1. Introduction

Accurate smoke segmentation is essential for environmental monitoring and industrial safety, facilitating early fire detection, pollution control, and the assessment of emissions from various industrial activities. Among these, smoke resulting from quarry blasting presents unique and complex challenges due to its variable characteristics, including irregular shapes, mixed textures of dust and debris, and varying levels of opacity. These complexities necessitate a segmentation model capable of distinguishing smoke from surrounding elements and accurately capturing its dynamic structure and boundaries across diverse industrial settings. Addressing these challenges requires advanced deep learning architectures that can effectively handle the intricate and dynamic nature of smoke plumes, ensuring precise and reliable segmentation in real-world applications.

Semantic object segmentation has significantly advanced with deep learning architectures like UNet [

1] and Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) [

2], which utilize encoder-decoder structures to capture and reconstruct complex image features. However, these models often struggle with dynamic scenes such as smoke plumes, influenced by factors like wind, humidity, and varying smoke sources. This variability limits their adaptability for transient, high-variability conditions essential for low-latency monitoring. To address this, efficient CNN architectures like MobileNet [

3], EfficientNet [

4], and ShuffleNet [

5] have been developed to achieve performance through reduced computational complexity. Additionally, Vision Transformers (ViTs) [

6] enhance the ability to capture global and contextual information, though they typically require higher computational resources. While these architectures offer significant improvements, they often involve trade-offs between computational efficiency and segmentation accuracy, particularly in resource-constrained environments where continuous, practical smoke segmentation is necessary.

Specialized studies in smoke segmentation, such as the deep Smoke Segmentation (DSS) model [

7], Frizzi et al. [

8], and Yuan et al. [

9], have explored advanced techniques to address these challenges. The DSS model employs a two-path fully convolutional network to extract global context, enhancing segmentation accuracy but increasing computational complexity. Frizzi et al. introduced a VGG16-based model that attempts to improve smoke plume segmentation performance compared to image processing techniques, yet this comes with higher model parameters and complexity. Yuan et al. [

9] proposed a lightweight model incorporating attention mechanisms to replace the global context extraction from two-path FCNs, achieving significant parameter reduction while maintaining strong performance. As far as we know, Yuan’s lightweight paper is the most recent work with a lightweight model and good performance targeting smoke segmentation, having already significantly reduced the parameters compared to previous smoke segmentation networks. To further improve smoke segmentation efficiency with a low-parameter model, we introduce SmokeNet, a novel and efficient UNet-based architecture specifically designed to meet the unique demands of smoke segmentation in both synthetic and real-world environments, with a particular focus on quarry smoke. Our contributions include:

Multiscale Convolutions with Rectangular Kernels: SmokeNet integrates a multiscale convolution module using rectangular-shaped kernels alongside standard kernels, allowing it to adapt to the irregular shapes often seen in smoke. This approach provides better spatial information, with vertically oriented kernels capturing the tall, narrow shapes typical of wildfire smoke and horizontally oriented kernels suited for the wide, low plumes found in quarry blast smoke.

Lightweight Multiview Linear Attention: To enhance feature integration without imposing high computational costs, SmokeNet incorporates a linear attention mechanism with multi-view element-wise multiplication, enabling the model to selectively attend to both spatial and channel-wise features. This design preserves accuracy while significantly reducing the parameter count, allowing smoke segmentation even in GPU-constrained settings.

Layer-Specific Loss: To optimize feature refinement, we introduce a layer-specific loss strategy that minimizes feature gaps across the network’s layers, fostering more detailed and precise feature learning. This approach enhances segmentation accuracy by aligning intermediate feature representations throughout the network, thereby supporting consistent and refined feature extraction without increasing model complexity.

2. Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning Methods for Smoke and Fire Segmentation

Recent studies have proposed various approaches to enhance smoke segmentation accuracy under diverse scenarios, ranging from indoor fires to satellite-based detection. Hou et al. [

10] presented a semantic segmentation method based on the DeepLabv3+ model, specifically targeting simultaneous flame and smoke detection in indoor environments. They introduced the Flame and Smoke Semantic Dataset (FSSD), demonstrating robust performance improvements. Similarly, Hu et al. [

11] introduced GFUNet, an optimized UNet-based architecture with specialized modules like HardRes, SCSE, and DSASPP, specifically tailored for smoke segmentation in forest and grassland fires using satellite imagery. Their work highlighted the effectiveness of advanced feature recalibration mechanisms in handling multispectral data.

Addressing the challenge of limited labeled data, Marto et al. [

12] developed an active learning framework for fire and smoke segmentation. By selectively annotating informative samples, their method significantly improved segmentation accuracy with fewer labeled instances. While beneficial for reducing annotation costs, their approach primarily focused on selecting training samples rather than architectural innovation.

Additionally, methods designed for enhancing image quality in challenging conditions have indirect relevance for smoke segmentation. Wang et al. [

13] introduced a recursive framework for low-light image enhancement, incorporating adaptive contrast adjustments and brightness perception networks. Such brightness-aware recursive strategies could inform smoke segmentation models that must handle variable illumination conditions.

In another direction, Peng et al. [

14] proposed a lightweight Adaptive Feature De-drifting module for image classification, effectively mitigating compression-induced artifacts. Although aimed at classification tasks, their modular design approach and robustness to image degradation offer useful insights for improving the reliability of smoke segmentation algorithms, particularly in scenarios involving compressed or degraded imagery.

2.2. Advances in Attention Mechanisms and Multiscale Feature Representation

The encoder-decoder paradigm has been pivotal in advancing image segmentation tasks. UNet++ [

15] enhanced this framework by introducing nested and dense skip pathways, effectively bridging semantic gaps between encoder and decoder features and improving segmentation accuracy through deep supervision. This indicates an improved feature flow among the different stages of the model compared to the original UNet [

1]. Additionally, UNet++ incorporates a pruned decoder to reduce the number of parameters, enhancing computational efficiency.

Expanding upon traditional encoder-decoder frameworks, ERFNet [

16] is designed to deliver high accuracy with reduced computational complexity. ERFNet utilizes factorized convolutions and residual connections to streamline the network, making it suitable for applications such as autonomous driving and robotics where real-time processing is essential. Similarly, DFANet [

17] introduces a dual attention mechanism that captures both spatial and channel-wise dependencies, enhancing feature representation and improving performance in semantic segmentation and object detection tasks. DFANet achieves a balance between speed and segmentation performance by aggregating discriminative features through a lightweight backbone and multi-scale feature propagation.

Inspired by enhanced feature learning, Deep Smoke Segmentation (DSS) [

7] employs a dual-path encoder-decoder structure based on fully convolutional networks, specifically designed for smoke segmentation. This architecture achieves good performance; however, the parameter count remains relatively high. Similarly, Frizzi et al. [

8] developed a convolutional neural network using VGG architectures with multiple kernel sizes to capture both global context and fine spatial details. This approach enhances segmentation performance across diverse datasets by effectively handling the dynamic and amorphous nature of smoke plumes, though it results in significant parameter counts.

To comprehensively extract global context features, attention-based mechanisms have been integrated into encoder-decoder architectures. Attention UNet [

18] incorporates attention gates into the UNet architecture, enabling the model to focus on relevant target structures and thereby improve segmentation accuracy. This selective focus helps in better delineating smoke regions from complex backgrounds. Additionally, CGNet [

19] introduces attention modules within a Context Guided Network framework, prioritizing salient features for efficient semantic segmentation on mobile devices. These attention mechanisms enhance the model’s ability to discern important features, thereby improving overall segmentation performance.

More recently, MobileViTv2 [

20] introduces a hybrid approach that combines convolutions with Vision Transformers to enhance feature representation for semantic segmentation tasks. By addressing the latency issues commonly associated with multi-headed self-attention (MHA) mechanisms, MobileViTv2 employs a separable self-attention mechanism with linear complexity. This improvement makes the model more practical for resource-constrained environments while maintaining competitive segmentation performance.

2.3. Enhancing Model Robustness and Computational Efficiency

Segmentation in GPU-constrained environments necessitates lightweight models that balance accuracy with computational efficiency. Several architectures have been developed to optimize computational resources through innovative techniques. MobileNet [

3], for instance, employs depthwise separable convolutions to reduce the number of parameters and computational load, making it suitable for mobile and embedded applications. Similarly, ShuffleNet [

5] introduces pointwise group convolutions and channel shuffle operations to achieve high efficiency without significant accuracy loss. EfficientNet [

4] utilizes a compound scaling method that uniformly scales network depth, width, and resolution, providing a family of models that offer a balance between performance and efficiency.

Building upon these lightweight foundations, UNeXt-S [

21] has shown promise in medical image segmentation by incorporating efficient convolutional operations and attention mechanisms. MALUNet [

22] introduces a lightweight architecture designed for skin lesion segmentation, integrating specialized attention modules to efficiently extract and fuse global and local features. LEDNet [

23] further refines lightweight segmentation by employing an asymmetric encoder-decoder architecture with channel split and shuffle operations, along with an Attention Pyramid Network (APN) in the decoder.

Recent advancements have specifically targeted the smoke segmentation task with a focus on enhancing parameter efficiency. Yuan et al. [

9] introduced a refined lightweight model optimized for efficient smoke segmentation, integrating attention mechanisms to efficiently extract salient features while minimizing computational demands. Despite these advances, the limited diversity and size of current datasets impede comprehensive assessment of model generalizability, highlighting the need for expanded datasets such as quarry smoke for more robust model validation.

Motivated by these gaps, we introduce SmokeNet, a novel lightweight architecture leveraging multiscale convolutions and multiview linear attention mechanisms specifically designed for dynamic and irregular smoke segmentation scenarios, such as quarry blast smoke. SmokeNet explicitly targets diverse real-world conditions, combining rigorous ablation studies and extensive cross-dataset evaluations to demonstrate robust and generalized segmentation performance.

3. Methodology

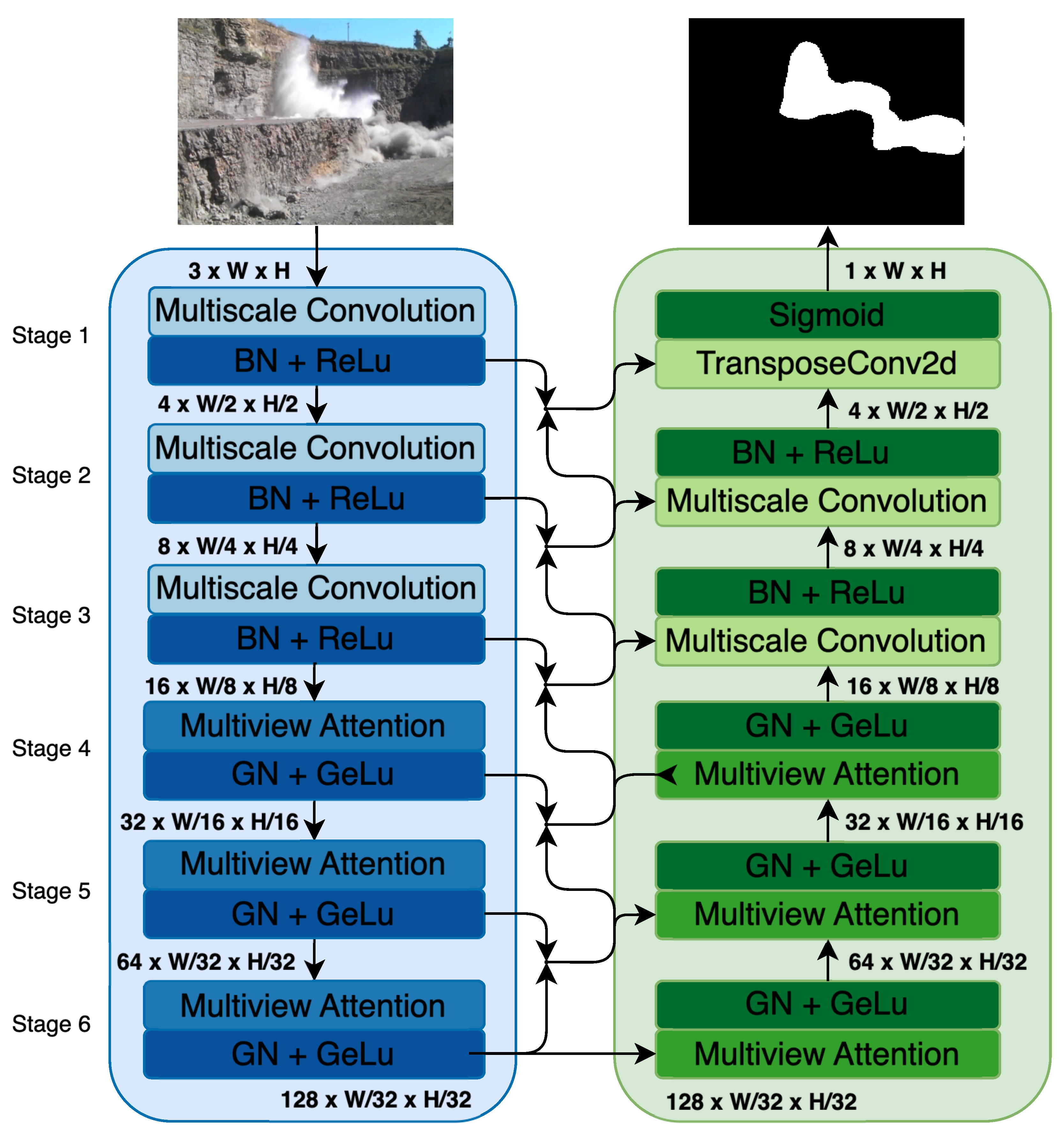

SmokeNet is designed explicitly for smoke segmentation in complex environments, particularly addressing the dynamic characteristics of quarry smoke. Inspired by U-Net, SmokeNet employs an encoder-decoder structure organized into six distinct stages, systematically reducing spatial resolution while increasing channel depth in the encoder and conversely reconstructing spatial resolution while reducing channel depth in the decoder. Specifically, the encoder begins with an initial spatial resolution of

with 4 channels at Stage 1, progressively reducing to spatial dimensions of

with 128 channels at Stage 6. Conversely, the decoder reconstructs the segmentation map by sequentially increasing spatial dimensions from

at Stage 6 to

at Stage 1, progressively reducing the number of channels. The encoder (Stages 1–6) focuses on extracting hierarchical features through multiscale convolutions and attention mechanisms, while the decoder (Stages 1–6) incorporates multiview linear attention mechanisms and skip connections to integrate detailed features from corresponding encoder stages. This strategic design enables SmokeNet to effectively capture and handle the variability and structural complexity of smoke plumes (

Figure 1).

3.1. Encoder

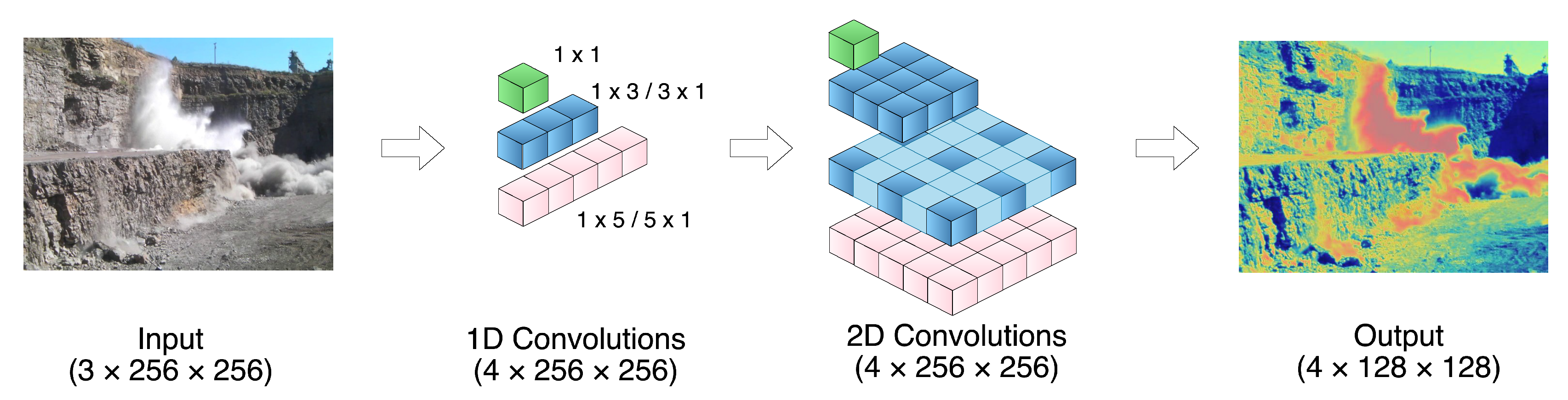

3.1.1. Multiscale Feature Extraction

The encoder stages (Stages 1-3) are responsible for extracting features across multiple spatial scales, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, enabling the model to effectively capture the variability inherent in smoke patterns. This multiscale extraction is facilitated by a dedicated multiscale module, which processes input feature tensors through a series of convolutional operations with varying kernel sizes, followed by batch normalization and activation functions. The Multiscale Module employs 1D convolutional layers with diverse kernel sizes, including

,

,

,

, and

. These convolutions are applied sequentially to the input tensor

, resulting in multiple feature maps that capture different spatial extents and orientations of smoke plumes. For instance, the

and

convolutions are adept at capturing elongated features in horizontal and vertical directions, respectively, while the

and

convolutions capture broader spatial contexts.

To construct larger and more complex 2D convolution operators efficiently, sequential 1D convolutions are employed. The equivalent 2D convolution operators, such as

,

,

, and

, are defined by applying two 1D convolutions in orthogonal directions:

As shown in Equations (

1)–(4), each operator is constructed by first applying a 1D convolution along one axis, followed by another 1D convolution along the orthogonal axis. For instance,

is achieved by applying

(horizontal) followed by

(vertical).

These operations, especially the rectangular kernel sizes targeting horizontal or vertical features, enable the module to capture a wide range of smoke shapes, from narrow and tall plumes common in campfires to wide and elongated patterns resulting from quarry blasts.

Let us denote the input tensor to the encoder as , where N represents the batch size, C is the number of channels, and H and W denote the spatial height and width of the feature maps, respectively.

For each stage, including the Multiscale Module, the input—either from the original image (Stage 1) or the output of the previous stage—is split into four chunks along the channel dimension. Each chunk

is processed independently using specific operations, as follows:

The convolutional operations in

include a range of kernel sizes and their sequential combinations to emulate 2D convolutions:

To address dimensional alignment, all outputs from the selected kernel operations are normalized to consistent dimensions () before concatenation. This is achieved by applying a convolution to adjust the channel count and using appropriate padding or cropping to match the spatial dimensions. These steps ensure compatibility during feature integration, preventing dimensional mismatches and enabling stable multiscale feature fusion, while maintaining efficiency across stages.

After processing, each chunk undergoes batch normalization to stabilize the learning process:

The outputs from all four chunks are concatenated along the channel dimension to form the combined feature map:

An identity mapping with activation is applied to the concatenated feature map to produce the final feature map:

where

is a

convolution if the channel dimensions of

and

differ, otherwise it is the identity function.

Finally, a

Max Pooling operation reduces the spatial dimensions:

By integrating batch normalization and RELU activation functions throughout the module, the encoder effectively captures both local and global contextual features while ensuring stable and efficient learning. The use of larger kernels and dilated convolutions in captures broader contextual information, and the inclusion of batch normalization after each path’s output normalizes feature distributions, facilitating deeper network training.

As shown in

Figure 2, the encoder of SmokeNet systematically extracts features through a combination of multiscale convolutions, dilated convolutions, activation functions, batch normalization, and strategic feature fusion. The incorporation of these elements enhances the model’s ability to capture the variability and structural complexity of smoke plumes in various environments.

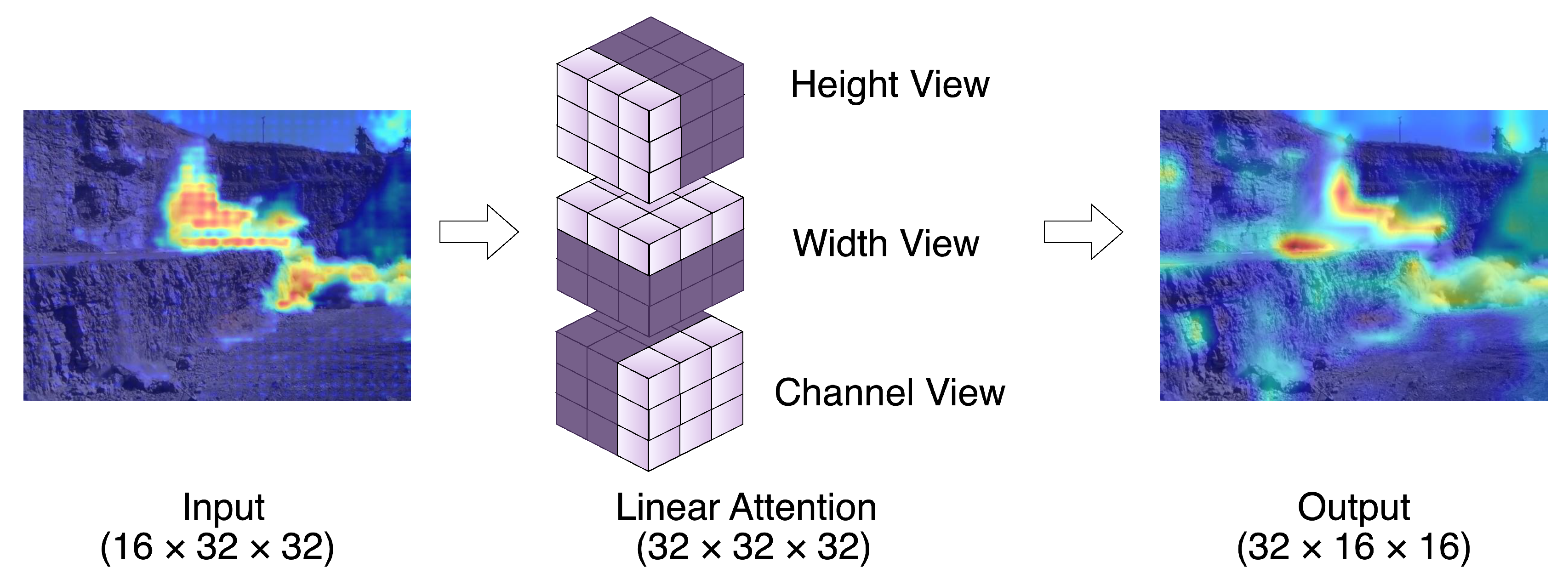

3.1.2. Multiview Linear Attention Mechanism

In encoder stages 4-6, multiview linear attention mechanisms are integrated to refine the encoded features, as shown in

Figure 3, focusing on essential elements while maintaining computational efficiency. SmokeNet employs the multiview attention mechanism across different dimensions of the feature tensor—channel, height, and width—providing a comprehensive enhancement of key features.

Let the input tensor at stage

k of the encoder be

. For the multiview operation, the tensor is split into four equal chunks along the channel dimension:

where each chunk

.

Each chunk undergoes a distinct processing operation involving element-wise multiplication with an attention map computed via softmax activation over specific dimensions:

where

denotes the softmax activation applied over the specified dimensions, and ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication.

The outputs from all four chunks are concatenated along the channel dimension to form the combined feature map:

This concatenated feature map is then processed by a pointwise convolution to integrate the multiscale features into a unified representation:

Following the convolution, layer normalization and GELU activation are applied to

. Finally, a

max pooling operation is performed to reduce the spatial dimensions, resulting in:

As shown in

Figure 3, the spatial view within the multiview attention mechanism is particularly essential for enhancing spatial feature consistency. By focusing on specific regions within the feature maps, the spatial view ensures robust encoding of intricate smoke shapes, such as those formed by narrow plumes or widespread quarry blast emissions. Similarly, the height-channel and width-channel views capture directional patterns and align encoded features with global contexts, enabling robust feature extraction for both narrow, tall plumes and wide, elongated patterns.

This strategic combination of multiview linear attention ensures that the encoder stages of SmokeNet (4-6) are adept at refining the variability and complexity of smoke patterns, delivering feature representations optimized for segmentation in the decoder.

3.2. Decoder

3.2.1. Decoder with Skip Connections

The decoder stages in SmokeNet (Stages 4-6) progressively reconstruct the spatial resolution of the feature maps using transposed convolutions. To enhance segmentation precision, skip connections are employed to transfer enriched features from the encoder to the corresponding decoder stages. These skip connections combine the encoder output at the current stage with the upsampled output of the lower-stage skip connection using element-wise addition, integrating features from multiple levels to ensure dimensional alignment and retain critical details necessary for accurate smoke segmentation.

Let the output tensor from the encoder at stage

k be denoted as

, where

,

, and

represent the number of channels, height, and width, respectively, at stage

k. The output of the lower-stage skip connection is denoted as

. The skip connection input at stage

k is computed by adding the encoder output with the upsampled lower-stage skip connection as follows:

where

represents an upsampling operation (e.g., transposed convolution) that aligns the spatial resolution of the lower-stage skip connection with the current stage.

3.2.2. Decoder Stage Operations

At each decoder stage, the input

is formed by adding the output of the skip connection with the upsampled output of the lower decoder stage. This is mathematically expressed as:

where

is the output from the lower decoder stage, and

ensures spatial alignment.

Once the decoder input is established, it undergoes a series of transposed convolutions and linear operations to reconstruct the spatial resolution while reducing the channel dimensions:

where

represents the reduced channel dimension at stage

k. This transposed convolution operation progressively upsamples the feature maps and diminishes the number of channels, effectively restoring spatial resolution while preserving essential details for accurate segmentation.

In the final stage of the decoder, a single-channel segmentation mask is produced through a transposed convolution followed by a sigmoid activation function:

where

denotes the sigmoid activation function, ensuring that the output values are scaled between 0 and 1, suitable for binary segmentation tasks.

This structured use of skip connections and decoder operations ensures the seamless integration of multi-level features, enabling accurate smoke segmentation with fine spatial detail.

3.3. Loss Function

For training, we use a combined loss function that includes a binary cross-entropy (BCE) component and a Dice loss component, formulated to optimize segmentation accuracy by balancing region overlap and boundary alignment:

where

y is the ground truth,

is the predicted mask, and

and

are weights assigned to each loss component to balance their contributions.

We further implement a cosine annealing learning rate schedule to modulate the learning rate during training, aiming to facilitate smoother convergence. The learning rate

at epoch

t is given by:

where

and

are the minimum and maximum learning rates, respectively, and

T is the total number of epochs. For our model, we set

,

, and

epochs.

With the loss function, we incorporate layer-wise loss functions that combine the overall loss at different layers. Since the layer loss is the combined loss at different layers, we assigned different weights to each layer’s loss to balance their contributions. The layer-wise loss is defined as:

where

represents the combined loss at layer

i, and

is the weight assigned to layer

i. For the layer-wise loss, different weights were assigned to each layer to balance their contributions, with the values assigned as follows: Stage 2 to 6 has decreasing weights of

,

,

,

,

.

4. Experiments

The experiments aim to comprehensively evaluate SmokeNet’s effectiveness in accurately segmenting smoke in complex scenarios, comparing its performance against established models across diverse datasets, and assessing the balance it strikes between computational efficiency and segmentation accuracy.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Deep Learning Architecture

SmokeNet was implemented using the PyTorch framework and trained on a single NVIDIA Tesla P40 24GB GPU. The model consists of six encoder and decoder layers with filter sizes . Training was conducted using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, a weight decay of , and a cosine annealing learning rate schedule (, iterations). The model was trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 8, using a combined loss of cross-entropy and dice loss with layer-wise losses as the loss function.

4.1.2. Dataset

Four datasets selected to encompass both synthetic and real-world smoke variations, testing its robustness and adaptability across diverse conditions:

Smoke100k-M [

24]: A synthetic dataset comprising 25,000 training images and 15,000 test images, as illustrated in

Figure 4 (a). It features centrally located smoke plumes of fixed size, providing a baseline for accuracy assessment in controlled conditions.

DS01 [

9]: This dataset comprises 70,632 training images and 1,000 test images, featuring various smoke sizes and locations, as illustrated in

Figure 4 (b). It challenges the model’s ability to adapt to different spatial configurations, enhancing its generalization capabilities.

Fire Smoke [

25]: A real-world dataset with 3,826 images, including 3,060 training images and 766 test images, as illustrated in

Figure 4 (c). It captures both outdoor wildfire smoke and indoor smoke scenarios, providing realistic environments where smoke detection is critical for early fire warning and safety monitoring.

Quarry Smoke: An industrial dataset comprising 3,703 images, including 2,962 training images and 741 test images, as illustrated in

Figures 4 (d), (e), and (f). It represents dense, irregular smoke plumes mixed with dust and debris from quarry blasts, testing the model’s ability to segment smoke in dynamic and high-variability environments.

4.1.3. Quarry Smoke Dataset Collection

The Quarry Smoke dataset was systematically collected at quarry sites during blasting operations, capturing diverse blast scenarios using multiple camera devices to accommodate varying site conditions. Cameras with different resolutions and frame rates were mounted on stable tripods, positioned appropriately based on site-specific requirements. Data collection occurred under various environmental and site conditions, including diverse weather scenarios (clear skies, cloudy weather, occasional rainfall) and quarry-specific characteristics such as rock types, bench face structures, dust levels, rock wall conditions, and blast-induced fragmentation patterns. All data collection procedures were conducted with appropriate authorization, strictly adhering to relevant ethical guidelines and industry-standard safety regulations.

Annotations were performed using custom annotation tools specifically developed for this project to generate precise binary segmentation masks for smoke regions. The annotation team consisted of professional experts experienced in blast design, explosive loading practices, and quarry operations. Cross-validation was systematically conducted among annotators to ensure annotation consistency, quality, and reliability, reflecting meticulous and precise labeling processes.

4.1.4. Data Augmentation

To enhance SmokeNet’s robustness and generalization capabilities, we employed a comprehensive data augmentation pipeline that includes both basic and enhanced augmentation techniques.

Basic augmentations, including random horizontal and vertical flips, rotations, and brightness adjustments, were applied uniformly across all datasets to introduce general variability and prevent overfitting. In addition to these common techniques, we implemented enhanced augmentations—synthetic fog and motion blur—to address domain-specific challenges in our datasets.

Synthetic fog better simulates real-world scenarios, such as blast events occurring under overcast skies, rainy showers, and high humidity in mountainous regions. Motion blur is particularly relevant in real-world situations like quarry sites, where hand-held cameras or ground cameras mounted on tripods may experience distortions due to ground vibrations caused by explosive energy.

These enhanced augmentations were crucial in enabling SmokeNet to generalize effectively across both synthetic and real-world conditions, leading to significant improvements in smoke segmentation performance.

4.1.5. Performance Metrics

SmokeNet’s performance was evaluated using four metrics:

Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU): Assesses segmentation accuracy by quantifying the overlap between predicted and ground-truth masks.

Parameter Count: Indicates model scalability and resource usage. Reported in millions (M) or thousands (K), with units specified in each table.

Floating Point Operations (FLOPs): Measures computational complexity. Reported in gigaflops (GFLOPs), as indicated in the tables.

Frames per Second (FPS): Reflects inference speed, critical for computationally constrained applications in dynamic environments like quarry blast monitoring.

4.2. Results and Discussion

4.2.1. Results

As shown in

Table 1, we evaluated different configurations of our model, investigating the contributions of multiscale convolution, multiview attention, and layer-specific loss functions. Each configuration was trained and evaluated on fixed, predefined training and testing splits of the datasets, with five independent runs conducted for each. The reported results include the mean and standard deviation, demonstrating the stability and effectiveness of these design choices.

In

Table 2, we compared the best-performing configuration of our model with several state-of-the-art segmentation methods. For each method, the same experimental protocol was applied, ensuring consistency in training and evaluation across the standardized dataset splits and five repetitions. This provides a rigorous and fair comparison, reflecting both segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency.

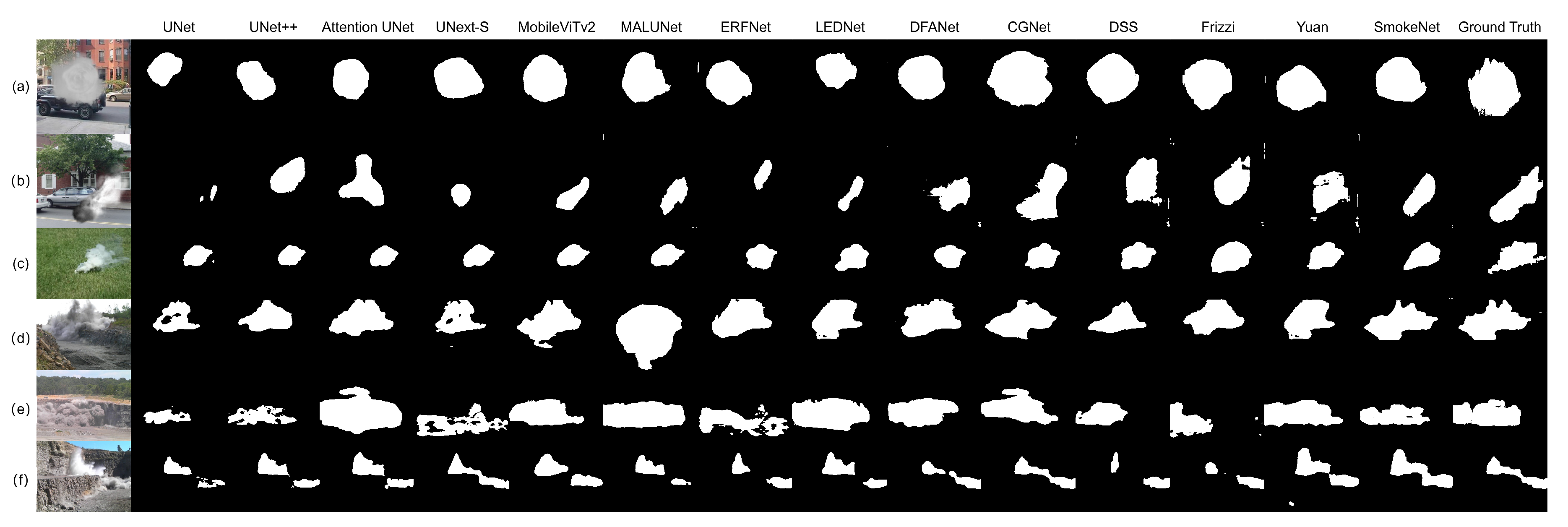

Figure 4 illustrates qualitative segmentation results across diverse datasets, including synthetic smoke with uniform, circular patterns; real-world fire smoke with irregular and amorphous structures; and quarry blast smoke characterized by dense, complex plumes. These visualizations offer insights into the strengths and limitations of our model in handling varied smoke characteristics, showcasing its adaptability across synthetic and real-world scenarios.

4.2.2. Impact of Architectural Innovations

A module evaluation study was conducted to assess the contribution of SmokeNet’s multiscale convolutional layers and multiview linear attention mechanisms to its segmentation performance and computational efficiency across four datasets: Smoke100k, DS01, Fire Smoke, and Quarry Smoke. Various model configurations were systematically compared, as detailed in

Table 1. Models incorporating multiscale convolutions consistently outperformed those using normal convolutions; specifically, the full SmokeNet model achieved an mIoU of 76.45% on Smoke100k compared to 72.40% for the baseline configuration. Furthermore, integrating the multiview linear attention mechanism significantly improved performance. Models including

+ MultiviewAttn,

+ MultiviewAttn + LayerLoss,

+ Multiscale + MultiviewAttn, and the

Full Model (SmokeNet) consistently showed higher mIoU scores. Notably, the

Full Model (SmokeNet) achieved the highest mIoU of 72.74% on the Quarry Smoke dataset. Additionally, incorporating layer-specific loss functions (configurations labeled

+ LayerLoss,

+ MultiviewAttn + LayerLoss,

+ Multiscale + LayerLoss, and the

Full Model (SmokeNet)) consistently enhanced accuracy. Overall, the optimal configuration, which combines multiscale convolutions, multiview linear attention, and layer-specific losses (

Full Model - SmokeNet), demonstrated significant performance improvements while maintaining efficient computational demands (0.34M parameters, 0.07 GFLOPs) and high inference speed (77.05 FPS). This result validates SmokeNet’s architectural innovations in effectively capturing complex smoke features within dynamic environments.

4.2.3. Segmentation Performance Comparison

As shown in

Table 2, SmokeNet demonstrates consistently high performance across multiple datasets. On the Smoke100k dataset, it achieves the highest mIoU of 76.45%, outperforming CGNet (75.64%) and Yuan (75.57%), while significantly surpassing other models such as UNeXt-S (72.25%) and MobileViTv2 (71.73%). On the Fire Smoke dataset, SmokeNet attains an mIoU of 73.43%, exceeding CGNet’s 72.04% and MobileViTv2’s 70.23%, and outperforming other models like Frizzi (70.51%) and Yuan (71.94%). Similarly, in the Quarry Smoke dataset, SmokeNet achieves an mIoU of 72.74%, surpassing CGNet (71.91%), Yuan (70.92%), and Frizzi (70.40%). However, on the DS01 dataset, SmokeNet achieves an mIoU of 74.43%, slightly below Yuan’s 74.84%. Despite this, it maintains competitiveness by outperforming models such as CGNet (73.76%), Frizzi (71.67%), and UNeXt-S (71.62%). Overall, SmokeNet demonstrates robustness and generalizability. It consistently improves over lightweight models such as MALUNet (70.16%) and LEDNet (71.63%), while also surpassing computationally heavier models like AttentionUNet (66.59%) and DSS (72.17%) across most datasets.

In

Figure 4, SmokeNet exhibits its ability to accurately delineate complex smoke boundaries, capture fine-grained details, and maintain consistent segmentation across various smoke scenarios, including challenging quarry smoke environments. Traditional models like UNet and UNet++ produce simplified masks that miss intricate contours and fragmented structures. Smoke segmentation-specific models such as DSS, Frizzi, and Yuan also generate less precise masks compared to SmokeNet. Lightweight models such as UNeXt-S and MobileViTv2 often overlook subtle edges and fine details. For the quarry smoke case application, which is commonly used for pollutant quantification inside the smoke plume, slightly thicker masks than the ground truth are acceptable compared to missing parts, which could potentially omit noxious chemicals of the smoke, as shown in

Figure 4 (d), (e), and (f). In contrast, SmokeNet consistently generates segmentation masks closely aligned with the ground truth, effectively capturing irregular shapes, narrow projections, and diffused edges.

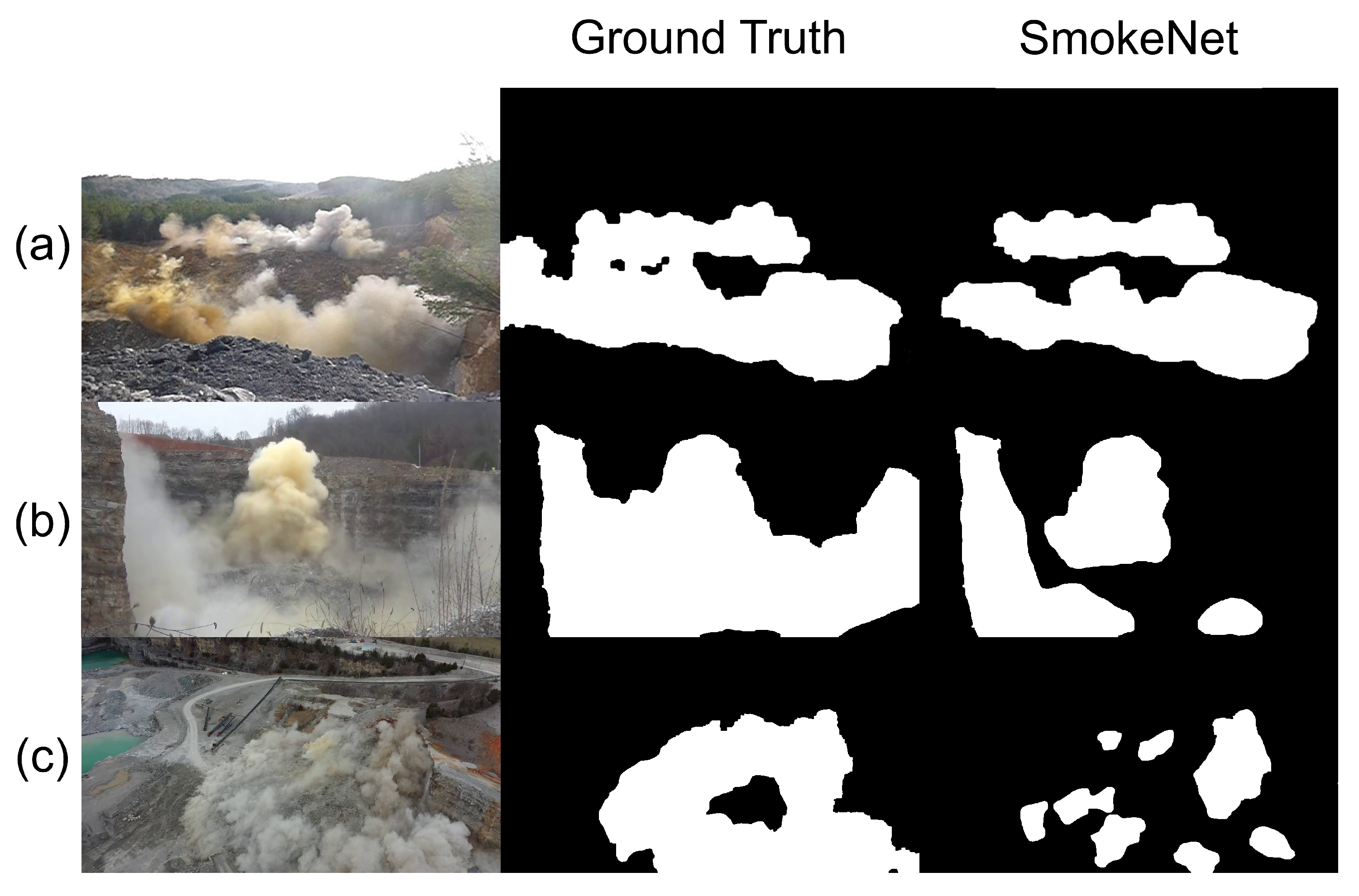

Figure 5 highlights the performance of SmokeNet across different challenging scenarios where SmokeNet does not effectively segment the entire smoke in these images. In

Figure 5(a), the image contains two horizontal clusters of smoke, with most of them being white and gray under bright sunlight. However, for the orange part on the left side of the bottom smoke cluster, SmokeNet recognizes the dark orange portion of the smoke but misses the faint, translucent orange smoke, which is less observable, especially against the orange soil background, due to the gradual transitions between smoke and background. In

Figure 5(b), the ground camera provides a closer view of the smoke plume at ground level. The complexity of the background textures and the irregularity of the smoke shapes make it difficult for SmokeNet to accurately delineate the two-part smoke composition: the yellowish smoke directly emanating from the collapsed rocks during the blast, and the white smoke surrounding it, which falls to the lower ground level first and then disperses around. Additionally, the presence of dry twigs in front of the smoke further confuses the model in recognizing the entire shape of the smoke, especially when combined with the faint smoke in the center and the rocks observed behind. In

Figure 5(c), the smoke image is captured from a drone-mounted camera, which covers the overall view of the smoke plume spread across the entire quarry site. SmokeNet can recognize the smoke near the blast spot and the rock wall but cannot accurately recognize the dispersed smaller grouped smoke clusters due to the low visibility of sparse smoke regions and the intricate gray background surface textures.

Despite these challenges requiring further improvement, the overall quantitative and qualitative analysis demonstrates that SmokeNet performs better than established models in segmentation performance across various datasets. The higher mIoU scores and consistent qualitative results highlight SmokeNet’s effectiveness in accurately segmenting smoke under diverse conditions.

4.2.4. Model Efficiency Comparison

Table 2 provides a comprehensive comparison of various semantic segmentation methods based on number of parameters (#Params), computational complexity (GFLOPs), and inference speed (FPS), while also considering their segmentation performance (mIoU).

SmokeNet demonstrates exceptional efficiency with only 0.34M parameters and the lowest computational complexity of 0.07 GFLOPs, achieving an inference speed of 77.05 FPS. This makes SmokeNet one of the most lightweight and computationally efficient models among the compared methods. Additionally, SmokeNet maintains competitive mIoU scores, outperforming other models on Smoke100k, Fire Smoke, and Quarry Smoke datasets.

Traditional models like UNet and UNet++ have significantly higher parameter counts (28.24M and 9.16M, respectively) and GFLOPs (35.24 and 10.72), which result in heavy workloads for GPU memory and computing usage. AttentionUNet offers slightly improved mIoU scores but at the cost of increased parameters (31.55M) and GFLOPs (37.83 GFLOPs), leading to a slower inference speed of 46.48 FPS. Models such as ERFNet and DFANet have lower parameter counts (2.06M and 2.18M, respectively) compared to UNet and UNet++. However, they still exhibit relatively high GFLOPs (3.32 and 0.44 GFLOPs) and lower FPS (61.22 and 31.05). Thus, they impose significant computational demands compared to other lightweight models.

Advanced models such as UNeXt-S and MobileViTv2 achieve higher inference speeds of 202.06 FPS and 98.84 FPS with 0.77M and 2.30M parameters, and 0.08 GFLOPs and 0.09 GFLOPs, respectively. However, their mIoU scores are generally lower than those of SmokeNet.

Among parameter-efficient models, MALUNet is the most lightweight with only 0.17M parameters and 0.09 GFLOPs, while CGNet and LEDNet offer a balance between low parameter counts (0.49M and 0.91M) and reasonable GFLOPs (0.86 and 1.41). Nonetheless, SmokeNet outperforms these models in terms of computational efficiency and maintains competitive inference speeds.

Models specifically designed for smoke segmentation, like DSS and Frizzi, require significantly higher computational resources. DSS and Frizzi demand 184.90 GFLOPs and 27.90 GFLOPs respectively, leading to slower inference speeds of 32.56 FPS and 60.32 FPS. While achieving respectable mIoU scores, their computational demands are considerably higher compared to SmokeNet. Yuan achieves competitive mIoU scores with 0.88M parameters and 1.15 GFLOPs, but SmokeNet generally offers a better efficiency-performance balance across most datasets, except for the DS01 dataset where Yuan achieves the highest mIoU. Overall, SmokeNet provides the best trade-off between computational demand and segmentation performance, making it highly suitable for real-time smoke segmentation tasks.

5. Conclusion

This study introduces SmokeNet, an efficient and robust model for smoke plume segmentation across diverse scenarios, including quarry blast smoke. By integrating multiscale convolutions and multiview linear attention within a lightweight framework, SmokeNet effectively handles dynamic smoke plumes with varying opacity and shape. Experimental results demonstrate high segmentation accuracy on both synthetic and real-world datasets, such as campfire, wildfire, and quarry blast smoke. Its low parameter count, reduced computational demands, and high inference speed make it suitable for applications in environmental monitoring and industrial safety.

However, the failure case study highlighted limitations in identifying sparse smoke regions against complex backgrounds and managing irregular smoke shapes and low visibility areas. Addressing these challenges will involve enhancing feature extraction techniques, improving background differentiation, utilizing augmented and synthetic datasets for greater robustness, and optimizing SmokeNet’s architecture for real-time processing. Exploring dynamic kernel shapes may also improve generalizability for irregular objects like smoke plumes. Overall, SmokeNet offers a balanced trade-off between performance and computational efficiency, making it a valuable tool for real-time smoke detection and monitoring in various applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xuesong Liu, and Emmett J. Ientilucci; methodology, Xuesong Liu; validation, Xuesong Liu; formal analysis, Xuesong Liu; investigation, Xuesong Liu; resources, Emmett J. Ientilucci; data curation, Xuesong Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Xuesong Liu; writing—review and editing, Xuesong Liu, and Emmett J. Ientilucci; visualization, Xuesong Liu; supervision, Emmett J. Ientilucci; project administration, Emmett J. Ientilucci; funding acquisition, Emmett J. Ientilucci. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Austin Powder through a contractual agreement.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the findings of this study was provided by Austin Powder. Due to contractual and confidentiality restrictions, the data are not publicly available; however, they can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Austin Powder. We gratefully acknowledge Austin Powder for providing the essential dataset that enabled the development and evaluation of our approach.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9 2015; proceedings, part III 18. . Springer, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2015, pp. 3431–3440.

- Howard, A.G. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet: An Extremely Efficient Convolutional Neural Network for Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 6848–6856.

- Dosovitskiy, A. An Image Is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, F.; Zhang, L.; Xia, X.; Wan, B.; Huang, Q.; Li, X. Deep Smoke Segmentation. Neurocomputing 2019, 357, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frizzi, S.; Bouchouicha, M.; Ginoux, J.M.; Moreau, E.; Sayadi, M. Convolutional Neural Network for Smoke and Fire Semantic Segmentation. IET Image Processing 2021, 15, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Fang, Z. A Lightweight Network for Smoke Semantic Segmentation. Pattern Recognition 2023, 137, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Rui, X.; Chen, Y.; Fan, X. Flame and Smoke Semantic Dataset: Indoor Fire Detection with Deep Semantic Segmentation Model. Electronics 2023, 12, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, F.; Qin, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, X.; Meng, F. An Optimized Smoke Segmentation Method for Forest and Grassland Fire Based on the UNet Framework. Fire 2024, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, T.; Bernardino, A.; Cruz, G. Fire and Smoke Segmentation Using Active Learning Methods. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, L.; Sun, Y.; Wan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Brightness Perceiving for Recursive Low-Light Image Enhancement. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence 2025. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Lightweight Adaptive Feature De-drifting for Compressed Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia 2024. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support: 4th International Workshop, DLMIA 2018, and 8th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2018, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2018, Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; Proceedings 4. Springer, 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Romera, E.; Alvarez, J.M.; Bergasa, L.M.; Arroyo, R. ERFNet: Efficient Residual Factorized Convnet for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2017, 19, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiong, P.; Fan, H.; Sun, J. DFANet: Deep Feature Aggregation for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019, pp. 9522–9531.

- Oktay, O. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Tang, S.; Zhang, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y. CGNet: A Light-weight Context Guided Network for Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2020, 30, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.; Rastegari, M. Separable Self-Attention for Mobile Vision Transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.02680. [Google Scholar]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Patel, V.M. UNeXt: MLP-based Rapid Medical Image Segmentation Network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2022; pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Xiang, S.; Xie, M.; Liu, T.; Fu, Y. MALUNet: A Multi-Attention and Light-weight UNet for Skin Lesion Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); IEEE, 2022; pp. 1150–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Xiong, J.; Gao, G.; Wu, X.; Latecki, L.J. LEDNet: A Lightweight Encoder-Decoder Network for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); IEEE, 2019; pp. 1860–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.Y.; Yin, J.L.; Chen, B.H.; Yu, Z.M. Smoke 100k: A Database for Smoke Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE); IEEE, 2019; pp. 596–597. [Google Scholar]

- Kaabi, R.; Bouchouicha, M.; Mouelhi, A.; Sayadi, M.; Moreau, E. An Efficient Smoke Detection Algorithm Based on Deep Belief Network Classifier using Energy and Intensity Features. Electronics 2020, 9, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).