Introduction:

Digitalization is reshaping the construction industry by integrating automation, robotics, and data-driven workflows to improve productivity, reduce waste, and enable unprecedented design freedom. Among these technologies, 3D Concrete Printing (3DCP) stands out for its potential to disrupt traditional practices by eliminating formwork and enabling complex geometries with minimal manual labor. However, one of the principal challenges limiting widespread adoption is the insufficient interlayer bond strength, a critical factor for structural safety and performance .

The bond between printed layers—mediated by the Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ)—is influenced by several factors, including the open time (delay between successive layer depositions), material rheology, hydration kinetics, and environmental conditions. Studies by Panda et al. (2018) and Marchment et al. (2019) have demonstrated that delayed printing times can significantly reduce tensile bond strength, especially in systems with rapid setting binders like OPC.

Simultaneously, the industry is facing pressures to reduce its carbon footprint. The cement sector alone contributes approximately 7% to global CO2 emissions (Andrew, 2019). The use of alternative binders and digital manufacturing strategies presents a pathway toward more sustainable practices. 3DCP not only reduces material usage by optimizing form but also enables the integration of low-carbon cements and waste-derived supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), which can slow hydration and potentially enhance interlayer adhesion (Martínez Pacheco, 2023).

In this context, our study explores the dual impact of open time and binder composition on interfacial bonding, addressing the gap in understanding how rheological and hydration behavior of different blends influence print quality and mechanical integrity (Martínez Pacheco, 2021).

Material and Methods:

Three binder systems were prepared: (i) 100% OPC (CEM I 42.5R), (ii) OPC + 30% fly ash (FA), and (iii) OPC + 50% GGBFS. The water-to-binder ratio (W/B) was kept constant at 0.35 across all mixes. A polycarboxylate ether (PCE) superplasticizer and a viscosity-modifying agent (VMA) were included to ensure printability and buildability. All materials conformed to EN 197-1 and EN 450-1 standards.

A gantry-based 3DCP system was employed with a nozzle diameter of 25 mm. Four open time intervals (0, 10, 20, and 30 min) were tested. The printing was conducted at 21±1°C and 50±5% RH. Each specimen was printed in 5 layers, and the interlayer contact surfaces were neither pre-wetted nor treated.

Figure 1.

3DLAB Printer at Cementos La Cruz .

Figure 1.

3DLAB Printer at Cementos La Cruz .

Direct tensile bond strength tests were performed in accordance with EN 1542. Specimens were cut into 50x50 mm cubes across layer interfaces after 7 and 28 days. Rheological properties were measured using a rotational rheometer (ICAR Plus) with a vane geometry. Additionally, isothermal calorimetry was used to monitor hydration kinetics during the first 24 hours.

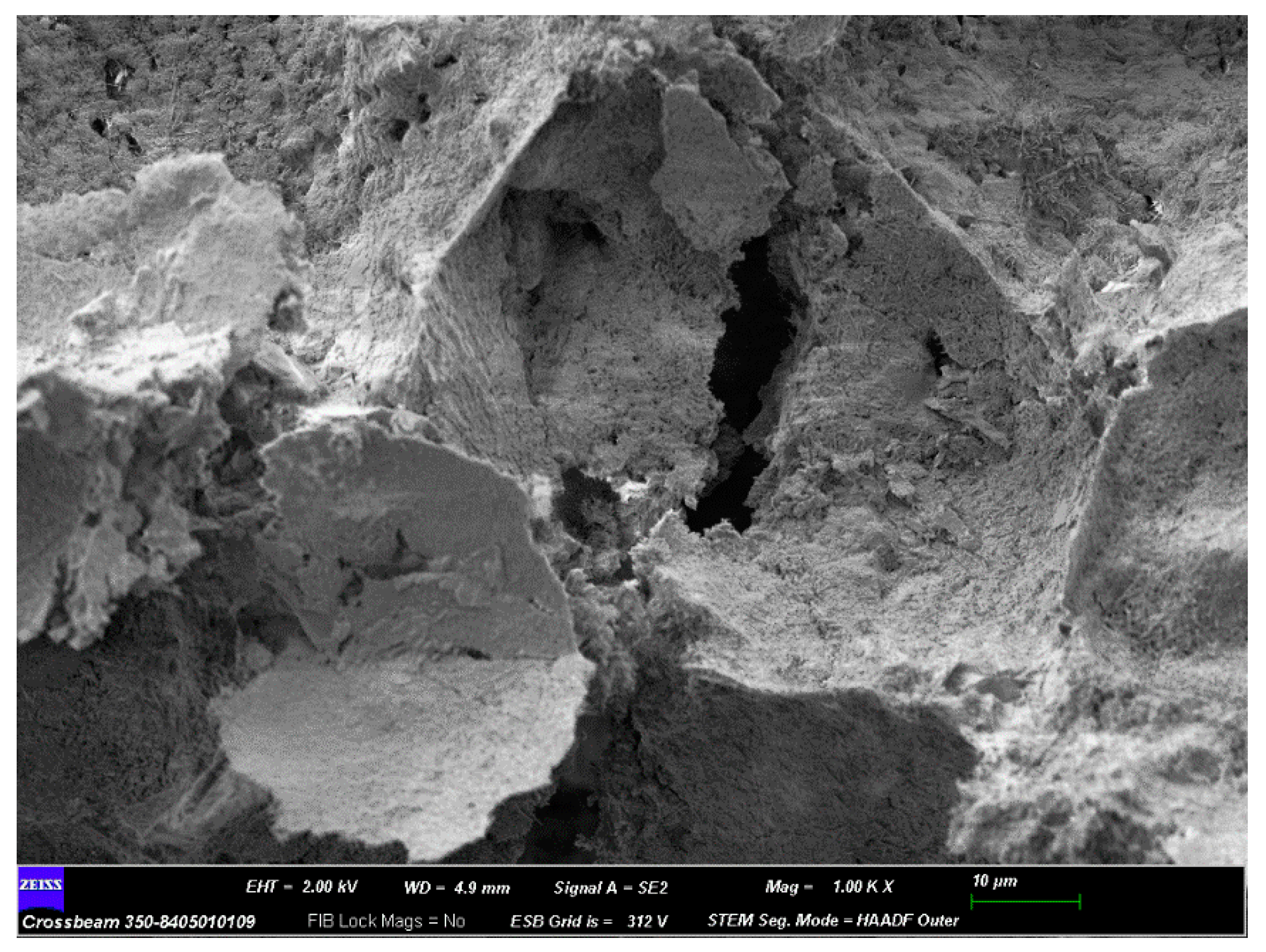

Interfacial microstructure was analyzed via SEM imaging and EDS elemental mapping to identify porosity and unreacted particles in the ITZ.

Results:

The results show that the bond strength decreases with increasing open time, more markedly in pure OPC mixes. Blended systems exhibited improved retention of adhesion, likely due to their reduced early hydration heat and slower setting behavior. The calorimetry data confirms a direct correlation between cumulative heat release and early bond degradation.

Table 1.

Tensile Bond Strength at 7 Days (MPa).

Table 1.

Tensile Bond Strength at 7 Days (MPa).

| Open Time (min) |

OPC |

OPC + 30% FA |

OPC + 50% GGBFS |

| 0 |

1.20 |

1.10 |

1.15 |

| 10 |

0.95 |

1.02 |

1.08 |

| 20 |

0.75 |

0.95 |

1.00 |

| 30 |

0.50 |

0.85 |

0.92 |

Table 2.

Cumulative Heat of Hydration at 12h (J/g).

Table 2.

Cumulative Heat of Hydration at 12h (J/g).

| Binder Type |

Heat (J/g) |

| OPC |

135 |

| OPC + 30% FA |

102 |

| OPC + 50% GGBFS |

98 |

Figure 2.

SEM image of interlayer ITZ at 20 min open time (annotated with porosity zones and particle contact).

Figure 2.

SEM image of interlayer ITZ at 20 min open time (annotated with porosity zones and particle contact).

Discussion:

The degradation of interlayer adhesion over time is fundamentally linked to the competing mechanisms of thixotropic structural build-up and early hydration. In OPC-rich systems, the higher rate of hydration generates heat rapidly, consuming available moisture and reducing the reactivity of subsequent layers (Le et al., 2012). This phenomenon exacerbates the formation of a weak ITZ due to incomplete chemical bonding.

Blended binders such as those containing fly ash or GGBFS exhibit extended open times due to slower reactivity, which is advantageous in multi-layer printing. Furthermore, these materials often improve the microstructure by refining pore distribution and increasing late-age strength (Khalil et al., 2021). SEM and EDS analyses in our study confirm the presence of denser ITZs in GGBFS-rich specimens, with fewer microcracks and unreacted grains at the interfacial plane.

From a process perspective, ensuring adequate adhesion requires synchronized control of print speed, layer height, and environmental conditions. Adaptive rheological control—via admixtures or real-time sensing—may enable dynamic optimization during printing. The integration of machine learning algorithms for predictive modeling of bond strength, as proposed by Bos et al. (2016), could further enhance quality assurance.

The implications are not only mechanical but regulatory. Current European standards (EN 206, EN 1992-1-1) do not explicitly address interlayer interfaces in printed materials. Our findings advocate for the incorporation of adhesion performance criteria into future updates of EN frameworks, especially given the structural role of vertical interfaces in wall-type elements.

Conclusion:

This study confirms that interlayer adhesion in 3D printed cementitious materials is significantly influenced by open time and binder composition. OPC mixes showed critical bond loss beyond 15 minutes, while fly ash and GGBFS blends provided extended workability and reduced early strength degradation due to moderated hydration. Microstructural and calorimetric evidence reinforces the need for process-material synchrony in additive construction. These insights support the development of robust, scalable 3D printing practices and provide a foundation for future standardization in digital construction materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Innovation and Development Department at Cementos La Cruz for supporting the experimental campaign.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 3DCP |

3D Concrete Printing |

| ITZ |

Interfacial Transition Zone |

| OPC |

Ordinary Portland Cement |

| W/B |

Water-to-Binder Ratio |

| GGBFS |

Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag |

| EN |

European Norms |

| AM |

Additive Manufacturing |

References

- Panda B, Lim JH, Tan MJ. Mechanical properties and deformation behaviour of early age concrete in the context of digital construction. Cem Concr Res. 2018;106:103–115. [CrossRef]

- Marchment T, Sanjayan J, Nematollahi B. Effect of delay time on interlayer bond strength of 3D printed concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2019;261:119984. [CrossRef]

- Andrew RM. Global CO2 emissions from cement production. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2019;11:1675–1710. [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pacheco V. Impresión 3D de hormigón en arquitectura. Master's Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, 2021. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10317/10222.

- Martínez Pacheco V. Desarrollo de materiales cementantes de baja huella de carbono para aplicaciones en la industria de la construcción y adaptación para fabricación aditiva en arquitectura de bajo impacto ambiental. PhD Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Le TT, Austin SA, Lim S, Buswell RA, Gibb AGF, Thorpe T. Mix design and fresh properties for high-performance printing concrete. Mater Struct. 2012;45(8):1221–1232. [CrossRef]

- Khalil EA, Ezz H, Shaker A, et al. Influence of GGBFS and fly ash on fresh properties, strength and microstructure of 3D printed concrete. J Build Eng. 2021;42:102420. [CrossRef]

- Bos FP, Wolfs RJM, Ahmed ZY, Salet TAM. Additive manufacturing of concrete in construction: potentials and challenges of 3D concrete printing. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2016;11(3):209–225. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).