Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Size

2.4. Outcomes and Measures

2.4.1. Anthropometric Assessment

2.4.2. Dietary Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Participants

3.1.1. Maternal Characteristics

3.1.2. Child Characteristics

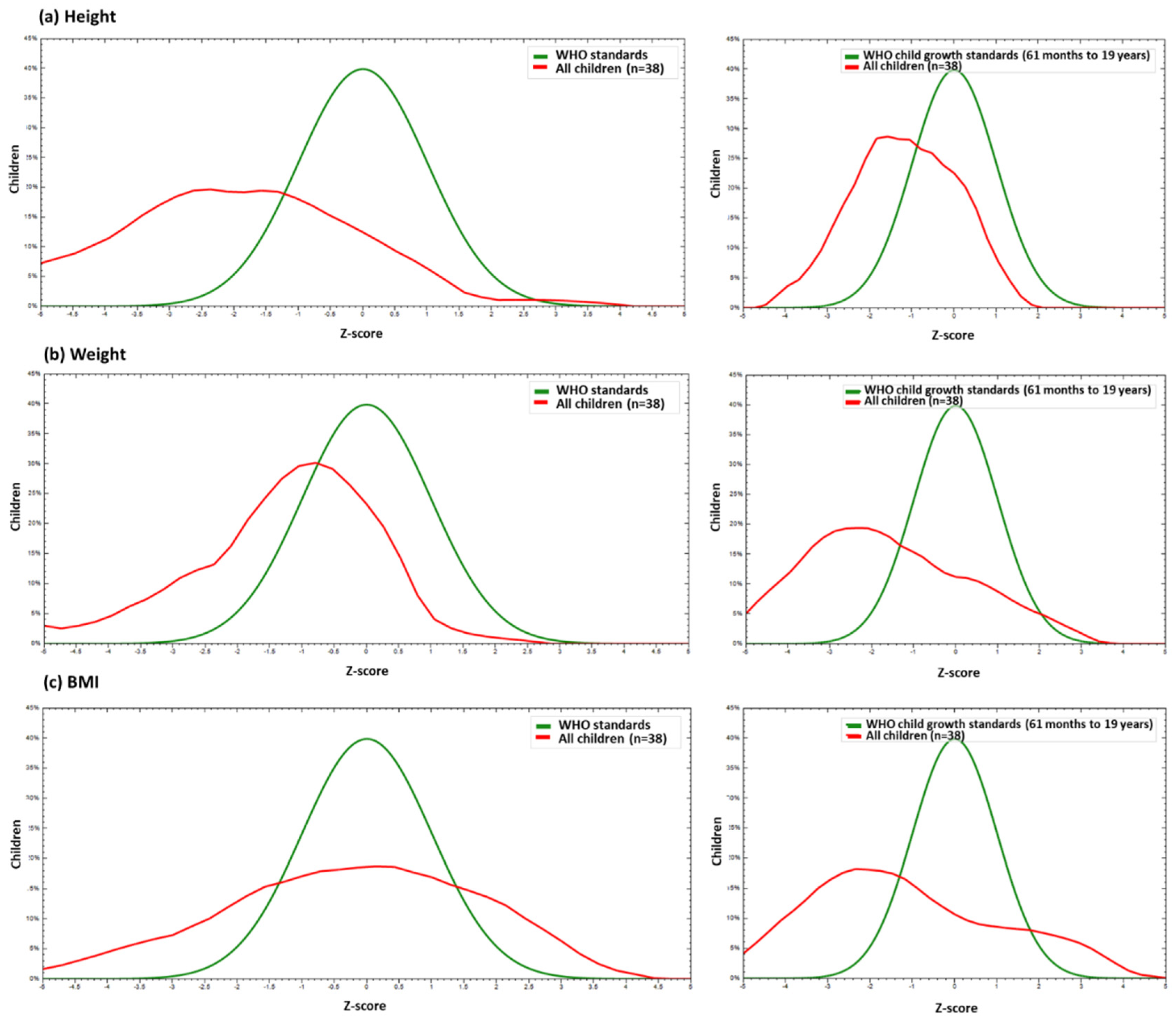

3.2. Anthropometric Outcomes

3.3. Dietary Intake and Association with BMI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CZVS | Congenital Zika Virus Syndrome |

| ZIKV | Zika Virus |

| HU-UFS | University Hospital of Sergipe |

| SUS | Sistema Único de Saúde |

| CHB | Child Health Booklet |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| AMDR | Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowance |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

References

- Costa, F.; Sarno, M.; Khouri, R.; de Paula Freitas, B.; Siqueira, I.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Ribeiro, H.C.; Campos, G.S.; Alcântara, L.C.; Reis, M.G.; et al. Emergence of Congenital Zika Syndrome: Viewpoint From the Front Lines. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 164, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.A.; Staples, J.E.; Dobyns, W.B.; Pessoa, A.; Ventura, C. V.; Fonseca, E.B. da; Ribeiro, E.M.; Ventura, L.O.; Neto, N.N.; Arena, J.F.; et al. Characterizing the Pattern of Anomalies in Congenital Zika Syndrome for Pediatric Clinicians. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, L. V; Paredes, C.E.; Silva, G.C.; Mello, J.G.; Alves, J.G. Neurodevelopment of 24 Children Born in Brazil with Congenital Zika Syndrome in 2015: A Case Series Study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.; Brites, C.; Mochida, G.; Ventura, P.; Fernandes, A.; Lage, M.L.; Taguchi, T.; Brandi, I.; Silva, A.; Franceschi, G.; et al. Clinical and Neurodevelopmental Features in Children with Cerebral Palsy and Probable Congenital Zika. Brain Dev. 2019, 41, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, R.A. de O.; Lovero, K.L.; Oliveira, S.A. de; Fernandes, A.R.; Santos, T.C.S. dos; Lima, L.C.S. de S.; Carvalho, F.R.; Quintans, M.D.S.; Bueno, A.C.; Torbey, A.F.M.; et al. Children Born to Mothers with Rash During Zika Virus Epidemic in Brazil: First 18 Months of Life. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2019, 65, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula, G.L.; da Silva, G.A.P.; e Silva, E.J. da C.; Lins, M. das G.M.; Martins, O.S. de S.; Oliveira, D.M. da S.; Ferreira, E. de S.; Antunes, M.M. de C. Vomiting and Gastric Motility in Early Brain Damaged Children With Congenital Zika Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.M.M.; de Melo, E.G.M.; Mendes, M.L.T.; dos Santos Oliveira, S.J.G.; Tavares, C.S.S.; Vaez, A.C.; de Vasconcelos, S.J.A.; Santos, H.P.; Santos, V.S.; Martins-Filho, P.R.S. Oral and Maxillofacial Conditions, Dietary Aspects, and Nutritional Status of Children with Congenital Zika Syndrome. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, S.F.M.; Soares, F.V.M.; de Abranches, A.D.; da Costa, A.C.C.; Moreira, M.E.L.; de Matos Fonseca, V. Infants with Microcephaly Due to ZIKA Virus Exposure: Nutritional Status and Food Practices. Nutr. J. 2019, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, T.; Medeiros, W.; Souza, N.; Longo, E.; Pereira, S.; França, T.; Sousa, K. Growth and Development of Children with Microcephaly Associated with Congenital Zika Virus Syndrome in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.S.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Palacios, C. Feeding Modifications and Additional Primary Caregiver Support for Infants Exposed to Zika Virus or Diagnosed with Congenital Zika Syndrome: A Rapid Review of the Evidence. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2020, 25, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.J.G. de; Tavares, C.S.S.; Santos, V.S.; Santos Jr, H.P.; Martins-Filho, P.R. Anxiety, Depression, and Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with Congenital Zika Syndrome: Results of a 5-Year Follow-up Study. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2022, 55, e06272021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Ações Programáticas e Estratégicas. Protocolo de Vigilância e Resposta à Ocorrência de Microcefalia Relacionada à Infecção Pelo Vírus Zika: Plano Nacional de Enfrentamento à Microcefalia; 2015.

- Stevenson, R.D. Use of Segmental Measures to Estimate Stature in Children With Cerebral Palsy. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1995, 149, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO World Health Organization. Screening, Assessment and Management of Neonates and Infants with Complications Associated with Zika Virus Exposure in Utero; 2016.

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Coordenação-Geral da Política de Alimentação e Nutrição. Incorporação da Curvas de Crescimento da Organização Mundial da Saúde de 2006 e 2007 no SISVAN; 2007.

- Freudenheim, J.L. A Review of Study Designs and Methods of Dietary Assessment in Nutritional Epidemiology of Chronic Disease. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culley, W.J.; Middleton, T.O. Caloric Requirements of Mentally Retarded Children with and without Motor Dysfunction. J. Pediatr. 1969, 75, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumbo, P.; Schlicker, S.; Yates, A.A.; Poos, M. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein and Amino Acids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC National Research Council. Recommended Dietary Allowances: 10th Edition; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 1989; ISBN 978-0-309-04633-6. [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C.G.; Adair, L.; Fall, C.; Hallal, P.C.; Martorell, R.; Richter, L.; Sachdev, H.S. Maternal and Child Undernutrition: Consequences for Adult Health and Human Capital. Lancet 2008, 371, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagini, F.; Mameli, C.; Fabiano, V.; Brunetti, D.; Dilillo, D.; Zuccotti, G. Dietary Intakes and Nutritional Issues in Neurologically Impaired Children. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9400–9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham-McGregor, S.; Cheung, Y.B.; Cueto, S.; Glewwe, P.; Richter, L.; Strupp, B. Developmental Potential in the First 5 Years for Children in Developing Countries. Lancet 2007, 369, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.C.; van der Linden, V.; Bezerra, T.P.; de Valois, L.; Borges, A.C.G.; Antunes, M.M.C.; Brandt, K.G.; Moura, C.X.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Ximenes, C.R. Characteristics of Dysphagia in Infants with Microcephaly Caused by Congenital Zika Virus Infection, Brazil, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefton-Greif, M.A.; Arvedson, J.C. Schoolchildren With Dysphagia Associated With Medically Complex Conditions. Lang. Speech. Hear. Serv. Sch. 2008, 39, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buraniqi, E.; Dabaja, H.; Wirrell, E.C. Impact of Antiseizure Medications on Appetite and Weight in Children. Pediatr. Drugs 2022, 24, 335–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho-Sauer, R.; Costa, M. da C.N.; Barreto, F.R.; Teixeira, M.G. Congenital Zika Syndrome: Prevalence of Low Birth Weight and Associated Factors. Bahia, 2015–2017. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 82, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, D.G. When Failure to Thrive Is About Our Failures: Reflecting on Food Insecurity in Pediatrics. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, e213–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | Critical values | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

|

Weight |

Percentile > 97/ Z-score > +2 | High weight for age. |

| Percentile > 3 and 97/ Z-score > -2 and +2 | Adequate weight for age. | |

| Percentile > 0.1 and < 3/ Z-score > -3 and < -2 | Low weight for age. | |

| Percentile < 0.1/ Z-score < -3 | Very low weight for age. | |

|

Height |

||

| Percentile > 3/ Z-score > +2 Z-score > -2 and +2 | Adequate height for age. | |

| Percentile > 0.1 and < 3/ Z-score > -3 and < -2 | Short stature for age. | |

| Percentile < 0.1/ Z-score < -3 | Very short stature for age. | |

|

BMI |

Percentile > 99.9/ Z-score > +3 | Obesity. |

| Percentile > 97 and 99.9/ Z-score +2 and +3 | Overweight. | |

| Percentile > 85 and 97/ Z-score > +1 and < +2 | Risk of overweight. | |

| Percentile > 3 and 85/ Z-score > -2 and +1 | Adequate BMI. | |

| Percentile > 0.1 and < 3/ Z-score > -3 and < -2 | Underweight. | |

| Percentile < 0.1/ Z-score < -3 | Severe underweight. |

| Variable | % (n) |

|---|---|

|

Age* Area of residence Rural Urban |

31.0 (25.0-37.0) 39.5% (15) 60.5% (23) |

|

Marital status Married/in a stable relationship Divorced/single |

78.9% (30) 21.1% (8) |

| Employed | |

| Yes | 21.1% (8) |

| No | 78.9% (30) |

|

Government benefit Yes No |

92.1% (35) 7.9% (3) |

| Monthly family income | |

| Less than 1 minimum wage | 5.3% (2) |

| From 1 to 3 minimum wages | 94.7% (36) |

| Number of births* | 2.0 (1.5-3.0) |

| Live births* | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) |

| Miscarriages* | 0.0 (0.0-0.0) |

|

Pregnancy wanted Yes No |

42.1% (16) 57.9% (22) |

|

Prenatal Yes Type of delivery Vaginal Cesarean |

100% (38) 55.3% (21) 44.7% (17) |

| Variable | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 52.6% (20) |

| Female | 47.4% (18) |

| Apgar 1º minute* | 9.0 (8.0-9.0) |

| Apgar 5º minute* | 10.0 (9.0-10.0) |

| Head circumference at birth* | 29.0 (27.5-30.0) |

| Severe microcephaly | |

| Yes | 81.6% (31) |

| No | 18.4% (7) |

| Current age | 6.3 (5.9-6.6) |

| Current head circumference* | 44.5 (42.0- 45.9) |

| Complications | |

| Arthrogryposis | 42.1% (16) |

| Seizure | 84.2% (32) |

| Dysphagia | 6.1% (23) |

| Ophthalmological disorders | 42.1% (16) |

| Hearing disorders | 23.7% (9) |

| Hypertonia | 39.5% (15) |

| Hyperreflexia | 7.9% (3) |

| Irritability | 31.6% (12) |

| Neurogenic bladder | 2.6% (1) |

| Need for hospitalization | |

| Yes | 63.2% (24) |

| No | 36.8% (14) |

| Currently attends school | |

| Yes | 21.1% (8) |

| No | 79.9% (30) |

| Measures | Birth | End of 1st childhood | Diagnostic Evolution | p-value(a) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) |

Adequate parameters for age (%) | Median (IQR) |

Adequate parameters for age (%) |

Remained adequate |

Improved | Remained Inadequate |

Worsened | ||

| Height (cm) | 45.0 (43.0 – 48.0) |

16 (42.1) |

108.8 (106.6 – 117.5) |

29 (76.3) |

12 (31.6) |

17 (44.8) |

5 (13.1) |

4 (10.5) |

0.007* |

|

Weight (Kg) |

2.7 (2.5 – 3.0) |

28 (73.7) |

15.8 (14.3 – 18.7) |

22 (57.9) |

16 (42.1) |

6 (15.8) |

4 (10.5) |

12 (31.6) |

0.238 |

| BMI | 13.0 (11.5 – 14.6) |

28 (73.7) |

13.2 (11.8 – 15.0) |

16 (42.1) |

11 (29.0) |

5 (13.1) |

5 (13.1) |

17 (44.8) |

0.017* |

| Variables | % (n) | Adequate BMI (n = 16) |

Inadequate BMI (n = 22) |

p-value(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily number of meals* | 5.0 (4.5-6.0) | 5.0 (4.6-5.9) | 5.3 (4.4-6.0) | 0.848 |

| Food intake | ||||

| Oral | 80.0% (30) | 68.8% (11) | 86.4% (19) | 0.243 |

| Enteral | 20.0% (8) | 31.2% (5) | 13.6% (3) | |

| Consistency of food | ||||

| Solid | 21.1% (8) | 18.8% (3) | 22.7% (5) | 0.450 |

| Liquid | 21.1% (8) | 31.2% (5) | 13.6% (3) | |

| Mushy | 57.8% (22) | 50.0 (8) | 63.7% (14) | |

| % of meals with cereals* | 22.5% (2.3-37.2) | 15.5% (0.0-30.1) | 26.2% (11.1-37.2) | 0.359 |

| % of meals with fruits* | 25.0% (17.1-36.4) | 25.0% (17.2-37.3) | 26.8% (17.1-35.6) | 0.906 |

| Ultra-processed food consumption | ||||

| Yes | 58.0% (22) | 56.3% (9) | 59.1% (13) | 1.000 |

| No | 42.0% (16) | 43.7% (7) | 40.9% (9) | |

| Minimum dietary diversity | ||||

| Yes | 34.2% (13) | 25.0% (4) | 40.9% (9) | 0.490 |

| No | 65.8% (25) | 75.0% (12) | 59.1% (13) |

| Variables | % (N) | Adequate BMI (n = 16) |

Inadequate BMI (n = 22) |

p-value(a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcal | ||||

| Adequate | 15.8% (6) | 6.3% (1) | 22.7% (5) | 0.370 |

| Inadequate | 84.2% (32) | 93.7% (15) | 77.3% (17) | |

| Macronutrients | ||||

| Proteins | ||||

| Adequate | 47.4% (18) | 50.0% (8) | 45.5% (10) | 1.000 |

| Inadequate | 52.6% (20) | 50.0% (8) | 54.5% (12) | |

| Carbohydrates | ||||

| Adequate | 84.2% (32) | 100.0% (16) | 72.7% (16) | 0.030¥ |

| Inadequate | 15.8% (6) | 0.0% (0) | 27.3% (6) | |

| Lipids | ||||

| Adequate | 52.6% (20) | 50.0% (8) | 54.5% (12) | 1.000 |

| Inadequate | 47.4% (18) | 50.0% (8) | 45.5% (10) | |

| Micronutrients | ||||

| Zinc | ||||

| Adequate | 10.5% (4) | 6.3% (1) | 13.6% (3) | 0.625 |

| Inadequate | 89.5% (34) | 93.7% (15) | 86.4% (19) | |

| Calcium | ||||

| Adequate | 2.6% (1) | 6.3% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 0.421 |

| Inadequate | 97.4% (37) | 93.7% (15) | 100.0% (22) | |

| Iron | ||||

| Adequate | 10.5% (4) | 6.3% (1) | 13.6% (3) | 0.625 |

| Inadequate | 89.5% (34) | 93.7% (15) | 86.4% (19) | |

| Vitamin D | ||||

| Adequate | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 1.000 |

| Inadequate | 100.0% (38) | 100.0% (16) | 100.0% (22) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).