1. Introduction

The escalating frequency of cyber incidents—including malware attacks, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and financial fraud—has underscored the critical need for robust cybersecurity measures among individuals, organizations, and stakeholders tasked with combating cybercrime. Compounding this challenge is the increasing sophistication of cyber threats, driven in part by advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) [

11,

12].

Cybercrimes transcend national borders, necessitating transnational professional collaboration to enable timely incident response and mitigation. Effective coordination is essential, both among international stakeholders and within domestic frameworks. This study focuses on the interaction and cooperation between actors in cybersecurity, as the efficacy of incident investigation, threat awareness, and proactive defense hinges on the timely exchange of relevant data and threat intelligence [

6].

A persistent gap exists between cyber threat awareness and actionable intelligence, often leaving end-users vulnerable. Organizations and experts address this by developing platforms for sharing indicators of compromise (IoCs), publishing threat reports, and disseminating real-time feeds [

7,

13].

Many reports from international organizations and vendors on the situation in the field of cybersecurity note the importance of exchanging data and information on threats and incidents, as well as on actors, methods and tools used, in order to respond to threats in a timely manner and ensure the security of critical objects and data. This circumstance requires wider interaction and cooperation from all participants. Many experts agree that information exchange is often a key factor in ensuring effective cybersecurity, however, in their opinion, there is a need to adhere to a consistent approach in its implementation [

14,

15].

At the same time, a consistent approach to the exchange of data on cyber threats means maintaining the structure of data, ensuring the reliability of data and its applicability, in particular, this means the use of standardized formats and taxonomy, trusted data exchange mechanisms, full and relative data, data categorization mechanisms during their transmission, as well as ensuring the timeliness and compliance with the requirements of regulatory acts in the field of personal data protection and cybersecurity [

16,

17,

18].

Building on this, our research evaluates MISP as a free, open-source platform for threat data sharing and awareness-raising, addressing a critical gap in collaborative cybersecurity efforts.

2. Cybersecurity Challenges in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan faces cybersecurity challenges comparable to those observed globally, including insufficient public awareness of cyber threats, limited access to timely threat intelligence, and inadequate protective measures against malware attacks. Although the country has established a regulatory framework for cybersecurity—notably the Cyber Security Coordination Centre under the Specialized Government Agency critical gaps persist. Existing monitoring and analysis platforms are restricted to specialized government agencies, leaving the private sector and civil institutions vulnerable to escalating cyber incidents due to the absence of a unified threat-sharing mechanism [

5,

19].

To address this systemic gap, this study advocates for the adoption of the Malware Information Sharing Platform (MISP) as a scalable solution for threat data collection, analysis, and predictive modeling. MISP’s open-source architecture, global prevalence, and extensive documentation [

14] make it a pragmatic choice for Kyrgyzstan’s context, where resource constraints and technical capacity are key considerations.

While a comparative analysis of alternative platforms (e.g., ThreatConnect, OpenCTI) would yield valuable insights, such an evaluation falls outside the scope of this paper and is reserved for future research.

3. The Malware Information Sharing Platform (MISP): An Overview

The Malware Information Sharing Platform (MISP) is an open-source threat intelligence platform designed to facilitate the structured exchange of cybersecurity threat data, including Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), malware attributes, and financial fraud patterns, among trusted communities. By enabling collaborative sharing across closed, semi-private, or open networks, MISP enhances the timely detection of targeted attacks and improves overall threat response efficacy [

20].

The platform provides sharing, storing and correlating Indicators of Compromise of targeted attacks but also threat intelligence such as threat actor information, financial fraud information and many more.

Key Features of MISP:

• 1. Distributed Sharing Model: Supports technical (e.g., IoCs, hashes) and non-technical (e.g., threat actor profiles) intelligence sharing.

• 2. Automation and Integration:

◦ REST API for programmatic data exchange.

◦ Extensibility via misp-modules and libraries like PyMISP for custom integrations.

• 3. Community-Driven: Adaptable to diverse use cases, from national CERTs to sector-specific ISACs (Information Sharing and Analysis Centers).

4. Literature Review

The increasing sophistication of cyber threats has prompted significant research into threat intelligence sharing platforms enhanced with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) capabilities. This section provides a comprehensive examination of recent scholarly work in this domain, focusing on technical implementations, regional applications, and framework developments.

Mark Schmitt’s [

2] seminal work provides a thorough investigation into the application of AI/ML methods for protecting modern IT and cybersecurity ecosystems. His research highlights how the rapid proliferation of information technologies, artificial intelligence systems, and IoT devices has correspondingly led to the emergence of increasingly complex and sophisticated threats. Schmitt presents a compelling argument for the integration of AI capabilities into core security systems, particularly Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), where pattern recognition and anomaly detection can be significantly enhanced through machine learning algorithms. Notably, Schmitt identifies a critical gap in current cybersecurity tool development, observing that the majority of commercial solutions are primarily designed for enterprise environments, leaving individual users and small organizations particularly vulnerable. This market orientation, he argues, creates a significant protection disparity where non-commercial users lack access to adequate security measures despite facing comparable threat levels.

Ibrahim Yahya Alzahrani’s [

1] research presents an innovative model for Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) implementation using the Malware Information Sharing Platform (MISP). His methodological approach combines both active and passive data collection techniques:

• 1. Active Collection: Deployment of honeypot systems configured to mimic vulnerable services, thereby attracting and capturing real-world attack data. This method provides invaluable insights into emerging attack vectors and tactics.

• 2. Passive Collection: Aggregation of Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) from vendor threat reports, whitepapers, and security bulletins, offering comprehensive historical threat data. Following data collection, Alzahrani applies sophisticated machine learning analysis to the aggregated dataset, demonstrating significant improvements in predictive capabilities regarding potential cyber attacks. His work particularly emphasizes how MISP’s flexible architecture facilitates this integrated approach to threat intelligence.

The Arab region exemplifies these challenges, facing a dual dilemma: a scarcity of localized IT initiatives forces reliance on costly external solutions, while simultaneously becoming a high-value target for ransomware groups. Alzahrani’s proposal to adopt MISP for IoC integration and data collection offers a viable pathway to improve threat prediction accuracy.

Mostafa Ahsan [

3] provides a comprehensive taxonomy of cybersecurity concepts in his foundational work. His research offers detailed explanations of key terms, strategies, and frameworks while conducting a comparative analysis of traditional versus next-generation Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS). Ahsan traces the evolution of malware types and attack methodologies, providing crucial context for contemporary threat landscapes.

A significant portion of Ahsan’s work focuses on the critical role of standardized datasets in cybersecurity research, including:

• NSL-KDD (enhanced version of KDD Cup 99 dataset)

• IMPACT (funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security)

• DARPA intrusion detection datasets

• UNSW-NB15 (developed at the University of New South Wales)

Ahsan meticulously documents the machine learning pipeline for cybersecurity applications, from data preprocessing to model deployment, demonstrating how various algorithms (including decision trees, random forests, and neural networks) contribute to data-driven security decision making.

Zimin [

4] provides valuable insights into cybersecurity developments across Central Asia, with particular attention to Kyrgyzstan’s evolving security posture. His research documents how each Central Asian nation is developing distinct national cybersecurity policies and strategies. Regarding Kyrgyzstan specifically, Zimin details ongoing efforts to establish:

• A national Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT)

• A specialized Committee for Information Security

• Comprehensive cybersecurity legislation

These institutional developments aim to create a coordinated national authority for cybersecurity matters, addressing what Zimin identifies as critical infrastructure protection gaps in the region.

The work of Isakhin and Karunas [

22] offers practical insights into Security Operations Center (SOC) implementations, with particular focus on the integration of:

• MISP (for threat intelligence sharing)

• ELK Stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana for log analysis)

• SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) systems

Their research demonstrates how these complementary systems create a robust framework for comprehensive threat detection, analysis, and response.

Henttonen and Rajam¨aki’s [

8]comprehensive study of Finland’s cybersecurity infrastructure provides a valuable case study in national-level Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) implementation. Their research includes:

• Detailed examination of CTI’s role in critical infrastructure protection

• Analysis of stakeholder engagement through extensive interviews

• Evaluation of information sharing mechanisms

• Measurement of operational outcomes

The Finnish model presented in their work offers important lessons for developing cybersecurity frameworks in other national contexts, particularly regarding public-private collaboration and cross-sector information sharing. This comprehensive review of existing literature establishes the theoretical and practical foundation for examining MISP implementation in Kyrgyzstan’s cybersecurity ecosystem, while identifying critical gaps in current threat intelligence sharing approaches that this research aims to address.

5. Methodology

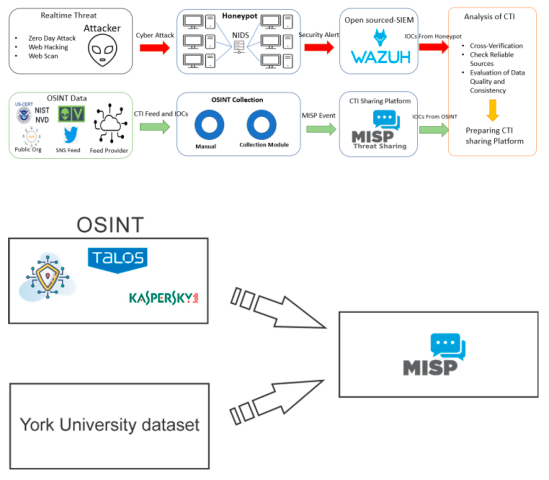

It is worth noting in advance that the model developed by specialists from the Naif Arab University was taken as a basis. The main goal of their research was to achieve effective and accurate prediction results when analyzing a dataset of network anomalies and reports on cyber threats. According to their model, the dataset was collected in two ways: 1 - through ”honeypots” physically located in different cities of the Middle East and North Africa and 2 - manual collection of reporting information from vendors and international organizations engaged in countering cyber threats (CISA, MITRE, ENISA, etc.). Then, they applied deep learning methods to the collected data to obtain prediction results in accordance with the task (3).

In our case, due to the lack of ”honeypots”, data sets were collected manually from reports of vendors and international organizations, and ready-made data sets on network anomalies and attacks, which we received from the York University, were also used (3).

A. Research Framework

We would like to remind you that the purpose of our small research was to study and confirm the possibility of automating the process of entering data on cyber incidents and cyber threats into the MISP platform.

The MISP platform provides organizations with critical capabilities for analyzing collected cybersecurity data and disseminating actionable intelligence to security tools. However, during threat intelligence operations, security teams encounter significant challenges in processing redundant Indicators of Compromise (IoCs), which may degrade analysis quality and delay protective measures deployment.

B. Technical Implementation

Our research methodology incorporates the following components: 1. Platform Deployment: ◦ Deployed test MISP instance using Docker containerization ◦ Configured API access and automation scripts 2. Data Collection Approach: ◦ Utilized the BCCC-CIC-IDS2017 dataset from York University ◦ CSV conversion with Python scripting ◦ JSON transformation for REST API transmission 3. Automation Pipeline

Our instance of MISP was installed on the Docker platform according to the instructions provided on the developer’s website. Then, data was entered into MISP manually from the organizations’ reports. To automatically enter the ready-made data set on network anomalies and threats received from the York University, it was first necessary to convert the data set from csv to json using the script:

import csv

import json

csv_file = "/home/cs/Documents/botnet_ares.csv"

json_file = "/home/cs/Documents/botnet_ares.

json"

data = []

with open(csv_file, mode="r") as file:

reader = csv.DictReader(file)

for row in reader:

data.append(row)

with open(json_file, mode="w") as file:

json.dump(data, file, indent=4)

print(f"CSV file ’{csv_file}’ has been

converted to JSON file ’{json_file}’.")

Next, the following script was used to transfer data to our MISP instance:

import pandas as pd

import requests

csv_file = "/home/cs/Documents/botnet_ares.csv

"

df = pd.read_csv(csv_file)

misp_attributes = []

for index, row in df.iterrows():

flow_id_parts = row["flow_id"].split("_")

src_ip = flow_id_parts[0]

dst_ip = flow_id_parts[2]

misp_attributes.append({"type": "ip-src",

"value": src_ip})

misp_attributes.append({"type": "ip-dst",

"value": dst_ip})

misp_attributes.append({"type": "datetime"

, "value": row["timestamp"]})

misp_attributes.append({"type": "comment",

"value": row["label"]})

event_data = {

"Event": {

"info": "Firewall Dataset Import",

"Attribute": misp_attributes

}

}

misp_url = "https://localhost/events/index"

misp_key = "bXS******************************2

N1MYiW"

headers = {

"Authorization": misp_key,

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"Accept": "application/json"

}

response = requests.post(misp_url, headers=

headers, json=event_data, verify=False)

if response.status_code == 200:

print("Hey Boss, Data imported

successfully!")

#print("Event ID:", response.json()["Event

"]["id"])

response_data = response.json()

print("API Response:", response_data)

if isinstance(response_data, list):

event_id = response_data[0].get("id")

else:

event_id = response_data.get("id")

if event_id:

print("Event ID:", event_id)

else:

print("Event ID not found in the

response.")

else:

print("Oh My God, Failed to import data",

response.text)

After carrying out the above actions, the presence of automatically transferred ready data in our copy of the MISP was checked and confirmed as a conducted validation process.

C. Technical Limitations and Future Enhancements

In conducting our study, which in turn was based on the research model conducted by Naif Arab University, we had certain limitations.

Firstly, the data collection was done without using honeypots, secondly, the data obtained was not processed in a security information and information system (SIEM), thirdly, the data was not processed using Deep Learning methods to obtain predictions. Furthermore, our study did not go beyond one organization and did not cover the results of several countries, as was the case with the work of Naif Arab University.

Nevertheless, our research will be continued, since in our opinion and according to the observations of international organizations and experts in the field of cybersecurity, issues of awareness and prompt exchange of information on cyber threats can significantly affect the timely response to threats, the adoption of effective measures and, in general, the provision of cybersecurity of critical infrastructure. We also consider it necessary to conduct further our research using Deep Learning methods and tools in order to study the possibility of forecasting and predicting threats and intelligently responding to them.

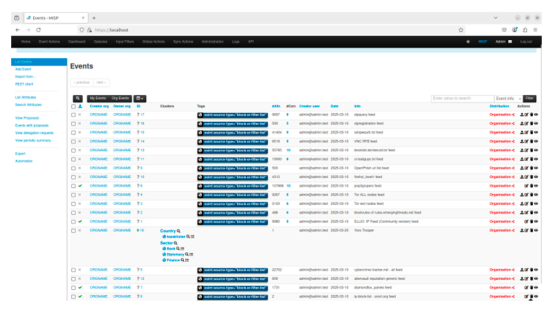

6. Results

In this study, a dataset comprising 3,880 entries related to network attacks was analyzed to evaluate the feasibility of automated data integration into a MISP (Malware Information Sharing Platform) instance. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed Python-based scripting approach successfully facilitates the automatic ingestion of structured threat data into the MISP platform. Upon submission of the dataset, the integrated events were promptly visible within the MISP instance, confirming the functional efficacy of the implemented solution.

However, while the proof-of-concept implementation validates the core automation mechanism, the process is not yet fully autonomous. Manual preprocessing of the input dataset remains necessary to ensure compatibility with MISP’s data schema. Specifically, additional steps such as data filtering, normalization, and compliance checks are required prior to ingestion. These preprocessing stages highlight a current limitation in achieving complete end-to-end automation. Future refinements could focus on incorporating preprocessing logic directly into the ingestion pipeline to further reduce manual intervention.

7. Conclusions

With this study, we tried to take the first step in studying the issue of improving and creating a basis for a mechanism for informing and exchanging information on cyber threats in Kyrgyzstan.

The reason for this is that, as we have previously reported in this paper, many local communities and national organizations do not have the ability to receive information about threats and respond to them in a timely manner, which is a significant problem. The same is said by researchers from the Arab University of Naif in relation to the countries of the Middle East and North Africa.

Considering that in cybercrime a person is the main factor of its successful implementation, awareness is one of the important aspects in ensuring cybersecurity. And in this case, we deliberately took as the basis of our study the open source data exchange platform MISP, as a tool used by everyone and known to everyone.

The use of the MISP platform is also an attempt to consider the possibility of ensuring security by implementing various free systems, given that many organizations, particularly budget ones, that store and process sensitive data, cannot afford to purchase expensive commercial systems and solutions.

Along with this, this research we are moving in small steps towards studying the issue of automating procedures for collecting, forming a relative database, analyzing them and gradually forecasting cyber threats.

This methodology demonstrates a practical approach to threat intelligence sharing while acknowledging current resource limitations. The modular design allows for incremental improvements as additional components become available.

References

- Ibrahim Yahya Alzahrani, Seokhee Lee, and Kyounggon Kim, “Enhancing Cyber-Threat Intelligence in the Arab World: Leveraging IoC and MISP Integration,” Electronics, June 2024.

- Marc Schmitt, “Securing the digital world: Protecting smart infrastructures and digital industries with artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled malware and intrusion detection,” Journal of Industrial Information Integration, vol. 36., 2023.

- Mostofa Ahsan, Kendall E. Nygard, Rahul Gomes, Md Minhaz Chowdhury, Nafiz Rifat and Jayden F Connolly, “Cybersecurity Threats and Their Mitigation Approaches Using Machine Learning—A Review,” Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, vol. 2, 2022.

- Zimin Igor, “Cybersecurity analysis of Kyrgyz Republic,” esa-conference.ru, 2019.

- Cholpon Jumalieva, “Improving the Digital Transformation in the Sphere of Public Administration and Ensuring Information Security,” Alatoo Academic Studies., vol. 23, 2023.

- Naeem AllahRakha, “Cross-Border E-Crimes: Jurisdiction and Due Process Challenges,” Adliya: Jurnal Hukum dan Kemanusiaan, vol. 18, September 2024.

- Kimberly, K. Watson, “Assessing the Potential Value of Cyber Threats Intelligence (CTI) Feeds,” December 2020.

- Katja Henttonen, Juri Rajamaki, “CTI Sharing Practices and MISP Adoption in Finland’s Critical Infrastructure Protection,” Proceedings of the 23rd European Conference on Cyberwarfare and Security., 2024.

- Ana, I. Cerezo, Javier Lopez, Ahmed Patel, “International Cooperation to Fight Transnational Cybercrime,” Annual Workshop on Digital Forensics and Incident Analysis, 2007.

- Fran Casino, Claudia Pina, Pablo Lopez-Aguilar, Edgar Batista, Agusti Solanas, Constantinos Patsakis, “SoK: cross-border criminal investigations and Digital Evidence,” Journal of Cybersecurity, 2022.

- https://www.axios.com/2025/03/24/microsoft-ai-agents-cybersecurity, “Microsoft AI Agents Cybersecurity,”, 2025.

- Financial Times, “Criminals use AI in ‘proxy’ attacks for hostile powers, warns Europol,” https://www.ft.com/content/755593c8-8614-4953-a4b2-09a0d2794684.

- CISA, “CISA Cybersecurity Awareness Program,” https://www.cisa.gov/resources-tools/programs/cisa-cybersecurity-awareness-program, 2025.

- CIRCL, “Computer Incident Response Center Luxemburg,” https://www.circl.lu, 2025.

- ENISA, “ENISA Cybersecurity Information Sharing,” https://enisa.europa.eu/activities/cert/support/information-sharing/cybersecurity-information-sharing/at download/fullReport,2025.

- Israel Government, “Israel Cyber Doctrine,” https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/cyber security methodology 2/he/ICDM%20V2.pdf, 2025.

- CISA, “CISA TLP RULES,” https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/traffic-light-protocol-tlp-definitions-and-usage.

- NIST, “NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0,” https://www.nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.29.pdf.

- Ministry of Justice of Kyrgyz Republic, “Kyrgyz Republic Cybersecurity Strategy,” https://cbd.minjust.gov.kg/15479/edition/962966/ru.

- CIRCL, “CIRCL MISP Guide,” https://www.circl.lu/doc/misp/book.pdf.

- York University, “Cybersecurity Database,” https://www.yorku.ca/research/bccc/ucs-technical/cybersecurity-datasets-cds/.

- Isakhin Georgii, Karunas Anna, “Threat intelligence and Security Operation Centers on ELK Stack,” Modern Science, XXI International Scientific Conference, http://naukaip.ru.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).