Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks Distinguishing Gamification and DGBL in Education and Health Promotion

2.2. Design Principles for Effective Gamification Versus DGBL in Primary School Health Education

2.3. Implementation Technologies for Primary School Health Education: Gamification Tools Versus Complete DGBL Platforms

3. Materials and Methods

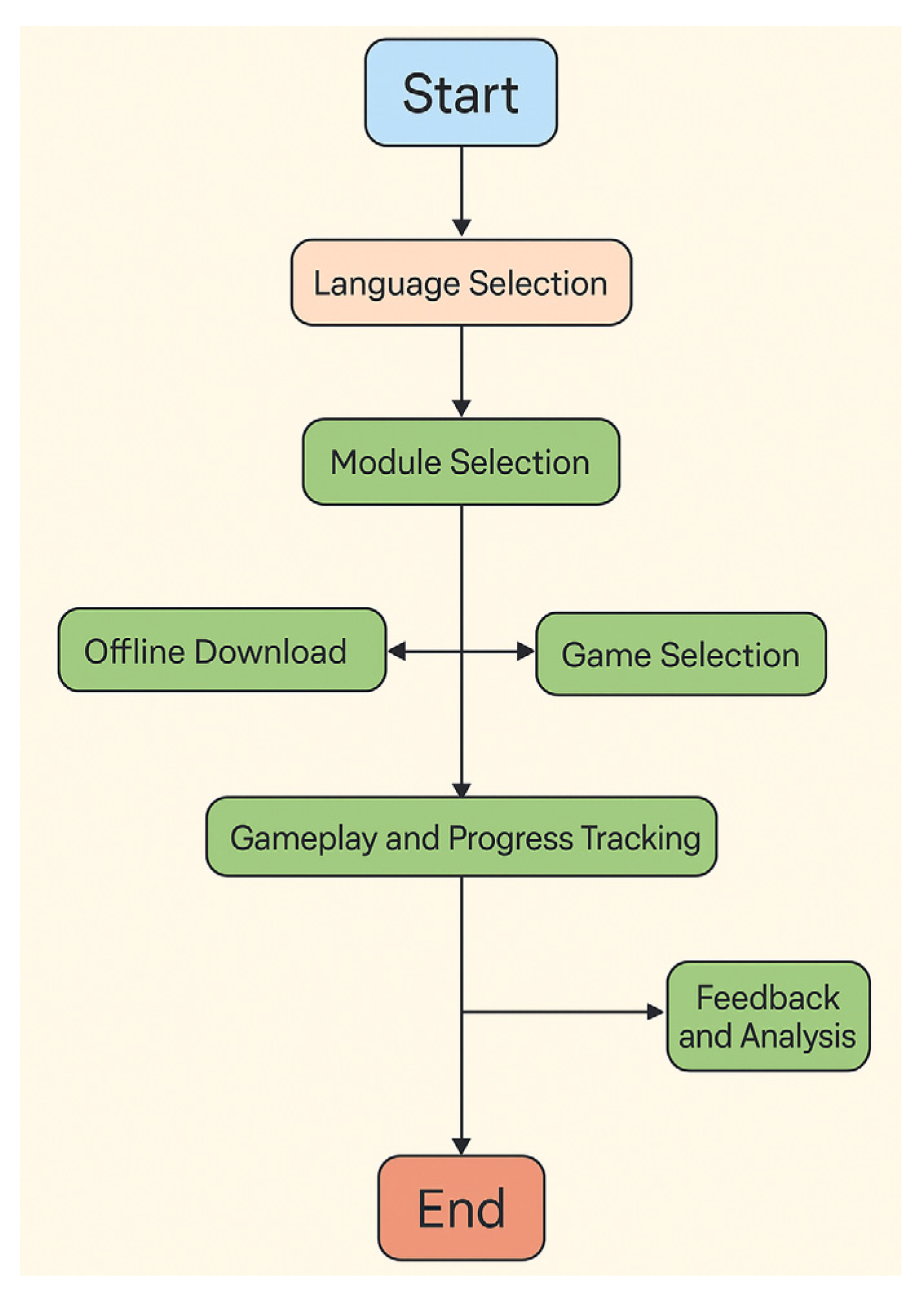

3.1. Platform Development Framework

3.2. Study Design and Participant Selection

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

- Steps Completed: The platform’s modular structure consisted of 55 instructional steps. The majority of teachers completed 53 or more steps, indicating high task completion rates across the cohort.

- Total Time Spent: Time-on-platform varied substantially—from a few minutes to multiple days—reflecting diverse usage patterns and levels of engagement. A small subset of users accounted for disproportionately high usage, with time spent exceeding 85 hours in extreme cases.

- Progress Ratios: A normalized metric (steps completed / total steps) was used to compare engagement across users. This revealed a bimodal distribution: a large cluster of users completed most of the platform, while another cluster disengaged early.

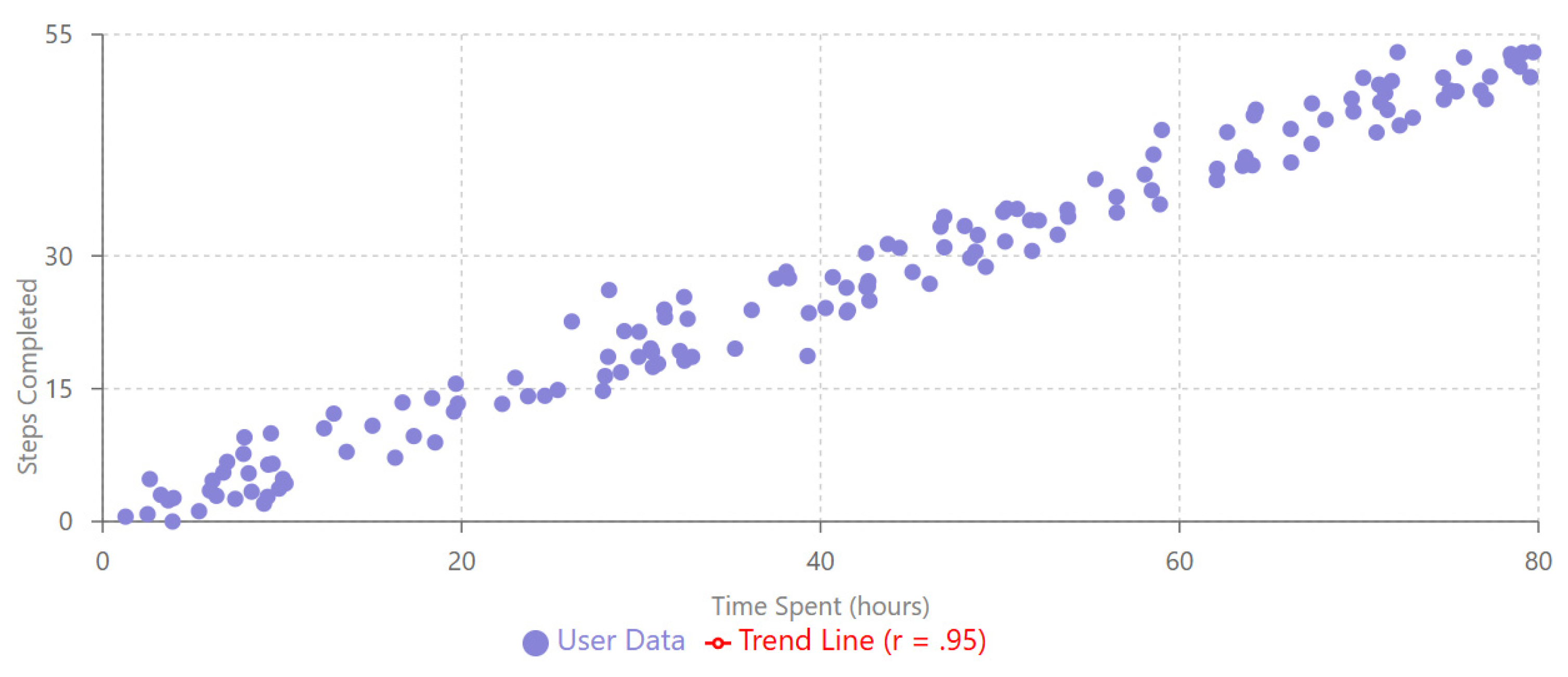

- Engagement Patterns by Demographics: Correlation analysis revealed strong positive relationships between age and both time spent (r = 0.60) and steps completed (r = 0.80). The strongest correlation was observed between steps completed and time spent (r = 0.95), emphasizing the importance of sustained interaction for educational progression.

3.4. Technical Architecture and Implementation

3.5. Integration and Testing

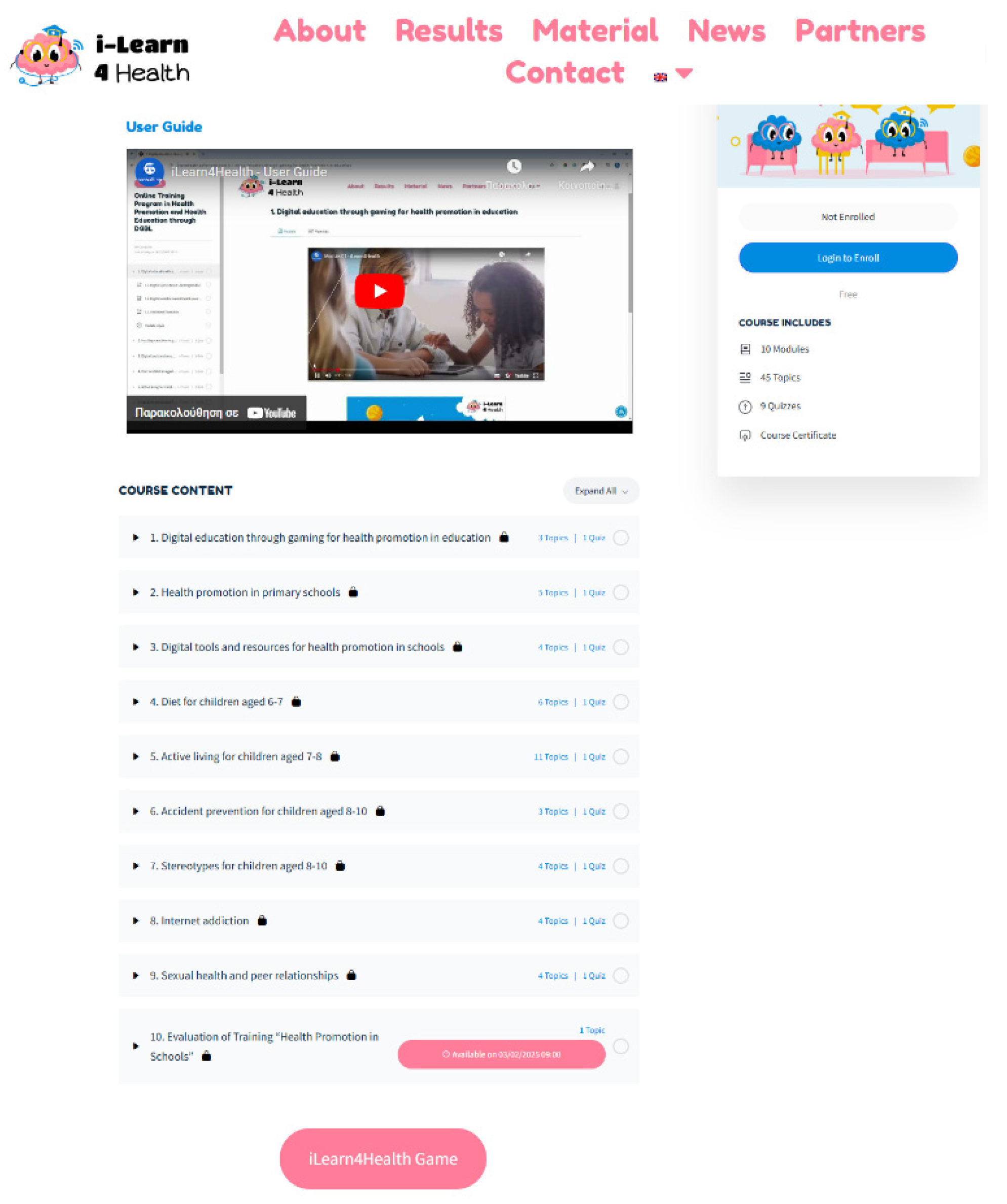

3.6. Online Training Program Development

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation Framework and Study Population

- Identify developmental differences in navigation patterns and interaction behaviors that inform age-appropriate design principles

- Isolate cognitive processing variations in how health information is interpreted across developmental stages

- Quantify differences in engagement duration and pattern metrics between children and adults to refine age-targeted game mechanics

- Validate that game elements were appropriately calibrated for primary school cognitive capabilities rather than inadvertently designed for more advanced cognitive stages

- Top-left: A navigation puzzle encouraging decision-making as the character progresses toward an “Exit” by selecting correct paths.

- Top-right: A multiple-choice question asking players to identify the healthiest meal option, reinforcing knowledge through engaging dialogue.

- Bottom-left: A character-run gameplay scene where players collect healthy food items while avoiding unhealthy ones.

- Bottom-right: A feedback screen highlighting the difference between vegetable oils and solid fats, reinforcing correct dietary decisions.

4.2. Digital Educational Games Implementation

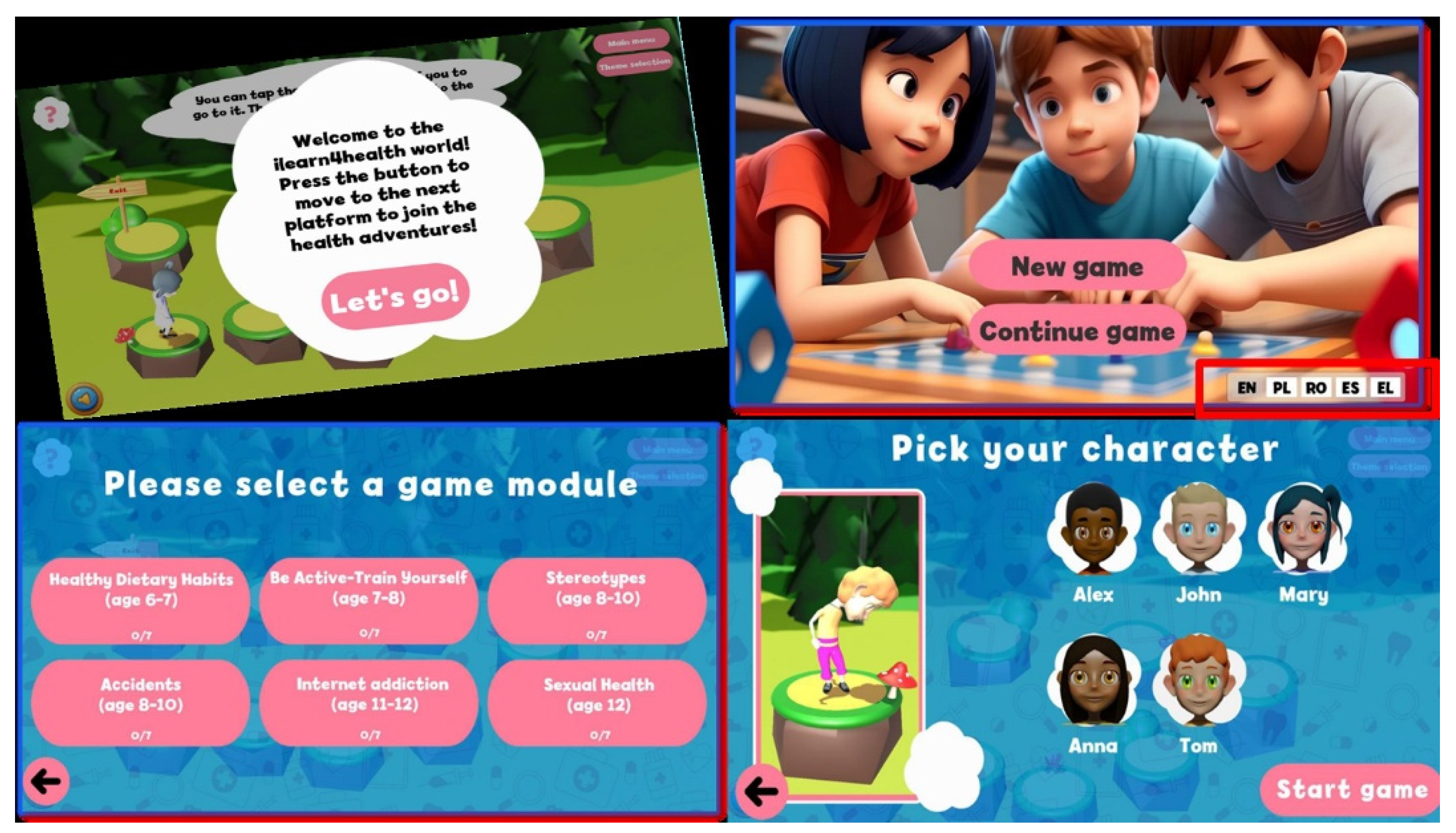

- Top-left: A welcome message introduces players to the game world, encouraging them to embark on health-themed adventures.

- Top-right: Main menu screen offering the options to start a new game or continue a previous session, with language selection for inclusivity.

- Bottom-left: Game module selection screen showcasing a variety of educational topics such as healthy eating, physical activity, internet safety, and more, each tailored to specific age groups.

- Bottom-right: Character selection interface where players can choose from diverse avatars, promoting personalization and engagement before starting the game.

4.3. Participant Demographics and Engagement Patterns

4.4. Progress Ratio Distribution and Engagement Patterns

4.5. Age-Based Engagement Patterns

4.6. Cross-National Implementation Analysis

4.7. Correlation Analysis and Engagement Relationships

4.8. Multiple Regression Analysis: Predictors of Engagement

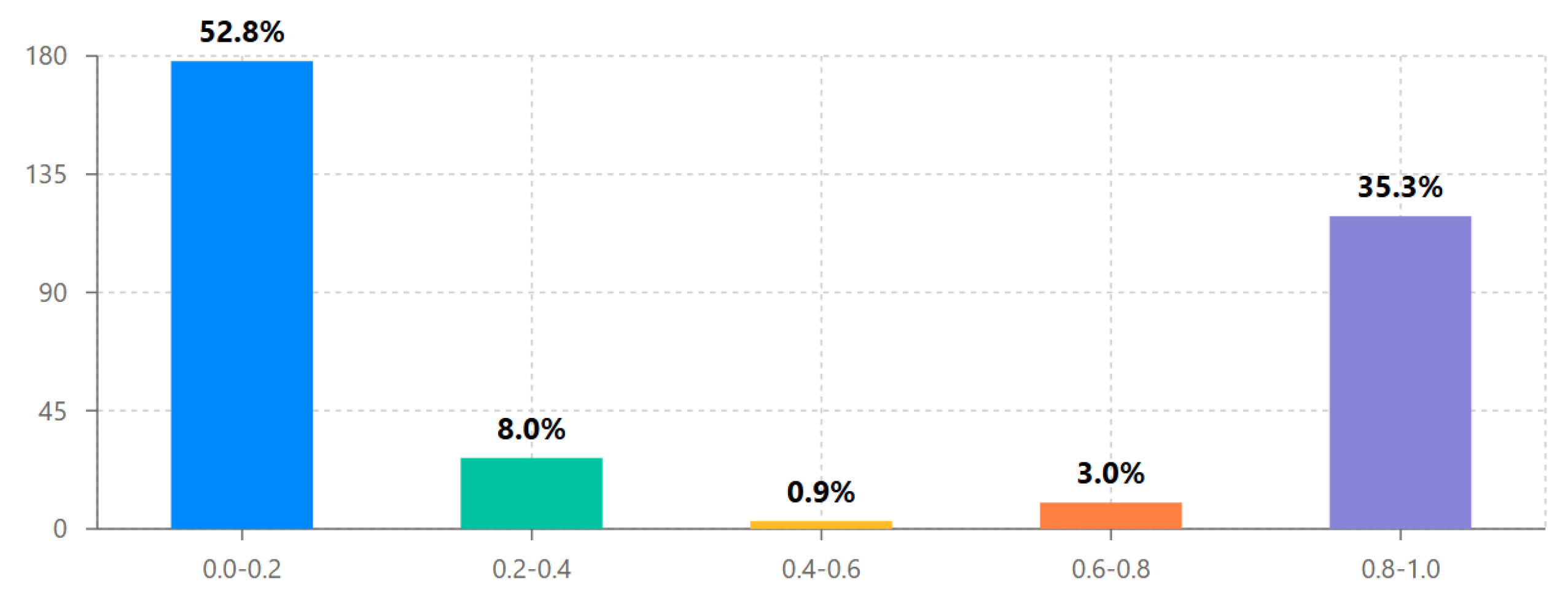

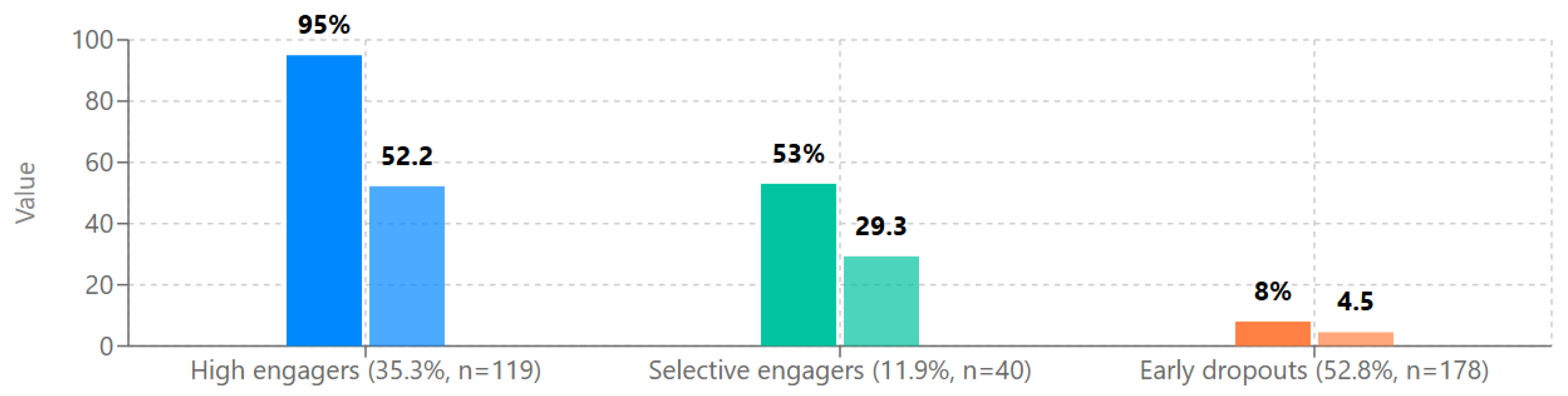

4.9. Cluster Analysis: User Typologies.

4.10. Summary of Key Findings

- User engagement followed a distinctive bimodal distribution, with 52.8% showing low engagement and 35.3% showing high engagement, supporting the hypothesis that once users progress beyond initial exploration, they typically continue to completion.

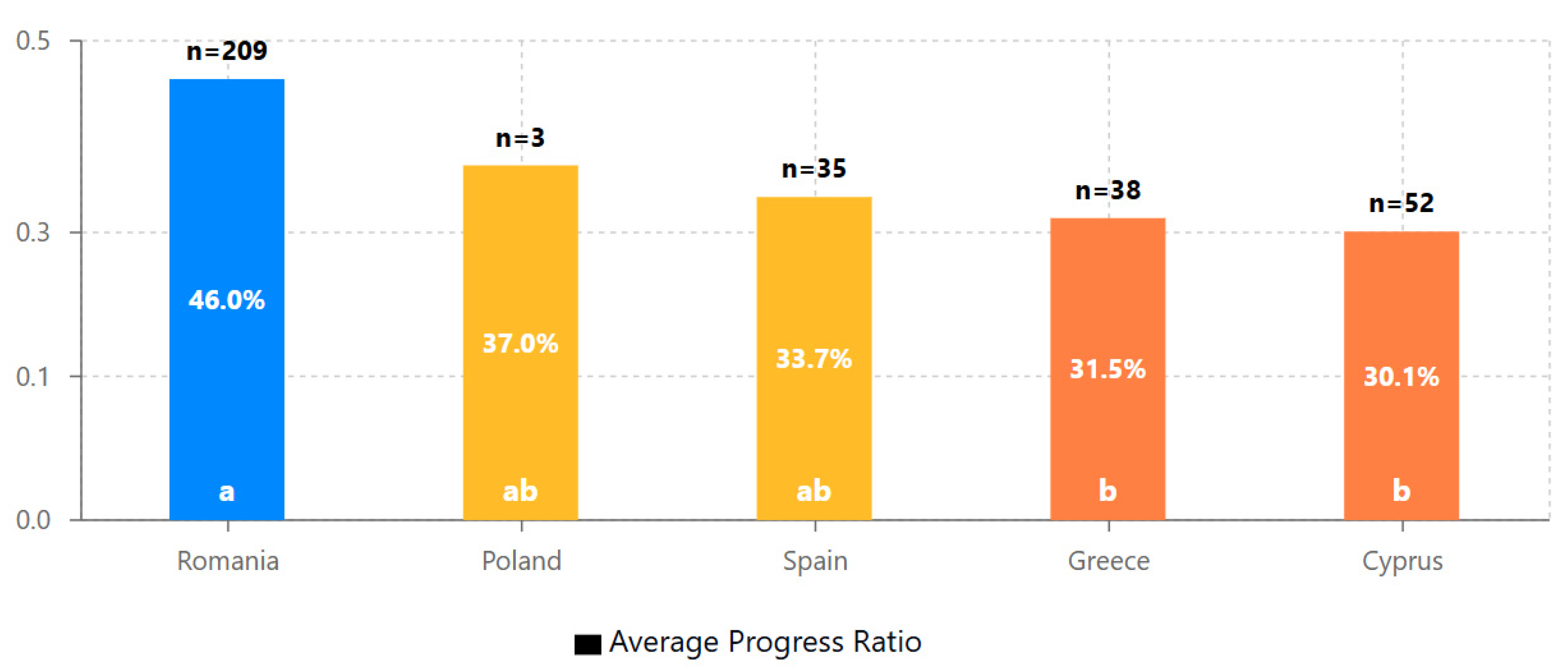

- Significant cross-national differences were observed, with Romania showing 53% higher average progress ratios than Cyprus (0.460 vs. 0.301, p < .01), indicating important contextual factors in Digital Game-Based Learning implementation.

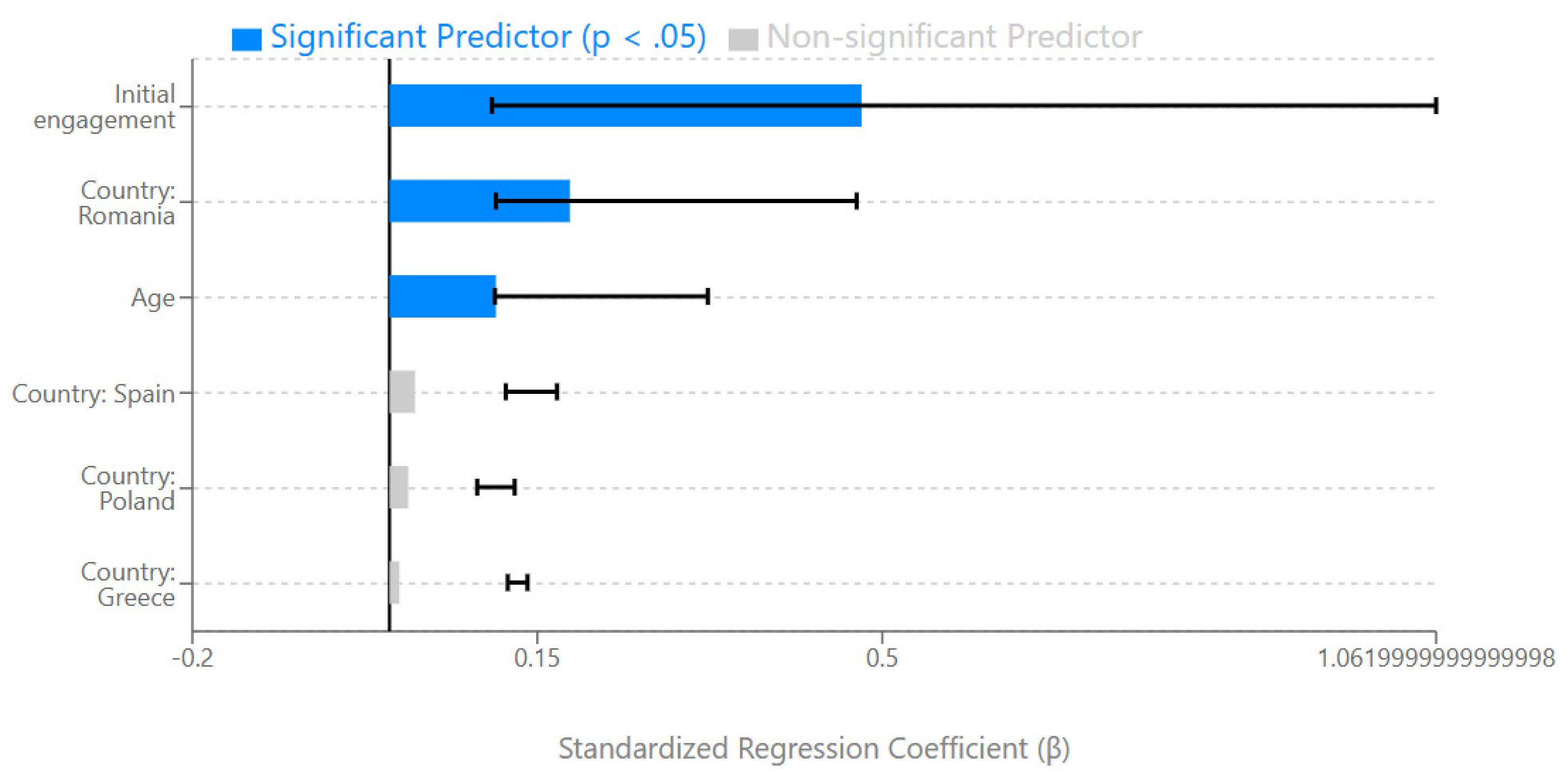

- Initial engagement emerged as the strongest predictor of overall progress (β = 0.479, p < .001), suggesting that the early platform experience plays a crucial role in determining long-term engagement outcomes.

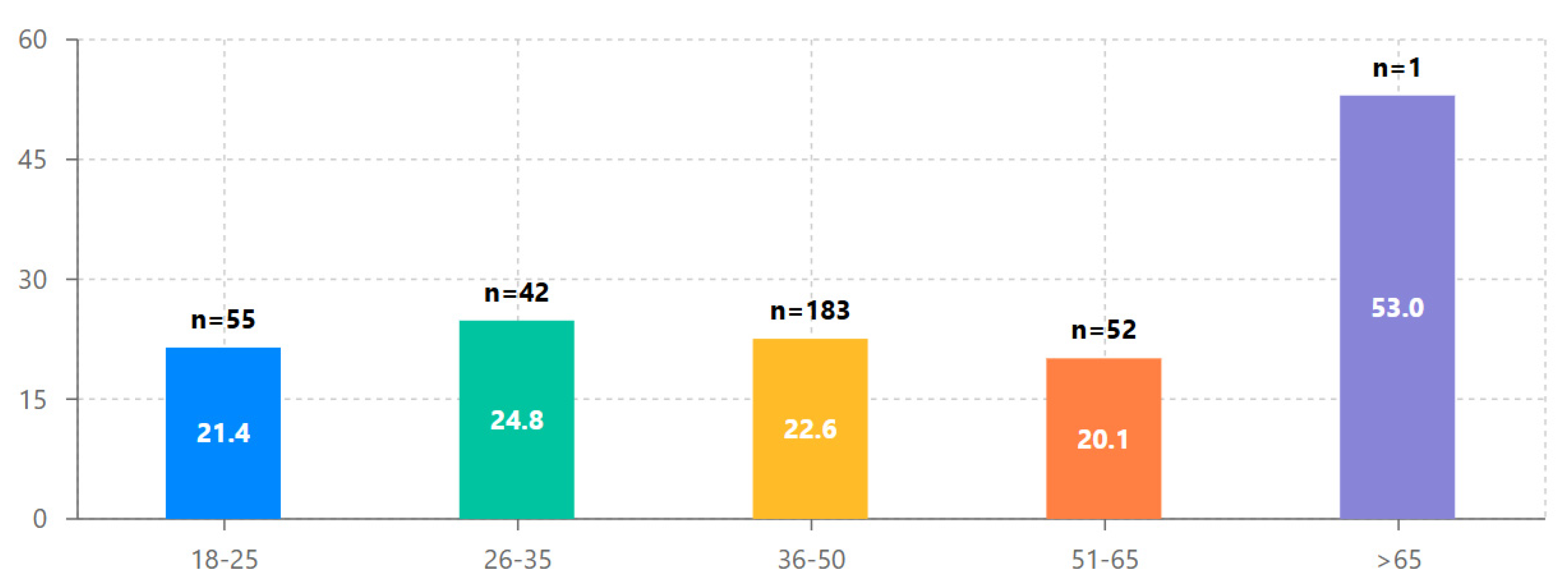

- Age had a statistically significant but small effect on engagement (β = 0.108, p = .049), with the 26-35 age group showing the highest average steps completed (M = 24.83).

- Cluster analysis identified three distinct user typologies (high engagers, early dropouts, and selective engagers), providing a more nuanced understanding of engagement patterns beyond the simple bimodal distribution.

- A strong positive correlation between steps completed and time spent (r = .95, p < .001) confirmed that sustained engagement is essential for progression through educational content in Digital Game- Based Learning environments.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Distinctions Between DGBL and Gamification in Health Education

5.2. Assessment and Evaluation of DGBL in Primary School Health Education

5.3. Technical Considerations in Implementing DGBL for Primary School Health Education

5.4. Data Privacy and Ethical Considerations in DGBL Health Education

5.5. Emerging Technologies in DGBL for Health Education

5.6. Limitations

5.7. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Camacho-Sánchez, R. , Rillo-Albert, A., & Lavega-Burgués, P. (2022). Gamified digital game-based learning as a pedagogical strategy: Student academic performance and motivation. Applied Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. , & Yu, Z. (2022). Meta-Analysis on Investigating and Comparing the Effects on Learning Achievement and Motivation for Gamification and Game-Based Learning. Education Research International. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, C. V. , & Coelho, A. (2022). Game-based learning, gamification in education and serious games. Computers. [CrossRef]

- Dahalan, F. , Alias, N., & Shaharom, M. S. N. (2024). Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: A systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S. , & Christopher B, P. (2023). A bibliometric analysis of the use of the Gamification Octalysis Framework in training: Evidence from Web of Science. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. [CrossRef]

- Oke, A. E. , Aliu, J., Tunji-Olayeni, P., & Abayomi, T. (2024). Application of gamification for sustainable construction: An evaluation of the challenges. Construction Innovation. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D. , Playfoot, J., De Nicola, C., Guarino, G., Bratu, M., Di Salvadore, F., & Muntean, G. M. (2021). An innovative multi-layer gamification framework for improved STEM learning experience. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Vijay, M. , & Jayan, J. P. (2023). Evolution of research on adaptive gamification: A bibliometric study. In 2023 International Conference on Circuit Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT). [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Tejedor, C. , & Cencerrado, A. (2024). Gamification for mental health and health psychology: Insights at the first quarter mark of the 21st century. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Speelman, E. N. , Escano, E., Marcos, D., & Becu, N. (2023). Serious games and citizen science; from parallel pathways to greater synergies. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, Z. , Karimian, Z., Zarifsanaiey, N., & Farahmandi, A. Y. (2025). A scoping review of gamified applications in English language teaching: A comparative discussion with medical education. BMC Medical Education. [CrossRef]

- Xu, M. , Luo, Y., Zhang, Y., Xia, R., Qian, H., & Zou, X. (2023). Game-based learning in medical education. Frontiers in Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A. , Ali, S., & Fotaris, P. (2023). Assessing the efficacy of reflective game design: A design-based study in digital game-based learning. Education Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Abou Hashish, E. A. , Al Najjar, H., Alharbi, M., Alotaibi, M., & Alqahtany, M. M. (2024). Faculty and students perspectives towards game-based learning in health sciences higher education. Heliyon. [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Smith, L. (2022). Knowledge brokering to bridge the research-practice gap in education: Where are we now? Review of Education. [CrossRef]

- Cong-Lem, N. , Soyoof, A., & Tsering, D. (2025). A systematic review of the limitations and associated opportunities of ChatGPT. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction.

- Taneja-Johansson, S. , & Singal, N. (2025). Pathways to inclusive and equitable quality education for people with disabilities: Cross-context conversations and mutual learning. International Journal of Inclusive Education. [CrossRef]

- Samala, A. D. , Rawas, S., Wang, T., Reed, J. M., Kim, J., Howard, N. J., & Ertz, M. (2025). Unveiling the landscape of generative artificial intelligence in education: A comprehensive taxonomy of applications, challenges, and future prospects. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Caprara, L. , & Caprara, C. (2022). Effects of virtual learning environments: A scoping review of literature. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K. M. , & Platt, J. M. (2024). Annual Research Review: Sex, gender, and internalizing conditions among adolescents in the 21st century—Trends, causes, consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Halkiopoulos, C. , & Gkintoni, E. (2024). Leveraging AI in E-Learning: Personalized Learning and Adaptive Assessment through Cognitive Neuropsychology—A Systematic Analysis. Electronics, 13(18), 3762. [CrossRef]

- Muniandy, N. , Kamsin, A., & Sabri, M. I. (2023). Enhancing Children’s Health Awareness through Narrative Game-Based Learning using Digital Technology: A Framework and Methodology. In 2023 9th International HCI and UX Conference in Indonesia (CHIuXiD). [CrossRef]

- All, A. , Castellar, E. N. P., & Van Looy, J. (2021). Digital Game-Based Learning effectiveness assessment: Reflections on study design. Computers & Education. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H. , Halkiopoulos, C., Gkintoni, E., Katsibelis, A. (2022). Application of Gamification Tools for Identification of Neurocognitive and Social Function in Distance Learning Education. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(5), 367–400. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. , Liu, P., Zhang, J., Zhong, J., Luo, X., Huang, J., & Zheng, Y. (2023). Effects of digital game-based learning on students’ cyber wellness literacy, learning motivations, and engagement. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C. , Martin, C. F., Alonso-Martínez, L., & Almeida, L. S. (2021). Usefulness of digital game-based learning in nursing and occupational therapy degrees: A comparative study at the University of Burgos. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Feldhacker, D. R. , Wesner, C., Yockey, J., Larson, J., & Norris, D. (2025). Strategies for Health: A game-based, interprofessional approach to teaching social determinants of health: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Interprofessional Care. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Calatayud, M. , García-García, R., Regaira-Martínez, E., & Gómez-Urquiza, J. (2024). Real-world and game-based learning to enhance decision-making. Nurse Education Today. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. , Vantaraki, F., Skoulidi, C., Anastassopoulos, P., & Vantarakis, A. (2024). Gamified Health Promotion in Schools: The Integration of Neuropsychological Aspects and CBT—A Systematic Review. Medicina, 60(12), 2085. [CrossRef]

- del Cura-González, I. , Ariza-Cardiel, G., Polentinos-Castro, E., López-Rodríguez, J. A., Sanz-Cuesta, T., Barrio-Cortes, J.,... & Martín-Fernández, J. (2022). Effectiveness of a game-based educational strategy e-EDUCAGUIA for implementing antimicrobial clinical practice guidelines in family medicine residents in Spain: A randomized clinical trial by cluster. BMC Medical Education. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. , Dimakos, I., & Nikolaou, G. (2025). Cognitive Insights from Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review of EI Models in Educational Achievement. Emerging Science Journal, 8, 262–297. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P. , & Goyal, P. (2022). Is game-based pedagogy just a fad? A self-determination theory approach to gamification in higher education. International Journal of Educational Management. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. (2024). Advancing gamification research and practice with three underexplored ideas in self-determination theory. TechTrends. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H. , Figueiredo, G., Pereira, B., Magalhães, M., Rosário, P., & Magalhães, P. (2024). Understanding Children’s Perceptions of Game Elements in an Online Gamified Intervention: Contributions by the Self-Determination Theory. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. [CrossRef]

- Nivedhitha, K. S. , Giri, G., & Pasricha, P. (2025). Gamification as a panacea to workplace cyberloafing: An application of self-determination and social bonding theories. Internet Research. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. , & Zhao, S. (2022). Chinese EFL learners’ acceptance of gamified vocabulary learning apps: An integration of self-determination theory and technology acceptance model. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Tyack, A. , & Mekler, E. D. (2024). Self-determination theory and HCI games research: Unfulfilled promises and unquestioned paradigms. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction. [CrossRef]

- Breien, F. S. , & Wasson, B. (2021). Narrative categorization in digital game-based learning: Engagement, motivation & learning. British Journal of Educational Technology. [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, C. (2024). Faith in Frames: Constructing a Digital Game-Based Learning Framework for Religious Education. Teaching Theology & Religion. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. , Cheng, G., & Zou, D. (2025). Effects of digital game elements on engagement and vocabulary development. University of Hawaii.

- Nadeem, M. , Oroszlanyova, M., & Farag, W. (2023). Effect of digital game-based learning on student engagement and motivation. Computers. [CrossRef]

- Höyng, M. (2022). Encouraging gameful experience in digital game-based learning: A double-mediation model of perceived instructional support, group engagement, and flow. Computers & Education. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. , Ye, H. J., & Feng, Y. (2021). Using gamification elements for competitive crowdsourcing: Exploring the underlying mechanism. Behaviour & Information Technology. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. (2022). Gamification for educational purposes: What are the factors contributing to varied effectiveness? Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. , & Castelli, D. M. (2021). Effects of gamification on behavioral change in education: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Macey, J. , Adam, M., Hamari, J., & Benlian, A. (2025). Examining the commonalities and differences between gamblification and gamification: A theoretical perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction.

- Riar, M. , Morschheuser, B., Zarnekow, R., & Hamari, J. (2022). Gamification of cooperation: A framework, literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Information Management. [CrossRef]

- Nordby, A. , Vibeto, H., Mobbs, S., & Sverdrup, H. U. (2024). System thinking in gamification. SN Computer Science. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z. , Liu, Q., & Huang, X. (2022). The influence of digital educational games on preschool children’s creative thinking. Computers & Education. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T., S. S., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2022). Brands in a game or a game for brands? Comparing the persuasive effectiveness of in-game advertising and advergames. Psychology & Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A. , Pinkwart, N., & Shafi, M. (2021). Serious games to improve social and emotional intelligence in children with autism. Entertainment Computing. [CrossRef]

- Henry, J. , Hernalesteen, A., & Collard, A. S. (2021). Teaching artificial intelligence to K-12 through a role-playing game questioning the intelligence concept. KI-Künstliche Intelligenz. [CrossRef]

- Masi, L. , Abadie, P., Herba, C., Emond, M., Gingras, M. P., & Amor, L. B. (2021). Video games in ADHD and non-ADHD children: Modalities of use and association with ADHD symptoms. Frontiers in Pediatrics. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, R. , Maguire, M., Turner, S., Arenas, F., & Guimarães, L. (2022). Ocean literacy gamified: A systematic evaluation of the effect of game elements on students’ learning experience. Environmental Education Research. [CrossRef]

- Dah, J. , Hussin, N., Zaini, M. K., Isaac Helda, L., Senanu Ametefe, D., & Adozuka Aliu, A. (2024). Gamification is not working: Why?. Games and Culture. [CrossRef]

- Kniestedt, I. , Lefter, I., Lukosch, S., & Brazier, F. M. (2022). Re-framing engagement for applied games: A conceptual framework. Entertainment Computing. [CrossRef]

- Torresan, S. , & Hinterhuber, A. (2023). Continuous learning at work: The power of gamification. Management Decision. [CrossRef]

- Leitão, R. , Maguire, M., Turner, S., & Guimarães, L. (2022). A systematic evaluation of game elements effects on students’ motivation. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Tzachrista, M. , Gkintoni, E., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2023). Neurocognitive Profile of Creativity in Improving Academic Performance—A Scoping Review. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1127. [CrossRef]

- Pitic, D. , & Irimiaș, T. (2023). Enhancing students’ engagement through a business simulation game: A qualitative study within a higher education management course. The International Journal of Management Education. [CrossRef]

- Wiljén, A. , Chaplin, J. E., Crine, V., Jobe, W., Johnson, E., Karlsson, K.,... & Nilsson, S. (2022). The development of an mHealth tool for children with long-term illness to enable person-centered communication: User-centered design approach. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting. [CrossRef]

- Burn, A. M. , Ford, T. J., Stochl, J., Jones, P. B., Perez, J., & Anderson, J. K. (2022). Developing a web-based app to assess mental health difficulties in secondary school pupils: Qualitative user-centered design study. JMIR Formative Research. [CrossRef]

- Peláez, C. A. , & Solano, A. (2023). A practice for the design of interactive multimedia experiences based on gamification: A case study in elementary education. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Govender, T. , & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2021). An analysis of game design elements used in digital game-based language learning. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Pellas, N. , Mystakidis, S., & Christopoulos, A. (2021). A systematic literature review on the user experience design for game-based interventions via 3D virtual worlds in K-12 education. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction. [CrossRef]

- Ongoro, C. A. , & Fanjiang, Y. Y. (2023). Digital game-based technology for English language learning in preschools and primary schools: A systematic analysis. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. , Prinz, A., Gerdes, M., Martinez, S., Pahari, N., & Meena, Y. K. (2022). ProHealth eCoach: User-centered design and development of an eCoach app to promote healthy lifestyle with personalized activity recommendations. BMC Health Services Research. [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, A. , de Courten, M., & Prokofieva, M. (2022). The potential of social media in health promotion beyond creating awareness: An integrative review. BMC Public Health. [CrossRef]

- AlDaajeh, S. , Saleous, H., Alrabaee, S., Barka, E., Breitinger, F., & Choo, K. K. R. (2022). The role of national cybersecurity strategies on the improvement of cybersecurity education. Computers & Security. [CrossRef]

- Kulkov, I. , Kulkova, J., Rohrbeck, R., Menvielle, L., Kaartemo, V., & Makkonen, H. (2024). Artificial intelligence-driven sustainable development: Examining organizational, technical, and processing approaches to achieving global goals. Sustainable Development. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. (). Educational affordances of music video games and gaming mobile apps. Technology.

- Zahedi, L. , Batten, J., Ross, M., Potvin, G., Damas, S., Clarke, P., & Davis, D. (2021). Gamification in education: A mixed-methods study of gender on computer science students’ academic performance and identity development. Journal of Computing in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Weatherly, K. I. C. H. , Wright, B. A., & Lee, E. Y. (2024). Digital game-based learning in music education: A systematic review between 2011 and 2023. Research Studies in Music Education. [CrossRef]

- Crepax, T. , Muntés-Mulero, V., Martinez, J., & Ruiz, A. (2022). Information technologies exposing children to privacy risks: Domains and children-specific technical controls. Computer Standards & Interfaces. [CrossRef]

- Michael, K. (2024). Mitigating Risk and Ensuring Human Flourishing Using Design Standards: IEEE 2089-2021 an Age Appropriate Digital Services Framework for Children. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. , Zhao, J., Van Kleek, M., & Shadbolt, N. (2022). Informing age-appropriate AI: Examining principles and practices of AI for children. Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A. K. , Barthwal, A., Campbell, M., Shouli, A., Syed, S., Joshi, S., & Vassileva, J. (2024). Navigating AI to unpack youth privacy concerns: An in-depth exploration and systematic review. arXiv:2412.16369.

- Zhao, D. , Inaba, M., & Monroy-Hernández, A. (2022). Understanding teenage perceptions and configurations of privacy on Instagram. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J. C. , Walker, K. L., Netemeyer, R. G., & Kees, J. (2023). Helping youth navigate privacy protection: Developing and testing the children’s online privacy scale. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Basyoni, L. , Tabassum, A., Shaban, K., Elmahjub, E., Halabi, O., & Qadir, J. (2024). Navigating Privacy Challenges in the Metaverse: A Comprehensive Examination of Current Technologies and Platforms. IEEE Internet of Things Magazine. [CrossRef]

- Udoudom, U. , George, K., & Igiri, A. (2023). Impact of digital learning platforms on behaviour change communication in public health education. Pancasila International Journal of Applied Social Science. [CrossRef]

- Ventouris, A. , Panourgia, C., & Hodge, S. (2021). Teachers’ perceptions of the impact of technology on children and young people’s emotions and behaviours. International Journal of Educational Research Open. [CrossRef]

- Novak, E. , McDaniel, K., Daday, J., & Soyturk, I. (2022). Frustration in technology-rich learning environments: A scale for assessing student frustration with e-textbooks. British Journal of Educational Technology. [CrossRef]

- Drljević, N. , Botički, I., & Wong, L. H. (2022). Investigating the different facets of student engagement during augmented reality use in primary school. British Journal of Educational Technology. [CrossRef]

- Buzzai, C. , Sorrenti, L., Costa, S., Toffle, M. E., & Filippello, P. (2021). The relationship between school-basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration, academic engagement and academic achievement. School Psychology International. [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, A. , & Sprangers, P. (2021). Integration of educational technology during the Covid-19 pandemic: An analysis of teacher and student receptions. Cogent Education. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P. , Singal, N., & Francis, G. A. (2024). Educational technology for learners with disabilities in primary school settings in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic literature review. Educational Review. [CrossRef]

- Balalle, H. (2024). Exploring student engagement in technology-based education in relation to gamification, online/distance learning, and other factors: A systematic literature …. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. H. (2021). Sustainable education through e-learning: The case study of iLearn2.0. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Zohari, M. , Karim, N., Malgard, S., Aalaa, M., Asadzandi, S., & Borhani, S. (2023). Comparison of gamification, game-based learning, and serious games in medical education: A scientometrics analysis. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism.

- Leonardou, A. , Rigou, M., Panagiotarou, A., & Garofalakis, J. (2022). Effect of OSLM features and gamification motivators on motivation in DGBL: Pupils’ viewpoint. Smart Learning Environments. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X. , Sun, C., Hwang, G. J., Xue, K., & Wang, Z. (2024). Applying game-based learning in primary education: A systematic review of journal publications from 2010 to 2020. Interactive Learning Environments. [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Sánchez, R. , Manzano-León, A., Rodríguez-Ferrer, J. M., Serna, J., & Lavega-Burgués, P. (2023). Game-based learning and gamification in physical education: A systematic review. Education Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, W. Y. , Chen, C. H., Chen, P. C., & Hou, W. H. (2024). Investigating the effects of different game-based learning on the health care knowledge and emotions for middle-aged and older adults. Interactive Learning Environments. [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, W. Y. , Chen, C. H., Chen, P. C., & Hou, W. H. (2024). Investigating the effects of different game-based learning on the health care knowledge and emotions for middle-aged and older adults. Interactive Learning Environments. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. , Vantaraki, F., Skoulidi, C., Anastassopoulos, P., & Vantarakis, A. (2024). Promoting Physical and Mental Health among Children and Adolescents via Gamification—A Conceptual Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 102. [CrossRef]

- Gajardo Sánchez, A. D. , Murillo-Zamorano, L. R., López-Sánchez, J., & Bueno-Muñoz, C. (2023). Gamification in health care management: Systematic review of the literature and research agenda. SAGE Open, 13(4), 21582440231218834. [CrossRef]

- Arruzza, E. , & Chau, M. (2021). A scoping review of randomized controlled trials to assess the value of gamification in the higher education of health science students. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Arora, C. , & Razavian, M. (2021). Ethics of gamification in health and fitness tracking. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11052. [CrossRef]

- Warsinsky, S. , Schmidt-Kraepelin, M., Rank, S., Thiebes, S., & Sunyaev, A. (2021). Conceptual ambiguity surrounding gamification and serious games in healthcare: Literature review and development of game-based intervention reporting guidelines (GAMING). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(9), e30390. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. , & Ebrahimi, O. V. (2023). A meta-analytic review of gamified interventions in mental health enhancement. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Castillo, L. , & Clavijo-Rodriguez, A. (2021). Gamification and deep learning approaches in higher education. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. , & Ebrahimi, O. V. (2023). Gamification: A novel approach to mental health promotion. Current Psychiatry Reports. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Z. , & Sankey, M. (2016). Reboot your course—From Beta to better.

- Landers, R. N. , & Sanchez, D. R. (2022). Game-based, gamified, and gamefully designed assessments for employee selection: Definitions, distinctions, design, and validation. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 30(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mazeas, A. , Duclos, M., Pereira, B., & Chalabaev, A. (2022). Evaluating the effectiveness of gamification on physical activity: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e26779. [CrossRef]

- Furtado, L. S. , de Souza, R. F., Lima, J. L. D. R., & Oliveira, S. R. B. (2021). Teaching method for software measurement process based on gamification or serious games: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Computer Games Technology, 2021(1), 8873997. [CrossRef]

- Krath, J. , Schürmann, L., & Von Korflesch, H. F. O. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games, and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, A. , Aghaei, Z., & Mahdavi, M. A. (2021). A gamification framework for cognitive assessment and cognitive training: Qualitative study. JMIR Serious Games, 9(1), e21900. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, S. , & Yüzer, T. V. (2022). Analyzing adaptive gamification design principles for online courses. Behaviour & Information Technology. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. , Yin, X., Yin, W., Dong, X., & Li, Q. (2023). Evaluation of gamification techniques in learning abilities for higher school students using FAHP and EDAS methods. Soft Computing. [CrossRef]

- Aresi, G. , Chiavegatti, B., & Marta, E. (2024). Participants’ experience with gamification elements of a school-based health promotion intervention in Italy: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Prevention. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E. N. M. , Jamali, N., Suhaimi, A. I. H. (2021). Exploring gamification design elements for mental health support. International Journal of Advanced Technology and Engineering Exploration, 8(74), 114. [CrossRef]

- Alamri, I. K. A. (2024). Gameful learning: Investigating the impact of game elements, interactivity, and learning style on students’ success. Multidisciplinary Science Journal. [CrossRef]

- Vorlíček, M. , Prycl, D., Heidler, J., Herrador-Colmenero, M., Nábělková, J., Mitáš, J.,... & Frömel, K. (2024). Gameful education: A study of Gamifiter application’s role in promoting physical activity and active lifestyle. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y. (2024). The role of playfulness in gamification for health behavior motivation.

- De Salas, K. , Ashbarry, L., Seabourne, M., Lewis, I., Wells, L., Dermoudy, J.,... & Scott, J. (2022). Improving environmental outcomes with games: An exploration of behavioral and technological design and evaluation approaches. Simulation & Gaming, 53(5), 470-512. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. , & Castelli, D. M. (2021). Effects of gamification on behavioral change in education: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3550. [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M. F. , Xu, S., Rehman, O., & Javed, I. (2023). Impact of gamification on green consumption behavior integrating technological awareness, motivation, enjoyment, and virtual CSR. Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. , Lio, A., Dhaliwal, H., Andrei, S., Balakrishnan, S., Nagani, U., & Samadder, S. (2021). Psychological interventions of virtual gamification within academic intrinsic motivation: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 444-465. [CrossRef]

- Jingili, N. , Oyelere, S. S., Nyström, M. B., Anyshchenko, L. (2023). A systematic review on the efficacy of virtual reality and gamification interventions for managing anxiety and depression. Frontiers in Digital Health, 5, 1239435. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, N. (2021). Introducing gamification for advancing current mental healthcare and treatment practices. IoT in Healthcare and Ambient Assisted Living. [CrossRef]

- Hassan Alhazmi, A. , & Asanka Gamagedara Arachchilage, N. (2023). Evaluation of game design framework using a gamified browser-based application.

- Di Minin, E. , Fink, C, Hausmann, A., Kremer, J., Kulkarni, R. (2021). How to address data privacy concerns when using social media data in conservation science. Conservation Biology ( 35(2), 437-–446. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. , & Ahmed, G. (2021). Improving IoT privacy, data protection, and security concerns. International Journal of Technology, Innovation and Management (IJTIM), 1(1), 18-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komljenovic, J. (2022). The future of value in digitalised higher education: Why data privacy should not be our biggest concern. Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Birch, K. , Cochrane, D. T., & Ward, C. (2021). Data as asset? The measurement, governance, and valuation of digital personal data by Big Tech. Big Data & Society. [CrossRef]

- Quach, S. , Thaichon, P., Martin, K. D., Weaven, S., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Digital technologies: Tensions in privacy and data. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(6), 1299-1323. [CrossRef]

- Lappeman, J. , Marlie, S., Johnson, T., & Poggenpoel, S. (2022). Trust and digital privacy: Willingness to disclose personal information to banking chatbot services. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 28(2), 337. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. L. , Brinson, N. H., Bott, G. J., & Moeller, C. M. (2021). The influence of consumer-brand relationships on the personalized advertising privacy calculus in social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 55(1), 16-30. [CrossRef]

- Cichy, P. , Salge, T. O., & Kohli, R. (2021). Privacy concerns and data sharing in the Internet of Things: Mixed methods evidence from connected cars. MIS Quarterly. [CrossRef]

- Trang, S. , & Weiger, W. H. (2021). The perils of gamification: Does engaging with gamified services increase users’ willingness to disclose personal information? Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiu, D. , Blok, V., Coenen, C., Kalloniatis, C., Kitsiou, A., Mavroeidi, A. G.,... & Sitzia, A. (2022). Responsible innovation at work: Gamification, public engagement, and privacy by design. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 9(3), 315-343. [CrossRef]

- Farhan, K. A. , Asadullah, A. B. M., Kommineni, H. P., Gade, P. K., & Venkata, S. S. M. G. N. (2023). Machine learning-driven gamification: Boosting user engagement in business. Global Disclosure of Economics and Business, 12(1), 41-52. [CrossRef]

- Van Toorn, C. , Kirshner, S. N., & Gabb, J. (2022). Gamification of query-driven knowledge sharing systems. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(5), 959-980. [CrossRef]

- Simonofski, A. , Zuiderwijk, A., Clarinval, A., & Hammedi, W. (2022). Tailoring open government data portals for lay citizens: A gamification theory approach. International Journal of Information Management, 65, 102511. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, W. , Hamari, J., Joaquim, S., Toda, A. M., Palomino, P. T., Vassileva, J., & Isotani, S. (2022). The effects of personalized gamification on students’ flow experience, motivation, and enjoyment. Smart Learning Environments, 9(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R. , Wu, Z., & Hamari, J. (2022). Internet-of-gamification: A review of literature on IoT-enabled gamification for user engagement. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 38(12), 1113-1137. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rayes, S. , Al Yaqoub, F. A., Alfayez, A., Alsalman, D., Alanezi, F., Alyousef, S., ... Alanzi, T. M. (2022). Gaming elements, applications, and challenges of gamification in healthcare. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 31, 100974. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, P. (2021). The influence of gamification and information technology identity on postadoption behaviors of health and fitness app users: Empirical study in the United States. JMIR Serious Games. [CrossRef]

- Andrea Navarro-Espinosa, J. , Vaquero-Abellán, M., Perea-Moreno, A. J., Pedrós-Pérez, G., del Pilar Martínez-Jiménez, M., & Aparicio-Martínez, P. (2022). Gamification as a promoting tool of motivation for creating sustainable higher education institutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Alam, A. (2023, March). Leveraging the power of ’modeling and computer simulation’ for education: An exploration of its potential for improved learning outcomes and enhanced student engagement. In 2023 International Conference on Device Intelligence, Computing and Communication Technologies (DICCT) (pp. 445-450). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. , Antonopoulou, H., Sortwell, A., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2025). Challenging Cognitive Load Theory: The Role of Educational Neuroscience and Artificial Intelligence in Redefining Learning Efficacy. Brain Sciences, 15(2), 203. [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | Mdn | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.64 | 14.04 | 18 | 66 | 41 | -0.27 | -0.83 |

| Steps completed | 22.31 | 23.79 | 0 | 53 | 8 | 0.31 | -1.85 |

| Progress ratio | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0 | 0.96 | 0.15 | 0.47 | -1.74 |

| Country | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | 209 | 62.0 | [56.8, 67.2] |

| Cyprus | 52 | 15.4 | [11.5, 19.3] |

| Greece | 38 | 11.3 | [7.9, 14.7] |

| Spain | 35 | 10.4 | [7.1, 13.7] |

| Poland | 3 | 0.9 | [0, 1.9] |

| Progress ratio | n | % | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0-0.2 | 178 | 52.8 | 52.8 |

| 0.2-0.4 | 27 | 8.0 | 60.8 |

| 0.4-0.6 | 3 | 0.9 | 61.7 |

| 0.6-0.8 | 10 | 3.0 | 64.7 |

| 0.8-1.0 | 119 | 35.3 | 100.0 |

| Age group | n | Steps completed | Progress ratio | Cohen’s d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 95% CI | M | SD | |||

| 18-25 | 55 | 21.45 | 22.87 | [15.20, 27.70] | 0.39 | 0.42 | - |

| 26-35 | 42 | 24.83 | 23.15 | [17.61, 32.05] | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.14 |

| 36-50 | 183 | 22.55 | 24.16 | [19.02, 26.08] | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.05 |

| 51-65 | 52 | 20.10 | 24.33 | [13.32, 26.88] | 0.37 | 0.44 | -0.05 |

| Country | n | Progress ratio | Significant differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 95% CI | |||

| Romania | 209 | 0.460 | 0.44 | [0.399, 0.521] | a |

| Poland | 3 | 0.370 | 0.41 | [0.000, 0.791] | a,b |

| Spain | 35 | 0.337 | 0.42 | [0.203, 0.471] | a,b |

| Greece | 38 | 0.315 | 0.40 | [0.190, 0.440] | b |

| Cyprus | 52 | 0.301 | 0.38 | [0.196, 0.406] | b |

| Source | SS | df | MS | F | p | η² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between groups | 1.26 | 4 | 0.315 | 4.37 | .002 | .050 |

| Within groups | 23.94 | 332 | 0.072 | |||

| Total | 25.20 | 336 |

| Variables | r | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steps completed—Time spent | .95 | [.93, .97] | < .001 |

| Age—Steps completed (full sample) | .01 | [-.10, .12] | .859 |

| Age—Steps completed (adult subgroup) | .80 | [.73, .85] | < .001 |

| Age—Time spent (adult subgroup) | .60 | [.50, .69] | < .001 |

| Progress ratio—Time spent | .94 | [.91, .96] | < .001 |

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.210 | 0.074 | 2.84 | .005 | [0.065, 0.355] | |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.108 | 1.97 | .049 | [0.000, 0.006] |

| Initial engagement* | 0.346 | 0.038 | 0.479 | 9.11 | < .001 | [0.271, 0.421] |

| Country: Romania† | 0.159 | 0.048 | 0.183 | 3.31 | .001 | [0.065, 0.253] |

| Country: Spain† | 0.036 | 0.065 | 0.026 | 0.55 | .580 | [-0.092, 0.164] |

| Country: Greece† | 0.014 | 0.063 | 0.010 | 0.22 | .825 | [-0.110, 0.138] |

| Country: Poland† | 0.069 | 0.165 | 0.019 | 0.42 | .676 | [-0.256, 0.394] |

| Cluster | n | Age | Steps completed |

Progress ratio |

Time spent (min) | Key characteristics |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| High engaging modules | 119 | 39.8 | 12.6 | 52.2 | 1.6 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 987.4 | 463.2 | Complete most/all modules |

| Early dropouts | 178 | 38.1 | 14.9 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 65.3 | 52.8 | Disengage after initial exploration |

| Selective Engagers | 40 | 37.9 | 13.5 | 29.3 | 7.1 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 384.6 | 159.7 | Complete specific topics of interest |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).