Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. The Fabrication of the PDMS Microfluidic Device

2.3. Characterization of Hydrogel Microspheres

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Formation of Hydrogel Microsphere

3.2. Separation of Hydrogel Microsphere

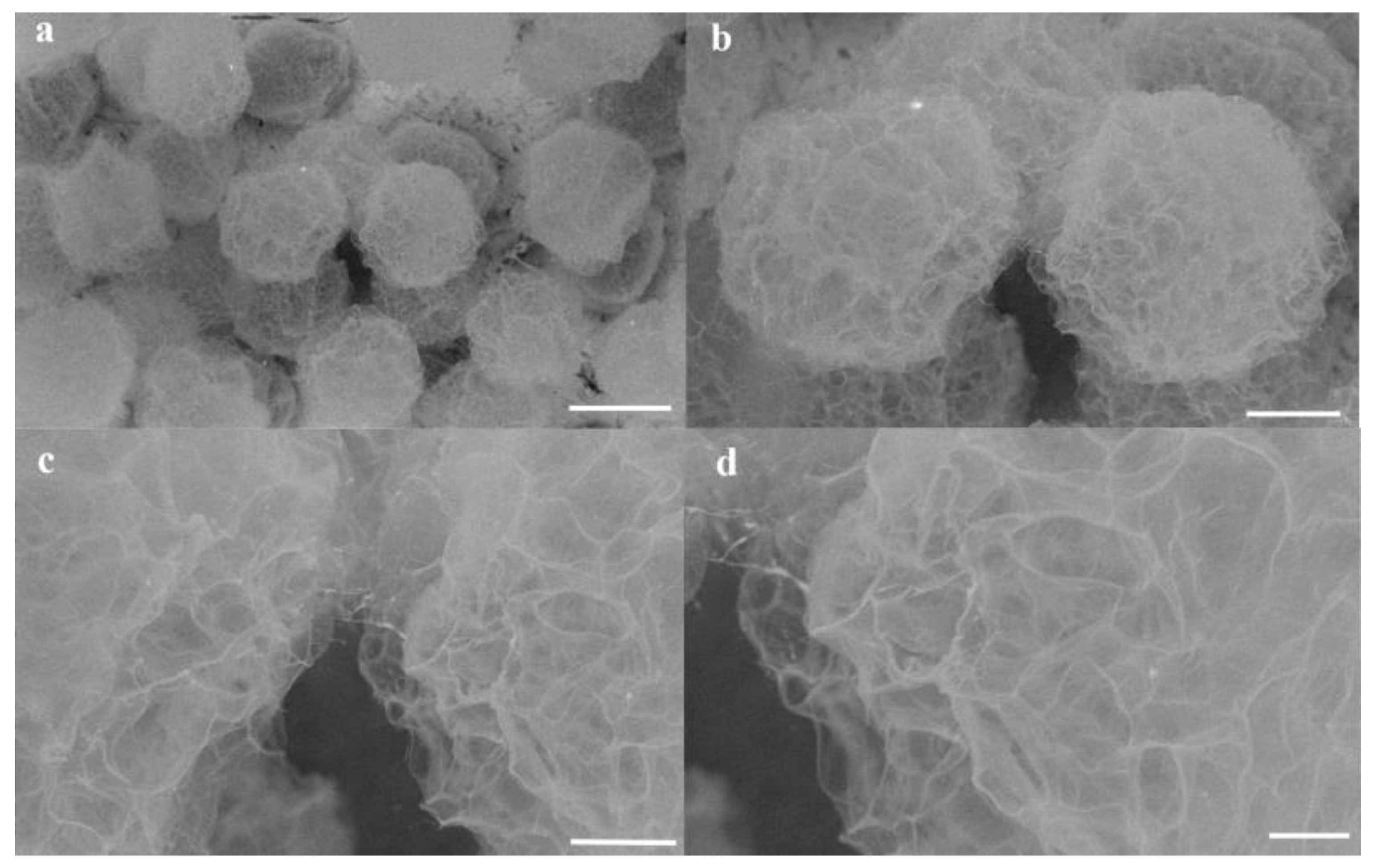

3.3. Surface Morphologies and Microstructures of Hydrogel Microsphere

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mou, C.-L.; Deng, Q.-Z.; Hu, J.-X.; Wang, L.-Y.; Deng, H.-B.; Xiao, G.; Zhan, Y. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2020, 569, 307–319. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Jing, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Cui, J.; Fu, Z.; Li, D.; Zhao, C.; Liaqat, U.; Lin, K. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 332. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, I.M.; Barreiro, M.F.; Coelho, M.; Rodrigues, A.E. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 245, 191–200. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, Y.; Onuki, M.; Takeuchi, S. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2017, 6(13). [CrossRef]

- Somo, S.I.; Langert, K.; Yang, C.-Y.; Vaicik, M.K.; Ibarra, V.; Appel, A.A.; Akar, B.; Cheng, M.-H.; Brey, E.M. Acta Biomaterialia 2018, 65, 53–65. [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-H.; Takeuchi, S. Advanced Materials 2007, 19, 2696-+. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.-H.; Jung, J.-H.; Rhee, Y.W.; Kim, D.-P.; Shim, S.-E.; Lee, C.-S. Biomedical Microdevices 2007, 9, 855–862. [CrossRef]

- Utech, S.; Prodanovic, R.; Mao, A.S.; Ostafe, R.; Mooney, D.J.; Weitz, D.A. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2015, 4, 1628–1633. [CrossRef]

- Rojek, K.O.; Cwiklinska, M.; Kuczak, J.; Guzowski, J. Chemical Reviews 2022, 122, 16839–16909. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Utech, S.; Chen, D.; Prodanovic, R.; Lin, J.-M.; Weitz, D.A. Lab on a Chip 2016, 16, 1346–1349. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Khan, M.; Mao, S.; Manibalan, K.; Li, N.; Lin, J.-M.; Lin, L. Analytical Chemistry 2019, 91, 12283–12289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, L.M.C.; Duchi, S.; Onofrillo, C.; O’Connell, C.D.; Di Bella, C.; Moulton, S.E. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 587, 240–251. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, L.; Li, W.; Liu, Q. Analytical Methods 2022, 14(12), 1181–1186. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, H.; Chen, S.; Xu, N.; Lin, J.-M. Analytical Chemistry 2023, 95(2), 1402–1408.

- Li, B.; Zhang, L.; Yin, Y.; Chen, A.; Seo, B.R.; Lou, J.; Mooney, D.J.; Weitz, D.A. Matter 2024, 7(10).

- Qiao, S.; Chen, W.; Zheng, X.; Ma, L. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 254.

- Jiang, S.; Jing, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Cui, J.; Fu, Z.; Li, D.; Zhao, C.; Liaqat, U.; Lin, K. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 332. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Lang, Y.; He, J.; Cui, J.; Liu, X.; Yuan, H.; Li, L.; Zhou, M.; Wang, S. Biomaterials 2025, 317. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shahar, T.; Cohen, S. Rsc Advances 2024, 14(44), 32021–32028. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, G. Langmuir 2025, 41(13), 8985–8997. [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Galeai, F. M.; Nguyen, N.-K.; Roshan, U.; Yadav, A.S.; Sreejith, K.R.; Nguyen, N.-T. Chemnanomat 2025, 11(3).

- Marburger, J.; Vladisavljevic, G. T.; Leister, N. Colloids and Surfaces a-Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2025, 714.

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J. Micromachines 2017, 8(10).

- Jeong, Y.; Irudayaraj, J. Chemical Communications 2022, 58, 8584–8587. [CrossRef]

| Master | Surfactant | Demulsification | Ref. |

| Glass tube | F-127 | Isopropyl alcohol | 1 |

| SU-8 | Span 80 | PFO | 2,16 |

| SU-8 | Lecithin | Hexane/Hexadecane | 6 |

| SU-8 | PFPE-PEG | PFO | 8,11,14 |

| SU-8 | PicosurfTM | 1H,1H-Perfluorooctan-1-ol | 12 |

| SU-8 | neat 008-uorosurfactant | PFO | 13 |

| SU-8 | Krytox–PEG–Krytox | PFO | 15 |

| Paper | Without addition | Without addition | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).