Submitted:

22 May 2025

Posted:

23 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Digital Payments and Growth

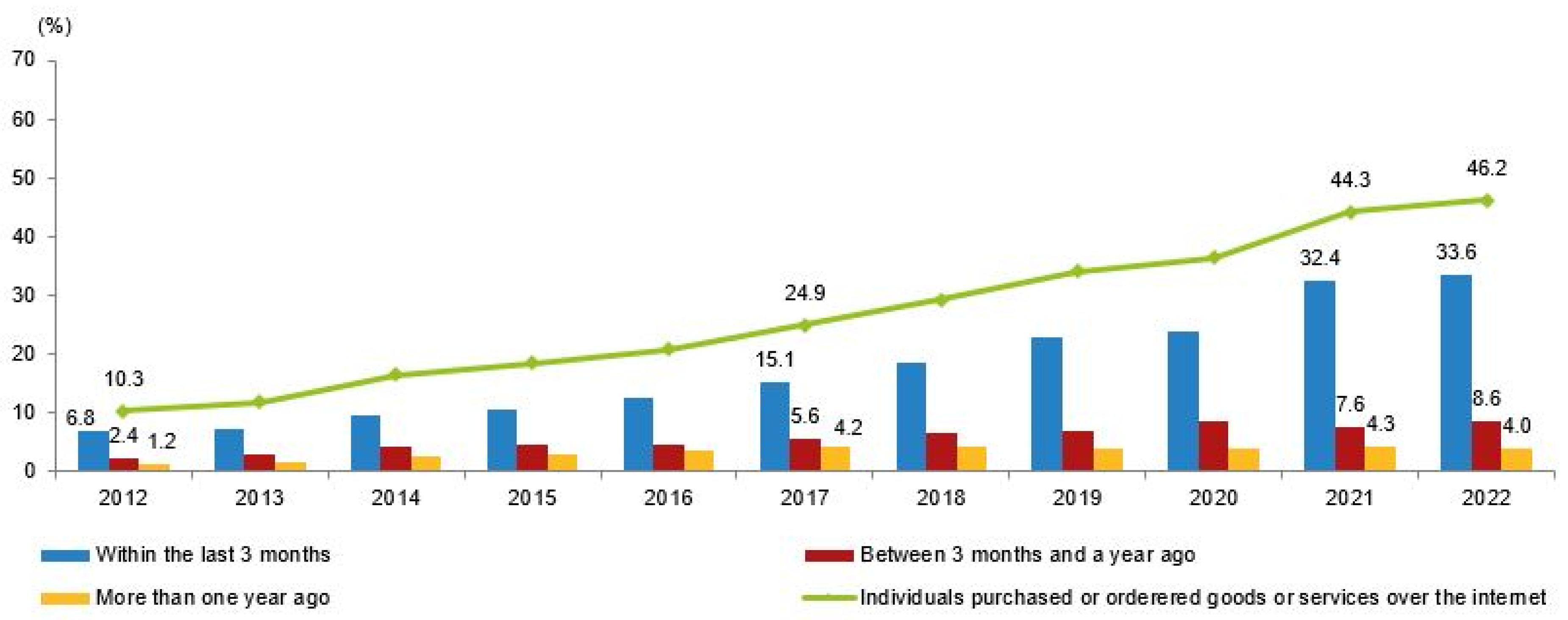

2.2. Digital Technologies in Turkey

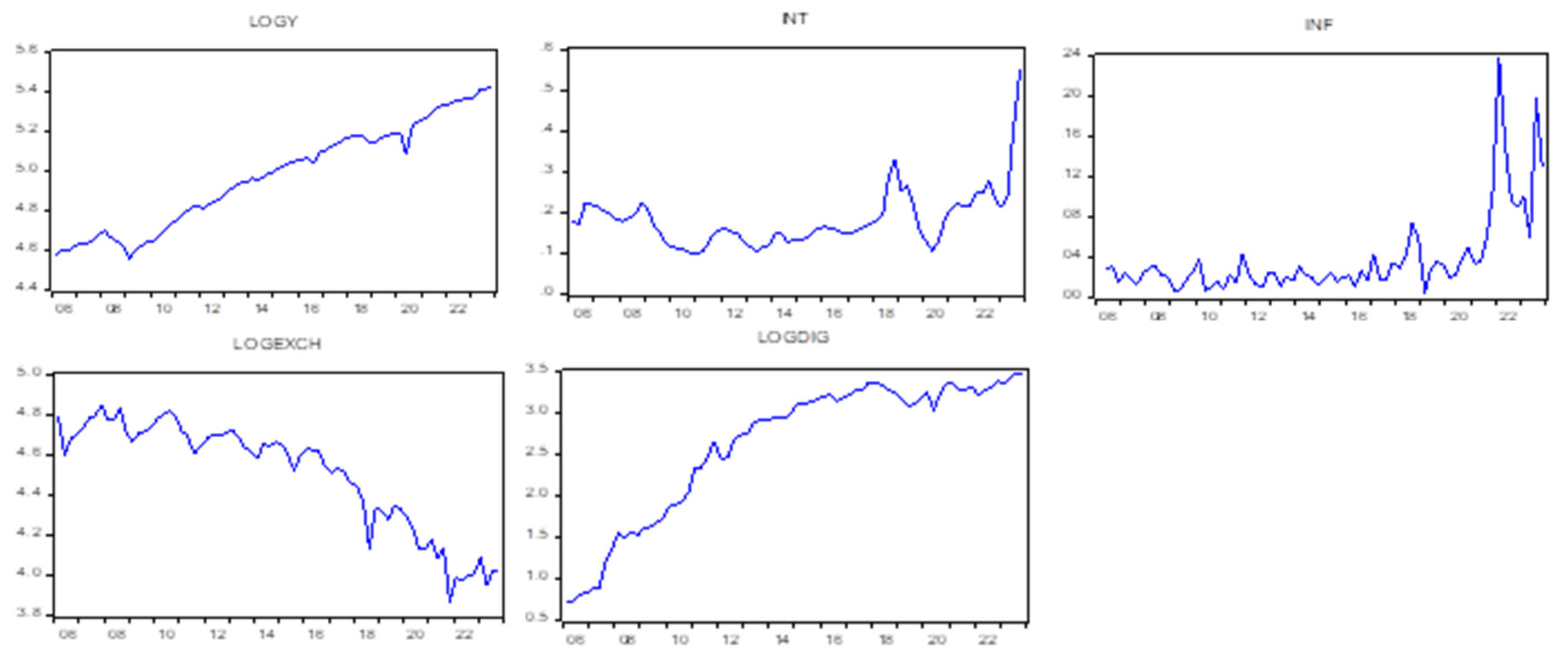

3. Data and Methodology

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Cointegration

- Restricted intercept with no time trend (Case 2): It assumes no linear trends in the data and a zero mean for the first-differenced series.

- Unrestricted intercept with no time trend (Case 3): It allows for linear trends in the data, and non-zero intercept in the cointegrating relations.

- LM tests for autocorrelation up to 1st, 4th, and 8th lags

- The Doornik and Hansen multivariate test for normality

- A White-type test for heteroskedasticity

| logy | = | - 0.422 int | - 3.143 inf | + 0.828 logexch | + 0.227 logdig | (3) | |

| (0.483) | (0.905) | (0.155) | (0.035) |

- A 1% increase in interest rates is associated with a 0.4% decrease in real GDP. This aligns with conventional monetary theory—in periods when interest rates are higher, economic activity may slow down due to a rise in borrowing costs. However, the insignificance of the coefficient suggests that interest rates may not be the primary driver of GDP growth (or vice versa) in the long term.

- A 1% increase in inflation is associated with a 3.1% decrease in real GDP. High inflation and low economic growth may coincide for several reasons. For example, low growth may lead to higher inflation through supply problems or inflation may reduce growth through lower purchasing power, increased uncertainty, and potential distortions in savings and investment behavior.

- A 1% increase in real effective exchange rates (appreciation of the domestic currency) is associated with a 0.8% increase in real GDP, i.e., a stronger domestic currency goes hand in hand with higher growth in Turkey. This result is not surprising since Turkey is a chronic current account deficit country, and the economy heavily relies on the inflow of foreign capital for investment and economic growth. When capital inflows intensify, economic growth accelerates together with stronger domestic currency.

- A 1% increase in the volume of digital payments is associated with a 0.2% increase in real GDP. This highlights the positive correlation between digitalization and economic growth.

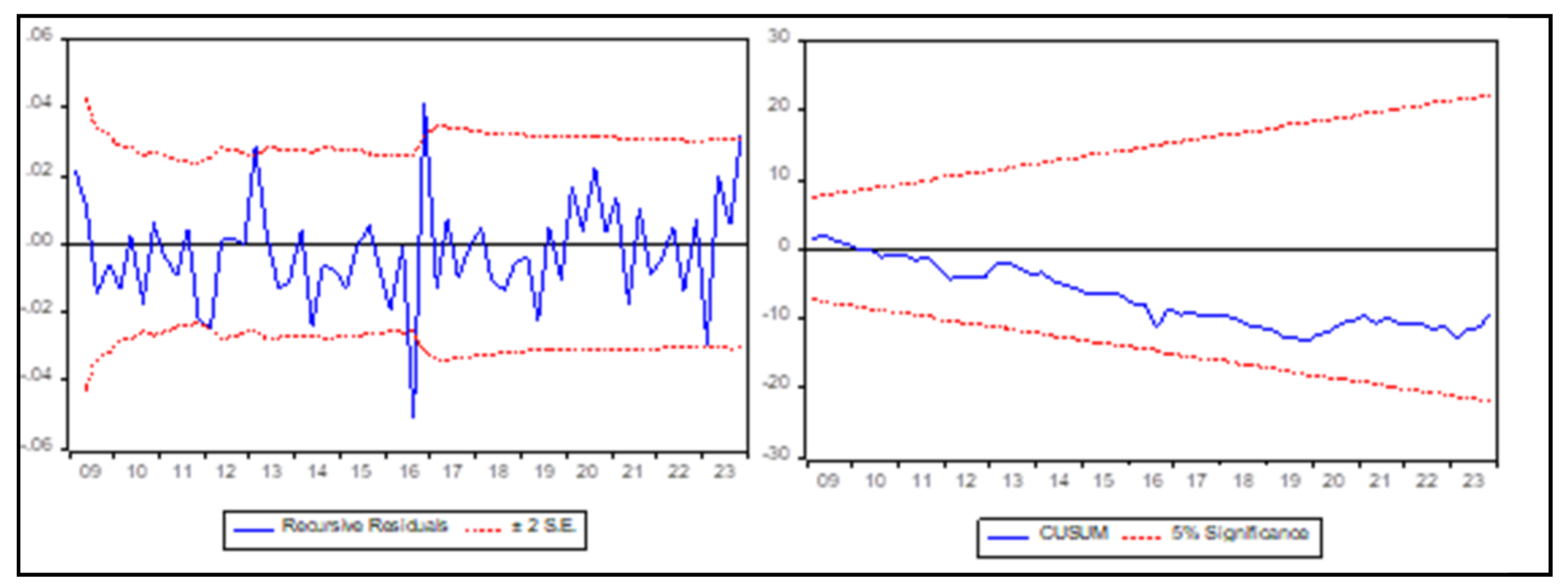

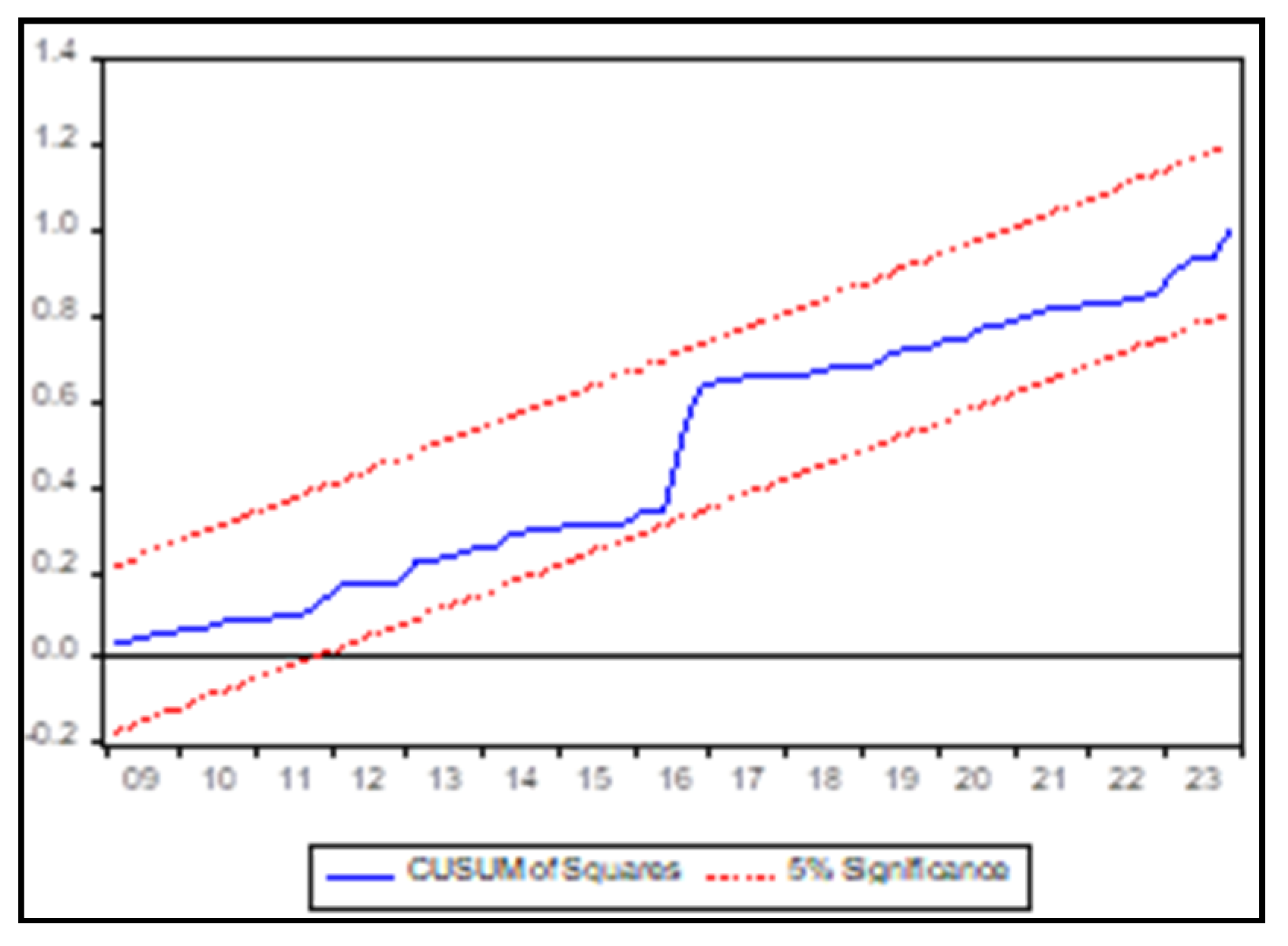

4.2. Estimation of Vector Error Correction Model (VECM)

- : Quarterly percentage change in the federal funds rate

- : Quarterly change in the log of real GDP of the Euro area

- and : Dummy variables capturing the impact of two non-economic shocks. One is the failed coup attempt in Turkey in July 2016 and the other is the Covid19 epidemic in March 2020. is equal to one in 2016Q3, minus one in 2016Q4, and zero otherwise. is equal to one in 2020Q2, minus one in 2020Q3, and zero otherwise.

- Digital banking has a positive and significant coefficient, supporting the view that financial digitalization facilitates economic growth. A 1% increase in the quarterly growth of digital banking usage raises the quarterly growth rate of the GDP by 0.05 percentage points. The short-term impact of interest rates is significant but negative reflecting the contractionary impact of monetary tightening. Exchange rate (appreciation of the domestic currency) has a significant and positive effect on economic growth as stronger currency cheapens imports, reduces costs for businesses and consumers, and lowers the external debt burden. Out of two exogenous factors, the change in federal funds rate is not significant, possibly due to the presence of exchange rates in the model that captures the influence of global financial conditions. The growth rate of the Euro area, on the other hand, has a significant and positive coefficient showing the importance of global demand conditions. Finally, the dummy variable, , is significant and negative reflecting the adverse effect of the failed coup attempt that is not captured by regular variables, whereas , is negative but not significant, which suggests that its impact on GDP is already captured by other regressors. The model explains over 81% of the variation in .

- In the (quarterly change in the inflation rate) equation, the coefficients of most variables have expected signs, but only the growth rate, the change in exchange rates, and the change in the federal funds rate are statistically significant. The positive link between growth and inflation in Turkey reflects the boom-and-bust cycles experienced since 1980s. The negative effect of tightening in global financial conditions and the positive effect of currency depreciation on inflation are common themes in emerging market economies. The explanatory power of the model is modest: R2 is 0.520.

- In the (quarterly change in the growth rate of digital payments) equation, the coefficients of the error correction term and the growth rate are significant reflecting the positive link between the growth rate and digital payments. The explanatory power of the model is also modest: R2 is 0.349.

4.3. Generalized Impulse Response Functions and Variance Decomposition Analysis

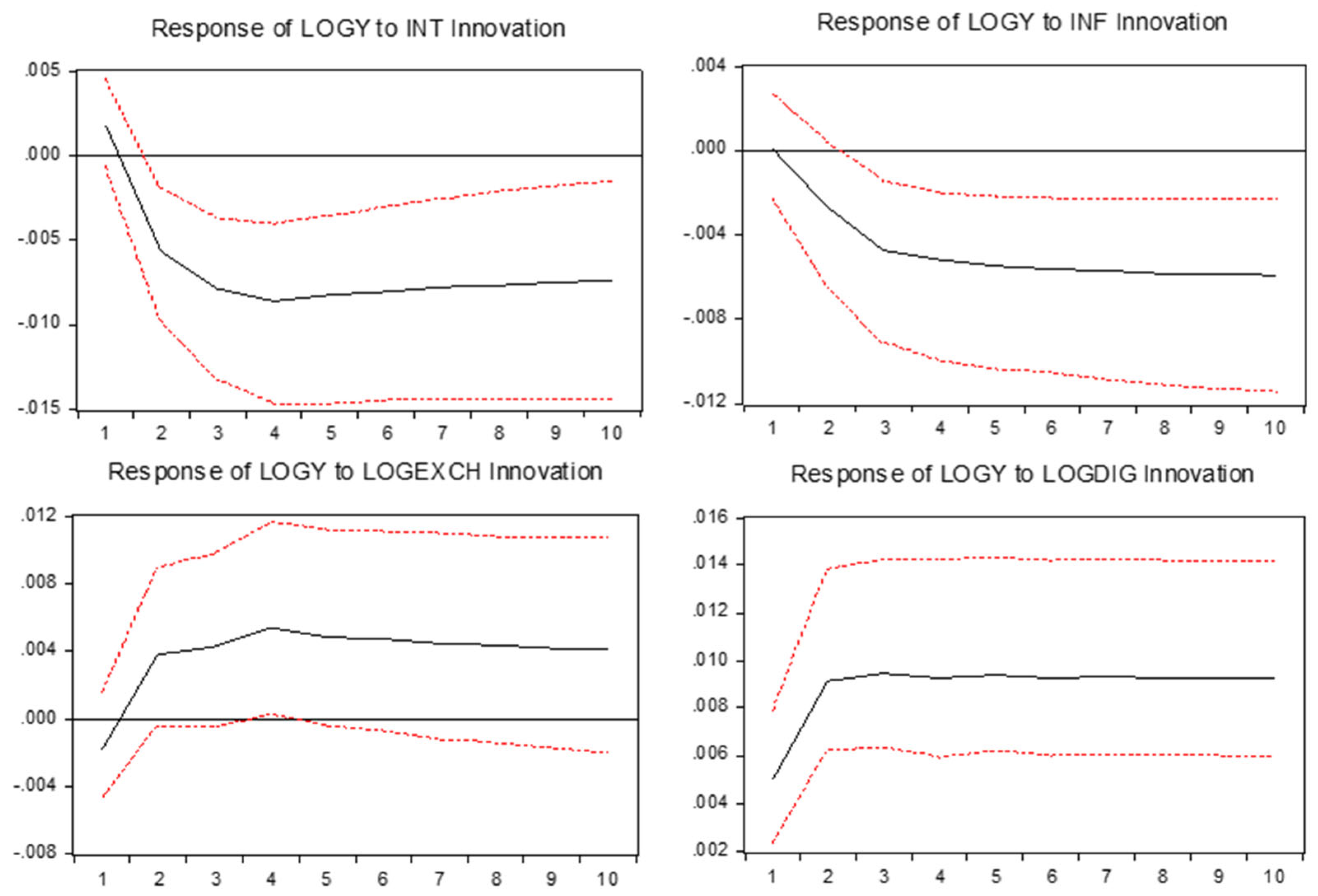

- A one standard error rise in interest rates, leads to a persistent downward revision in the growth rate of GDP with the effect remaining statistically significant at 95% confidence interval. The result confirms the conventional wisdom that higher borrowing costs dampen economic activity.

- A similar shock in inflation, would also result in a permanent reduction in GDP growth. This highlights the role played by inflation as a major constraint on long-term growth, emphasizing the importance of maintaining price stability.

- An appreciation of the domestic currency (a rise in the real effective exchange rate, ) leads to a rise in the growth rate of GDP. This suggests that the domestic economy benefits from stronger currency, possibly through improved capital inflows or reduced import costs and foreign debt. However, this is not a permanent effect as the economy returns to its long run equilibrium over time.

- Finally, a positive shock to the volume of digital payment, leads to a permanent rise in the growth rate of GDP, which is significantly different than zero. This finding supports the argument that digitalization promoted economic activity.

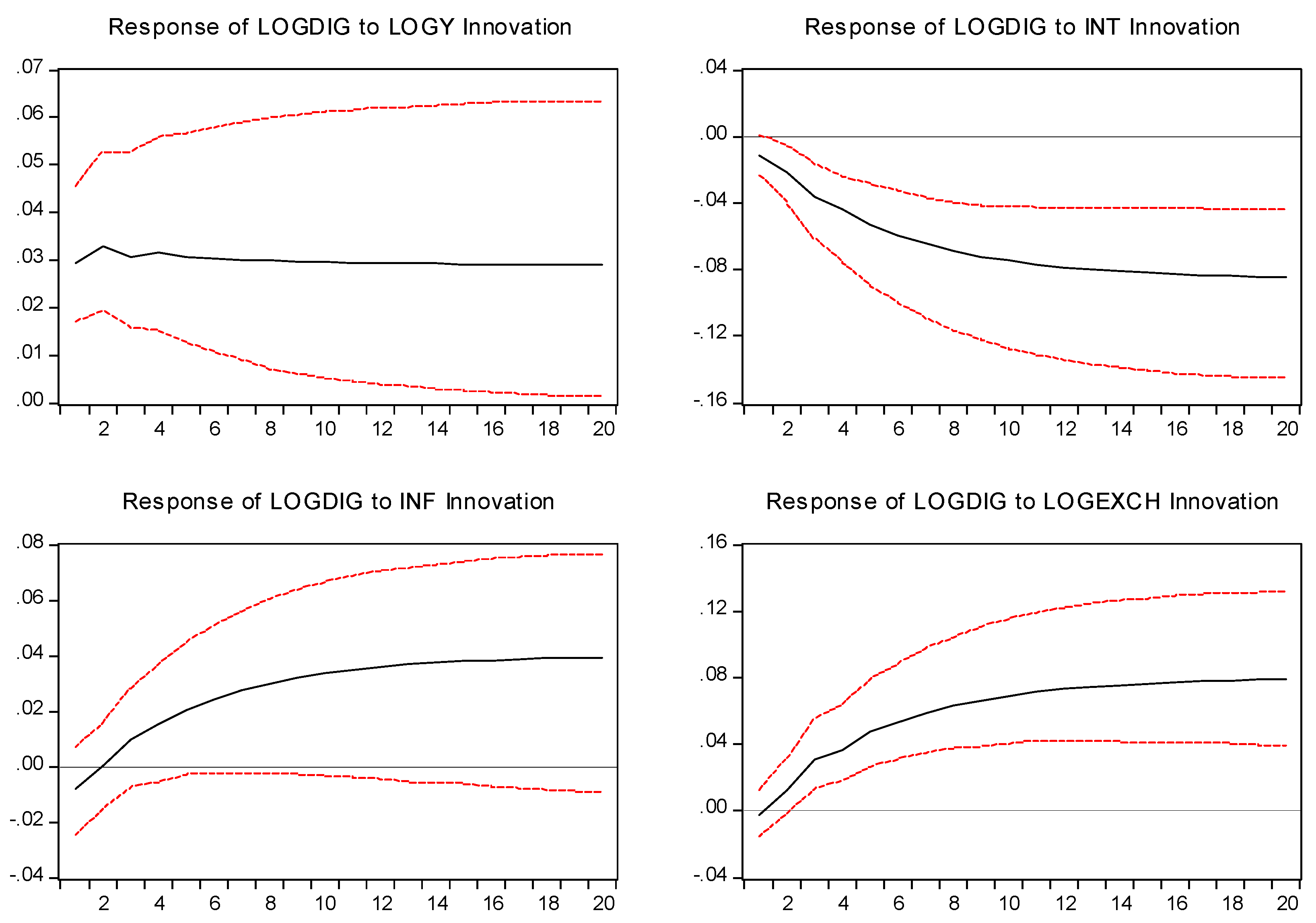

- A positive shock to the real GDP, leads to a permanent rise in the use of digital payments. Hence, digitalization goes in harmony with the size of the economy. Larger economies naturally drive the shift to digital payments because of increased consumer demand, business needs, and technological advancements.

- A positive shock to the interest rates, lowers the use of digital payments. The negative effect of financial conditions on digital payments is quite intuitive since consumers and businesses reduce spending as financial conditions tighten.

- Interestingly, a positive shock in inflation, raises the use of digital payments. As inflation rises, agents would be reluctant to hold cash, prompting people to adopt digital payments for speed and convenience.

- An appreciation of domestic currency (a rise in exchange rate, ) leads to a rise in the use of digital payments. A stronger currency boosts consumer confidence and purchasing power, encouraging more transactions.

4.4. Transmission Channels

- Durables: Including items such as vehicles and household appliances

- Semi-durables: Items with a medium lifespan, such as clothing and electronics

- Non-durables: Consumption goods such as food and fuel

- Services: Including education, healthcare, transportation, and recreation, etc.

- Aggregate productivity

- Sectoral productivity for industry

- Sectoral productivity for services

- Value added in the financial sector

- Credit to GDP ratio

| Dependent variable | in the cointegrating vector | Coefficient of the error correction term | R-square |

Trace test on no cointegration | Trace test on single cointegration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.227 (0.021)** |

-0.006 (0.041) |

0.671 | 94.62** | 70.22 | |

| 0.611 (0.054)** |

-0.055 (0.158) |

0.373 | 89.10** | 47.86 | |

| 0.352 (0.053)** |

-0.072 (0.096) |

0.559 | 83.06** | 48.71* | |

| 0.188 (0.017)** |

-1.644 (0.160)** |

0.722 | 149.56** | 44.82 | |

| 0.331 (0.030)** |

-0.328 (0.169) |

0.405 | 80.47** | 39.37 |

| Dependent variable | in the cointegrating vector | Coefficient of the error correction term | R-square |

Trace test on no cointegration | Trace test on single cointegration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.014 (0.029) |

-0.075 (0.029)** |

0.689 | 82.17** | 46.69 | |

| 0.060 (0.058) |

-0.058 (0.030) |

0.795 | 94.62** | 45.22 | |

| 0.029 (0.017) |

-0.206 (0.060)** |

0.884 | 91.27** | 49.74* |

| Dependent variable | in the cointegrating vector | Coefficient of the error correction term | R-square |

Trace test on no cointegration | Trace test on single cointegration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.540 (0.084)** |

-0.025 (0.043) |

0.339 | 63.44 | 36.53 | |

| 0.402 (0.025)** |

-0.286 (0.051)** |

0.537 | 97.04** | 45.30 |

4.5. Robustness

- : volume of money transfers over mobile (smart phone) banking

- : volume of money transfers over internet banking

- : volume of credit card transactions over internet banking

- : the number of internet users per 100 people

- : the number of mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people

5. Conclusion

6. Policy Implications

Abbreviations

| ADF | Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributive Lag |

| DOLS | Dynamic least squares |

| e-money | Electronic money |

| ECT | Error correction term |

| FMOLS | Fully modified least squares |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GIRF | Generalized impulse response function |

| IRF | Impulse response function |

| KPSS | Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin |

| OIC | Organization of Islamic Cooperation |

| PP | Phillips-Perron |

| SIC | Schwarz Information Criterion |

| TURKSTAT | Turkish Statistical Institute |

| VAR | Vector autoregressive |

| VCA | Variance decomposition analysis |

| VECM | Vector error correction model |

References

- Cull; R. J.; Foster; V.; Jolliffe; D.M.; Lederman; D.; Mare; D.S., M. Veerappan. Digital Payments and the COVID-19 Shock : The Role of Preexisting Conditions in Banking, Infrastructure, Human Capabilities, Digital Regulation.” World Bank Group, 2023. Accessed: Dec. 12, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar; C.J.; Ayunda; V.T.; Suhendra; I.; Ginanjar; R.A.F., L. N. Kholishoh. Estimating the effects of electronic money on the income velocity of money in Indonesia,” ijirss, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 390–397, Jan. 2024. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099454311132327828/IDU08c76166f0dda20435909e82051f6aa962419. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Q. Liu. Study on the Influence of Internet Payment on the Velocity of Money Circulation in China,” in Business Intelligence and Information Technology, vol. 107, A. E. Hassanien, Y. Xu, Z. Zhao, S. Mohammed, Z. Fan, Eds., in Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, vol. 107., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 577–593. [CrossRef]

- Putra; H. S.; Huljannah; M.; Padang; U.N.; Indonesia, M. Putri. Analysis of the Demand for Money and the Velocity of Money in the Digital Economy Era: A Case Study in Indonesia,” rep, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 110–125, Apr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujunwa; A.; Onah; E.; Ujunwa; A.I.; Okoyeuzu; C.R., E. U. Kalu. Financial innovation and the stability of money demand in Nigeria,” African Development Review, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 215–231, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Prabheesh; K. P.; Affandi; Y.; Gunadi, S. Kumar. Impact of Public Debt, Cashless Transactions on Inflation in Emerging Market Economies: Evidence from the COVID-19 Period,” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 557–575, Feb. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar; A.; Frost; J.; Guerra; R.; Kamin; S.; Digital payments; A.T., informality and economic growth.” Bank for International Settlements 2, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bis.org/publ/work1196.

- Marmora, P., B. J. Mason. Does the shadow economy mitigate the effect of cashless payment technology on currency demand? dynamic panel evidence,” Applied Economics, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 703–718, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Setor; T.K.; Senyo; P.K., A. Addo. Do digital payment transactions reduce corruption? Evidence from developing countries,” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 60, p. 101577, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kasri; R.A.; Indrastomo; B.S.; Hendranastiti; N.D., M. B. Prasetyo. Digital payment and banking stability in emerging economy with dual banking system,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 11, p. e11198, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.; Wu, J. J. Xiao. The impact of digital finance on household consumption: Evidence from China,” Economic Modelling, vol. 86, pp. 317–326, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- 12. R. Zhou, “Sustainable Economic Development, Digital Payment, and Consumer Demand: Evidence from China,” IJERPH, vol. 19, no. 14, p. 8819, Jul. [CrossRef]

- Birigozzi; A. ; De Silva, P. Luitel. Digital payments and GDP growth: A behavioural quantitative analysis,” Research in International Business and Finance, vol. 75, p. 102768, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hasan; I. ; De Renzis, H. Schmiedel. Retail Payments and Economic Growth,” Bank of Finland, Research Paper 19, 2012. Accessed: Feb. 01, 2025.

- Patra, B., N. Sethi. Does digital payment induce economic growth in emerging economies? The mediating role of institutional quality, consumption expenditure, bank credit,” Information Technology for Development, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 57–75, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tee, H.-H., H. -B. Ong. Cashless payment and economic growth,” Financ Innov, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 4, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wong; T. -L.; Lau; W.-Y., T.-M. Yip. Cashless Payments and Economic Growth: Evidence from Selected OECD Countries,” Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, vol. 9, no. s1, pp. 189–213, Jul. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang; Y.; Zhang; G.; Liu; L.; De Renzis, H. Schmiedel. Retail payments and the real economy,” Journal of Financial Stability, vol. 44, p. 100690, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- PwC. Digital Banking Overview and Potential in Turkey,” 2021. Accessed: Feb. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.strategyand.pwc.

- Eti, H.S. . Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Electronic Payment Systems in Turkey,” Sosyal Bilimler Metinleri, vol. 2022, no. 2, pp. 142–165, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kahveci; E. ; Avunduk; Z.B.; Daim, S. Zaim. The role of flexibility, digitalization, crisis response strategy for SMEs: Case of COVID-19,” Journal of Small Business Management, pp. 1–38, Aug. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V., A. Das. Digital payments in India — How demonetization and COVID-19 shaped adoption?,” Economics Letters, vol. 246, p. 112074, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bai; B.; Um; K.-H., H. Lee. The strategic role of firm agility in the relationship between IT capability and firm performance under the COVID-19 outbreak,” JBIM, vol. 38, no. 5, pp. 1041–1054, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey; D.; Willesson; M.; Bergendahl, T. Lindblom. Benefits from a Changing Payment Technology in European Banking,” Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 1631–1652, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt; A. ; Klapper; L.; Singer; D.; Ansar; S.; Hess, The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. World Bank Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zins, A., L. Weill. The determinants of financial inclusion in Africa,” Review of Development Finance, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 46–57, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Chen; H.; Liu, Z. Wang. Can Industrial Digitalization Boost a Consumption-Driven Economy? An Empirical Study Based on Provincial Data in China,” JTAER, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 2377–2399, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., L. Klapper. Measuring Financial Inclusion: Explaining Variation in Use of Financial Services across and within Countries,” eca, vol. 2013, no. 1, pp. 279–340, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. . Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability,” Borsa Istanbul Review, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 329–340, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Change; P.M.R.E.T.,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 98, no. 5, pp. 71–102, 1990.

- Beck; T.; Pamuk; H.; Ramrattan; R.; Payment instruments; B.R.U.; finance; development,” Journal of Development Economics, vol. 133, pp. 162–186, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Szabó; I.; Ternai; K.; Prosser, T. Kovács. The impact of digitalization on SMEs GDP contribution,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 239, pp. 1807–1814, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Daud; S.; Mohd; N.; Financial inclusion; A.H.A., economic growth and the role of digital technology,” Finance Research Letters, vol. 53, p. 103602, 23. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Kim; D.-W.; Yu; J.-S., M. K. Hassan. Financial inclusion and economic growth in OIC countries,” Research in International Business and Finance, vol. 43, pp. 1–14, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Prete, A.L. . Digital and Financial Literacy as Determinants of Digital Payments and Personal Finance,” Economics Letters, vol. 213, p. 110378, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Portillo; A.; Almodóvar-González, R. Hernández-Mogollón. Impact of ICT development on economic growth. A study of OECD European union countries,” Technology in Society, vol. 63, p. 101420, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Prabheesh, K., R. E. Rahman. MONETARY POLICY TRANSMISSION AND CREDIT CARDS: EVIDENCE FROM INDONESIA,” BEMP, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 137–162, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tran, L., W. Wang. Cashless Payments Impact to Economic Growth: Evidence in G20 Countries and Vietnam—Vietnamese Government with a Policy to Support Cashless Payments,” AJIBM, vol. 13, no. 04, pp. 247–269, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar; T. ; Suresha; B.; Sriram, R. Rajesh.. Impact of Digital Payments on Economic Growth: Evidence from India,” IJITEE, vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 553–557, Oct. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.S., D. Kumarasamy. Is There Any Nexus between Electronic Based Payments in Banking and Inflation? Evidence from India,” IJEF, vol. 7, no. 9, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mamudu, Z.U., G. O. Gayovwi. Cashless Policy and Its Impact on The Nigerian Economy,” International Journal of Education and Research, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 111–132, 2019.

- Azeez N; A. ; Haque; M.I., S. M. J. Akhtar. Digital Payment and Economic Growth: Evidence from India,” AEQ, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 79–93, Apr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givelyn; I. ; Rohima; S.; Mardalena, F. Widyanata. The Impact of Cashless Payment on Indonesian Economy: Before and During Covid-19 Pandemic,” JEP, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 89–104, Aug. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoh; D. ; Olopade; B.C., O. S. Eseyin. Digital Payment And Economic Growth: Evidence From Nigeria,” International Journal of Management, Social Sciences, Peace and Conflict Studies, vol. 6, pp. 225–238, Mar. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, E., G. Çi̇zgi̇ci̇ Akyüz. Türkiye’de Dijital Bankacilik ve Ekonomik Büyüme İlişkisi,” Marmara Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 223–246, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Segovia, M.A.F., L. E. Torre Cepeda. Financial development and economic growth: New evidence from Mexican States,” Regional Science Policy & Practice, vol. 16, no. 7, p. 100028, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, E. . Digital Transformation in SMEs: Enablers, Interconnections, a Framework for Sustainable Competitive Advantage,” Administrative Sciences, vol. 15, no. 3, p. 107, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Digitalization; E.K., Digital Transformation in MSMEs in Turkey,” International Journal of Small and Medium Enterprises and Business Sustainability, vol. 8, no. 2, Art. no. 2, 2023.

- Özkan, G.S., H. Çelik. Bilgi İletişim Teknolojileri İle Ekonomik Büyüme Arasindaki İlişki: Türkiye İçin Bir Uygulama,” Uluslararası Ticaret ve Ekonomi Araştırmaları Dergisi, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Bozkurt, “Pandemi Döneminde Çalışma: Ekonomik Kaygılar, Dijitalleşme ve Verimlilik,” in Covıd-19 Pandemisinin Ekonomik, Toplumsal ve Siyasal Etkileri, Istanbul University Press, 2020, pp. 115–136. 2020. [CrossRef]

- TURKSTAT. Survey on Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Usage in Households and by Individuals.” Turkish Statistical Institute, 2022. Accessed: Apr. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Survey-on-Information-and-Communication-Technology-(ICT)-Usage-in-Households-and-by-Individuals-2022-455. 2022.

- Dickey, D.A., W. A. Fuller. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series With a Unit Root,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, vol. 74, no. 366, p. 427, Jun. 1979. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B., P. Perron. Testing for a unit root in time series regression,” Biometrika, vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 335–346, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski; D.; Phillips; P.C.B.; Schmidt, Y. Shin. Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root,” Journal of Econometrics, vol. 54, no. 1–3, pp. 159–178, Oct. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Zivot, E., D. W. K. Andrews. Further Evidence on the Great Crash, the Oil-Price Shock, the Unit-Root Hypothesis,” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 251–270, Jul. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. . Estimation and Hypothesis Testing of Cointegration Vectors in Gaussian Vector Autoregressive Models,” Econometrica, vol. 59, no. 6, p. 1551, Nov. 1991. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y., K. S. Lai. Finite-Sample Sizes Of Johansen’s Likelihood Ratio Tests For Cointegration,” Oxf Bull Econ Stat, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 313–328, Aug. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Harbo; I.; Johansen; S.; Nielsen, A. Rahbek. Asymptotic Inference on Cointegrating Rank in Partial Systems,” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 388–399, Oct. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Vector autoregressive models; H.L.,” in Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Empirical Macroeconomics, N. Hashimzade and M. A. Thornton, Eds., Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, E., A. Odabaş. Central Banks’ Communication Strategy and Content Analysis of Monetary Policy Statements: The Case of Fed, ECB and CBRT,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 235, pp. 618–629, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kahveci, E. . Monetary Policy Strategies after The Global Financial Crisis: Comparison of Developed and Developing Country Experiences,” in Economic Crises: A Review and Directions for Research, in Economic Issues, Problems and Perspectives., Newyork: Nova Science Publishers, 2022, pp. 169–204. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H.H., Y. Shin. Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models,” Economics Letters, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 17–29, Jan. 1998. [CrossRef]

- BIS. Annual Economic Report 2021,” Annual Economic Report, Jun. 2021, Accessed: Apr. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2021e.

- Suri, T., W. Jack. The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money,” Science, vol. 354, no. 6317, pp. 1288–1292, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

| Digital Payments (Independent Variable) |

→ | Transmission Channels (Mechanisms) |

|---|---|---|

| Increased online transaction volume | 1. Consumption Channel [11,12,27,28,29] | |

| Mobile and card-based payments | - Faster money circulation [2,3,4,5] | |

| Instant payments infrastructure | - Lower transaction costs [25] | |

| 2. Investment & Credit Access Channel [25,30] | ||

| - Improved access to credit (esp. SMEs) [31,32] | ||

| - Better risk assessment via data [10] | ||

| 3. Informality Reduction Channel [7,8,25] | ||

| - More transparency in transactions [9] | ||

| - Reduced shadow economy [9] | ||

| 4. Financial Inclusion and Literacy Channel [25,26,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,36] | ||

| 5. Increased Productivity [23,24,31] |

| Authors | Country | Time Period | Dependent variable | Independent – Control Variables |

Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguilar et al. [7] | 101 countries | 2014-2019 | GDP growth, productivity | Digital payments, inflation, trade openness, human capital, population, average hours worked | Panel Regression | Digital payments raise economic growth, lower informal labor. |

| Liu and Liu [3] | China | 2000-2020 | Velocity of money | Internet payment, GDP, interest rates, inflation | Regression analysis | Internet payment increases the velocity of money. |

| Ravikumar et al., [39] | India | 2011-2019 | Economic Growth: GDP | Digital payments | OLS, ADRL co-integration | Digital payments positively affect growth in the short run only. |

| Tran & Wang, [38] | Vietnam and G20 countries | 2011-2020 | GDP | Debt card, credit card, e-money, check, inflation, population growth, secondary school enrollment, trade openness | Panel Regression | Economic growth is negatively related to debit, credit cards and e-money payment; positively related to check payments. |

| Tee & Ong, [16] | Five European Union (EU) countries | 2000-2012 | Real gross domestic product (GDP/CPI) | Cashless payment. (Telegraphic transfer, card, electronic money, and cheque payment) | Pedroni residual cointegration and VECM | Cashless payment has a positive impact on economic growth in the long run. |

| Reddy & Kumarasamy, [40] | India | 2007-2013 | Industrial production, wholesale price index | E-payments | VECM | Granger causality: both inflation and economic growth drive the adoption of electronic payments. |

| Bulut & Çizgici Akyüz, [45] | Turkey | 2011-2019 | GDP | Digital Banking Transaction Volume | ARDL Cointegration | Digital banking positively affects economic growth in the short and long run. |

| Kasri et al. [10] | Indonesia | 2013-2021 | Financial Stability | Digital payment transactions | VECM, VAR and ARDL | Digital payment transactions have a long-run relationship with financial stability. |

| Flores Segovia & Torre Cepeda [46] | Mexico | 2005-2018 | GDP Growth | Credit, e-money, inflation, public expenditure, infrastructure, human capital, dummy economic crisis | Generalized Method of Moments, Granger Causality | Bank credit and e-money have a positive and statistically significant effect on GDP per capita growth. |

| Marmora and Mason [8] | 37 countries | 2004-2014 | Velocity of money | Cashless payment, interest rates, inflation, income per capita, credit to GDP, shadow economy | System GMM | Cashless payment systems raise velocity only in countries with a smaller shadow economy. |

| Putra et al. [4] | Indonesia | 2010-2019 | Velocity of money | Debt card, credit card, electronic money. GDP, interest rates | ARDL bounds testing | Debit and credit cards increase velocity of money, whereas e- money has no effect. |

| Anwar et al. [2] | Indonesia | 2009-2022 | Velocity of money | E-money transactions, Inflation, exchange rate, interest rate, money supply | ARDL Bounds Testing | E-money reduces velocity of money. |

| Prabheesh et al. [6] | 10 Emerging Economies | 2020-2021 | Inflation | Cashless transactions, Oil prices, public debt, interest rate, production index | Panel regression | Cashless transactions raise inflation. |

| Hasan et al. [14] | 27 European countries | 1995-2009 | GDP growth | Cashless transactions (card, cheque, money transfers), Lag of GDP per capita, interest rate | Panel regression | There is a positive relationship between cashless transactions and growth. The link is strongest for card payments, followed by credit transfers and direct debits. |

| Wong et al. [17] | 15 OECD countries | 2007-2016 | GDP growth | Debt card, credit card, e-money. inflation, population, secondary equation, trade openness | Panel (random effects) model | Debit card payment has a positive effect on growth; whereas credit card, e-money, and cheque payment have no impact. |

| Patra and Sethi [15] | 25 BIS countries | 2012-2020 | GDP growth | Cashless payments, institutional quality, consumption, bank credits, inflation, exchange rate, life expectancy, unemployment | Panel Regression | Debit card and cheque payments have a positive impact on growth. E-money has a negative impact; credit card payment has no impact. |

| Setor et al. [9] | 111 countries | 2012-2018 | Corruption | Digital payment transactions per capita, GDP per capita, legal system, internet access | Panel regression | Digital transactions reduce corruption. |

| Variable | Abbreviation | Source | Note |

| Real gross domestic product | TURKSTAT | Seasonally adjusted, log | |

| Interest rates | CBRT, Authors’ own calculation | Weighted average of consumer loans and commercial loans | |

| Inflation | TURKSTAT | Quarterly change in consumer price inflation, seasonally adjusted | |

| Real effective exchange rate | CBRT | Log | |

| Digital banking | Turkish Banking Association; Authors’ own calculation | Volume of online payments, seasonally adjusted, discounted by price deflator, log |

| Variable | Average | Standard Deviation |

Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.978 | 0.259 | 5.420 | 4.559 | |

| 0.182 | 0.073 | 0.552 | 0.098 | |

| 0.038 | 0.042 | 0.238 | 0.005 | |

| 4.496 | 0.275 | 4.850 | 3.863 | |

| 2.636 | 0.807 | 3.461 | 0.723 | |

| 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.152 | -0.113 | |

| 0.005 | 0.037 | -0.078 | 0.171 | |

| 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.138 | -0.088 | |

| -0.008 | 0.072 | 0.200 | -0.268 | |

| 0.039 | 0.092 | -0.204 | 0.314 |

| Variable | ADF | PP | KPSS | Result | ||||

| C | C+T | C | C+T | C | C+T | |||

| Level | 0.16 | -3.02 | -0.01 | -2.98 | 1.11** | 0.07 | I(1) | |

| ∆ | -10.48** | -10.44** | -10.48** | -10.44** | 0.06 | I(0) | ||

| Level | -0.67 | -1.33 | 0.31 | -0.38 | 0.55* | 0.22** | I(1) | |

| ∆ | -4.21** | -4.47** | -4.31** | -4.46** | 0.48* | 0.09 | I(0) | |

| Level | -3.01* | -4.20** | -2.83 | -4.15** | 0.73* | 0.23** | I(1) | |

| ∆ | -10.63** | -19.31** | 0.37 | 0.18 | I(0) | |||

| Level | 0.11 | -2.85 | -0.33 | -2.62 | 0.99** | 0.26** | I(1) | |

| ∆ | -11.80** | -11.94** | -11.88** | -12.66** | 0.15 | 0.06 | I(0) | |

| Level | -2.89 | -1.43 | -3.46* | -1.35 | 0.99** | 0.28** | I(1) | |

| ∆ | -8.58** | -9.43** | -9.58** | 0.45 | 0.07 | I(0) | ||

| Test | Test-statistic | p-value |

| Serial correlation (lag 1) | 1.201 | 0.245 |

| Serial correlation (lag 4) | 1.080 | 0.339 |

| Serial correlation (lag 8) | 1.106 | 0.337 |

| Normality | 58.265 | 0.000 |

| Homoscedasticity | 439.640 | 0.042 |

| r | n-r | Model (i) | Model (ii) |

| 0 | 5 | 98.63** (76.97) | 82.17** (69.82) |

| 1 | 4 | 62.60** (54.07) | 46.69 (47.85) |

| 2 | 3 | 29.86 (35.19) | 27.45 (29.80) |

| 3 | 2 | 16.34 (20.26) | 14.09 (15.49) |

| 4 | 1 | 4.90 (9.16) | 4.19 (3.84) |

| Equation | Test statistic | p-value |

| 4.404 | 0.036 | |

| 0.942 | 0.332 | |

| 2.656 | 0.103 | |

| 0.091 | 0.763 | |

| 8.256 | 0.004 |

| Null hypothesis |

Pairwise Granger causality |

Short run Granger causality |

Short run + Long run Granger causality |

| does not Granger cause | 2.435 (0.096) | 8.542** (0.004) | 12.978** (0.00) |

| does not Granger cause | 3.476** (0.037) | 2.808 (0.094) | 2.929 (0.231) |

| does not Granger cause | 0.352 (0.705) | 1.333 (0.248) | 4.569 (0.102) |

| does not Granger cause | 5.158** (0.008) | 2.686 (0.104) | 5.490 (0.064) |

| does not Granger cause | 0.925 (0.402) | 12.697** (0.000) | 10.107** (0.006) |

| does not Granger cause | 3.826** (0.027) | 1.212 (0.271) | 0.901 (0.637) |

| does not Granger cause | 0.558 (0.575) | 3.535 (0.065) | 5.309 (0.070) |

| does not Granger cause | 0.164 (0.850) | 2.775 (0.097) | 14.291** (0.001) |

| -0.041 (0.018)* |

-0.070 (0.029)* |

0.318 (0.079)** |

|||

| -0.023 (0.071) |

0.188 (0.091)* |

0.655 (0.312)* |

-0.387 (0.350) |

0.260 (0.156) |

|

| -0.179 (0.061)** |

-0.165 (0.103) |

-0.188 (0.267) |

0.298 (0.299) |

0.483 (0.133)** |

|

| -0.072 (0.068) |

-0.169 (0.116) |

-0.365 (0.301) |

-0.024 (0.338) |

-0.006 (0.152) |

|

| 0.090 (0.026)** |

-0.205 (0.043)** |

-0.001 (0.112) |

-0.343 (0.126)** |

-0.187 (0.056)** |

|

| 0.051 (0.024)* |

0.006 (0.050) |

-0.019 (0.130) |

0.157 (0.146) |

-0.022 (0.066) |

|

| 1.027 (0.227)** |

0.608 (0.287)* |

0.198 (1.002) |

0.695 (1.122) |

0.128 (0.502) |

|

| -0.303 (0.443) |

-1.781 (0.754)* |

-0.812 (1.952) |

3.683 (2.185) |

-0.076 (0.978) |

|

| -0.039 (0.010)** |

0.007 (0.017) |

-0.039 (0.044) |

0.045 (0.049) |

-0.005 (0.021) |

|

| -0.013 (0.028) |

-0.045 (0.048) |

0.126 (0.125) |

-0.140 (0.140) |

0.051 (0.063) |

|

| R2 | 0.809 | 0.520 | 0.349 | 0.209 | 0.394 |

| Variance Decomposition of LOGY | ||||||

| Period | S.E. | LOGY | INF | LOGDIG | LOGEXC | INT |

| 1 | 0.013 | 100.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.036 | 64.384 | 6.869 | 7.226 | 10.968 | 10.554 |

| 10 | 0.051 | 59.062 | 9.837 | 8.157 | 11.512 | 11.432 |

| 20 | 0.072 | 57.463 | 12.270 | 8.582 | 10.953 | 10.732 |

| Variance Decomposition of INF: | ||||||

| Period | S.E. | LOGY | INF | LOGDIG | LOGEXC | INT |

| 1 | 0.024 | 0.095 | 99.905 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.043 | 1.119 | 68.013 | 0.777 | 26.886 | 3.206 |

| 10 | 0.057 | 0.954 | 53.186 | 0.715 | 43.045 | 2.099 |

| 20 | 0.084 | 0.913 | 35.761 | 0.438 | 59.587 | 3.301 |

| Variance Decomposition of LOGDIG: | ||||||

| Period | S.E. | LOGY | INF | LOGDIG | LOGEXC | INT |

| 1 | 0.061 | 14.789 | 0.302 | 84.909 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.175 | 12.859 | 5.099 | 55.550 | 15.188 | 11.304 |

| 10 | 0.319 | 8.983 | 6.019 | 37.220 | 25.313 | 22.466 |

| 20 | 0.558 | 5.892 | 7.069 | 27.132 | 30.894 | 29.012 |

| Variance Decomposition of LOGEXC: | ||||||

| Period | S.E. | LOGY | INF | LOGDIG | LOGEXC | INT |

| 1 | 0.069 | 1.206 | 0.550 | 0.001 | 98.243 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.116 | 0.748 | 0.321 | 0.489 | 96.366 | 2.076 |

| 10 | 0.162 | 0.542 | 0.424 | 0.450 | 96.957 | 1.627 |

| 20 | 0.232 | 0.443 | 0.592 | 0.456 | 97.529 | 0.980 |

| Variance Decomposition of INT: | ||||||

| Period | S.E. | LOGY | INF | LOGDIG | LOGEXC | INT |

| 1 | 0.031 | 1.362 | 10.562 | 3.105 | 8.407 | 76.565 |

| 5 | 0.119 | 4.016 | 8.198 | 3.463 | 24.590 | 59.733 |

| 10 | 0.187 | 4.068 | 6.467 | 3.355 | 26.828 | 59.282 |

| 20 | 0.284 | 3.948 | 5.093 | 3.252 | 28.460 | 59.246 |

| Method | Johansen | ARDL | FMOLS | DOLS |

| -0.422 | -0.006 | -0.338 | -0.746 | |

| (0.483) | (0.185) | (0.114)** | (0.269)** | |

| -3.143 | -1.735 | -0.218 | 0.021 | |

| (0.906)** | (0.719)* | (0.185) | (0.342) | |

| 0.828 | 0.588 | 0.345 | 0.372 | |

| (0.155)** | (0.045)** | (0.042)** | (0.057)** | |

| 0.227 | 0.204 | 0.205 | 0.183 | |

| (0.035)** | (0.020)** | (0.013)** | (0.018)** | |

| F-statistic: | 6.598 | |||

| t-statistic: | 4.329 |

| Method | Digital payments | Money transfers over mobile banking |

Money transfers over internet banking | Credit card transactions over internet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0.422 | -0.034 | -0.147 | -0.361 | |

| (0.483) | (0.160) | (0.187) | (0.386) | |

| -3.143 | -1.365 | -1.221 | -2.963 | |

| (0.906)** | (0.248)** | (0.330)** | (0.684)** | |

| 0.828 | 0.025 | 0.253 | 0.285 | |

| (0.155)** | (0.062) | (0.065)** | (0.108)** | |

| 0.227 | 0.070 | 0.142 | 0.360 | |

| (0.035)** | (0.006)** | (0.023)** | (0.047)** | |

| Lag length: | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Variable | Baseline | Alternative-1 | Alternative-2 | |

| -0.422 | -0.649 | -1.079 | ||

| (0.483) | (0.274)* | (1.164) | ||

| -3.143 | -1.843 | -2.227 | ||

| (0.906)** | (0.715)* | (1.025)* | ||

| 0.828 | 0.736 | 0.769 | ||

| (0.155)** | (0.102)** | (0.134)** | ||

| 0.227 | 0.188 | 0.266 | ||

| (0.035)** | (0.042)* | (0.044)** | ||

| 0.303 | ||||

| (0.103)** | ||||

| -0.542 | ||||

| (0.341) | ||||

| VAR model | Threshold VAR Model | |||||

| Variable | ||||||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| -0.422 | -0.301 | -0.583 | ||||

| (0.483) | (0.319) | (0.447) | ||||

| -3.143 | -3.735 | -2.908 | ||||

| (0.906)** | (1.130)** | (0.894)** | ||||

| 0.828 | 0.841 | 0.769 | ||||

| (0.155)** | (0.168)** | (0.120)** | ||||

| 0.227 | 0.266 | 0.158 | ||||

| (0.035)** | (0.011)** | (0.036)** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).