Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| Material | Aex, pJ/m | Ms, MA/m | Kс1, J/m3 | Kс2, J/m3 | lex, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe (293 K) | 21.0 | 1.75 | 52.0∙103 | 0.1∙103 | 3 |

3. Results and Discussion

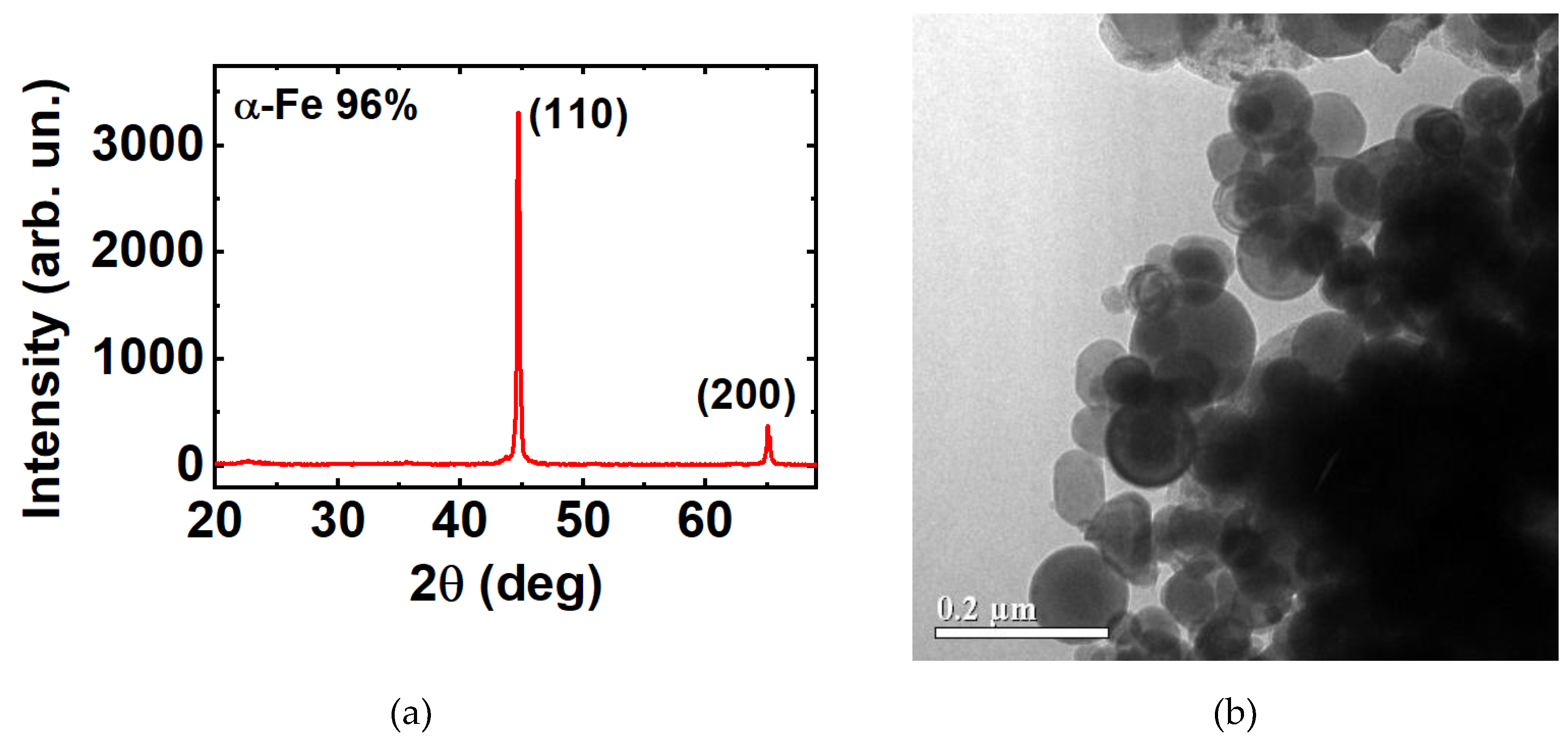

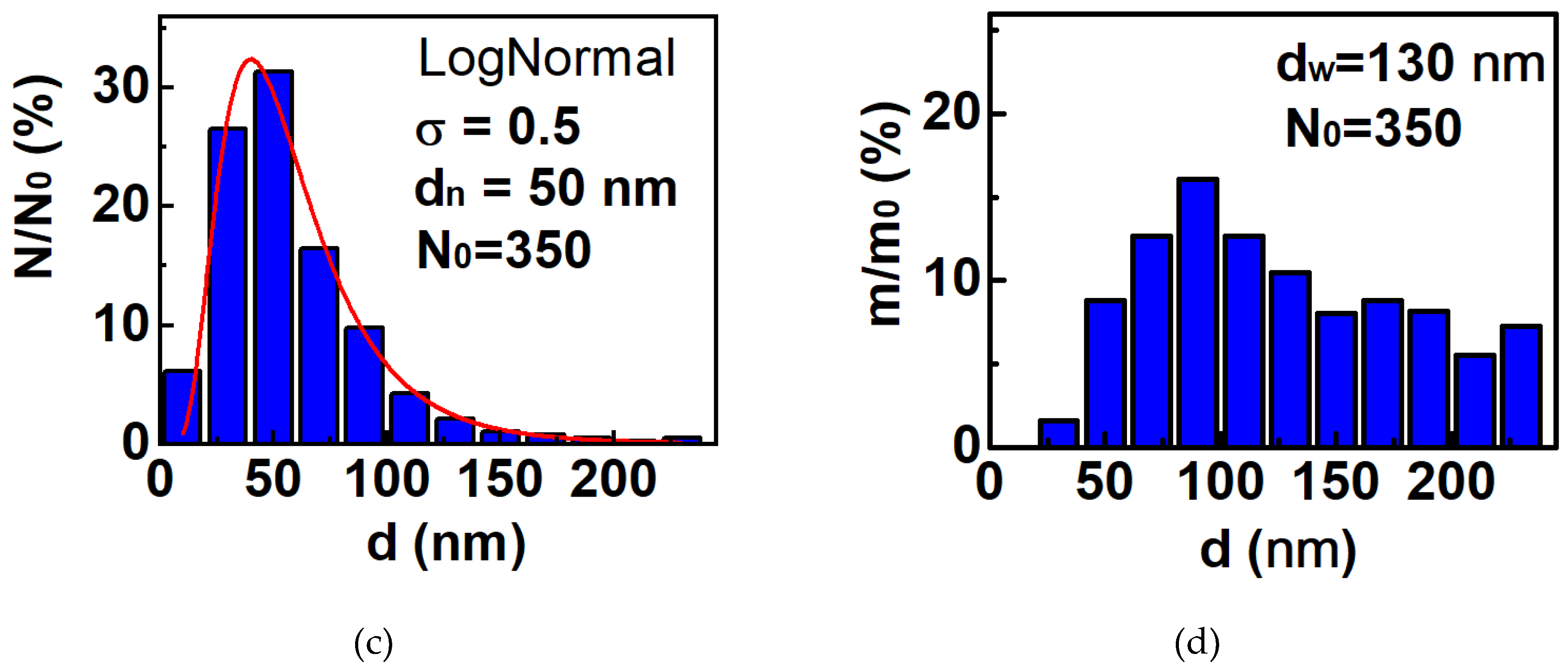

3.1. Structure and Morphology of Fe nanoparticles

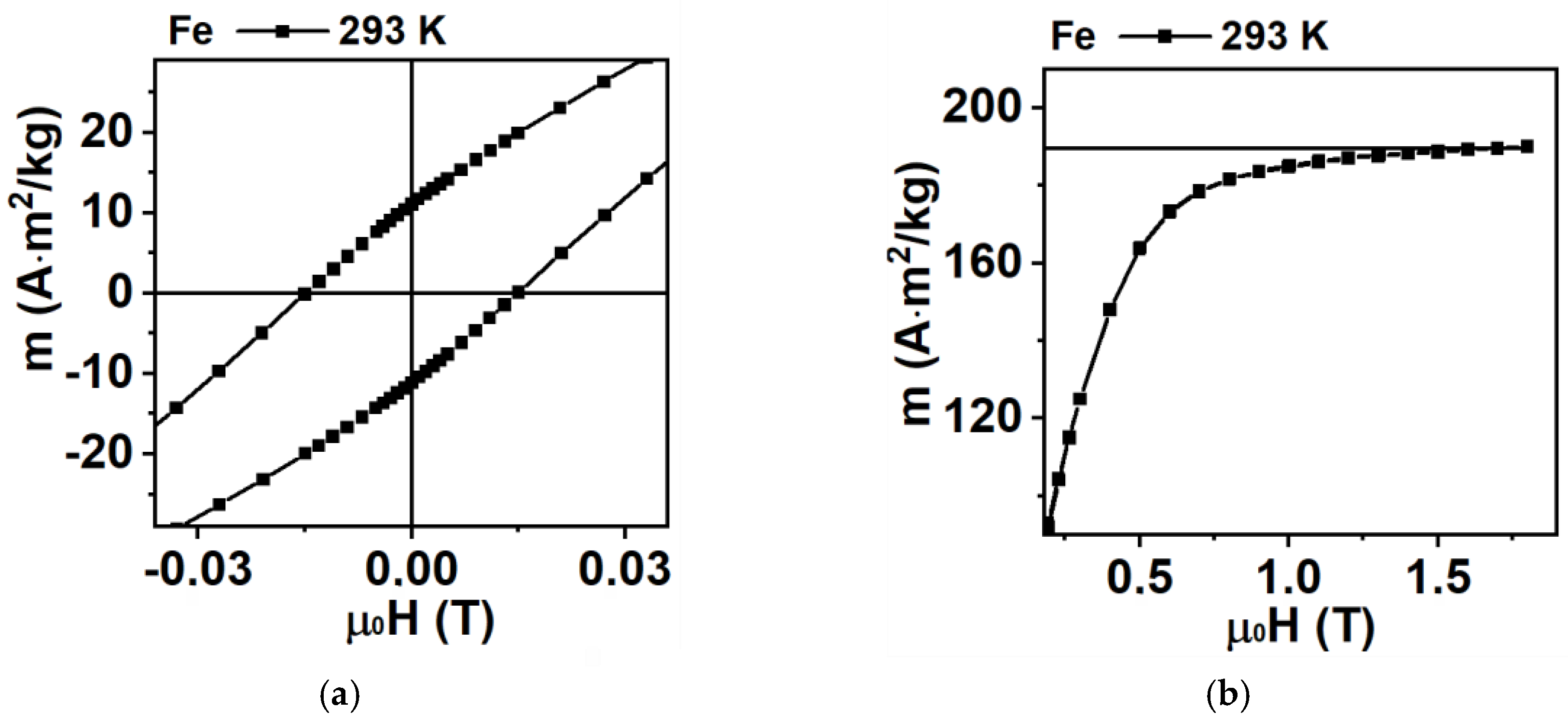

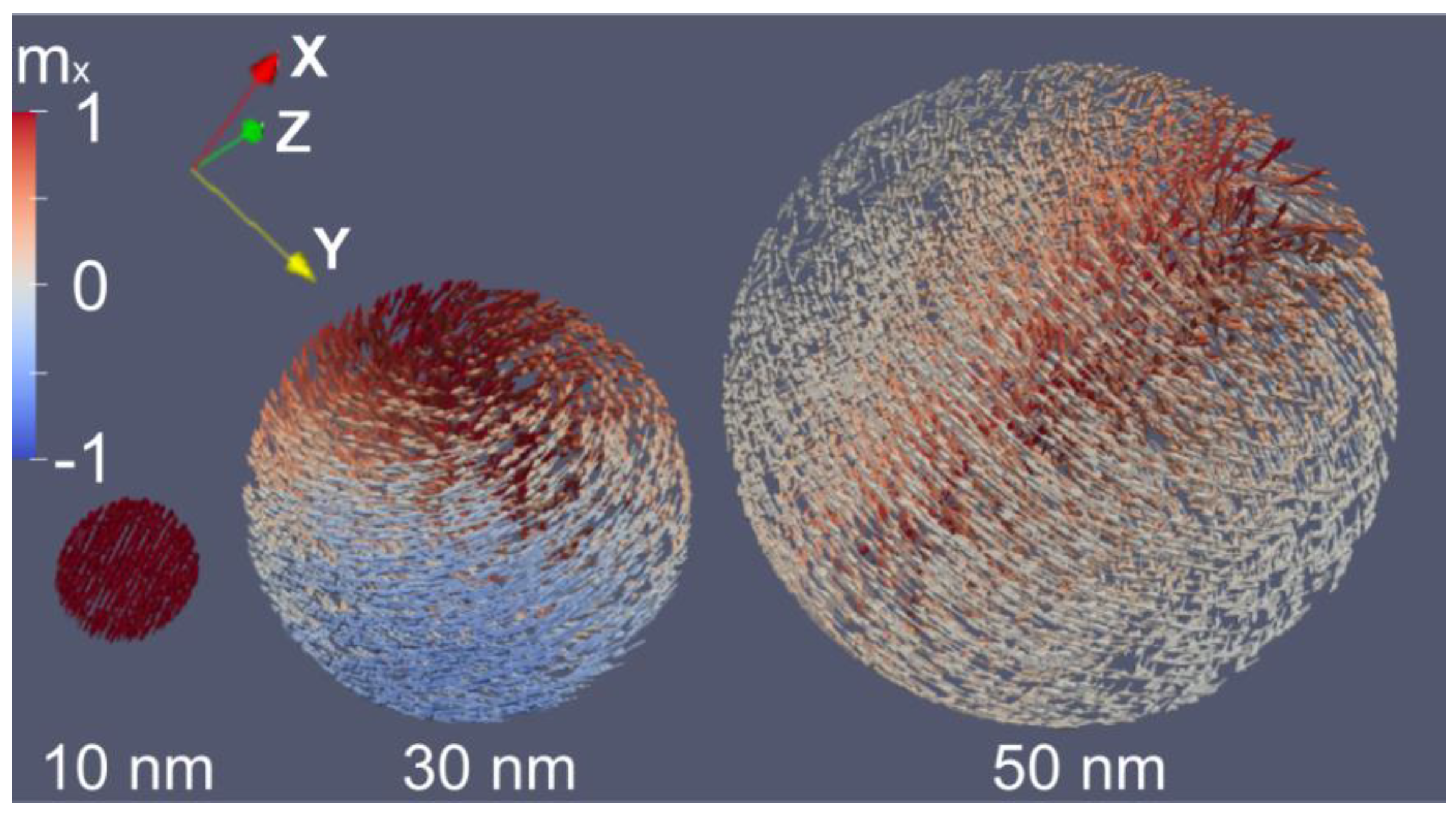

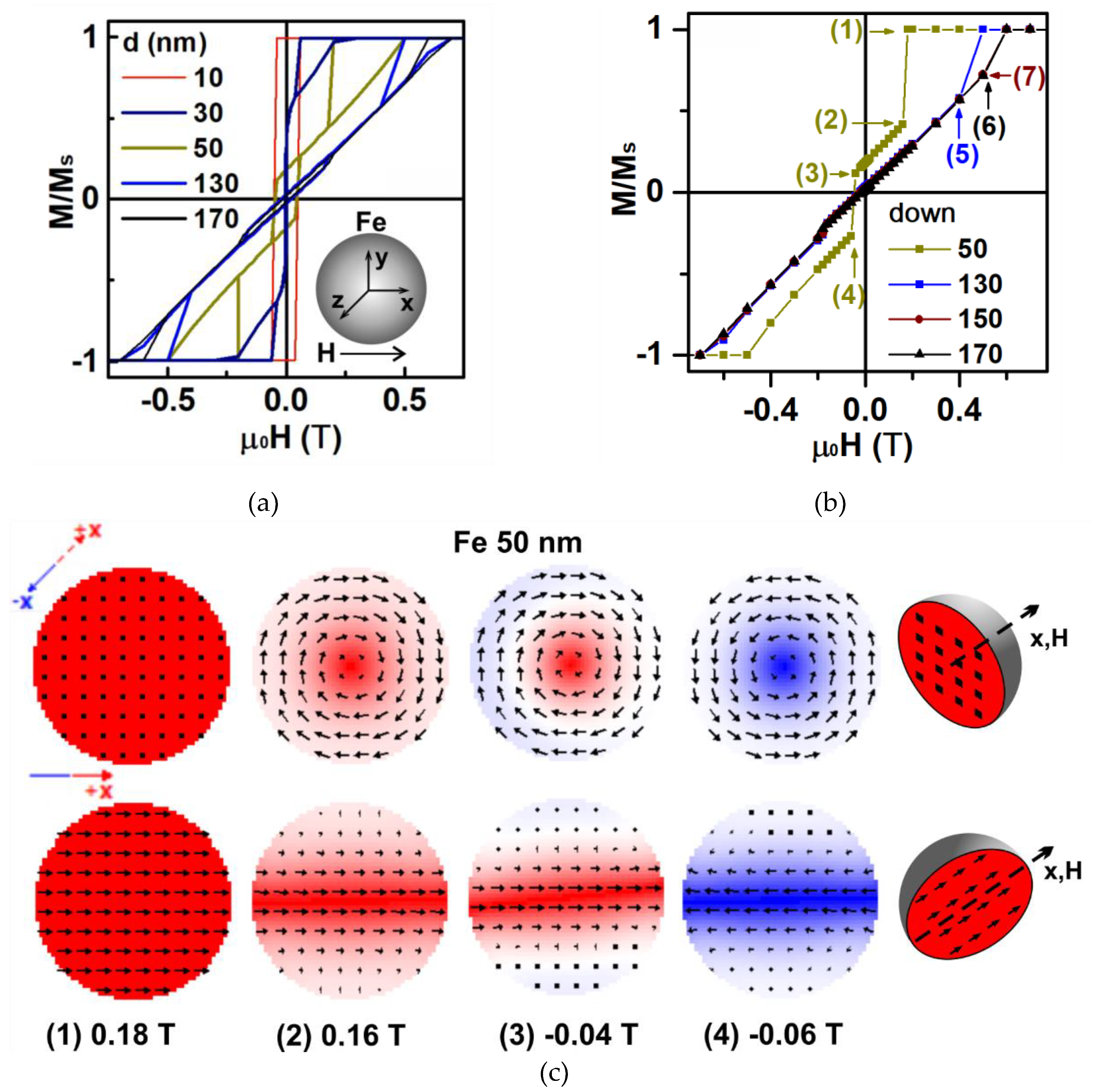

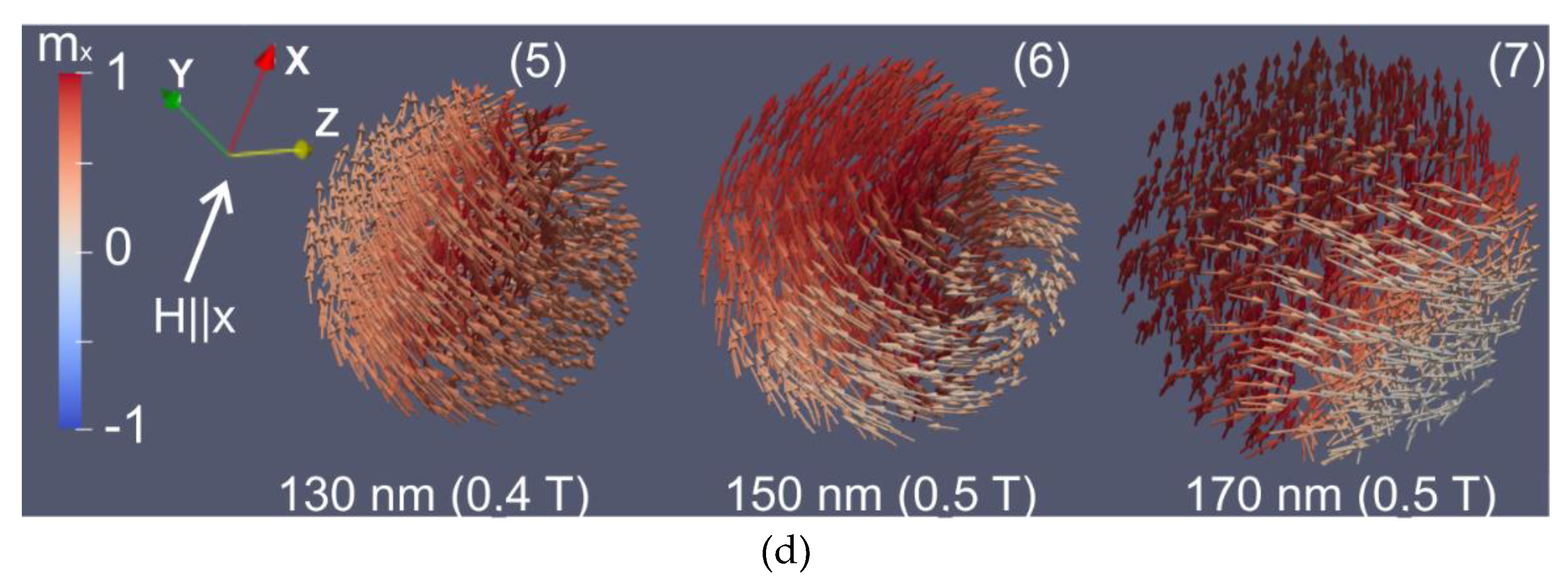

3.2. Magnetic properties of Fe nanoparticles: simulation and experiment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamzin, A.S.; Valiullin, A.A.; Khurshid, H.; Nemati, Z.; Srikanth, H.; Phan, M.H. Mössbauer Studies of Core-Shell FeO/Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Phys. Solid State 2018, 60, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlyandskaya, G. V.; Novoselova, I.P.; Schupletsova, V. V.; Andrade, R.; Dunec, N.A.; Litvinova, L.S.; Safronov, A.P.; Yurova, K.A.; Kulesh, N.A.; Dzyuman, A.N.; et al. Nanoparticles for magnetic biosensing systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 431, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovin, Y.; Golovin, D.; Klyachko, N.; Majouga, A.; Kabanov, A. Modeling drug release from functionalized magnetic nanoparticles actuated by non-heating low frequency magnetic field. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, G.Y.; Lepalovskij, V.N.; Svalov, A. V.; Safronov, A.P.; Kurlyandskaya, G. V. Magnetoimpedance thin film sensor for detecting of stray fields of magnetic particles in blood vessel. Sensors 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spizzo, F.; Sgarbossa, P.; Sieni, E.; Semenzato, A.; Dughiero, F.; Forzan, M.; Bertani, R.; Del Bianco, L. Synthesis of ferrofluids made of iron oxide nanoflowers: Interplay between carrier fluid and magnetic properties. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekino, M.; Kuwahata, A.; Ookubo, T.; Shiozawa, M.; Ohashi, K.; Kaneko, M.; Saito, I.; Inoue, Y.; Ohsaki, H.; Takei, H.; et al. Handheld magnetic probe with permanent magnet and Hall sensor for identifying sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alphandéry, E. Iron oxide nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góral, D.; Marczuk, A.; Góral-Kowalczyk, M.; Koval, I.; Andrejko, D. Application of Iron Nanoparticle-Based Materials in the Food Industry. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colino, C.I.; Millán, C.G.; Lanao, J.M. Nanoparticles for signaling in biodiagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yang, T.; Liu, S.; Du, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Dong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, S.; Gong, Y.; et al. Insights into the Synthesis, types and application of iron Nanoparticles: The overlooked significance of environmental effects. Environ. Int. 2022, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Hofmann, H.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Petri-Fink, A. Assessing the in vitro and in vivo toxicity of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2323–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberdick, S.D.; Jordanova, K. V.; Lundstrom, J.T.; Parigi, G.; Poorman, M.E.; Zabow, G.; Keenan, K.E. Iron oxide nanoparticles as positive T1 contrast agents for low-field magnetic resonance imaging at 64 mT. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurlyandskaya, G. V.; Bhagat, S.M.; Safronov, A.P.; Beketov, I. V.; Larrañaga, A. Spherical magnetic nanoparticles fabricated by electric explosion of wire. AIP Adv. 2011, 1, 0–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.; Hong, H.; Im, P.W.; Kim, H.; Lee, C.; Jin, X.; Yan, B.; Lee, W.; Im, H.J.; Paek, S.H.; et al. Magnetic and near-infrared derived heating characteristics of dimercaptosuccinic acid coated uniform Fe@Fe3O4 core–shell nanoparticles. Nano Converg. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, V.; Induja, S.; Jaison, D.; Meher Abhinav, E.; Mothilal, M.; Gopalakrishnan, C. Tailoring the hyperthermia potential of magnetite nanoparticles via gadolinium ION substitution. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 31399–31406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rękorajska, A.; Cichowicz, G.; Cyranski, M.K.; Pękała, M.; Krysinski, P. Synthesis and characterization of Gd 3+ - and Tb 3+ -doped iron oxide nanoparticles for possible endoradiotherapy and hyperthermia. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 479, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morato, Y.L.; Marciello, M.; Chamizo, L.L.; Paredes, K.O.; Filice, M. Hybrid magnetic nanoparticles for multimodal molecular imaging of cancer. Magn. Nanoparticle-Based Hybrid Mater. Fundam. Appl. 2021, 343–386. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Sun, H.; Zhu, H.; Guo, H.; Sun, H. Synthesis of Gd-functionalized Fe3O4@polydopamine nanocomposites for: T 1/ T 2 dual-modal magnetic resonance imaging-guided photothermal therapy. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 7119–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; An, L.; Tian, Q.; Lin, J.; Yang, S. Gadolinium-labelled iron/iron oxide core/shell nanoparticles as T1-T2 contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26764–26770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhi, D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Nan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Qiu, B.; Wen, L.; Liang, G. Core/shell Fe3O4/Gd2O3 nanocubes as: T 1- T 2 dual modal MRI contrast agents. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 12826–12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, L.; Si, Y.; Li, Q.; Xiao, J.; Wang, B.; Liang, C.; Wu, Z.; Tian, G. Oxygen-enriched Fe3O4/Gd2O3 nanopeanuts for tumor-targeting MRI and ROS-triggered dual-modal cancer therapy through platinum (IV) prodrugs delivery. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, J.H.; Mcneil, S.E. IN. 2012.

- Sabik, A. Structural, Magnetic and Heating Efficiency of Ball Milled γ-Fe<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub>/Gd<sub>2</sub>O<sub>3</sub> Nanocomposite for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Adv. Mater. Phys. Chem. 2024, 14, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlyandskaya, G. V.; Burban, E.A.; Neznakhin, D.S.; Yushkov, A.A.; Larrañaga, A.; Melnikov, G.Y.; Svalov, A. V. Structure and Magnetic Properties of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Subjected to Mechanical Treatment. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2024, 125, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svalov, A. V.; Beketov, I. V.; Maksimov, A.D.; Medvedev, A.I.; Neznakhin, D.S.; Arkhipov, A. V.; Kurlyandskaya, G. V. Structure and Magnetic Properties of Gd2O3 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Spark Discharge. Phys. Met. Metallogr. 2023, 124, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, P.Z.; Škorvánek, I.; Kováč, J.; Geng, D.Y.; Zhao, X.G.; Zhang, Z.D. Structure and magnetic properties of Gd nanoparticles and carbon coated Gd/GdC2 nanocapsules. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 6779–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beketov, I. V.; Safronov, A.P.; Medvedev, A.I.; Alonso, J.; Kurlyandskaya, G. V.; Bhagat, S.M. Iron oxide nanoparticles fabricated by electric explosion of wire: Focus on magnetic nanofluids. AIP Adv. 2012, 2, 0–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, Y.A. Electric explosion of wires as a method for preparation of nanopowders. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2003, 5, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Safronov, A.P.; Mikhnevich, E.A.; Beketov, I. V.; Kurlyandskaya, G. V. Ferrogels based on entrapped metallic iron nanoparticles in a polyacrylamide network: Extended Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek consideration, interfacial interactions and magnetodeformation. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 3359–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beketov, I. V.; Safronov, A.P.; Bagazeev, A. V.; Larrañaga, A.; Kurlyandskaya, G. V.; Medvedev, A.I. In situ modification of Fe and Ni magnetic nanopowders produced by the electrical explosion of wire. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 586, S483–S488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, P. Determination of size and inner structure of colloidal particles by X-ray (Bestimmung der Grösse und der inneren Struktur von Kolloidteilchen mittels Röntgenstrahlen). Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Math. Klasse 1918.

- Bauer, K.; Garbe, D.; Surburg, H. Ullmann Polyvinyl Compounds, Others. … Encycl. Ind. Chem. 1988. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, A.; Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Helsen, M.; Garcia-Sanchez, F.; Van Waeyenberge, B. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Adv. 2014, 4, 0–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Mulkers, J.; De Clercq, J.; Milošević, M. V.; Van Waeyenberge, B. Fast micromagnetic simulations on GPU - Recent advances made with mumax3. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 2018, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’min, M.D.; Skokov, K.P.; Diop, L.V.B.; Radulov, I.A.; Gutfleisch, O. Exchange stiffness of ferromagnets. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2020, 135, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo, G.S.; Hong, Y.K.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, W.; Choi, B.C. Definition of magnetic exchange length. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2013, 49, 4937–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’min, M.D. Shape of temperature dependence of spontaneous magnetization of ferromagnets: Quantitative analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coey, M.; Parkin, S.S.P. Handbook of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials; 2020; ISBN 9783030632083.

- Graham Jr., C.D. Magnetocrystalline Anisotropy Constants of Iron at Room Temperature and Below. Phys. Rev. 2000, 112, 4–7.

- Safronov, A.P.; Beketov, I. V.; Komogortsev, S. V.; Kurlyandskaya, G. V.; Medvedev, A.I.; Leiman, D. V.; Larrañaga, A.; Bhagat, S.M. Spherical magnetic nanoparticles fabricated by laser target evaporation. AIP Adv. 2013, 3, 0–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvell, J.; Ayieta, E.; Gavrin, A.; Cheng, R.; Shah, V.R.; Sokol, P. Magnetic properties of iron nanoparticle. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, S.; Hadjipanayis, G.C.; Dale, B.; Sorensen, C.M.; Klabunde, K.J.; Papaefthymiou, V.; Kostikas, A. Magnetic properties of ultrafine iron particles. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 9778–9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdt, J.; F. Goya, G.; Pilar Calatayud, M.; B. Herenu, C.; C. Reggiani, P.; G. Goya, R. Magnetic Field-Assisted Gene Delivery: Achievements and Therapeutic Potential. Curr. Gene Ther. 2012, 12, 116–126. [CrossRef]

- Dimian, M.; Lefter, C. Analysis of magnetization switching via vortex formation in soft magnetic nanoparticles. Adv. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2013, 13, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrmann, A.; Blachowicz, T. Vortex and double-vortex nucleation during magnetization reversal in Fe nanodots of different dimensions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 475, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betto, D.; Coey, J.M.D. Vortex state in ferromagnetic nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 2012–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, L.G.; Yanes, R.; Berkov, D.; Erokhin, S.; Bersweiler, M.; Honecker, D.; Bender, P.; Michels, A. Toward Understanding Complex Spin Textures in Nanoparticles by Magnetic Neutron Scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 117201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omelyanchik, A.; Varvaro, G.; Gorshenkov, M.; Medvedev, A.; Bagazeev, A.; Beketov, I.; Rodionova, V. High-quality α-Fe nanoparticles synthesized by the electric explosion of wires. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2019, 484, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komogortsev, S. V.; Stolyar, S. V.; Mokhov, A.A.; Fel’k, V.A.; Velikanov, D.A.; Iskhakov, R.S. Effect of the Core–Shell Exchange Coupling on the Approach to Magnetic Saturation in a Ferrimagnetic Nanoparticle. Magnetochemistry 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedanta, S.; Kleemann, W. Supermagnetism. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 2009, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfarth, E.P. Magnetic properties of single domain ferromagnetic particles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1983, 39, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Batch | ms (H = 1.8 T), Am2/kg | mr, Am2/kg | Hc, mT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe (293 K) | 190 | 11 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).