Submitted:

10 May 2025

Posted:

12 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Authors/year | Cogeneration | Energy sources | Working fluids | Net power and Hydrogen production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yilmaz et al.[16] (2024) | Geothermal cycle + ORC + PEME+ OD (SiM) (Green hydrogen, freshwater and heat) |

Geothermal | Organic fluid +water | 2046 kW; 0.002367 kg/s |

| Sabbaghi and Sefid [17] (2024) | ORC+PEME (SiM) (Electricity and green hydrogen) |

Geothermal | Carbon dioxide | 3.99 lit/s |

| Hajabdollahi et al. [18] (2023) | Reverse osmosis desalination +ORC+PEME (SiM) (Electricity, heating, hydrogen and freshwater) |

Geothermal | Organic fluid | 1556.2 kW; 0.42 m3/day |

| Wenqiang Li et al. [19] (2024) | Double-flash cycle+ PEME+PTC (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Geothermal | Water | 25.48 kg/h |

| Arslan et al.[20] (2024) | Geothermal Power Plant (AFJES) +PEME (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Geothermal | Water | 4132 kW; 150 kg/s |

| Kun Li et al.[21] (2022) | Flash-binary geothermal cycle +ERC+ (KC+ERC) +PEME (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen, cooling and freshwater) |

Geothermal | Water + Ammonia-water | 782 kW; 0.181 kg/h |

| Almutairi et al. [22] (2021) | Flash-binary geothermal cycle +ORC+PEME (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Geothermal | Organic fluid+ Water | 128.16 kW; 0.39626 kg/h |

| Gao et al. [23] (2024) | Steam-methanol reforming +KC + Flash-binary geothermal cycle (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen and freshwater) |

Geothermal -Solar | Ammonia-water | 215.9 kW; 0.0224 kg/s |

| Shubo Zhang et al. [24] (2023) | Parabolic trough solar collectors (PTSC)+KC+PEME+ARC (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen and hot water) |

Geothermal, biomass, Solar | Ammonia-water | 3.71 MW; 11.42 kg/h |

| Laleh et al.[25] (2023) | Brayton cycle +ORC+RC (CoM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Biomass | LNG, Organic fluid, Water | 10 MW; 0.66 kg/s |

| Wang et al.[26] (2022) | RC+PEME+ Solid oxide electrolyzer (SOE) + Multi-effect desalination (MED) (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen and freshwater) |

Biomass | Water | 1735 kW; 9880 kg/h |

| Karthikeyan et al. [27] (2024) | Heat pump+ ORC+PEME (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen and heat) |

Biomass-Solar | Organic fluid | 815 kW; 3 kg/h |

| Sharifishourabi et al. [28] (2025) | KC + Alkaline electrolyzer + Refrigeration cycle (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen, cooling and heat) |

Biomass-Wind | Ammonia-water | 5.38 kg/h |

| Forootan et al. [29] (2024) | ORC+PEME+ Brayton cycle+ Multi-effect distillation (SiM) (Electricity, oxygen, hydrogen, hot water and freshwater) |

Solar | Organic fluid | 133 MW; 201.6 kg/h |

| Bamisile et al.[30] (2020) | 2 RC+PEME + SE-ARC+ DE-ARC+ PTC (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen, hot water and freshwater) |

Solar | Water | 1027 kW; 0.9785 kg/h |

| Lykas et al. [31] (2023) | ORC+PEME (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Solar | Organic fluid | 24 kW; 0.205 kg/h |

| Mansir [32] (2024) | Brayton cycle+ PVT+ KC+PEME (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Solar | Carbon dioxide +NH3H2O | 33585 kW; 16.90 kg/day |

| Colakoglu and Durmayaz [33] (2022) | Solar-tower+ Brayton cycle +RC+KC (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Solar | Organic fluid +NH3H2O | 1478 kW; 22.48 kg/h |

| Sharifishourabi et al. [15] (2024) | RC+PEME +ORC+ PTC+KC (CoM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Solar | Organic fluid +NH3H2O | 1957 kW; 1 kg/h |

| Effatpanah et al. [34] (2023) | advanced alkaline electrolyzer (AAE) system +ORC+ARC+CPV/T system (SiM) (Electricity, hydrogen and cooling) |

Solar-Wind | LiBr-H2O and organic fluid | 315 kW; 1.012 kg/s |

| Gargari et al. [35] (2018) | Gas Turbine-Modular Helium Reactor (GT-MHR) and a biogas steam reforming (BSR) (SiM) (Electricity and hydrogen) |

Biogas | methane and carbon dioxide | 260.13 MW; 0.217 kg/s |

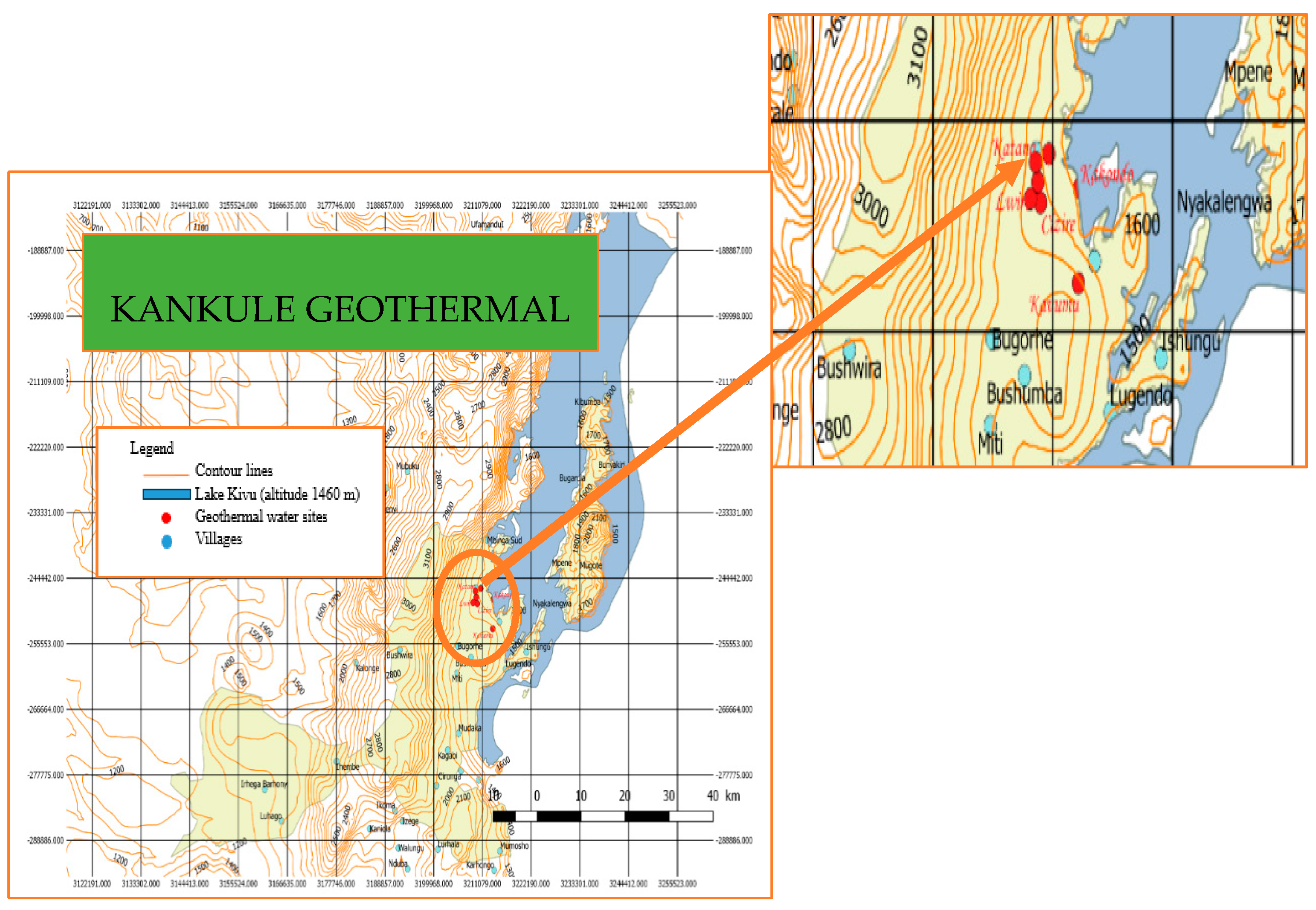

2. Geothermal Potential in the DRC

- 90°C corresponds to 1019.21 m.

- 100°C corresponds to 1231.54 m

- 195°C corresponds to 3333.66 m.

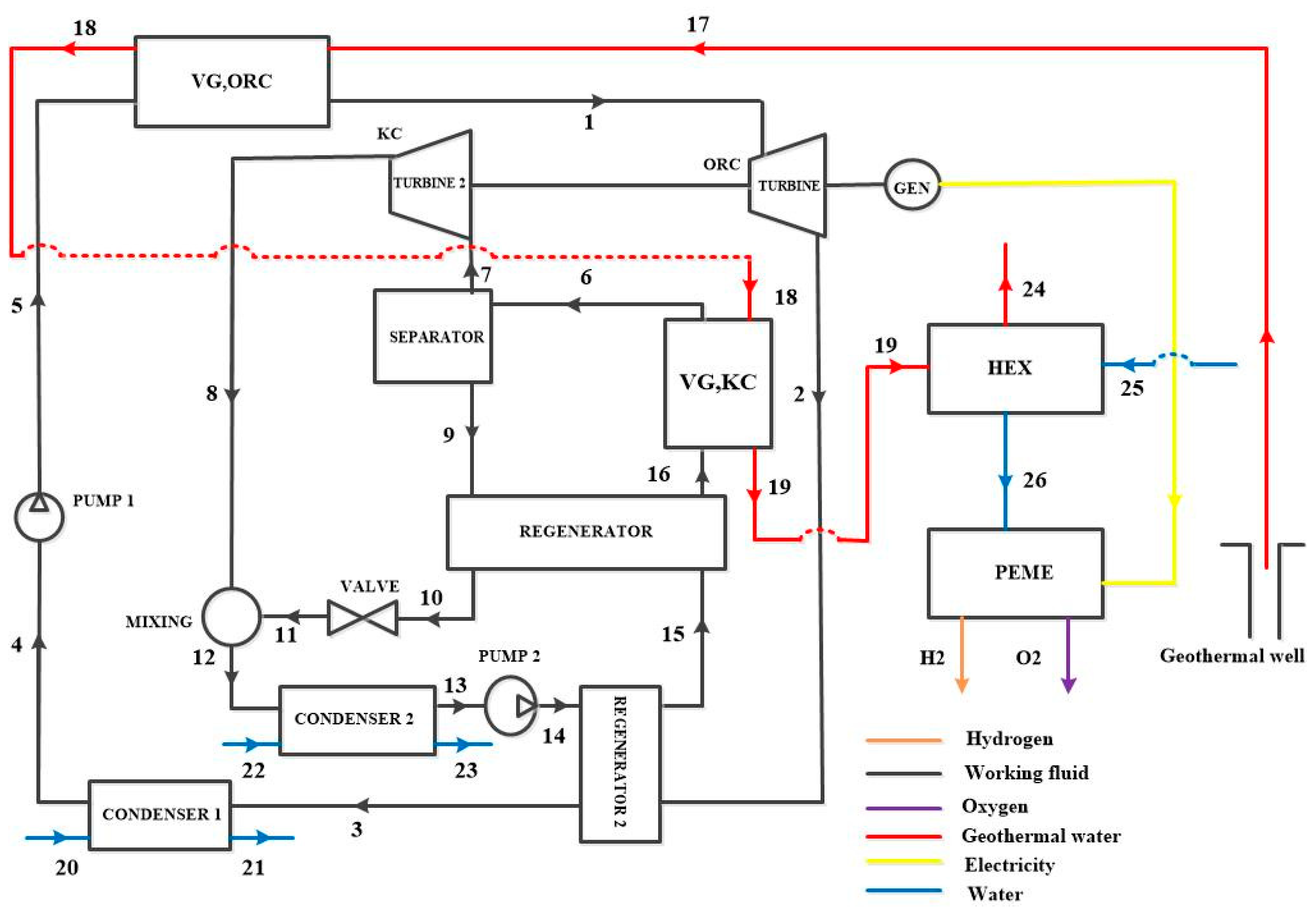

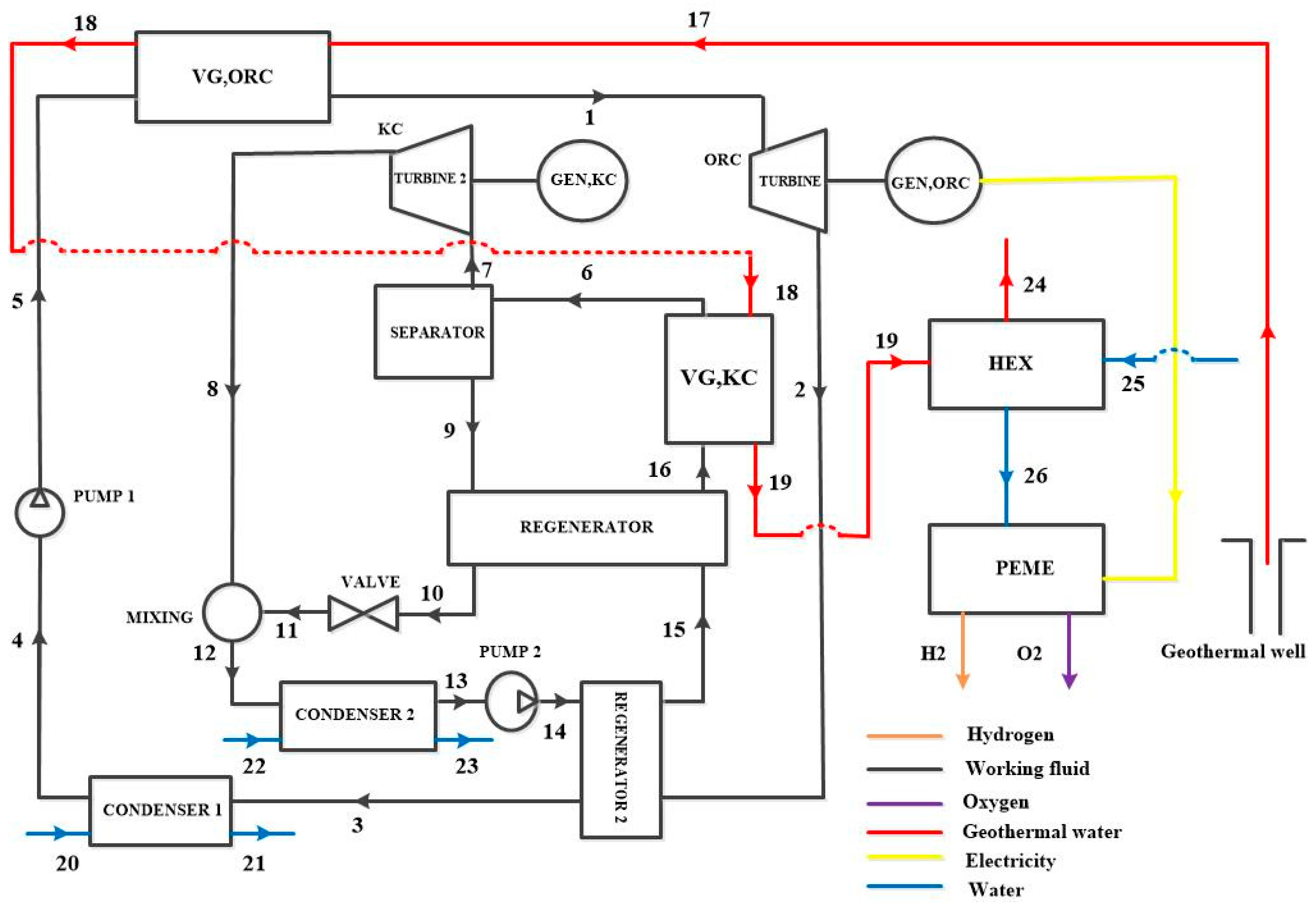

3. System Description

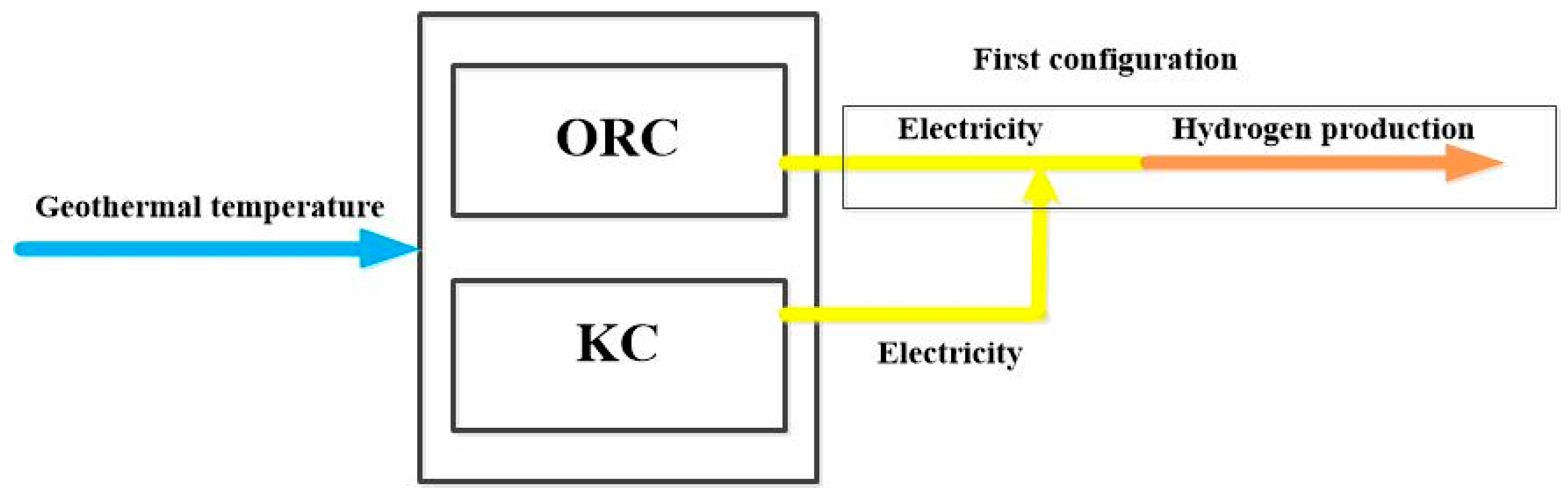

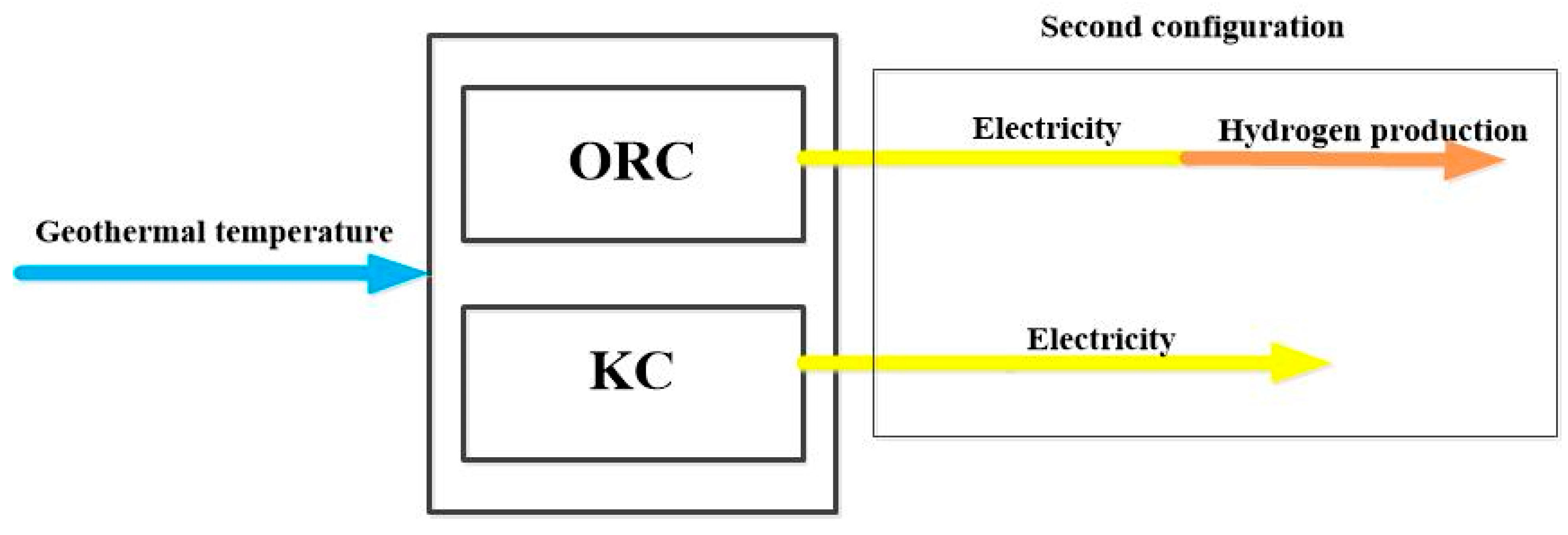

3.1. Configurations Under Study

3.2. Working Fluid Selection

4. Modeling system

4.1. Assumptions

- The model operates under steady-state conditions;

- Pressure drops in all components are neglected;

- The vapor at the turbine inlet is considered to be in a state of dry saturation;

- It is assumed that the fluid leaving the condensers is saturated;

- Flow through throttle valves is isenthalpic

4.2. Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer (PEME)

4.3. Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) and Kalina Cycle (KC) Modeling

4.3.1. Energy Modeling

4.3.2. Exergy Modeling

5. Optimization

6. Results and discussion

6.1. Validation Model

6.2. Thermodynamic Results

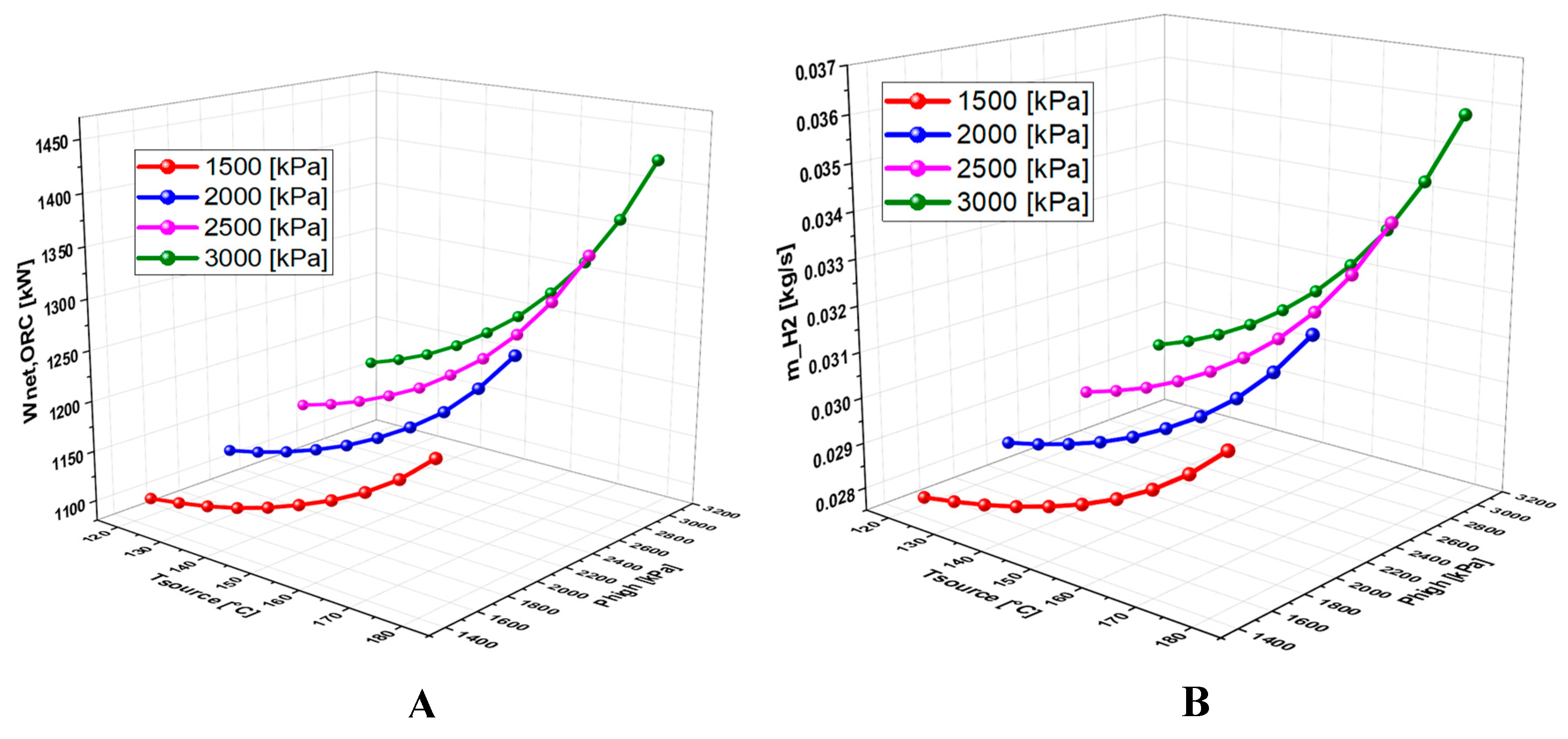

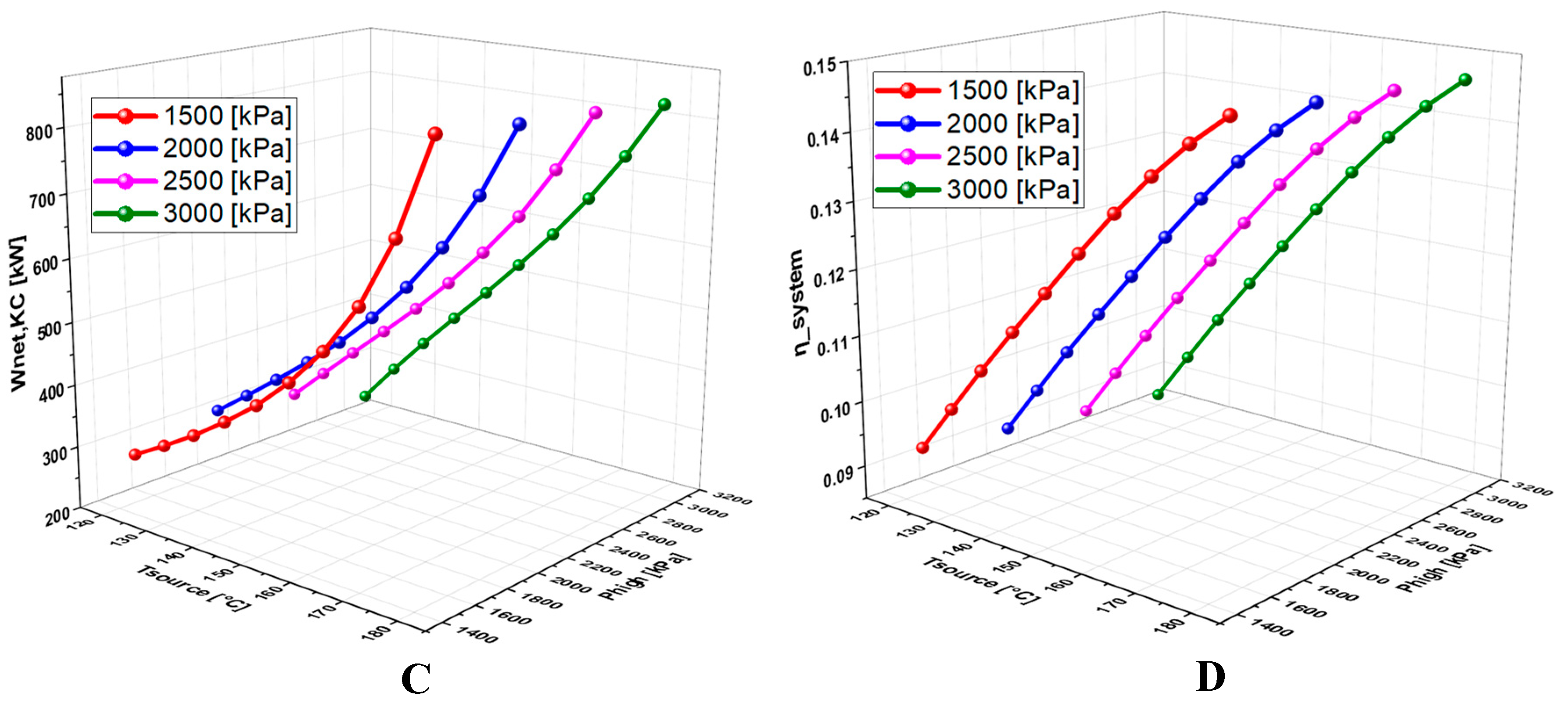

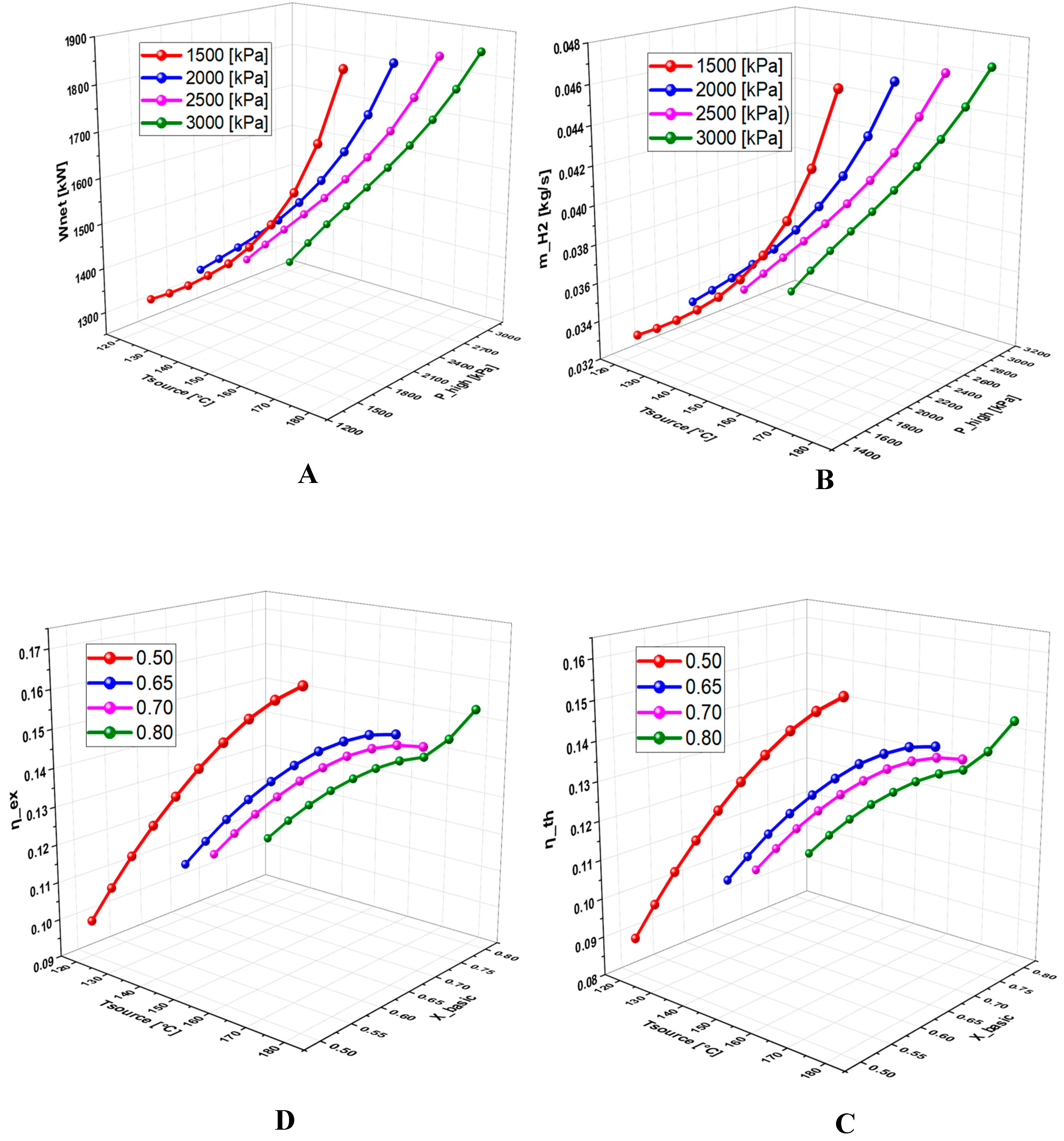

6.2.1. Overall Thermodynamic Evaluation Results

6.2.2. Effect of Operating Conditions on Thermodynamic Quantities and Exergetic Analysis

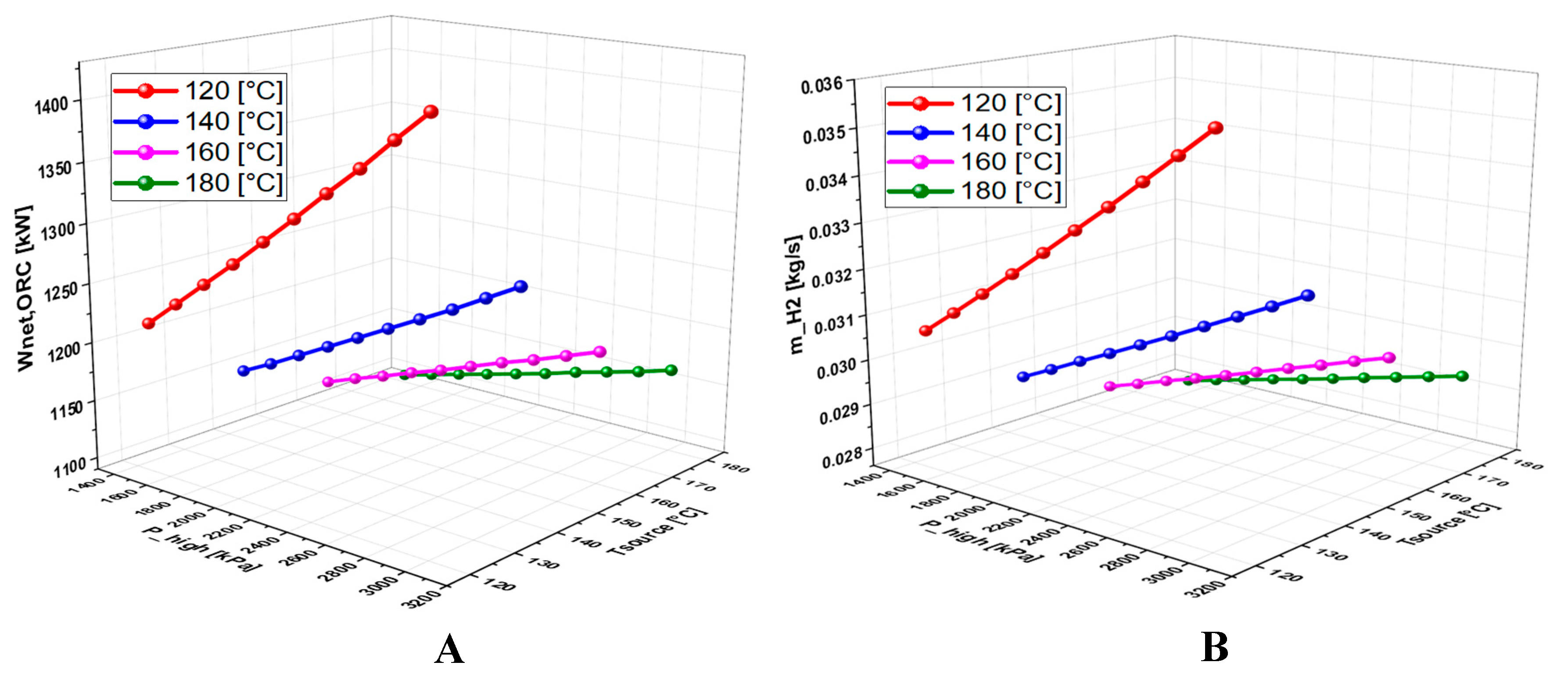

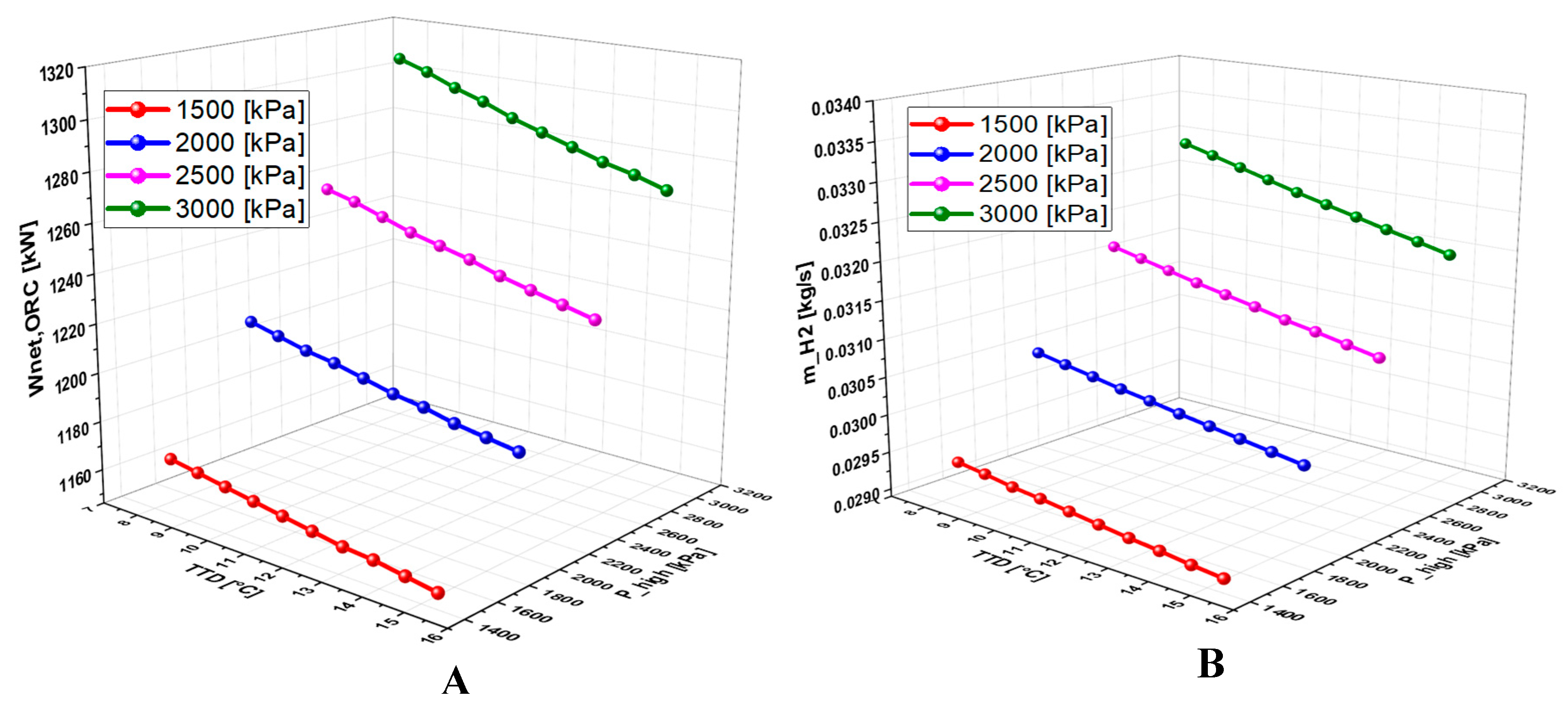

6.2.3. Effect of Geothermal Temperature on the System Performance

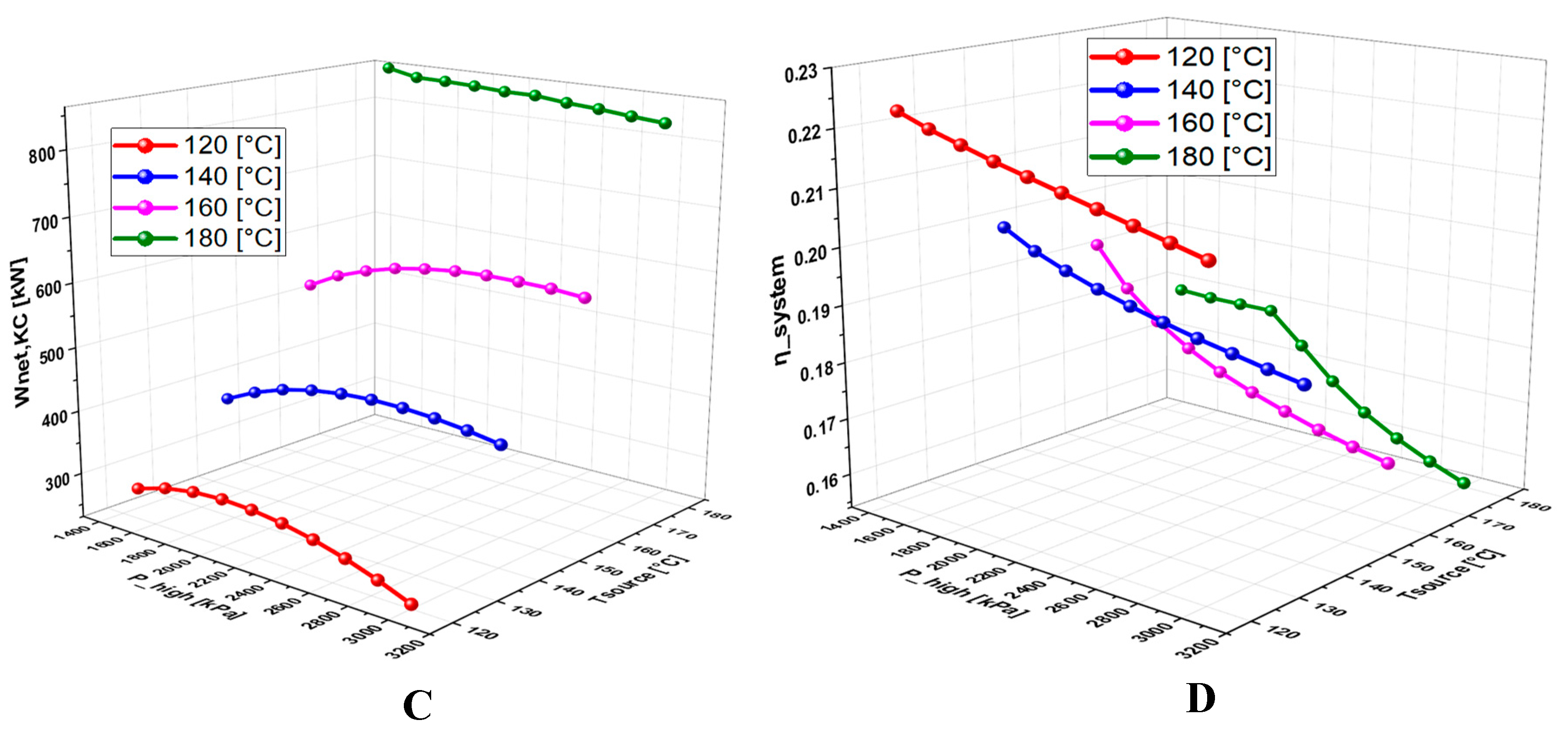

6.2.3. Effect of High Pressure on System Performance

6.2.4. Effect of Basic Concentration on the System Performance

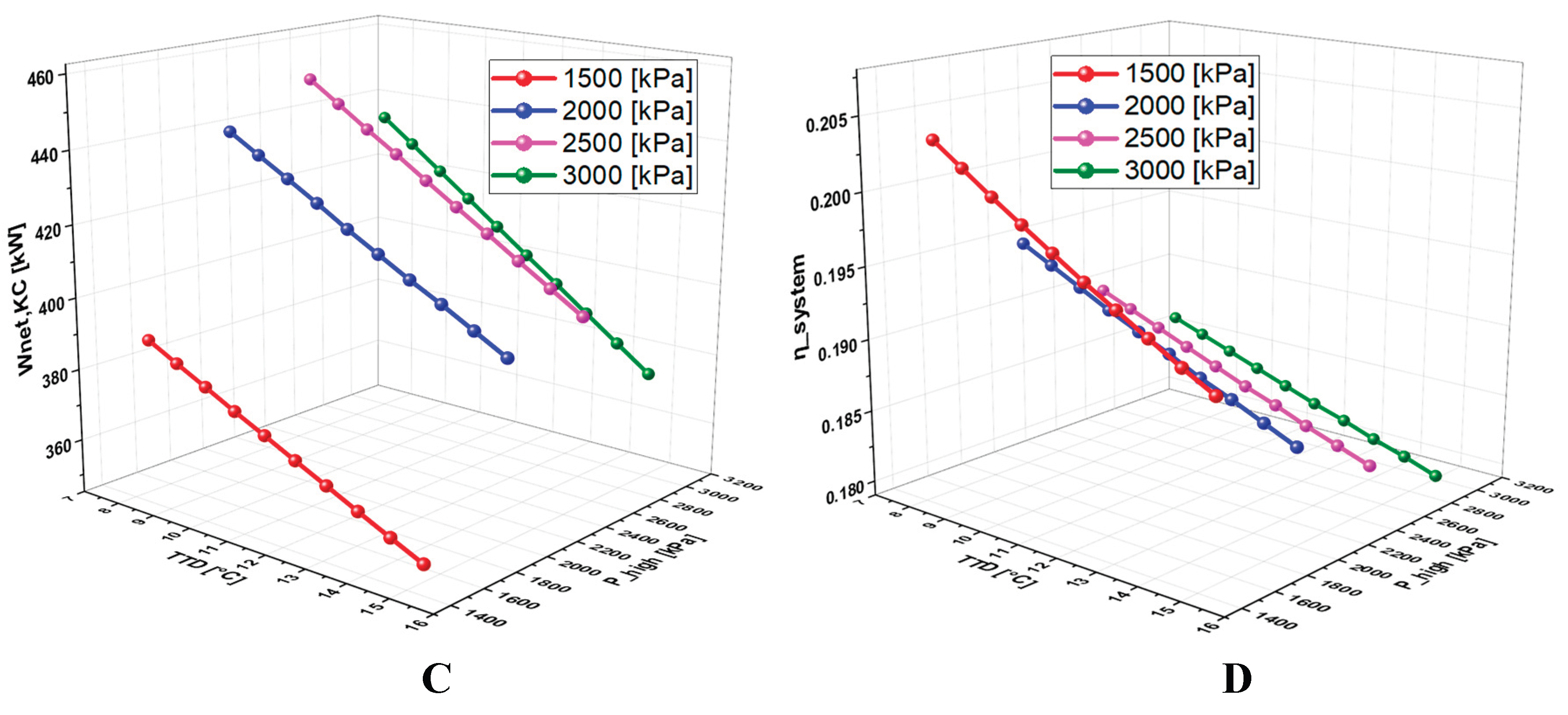

6.2.5. Effect of Terminal Temperature Difference (TTD) on the System Performance

6.3. Optimization Results

6.4. Effect of the Separation of Turbines on the System Performance

6.4.1. Effect of Geothermal Temperature on the System Performance

6.4.2. Effect of High Pressure on the System Performance

6.4.3. Effect of TTD on the System Performance

7. Conclusions

- Under the same operating conditions, the combination of ammonia-water mixture and MD2M allowed to achieve the best performance after simulation compared to the other combinations, with a net power of 1470 kW and a hydrogen production of 0.03697 kg/s (3194.208 kg/day).

- Optimization results show that among the different combinations analyzed, the combination of ammonia-water + R152a offers the best performance, with a net power of 2016 kW and a hydrogen production of 0.05049 kg/s (4362.336 kg/day). It is followed by the ammonia-water + MD2M combination.

- The combination ammonia-water + R152a further provides a significant improvement in the system performance, with a 7.922% increase in net power and a 7.8% improvement in hydrogen combination.

- Furthermore, adjusting the reference temperature to a maximum of 179.9°C leads to an increase in energy efficiency from 12 % to 15 % and a decrease in the total exergy destruction rate to 14574 kW from 14828 Kw.

- Optimization results also indicate that the optimum ammonia concentration for the proposed system is between 0.50 and 0.51 for different combinations.

- A detailed study of the evolution of the system performance as a function of the main parameters investigated over various ranges of variation revealed that the geothermal temperature is the parameter with the most significant impact on the overall operation of the system.

- In case of turbine separation, the production of hydrogen reaches 0.03112 kg/s (2687 kg/day), which is significantly lower than the production obtained with the combined turbines, i.e. a reduction of 15%. The electricity needed from the ORC amounts 1235 kW, and the power generated from the KC is about 435.5 kW say 35.26 %. It is worthy noting that in case of coupled turbines, the amount of electricity is of 1470 kW.

- Comparing the performance of the proposed cycle combinations with the existing one without accounting for the economic part, it turns out this cycle performs better and is simply flexible as the amount of electricity to be allocated for the hydrogen production can vary between 1235 and 1470 kW.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Nomenclature | |

| EES | Engineering Equation Solver |

| F | faraday constant |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| GEN | Generator |

| h | enthalpy (kJ/kg) |

| HEX | exchanger |

| J | current density |

| KC | Kalina cycle |

| LHV | Lower heating value |

| mass flow rate (kg/s) | |

| Hydrogen production rate (kg/s), (kg/day) | |

| ORC | Organic Rankine cycle |

| P | Pressure (kPa) |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| PEME | Proton exchange membrane electrolyzer |

| heat flow (kW) | |

| reg | regenerator |

| s | entropy (kJ/kg K) |

| T0 | ambient temperature (◦C) |

| T | temperature (◦C) |

| TTD | terminal temperature difference (°C) |

| VG | vapor generator |

| VG | overpotential (V) |

| V_O | reversible potential (V) |

| V_act,a | cathode overpotential (V) |

| V_act,c | anode overpotential (V) |

| V_ohm | ohmic overpotential (V) |

| W | Power (KW) |

| Wnet | power net (KW) |

| Greek letters | |

| η | efficiency (%) |

| ε | effectiveness |

| Subscripts | |

| cond | condenser |

| ex | exergy |

| gen | generator |

| in | inlet |

| out | outlet |

| th | thermal |

References

- M. K. Singla, P. Nijhawan, and A. S. Oberoi, “Hydrogen fuel and fuel cell technology for cleaner future: a review,” Environ Sci Pollut Res, vol. 28, no. 13, pp. 15607–15626, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Yukesh Kannah et al., “Techno-economic assessment of various hydrogen production methods – A review,” Bioresource Technology, vol. 319, p. 124175, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Dash, S. Chakraborty, and D. Elangovan, “A Brief Review of Hydrogen Production Methods and Their Challenges,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 1141, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu Wen, Louis Dressler, Andreas Dreizler, Amsini Sadiki, Johannes Janicka, Christian Hasse: Flamelet LES of turbulent premixed/stratified flames with H2 addition, Combustion and Flame, Volume 230, August 2021, 111428.

- B. S. Zainal et al., “Recent advancement and assessment of green hydrogen production technologies,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 189, p. 113941, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Aravindan and G. Praveen Kumar, “Optimizing novel green hydrogen production from solar and municipal solid waste: A thermo-economic investigation with environmental comparison between integrated low temperature power cycles,” Process Safety and Environmental Protection, vol. 186, pp. 421–447, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Baral and J. Šebo, “Techno-economic assessment of green hydrogen production integrated with hybrid and organic Rankine cycle (ORC) systems,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e25742, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hassan, A. Z. Sameen, H. M. Salman, and M. Jaszczur, “Large-scale green hydrogen production via alkaline water electrolysis using solar and wind energy,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 48, no. 88, pp. 34299–34315, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Karthikeyan and G. Praveen Kumar, “Thermoeconomic and optimization approaches for integrating cooling, power, and green hydrogen production in dairy plants with a novel solar-biomass cascade ORC system,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 295, p. 117645, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Elrhoul, M. Naveiro, M. R. Gómez, and T. A. Adams, “Thermo-economic analysis of green hydrogen production onboard LNG carriers through solid oxide electrolysis powered by organic Rankine cycles,” Applied Energy, vol. 380, p. 124996, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Alirahmi, E. Assareh, N. N. Pourghassab, M. Delpisheh, L. Barelli, and A. Baldinelli, “Green hydrogen & electricity production via geothermal-driven multi-generation system: Thermodynamic modeling and optimization,” Fuel, vol. 308, p. 122049, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Hai et al., “Combination of a geothermal-driven double-flash cycle and a Kalina cycle to devise a polygeneration system: Environmental assessment and optimization,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 228, p. 120437, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Madhesh et al., “Analysis and multi-objective evolutionary optimization of Solar-Biogas hybrid system operated cascade Kalina organic Rankine cycle for sustainable cooling and green hydrogen production,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 301, p. 117999, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Saoud, Y. Boukhchana, J. C. Bruno, and A. Fellah, “Thermodynamic investigation of an innovative solar-driven trigeneration plant based on an integrated ORC-single effect-double lift absorption chiller,” Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, vol. 50, p. 102596, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Sharifishourabi, I. Dincer, and A. Mohany, “A novel trigeneration energy system with two modes of operation for thermal energy storage and hydrogen production,” Energy, vol. 304, p. 132121, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Yilmaz, M. Ozturk, and R. Selbas, “A parametric examination of the energetic, exergetic, and environmental performances of the geothermal energy-based multigeneration plant for sustainable products,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, p. S0360319924054430, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Sabbaghi and M. Sefid, “Thermo-economic analysis of a combined flash-binary geothermal cycle with a transcritical CO2 cycle to produce green hydrogen,” IJEX, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 110–122, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Hajabdollahi, A. Saleh, and M. Shafiey Dehaj, “A multi-generation system based on geothermal driven: energy, exergy, economic and exergoenvironmental (4E) analysis for combined power, freshwater, hydrogen, oxygen, and heating production,” Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 26415–26447, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Li et al., “Enhancing green hydrogen production via improvement of an integrated double flash geothermal cycle; Multi-criteria optimization and exergo-environmental evaluation,” Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, vol. 59, p. 104538, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Arslan and C. Yilmaz, “Development of models for green hydrogen production of Turkey geothermal Resources: A case study demonstration of thermodynamics and thermoeconomics analyses,” Fuel, vol. 359, p. 130430, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Li, Y.-Z. Ding, C. Ai, H. Sun, Y.-P. Xu, and N. Nedaei, “Multi-objective optimization and multi-aspect analysis of an innovative geothermal-based multi-generation energy system for power, cooling, hydrogen, and freshwater production,” Energy, vol. 245, p. 123198, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Almutairi, S. S. Hosseini Dehshiri, A. Mostafaeipour, A. Issakhov, K. Techato, and J. Arockia Dhanraj, “Performance optimization of a new flash-binary geothermal cycle for power/hydrogen production with zeotropic fluid,” J Therm Anal Calorim, vol. 145, no. 3, pp. 1633–1650, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao, Y. Zhang, X. Li, X. Zhou, and Z. J. Kilburn, “Thermodynamic and thermoeconomic analysis and optimization of a renewable-based hybrid system for power, hydrogen, and freshwater production,” Energy, vol. 295, p. 131002, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, W. Jian, J. Zhou, J. Li, and G. Yan, “A new solar, natural gas, and biomass-driven polygeneration cycle to produce electrical power and hydrogen fuel; thermoeconomic and prediction approaches,” Fuel, vol. 334, p. 126825, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharafi Laleh, F. P. Gharamaleki, S. F. Alavi, S. Soltani, S. M. S. Mahmoudi, and M. A. Rosen, “A novel sustainable biomass-fueled cogeneration cycle integrated with carbon dioxide capture utilizing LNG regasification and green hydrogen production via PEM electrolysis: Thermodynamic assessment,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 421, p. 138529, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, H. Lin, A. M. Abed, A. Sharma, and H. Fooladi, “Exergoeconomic assessment of a biomass-based hydrogen, electricity and freshwater production cycle combined with an electrolyzer, steam turbine and a thermal desalination process,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 47, no. 79, pp. 33699–33718, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Karthikeyan, G. Praveen Kumar, R. Narayanan, S. R, and A. Coronas, “Thermo-economic optimization of hybrid solar-biomass driven organic rankine cycle integrated heat pump and PEM electrolyser for combined power, heating, and green hydrogen applications,” Energy, vol. 299, p. 131436, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Sharifishourabi, I. Dincer, and A. Mohany, “Development of a novel biomass-wind energy system for clean hydrogen production along with other useful products for a residential community,” Energy and Built Environment, p. S2666123325000091, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- . M. Forootan and A. Ahmadi, “Machine learning-based optimization and 4E analysis of renewable-based polygeneration system by integration of GT-SRC-ORC-SOFC-PEME-MED-RO using multi-objective grey wolf optimization algorithm and neural networks,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 200, p. 114616, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bamisile, Q. Huang, W. Hu, M. Dagbasi, and A. D. Kemena, “Performance analysis of a novel solar PTC integrated system for multi-generation with hydrogen production,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 190–206, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Lykas, N. Georgousis, A. Kitsopoulou, D. N. Korres, E. Bellos, and C. Tzivanidis, “A Detailed Parametric Analysis of a Solar-Powered Cogeneration System for Electricity and Hydrogen Production,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 433, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Mansir, “Thermodynamic investigation of novel hybrid plant with hydrogen as a green energy carrier,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 51, pp. 1171–1180, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Colakoglu and A. Durmayaz, “Energy, exergy and economic analyses and multiobjective optimization of a novel solar multi-generation system for production of green hydrogen and other utilities,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 47, no. 45, pp. 19446–19462, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Khojaste Effatpanah, H. R. Rahbari, M. H. Ahmadi, and A. Farzaneh, “Green hydrogen production and utilization in a novel SOFC/GT-based zero-carbon cogeneration system: A thermodynamic evaluation,” Renewable Energy, vol. 219, p. 119493, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Gargari, M. Rahimi, and H. Ghaebi, “Thermodynamic analysis of a novel power-hydrogen cogeneration system,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 171, pp. 1093–1105, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Makuku, “Inventory of geothermal sources in the DRC and their development plan for the electrification of locals areas. Case of the eastern part of the DRC,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 249, p. 012016, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pacifique S Mukandala and C. K. Mahinda, “Geothermal Development in the Democratic Republic of the Congo-a Country Update,” 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Mbuto, Y.-Y. Albert, and K. Albert, “Etude Differentielle Des Sites Geothermiques De Kankule A Katana Au Sud-Kivu I. Revue De La Litterature,” pp. 2278–4861, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Mergner and T. Weimer, “Performance of ammonia–water based cycles for power generation from low enthalpy heat sources,” Energy, vol. 88, pp. 93–100, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Chaboki, A. Khoshgard, G. Salehi, and F. Fazelpour, “Thermoeconomic analysis of a new waste heat recovery system for large marine diesel engine and comparison with two other configurations,” Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 10159–10184, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Rostamzadeh, H. Ghaebi, S. Vosoughi, and J. Jannatkhah, “Thermodynamic and thermoeconomic analysis and optimization of a novel dual-loop power/refrigeration cycle,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 138, pp. 1–17, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bamisile et al., “Thermo-environ study of a concentrated photovoltaic thermal system integrated with Kalina cycle for multigeneration and hydrogen production,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 45, no. 51, pp. 26716–26732, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H.-R. Bahrami and M. A. Rosen, “Exergoeconomic evaluation and multi-objective optimization of a novel geothermal-driven zero-emission system for cooling, electricity, and hydrogen production: capable of working with low-temperature resources,” Geotherm Energy, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 12, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Ni, M. K. H. Leung, and D. Y. C. Leung, “Energy and exergy analysis of hydrogen production by a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer plant,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 2748–2756, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- M. Taheripour, M. Kahani, and M. H. Ahmadi, “A hybrid poly-generation system for power and hydrogen production by thermal recovery from waste streams in a steel plant: Techno-economic analysis,” Energy Reports, vol. 11, pp. 2921–2934, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Nami, E. Akrami, and F. Ranjbar, “Hydrogen production using the waste heat of Benchmark pressurized Molten carbonate fuel cell system via combination of organic Rankine cycle and proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 114, pp. 631–638, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Bejan, G. Tsatsaronis, and M. J. Moran, Thermal design and optimization. in A Wiley-Interscience publication. New York: Wiley, 1996.

- M. Javad Dehghani, “Enhancing energo-exergo-economic performance of Kalina cycle for low- to high-grade waste heat recovery: Design and optimization through deep learning methods,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 195, p. 117221, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sadiki and F. Ries, “Entropy Generation Analysis in Turbulent Reacting Flows and Near Wall: A Review,” Entropy, vol. 24, no. 8, p. 1099, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Shankar and W. Rivera, “Investigation of new cooling cogeneration cycle using NH3H2O mixture,” International Journal of Refrigeration, vol. 114, pp. 88–97, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Srinivas, N. Shankar Ganesh, and R. Shankar, Flexible Kalina Cycle Systems, 0 ed. Apple Academic Press, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, R. A. Taylor, G. L. Morrison, and S. D. White, “A comprehensive, multi-objective optimization of solar-powered absorption chiller systems for air-conditioning applications,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 132, pp. 281–306, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Sharifi, F. Nozad Heravi, R. Shirmohammadi, R. Ghasempour, F. Petrakopoulou, and L. M. Romeo, “Comprehensive thermodynamic and operational optimization of a solar-assisted LiBr/water absorption refrigeration system,” Energy Reports, vol. 6, pp. 2309–2323, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Ghaebi, T. Parikhani, H. Rostamzadeh, and B. Farhang, “Proposal and assessment of a novel geothermal combined cooling and power cycle based on Kalina and ejector refrigeration cycles,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 130, pp. 767–781, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Gogoi and P. Hazarika, “Comparative assessment of four novel solar based triple effect absorption refrigeration systems integrated with organic Rankine and Kalina cycles,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 226, p. 113561, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Ghaebi, A. S. Namin, and H. Rostamzadeh, “Exergoeconomic optimization of a novel cascade Kalina/Kalina cycle using geothermal heat source and LNG cold energy recovery,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 189, pp. 279–296, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Ghaebi, B. Farhang, T. Parikhani, and H. Rostamzadeh, “Energy, exergy and exergoeconomic analysis of a cogeneration system for power and hydrogen production purpose based on TRR method and using low grade geothermal source,” Geothermics, vol. 71, pp. 132–145, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Akrami, A. Chitsaz, P. Ghamari, and S. M. S. Mahmoudi, “Energy and exergy evaluation of a tri-generation system driven by the geothermal energy,” J Mech Sci Technol, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 401–408, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Soleymani, S. Ghavami Gargari, and H. Ghaebi, “Thermodynamic and thermoeconomic analysis of a novel power and hydrogen cogeneration cycle based on solid SOFC,” Renewable Energy, vol. 177, pp. 495–518, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Sites | Temperatures [°C] | Depth [m] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kankule [38] | Kankule 1 | 90-203 | 1019,21-3514,15 |

| Upemba-Moero-Tanganyika [37] | Tanganyika | 40-50 | |

| Upemba | 70-100 | ||

| Kivu-Edouard [37] | Kivu-Edouard | 20-100 | |

| Rwenzori [37] | Soixante sites | 20-100 | |

| Virunga [37] | Mayi-ya- Moto | 96 | |

| Kahuzi Biega Ruzizi [37] | Nyangezi | 40 | |

| Uvira | 44 |

| Working fluids | Molar mass [kg/kmol] |

[°C] |

[Bar] |

ODP | GWP [100/yr] |

ASHRAE |

| R236fa | 152.04 | 124.85 | 32 | 0 | 6300 | - |

| MD2M | 310.7 | 326.3 | 11.44 | 0 | 1 | A1 |

| ISOBUTANE | 58.13 | 134.66 | 36.29 | 0 | 20 | A3 |

| R152a | 66.05 | 113..30 | 45.2 | 0 | 12.4 | A2 |

| ISOBUTENE | 56.13 | 144.7 | 40 | - | 3 | - |

| Parameters | Value | Unit |

| Reference temperature, T0 | 25 | °C |

| Reference pressure, P0 | 101.3 | kPa |

| Geothermal inlet temperature, T_source | 140 | °C |

| Geothermal water mass flow rate, m_geo | 100 | kg/s |

| Terminal temperature difference, TTD | 10 | °C |

| Basic ammonia mass fraction, Xbasic | 65 | % |

| Regenerators effectiveness 1 and 2, εReg | 95 | % |

| High pressure, P_high | 2500 | kPa |

| Turbines isentropic efficiency, ηTur | 87 | % |

| Pumps isentropic efficiency, ηPump | 75 | % |

| Temperature of condenser 1 | 30 | °C |

| Exchanger, Hex | 80 | % |

| Basic mixture mass flow rate, m_basic | 5 | kg/s |

| Anode activation energy, Eacta | 76 | (kJ/kg) |

| Cathode activation energy, Eactc | 18 | (kJ/kg) |

| Anode pre-exponential factor, Jre,a | 1.7×105 | (A/m2) |

| Cathode pre-exponential factor, Jref,c | 4.6×103 | (A/m2) |

| Faraday constant, F | 96,486 | (C/mol) |

| Components | First Low Equations | Second Low Equations |

| Vapor generator, KC | ||

| Vapor generator, ORC | ||

|

Separator |

|

|

|

Turbine, ORC |

|

|

| Turbine, KC | ||

|

Pump 1 |

|

|

| Pump 2 | ||

|

Regenerator |

|

|

|

Regenerator 2 |

||

| Valve 1 | ||

|

Mixer 1 |

|

|

|

Condenser 1 |

||

|

Condenser 2 |

||

|

HEX |

| Parameters | Values |

| Individuals number in the population | 32 |

| Number of generations | 64 |

| Maximum mutation rate | 0.25 |

| Minimum mutation rate | 0.0005 |

| Initial mutation rate | 0.25 |

| Crossover probability | 0.85 |

| Decision variable | Range |

| TTD (°C) | 8-15 |

| 0.50-0.90 | |

| (kPa) | 1500-3000 |

| (°C) | 120-180 |

| state | Temperature [°C] | Pressure [kPa] | Enthalpy [kJ/kg] | Entropy[kJ/kgK] | ||||

| Reference | Study | Reference | Study | Reference | Study | Reference | Study | |

| 1 | 145 | 145 | 1129.81 | 1130 | 531.84 | 531.8 | 1.943 | 1.943 |

| 2 | 98.9 | 98.71 | 177.79 | 177.2 | 494.03 | 494 | 1.954 | 1.954 |

| 3 | 47.50 | 47.48 | 177.79 | 177.3 | 443.38 | 443.4 | 1.808 | 1.808 |

| 4 | 30 | 30 | 177.79 | 177.4 | 239.10 | 239.1 | 1.135 | 1.135 |

| 5 | 30.40 | 30.4 | 1129.81 | 1130 | 239.90 | 239.9 | 1.136 | 1.136 |

| 6 | 69.54 | 67.13 | 1129.81 | 1130 | 290.94 | 290.5 | 1.303 | 1.293 |

| Wnet [kW] | 3810 | 3947 | ||||||

| Thermal efficiency | 0.1508 | 0.1536 | ||||||

| PRESSURE [kPa] | TEMPERATURE [K] | AMMONIA CONCENTRATION | |||||||

| N° | Present work | Reference | Relative error [%] | Present work | Reference | Relative error [%] | Present work | Reference | Relative error [%] |

| 1 | 4919 | 4919 | 0 | 433.2 | 433.15 | 0.012 | 0.6299 | 0.6299 | 0 |

| 2 | 4919 | 4919 | 0 | 433.2 | 433.15 | 0.012 | 0.9094 | 0.9094 | 0 |

| 3 | 4919 | 4919 | 0 | 433.2 | 433.15 | 0.012 | 0.4269 | 0.4269 | 0 |

| 4 | 4919 | 4919 | 0 | 319 | 319.07 | -0.002 | 0.4269 | 0.4269 | 0 |

| 5 | 823.2 | 823 | 0.024 | 319.8 | 319.81 | -0.003 | 0.4269 | 0.4269 | 0 |

| 6 | 823.2 | 823 | 0.024 | 352.3 | 356.54 | -1.189 | 0.9094 | 0.9094 | 0 |

| 7 | 823.2 | 823 | 0.024 | 342.2 | 342.16 | 0.012 | 0.6299 | 0.6299 | 0 |

| 8 | 823.2 | 823 | 0.024 | 312.1 | 312.1 | 0 | 0.6299 | 0.6299 | 0 |

| 9 | 4919 | 4919 | 0 | 313 | 313.06 | -0.019 | 0.6299 | 0.6299 | 0 |

| 10 | 4919 | 4919 | 0 | 378.7 | 378.69 | 0.003 | 0.6299 | 0.6299 | 0 |

| Present work | Reference | Relative error [%] | |||||||

| Thermal efficiency | 0.1353 | 0.1352 | 0.07396 | ||||||

| Parameters | Present work | Reference |

| Current density [A/m2] | 5000 | 5000 |

| Water primary temperature [°C] | 25 | 25 |

| Electrolyzer temperature [°C] | 80 | 80 |

| Net power [kW] | 29421 | 29421 |

| Hydrogen production [kg/s] | 0.0940 | 0.0940 |

| Working fluids | Wnet [kW] | [kg/s] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH3H2O - MD2M | 1470 | 0.03697 | 0.1184 | 0.1258 |

| NH3H2O - R236fa | 1469 | 0.03696 | 0.1332 | 0.1269 |

| NH3H2O - R152a | 1467 | 0.03689 | 0.1186 | 0.1261 |

| NH3H2O - ISOBUTANE | 1465 | 0.03685 | 0.1371 | 0.1258 |

| NH3H2O - ISOBUTENE | 1465 | 0.03684 | 0.1434 | 0.1253 |

| Outputs | Values |

|---|---|

| Net power, Wnet | 1470 [kW] |

| Hydrogen production, | 0.03697 [kg/s] |

| Energy efficiency, | 0.11184 |

| Exergy efficiency, | 0.1258 |

| PEME efficiency, | 0.2643 |

| System efficiency, | 0.213 |

| Working fluids | Wnet [kW] | [kg/s] | ||

| NH3H2O - MD2M | 1760 | 0.04415 | 0.1658 | 0.2477 |

| NH3H2O - R236fa | 1738 | 0.04361 | 0.1575 | 0.2558 |

| NH3H2O - R152a | 2016 | 0.05049 | 0.1502 | 0.252 |

| NH3H2O - ISOBUTANE | 1744 | 0.04377 | 0.1626 | 0.2583 |

| NH3H2O - ISOBUTENE | 1734 | 0.04353 | 0.1713 | 0.2522 |

| Terms | Base | Optimum |

| Temperature source [°C] | 180 | 180 |

| Terminal temperature difference [°C] | 10 | 8.039 |

| High pression [kPa] | 2500 | 2981 |

| Ammonia concentration (X_basic) | 0.65 | 0.8997 |

| Net power, Wnet [kW] | 1868 | 2016 |

| Hydrogen production, [kg/s] | 0.04683 | 0.05049 |

| Energy efficiency, | 0.1234 | 0.1502 |

| Exergy efficiency, | 0.2007 | 0.250 |

| System efficiency, | 0.215 | 0.2272 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).