1. Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a life-threatening condition characterized by rapid deterioration of hepatic function, severe coagulopathy, and hepatic encephalopathy in patients without preexisting liver disease. The most common etiologies are viral hepatitis and drug-induced liver injury (DILI), mainly acetaminophen toxicity [

1].

The etiology of ALF is a key factor in determining the prognosis and treatment strategy and varies by region

. In North America, Japan, and Europe, the leading causes in adults include DILI, viral hepatitis, and cryptogenic liver failure of unknown origin (indeterminate ALF) [

1,

2,

3]. In contrast, in developing countries, acute viral hepatitis remains the primary cause [

4]. The prognosis of ALF is highly variable, with survival rates largely dependent on timely supportive care and, in many cases, liver transplantation. However, limited organ availability poses a significant challenge, highlighting the need for alternative therapeutic strategies to improve survival in nontransplant candidates [

5].

In Mexico, ALF remains a critical health concern. From 1998–2009, there were 2,193 reported ALF-related deaths, with the mortality rate increasing from 13.1 to 40.2 deaths per 10 million inhabitants during this period. This increasing trend underscores the growing impact of ALF on the Mexican population [

6].

Standard medical treatment (SMT) for ALF primarily focuses on supportive measures, including infection control, the management of cerebral edema, and hemodynamic stabilization. However, given the systemic inflammatory response and multiorgan dysfunction frequently observed in ALF, additional interventions targeting the underlying pathophysiology are needed [

7,

8] Therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) has emerged as a promising extracorporeal therapy, facilitating the removal of inflammatory mediators, toxic metabolites, and coagulation disturbances associated with ALF[

9,

10].

A pivotal randomized controlled trial by Larsen

et al. [

11] demonstrated significantly improved transplant-free survival with high-volume TPE (HV-TPE) (58.7% vs. 47.8%) compared with SMT in patients with ALF. Nevertheless, higher volumes of plasma exchange may increase the risk of transfusion-associated complications, including volume overload, which can exacerbate cerebral edema. In this context, a randomized open-label controlled study conducted by Maiwall et al. [

12] revealed that standard-volume TPE (SV-TPE) is safe and effective and improves survival, possibly by mitigating cytokine storm and reducing ammonia levels.

Despite accumulating evidence supporting the use of TPE in ALF patients, data specific to Latin America remain scarce[

13]. This study aims to present real-world data comparing the 30-day survival rates of ALF patients treated with SMT alone with those of patients receiving SMT in combination with TPE, both HV-TPE and SV-TPE, in the tertiary care of the intensive care unit (ICU) in Mexico.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This real-world study included a total of 25 patients who were diagnosed with ALF and admitted to the ICU of Hospital Juárez in Mexico City, Mexico, between 2018 and 2024. Among the 25 patients, 12 patients received SMT (SMT group), between 2018 and 2021, and 13 patients received SMT combined with TPE (TPE group) between 2021 and 2024. Among the 13 patients in the TPE group, 8 received HV-TPE, whereas the remaining 5 patients received SV-TPE.

Eligibility

Eligible patients were male or female, aged 18 years or older, and had a confirmed diagnosis of ALF irrespective of the underlying etiology. The clinical diagnosis was based on the following criteria: international normalized ratio (INR) ≥1.5 or a prothrombin time (PT) increase of > 4–6 seconds above the reference value and elevated transaminases (ASAT and ALAT) 2–3 times the normal value. The laboratory tests included the following: coagulation studies: PT, INR, activated prothrombin time; complete chemistry panel: Na, K, Cl, Ca, Mg, P, HCO3, glucose, total and direct bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase, ASAT, ALAT, albumin, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, arterial blood gas, complete blood count, blood group test, serum acetaminophen levels and toxicology screening; and hepatotropic virus serology: Immunoglobulin M antibody (IgM) to Hepatitis A Virus, Hepatitis B surface antigen, IgM antibody to Hepatitis B core antigen, Antibody to Hepatitis E Virus, Antibody to Hepatitis C Virus, Hepatitis C Virus Ribonucleic Acid, IgM antibody to Herpes Simplex Virus type 1, Varicella Zoster Virus, and ceruloplasmin levels (for Wilson’s disease); pregnancy test; ammonia levels; autoimmune markers: Antinuclear Antibodies, Anti-Smooth Muscle Antibodies and serum immunoglobulin levels; and Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 and 1, amylase, and lipase. Imaging studies include ultrasound and angiography to rule out tumors or Budd‒Chiari syndrome, although these results are not always definitive. Evaluation for prior liver disease, such as cirrhosis, was also considered, as cirrhosis is a diagnostic criterion for ALF. Patients who were pregnant, were in the immediate or late postpartum period, or were diagnosed with acute‒chronic liver failure were excluded from the study.

Intervention

The SMT included antibiotics (piperacillin and tazobactam), N-acetylcysteine, and anti-cerebral edema treatment. Carbapenem and antifungal agents (fluconazole) were initiated for patients whose clinical status worsened, with or without elevated procalcitonin.

Vascular access for TPE was achieved via an 11-French, double-lumen hemodialysis catheter in the internal jugular vein. TPE was performed with the Spectra Optia® Apheresis System (Terumo Blood and Cell Technologies), which employs continuous-flow centrifugation for efficient plasma separation. The total blood volume (TBV) was calculated as 70 mL/kg of the patient’s weight, and the total plasma volume (TPV) was determined via the following formula: TPV = TBV × (1 – hematocrit). Standard volume-TPE was performed by exchanging 1.0-fold of patients’ TPV, whereas HV-TPE targeted 8- to 12-L exchange of patients’ TPV per session. The anticoagulant used was acid citrate dextrose at a ratio of 1:14. Plasma exchange was performed via the use of 20% human albumin and fresh frozen plasma in a 1:3 ratio as replacement fluids. The duration of each TPE session was approximately 3–4 hours for SV-TPE and 5–6 hours for HV-TPE. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical and Biochemical Evaluations

Baseline data, including liver enzyme levels (ASAT, ALAT), serum creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase, and serum ammonia levels, the use of vasopressors, bilirubin levels, and serum sodium levels, were collected. The severity of organ dysfunction was assessed via the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [

14], whereas the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was used to assess liver disease severity and the need for liver transplantation [

15]. Additionally, the King's College criteria were applied to assess the need for liver transplantation in patients with ALF not associated with acetaminophen toxicity [

16], and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score was used to assess disease severity and predict mortality in critically ill patients [

17]

.

Statistical Analysis

For all the statistical analyses, we combined patients treated with HV-TPE and those treated with SV-TPE due to the lack of statistical power to analyze them separately.

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the SMT and TPE groups were compared via appropriate statistical tests: ANOVA for continuous variables, the Kruskal‒Wallis test for variables that were not normally distributed, and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables.

Survival data were analyzed via Kaplan‒Meier estimates to assess survival probabilities for each treatment group (SMT vs. TPE). Kaplan‒Meier curves were generated via the survfit function from the

survival package in R [

18], with ICU days as the survival time and 30-day mortality as the primary outcome. Differences in survival between groups were compared via the log-rank test, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Binomial regression analysis was run to estimate the mortality probability stratified by the degree of hepatic encephalopathy. All the statistical analyses were performed via R software [

19].

3. Results

At 30 days, survival was 92% (12/13) in the TPE group and 50% (6/12) in the SMT group.

The only non-survivors in the TPE group had grade 4 encephalopathy, a SOFA score of 18, an APACHE II score of 26, and a MELD score of 34, and the etiology of ALF was hepatitis A. This patient, treated with HV-TPE, survived only one day in the ICU. The baseline parameters were comparable between the groups, except for the encephalopathy grade, which was significantly greater in the TPE group (

Table 1). Considering all 25 patients, the most prevalent etiology of ALF was hepatitis A (52%, n=13), followed by noncetaminophen drug hepatotoxicity (idiosyncratic DILI). No cases of cetaminophen drug hepatotoxicity were reported. Considering etiology by group, hepatitis A was also the most common hepatitis but was significantly more common in the TPE group (69%) than in the SMT group (33%,

Table 1).

All values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentage (%), as appropriate. Fisher’s exact test was used for gender. For continuous variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied when normality assumptions were not satisfied, while ANOVA was used for normally distributed variables, indicated with an asterisk (*). For etiology, the chi-square test was used for categorical variables when all expected values were ≥5; otherwise, Fisher’s exact test was applied. The p-value represents the statistical significance of differences between groups.

Abbreviations: DILI, Drug-Induced Liver Injury; ALL, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; AFLP, Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy.

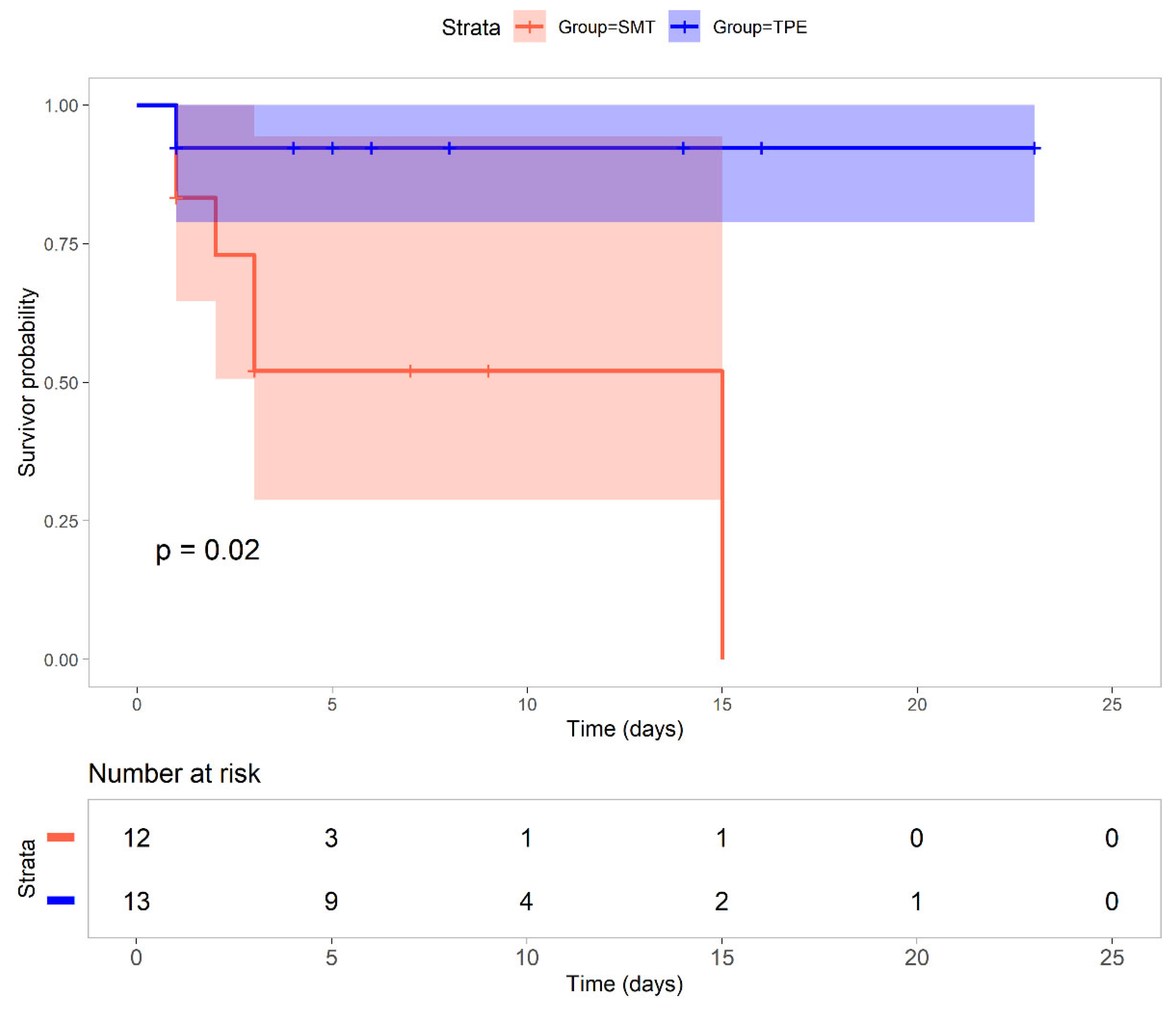

Survival analysis revealed a significant survival benefit with TPE (P=0.02,

Figure 1), particularly beyond the initial critical days. While both groups started with similar patient numbers (TPE group =13, SMT group =12), the survival probability in the SMT group declined from 0.83 on day 1 to 0.52 by day 3, reaching 0 by day 15. In contrast, the TPE group maintained a high survival probability of 0.92 from days 1 to 30 (95% CI: 0.70–1.00).

The log-rank test was used to assess differences between groups. The median survival and 30-day mortality rates are indicated. Statistical significance is reported as p values.

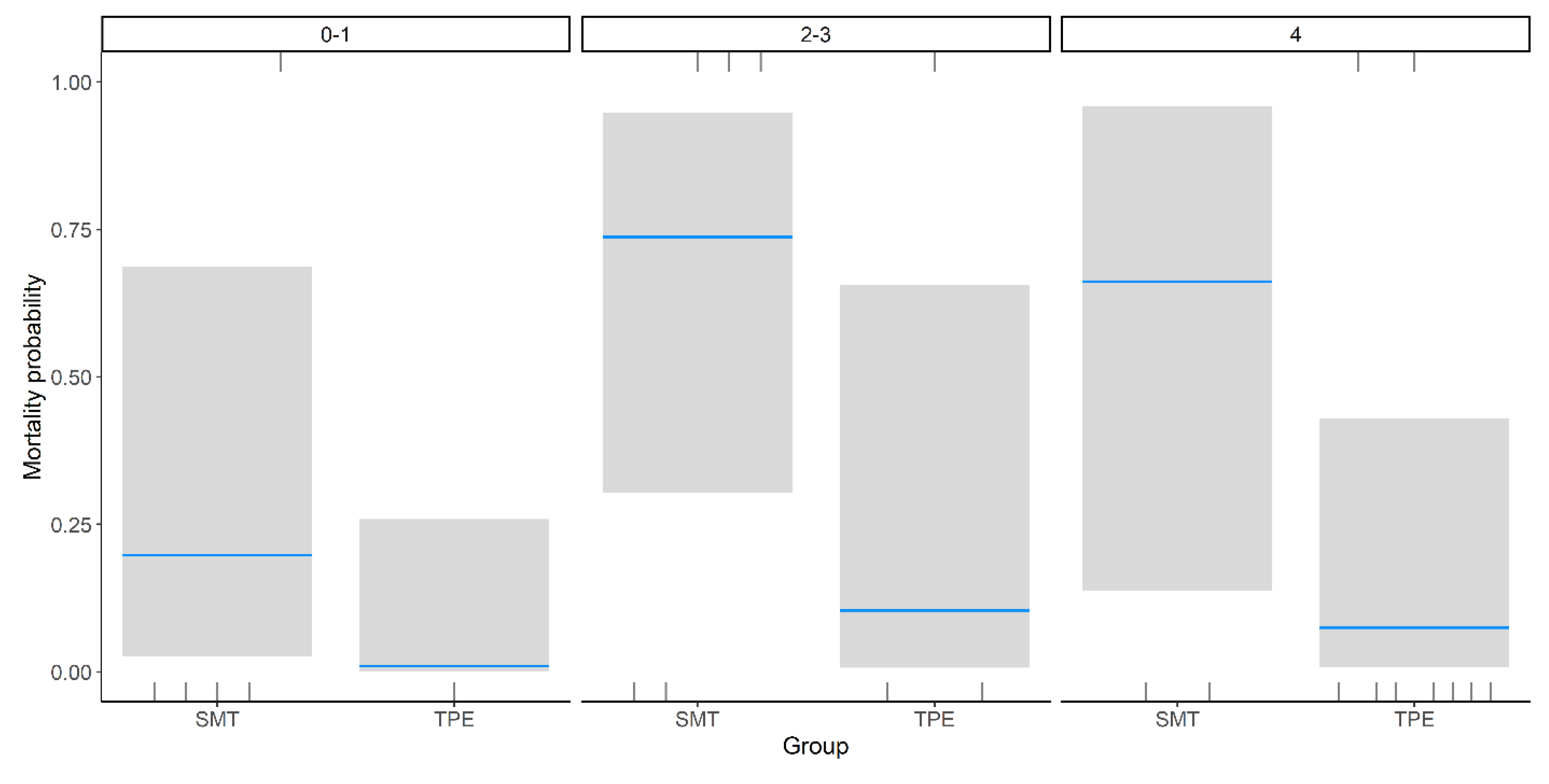

Binomial regression analysis demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in mortality among patients treated with TPE compared to standard medical treatment (β = –3.18, SE = 1.43,

p = 0.03), independent of encephalopathy grade. The greatest reduction in mortality was observed in patients with Grade 4 encephalopathy, although this did not reach statistical significance (β = 2.07, SE = 1.69,

p = 0.22) (

Table 2,

Figure 2).

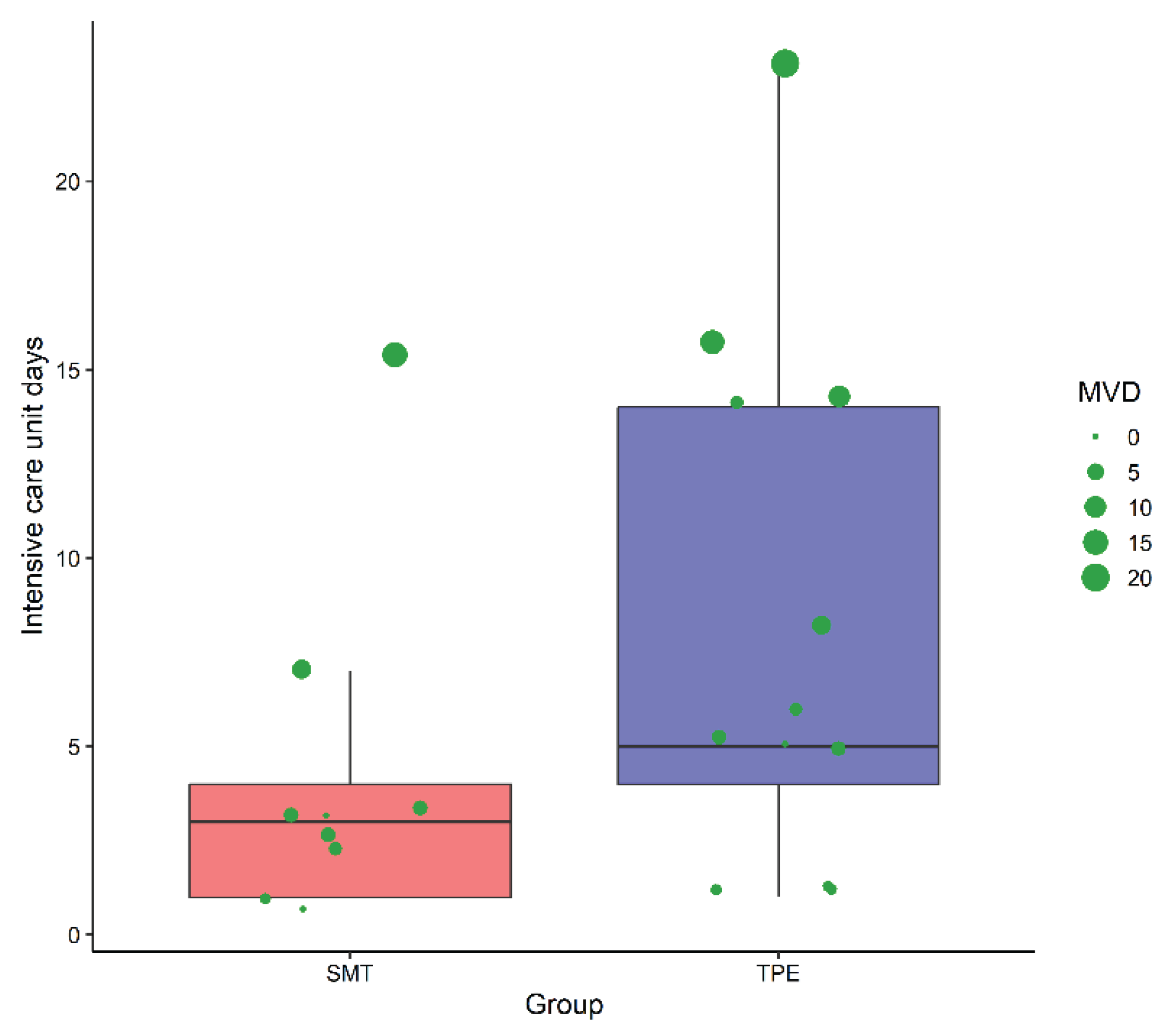

The duration of ICU stays varied between the groups. The SMT group typically stayed under five days, whereas the TPE group showed a broader distribution, extending beyond 20 days (

Figure 3). Mechanical ventilation was prolonged in both groups, with notable outliers in the TPE group, highlighting the complexity of ALF management with TPE.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study revealed a significant survival benefit associated with TPE in ALF patients compared with SMT alone. The Kaplan‒Meier survival analysis revealed a statistically significant improvement in 30-day survival rates for patients receiving TPE (p = 0.02). This aligns with the literature supporting TPE, both HV-TPE and SV-TPE, as promising adjunct therapies in ALF management, likely due to their role in mitigating systemic inflammation, improving hemodynamic stability, and reducing hepatic encephalopathy severity through the removal of inflammatory mediators and toxic metabolites [

11,

12,

20].

However, our findings contrast with those of Burke

et al. [

21], who reported no survival benefit of plasma exchange in a multicenter real-world cohort. Although their study included a larger sample size across multiple UK liver transplant centers, it lacked a clearly defined mortality endpoint beyond hospital discharge, making direct comparisons challenging.

Another key difference between the studies is the etiology of ALF. Burke

et al. [

21] reported that acetaminophen toxicity was the most prevalent cause in the TPE group, whereas in our cohort, hepatitis A was the most common etiology. While acetaminophen toxicity is a leading cause of ALF in North America and Europe, it is less common in developing regions. Given that etiology plays a crucial role in prognosis, further research is needed to better understand TPE outcomes in specific ALF subtypes [

1,

10].

In the absence of liver transplantation, the prognosis remains poor, particularly in patients with advanced hepatic encephalopathy. Our real-world study suggests that TPE offers a clinically meaningful survival advantage by enhancing hepatic detoxification and modulating immune dysregulation, potentially bridging patients to either spontaneous recovery or transplantation [

8,

9]

Despite the observed survival benefit, TPE-treated patients had longer ICU stays and greater variability in mechanical ventilation duration. This likely reflects the prolonged supportive care required for ALF recovery and the challenges of managing critically ill patients undergoing extracorporeal therapies. Notably, in our cohort, TPE-treated patients presented with higher encephalopathy grades than did the patients in the SMT group, approximately two grades higher, and had different etiologies (

Table 1). Additionally, the longer ICU stay in the TPE group may be partially influenced by survivor bias, as these patients lived longer and, consequently, had extended hospitalization periods [

22]

The strengths of our study include the use of a well-defined ALF cohort, rigorous inclusion criteria, and the application of standardized treatment protocols for both SMTs and TPE patients. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective nature of our analysis introduces potential selection biases and confounding variables that may have influenced survival outcomes. The sequential allocation treatment group, based on availability and evolving clinical practices, may have introduced temporal biases and differences in supportive care practices over time. Second, the small sample size limits the generalizability of our findings and precludes detailed subgroup analyses to delineate the differential effects of HV-TPE versus SV-TPE or etiology influence. Finally, while our study demonstrated a survival advantage, it did not clarify the optimal TPE regimen, frequency, or duration required for maximal therapeutic benefit.

Future research should focus on multicenter, prospective randomized trials with larger patient cohorts to confirm our findings and refine patient selection criteria. As ALF remains a challenging condition with high mortality, integrating TPE into a multimodal treatment approach represents a promising avenue to improve patient outcomes and potentially expand the therapeutic window for liver transplantation [

23,

24]

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study supports the use of TPE as a beneficial intervention in ALF patients, demonstrating a significant survival advantage over the SMT. While these findings reinforce the role of TPE in ALF management, further prospective studies are warranted to establish definitive guidelines and optimize therapeutic strategies for this critically ill patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama and Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez; Data curation, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama and Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez; Formal analysis, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez and Paula Costa-Urrutia; Investigation, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez, Mario Carrasco Flores, Enzo Vásquez-Jiménez, Paulina Carpinteyro-Espin, Juanita Pérez-Escobar, Karlos Gutierrez-Toledo, Pabli Galindo and Marcos Vidals-Sanchez; Methodology, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez, Mario Carrasco Flores and Pabli Galindo; Project administration, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama and Juanita Pérez-Escobar; Resources, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama and Enzo Vásquez-Jiménez; Software, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez and Pabli Galindo; Supervision, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez, Enzo Vásquez-Jiménez and Karlos Gutierrez-Toledo; Validation, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez, Juanita Pérez-Escobar and Karlos Gutierrez-Toledo; Visualization, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez, Paulina Carpinteyro-Espin and Marcos Vidals-Sanchez; Writing – original draft, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama and Paula Costa-Urrutia; Writing – review & editing, Jose Carlos Gasca-Aldama, Jesús Castrejón-Sánchez, Mario Carrasco Flores, Enzo Vásquez-Jiménez, Paulina Carpinteyro-Espin and Paula Costa-Urrutia.

Funding

This study was funded by Hospital Juarez, Mexico. Funding Number: HJM 071/24-R

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Hospital Juarez, Mexico, protocol number HJM 071/24-R

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data set used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mickael Beraud and Ivan Fan-Jun for their valuable contributions, which significantly improved the manuscript. Dr. Vásquez Jiménez is currently supported by Sistema Nacional de Investigadoras e Investigadores from Secretaría de Ciencias Humanidades, Tecnologías e Inhovación, Mexico (National System of Researchers from the Secretariat of Humanities, Sciences, Technologies, and Innovation)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Paula Costa-Urrutia is employed full-time in the Medical Affairs Department at Terumo BCT.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ALF Acute Liver Failure

TPE Therapeutic Plasma Exchange

SMT Standard Medical Treatment

ICU Intensive Care Unit

HV-TPE High-Volume Therapeutic Plasma Exchange

SV-TPE Standard-Volume Therapeutic Plasma Exchange

DILI Drug-Induced Liver Injury

ALL Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

AFLP Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

INR International Normalized Ratio

PT Prothrombin Time

ASAT Aspartate Aminotransferase

ALAT Alanine Aminotransferase

SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

MELD Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

APACHE II Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

IgM Immunoglobulin M

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

TBV Total Blood Volume

TPV Total Plasma Volume

DHL Lactate Dehydrogenase

TGO Transaminase Glutamic Oxaloacetic (AST/ASAT)

TGP Transaminase Glutamic Pyruvic (ALT/ALAT)

MVDs Mechanical Ventilation Days

R Statistical Programming Language used for analysis

References

- Shingina A, Mukhtar N, Wakim-Fleming J, Alqahtani S, Wong RJ, Limketkai BN, et al. Acute Liver Failure Guidelines. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2023;118:1128–53. [CrossRef]

- Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, et al. Causes, Clinical Features, and Outcomes From a Prospective Study of Drug-Induced Liver Injury in the United States. Gastroenterology 2008;135. [CrossRef]

- Schiodt F, V. , Atillasoy E, Shakil AO, Schiff ER, Caldwell C, Kowdley K V., et al. Etiology and outcome for 295 patients with acute liver failure in the United States. Liver Transplantation and Surgery 1999;5:29–34. [CrossRef]

- Manka P, Verheyen J, Gerken G, Canbay A. Liver failure due to acute viral hepatitis (A-E). Visc Med 2016;32:80–5. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk NB, Herdan E, Saner FH, Gurakar A. A Comprehensive Review of the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Liver Failure. J Clin Med 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Tapia NC, Barrientos-Gutiérrez T, Guerrero-López CM, Santiago-Hernández JJ, Méndez-Sánchez N, Uribe M. Acute liver failure in Mexico. vol. 11. 2012.

- Stravitz RT, Lee WM. Acute liver failure. vol. 394. 2019.

- Stravitz RT, Kramer DJ. Management of acute liver failure. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:542–53. [CrossRef]

- Bernal W, Lee WM, Wendon J, Stolze Larsen F, Williams R. Acute liver failure: A curable disease by 2024? Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license. vol. 62. 2015.

- Goel A, Zachariah U, Daniel D, Eapen CE. Growing Evidence for Survival Benefit with Plasma Exchange to Treat Liver Failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2023;13:1061–73. [CrossRef]

- Larsen F., S. LESCBAR et al,. High-volume plasma exchange in patients with acute liver failure: An open randomised controlled trial. J Hepatol 2016;64:10–2. [CrossRef]

- Maiwall R, Bajpai M, Singh A, Agarwal T, Kumar G, Bharadwaj A, et al. Standard-Volume Plasma Exchange Improves Outcomes in Patients With Acute Liver Failure: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2022;20:e831–54. [CrossRef]

- Vento S, Cainelli F. Acute liver failure in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;8:1035–45. [CrossRef]

- Vincent J-L, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendon~a A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis.related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. vol. 22. Springer-Verlag; 1996.

- Therneau TMLT. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2024;33:464–70. [CrossRef]

- George D, Craig N, Ford A, Hayes PC, Simpson J. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Prognostic tests of paracetamol-induced acute liver failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;10:1064-1076.

- Knaus WA, DEA, WDP, ZJE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29.

- Therneau TM, LT. Package “survival” 2024.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing 2021:1–2673.

- Kulkarni A, V. , Venishetty S, Vora M, Naik P, Chouhan D, Iyengar S, et al. Standard-Volume Is As Effective As High-Volume Plasma Exchange for Patients With Acute Liver Failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Burke L, Bernal W, Pirani T, Agarwal B, Jalan R, Ryan J, et al. Plasma exchange does not improve overall survival in patients with acute liver failure in a real-world cohort. J Hepatol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Karvellas CJ, Subramanian RM. Current Evidence for Extracorporeal Liver Support Systems in Acute Liver Failure and Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Crit Care Clin 2016;32:439–51. [CrossRef]

- Stravitz RT, Fontana RJ, Karvellas C, Durkalski V, McGuire B, Rule JA, et al. Future directions in acute liver failure. Hepatology 2023;78:1266–89. [CrossRef]

- Danielle Adebayo RPMRJ. Mechanistic biomarkers in acute liver injury: Are we there yet? J Hepatol 2012;56:1070–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).