1. Introduction

Racism remains a widespread problem in the realm of sports on a global scale (Azzarito & Harrison, 2008; Hylton, 2009; Massao & Fasting, 2010). Researchers have explored various definitions of racism (Bulhan, 2004; Jones, 1997), reflecting the discomfort surrounding the discourse on this topic. However, many definitions tend to align around a common theme: the humiliating treatment of people based on their racial or ethnic group affiliations (Keum & Miller, 2018). Racism can be defined as a system that includes actions or behaviors (discrimination), attitudes (prejudice), and beliefs (stereotypes) that view some ethnic or racial groups as superior to others. The psychological, physical, and social consequences of racism on people of color are well documented (Pascoe & Richman, 2009). The persistence of racism, whether direct or indirect, manifests as mistreatment, unfair burdens, discrimination, and barriers faced by racial and ethnic minority groups. Recent happenings in Europe have significantly affected the reputation of sports, with racism standing out as a particularly prominent aspect of different types of violence. (Neves et al., 2023).

Research on race, ethnicity, and indigeneity both in the context of sports and society more broadly is not a new phenomenon. The recognition of the significance of Black lives highlights the systemic racism that affects opportunities and experiences across social strata, influencing attitudes and behaviors in diverse environments (Hylton, 2021). Currently, anti-racist activism has intensified, evident not only among athletes but also within international governing bodies, clubs, teams, and grassroots organizations. Historical experiences in the West demonstrate that sports have frequently been leveraged by athletes and spectators to promote political agendas, such as equal rights (Coombs & Cassilo, 2017; Dickerson, 2015). In light of increased attention to police injustices, protests, and social movements, Black athletes have taken a leading role in the fight against these issues. Throughout history, protests and social movements have played complex roles in combating injustice; however, contemporary athletes have established a novel stance in the battle against systemic oppression, a shift not seen in previous generations (Thomas & Wright, 2022). The rise of social media in recent years may be a crucial factor driving this focus on injustices and anti-racist movements.

Currently, over fifty percent of internet users worldwide participate in social networking platforms (Berkman, 2013), highlighting the changing social environment in the digital era—an environment where online interactions and resources play a crucial role in the everyday lives of most people (Bargh & McKenna, 2004; Wellman et al., 2001). Since the internet’s inception, racism has continuously evolved and found expression on various online social platforms (J. Daniels, 2012; Hughey & Daniels, 2013a). Due to the enduring popularity of online events, individuals can witness racist occurrences effortlessly and be exposed to them for prolonged durations. Given that online information is conveyed through text, images, and videos, racist content online can manifest in numerous multimedia formats. As a result, racist messages can be conveyed through various formats and articulated in inventive ways (Hughey & Daniels, 2013a; Steinfeldt et al., 2010). While research on online racism has gained traction recently, the phenomenon itself is not new. Back (2002) was the first to explore this topic by analyzing the characteristics of cyber racism, highlighting the ongoing spread of racist culture online, especially within white supremacist organizations. He pointed out that white nationalists effectively use the internet to rationalize a racist culture and advocate for racial superiority through various digital and online mediums, including text and multimedia formats. Online anonymity diminishes the norms and social constraints that typically govern face-to-face interactions (Suler, 2004), creating an environment where users feel emboldened to openly and repeatedly express their racist ideologies without accountability (Hardaker, 2010). The growth of engaging applications and websites can draw an increasing audience into this online space.

Over the past decade, the collection of qualitative data online has expanded significantly, enabling researchers to conduct studies more efficiently. Companies invest over one billion dollars annually in gathering qualitative data online (Esomar, 2018). Online focus groups provide participants the flexibility to engage at their chosen time and location, ensuring anonymity and lessening the fear of judgment (Daniels et al., 2019; Wilkerson et al., 2014). Beyond participant preferences, the imperative to collect data online becomes increasingly crucial in an uncertain future where health and safety concerns from potential pandemics may restrict face-to-face research (Parry, 2020). As individuals remain at home or are confined due to lockdown measures, there has been a significant surge in the use of video conferencing and text-based online communication (Kominers et al., 2020). For researchers looking to capitalize on the benefits of online focus groups, it is essential to understand how platforms that enable text-based communication can improve data collection (Richard et al., 2021).

Research on online racism has developed rapidly since the mid-2000s (Kearns et al., 2023). Kearns and colleagues (2023) indicate that prior to 2015, studies predominantly focused on sports within the UK and the US. However, post-2015, the focus broadened to include a more international perspective, encompassing countries such as Mexico, Russia, Canada, Brazil, Australia, Italy, Iran, and Poland. In this context, football has a long and troubled history characterized by various forms of violence, including hooliganism, racism, gender discrimination, and homophobia within stadiums (Dunning et al., 1984; King, 1997; Serrano-Durá et al., 2019). The production and dissolution of excitement and tension surrounding the game are increasingly evident in online spaces. These studies position sports as a vehicle for examining broader social media issues (Kavanagh et al., 2016) and scrutinizing the responses of sports organizations that take political stances (Cavalier & Newhall, 2018). Most research focuses on how football fans interact with the structures and contexts of social media that lead to distinctive behaviors. For instance, Milward (2008) notes that fan chants aimed at opposing players have developed in online spaces, highlighting how expressions of tension impact the values within particular fan groups and communities. In this context, Garcia and Proffitt (2022) explore how the inherent gender culture of US sports has fueled the rise of misogyny online. Similarly, Rodriguez (2017) examines how interactions between football fans and players, once limited to stadiums, have evolved into public experiences via social media. The media landscapes and the sports imagery they create on social media are as significant as the sporting events themselves. Sports-related discussions (Galtung, 1991) on social media—including posts, comments, and organized dialogues—both shape and are shaped by events and debates occurring in stadiums, thus quickly challenging traditional forms of sports discourse.

Despite the implementation of new policies and initiatives designed to combat racism, violence, xenophobia, and intolerance, challenges in addressing these issues persist (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2021), manifestations of hostile or discriminatory behavior in sports remain prevalent and widespread. Such behaviors often spill over into online spaces; almost anyone with internet access can view social media content showcasing controversial incidents and systemic issues related to racism. Moreover, the internet and social media have created alternative channels for communication, promoting unique social norms (Eschmann, 2020) that enable individuals to circumvent the more egalitarian standards often found in face-to-face interactions, thus making it easier to express racist viewpoints (Criss et al., 2021). This context underlines the necessity for academic research focused on online racism, particularly regarding sporting events that garner significant media and political attention. Current research indicates that the influence of specific social media platforms on the nature and dissemination of racist discourse in sports has not been thoroughly explored. As Galtung (1991) suggests, “we are likely dealing with one of the most powerful mechanisms of cultural transmission and structure known to humankind” in relation to sports. Instances of online hate in sports are becoming increasingly visible. Kavanagh et al. (2016) raise concerns about the link between online hate and major sporting events, noting that social interpretations of these events often include negative online interactions, such as insults and threats. Therefore, it is essential to consider the broader implications of racism and its potential for widespread impact through the internet. A key recommendation is the necessity for comprehensive primary data collection focused on sports and hate, along with the establishment of research infrastructures that involve a wider range of stakeholders and methodologies. This strategy can help address the challenges posed by the rapidly evolving nature of social media platforms. About a decade ago, online communication was largely dominated by instant messaging services like ICQ and chat rooms like mIRC, which have now been largely replaced by social networking sites (e.g., Facebook) and microblogging platforms (e.g., Twitter) (Keum & Miller, 2018). Consequently, when a social platform wanes in popularity, metrics for assessing racism associated with that medium risk becoming obsolete. For example, metrics focused solely on Twitter’s unique features lose relevance if the platform fails to engage users. Therefore, this study aims to encompass a broader range of content by analyzing various websites and applications. To gain a deeper understanding of how racist experiences develop in tandem with the rise of online social interactions, additional studies are necessary. This paper aims to highlight this phenomenon and facilitate future empirical research by offering a framework for conceptualizing racism in online sports events. This involves examining the factors that contribute to the emergence of online racism in sports and exploring strategies to address it. We define our focus on experiences of racism on the internet as “online racism” and seek to assess how sports-related discussions on social media are shaped by events occurring within stadiums, thereby challenging conventional forms of sports discourse. Upon conceptualizing these elements, we will propose theoretical and practical implications, along with numerous guidelines for future empirical research and preventive measures. Through these objectives, this research seeks to enhance our understanding of how online racism manifests in the realm of sports and the changing dynamics of fan interactions in the digital age.

Racism

Attention to race, racism, and racial differences has emerged at both the strategic and policy levels in higher education and sports (Winter et al., 2024). As academic disciplines, both fields have a longstanding tradition of critically examining racial marginalization. Recent studies on racial discrimination in sports have underscored the damaging impact of racist experiences on individuals, leading to increased distrust and deprivation (Sport England, 2024). Clark et al. (1999p. 805) Racism can be generally defined as “beliefs, attitudes, and actions that tend to demean individuals or groups based on their physical characteristics or affiliation with ethnic groups.” Harrell (2000) emphasized the centrality of power in his definition of racism, describing it as a system of domination, power, and privilege that relies on labeling racial groups. This system is rooted in the historical oppression of groups deemed inferior, deviant, or undesirable by members of the dominant group. This occurs in contexts where members of the dominant group sustain their social privilege by reinforcing structures, ideas, values, and behaviors designed to exclude members of subordinate groups from power, respect, status, or equal access to social resources. Prejudice, bigotry, hatred, and hostility are fundamental elements of racism, but whether they can be considered the only contexts of racism is debatable (Shelby, 2014). Other derogatory concepts that also reflect racist attitudes and behaviors include: Contempt, disrespect, derision, derogation, disregard, and demeanin (Blum, 2004). Historically and contemporarily, racism has been one of the predominant manifestations of injustice and inequality (Nixon, 2019).

Racism can manifest both directly and indirectly (Williams et al., 2019) and can be expressed in overt, explicit, or covert ways (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). Overt racism refers to forms that are easily identifiable as racist, contrasting with more insidious or covert forms, such as racial violence and slurs. Overt racism often manifests as ethnic nationalism and racial discrimination (Elias, 2015) and includes intentional, explicit harmful attitudes or behaviors toward individuals or minority groups based on characteristics like skin color. This type of racism can be perpetrated by individuals, groups, institutions, and societies (Vala et al., 2008). Covert or subtle racism, on the other hand, suggests that the opposing group does not conform to society’s traditional values (e.g., values related to work and success) and accentuates cultural differences between groups (Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995; Vala et al., 2008). Some researchers differentiate between race and ethnicity; ethnicity pertains to cultural traits such as language, clothing, norms, and values, while race generally refers to biological traits, including skin color and other physical markers (Van Sterkenburg et al., 2019). In everyday discourse, the terms race and ethnicity are often used interchangeably. Many individuals may perceive themselves as free from racist beliefs or attitudes, yet they might unconsciously express biases when certain triggers arise. For example, what may appear to be a common verbal insult can actually reflect overt racial bias (Ferreira et al., 2017).

Online Racism in Sports

Social media plays a dominant role in daily life, as people use these platforms to construct virtual identities, form friendships, seek job opportunities, play games, and consume the latest news. (Farrington et al., 2017). By expanding its features and services, social media provides a platform for individuals with racist views, remaining both a significant part of the solution and part of the problem (Kilvington et al., 2022). Pseudonyms, avatars, and anonymity on social media platforms conceal users’ identities (Kilvington et al., 2022). Suler (2004) suggests that anonymity allows users to separate their online actions from their personal lifestyles and identities, leading to a reduced sense of vulnerability regarding self-disclosure and behavior. The communicative differences between offline and online spaces encourage individuals to express their views more openly, reflecting the contemporary political and social climate. Kilvington (2021), referencing the work of Brown (2018) and Suler (2004), identifies four key factors contributing to online hate speech. First, anonymity or perceived anonymity allows users to circumvent the moral and psychological constraints that typically govern behavior in offline interactions. This anonymity gives individuals who engage in racist and abusive online behavior a sense of security, as they are more likely to escape punishment, which in turn exacerbates racism. Second, the invisibility of users enables them to ignore the realities of their hateful expressions. Physical, spatial, and geographical distance from victims can hinder true understanding of the impact of the hate expressed by aggressors, reducing the likelihood that perpetrators will feel empathy, which in turn supports hatred. Third, some platforms like Twitter encourage quick reactions.

When users have limited time to reflect on a post and its audience, they are more prone to sharing content they might later regret. Moreover, some online users treat the internet as a game, perceiving their actions and expressions as acceptable within that framework. Once they close their laptops or put away their smartphones, they return to a “real world” governed by established manners, rules, and norms. The internet has undeniably changed communication, interaction, and human behavior, making it a crucial area for academic inquiry. Hine (2012) argues that the internet is a significant social phenomenon of our era and presents an appealing field site for various social science research. Therefore, studying online interaction and behavior is vital, as offline inequalities frequently manifest in virtual environments (Lind, 2019).

The rise in online hate speech in sports is an escalating concern, as fans, players, and officials often face racist abuse on social media platforms (Kearns et al., 2023). Sports are deeply infused with meritocratic ideals, which highlight hard work and talent as the main explanations for success or failure, both on and off the field (Hylton, 2009; Kilvington, 2016). These meritocratic views influence individuals’ experiences in sports while minimizing the considerable impact of social structures that either facilitate or hinder access to sporting opportunities. This creates an illusion of a natural order, where individuals are perceived as being in control of their destinies and solely accountable for their successes, appearing unaffected by barriers or societal influences. As a result, sports are frequently depicted as inherently fair and accessible, which can obscure the reality of racial inequalities and downplay the significance of race in shaping individuals’ experiences (Bimper, 2015). Patel (2017) further elaborates that whiteness is not just about phenotypic traits; it has established a social position that confers social, cultural, and economic privileges to those identified as white.

Despite the long-standing connection between sports and racial politics, it may come as a surprise that sports organizations have only begun to seriously address racial equality in the last 40 years. Consequently, racial equality is still a relatively recent focus within the sports industry. Although there have been some advancements, current trends suggest a regression in progress, with both overt racism and various forms of discrimination in sports and society increasing (Kilvington et al., 2022). For instance, during the 2018-2019 season, hate crimes related to football in England and Wales resulted in 193 reports of hate speech, 79 percent of which were racist, reflecting a 51 percent increase from the previous season. Additionally, reports of hate speech have steadily risen over the past seven seasons (Cable et al., 2022). Factors such as anonymity, invisibility, and the rapid nature of social media interactions have intensified online racism and abuse in sports (Kilvington, 2020). This environment can create a sense of daring and freedom among fans, leading to the proliferation of racist beliefs, Islamophobia, and xenophobia, which, although experiencing a general decline in offline expressions in recent decades, have not disappeared (Brown, 2018). Social media has provided a glimpse into private thoughts and beliefs that were once restricted to behind-the-scenes environments (Hylton & Lawrence, 2016).

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs thematic analysis to investigate discourses surrounding online racism, leveraging its methodological strength in identifying and interpreting recurring themes and patterns within qualitative data (Huang et al., 2024).

The modern digital era has given rise to a growing trend of individuals voicing their opinions and values through blogs and participation in online conversations(Mariani & Borghi, 2020). These interactions, often categorized as textual discourses, encompass both written and verbal exchanges, including discussions and debates on focused topics (Onoja et al., 2022). Textual discourses play a pivotal role in shaping people’s attitudes and actions, offering rich insights for scholarly exploration (Li et al., 2018). In pursuit of the research objectives, a methodology rooted in critical discourse analysis was chosen, drawing inspiration from various disciplines including discursive psychology, ethnomethodology, and Foucauldian approaches (Jaworski & Thurlow, 2010) This approach perceives language as a “social practice,” scrutinizing how texts either contribute to, challenge, or perpetuate social and political power dynamics (Fairclough, 2013) and is considered suitable for uncovering insights in emerging and less-explored research areas including the present case which delves into the intricate layers of complexity.

Data Collection

In the initial stage of the research, a Google search was conducted using the combination of keywords “sport online racism” and “cyber racism sport” which yielded a total of 47 URLs. Subsequently, all of the links were manually reviewed, and 30 online discussions were selected as eligible for thematic disclosure analysis (appendix). Finally, the content from the 30 eligible sources was extracted and imported into Maxqda 2020 for further analysis.

Data Analysis

TA is particularly suited for this research due to its flexibility and capacity to generate rich, detailed insights into complex social phenomena, such as the interplay of language, power, and identity in digital spaces (Clarke and Braun, 2017) (Berbekova et al., 2021; Clarke & Braun, 2017). Beyond summarizing data, TA enables deeper interpretation, aligning with the study’s critical discourse analysis framework, which views language as a social practice embedded in power dynamics (Fairclough, 2013).

The analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) widely recognized six-step framework, adapted to ensure rigor and transparency in handling 30 selected online discussions. The first step, data familiarization, involved immersive engagement with the dataset (Lawless & Chen, 2019) through repeated reading to capture tone, recurring phrases, and emotive language related to online racism in sports. In the second step, initial coding, the smallest meaningful units of data (codes) were developed to capture key elements relevant to the research question. MAXQDA-2020 was used to facilitate this process, as widely recommended in qualitative research (Moustakas, 2023; Rashid and Al-Zaman, 2023). Using software in thematic analysis enhances systematic and rigorous data analysis while ensuring credibility and reliability (Daif and Elsayed, 2025). Segments of text were tagged with descriptive labels (e.g., “hide,” “tangible repercussions,” “legal systems”) to capture explicit and implicit meanings, resulting in 76 initial codes. Following Schinke et al. (2013), each author independently reviewed and coded the data before engaging in collaborative sessions to compare and refine the coding through inter-coder agreement, ensuring consistency and reliability.

In the third step, related codes were clustered into broader patterns to identify themes (Campbell-Fox et al., 2024). For instance, codes such as “Canceling membership,” “Banning,” and “Suspension” were grouped under the preliminary theme “Stronger accountability.” In the fourth step, theme review, the coherence and distinctiveness of each theme were rigorously assessed by cross-checking against coded extracts and the full dataset. Through extensive discussions, a 95% inter-coder agreement was achieved. The fifth step, defining and naming themes, involved refining categories into concise, meaningful labels (Kiger and Varpio, 2020). For example, “Technology-driven mitigation solutions” was defined as technological and individual efforts to counter online racism. Finally, in the sixth step, producing the report, findings were synthesized into a narrative that integrated thematic insights with illustrative data excerpts (e.g., direct quotes from Reddit threads or blog comments).

3. Results

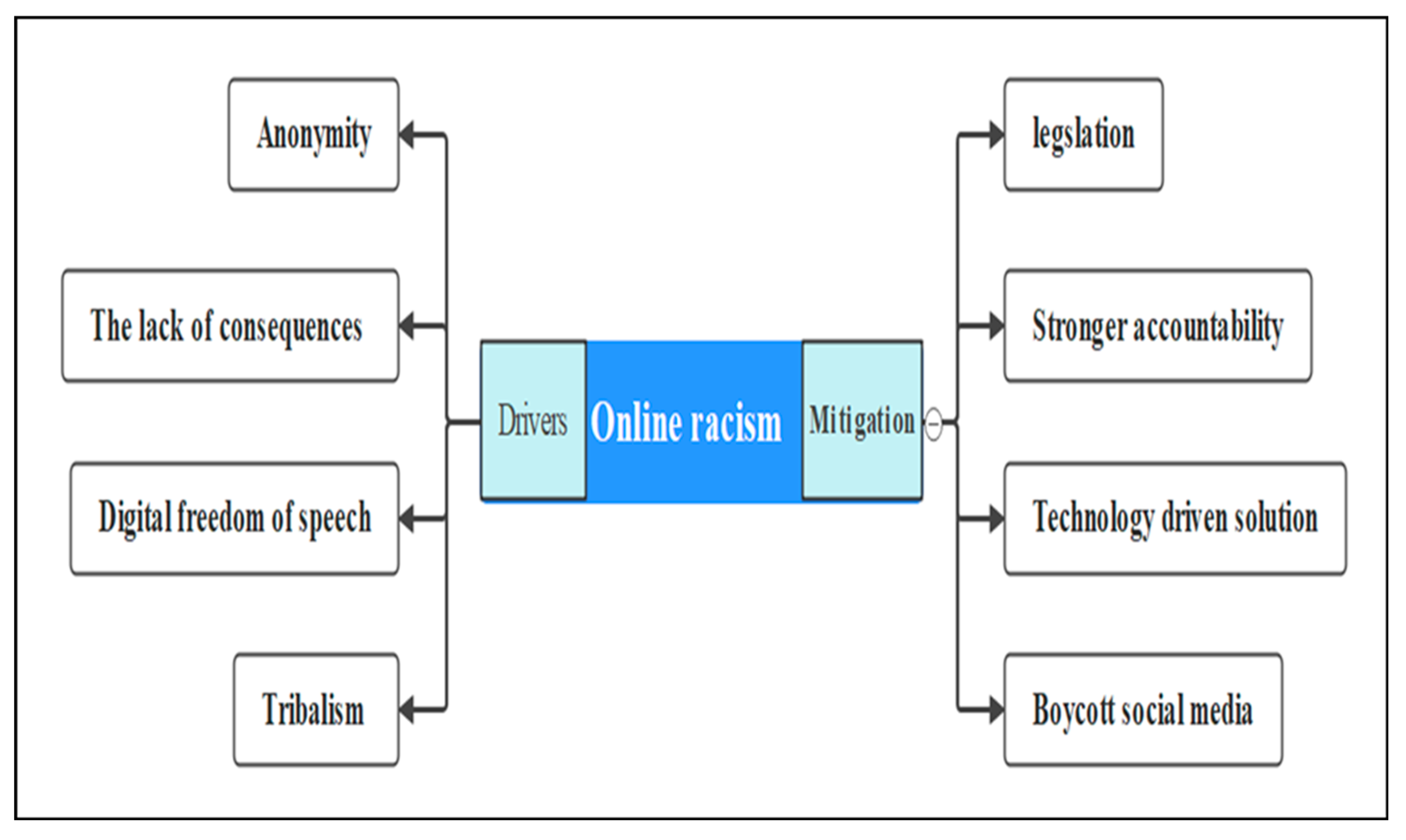

The results of discourse analysis showed that several factors can be effective in the formation of online racism in sports, the most important factors are:

Anonymity refers to a state where a person’s identity is not easily identifiable. While achieving anonymity requires effort in the physical world, it is relatively easy to attain in online communication (Berg, 2016). Anonymity is considered a double-edged sword, as it can empower individuals to act without fear of judgment but also contribute to a lack of civility in online discussions (Robinson, 2017). Actualy, it allows users to feel liberated from the moral and psychological constraints that govern offline decorum. Second, it provides a sense of security for those who engage in online racism and abuse, as they are less likely to face punishment. However, anonymity also enables users to avert their gaze and remain physically removed from the impact of their hateful expressions (Cable et al., 2022).

Anonymity significantly affects the expression of racism online. The perceived lack of accountability and social consequences in online environments can embolden individuals to engage in racist behaviors they might hesitate to exhibit face-to-face (Nadim, 2023). Anonymity also enables the expression of racism in sports, where individuals can hide behind fake usernames or profiles, feeling more comfortable expressing racist views (Ortiz, 2021). The important role of anonymity is illustrated in statements like ““anonymity is the golden ticket for racists” (apnews.com). Similarly, the sentiment, “anonymity increases the racial abuse severity” (

www.lboro.ac.uk) also highlighted the key role of anonymity on social media and online racism.

As we all know by this point, Twitter and other social media platforms allow these idiots to hide behind a keyboard and tell others how they really feel. It’s disgusting.( https://www.reddit.com/)

- 2.

The lack of consequences for online racism

One of the key challenges in addressing racism on online platforms is the perceived lack of meaningful consequences for such behavior. This perception of impunity can unfortunately encourage some individuals to engage in racist speech and actions, knowing they may face little accountability (Kassimeris et al., 2022). Actualy, the virtual nature of online interactions can create a disconnect between actions and real-world consequences. Racist behavior that might result in social ostracization, professional repercussions, or legal penalties in the physical world may not carry the same weight in the digital realm. This lack of tangible repercussions can embolden people to say and do things they would never dare in person (TaeHyuk Keum & Hearns, 2022). The following quotes demonstrate how Lack of consequence can encourage some individuals to engage in online racism:

“It’s simply unacceptable that people across English football, and society more broadly, continue to be subjected to discriminatory abuse online on a daily basis, with no real-world consequences for perpetrators” (www.theguardian.com).

“And that is why there is this horrible culture of abuse that is taking place day in, day out without any consequences for many individuals all over the world.” (www.aljazeera.com)

“A large part of what prevents people from being unkind, selfish, rude, cruel (etc), is their own image and the consequences of their actions. These people are not going to yell at someone on the street but they will yell at a stranger on the internet. They can do it, shut down the computer and get on with their day without repercussions” (quora.com).

“It’s simply unacceptable that people across English football and society more broadly continue to be subjected to discriminatory abuse online on a daily basis, with no real-world consequences for perpetrators” (edition.cnn.com).

- 3.

Digital freedom of speech

The rise of the internet and social media has greatly expanded opportunities for free expression and the exchange of ideas. However, this increased freedom has also enabled the spread of racism and hate speech in online spaces (Kavanagh et al., 2022). The internet has given people an unprecedented ability to express and share their views. At the same time, the anonymity and lack of accountability online can embolden some to engage in racist harassment and hate speech (Costello et al., 2019).

“people have the freedom of speech in good and bad, especially on the interwebs”.(reddit.com)

By taking advantage of online factors such as online anonymity and beliefs in “digital freedom of speech,” people with racist ideologies have been taking to online platforms to share their racist views and spread hate speech without accountability

- 4.

Tribalism

Fans often feel a strong sense of loyalty and identity with their favorite sports teams. When their team is competing against another, it can bring out a tribal mindset where they see the other side as the enemy. In this charged atmosphere, some fans may resort to using racist language or stereotypes to try and demean the opposing team and its players (Cable et al., 2022; Hayday et al., 2021). Statements like “

Football fandom becomes a vicious circle of tribalism and hate.” (theconversation.com) and “Tribalism - ‘birds of a feather flock together’ - you might not find people like you, near you… but the Internet makes distance irrelevant so you can gang up with people like you from all over the state, country, world” (

www.quora.com), indicated that tribalism leading to both passionate support and harmful behavior such as racism.

Mitigation Strategies

The regulation of social media platforms is a complex and contentious issue. While completely preventing the use of the internet for hate speech and abuse may not be feasible, there are steps that can be taken to address the consequences of such behavior. Actually, online platforms, governments, legal systems, and sporting organizations through legislation can work to mitigate the harms of online racism (Kavanagh et al., 2022). According to Kilvington et al. (2022) anti-racism legislation have changed the Premier League and culture of football fandom, making it less tribal and more family-oriented. This is illustrated in statements like “Ultimately, the biggest change will likely come through legislation. Last month, the European Union clinched an agreement in principle on the “Digital Services Act”, which will force big tech companies to better protect European users from harmful online content or be punished with billions of dollars in fines for noncompliance. In Britain, the government has proposed the Online Safety Bill, with potential fines amounting to 10% of the platforms’ annual global turnover” (apnews.com).

- 2.

Stronger accountability

The lack of consequences and accountability online can embolden some individuals to engage in racist behavior, as they may feel less constrained by social norms and expectations compared to the offline world (Oshiro et al., 2020). Accordingly, online platforms, governments, legal systems, and sporting organizations need to work to hold individuals accountable for their online racist behavior (Kavanagh et al., 2022). They should take appropriate action against users who engage in racism, including suspensions, bans, or legal consequences when necessary. This sends a strong message that online racism will not be tolerated. For instance,

Canceling membership: for example, the Brisbane Lions have cancelled the membership of a fan who racially abused Adelaide Crows player Izak Rankine on social media during their recent AFL match (abc.net.au/).

Banning: for example, the UK Home Secretary plans to extend football banning orders to cover online racist abuse, following disgraceful incidents targeting England players. The new law aims to curb online hate by imposing 3–10-year match bans on individuals convicted of such offenses(gov.uk).

Suspension: for example, Twitter and Facebook removed thousands of abusive posts and suspended accounts following racist attacks on England players after the Euro 2020 final (news.trust.org)

- 3.

Technology driven mitigation solution

The rise of online racism, expressed through both subtle and overt means, poses significant challenges for social media platforms. Racist content can spread rapidly, often hidden behind memes or fake identities, inciting hatred and social instability. To effectively address this issue, a critical step is enhancing the capabilities of online platforms to detect and moderate racist content more effectively. This involves:

AI-Powered Detection:

Investing in more advanced AI and machine learning algorithms to automatically identify and flag potential instances of racist content. This is illustrated in statements like “FIFA President Gianni Infantino hailed an AI-powered tool from the data science company Signify Group, for its ability to identify the perpetrators of hate speech — and not just to the social media sites where the comments are made. We are reporting them to the authorities so that they are punished for their actions”(thenewstack.io/).

User Reporting

As one of the strategies suggested by individuals in disclosure (for instance: “I would encourage you to report these people, if you feel safe doing so. Without consequences, this sort of behaviour will continue.” (reddit.com)) was reporting, accordingly Making it easier for users to report racist content, can be effective way. Similarly, the following statements in the official website of the Premier League also highlight the importance role of reporting as an effective strategy:

“If you see online abuse directed at players, managers, coaches, match officials and their families, you can report it to the Premier League using the form below”

- 4.

Boycott social media:

Athletes have participated in social media boycotts as a form of protest against the relentless online abuse and racism they face. For example, A 4-day boycott by football leagues, clubs and players in Britain in April-May 2021 aimed to pressure social media companies to do more to protect users from discriminatory abuse (Barker & Jurasz, 2024)(

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

The findings of this article highlight the complex nature of anonymity in online communications, particularly regarding its impact on racism. In summary, online anonymity plays a major role in the widespread occurrence of racism, especially in direct and overt expressions, within digital spaces compared to offline settings. Anonymity acts as a double-edged sword, granting individuals the freedom to express themselves without fear of consequences while simultaneously creating a conducive environment for hate speech and aggression (Hardaker, 2010). This duality in understanding the motivations behind racist expressions in digital spaces is crucial. Online platforms substantially lower the barriers for individuals to engage in behaviors they might otherwise avoid in face-to-face interactions. This finding is consistent with earlier research indicating that feelings of invisibility and a sense of trust in online settings can lead individuals to act differently than they would in other contexts (Bargh & McKenna, 2004). Furthermore, the quotes referenced in this research reinforce the notion that anonymity is not merely a protective measure for individuals but also facilitates harmful ideologies. Phrases like “anonymity is the golden ticket for racists” encapsulate the concern that anonymity allows for unchecked expressions of bias, intensifying the severity and prevalence of racial abuse in online discussions. This environment can create a toxic atmosphere and influence social attitudes toward racism, potentially diminishing individuals’ sensitivity to the harms caused by such statements. This virtual courage, arising from online anonymity, may also inspire individuals to express their dedication to social justice and take a public anti-racist position, even among those who might not have the bravery or motivation to do so in offline environment (Keum & Miller, 2017). The failure to identify these individuals can lead to a significant increase in visits to such platforms, as users feel protected from social consequences and accountability in the real world. This phenomenon is exacerbated in environments like sports, where competitive fervor and anonymous profiles can amplify racist sentiments without immediate repercussions.

One of the main issues is the lack of consequences for online racism and its real-world implications. Anonymity enables users to openly share their racist ideologies with minimal accountability or oversight (Hardaker, 2010; Hughey & Daniels, 2013a; Suler, 2004). In these anonymous contexts, individuals might engage in racist remarks online, despite likely avoiding such comments in face-to-face situations (Keum & Miller, 2018). The provided quotes reflect a widespread awareness of this lack of accountability. For instance, individuals’ interpretations of experiences encountered in sports mirror broader social concerns about how online platforms fail to protect users from discriminatory abuse. Keum and Miller (2017) suggested that racism is significantly more widespread and prevalent on the internet, a viewpoint echoed by other researchers who have highlighted the ongoing existence of racist content online (J. Daniels, 2012; Keum & Miller, 2017; Tynes et al., 2004). Drawing from qualitative data collected from 132 participants, Keum (2017) discovered that online users feel that (1) the internet offers an anonymous platform and virtual courage that encourages offenders to express racist views, and (2) online racism is often encountered regularly, sometimes on a daily basis, due to the increased access and convenience of vast online content. This social norm of immunity from punishment not only perpetuates a toxic online environment but also undermines efforts to combat racism, as highlighted by Kassimeris and colleagues (2022). T. Hyuk Kim and Herns (2022) stated that the perception of expressing hateful sentiments without facing repercussions may create a cycle of abuse, where the lack of deterrents promotes further misbehavior. This underscores the need for clearer guidelines and more stringent enforcement of policies on online platforms to bridge the gap between the consequences in the virtual world and the real world.

This research underscores a complicated paradox of the digital age. Although the rise of the internet and social media has created an enriching space for free expression and varied discourses, it has also contributed to the proliferation of racism and hate speech. This situation has played a significant role in obstructing online deterrence, enabling individuals to partake in racist expressions with a minimal sense of accountability for their actions (Hardaker, 2010). This duality emphasizes a critical issue in contemporary society: the need to balance empowering individuals to express their opinions with the necessity of curbing harmful narratives. The anonymity provided by online platforms serves as a shield for individuals who might not express such views in face-to-face interactions. This phenomenon is backed by the theory of disinhibition, which suggests that greater anonymity can encourage behaviors that are unrestrained or significantly different from those that would typically manifest in identifiable situations (Bargh & McKenna, 2004; Berg, 2016). This psychological distance can encourage users to engage in racist or hateful dialogues, as the usual social consequences of such behavior diminish in virtual environments. Additionally, the belief in “digital freedom of expression” creates a culture where harmful ideologies can spread unchecked, often outpacing efforts to counter them. This situation poses significant challenges for policymakers, social media companies, and civil society in addressing hate speech while maintaining legitimate freedom of expression. Moreover, the intersection of online behavior and social attitudes appears to deepen social divides, as spaces around these harmful ideologies take shape. The ability to manage content and connect with like-minded individuals reinforces pre-existing beliefs and fosters environments where hate can thrive.

The findings of this article also highlight the dual nature of sports fandom, where intense loyalty can enhance social bonds while simultaneously fostering negativity and aggression towards rivals. Here’s a rephrased version of your text with altered sentence structures to reduce similarity while preserving the original meaning: Given the opportunity for like-minded individuals to connect through the internet, users can actively support various organizations that promote racial equality and social justice (Keum & Miller, 2017). This in-group bias can create a group dynamic in which individuals with similar views unite in solidarity, further strengthening their opinions after participating in discussions or debates. These online social environments may offer a safe and empowering space for individuals to share their experiences with racism, allowing them to receive validation and empathy from their peers. However, this form of online tribalism may cause individuals to behave differently than they would in face-to-face interactions or to act in stark opposition to those who hold differing beliefs (Cable et al., 2022; Hayday et al., 2021). This “tribal mentality” frequently transforms the identities of fans, forging a close connection between them and their teams, which fosters an “us versus them” perspective. When individuals engage with others who hold similar prejudiced beliefs and attitudes, they may experience a reinforcement of these views due to the solidarity of the group. Although this sense of solidarity can enhance feelings of belonging and shared happiness during victories, it can also give rise to harmful behaviors, such as employing racist language and stereotypes against rivals. While group polarization on the internet can have positive effects, like strengthening solidarity for social movements that advocate for human rights and equality (Christopherson, 2007), it can also have negative consequences, as it perpetuates polarizing attitudes and opinions that fuel racist expressions and ideologies. The internet can act as a breeding ground for collective hostility, facilitating the rapid spread of negative sentiments within communities and nurturing an environment where derogatory language is normalized.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The regulation of social media platforms carries significant scientific and practical implications, particularly in addressing hate speech and online abuse. While the complete eradication of such behavior may be unrealistic, collaborative efforts among online platforms, governments, legal systems, and sports organizations can effectively mitigate the negative impacts of online racism (Christopherson, 2007). This requires a comprehensive understanding of the scientific underpinnings of online behavior and existing practical interventions. The enforcement of anti-racism laws, as highlighted by Kilvington et al. (2022), has already had significant effects on the culture of football fandom in the Premier League, transforming it into a family-oriented environment. This shift emphasizes the importance of legislation not only as a punitive measure but also as a tool for fostering an inclusive culture. The European Union’s agreement on the “Digital Services Act” exemplifies this approach, mandating technology companies to enhance user protection against harmful content. Non-compliance can result in severe financial penalties, creating a strong incentive for platforms to prioritize user safety and well-being (apnews.com). From a scientific perspective, understanding the psychological and sociological dimensions of how online interactions shape group behavior is crucial for comprehending the mechanisms behind hate speech and abuse. Research indicates that anonymity and lack of accountability online can lead to an increase in hate speech, suggesting that better moderation tools and clearer community guidelines could reduce such occurrences (Suler, 2004). Practically, the integration of laws and technological advancements offers a pathway to safer online environments. Initiatives like the Online Safety Bill in the UK, which carries the risk of imposing fines based on global turnover, reflect a growing recognition of the need for robust regulatory frameworks. Such measures not only hold platforms accountable but also empower users, encouraging them to report abuse and play a decisive role in shaping online culture.

Understanding the psychological motivations behind online racism is essential. Studies show that individuals who engage in such behavior may feel empowered by a perceived detachment from traditional social consequences, leading to an escalation of hate speech. Therefore, implementing stronger accountability measures not only addresses overt acts of racism (Kavanagh et al., 2022) but also helps disrupt the underlying psychological mechanisms that enable such behavior. In practice, enforcing consequences for online racism can take various forms, including suspensions, bans, and even legal repercussions. High-profile cases, such as the Brisbane Lions’ decision to revoke membership due to racist comments directed at player Isaac Rankin, demonstrate the effectiveness of swift action in curbing toxic behavior (abc.net.au). Similarly, the UK government’s intention to extend football banning orders to cover online racist abuse reflects a growing recognition that digital spaces deserve regulation just as much as physical environments (gov.uk). These measures aim not only to punish offenders but also to establish a clear social standard that online racism is unacceptable. Furthermore, social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook have begun to adopt more aggressive stances against online racism, removing thousands of offensive posts and suspending accounts following racist incidents directed at England players after the Euro 2020 final (news.trust.org). These actions not only protect affected individuals but also foster an online culture where racist behavior is publicly condemned and acted against. As a result, a stronger accountability framework for online racist behavior is essential. By integrating scientific insights into the motivations behind such behavior with practical enforcement strategies, society can begin to dismantle the permissive environments that thrive online. This comprehensive approach not only holds individuals accountable but also encourages the development of healthier and more inclusive digital spaces. As more organizations and governments take action, the ripple effect can strengthen a culture of respect both online and offline.

One effective strategy to combat online racism is to enhance the capabilities of online platforms to identify and moderate racist content. One of the most promising approaches involves integrating artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms specifically designed to detect racist content. These advanced technologies can automatically flag potential instances of hate speech, significantly reducing the time needed for human moderators to intervene. For example, Gianni Infantino, the president of FIFA, praised an AI-based tool developed by Signify Group for its effectiveness in identifying perpetrators of hate speech. This tool highlights the need for accountability, as identified users are reported to authorities for further action, reinforcing the idea that online behavior can have real-world consequences (thenewstack.io/). Encouraging public vigilance plays a crucial role in moderating online interactions. As noted in various online communities, users often suggest that reporting can deter individuals from making racist comments. This sentiment emphasizes the shared collective responsibility of users to maintain a respectful digital environment. Furthermore, the official Premier League website underscores the importance of reporting in its community guidelines: Here’s a rephrased version of your sentence: “If you witness online harassment targeting players, managers, coaches, match officials, or their families, you can report it to the Premier League by using the form provided below.” This proactive approach not only aids in immediate moderation but also sends the message that racist behavior is unacceptable and will be addressed. The combination of advancements in AI with user reporting creates a multifaceted approach to tackling online racism. Collaboration between social media platforms, government bodies, and non-profit organizations can further strengthen these initiatives. Joint efforts in other areas have demonstrated effectiveness, as shown in projects like the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT), which showcases the benefits of shared resources and data among various stakeholders. Addressing online racism requires a robust, technology-based framework that incorporates AI-driven detection tools and user interaction through reporting mechanisms. As platforms like FIFA and the Premier League set standards for accountability and community engagement, it becomes clear that collective action is essential to strengthen a more inclusive digital world. Ongoing investment in these technologies, along with fostering a culture of reporting, is crucial for reducing online racism and ensuring a safer online environment for all users.

Coordinated demonstrations focused on addressing online abuse and racism highlight the pressing necessity for social media platforms to assume accountability for safeguarding their users. The growing trend of athletes participating in social media boycotts highlights a significant intersection of sports, social justice, and technology. An important instance took place in April-May 2021, when football leagues, clubs, and players across the UK came together for a four-day boycott to draw public awareness to the problem of online discriminatory behavior (Barker & Jurasz, 2022). This movement reflects an increasing acknowledgment of the psychological effects of online harassment on individuals, particularly in high-stress environments like professional sports. Research has shown that athletes exposed to online abuse may experience heightened stress, anxiety, and depression (Gorges & Konetzka, 2021). This not only impacts their mental health but also affects their performance on the field, indicating a direct link between social media interactions and athletic efficacy. In practice, the boycotts serve as a catalyst for discussions about the responsibilities of social media companies. In response to public pressure, these platforms are compelled to strengthen their moderation policies and implement more effective measures against hate speech and abusive behavior. Initiatives such as increased transparency in reporting violations, stronger AI moderation tools, and more robust community guidelines are likely to amplify discussions arising from these boycotts. With a growing awareness of online abuse, athletes can garner public support for policy changes and accountability, leading to legal reforms that could more effectively protect users. These reforms may include advocating for stronger regulations that require social media platforms to take action against hate speech and harassment. As a result, the social media boycotts initiated by athletes not only draw attention to the issue of online abuse but also guide scientific research on the psychological consequences of these experiences while compelling social media companies and policymakers to take decisive action. Such movements are essential for creating a safer and more inclusive digital environment for all users.

Ultimately, the implications of social media regulations significantly affect how communities interact and shape social norms regarding acceptable behavior. By establishing evidence-based laws and strengthening collaborative relationships among stakeholders, society can gradually create a more inclusive and secure digital landscape. This comprehensive strategy not only tackles current issues but also establishes a foundation for a more sustainable and healthier online atmosphere in the future.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes the dual nature of online anonymity, which facilitates both freedom of expression and the potential for hate speech and aggression (Hardaker, 2010). It indicates that online environments reduce barriers that might otherwise prevent racist comments in face-to-face interactions, confirming previous studies that show feelings of invisibility and online trust promote behaviors markedly different from those in offline spaces (Bargh & McKenna, 2004). This effect reinforces the idea that anonymity is not merely a protective measure but a catalyst for harmful ideologies, creating a toxic space that can desensitize individuals to the impact of racialized discourse and ultimately influence social attitudes toward racism. Furthermore, studies should explore how to leverage the positive aspects of online anonymity to strengthen commitments to social justice and public anti-racist stances, potentially transforming virtual courage into real-world activism. What roles do social media influencers play in shaping attitudes toward racism, and how can positive examples be promoted? Understanding the multifaceted nature of online interactions is vital for addressing the persistence of racism in digital spaces. By examining the negative and positive potentials of anonymity, researchers can provide valuable insights for combating racial biases and promoting inclusivity in online communities. An additional question is how different online platforms may uniquely contribute to or deter expressions of racism, warranting platform-specific studies.

Evidence suggests that there is a significant gap between virtual anonymity and accountability when examining the phenomenon of online racism and its real-world consequences. The ability of users to express racist ideologies online without fear of repercussions creates an environment where such behaviors can flourish. Notably, anonymity allows individuals to engage in racist discourse that they might avoid in face-to-face interactions, as noted by researchers like Hye and Daniels (2013) and Keum and Miller (2018). Future studies could also investigate how the perceived anonymity influences the severity and frequency of racist remarks online, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between anonymity and hate speech. Furthermore, studies indicate that online platforms often fail to protect users from discriminatory abuse, highlighting systemic issues in digital environments (Keum & Miller, 2017). The widespread persistence of racist content across the internet not only fuels a toxic online atmosphere but also undermines efforts to effectively combat racism (Kassimeris et al., 2022). Examining the effectiveness of current moderation practices and content policies could offer insights on how to improve them—these inquiries will be essential for creating healthier online ecosystems. The cycle of hate speech reinforces an ecosystem that encourages harmful behaviors and normalizes racist sentiments (TaeHyuk Keum & Hearns, 2022). Addressing these challenges, it is clear that clearer guidelines and stricter enforcement of policies on online platforms are essential to bridging the gap between virtual interactions and real-world consequences. This necessitates a multifaceted approach that considers the complexities of anonymity and user responsibility.

This study highlights the complex paradox of the digital age, revealing a dual reality: the internet and social media have fostered an environment rich in free expression and diverse discourses while simultaneously facilitating the spread of racism and hate speech. This dynamic is recognized as a key deterrent factor in online limitations, allowing individuals to engage in racist expressions with minimal fear of accountability due to perceived risks (Hardaker, 2010). The anonymity provided by online platforms acts as a shield for individuals who might otherwise refrain from expressing such views in face-to-face interactions. This occurrence is in line with the disinhibition theory, which illustrates how greater anonymity can result in more pronounced or varied human behaviors that are less likely to manifest in identifiable contexts (Bargh & McKenna, 2004; Berg, 2016). Such psychological distancing can encourage users to participate in racist or hateful discussions, as the usual social consequences of such behavior are muted in a virtual environment. Furthermore, the belief in “digital freedom of expression” cultivates a culture where harmful ideologies can proliferate unchecked, often outpacing efforts to counter them. The intersection of online behavior and social attitudes appears to deepen social divides, as spaces for these harmful ideologies expand. The ability to manage content and connect with like-minded individuals reinforces pre-existing beliefs and fosters environments where hate can thrive. Consequently, this research emphasizes the necessity of addressing the complexities of digital communications and their implications for social norms. Future studies should examine the cognitive and social mechanisms that drive individuals toward hate speech in online environments. Longitudinal research can reveal how online interactions shape social attitudes over time, and interventions aimed at reducing online hate can be empirically tested for effectiveness. One innovative approach might involve using machine learning to analyze large datasets of social media interactions to identify patterns and predict behaviors related to hate speech. Additionally, comparative studies across different regions can provide insights into how cultural contexts influence the phenomenon of digital hate speech. Investigating the role of platform algorithms in amplifying or suppressing harmful content is also an important avenue for research, as is exploring user experiences of accountability and anonymity. By understanding these dynamics, more effective strategies can be developed to balance freedom of expression with the need to protect individuals and communities from the dangers of hate speech in digital contexts.

Platforms on social media can create a supportive and empowering space for individuals to express their experiences with racism while gaining validation and understanding from others. However, this online tribalism can lead individuals to engage in behaviors that differ from their usual personalities, often displaying different behaviors toward those with opposing views (Cable et al., 2022; Hayday et al., 2021). This “tribal mentality” often alters the identity of supporters, connecting them closely to their teams while simultaneously fostering an “us versus them” mindset. When people engage with others who hold similar biases and beliefs, they may experience a strengthening of these views as a result of group solidarity. While this can enhance a sense of belonging and shared joy during victories, it can also lead to harmful behaviors, including the use of racist language and stereotypes against opponents. In summary, the complex interplay between sports fandom and social dynamics demonstrates a dual effect: increased loyalty can strengthen a sense of community and belonging while simultaneously leading to divisive and sometimes harmful behaviors toward rival groups. Future research should explore the mechanisms through which online communities influence fan behavior. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the long-term effects of online fandom on real-world social interactions can provide valuable insights into how these interactions shape attitudes and behaviors over time. Understanding how to leverage the positive aspects of online fan communities while mitigating negative consequences is essential for fostering a healthier sports culture. Efforts should also be made to educate fans on promoting inclusive and respectful discourse in online spaces.

In conclusion, it is essential to understand that the influence of what can be characterized as virtual reality (i.e., the internet) should not be underestimated, as there is no justification for any form of racism. Our research indicates that individuals may feel more inclined to express racist views and opinions in a clearer, more common, and perhaps more explicit manner in online interactions as opposed to face-to-face ones. A significant factor behind online racism is likely the anonymity that the internet provides, which may help to justify and contextualize the dynamics and structures of racism within our society. This situation often privileges dominant groups, such as whites, over minority populations, allowing these dynamics to be sustained and reproduced in online settings.

Moving forward, future empirical research and theoretical frameworks ought to concentrate on elucidating the relationship between online and offline contexts in terms of the ongoing presence of racism. Most of the controversial racist incidents that occur in society have now gone viral in the digital sphere, creating a platform that can readily amplify people’s exposure to content highlighting racial discrimination, harassment, and violence. It is vital to evaluate the ramifications of online racism, while simultaneously recognizing the internet as a platform that can also amplify anti-racist voices. To effectively combat and diminish racial hatred online, it is necessary to devise policy recommendations grounded in empirical evidence. This ongoing conversation plays a crucial role in advancing toward a more equitable and informed digital future.

References

- Azzarito, L., & Harrison, L. (2008). ‘ White Men Can ’ T Jump ’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 4(April 2007), 347–364.

- Back, L. (2002). Aryans reading Adorno: cyber-culture and twenty-firstcentury racism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25(4), 628–651. [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J. A., & McKenna, K. Y. A. (2004). The Internet and social life. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 573–590. [CrossRef]

- Barker, K., & Jurasz, O. (2022). # MeToo, Sport, and Women: Foul, Own Goal, or Touchdown? Online Abuse of Women in Sport as a Contemporary Issue. Workshop on Sports and Human Rights, 71–93.

- Barker, K., & Jurasz, O. (2024). \#{MeToo}, {Sport}, and {Women}: {Foul}, {Own} {Goal}, or {Touchdown}? {Online} {Abuse} of {Women} in {Sport} as a {Contemporary} {Issue}. In V. Boillet, S. Weerts, & A. R. Ziegler (Eds.), Sports and {Human} {Rights} (pp. 71–93). Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Berg, J. (2016). The impact of anonymity and issue controversiality on the quality of online discussion. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(1), 37–51.

- Berbekova, A., Uysal, M., & Assaf, A. G. (2021). A thematic analysis of crisis management in tourism: A theoretical perspective. Tourism Management, 86, 104342.

- Berkman, F. (2013). How the world consumes social media. Retrieved May, 3, 2014.

- Bimper Jr, A. Y. (2015). Lifting the veil: Exploring colorblind racism in Black student athlete experiences. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 39(3), 225–243.

- Blum, L. (2004). Systemic and Individual Racism, Racialization and Antiracist Education. Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/1477878504040577, 2(1), 49–74. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Brown, A. (2018). What is so special about online (as compared to offline) hate speech? Ethnicities, 18(3), 297–326.

- Bulhan, H. A. (2004). Frantz Fanon and the psychology of oppression. https://books.google.com/books/about/Frantz_Fanon_and_the_Psychology_of_Oppre.html?id=jJ0aID8V3xgC.

- Cable, J., Kilvington, D., & Mottershead, G. (2022). ‘Racist behaviour is interfering with the game’: exploring football fans’ online responses to accusations of racism in football. Soccer & Society, 23(8), 880–893.

- Cavalier, E. S., & Newhall, K. E. (2018). ‘Stick to Soccer:’fan reaction and inclusion rhetoric on social media. Sport in Society, 21(7), 1078–1095.

- Christopherson, K. M. (2007). The positive and negative implications of anonymity in Internet social interactions:“On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog.” Computers in Human Behavior, 23(6), 3038–3056.

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The journal of positive psychology, 12(3), 297-298.

- Coombs, D. S., & Cassilo, D. (2017). Athletes and/or Activists: LeBron James and Black Lives Matter. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 41(5), 425–444. [CrossRef]

- Costello, M., Hawdon, J., Bernatzky, C., & Mendes, K. (2019). Social group identity and perceptions of online hate. Sociological Inquiry, 89(3), 427–452.

- Criss, S., Michaels, E. K., Solomon, K., Allen, A. M., & Nguyen, T. T. (2021). Twitter fingers and echo chambers: Exploring expressions and experiences of online racism using twitter. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8, 1322–1331.

- Daniels, J. (2012). Race and racism in Internet Studies: A review and critique. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/1461444812462849, 15(5), 695–719. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, N., Gillen, P., Casson, K., & Wilson, I. (2019). STEER: Factors to Consider When Designing Online Focus Groups Using Audiovisual Technology in Health Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, N. (2015). Constructing the Digitalized Sporting Body. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/2167479515584045, 4(3), 303–330. [CrossRef]

- Dunning, E., Murphy, P., Williams, J., & Maguire, J. (1984). Football hooliganism in britain before the first world war. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 19(3–4), 215–240.

- Elias, S. (2015). Racism, Overt. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Eschmann, R. (2020). Unmasking racism: Students of color and expressions of racism in online spaces. Social Problems, 67(3), 418–436.

- Esomar. (2018). GLOBAL MARKET RESEARCH 2018. Https://Www.Esomar. Org/Knowledge-Center/Reports-Publications, 1–135. https://esomar.org/global‐market‐research.

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Routledge.

- Farrington, N., Hall, L., Kilvington, D., Price, J., & Saeed, A. (2017). Sport, racism and social media. Routledge.

- Ferreira, A. S. S., Leite, E. L., Muniz, A. S., Batista, J. R. M., Torres, A. R. R., & Estramiana, J. L. Á. (2017). Insult or prejudice: a study on the racial prejudice expression in football. Psico, 48(2), 81–88.

-

Fundamental rights survey | European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2021). European Union Agency For Fundamental Rights. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2021/fundamental-rights-report-2021.

- G Patel, T. (2017). It’s not about security, it’s about racism: Counter-terror strategies, civilizing processes and the post-race fiction. Palgrave Communications, 3(1), 1–8.

- Galtung, J. (1991). The sport system as a metaphor for the world system. Sport... The Third Millennium. Québec: Les Presses de L’Université Laval.

- Garcia, C. J., & Proffitt, J. M. (2022). Recontextualizing barstool sports and misogyny in online US sports media. Communication & Sport, 10(4), 730–745.

- Gorges, R. J., & Konetzka, R. T. (2021). Factors associated with racial differences in deaths among nursing home residents with COVID-19 infection in the US. JAMA Network Open, 4(2), e2037431–e2037431.

- Hain, P. (2012). Outside in. Biteback Publishing.

- Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research, 6(2), 215–242. [CrossRef]

- Harrell, S. P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42–57. [CrossRef]

- Hayday, E. J., Collison, H., & Kohe, G. Z. (2021). Landscapes of tension, tribalism and toxicity: Configuring a spatial politics of esport communities. Leisure Studies, 40(2), 139–153.

- Huang, L., Liu, C., & Hung, K. (2024). Understanding camping tourism experiences through thematic analysis: An embodiment perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 1–24.

- Hughey, M. W., & Daniels, J. (2013a). Racist comments at online news sites: a methodological dilemma for discourse analysis. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/0163443712472089, 35(3), 332–347. [CrossRef]

- Hughey, M. W., & Daniels, J. (2013b). Racist comments at online news sites: a methodological dilemma for discourse analysis. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/0163443712472089, 35(3), 332–347. [CrossRef]

- Hylton, K. (2009). “Race” and sport : critical race theory. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Race‐and‐

108 Sport‐Critical‐Race‐Theory/Hylton/p/book/9780415436564.

- Hylton, K. (2021). Black Lives Matter in sport…? Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 40(1), 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Hylton, K., & Lawrence, S. (2016). ‘For your ears only!’Donald Sterling and backstage racism in sport. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(15), 2740–2757.

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2010). Language and the globalizing habitus of tourism: Toward a sociolinguistics of fleeting relationships. The Handbook of Language and Globalization, 255–286.

- Jones, J. M. . (1997). Prejudice and racism. 578. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Prejudice_and_Racism.html?id=xkIlAQAAIAAJ.

- Kassimeris, C., Lawrence, S., & Pipini, M. (2022). Racism in football. Soccer & Society, 23(8), 824–833.

- Kavanagh, E., Jones, I., & Sheppard-Marks, L. (2016). Towards typologies of virtual maltreatment: sport, digital cultures & dark leisure. Leisure Studies, 35(6), 783–796. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, E., Litchfield, C., & Osborne, J. (2022). Social media, digital technology and athlete abuse. In Sport, social media, and digital technology (Vol. 15, pp. 185–204). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Kearns, C., Sinclair, G., Black, J., Doidge, M., Fletcher, T., Kilvington, D., Liston, K., Lynn, T., & Rosati, P. (2023). A scoping review of research on online hate and sport. Communication & Sport, 11(2), 402–430.

- Keum, B. T. H., & Miller, M. J. (2017). Racism in digital era: Development and initial validation of the perceived online racism scale (PORS v1.0). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(3), 310–324. [CrossRef]

- Keum, B. T. H., & Miller, M. J. (2018). Racism on the internet: Conceptualization and recommendations for research. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 782–791. [CrossRef]

- Kilvington, D. (2016). British Asians, exclusion and the football industry. Routledge.

- Kilvington, D. (2020). British Asian football coaches: Exploring the barriers and advocating action in English football. In “Race”, Ethnicity and Racism in Sports Coaching (pp. 78–94). Routledge.

- Kilvington, D., Hylton, K., Long, J., & Bond, A. (2022). Investigating online football forums: a critical examination of participants’ responses to football related racism and Islamophobia. Soccer & Society, 23(8), 849–864.

- Kilvington, D., Lusted, J., & Qureshi, A. (2021). Coaching ethnically diverse participants:‘Race’, racism and anti-racist practice in community sport.

- King, A. (1997). The postmodernity of football hooliganism. British Journal of Sociology, 576–593.

- Kominers, S. D., Stanton, C., Wu, A., & Gonzalez, G. (2020). Zoom video communications: Eric Yuan’s leadership during COVID-19. Harvard Business School Case 821, 14.

- Li, J., Pearce, P. L., & Low, D. (2018). Media representation of digital-free tourism: A critical discourse analysis. Tourism Management, 69, 317–329.

- Lind, R. A. (2019). Laying a foundation for studying race, gender, class, and the media. In Race/gender/class/media (pp. 1–9). Routledge.

- Mariani, M., & Borghi, M. (2020). Environmental discourse in hotel online reviews: a big data analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 829–848.

- Massao, P. B., & Fasting, K. (2010). Race and racism: Experiences of black Norwegian athletes. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/1012690210368233, 45(2), 147–162. [CrossRef]

- Millward, P. (2008). Rivalries and racisms:‘Closed’and ‘Open’Islamophobic dispositions amongst football supporters. Sociological Research Online, 13(6), 14–30.

- Nadim, M. (2023). Making sense of hate: young {Muslims}’ understandings of online racism in {Norway}. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 49(19), 4928–4945. [CrossRef]

- Neves, S., Topa, J., Borges, J., & Silva, E. (2023). Racism in Football in Portugal: Perceptions of Multiple Actors. Social Sciences, 12(3), 165.

- Nixon, S. A. (2019). The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1637.

- Onoja, I. Ben, Bebenimibo, P., & Onoja, N. M. (2022). Critical discourse analysis of online audiences’ comments: Insights from the channels TV’s facebook audiences’ comments on farmers-herders conflicts news stories in Nigeria. SAGE Open, 12(3), 21582440221119470.

- Ortiz, S. M. (2021). Racists without racism? {From} colourblind to entitlement racism online. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(14), 2637–2657. [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, K. F., Weems, A. J., & Singer, J. N. (2020). Cyber {Racism} {Toward} {Black} {Athletes}: {A} {Critical} {Race} {Analysis} of {TexAgs}.com {Online} {Brand} {Community}. Communication \& Sport. [CrossRef]

- Parry, M. (2020). As coronavirus spreads, universities stall their research to keep human subjects safe. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 3, 18.

- Pascoe, E. A., & Richman, L. S. (2009). Perceived Discrimination and Health: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531. [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Meertens, R. W. (1995). Subtle and blatant prejudice in Western Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology, 25(1), 57–75.

- Richard, B., Sivo, S. A., Ford, R. C., Murphy, J., Boote, D. N., Witta, E., & Orlowski, M. (2021). A Guide to Conducting Online Focus Groups via Reddit. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. 20. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. C. (2017). What’s your anonymity worth? {Establishing} a marketplace for the valuation and control of individuals’ anonymity and personal data. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 19(5), 353–366. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, N. S. (2017). # FIFAputos: A Twitter textual analysis over “Puto” at the 2014 World Cup. Communication & Sport, 5(6), 712–731.

- Serrano-Durá, J., Serrano-Durá, A., & Martínez-Bello, V. E. (2019). Youth perceptions of violence against women through a sexist chant in the football stadium: An exploratory analysis. Soccer & Society, 20(2), 252–270.

- Shelby, T. (2014). Racism, moralism, and social criticism1. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 11(1), 57–74.

-

Sport England. (2024). Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/funds-and-campaigns/equality-and-diversity.

- Steinfeldt, J. A., Foltz, B. D., Kaladow, J. K., Carlson, T. N., Pagano, L. A., Benton, E., & Steinfeldt, M. C. (2010). Racism in the electronic age: Role of online forums in expressing racial attitudes about American Indians. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(3), 362–371. [CrossRef]

- Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. [CrossRef]

- TaeHyuk Keum, B., & Hearns, M. (2022). Online gaming and racism: Impact on psychological distress among Black, Asian, and Latinx emerging adults. Games and Culture, 17(3), 445–460.

- Thomas, M. B., & Wright, J. E. (2022). We can’t just shut up and play: How the NBA and WNBA are helping dismantle systemic racism. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 44(2), 143–157. [CrossRef]

- Tynes, B., Reynolds, L., & Greenfield, P. M. (2004). Adolescence, race, and ethnicity on the Internet: A comparison of discourse in monitored vs. unmonitored chat rooms. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6), 667–684.

- Vala, J., Lopes, D., & Lima, M. (2008). Black immigrants in Portugal: Luso–tropicalism and prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 64(2), 287–302.

- Van Sterkenburg, J., Peeters, R., & Van Amsterdam, N. (2019). Everyday racism and constructions of racial/ethnic difference in and through football talk. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(2), 195–212.

- Wellman, B., Quan Haase, A., Witte, J., & Hampton, K. (2001). Does the Internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? Social networks, participation, and community commitment. American Behavioral Scientist, 3, 436–455. [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, J. M., Iantaffi, A., Grey, J. A., Bockting, W. O., & Rosser, B. R. S. (2014). Recommendations for internet-based qualitative health research with hard-to-reach populations. Qualitative Health Research, 24(4), 561–574. [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. R., Lawrence, J. A., & Davis, B. A. (2019). Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 105–125.

- Winter, J., Webb, O., & Turner, R. (2024). Decolonising the curriculum: A survey of current practice in a modern UK university. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(1), 181–192.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).