1. Introduction

Pedestrian behaviour plays a crucial role in urban traffic systems, influencing overall mobility and safety. It encompasses the complex decision-making processes and movement patterns of individuals as they navigate shared spaces. Pedestrians continuously interact with vehicles, cyclists, and other pedestrians, adapting their actions based on environmental cues and social dynamics [

47]. Understanding pedestrian behaviour better is, therefore, an essential aspect that could be used to improve urban plans, traffic safety, and transportation efficiency. The modelling of pedestrian behaviour is inherently challenging because of its non-linear and dynamic nature as well as the influence of multiple social, cultural and environmental factors [

48]. This mix of characteristics in urban environments and the highly varied nature of streets make pedestrian behaviour in India unique. Urban spaces bring together high population density, heterogeneous road users and uneven infrastructure. Pedestrians frequently share space with vehicles, animals and street vendors. In India, the diverse mix of vehicles and pedestrians creates a dynamic and adaptive flow of movement. Pedestrians adapt to these conditions by employing dynamic decision-making strategies. For instance, they navigate through available gaps in traffic or adjust their walking speed to prevent collisions.

Figure 1 presents a snapshot of a busy street in India, illustrating these behaviors in real-world scenarios. Such unpredictability makes traditional modelling techniques insufficient and calls for more innovative approaches towards capturing such detailed behaviour patterns.

At such complex levels, machine learning based approaches, such as reinforcement learning (RL) and imitation learning (IL), become hopeful avenues [

49]. For example, one can explain using RL, how a driver learns to drive a car - what depends on the traffic flow and other environmental factors. Imitation learning enables the model to imitate examples of real-world behaviour by learning from demonstrations while capturing nuanced behaviours such as maintaining appropriate speeds in crowded areas or adjusting to the degree of road safety [

50]. Together, then, RL and IL provide a well-rounded approach for pedestrian modelling: one that combines the strategic decision-making capabilities with the ability to mimic human-like actions.

Pedestrian modeling has several critical applications across various domains. Data-driven insights play a vital role in smart city planning, particularly in enhancing pedestrian safety through optimized traffic management strategies [

3,

7,

30]. Autonomous vehicles utilize the variability in pedestrian behavior to improve navigation systems, thereby reducing accidents and ensuring safer urban mobility [

4,

5]. Additionally, predictive models contribute to crowd management and public safety by forecasting pedestrian movement patterns [

2,

9]. Furthermore, Virtual and Augmented Reality technologies facilitate traffic planning by enabling realistic simulations for training and scenario testing, ultimately leading to more efficient and secure urban environments (see

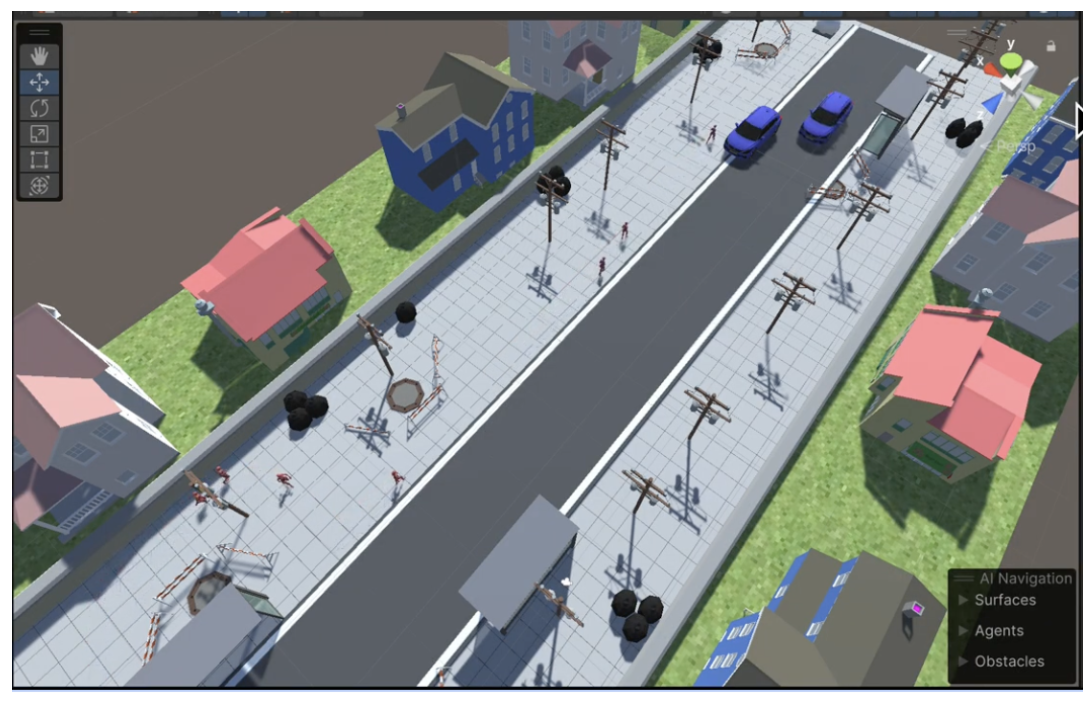

Figure 3) [

18,

32].

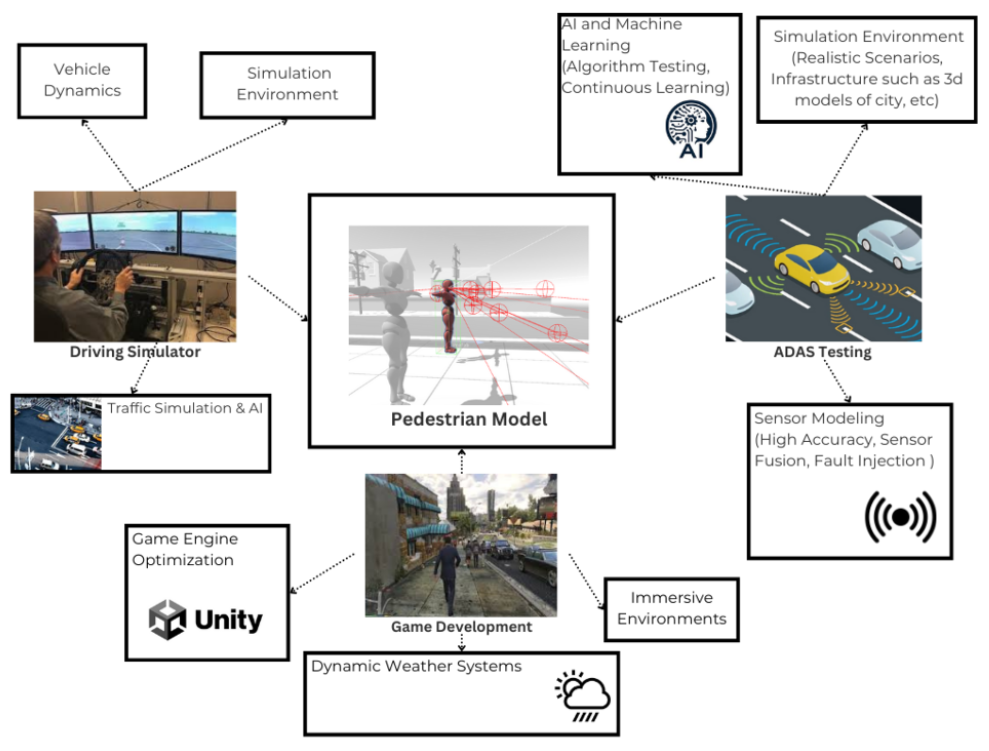

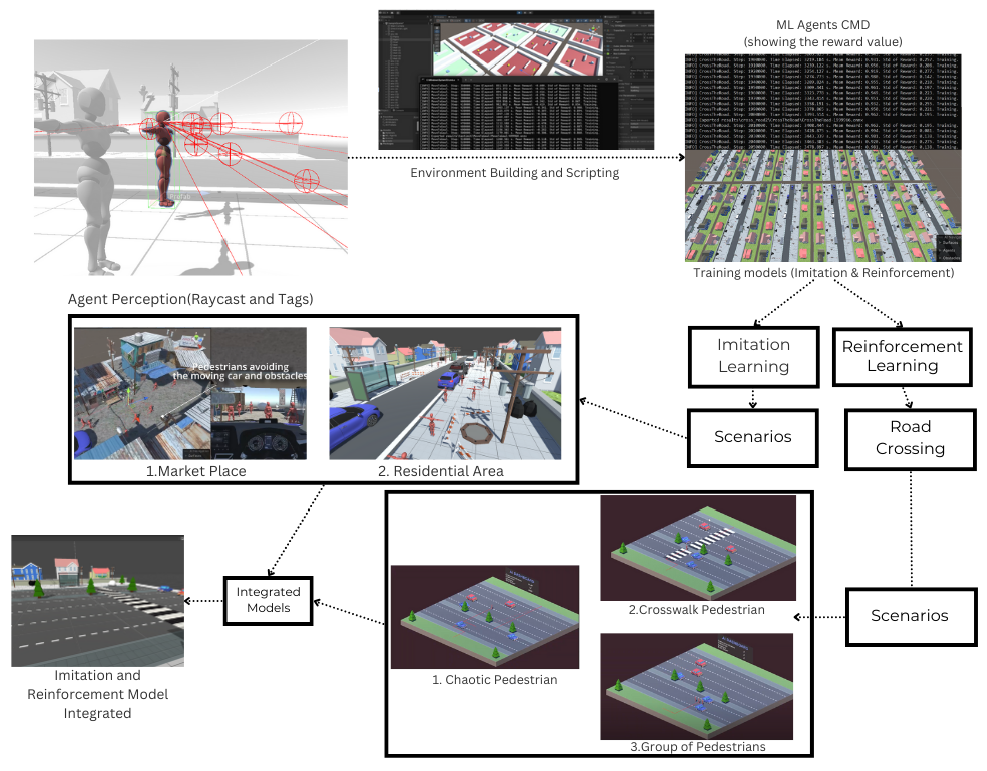

The methodology and architecture are illustrated in two diagrams.

Figure 2 presents 59 the broader applications of the model, such as traffic simulation, driving simulators, Ad- 60 vanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS) testing, and sensor modelling. It also high- 61 lights how the game engine supports immersive environments with features like dynamic 62 weather, while AI-driven algorithms enhance learning and decision-making.

Figure 3 details the integration with 3D environments and agent perception mechanisms like raycast sensors. It shows the training pipeline combining imitation learning for realistic navigation and reinforcement learning for adaptive decision-making in scenarios like road crossings. Diverse scenarios such as crossing on crosswalk, chaotic crossings, group crossing, marketplaces and residential area emphasize the model’s real-world applicability.

Figure 2.

A comprehensive overview of the role of pedestrian modeling in urban mobility.

Figure 2.

A comprehensive overview of the role of pedestrian modeling in urban mobility.

Figure 3.

A detailed simulation illustrating pedestrian modeling and learning approaches, including applications in marketplaces, residential areas, chaotic crossings, group crossings, and crosswalk crossings.

Figure 3.

A detailed simulation illustrating pedestrian modeling and learning approaches, including applications in marketplaces, residential areas, chaotic crossings, group crossings, and crosswalk crossings.

The proposed modeling technique introduces a novel approach to pedestrian behavior analysis in Indian urban environments by integrating behavioral modeling, virtual reality simulation, and rigorous validation methodologies. It encompasses the following key aspects:

1. Developing a data-driven model to capture and simulate pedestrian movement patterns specific to Indian urban settings, accounting for dynamic interactions with traffic, cyclists, and other pedestrians. 2. Constructing high-fidelity 3D environments and scenario-based simulations in virtual reality to replicate pedestrian behavior through lifelike avatar representations. 3. Ensuring the scientific rigor of the behavioral model through visual validation techniques, including Turing tests for realism assessment and Monte Carlo simulations for probabilistic analysis.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the related work on pedestrian behavior modeling, focusing on reinforcement learning and imitation learning techniques.

Section 3 describes the proposed methodology, detailing how reinforcement learning and imitation learning are applied to simulate realistic pedestrian movements in Indian urban environments.

Section 4 presents the experimental results, evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed model in replicating real-world pedestrian behaviors. Finally,

Section 5 provides a discussion of the findings and concludes the paper with potential directions for future research in pedestrian behavior simulation.

2. Literature Survey

2.1. Study On Human And Pedestrian Behaviour

Agent-Based Models (ABMs) are typical approaches implemented to mimic human and pedestrian behaviours. These models imitate decisional and mutual interaction processes to make environments safer and human-centered control of autonomous systems better. In ABMs, behaviour is represented by rules and algorithms; the accuracy of such representations defines the model in question [

51]. For meaningful functional uses, human behaviour, which is core to ABMs, must consist of decision-making and interaction dynamics [

41]. Behavioural models range from purely economic ones, where individuals, organizations, or societies are assumed to make rational choices that maximize outcomes [

59]. Others are based on bounded rationality, which accounts for the limitations of human cognition and decision-making [

42]. These latter models recognize that people often make decisions with limited information, time, or processing ability, reflecting more realistic, non-ideal behaviours [

60]. In transportation and related fields, Human-Centric Artificial Intelligence (HCAI) incorporates these behavioural models into AI systems to better understand user behaviour and support effective human-AI collaboration [

19]. Key current and future challenges include ensuring explainability of AI decisions and building user trust [

61]. Another important aspect is appropriately delegating tasks between humans and machines to maintain efficiency and accountability [

62].

The use of RL allows agents to achieve optimal solutions through reward-based learning but Inverse Reinforcement Learning(IRL) and IL primarily learn actions by watching human behaviour patterns [

52]. Active Learning (AL) encourages more efficient learning by choosing when to engage human input while reducing the required data quantity [

58]. Puentes et al. studied annually aggregated accident data from Bucaramanga, Colombia to validate crossing speed and law adherence as pivotal factors based on their analysis [

43]. A test simulation showed that adding speed reducers—such as speed bumps—could improve pedestrian safety by up to 80%. This may potentially reduce the need for additional protective infrastructure like railings on the sides of the roads.

Research on specific intersections revealed different behaviours across age groups and genders. Men and children cross more frequently, while senior citizens and women cross less frequently. Researchers spotted two ways people cross, in one step or in two, highlighting the need for custom safety steps [

45]. Studies on group behaviour showed that larger groups moved slower and the space between people changed according to who was in the group. Things like parked cars and how wide the sidewalk was also affected how pedestrians acted [

46]. It is tough to create models that are both simple and realistic, can run on computers and work for all kinds of traffic.

While progress has been made in modeling human behavior, current studies often overlook social interactions and lack diverse participant representation. Additionally, many models are not equipped to handle large-scale behavioral data. This limits their predictive accuracy and real-world applicability, highlighting a gap in the literature for more inclusive, data-scalable approaches to support safer and more collaborative urban environments.

2.2. Machine Learning Based Modeling

Relative to conventional approaches, pedestrian behaviour modelling has been transformed by Machine learning (ML), correcting prior problems and providing increased efficacy. Here, by identifying exceptional and diverse human behaviour patterns, a machine learning (ML) model enhances adaptability and forecast performance, signifying substantial potential in real-time settings [

63]. For instance, integrating ML with conventional pedestrian dynamic models, such as microscopic or macroscopic models, has revealed improved the possibility to predict pedestrian flow and behaviour. Traditional approaches in this regard have been effective in modelling pedestrian velocities, and supervised learning techniques like regression have provided equally good results in real-time applications[

12]. Two additional areas where machine learning for surveillance has proven effective include the detection of suspicious activities and real-time traffic management. By applying unsupervised learning to spatial and temporal data, modern models can identify abnormal pedestrian behaviour with 92% accuracy, allowing for proactive monitoring of actions that deviate from the norm. These systems deliver real-time alerts, which not only help prevent traffic accidents by addressing potential hazards swiftly but also enhance traffic efficiency by optimizing flow based on observed patterns.[

13,

14].

Models such as Random Forest and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have been applied to classify pedestrian behaviour. These models predict future movements, thereby enhancing the safety and efficiency of automated transportation systems. . In automated driving, models like the Multimodal Hybrid Pedestrian (MHP) help address challenges in predicting pedestrian movement at intersections and crosswalks. By incorporating both discrete actions and continuous motion dynamics, the MHP model enhances autonomous vehicle navigation safety. Evaluations of real-world datasets have demonstrated its superior accuracy compared to existing techniques [

17].

In addition to that, machine learning (ML) has enhanced pedestrian navigation scenarios in virtual environments. Improvements to the Social Force Model, such as the integration of a Natural Evasion Model (NEM)[

64], facilitate the simulation of authentic and predictive pedestrian movements. These refinements reduce interference in driving simulations and enhance the realism of urban scenarios [

18]. ML has also enriched the study of pedestrian route choice behaviours through advanced techniques. Models such as eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) [

53] and Light Gradient Boosting (LGB) [

54] have surpassed traditional discrete choice models in predicting route choices. Furthermore, interpretability tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations, which is a popular explainability method in machine learning), have identified critical factors that influence pedestrian decisions, such as bottlenecks and return periods, thus informing transport planning [

19].

However, current research still faces challenges such as data quality, extending models to handle invariant sequences and accommodating the diverse actions of pedestrians. Future efforts should focus on comparing results with larger databases. They should also incorporate social interactions into the models and develop more efficient algorithms to approximate human behaviour. These steps can further enhance ML’s contribution to pedestrian safety and the optimization of urban environments. This will help solidify its role as a pivotal technology in the development of intelligent systems [

12,

13,

14,

17,

18,

19].

2.3. Deep Learing Based Modeling

Accurate classification of pedestrian scenes at crosswalks as safe or risky was provided by Mask R-CNN and a custom Crosswalk Detection Algorithm (CDA) while minimizing required computations[

21].In another case, transfer learning was implemented in identification of pedestrians in self-driving cars with the help of Convolutional Neural Network (CNNs)[

22]. According to the study, the researchers just tuned the already trained Visual Geometry Group(VGG)-16 model and obtained 98% of the validation accuracy. They also showed how deep learning models could incorporate LiDAR data for 3D detection of pedestrians for AI vehicles’ better perception. By integrating pose estimation to the deep learning techniques, Boda and Ramadevi forecasted the action of pedestrians at zebra crossings[

23]. Conducting skeleton detection using OpenPose and feeding it into ML classifiers, they have high precision in categorizing behaviours such as walking and crossing that could enhance the interaction between pedestrians and vehicles [

55].

Zhai et al proposed a social-aware, multi-modal network for the prediction of pedestrian crossing behaviour. It followed this model which uses a Spatio-temporal Heterogeneous Graph and a conditional variational autoencoder to generate multiple possible future pedestrian behaviours. Prior to it, the previous methods were less effective and had poor safety when compared to autonomous driving[

20]. Kielar and Borrmann employed an artificial neural network to simulate pedestrian behaviour in the form of a model for animation and called this method Automatic Pedestrian Animation Generation [

29]. In a similar manner, Larter et al. have used behaviour trees to model pedestrian behaviour. They incorporated the Social Force Model (SFM) to create a hierarchical system. This model is capable of mimicking realistic decisions made by pedestrians. It also captures their interactions with vehicles in traffic simulation systems [

30].

These studies demonstrate DL’s ability to improve pedestrian behaviour modelling by enhancing accuracy, adaptability, and efficiency. Moving forward, continued advancements in DL will further refine these models, offering even more sophisticated solutions for autonomous vehicle safety and urban planning [

22,

23,

29].

2.4. Reinforcement Learning Based Modelling

Mahmoudi and Ostreika [

2] developed an RL racecar agent to drive on a track with obstacles using Proximal Policy Optimisation (PPO). To boost learning efficiency, they combined behaviour cloning and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL), resulting in an effective obstacle avoidance policy.

Subsequently, Vizzari and Cecconello [

5] enhanced RL using curriculum learning. To train the pedestrian agents, they tested the AI agents in environments of increasing difficulty and incorporated norms into the learning phase. Their model demonstrated how an agent could transition into unfamiliar territory without referring to a predefined rule set for realistic pedestrian behaviour.

In studies on pedestrian–vehicle interactions, Nasernejad et al. [

7] proposed a Gaussian Process Inverse Reinforcement Learning (GP-IRL) model to understand pedestrian behaviour during near-miss collisions. The movements they quantified included evasive actions that their model was able to capture successfully, as they shed light on factors that influence pedestrians’ behaviour in emergency or dangerous situations.

Mu et al. [

9] proposed a possible solution to the short-sightedness of traditional models by incorporating deep reinforcement learning with expert trajectory advice. These authors’ D3QN-ORCA model integrated global path planning and local collision avoidance, aiding the agents in predicting traffic density and manoeuvring through crowded regions. Since the simulation ran faster and more accurately, this enhanced its usefulness in areas like emergency evacuation scenarios.

Another study [

10] has applied RL in combination with sensory-motor contingencies that are used to reproduce some of the pedestrian behaviours like gap acceptance and crossing initiation. By encompassing some of the characteristics of visual perception and motor constraints, the model proved quite realistic when mimicking the pedestrian’s movements and provided insights into AV safety considerations.

Yet, to enhance the pedestrian simulations, another study [

11] combined deep RL with optimal Reciprocal Collision Avoidance (ORCA) for the strategic development and real-time execution of tactics. When guided by an expert’s path, the model cut down on unnecessary trial-and-error, speeding up the learning process and improving the random simulation of busy, crowded scenes.

Ghasemi et al. [

24] complemented RL’s fundamental concepts and focused on its stochastic characteristic, which requires learning from errors in sequential decision-making tasks. Meanwhile, Jaeger and Geiger [

25] investigated RL as a way to optimise outcomes for goals that cannot be solved using standard gradient-based techniques, touching upon applied strategies such as PPO and SAC. In their systematic review, Sivamayil et al. [

26] pointed out that RL is useful in a variety of rapidly changing domains. These include energy, robotics, autonomous vehicles, and more. PPO, which was discussed by Schulman et al. [

35], is one of the most efficient and robust RL algorithms. It is capable of operating effectively in complex simulations.

2.5. Imitation Learning Based Modelling

Imitation Learning (IL) is seen as a promising method to model pedestrian behaviour since machines are trained by observing the action performed by a human. Basically, the major approach used in IL is Behavioural Cloning (BC) [

34], where agents learn to map situations to actions by copying human demonstrators. Nevertheless, BC has some issues such as co-variate shift, meaning the agent receives situations it has never seen before during learning [

27,

28,

38,

40]. To counter this, BC is enhanced by Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL), since it entails a generator and a discriminator in the game theoretic framework. Mimicking the action of generators and discriminators in order to distinguish the agent’s and expert’s actions can reduce co-variate shift [

3,

27,

28,

40]. Additionally, InfoGAIL [

3] maximizes information to eliminate human inaccurate repetition of motion and includes latent variables to make action variance increase and be more realistic by considering hidden states like urgency or mood of the human pedestrian [

3,

28,

40].

Incorporation visual attention into imitation learning has shown promise. Using saliency maps to highlight where humans focus attention helps agents prioritize spatial information, leading to more realistic behaviors like obstacle avoidance and pedestrian navigation [

3]. In autonomous driving, it is very important to model pedestrian behaviour, to do this, Human-oriented Agent-based Imitation Learning (HAIL) is used to copy how people move in traffic. It works with OpenDS [

65] and InfoSalGAIL [

3] to recreate these actions in a traffic setting. [

6].

Behavioural Cloning from Observation (BCO) takes IL further by allowing agents to learn directly from observing scenarios, even when the exact actions taken in those scenarios are unknown or unavailable [

34]. In gaming, IL enhances non player character (NPC) interactions by imitating human behaviour, thereby providing gamers with unexpected and realistic gameplay patterns [

8].

Thus, imitation learning helps to suggest how machines mimic actions and thus make it real and safer for applications like self-driving cars and urban planning. When applied to new IL techniques such as GAIL, InfoGAIL, and HAIL in the future, there will be improved and safer interaction between humans and technology. Reinforcement Learning (RL) is also shown to be a strong way to simulate how pedestrians act, even with all the complicated details. These models improve by including things like movement limits, social rules, and expert guidance, making pedestrian simulations more practical and safer, and laying the groundwork for smart systems that can adapt to human behaviour.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

The methodology involves constructing environments using scaffolding techniques, developing behavioural models, and integrating machine learning algorithms within a 3D environment. The main objective is to learn an independent pedestrian agent to perform safe and efficient road-crossing of an urban environment with both imitation and reinforcement learning.

3.2. Model Development

The presented system also includes several modern deep learning approaches for pedestrian movement modelling. Some of these are known as – Behavioural Cloning (BC)[

34], Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL)[

3] and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)[

35]. A mechanism is designed to switch between two models based on environmental context: imitation learning is employed for navigating through walkable residential areas where the agent mimics realistic human behaviours, whereas reinforcement learning is activated specifically in complex scenarios such as road crossings, allowing the agent to make dynamic, adaptive decisions in response to varying traffic conditions.

3.2.1. Behavioural Cloning (BC)

Agents in Behavioural Cloning (BC) perform supervised learning by adopting and replicating expert demonstrations to determine their optimal actions. A deep neural network serves as the policy network, which receives state information s (such as pedestrian position, velocity, surroundings) as input, and produces a corresponding predicted action a. The training process for the network involves learning from expert demonstrations containing state-action pairs . Human expert actions serve as the target reference, and the goal is to minimise the discrepancy between these actions and the predictions generated by the policy network , thus achieving accurate imitation and realistic behaviour replication.

3.2.1.1. Loss Function:

The training process is guided by the mean squared error (MSE) loss function, which is formulated as:

where

represents the dataset of expert demonstrations. This equation ensures that the model minimizes the difference between the predicted action

and the expert action

a, thereby aligning the agent’s behaviour with that of the expert. By minimizing the loss function in Equation

1, the agent refines its policy to closely mimic expert decisions, improving its predictive accuracy.

BC works as an effective solution because it can be implemented through supervised learning approaches and functions efficiently when experts provide demonstrations. However, the method faces two main issues: its tendency to overfit observed data samples and its inability to adapt to changing conditions across different scenarios.

3.2.2. Generative Adversarial Imitaion Learning (GAIL)

The GAIL framework integrates Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) with reinforcement learning (RL), allowing an agent to learn behaviours without explicitly defined reward functions. A GAN consists of two components: a generator, which learns and replicates expert behaviour patterns, and a discriminator, which distinguishes between the actions performed by human experts and those generated by the agent. The generator aims to produce movements that closely match expert demonstrations, effectively misleading the discriminator.

3.2.2.1. Equations:

The discriminator function, given by Equation

2, evaluates whether a given state-action pair

comes from expert demonstrations or the learned policy:

The algorithm optimises this loss function to achieve both the highest probabilities of correctly classifying expert trajectories and the lowest probabilities of generated trajectories being mistaken for expert trajectories.

The generator function, described in Equation

3, trains the policy

to minimize the expected loss from the discriminator:

This adversarial objective ensures that the learned policy generates trajectories that are indistinguishable from expert demonstrations, effectively mimicking expert behaviour.

The behaviour learning capabilities of GAIL operate without requiring explicit reward definitions, making it suitable for complex environments. This method demonstrates the capability to generalise learning to different situations across various scenarios and effectively manage multiple conditions. However, the learning process involving the generator and discriminator can be computationally expensive, demanding precise adjustment of training stability parameters.

3.2.3. Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)

Policy updates within reinforcement learning achieve stability and efficiency through the implementation of the PPO approach. The control system employs PPO to enhance the adaptability of pedestrians under specific circumstances, including road crossings.

Working Mechanism:

PPO redefines the policy updates by using a clipped surrogate objective, as expressed in Equation

4. This mechanism limits excessively large updates to the policy, ensuring stable and controlled improvements during training. The agent updates its decision-making process based on experiences gained from interacting with the environment and the cumulative rewards achieved.

Analysis:

The method successfully sustains both exploration and exploitation phases together, with reliable policy modification procedures. As shown in equation

5 the probability ratio

plays a crucial role in determining how much the new policy deviates from the old one, ensuring controlled updates to prevent instability. However, the method involves computationally intensive calculations for large-scale scenarios and is sensitive to parameter adjustments.

3.2.4. Hybrid Learning Model for Pedestrian Navigation

Reinforcement learning was integrated with imitation learning to effectively manage scenarios ranging from structured environments to unstructured and unpredictable conditions. The system executed model-switching logic which used agent proximity to crossroads for alternating between different approaches. The overall vehicle movement function relied on imitation learning, but reinforcement learning became essential for managing dangerous situations such as street crossings. The combined use of these systems maintained efficient control in planned situations as well as unclear situations.

Key Features:

Adaptive Learning: When performing usual navigation tasks,the agent employed imitation learning but switched to reinforcement learning to handle dynamic traffic conditions.

Reward System: A reward system based on reinforcement learning incentivised successful fast movements across the road and penalized any accidents or incorrect behaviours. Through experience, the agent could repeatedly improve its strategy.

3.2.5. Agent Perception And Deception

To ensure effective interaction with the environment, the pedestrian agent was equipped with advanced perception mechanisms, mimicking human vision and awareness.

Raycast Sensors: The agent controlled three adjustable head-level rays for optimal peripheral vision capacity through adjustable angles and distances. The raycasting system covered all areas of the environment to let the agent effectively observe objects before appropriate response actions could be performed.

Tag Detection: The raycasts were programmed to recognize specific objects in the environment, including immovable obstacles such as barriers, potholes, and streetlights. Additionally, they detected other pedestrians to enable social navigation and moving vehicles to facilitate dynamic road-crossing decisions. They also detected designated goal points that guided the agent’s movement for maximum points.

Realistic Perception: Raycast configuration and placement enabled the robotic agent to detect surroundings just like the human vision functions. The chosen placement and configuration of raycasts enabled correct and specific data use for decision-making processes. By enhancing its perception, the agent became better equipped to handle intricate situations, such as stopping appropriately for approaching vehicles and determining safe moments to cross through traffic.

3.3. Recording The Demonstration

The expert demonstration data took video format to record their actions. Pedestrian agents walked throughout the simulated environment while performing steps for safe road crossing in order to succeed. This phase emphasized the following:

Human-like Movements: The expert indicated how the subjects adjusted their speed and direction in response to approaching objects (vehicles).

Training Objectives: The recordings were analyzed to establish behaviours for the agent, such as stopping before crossing or waiting for a safe gap in traffic.

3.4. Scenario Design

For the thorough evaluation of agent performance, several scripted scenarios were designed:

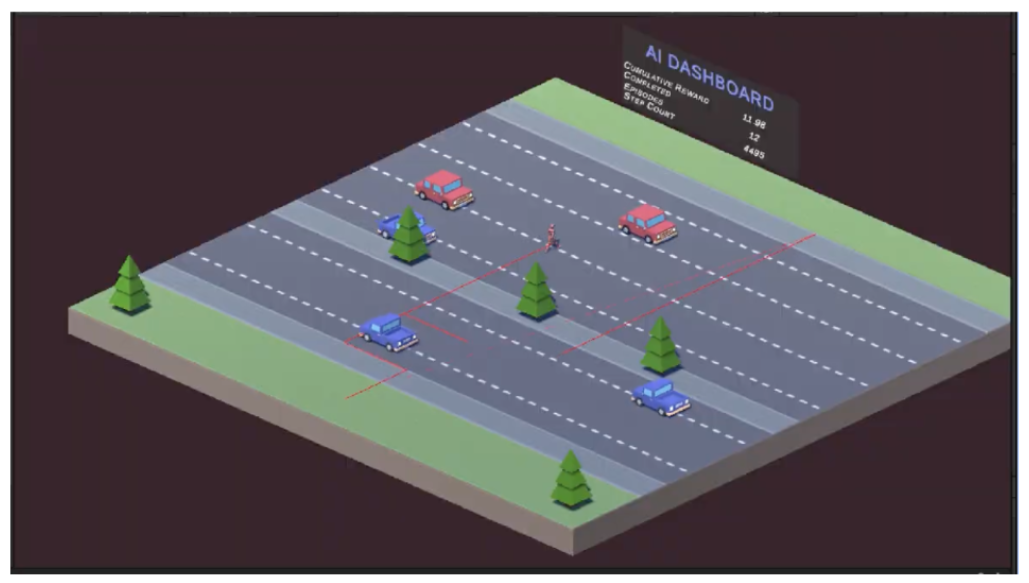

Scene 1: The scenario depicted in

Figure 4, where individuals are crossing the road without following any traffic laws, assessed the agent’s ability to react quickly and safely when faced with making a decision in a dangerous situation.

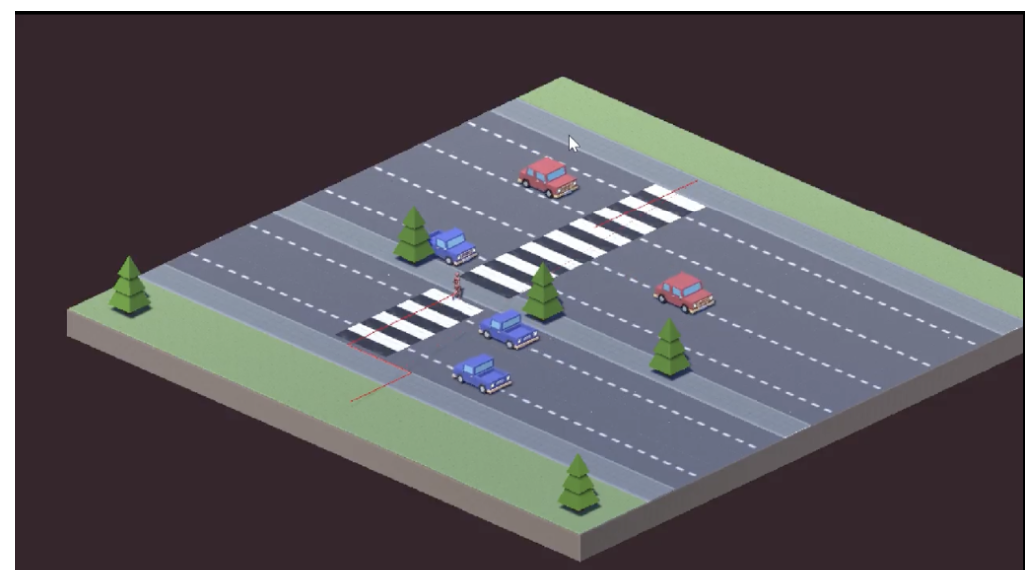

Scene 2: As seen in

Figure 5, the agent was required to detect and use the closest crosswalk, emphasizing the importance of structured, rule-based crossings.

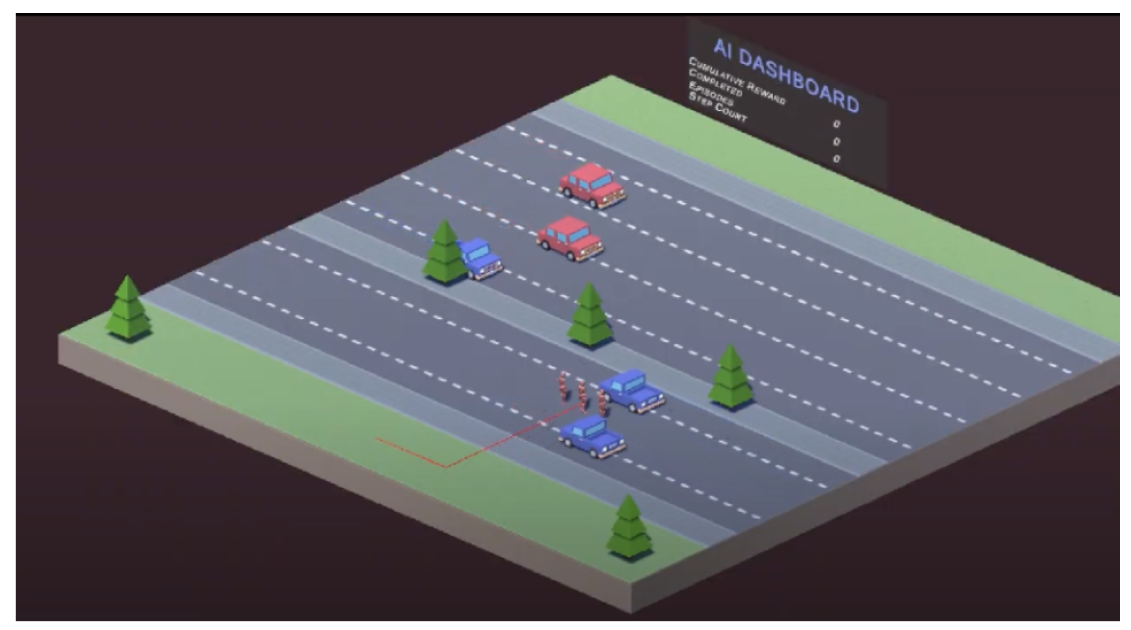

Scene 3: Multiple agents cross the road at the same time, as shown in

Figure 6, creating crowd dynamics and testing agent abilities in social navigation.

Scene 4: The agent demonstrated its adaptability by switching from imitation learning to reinforcement learning when approaching a busy road for crossing, ensuring it could handle various situations effectively, as seen in

Figure 7.

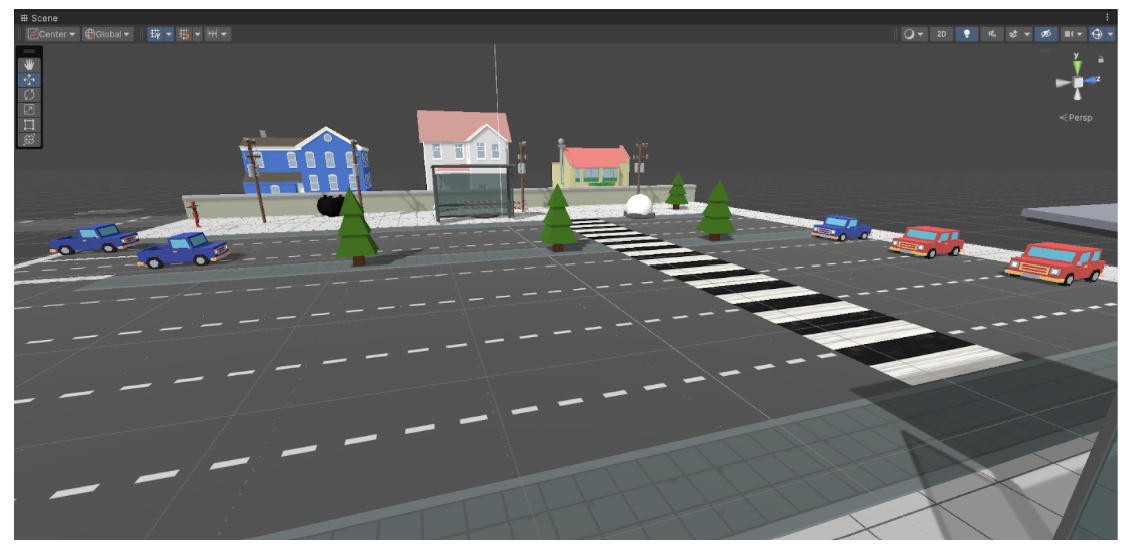

Scene 5: This scenario involved modelling a realistic residential street with footpaths, houses, streetlights, and various scattered obstacles, as shown in

Figure 8. While the agents move, they have the opportunity to avoid these static obstacles and follow pedestrian rules for safe crossing. This realistic use case simulates typical weekday pedestrian behaviour in a residential environment.

Scene 6: The setting depicted in

Figure 9 is that of a bustling marketplace filled with pedestrians meandering through numerous kiosks, vehicles, and barriers. The simulation provides an urban experience that reflects real-world conditions, testing the agent’s decision-making in a high-traffic area.

3.5. 3D Environment Design

Implementation of the decision-making scenario established real urban road-crossing conditions. The environment contained these key elements for its structure:

This setup offered an environment that was both virtual and dynamic in 3D, suitable for training and testing the agent.

Flat Surface (Ground): A plane that describes a starting point of the environment.

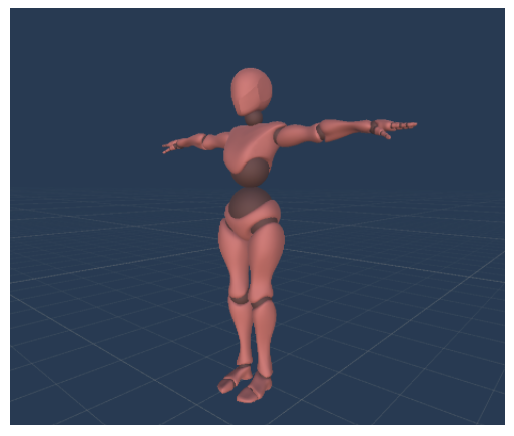

Controllable Character (

Figure 10): The player character that would learn to safely navigate the road by training.

Surrounding Barriers (Walls): The barriers set and limit the user within the environment and attempt to simulate real world, such as buildings or barriers.

Designated Destination (Target Point): The agent must be able to cross the street, which is the aim in the case of successful crossings.

Dynamic Obstacles (Vehicles and Roadblocks): Car models create traffic with controlling parameters such as speed and density that will allow the assessment of the agent.

3.6. Hyperparameters For Training

Table 1 has the parameters we used to train the models for road crossing and footpath walking which used RL and IL respectively. They were later fine-tuned to optimize learning efficiency and performance.

4. Results

4.1. Monte Carlo Simulation

4.1.1. Introduction

The probabilistic characteristics of the pedestrian behaviour model were evaluated through Monte Carlo simulations conducted under different scenario conditions. This approach introduced randomness to walking speeds through behavioural variability based on principles from kinetic Monte Carlo simulation, as described by Sun [

38], along with Naderi’s work on indoor navigation localisation using Monte Carlo techniques [

37]. The research team simulated and tested four separate pedestrian cases: a single person crossing at risk, a pedestrian at a zebra crossing, a group of three pedestrians and two non-coordinated pedestrians. These scenarios were used to analyse different parameters including vehicle and pedestrian speeds. The simulation models generated important conclusions which showed how fast-moving vehicles combined with heavy pedestrian traffic negatively affected the number of successful crossing events. Research showed that faster vehicle motions decreased the chances of successful crossings but reduced collision risks when vehicles proceeded at slower speeds. This demonstrates how vehicle speed and pedestrian density influence the accuracy of pedestrian behaviour modelling.

4.1.2. Inference

The simulation accurately replicated decision-making processes and motion behaviours characteristic of a typical urban setting in India. Different traffic scenarios showed individual behavioural aspects of pedestrians through four simulation scenarios. During the first situation, an individual showcased dangerous behaviour by speed walking across the road in the presence of moving vehicles. In the second scenario, a responsible pedestrian crossing model was demonstrated, where individuals exclusively used zebra crossings, mirroring typical urban behaviours. When three pedestrians moved in unison during the third simulation, they adapted their speeds so that their group could function both effectively and securely. Two independent pedestrians who did not coordinate with each other were examined in the fourth scenario.

The four different scenarios underwent Monte Carlo simulations that explored various parameters to replicate numerous realistic situations. The experiment tested multiple combinations of vehicle and pedestrian speed alterations in order to assess their effects on successful crossings. Unity’s default scale assumes that 1 unit equals 1 metre, as per their best practice guide for realistic simulation scale [

57]. Using this convention, we converted in-simulation speeds from units per second to real-world speeds in km/hr using the formula: 1 Unity unit/second = 3.6 km/hr.

Table 2 contains the information about the controlled scenario conditions. During Trial 1, where vehicles moved at speeds ranging from 14.4 to 36 km/hr and pedestrians at 36 km/hr, the simulation achieved an 88% success rate. In contrast, Trial 6 involved vehicles travelling at 126 km/hr and a pedestrian speed of just 18 km/hr, which resulted in a significantly lower success rate of 33%. These findings highlight the substantial impact of high vehicle speeds on pedestrian safety and validate the model’s ability to replicate real-world traffic dynamics under varying conditions.

4.2. Turing Test

4.2.1. Introduction

We applied the Turing test for crowds according to Webster and Amos [

36] to check whether the developed pedestrian behaviour model exhibited exhibited realistic perception. The test involved presenting participants with two videos: one that contained real pedestrian behaviours inputted by a human, and the other with simulated pedestrian motions generated by the model from actual real-world conditions, to determine if the displayed actions were authentic or not. The qualitative human-based assessment measured how well the modeled pedestrian behaviour matched the natural human behaviour through observational commonsense evidence. Research outcomes showcased the model’s excellent capabilities in mimicking authentic pedestrian dynamics and generated valuable enhancements for future development.

4.2.2. Inference

Our research added imitation learning components as advanced pedestrian behaviour models within situations where footpath travel required static and dynamic obstacle avoidance including pedestrian-on-pedestrian encounters. To evaluate the effectiveness of this approach, we conducted a Turing test where participants viewed two videos: A video comparison included simulated pedestrian movements through AI technology alongside human-operated movements. Researchers tested participant abilities to detect differences between movements produced by artificial intelligence technologies and natural human behaviour.The survey was carried out with 70 participants from various age groups.

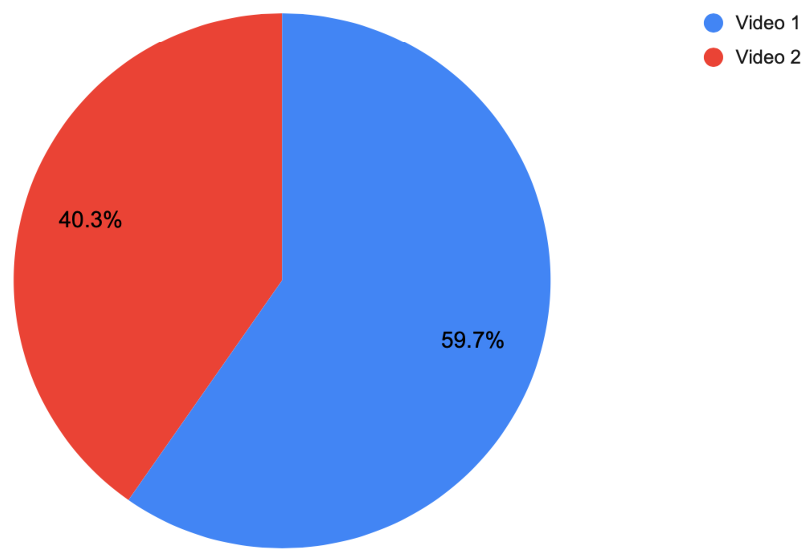

Research findings presented in

Figure 14 displayed an almost equal distribution between participants who identified each measurement type, with 59.7% recognizing AI movements and 40.3% recognizing human movements. Analysis results revealed that participants found it difficult to tell apart movements made by AI or humans because the model successfully duplicated human-style actions. The model demonstrates effective simulation of human-like movement which showcases its capability to replicate pedestrian behaviour in realistic situations for real-world applications which require pedestrian simulations.

The table below demonstrates the demographic way of responses for the two videos: AI-controlled (Video 1) and Human-controlled (Video 2). The target audience of different age groups commented on each video, showing that participants did not detect any differences between them. The results indicate that the Turing Test passed its assessment criteria. The percentages of Video 1 for the respective age categories are: 62.5% for the 18–25 age group, 55% for the 26–40 age group, 50% for the 40+ age group.

Figure 11.

Turing Test Results for Pedestrian behaviour Model

Figure 11.

Turing Test Results for Pedestrian behaviour Model

Figure 12.

Snapshot of the Agent Used in the Turing Test Video

Figure 12.

Snapshot of the Agent Used in the Turing Test Video

Table 3.

Response Accuracy Across Demographic Groups

Table 3.

Response Accuracy Across Demographic Groups

| Age Group |

AI-Controlled (Video 1) |

Human-Controlled (Video 2) |

| 18-25 |

25 |

15 |

| 26-40 |

11 |

9 |

| 40+ |

5 |

5 |

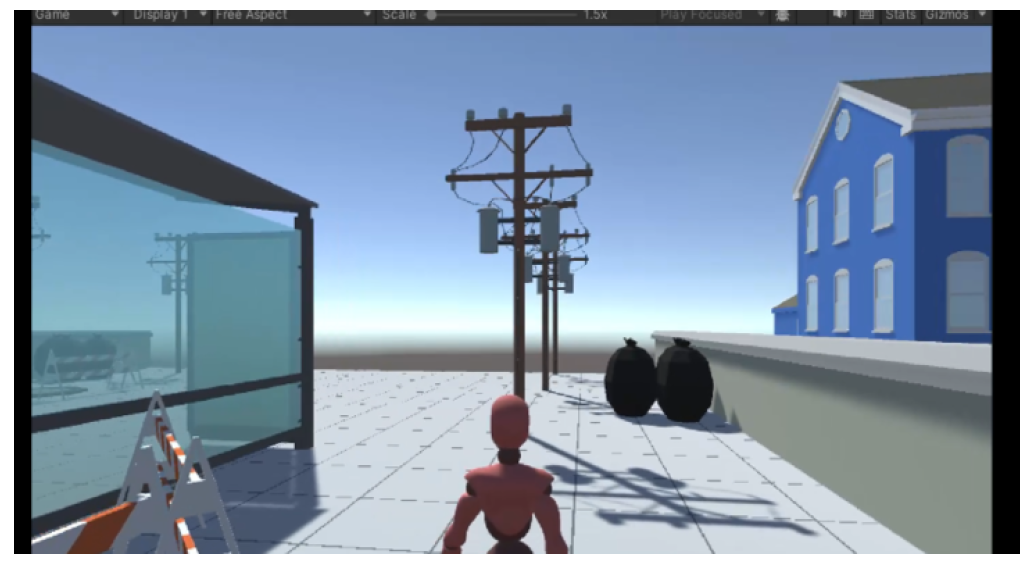

4.3. Replicating A Real-World Scenario

Finally, to test the model under more realistic conditions and in a high traffic scenario, we recreated a slow moving car simulation through a market area as depicted in 17. In this scenario, the modeled agents successfully avoided a collision with the car and adeptly navigated around both the vehicle and pedestrians; this shows that the model was flexible in dealing with dense environments. This simulation shows how this model may be used to depict pedestrian movement in complex and realistic environments such as streets and marketplaces, as depicted in Figure 16.

Figure 13.

Snapshot of the Replicated Scene in Virtual Environment: A view of the recreated simulation environment for pedestrian behaviour testing.

Figure 13.

Snapshot of the Replicated Scene in Virtual Environment: A view of the recreated simulation environment for pedestrian behaviour testing.

Figure 14.

Snapshot of the Real-World Scene: The original environment replicated for simulation in Virtual Environment [

56].

Figure 14.

Snapshot of the Real-World Scene: The original environment replicated for simulation in Virtual Environment [

56].

5. Discussion and Future Work

Although the current system provides satisfactory simulation outcomes that mimic realistic pedestrian behaviours in real life situations, the following limitations exist. The current simulations are limited because they only cover environments like markets, residential areas, and intersections. They don’t account for specific behaviours in Indian cities, such as how people react when animals cross the road or the different patterns of pedestrian movement in various areas. The model also does not take into consideration some factors such as relation to other pedestrians and some instances such as the use of a mobile phones while walking. Further, the road environment is over-simplified and pedestrian decisions and safety due to road terrains, narrow road, traffic signals and other characteristics are not incorporated into the model. Last, while the system is efficient on average hardware, real-time simulation in dense populations is computationally costly, which may impede its utility for time-critical use.

To rectify these shortcomings the following improvement can be made. Enhancing scenario and behavioural heterogeneity by including other types of additional behaviours of pedestrians, for example not paying attention to objects in the immediate environment, indecision before crossing roads, or responses to noises heard, could describe pedestrian behaviour in more detail. Incorporating such characteristics would improve the model’s output and make it more useful for applications like driving simulators or evaluating self-driving cars in real-world scenarios. By adding complexity in the environment such as including changes in terrain, traffic lights among other non-car objects and moving objects such as stray animals, the challenges posed by the environment would be more natural. This would help drivers as well as the autonomous systems to get a better perspective of how the pedestrians behave in real world Indian scenarios.

In present contexts, it is pivotal to enhance computational efficiency as one of the critical aspects of its optimization. It could be done in a way of researching more effective algorithms or utilizing, for example, GPUs or cloud to emulate more pedestrians in real time to match the conditions of real life tests.

Building on the existing system, there is scope for significant improvements by integrating Autonomous Vehicles (AVs). This integration would enhance the exploration of urban environments and AV scenarios, thus helping the pedestrian simulation process. Including coordination between vehicles and pedestrians would aid in developing models that facilitate safer interactions between pedestrians and AVs in city settings. Another area for advancement involves incorporating real-time sensor data, allowing future versions to utilize live data feeds from physical environments for more accurate model training. This would enable simulations to adjust based on varying factors like time of day, season, and weather conditions. Furthermore, enhancing data-driven modelling is crucial, as the development of imitation learning requires extensive pedestrian motion data from various Indian cities. Collecting such data would enhance the realism of pedestrian behaviours, improving the system’s ability to recognize context-specific actions and ultimately lead to more effective pedestrian models.

Moreover, enhancing avatars for visual variety by changing appearance, clothing, and accessories more frequently would add realism to the simulation, which is particularly useful in areas like driver training simulators. Including a more diverse range of pedestrians, such as children, elderly, and middle-aged people, who not only differ in speed but also in behavior, such as slow-moving elderly or impulsive children, would enhance the simulation. Finally, replicating this simulation in augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR) formats could transform it into an effective training tool, offering realistic scenarios for drivers. Furthermore, using AR / VR in urban planning research could help to understand how pedestrians interact with changes in city infrastructure.

Table 4.

Summary of Future Work Opportunities

Table 4.

Summary of Future Work Opportunities

| Category |

Opportunities |

| Data-related |

Collecting extensive pedestrian motion data across different Indian cities; Incorporating real-time sensor data for dynamic model updates; Including seasonal and time-of-day variations. |

| Model-related |

Adding additional pedestrian behaviours such as distraction, indecision, and reactions to noise; Enhancing interaction models between pedestrians and autonomous vehicles; Expanding diversity of pedestrians (children, elderly, etc.). |

| Simulation-related |

The system requires more advanced environments that include varied terrain features along with traffic control systems and scrambling obstacles from stray animals while improving efficiency through GPU-cloud processing and developing immersive training and urban development programs in AR/VR settings. |

5.1. Conclusion

The current work demonstrated the feasibility of modeling pedestrian behaviors under Indian road conditions using reinforcement and imitation learning techniques. By recording diverse pedestrian movements in busy areas such as marketplaces, residential neighborhoods, and walkways with zebra crossings, the simulation offers a realistic training environment for drivers, a testing ground for autonomous vehicle systems, and valuable insights for urban planning. Furthermore, the integration of RL and IL enables more realistic simulations of pedestrian behavior, which is crucial for preparing drivers to navigate through cities with dense pedestrian populations and unpredictable behaviors.

Overall, the current infrastructure is somewhat limited, yet provides a solid foundation for further enhancement of pedestrian behavior modeling. An advantage of this simulation is its potential applicability across various use-cases, benefiting from enhanced environmental complexity, computational speed, and a variety of scenarios. In conclusion, this simulation represents one of many efforts to develop AI tools aimed at creating safer, smarter, and more responsive urban traffic systems, ultimately offering drivers better knowledge, helping urban planners design more effective infrastructure and improving pedestrian safety.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.B.; software, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; validation, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; formal analysis, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; investigation, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; resources, P.H.B.; data curation, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, S.H, G.S, D.K, and D.M.; supervision, P.H.B.; project administration, P.H.B, and A.B; funding acquisition, P.H.B; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This project was carried out as an internally funded initiative and was carried out with the available resources at CAVE Labs, Center for IoT, PES University, Bengaluru. Department of Computer Science and Engineering provided us with the necessary administrative and academic support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andreychuk, A.; Yakovlev, K.; Panov, A.; Skrynnik, A. MAPF-GPT: Imitation Learning for Multi-Agent Pathfinding at Scale. Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny, Russia, 2024.

- Mahmoudi, R.; Ostreika, A. Reinforcement Learning for Obstacle Avoidance Application in Unity ML-Agents. Kaunas Technology University (KTU), Kaunas, Lithuania, 2023.

- Vozniak, I.; Klusch, M.; Antakli, A.; Muller, C. InfoSalGAIL: Visual Attention-Empowered Imitation Learning of Pedestrian behavior in Critical Traffic Scenarios. German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI), 2020.

- Cruz, J.A. Learning Realistic and Safe Pedestrian behavior by Imitation. Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2021.

- Vizzari, G.; Cecconello, T. Pedestrian Simulation with Reinforcement Learning: A Curriculum-Based Approach. Department of Informatics, Systems and Communication, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milano, Italy, 2022.

- Antakli, A.; Vozniak, I.; Lipp, N.; Klusch, M.; Muller, C. HAIL: Modular Agent-Based Pedestrian Imitation Learning. German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI), Saarbruecken, Germany, 2021.

- Nasernejad, P.; Sayed, T.; Alsaleh, R. Modelling Pedestrian behavior in Pedestrian-Vehicle Near Misses: A Continuous Gaussian Process Inverse Reinforcement Learning (GP-IRL) Approach. Department of Civil Engineering, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 2021.

- Renman, C. Creating Human-Like AI Movement in Games Using Imitation Learning. Master’s Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

- Mu, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, D.; Xu, D.; Li, X. Optimizing Pedestrian Simulation Based on Expert Trajectory Guidance and Deep Reinforcement Learning. 2022.

- AI Access Foundation. Modelling Human-Like Pedestrian behavior: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 2024.

- Mu, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, D.; Xu, D.; Li, X. Optimizing Pedestrian Simulation Based on Expert Trajectory Guidance and Deep Reinforcement Learning. GeoInformatica, 2023.

- Norambuena, P.R.; Bekios-Calfa, J.; Torres, J.M. Study of Machine Learning Techniques for Pedestrian Dynamics Simulation Models. 3rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition Systems (ICPRS) by IEEE, 2023.

- Qianyin, J.; Guoming, L.; Jinwei, Y.; Xiying, L. A Model-Based Method of Pedestrian Abnormal behavior Detection in Traffic Scenes. IEEE First International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), 2015.

- Papathanasopoulou, V.; Spyropoulou, I.; Perakis, H.; Gikas, V.; Andrikopoulou, E. A Data-Driven Model for Pedestrian behavior Classification and Trajectory Prediction. School of Rural, Surveying, and Geoinformatics Engineering (SRSE), National Technical University of Athens, Greece, 2021.

- Dimitrievski, M.; Veelaert, P.; Philips, W. behavioral Pedestrian Tracking Using a Camera and LiDAR Sensors on a Moving Vehicle. TELIN-IPI, Ghent University- imec, Belgium, 2019.

- Chaudhari, A.; Shah, J.; Arkatkar, S.; Joshi, G.; Parida, M. Investigating Effect of Surrounding Factors on Human behavior at Uncontrolled Mid-Block Crosswalks in Indian Cities. Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 2018.

- Jayaraman, S.K.; Robert Jr., L.P.; Yang, X.J.; Tilbury, D.M. Multimodal Hybrid Pedestrian: A Hybrid Automaton Model of Urban Pedestrian behavior for Automated Driving Applications. IEEE Access, 2021.

- Neubauer, M.; Ruddeck, G.; Schrab, K.; Protzmann, R.; Radusch, I. A Pedestrian Movement Model for 3D Visualization in a Driving Simulation Environment. Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 26th International Symposium on Distributed Simulation and Real Time Applications (DS-RT), 2022.

- Jin, C.-J.; Luo, Y.; Wu, C.; Song, Y.; Li, D. Exploring Pedestrian Route Choice behaviors by Machine Learning Models. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 13(5), 2024.

- Zhai, X.; Hu, Z.; Yang, D.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J. Social-Aware Multimodal Pedestrian Crossing behavior Prediction. Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision (ACCV), 2022.

- Lee, S.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Han, J. CNN-Based Crosswalk Pedestrian Situation Recognition System Using Mask-R-CNN and CDA. Applied Sciences, 13(4291), 2023.

- Mounsey, A.; Khan, A.; Sharma, S. Deep and Transfer Learning Approaches for Pedestrian Identification and Classification in Autonomous Vehicles. Electronics, 2021.

- Boda, P.; Ramadevi, Y. Predicting Pedestrian behavior at Zebra Crossings Using Bottom-Up Pose Estimation and Deep Learning. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering (IJISAE), 12(4s), 2024.

- Ghasemi, M.; Sorkhoh, I.; Alzhouri, F.; Moosavi, A.H.; Agarwal, A.; Ebrahimi, D. An Introduction to Reinforcement Learning: Fundamental Concepts and Practical Applications. Wilfrid Laurier University and Concordia University, 2024.

- Jaeger, B.; Geiger, A. An Invitation to Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv, Version 2, 2024.

- Sivamayil, K.; Rajasekar, E.; Aljafari, B.; Nikolovski, S.; Vairavasundaram, S.; Vairavasundaram, I. A Systematic Study on Reinforcement Learning-Based Applications. Energies, 2024.

- Gavenski, N.; Meneguzzi, F.; Luck, M.; Rodrigues, O. A Survey of Imitation Learning Methods, Environments, and Metrics. King’s College London, University of Aberdeen, and University of Sussex, 2024.

- Zare, M.; Kebria, P.M.; Khosravi, A.; Nahavandi, S. A Survey of Imitation Learning: Algorithms, Recent Developments, and Challenges. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 2024.

- Kielar, P.M.; Borrmann, A. An Artificial Neural Network Framework for Pedestrian Walking behavior Modeling and Simulation. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Pedestrian and Evacuation Dynamics (PED), 2018.

- Larter, S.; Queiroz, R.; Sedwards, S.; Sarkar, A.; Czarnecki, K. A Hierarchical Pedestrian behavior Model to Generate Realistic Human behavior in Traffic Simulation. University of Waterloo, Canada, 2022.

- Alozi, A.R.; Hussein, M. Active Road User Interactions with Autonomous Vehicles: Proactive Safety Assessment. Transportation Research Record, 2023.

- Artal-Villa, L.; Olaverri-Monreal, C. Vehicle-Pedestrian Interaction in SUMO and Unity3D. Proceedings of the WorldCIST’19 Conference, 2019.

- Olszewski, P.; Osinska, B.; Zielinska, A. Pedestrian Safety at Traffic Signals in Warsaw. Transportation Research Procedia, 2016.

- Torabi, F.; Warnell, G.; Stone, P. behavioral Cloning from Observation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-18), Stockholm, Sweden, 2018; pp. 4950–4957.

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347v2, 2017.

- Webster, J.; Amos, M. A Turing Test for Crowds. Royal Society Open Science, 7(8), 200307, 2020.

- Naderi, B. Monte Carlo Localization for Pedestrian Indoor Navigation Using a Map-Aided Movement Model. Master’s Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin, 2012.

- Sun, Y. Kinetic Monte Carlo Simulations of Bi-Directional Pedestrian Flow with Different Walk Speeds. Physica A, 549, 2020.

- Hanski, J.; Biçak, K.B. An Evaluation of the Unity Machine Learning Agents Toolkit in Dense and Sparse Reward Video Game Environments. Bachelor’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Campus Gotland, 2021.

- Yousif, Y. Hands-On Imitation Learning: From behavior Cloning to Multi-Modal Imitation Learning. Towards Data Science, 2024.

- Kennedy, W.G. Modelling Human behavior in Agent-Based Models. Krasnow Institute for Advanced Study, George Mason University, USA, 2011.

- Fuchs, A.; Passarella, A.; Conti, M. Modeling, Replicating, and Predicting Human behavior: A Survey. ACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive Systems, May 2023.

- Puentes, M.; Novoa, D.; Delgado Nivia, J.M.; Barrios Hernández, C.J.; Carrillo, O.; Le Mouël, F. Pedestrian behavior Modeling and Simulation from Real-Time Data Information. Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on CATAÏ - SmartData for Citizen Wellness, 2019.

- Kadali, B.R.; Vedagiri, P. Modelling Pedestrian Road Crossing behavior under Mixed Traffic Conditions. European Transport/Trasporti Europei, 55(3), 2013.

- Jain, A.; Gupta, A.; Rastogi, R. Pedestrian Crossing behavior Analysis at Intersections. International Journal for Traffic and Transport Engineering, 4(1), 103–116, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Barón, L.; Faria, S.; Sousa, E.; Freitas, E. Analysis of Pedestrians’ Road Crossing behavior in Social Groups. Transportation Research Record, 2678(3), 387–409, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, F.; Rinke, N.; Schiermeyer, C.; Friedrich, B.; Berkhahn, V. Modeling of Shared Space with Multi-Modal Traffic Using a Multi-Layer Social Force Approach. European Transport/Trasporti Europei, 85, 2025.

- Wang, J., Lv, W., Jiang, Y., & Huang, G. A cellular automata approach for modeling pedestrian-vehicle mixed traffic flow in urban city. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.06282.

- Vizzari, G., & Cecconello, T. Pedestrian Simulation with Reinforcement Learning: A Curriculum-Based Approach. Future Internet, 15(1), 12.

- Tai, L., Zhang, J., Liu, M., & Burgard, W. Socially Compliant Navigation through Raw Depth Inputs with Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.02543.

- Terzopoulos, D., & Yu, Q. A Decision Network Framework for the behavioral Animation of Virtual Humans. Proceedings of the 2007 ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation, 119–128.

- Ng, A. Y., & Russell, S. J. Algorithms for Inverse Reinforcement Learning. Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference on Machine Learning, 663–670.

- MLJourney. XGBoost vs LightGBM: Detailed Comparison. 2023. Available online: https://mljourney.com/xgboost-vs-lightgbm-detailed-comparison.

- MLJourney. LightGBM vs XGBoost vs CatBoost: A Comprehensive Comparison. 2023. Available online: https://mljourney.com/lightgbm-vs-xgboost-vs-catboost-a-comprehensive-comparison.

- Konrad, S.G.; Masson, F.R. Pedestrian Skeleton Tracking Using OpenPose and Probabilistic Filtering. *IEEE Biennial Congress of Argentina (ARGENCON)* **2020**,.

- (2013, November 20). Pedestrianising Avenue Road. Deccan Herald.https://www.deccanherald.com/content/370143/pedestrianising-avenue-road.html.

- Unity Technologies. Best Practice Guide: Making believable visuals—Scale. Unity Documentation, 2019. Available online: https://docs.unity3d.com/2019.3/Documentation/Manual/BestPracticeMakingBelievableVisuals1.html.

- Fuchs, M.; Schmid, P.; Bär, D. Human-Centered AI for Transportation: A Review. *Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies*, 2023, 144, 103908.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D. Trust and Transparency in AI: A Systematic Review. *Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research*, 2021, 70, 891–937.

- Glikson, E.; Woolley, A. W. Human Trust in Artificial Intelligence: Review of Empirical Research. *Academy of Management Annals*, 2020, 14(2), 627–660.

- Schmidt, A.; Müller, V. C. Explainable AI: From black box to glass box. *AI & Society*, 2022, 37, 585–595.

- Lee, J. D.; See, K. A.; Adams, J. A. Human-Autonomy Teaming: Challenges and Opportunities. *Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems*, 2023, 6, 1–27.

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H. Human Behavior Recognition Using Deep Learning: A Survey. *Pattern Recognition Letters*, 2022, 154, 33–40.

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X. Natural Evasion Model (NEM) for Adversarial Strategy Simulation in Security Systems. *Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Security*, 2022, 15(3), 115–126.

- Green, P. A.; Kang, T. P.; Jeong, H. Using an OpenDS Driving Simulator for Car Following: A First Attempt. AutomotiveUI 2014 - 6th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, in Cooperation with ACM SIGCHI - Adjunct Proceedings, 2014, pp. 64–69.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).