1. Introduction

The cold recycling of asphalt pavement using emulsified asphalt offers several advantages, including high reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) utilization, construction at ambient temperature, extended construction seasons, and minimal environmental pollution. As a green technology characterized by low pollutions and low carbon emissions, this method aligns with China’s strategic goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality, and has been gaining increasing attention in the field of highway engineering. Its application in engineering practice is expanding. As the primary binder in cold recycling, emulsified asphalt is widely used in asphalt pavement maintenance and repair 1. Through the action of surfactants, emulsified asphalt forms a stable emulsion system in water, improving both its workability and environmental properties.

However, both practical experience and research have demonstrated that traditional cold-recycled pavements using emulsified asphalt exhibit several significant limitations, including poor mechanical performance, low toughness, rapid performance deterioration, and short service life 2. These pavements are prone to cracking and loosening, which undermine overall mechanical properties and road performance 3, ultimately reducing their service life. Therefore, the development of high-performance modified emulsified asphalt has become a critical focus in pavement engineering.

Extensive studies have been conducted to enhance the service performance, aging resistance, and storage stability of emulsified asphalt. Among various modifiers, waterborne polyurethane (WPU) has gained some attentions due to its favorable mechanical strength, weather resistance, and environmental friendliness. WPU has been shown to improve the rheological properties of asphalt, particularly its high-temperature deformation resistance 4-6. Zhang, et al. 7 reported that a 15% WPU content offers optimal performance and significantly improves storage stability. Li, et al. 8 concluded that WPU enhanced ductility but reduced adhesion of emulsified asphalt, and the modification process was predominantly physical. They recommended limiting WPU content to below 6%. Similarly, Zhao, et al. 9 observed a positive correlation between WPU dosage and performance when the dosage remains under 9 wt%. In contrast, Mu, et al. 10 argued that limited compatibility between WPU and asphalt could lead to inconsistent modification effects. Therefore, further research was required to better understand the compatibility, structural integrity, and microstructural evolution of WPU-modified emulsified asphalt 11.

WPU is classified into cationic, anionic, and nonionic types 12. The stability of emulsified asphalt is influenced differently by emulsifiers of various ionic types 13. Anionic polyurethane has been reported to enhance the rheological behavior of emulsified asphalt, shifting its characteristics from viscous to elastic performance 14. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis revealed that the modification of cationic emulsified asphalt by WPU primarily involved physical blending 15. Mu et al. 16 examined the performance of cationic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt across different temperatures and identify 110 °C as the optimal evaporation residue temperature, where FTIR absorption peak was the most intense and key performance indicators—penetration, softening point, and ductility—were significantly improved. Although various modification effects were observed among different WPU ionic types 17, the underlying mechanisms remain insufficiently studied 18-19, particularly concerning the compatibility behavior between emulsified asphalt and WPU with different ionic natures.

The incorporation of WPU into emulsified asphalt effectively improves its performance. However, poor compatibility between WPU and asphalt limited further enhancement of modification effect. To address this issue, researchers commonly regulated WPU structure by introducing ionic groups. Most existing studies focused on modification mechanisms of cationic WPU, while limited attention was given to anionic and non-ionic types. The specific roles and comparative effects of different WPU types on emulsified asphalt remained unclear, and a systematic understanding of their interaction mechanisms, interfacial behavior, and impact on asphalt microstructure is still lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to develop WPU-modified emulsified asphalt using different ionic types of WPU and to clarify their modification effects, revealing the mechanisms by which WPU influences the performance and structure of emulsified asphalt.

In this study, anionic, cationic, and non-ionic WPUs were incorporated into anionic and cationic emulsified asphalt systems to prepare modified samples. The performance of these samples was first evaluated using basic performance tests, including penetration, softening point, ductility, and storage stability. FTIR analysis was then conducted to investigate the effects of WPU type on chemical composition and key functional groups, providing insights into the physical and chemical interactions between WPU and asphalt. Finally, AFM tests were used to examine the microstructural characteristics of modified samples, revealing the compatibility mechanism and microstructural evolution of WPU-modified emulsified asphalt. A multidimensional framework integrating performance, structure, and mechanism was established, clarifying the regulatory role of WPU ionic structure in interfacial compatibility and modification effectiveness. This work provides theoretical support and technical guidance for the design and optimization of high-performance WPU-modified emulsified asphalt materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Base Asphalt

Emulsified asphalt was prepared using 70# base asphalt with a penetration grade of 60-80, and its basic properties were tested according to Chinese Standard Test Methods of Asphalt and Asphalt Mixtures for Highway Engineering (JTG E20-2011). The results, shown in

Table 1, indicated that all technical specifications met the requirements of Chinese Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Asphalt Pavements (JTG F40-2004). The test methods in

Table 1 were all tested according to (JTG E20-2011).

2.1.2. Anionic/Cationic Emulsifiers

Slow-cracking fast-setting cationic emulsifier and slow-cracking fast-setting anionic emulsifier produced by Rongcheng Road and Bridge Company, China, were selected, and the performance indicators were listed in

Table 2.

2.1.3. Experimental Water

The water used in this experiment was laboratory tap water without any impurity. The main water quality parameters were as follows. The pH value ranged from 7.5 to 8.5, electrical conductivity ranged from 5 to 8 μS/cm, hardness ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 mmol/L, and chloride ion concentration ranged from 10 to 30 mg/L. This water quality ensured that there was no additional interference in the emulsification process.

2.1.4. Hydrochloric Acid Modifier

Cationic emulsifiers were adjusted to a pH value of 2-3 using hydrochloric acid during use, while anionic emulsifiers were adjusted to a pH value of 12-13 using alkali. The basic indicators of hydrochloric acid are shown in

Table 3. The hydrochloric acid was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China.

2.1.5. Emulsified Asphalt

Two types of anionic and cationic emulsified asphalts were used, and their basic performance indicators were shown in

Table 4.

2.1.6. Different Ionic WPUs

The performance parameters of different ionic WPU were presented in

Table 5. The waterborne polyurethane was purchased from Shanghai Sisheng Polymer Materials Co., Ltd., China.

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.2.1. Preparation of Matrix Emulsified Asphalt

The emulsification equipment selected for this experiment was the JM-1 small emulsifier from Wuxi Petroleum Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd., China. The specific sample preparation steps were as follows. To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of experimental results, parallel experiments were conducted for sample preparation with no fewer than three samples in each group. The allowable error was controlled within 15%. If the error exceeded this threshold, the samples were re-prepared.

(1) Heating of asphalt

To ensure proper flowability, base asphalt, which was solid at room temperature, was preheated in an oven at 140 °C. This step allowed asphalt to flow smoothly through the colloid mill during its emulsification.

(2) Preparation of soap solution

The soap solution was prepared by dissolving the emulsifier in water at a predetermined ratio. The solution temperature of soap solution was controlled at approximately 60 °C.

(3) Preparation of emulsified asphalt

Prior to emulsification, hot water (60°C) was circulated through colloid mill to minimize heat loss during its emulsification. Once preheating was complete, soap solution was cycled into colloid mill. After no significant bubbles were generated, the heated asphalt was slowly added. The mixture was sheared for 1 min, and then the three-way valve was opened to release emulsified asphalt.

(4) Storage of emulsified asphalt

Immediately after preparation, emulsified asphalt was allowed to cool to room temperature while being gently stirred with a glass rod. After cooling, it was filtered using a 1.18 mm filter screen. Once filtration was completed, it was sealed for storage.

2.2.2. Preparation of WPU Modified Emulsified Asphalt

The preparation equipment for WPU-modified emulsified asphalt was selected as FM 300 intermittent high-speed shear disperser from Shanghai Fluke Company, China.

The preparation methods for modified emulsified asphalt were generally categorized into two approaches, including modification prior to emulsification and emulsification followed by modification. In this study, the former approach was initially attempted. The soap solution was first prepared and introduced into a colloid mill for emulsification, after which WPU was added, followed by heated base asphalt. However, emulsified asphalt exhibited poor flowability and solidified after being left for a period, resulting in a poor emulsification effect. Therefore, the method of emulsification followed by modification was employed. Base emulsified asphalt was first prepared. After that, WPU and emulsified asphalt were mixed together using a high-speed shear machine. During this process, a glass rod was used for slowly stirring until the sample cooled to room temperature, after which it was sealed and stored.

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Basic Performance Test

Basic properties of prepared WPU-modified emulsified asphalt were evaluated according to JTG E20-2011, including penetration, ductility and softening point.

2.3.2. Fourier Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Test

To analyze the effect of WPU on primary chemical components and functional groups of emulsified asphalt, samples were prepared by depositing a thin film onto specialized silicon wafers (10 mm × 10 mm) using a pipette, and the film thickness was controlled to less than 10 mm. After film formation, infrared spectroscopy tests were conducted. The testing equipment and samples are shown in

Figure 1. FTIR instrument used was Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50. The front surface was selected for testing, and the test mode was set to ATR with absorbance. The samples were scanned 32 times, and the background was scanned 32 times. The resolution was set to 4 cm⁻¹ with a gain of 1.000, a mirror speed of 0.4747, and an aperture of 100.00. The wavenumber range was from 4000 cm⁻¹ to 400 cm⁻¹.

2.3.3. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Test

To investigate the effect of WPU on micromorphology and microstructure of emulsified asphalt, samples were prepared by depositing the material onto specialized silicon wafers (10 mm × 10 mm) using a pipette, and each sample thickness was controlled to less than 10 mm. After samples were cured, AFM test was conducted. The test equipment and samples are shown in

Figure 2. AFM instrument used was Dimension FastScan from Bruker. The parameters for the microcantilever setup were as follows. The tip radius was 650 nm, the tip length was 115 µm, and the width was 25 µm. The scanning area was 10 µm × 10 µm. The resolution was 256 × 256. The tip frequency was 70 kHz. The elasticity coefficient of the tip was 0.4 N/m.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. WPU-Modified Emulsified Asphalt Basic Properties

To evaluate the effect of different types of WPU on basic properties of emulsified asphalt, a series of fundamental property tests are performed on the prepared samples. The corresponding results are presented in

Table 6. For clarity, the abbreviations were used based on the first letters of sample names (“Ce” for cationic emulsified asphalt, “CWpu+Ce” for cationic waterborne polyurethane + cationic emulsified asphalt, “Wpu+Ce “for nonionic waterborne polyurethane + cationic emulsified asphalt, ‘Ae’ for anionic emulsified asphalt ”AWpu+Ae” for anionic waterborne polyurethane + anionic emulsified asphalt and “Wpu+Ae” for nonionic waterborne polyurethane + cationic emulsified asphalt).

In

Table 6, the residual amount on the sieve for all systems remains very low (0.002%-0.015%), indicating that emulsified asphalt particles are fine and sieve loss is minimal, which contributes to improved construction uniformity. The viscosity ranges from 12 Pa.s to 17 Pa.s. After modification by WPU, the standard viscosity of emulsified asphalt increases to varying extents. This suggests that the incorporation of WPU enhances the viscosity of emulsified asphalt, thereby improving its adhesion and high-temperature stability.

As shown in

Table 6, the penetration values of four WPU-modified emulsified asphalt samples decrease when compared to that of base emulsified asphalt, indicating an improvement in high-temperature stability. This trend aligns with the observed increase in standard viscosity. The decreased penetration correlates with increased viscosity, consequently elevating softening point while reducing ductility at 15°C. Compared to base cationic/anionic emulsified asphalt, the four waterborne WPU-modified emulsified asphalt samples exhibit reduced storage stability, primarily influenced by pH and particle size of WPU. WPU is slightly alkaline, and when mixed with acidic emulsified asphalt, the heat is generated, which accelerates moisture evaporation and decreases stability 20. Larger particle sizes promote faster settling, further compromising stability. The use of anionic emulsifiers helps reduce particle size and improve stability. However, the dosage must be optimized, as both insufficient and excessive amounts of WPU negatively affect performance of modified emulsified asphalt.

Compared to the control sample (unmodified cationic emulsified asphalt), cationic waterborne polyurethane (WPU)-modified emulsified asphalt exhibits a 19.6% decrease in penetration, a 2.27% increase in softening point, and a 17.7% decrease in ductility. For the non-ionic WPU-modified system, the penetration decreases by 20.9%, the softening point increases by 1.7%, and the ductility decreases by 30.7%. Overall, WPU modification enhances the hardness and high-temperature stability of emulsified asphalt, but reduces its low-temperature toughness. Among the two, cationic WPU modification provides an improved rutting resistance while maintaining a certain level of low-temperature flexibility, making it suitable for regions with wide temperature fluctuations. In contrast, non-ionic WPU modification results in a harder emulsified asphalt with greater high-temperature stability but increases the susceptibility to low-temperature cracking. This is more appropriate for heavy-load environment at high temperature, but may increase cracking risk under cold conditions.

Compared to anionic emulsified asphalt, the penetration of anionic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt decreases by 11.4%, the softening point increases by 1.7%, and the ductility decreases by 50.5%. For non-ionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt, the penetration decreases by 19.9%, the softening point increases by 1.5%, and the ductility decreases by 68.2%. Overall, WPU modification improves the hardness and high-temperature stability of emulsified asphalt but significantly reduces its low-temperature flexibility, particularly in the non-ionic system, where the ductility loss is more severe than in the cationic system. The anionic WPU-modified asphalt demonstrates an increased hardness and softening point, yet the ductility decreases by 50.5%, indicating the reduced low-temperature crack resistance. The non-ionic WPU-modified asphalt shows even greater hardness (19.9% reduction in penetration) and a 68.2% reduction in ductility, resulting in increased brittleness at low temperatures and making it more suitable for high-temperature applications. Although anionic WPU system demonstrates slightly better low-temperature anti-crack performance, its crack resistance still requires further improvement.

In summary, WPU modification improves the hardness and high-temperature stability of emulsified asphalt but decreases its low-temperature ductility and storage stability. Following modification, the penetration values decrease, the softening point increases, and the ductility declines, indicating rutting resistance is improved but low-temperature ductility is diminished. Among the modified systems, cationic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt achieves a balance between high-temperature stability and moderate low-temperature flexibility, rendering it suitable for regions with large temperature fluctuations. The non-ionic WPU-modified system exhibits an increased hardness but suffers from pronounced low-temperature brittleness, rendering it more suitable for heavy-load applications in high-temperature environments. Storage stability generally decreases in all WPU-modified emulsified asphalts. Additionally, storage stability is generally reduced across all WPU-modified emulsified asphalts. Specifically, the cationic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt shows the lowest storage stability (0.7% sieve residue), while the anionic WPU-modified sample exhibits the highest stability (0.4% sieve residue). Overall, the anionic WPU system performs slightly better under low-temperature conditions but still requires further optimization to enhance crack resistance and storage stability.

3.2. Effect of WPU on Chemical Composition and Functional Groups of Emulsified Asphalt

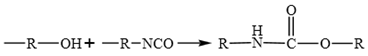

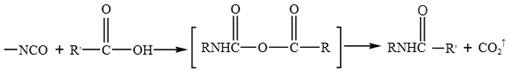

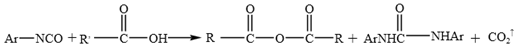

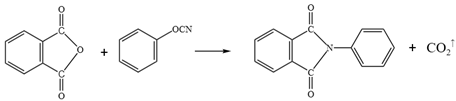

WPU resin consists of two main components of polyisocyanates and polyether/ polyester polyols 21. It readily reacts with phenols, anhydrides, carboxylic acids, and even water present in emulsified asphalt, leading to the formation of polyurethane carbamate acid (Equation 1). Isocyanates also react with phenols to generate carboxylic acids, which subsequently undergo further reaction to form anhydrides (Equation 2). These anhydrides react with water to produce amides and carbon dioxide. When aromatic carboxylic acids are present in asphalt or aromatic groups exist within the isocyanates, such stable products as anhydrides and ureas are formed (Equation 3). In addition, isocyanates react with anhydrides to yield acylamides (Equation 4).

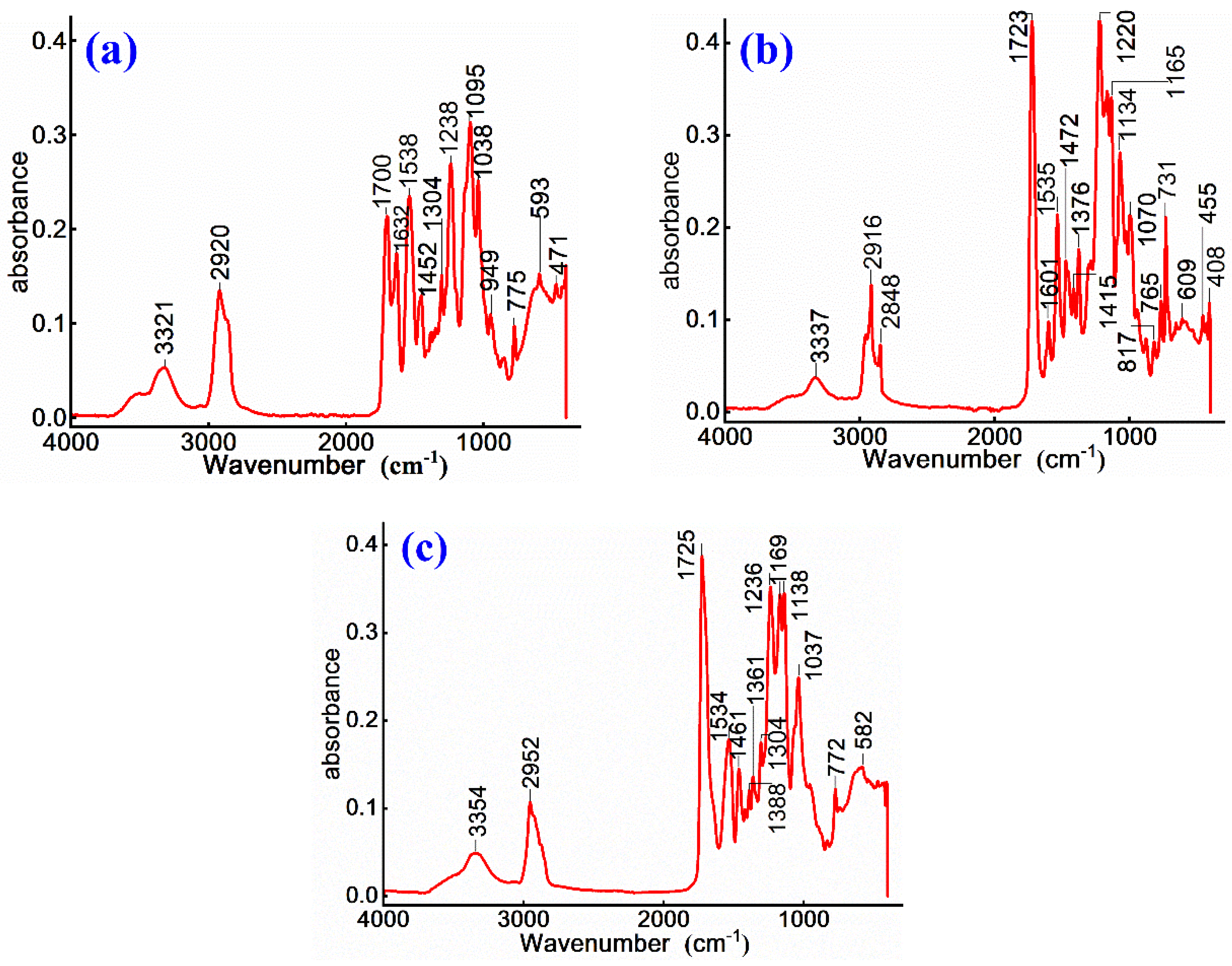

To investigate the curing behavior of WPU in emulsified asphalt and its interaction with asphalt matrix, FTIR is employed to analyze cationic and anionic emulsified asphalt, non-ionic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt, as well as cationic and anionic WPU-modified cationic and anionic emulsified asphalt. The functional groups and their variations in these blended systems are identified by examining characteristic peak positions and intensity changes intensity in the infrared spectra of each sample. Furthermore, FTIR is also used to characterize chemical structure and ionic properties of cationic, anionic, and non-ionic WPU as shown in

Figure 3.

As shown in

Figure 3, the infrared spectra of cationic, anionic, and non-ionic WPUs exhibit characteristic absorption peaks corresponding to carbamate (-NHCOO-) and ester (C=O) groups. The N-H and O-H stretching vibrations observed at 3321-3337 cm⁻¹ appear more intense in non-ionic WPU, whereas the peak of anionic WPU broadens due to the presence of carboxyl and sulfonic acid groups. These variations in hydrogen bond interactions may influence the stability of WPU within emulsified asphalt system. Enhanced hydrogen bonding in non-ionic WPU is presumed to improve emulsion cohesion, while polar functional groups in anionic WPU may impact dispersion and through electrostatic effects.

The C-H stretching vibrations at 2920-2952 cm⁻¹ correspond to the predominant soft segment structure in WPU. From

Figure 3 (a), non-ionic WPU exhibits a stronger peak because of the presence of polyether or polyester segments, while cationic and anionic WPUs display a marginally reduction in peak intensity, which is attributed to the influence of polar groups. These differences in soft segment composition influence the compatibility and stability between WPU and asphalt. Non-ionic WPU is considered to enhance wettability and dispersibility, while cationic and anionic WPUs may modify emulsification performance via polar group interactions.

In

Figure 3, the C=O stretching vibration at 1700-1725 cm⁻¹ represents the ester group structure, with a slight red shift observed in cationic WPU. This indicates that cationic WPU is more likely to interact with acidic emulsifiers in emulsified asphalt, affecting the stability of emulsion, while anionic WPU interacts with alkaline components in asphalt, influencing emulsification effect 22. The benzene ring skeletal vibrations at 1534-1601 cm⁻¹ are detected in all three samples but it may be more pronounced in anionic WPU. This enhancement may increase the rigidity of the emulsified asphalt membrane, improving firmness but potentially reducing flexibility.

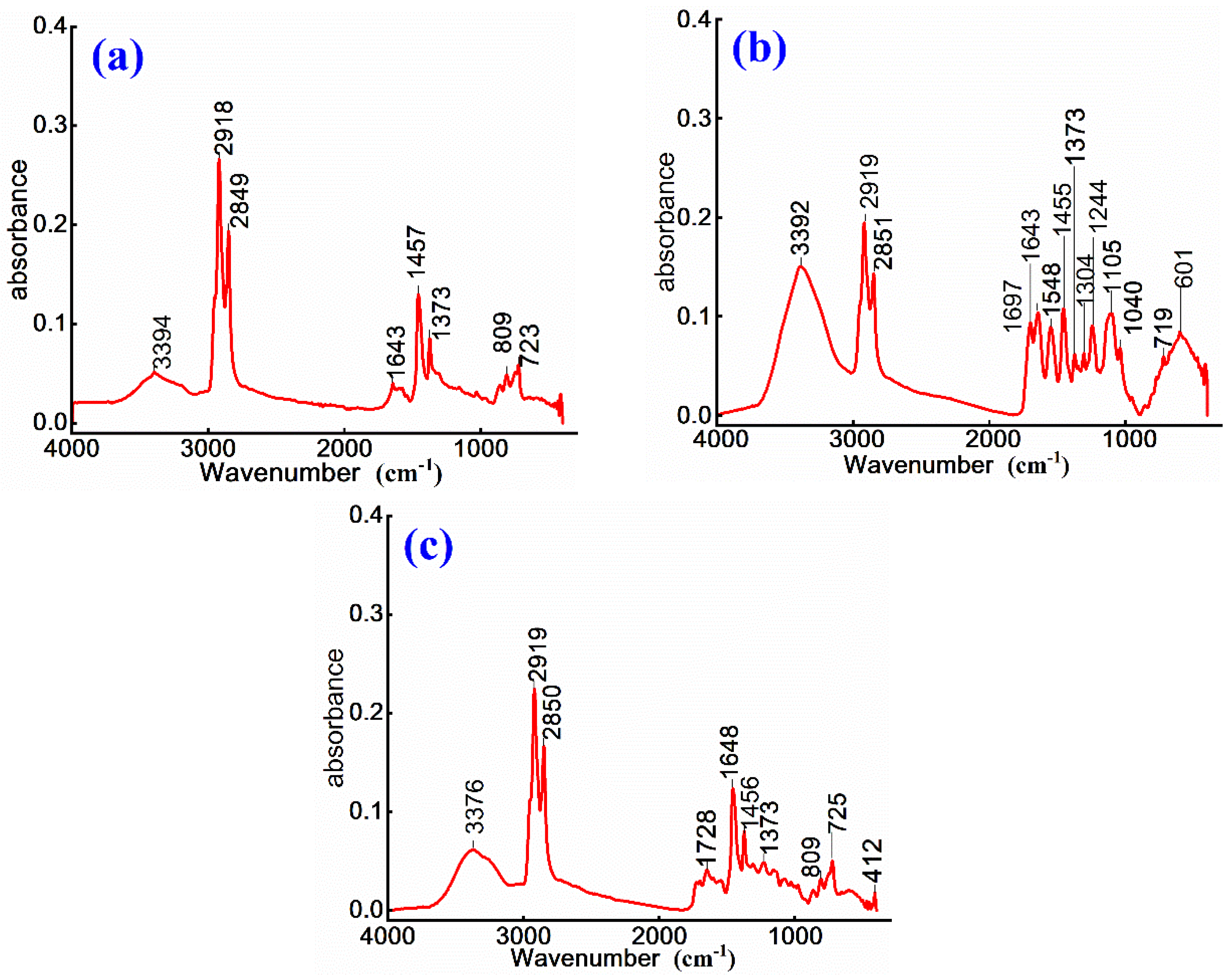

To investigate chemical structural evolution and modification effects of cationic emulsified asphalt, non-ionic WPU-modified cationic emulsified asphalt, and cationic WPU-modified cationic emulsified asphalt, FTIR characterization is conducted on prepared samples. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, the absorption peaks at 3394 cm⁻¹, 3392 cm⁻¹, and 3376 cm⁻¹ are attributed to N–H stretching vibrations of quaternary ammonium salts and O–H stretching vibrations of emulsified asphalt. This enhancement indicates that the introduction of WPU increases hydrogen bond interactions, thereby strengthening the association between emulsified particles and ions, improving the stability of emulsified system 23.The ester C=O absorption peaks at 1697 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 4 (b) and 1728 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 4 (c), along with the amide C=O characteristic peak at 1648 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 4 (c) indicate that WPU undergoes chemical reactions with asphalt, leading to the formation of new ester and amide bonds 24. These reactions improve the stability of polyurethane within asphalt matrix, with a more pronounced effect observed in the cationic WPU-modified system.

In

Figure 4 (b), the C-O stretching vibration at 1244 cm⁻¹, as well as ether C-O-C and alcohol C-O stretching vibrations at 1105 cm⁻¹ and 1040 cm⁻¹, respectively, suggest that the polyether or polyester segments of WPU soft phase influence the flexibility of emulsified asphalt. Among these, non-ionic WPU exhibits a more significant contribution, enhancing both the ductility and aging resistance of asphalt. The aromatic ring C-H out-of-plane bending vibrations at 900-700 cm⁻¹ and long-chain methylene in-plane rocking vibration at 723 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 4 (a) further confirm the dispersion of WPU within asphalt matrix. Additionally, the C-N and O-H out-of-plane bending vibration at 601 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 4 (b) indicates the presence of amide bonds and carboxyl groups, which influence the interfacial interactions of emulsified asphalt.

Overall, the formation of amide and carboxylic ester groups is more pronounced in cationic WPU-modified asphalt, reflecting stronger chemical interactions that enhance emulsion stability. In contrast, the incorporation of non-ionic WPU improves the flexibility and wettability of asphalt, primarily due to the contribution of its polyether structure. The characteristic peaks in unmodified cationic emulsified asphalt appear generally weaker, indicating that WPU modification significantly improves the chemical structure and overall performance of emulsified asphalt.

To investigate chemical structure evolution and modification effects of anionic emulsified asphalt, non-ionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt, and anionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt, FTIR is employed to characterize three prepared samples. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5 (a), the absorption peak at 3394 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups (O-H), indicating the presence of polar functional groups in both emulsified asphalt and WPU system. The absorption peaks at 2919 cm⁻¹ and 2850 cm⁻¹ correspond to antisymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of methylene groups, confirming the existence of alkane structures. A comparison of the spectra for WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt in

Figure 5 (b) and 5 (c) with that of anionic emulsified asphalt in

Figure 5 (a) shows a decrease in the intensity of absorption peaks at 2919 cm⁻¹, 2850 cm⁻¹, 1457 cm⁻¹, and 1373 cm⁻¹. This reduction suggests a relative decrease in alkyl group content after modification. This is due to the dilution of saturated aliphatic components in asphalt by the introduced WPU or partial chemical reactions 14.

Furthermore, absorption peak at 1642 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 5 (a) is attributed to the bending vibration of water molecules (H-O-H) and the stretching vibration of C=C bonds, indicating the coexistence of moisture and aromatic ring structures. In

Figure 5(c), a weak absorption peak appears at 1734 cm⁻¹, and at 1720 cm⁻¹ in

Figure 5(b), and both correspond to the stretching vibration of carbonyl (C=O) groups. These peaks suggest that the introduction of WPU increases the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups 25, such as ester or amide groups. This effect is more prominent in

Figure 5 (b) and 5 (c), further indicating that chemical interactions between WPU and asphalt, leading to the formation of ester or amide derivatives. These findings further confirm the structural stability of asphalt matrix.

In conclusion, the incorporation of WPU not only alters the alkyl content of emulsified asphalt, but also introduces new polar functional groups, thereby enhancing its polarity. The use of non-ionic WPU improves wettability and flexibility of asphalt, while anionic WPU affects emulsion dispersion and stability due to the charge effects associated with its polar groups.

3.3. Influence of WPU on Micromorphology and Microstructure of Emulsified Asphalt

To analyze surface morphology, microstructure, and surface roughness parameters of WPU-modified emulsified asphalt, AFM test is used to characterize anionic and cationic emulsified asphalt, non-ionic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt, and anionic/cationic WPU-modified anionic/cationic emulsified asphalt. The modification effects of different formulations are systematically investigated.

3.3.1. Influence of WPU on Surface Morphology of Emulsified Asphalt

The impact of cationic emulsifiers on microstructural characteristics of base asphalt is examined through AFM. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 6.

In AFM images, lighter regions indicate higher surface elevations, whereas darker regions correspond to lower elevations. This topographical pattern is also evident in the 3D morphology. As shown in

Figure 6 (a), the sample surface exhibits a honeycomb-like structure with a relatively uniform distribution of continuous phase and a vertical height variation of approximately 52.3 nm.

Figure 6 (b) further reveals that the surface of cationic emulsified asphalt shows noticeable roughness, characterized by an overall undulating morphology.

The phase image in

Figure 6 (c) shows a phase angle variation ranging from -3.9° and 4.6°, with a relatively uniform color distribution, suggesting the minimal phase separation and homogeneous surface properties.

Figure 6 (d) quantifies the surface height variation within the range of 0.5-1.5 μm, where a downward trend in the profile indicates the presence of local depressions or valleys. Beyond 1.5 μm, the surface height increases sharply, implying the existence of protrusions or peak-like structures, with a total height difference nearing 25 nm.

To assess the influence of non-ionic WPU on microscopic morphology of cationic emulsified asphalt, AFM characterizations are performed on non-ionic WPU-modified samples. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 7.

As shown in

Figure 7 (a), the highest point on sample surface reaches 57.0 nm, while the lowest point is -62.2 nm, resulting in a total height difference of 119.2 nm, which is increased by 66.9 nm when compared to that in

Figure 6 (a). The surface exhibits uneven color distribution, where the brighter regions are likely attributed to WPU phase, suggesting that the introduction of WPU induces microphase separation among cationic groups 26. This separation leads to the aggregation of WPU and the formation of larger phase domains, thereby increasing surface roughness.

Figure 7 (b) further reveals more distinct surface protrusions and depressions, along with reduced uniformity, supporting the occurrence of microphase separation.

In

Figure 7(c), the phase angle ranges from –7.3° to 8.7°, exceeding that observed in

Figure 6(c), and is accompanied by the enhanced color contrast. This indicates greater surface hardness and more pronounced phase separation. These observations indicate greater surface stiffness and more evident phase separation, likely due to limited interaction between WPU and cationic emulsified asphalt matrix, which reduces overall compatibility 27.

Figure 7 (d) shows a surface height difference exceeding 60 nm, further confirming that the incorporation of WPU increases surface undulations and roughness. These morphological changes influence key material properties, such as adhesion performance and mechanical stability.

To further examine the influence of cationic WPU on the microstructure of cationic emulsified asphalt, a systematic analysis is conducted on the evolution of ionic structure within asphalt microstructure. AFM characterization results for modified samples are presented in

Figure 8.

Figure 8 (a) shows that sample presents a bright and uniform overall color distribution, with a phase structure that is more homogeneous than those in

Figure 6 (a) and 7 (a). The maximum height difference is 34.1 nm, representing the smallest surface fluctuation among the three sample groups and indicating relatively low surface roughness.

Figure 8 (b) further reveals a more uniform surface morphology, confirming that the incorporation of cationic WPU improves the microstructure of emulsified asphalt.

The modification effect of cationic WPU primarily results from the introduction of cationic groups, which regulates the molecular structure of WPU. Hydrogen bond donors (-NH, -OH) and acceptors (C=O) in cationic WPU interact with polar groups (carboxyl and ester groups) in cationic emulsified asphalt through hydrogen bonding 28, which are consistent with FTIR analysis results. These interactions enhance intermolecular forces and improve interfacial compatibility between components. As a result, asphalt matrix exhibits an increased uniformity, a reduced microscopic phase separation, and a decreased surface roughness.

Figure 8 (c) and 8 (d) further validate these findings. The phase angle variation remains minimal, with a balanced color distribution and smooth transitions, indicating a highly uniform surface. The phase height difference is approximately 5 nm, providing additional evidence of enhanced surface uniformity and refined microstructure. These results clearly demonstrate that cationic WPU modification significantly enhances interfacial compatibility, uniformity, and surface characteristics of cationic emulsified asphalt, offering experimental support for further optimization of modification system.

To investigate the influence of microstructure on anionic emulsified asphalt, AFM characterization is conducted on modified samples prepared from anionic emulsified asphalt as presented in

Figure 9.

Figure 9 (a) illustrates that sample exhibits a relatively uniform honeycomb-like morphology, with a balanced color distribution and only a few slightly brighter regions. The surface height variation ranges from -5.2 nm to 5.0 nm, which is significantly lower than that observed in cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 9 (b) also reveals a smoother surface compared to

Figure 6(a). This difference is primarily attributed to the charge properties and particle sizes of anionic and cationic emulsifiers 29. In anionic emulsified asphalt, the negatively charged particles repel each other, promoting a more uniform dispersion and resulting in a smoother surface. Conversely, the positively charged particles in cationic emulsified asphalt interact electrostatically with negatively charged mineral aggregates, leading to particle aggregation and larger surface undulations. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 5, the particles in anionic emulsified asphalt are generally smaller and more uniformly dispersed within the matrix, thereby reducing the overall surface roughness.

Figure 9 (c) presents a phase angle variation from -8.2° to 5.4°, along with a relatively smooth color transition, indicating minor variations in physical properties across the surface. A low degree of phase separation is observed. The height variation in

Figure 9 (d) approaches 6 nm, reflecting reduced surface roughness, which is consistent with the previous analytical results.

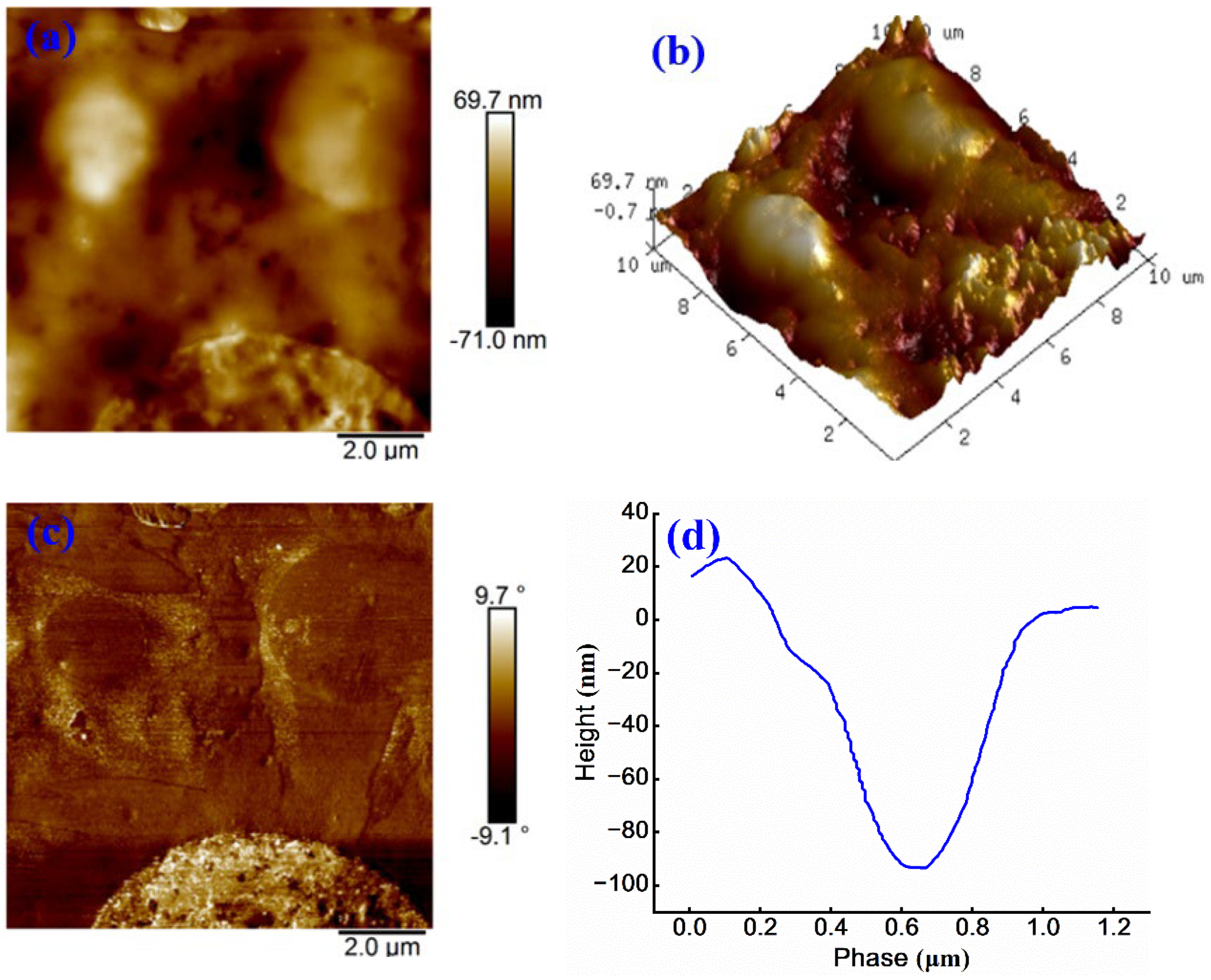

To investigate modification effect of non-ionic WPU on the microstructure of anionic emulsified asphalt, AFM characterization is conducted on the modified samples. The corresponding results are shown in

Figure 10.

Figure 10 (a) illustrates a reduction in honeycomb structure of sample, accompanied by an increase in both the number and area of bright regions. The maximum surface height point reaches 69.7 nm, while the minimum is −71.0 nm, resulting in a total height difference of 140.7 nm. Compared to

Figure 7 (a), the surface roughness increases by 21.5 nm, indicating that the roughness of WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt exceeds that of cationic emulsified asphalt. This is likely attributed to the lack of strong interactions between WPU and anionic groups, which causes WPU aggregation, hinders uniform dispersion, and consequently increases surface roughness 30.

Figure 10 (b) further supports this observation.

Figure 10(c) reveals a wider range of phase angle variations when compared to

Figure 9(c), suggesting an enhanced phase separation after the addition of WPU into anionic emulsified asphalt. The height difference in

Figure 10 (d) is approximately 110 nm, and the surface appears uneven, further confirming poor compatibility of WPU within anionic emulsified asphalt system.

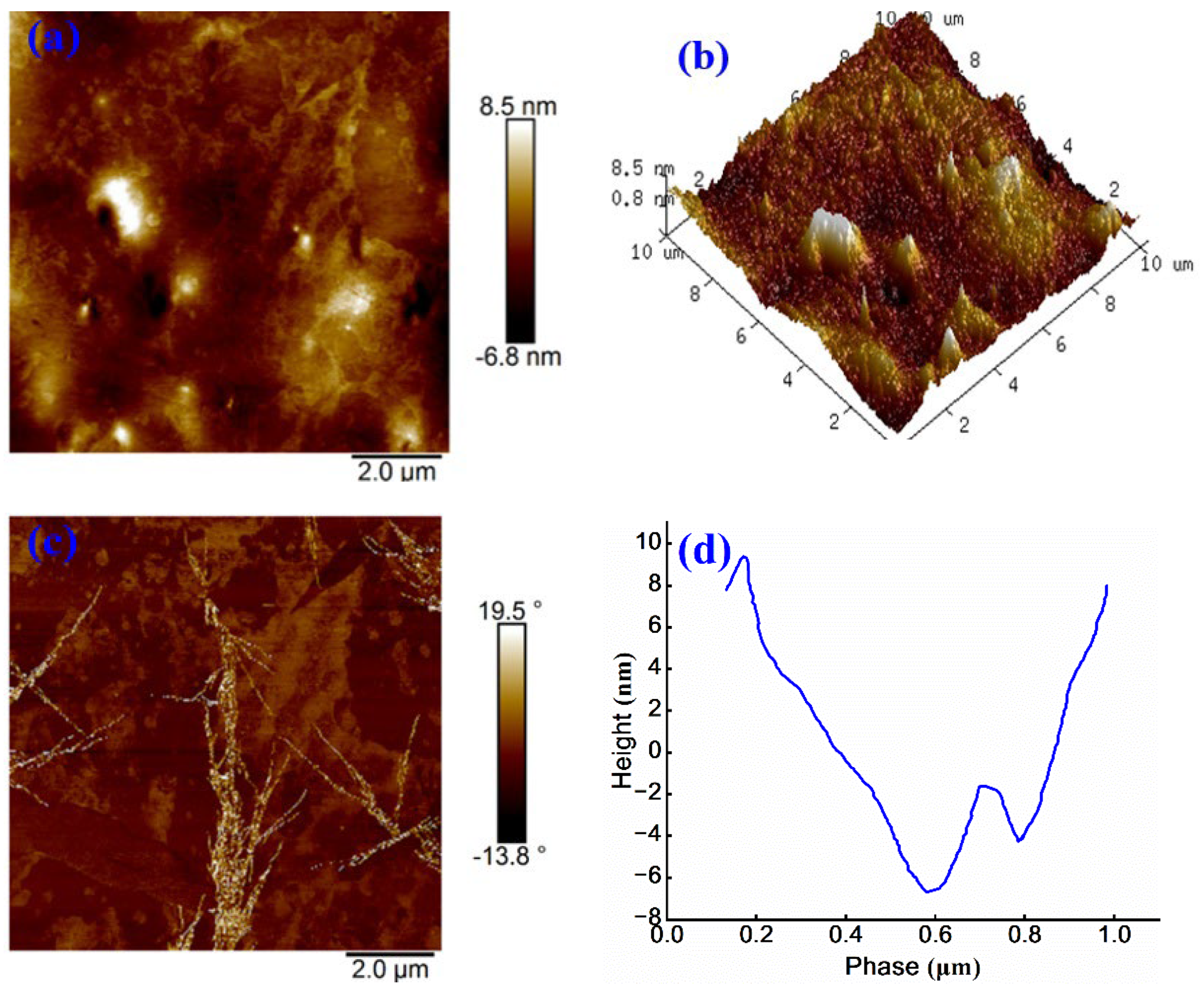

To examine the effect of anionic WPU modification on the microstructure of anionic emulsified asphalt and to facilitate the comparison with previously modified samples, AFM tests are employed for surface characterization. The detailed results are presented in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 11 (a), the continuous and dispersed phases of sample are uniformly distributed, and only a few bright regions are visible. The maximum height variation across the surface is 15.3 nm. Compared to

Figure 10 (a), the number of honeycomb-like structures increases and exhibits a more balanced distribution. Further analysis of

Figure 11 (b) indicates that, relative to 3D images of other anionic emulsified asphalt samples, the surface morphology appears more uniform, suggesting that the introduction of anionic WPU improves the microstructural homogeneity of asphalt.

Figure 11 (c) shows a phase angle ranging from -13.8° to 19.5° and the minimal overall color variation. However, a small “dendritic” bright region is observed, indicating a localized area of significant variation in physical properties within scanned region. This phenomenon may be attributed to sample selection or preparation process 31. As shown in

Figure 11 (d), the phase height difference is approximately 16 nm, which is considerably lower than that in

Figure 10 (d) and comparable to the value in

Figure 9 (d). These results suggest that anionic WPU provides a more favorable modification effect on anionic emulsified asphalt than non-ionic WPU. Overall, these findings strongly support the effectiveness of anionic WPU in enhancing interfacial compatibility, surface uniformity, and microstructural performance of anionic emulsified asphalt.

3.3.2. Influence of WPU on Surface Roughness of Emulsified Asphalt

Although the honeycomb structure can reflect surface undulation of materials to some extent, its characterization range is limited, making it difficult to comprehensively describe the overall morphology and surface microfeatures. In contrast, root mean square (RMS) roughness, a key parameter for quantifying surface irregularities 32-33, is calculated using Equation 5 and Equation 6. RMS roughness not only quantifies the surface roughness of base emulsified asphalt and WPU-modified emulsified asphalt, but also provides a more accurate reflection of their microstructural features and local heterogeneity. Therefore, introducing RMS roughness as a primary characterization metric enhances the understanding of surface morphology and its influence on the functional performance of asphalt materials.

Where, Rq—RMS roughness, nm;—height function,nm;A—scanned area;—reference height,nm;

The RMS roughness of sample is calculated using NanoScope Analysis software, and the results are presented in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 7, anionic emulsified asphalt exhibits the lowest surface roughness of 1.75 nm, while non-ionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt presents the highest value (19.7 nm). The incorporation of WPU generally increases the surface roughness of samples. However, RMS roughness of cationic emulsified asphalt modified with cationic WPU decreases to 4.73 nm. This behavior is attributed to the intrinsic leveling and filling properties of polyurethane, which allow it to fill microscale surface irregularities and produce smoother surfaces. Moreover, WPU can cover or fill uneven substrate areas, reducing surface granularity and overall roughness.

Upon addition to emulsified asphalt, WPU undergoes curing and interacts with phenolic, nitrogen-, oxygen-, and hydrogen-containing functional groups in asphalt, forming hydrogen bonds or other intermolecular interactions 34-35. These interactions enhance the compatibility between WPU and asphalt, facilitating uniform dispersion of WPU within asphalt matrix. As a result, WPU can exert its modifying effect more effectively, improving the flexibility, viscosity, and adhesiveness of asphalt mixture. As these properties improve, the surface roughness tends to decrease because the mixture is more likely to form a uniform and continuous asphalt coating, reducing surface irregularities.

According to AFM test results, anionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt exhibits the lowest surface roughness, indirectly suggesting superior compatibility between anionic WPU and base asphalt. However, the influence of surface roughness change upon adding WPU into emulsified asphalt is uncertain. To optimize the modification effect and achieve controlled surface roughness, further comprehensive studies are necessary, including the selection of appropriate WPU types, dosage optimization, and refinement of emulsified asphalt formulation and preparation conditions.

4. Conclusions

Base on the above experimental results and discussion, main conclusions are summarized as follows.

(1) This study compares three ionic types of WPU based on fundamental performance indicators, clarifying the influence of ionic structure differences on the properties of emulsified asphalt. Compared to base emulsified asphalt, all WPU-modified samples exhibit a reduced penetration, an increased softening point, and a decreased ductility. Among them, non-ionic WPU-modified system enhances material hardness and high-temperature stability but results in the most pronounced low-temperature brittleness, while the cationic WPU maintains a balance between high-temperature stability and low-temperature flexibility.

(2) The intrinsic effect of WPU ionic structure on the storage stability of emulsified asphalt is identified. WPU modification reduces storage stability, which is primarily affected by pH value and particle size of WPU. The cationic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt shows the poorest stability with a residue of 0.7% on sieve, whereas the anionic WPU-modified sample exhibits the best stability with a residue of 0.4% on sieve.

(3) The modification mechanisms by different ionic WPU structures are systematically investigated through FTIR analysis. The results indicate that ionic WPUs alter the functional group composition and polarity distribution of emulsified asphalt via a combination of physical blending and partial chemical reactions. Cationic WPU promotes the formation of ester groups and amide bonds to improve structural stability, and non-ionic WPU enhances the flexibility and wettability, and anionic WPU improves the dispersion.

(4) The microstructural and interfacial morphological effects of ionic WPU on emulsified asphalt are examined using AFM. The results confirm that WPU significantly influences the microstructure and surface roughness of emulsified asphalt. Anionic WPU demonstrates the best dispersion, forming fine and uniformly distributed particles with the lowest surface roughness (5.655 nm, Ra = 1.63 nm). Cationic WPU induces chain-like structures with good curing performance, while non-ionic WPU increases the toughness but leads to greater surface undulation and reduced the uniformity. Distinct regulatory effects on interfacial morphology are observed across different WPU ionic types.

5. Future Directions

This study investigates the properties and compatibility of different ionic WPU-modified emulsified asphalt from both macro- and micro-scale perspectives, elucidating the modification mechanisms and providing a theoretical foundation for WPU applications in emulsified asphalt. However, current research still exhibits limitations, including that key macroscopic performance indicators (e.g., rheological and aging properties) need to insufficiently explore, and a comprehensive analysis of WPU’s influence on asphalt mixture performance is lacking. Future researches should focus on the following directions.

(1) Expanding the research scope. Shifting from material properties to performance evaluation of asphalt mixtures under actual engineering conditions to enhance its applicability.

(2) Enhancing durability assessment. Incorporating critical durability tests (e.g., moisture damage, aging, and freeze-thaw resistance) to evaluate long-term performance.

(3) Deepening mechanistic understanding. Integrating multiscale characterizations and computational models to clarify the interfacial interaction mechanisms between WPU and emulsified asphalt, guiding material design optimization.

These advancements are expected to improve the overall performance of WPU-modified emulsified asphalt and facilitate its broader engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T. and S.H.; methodology, S.H.; software, R.J.; validation, S.H. and R.J.; formal analysis, S.H. and R.J.; investigation, X.Z. (Xiao Zhong); resources, S.H.; data curation, X.Z. (Xiaoxi Zou); writing—original draft preparation, R.J.; writing—review and editing, S.H.; visualization, R.J.; supervision, J.T.; project administration, J.T. and S.H.; funding acquisition, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Innovation Demonstration Project of the Department of Transport of Yunnan Province, grant number 202159.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meng, Y.; Chen, J.; Kong, W.; et al. Review of emulsified asphalt modification mechanisms and performance influencing factors. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, A.; Hayati, P.; Goli, A. ; Advancing Pavement Preservation: Comprehensive Analysis and Optimization of Microsurfacing Mixtures with Stabilizers, Bitumen Types, Emulsifiers, and Fiber Impacts. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; He, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Polyurethane-modified asphalt mechanism. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, G.; He, Y.; et al. Effect of waterborne polyurethane on rheological properties of styrene-butadiene rubber emulsified asphalt[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04022470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Yang, T.; He, Z.; et al. Polyurethane as a modifier for road asphalt: A literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 356, 129058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, X.; Zong, Q.; et al. Chemical, morphological and rheological investigations of SBR/SBS modified asphalt emulsions with waterborne acrylate and polyurethane[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Liu, F.; et al. Investigation of a novel blocked waterborne polyurethane emulsified asphalt mixture for pothole repair: material development, road performance and construction parameters[J]. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; He, Z.; Yu, J.; et al. Rheological Properties and Modification Mechanism of Emulsified Asphalt Modified with Waterborne Epoxy/Polyurethan Composite[J]. Materials. 2024, 17, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gong, X.; Liu, Q. ; Research on rheological properties and modification mechanism of waterborne polyurethane modified bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 371, 130775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Liu, X.; Bi, H.; et al. Study on Preparation and Properties of Polyurethane-Epoxy Composite Emulsion Modified Emulsified Asphalt. 2024 7th International Symposium on Traffic Transportation and Civil Architecture (ISTTCA 2024), Tianjin, China, 21-23 June 2024.

- Xu, P.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, P.; et al. Toughness modification of waterborne epoxy emulsified asphalt by waterborne polyurethane elastomer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 386, 131547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci V, L.; Hormaiztegui M E, V.; Amalvy J, I.; et al. Formulation, structure and properties of waterborne polyurethane coatings: a brief review[J]. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y. ; Preparation and Properties of Waterborne Polyurethane and SBS Composite-Modified Emulsified Asphalt[J]. Applied Sciences. 2024, 14, 7288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirkavand, Hadavand, B. ; Ghobadi, Jola, B.; Didehban, K.; et al. Modified bitumen emulsion by anionic polyurethane dispersion nanocomposites. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2020, 21, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; et al. Property improvement of epoxy emulsified asphalt modified by waterborne polyurethane in consideration of environmental benefits. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Liu, X.; Bi, H.; et al. Effect of evaporation temperature on evaporative residue properties of waterborne polyurethane modified emulsified asphalt. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2024, 2873, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Pang, B.; Jin, Z.; et al. Durability enhancement of cement-based repair mortars through waterborne polyurethane modification: experimental characterization and molecular dynamics simulations[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Effect of ionic emulsifiers on the properties of emulsified asphalts: An experimental and simulation study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Effect of Ionic Emulsifiers on the Stability of Emulsified Asphalt Based on Molecular Dynamics Simulation[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04025024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarkar, H. ; Waterborne polyurethanes: A review. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2018, 39, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yeoh, G, H. ; Kabir, I, I.; Polyurethane Materials for Fire Retardancy: Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Applications. Fire. 2025, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Z.; et al. Interaction between cement and asphalt emulsion and its influences on asphalt emulsion demulsification, cement hydration and rheology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 329, 127220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, A.; Acierno, D. ; Structure-property relationships of waterborne polyurethane (WPU) in aqueous formulations. J. Vinyl Addit Techn. 2023, 29, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yuan, L.; Yi, J. ; Preparation and characterization of polyurethane-modified asphalt containing dynamic covalent bonds. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, W.; Xiang, S.; Bian, R.; et al. Study of MXene-filled polyurethane nanocomposites prepared via an emulsion method[J]. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 168, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Luo, Z.; Bao, J.; et al. Effects of macromolecular diol containing different carbamate content on the micro-phase separation of waterborne polyurethane. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 8639–8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, T.; Wu, J.; et al. Cohesion Performance of Tack Coat Materials between Polyurethane Mixture and Asphalt Mixture[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04023534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, J.; Long, Q.; et al. Healable, Recyclable, and Ultra-Tough Waterborne Polyurethane Elastomer Achieved through High-Density Hydrogen Bonding Cross-Linking Strategy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 16, 64333–64344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xiao, M.; Liu, W. ; Turning things around: from cationic/anionic complexation-induced nanoemulsion instability to toughened water-resistant waterborne polyurethanes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022, 10, 18408–18421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S, M. ; Jadhav, S, M.; Patil, M, J.; et al. Recent developments in waterborne polyurethane dispersions (WPUDs): a mini-review on thermal and mechanical properties improvement. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 5709–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, Z.; Xie, Y.; et al. Fabrication of silane and nano-silica composite modified Bio-based WPU and its interfacial bonding mechanism with cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 371, 130819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Sun, Z.; Liang, F.; et al. Poly (methylmethacrylate) microspheres with matting characteristic prepared by dispersion polymerization. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2019, 24, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Ou, J. ; Investigation on the wetting behavior of asphalt emulsion on aggregate for asphalt emulsion mixture[J]. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, T.; Xu, J.; et al. Effect of polyurethane addition on the dynamic mechanical properties of cement emulsified asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, B.; Dong, F.; et al. Repurposing waste polyurethane into cleaner asphalt pavement materials[J]. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(a) Fourier infrared spectrometer and (b) test samples.

Figure 1.

(a) Fourier infrared spectrometer and (b) test samples.

Figure 2.

(a) Atomic force microscope and (b) test samples.

Figure 2.

(a) Atomic force microscope and (b) test samples.

Figure 3.

Infrared spectra of (a) non-ionic WPU, (b) cationic WPU and (c) anionic WPU.

Figure 3.

Infrared spectra of (a) non-ionic WPU, (b) cationic WPU and (c) anionic WPU.

Figure 4.

Infrared spectra of (a) cationic, (b) non-ionic WPU modified cationic and (c) cationic WPU modified cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 4.

Infrared spectra of (a) cationic, (b) non-ionic WPU modified cationic and (c) cationic WPU modified cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of (a) anionic, (b) non-ionic WPU-modified anionicand (c) anionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of (a) anionic, (b) non-ionic WPU-modified anionicand (c) anionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 6.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 6.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 7.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of non-ionic WPU-modified cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 7.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of non-ionic WPU-modified cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 8.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of cationic WPU-modified cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 8.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of cationic WPU-modified cationic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 9.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 9.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 10.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of non-ionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 10.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of non-ionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 11.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of anionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt.

Figure 11.

(a) Height image, (b) 3D height image, (c) Phase image, and (d) Treatment image of anionic WPU-modified anionic emulsified asphalt.

Table 1.

Basic technical indicators of 70# base asphalt.

Table 1.

Basic technical indicators of 70# base asphalt.

| Technical indexes |

Unit |

Test

results |

Standard

requirements |

Experimental

methods |

| Penetration(25℃, 5s, 100g) |

0.1mm |

70 |

60-80 |

T0604 |

| Ductility (10 ℃) |

cm |

18 |

≥15 |

T0605 |

| Softening point |

°C |

50 |

≥47 |

T0606 |

Table 2.

Parameters of slow-cracking and fast-setting anionic and cationic emulsifiers.

Table 2.

Parameters of slow-cracking and fast-setting anionic and cationic emulsifiers.

| Parameter |

Specification requirements |

Test results |

| Appearance |

Cationic |

Brown viscous liquid |

| Anionic |

Light yellow liquid |

| Active substance content |

Cationic |

70±2

70±2 |

69 |

| Anionic |

70 |

| pH value |

Cationic |

6-8 |

7.6 |

| Anionic |

Free amine

content (%) |

Cationic |

≤2 |

1.25 |

| Anionic |

1.23 |

| Density (g/cm³) |

Cationic |

1.0 |

1.0 |

| Anionic |

1.05 |

1.05 |

Effective

ingredient (%) |

Cationic |

50 |

50 |

| Anionic |

40 |

40 |

Table 3.

Technical index of hydrochloric acid.

Table 3.

Technical index of hydrochloric acid.

| Test specimens |

Hydrochloric acid |

| Chemical formula |

HCl |

| Molecular weight |

36.5 |

| Concentration (%) |

36-38 |

| Color |

Colorless |

| Density (g/cm³) |

1.18 |

Table 4.

Performance index of cationic/anionic emulsified asphalt.

Table 4.

Performance index of cationic/anionic emulsified asphalt.

| Test items |

Quality indicators |

Measured |

| Residual on sieve (1.18mm)/% |

Cationic |

<0.1 |

0.005 |

| Anionic |

0.003 |

| Particle Polarity |

Cationic |

Cationic |

Cationic |

| Anionic |

Anionic |

Anionic |

| Particle size /μm |

Cationic |

≤7 |

4.41 |

| Anionic |

4.30 |

| Standard viscosity / (Pa.s) |

Cationic |

8-25 |

12 |

| Anionic |

15 |

Storage stability

(1d,25℃) /% |

Cationic |

<1 |

0.4 |

| Anionic |

0.3 |

| Content /% |

Cationic |

≥60 |

63.7 |

| Anionic |

62.8 |

| Penetration/(0.1mm) |

Cationic |

40-120 |

75 |

| Anionic |

50-300 |

79 |

| Softening point/℃ |

Cationic |

≥42 |

52.9 |

| Anionic |

53.1 |

| Ductility/cm |

Cationic |

≥40 |

52.5 |

| Anionic |

90.3 |

Table 5.

Performance indexes of different ionic WPU.

Table 5.

Performance indexes of different ionic WPU.

| Type |

Designation |

Solids content(%) |

pH

value |

Viscosity value(mPa.s) |

Color |

Specific gravity (g/cm3) |

| A |

Cationic WPU |

38±1 |

3-7 |

<200 |

Milky white |

1.06±0.02 |

| B |

Anionic WPU |

30±1 |

6-9 |

≥100 |

1.05 |

| 20℃ |

| C |

Nonionic WPU |

6-8 |

>100 |

Table 6.

Performance indexes of WPU modified emulsified asphalt samples.

Table 6.

Performance indexes of WPU modified emulsified asphalt samples.

| Test items |

Ce |

CWpu

+Ce |

Wpu

+Ce |

Ae |

AWpu

+Ae |

Wpu

+Ae |

| Residual on sieve(1.18mm)/% |

0.005 |

0.006 |

0.003 |

0.003 |

0.015 |

0.002 |

| Particle polarity |

C |

C |

C |

A |

A |

A |

Standard viscosity

/ (Pa.s) |

12 |

16 |

15 |

15 |

17 |

16 |

Storage stability

(1d, 25 ℃)/% |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

| Solid content (%) |

65 |

63.7 |

62.8 |

65 |

62.8 |

62.8 |

| Penetration /0.1mm |

75 |

60.3 |

59.3 |

79 |

70 |

63.3 |

| Softening point /℃ |

52.9 |

54.1 |

53.8 |

53.1 |

54 |

53.9 |

| Ductility(15℃)/cm |

52.5 |

43.2 |

36.4 |

90.3 |

44.7 |

28.7 |

Table 7.

Rq values of different emulsified asphalt samples.

Table 7.

Rq values of different emulsified asphalt samples.

| Sample Name |

Ce |

WPU

+Ce |

CWPU

+Ce |

Ae |

WPU+

Ae |

AWPU

+Ae |

Surface

Rq /nm |

7.32 |

13.6 |

4.73 |

1.75 |

19.7 |

1.63 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)