1. Introduction

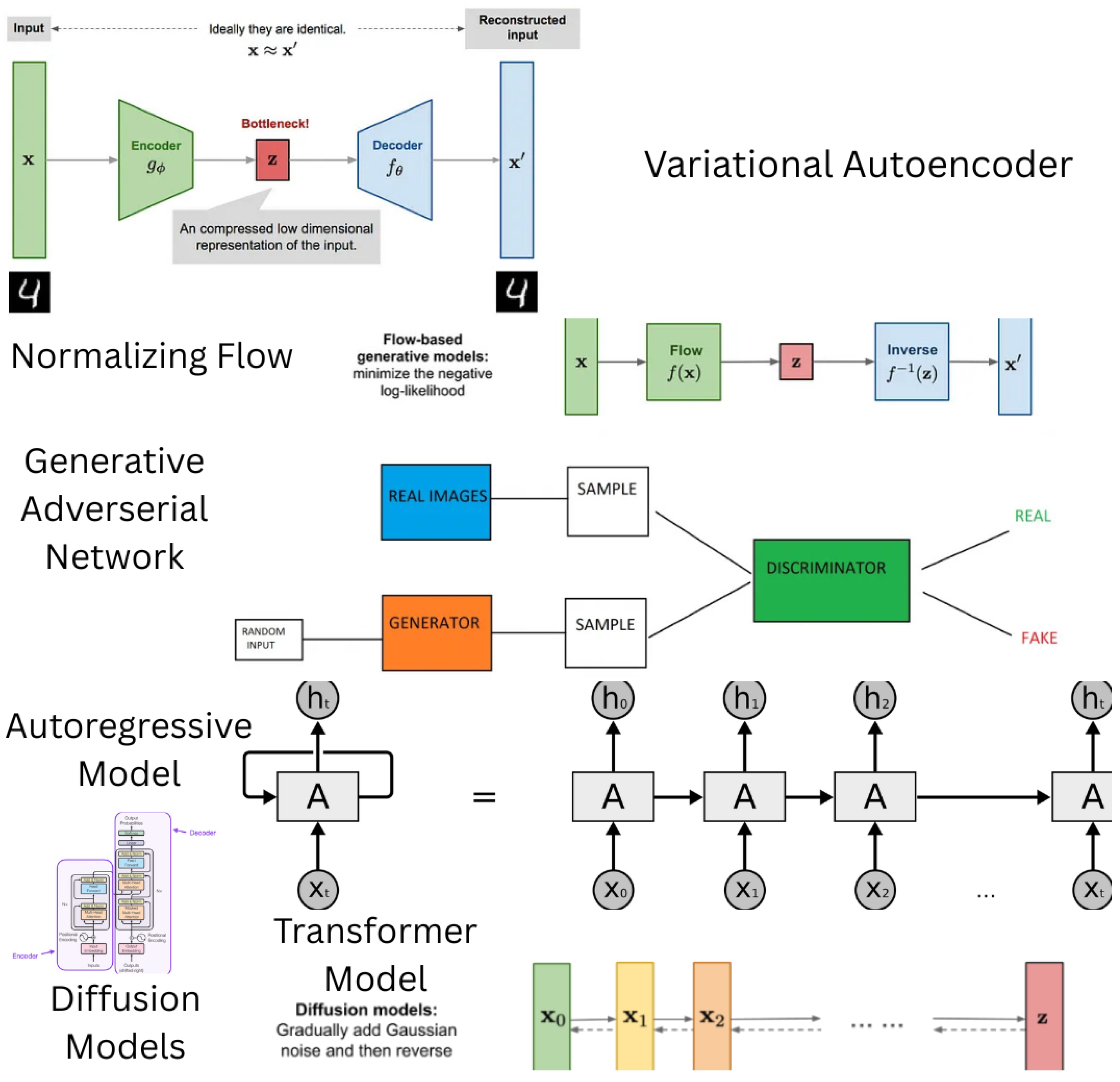

The rise of generative artificial intelligence is powered by many factors like vast amounts of data, deep learning algorithms, transformer architecture, and high-performance computing accelerated by graphics processing units (GPUs). These technological advancements have led to the creation of powerful GenAI models, particularly large language models (LLMs) like generative pre-trained transformers (GPT). The exceptional performance of GenAI models (e.g., OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 Turbo, GPT-4, and GPT-4o) and their access through user-friendly interfaces have brought text and image generation to the forefront of daily and commonplace conversations. Techniques like Prompt Engineering are involved in building application features like Deep Research, Reason, along with useful additional features in LLMs like Web Search. Now, GenAI is transforming the world, driving innovations in a wide range of industries and emerging applications.

The education industry is among the first to embrace GenAI and benefits significantly from the resources provided through applications like GenAI-powered chatbots [

1]. Chatbots powered by GenAI can assist customers with their queries and troubleshoot technical issues. GenAI is helping customers get a better experience in a variety of domains related to education. Today, there are various fine-tuned LLMs that are domain-specific, like those for healthcare, which can help answer queries related to healthcare. Overall, the potential of GenAI for education is vast and will continue to grow as the technology evolves [

2]. Recent research works applying a multitude of GenAI models to the education domain include an overview of the current state and future directions of generative AI in education along with applications, challenges, and research opportunities [

3]. The work [

4] explains how large language models like GPT-4 can enhance personalized education through dynamic content generation, real-time feedback, and adaptive learning pathways within Intelligent Tutoring. The work [

5] investigates the perceived benefits and challenges of generative AI in higher education from the perspectives of both teachers and students. It further explores concerns regarding the potential of AI to replace educators and examines its implications for digital literacy through the lenses of the SAMR and UTAUT models. The work [

6] discusses the role of generative AI in education and research, emphasizing its potential to support educational goals while also addressing ethical concerns and the professional use of AI-generated content.

While existing work has explored the potential of GenAI for the education sector, there remains a gap between research outcomes and real-world applications. The existing literature primarily focuses on the theory or vision of GenAI for education, often overlooking the implications and challenges that exist in practice. To that end, we first examine the commonly used GenAI models for education by highlighting their theoretical foundations and relevance to key use cases. Then, we specifically focus on LLMs and provide an overview of the practical applications of LLMs as found in the education industry today. The developed LLM-based application utilizes innovative fine-tuning and evaluation strategies. In our research work, we have used inference strategies like zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot techniques and fine-tuning approaches using PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) techniques like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) and Prompt Tuning. We have also utilized the technique of Reinforcement Learning with PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) and PEFT to generate less toxic summaries. The model’s performance is quantitatively evaluated using the ROUGE metric and toxicity evaluation metrics. The chatbot can summarize dialogues and is of immense interest to users in the real world, leading to the development of safer and more effective AI systems.

3. LLMs for Education

Large Language Models (LLMs) have become pivotal in educational applications due to their ability to process and generate human-like text. This section explores their practical implementations, focusing both on theoretical advancements and real-world deployments.

3.1. Student Support and Personalized Learning

Domain-specific LLMs are transforming academic support and personalized education. LLM-based tutoring platforms assist students in real-time with subject-specific doubts, curate personalized learning plans based on performance history, and generate explanations aligned with individual understanding levels. These systems can also engage in natural language check-ins to ensure student progress and offer targeted supplemental materials.

Platforms such as Khanmigo by Khan Academy illustrate these capabilities. They employ fine-tuned LLMs to offer interactive AI tutors that explain mathematical problems step-by-step or simulate historical conversations for immersive learning. These tutors are grounded in educational content and best pedagogical practices to provide contextual and adaptive support.

Moreover, LLM-powered virtual academic advisors enhance student engagement by interpreting behavioral signals, summarizing professor feedback, and initiating proactive interventions to maintain academic progress.

3.2. Faculty and Administrative Assistance

LLMs streamline repetitive academic and administrative tasks, increasing educator productivity. These assistants can draft lesson plans, summarize research articles, generate quizzes from textbook material, and communicate professionally with students and parents.

For instance, Microsoft’s Copilot for Education, integrated into platforms like Microsoft Teams and Word, already helps educators create assignments, summarize lectures, and design assessments aligned with curriculum standards.

In parallel, LLM-powered bots handle routine administrative inquiries—such as course registration, deadlines, and financial aid—thus reducing staff workload and enhancing the student experience.

3.3. Curriculum Planning and Educational Analytics

Educational leaders are leveraging LLMs to interact with academic data through natural language. These systems analyze student performance, detect learning gaps, and provide actionable insights for curriculum enhancement.

Tools like Ivy.ai and Gradescope with AI assistance support real-time feedback, pattern recognition in assignment submissions, and identification of learning bottlenecks. They can recommend course redesign strategies and prioritize interventions using longitudinal performance data.

Generative AI can also simulate new learning environments using synthetic data, supporting curriculum development and strategic planning.

3.4. Educational Standards Chatbots and Knowledge Access

Comprehending evolving academic standards (e.g., Common Core, NGSS, Bloom’s Taxonomy) across disciplines is complex. LLM-based systems, especially those powered by Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), simplify access to these documents, aiding educators and curriculum developers.

RAG-powered curriculum alignment bots enable teachers to instantly understand how lesson objectives relate to standards or compare regional benchmarks. These tools support transparency, alignment, and compliance with evolving frameworks.

Additionally, LLMs support inclusive education by translating content across languages, simplifying academic jargon, and adapting materials for diverse learner needs.

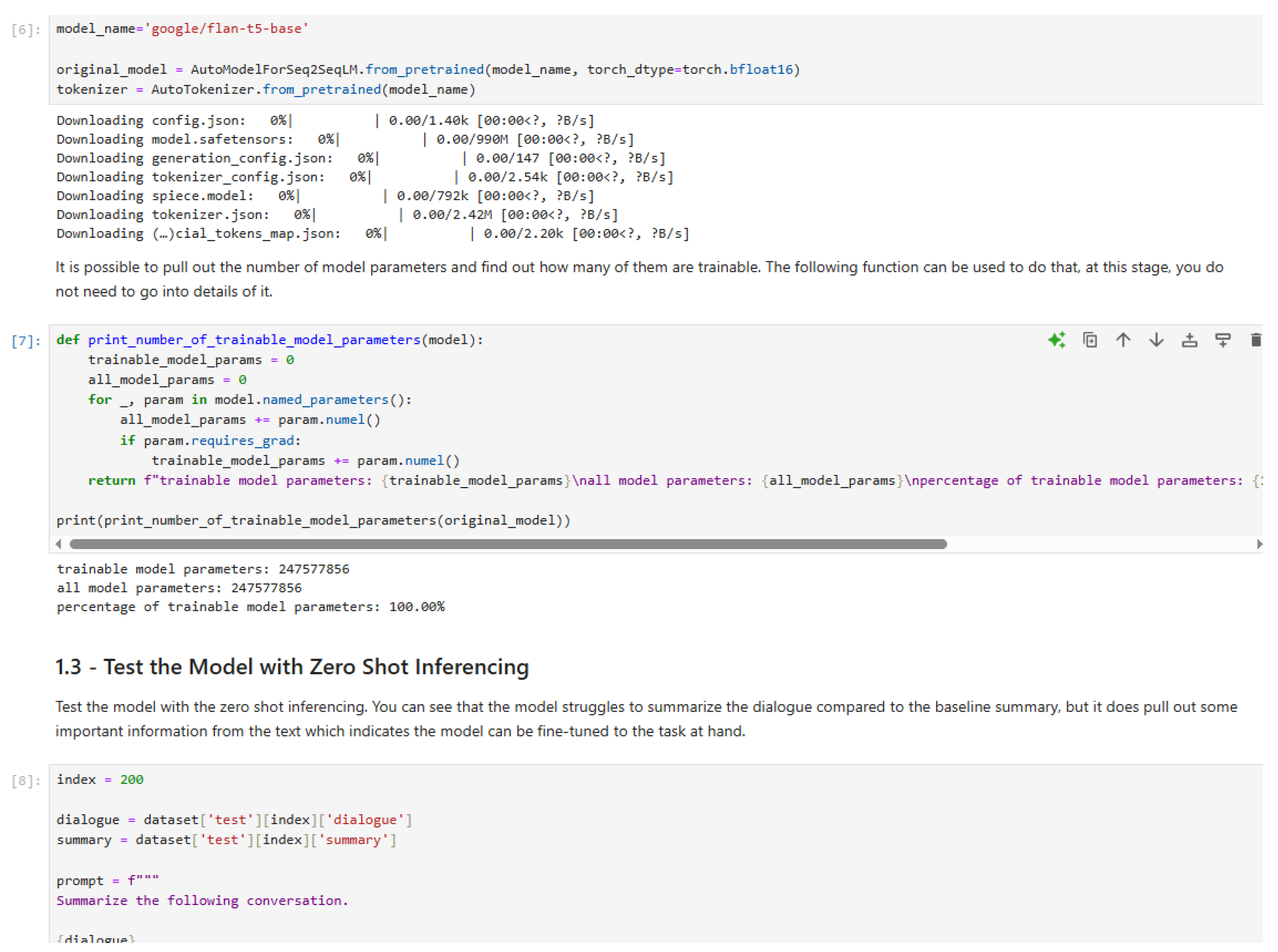

3.5. Research Implementation: Dialogue Summarization Chatbot

Our own research demonstrates a practical implementation of LLMs in education through the development of a dialogue summarization chatbot. This chatbot leverages zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot inferencing with fine-tuned FLAN-T5 using PEFT techniques such as LoRA and Prompt Tuning. We also employed Reinforcement Learning with Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) to reduce toxic content in the generated summaries. The system is quantitatively evaluated using the ROUGE metric and toxicity evaluation tools, achieving strong results in both summarization quality and safety, thereby supporting real-world classroom integration.

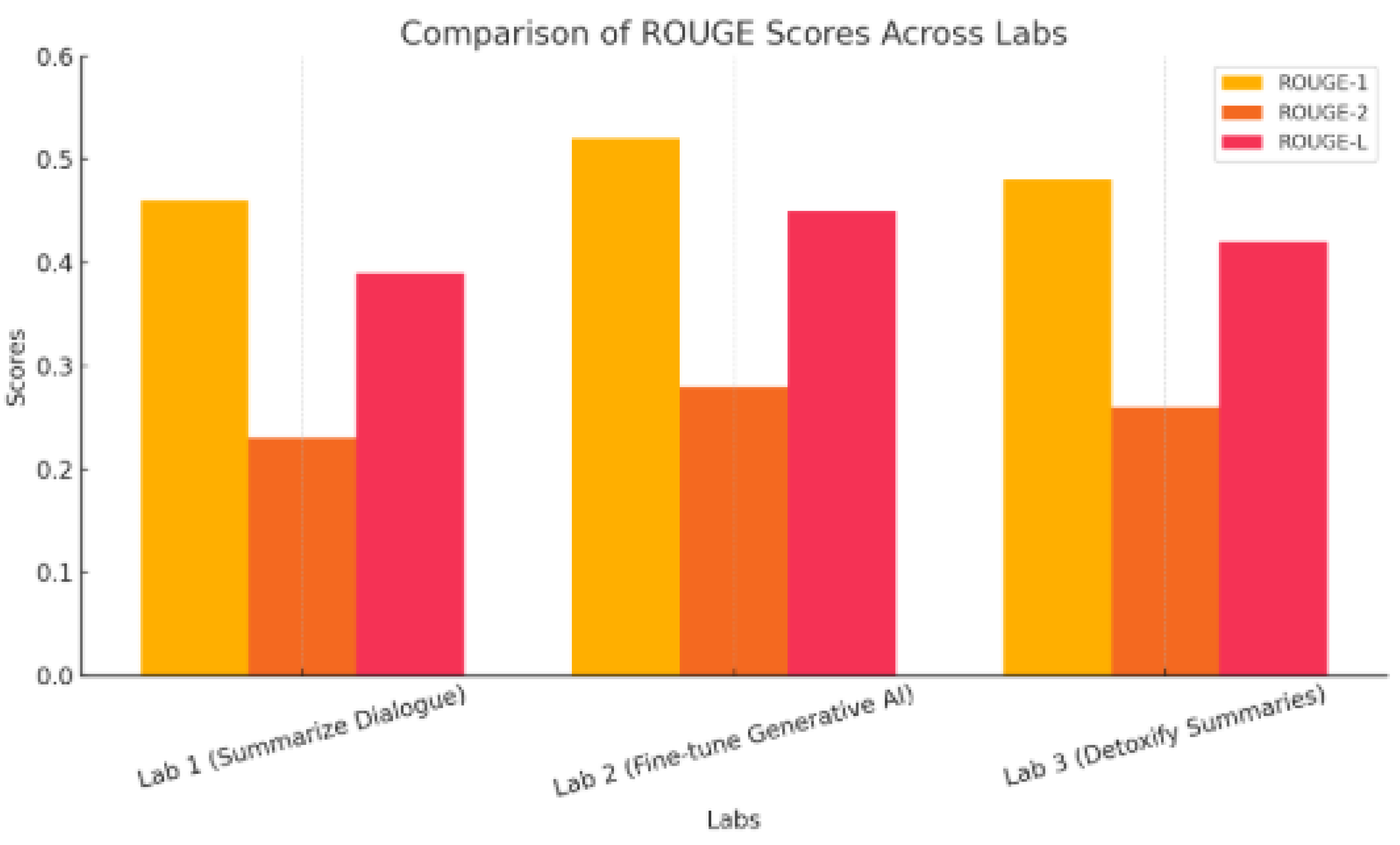

4. Design Aspects

The development and deployment of generative AI (GenAI) applications, particularly large language models (LLMs), require careful consideration of design aspects to ensure they meet the specific requirements of the education sector. While cloud-based GenAI services offer a rapid entry point, their general-purpose nature often lacks the depth of training on education-specific datasets, limiting their effectiveness for targeted educational applications. This section discusses key design aspects for building customized AI applications tailored to educational needs, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

4.1. High-Performance Computing for AI

The transformer architecture, foundational to modern large language models (LLMs), demands substantial computational resources due to its intricate design. Unlike other AI systems, which have seen relatively modest growth in compute needs, transformer-based models experience exponential increases in resource requirements, driven by their complex layers and vast parameter sets. In educational environments, where processing large volumes of data—such as student engagement metrics, instructional content, or real-time feedback—is essential, high-performance hardware like multi-GPU clusters is critical for training and deploying these models effectively.

Advanced GPUs, such as NVIDIA’s latest architectures, provide tailored optimizations that enhance training efficiency, minimize memory usage, and enable scalable AI infrastructure. For instance, these GPUs support low-precision formats like FP8, which accelerate computations but risk degrading model quality if not carefully managed. To address this, modern GPU architectures incorporate mixed-precision engines that dynamically balance FP8 and FP16 operations, automatically adjusting to preserve accuracy. This capability is particularly valuable for educational tools, such as AI-driven essay grading systems or virtual tutoring platforms, where rapid inference ensures seamless user interactions.

In academic settings, high-performance computing systems enable efficient analysis of extensive datasets, such as course enrollment patterns, learning management system logs, or multilingual educational resources. Compared to traditional CPU-based setups, these platforms consume less energy, promoting sustainable operations. For example, AI-powered language translation tools for diverse classrooms or predictive analytics for student retention require low-latency processing to deliver timely insights, enhancing both teaching quality and administrative efficiency. As educational institutions increasingly adopt AI-driven solutions, high-performance computing will drive innovation, ensuring scalability without computational limitations.

4.2. Information Retrieval and Customization

While foundation LLMs are pre-trained on vast datasets using accelerated computing, their effectiveness in education depends on incorporating domain-specific knowledge and institutional data. Techniques like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), prompt engineering, and parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) enable customization to meet educational needs.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): RAG enhances LLMs by integrating external data sources, improving the accuracy and relevance of responses.

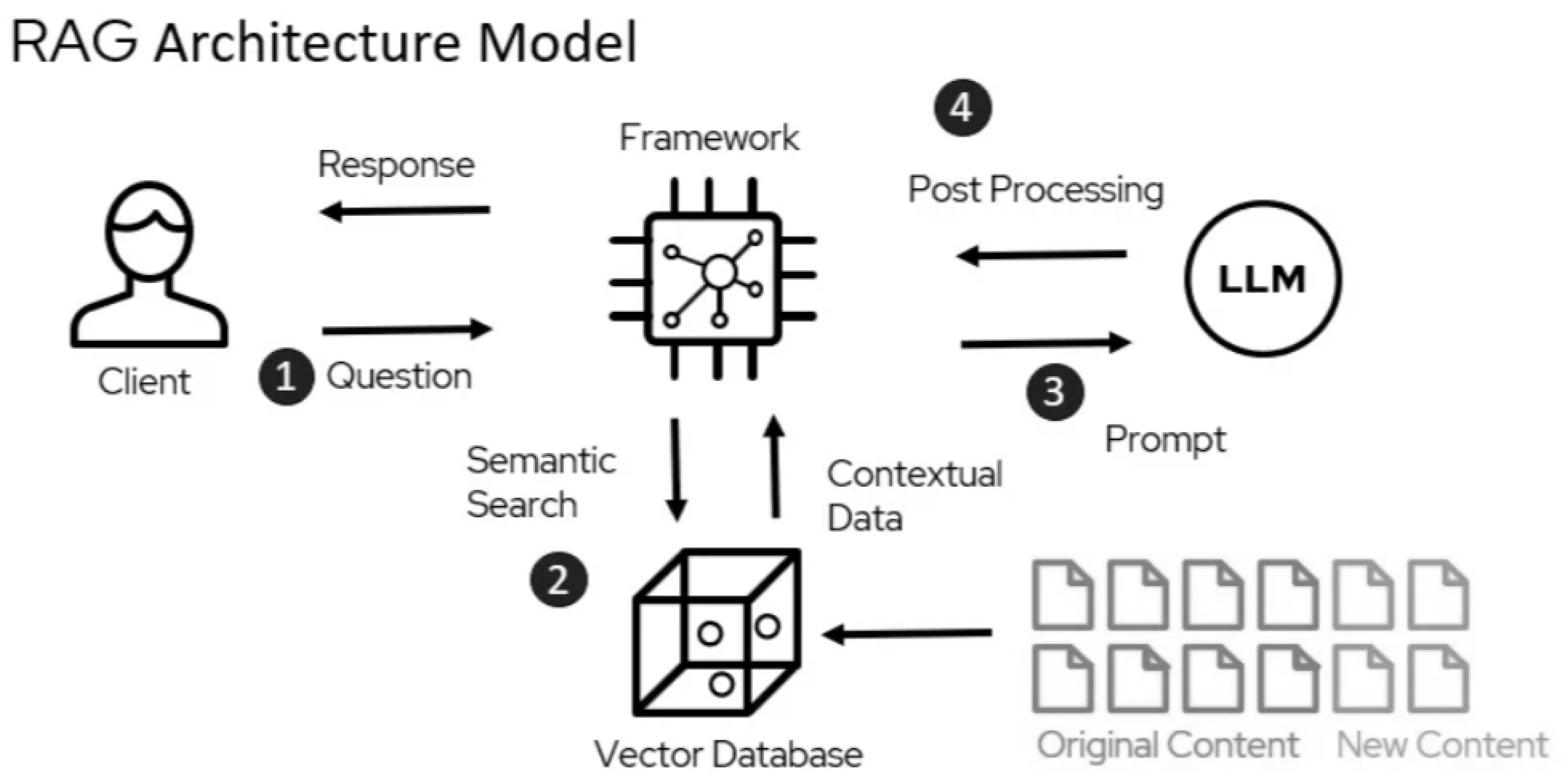

Figure 3 illustrates a typical RAG architecture model for educational applications, such as curriculum standards chatbots:

Step 1 (Question Submission): The process begins with a client, such as a teacher or student, submitting a question (e.g., querying a curriculum standard or seeking topic clarification).

Step 2 (Semantic Search): The question triggers a semantic search in a vector database, which stores embeddings of educational resources, including both original content (e.g., textbooks, academic standards) and new content (e.g., updated lesson plans or student data).

Step 3 (Prompt Construction): Relevant contextual data is retrieved from the vector database and used to construct a prompt, which is then fed into a Large Language Model (LLM).

Step 4 (Response Generation and Post-Processing): The LLM generates a response based on the prompt, which undergoes post-processing within a framework to ensure coherence and relevance before being delivered back to the client.

For example, a curriculum standards chatbot can use RAG to integrate educational standards (e.g., Common Core) into an LLM, enabling precise answers to domain-specific queries. This approach is particularly effective for applications like lesson planning, student support systems, or compliance with educational frameworks.

Customization Techniques: Beyond RAG, techniques like PEFT (e.g., LoRA and Prompt Tuning) and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) allow further customization. PEFT selectively updates a small subset of model parameters, making fine-tuning resource-efficient while adapting the LLM to educational datasets, such as student feedback, course materials, or assessment records. RLHF, combined with techniques like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), can reduce toxicity in generated outputs, as demonstrated in our dialogue summarization chatbot for classroom discussions, ensuring safer and more appropriate interactions in educational settings.

RAG and fine-tuning are complementary. RAG offers a quick way to enhance accuracy by grounding responses in external data, while fine-tuning provides deeper customization for applications requiring high precision, such as personalized learning systems or automated grading tools. The choice of approach depends on the application’s requirements, resource availability, and computational constraints. For instance, a chatbot for summarizing classroom dialogues can initially use RAG to incorporate lecture transcripts and later apply PEFT for improved performance, as shown in our research implementation.

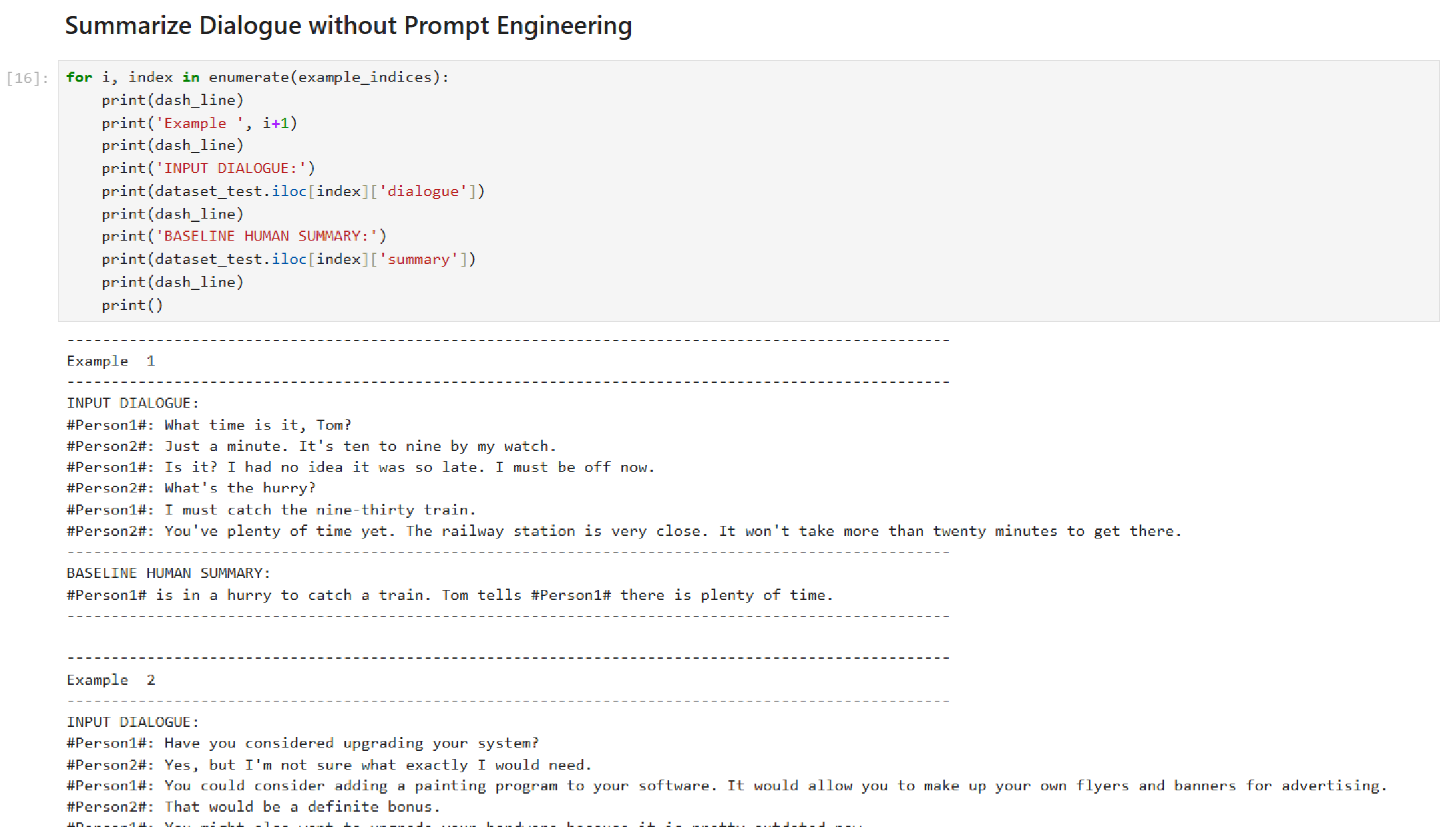

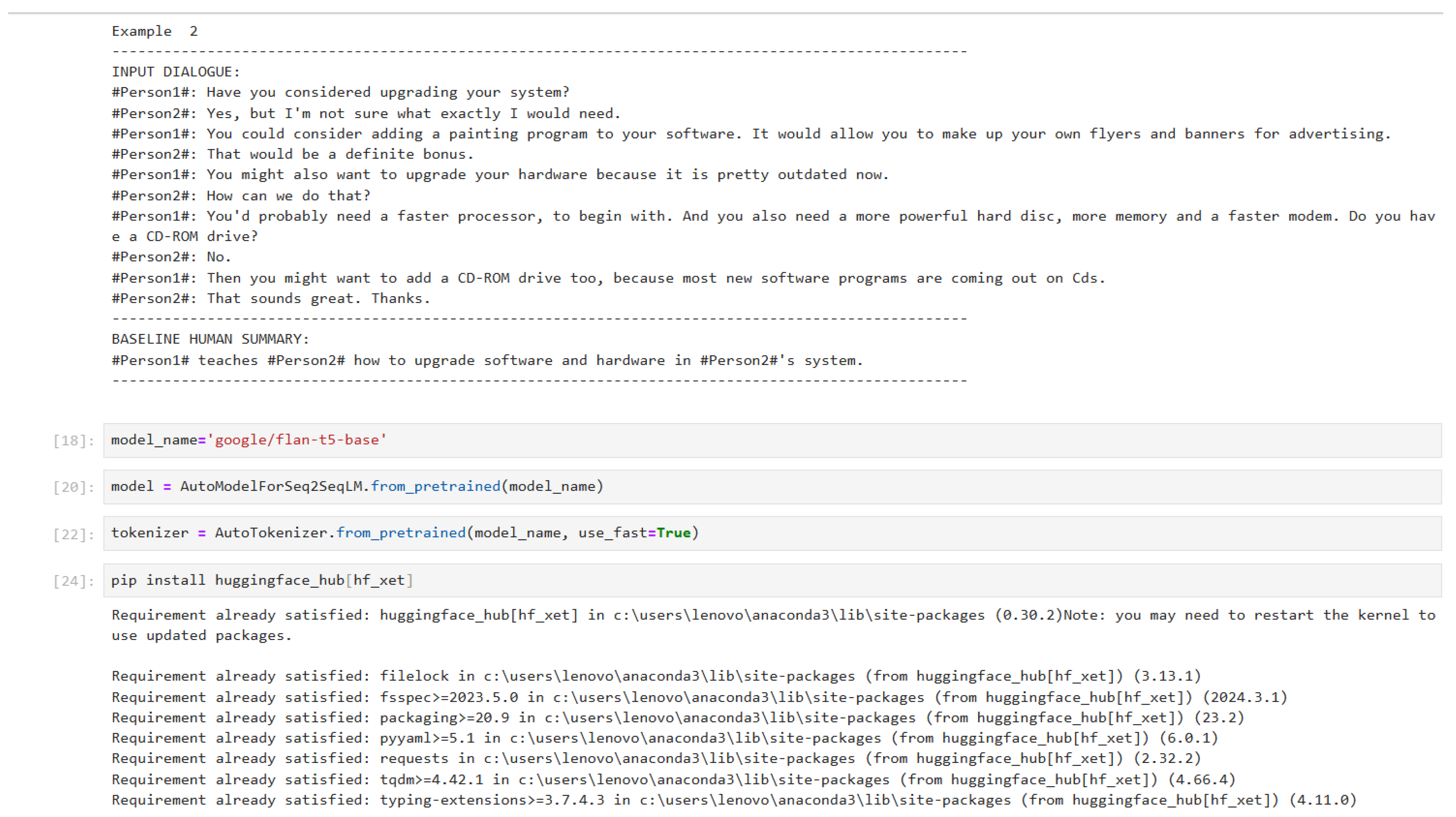

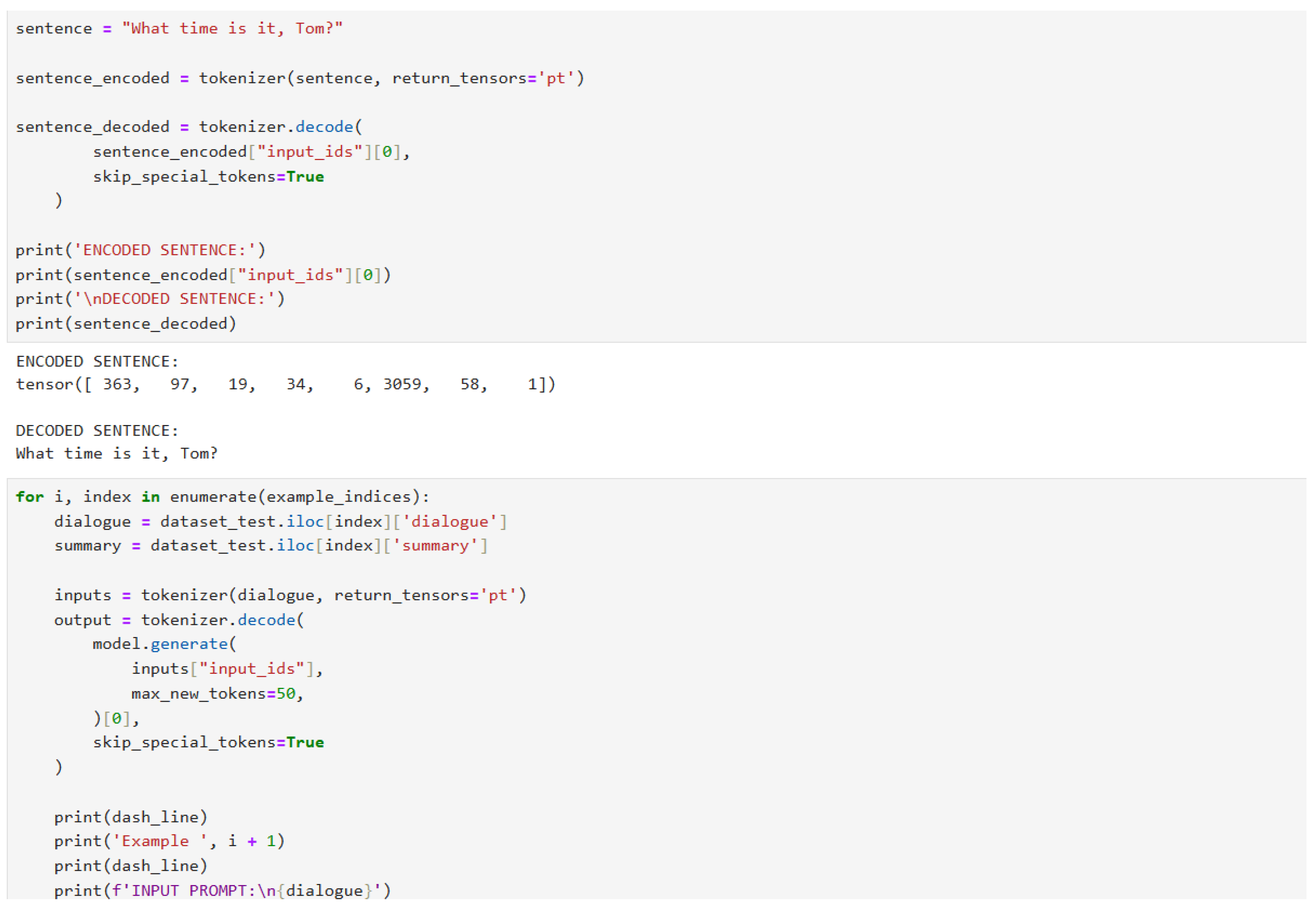

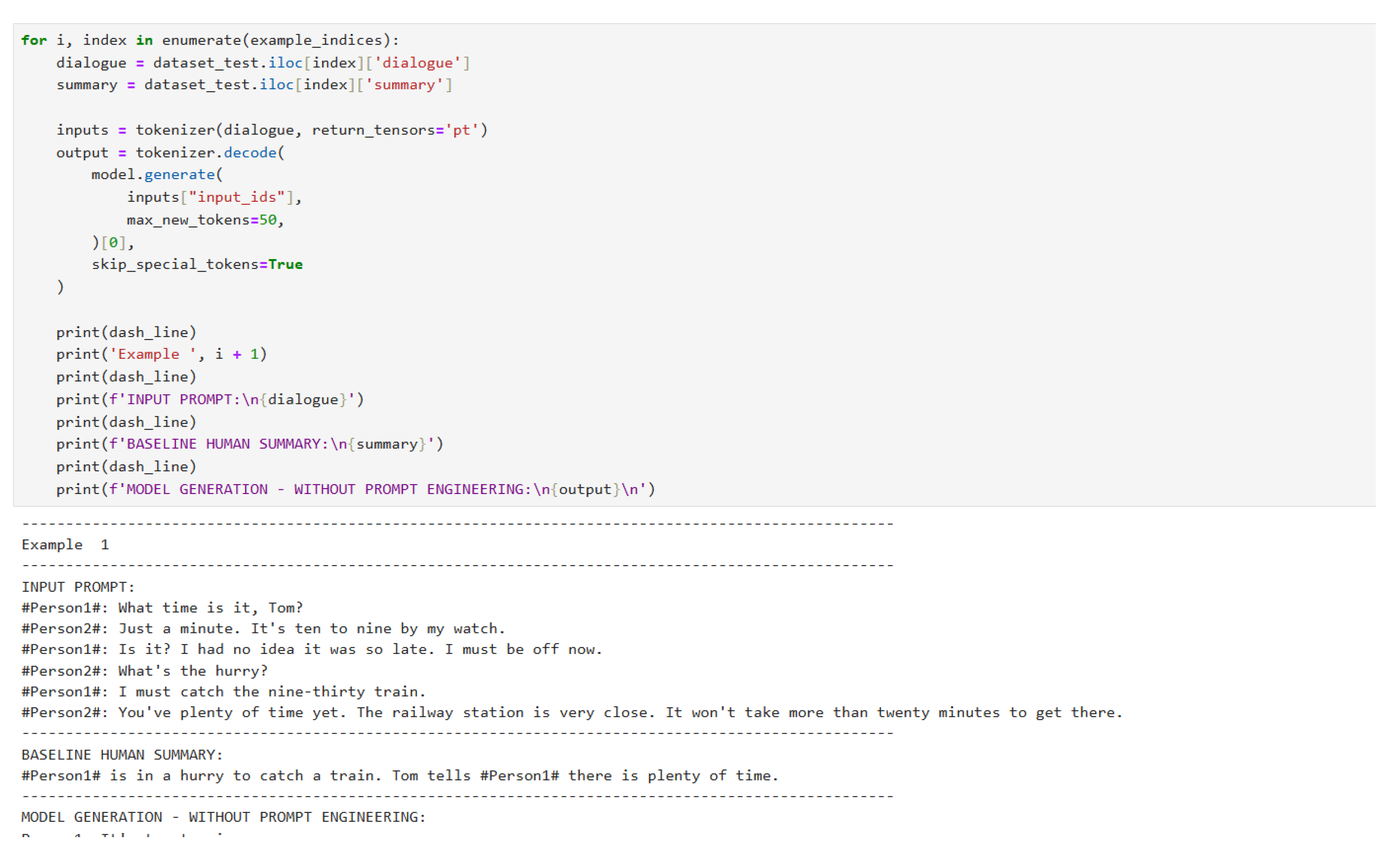

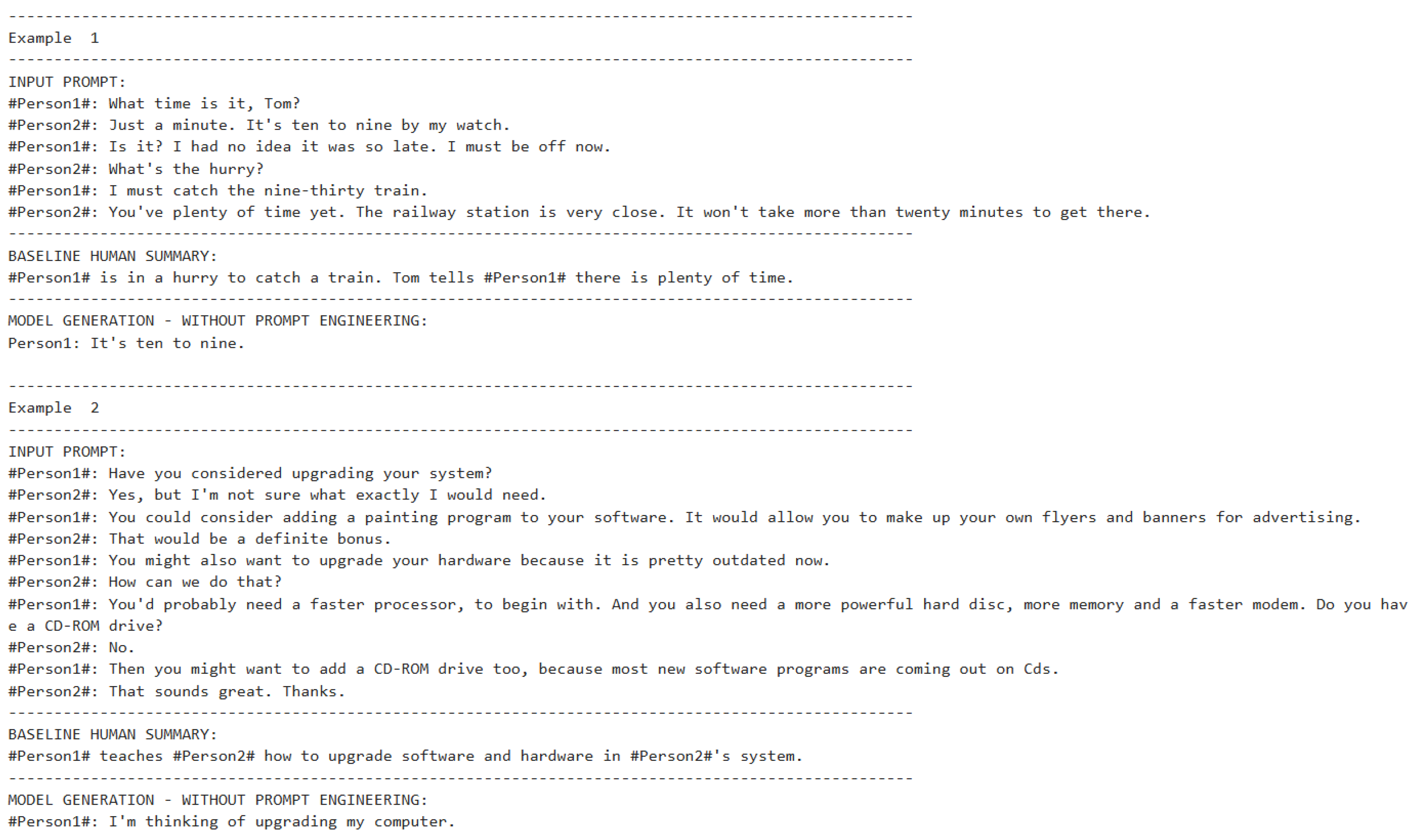

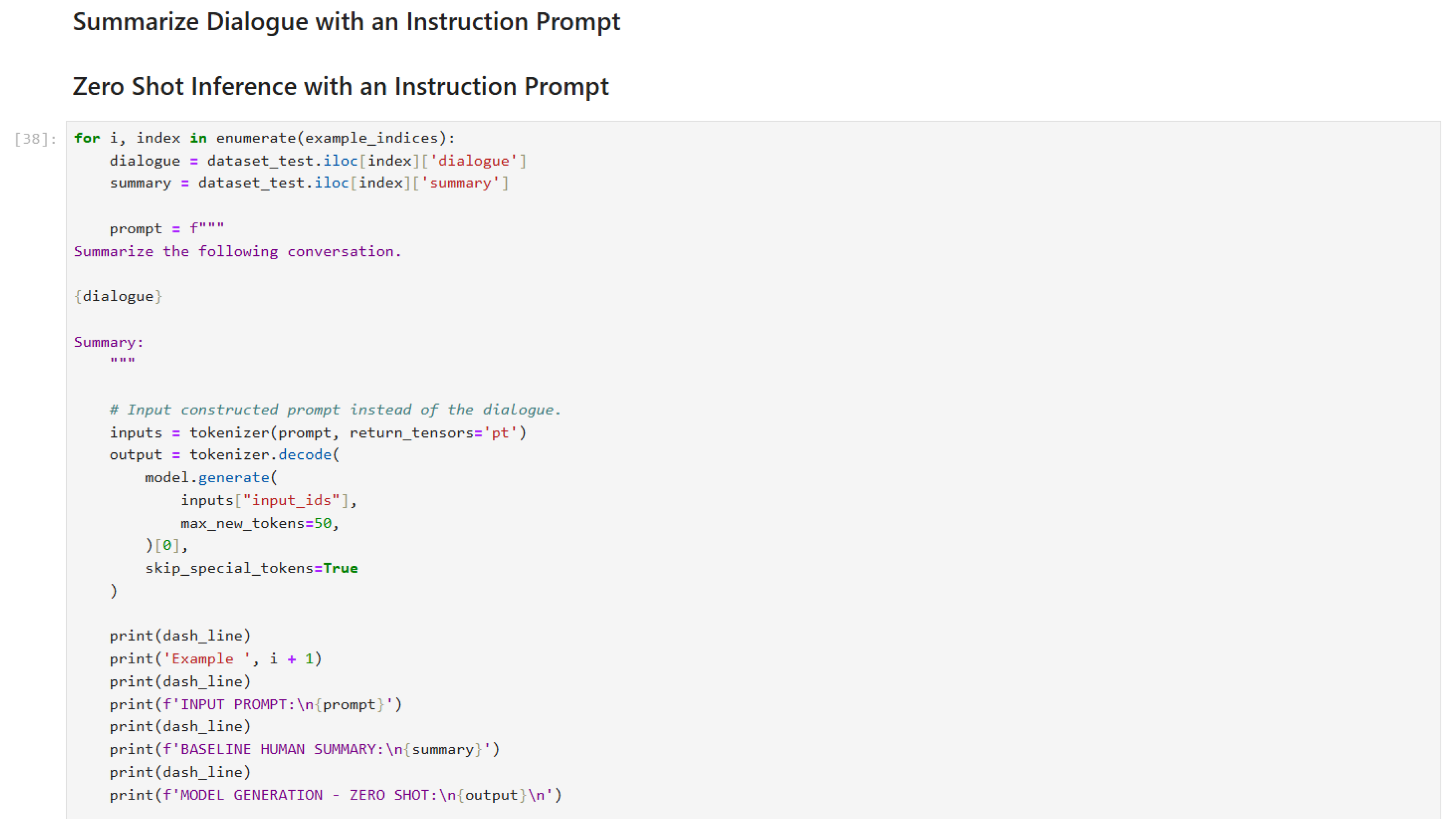

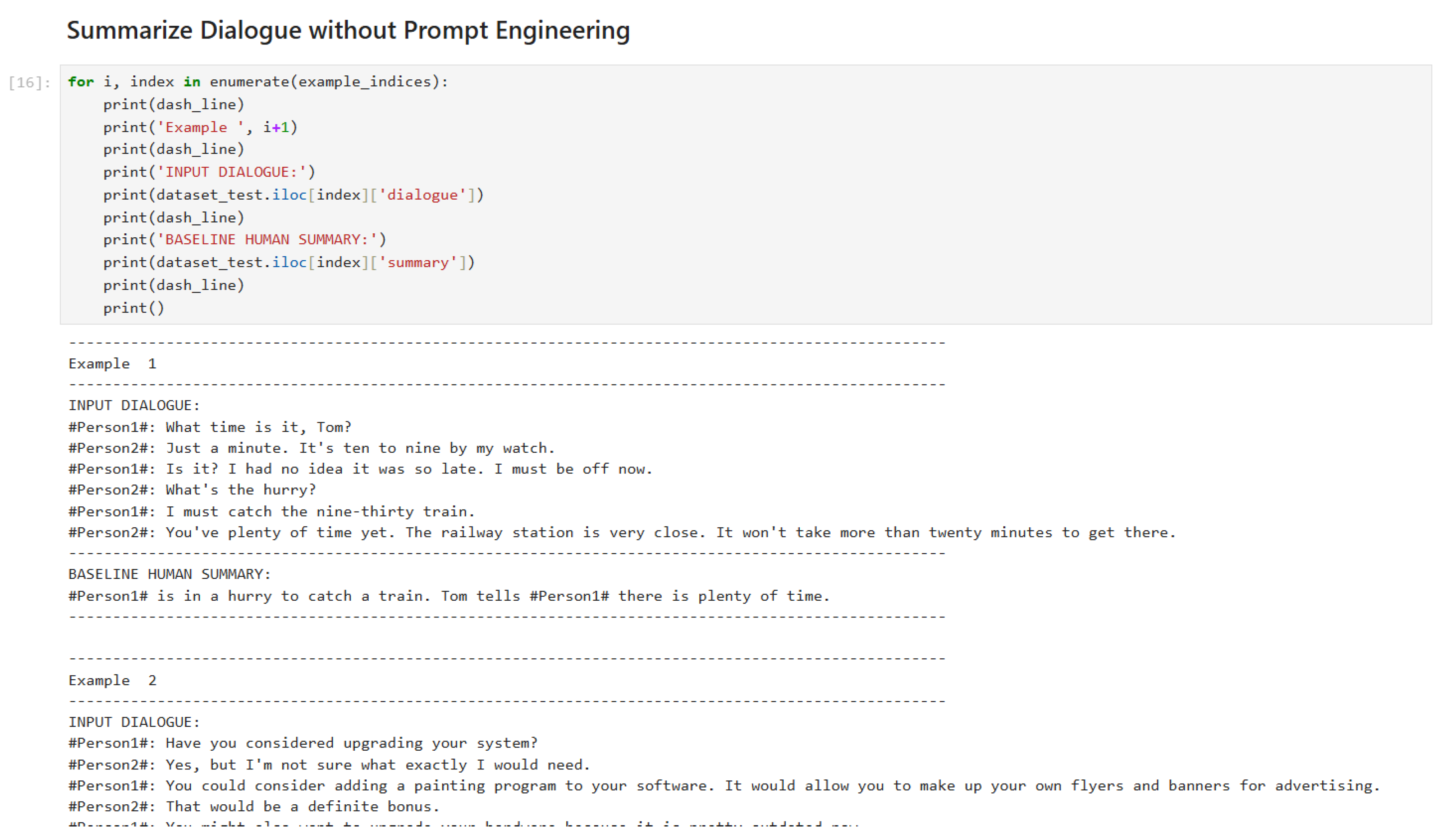

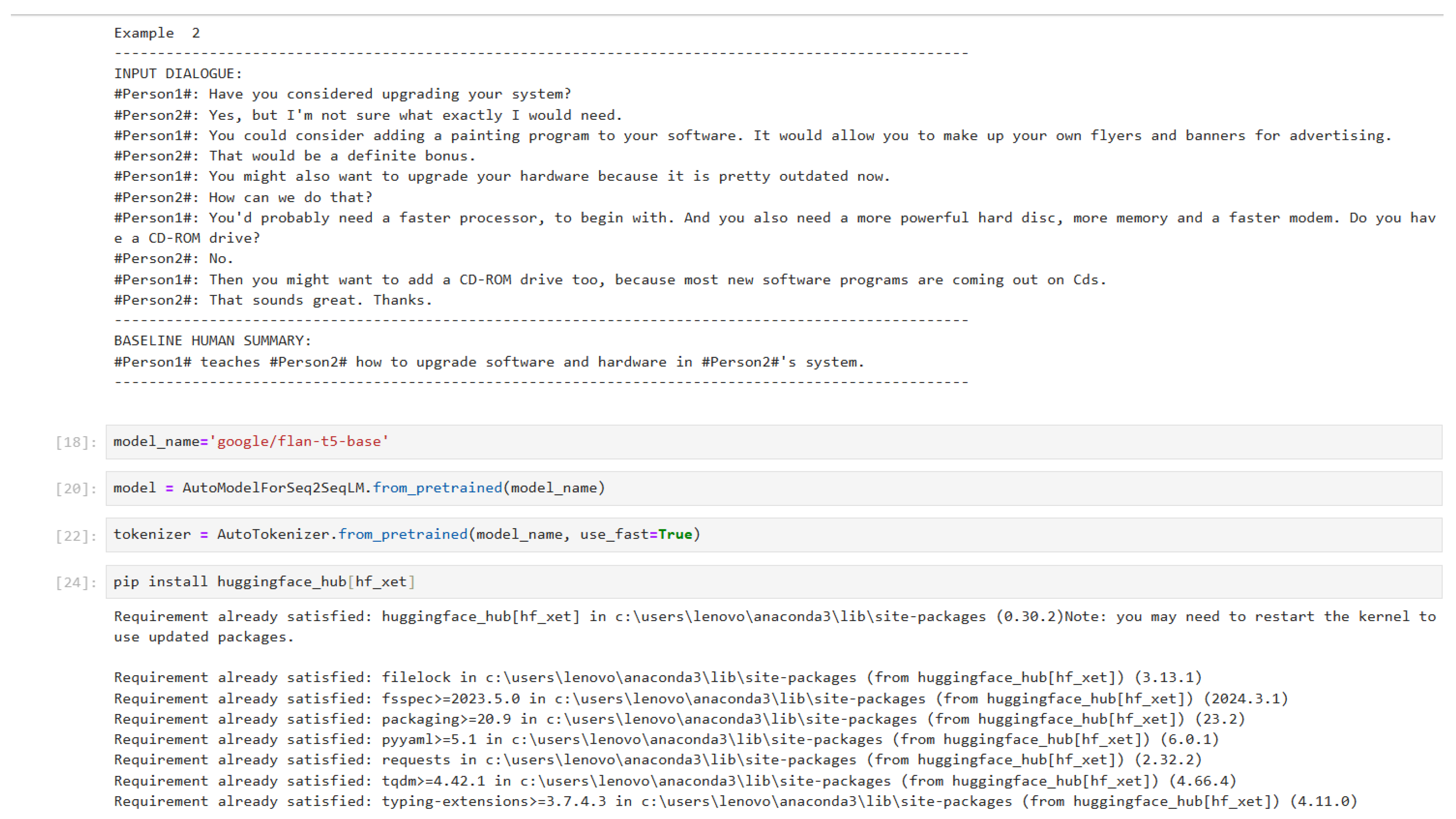

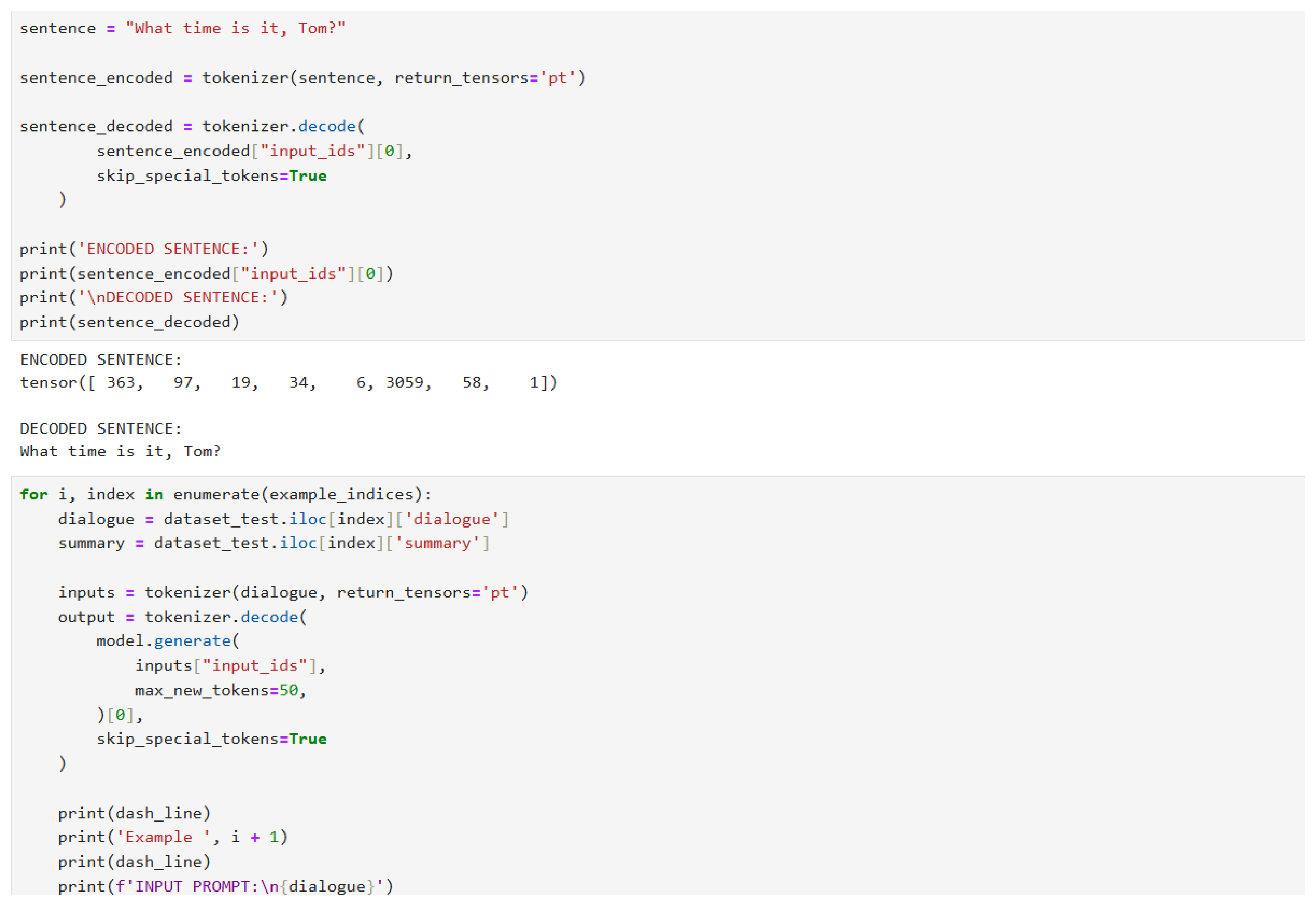

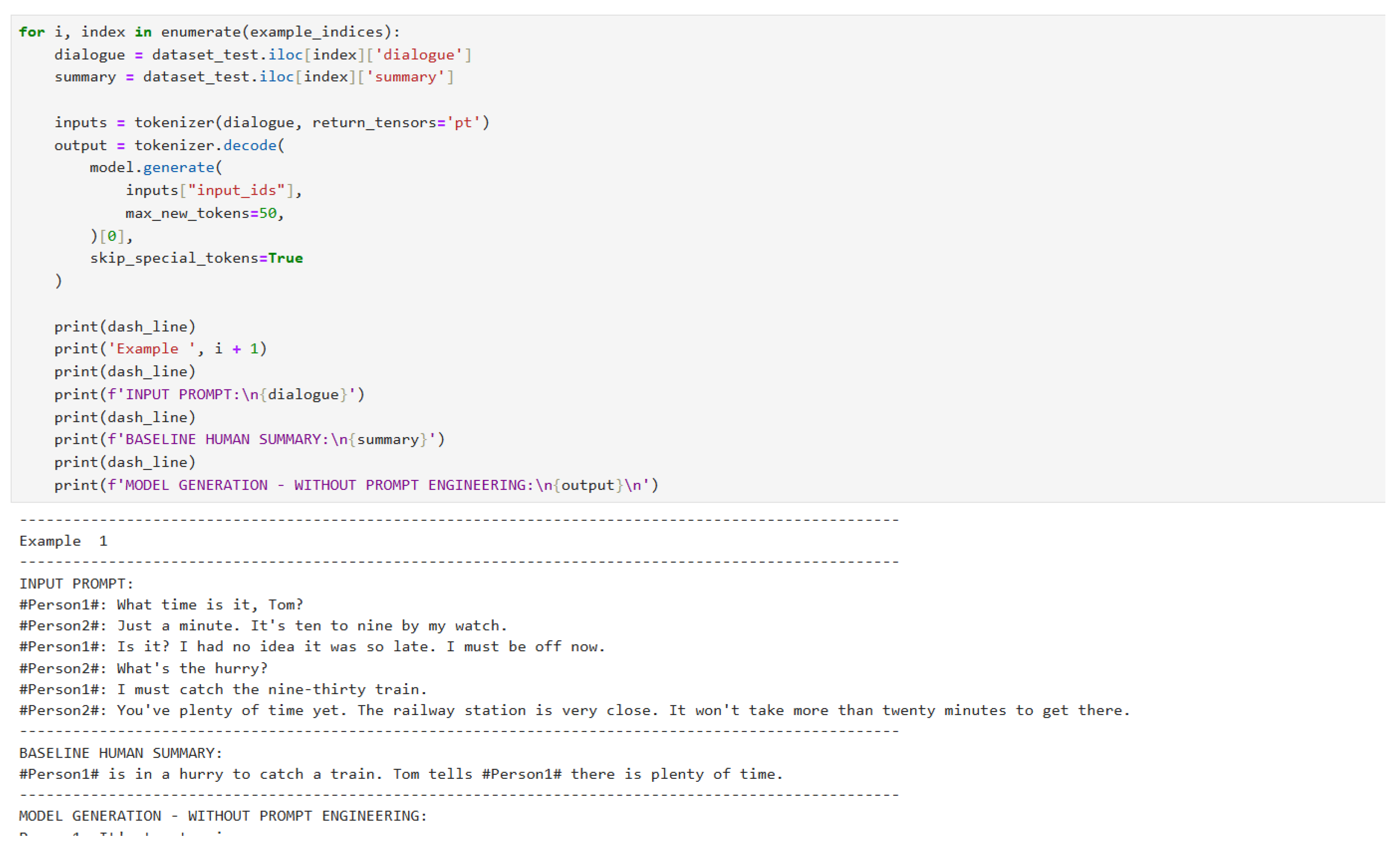

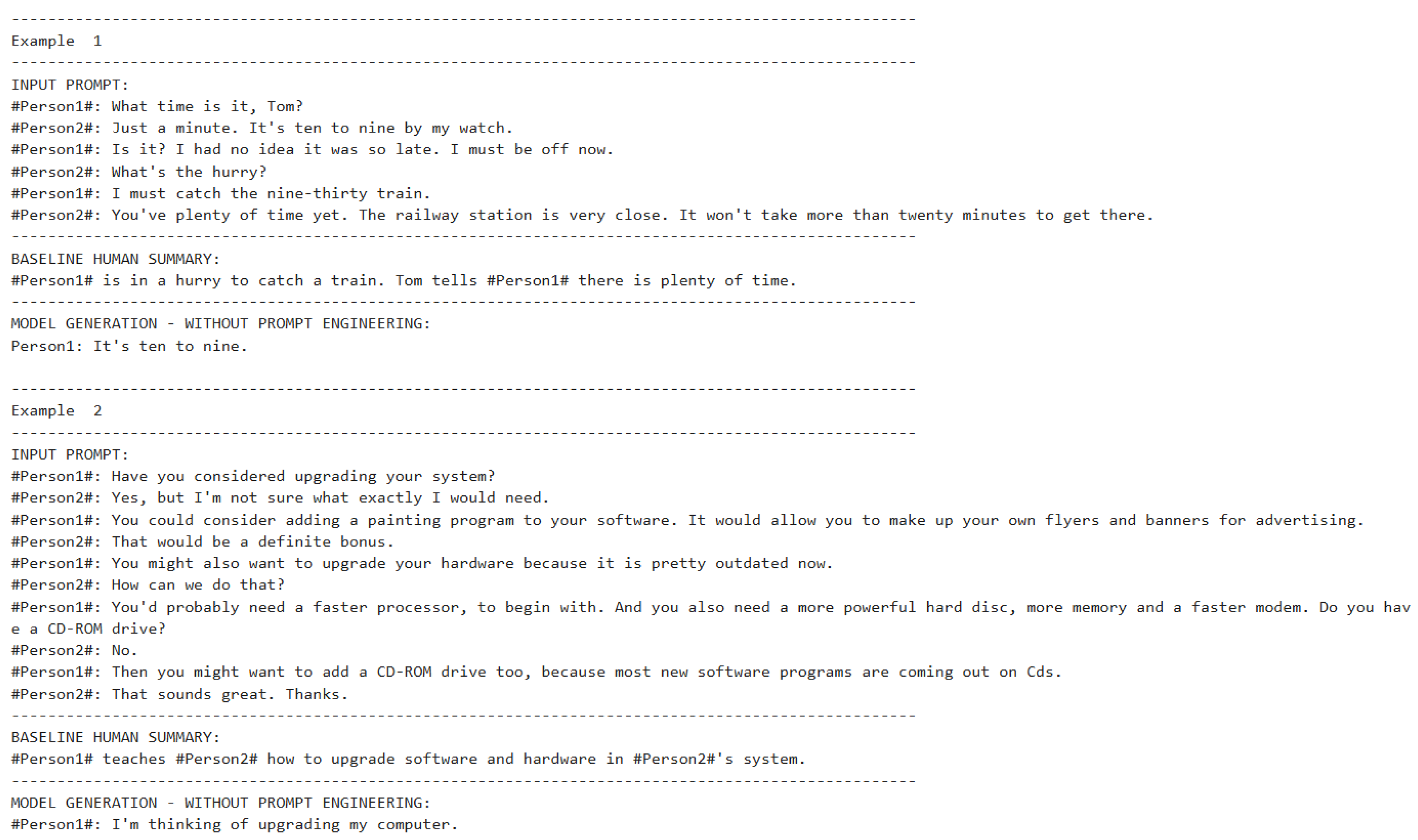

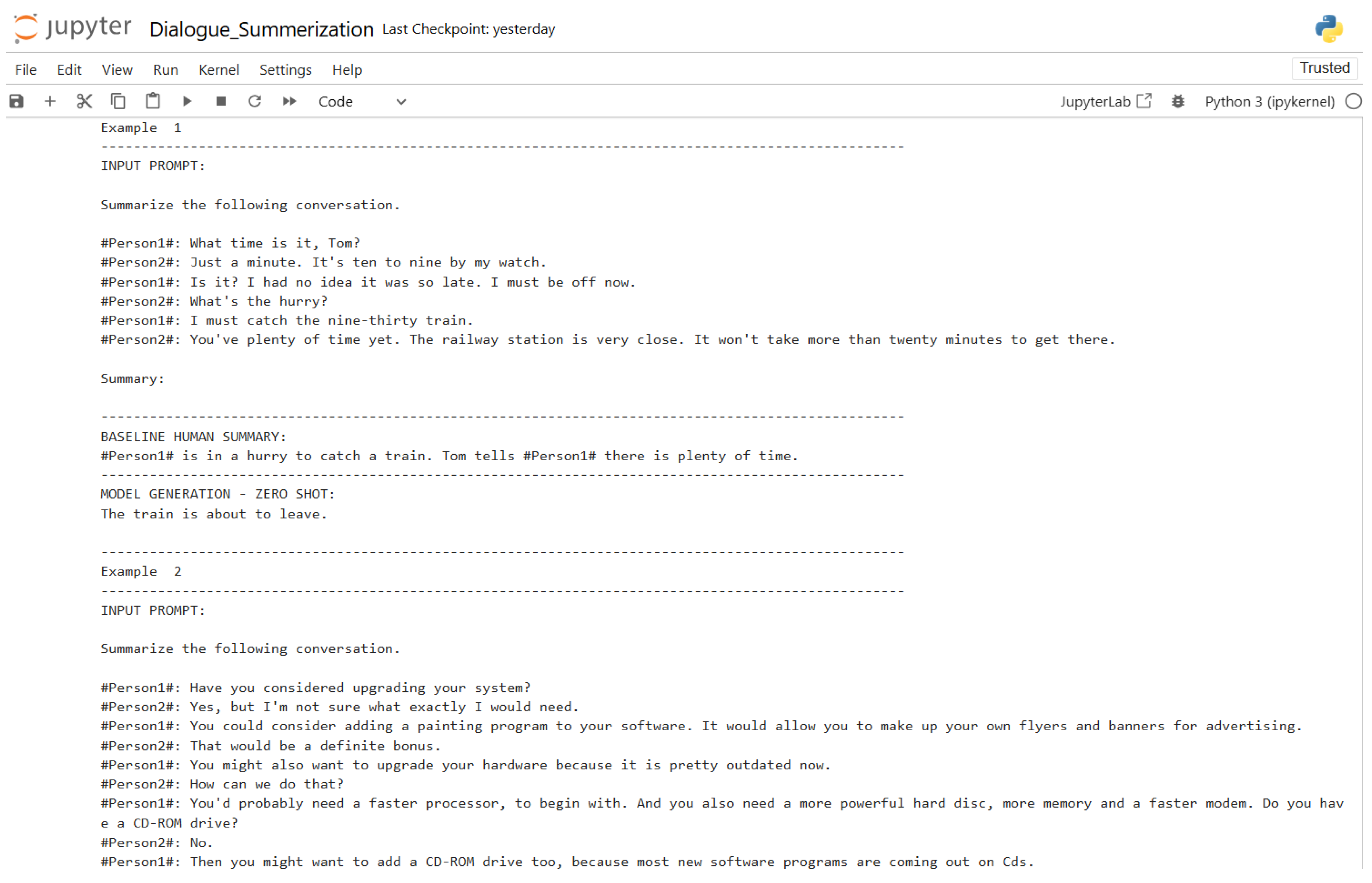

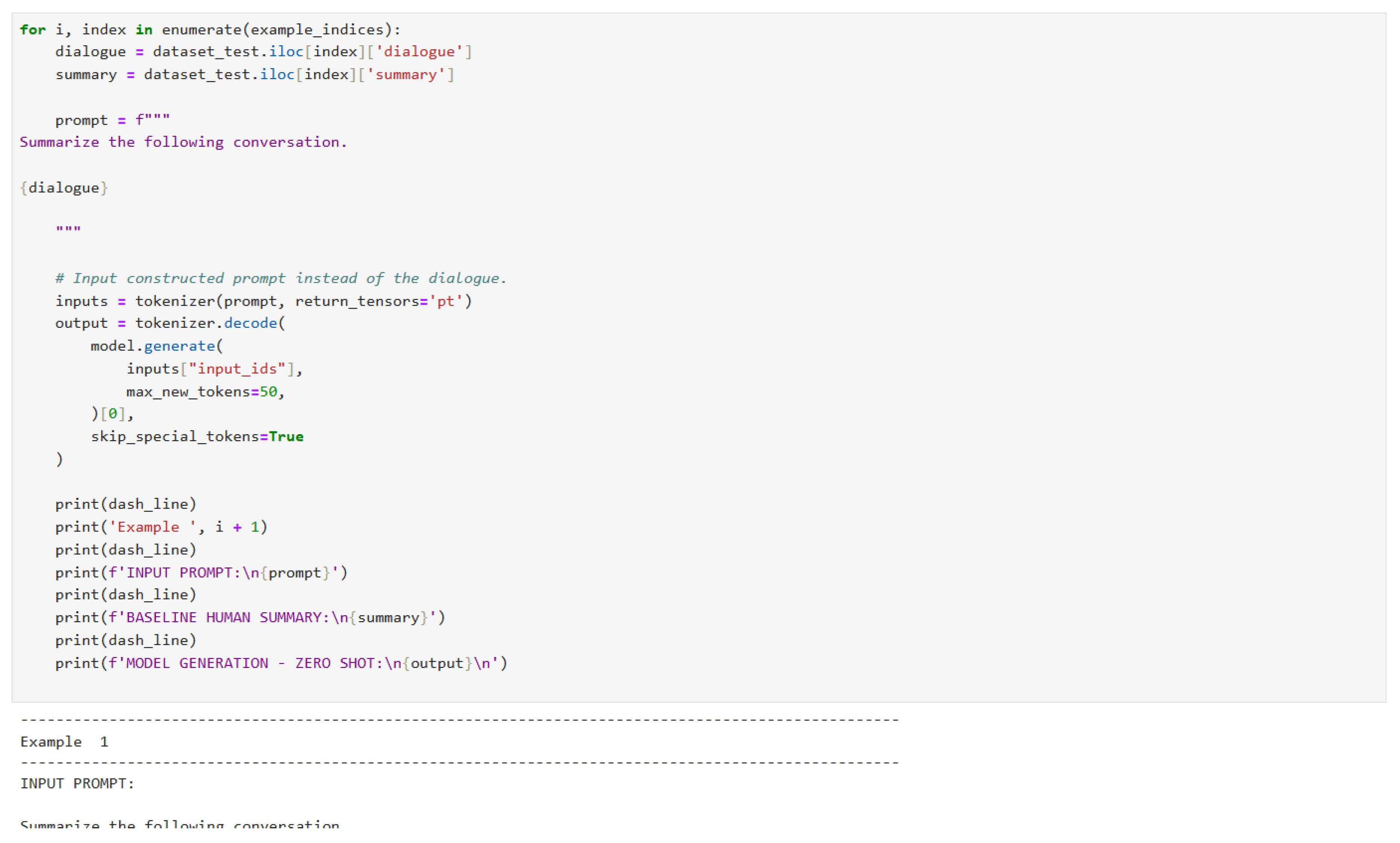

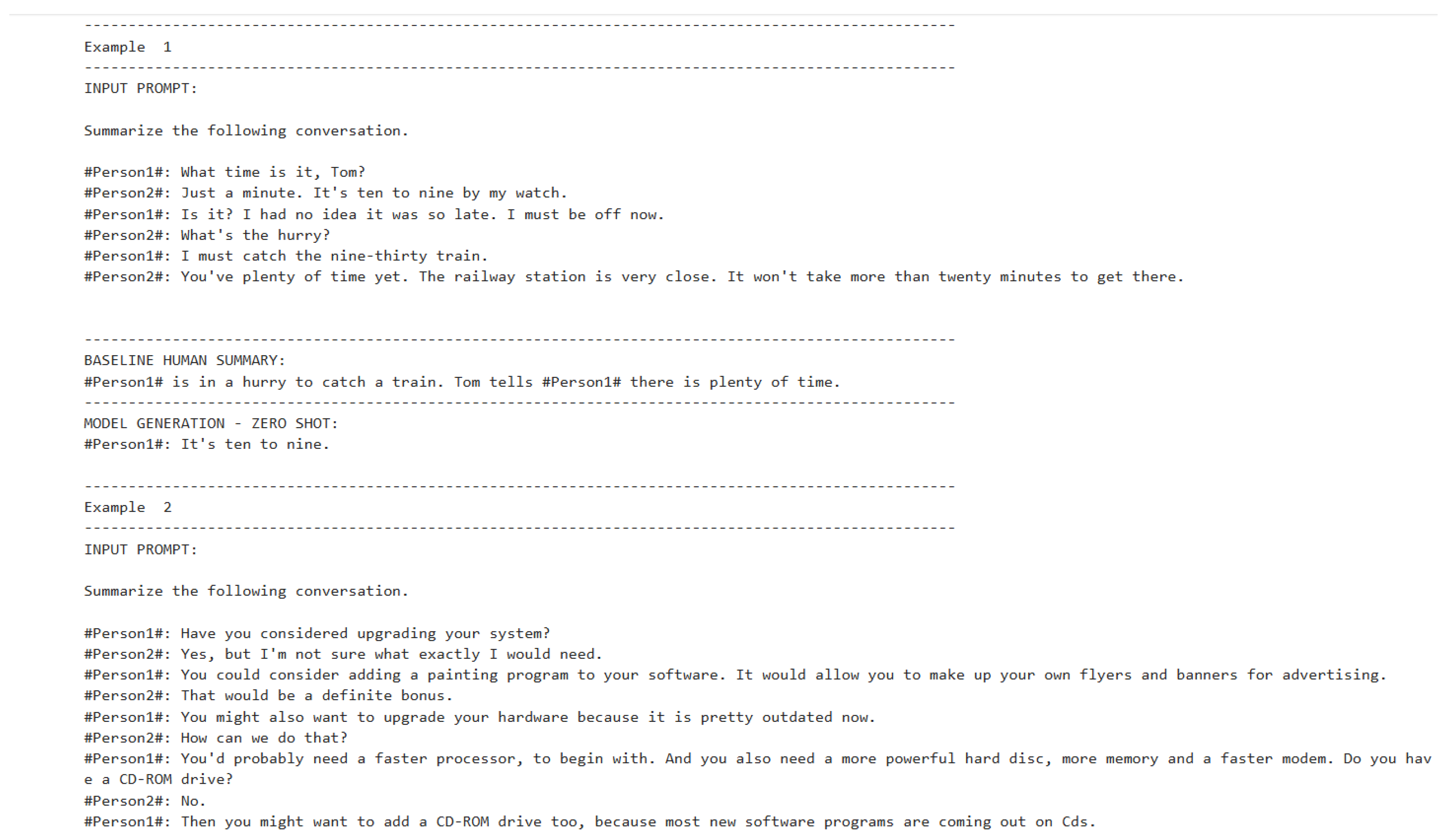

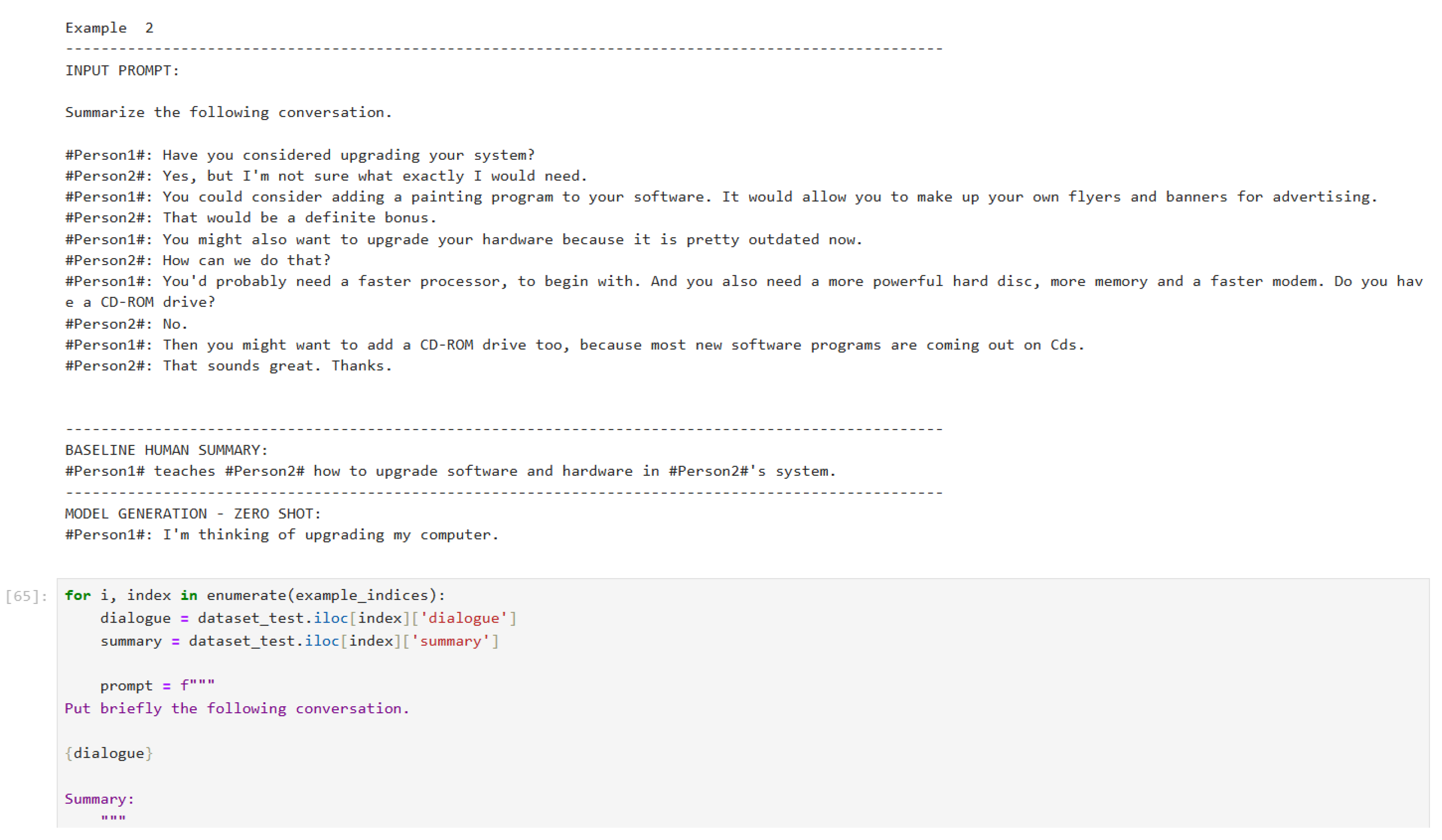

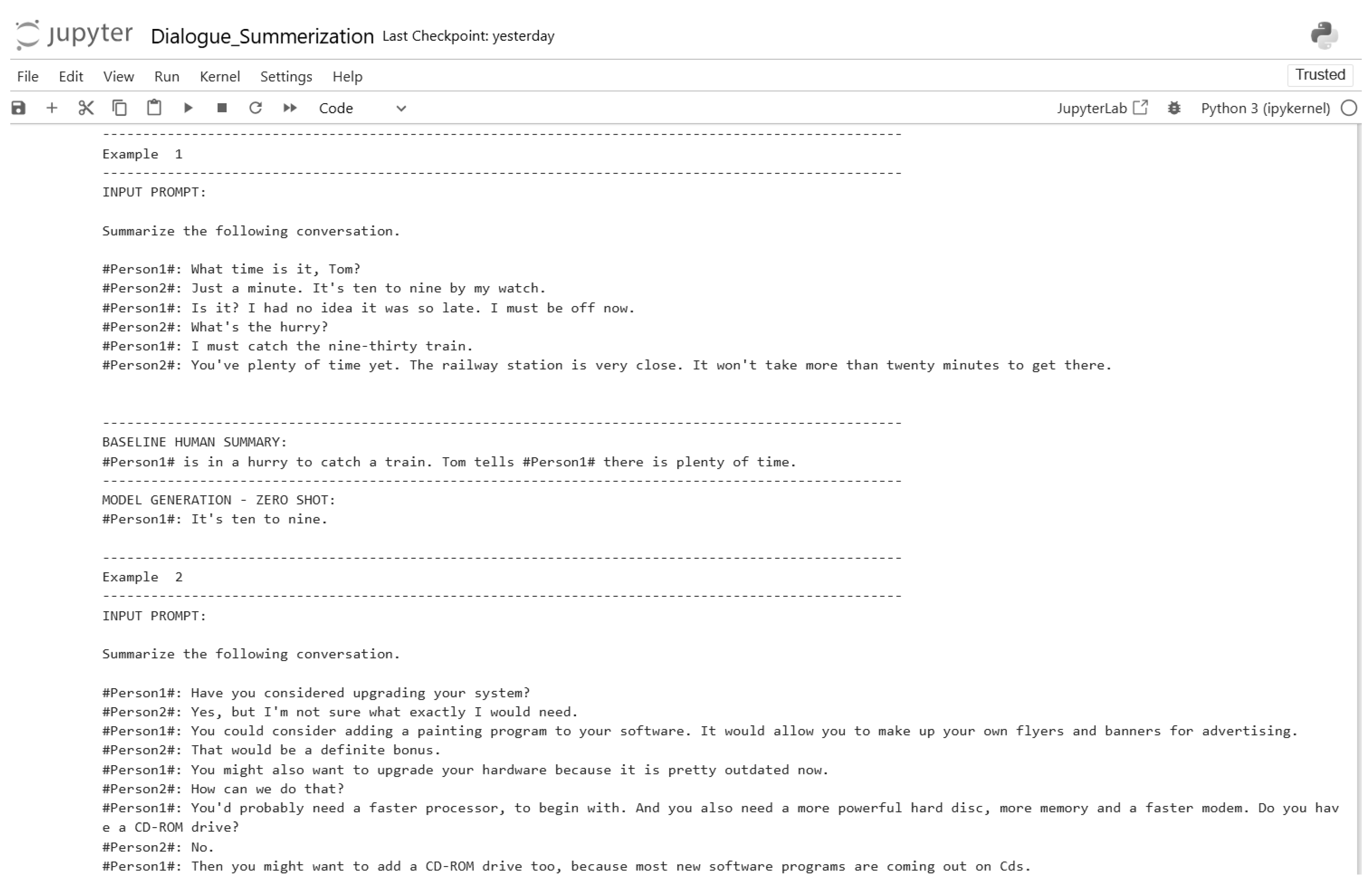

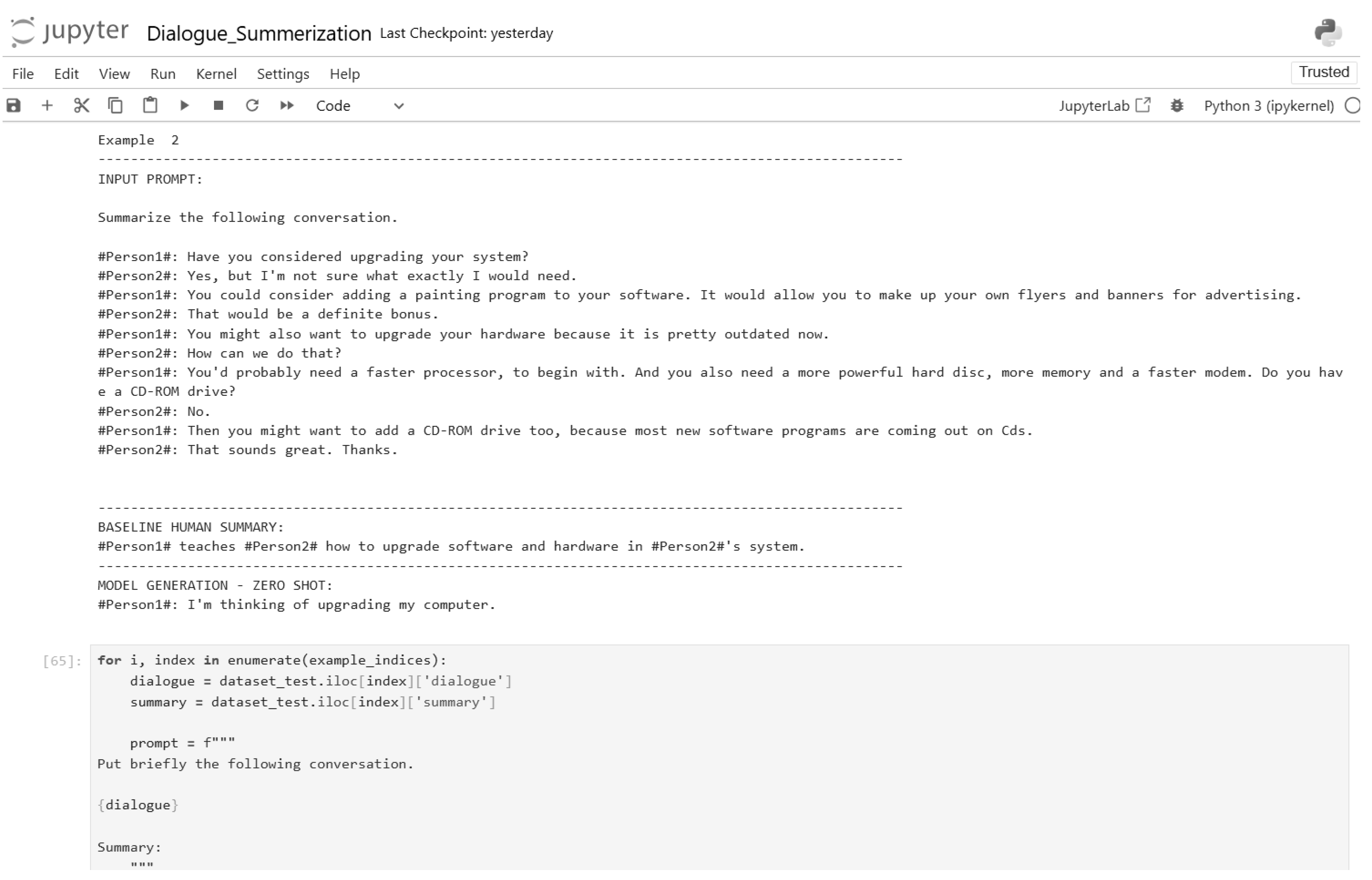

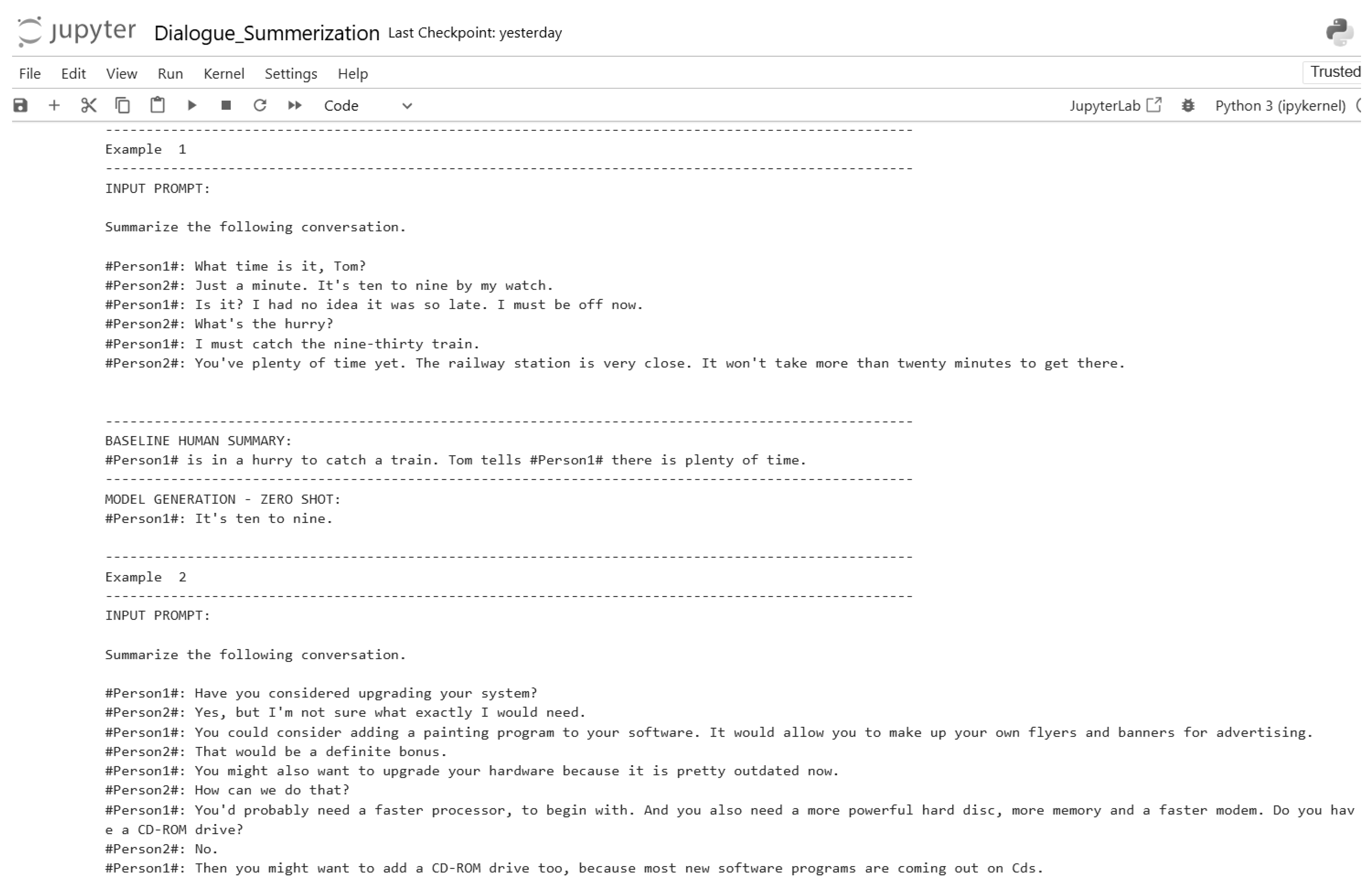

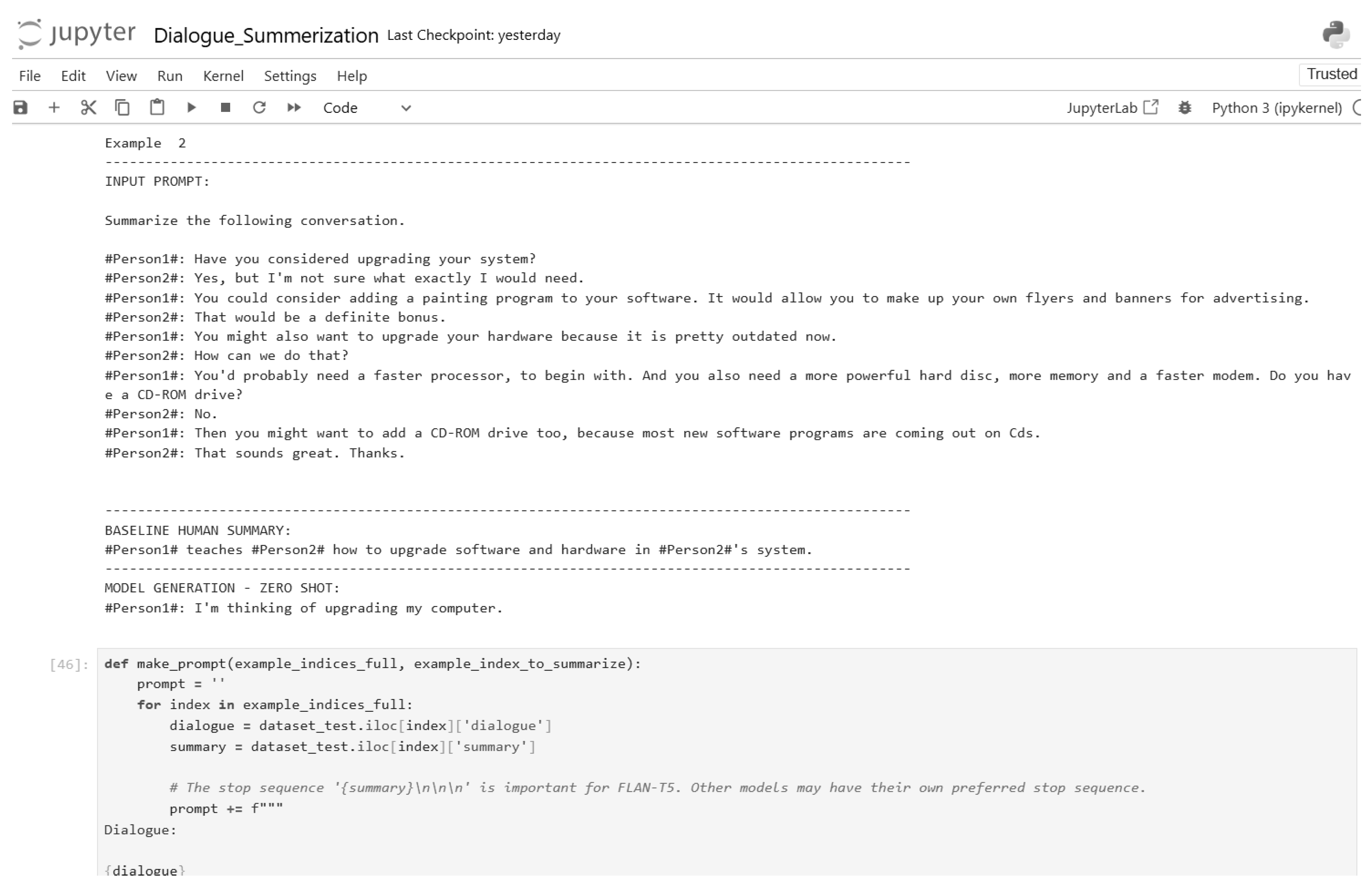

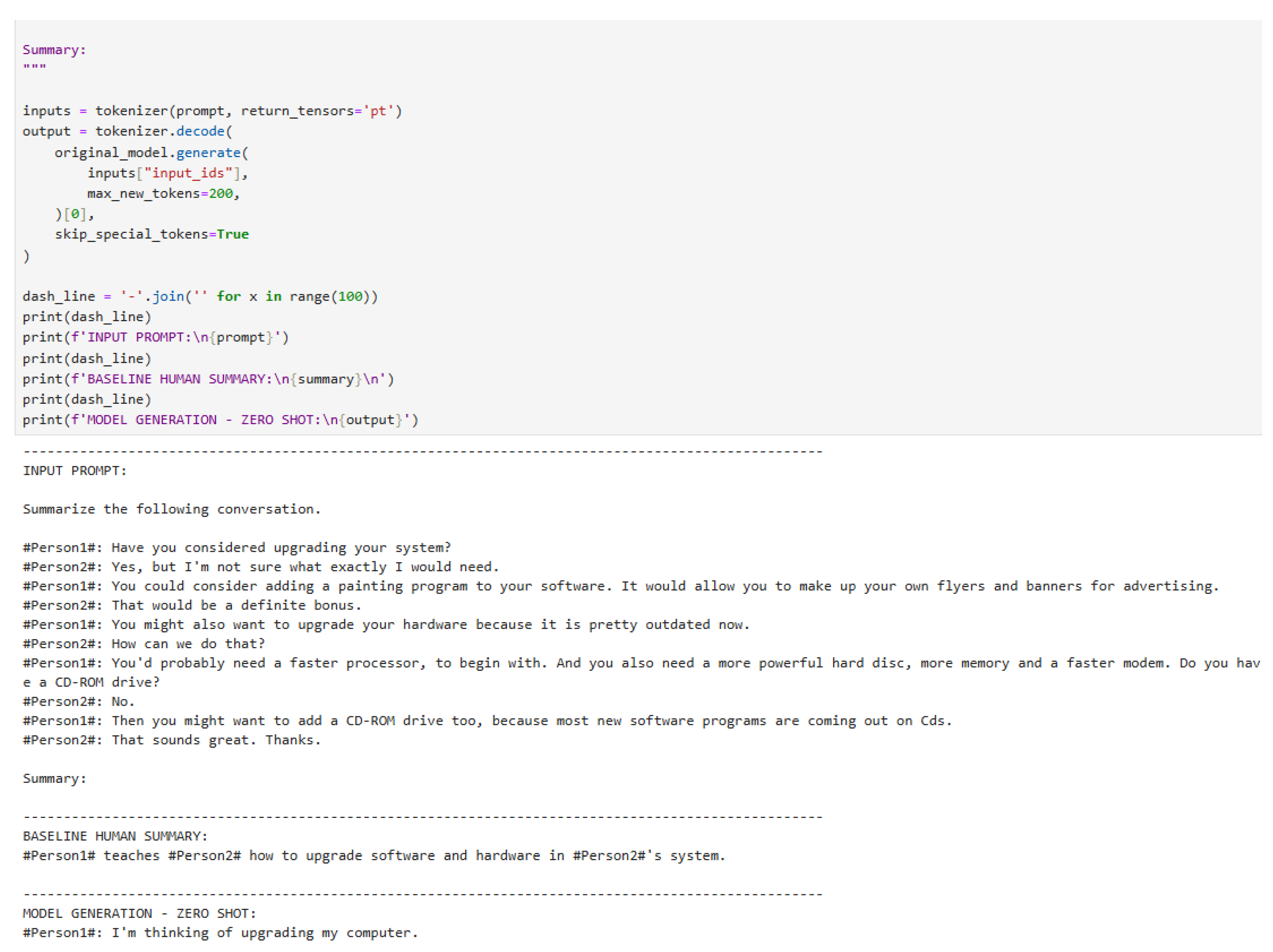

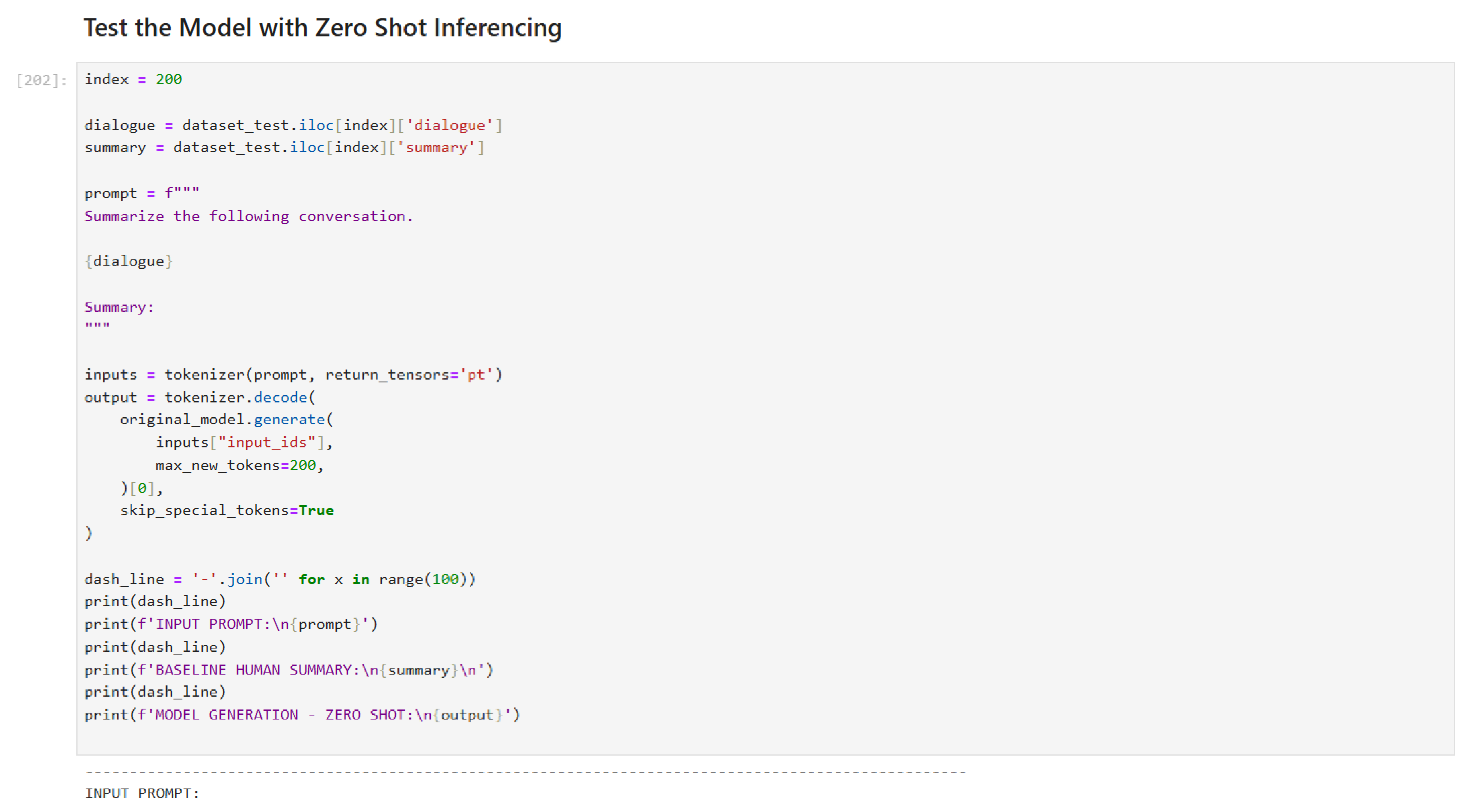

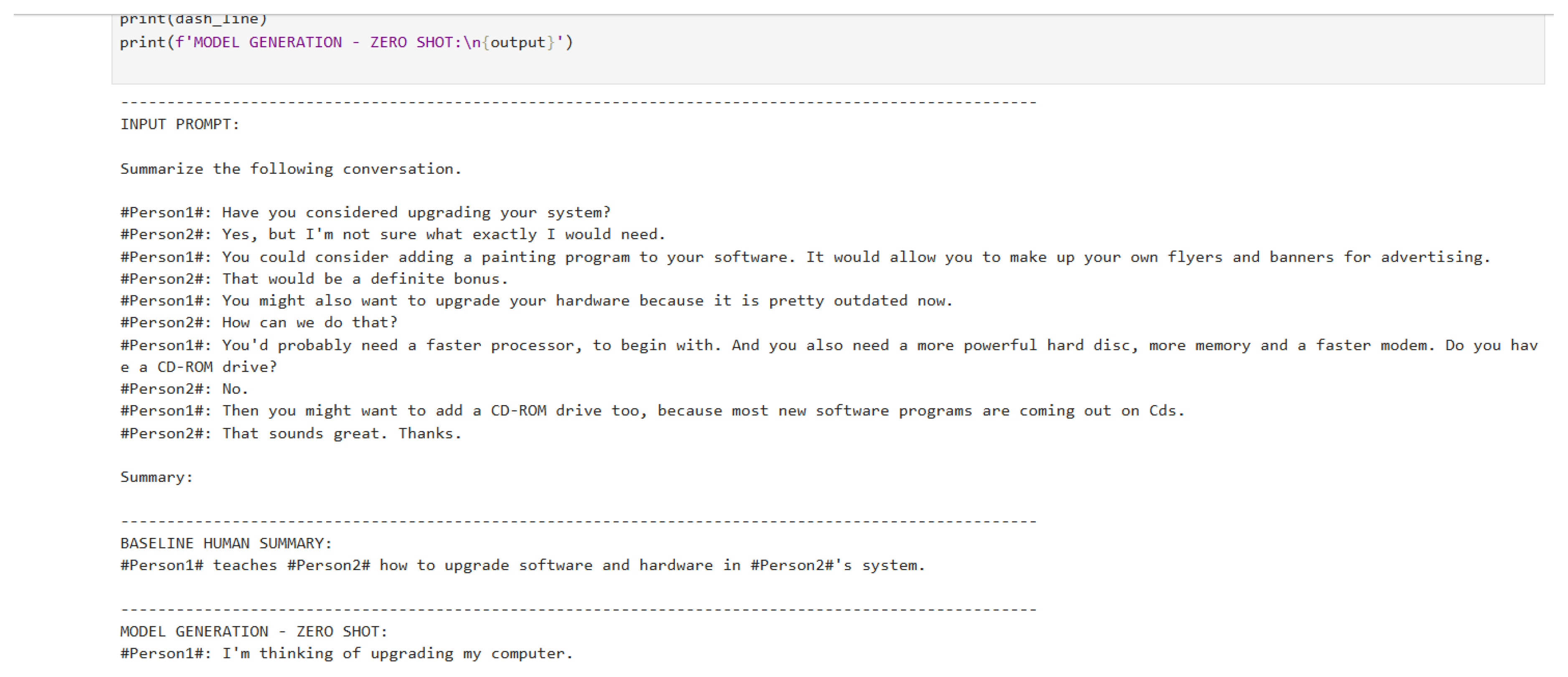

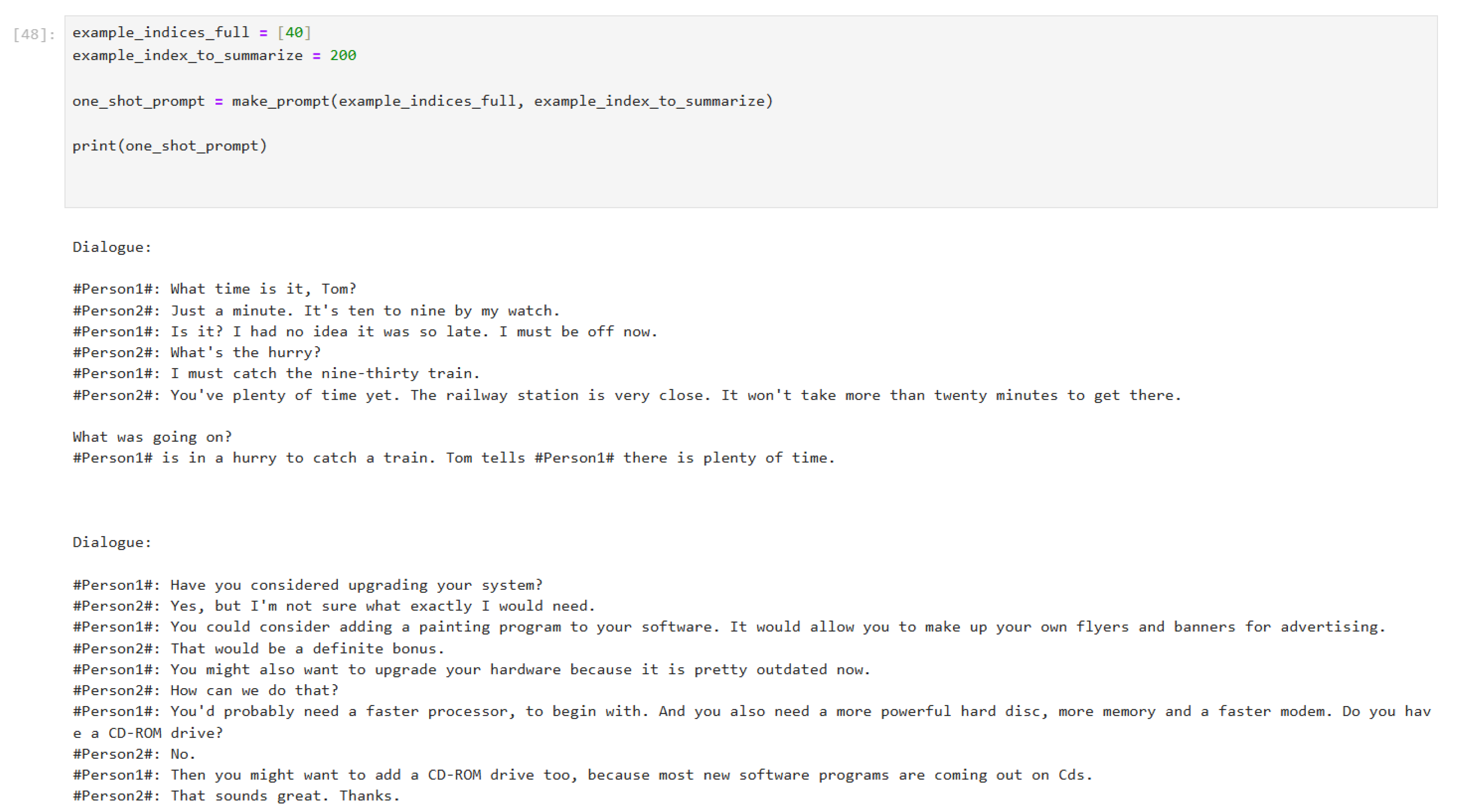

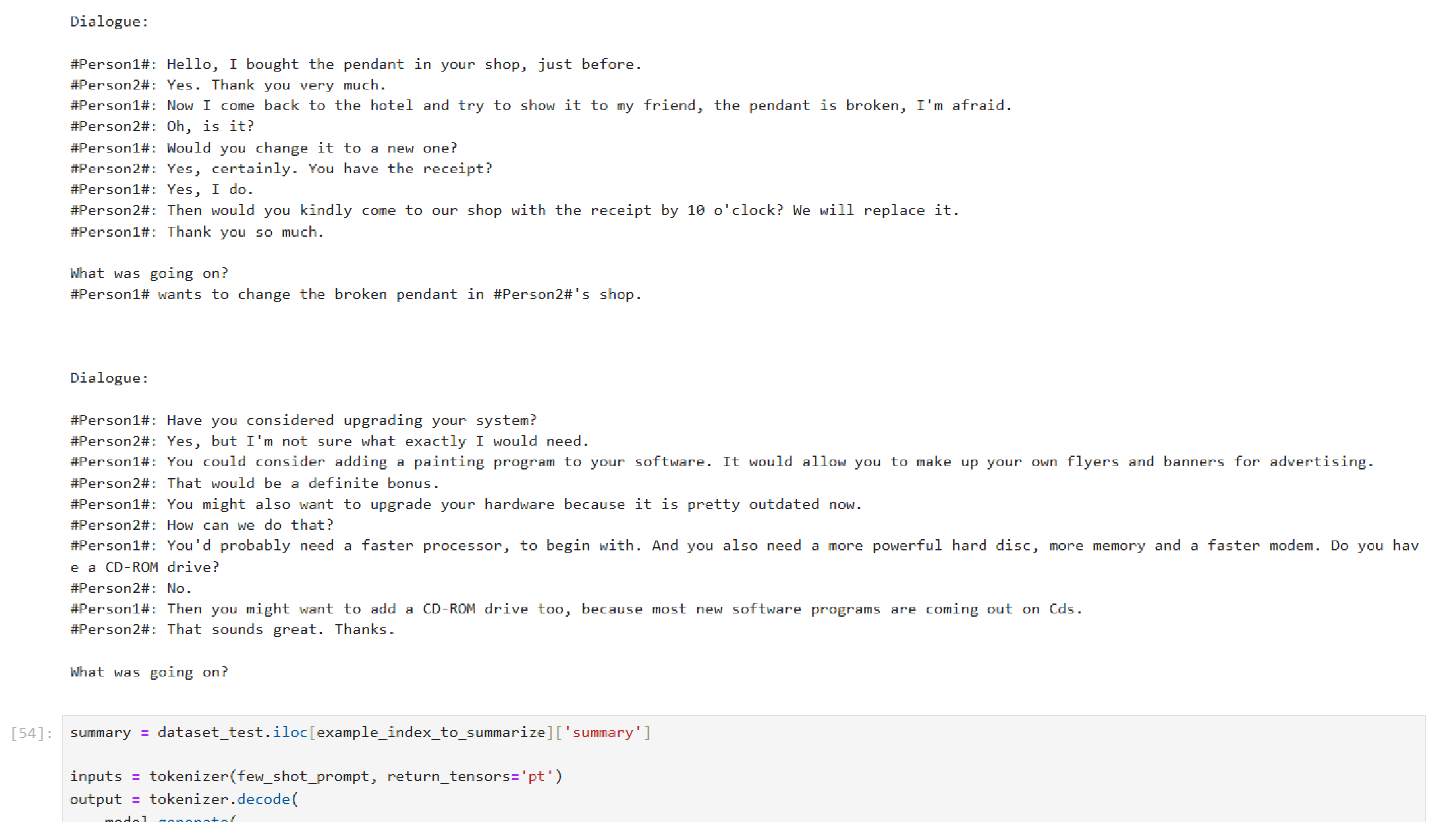

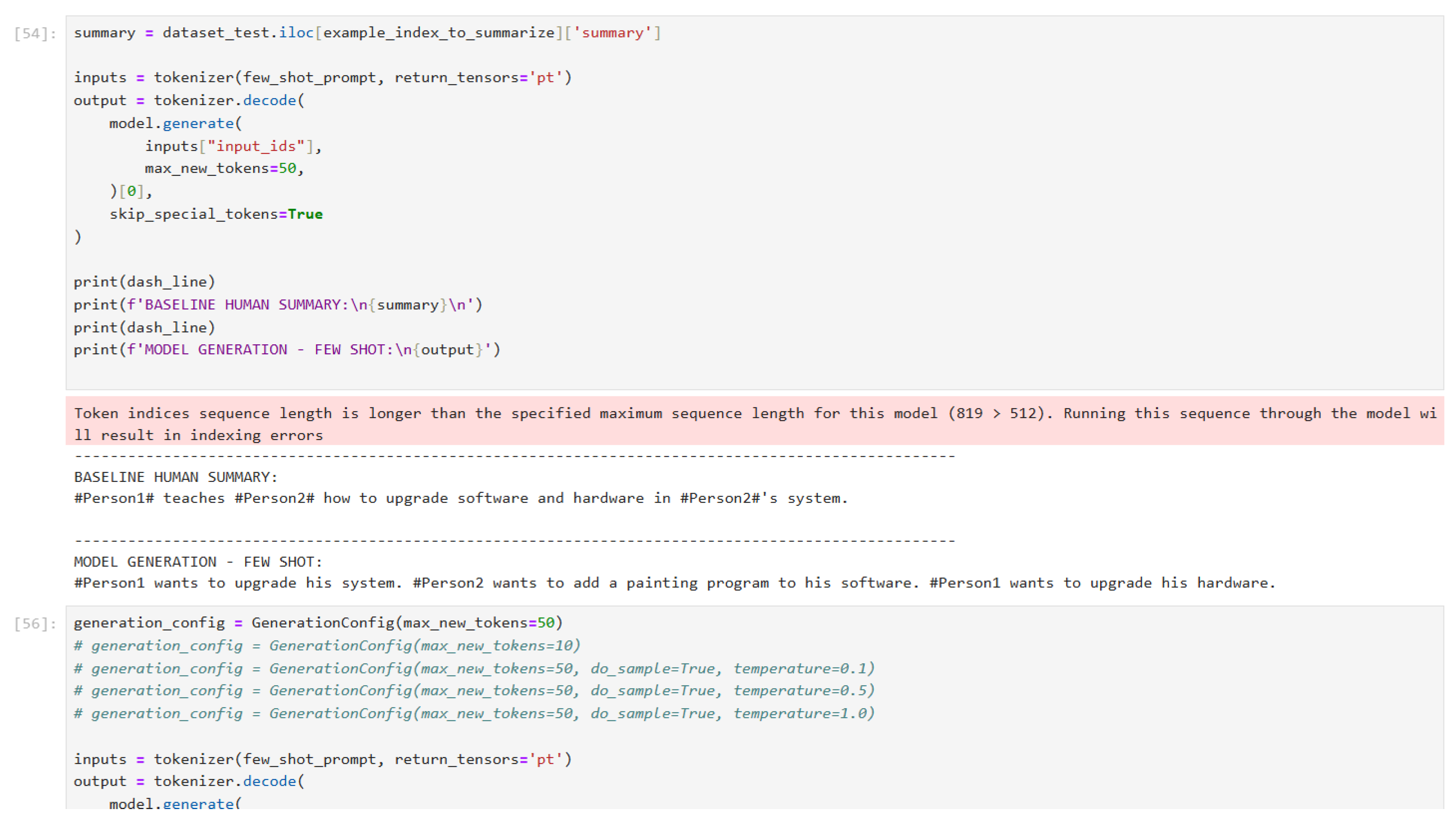

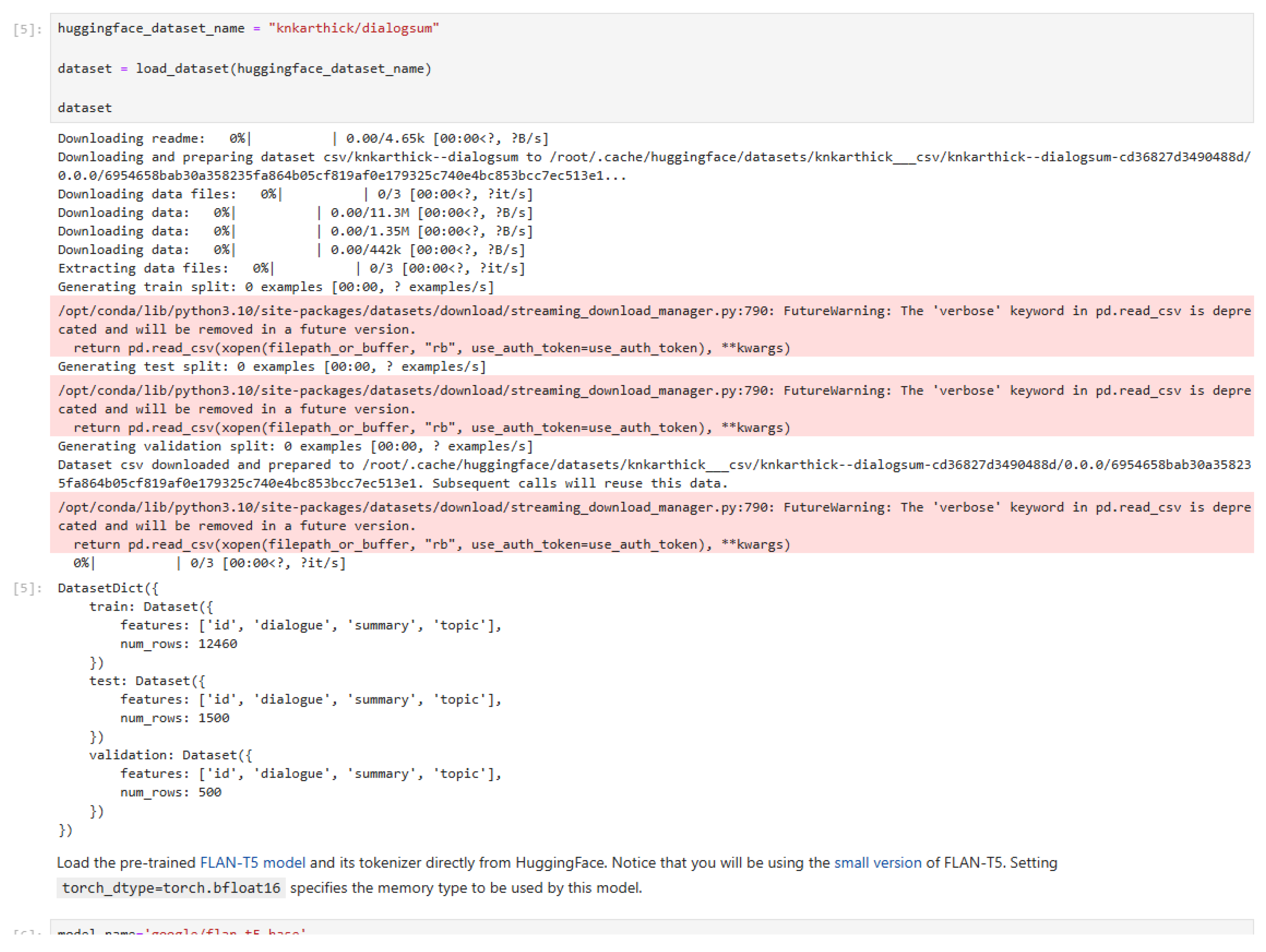

5. Case Study: Dialog Summarization Chatbot

In our research, we have used inference techniques such as zero-shot, one-shot, and few-shot to evaluate the model’s performance on dialogue summarization tasks. These techniques are demonstrated through various implementations, as shown in the figures below. Additionally, we have applied fine-tuning methods including LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning), Prompt Tuning, and Reinforcement Learning with PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) to enhance the model’s capabilities. The following figures illustrate the implementation details, code, and outputs of these techniques.

Figure 4.

Dialogue summarization without prompt engineering (Part 1).

Figure 4.

Dialogue summarization without prompt engineering (Part 1).

Figure 5.

Dialogue summarization without prompt engineering (Part 2).

Figure 5.

Dialogue summarization without prompt engineering (Part 2).

Figure 6.

Encode and decode string implementation.

Figure 6.

Encode and decode string implementation.

Figure 7.

Model generation without prompt engineering (Part 1).

Figure 7.

Model generation without prompt engineering (Part 1).

Figure 8.

Model generation without prompt engineering (Part 2).

Figure 8.

Model generation without prompt engineering (Part 2).

Figure 9.

Zero-shot inference instruction prompt.

Figure 9.

Zero-shot inference instruction prompt.

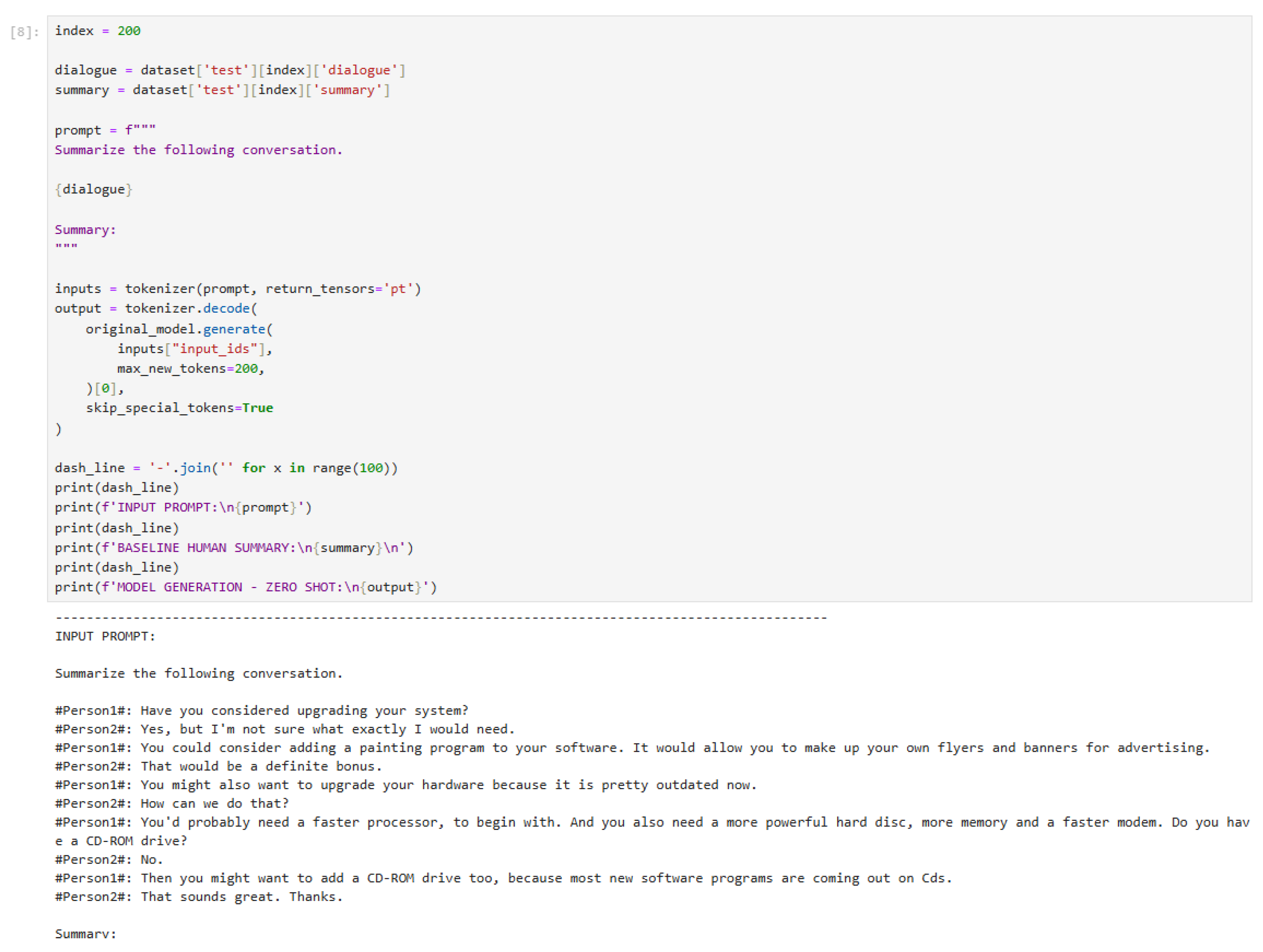

Figure 10.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 1).

Figure 10.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 1).

Figure 11.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 2).

Figure 11.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 2).

Figure 12.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 3).

Figure 12.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 3).

Figure 13.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 4).

Figure 13.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 4).

Figure 14.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 5).

Figure 14.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 5).

Figure 15.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 6).

Figure 15.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 6).

Figure 16.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 7).

Figure 16.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 7).

Figure 17.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 8).

Figure 17.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 8).

Figure 18.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 9).

Figure 18.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 9).

Figure 19.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 10).

Figure 19.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 10).

Figure 20.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 11).

Figure 20.

Zero-shot inference code (Part 11).

Figure 21.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 1).

Figure 21.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 1).

Figure 22.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 2).

Figure 22.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 2).

Figure 23.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 3).

Figure 23.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 3).

Figure 24.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 4).

Figure 24.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 4).

Figure 25.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 5).

Figure 25.

Zero-shot inference input and output (Part 5).

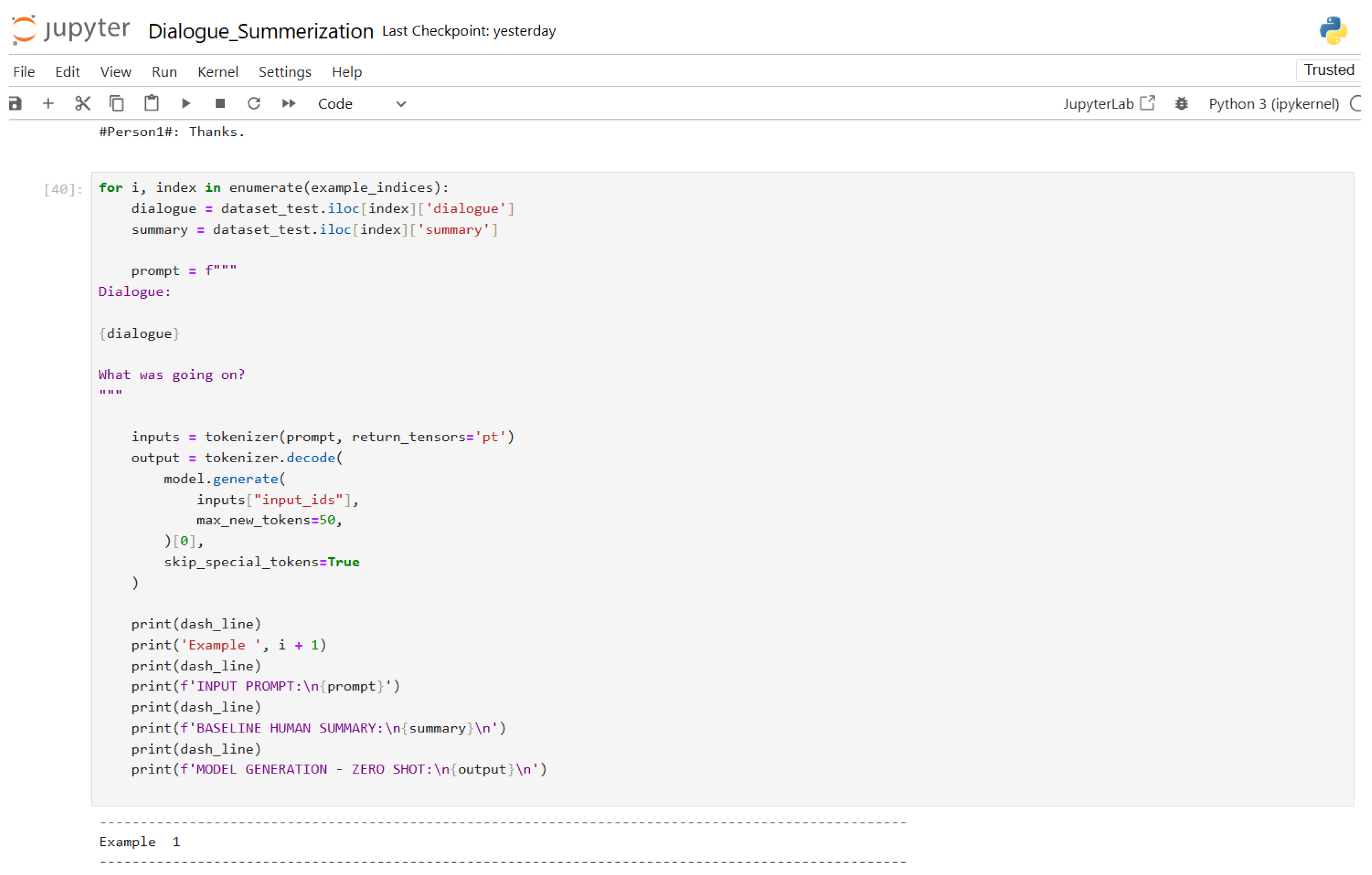

Figure 26.

Zero-shot inference testing (Part 1).

Figure 26.

Zero-shot inference testing (Part 1).

Figure 27.

Zero-shot inference testing (Part 2).

Figure 27.

Zero-shot inference testing (Part 2).

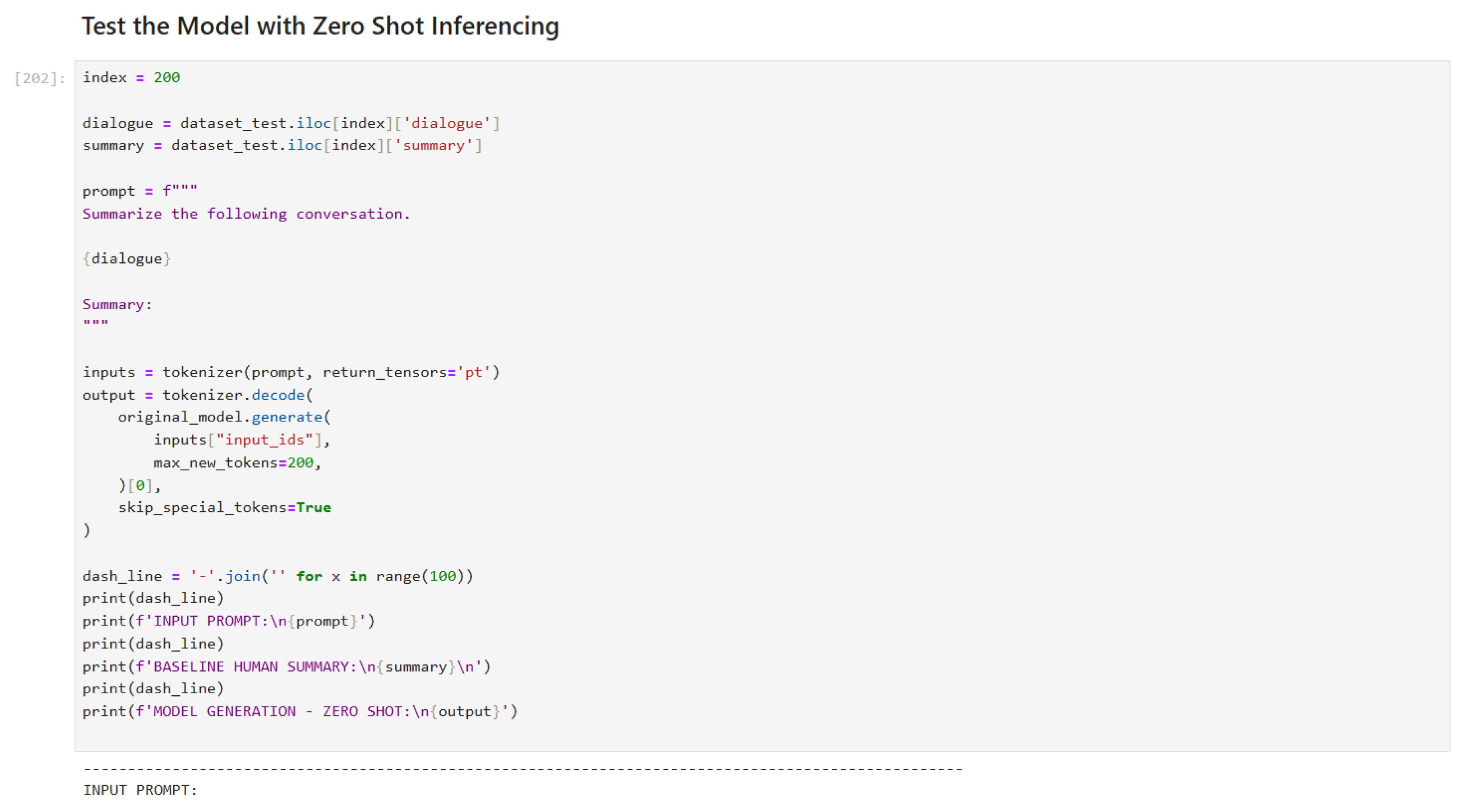

Figure 28.

Testing model with zero-shot inference (Part 1).

Figure 28.

Testing model with zero-shot inference (Part 1).

Figure 29.

Testing model with zero-shot inference (Part 2).

Figure 29.

Testing model with zero-shot inference (Part 2).

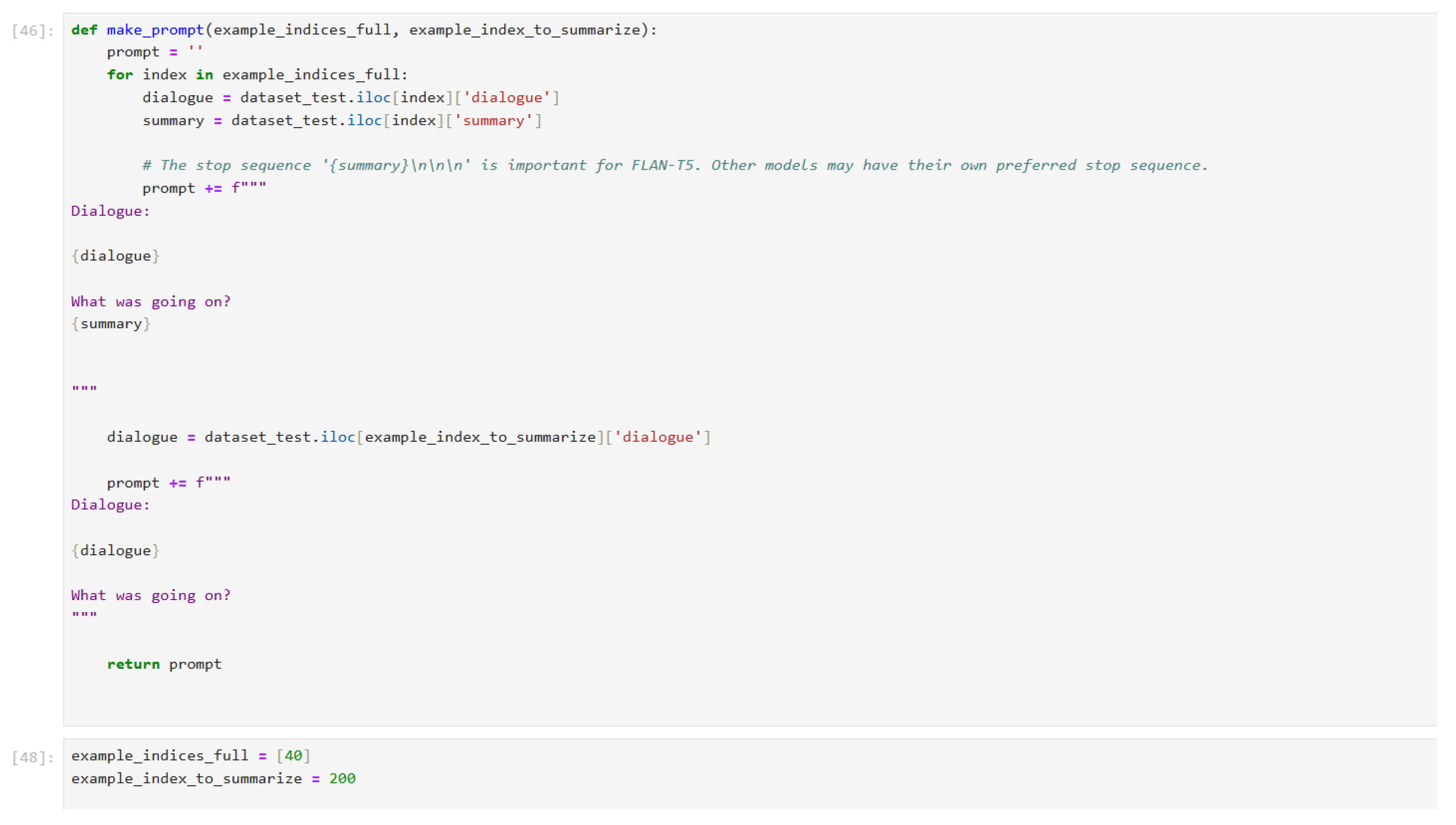

Figure 30.

One-shot inference code (Part 1).

Figure 30.

One-shot inference code (Part 1).

Figure 31.

One-shot inference code (Part 2).

Figure 31.

One-shot inference code (Part 2).

Figure 32.

One-shot inference code (Part 3).

Figure 32.

One-shot inference code (Part 3).

Figure 33.

One-shot inference code (Part 4).

Figure 33.

One-shot inference code (Part 4).

Figure 34.

One-shot inference input and output (Part 1).

Figure 34.

One-shot inference input and output (Part 1).

Figure 35.

One-shot inference input and output (Part 2).

Figure 35.

One-shot inference input and output (Part 2).

Figure 36.

Loading the dataset for training.

Figure 36.

Loading the dataset for training.

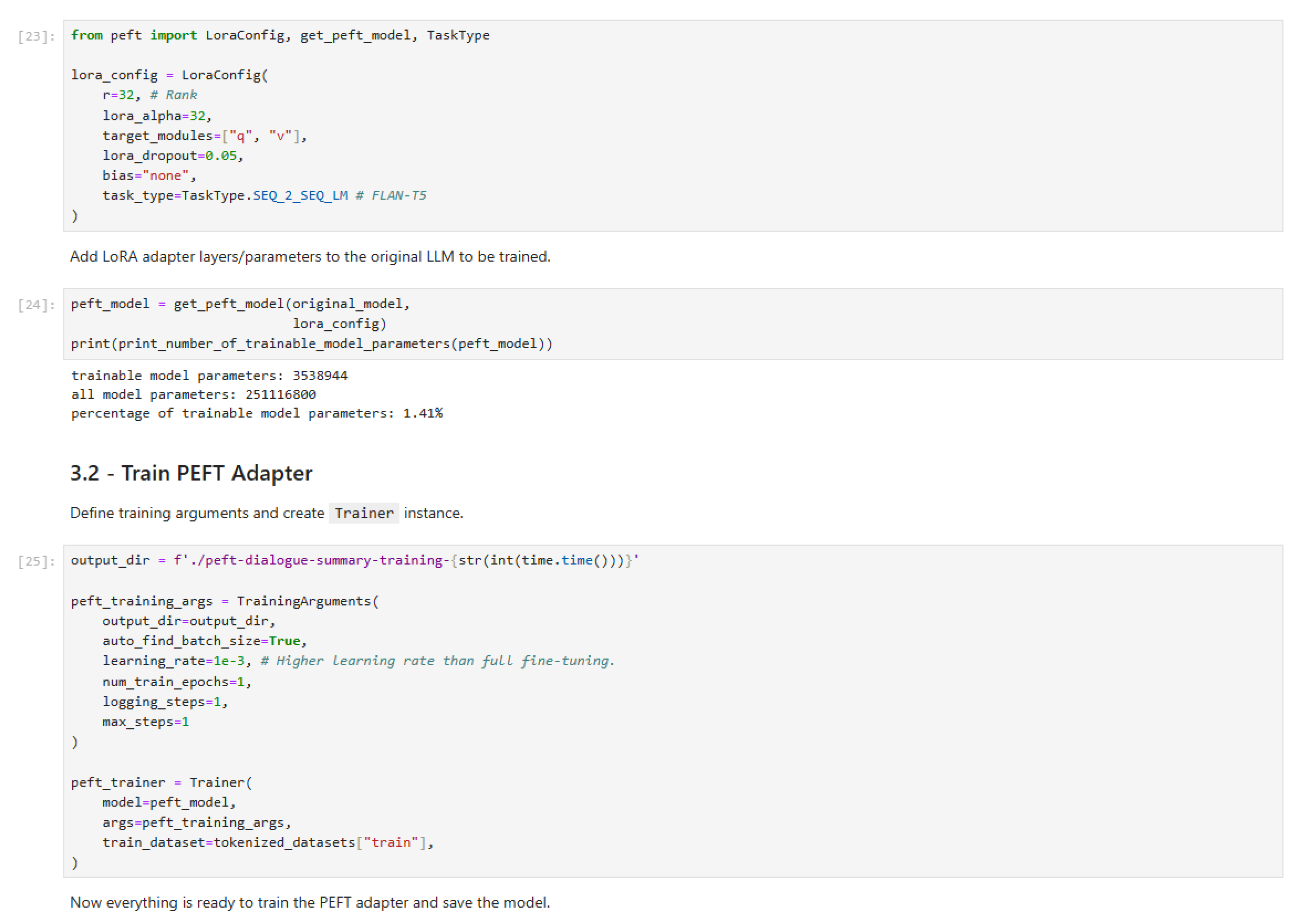

Figure 37.

LoRA and PEFT training implementation.

Figure 37.

LoRA and PEFT training implementation.

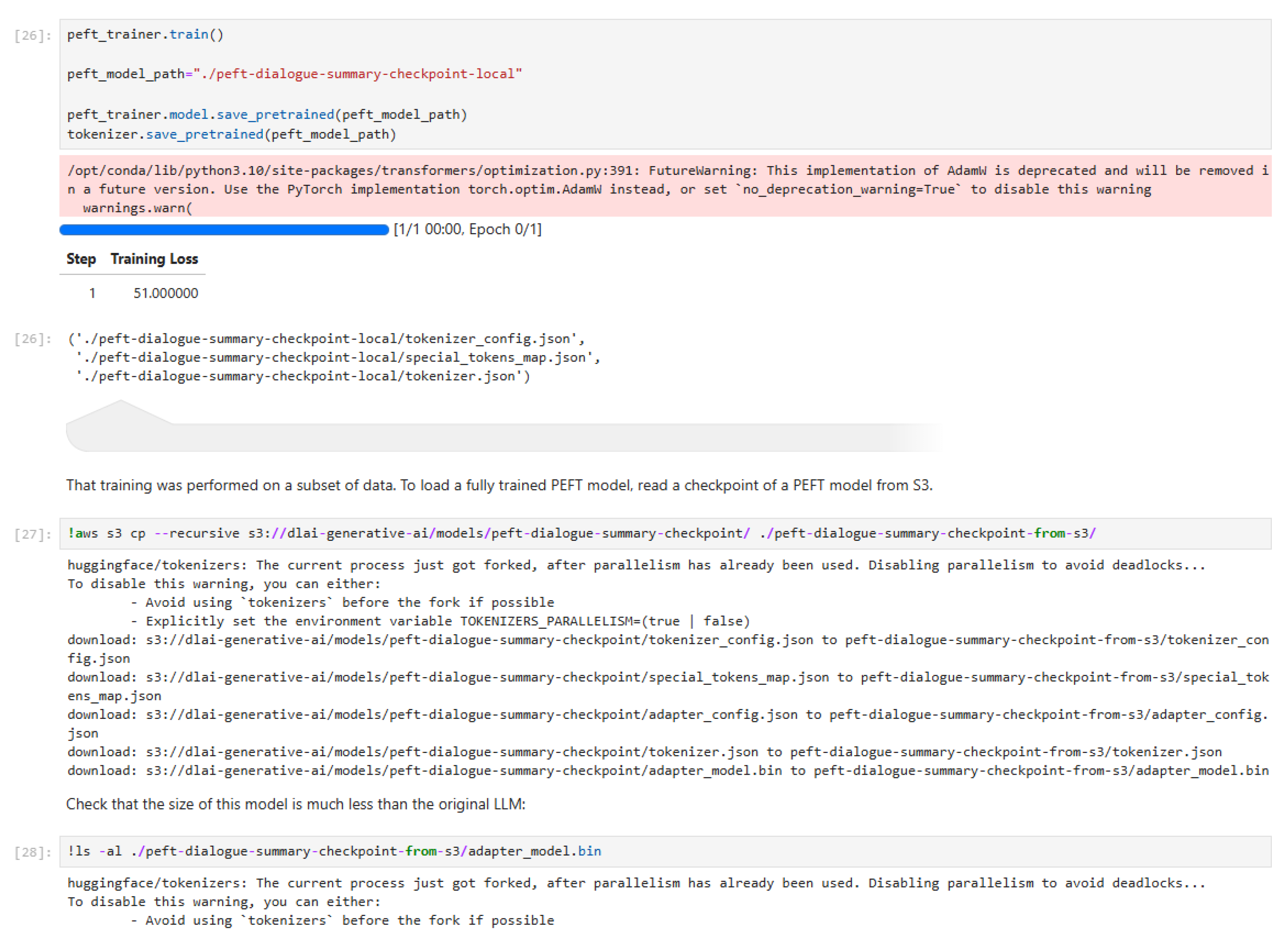

Figure 38.

PEFT training implementation.

Figure 38.

PEFT training implementation.

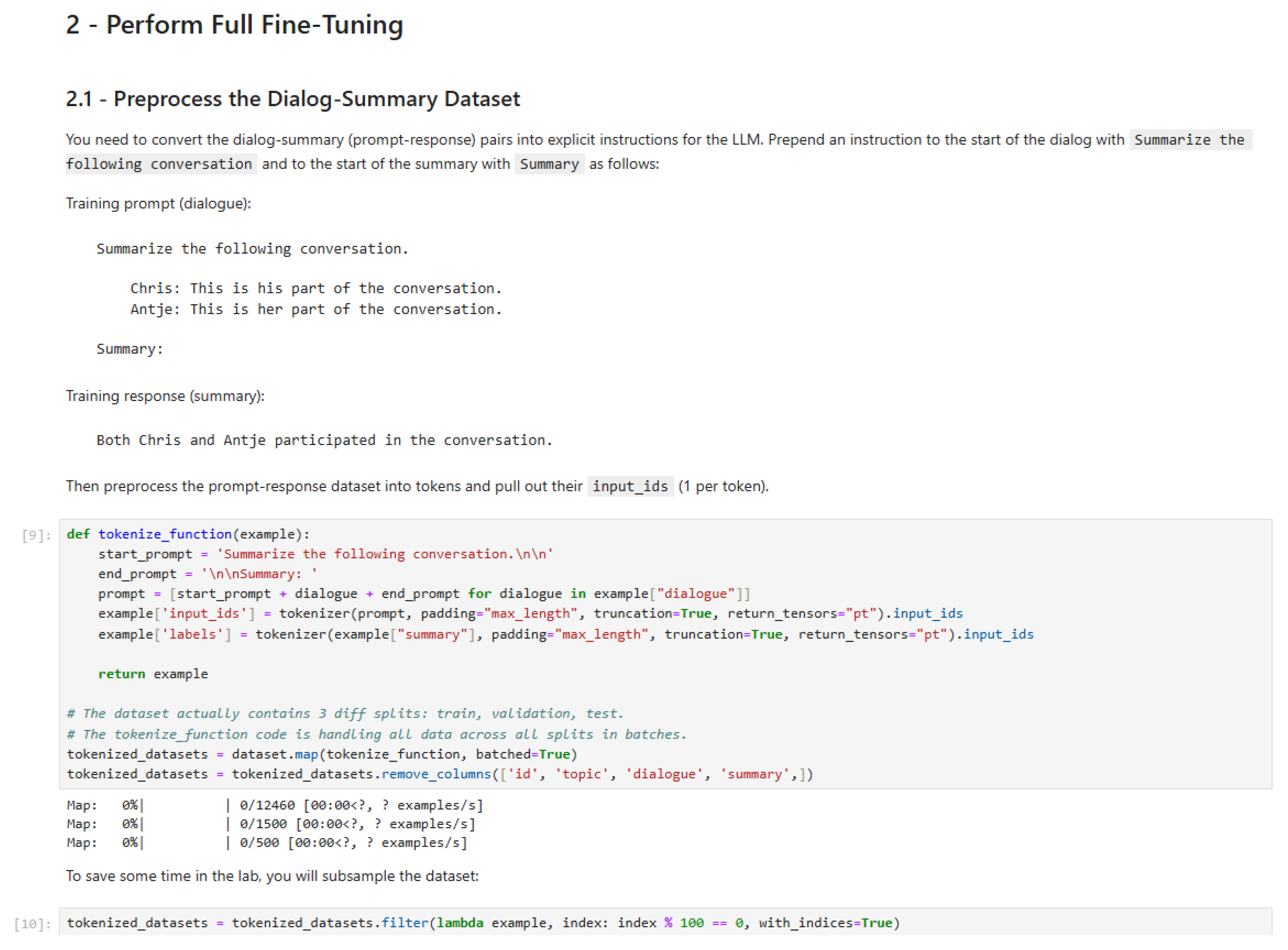

Figure 39.

Performing full fine-tuning (Part 1).

Figure 39.

Performing full fine-tuning (Part 1).

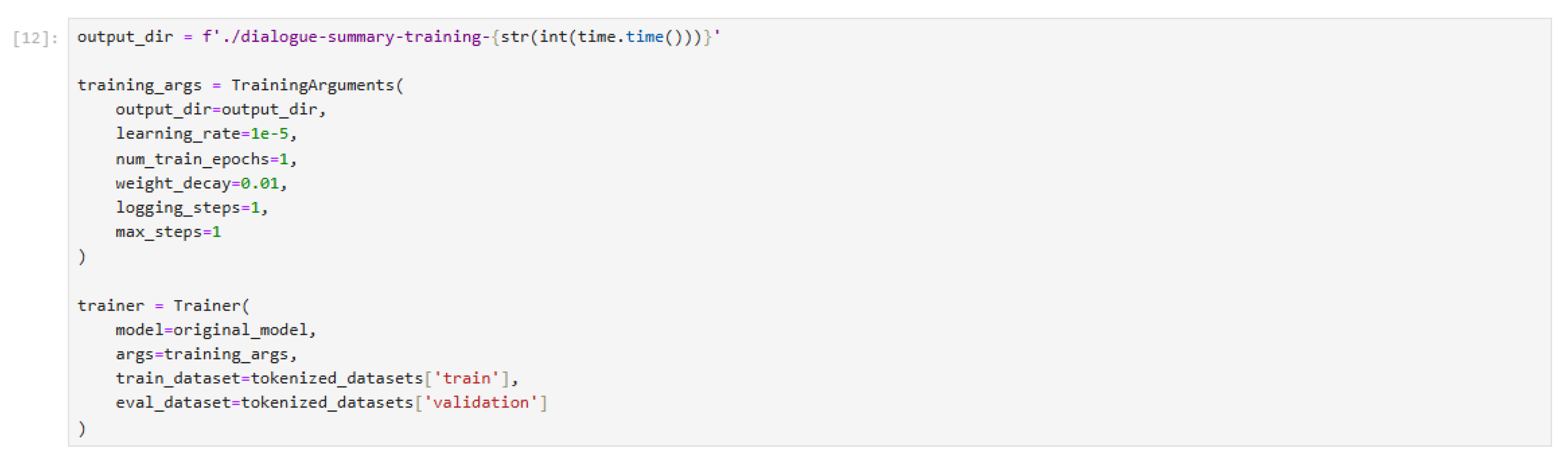

Figure 40.

Performing full fine-tuning (Part 2).

Figure 40.

Performing full fine-tuning (Part 2).

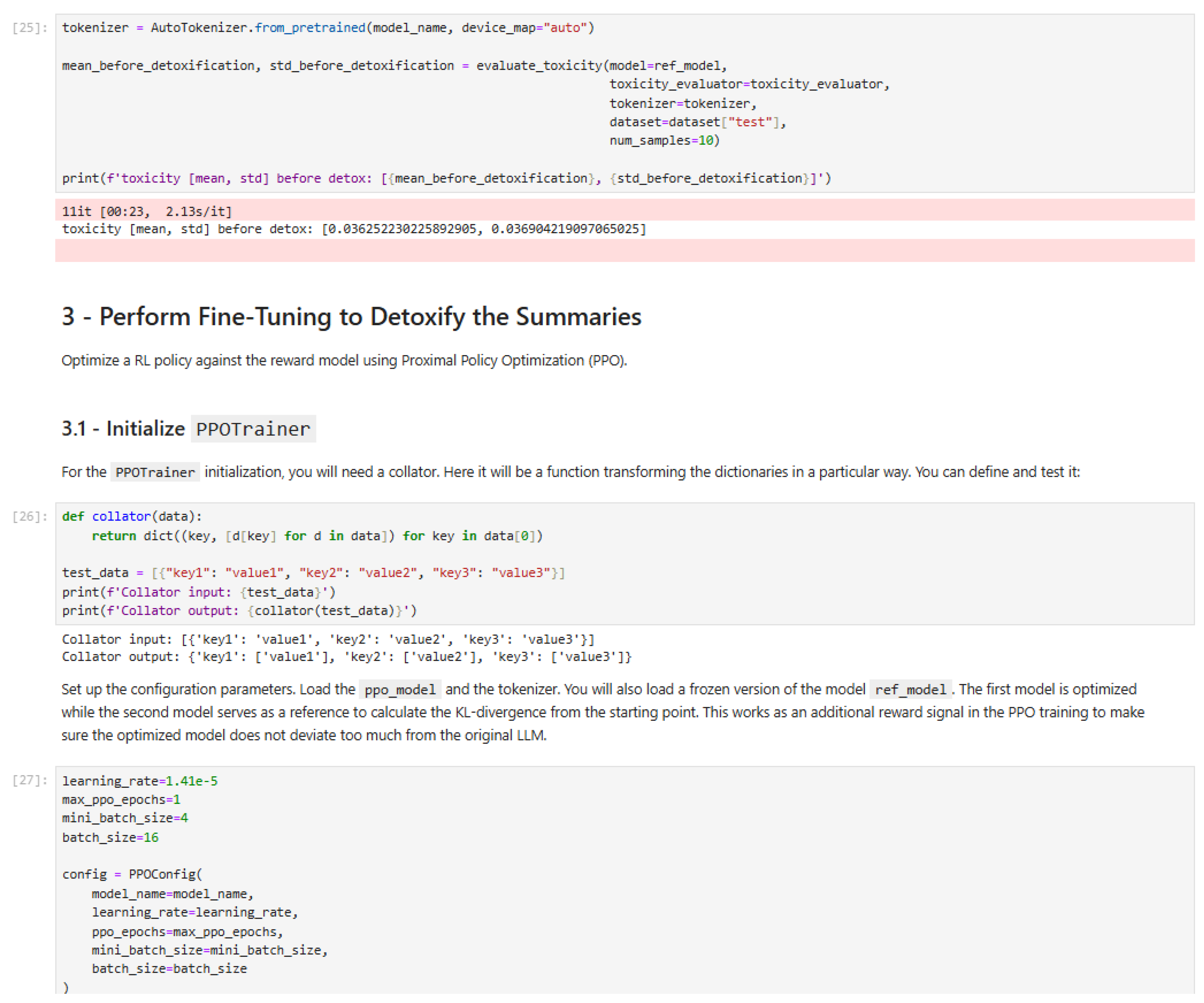

Figure 41.

PPO fine-tuning implementation.

Figure 41.

PPO fine-tuning implementation.

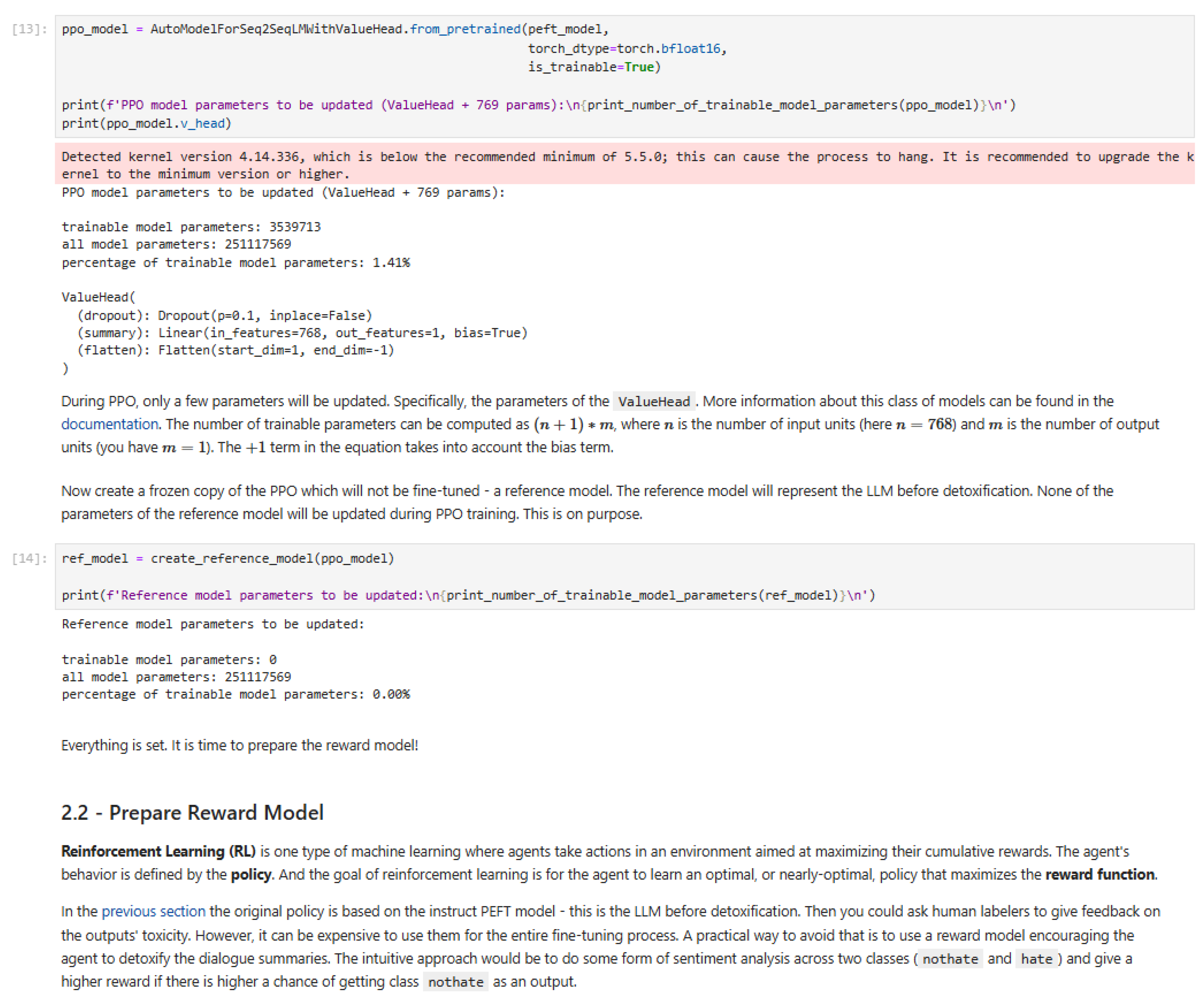

Figure 42.

PPO model implementation.

Figure 42.

PPO model implementation.

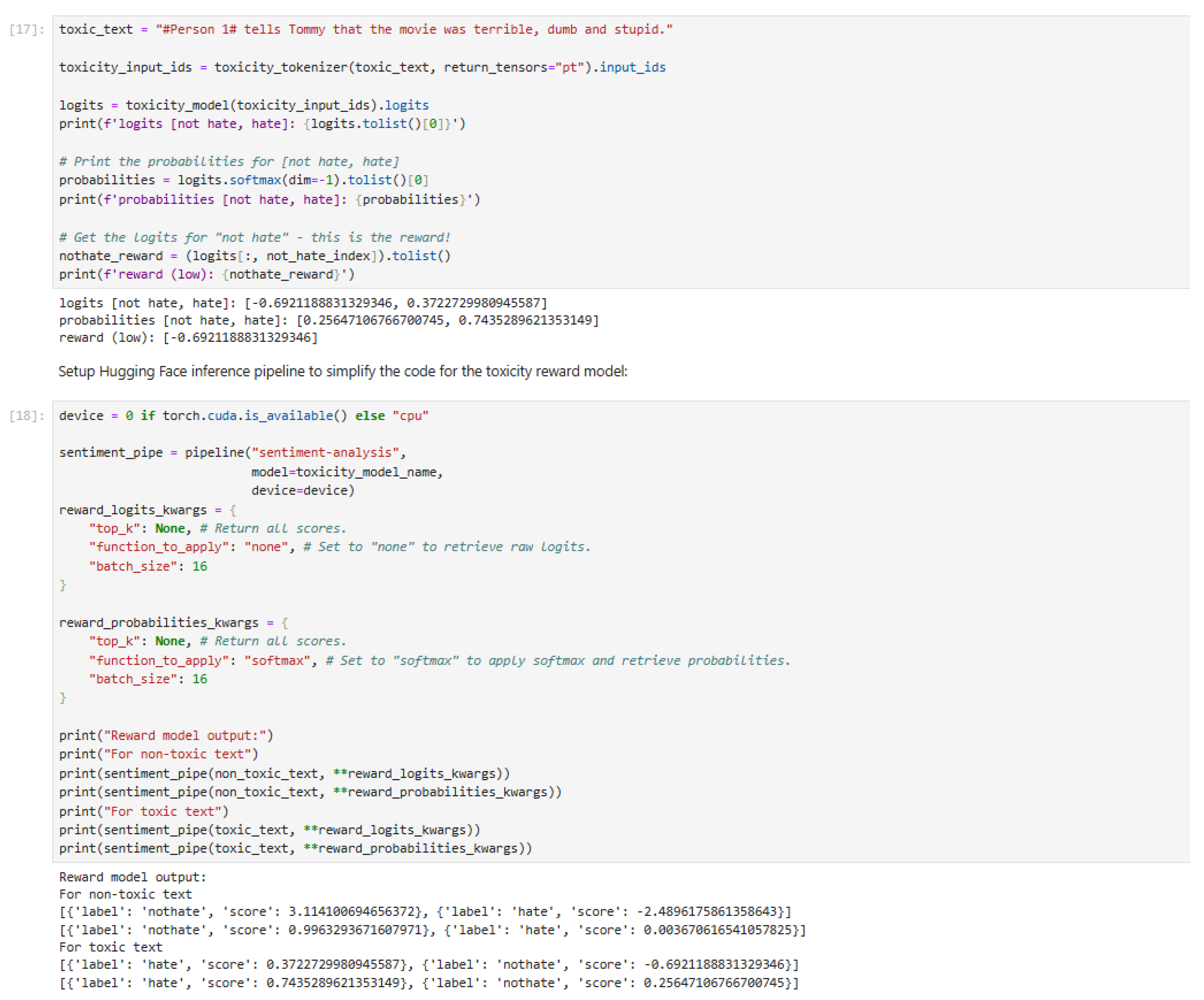

Figure 43.

Reward model output for PPO fine-tuning.

Figure 43.

Reward model output for PPO fine-tuning.

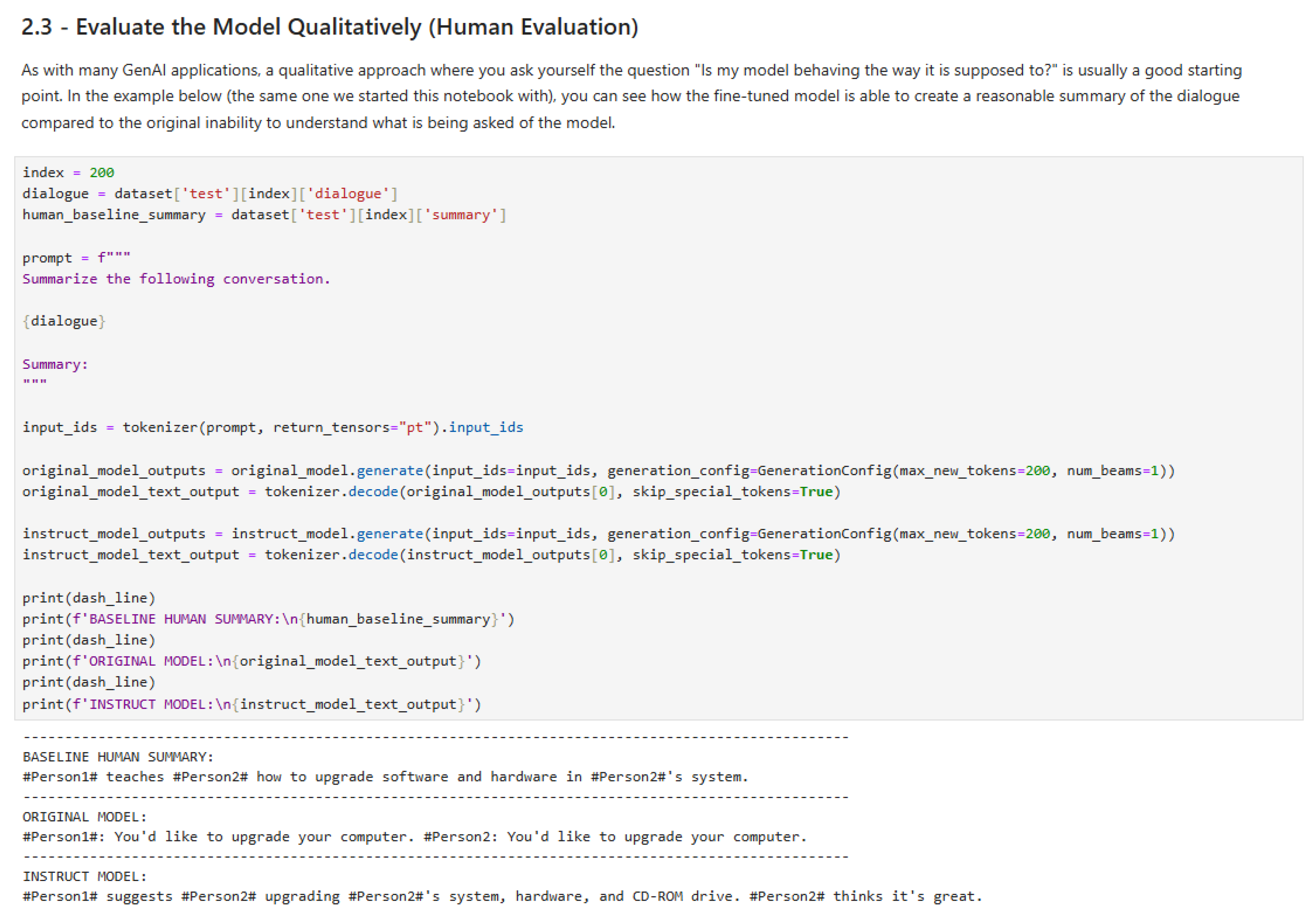

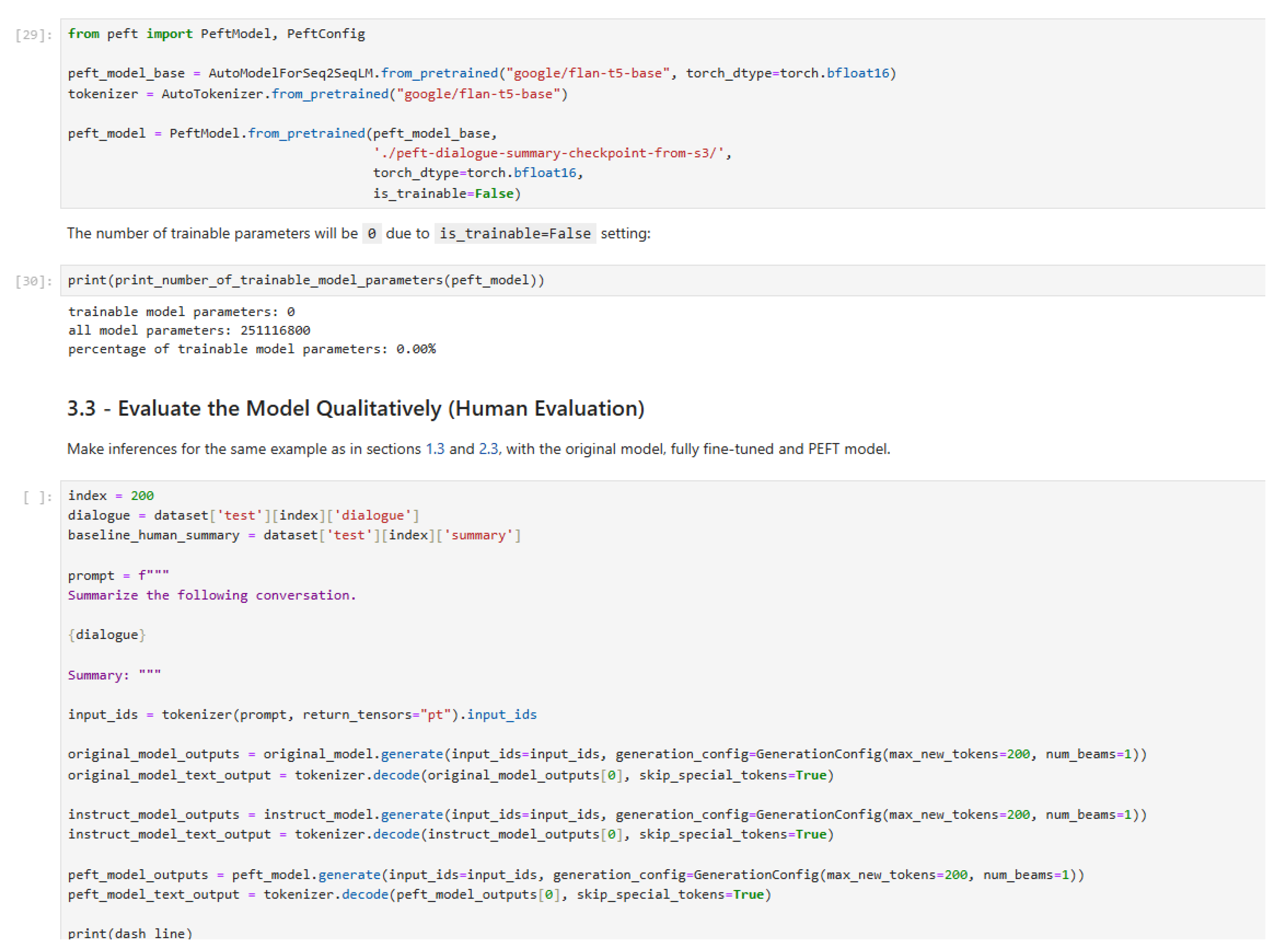

Figure 44.

Qualitative evaluation of the model (Part 1).

Figure 44.

Qualitative evaluation of the model (Part 1).

Figure 45.

Qualitative evaluation of the model (Part 2).

Figure 45.

Qualitative evaluation of the model (Part 2).

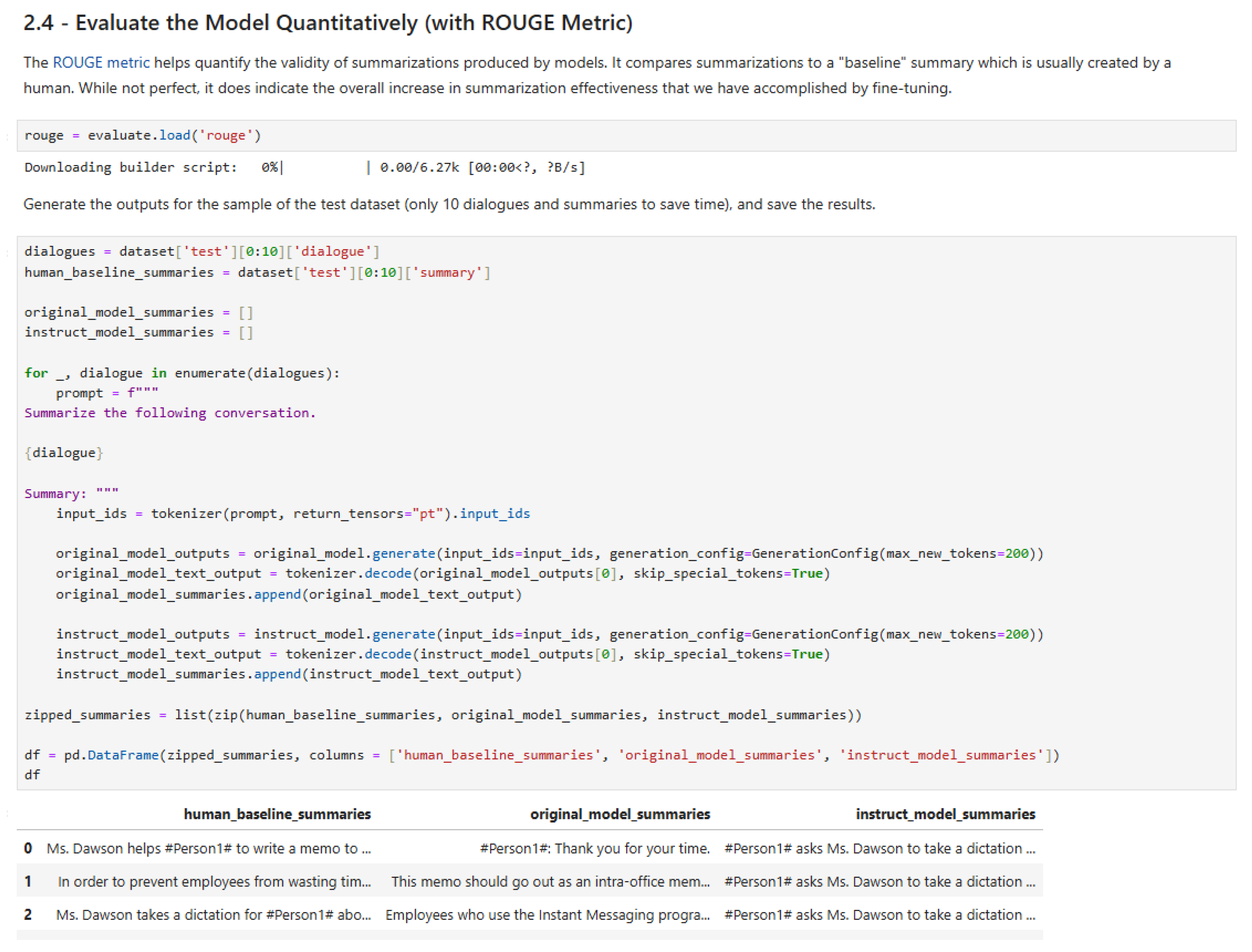

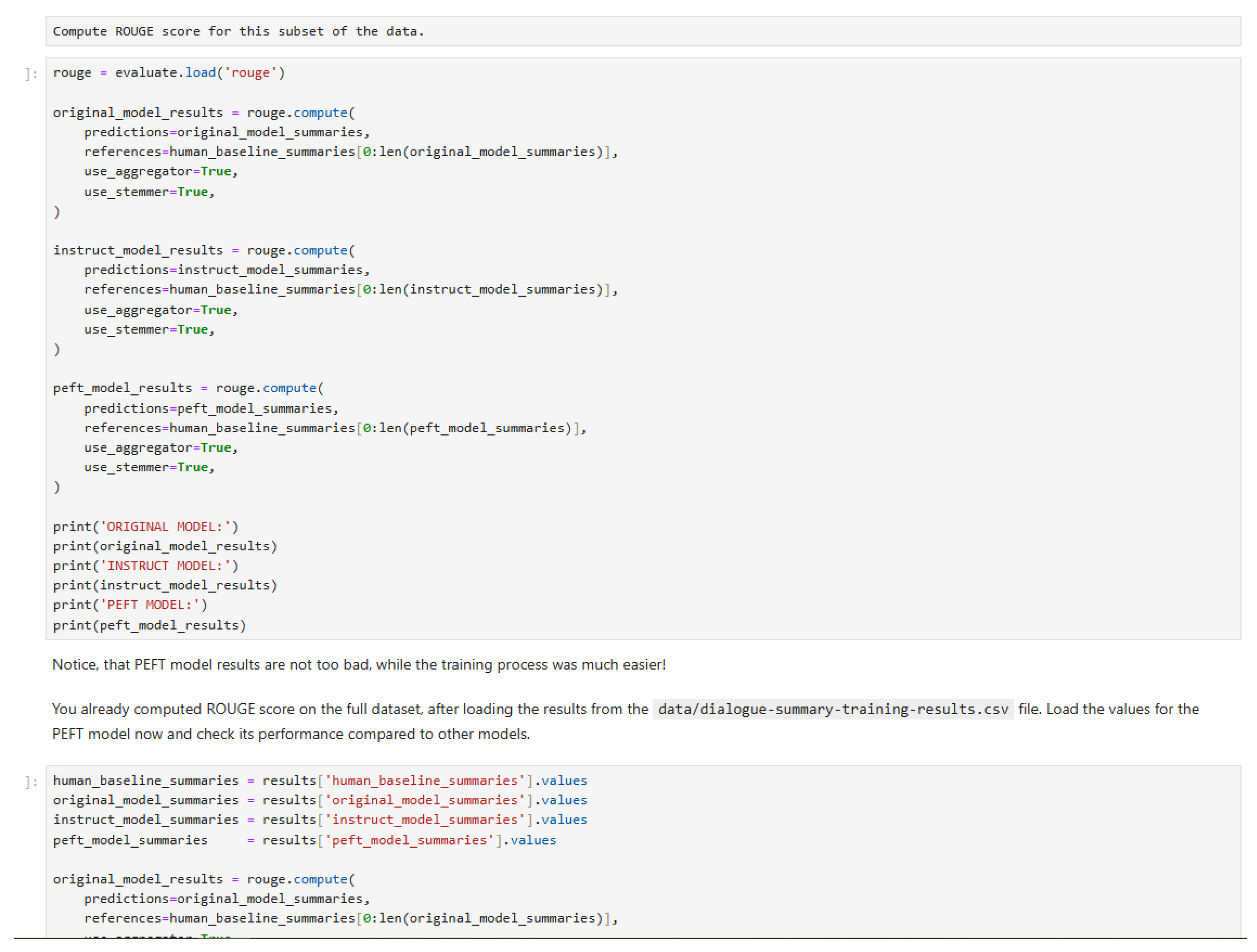

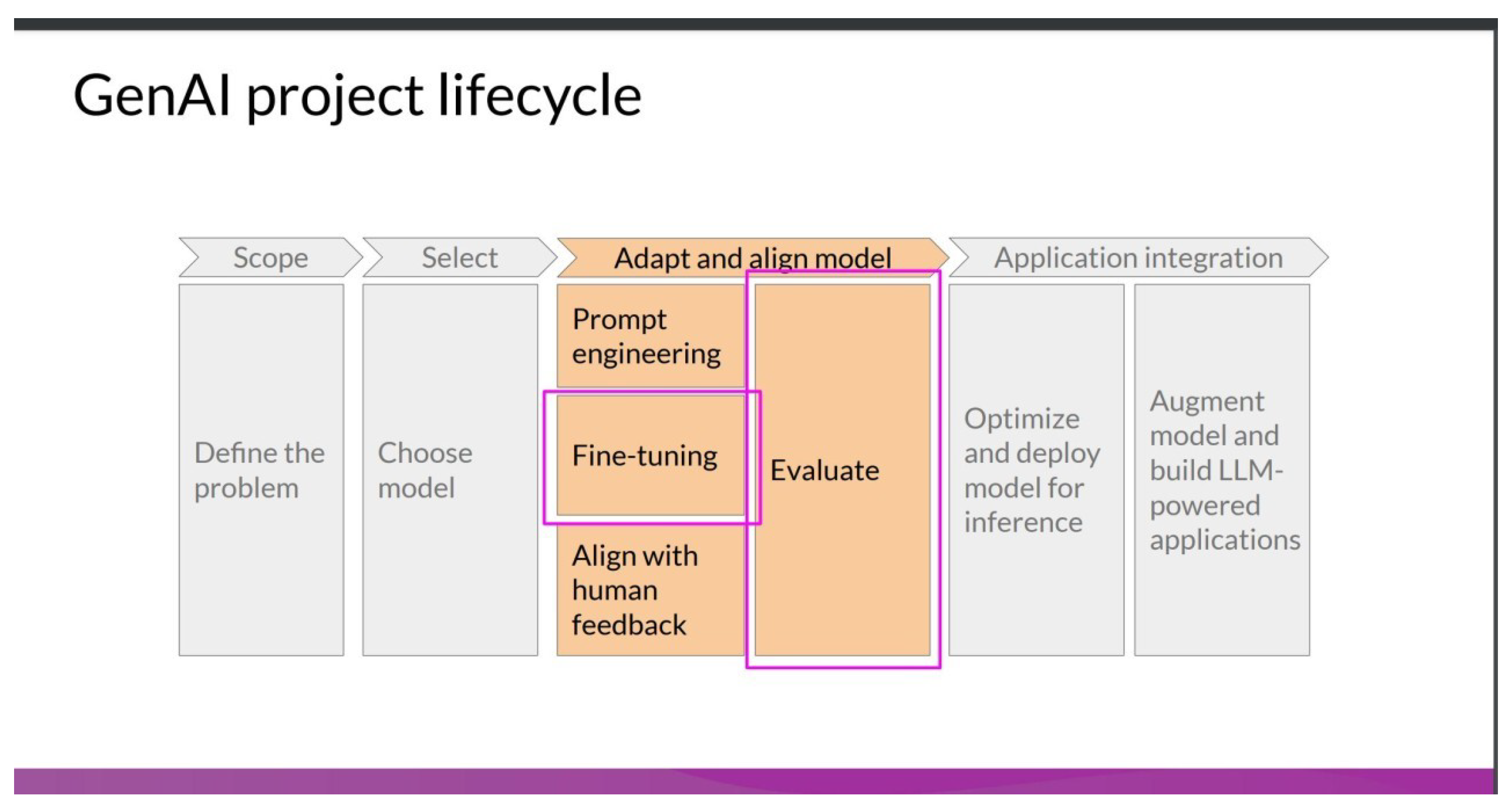

Figure 46.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 1).

Figure 46.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 1).

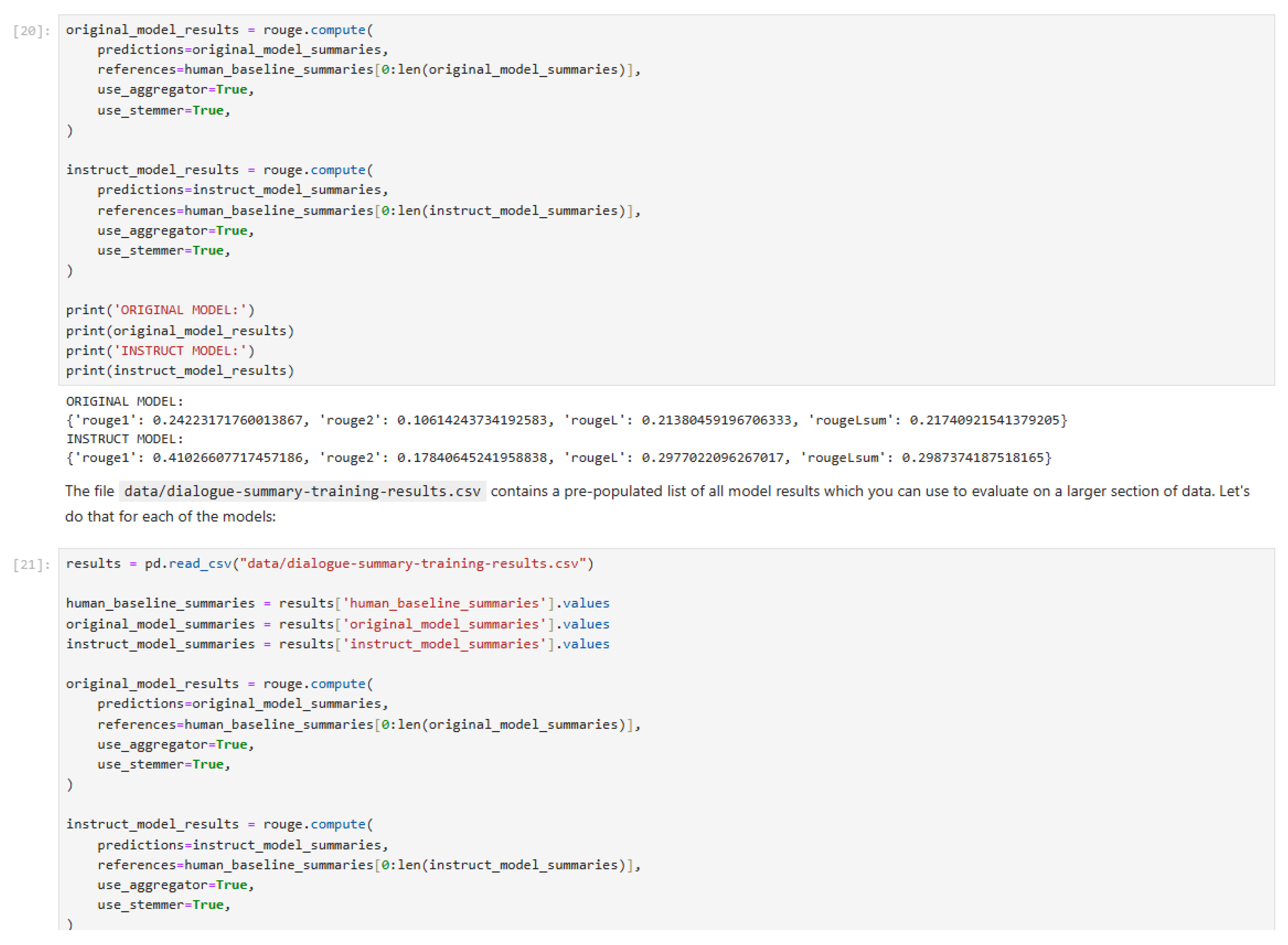

Figure 47.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 2).

Figure 47.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 2).

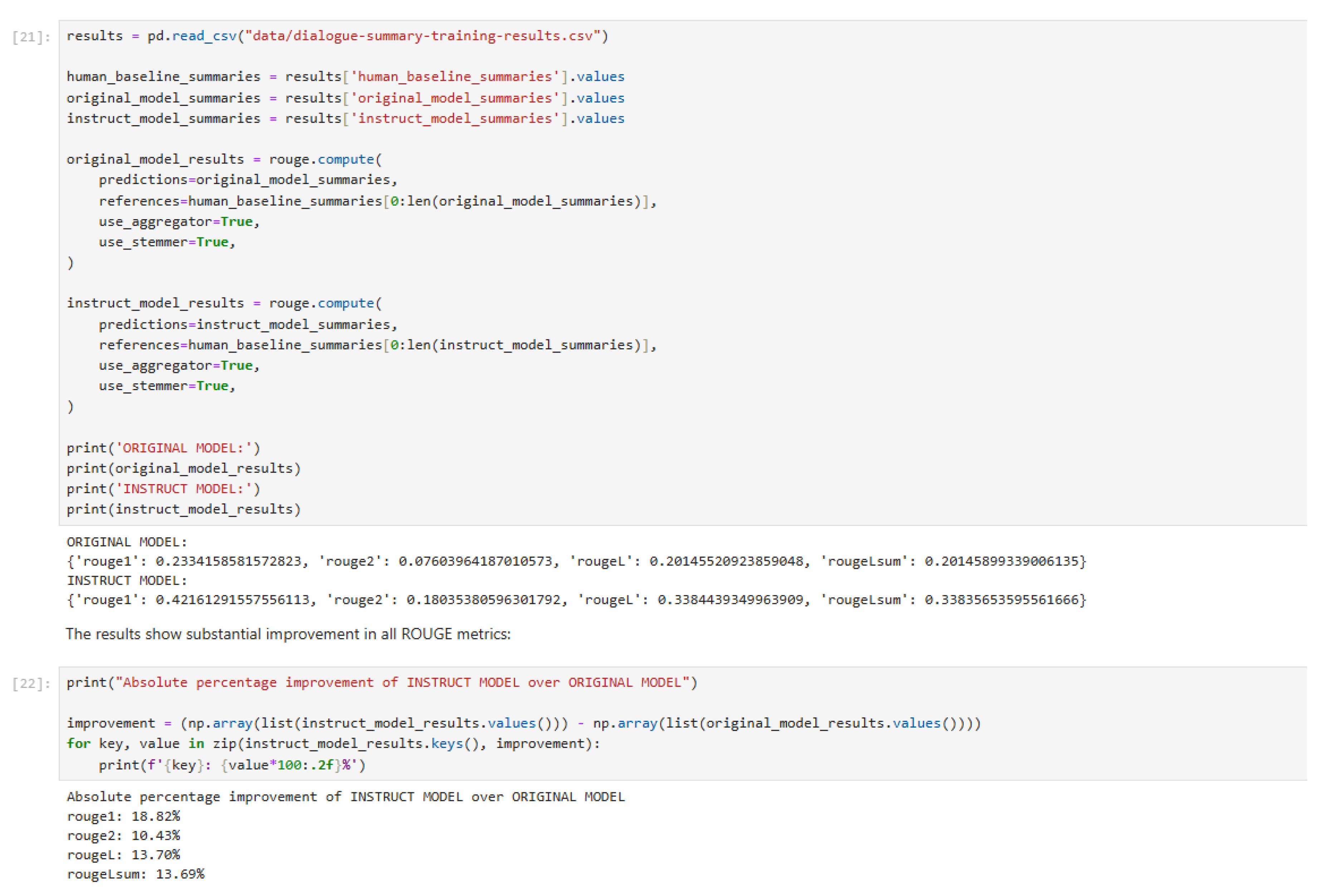

Figure 48.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 3).

Figure 48.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 3).

Figure 49.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 4).

Figure 49.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 4).

Figure 50.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 5).

Figure 50.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 5).

Figure 51.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 6).

Figure 51.

Quantitative evaluation of the model (Part 6).

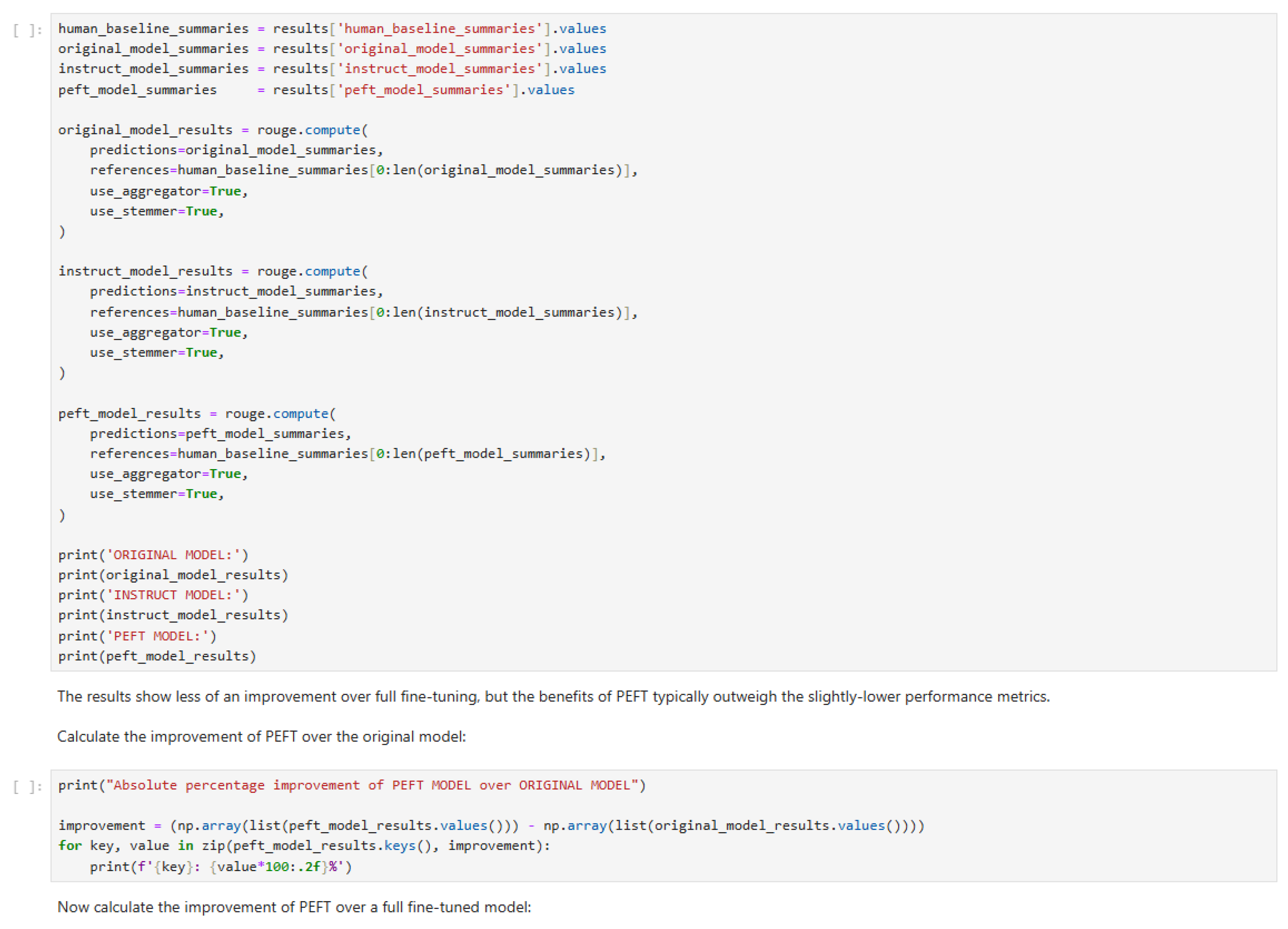

Figure 52.

Comparison of Rouge Scores Across Labs.

Figure 52.

Comparison of Rouge Scores Across Labs.