1. Introduction

A high proportion of malignancies occurring in humans demonstrate the absence of a single phosphate and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) allele [

1]. A lipid phosphatase, PTEN inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway, and is well-established as a key tumor suppressor which acts in a dose-dependent manner [

2,

3,

4,

5]. PTEN functions as the catalyst for the transformation of phosphatidylinositol l-3,4,5-trisphosphate into phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate [

2,

6]. Its ability to oppose PI3K-AKT signaling means that PTEN is a key component of numerous intracellular pathways [

4,

7,

8]. PTEN encoding occurs via the tumor suppressor gene at the 10a236 locus. In human malignancy, mutation of this gene is amongst the most commonly occurring [

9,

10,

11], and PTEN is often absent. Contemporary research has noted that post-translational changes, e.g. ubiquitination, as well as genetic mutations and deletions, play a prominent role in the stability of PTEN, together with the protein’s localization and activity [

12,

13,

14].

PTEN downregulation is reliant on the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [

15,

16,

17]. The poly-ubiquitination and degradation of PTEN is regulated by a number of E3 ubiquitin ligases, i.e. NEDD4-1, XIAP, WWP2 and CHIP [

18,

19,

20,

21]. PTEN deubiquitinases include HAUSP, which facilitates the nuclear exportation of PTEN via themono-ubiquitination, ataxin-3, which acts on the protein at the level of transcription; and the cytoplasmic enzymes, USP13 and OTUD3, which have been demonstrated to influence the cytosolic stability of PTEN in breast carcinoma [

22,

23]. In particular, the stability of PTEN is mediated via USP13 through its immediate binding and deubiquitination [

23]. In cell lines from breast carcinoma, the absence of USP13 induces PTEN downregulation which, in turn, stimulates phosphorylation of AKT, cellular replication, anchorage-independent growth, glycolysis and growth of the neoplasm [

23]. Amplified USP13 expression attenuates progression of the malignancy and glycolysis in breast cancer cells which are PTEN-positive as opposed to PTEN-null [

23]. The protein, USP13, has therefore been proposed to suppress malignant growth via its deubiquitinating and stabilizing effect on PTEN [

23].

The aim of this study was to identify any negative relationships between the intensity of immunohistochemical staining for USP13 and factors associated with the progression of prostatic carcinoma.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Specimens

The specimens used in this study were obtained from the hospital between 2002 and 2021. A total of 243 prostate cancer tissue samples were used. 115 consecutive unselected tissue samples extracted at the time of radical prostatectomy (RP) were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin, and used to create a tissue microarray (TMA). Six samples from neighboring benign tissue to the tumor were also included. TMA, obtained from anonymous sources and comprising 128 samples of human prostate carcinoma, gathered at RP, together with 16 samples of benign bordering tissue, were also procured from AccuMax (ISU ABXIS Co., LTD, Seongnam, Korea). Total 22 neighboring benign tissue to the tumor tissue samples were used, compring 6 samples from RP at our hospital and 16 samples purchased from ISU ABXIS Co. For each TMA set, two specialist pathologists reviewed the slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin in order to confirm that they had been correctly labelled as either malignant or non-malignant tissue. The criteria published by the International Union Against Cancer and World Health Organization/ International Society of Urological Pathology were used to determine the cancer stage and Gleason score for each individual. Additional clinical data collected included the patient’s age, the presence of seminal or lymph node invasion and serum PSA titers. Patients were monitored for a median period of 67.43 months (range: 0.30 – 162.10 months) following RP; serum PSA was assayed at intervals. The regional scientific ethics committee gave approval for the study. (Seoul hospital: 2017-02-002, Bucheon hospital: 2017-03-004, Cheonan hospital: 2017-03-031-024, Gumi hospital: 2017-03-031-002).

2.2. Immunohistochemical Staining of Tissue Microarrays

The TMAs obtained from patients with prostatic carcinoma and the controls were evaluated, and consecutive slices, 3 µM in thickness, were sectioned. A specific rabbit anti-USP13 polyclonal antibody (sc514416, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) was the primary antibody selected for the immunohistochemical analysis of USP13 expression. ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics) was utilized in order to measure the density of antibody staining; the average staining intensity, and the proportion of cells exhibiting positive staining, were recorded.

Benign tissue samples from the prostate were assigned as positive controls. Two core samples from each patient were encompassed within each TMA. The paraffin sections from the TMA were dewaxed and rehydrated with xylene and alcohol, respectively, and then submerged in 0.01 M tri-sodium citrate solution in Coplin jars. These were warmed in a traditional pressure cooker for 3 minutes, and then washed for 5 minutes in cold running water, followed by tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4. Overnight incubation was performed with a 1: 100 dilution of the primary anti-USP13 antibody. The sections of tissue underwent staining firstly, with biotinylated anti-rabbit immunoglobulins, and secondly, with peroxidase-labelled streptavidin (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). The substrate used to obtain a readable signal was diaminobenzidine chromogen. Negative controls were generated using incubations in which the specific antibody was either excluded or preadsorbed. The expression of USP13 was deliberately only assessed on tissue core samples that were sufficiently preserved. The reporting pathologist was blinded to clinical endpoint data. USP13 staining intensity was scored for each histological cohort from grades 0 to 3, respresenting negative, low, medium or high, respectively.

2.3. Survival Analysis

A rise in serum PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/mL on a minimum of 2 serial assays separated by 3 months or more was considered to represent biochemical recurrence. Any malignant skeletal deposits identified on a radionuclide bone scan, or enlarged lymph nodes or deposits within the viscera observed on abdominal, pelvic or thoracic computed tomography scanning were deemed indicative of clinical recurrence. The period of risk was defined as the date of the patient’s RP until either recurrence was diagnosed or the date of the patient’s final serum PSA assay. The last day of follow-up or final PSA investigation was the point of censorship where patients were lost to follow-up. Overall survival (OS) time was documented, i.e. the period from RP to death from any cause.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The baseline covariates were analyzed initially, and any relationships between the USP13 cohort and the factors influencing prognosis were assessed. The categorized data were analyzed with the use of chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, and given in a descriptive statistical format, i.e. n (%). Continuous data were evaluated utilizing Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (1st, 3rd quartile). A Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was carried out, encompassing the biochemical or clinical recurrence data and the OS statistics. The Kaplan-Meier technique was used to plot the OS curves, and a log-rank test utilized for their comparison. In order to establish any independent relationships between OS and the expression of USP13, Cox’s proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to establish the independent prognostic effect of the USP13 cohort, according to the age of the patient when diagnosed, histological grade, disease stage, PSA level, positivity of surgical margin and any extension to the lymph nodes. The adjusted influence of USP13 was carried out using a stepwise selection in relation to the multivariate analysis. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 6, and Rex, version 3.5.0 (Resift Inc., Seoul, Korea) were used for statistical analyses. A p value < 0.05 was deemed to represent statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Patients with Prostatic Cancer and USP13 Expression

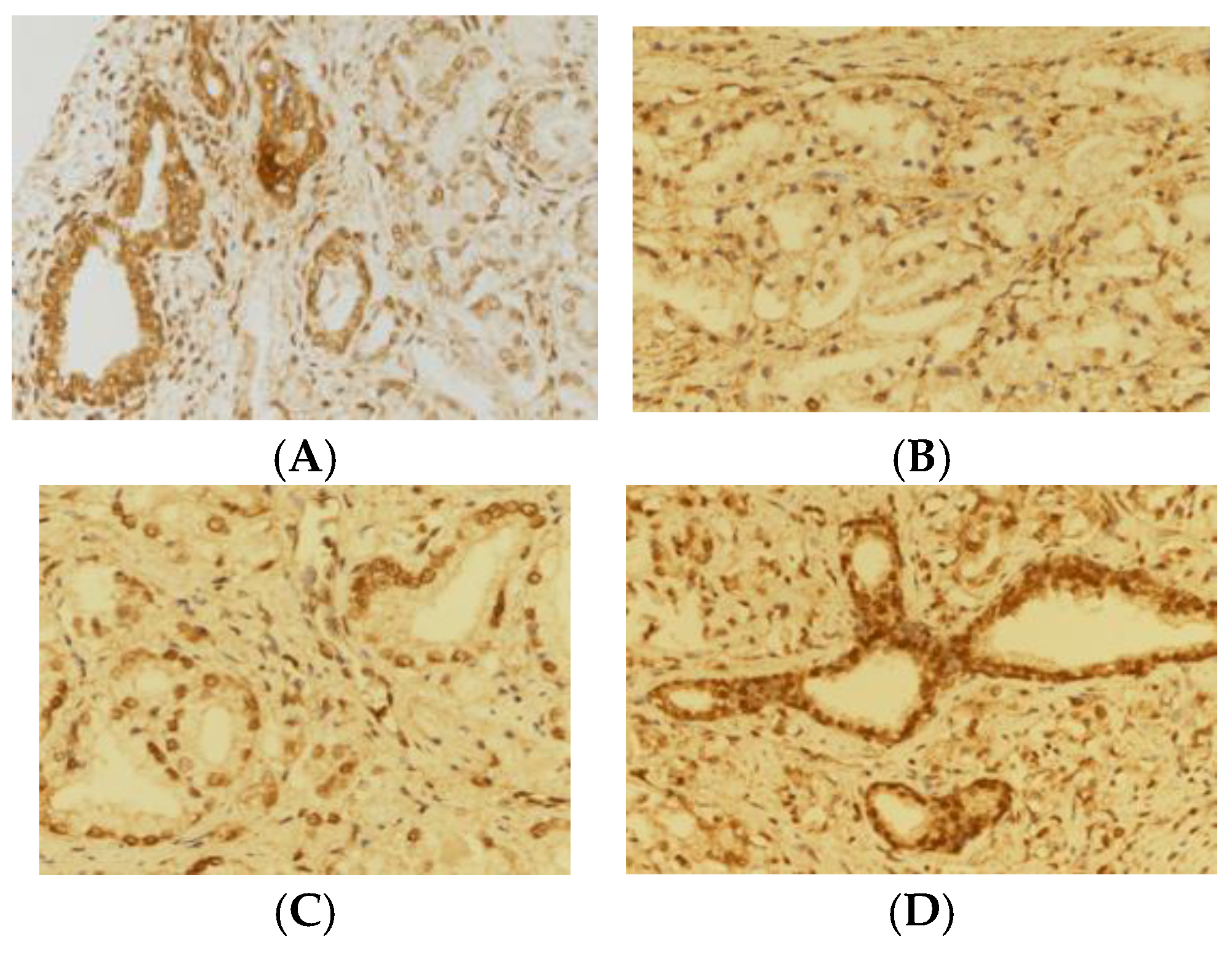

265 TMAs were analyzed in total, which included 243 containing prostatic carcinoma, and 22 with benign bordering tissue (

Table 1). Out of 265 TMAs, 264 TMAs were successfully stained with USP13 immunohistochemical staining. USP13 staining scores of 3, and either 1 or 2, were exhibited by 46 and 218 samples, respectively. USP13 staining scores of 1, and either 2 or 3, were exhibited by 82 and 182 samples, respectively. In both group analyses, the higher grade was seen in the benign samples, and the lower grades in the samples from malignant tissue (p < 0.001) (

Table 1,

Figure 1).

USP13 expression grading, as either low (grades 0-2) or high (grade 3), was feasible in 242 of the patients with malignancy; one could not be analyzed owing to inadequate data (

Table 2). The median patient age in this group was 65.0 years (60, 70). Serum PSA levels within this group were: ≤ 10, n = 168 (69.14%); 10-20, n = 40 (16.46%); > 20, n = 35 (14.40%). The distribution of the Gleason score was as follows: ≤ 6, n = 24 (9.88%); 7, n = 107 (44.03%); 8-10, n = 112 (46.09%). Seminal invasion was present in 45 (18.60%). 241 (99.18%) patients had no lymph node involvement. Pathological stages of ≤T2 and ≥T3 were seen in 48 (19.75%) and 195 (80.25%) patients, respectively. The different USP13 categories exhibited no significant differences with respect to the baseline data (

Table 2).

It was only possible to perform survival analysis in 115 subjects (

Table 3) and for the presence of either biochemical or clinical recurrence and survival, in only 115. The median age of this group was 66.64 (64.5, 75.0) years. Serum PSA levels within this group were: ≤ 10, n = 53 (46.09%); 10-20, n = 35 (30.43%); > 20, n = 27 (23.48%). The Gleason score was distributed as follows: ≤ 6, n = 20 (17.39%); 7, n = 64 (55.65%); 8-10, n = 31 (26.96%). A pathological stage of ≤T2 was present in 47 (40.87%) patients, and of ≥T3 in 68 (59.13%). Seminal invasion was evident in 14 (12.17%) patients and undetected in 101 (87.83%). 2 (1.74%) patients had lymph node involvement, 113 (98.26%) had no spread to the lymph nodes. Negative and positive surgical margins were recognized in 64 (55.65%) and 51 (44.35%), respectively. The different USP13 categories demonstrated no significant differences with respect to the baseline data. 14 (12.71%) of these patients presented with biochemical recurrence, of whom 12 were in grades 1-2, and 2 in grade 3. 3 patients were diagnosed with a clinical recurrence, all of which were in the USP13 grades 1-2 category. Fatality numbered 18 (20.48%), of whom 14 were in the USP13 grades 1-2 cohort, and 4 were in grade 3, showing no significant difference between the two groups. Even when the categories were reanalyzed by grouping grade 1 separately from grades 2 and 3, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of biochemical recurrence, clinical recurrence, or mortality.

3.2. Cox Proportional Hazard Model

Biochemical Recurrence

The data from this analysis are presented in

Table 4. Following univariate analysis, when compared with grade 3, the grade 1 -2 cohort had a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.958 (95% CI: 0.239 - 16.029, p = 0.531), which failed to reach statistical significance. The hazard ratios for the PSA categories were as follows: 10-20, HR = 1.265 (95% CI 0.079 – 20.281, p = 0.868); > 20, HR = 8.575 (95% CI: 0.130 – 71.340, p = 0.047). The statistical significance was not achieved even when the analysis was conducted by dividing the groups. Hazard ratios for pathological T stage and seminal vesicle invasion, which had a significant effect size, were 9.230 (95% CI: 1.135 – 75.084, p = 0.038) and 4.981 (95% CI: 1.233 – 20.121, p = 0.038).

Although a greater effect size was seen in relation to USP13 following multivariate analysis, it failed to reach significance (HR = 9.241, 95% CI: 0.973 - 87.815, p = 0.053). A single unit change in height and weight gave rise to a 0.858-times decrease (95% CI: 0.734 - 1.003, p = 0.055) and 1.777-times rise (95% CI: 1.047 - 1.324, p=0.007), respectively, in the likelihood of biochemical recurrence. The ultimate model additionally incorporated data for PSA level and pathological T stage: PSA 10-20, HR = 1.980 (95% CI: 0.103 - 38.059, p = 0.651); PSA > 20, HR = 11.852 (95% CI: 1.044 - 134.589, p = 0.046); pathological T stage, HR = 5.427 (95% CI: 0.577 - 51.081, p = 0.139).

3.3. Overall Survival

The overall survival data are shown in

Table 5. Following a comparison of the USP13 staining intensities, grade 1-2 versus grade 3, both univariate (HR = 1.666, 95% CI: 0.476 - 5.831, p=0.425) and multivariate (HR = 1.938; 95% CI: 0.544 - 6.896, p = 0.307) analyses failed to demonstrate statistical significance, although a trend towards a rise was seen in the latter. With each year in age difference, the likelihood of death rose by a factor of 1.089 (95% CI: 0.987 - 1.202, p = 0.088).

3.4. Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis

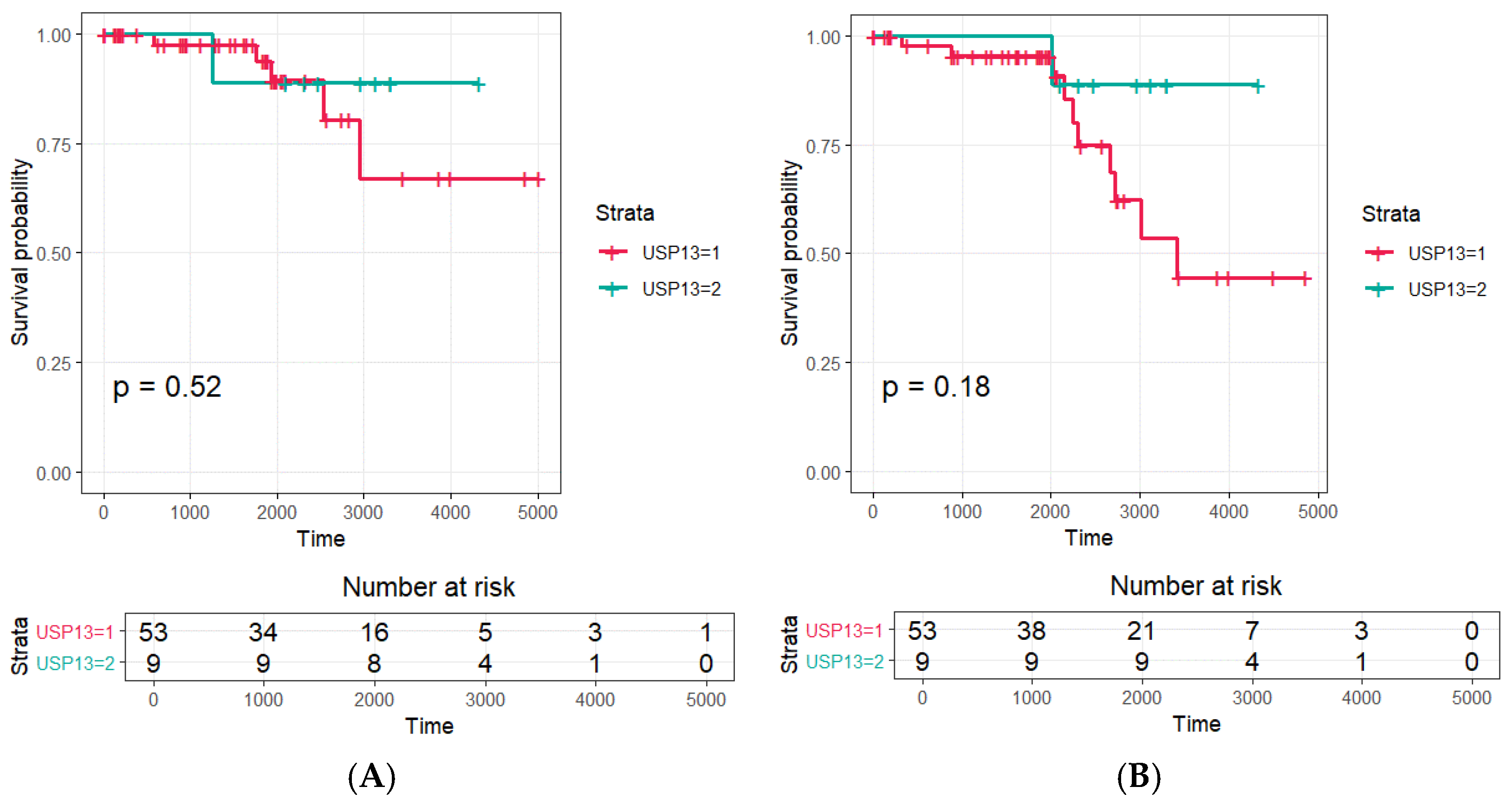

The Kaplan-Meier survival data and the results of the log-rank test for the expression of USP13 in patients with prostatic carcinoma are illustrated in

Figure 2. Mean ± SD times to biochemical recurrence for the USP13 grade 3 and grades 1-2 groups were 11.10 ± 0.73 years and 11.94 ± 0.65 years (p – 0.351), respectively. Mean ± SD times to clinical recurrence for the USP13 grade 3 and grades 1-2 cohorts were 12.51 ± 0.47 years and 10.05 ± 0.68 years (p = 0.420), respectively. The Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a correlation between the USP immunohistochemical staining grade, and biochemical or clinical recurrence, and OS, although this failed to reach significance using the log-rank test.

4. Discussion

In the samples examined in this research, USP13 staining grades 2 and 3 were seen in all the histology specimens of benign tissue obtained from areas adjacent to prostatic tumor tissue. In contrast, USP13 grades 1 and 2 were seen in 88.6% (p < 0.001) of samples containing malignant prostatic tissue (

Table 1,

Figure 1). This difference suggests that is possible for USP expression to distinguish between neoplastic and benign tissues. These data also substantiate the part played by deubiquitination in the disease processes underlying prostate cancer, and in the replication of malignant prostatic cells.

Compared to individuals with a higher USP13 grade, patients exhibiting a lower USP13 grade failed to demonstrate more elevated serum PSA titers, a higher Gleason’s score, more advanced disease stage, or additional lymph node or seminal vesicle involvement. Similarly, the survival analysis revealed that in comparison to their high-grade USP13 counterparts, the group with a low USP13 staining intensity did not exhibit increased serum PSA titers, a higher Gleason’s score, more advanced disease stage, lymph node or seminal vesicle involvement, a positive surgical margin, more frequent biochemical or clinical recurrence, or higher mortality rates. Given the immunohistochemical staining intensity for USP13, the prostate carcinoma prognosis was not anticipated (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

No correlations between USP13 expression, as determined using the immunohistochemical staining technique, and either freedom from biochemical recurrence or OS were found using Cox proportional hazard modeling (

Table 4 and

Table 5). USP13 expression exhibited a relationship with biochemical and clinical recurrence, as well as OS in this group of patients with prostatic carcinoma. However, these associations failed to reach statistical significance on log-rank testing (

Figure 2). In this study, there was a low death rate amongst the studied cohort over the study’s follow-up period, which was assumed to related to the small population of patients investigated.

Although in human neoplasms, the PTEN protein is commonly found to exhibit genetic variations, only a quarter of patients with malignancy demonstrate an association between PTEN protein absence and its mRNA loss [

24,

25,

26], a finding which highlights the post-transcriptional and post-translational import of PTEN modulation. The expression, activity and site of PTEN can be influenced by mono- or poly-ubiquitination, phosphorylation, sumoylation and acetylation, and controlled by non-coding RNAs [

4,

12,

13]. Contemporary research has demonstrated that both ubiquitination and deubiquitination processes moderate the characteristics and activity of PTEN [

4,

12,

13].

USP13 catalyzes PTEN poly-ubiquitination reversal, stabilizing the protein and facilitating the suppression of malignancy. Carcinogenesis is enhanced in the absence of USP13 occurring via PTEN downregulation. Consequently, the anti-cancer properties of USP13 vary according to the status of the PTEN protein. In human breast carcinoma, downregulation of USP13 has been observed, and correlates with PTEN protein concentrations [

23].

This research demonstrated that tissue expression of USP13, using an immunohistochemical technique, can be used to distinguish benign and malignant tissues in samples obtained from patients with prostatic carcinoma. USP13 is mostly found within the cell cytoplasm or attached to the cell membrane [

23], loci which are in keeping with its PTEN poly-ubiquitination reversal functions at these sites [

23].

In comparison to p53, PTEN is a more stable protein. However, amplification of PTEN ubiquitin ligases, or PTEN deubiquitinase downregulation can hasten its breakdown. In human breast carcinoma, downregulation of USP13 is evident, which is consistent with the degree of PTEN expression. Consequently, carcinogenesis may be promoted by the absence of USP13 in breast tissues exhibiting heterozygous PTEN inactivation [

23]. It was therefore unsurprising to find that UPS13 staining intensity and prostatic carcinoma progression were negatively correlated, together with relationships between USP13 expression and PSA level, Gleason’s score and disease stage, as amplified USP13 expression can suppress the advancement of prostatic malignancy.

However, contrary to our hypothesis, the correlation between UPS13 expression and both tumor malignancy and clinical prognosis was not consistently observed. One possible explanation for USP13 not showing an association with clinical outcomes and pathological features is that this protein may play a role only in specific biological pathways, which may not be directly related to clinical prognosis. Although USP13 may be involved in particular metabolic processes or molecular variations within cancer cells, its effects might not align with the clinical indicators we investigated. Additionally, due to the complex biological nature of cancer, various factors can influence prognosis, and the role of USP13 could have been diluted by other variables. Another possible explanation is that while USP13 expression may generally be lower in malignant tissues compared to benign ones, its overexpression in specific cancer subgroups (e.g., those with high PSA levels or high Gleason scores) could indicate a role in cancer progression or aggressiveness. This dual behavior of USP13—low expression in most cancer tissues but higher expression in more aggressive cancers—presents an important area for further investigation.

In this study, we investigated the expression of USP13 in prostate cancer patients. Our study has several limitations. One limitation of our study is the relatively small number of patients included in the study, along with a relatively short follow-up period. Out of the total 265 tissue microarray (TMA) samples used in the study, only 115 patients were included in the survival analysis, which is relatively small. This may hinder the ability to sufficiently detect effect sizes in statistical analyses. This limitation could particularly explain the lack of statistical significance in the correlation between USP13 expression and survival or recurrence rates Additionally, the number of high-grade prostate cancer cases was limited, which may have impacted the ability to detect statistically significant outcomes, especially in the context of survival and recurrence analyses. These factors could limit the generalizability of the findings. Lack of clear results based on USP13 expression. This study failed to achieve statistical significance regarding the prognostic relevance of USP13 expression levels in prostate cancer. Although Kaplan-Meier survival analysis identified a relationship between USP13 expression grades and biochemical or clinical recurrence, as well as overall survival (OS), the log-rank test did not show any significant differences, limiting the conclusions drawn from the study. These limitations suggest that caution is required when interpreting and applying the study's findings.

However, we emphasized these findings and suggests that the role of USP13 in prostate cancer may be more complex than initially expected, potentially impacting cancer aggressiveness. Further research is needed to determine under what circumstances USP13 could serve as a stronger prognostic factor.

5. Conclusions

In this study, it was established that benign tissues which border prostatic carcinoma tissue can be between distinguished from the latter using USP13 staining density. Immunochemical staining for USP13 expression could therefore be utilized as a screening test in this context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W.L. and Y.S.S.; Methodology, J.H.K. and Y.S.S.; Software, E.H. and A.M.; Validation, A.M. and Y.S.S.; Formal Analysis, S.P.; Investigation, J.H.K., H.J.Y. and A.M.; Resources, J.H.K. and K.W.L.; Data Curation, S.P. and E.H.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, J.H.K. and H.J.Y.; Writing – Review & Editing, all authors.; Visualization, H.J.Y.; Supervision, A.M. and Y.S.S.; Project Administration, J.H.K., H.J.Y., K.W.L. and Y.S.S.; Funding Acquisition, Y.S.S.

Funding

This research was supported by grant from the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (RS-2024-00333544).

Data Availability Statement

The data used and/or analyzed in this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Y.S.S) due to ethical reasons.

Consent to participate

We were been granted a waiver of informed consent by the local scientific ethics committees for the following reasons; 1) The study did not conduct genetic testing of human origin. 2) The subject of the study is human-derived, and the identification of the samples is not possible because the information of the subject was not provided or was not revealed to all research-related persons. 3) Information was coded and provided to the researcher without the subject identification record, or the personal information was processed and secured so that it was impossible to identify it by an impartial third party.

Ethics Approval

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from the local scientific ethics committees (Soonchunhyang University Seoul hospital, Bucheon Hospital, Cheonan Hospital, Gumi Hospital).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Salmena, L.; Carracedo, A.; Pandolfi, P.P. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell 2008, 133, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maehama, T.; Dixon, J.E. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 13375–13378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambolic, V.; Suzuki, A.; de la Pompa, J.L.; Brothers, G.M.; Mirtsos, C.; Sasaki, T.; Ruland, J.; Penninger, J.M.; Siderovski, D.P.; Mak, T.W. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell 1998, 95, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Salmena, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012, 13, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, K.; Nonomura, N. Systemic Therapies for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: An Updated Review. World J Mens Health 2023, 41, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leevers, S.J.; Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Waterfield, M.D. Signalling through phosphoinositide 3-kinases: the lipids take centre stage. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1999, 11, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cristofano, A.; Pesce, B.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Pandolfi, P.P. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet 1998, 19, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cao, I.; Song, M.S.; Hobbs, R.M.; Laurent, G.; Giorgi, C.; de Boer, V.C.; Anastasiou, D.; Ito, K.; Sasaki, A.T.; Rameh, L.; et al. Systemic elevation of PTEN induces a tumor-suppressive metabolic state. Cell 2012, 149, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, D.; Marsh, D.J.; Li, J.; Dahia, P.L.; Wang, S.I.; Zheng, Z.; Bose, S.; Call, K.M.; Tsou, H.C.; Peacocke, M.; et al. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nat Genet 1997, 16, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yen, C.; Liaw, D.; Podsypanina, K.; Bose, S.; Wang, S.I.; Puc, J.; Miliaresis, C.; Rodgers, L.; McCombie, R.; et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science 1997, 275, 1943–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, P.A.; Pershouse, M.A.; Jasser, S.A.; Yung, W.K.; Lin, H.; Ligon, A.H.; Langford, L.A.; Baumgard, M.L.; Hattier, T.; Davis, T.; et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet 1997, 15, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, X. Post-translational regulation of PTEN. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5454–5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fata, J.E.; Debnath, S.; Jenkins, E.C., Jr.; Fournier, M.V. Nongenomic Mechanisms of PTEN Regulation. Int J Cell Biol 2012, 2012, 379685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Salmena, L.; Carracedo, A.; Egia, A.; Lo-Coco, F.; Teruya-Feldstein, J.; Pandolfi, P.P. The deubiquitinylation and localization of PTEN are regulated by a HAUSP-PML network. Nature 2008, 455, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.Y.; Dai, C.J.; Wu, W.L.; Gao, J.H.; Xia, A.J.; Liu, G.P.; Lv, K.S.; Wu, C.L. USP11 regulates p53 stability by deubiquitinating p53. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2014, 15, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Tan, X.; Shi, Y.; Xu, G.; Mao, R.; Gu, X.; Fan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Burlingame, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. USP11 negatively regulates TNFalpha-induced NF-kappaB activation by targeting on IkappaBalpha. Cell Signal 2010, 22, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Liu, C.H.; Chung, H.C.; Wang, Y.T.; Lin, Y.W.; Ma, H.I.; Tu, P.H.; Lawler, S.E.; Chen, R.H. USP11 regulates PML stability to control Notch-induced malignancy in brain tumours. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Trotman, L.C.; Koppie, T.; Alimonti, A.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; et al. NEDD4-1 is a proto-oncogenic ubiquitin ligase for PTEN. Cell 2007, 128, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddika, S.; Kavela, S.; Rani, N.; Palicharla, V.R.; Pokorny, J.L.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Chen, J. WWP2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for PTEN. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Deb, S.; Paul, I.; Chatterjee, A.; Mandal, T.; Chatterjee, U.; Ghosh, M.K. The chaperone-assisted E3 ligase C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) targets PTEN for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 15996–16006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Themsche, C.; Leblanc, V.; Parent, S.; Asselin, E. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) regulates PTEN ubiquitination, content, and compartmentalization. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 20462–20466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Lv, Y.; Li, H.; Gao, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, G.; Kong, X.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Deubiquitylase OTUD3 regulates PTEN stability and suppresses tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Wei, Y.; Piao, H.L.; Wang, W.; Maddika, S.; Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Sun, Y.; Hung, M.C.; et al. Deubiquitylation and stabilization of PTEN by USP13. Nat Cell Biol 2013, 15, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Paluch, B.E.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X. PTEN at a glance. J Cell Sci 2012, 125, 4687–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanayama, M.; Nakao, K.; Horie, S.; Aiba, A. Generation of transgenic mouse line with prostate-specific expression of codon-improved Cre recombinase. Prostate International 2018, 6, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatano, K.; Nonomura, N. Genomic Profiling of Prostate Cancer: An Updated Review. World J Mens Health 2022, 40, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).