Evidence before this study

To our knowledge there has been minimal evidence available to report the pharmacists’ perception on Hormone Replacement Therapy globally.

Added value of this study

The MARIE project is the first multi-work package project exploring perimenopause, menopause and post-menopause, whether this be natural, surgical or medical among cis and trans-gender population. This paper is a reflection of the WP2a-1 results linked to exploring the pharmacists’ perception on the availability and acceptability of Hormone Replacement Therapy in Low- and Middle-Income countries like Sri Lanka, Nepal, Malaysia, Ghana, Nigeria and Tanzania.

Implications of all the available evidence

This exploratory study shows gaps in knowledge, misconceptions, and access to HRT. The need for better understanding of HRT within the pharmacists community is vital as they are well placed to information to support patient’s manage perimenopause, menopause and post menopause. In high income countries such as the UK pharmacists are encouraged to provide information including directing patients to doctors that can support symptom management. Training programs to support upskilling of pharmacists can add value to LMIC healthcare systems. From a sociological perspective, whilst cultural, faith and costs can influence discussions about menopausal health in low middle income countries, empowering patients to choose their preferred treatment is vital. This can lead to creating a culture of awareness and equity to support women’s health care. This study also helps us to conduct a wider study with other health care professional in the future to better integrate menopausal care offered. |

Introduction

Hormone Replacement Therapy [HRT] is commonly utilised to manage physiological and psychological symptoms associated with perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause, whether it occurs naturally, surgically or is medically induced [

1,

2]. The decline in circulating concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone during these stages can lead to vasomotor and genitourinary symptoms and mood disturbances [

3]. HRT could alleviate these symptoms and offer benefits such as maintenance of bone mineral density and potential cardiovascular protection, particularly when initiated near the onset of menopause [

4,

5].

Women undergoing early or surgical menopause are at heightened risk for vasomotor and low-mood symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and long-term consequences such as osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline [

6]. Globally, over 70% of women experience vasomotor symptoms during menopause, with many reporting substantial impacts on sleep, mental health, work productivity, and overall quality of life. Therefore, HRT could act as a preventive strategy to mitigate these risks [

7,

8]. Clinical decision making regarding the use of HRT requires an individualised and evidence-based risk–benefit assessment [

4,

5,

9].

As the global population of women continue to rise, the demand for optimal menopausal care is expected to grow. In high-income countries (HICs), HRT is commonly prescribed as part of standard menopausal care, to improve quality of life and long-term health outcomes [

6]. However, the use of HRT is far from universal, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where its availability and acceptability remain limited due to several interconnected factors such as economic constraints [

10], inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and a lack of public awareness regarding menopausal health [

11]. The decision to use HRT is also influenced by cultural attitudes towards menopause, which may vary significantly across regions [

12]. In some societies, menopause is viewed as a natural phase of life, and women may be reluctant to seek medical treatment, particularly one that involves hormonal interventions [

13,

14]. Furthermore, the cost of medicines, which is often more prohibitive in LMICs relative to the national average earnings and due to importation taxes and limited production, can also act as a significant barrier [

15]. Moreover, following the publication of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trial, global HRT use declined sharply due to concerns about increased risks of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease. However, subsequent analyses have revealed that the risk–benefit profile is more favourable for younger women or those initiating treatment near the onset of menopause.

While the World Health Organisation has highlighted the need for affordable healthcare access for women [

16], the implementation of such recommendations remains uneven, with many countries struggling to provide comprehensive treatment options for menopausal women. In many LMICs, the absence of national clinical guidelines for menopause management, along with the exclusion of HRT from essential drug lists and weak referral systems, further limits access and appropriate use.

Enhancing menopausal health aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 3, which advocates for universal access to healthcare and the reduction of non-communicable disease burden among ageing populations.

Pharmacists, as key healthcare professionals, play a crucial role in achieving this, shaping the accessibility and acceptability of medications like HRT. Their responsibilities often extend beyond dispensing medications as they provide vital counsel to educate patients about the treatment options and collaborate with physicians to optimise therapeutic regimens, particularly in HICs such as the United Kingdom (UK) [

17]. In LMICs, pharmacists may face challenges such as limited professional autonomy, lack of menopause-focused continuing education, and gender dynamics that can hinder open discussions about menopausal symptoms with women clients. Despite the importance of pharmacists in the healthcare delivery process, there is a paucity of research data examining their views and practices on the availability and acceptability of HRT in LMIC settings. This gap highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of how pharmacists view and address the barriers linked to HRT use in LMICs. To gain initial insights, we developed a pilot study as part of a multifaceted global menopause project, MARIE[

18] to explore the perspectives of pharmacists on HRT use, cost and availability across six LMICs.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a cross-sectional study conducted as a part of the multifaceted global menopause project, MARIE (

supplementary file 01) , and is reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies (STROBE) (

Supplementary file 02) in Epidemiology guidelines for cross-sectional studies [

19].

Pharmacists working in community, public and private hospital settings in Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania were included. The study was conducted from the 1st of January to the 31st of March 2025, and participants were invited using e-posters to participate in an anonymous online survey to prevent bias.

The online survey was made available in English language. The survey was actively promoted by MARIE project Principal Investigators (PIs) based in Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Nepal, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania.

Sample Size Calculation

The below formula was used to calculate the sample size for each country.

N = population

e = margin of error (percentage in decimal form)

z = z-score* (how many standard deviations the data is from the mean)

*A 95% confidence level is a z-score of 1·96.

The number of pharmacists in Sri Lanka is steadily declining as qualified professionals migrate overseas. As of November, re-registration data from the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC) indicated that only 6,700 pharmacists were actively practising across the country [

20].

In Nigeria, although there are 21,892 registered pharmacists, only 12,807 (58·5%) were actively licensed and practicing as of 2016, based on data from the Pharmacists Council of Nigeria [

21].

Malaysia has 19,260 registered pharmacists with active practising certificates, regulated by the Pharmacy Board of Malaysia under the country’s pharmacy laws [

22].

Tanzania has 2111 pharmacists registered to practice [

23].

In Ghana, the Pharmacy Council regulates the practice of pharmacy professionals. According to recent data, there are approximately 9,000 registered pharmacists in the country, with around 7,000 reported to be in active practice [

24].

In Nepal, 4,829 pharmacists were registered with the Nepal Pharmacy Council as of March 25, 2020 [

25].

Given the varying number of active pharmacists across these countries and for the purpose of maintaining consistency and comparability across data sources, we have decided to recruit a sample size of 50 pharmacists per country, with an additional 5 participants per country to account for potential non-response or incomplete data.

Statistical Analyses

Aiming to recruit a sample of 50 pharmacists as a minimum per country across six countries yielded a sample of 331 participants. We summarised demographic and professional characteristics using frequencies (%), and compared responses across countries using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables like gender, age, educational level, location. A thematic analysis was conducted on open-ended responses from pharmacists to explore underlying perspectives and contextual factors influencing HRT use. This qualitative approach enabled the identification of recurrent patterns, attitudes, and perceived barriers across diverse healthcare settings.

Ethical Aspects

The data collection was led by the MARIE-Sri Lanka team following approval from the Ethics Review Committee at the Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Ruhuna, Galle, Sri Lanka (Reference number: 2024·07·421).

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Pharmacists

The survey collected responses from 331 pharmacists across six countries: Sri Lanka (17·5%, n = 58), Tanzania (16·9%, n = 56), Malaysia (15·4%, n = 51), Ghana (18·4%, n = 61), Nigeria (15·1%, n = 50), and Nepal (16·6%, n = 55). A total of 49% (n=162) of the pharmacists were aged between 26 and 35 years, and 50·8% (n=168) were female.

Among the respondents, 41·7% (n = 138) worked in private community pharmacies (Sri Lanka (23·1%, n = 32), Tanzania (15·9%, n = 22), Malaysia (8·7%, n = 12), Ghana (29%, n = 40), Nigeria (13·8%, n = 19), and Nepal (9·4%, n = 13)), 32·6% (n = 108) worked in government hospitals (Sri Lanka (13·8%, n = 15), Tanzania (14·8%, n = 16), Malaysia (34·2%, n = 37), Ghana (3·7%, n = 4), Nigeria (21·3%, n = 23), and Nepal (12%, n = 13)) and 16·6% (n = 55) were employed in private hospitals (Sri Lanka (3·6%, n = 2), Tanzania (14·5%, n = 8), Malaysia (3·6%, n = 2), Ghana (21·8%, n = 12), Nigeria (7·3%, n = 4), and Nepal (49·1%, n = 27)). A smaller proportion of respondents worked in government community pharmacies (3·9%, n = 13) or in other sectors like clinical pharmacy and regulatory pharmacy (5·1%, n = 17). There was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of pharmacists’ positions across professional groups by country (χ² = 141·3, p < 0·0001).

Among the respondents, 35% (n=116) held a Bachelor of Pharmacy (BPharm) degree, while 23% (n=76) had a Bachelor of Science in Pharmacy (BSc in Pharmacy). Additionally, 13·6% (n=45) held a Certificate of Proficiency or Efficiency, and 13·3% (n=44) had a Higher National Diploma. The remaining respondents held postgraduate qualifications, including Master of Pharmacy (MPharm) (8·8%, n=29), Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) (2·1%, n=7), Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) (1·2%, n=4), Master of Philosophy (MPhil) (0·9%, n=3), and other degrees (2·1%, n=7). There was statistically significant heterogeneity in the distribution of the highest educational qualifications across countries (χ² = 371·5, p < 0·0001).

Most of the pharmacies (57·4%, n = 190) were based in urban areas, while 32·9% (n = 109) were in semi-urban areas, and 9·7% (n = 32) were in rural areas. There was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of pharmacy locations by level of urbanisation (urban, semi-urban and rural) across countries (χ² = 24·43, p = 0·0065).

Socio-demographic characteristics of pharmacists are presented in

Table 1.

Pharmacists’ Awareness and Availability of HRT for Dispensing

Among the total respondents, 91·5% (n = 303) of pharmacists were aware that HRT is prescribed for perimenopausal, menopausal, and postmenopausal women. There was statistically no significant difference between countries in terms of their awareness (χ² = 9·246, p = 0·0996). Although 91·5% of surveyed pharmacists reported being aware of HRT, further analysis of their responses revealed notable misconceptions regarding its definition and application. Specifically, some respondents identified oral contraceptives as forms of HRT in all the countries, reflecting a misunderstanding of the distinct therapeutic indications and hormonal compositions of these treatments. Furthermore, explanations provided by pharmacists for patients' reluctance to initiate HRT included reasons such as “consuming emergency contraceptive pills”, “misconceptions about family planning prevent them from accessing these services” and “not being with their husbands or having no intention of further childbearing, hence perceiving no need for HRT” as noted in Ghana.

Among all respondents, 68·9% (n = 228) of pharmacists reported that HRTs were available for dispensing in their respective countries. The highest proportion was reported in Nepal (92·7%, n = 51), while the lowest was in Nigeria (42%, n = 21). There was a statistically significant difference among countries regarding the availability of HRTs for dispensing (χ² = 56·77, p < 0·0001).

The most commonly available HRTs reported by pharmacists included Estradot (estradiol), Femoston (estradiol and dydrogesterone), Progynova (estradiol valerate), Tibolone, Depo-Provera (medroxyprogesterone acetate), Angeliq (drospirenone and estradiol), Provera (medroxyprogesterone acetate), Lenzetto (estradiol), Combi-Patch (estradiol and norethindrone), Evorel (estradiol and norethisterone), Duphaston (dydrogesterone), Duavee (estrogens and bazedoxifene), Prometrium (micronized progesterone), and Premarin vaginal cream (conjugated estrogens). Additionally, perimenopausal women were also using intrauterine devices such as Mirena (levonorgestrel) and Eloira (levonorgestrel). Depo-Provera was available for all six countries. The HRTs reported as available across the countries are presented in

Table 2.

In Sri Lanka, the majority of pharmacists (72·4%, n=42) incorrectly identified oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) or emergency contraceptive pills as HRTs. Similarly, some pharmacists in other countries also mistakenly identified OCPs or emergency contraceptive pills as HRTs, including Tanzania (16·0%, n=9), Malaysia (9·8%, n=5), Ghana (13·1%, n=8), Nigeria (10%, n=5), and Nepal (7·8%, n=4).

HRT Pricing Variations Across Countries

HRT pricing varied significantly across the countries. In Sri Lanka, the Mirena coil was the most expensive HRT at US$101, followed by Depo-Provera at US$25. In contrast, Malaysia offered the most affordable options, with Progynova priced as low as US$0·20, followed by Provera (US$6), Premarin (US$18), Angeliq and Depo-Provera (each at US$22), and Tibolone (US$25). Nepal displayed a moderate pricing structure, with the Mirena coil available at US$36, Femoston Mono at US$22, and Premarin at US$5·50. Nigeria reported relatively lower prices for some products, such as Depo-Provera at US$3 and Progynova at US$25, though vaginal oestrogen was higher at US$38. Tanzania reported the highest prices for certain products, including Lenzetto at US$122 and Depo-Provera at US$120, while Angeliq and vaginal oestrogen were priced at US$19 and US$60, respectively. Ghana’s prices fell in the mid-to-high range, with Depo-Provera at US$65, Provera at US$40, Progynova at US$10, vaginal oestrogen at US$20, and Tibolone at US$20.

HRT Dosages Across Countries

Sri Lankan pharmacists have reported only the doses of Depo-Provera (150 mg) and Femoston (1mg and 2mg).

In Tanzania, Depo-Provera was reported in 75 mg to 150 mg doses. Duavee (conjugated oestrogen) was available in 0·625 mg and 1·25 mg strengths. Vaginal cream was dispensed in amounts of 1–2 g. Other formulations included Evorel 25 mcg, Mirena coil (levonorgestrel) 150 mg, and Duphaston 10 mg.

Malaysian pharmacists reported Premarin was available in a 0·625 mg dose. Depo-Provera came in a 150 mg dosage. Provera was available in dosages ranging from 5 mg to 10 mg. Progynova was offered in doses of 1 mg to 2 mg. Prometrium was available in a 100 mg dose. Estradiol was available in a 1 mg dose, while Dydrogesterone was offered in a 10 mg dose. Evorel came in dosages ranging from 1 mg to 2 mg. Lastly, Femoston-Conti combined 1 mg of estradiol and 5 mg of dydrogesterone.

In Ghana, Depo-Provera was available in a 150 mg dosage. Progynova was offered in doses ranging from 1 mg to 2 mg. Estriol vaginal cream (Ovestin) was available in a 500 mcg dosage. Provera was available in a 5 mg dose. Cyclogest pessaries were offered in dosages of 200 mg to 400 mg. Vaginal estrogen tablets were available at 10 mcg per tablet. Tibolone tablets came in a 2·5 mg dose. Vaginal creams were available in concentrations of 0·1% and 0·01%. Estradot transdermal patches were offered in dosages of 25 mcg, 50 mcg, 75 mcg, and 100 mcg. Estradot spray was available at 1.53 mg per spray. Evorel transdermal patches were available in dosages of 25 mcg, 50 mcg, 75 mcg, and 100 mcg. Femoston Mono tablets were available in dosages of 1 mg and 2 mg. Estradot gel was offered in 0·5 mg, 1 mg, and 1·5 mg dosages.

Provera was available in dosages of 2·5 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg in Nigeria Duphaston was available in a 10 mg dosage. Progynova was offered in doses of 1 mg, 2 mg, and 10 mg. Levofem, which contains 0.15 mg of Levonorgestrel and 0·03 mg of Ethinylestradiol, was available with ferrous. Duavee was available in a 500mcg dose. Depo-Provera was available in a 150 mg dosage. Testosterone was available in a 100 mg dose. Premarin (Conjugated Estrogen) tablets were available in dosages of 0·3 mg, 0·625 mg, 0·9 mg, and 1·25 mg. Premarin vaginal cream was available at a concentration of 0·625 mg per gram, and Premarin estrogen cream was available in a 0.625 mg dose.

Nepal reported Premarin estrogen cream was available in a 0·625 mg dose. Estradot was offered in dosages of 1 mg and 2 mg, and conjugated estrogen was available at 0·625 mg. Eloira IUD, which contains 20 mcg of levonorgestrel, and Mirena coil with 20 mcg of levonorgestrel were available. Susten was offered in 100 mg and 200 mg dosages. Edil was available in 1 mg and 2 mg doses. Ovral L, Ovral G, Loette, Premarin, and Dydrogesterone (2 mg) were available. Delivery was available in a 10 mg dose. Conjugated estrogen tablets were offered in dosages of 0·625 mg and 0·3125 mg. Estradiol vaginal cream was available at a concentration of 0·01%. Estradiol (2 mg) and Dydrogesterone (10 mg) were available together. Depo-Provera was available in 50 mg, 100 mg, and 150 mg dosages. Testosterone was available in dosages ranging from 0·03 mg to 1·5 mg. Duphaston was available in a 10 mg dose. Gestofit and Estroflav capsules were available in dosages of 100 mg and 200 mg. And also, Femoston Mono tablets were available in dosages ranging from 1 mg to 10 mg.

Pharmacists View on Level of Awareness of HRT Among the Patients

According to pharmacists across all six countries, the level of awareness and understanding of HRT among patients was very low, with 88·8% reporting limited knowledge. Among them, view of the Nepal pharmacists showed the highest awareness and understanding of HRT among patients (20 %) (

Table 3). However, there was no significant difference between countries in terms of patients’ level of awareness regarding HRT (χ² = 9·96, p = 0·0763).

The majority of pharmacists (57·1%) expressed willingness to discuss HRT with perimenopausal, menopausal, and postmenopausal women. Among the total, 67·4% of pharmacists believed that alternative non-pharmacological treatments can help manage menopausal symptoms.

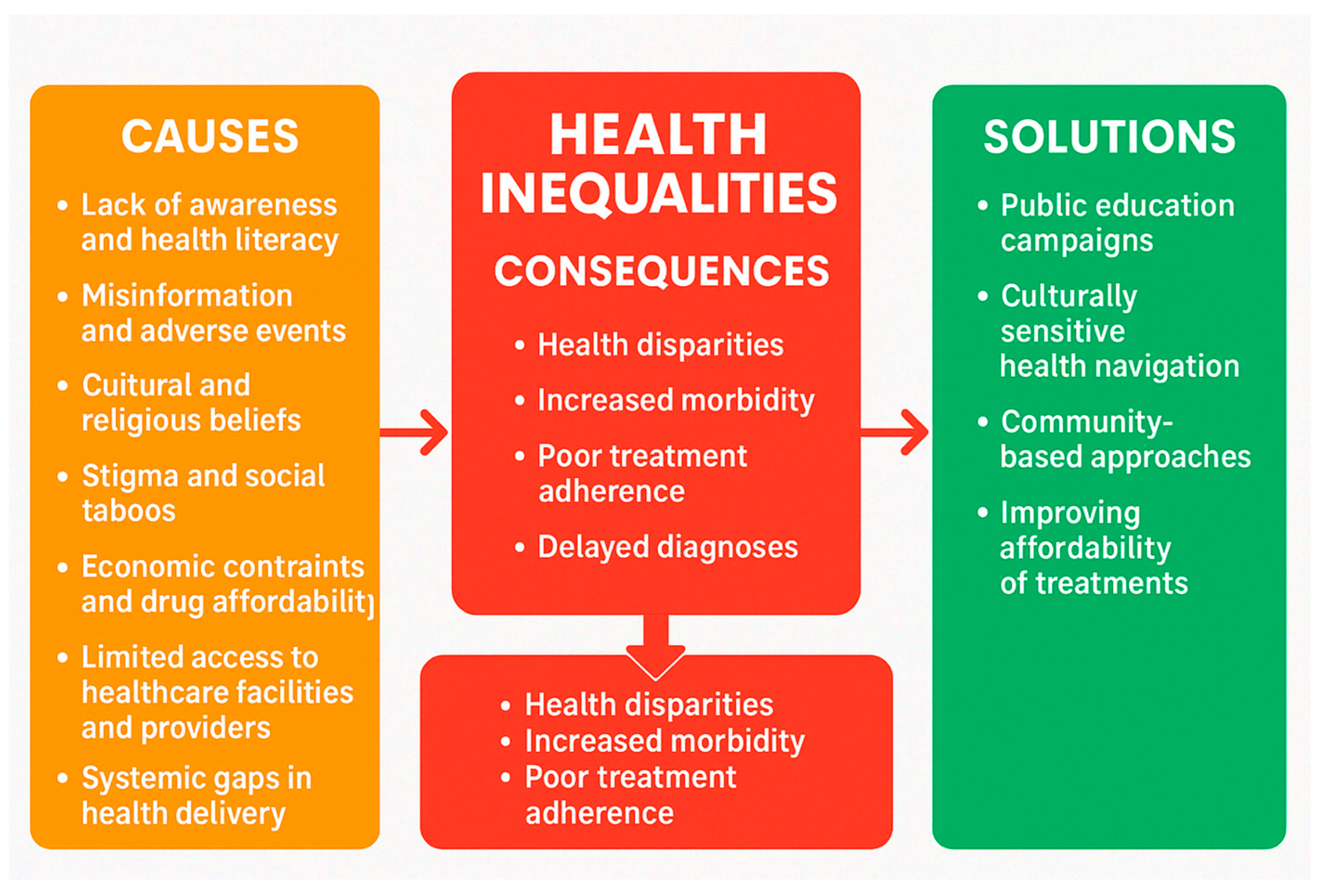

For the question, “In your experience, what are the main challenges or barriers that prevent women in underserved communities from accessing HRT?” pharmacists from Nepal, Nigeria, Ghana, Malaysia, Tanzania, and Sri Lanka consistently identified a range of socio-cultural, educational, economic, and healthcare system-related barriers that hamper women in underserved communities from accessing HRT.

The following key themes emerged from the responses of the pharmacists.

Lack of Awareness and Health Literacy

A prominent barrier reported across all countries was the limited awareness and understanding of menopause and HRT. According to the respondent pharmacists, many women in these countries are unaware of the availability of HRT or do not recognise menopause-related symptoms as conditions that warrant medical attention. This is compounded by low levels of general and health-specific literacy, particularly in rural or illiterate populations.

“They are miscommunicated & mislead by some of the people in our society who are less in education in medical field but educated in English or some other field” (Sri Lanka)

“Lack of knowledge about the menopause and the risks and benefits of HRT by women” (Malaysia)

“Unawareness on pre/post-menopausal issues that require clinical advice” (Malaysia)

“They lack the general knowledge on the use of Hormone Replacement Therapy and its health benefits during the menopausal and post-menopausal phase” (Ghana)

“Women think them self those type medicines are like otc medication” (Nigeria)

Economic Constraints and Drug Affordability

From a public health standpoint, economic barriers represent a critical impediment to equitable access to HRT. In contexts characterised by high out-of-pocket health expenditure and limited insurance coverage, the cost of HRT can be prohibitive, disproportionately affecting low-income populations. Financial insecurity, exacerbated by broader socioeconomic inequities, limits women's ability to initiate and sustain treatment, even when HRT is technically available. Clinically, this translates into suboptimal management of menopausal symptoms, increased risk of untreated comorbidities, and avoidable deterioration in quality of life. Pharmacists and frontline providers consistently report that cost considerations often override clinical need in treatment decisions, indicating a misalignment between therapeutic availability and accessibility. These findings underscore the necessity of integrating affordability-focused interventions such as subsidy programs, inclusion of HRT in essential medicines lists, and expanded insurance coverage into public health strategies aimed at improving menopausal care.

“Payment required is higher than what they can afford” (Tanzania)

Cultural and Religious Beliefs

Cultural norms and religious doctrines constitute significant sociocultural determinants influencing healthcare-seeking behaviours, particularly in the context of menopause and HRT. According to the perception of pharmacists, from settings such as Nigeria and Tanzania suggest that deeply embedded patriarchal structures and gendered expectations frequently constrain women's autonomy in making informed health decisions. According to them, religious interpretations may further stigmatise discussions around menopause or the use of pharmacological interventions such as HRT, framing them as unnatural or morally inappropriate. In many instances, male family members exert substantial influence either explicitly or implicitly over whether women are permitted to access treatment, thereby reinforcing structural barriers to care. These dynamics underscore the critical need for culturally sensitive, gender-transformative approaches that address power asymmetries and promote equitable health decision-making.

“Men do not allow woman to use HRT” (Tanzania)

Stigma and Social Taboos

The stigmatisation of menopause and discomfort in discussing reproductive health issues were highlighted, particularly in Nepal, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. Many women feel embarrassed to disclose symptoms or seek advice, resulting in silence and neglect of treatment options.

“In Sri Lanka, women are shy to discuss about HRT” (Sri Lanka)

“Readiness to be treated is still low” (Tanzania)

“Most perceived menopause as a normal stage in womanhood. everyone will experience it” (Malaysia)

“Some women felt embarrassing to discuss this issue or some do not know who to seek for advice” (Malaysia)

Limited Access to Healthcare Facilities and Providers and Availability

Access to healthcare infrastructure, including specialists knowledgeable in managing menopause, is limited in many underserved settings. Geographic barriers such as long distances to clinics, inadequate transportation, and long wait times further impede access. In Ghana and Tanzania, for instance, HRT is reportedly only available in tertiary-level or urban healthcare centres.

“Pharmacists are not available in most community pharmacies and patients don’t get proper instructions” (Sri Lanka)

“Such drugs are available in big health facility” (Tanzania)

“Distance between the community and the pharmacy shop” (Ghana)

“Poor healthcare access makes it difficult to receive proper prescriptions and follow-up care” (Ghana)

“It's not even available here” (Nigeria)

“Gynaecology clinics are not functioning in most Government hospitals” (Sri Lanka)

Systemic Gaps in Healthcare Delivery

Pharmacists from several countries noted systemic issues such as under-prescribing of HRT due to a lack of trained professionals, especially in primary care. Poor communication between healthcare providers and patients was also mentioned as a contributing factor.

“HRT only available in Hospital Formulary & categorised as A class drug according to MOH Formulary which can be started by Gyn and Obs specialist only” (Malaysia)

“There are few specialized physicians in these areas and hence the issue has been under prescribing even in the face of high prevalence of menopause-related symptoms” (Ghana)

Out of those themes ‘Lack of Awareness and Health Literacy’, ‘Economic Constraints and Drug Affordability’ and ‘Limited Access to Healthcare Facilities and Providers and availability’ (

Figure 1) were the most commonly mentioned barriers and challenges by pharmacists from different countries (

Table 4).

For the question, “What resources, training, or support would help you better advise and provide HRT to underserved populations in your practice?” pharmacists from six diverse countries, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Malaysia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Nepal, identified several strategic areas for strengthening their ability to support and counsel women in underserved communities regarding HRT. Their responses revealed common themes across educational, infrastructural, financial, and regulatory domains as follows:

Training and Professional Development

A predominant recommendation was the need for specialised training in menopause management and HRT, particularly tailored to pharmacists and pharmacy staff:

“Wanted to trained all staff in a pharmacy about HRT, some of pharmacy staff have no any ideas about HRT, even they don't know what the meaning for HRT is, my idea is that Pharmacists must be in their position and want to do counselling to each patient” (Sri Lanka)

Calls for continuing professional development (CPD), seminars, certification courses, and workshops were recurrent. In-service education on counselling techniques, non-HRT alternatives, and clinical updates on HRT were emphasised. The training of all pharmacy personnel, including support staff, was deemed essential to ensure consistent and informed patient advice. Pharmacists also suggested the incorporation of tele-education, webinars, and online CME modules to facilitate widespread access to up-to-date knowledge.

Community and Patient Education

Pharmacists strongly advocated for improved public awareness by way of patient friendly educational materials such as pamphlets, posters, and flyers, preferably in local languages. Use of mass media platforms including TV, radio, and social media to disseminate accurate information about menopause and HRT. Recommendations included public awareness campaigns, home visits, health talks, and community outreach programs to demystify HRT and reduce stigma.

Availability and Accessibility of HRT

Improving product availability and affordability was highlighted as a critical area. Pharmacists requested regulation of HRT pricing, subsidies (e.g., NHIS in Ghana), and provision of free or low-cost medication for women in need. They emphasised to ensure consistent supply of HRT, especially in rural or government healthcare facilities where current stock is often inadequate. Suggestions also included providing free samples and incentivising pharmacies to support HRT services.

“HRT needy parents are mostly over 50 retired or above to retire they not having proper revenue to by their essentials” (Sri Lanka)

Supportive Infrastructure and Collaboration

Recommendations extended to broader health system support include standardised prescribing and counselling guidelines specific to HRT. Collaborative training with other healthcare providers, particularly reproductive and primary care providers. Trained teams or HRT champions in each community or ward should be formed to act as a local point of care and advice. Development of data tracking systems to monitor uptake, adherence, and outcomes of HRT among underserved populations.

Government and Policy-Level Interventions

Pharmacists advocated for systematic government involvement to create sustainable support for HRT delivery. Government-sponsored awareness and training campaigns, including those run by Ministries of Health (e.g., Ministry of Health clinics in Sri Lanka and Nepal). Integration of menopause care into primary healthcare and maternal health programs. Establishment of national guidelines and regulatory frameworks for HRT counselling, prescription, and dispensation. Out of those support suggested ‘Training and Professional Development’, ‘Community and Patient Education Resources’ were the most commonly suggested support by pharmacists from different countries (

Table 5).

Discussion

Although pharmacists play a critical role in healthcare systems, especially in LMICs, limited research has explored their perspectives and practices regarding the accessibility and acceptability of HRT. This lack of evidence underscores the importance of understanding how pharmacists perceive and manage the challenges associated with HRT use in these settings. To begin addressing this gap, we conducted a pilot study aimed at investigating pharmacists’ views on HRT usage, affordability, and availability across six LMICs. The demographic and professional profile of the respondents provides important context for interpreting the findings of this multi-country study. With participation from 331 pharmacists across six LMICs, including Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Malaysia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Nepal, the survey achieved balanced geographic representation with a minimum of 50 respondents per country. The majority of pharmacists were between 26 and 35 years of age, and gender distribution was nearly equal, indicating a relatively young and gender-balanced workforce. A significant proportion were employed in private community pharmacies (41·7%), with others working in government hospitals (32·6%) and private hospitals (16·6%). More than half of the pharmacists held a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy (58%), while a smaller proportion had postgraduate qualifications (13%), suggesting a moderate level of academic advancement. The majority of pharmacies (57·4%, n = 190) were located in urban areas, followed by 32·9% (n = 109) situated in semi-urban settings.

Although a high proportion of pharmacists (91·5%) reported awareness that HRT is prescribed for perimenopausal, menopausal, and postmenopausal women, qualitative responses revealed notable gaps in understanding. The findings reveal a concerning gap in pharmacists' knowledge regarding HRT, particularly in Sri Lanka, where a majority (72·4%) incorrectly identified OCPs or emergency contraceptive pills as HRTs. This misconception was also observed, albeit to a lesser extent, among pharmacists in several other countries, including Tanzania, Malaysia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Nepal. This conflation highlights a superficial level of awareness, where general recognition of HRT exists, but detailed knowledge about its specific indications, mechanisms, and appropriate use remains limited. These responses suggest a conflation between HRT and family planning methods, raising concerns about the depth and accuracy of pharmacists' knowledge regarding the role of HRT in managing menopausal symptoms rather than fertility regulation. Such findings underscore the need for targeted educational interventions to address gaps in understanding among pharmacy professionals, particularly in distinguishing HRT from contraceptive therapies. Availability of HRTs varied significantly across the surveyed countries, with 68·9% of pharmacists overall reporting that these therapies were accessible for dispensing. Nepal reported the highest availability (92·7%), indicating a well-established supply or demand for HRT in the country. In contrast, Nigeria had the lowest reported availability (42%), suggesting potential challenges in access, supply chain logistics, regulatory approvals, or demand for menopausal care. The reported availability of HRT among pharmacists suggests access to a range of commonly prescribed formulations. Products such as Estradot, Femoston, Progynova, Tibolone, Angeliq, and Provera reflect a mix of estrogen-only and combined estrogen-progestogen therapies, catering to diverse patient needs.

Therefore, this study offers a unique multi-country perspective on the availability and accessibility of HRT in LMICs viewed through the lens of practicing pharmacists. As frontline healthcare providers and readily accessible medication counsellors, pharmacists play a crucial role in guiding menopausal women toward appropriate therapeutic options. The findings highlight significant gaps influenced by pharmacists’ knowledge, infrastructural limitations, and socio-cultural factors, which collectively hinder the optimal use of HRT among underserved populations. And also, the findings indicated that pharmacists in Sri Lanka possess the poorest knowledge regarding available HRT dosing protocols, suggesting that HRT is not a commonly dispensed medication in the Sri Lankan healthcare setting.

By investigating the factors that influence pharmacists’ perceptions and practices related to HRT, this research provides valuable insights for policymakers, healthcare providers, and advocates seeking to improve menopausal care in these regions. Ultimately, the findings can inform strategies to enhance the accessibility, affordability, and acceptability of HRT, thereby improving the health and well-being of women in LMICs.

Given their proximity to both patients and the healthcare system, pharmacists offer critical insights into the barriers and facilitators surrounding HRT use. These include logistical challenges such as inconsistent supply chains, regulatory hurdles, and limited availability of therapeutic alternatives. Furthermore, pharmacists' understanding of HRT’s benefits and risks, their training, and attitudes toward menopause care directly influence patient acceptance and adherence to treatment.

Barriers to HRT access identified in this study are consistent with broader determinants of health inequity in LMICs-such as economic constraints, medication shortages, and poor access to specialized care. Due to the high prices of these HRTs compared to the other medicines, people in some of the countries cannot afford theses and those are not readily available in the pharmacies as well. In our study it clearly showed that HRT pricing varied significantly across the countries. In Sri Lanka, the Mirena coil was the most expensive HRT at US$101, followed by Depo-Provera at US$25. In contrast, Malaysia offered the most affordable options, with Progynova priced as low as US$0·20. That is a common issue for most of the countries that we studied. In addition, socio-cultural factors including stigma, religious beliefs, patriarchal decision-making, and embarrassment in discussing menopausal symptoms further restrict women’s willingness or ability to seek care. These findings echo the World Health Organization’s call for culturally sensitive, gender-responsive health systems that deliver comprehensive care throughout a woman’s lifespan.

Encouragingly, pharmacists across all six countries expressed a strong willingness to play a more active role in HRT counselling, provided they receive appropriate support. The need for continuing professional development (CPD), access to updated clinical guidelines, multilingual patient education resources, and broader public health campaigns was consistently emphasized. Moreover, pharmacists underscored the importance of integrating HRT education into wider community health initiatives via media, seminars, and digital platforms-demonstrating the potential for scalable, low-cost interventions that could improve menopause care across diverse LMIC settings.

Importantly, this study sheds light on the structural barriers to HRT implementation. In several settings, pharmacists noted the lack of HRT availability in public-sector formularies and the concentration of services in urban or tertiary facilities. Additionally, some reported that even when HRT was available, affordability remained a major obstacle for postmenopausal women, many of whom are financially dependent or uninsured. Addressing these systemic issues requires multi-sectoral coordination involving national health authorities, pharmaceutical suppliers, and local health facilities.

This is the first study conducted to explore the availability and acceptability of HRT among pharmacists. A qualitative study conducted by Barber and Charles (2023) among menopausal women, general practitioners, and gynecologists in United Kingdom revealed similar qualitative themes. Among women, perceptions of HRT were largely influenced by beliefs about the risk of breast cancer. General practitioners (GPs) demonstrated a lack of knowledge regarding HRT, alternative treatment options, and the broader health benefits-similar to the gaps identified among pharmacists in the present study [

26]. Similarly, Yeganeh et al. (2017) reported knowledge barriers among healthcare practitioners regarding HRT, which are consistent with the knowledge gaps observed among pharmacists in the present study [

27]. Furthermore, a recent Swedish study found that only 41·9% of general practitioners demonstrated adequate awareness of HRT [

28]. Similar to the present study, where 91.5% of pharmacists were aware of HRT, a study conducted by Elmahjoubi et al. (2021) reported that 87% of pharmacists had awareness regarding HRT [

29].

Women in these six LMICs have fewer HRT options available for managing menopausal symptoms compared to women in high-income countries such as Sweden and the UK, which had 47 and 67 HRT products available, respectively, as of 2004 [

30].

The insights derived from this cross-sectional study contribute to the limited but growing body of evidence on menopausal care in LMICs. They highlight the under-recognised yet critical role of pharmacists in bridging knowledge gaps and improving access to evidence-based therapies. Training pharmacists to provide accurate, empathetic, and culturally appropriate menopause counseling may serve as a cost-effective strategy to expand HRT reach and uptake in resource-constrained environments.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of six LMICs has provided us valuable insights to conduct a much wider study to better evaluate perceptions and practices among pharmacists, and potentially across other healthcare professionals, where evidence-based-policies and guidelines can be put in place, that is useful for these regions. While acknowledging the strengths of this study, several limitations should be considered. The data were collected through an online survey, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalisability of the findings. The study was conducted among pharmacists from only six LMICs, with a minimum of 50 participants per country. As such, the sample may not be representative of the broader pharmacist population across all LMICs. Furthermore, the findings are based on self-reported data regarding participants' awareness and knowledge, which may not accurately reflect their actual competencies or practices. Social desirability bias and misreporting cannot be ruled out.

Recommendations

To address the identified gaps in knowledge, misconceptions, and access to HRT, several targeted strategies are recommended. First, incorporating updated and evidence-based content on menopause and HRT into pharmacy education and ongoing professional development programs is essential. This will help ensure pharmacists are equipped with accurate knowledge about the indications, formulations, and dosing of HRT. Second, public health authorities should implement awareness campaigns to clarify widespread misconceptions, particularly the confusion between HRT and contraceptives, which were notably prevalent in some regions. These campaigns should aim to educate both healthcare providers and the general public. Third, to improve access and reduce disparities in availability and cost, governments and healthcare systems should explore ways to regulate HRT pricing and consider subsidy mechanisms to make essential therapies more affordable. Finally, establishing standardized, country-specific guidelines for pharmacists on HRT use can promote consistent counselling and dispensing practices. Together, these recommendations support safer, more equitable, and better-informed use of HRT in diverse healthcare settings.

Conclusion

Pharmacists across the six surveyed countries generally demonstrated a high level of awareness that HRT is intended for use among menopausal women. However, this awareness did not always translate into accurate knowledge, as significant misconceptions were identified, most notably in Sri Lanka, where a majority confused HRT with oral contraceptives or emergency pills. Similar misunderstandings were observed in other countries, pointing to widespread confusion regarding HRT's true purpose, indications, and components. Availability of HRT also varied considerably, with some countries having broad access and others facing limitations. While certain formulations like Depo-Provera were commonly available, the range and consistency of other HRT options differed. Pricing disparities further complicated access, with some countries offering affordable therapies while others presented prohibitively high costs for common products. Furthermore, knowledge about HRT dosages and formulations was inconsistent. In some regions, particularly Sri Lanka, pharmacists showed limited familiarity with dosage variations, while others, like Ghana and Malaysia, exhibited a broader understanding, likely due to better exposure or training.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Availability of data and material

The principal investigators and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon a reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and conceptualised this paper. VP collected data from Sri Lanka, OK from Nepal, THT from Malaysia, GE from Nigeria, FT and NM from Ghana, and BM from Tanzania. VP analysed the data and wrote the first draft, which was furthered by all other authors. All authors critically appraised, reviewed, and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval

Approved. Obtained from the Ethics Review Committee at the Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, University of Ruhuna, Galle, Sri Lanka (Reference number: 2024.07.421).

Consent to participate

Obtained.

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

MARIE Consortium: Aini Hanan binti Azmi, Alyani binti Mohamad Mohsin, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Artini binti Abidin, Ayyuba Rabiu, Chijioke Chimbo, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Jean Pierre Gafaranga, Emmanuel Habimana, Choon-Moy Ho, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Damayanthi Dasanayaka, Diana Suk-Chin Law, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Donatella Fontana, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Farhawa binti Zamri, Fatin Imtithal binti Adnan, Geok-Sim Lim, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Jinn-Yinn Phang, John Yen-Sing Lee, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Juhaida binti Jaafar, Karen Christelle, , Kathryn Elliot, Kim-Yen Lee, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Lee-Leong Wong, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Min-Huang Ngu, Nicholas Panay, Noorhazliza binti Abdul Patah, Nor Fareshah binti Mohd Nasir, Norhazura binti Hamdan, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Nurfauzani binti Ibrahim, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Pooja Lama, Pradeep Mitra, Prasanna Herath, Puong-Rui Lau, Rakshya Parajuli, Rakesh Swarnakar, Ramya Palanisamy, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Safilah Binti Dahian, Sapana Amatya, Sing-Yew Ting, Siti Nurul Aiman, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Vaitheswariy Rao, Xin-Sheng Wong, Xiu-Sing Wong, Yee-Theng Lau, Jeevan Dhanarisi, Nana Mintah-Afful, Ganesh Dangal, Carol Atkinson, Lamiya Al-Kharusi, Kathryn Elliot, Julie Taylor, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Chukwuemeka Chidindu Njoku, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Onyebuchi Lynda Ngozi, Nnenna Josephine Egbonnaji, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Catherine Larko Narh Menka, Kwasi Eba Polley, Isaac Lartey Narh, Bernard B. Borteih.

References

- Paciuc, J. Hormone therapy in menopause. Hormonal Pathology of the Uterus 2020, 89–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Hawton, K.; Blake, F. Psychological and sexual symptoms associated with the menopause and the effects of hormone replacement therapy. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1995, 167, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, S.; Husband, C.; O'donnell, M.; Barwin, B.; Woodend, A. Estrogen-related mood disorders: reproductive life cycle factors. Advances in Nursing Science 2005, 28, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, C.J.; Mehta, J.M.; Manson, J.E. Management of menopausal symptoms: a review. Jama 2023, 329, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, R.; Hodis, H.; Lobo, R.; Allison, M. Hormone replacement therapy–where are we now? Climacteric 2021, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochocka, M.; Karska, J.; Pszczołowska, M.; Ochnik, M.; Fułek, M.; Fułek, K.; Kurpas, D.; Chojdak-Łukasiewicz, J.; Rosner-Tenerowicz, A.; Leszek, J. Cognitive decline in early and premature menopause. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.D.; Sarrel, P.M.; Nelson, L.M. Hormone replacement therapy in young women with primary ovarian insufficiency and early menopause. Fertility and sterility 2016, 106, 1588–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, O.C.; Manyonda, I. The surgical menopause. Best practice & research clinical obstetrics & gynaecology 2022, 81, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Manchanda, R.; Gaba, F.; Talaulikar, V.; Pundir, J.; Gessler, S.; Davies, M.; Menon, U.; Obstetricians, R.C.o. Gynaecologists. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and the use of hormone replacement therapy below the age of natural menopause: scientific impact paper No. 66. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2022, 129, e16–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanerolle, G.; Ghosh, S.; Briggs, P.; Phiri, P.; Taylor, J.; Pathiraja, V.; Mudalige, T.; Bouchareb, Y.; Cavalini, H.; Hinchliff, S. A Perspective on Economic Barriers and Disparities to Access Hormone Replacement Therapy in Low and Middle-Income Countries (MARIE-WP2d). 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jaff, N. Does one size fit all? The usefulness of menopause education across low and middle income countries. Maturitas 2023, 173, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Davis, G.; Singer, A.; King, D.D.; Mattle, L. Understanding attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors surrounding menopause transition: results from three surveys. Patient related outcome measures 2022, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, G.D.; Graham, S.; Clerinx, C.; Bernick, B.A.; Krassan, M.; Mirkin, S.; Currie, H. Behaviours and attitudes influencing treatment decisions for menopausal symptoms in five European countries. Post Reproductive Health 2016, 22, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, S.; Singh, S. Menopausal Hormone Therapy: Current Review and its Acceptability and Challenges in the Indian Context. Journal of the Epidemiology Foundation of India 2025, 3, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, A.H.; Ekman, B.; Dimarco, M.; Sundewall, J. The cost-effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health and rights interventions in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 2021, 29, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Access to health care. 2022.

- NHSBSA. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) - England. Available online: https://nhsbsa-opendata.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/hrt/hrt-background-methodology-v002.html#:~:text=Pharmacists%20in%20the%20UK%20can,patient%20counts%20for%20the%20product (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Delanerolle, G.; Forbes, A.K.; Cavalini, H.; Taylor, J.; Riach, K.; Hinchcliff, S.; Atkinson, C.; Potočnik, K.; Briggs, P.; Kurmi, O. An Exploration of the Mental Health Impact Among Menopausal Women: The MARIE Project Protocol (UK arm). American Journal of Biomedical Science & Research 2024, 22, AJBSR. MS. ID. 002992. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayammanne, D. Many pharmacies face closure Ceylon Today 2024.

- Ekpenyong, A.; Udoh, A.; Kpokiri, E.; Bates, I. An analysis of pharmacy workforce capacity in Nigeria. Journal of pharmaceutical policy and practice 2018, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, L.C.; Yee, C.S. The paradigm shift of pharmacy profession at post-COVID-19 era in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Pharmacy (MJP) 2022, 8, iii-v. [Google Scholar]

- Salaam, D.e. Tanzania: Pharmacy Council Membership Up By Over 10pc. Tanzania Daily News 2020.

- Koduah, A.; Sekyi-Brown, R.; Kretchy, I. The evolution of pharmacy practice regulation in Ghana, 1892-2013. Pharmaceutical Historian 2020, 50, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, R.; Palaian, S.; Sapkota, B.; Shrestha, S.; Khatiwada, A.P.; Shankar, P.R. A nationwide exploratory survey assessing perception, practice, and barriers toward pharmaceutical care provision among hospital pharmacists in Nepal. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 16590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, K.; Charles, A. Barriers to accessing effective treatment and support for menopausal symptoms: a qualitative study capturing the behaviours, beliefs and experiences of key stakeholders. Patient preference and adherence 2023, 2971–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeganeh, L.; Boyle, J.; Teede, H.; Vincent, A. Knowledge and attitudes of health professionals regarding menopausal hormone therapies. Climacteric 2017, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, R.G.; Skalkidou, A.; Cruz, N.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Iliadis, S.I. Swedish physicians' knowledge of and prescribing practices for menopausal hormone therapy: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Maturitas 2025, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmahjoubi, E.; Rghebi, N.; Atia, W.B.; Yamane, M. Are there Opportunities for a Specialist Menopause Pharmacist in Libya? AlQalam Journal of Medical and Applied Sciences 2021, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.E.; Lalonde, A.B.; Fortin, C.; Lea, R.; Azzarello, D. Availability of hormone replacement therapy products in Canada. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada 2004, 26, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).