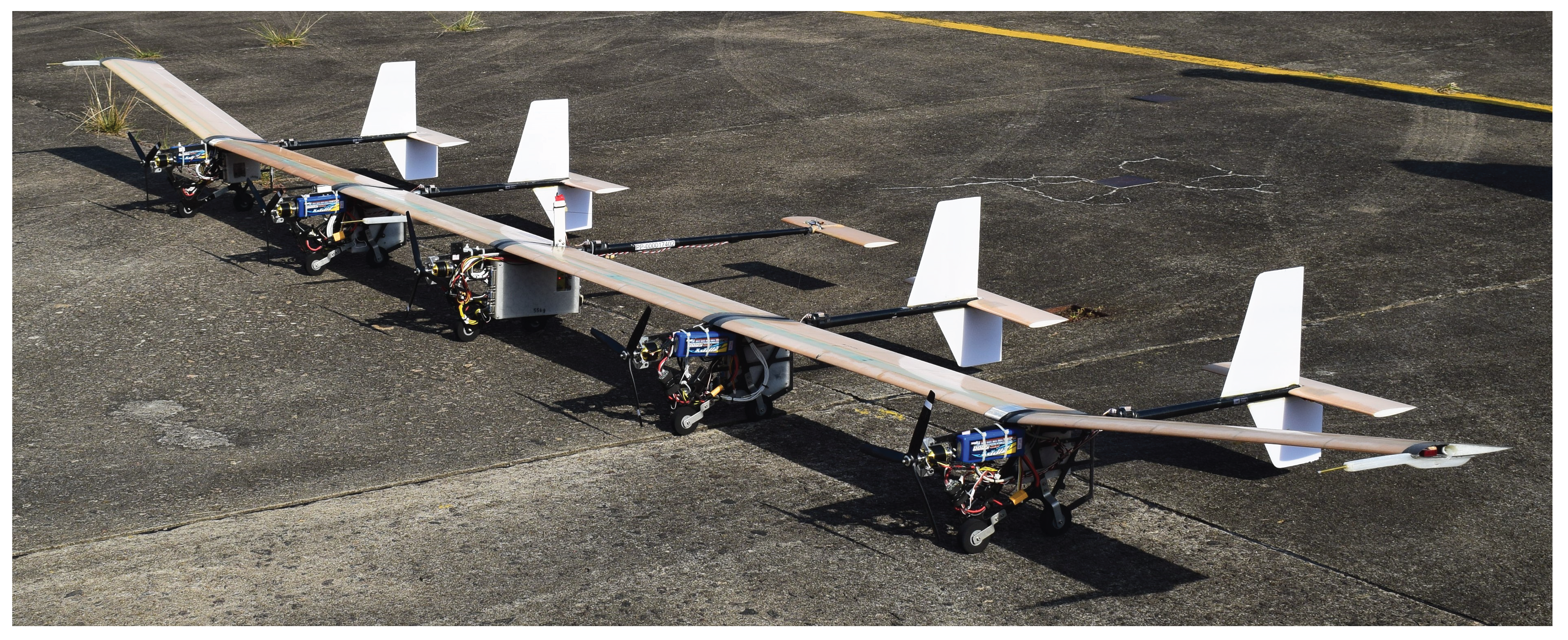

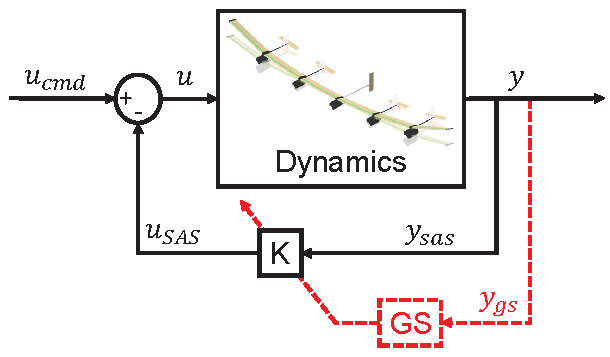

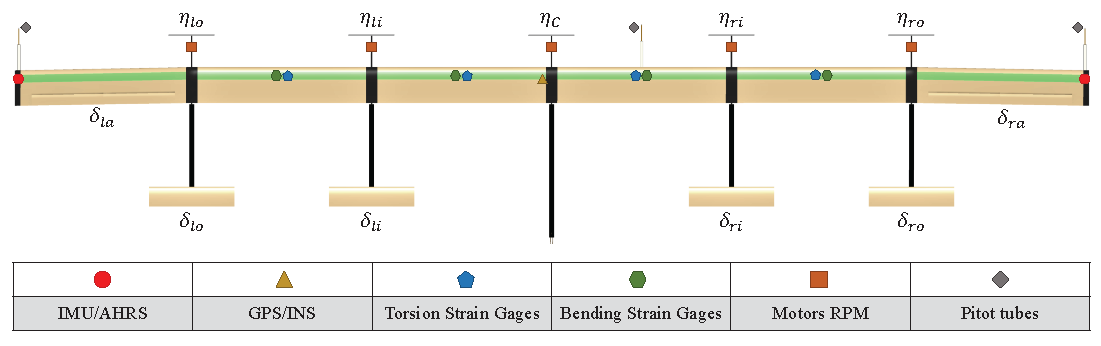

To illustrate the proposed method, the approach detailed in

Section 2 was implemented on the six-meter-span ITA X-HALE model. However, its reduced version presented in

Section 3.2 was used, primarily due to computational constraints associated with model order. The control inputs from Eq.

39 and outputs from Eq.

41 were selected. For SAS design, the altitude state has been disregarded. Therefore, the linear model employed in the SAS design is represented by:

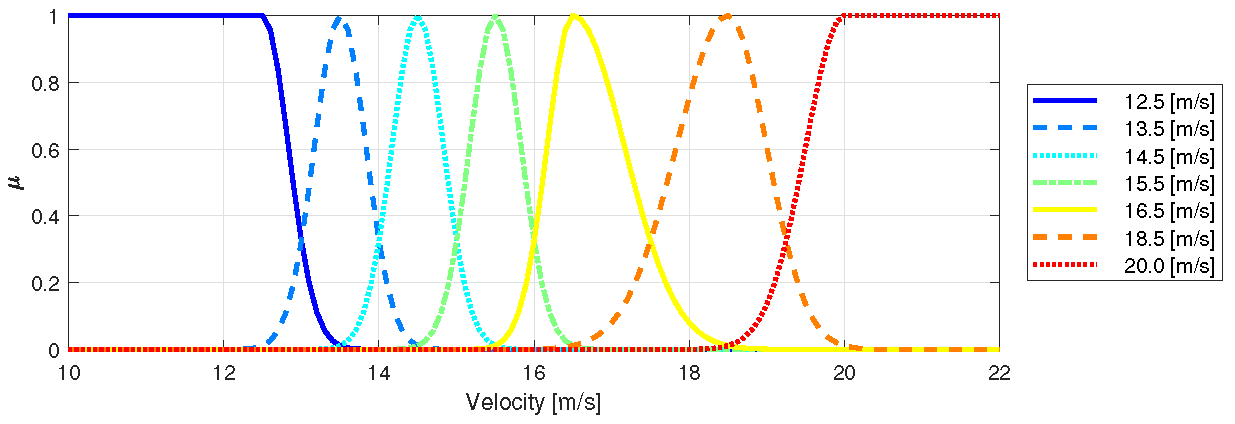

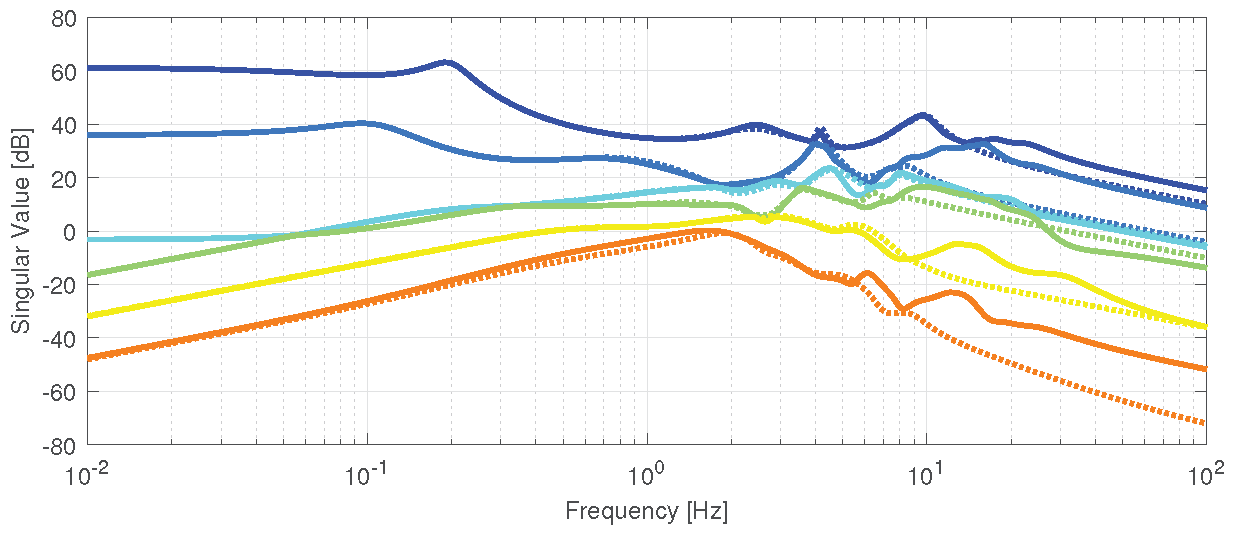

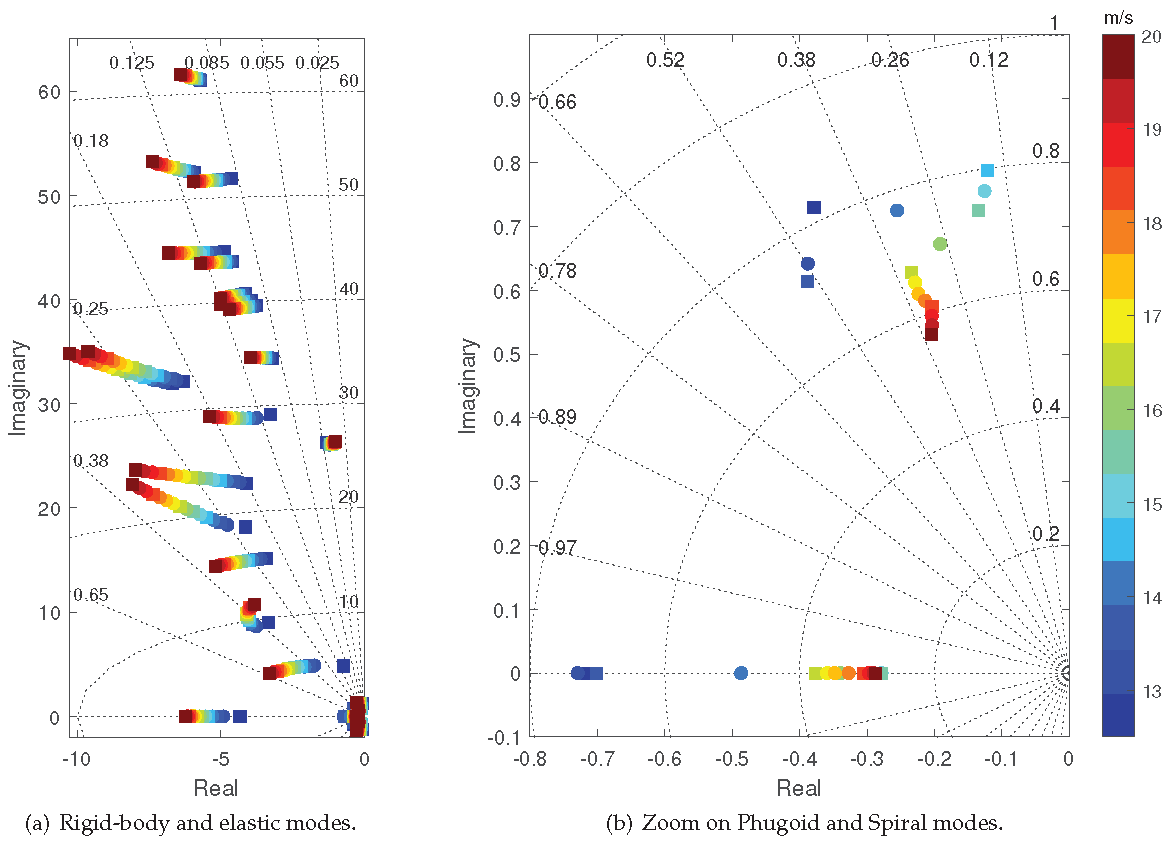

The selection of design points was guided by the behavior of the poles. It is evident that the majority of poles exhibit satisfactory behavior concerning variations in velocity, as shown in

Figure 7. However, the phugoid and spiral modes demonstrate less linear behavior, due to the nonlinearities present in the propulsive model that was based on wind-tunnel data, as presented by Guimaraes Neto et al. [

22]. To obtain a reliable representation of these modes, velocities of

,

,

,

,

,

, and

m/s were chosen, consistent with those depicted in the membership functions of

Figure 3. Other methods for selecting design points, such as the one proposed by Al-Jiboory et al. [

38], exist but are not within the scope of analysis for this study.

4.1. Stability Analysis

The new design variable

is incorporated into the second step outlined in

Section 2.5. To assess its impact on stability enhancement, a range of

values, spanning from

to

, was systematically applied to the LMI set.

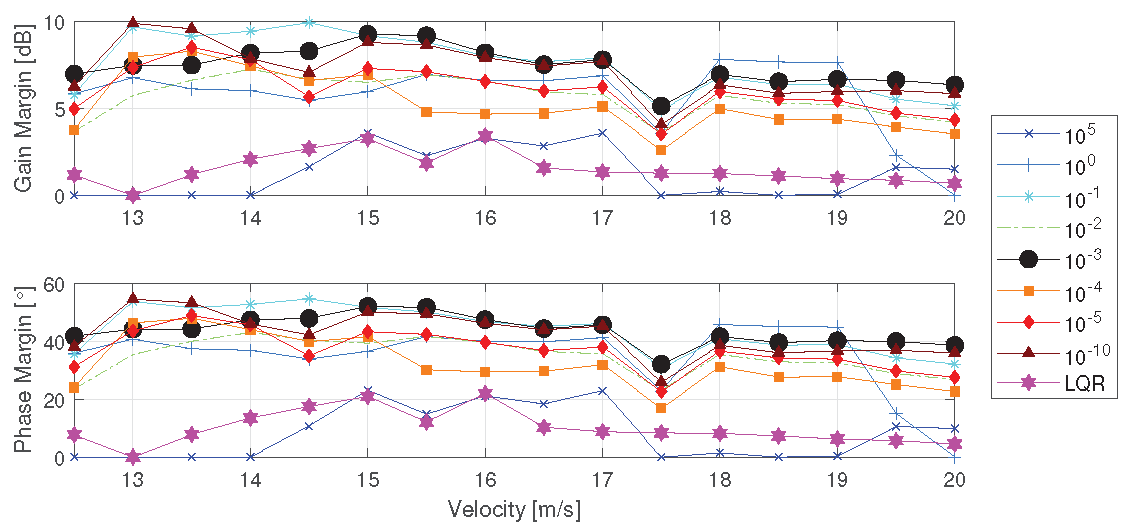

Following the application of LMI on top of the LQR design, the disk margin performance between LQR and LMI for different values of

is compared, calculated according to Lavretsky and Wise [

40]. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the LQR design leads to instability at

m/s, exhibiting an overall poor margin with the entire range below

dB. Conversely, the methodology proposed for gain design reveals that higher values of

fail to stabilize the entire range, and with the highest value, the margins are even worse than the pure LQR design. However, as the value of

decreases, stability margins substantially increase, with the best result achieved when

is equal to

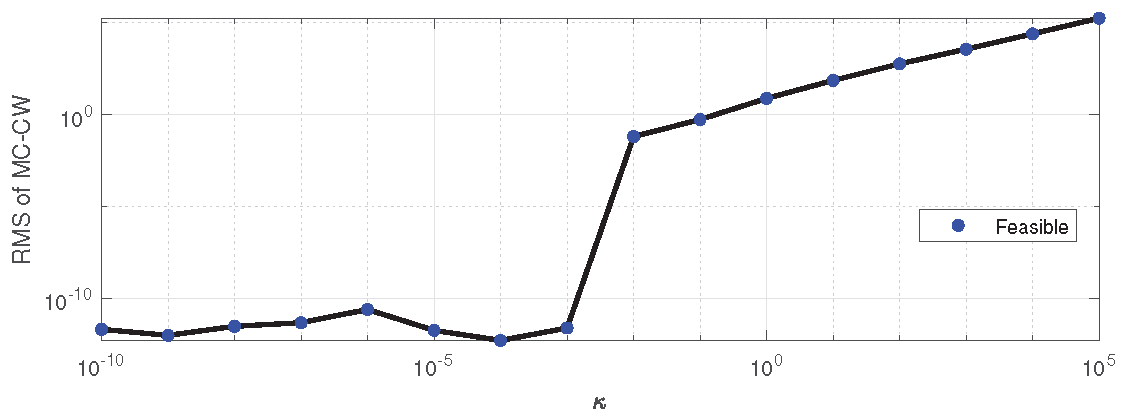

. Examining the sum of the Root Mean Square (RMS) values of the approximation described in Eq.

30, presented in

Figure 9, it is evident that for this value, the approximation converges close to zero and achieves an almost steady value for smaller

values. All solutions where the RMS value was smaller than 1 achieved good stability margins, indicating that once the approximation is sufficiently accurate, stability margins increase and the global stability is assured. However, it is essential to note that this

value is problem-specific.

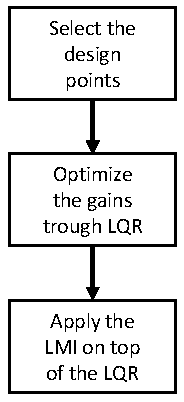

4.2. Nonlinear Simulations

After the stability study, simulations focusing on performance degradation analysis at different points used in the design were evaluated. These nonlinear simulations also aim to show the system performance improvement at intermediate velocities where the LMI described in Eq.

33 is considered in the controller design.

The simulations were performed with three different control configurations: open loop, closed loop considering the gain calculated through LQR only, and gains calculated using the methodology outlined in the flowchart

Figure 4, which combines LQR and LMI with

, referred to simply as FGS.

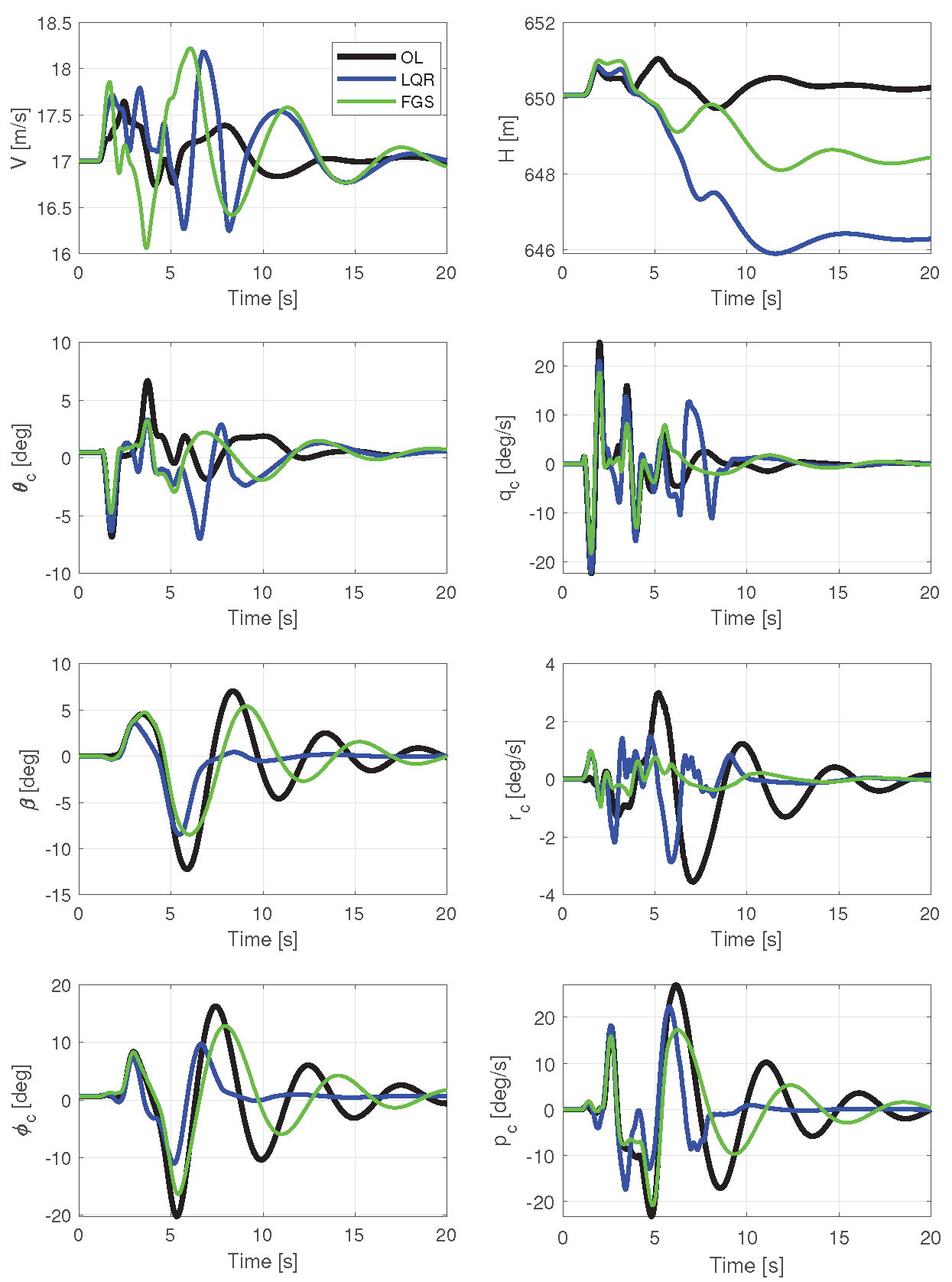

To assess a scenario where the system experiences disturbance around an equilibrium point, simulations were conducted with vertical and horizontal gusts featuring a one-minus-cosine profile during straight-level flight at

m/s. Figs.

Figure 10 to

Figure 13 illustrate the results of a simulation in which the aircraft is perturbed by two lateral and two vertical gusts. These gusts have a maximum amplitude of 3 m/s and are fixed in space, with vertical gusts occurring from 17 to 34 m and 51 to 68 m, and horizontal gusts from 34 to 51 m and 68 to 95 m.

Figure 10 presents rigid body outputs. Gains calculated using only LQR demonstrate commendable performance, particularly in the context of lateral-directional motion, exhibiting high attenuation for both

and

. The controller that combines both techniques exhibits the best results for longitudinal motion, displaying smaller variations in

and

. This superior performance is further evident in the RMS values in

Table 1. However, velocity and altitude have deteriorated due to the increased control energy used in all motors, as indicated by the RMS values in

Table 2.

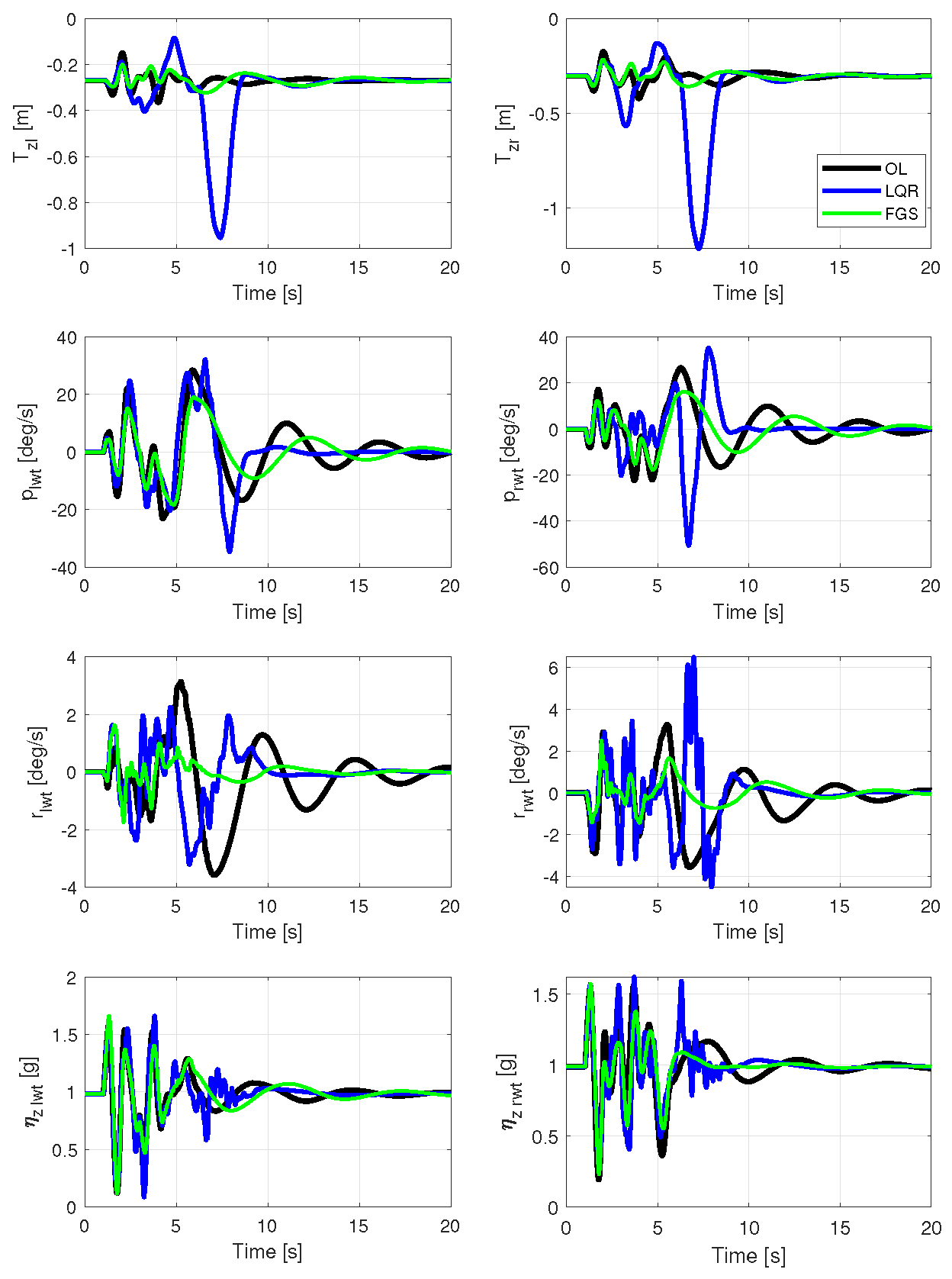

Now, examining the wingtip outputs in

Figure 11, it is evident that the gain calculated by the LMI was able to yield the smallest wingtip displacement (

), consequently resulting in the lowest RMS value, as shown in

Table 3. The results for

, both left and right, exhibit the most significant attenuation in the FGS design and are associated with wing in-plane motion. Conversely, the LQR-only design resulted in substantial wing displacements and, notably, the poorest outcome for the rates.

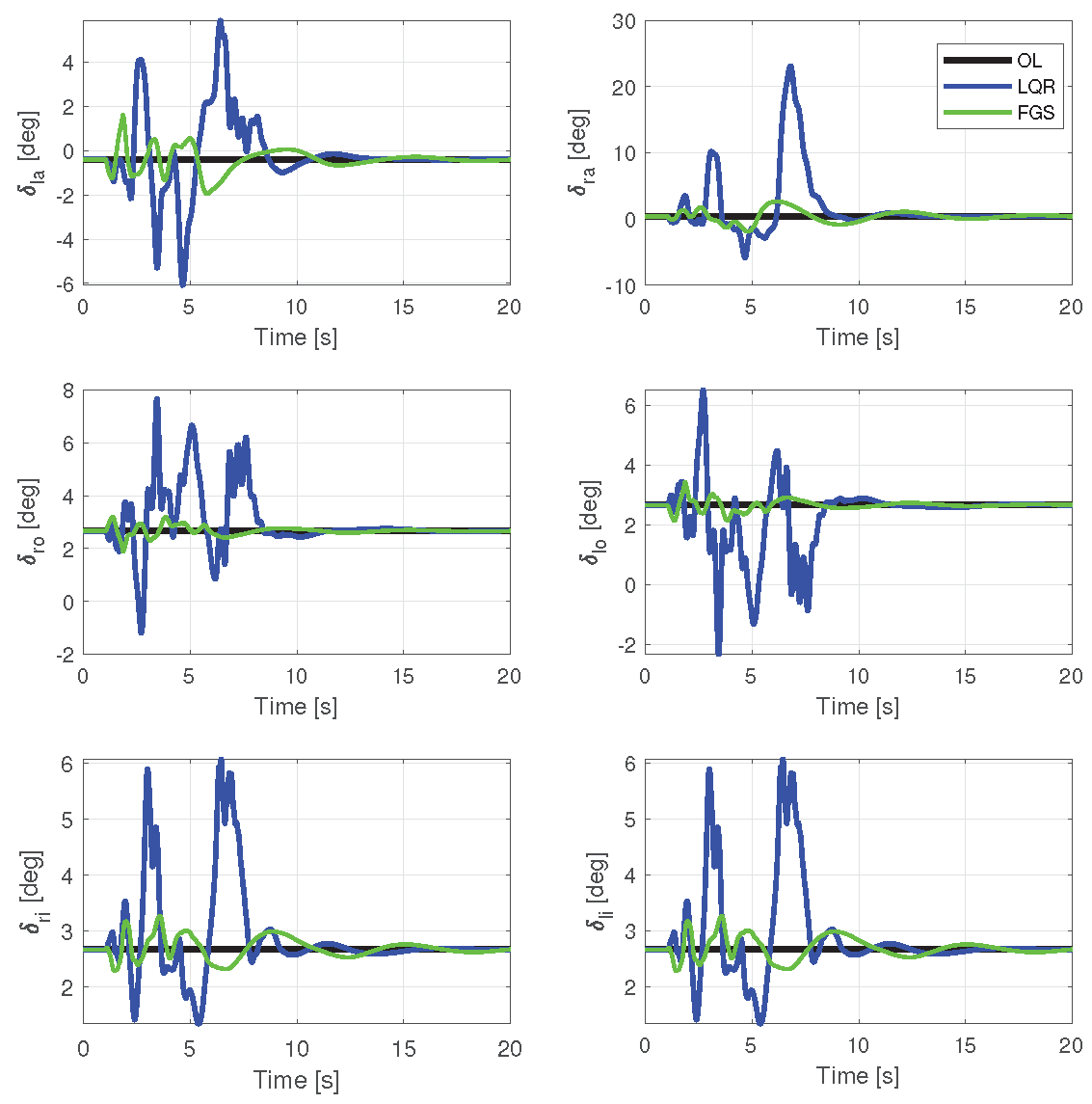

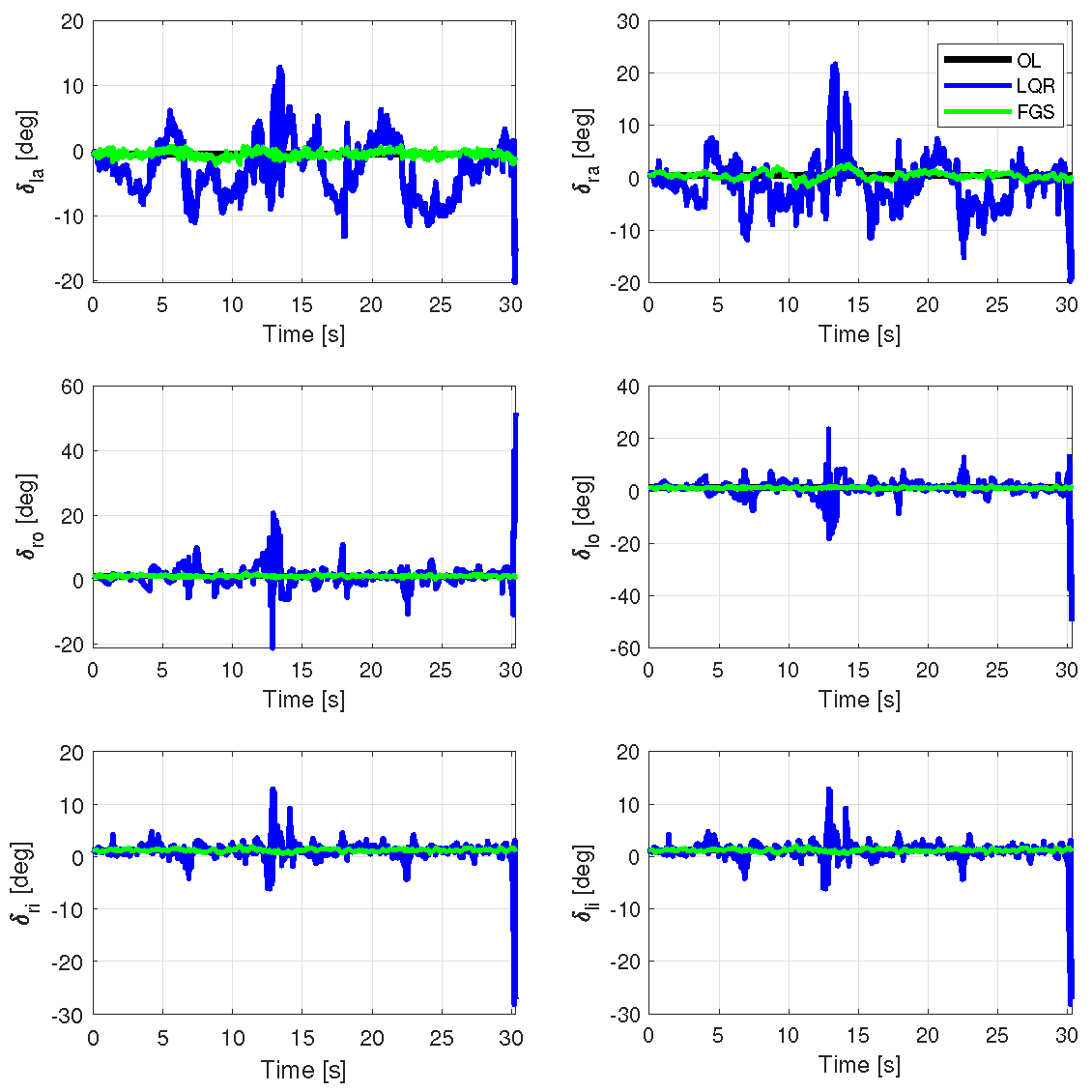

Concerning control energy, as depicted in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, and highlighted in

Table 2, the gains calculated with FGS exhibited superior performance, utilizing less control effort compared to the LQR. This is evident for both control surfaces and motors.

Table 2 illustrates the RMS values. Although the physical limits were exceeded by the motors, the FGS design performed better in this regard.

Figure 12.

Control surfaces for a velocity of 17.0 m/s, subjected to vertical and horizontal wind gusts, with two different output feedback realizations and open loop.

Figure 12.

Control surfaces for a velocity of 17.0 m/s, subjected to vertical and horizontal wind gusts, with two different output feedback realizations and open loop.

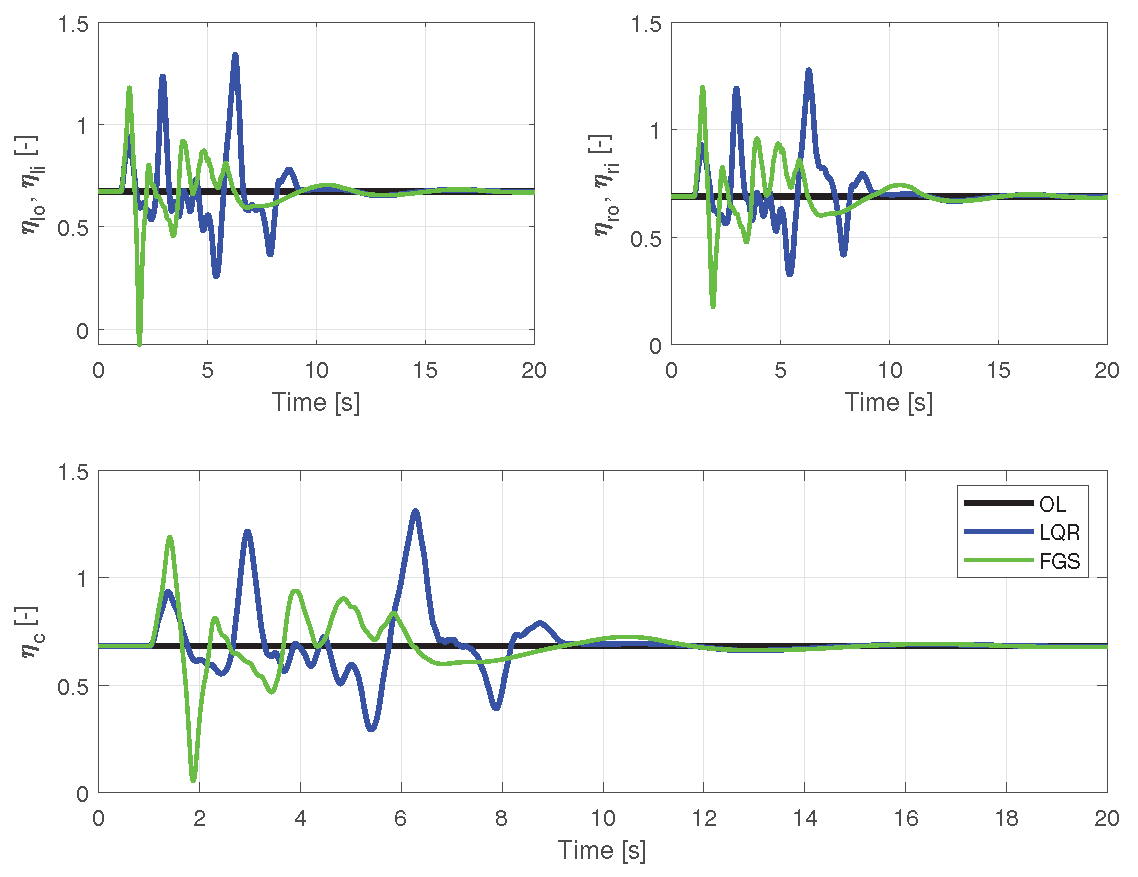

Figure 13.

Motor entries for a velocity of 17.0 m/s, subjected to vertical and horizontal wind gusts, with two different output feedback realizations and open loop.

Figure 13.

Motor entries for a velocity of 17.0 m/s, subjected to vertical and horizontal wind gusts, with two different output feedback realizations and open loop.

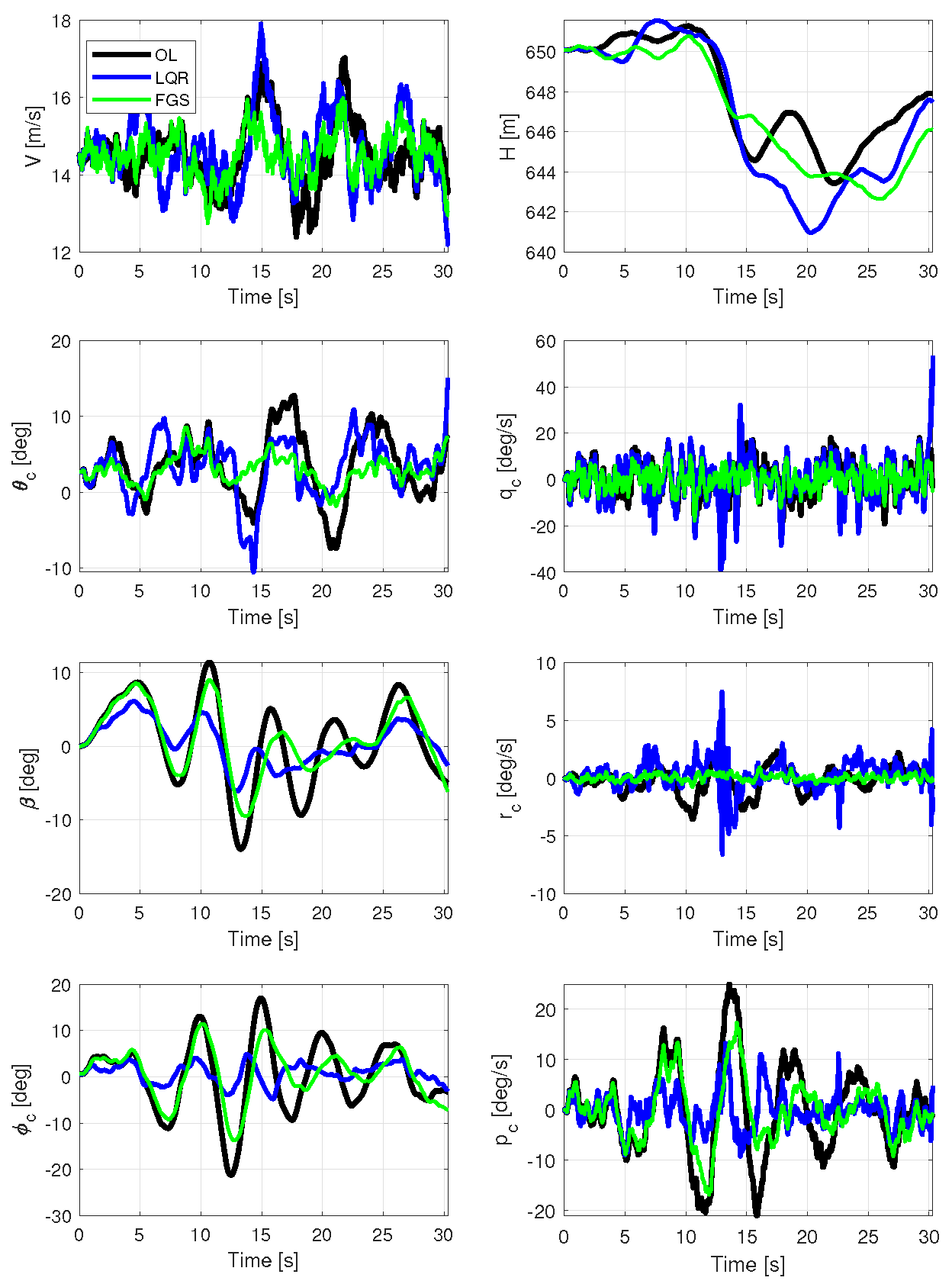

Finally, the controller’s performance was analyzed when the aircraft was exposed to a von Kármán wind turbulence as an external disturbance. Results in the same manner as the results shown above are presented in Figs.

Figure 14 to

Figure 17.

The rigid body results in

Figure 14 exhibit a similar pattern in terms of attenuations, with the LQR showing a superior response in lateral-directional motion and the FGS outperforming in longitudinal motion. Notably, instabilities are observed in

for the LQR design, particularly as the phugoid mode is degenerate and couples with the spiral mode, leading to instability at a flight velocity of

m/s. Consequently, whenever the aircraft traverses this unstable region, the LQR design exhibits an inappropriate response, causing the simulation to crash after 30 s. In the other two instances when the aircraft passes through the unstable region, the aircraft recovers because the turbulence itself increases the aircraft’s velocity.

Examining both

Figure 14 and

Table 4, it is evident that the highest attenuation was achieved by the controller designed with LQR for lateral motion. However, the FGS design can ensure stability at intermediary points while still offering some improvement over the open-loop response.

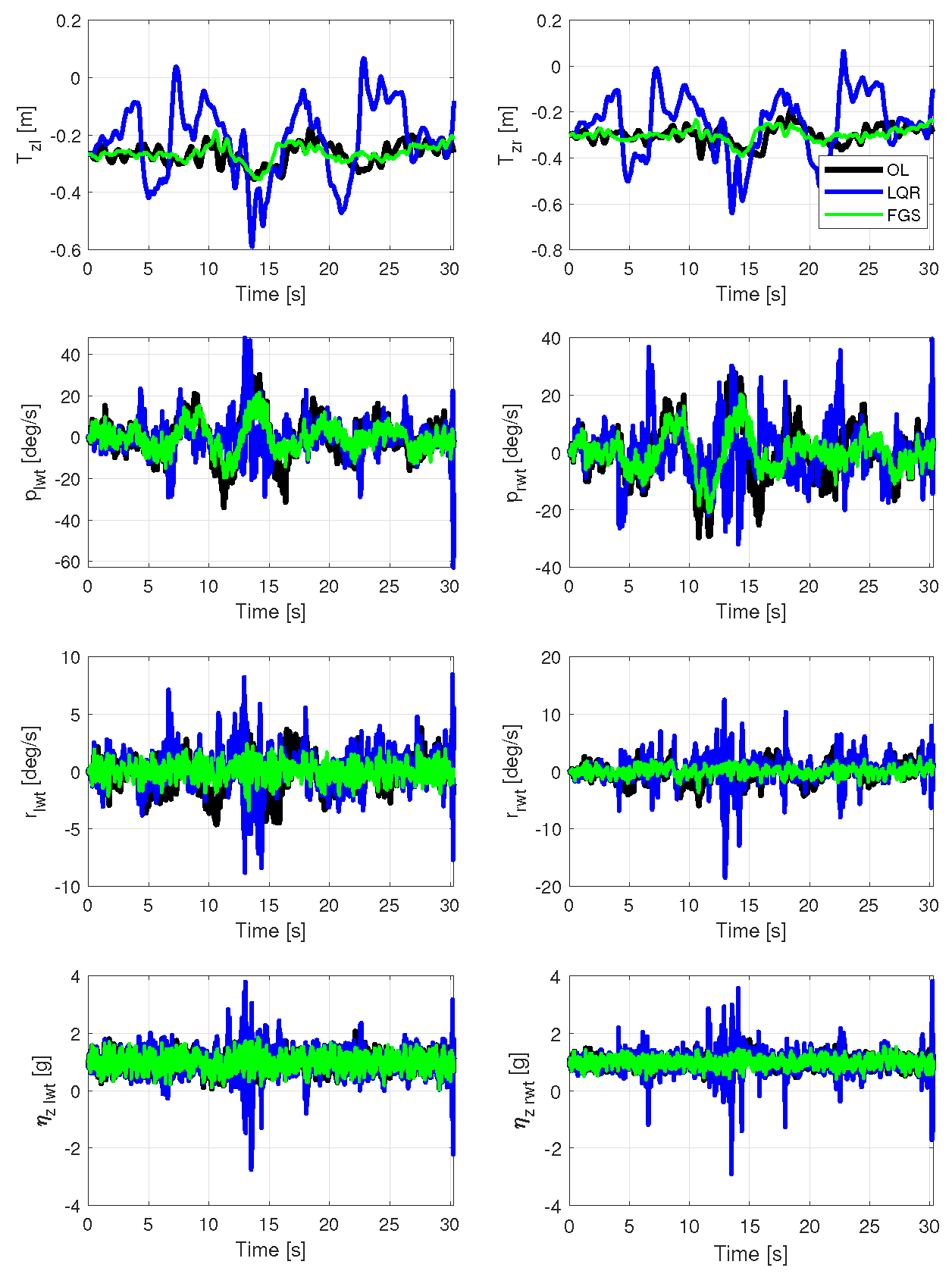

The wingtip outputs depicted in

Figure 15 reveal a greater attenuation in wingtip displacement for the controller that combines LQR and LMI methods compared to the LQR-only controller. This is attributed to the more pronounced aileron deflections for the LQR design, as observed in

Figure 16, resulting in a greater aerodynamic force on the ailerons and, consequently, in wingtip displacement. While

Figure 15 may not clearly indicate whether the FGS controller outperforms the open-loop one,

Table 5 demonstrates that the FGS controller exhibited better performance for all outputs.

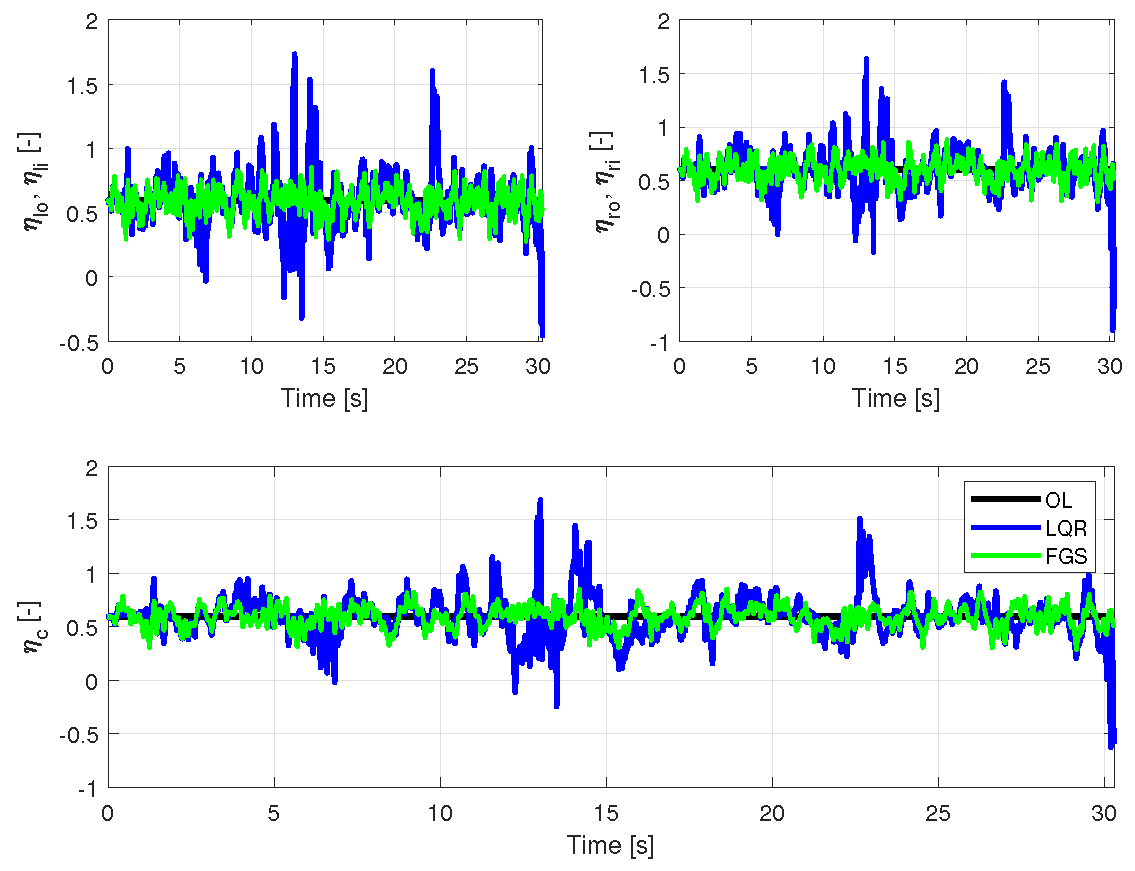

The FGS design demonstrated lower expended control energy, consistent with the previous simulation. In terms of motor usage, as shown in

Figure 17, the FGS was able to stay within the limits, while the LQR exceeded the limits on several occasions. This is particularly crucial for HALE aircraft, where control of energy usage is critical. The results presented in

Table 6 underscore a significant improvement in this regard.

Figure 17.

Motor entries for a velocity of 14.5 m/s, subjected to von Kármán wind turbulence, with two different output feedback realizations and open loop.

Figure 17.

Motor entries for a velocity of 14.5 m/s, subjected to von Kármán wind turbulence, with two different output feedback realizations and open loop.