1. Introduction

The contamination of natural waters and soil with heavy metals from industrial effluents represents a significant environmental concern in the present era. The battery industry represents a significant source of heavy metal contamination, with industrial wastewater from battery manufacturing and recycling companies containing considerable quantities of heavy metals. The cathode of Li-batteries produced for the automotive industry (e.g. NMC, NCA, LMO cells) contains nickel, manganese and cobalt metals in varying proportions [

1]. At higher concentrations, heavy metal pollution is dangerous because of its direct toxic effects on living organisms; however, at low concentrations it also poses a serious risk due to its accumulation in the food chain [

2]. Several technologies have been developed to remove heavy metals from industrial wastewater, including ion exchange, reverse osmosis, electrodialysis and ultrafiltration [

3]. However, in addition to their efficiency, these processes often present several disadvantages, including incomplete metal removal, sludge formation, high reagent and energy requirements, metal precipitate aggregation, and fouling of membrane filters. In consequence, alternative technologies have emerged as a significant area of research in recent years. Among these, bioremediation processes have attracted particular attention as a treatment technology for the removal of heavy metals [

4]. This interest stems from technology’s perceived economic feasibility, efficiency, and environmental compatibility [

5].

Bioremediation processes encompass technologies that utilise biological systems to diminish the concentration and detrimental effects of pollutants to an acceptable level. The main organisms used in bioremediation technologies are microorganisms, including bacteria, algae and yeasts [

6]. These can adsorb toxic metal ions on their cell surfaces, accumulating them in large amounts in the intracellular space [

7].

Chlorella vulgaris, a freshwater microalga, has been identified as a particularly efficacious agent in this regard [

8]. The cell wall of Chlorella vulgaris is composed of complex carbohydrates, with a network of cellulose fibres attached to a variety of polysaccharides, including hemicellulose and glycoproteins [

9]. Furthermore, monosaccharides (e.g. glucose, mannose, galactose, xylose, fucose, arabinose), lipids and considerable quantities of glucosamines are present. The functional groups present in these polymer molecules are significant regarding the processes of adsorption. The cell wall biopolymer was found to contain several functional groups, including carboxyl (-COOH), hydroxyl (-OH), amino (-NH

2), carbonyl (-C=O), ester (-CO-O), sulfhydryl (-SH), sulfate (-SO₄²-) and phosphate (PO₄³-). The functional groups are protonated in accordance with the pH level, thereby influencing the charge of the cell wall [

10]. It can be observed that above pH 3, the negative charge of carboxyl groups, phosphate groups and hydroxyl groups is predominant, with positively charged heavy metal cations adsorbing to the negatively charged cell wall [

11]. The adsorption of cell surface biopolymers can occur by several mechanisms, including physisorption, ion exchange, chelation and complexation [

12].

In addition to the removal of heavy metal ions from industrial wastewater, the issue of how to remove algae that accumulates heavy metal ions from wastewater must be addressed. Several conventional methods have been developed for the removal of algae from wastewater. The most used methods are sedimentation, flotation, coagulation and flocculation, filtration, and sedimentation [

13]. Magnetic separation is an innovative technology that is characterised by rapidity, cost-effectiveness and energy efficiency. Algal cells exhibit a high affinity for the adsorption of magnetisable nanoparticles (MNPs) onto the surface of their cell walls, thereby enabling their isolation from wastewater in a magnetic field of sufficient strength [

14,

15]. The conventional sedimentation method took more than 2 hours for the coagulation and settling of algae, whereas the magnetic separation technique achieved the same outcome in just 30 seconds [

16]. Both naked and surface-functionalized (using polyacrylamides, chitosan, poly diallyldimethylammonium chloride (PDDA), aminoclay, polyethylenimine (PEI), 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane (APTES)) magnetic nanoparticles have been applied for the harvesting of

C. vulgaris [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Specifically, amine-functionalized MgFe₂O₄ nanoparticles exhibit high efficiency in binding to cell walls rich in negatively charged carboxyl groups [

24]. Furthermore, magnetic biomass can be rapidly and efficiently separated by applying an external magnetic field, facilitating streamlined recovery and reuse.

The purpose of this study is to examine the capacity of Chlorella vulgaris cells to adsorb cobalt ions, which are heavy metal ions that may be present in effluents from battery manufacturing processes. This study further investigates the capacity of cobalt-adsorbed algal cells to take up amine-functionalized MgFe₂O₄ nanoparticles onto their cell walls and to facilitate sedimentation within a magnetic field. This approach could enable the development of an innovative and environmentally friendly method for the removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewater in a more cost-effective manner, thereby complementing conventional wastewater treatment technologies. The interactions between microalgal cells and magnetic nanoparticles were analysed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), with particular attention to identifying the functional groups involved by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements. The particle size and morphology of the magnetic nanoparticles were characterized by HRTEM. Additionally, zeta potential measurements were conducted to examine the separation mechanism of C. vulgaris microalgae facilitated by synthesized iron oxide magnetic particles.

3. Discussion

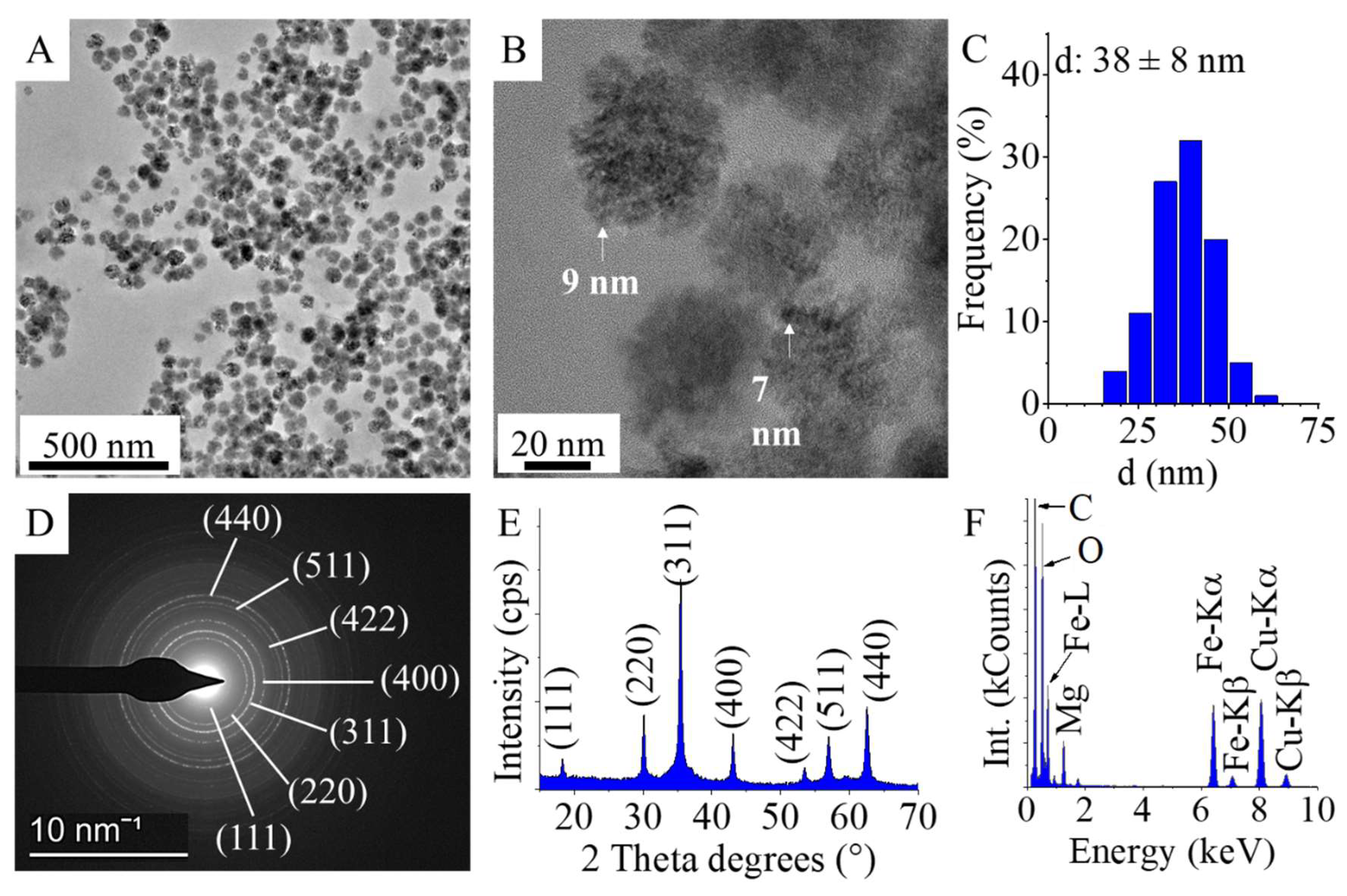

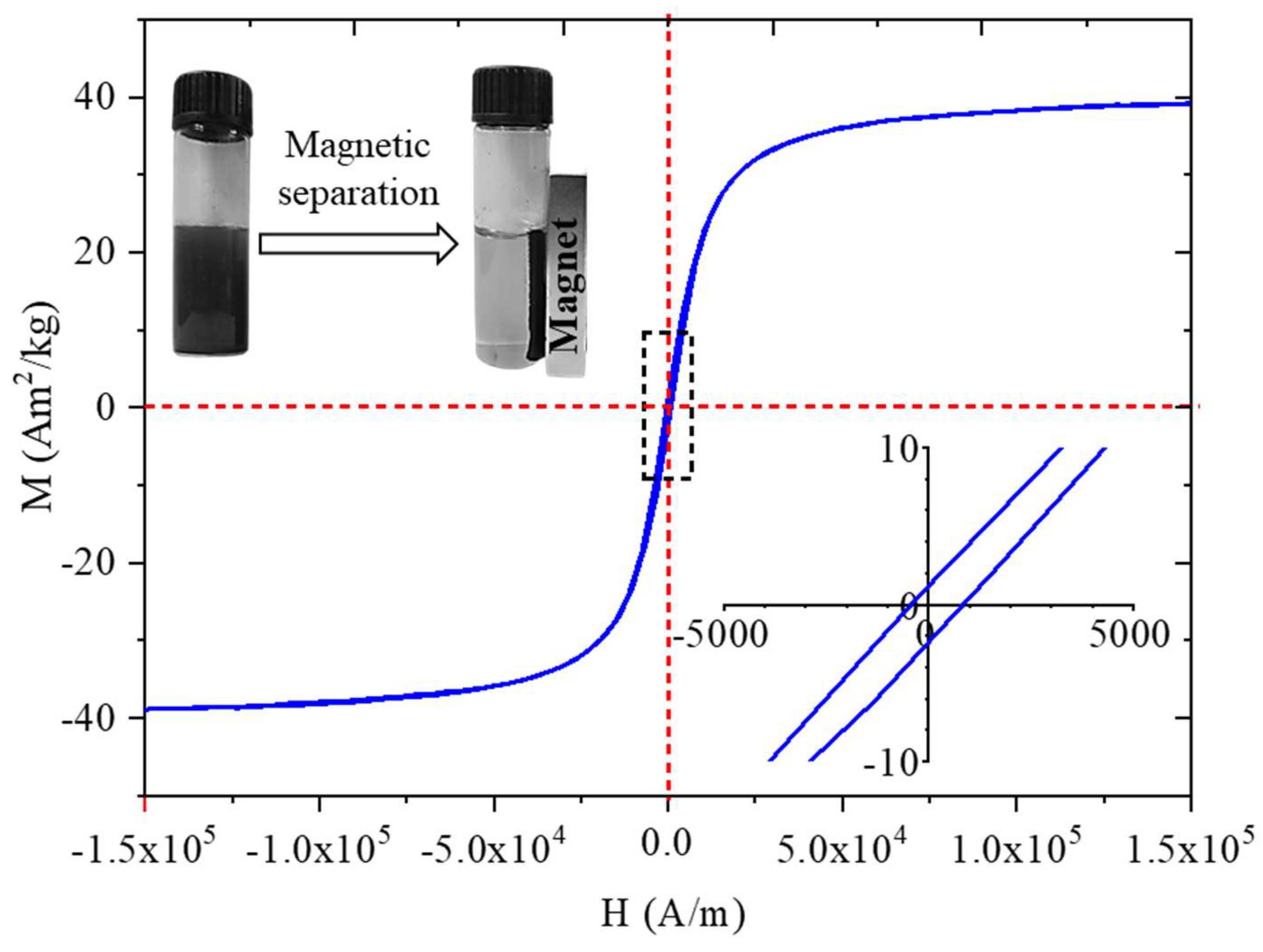

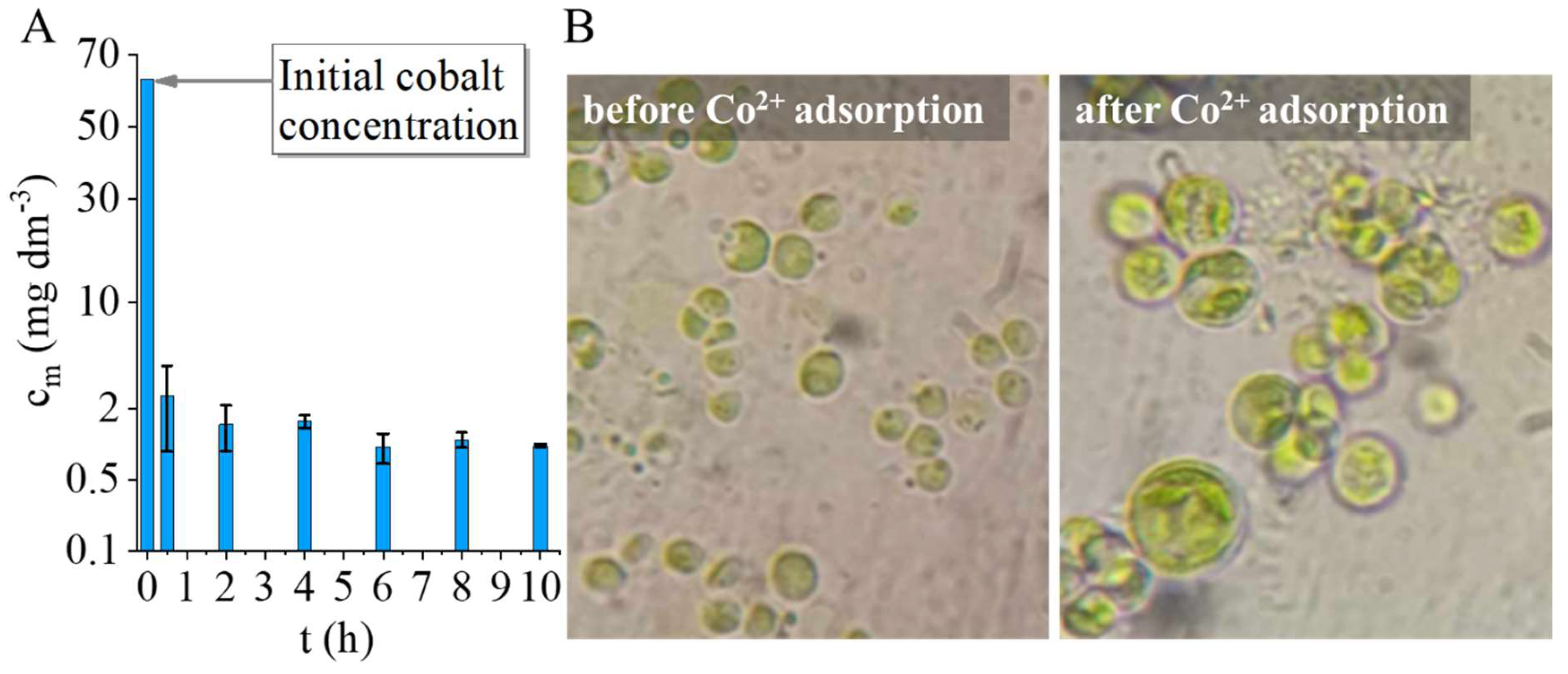

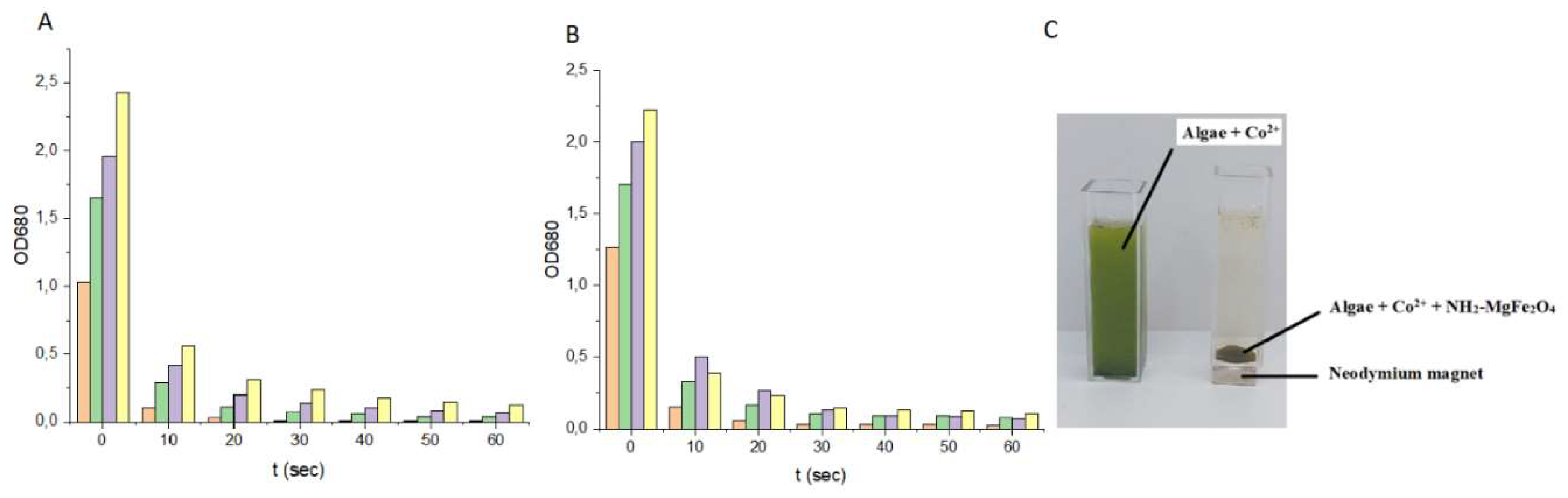

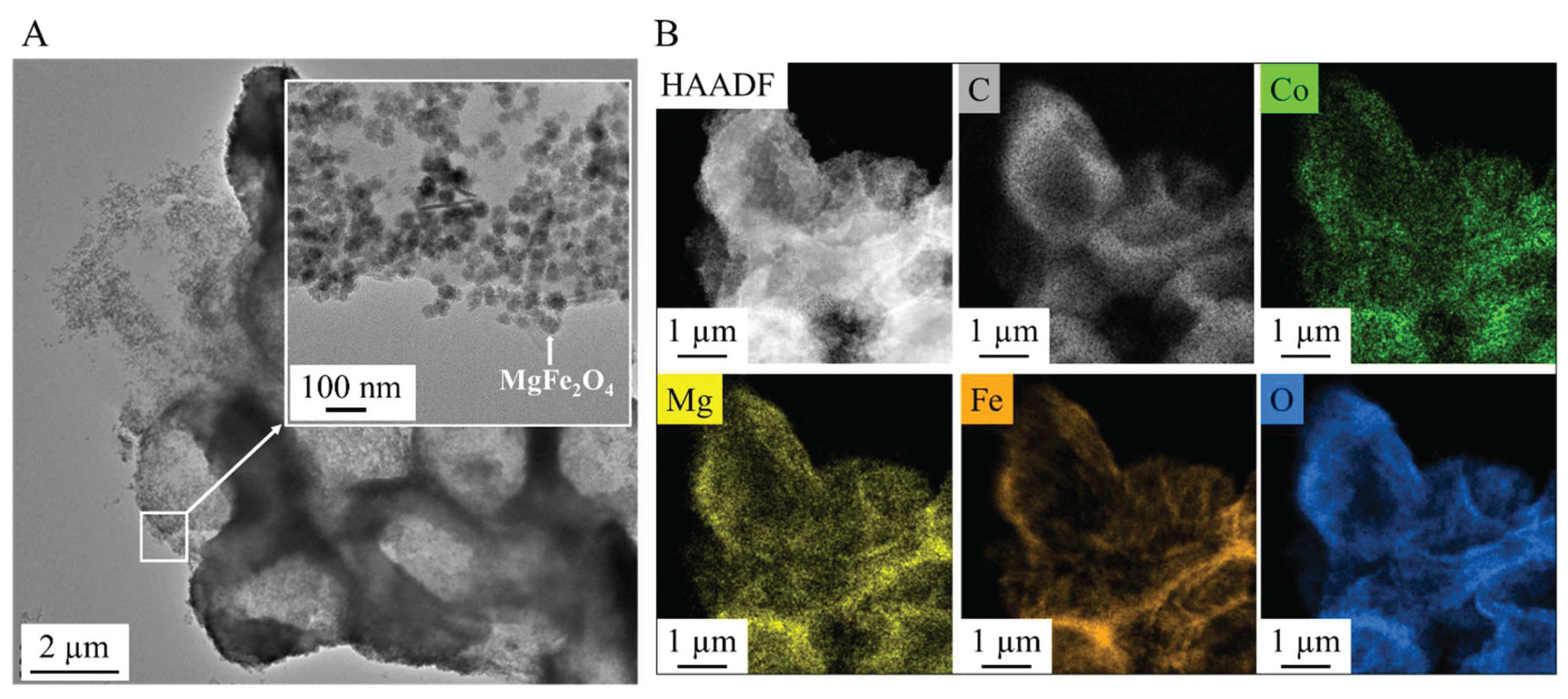

The study demonstrates the successful synthesis and characterization of amine-functionalized magnesium ferrite (MgFe₂O₄) nanoparticles, which consist of aggregated spheres made up of 7–10 nm particles. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) confirmed the presence of -NH₂ and -OH functional groups, crucial for surface reactivity. Zeta potential measurements at neutral pH revealed a slightly negative charge (-5.6 ± 4.3 mV), indicating the partial deprotonation of surface hydroxyl groups. However, at lower pH levels, protonation of the -NH₂ groups leads to positive surface charges, facilitating electrostatic interactions with negatively charged algae. The nanoparticles exhibited strong magnetic properties, with a saturation magnetization (Ms) of 39 Am²/kg at 150 000 A/m, confirmed by vibrating sample magnetization (VSM). This property was key to the efficient separation of algae, which bound to the nanoparticles through electrostatic interactions. The algae exhibited high cobalt adsorption efficiency, reducing the Co²⁺ concentration from 63.6 mg/L to 2.49 mg/L within 30 min, achieving a removal efficiency of 96.44%, which further increased to 98.78% after 10 h. When exposed to a magnetic field, the algal biomass attached to the MgFe₂O₄ magnetic nanoparticles was separated from the nutrient solution with an efficiency of 94.9-99.2% within 60 seconds. The separation rate was comparable for both cobalt-adsorbed and unmodified algal biomass, with no significant difference between the two. TEM analysis confirmed the even distribution of nanoparticles on the algal surfaces after magnetic separation.

These results highlight the potential of low-cost, biocompatible, and widely available magnetic nanoparticles in wastewater treatment, particularly for the removal of heavy metals, offering a promising approach for sustainable environmental remediation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The amine-functionalized magnesium ferrite nanoparticles were synthesized from magnesium nitrate hexahydrate, Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, MW: 290.79 g/mol (ThermoFisher GmbH, D-76870 Kandel, Germany) and iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate, Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, MW: 404.00 g/mol (VWR Int. LtD., B-3001 Leuven, Belgium). Ethylene glycol, HOCH2CH2OH, (VWR Int. Ltd., F-94126 Fontenay-sous-Bois, France) was used as dispersion media. For coprecipitation and the functionalization of the ferrites, monoethanolamine, NH2CH2OH (Merck KGaA, D-64271 Darmstadt, Germany) and sodium acetate, CH3COONa (ThermoFisher GmbH, D-76870 Kandel, Germany) were used.

4.2. Synthesis of the amine functionalized magnesium ferrite nanoparticles

Synthesis of the magnetic particles was carried based on the method of Nonkumwong et al. [

25]. Sodium acetate (15 mmol) was dissolved in ethylene glycol (10 ml) and heated to 100 °C during continuous stirring. Magnesium(II)-nitrate (1 mmol) and iron(III)-nitrate (2 mmol) precursors were solved in 50 mL ethylene glycol, after complete dissolution, the two solutions were combined. The mixture was stirred for 30 minutes, then ethanolamine (4 mL) was added. The solution was heated to 200 °C and refluxed for 12 hours with continuous stirring. The dispersion was cooled down to room temperature, then it was separated by magnetic field use of Nd magnet. The solid phase was washed with distilled water several times. Finally, the ferrite was dried 85 °C overnight.

4.3. Cobalt adsorption tests

The Chlorella vulgaris strain was obtained from the Advanced Materials and Intelligent Technologies Higher Education and Industrial Cooperation Centre at the University of Miskolc.

C. vulgaris strain was maintained in modified “endo” medium [

26] containing KNO

3 3g/l, KH

2PO

4 1.2g/l, MgSO

4·7H

2O 1.2gl/l, citric acid 0.2 g/l, FeSO

4·7H

2O 0.016 g/l, CaCl

2·2H

2O 0.105g/l, trace element stock solution 1ml/l. For trace elements a stock solution has been prepared containing Na

2EDTA 2.1g/l, H

3BO

3 2.86g/l, ZnSO

4·7H

2O 0.222 g/l, MnCl

2·4H

2O 1.81 g/l, Na

2MoO

4·2H

2O 0.021g/l, and CuSO

4·5H

2O 0.07g/l. After solution of all components of the medium the pH was adjusted to 6.5±0,2 and the temperature was controlled at 24 °C.

For growing of C. vulgaris a glass tubular air lift photo-bioreactor system was constructed, which consisted of Hailea V20 membrane compressor with a capacity of 20 l/min air flow with electric power 15W. The reactor system contained 9 pieces of glass vessel with a volume of 500 ml. The air flow rate was 4,5 l/min in each reactor vessel. Reactors were illuminated with. LED lamps with a light intensity of 3000 lumen. The reactors were inoculated with 4.2 mg/l concentrated Chlorella v. culture at a 1% inoculation rate. The initial biomass concentration at inoculation was 0.9 mg/l (= 0.5±0.1 OD680) in the reactor vessels. Cell growth was followed by measuring of OD680 values by UV-6300PC Doublebeam Spectrophotometer of the samples by 24 hours.

A cobalt solution (Certipur, Merck Ltd.) with a concentration of 60 mg/l is added to the bioreactors at the 24. hour of cultivation. 3 ml samples were taken from the cultures after 30 min of cobalt addition and after 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 hours. A solution of cobalt at a concentration of 60 mg/L was selected as it represents the toxicity limit for Chlorella vulgaris [

27].

For Co2+ analysis cell free supernatant was prepared by centrifugation of cultures in Eppendorf tubes with 9000 g; 10 min. 1ml supernatants were transferred to 15 ml Falcon tubes and were diluted to 10 ml with ultrapure water.

4.4. Magnetic separation tests of the cobalt adsorbed algae

In the experiments, the time and efficiency of magnetic separation were compared between cobalt adsorbed algal biomass and normal algal biomass under different algal concentrations. Concentrated Chlorella v. culture containing 4,2 mg/l dry biomass was diluted. Different concentrations of algal suspension were used: 3,6 mg/l (= 2,0±0,1 OD680), 2,7 mg/l (= 1,5±0,1 OD680), 1,8 mg/l (= 1,0±0,1 OD680), 0,9 mg/l (= 0,5±0,1 OD680), while the concentration of NH2-Fe2O4 solution was fixed at 0.511 g/l. 100 cm3 algal suspension of different concentrations was mixed with 0,511 g/l of amine-functionalized MgFe₂O₄ nanoparticles for 10 min using the air bubbling compressor by Hailea V20 membrane compressor with a capacity of 20 l/min air flow with electric power 15W. An additional 100 cm³ algal suspension of different concentrations a cobalt solution of 60 mg/l was added, and it was mixed with air bubbling for 30 min. Subsequently, the algal biomass was treated with amine-functionalized MgFe₂O₄ nanoparticles at a concentration of 0.511 g/l for 10 min using the air bubbling compressor. The pH was adjusted to 6,5 with phosphate buffer and the temperature was 24 °C.

4.5. Characterization Technics

For morphological characterisation and size analysis of the magnetic nanoparticles were carried by use High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, Talos F200X G2 electron microscope with field emission electron gun, X-FEG, accelerating voltage: 20-200 kV, ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For the imaging and selected area electron diffraction (SAED), SmartCam digital search camera (Ceta 16 Mpixel, 4k x 4k CMOS camera, Thermo Scientific, Wal-tham, MA, USA) was used with a high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detector. During sample preparation, the aqueous dispersion of the nanoparticles was dropped onto copper grids (Ted Pella Inc., 4595 Redding, CA 96003, USA). For phase analysis of the magnetic nanoparticles, X-ray diffraction (XRD) method and Rietveld refinement were applied. For X-ray diffraction measurements Bruker D8 diffractometer (Cu-Kα source) in parallel beam geometry (Göbel mirror) with Vantec detector was used. The functional groups on the surface of the amine-functionalized magnesium ferrite were examined with Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), using a Bruker Vertex 70 spectroscope. The measurements were carried out in transmission mode, whereas the sample preparation was carried with palletisation in spectroscopic potassium bromide (10 mg ferrite sample was measured to 200 mg KBr). The zeta potential of the nanoparticles was measured based on electrophoretic mobility by applying laser Doppler electrophoresis with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS equipment (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). The specific surface area (SSA) of the samples was measured by carbon dioxide adsorption-desorption experiments at 273 K based on Dubinin-Astakhov (DA) method (with Micromeritics ASAP 2020 equipment). To measure the saturation magnetization (Ms), remained magnetization (Mr) and the coercivity (Hc) of the samples was carried out with vibrating-sample magnetometer (VSM) system based on a water-cooled Weiss-type electromagnet (self-developed magnetometer by University of Debrecen). For the VSM test the sample was pelletized with mass of 20 mg. The magnetization (M) was measured as a function of magnetic field (H) up to 150,000 A/m field strength at room temperature.

The concentration of cobalt ions in the supernatant was determined by Inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES). The ICP instrument was the Varian-make 720 ES type simultaneous, multielement spectrometer with axial plasma view. The parameters of the analyses were the following: Running frequency of the RF generator 40[MHz]; Sample introduction device: V-groove nebulizer with sturman-masters spray chamber; sample uptake 2.1 cm3/min. Length of signal integration: 8s; number of reading: 3/sample. The calibration of the instrument was performed by using a solution series prepared from a 1000 mg/dm3 monoelement stock cobalt solution (Certipur, Merck Ltd.)

Co

2+ removal efficiency was calculated by the following equation:

[Co2+]t0 = initial concentration of Co2+ given in mg/L,

[Co2+ ]t1 = Co2+ concentration of the given time point after cobalt addition of the cell free supernatant.

To determine the efficiency of nanoparticles to bind to the surface of cobalt adsorbed algal cells and normal algal cells, we measured their sedimentation rate in a magnetic field. 4 ml of the algal suspension was measured into a special cuvette with a 10×10×3 mm, N45 neodymium magnet glued to the bottom. The cuvette with the magnet was placed in the spectrophotometer cuvette holder and the sedimentation rate was measured by the change in optical density over time. The change in optical density was followed by measuring at 680 nm by UV1100/UV-1200 Doublebeam spectrophotometer (Frederiksen).

The harvesting efficiency (HE%) of the process was calculated from Equation:

OD0 = initial absorbance of the microalgae cultivation at a wavelength of 680 nm,

OD1 = absorbance at the same wavelength of the supernatant liquid that separates from the microalgae-particles flocs after the application of the magnetic field.