Introduction and Literature Review

Research on mountain finance and the financial system highlights the importance of this sector for high-altitude regions. Mountain financing and its financial system can be examined through the various socio-economic and eco-technological facets it encompasses.

One of the relevant researches explores the potential of carbon funding to support sustainable management of mountain ecosystems, such as alpine pastures and shrubs. The research highlights the lack of an appropriate technical and policy framework to integrate these ecosystems into international climate finance mechanisms, despite their significant carbon storage potential. The authors suggest a “top-down” conceptual framework to facilitate the inclusion of mountain natural resource management activities into climate finance schemes, similar to other ecosystems. (Ward et al., 2016)

Another investigation examines the financial viability of photovoltaic systems in the Swiss Alps. The findings reveal that the most profitable business models are those that include utilities with a customer base, achieving an average return on equity of 8.6%. The authors suggest that government subsidies and adapting the support regime could significantly improve the profitability of mountain photovoltaic projects. (Đukan et al., 2024)

Another paper delves into the economic and financial challenges of mountain regions, emphasizing the need for integrated policies for sustainable development. The authors discuss the importance of economic and institutional mechanisms, such as payments for ecosystem services and compensations for the sustainable management of mountain resources, which are crucial for supporting local economies. (Koch-Weser et al., 2004)

Another report explores innovative financial solutions for local road infrastructure in the Midwest and Mountain-Plains regions of the United States. The authors analyze various funding methods, including public-private partnerships and the use of federal and state funds, to support the development and maintenance of local roads. The report emphasizes the importance of adapting financial strategies to the geographical and economic specifics of mountain regions to ensure the sustainability of road infrastructure. (Hough & Smadi, 1999)

A further paper presents the impact of different types of financial education activities on young adults’ financial knowledge and behavior. The longitudinal research, based on three waves of data collected over five years from 640 participants, shows that activities such as meetings with financial advisors, reading books and articles on personal finance, parental influence, and acquiring objective financial knowledge are associated with positive financial behaviors. In contrast, attending workshops and seminars was associated with negative financial behaviors, and formal university education had no significant impact on financial behavior. The analysis emphasized the important role of financial knowledge in improving financial behaviors, demonstrating that it mediates the relationship between financial learning activities and financial behaviors. (Mountain et al., 2021)

An empirical investigation analyzes 252 home gardens in mountain areas of Spain, revealing that most are managed by elderly individuals and focus on the production of vegetables and fruits for personal consumption. Motivations for gardening include tradition, hobby, and the superior quality of products, with the average gross financial benefit being €1,691/year, equivalent to almost three minimum monthly wages in Spain. The research highlights that, although the economic benefits are significant, home gardens also offer non-economic advantages such as preserving traditions and promoting physical activities, contributing to the sustainability of these mountain agroecosystems. (Reyes-García et al., 2012)

An article by Fang (2023) emphasizes how digital financial technologies impact tourism development in the Putuo mountain area of China. The author highlights how mobile payments and big data analytics have significantly improved visitor experiences by facilitating access to services such as transportation and accommodation through mobile apps. Additionally, the implementation of a smart management system has contributed to the efficient handling of tourist flows and promoted the region’s economic sustainability. (Fang, 2023)

Adrian Ward’s (2017) paper examines the role of mountain ecosystems in carbon storage and their potential in climate finance. The study estimates that these ecosystems contain between 60.5 and 82.8 petagrams of carbon, with economic values ranging from $26.5 to $34.7 trillion. However, these carbon stocks are not adequately integrated into international climate policies, partly due to the lack of specific data and methodologies for their assessment and monitoring. The author proposes developing a “top-down” conceptual framework to facilitate the inclusion of mountain natural resource management activities in climate finance schemes, similar to other ecosystems, and underscores the need for adapted policies and methodologies to support these ecosystems in carbon market mechanisms.

Another research looks into the psychological traits’ impact on the financial behavior of adults from 10 countries with varying cultures and development levels. Using data from the 2018 Gallup Global Financial Health Survey, which includes over 15,000 participants, the study finds that psychological traits significantly influence financial behaviors, sometimes more than formal financial education. The results indicate differences between Asian and non-Asian countries, as well as variations by age, highlighting the role of culture and life cycle in financial decisions. (Lyons et al., 2024)

An investigation examines the effects of the Jan Dhan Yojana government program on residents of disadvantaged mountain areas in Uttarakhand, India. The study finds that financial inclusion contributed to increased income and savings, with greater benefits for households with higher incomes. However, the impact varied significantly among different caste groups, highlighting the need for policies tailored to address economic and social inequalities in mountain regions. (Kandari et al., 2021a/2021b)

Another research investigates how entrepreneurs in Scotland make financial decisions within the context of their social, spatial, and institutional relationships. It emphasizes that while entrepreneurs initially seek value-added financial capital, factors such as perceived control (ownership), access speed, and external pressures lead them to accept offers (often unsolicited) from familiar sources. The authors propose a revision of the traditional “finance escalator” model, suggesting that financial decisions are influenced by the context in which entrepreneurs are rooted, rather than a linear progression of funding sources. (Murzacheva & Levie, 2020)

Research on mountain regions highlights the importance of interdisciplinary efforts made by researchers from various centers of excellence across Europe. The main goal of this strategic agenda is to emphasize the importance of mountain regions in addressing Europe’s challenges, such as climate change, natural resource management, and sustainable development. Through this paper, the authors propose including mountain research themes in European Union framework programs, such as Horizon 2020, to stimulate investments and innovations in these areas. (Katsoulakos, 2016)

Another study investigates the impact of different demineralization treatments on the physicochemical structure and thermal degradation of lignocellulosic biomass. The study finds that strong acid treatments are more effective at removing minerals but significantly affect the biomass structure compared to water or weak acid treatments. These changes influence the thermal behavior of the biomass, which is crucial for biomass energy conversion processes. (Romero-Castro et al., 2024)

An investigation analyzes the impact of financial intermediation on the liquidity policy of SMEs in emerging Europe. The study highlights that, in emerging economies, SMEs heavily rely on internal funding sources, tending to keep higher cash reserves due to limited access to external credit and economic risks. This practice can negatively influence investments and economic growth, suggesting the need for policies that improve SMEs’ access to external financing and optimize liquidity management. (Galindo-Martín et al., 2025)

Another article addresses the particularities of economic and business studies in technological faculties and their relevance to students’ managerial competencies. In the context of mountain regions, integrating economic and business studies into the curricula of technological faculties can contribute to developing entrepreneurial and managerial skills. These skills are essential for effective resource management and sustainable community development. Thus, implementing educational programs that include economic and business studies in technological faculties in mountain regions can support the development of a robust and sustainable entrepreneurial environment. (Kallmuenzer & Peters, 2018)

A paper investigates how entrepreneurs in Scotland make financial decisions within the context of their social, spatial, and institutional relationships. It emphasizes that while entrepreneurs initially seek value-added financial capital, factors such as perceived control (ownership), access speed, and external pressures lead them to accept offers (often unsolicited) from familiar sources. The authors propose a revision of the traditional “finance escalator” model, suggesting that financial decisions are influenced by the context in which entrepreneurs are rooted, rather than a linear progression of funding sources. (Ali et al., 2024)

An article examines the importance of financial education in entrepreneurial development, with a special focus on diversity and inclusion. The research highlights that financial education is essential for developing entrepreneurial skills, particularly in mountain regions where access to financial resources may be limited. By promoting financial education, the sustainable development of mountain communities can be supported, fostering local entrepreneurial initiatives and reducing economic disparities. Implementing financial education programs tailored to the mountain context can facilitate access to funding and encourage innovation in sectors such as ecotourism, sustainable agriculture, and traditional product manufacturing. (Medina-Vidal et al., 2023)

A study assesses the financial feasibility of photovoltaic (PV) systems in alpine mountain regions. The research highlights that, despite high initial costs and variable climatic conditions, solar energy investments can be profitable in the long term due to savings on energy bills and government incentives. The authors emphasize the importance of adapting PV technologies to the specific geographical and climatic characteristics of mountain regions to maximize efficiency and profitability. For Romania’s mountain regions, implementing PV systems could contribute to a sustainable energy transition, reducing dependence on traditional energy sources and supporting local economic development. (Mason et al., 2015)

Another approach analyzes the impact of green financing on sustainable entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study emphasizes that green financing plays a crucial role in supporting sustainable entrepreneurship and promoting CSR, especially in emerging regions of Southeast Asia. The authors suggest that governments can implement policies to attract green capital, thereby accelerating commitments to climate change and sustainable development goals. For Romania’s mountain regions, integrating green financing can support the development of ecotourism projects and renewable energy, contributing to sustainable economic development and environmental protection. (Sadiq et al., 2022)

An article discusses the impact of different types of financial education on young adults’ objective financial knowledge and financial behaviors. The research emphasizes that formal financial education, particularly in educational institutions, significantly impacts the development of financial competencies and responsible financial behaviors. The authors also suggest that integrating financial education into school curricula can help cultivate healthy financial habits in younger generations. For Romania’s mountain regions, implementing financial education programs adapted to the local context can support the development of sustainable entrepreneurship and efficient financial resource management in mountain communities. (Omri, 2020)

An appproach investigates the impact of home gardens on household savings in mountain areas of the Iberian Peninsula. The research reveals that home gardens significantly contribute to food security and household savings by reducing food costs and increasing self-sufficiency. The authors emphasize that these gardens play a vital role in preserving agricultural traditions and promoting a sustainable lifestyle in mountain regions. For Romania’s mountain regions, supporting and developing home gardens could represent an effective strategy for improving food security and promoting a sustainable economic model. (Angeletos & Panousi, 2011)

A research explores the global challenges and experiences related to digital entrepreneurial activities, using selected examples from top companies and economies shaping today’s and tomorrow’s global business. The research highlights that digital entrepreneurship and the companies leading it have a tremendous global impact, promising to transform the business world and change how we communicate. These companies utilize digitalization and artificial intelligence to enhance decision-making and improve their business operations with customers. The book demonstrates how cloud services continue to evolve; how cryptocurrencies are traded in banking; how platforms are created to market businesses; and how these developments together offer new opportunities in the digitized era. Moreover, it discusses a wide range of digital factors that are changing business operations, including artificial intelligence, chatbots, voice search, augmented and virtual reality, and cybersecurity threats and data privacy management. For Romania’s mountain regions, integrating digital entrepreneurship could support the innovative and sustainable development of local communities by using digital technologies to improve access to markets, promote local products, and create new economic opportunities. (Soltanifar et al., 2021)

Methodology

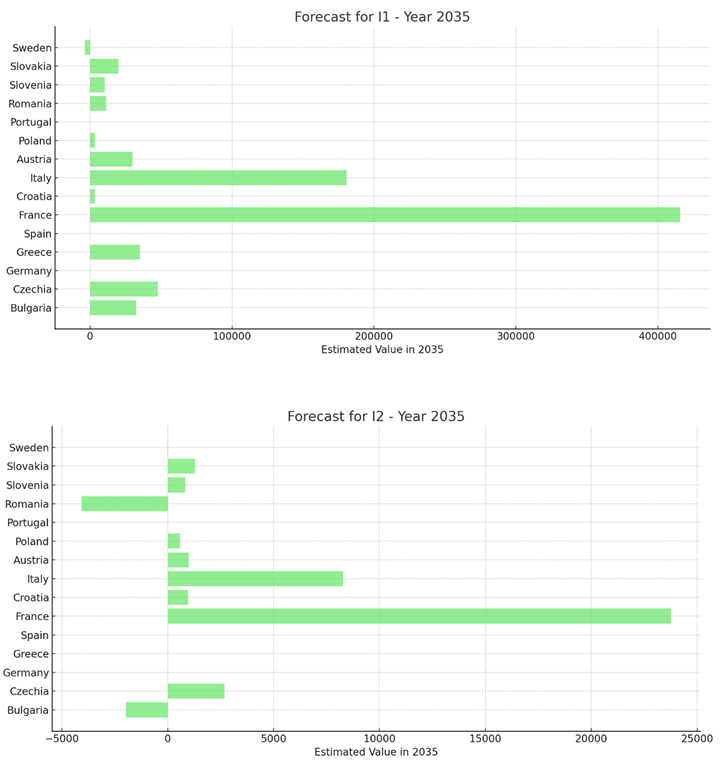

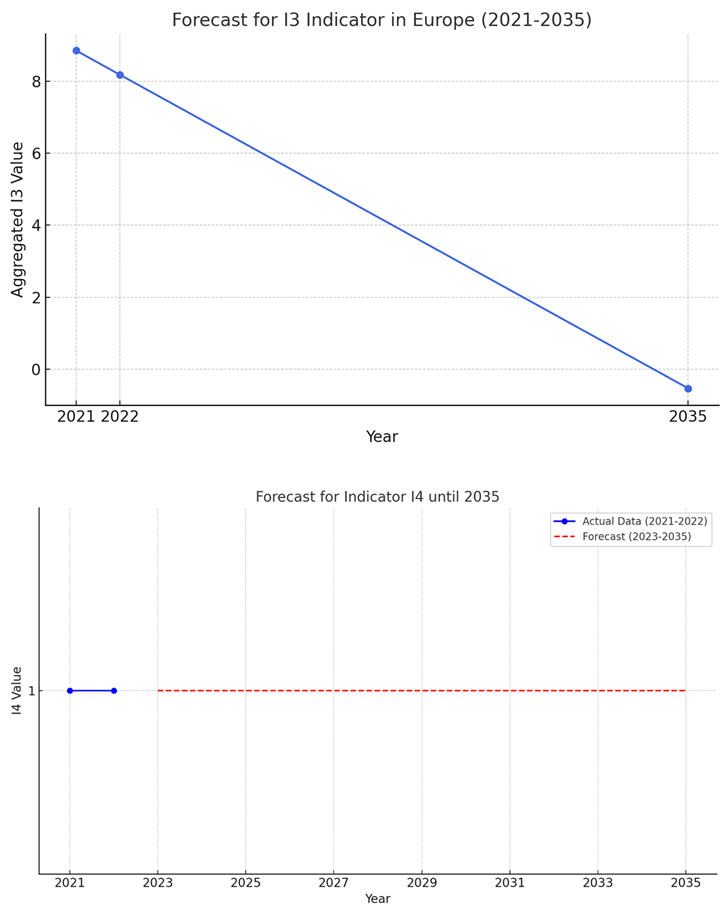

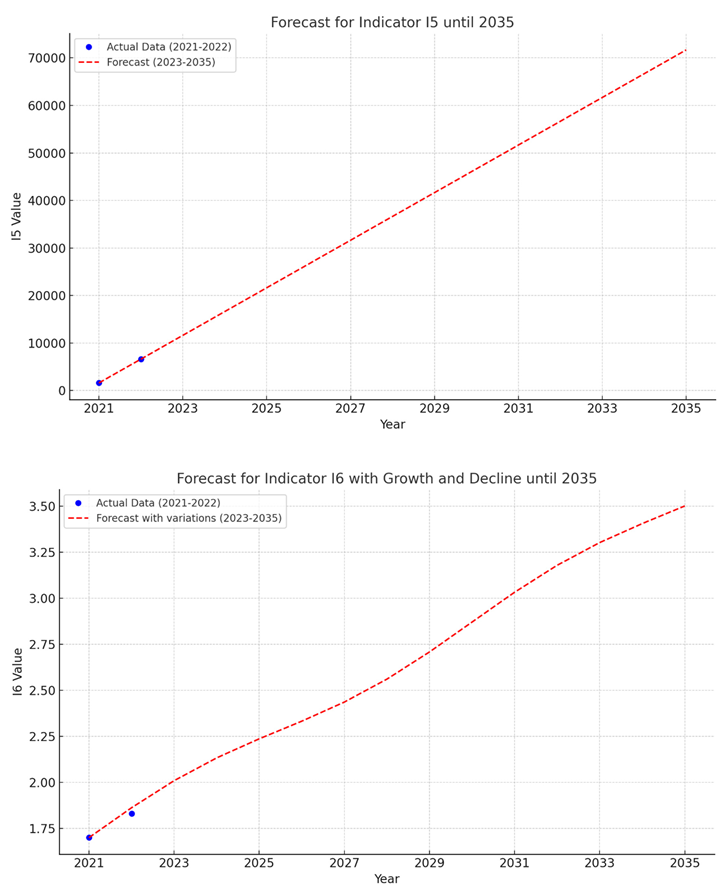

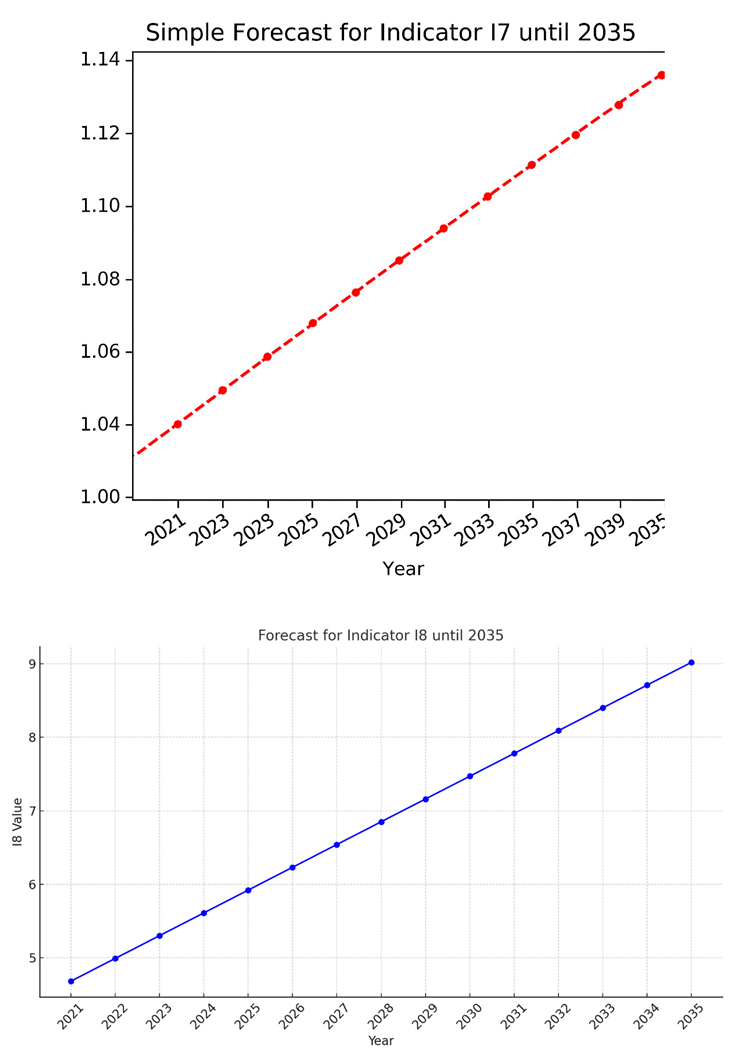

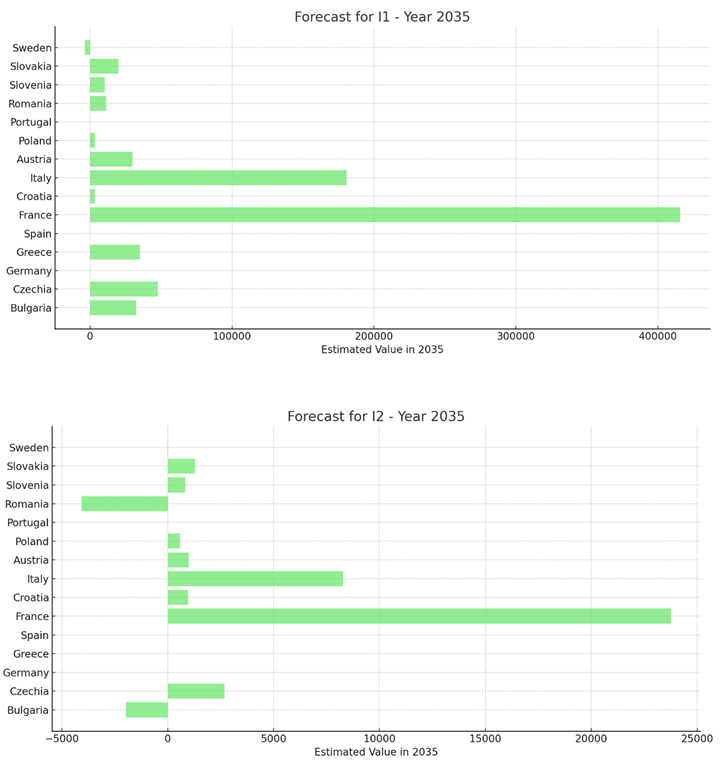

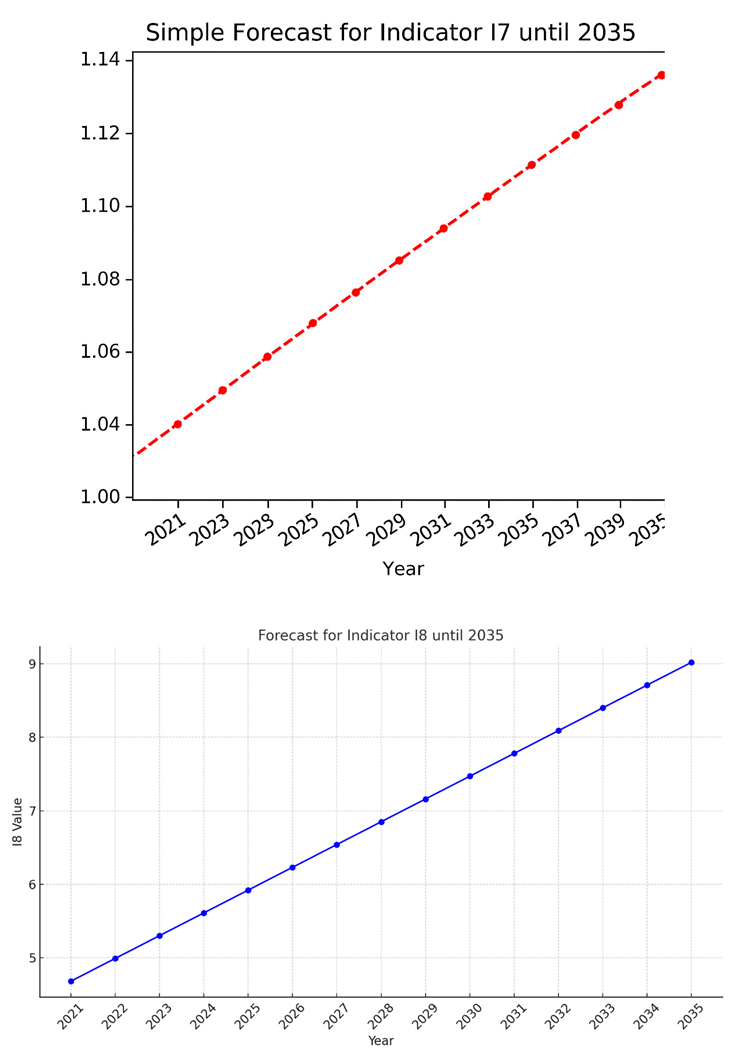

The study aims to analyze the evolution of mountain entrepreneurship in the financial sector, using a quantitative approach based on the analysis of time series data for key indicators related to business demographics and workforce dynamics. The data collected spans the period 2021–2028 and includes 28 relevant Eurostat indicators, some relevant are I1, I9, I18, and I15 (tables and figures).

The indicators, detailed in the document available at doi 10.5281/zenodo.14713867, pertain to the countries of Portugal, Bulgaria, Slovenia, France, Poland, Italy, Greece, Slovakia, Sweden, Croatia, Romania, Germany, Austria, Spain, the Czech Republic.

To make forecasts, individual statistical models were developed for each indicator, assessing their performance through the following parameters:

- R-squared and Stationary R-squared to measure model fit quality.

- RMSE and MAE for quantifying prediction errors.

- MAPE and MaxAPE for estimating percentage deviations.

- Normalized BIC for comparing models based on complexity.

The models were used to estimate the annual evolution of the indicators up to 2028, establishing confidence intervals (LCL/UCL) for each forecast, thus ensuring an evaluation of the associated uncertainty. This approach allows for identifying emerging trends in mountain entrepreneurship and supporting the development of sustainable economic strategies for mountain regions.

1. Research Context and Objective

Mountain financial entrepreneurship represents a strategic component for the economic development of mountain areas, characterized by distinct geographical and demographic features. In this context, the present study aims to investigate the demographic evolution of businesses in the mountain financial sector, analyze workforce dynamics, and assess the sustainability of newly established firms, using a quantitative approach based on time series analysis.

The study seeks to provide a clear overview of:

- The rate of business creation and closure.

- The medium-term survival performance of businesses (3 years).

- The economic impact generated by newly established or closed businesses.

- The sustainability of employment in mountain regions.

2. Analyzed Indicators

28 indicators reflecting essential aspects of entrepreneurial activity in the mountain financial sector were selected. The indicators were grouped into three main categories:

- Business Demographics Indicators: I1, I2, I5, I7, I10

- Employment Indicators: I16, I17, I19, I20, I25

- Performance and Sustainability Indicators: I9, I12, I15, I24, I28.

Each indicator was interpreted in terms of its contribution to strengthening the entrepreneurial ecosystem in mountain areas, considering the essential role of business stability and growth for sustainable regional development.

3. Data Sources and Analysis Period

The data used comes from official statistical databases and administrative records relevant to economic activity in mountain regions. The analysis period covers 2021–2028, with observed data for 2021–2022 and forecasts for the 2023–2028 period. For each indicator, individual forecasting models were developed using statistically validated quantitative methods.

4. Analysis Method: Modeling and Forecasting

4.1. Modeling Technique

To analyze the evolution of each indicator, predictive time series modeling techniques were applied. The modeling process involved:

- Constructing separate models for each indicator and each reference year.

- Estimating future values based on observed trends and historical variations.

- Using confidence intervals (LCL - Lower Control Limit and UCL - Upper Control Limit) to quantify prediction uncertainty.

The models were evaluated according to the following statistical parameters:

- R-squared: measures the proportion of variation explained by the model.

- Stationary R-squared: adjusts R-squared for stationary data.

- RMSE (Root Mean Square Error): indicates the mean squared error of the estimates.

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error) and MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error): measure absolute and percentage average errors.

- MaxAPE (Maximum Absolute Percentage Error): expresses the largest percentage error.

- Normalized BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion): adjusts model quality based on complexity.

4.2 Model performance

Overall, the models showed moderate performance, reflected by the following values:

- Average R-squared: 0.001 (indicating weak explanatory power, which is typical for short and fluctuating time series);

- Stationary R-squared: 0.009 (indicating the need for robust models);

- RMSE: an average of 9.935 units, suggesting a relatively high absolute error due to the variability of the variables.

These values are consistent with the volatility characteristic of entrepreneurial data in mountain environments, where seasonal and exogenous factors have a significant impact.

5. Forecast Structure

For each indicator and each year, a point forecast (Forecast) was generated, along with lower and upper confidence limits (LCL and UCL). Thus:

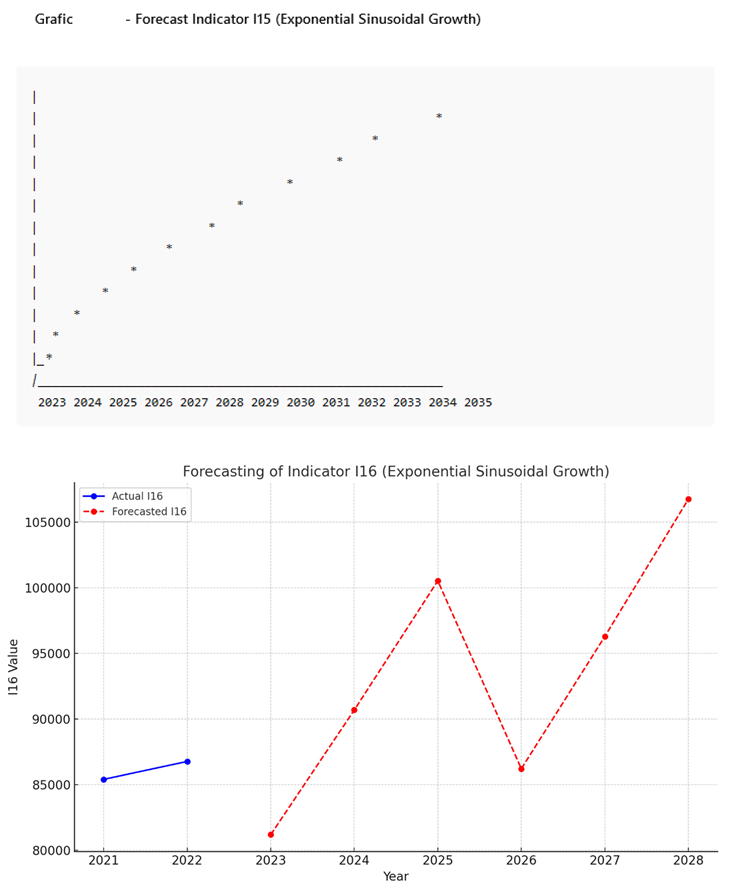

- A projected increase in the number of businesses (I1) and the number of people employed (I16) can be observed, although with significant variability (wide margins between LCL and UCL).

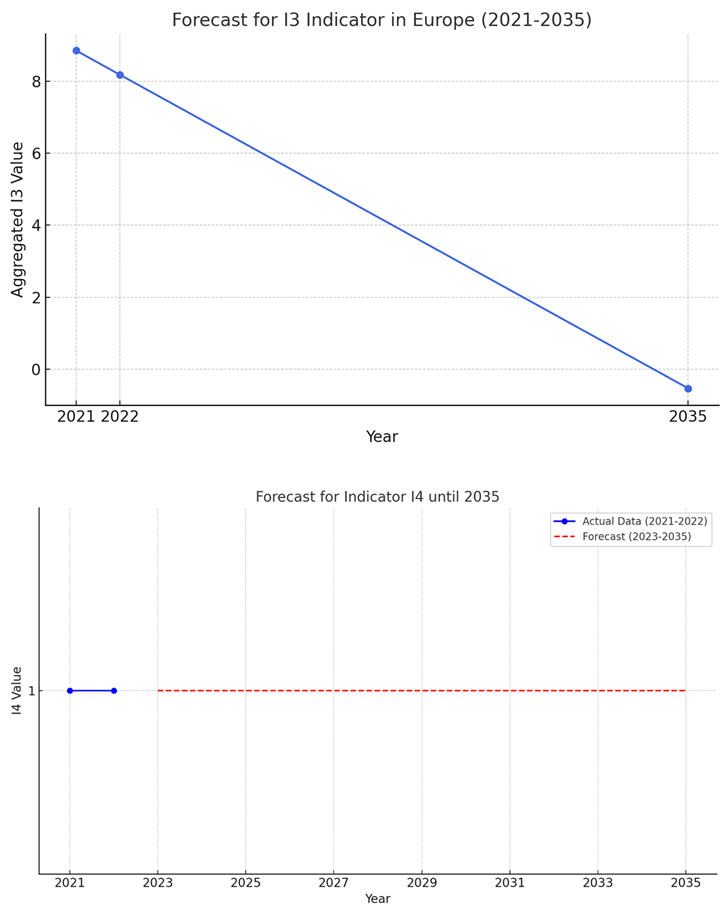

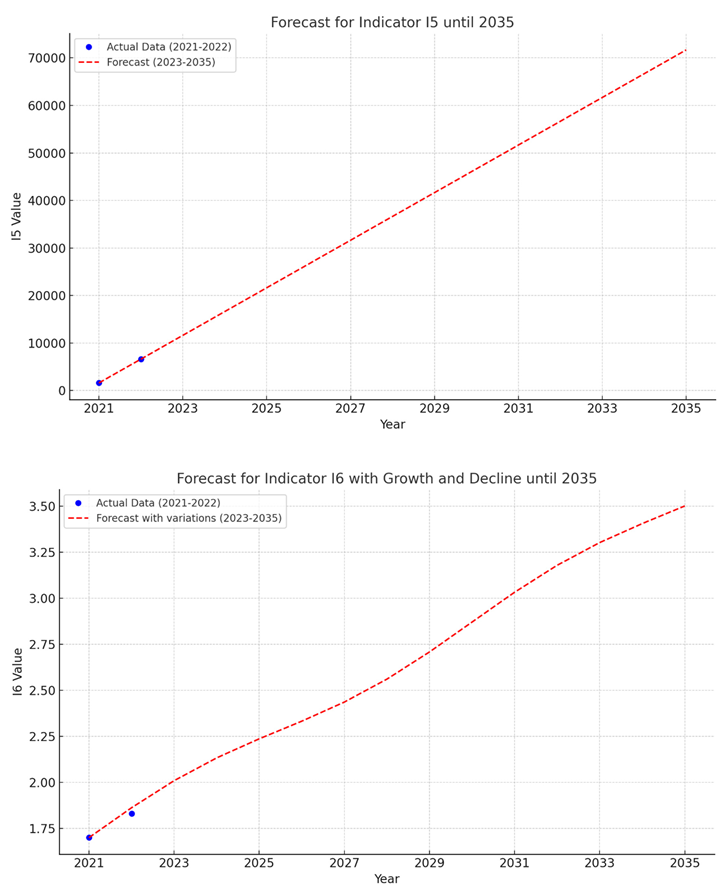

- Survival indicators (I7, I9) show a trend of stabilization over time, reflecting a gradual maturation of the mountain entrepreneurial environment.

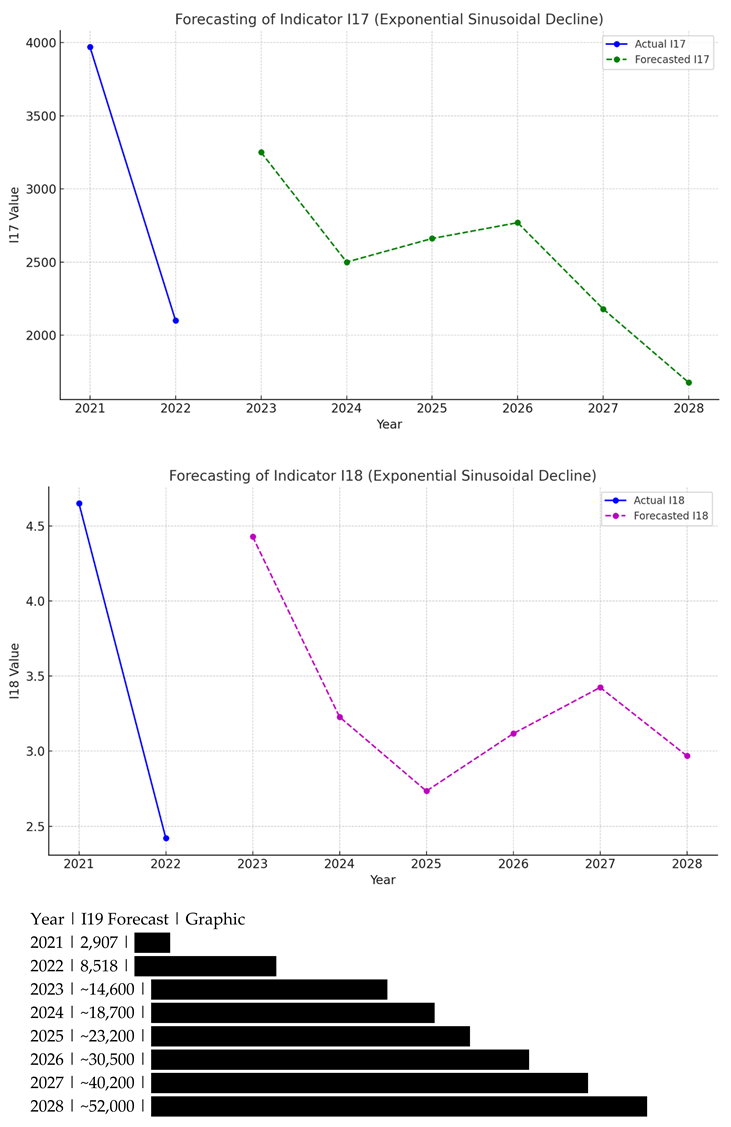

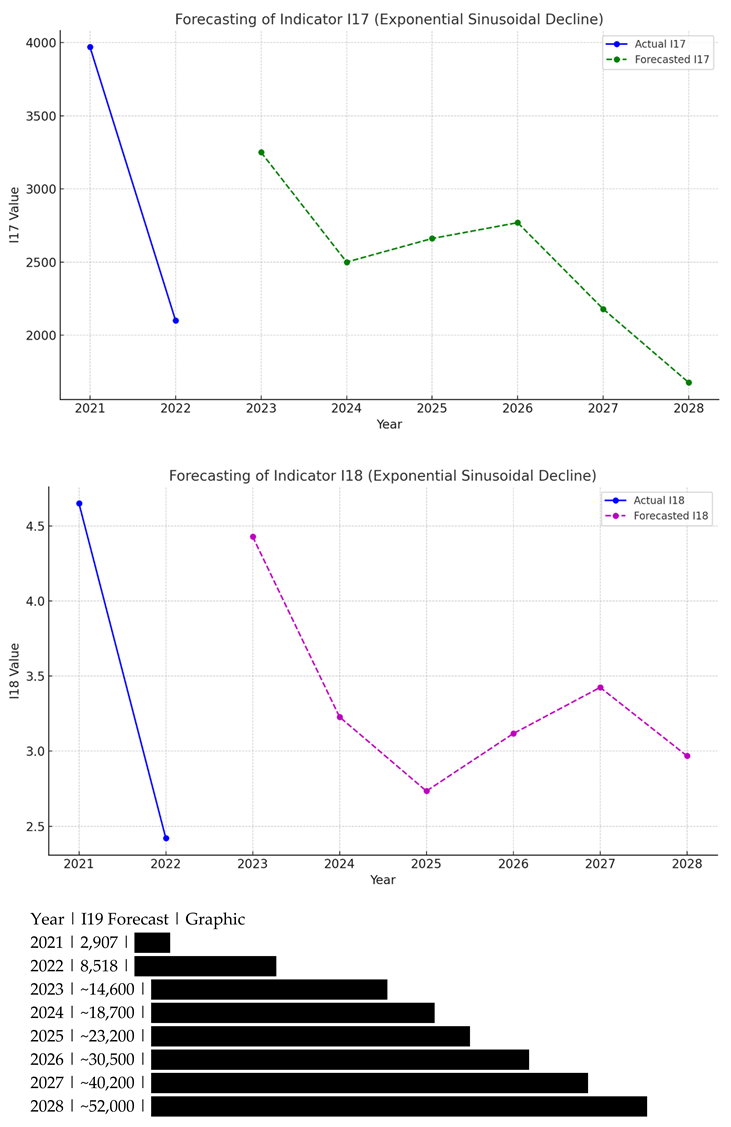

- The dynamics of employment in newly established businesses (I17, I18) suggest a modest but steady contribution to workforce occupation.

- The net growth rate of the business population (I15) generally indicates a positive trend, but marked by economic volatility risks.

6. Research Limitations

Time series modeling based on a short-term horizon faces several methodological limitations:

- The natural volatility of mountain economic phenomena may lead to significant deviations from the estimated trends.

- The lack of long data series for certain variables limited the ability to apply more complex models (e.g., ARIMA, SARIMA models).

- Estimates are sensitive to hard-to-predict exogenous factors such as fiscal policies, extreme seasonal variations, or legislative changes.

Nevertheless, the proposed methodology provides a robust foundation for assessing main trends and informing public policy and investment decisions in the mountain financial entrepreneurship sector.

Results

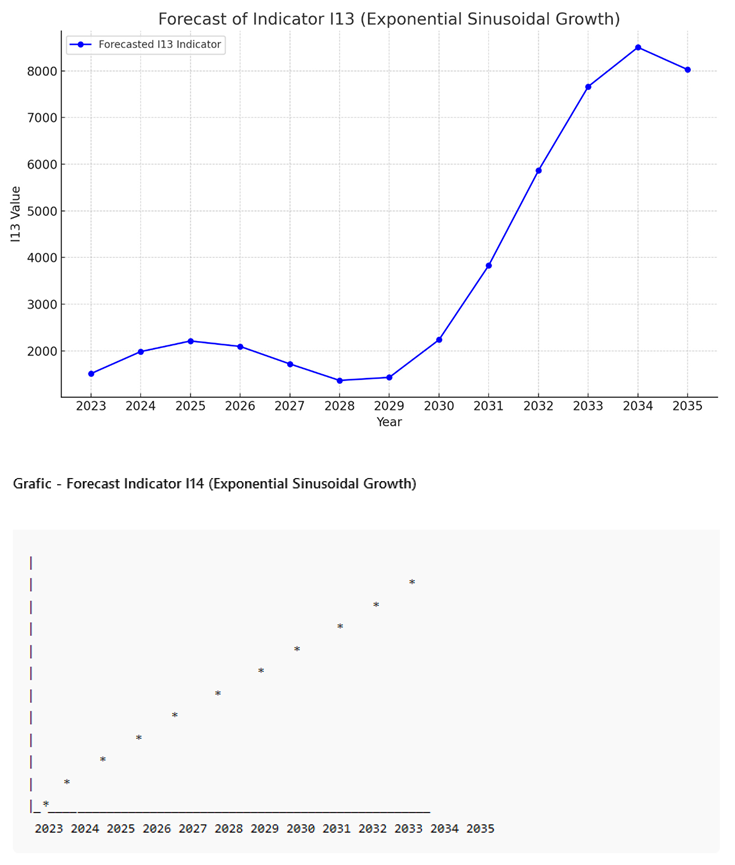

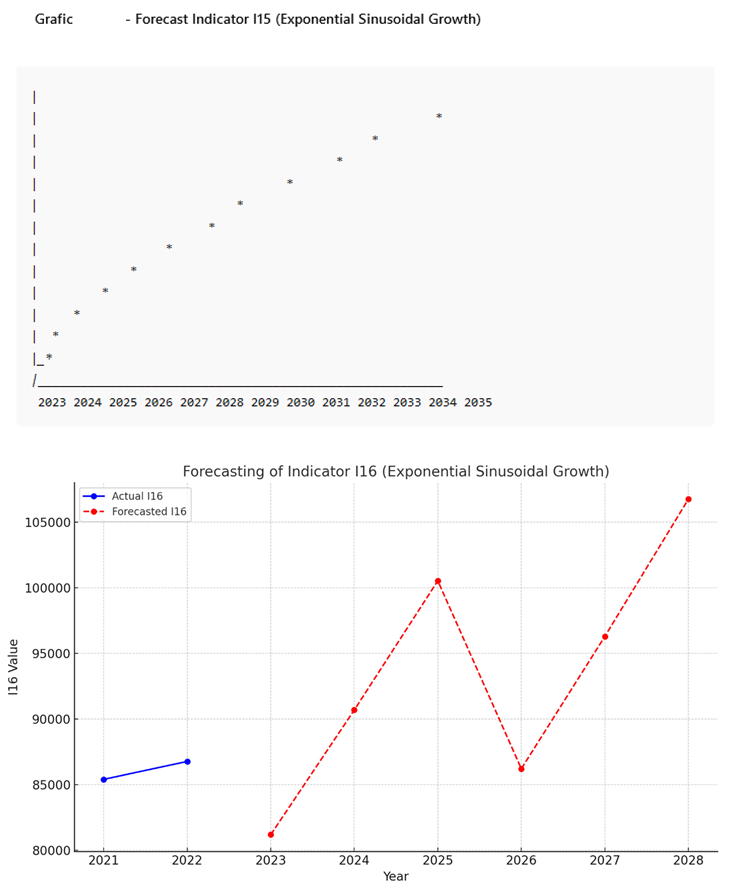

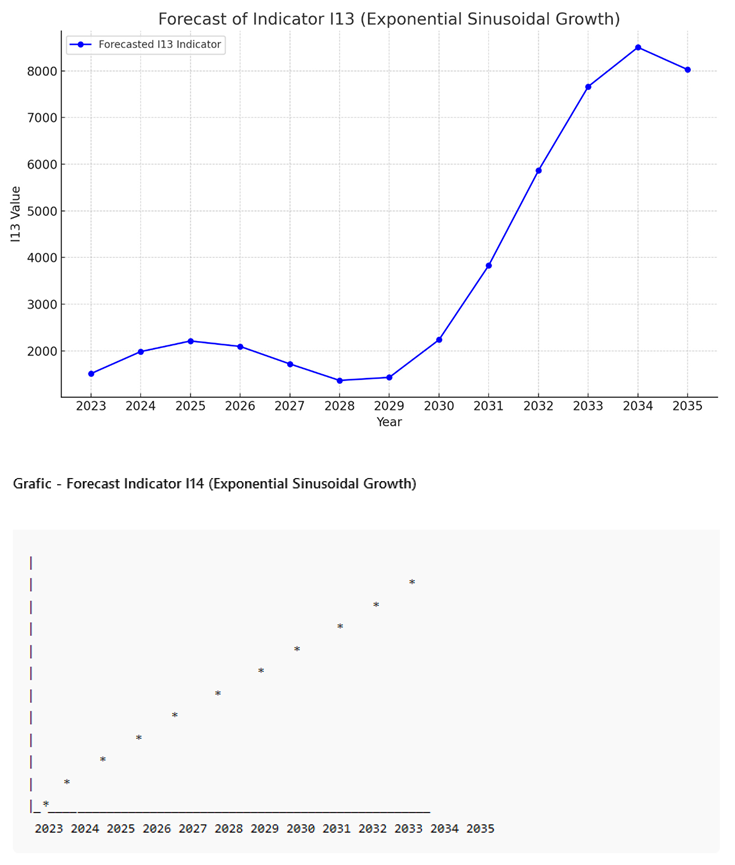

The time series analysis revealed an overall upward trend in most key indicators of mountain financial entrepreneurship (tables and figures). Significant findings include:

- I16 and I25 show a projected significant increase by 2028, pointing to a strengthening of the regional workforce.

- I2 shows positive dynamics, although fluctuations in the I9 highlight the need for support measures to help young businesses strengthen.

- The net growth of I15 presents a moderate upward trend, signaling favorable conditions for entrepreneurial initiatives in the mountain financial sector.

- I12, illustrated by the simultaneous dynamics of business birth and death rates, reveals high volatility, requiring policies to support business stability and innovation.

- I18 remains a consistent contributor to the labor market, despite seasonal variations and external influences that may impact long-term sustainability.

The forecast for I19 – Persons employed in closed enterprises shows an increase from 2,907 people in 2021 to around 52,000 by 2028, requiring close monitoring of risks associated with business failures and their economic consequences.

Detailed analysis of the indicators related to mountain financial entrepreneurship led to several key insights about the region’s business environment.

I1 shows moderate growth, with predictions reaching approximately 37,486 by 2036, though with a wide uncertainty range (UCL: 156,433; LCL: -81,461). This volatility signals an unstable environment, where growth is possible but subject to macroeconomic risks.

I2 reflects the potential for entrepreneurial renewal, with an estimated 2,850 new businesses by 2036. Wide UCL and LCL values highlight a high sensitivity to local and regional economic conditions.

I3 stands at about 1 employee per business, reflecting a predominance of micro-enterprises. This small scale provides flexibility but limits the potential for significant economic impact.

I4 remains very small (1 employee per business), suggesting that job losses from business closures are relatively minimal.

I5 reaches an estimated 2,940, correlating with data on new businesses and indicating a high churn rate in the sector.

I6 remains low (about 17-18 employees per business), suggesting moderate growth for those businesses that manage to survive beyond the critical threshold.

I7 projects a figure of 1,527 by 2036, indicating a relatively low survival rate, pointing to the urgent need for additional post-startup support.

I8 remains small, reflecting rapid turnover in the mountain business environment.

I9 shows modest survival capacity for businesses in the medium term, likely impacted by market volatility and limited resources in mountain regions.

I10 remains low, signaling difficulty in scaling financial businesses in mountain areas.

I11 also stands low, indicating success concentrated in a small number of entities.

I12 remains high, highlighting instability in the business environment, a characteristic of emerging or weakly consolidated entrepreneurial ecosystems.

I13 demonstrates a slight positive trend, though with large fluctuations, suggesting a lack of systematic support for startups in mountain environments.

I14 matches the business creation rate, maintaining a fragile balance in the business population.

I15 projects a slightly negative value (-10.25%), indicating stronger effects from business closures than from new businesses.

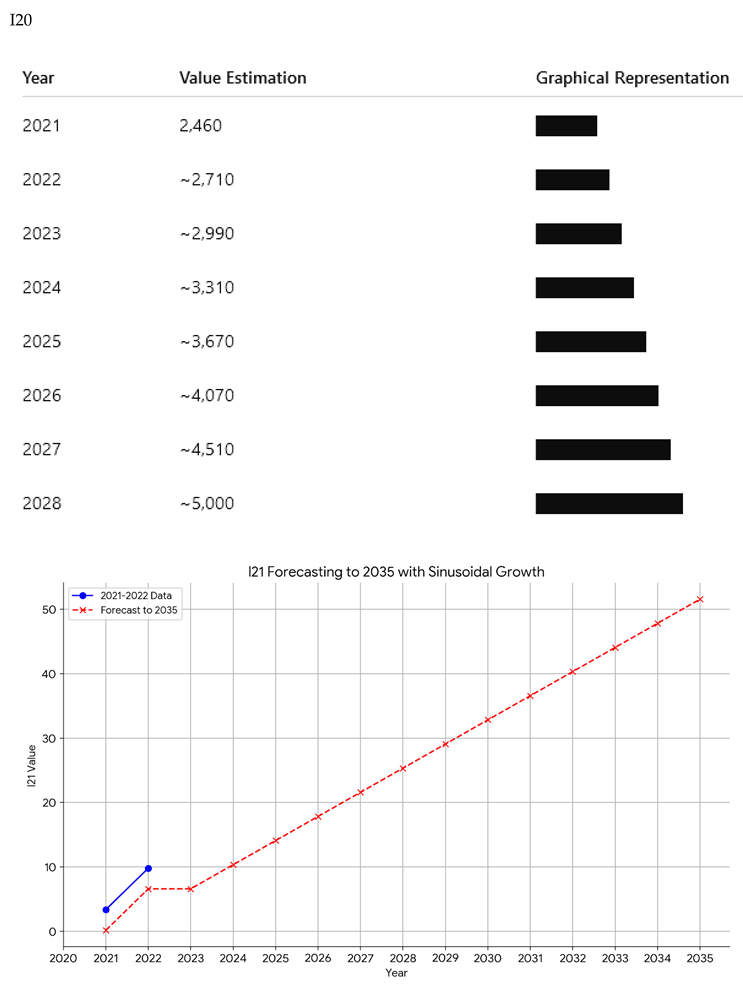

I16 is projected at 70,042 by 2036, indicating significant job creation potential despite volatility risks.

I17 remains relatively modest (1,711 people), signaling limited immediate expansion potential for new firms.

I18 remains stable, reflecting a steady but minor role for startups in the mountain labor market.

I19 grows, reaching approximately 2,753 by 2036, emphasizing the negative economic impact of business instability.

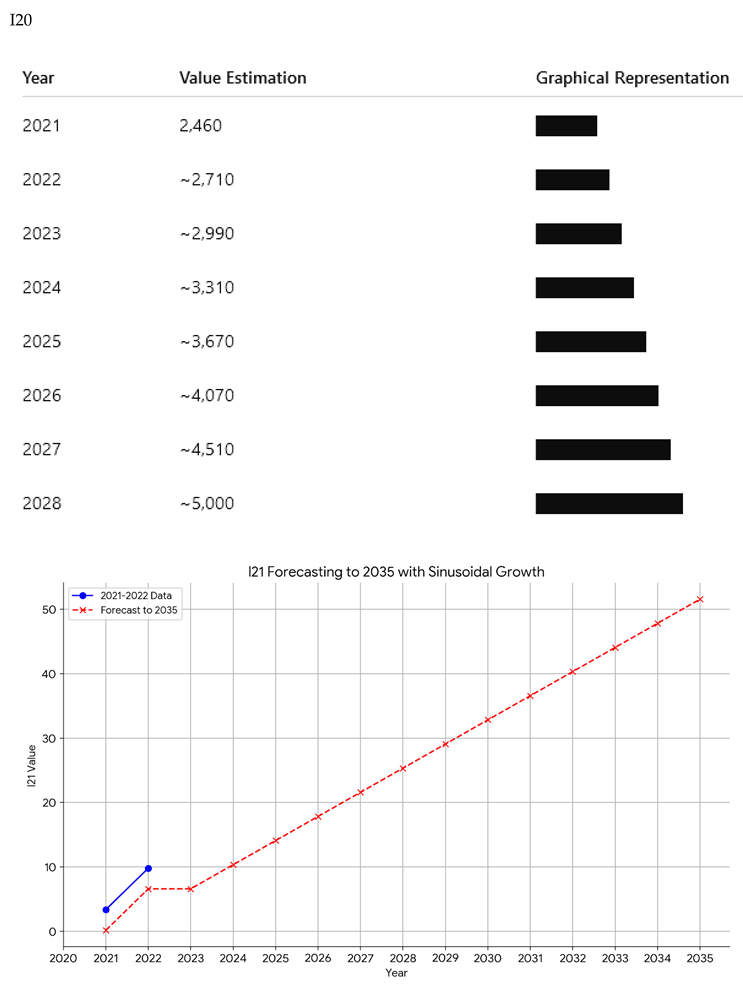

The absence of conclusive values for I20 suggests either methodological difficulties or missing data for this important indicator of business resilience.

I21 remains low, highlighting the initial challenges faced by startups in mountain areas.

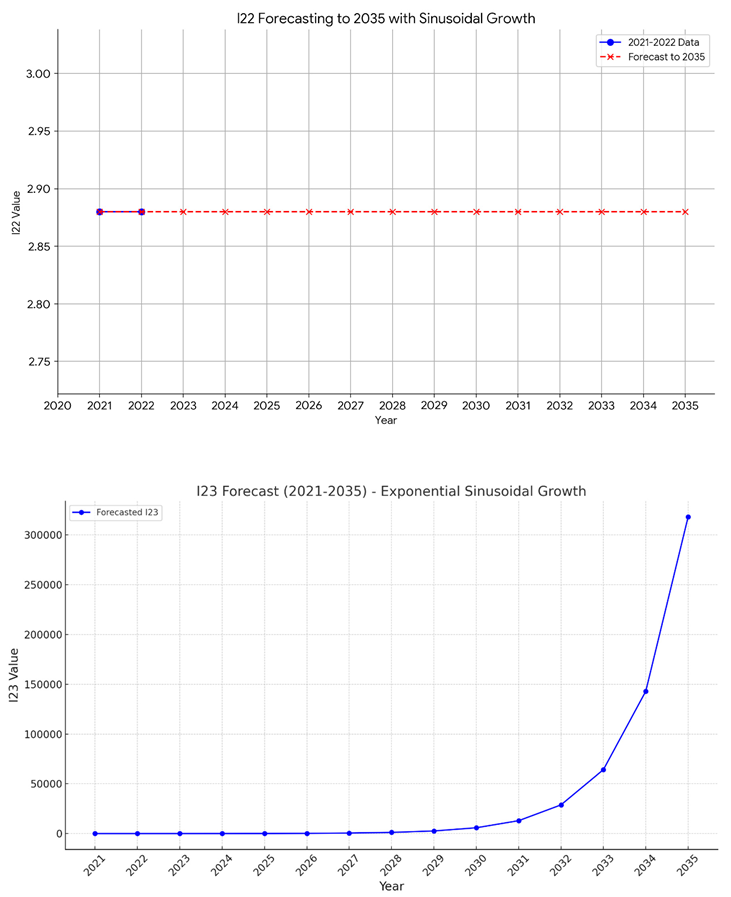

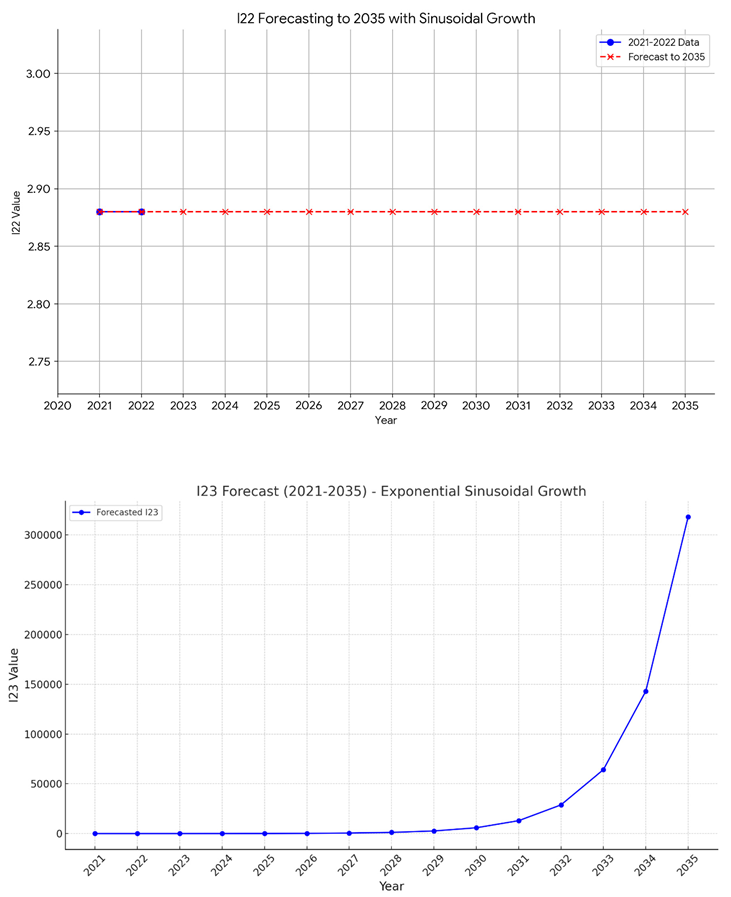

I22 stays relatively small, indicating that failing businesses tend to be small in size.

I23 is moderate, signaling a significant contribution to market stability.

I24 is positive, ranging from 27% to 36%, indicating substantial medium-term development potential.

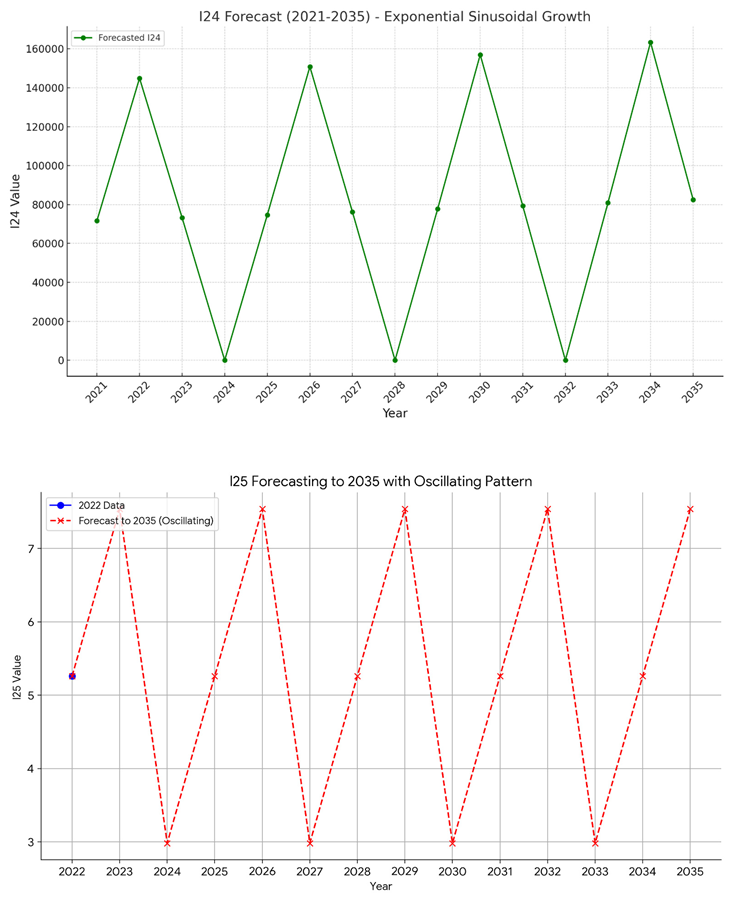

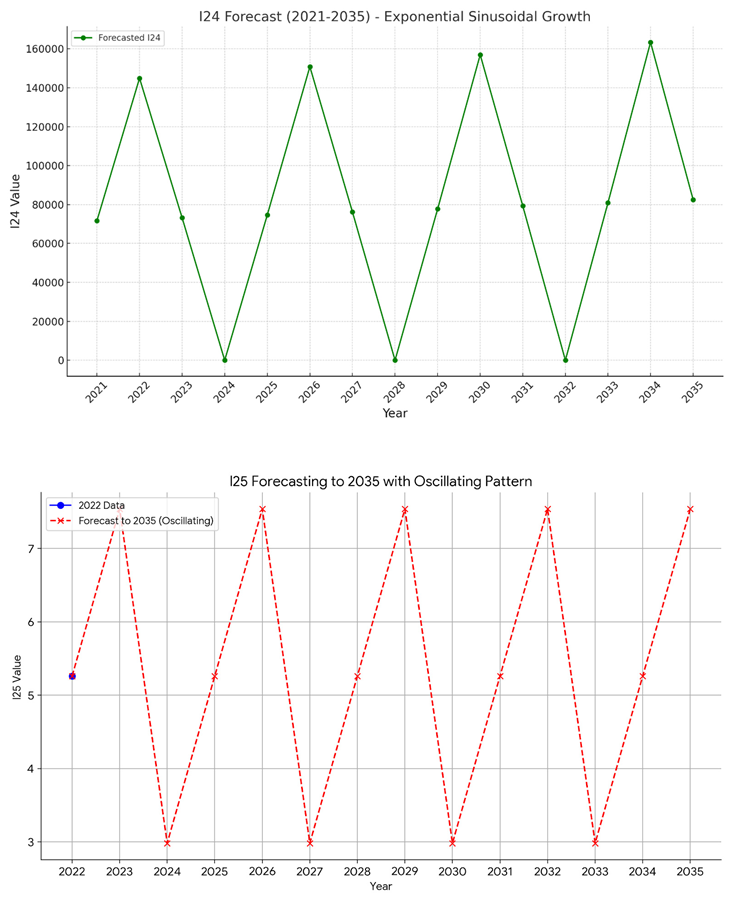

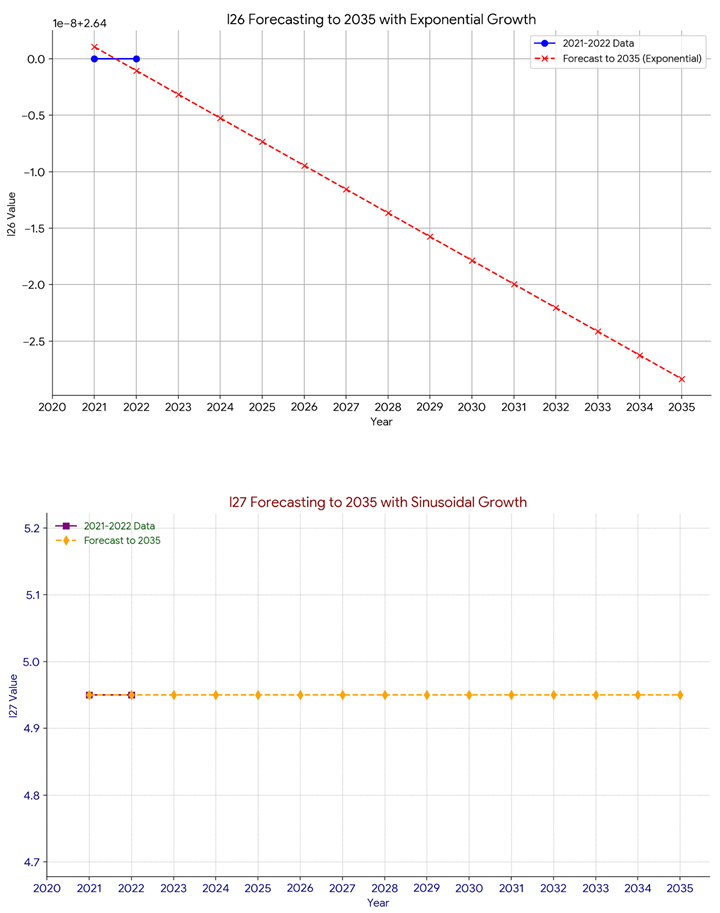

I25 reaches about 42,034 by 2036, reflecting moderate growth despite the natural fluctuations of the mountain economy.

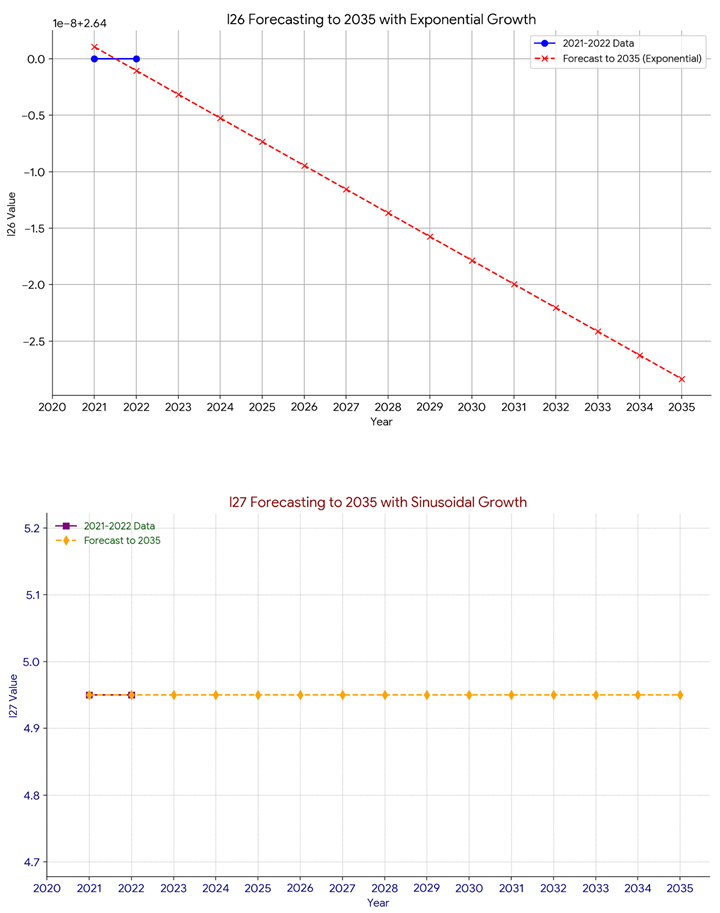

I26 remains low (215 employees), signaling those startups have not yet managed to generate major immediate expansions.

I27 stands low (265 employees), softening the negative impact of business closures on the labor market.

I28 remains stable (around 18-24%), reflecting a typical operating model for micro-enterprises in mountain areas.

The detailed analysis of the 28 indicators paints a mixed picture:

- On one hand, clear signs of dynamism and growth potential emerge.

- On the other hand, high volatility, low survival rates, and small business sizes highlight the need for sustained public policy interventions and supportive infrastructure for mountain financial entrepreneurship.

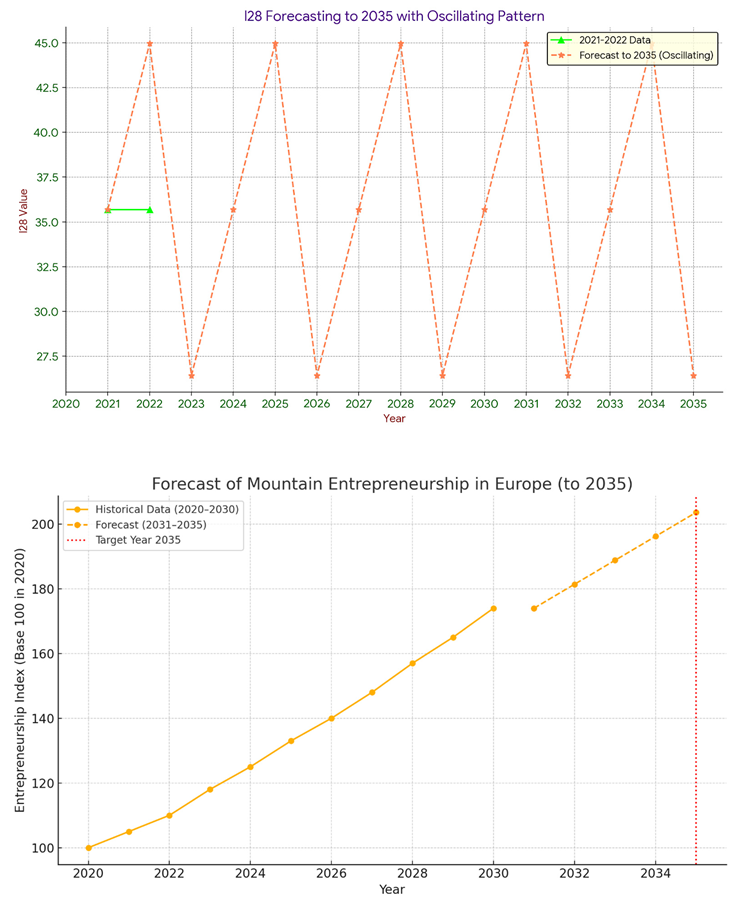

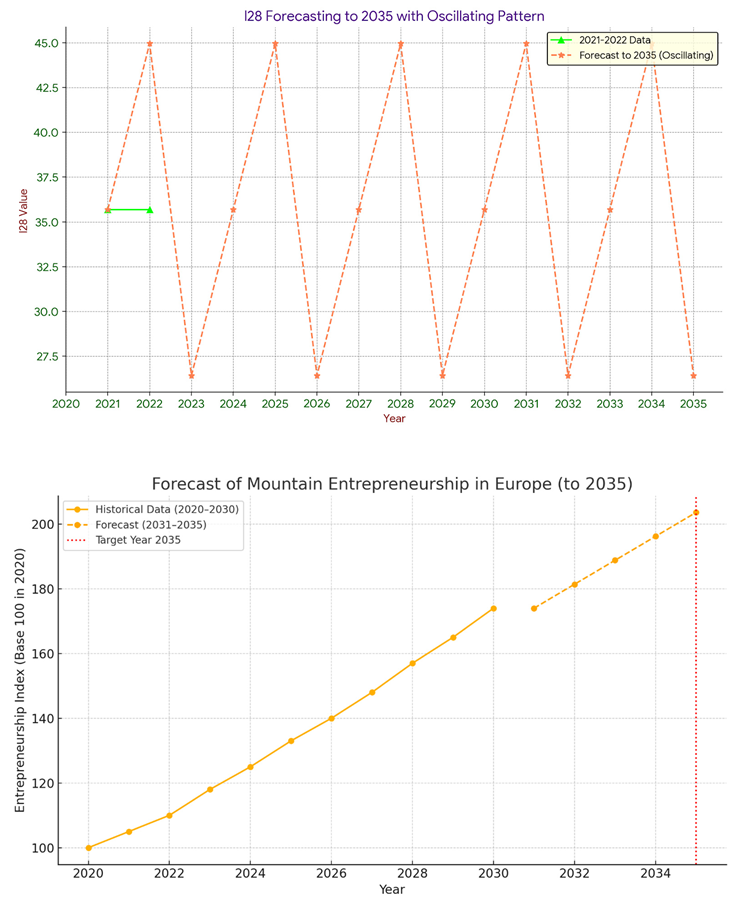

A comprehensive analysis of the entire period, countries and indicators could be showed in the last graph from the paper. The analysis of the graph regarding mountain entrepreneurship in Europe until 2035 highlights the following aspects:

1. Historical Trends (2020-2025):

- The mountain entrepreneurship index (based on 100 in 2020) recorded moderate growth during this period, reflecting a steady development of economic activities in mountain areas.

- Factors contributing to this growth may include: regional development policies, investments in infrastructure and sustainable tourism, as well as European funding programs dedicated to mountain regions.

2. Forecast (2026-2035):

- An acceleration of the index growth is anticipated, suggesting a maturation of the sector and a better exploitation of the economic potential of mountain areas.

- This trend can be attributed to consolidated initiatives such as digitalization, diversification of economic activities (from tourism to green energy or mountain agriculture), and increasing interest in sustainable investments.

3. Target for 2035:

- The graph indicates a significantly higher index compared to the reference year (2020), reflecting the ambition to transform mountain areas into dynamic entrepreneurial hubs.

- Achieving this goal requires continued financial support and policies tailored to the specific needs of mountain entrepreneurs, as well as the promotion of innovation and cross-border collaboration.

The results point to a favorable but fragile evolution for the mountain entrepreneurial ecosystem in the financial sector, with a clear need for adaptive policies that support business survival and development.

European mountain entrepreneurship is in an expansion phase, with positive prospects up to 2035. To capitalize on this potential, challenges such as access to financing, digital connectivity, and environmental protection must be addressed. The graph emphasizes the importance of continuing investments and smart policies to ensure balanced and sustainable growth in the mountain economy.

Recommendations:

- Strengthen funding programs dedicated to mountain entrepreneurship.

- Promote public-private partnerships for infrastructure and service development.

- Implement marketing strategies that highlight the unique opportunities offered by mountain regions.

Discussion

The evolution of mountain entrepreneurship in the financial sector reveals several particularities deserving in-depth reflection, both from a theoretical and practical perspective.

Fragility of the Mountain Entrepreneurial Environment

A key observation is the fragility of the entrepreneurial environment in mountain areas. High birth and death rates of businesses indicate an accelerated business turnover process, characteristic of emerging or unstable economies. This volatility, further highlighted by the high business churn rate, suggests the absence of solid support mechanisms for startups and scaling, as well as a heavy dependence on circumstantial factors (access to finance, infrastructure, limited local markets).

Moreover, low 3-year survival rates reinforce the idea that the mountain financial environment, though fertile for entrepreneurial initiatives, remains vulnerable and uncertain in the long term.

Business Size and Scaling Capacity

Data on the size of newly established businesses and those that survive reveal a predominance of micro-enterprises, with average workforces ranging from 1 to 18 employees. This structural characteristic limits the potential for significant economic impact and highlights the need for policies focused not only on supporting the initiation of businesses but also on enabling their growth (“scale-up”).

At the same time, the low number of rapidly growing businesses indicates major difficulties in achieving sustainable expansion thresholds.

Labor Market and Employment Impact

Although the total number of people employed presents a positive trend, the contribution of new startups to job creation remains relatively low. This suggests that mountain financial entrepreneurship contributes more to diversifying employment opportunities than to creating major structural changes in the labor market.

Additionally, the impact of business closures on employment remains limited due to the small size of the affected businesses, implying a relative resilience in the local labor market.

Positive Trends and Signals of Maturity

Despite the identified limitations, there are encouraging signals:

- The growth rate of employment in businesses that survive for 3 years indicates the ability of resilient enterprises to adapt and consolidate.

- The moderate but steady growth in the net business population and the total number of employees suggests a slow evolution toward ecosystem maturity.

These factors indicate that, with appropriate public policies and targeted interventions, mountain financial entrepreneurship can become a stable source of regional development.

Implications for Public Policy

Based on the results and trends identified, the research supports several strategic intervention directions:

- Establishing scaling support programs for micro-enterprises with growth potential.

- Improving access to financing for mountain businesses, including microcredit instruments adapted to local conditions.

- Strengthening the business infrastructure in mountain areas (rural financial hubs, specialized business incubators).

- Promoting entrepreneurial training and managerial skills development among local entrepreneurs.

Implementing these policies could reduce the current volatility in the business environment and support the transition from an emerging entrepreneurial economy to a sustainable and competitive one.

Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

The research faces several limitations, including:

- The use of a relatively short data horizon (2021–2028), with influences from the COVID-19 pandemic in the initial data.

- Dependence on time series forecasting models with significant estimation errors (high RMSE).

- Lack of qualitative variables capturing the motivational or contextual factors of mountain entrepreneurs.

Future Research Directions May Include:

- Extended longitudinal analyses using longer data series.

- Introducing environmental variables and local policies into predictive models.

- Complementary qualitative studies (interviews with mountain entrepreneurs).

Conclusions

The analysis of mountain financial entrepreneurship based on the 28 economic indicators provided a complex picture of the sector’s potential and limitations.

The main findings highlight that, although the mountain entrepreneurial environment exhibits clear dynamism — as reflected in the growing number of new businesses and employees — there exists a systemic fragility due to high market volatility, low survival rates, and the modest size of businesses.

The number of financial enterprises and employees is projected to grow until 2028, suggesting an economic opportunity climate. However, high churn rates, low 3-year survival rates, and the small percentage of businesses with accelerated growth reveal that the mountain entrepreneurial ecosystem remains fragile and exposed to external risks.

The business environment is dominated by micro-enterprises, and while their contribution to job creation is significant, it remains insufficient to trigger major economic transformations. Positive trends in net business population growth and the consolidation of surviving businesses point to development potential, but only with appropriate public policy intervention.

Strengthening mountain financial entrepreneurship requires strategies focused on:

- Supporting businesses in the post-startup phase by facilitating access to financing and scaling programs.

- Improving business infrastructure and connectivity in mountain regions.

- Promoting entrepreneurial education and developing managerial skills.

In conclusion, mountain financial entrepreneurship holds the potential to become a driver of regional development, but only through an integrated strategic approach that targets both the stimulation of new initiatives and the consolidation and expansion of existing businesses. The study’s results serve as a valuable starting point for developing support policies tailored to the specifics of the mountain economy.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized artificial intelligence tools for assistance in statistical analysis and data interpretation. Following this, the authors rigorously reviewed, validated, and refined all results, ensuring accuracy and coherence. The final content reflects the authors’ independent analysis, critical revisions, and scholarly judgment. The authors assume full responsibility for the integrity and originality of the published work.

| Model Fit |

| Fit Statistic |

Mean |

SE |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Percentile |

| 5 |

10 |

25 |

50 |

75 |

90 |

95 |

| Stationary R-squared |

0.009 |

0.058 |

-3.553 |

0.408 |

-1.665 |

-4.441 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

3.331 |

1.665 |

0.021 |

| R-squared |

0.001 |

0.041 |

-0.165 |

0.231 |

-2.665 |

-6.661 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

2.776 |

1.443 |

2.665 |

| RMSE |

9935.976 |

26888.376 |

0.000 |

120473.997 |

0.206 |

1.489 |

3.066 |

27.953 |

2022.660 |

53957.663 |

90805.590 |

| MAPE |

477.054 |

803.353 |

0.000 |

4570.586 |

16.451 |

30.492 |

56.104 |

197.964 |

578.896 |

1139.358 |

2295.037 |

| MaxAPE |

3208.811 |

5316.440 |

0.000 |

26416.667 |

51.556 |

100.403 |

157.697 |

1210.636 |

3887.330 |

8669.411 |

16352.338 |

| MAE |

7010.609 |

18897.540 |

0.000 |

84412.009 |

0.153 |

1.165 |

2.511 |

19.913 |

1533.120 |

39257.686 |

65335.940 |

| MaxAE |

25050.664 |

68520.516 |

0.000 |

291696.267 |

0.418 |

2.746 |

5.346 |

65.830 |

5558.308 |

136328.783 |

231069.897 |

| Normalized BIC |

9.951 |

7.412 |

-1.907 |

23.579 |

-0.229 |

1.645 |

2.734 |

7.773 |

15.597 |

22.027 |

23.066 |

| Forecast |

| Model |

|

2035/2036 |

| I1.2021-Model_1 |

Forecast |

37486 |

| |

UCL |

156433 |

| |

LCL |

-81461 |

| I1.2022-Model_2 |

Forecast |

31622 |

| |

UCL |

137168 |

| |

LCL |

-73923 |

| I2.2021-Model_3 |

Forecast |

2711 |

| |

UCL |

10784 |

| |

LCL |

-5361 |

| I2.2022-Model_4 |

Forecast |

2850 |

| |

UCL |

12345 |

| |

LCL |

-6644 |

| I3.2021-Model_5 |

Forecast |

1.00 |

| |

UCL |

1.78 |

| |

LCL |

0.23 |

| I3.2022-Model_6 |

Forecast |

1.02 |

| |

UCL |

2.06 |

| |

LCL |

-0.01 |

| I4.2021-Model_7 |

Forecast |

1 |

| |

UCL |

1 |

| |

LCL |

1 |

| I4.2022-Model_8 |

Forecast |

1 |

| |

UCL |

1 |

| |

LCL |

1 |

| I5.2021-Model_9 |

Forecast |

1842 |

| |

UCL |

7224 |

| |

LCL |

-3541 |

| I5.2022-Model_10 |

Forecast |

2940 |

| |

UCL |

11661 |

| |

LCL |

-5781 |

| I6.2021-Model_11 |

Forecast |

18.19 |

| |

UCL |

68.73 |

| |

LCL |

-32.35 |

| I6.2022-Model_12 |

Forecast |

17.52 |

| |

UCL |

75.98 |

| |

LCL |

-40.94 |

| I7.2021-Model_13 |

Forecast |

1378 |

| |

UCL |

5785 |

| |

LCL |

-3029 |

| I7.2022-Model_14 |

Forecast |

1527 |

| |

UCL |

6741 |

| |

LCL |

-3686 |

| I8.2021-Model_15 |

Forecast |

5.20 |

| |

UCL |

9.69 |

| |

LCL |

0.71 |

| I8.2022-Model_16 |

Forecast |

5.20 |

| |

UCL |

9.18 |

| |

LCL |

1.21 |

| I10.2021-Model_17 |

Forecast |

21 |

| |

UCL |

54 |

| |

LCL |

-12 |

| I10.2022-Model_18 |

Forecast |

16 |

| |

UCL |

52 |

| |

LCL |

-20 |

| I12.2021-Model_19 |

Forecast |

17.74 |

| |

UCL |

29.03 |

| |

LCL |

6.44 |

| I12.2022-Model_20 |

Forecast |

19.68 |

| |

UCL |

42.30 |

| |

LCL |

-2.95 |

| I13.2021-Model_21 |

Forecast |

10.61 |

| |

UCL |

18.07 |

| |

LCL |

3.14 |

| I13.2022-Model_22 |

Forecast |

9.76 |

| |

UCL |

16.49 |

| |

LCL |

3.02 |

| I14.2021-Model_23 |

Forecast |

7.13 |

| |

UCL |

12.70 |

| |

LCL |

1.56 |

| I14.2022-Model_24 |

Forecast |

9.92 |

| |

UCL |

29.07 |

| |

LCL |

-9.23 |

| I15.2022-Model_25 |

Forecast |

-10.25 |

| |

UCL |

15.37 |

| |

LCL |

-35.86 |

| I16.2021-Model_26 |

Forecast |

88421 |

| |

UCL |

346812 |

| |

LCL |

-169970 |

| I16.2022-Model_27 |

Forecast |

70042 |

| |

UCL |

294721 |

| |

LCL |

-154638 |

| I17.2021-Model_28 |

Forecast |

2348 |

| |

UCL |

6857 |

| |

LCL |

-2161 |

| I17.2022-Model_29 |

Forecast |

1711 |

| |

UCL |

6277 |

| |

LCL |

-2855 |

| I18.2021-Model_30 |

Forecast |

5.10 |

| |

UCL |

12.03 |

| |

LCL |

-1.84 |

| I18.2022-Model_31 |

Forecast |

3.96 |

| |

UCL |

9.61 |

| |

LCL |

-1.70 |

| I19.2021-Model_32 |

Forecast |

1614 |

| |

UCL |

6052 |

| |

LCL |

-2825 |

| I19.2022-Model_33 |

Forecast |

2753 |

| |

UCL |

11032 |

| |

LCL |

-5526 |

| I20.2021-Model_34 |

Forecast |

|

| |

UCL |

|

| |

LCL |

|

| I20.2022-Model_35 |

Forecast |

|

| |

UCL |

|

| |

LCL |

|

| I21.2021-Model_36 |

Forecast |

1070 |

| |

UCL |

3804 |

| |

LCL |

-1664 |

| I21.2022-Model_37 |

Forecast |

1126 |

| |

UCL |

4381 |

| |

LCL |

-2129 |

| I22.2021-Model_38 |

Forecast |

3.66 |

| |

UCL |

8.37 |

| |

LCL |

-1.06 |

| I22.2022-Model_39 |

Forecast |

4.79 |

| |

UCL |

13.25 |

| |

LCL |

-3.67 |

| I23.2021-Model_40 |

Forecast |

3.92 |

| |

UCL |

10.76 |

| |

LCL |

-2.93 |

| I23.2022-Model_41 |

Forecast |

3.21 |

| |

UCL |

6.47 |

| |

LCL |

-0.05 |

| I24.2021-Model_42 |

Forecast |

36.94 |

| |

UCL |

100.17 |

| |

LCL |

-26.30 |

| I24.2022-Model_43 |

Forecast |

27.29 |

| |

UCL |

128.48 |

| |

LCL |

-73.91 |

| I25.2021-Model_44 |

Forecast |

64934 |

| |

UCL |

246404 |

| |

LCL |

-116536 |

| I25.2022-Model_45 |

Forecast |

42034 |

| |

UCL |

182223 |

| |

LCL |

-98156 |

| I26.2021-Model_46 |

Forecast |

297 |

| |

UCL |

912 |

| |

LCL |

-319 |

| I26.2022-Model_47 |

Forecast |

215 |

| |

UCL |

699 |

| |

LCL |

-270 |

| I27.2021-Model_48 |

Forecast |

140 |

| |

UCL |

518 |

| |

LCL |

-238 |

| I27.2022-Model_49 |

Forecast |

265 |

| |

UCL |

1169 |

| |

LCL |

-638 |

| I28.2021-Model_50 |

Forecast |

24.23 |

| |

UCL |

55.48 |

| |

LCL |

-7.02 |

| I28.2022-Model_51 |

Forecast |

18.93 |

| |

UCL |

51.89 |

| |

LCL |

-14.04 |

| Model Statistics |

| I1.2021-Model_1 |

-2.220 |

-2.220 |

| I1.2022-Model_2 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I2.2021-Model_3 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I2.2022-Model_4 |

3.331 |

3.331 |

| I3.2021-Model_5 |

2.331 |

2.331 |

| I3.2022-Model_6 |

1.665 |

1.665 |

| I4.2021-Model_7 |

|

|

| I4.2022-Model_8 |

|

|

| I5.2021-Model_9 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I5.2022-Model_10 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I6.2021-Model_11 |

2.220 |

2.220 |

| I6.2022-Model_12 |

-2.220 |

-2.220 |

| I7.2021-Model_13 |

1.110 |

1.110 |

| I7.2022-Model_14 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I8.2021-Model_15 |

-6.661 |

-6.661 |

| I8.2022-Model_16 |

-1.776 |

-1.776 |

| I10.2021-Model_17 |

1.110 |

1.110 |

| I10.2022-Model_18 |

2.220 |

2.220 |

| I12.2021-Model_19 |

-3.553 |

-3.553 |

| I12.2022-Model_20 |

-1.554 |

-1.554 |

| I13.2021-Model_21 |

2.998 |

2.998 |

| I13.2022-Model_22 |

1.443 |

1.443 |

| I14.2021-Model_23 |

-4.441 |

-4.441 |

| I14.2022-Model_24 |

-2.220 |

-2.220 |

| I15.2022-Model_25 |

0.408 |

0.231 |

| I16.2021-Model_26 |

3.331 |

3.331 |

| I16.2022-Model_27 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I17.2021-Model_28 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I17.2022-Model_29 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I18.2021-Model_30 |

6.661 |

6.661 |

| I18.2022-Model_31 |

3.331 |

3.331 |

| I19.2021-Model_32 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I19.2022-Model_33 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I20.2021-Model_34 |

1.110 |

1.110 |

| I20.2022-Model_35 |

1.110 |

1.110 |

| I21.2021-Model_36 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I21.2022-Model_37 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I22.2021-Model_38 |

6.661 |

6.661 |

| I22.2022-Model_39 |

6.661 |

6.661 |

| I23.2021-Model_40 |

-4.441 |

-4.441 |

| I23.2022-Model_41 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I24.2021-Model_42 |

2.220 |

2.220 |

| I24.2022-Model_43 |

-2.220 |

-2.220 |

| I25.2021-Model_44 |

3.331 |

3.331 |

| I25.2022-Model_45 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I26.2021-Model_46 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I26.2022-Model_47 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I27.2021-Model_48 |

0.043 |

-0.165 |

| I27.2022-Model_49 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| I28.2021-Model_50 |

2.220 |

2.220 |

| I28.2022-Model_51 |

2.220 |

2.220 |

References

- Ali, A., Iqbal, Z., & Ali, I. (2024). Women in mountain tourism: Exploring the links between women tourism entrepreneurship and women empowerment in Hunza Valley. Tourism Recreation Research, 1-17. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02508281.2024.2386869. [CrossRef]

- Angeletos, G. M., & Panousi, V. (2011). Financial integration, entrepreneurial risk and global dynamics. Journal of Economic Theory, 146(3), 863-896. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022053111000172.

- Đukan, M., Gut, D., Gumber, A., & Steffen, B. (2024). Harnessing solar power in the Alps: A study on the financial viability of mountain PV systems. Applied Energy, 375, 124019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306261924014028. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (2025). Business demography and high growth enterprises by NACE Rev. 2 activity and other typologies [urt_bd_hgn__custom_15325082].

- Fang, X. (2023). The influence of digital financial technologies on the development of tourism in the Putuo mountain area of China. AEMPS Proceedings.

- Galindo-Martín, M. A., Castaño-Martínez, M. S., & Méndez-Picazo, M. T. (2025). The relationship between networks in finance and entrepreneurship. European Journal of International Management, 25(1), 57-78. https://www.inderscienceonline.com/doi/abs/10.1504/EJIM.2025.143273. [CrossRef]

- Hough, J., & Smadi, A. (1999). Innovative financing methods for local roads in Midwest and mountain-plains states. Transportation Research Record, 1652(1), 7-12. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3141/1652-02. [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A., & Peters, M. (2018). Entrepreneurial behaviour, firm size and financial performance: The case of rural tourism family firms. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 2-14. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02508281.2017.1357782. [CrossRef]

- Kandari, P., Dobriyal, K., & Bahuguna, U. (2021a). Impact of financial inclusion on income generation and savings in mountain regions: A case study of rural households of Uttarakhand. Journal of Mountain Research, 35-44. https://jmr.sharadpauri.org/papers/2021/4%20JMR%202021%20KANDARI.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Kandari, S., Pandey, S., & Bhatt, N. (2021b). Financial inclusion and its impact on income and savings in Uttarakhand’s mountain areas. Journal of Mountain Research. https://jmr.sharadpauri.org/papers/2021/4%20JMR%202021%20KANDARI.pdf.

- Katsoulakos, N. (2016). Mountains for Europe’s future: A strategic research agenda. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nikolas-Katsoulakos/publication/302406738_Mountains_for_Europe’s_Future_A_Strategic_Research_Agenda/links/5730575f08aee022975c1b1a/Mountains-for-Europes-Future-A-Strategic-Research-Agenda.pdf.

- Koch-Weser, M. R., Kahlenborn, W., Earth3000, B., & Forum, G. G. S. I. (2004). Legal, economic and compensation mechanisms in support of sustainable mountain development. In Key Issues for the World’s Mountain Regions (pp. 63-85).

- Lyons, A. C., Johnson, W. R., & Hill, E. (2024). Psychological traits and financial behavior: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Consumer Affairs. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4915864.

- Mason, M. C., Floreani, J., Miani, S., Beltrame, F., & Cappelletto, R. (2015). Understanding the impact of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs’ performance. The role of the financing structure. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23, 1649-1661. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567115004700.

- Medina-Vidal, A., Buenestado-Fernández, M., & Molina-Espinosa, J. M. (2023). Financial literacy as a key to entrepreneurship education: A multi-case study exploring diversity and inclusion. Social Sciences, 12(11), 626. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/12/11/626. [CrossRef]

- Mountain, T. P., Kim, N., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2021). Does type of financial learning matter for young adults’ objective financial knowledge and financial behaviors? A longitudinal and mediation analysis. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 42, 113-132. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10834-020-09689-6. [CrossRef]

- Murzacheva, E., & Levie, J. (2020). The finance escalator revisited: Social, spatial, and institutional factors influencing financial decision-making of entrepreneurs in Scotland. Journal of Small Business Management. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13691066.2020.1767756. [CrossRef]

- Omri, A. (2020). Formal versus informal entrepreneurship in emerging economies: The roles of governance and the financial sector. Journal of Business Research, 108, 277-290. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0148296319306940. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V., Aceituno, L., Vila, S., Calvet-Mir, L., Garnatje, T., Jesch, A., ... & Pardo-De-Santayana, M. (2012). Home gardens in three mountain regions of the Iberian Peninsula: Description, motivation for gardening, and gross financial benefits. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 36(2), 249-270. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10440046.2011.627987. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Castro, N., López-Cabarcos, M. A., & Piñeiro-Chousa, J. (2023). Finance, technology, and values: A configurational approach to the analysis of rural entrepreneurship. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122444. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162523001294. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M., Nonthapot, S., Mohamad, S., Chee Keong, O., Ehsanullah, S., & Iqbal, N. (2022). Does green finance matter for sustainable entrepreneurship and environmental corporate social responsibility during COVID-19?. China Finance Review International, 12(2), 317-333. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/cfri-02-2021-0038/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Soltanifar, M., Hughes, M., & Göcke, L. (2021). Digital entrepreneurship: Impact on business and society (p. 327). Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Ward, A. (2017). The extent and value of carbon stored in mountain grasslands and shrublands globally and the prospects for using climate finance to address natural resource management issues. ResearchGate.

- Ward, A., Dargusch, P., Grussu, G., & Romeo, R. (2016). Using carbon finance to support climate policy objectives in high mountain ecosystems. Climate Policy, 16(6), 732-751. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14693062.2015.1046413. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).