reduces the demands on hardware and software complexity while enhancing the system’s effectiveness and user acceptance. In particular, ranger aligns with the guiding principles identified by Bauwens et al. [

5], namely: practical utility, ecosystem integration, and economic value.

Our prototype implementation of ranger embodies these principles by addressing a practical household task—motivating children to clean up—while also seamlessly integrating into the domestic environment. Through its familiar form factor and intuitive interaction cues, ranger achieves strong affordance, making it immediately understandable and usable by children. The preliminary short-term study conducted with 14 families validated the concept, revealing a high level of acceptance among users and demonstrating that even minimalist behavior models can lead to meaningful interactions and task completion. These findings suggest that utility and engagement do not necessarily require high-level autonomy or complex artificial intelligence, but can instead arise from thoughtful interaction design and human-aware behaviors.

Furthermore, the study provided important insights into how different behavioral paradigms—reactive versus proactive—affect user engagement. Interestingly, the reactive model, in which the robot responds to the child’s actions rather than initiating its own, led to slightly more interactive behaviors from the children. This reinforces the importance of tuning robotic behavior to social and contextual expectations, especially when interacting with young users.

The broader implications of the ranger project extend beyond the scope of a single device. It offers a compelling case study in the development of context-sensitive, low-complexity robotic systems that provide real-world value. The success of ranger supports the viability of the robjects paradigm, which calls for a holistic design approach that harmoniously integrates mechatronics, interaction design, and social behavior modeling. Such integration is critical not only for functional effectiveness but also for emotional resonance and sustainable long-term use.

Looking forward, future research will focus on long-term deployments of the ranger robot in diverse home settings. These studies will be essential in understanding how engagement evolves over time and in determining whether initial novelty translates into lasting behavioral change. Moreover, future iterations may explore semi-autonomous learning capabilities, adaptive interaction styles, and personalized responses based on individual user profiles. Expanding the ranger’s capabilities while preserving its core simplicity will be a delicate but rewarding challenge.

In summary, the ranger robot represents an important step toward the development of socially integrated robotic systems that are both accessible and impactful. It underscores the potential of embedding intelligent behavior into mundane objects and demonstrates that effective human-robot cooperation can be achieved with careful design, even when using minimal computational resources. This work contributes to the growing field of domestic robotics and offers valuable insights for researchers, designers, and practitioners aiming to create meaningful robotic experiences in everyday environments.

References

- Gates, B. A Robot in Every Home. Scientific American 2007, 296, 58–65.

- Eurobarometer. Public Attitudes Towards Robots. Technical Report March, 2012.

- Pantofaru, C.; Takayama, L.; Foote, T.; Soto, B. Exploring the role of robots in home organization. Proceedings of the seventh annual ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-Robot Interaction - HRI ’12 2012, p. 327. [CrossRef]

- Bell, G.; Blythe, M.; Sengers, P. Making by Making Strange: Defamiliarization and the Design of Domestic Technologies. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2005, 12, 149–173. [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, V.; Fink, J. Will your household adopt your new robot? Interactions 2012, 19, 60. [CrossRef]

- Duque, I.; Dautenhahn, K.; Koay, K.L.; Willcock, I.; Christianson, B. Knowledge-driven user activity recognition for a Smart House. Development and validation of a generic and low-cost, resource-efficient system. In Proceedings of the ACHI 2013, The Sixth International Conference on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions, 2013, pp. 141–146.

- Cavallo, F.; Aquilano, M.; Bonaccorsi, M.; Limosani, R.; Manzi, A.; Carrozza, M.C.; Dario, P. On the design, development and experimentation of the ASTRO assistive robot integrated in smart environments. Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2013 IEEE International Conference on and … 2013, 2, 4310–4315. [CrossRef]

- Aquilano, M.; Carrozza, M.C.; Dario, P. Robot-Era project (FP7-ICT-2011.5.4): from the end-user’s perspective to robotics. Preliminary findings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAL - Ambient Assisted Living Forum 2012, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2012.

- Coradeschi, S.; Cesta, A.; Cortellessa, G.; Coraci, L.; Gonzalez, J.; Karlsson, L.; Furfari, F.; Loutfi, A.; Orlandini, A.; Palumbo, F.; et al. Giraffplus: Combining social interaction and long term monitoring for promoting independent living. In Proceedings of the In Proceedings of Human System Interaction (HSI) 2013. Ieee, 2013, pp. 578–585. [CrossRef]

- Amirabdollahian, F.; op den Akker, R.; Bedaf, S.; Bormann, R.; Draper, H.; Evers, V.; Gelderblom, G.; Gutierrez Ruiz, C.; Hewson, D.; Hu, N.; et al. Accompany: Acceptable robotiCs COMPanions for AgeiNG Years - Multidimensional aspects of human-system interactions. In Proceedings of the Human System Interaction (HSI), 2013 The 6th International Conference on, June 2013, pp. 570–577. [CrossRef]

- Nani, M.; Caleb-solly, P.; Dogramadgi, S.; Fear, C.; Heuvel, H.V.D. MOBISERV : An Integrated Intelligent Home Environment for the Provision of Health , Nutrition and Mobility Services to the Elderly. In Proceedings of the 4th Companion Robotics Workshop in Brussels, 2010.

- Gross, H.M.; Schroeter, C.; Mueller, S.; Volkhardt, M.; Einhorn, E.; Bley, A.; Martin, C.; Langner, T.; Merten, M. Progress in developing a socially assistive mobile home robot companion for the elderly with mild cognitive impairment. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2011, pp. 2430–2437. [CrossRef]

- Fischinger, D.; Einramhof, P.; Wohlkinger, W.; Papoutsakis, K.; Mayer, P.; Panek, P.; Koertner, T.; Hofmann, S.; Argyros, A.; Vincze, M.; et al. Hobbit-The Mutual Care Robot. In Proceedings of the Workshop-Proc. of ASROB, 2013.

- Bacciu, D.; Barsocchi, P.; Chessa, S.; Gallicchio, C.; Micheli, A. An experimental characterization of reservoir computing in ambient assisted living applications. Neural Computing and Applications 2013, 24, 1451–1464. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, J.; Lima, P.; Saffiotti, A.; Gonzalez-Pacheco, V.; Salichs, M. MOnarCH: Multi-robot cognitive systems operating in hospitals. In Proceedings of the ICRA 2013 Workshop on Many Robot Systems, 2013.

- Lehmann, H.; Walters, M.; Dumitriu, A.; May, A.; Koay, K.; Saez-Pons, J.; Syrdal, D.; Wood, L.; Saunders, J.; Burke, N.; et al. Artists as HRI Pioneers: A Creative Approach to Developing Novel Interactions for Living with Robots. In Social Robotics; Herrmann, G.; Pearson, M.; Lenz, A.; Bremner, P.; Spiers, A.; Leonards, U., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2013; Vol. 8239, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 402–411. [CrossRef]

- Wurman, P.; D’Andrea, R.; Mountz, M. Coordinating hundreds of cooperative, autonomous vehicles in warehouses. AI Magazine 2008, 29, 9–20.

- Fitzgerald, C.; Ed, D. Developing Baxter. In Proceedings of the Technologies for Practical Robot Applications (TePRA), 2013 IEEE International Conference on, 2013, pp. 1–6.

- Takayama, L.; Ju, W.; Nass, C. Beyond dirty, dangerous and dull: what everyday people think robots should do. Proceedings of the 3rd ACM/IEEE international conference on Human robot interaction 2008, pp. 25–32.

- Magnenat, S.; Rétornaz, P.; Bonani, M.; Longchamp, V.; Mondada, F. ASEBA: A Modular Architecture for Event-Based Control of Complex Robots. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 2011, 16, 321–329. [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.; Lemaignan, S.; Dillenbourg, P.; Rétornaz, P.; Vaussard, F.; Berthoud, A.; Mondada, F.; Wille, F.; Franinovic, K. Which Robot Behavior Can Motivate Children to Tidy up Their Toys ? Design and Evaluation of “ Ranger ”. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE international conference on Human-robot interaction, 2014, pp. 439–446.

- Green, P.; Wei-Haas, L. The rapid development of user interfaces: Experience with the wizard of oz method. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. SAGE Publications, 1985, Vol. 29, pp. 470–474.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).