2.2.1. Problems of Numerical Solution of Boundary Value Problem

In order to clarify the problems of numerical solution of the boundary value problem, we will move to a dimensionless form using characteristic quantities.

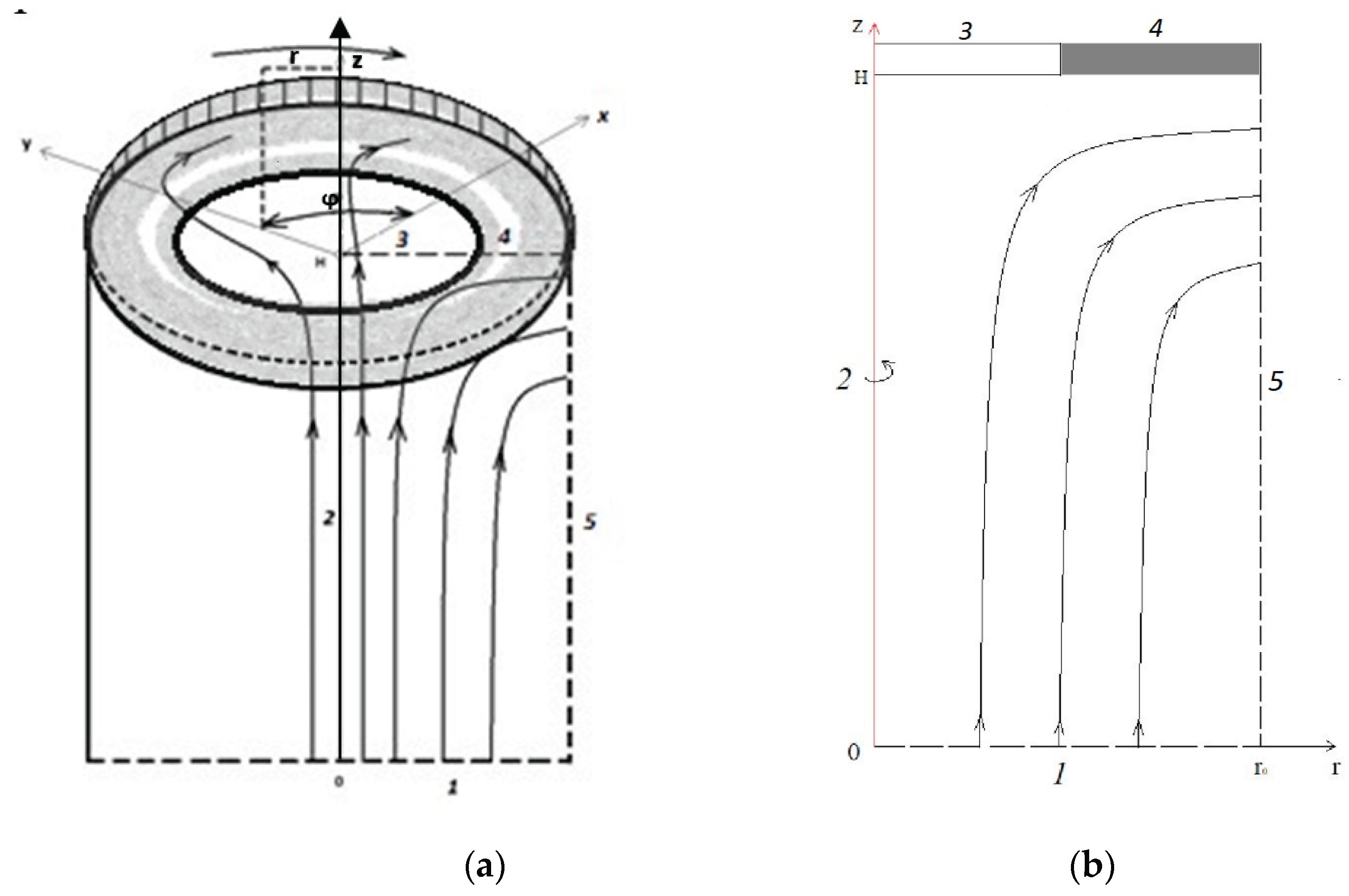

The problem has two characteristic quantities - the cell height and is the outer radius of the annular membrane. Since in practice , where proportionality coefficient , therefore they have the same order, and is taken as a characteristic quantity, since it is convenient to express the characteristic speed through it. As the characteristic velocity , we will use the azimuthal component of the velocity V0 = ω0r0.

Next, we will make the transition in the equations from dimensional quantities to dimensionless ones. Then we will get:

where

Let us evaluate and clarify the meaning of dimensionless parameters. The system of Nernst – Planck – Poisson and Navier – Stokes equations in a cylindrical coordinate system obtained in the process of non-dimensionalization includes 4 dimensionless parameters:

1. The Peclet number shows the ratio of the coefficients of kinematic viscosity and diffusion. With a characteristic channel height and an outer radius of the membrane disk of 1 mm, we obtain an estimate of the Peclet number (

Table 1):

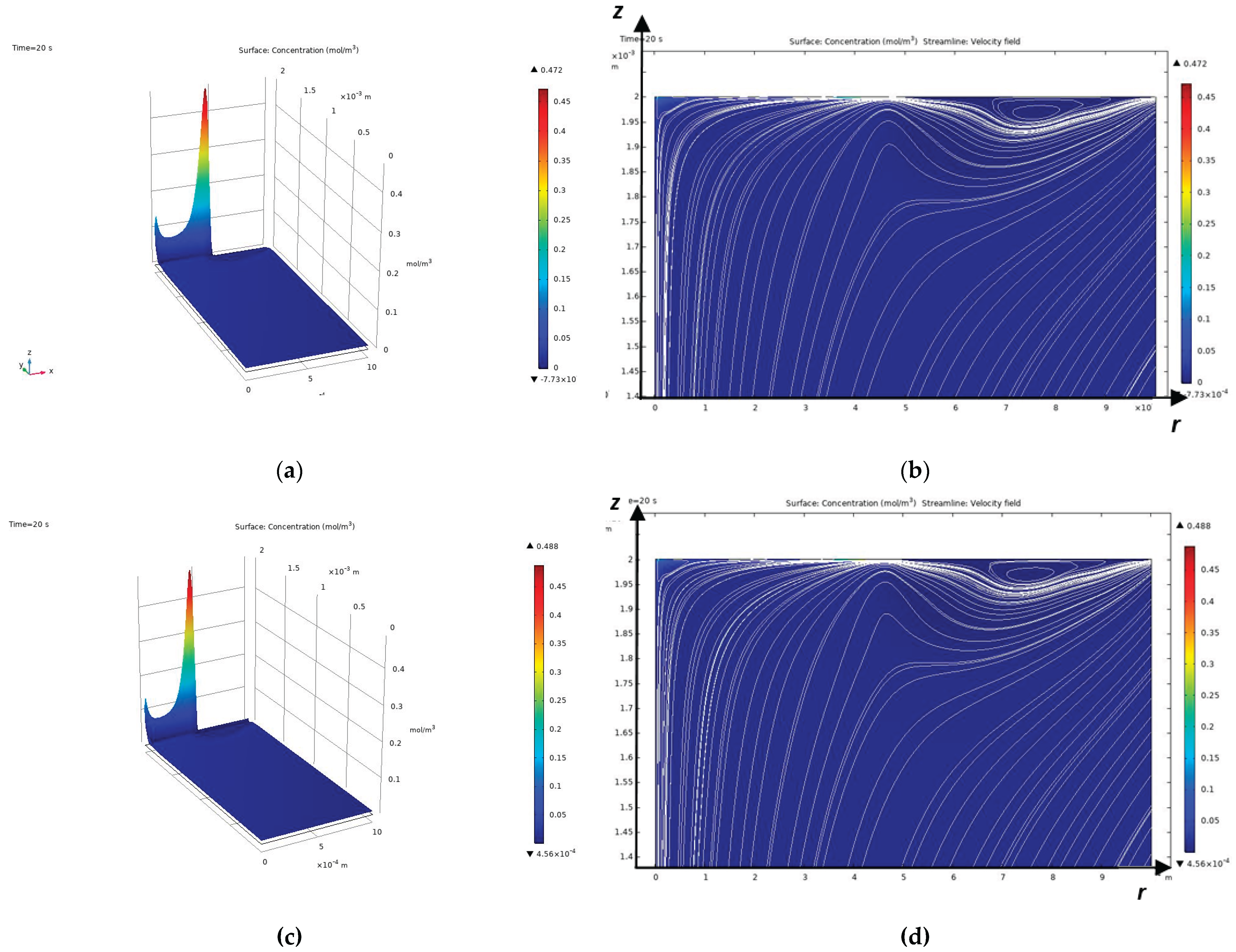

The Peclet number can be considered a large parameter, that is, in this problem there will be a developed diffusion layer, and the convective transfer of salt ions prevails over the diffusion transfer.

2. Dimensionless number

:

From this formula it follows that when changing

from 0.01 mol/m

3 to 100 mol/m

3 the parameter

changes from

to

. Therefore,

it can be considered a small parameter, which has a meaning in the form of the ratio of the square of the thickness of the region of equilibrium space charge to the square of the intermembrane distance [

16]:

, where

– Debye length. Thus, the space charge region (SCR) located as part of the double electric boundary layer near the CEM is of the order of

. It is easy to show that in this region the gradients of concentrations and electric field strengths are of the order of

, as a result of which the boundary value problem is related to stiff problems and therefore serious problems arise in the numerical solution.

3. Reynolds number Re, which is the ratio of the inertial force to the viscous friction force .

Table 2 presents the results of estimating the Reynolds number for the desalination chamber. If we take the outer radius of the membrane disk

of about 1 mm, and consider a liquid with the same viscosity as water

m

2/s, then

.

From this table it is clear that the forces of inertia and viscous friction are approximately the same, therefore it is necessary to use the Navier-Stokes equation without any simplifications, in addition, from the adhesion conditions it follows that a hydrodynamic layer (friction layer) arises, but from the value of the Reynolds number it follows that it is not developed.

4. The dimensionless parameter

is the ratio of electrical force to inertial force. Let's calculate it for a membrane radius of

m (

Table 3):

From

Table 3 and the formula it is evident that with increasing speed

the value

quickly decreases, and with increasing concentration it increases; in the Navier – Stokes equation this value occurs in the complex

, hence it is evident that electroconvection practically does not depend on the initial concentration, but strongly depends on the angular velocity of rotation, namely: with increasing angular velocity electroconvection quickly dies out.

The presence of a small parameter at the derivative in the Poisson equation shows that the problem belongs to the type of singularly perturbed problems for a quasilinear system of partial differential equations.

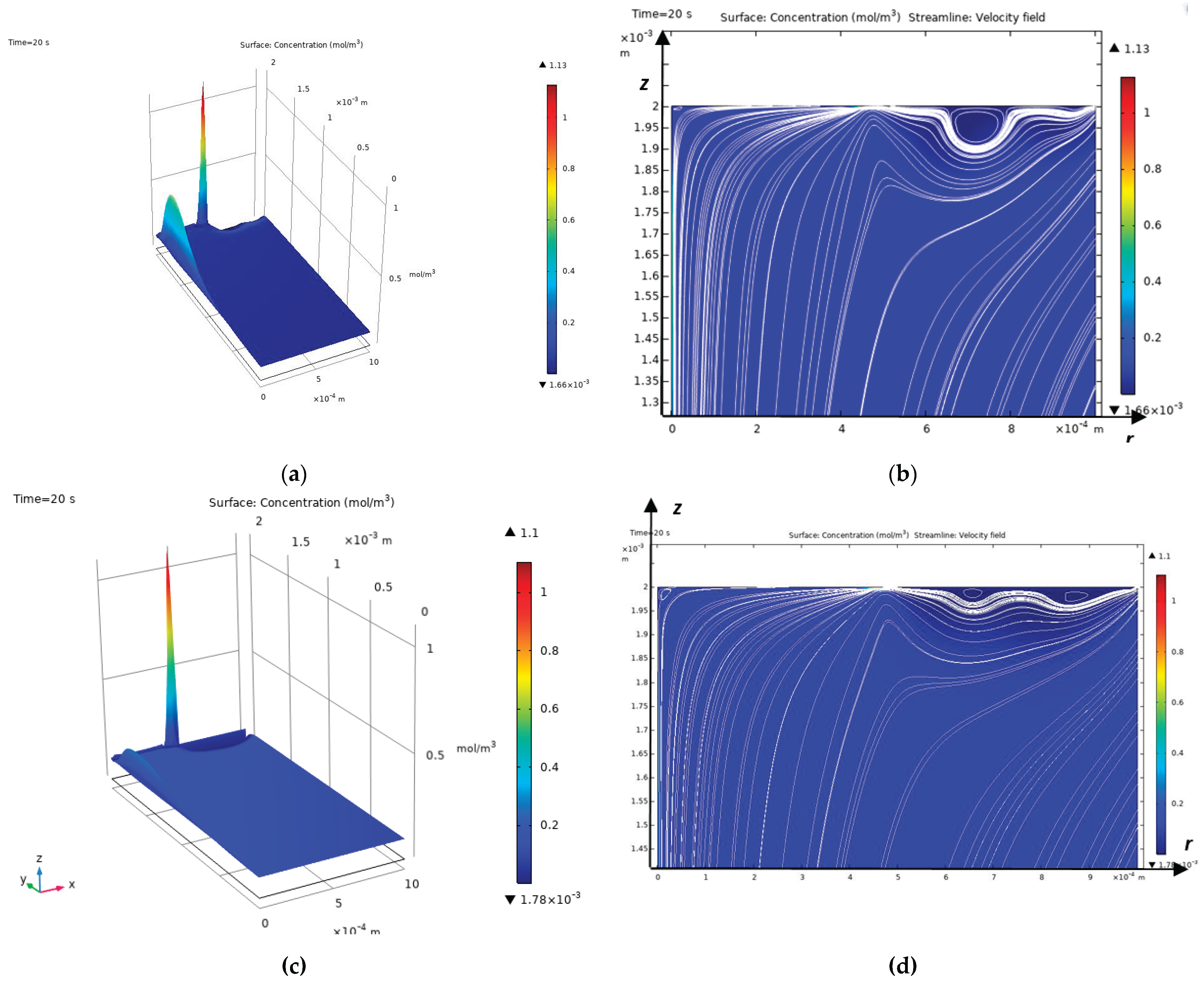

2.2.2. The Structure of the Diffusion Layer Near the CEM and the General Idea of the Numerical-analytical Solution

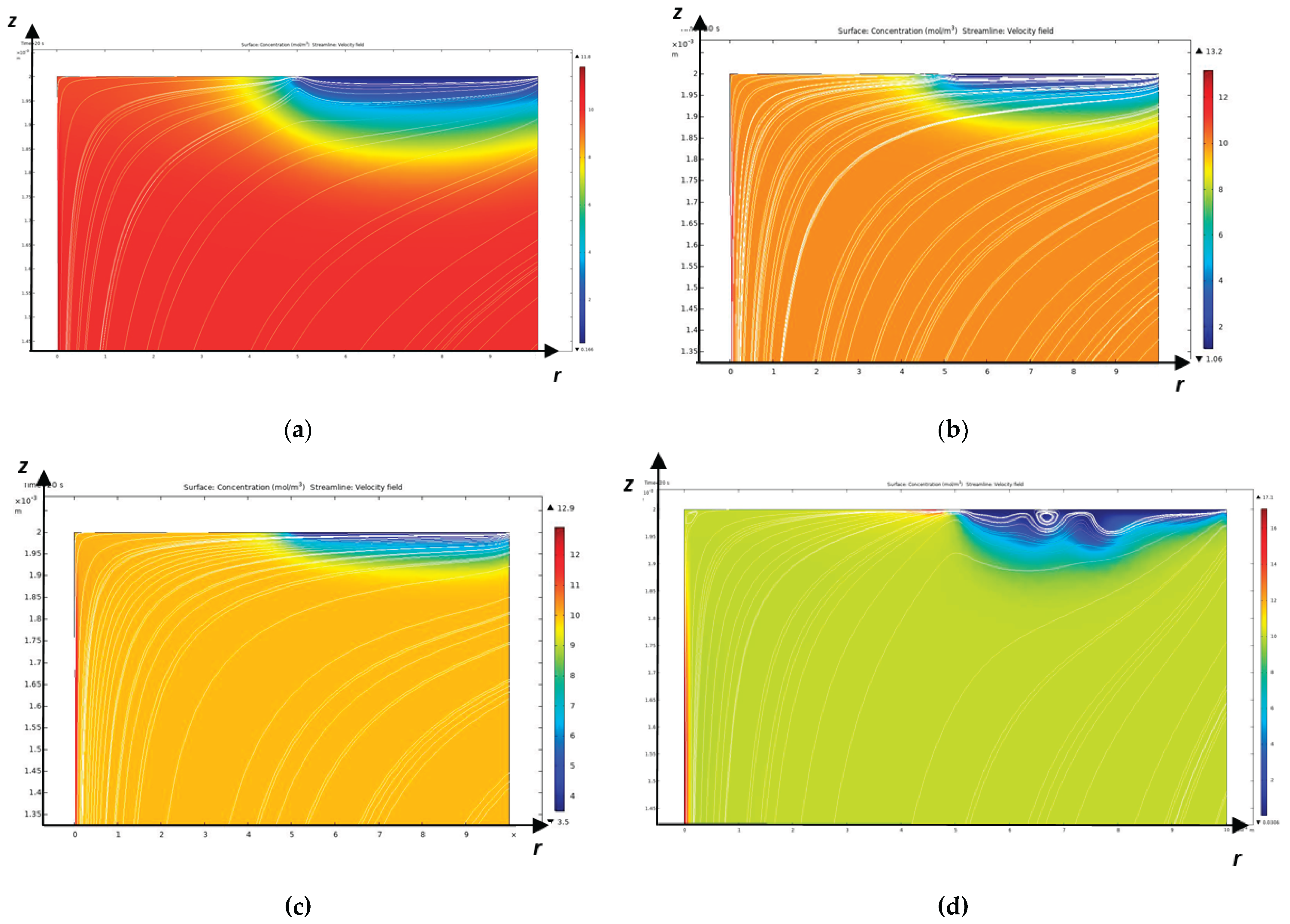

As mentioned above, the Peclet number shows that a diffusion layer arises near the CEM, which in turn consists of an electroneutrality region and a space charge region directly adjacent to the membrane [

17]. The structure of the space charge region is determined by the current density, which in turn is determined by the potential jump. At currents below a certain critical value, called the limiting value [

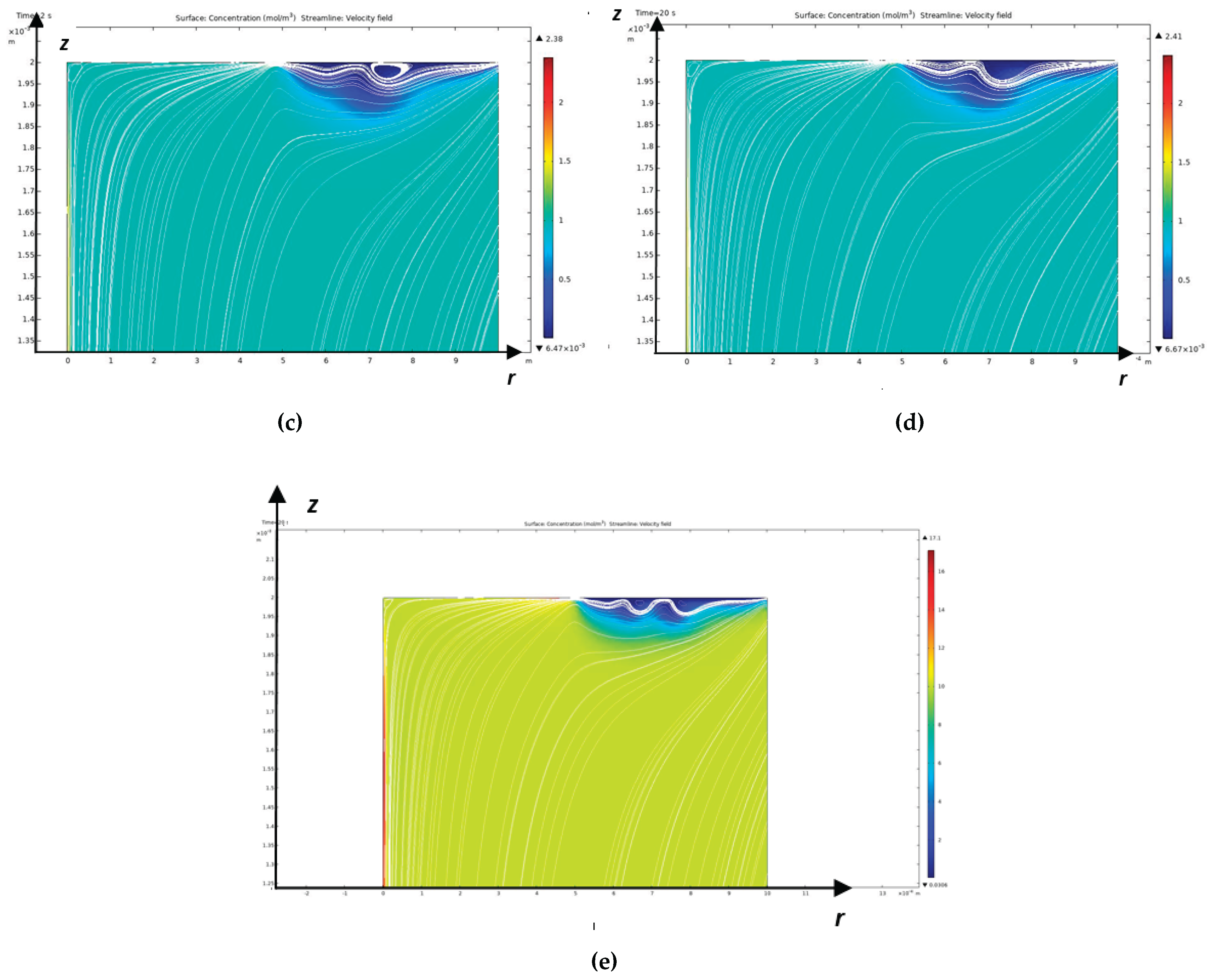

17], the diffusion layer consists of an electroneutrality region and a quasi-equilibrium space charge region (quasi-equilibrium SCR), which is several orders of magnitude smaller than the electroneutrality region. At overlimiting currents, in addition to the quasi-equilibrium space charge region, an extended region of the spatial layer arises, which has a size significantly smaller, but already comparable with the electroneutrality region [

9]. In the extended SCR, electromigration prevails over diffusion, and in the electroneutrality region, the migration and diffusion flows are equal. In a quasi-equilibrium SCR, the migration flow is equal to the diffusion flow in the first approximation, but they are opposite in direction, which leads to the current becoming zero in the first approximation. In the quasi-equilibrium region of the space charge, the concentrations and electric field strength increase exponentially and therefore their gradients have very large values compared to the values in the region of electroneutrality and the extended region of the space charge. Thus, the boundary value problems of membrane electrochemistry that take into account the quasi-equilibrium region of the space charge are hard problems and are difficult to solve numerically, require an exponential change in the grid step in the quasi-equilibrium region of the space charge and, accordingly, very small time steps, which leads to the accumulation of errors [

18]. At the same time, a numerical study of the properties of a quasi-equilibrium SCR made it possible to establish its main properties:

1. quasi-equilibrium SCR is formed almost instantly, in about 10-5 seconds;

2. the thickness of quasi-equilibrium SCR does not depend on the radius (r) of the membrane disk, except for the vicinity of ;

3) quasi-equilibrium SCR is also quasi-stationary, i.e. it is practically independent of time;

4) the axial and radial velocities in quasi-equilibrium SCR are close to zero, and the azimuthal can be considered practically constant and equal to , i.e. the electrolyte solution near the membrane in quasi-equilibrium SCR rotates as a whole.

In this connection, a natural idea arises to use an analytical solution in the quasi-equilibrium region in combination with a numerical solution in the remaining region. To implement this idea, three problems must be solved:

1. find an analytical solution in the quasi-equilibrium SCR;

2. determine the boundary conditions on the left boundary of the quasi-equilibrium SCR for the numerical solution;

3. splice the analytical and numerical solutions, i.e. find the constants included in the analytical solution and determine the boundary between the analytical and numerical solutions.

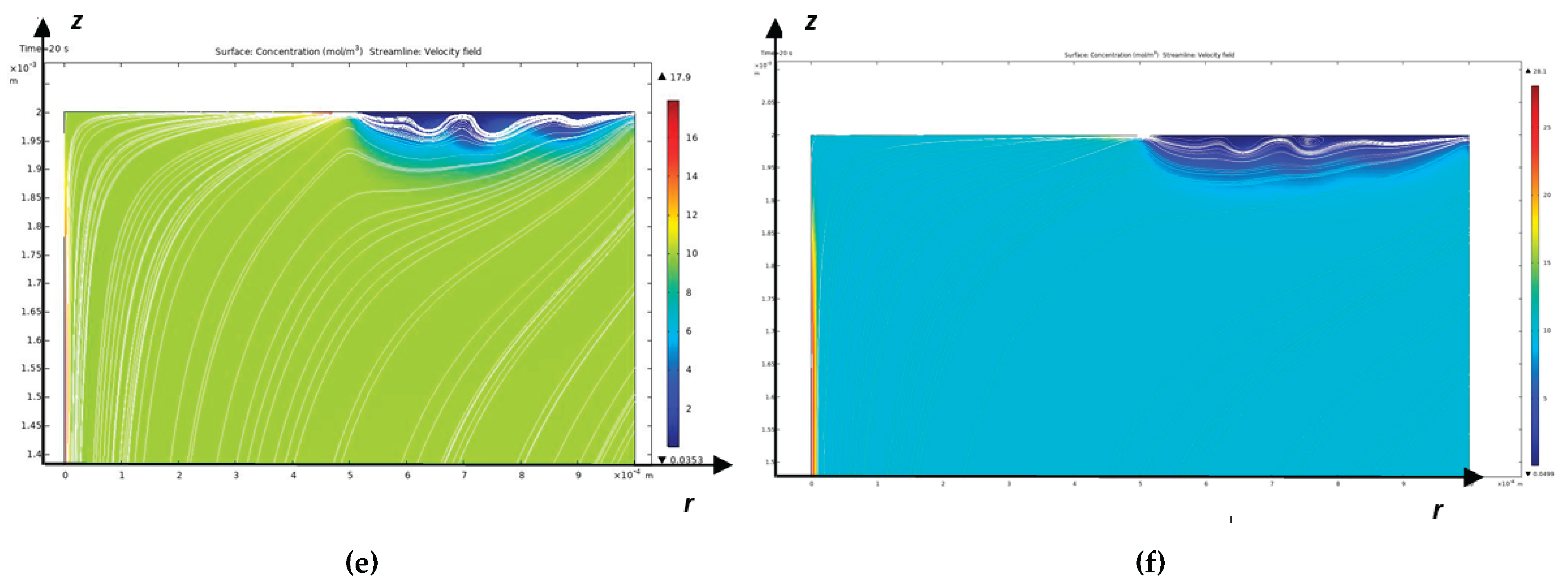

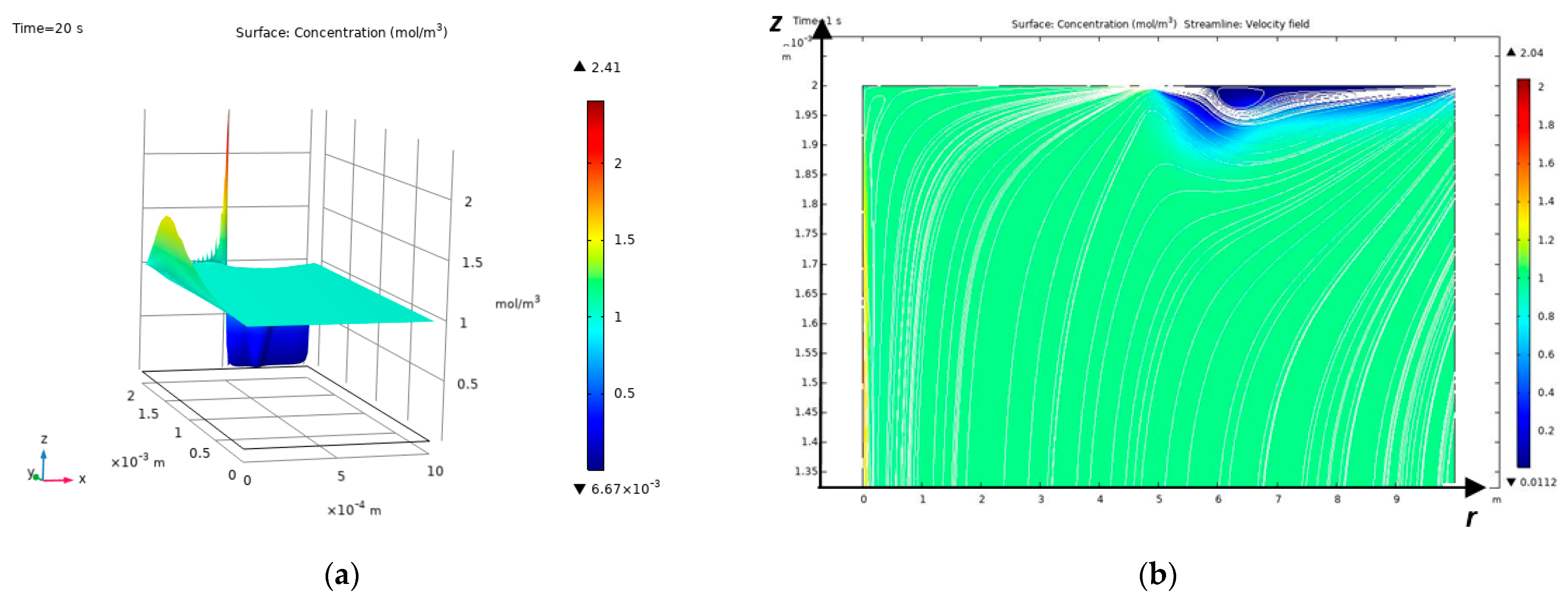

To solve the last two problems, note that at sub-limit currents, the cation concentration decreases in the electroneutrality region and increases in the quasi-equilibrium SCR, and at overlimit currents, the concentration also decreases in almost the entire extended SCR, and the region of increasing cations (RICC) includes a small part of the extended SCR and the entire quasi-equilibrium SCR. Thus, the region of increasing cations (RICC) at sublimiting currents coincides with the quasi-equilibrium SCR, and at overlimiting currents it almost coincides with the quasi-equilibrium SCR, since it also includes a small part of the extended SCR. In addition, RICC has all the above-listed properties of the quasi-equilibrium SCR. Therefore, in what follows, we will use RICC instead of the extended SCR. The boundary between RICC and the rest of the solution region is the points at which the cation concentration has a local minimum.

2.2.3. Analytical Solution of Boundary Value Problem in RICC

The analytical solution in RICC depends on the magnitude of the potential jump, namely, sublimit or overlimit. In the sublimit regime, RICC coincides with the quasi-equilibrium SCR, and in the overlimit regime, these regions are very close. As was noted above, the RICC thickness does not depend on the radial coordinate

r, the radial (

) and axial (

) velocities are close to zero, and the azimuthal (

) velocity is almost constant in RICC. Therefore, only the third component remains in equation (1):

In addition, in RICC all unknown functions are practically independent of time t, therefore the left-hand side of equation (2) is equal to zero, and in the right-hand side, due to independence from r, the derivative of the flow with respect to z is equal to zero, in equations (3) and (4) only components dependent on z will also remain and, thus, to find unknown functions in RICC, we obtain a system of equations:

Thus, the system of equations (5-8), for example, for a 1:1 solution of electrolyte with ideally selective CEM takes the form (the index “u” is omitted for simplicity):

where

– electric field strength, and

– is its potential;

,

– respectively, the desired concentrations of cations and anions,

– current,

– small parameter.

As boundary conditions in dimensionless form for

, the conditions of merging with the numerical solution are set, and for

:

The system of equations (9-11) represents a singularly perturbed boundary value problem.

1. Solution in the pre-limit case

Let us make the substitution

,

,

,

, then for small

, in the initial approximation, we obtain the classical system of Boltzmann-Debye equations, which describes the quasi-equilibrium SCR:

with the corresponding boundary conditions (12-14). Therefore, in the pre-limit regime, RICC coincides with the quasi-equilibrium SCR.

The boundary value problem has an approximate analytical solution:

where

, – some positive number that is determined from the condition

equivalent to the condition

.

– the value of the numerical solution at the point must be finite and, accordingly, (the value of the analytical solution in RICC) must also be finite. This condition is satisfied if , then we obtain , for , if we take . The equality is satisfied using a higher approximation.

The points obtained from the numerical solution by the independent finite element method mm and the analytical solution in RICC mm coincide with an accuracy of 1.1%.

Concentrations are merged by virtue of the choice and formulas (19-20).

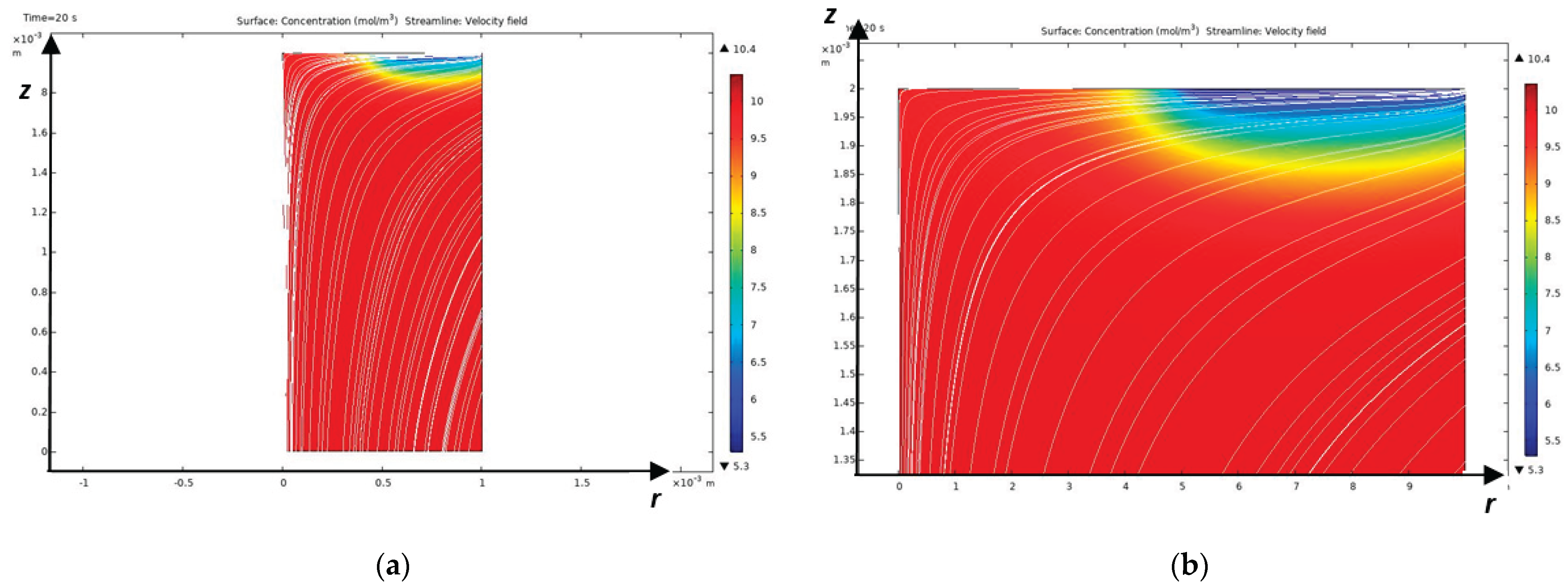

2. Solution in the overlimit case

The appearance of an extended SCR in the overlimit mode, where ion concentrations are low and the electric field strength tends to infinity as, requires a different procedure.

At overlimit currents, there are no anions in the region , i.e. , .

Therefore, the system of equations (9)-(11) takes the form:

This system has an approximate analytical solution:

where

is the integration constant.

3. Splicing solutions and determining constants

Let's put it this way .

For the splicing procedure

:

we use

from the analytical solution in the interval

, and for the calculation of

we use the function

, which is a continuation into interval

the solution in the extended SCR. Therefore:

Thus .

Let

, then:

where for the calculation

we use the function

solution in RICC (part of the extended SCR), and in

we use the solution in the interval

, extended to the interval

.

Where do we get: and .

To find b we use the condition , from which .