Background

Globally, unintended pregnancy remains a significant public health challenge, with an estimated 121 million unintended pregnancies occurring annually, of which approximately 61% end up being terminated [

1]. Pregnancy termination refers to the process of ending a pregnancy by removing the contents of a pregnant woman's uterus, typically using medical, surgical, or non-surgical, as well as traditional methods [

2]. The 2010 to 2014 trend shows that more than 25 million pregnancy terminations were reported globally, of these, 15% were among adolescents aged 15 to 19 [

3]. Female youths aged 15-24 face disproportionate risks, with limited access to comprehensive sexual education and family planning services [

4]. Despite legal restrictions in many countries, pregnancy termination continues to occur covertly, often under unsafe conditions that contribute to maternal mortality and morbidity, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and other low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [

5]. Understanding the complex interplay of socioeconomic, cultural, and health system factors that influence pregnancy termination decisions among young women is essential for developing effective interventions that address root causes rather than symptoms [

2].

There are an estimated 2.2 million unintended pregnancies annually among adolescents and young women in SSA, and more than 25% of them end up in unsafe termination [

6]. The SSA region faces unique challenges, including high adolescent fertility rates [

7], limited contraceptive access [

8], and restrictive abortion laws in many countries [

9], posing the need for understanding this public health concern of pregnancy termination. Between 2010 and 2018, an estimated pregnancy termination rate of 16.27% occurred in SSA [

10]. Of these, 75% were classified as unsafe, and female youths accounted for 57% of the reported cases [

1]. Research indicates that female youth in SSA who seek pregnancy termination often cite educational disruption, economic constraints, partner rejection, and social stigma as key motivating factors [

2,

7,

11]. The covert nature of many unsafe pregnancy terminations leads to health consequences like maternal death, hemorrhage, infection, and infertility. The majority of reported maternal deaths in the region are due to the complications of pregnancy termination [

6,

12,

13].

The health impact of unsafe pregnancy termination extends beyond immediate physical complications to include significant psychological distress, social isolation, and economic hardship due to catastrophic health expenditures [

14]. Female youths who experience complications from unsafe procedures often delay seeking care due to fear of legal repercussions and social stigma, increasing the severity of outcomes [

11]. Health systems in resource-limited settings are also impacted by the cost of treating these preventable complications [

15]. Additionally, the intersection of pregnancy termination with other health issues, like HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections, creates complex challenges that require integrated approaches to sexual and reproductive health care for female youths [

16]. Research on factors associated with pregnancy termination among sexually active female youths is crucial for global health as it addresses a key determinant of maternal mortality, particularly in vulnerable populations like female youths [

3]. Despite significant policy advances through initiatives like the Sustainable Development Goals and the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, implementation gaps persist in most LMICs [

17,

18].

In Tanzania, pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth represents a significant but understudied public health concern [

19]. It remains a debatable issue due to restrictive laws that only permit the procedure under specific circumstances, such as to save the life or health of the pregnant woman or in cases of sexual violence [

20]. The legal framework is not only restrictive but also lacks clarity, which further hinders women's access to safe pregnancy termination services [

19]. Even with these legal restrictions, sexually active female youth continue to seek pregnancy terminations, often through unsafe methods that contribute to Tanzania's maternal mortality rate [

19,

21]. Despite available studies on pregnancy termination in Tanzania [

19,

22,

23], studying trends in pregnancy termination is crucial. Assessing trends helps to elucidate the implications for maternal health and informs policymakers about the need for reforms that prioritize women's health rights and promote safe practices, which reduce maternal mortality rates linked to unsafe pregnancy terminations. The reproductive health landscape for female youth in Tanzania is characterized by limited access to comprehensive sex education, inconsistent contraceptive availability, and strong sociocultural and religious influences that stigmatize premarital sex and unintended pregnancies, which increase the rate of these unsafe practices [

24].

Recent studies indicated that youth in urban areas, those with lower education levels, and those experiencing economic hardship are more likely to consider pregnancy termination, though reliable data remains scarce due to the sensitive nature of the topic [

7,

25]. While existing studies have provided valuable insights, few have explored the trends of pregnancy termination within the youth population. This has left a gap in understanding that the current study seeks to address. This created a knowledge gap, which resulted in the need for this study. Therefore, this study aims to assess the trends and factors associated with pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania by using the 2004/5 to 2022 Tanzania Demographic Health Survey (TDHS). The findings of this research are essential for developing context-specific strategies that can effectively reduce maternal deaths, decrease health system burdens, and advance gender equity in health outcomes globally.

Methods

2.Data source and design

This study was an analytical cross–sectional survey that utilized secondary data spanning from the 2004/05 to 2022 TDHS, which conducts nationally representative population-based household surveys typically every five years. The Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics conducted the survey with the Ministries of Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar. Tanzania is one of the countries in East Africa, covering an area of 945,087 square kilometers, including 61,000 square kilometers of inland water. According to the 2022 census, the country has a population of approximately 62 million people [

26].

2.Population and sampling

A nationally representative cross-sectional study using secondary data from the TDHS covering the years 2004/05 to The TDHS, conducted every five years, gathers updated information on health and health-related indicators. The sample design of the DHS employed a two-stage sampling process to provide national, urban, and rural estimates for both Tanzania Mainland and Zanzibar. In the first stage, sampling points (clusters) were selected from enumeration areas (EAs) based on the previous Tanzania Population and Housing Census (PHC), using a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling technique. Regions were grouped into zones to minimize sampling errors and enhance accuracy in zonal-level estimates. Tanzania was stratified by geographical regions and urban/rural classification, with each stratum treated as a distinct sampling domain. In the second stage, households were systematically selected from each cluster. To account for unequal selection probabilities and non-responses, individual weights were calculated for each respondent. We used the Individual recode files (IR) for this study extracted from each survey wave. Women between the ages of 15 and 49 who were either inhabitants of the chosen households permanently or guests who were there the night before the survey were eligible.

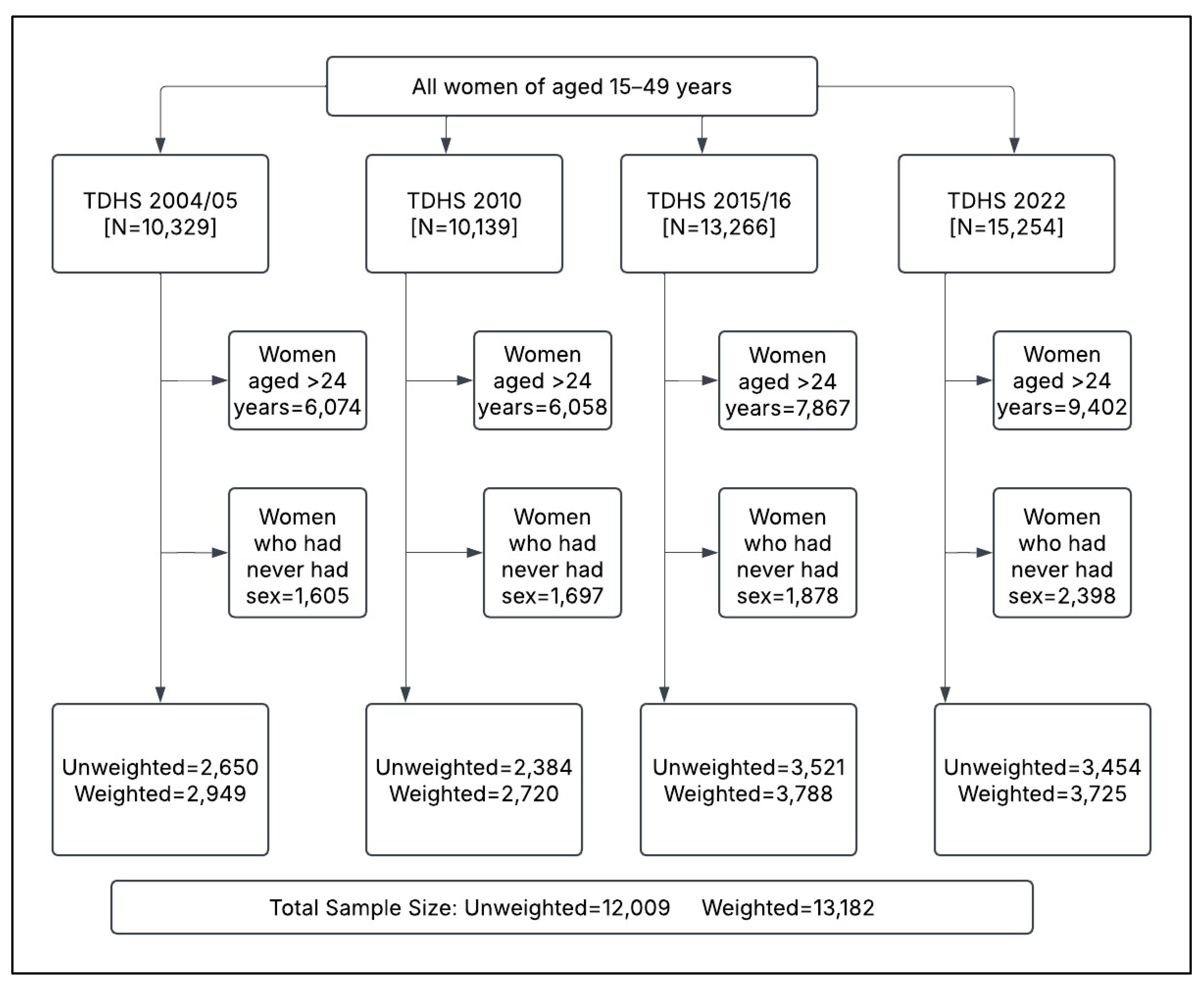

This study focused on female youth aged 15-24 years. Therefore, women aged ≥25 years were excluded. To accurately assess pregnancy termination, women who reported never having had sexual intercourse were also excluded, as they would not have experienced pregnancy. Datasets from four survey rounds were appended and appropriately weighted to ensure representativeness and reliable estimates. The final weighted sample comprised 13,182 sexually active female youth, distributed as follows: 2,949 in 2004/05, 2,720 in 2010, 3,788 in 2015/16, and 3,725 in 2022. (

Figure 01).

Figure.

Flow chart showing the sample size used in the analysis; data from the Tanzania and demographic health surveys 2004/05-2022.

Figure.

Flow chart showing the sample size used in the analysis; data from the Tanzania and demographic health surveys 2004/05-2022.

2.Study Variables

2.3.Dependent variable

The outcome variable in this study was pregnancy termination, which was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire item: 'Have you ever had a pregnancy terminated?' and was recorded as a binary response (yes/no). Pregnancy termination was defined as any pregnancy that resulted in a miscarriage, abortion, or stillbirth, as used by studies in SSA to mitigate socio-desirability bias [

27]. Young women might reinterpret their experience of induced abortion as a miscarriage or stillbirth, as these are less stigmatized and not legally prohibited.

2.3.Independent variables

The current study examined variables based on the available data and literature [

1,

7,

23,

25]. The following variables were included under the individual level; age in years (15–19 or 20–24), education level (no formal education, primary or secondary/higher), marital status (never married or ever married), wealth index (poor, middle, rich), literacy (literate or illiterate), working status (working or not working), contraceptive use (any method or none), sexual initiation (<15 or ≥15 years), literacy (literate or illiterate), sex of household head (male or female) and media exposure status was created from the frequency of reading a newspaper or magazine, watching TV, and listening to the radio. If a woman has at least one yes, she has considered having media exposure and was coded as (yes or no), visiting a health facility in the past 12 months (yes or no), currently abstaining (yes or no), sex of household head (male or female), household members (≤5 or ≥6), residence (urban or rural) and geographical zones (western, northern, central, southern, lake, eastern and Zanzibar).

2.Data management and analysis

To account for the complexity of the survey design, individual sampling weights (v005/1,000,000), primary sampling units (clusters), and strata were applied to adjust for the cluster sampling design and to control for potential under- or over-sampling. Data cleaning, coding, and analysis were conducted using STATA version 18.5 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics were summarized using means, standard deviations (SD), and frequencies, with proportions for categorical variables. The prevalence of pregnancy termination was calculated as the number of female youths who experienced pregnancy termination divided by the total number of female youths in the dataset.

A weighted binary logistic regression model was used to determine factors associated with pregnancy termination, with results presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI). Univariate analyses were performed by fitting each explanatory variable against the outcome variable (pregnancy termination) to produce crude odds ratios (COR). A backward selection method, using a p-value of <0.1, was applied to select covariates for inclusion in the final multivariable analysis. Before multivariable regression, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to assess multicollinearity. The resulting mean VIF of 4.61 confirmed the absence of significant multicollinearity. Finally, a multivariable weighted logistic regression model was fitted, controlling for potential confounders, including respondents’ age, to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) to determine the strength and magnitude of the associations. All analyses were two-tailed, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

3.Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of sexually active female youths across the survey years. More than half of the women were aged 20-24 years, with an overall mean age of 20.4 years (standard deviation = 2.5). The majority (>50%) had attained primary education, and a similar proportion were literate. Regarding socioeconomic status, over one-third were from the poor quintile and nearly half from the rich quintile. In terms of sexual initiation, the majority (>80.0%) had their first sexual intercourse aged ≥15 years. As expected, most households were headed by males (>70%), and more than 50% of the female youths were employed. More than half had visited a health facility in the past 12 months, and nearly half were from households with at least six members. Less than one-third of the women were using contraceptive methods, and less than one in five female youth were currently abstaining (

Table 1).

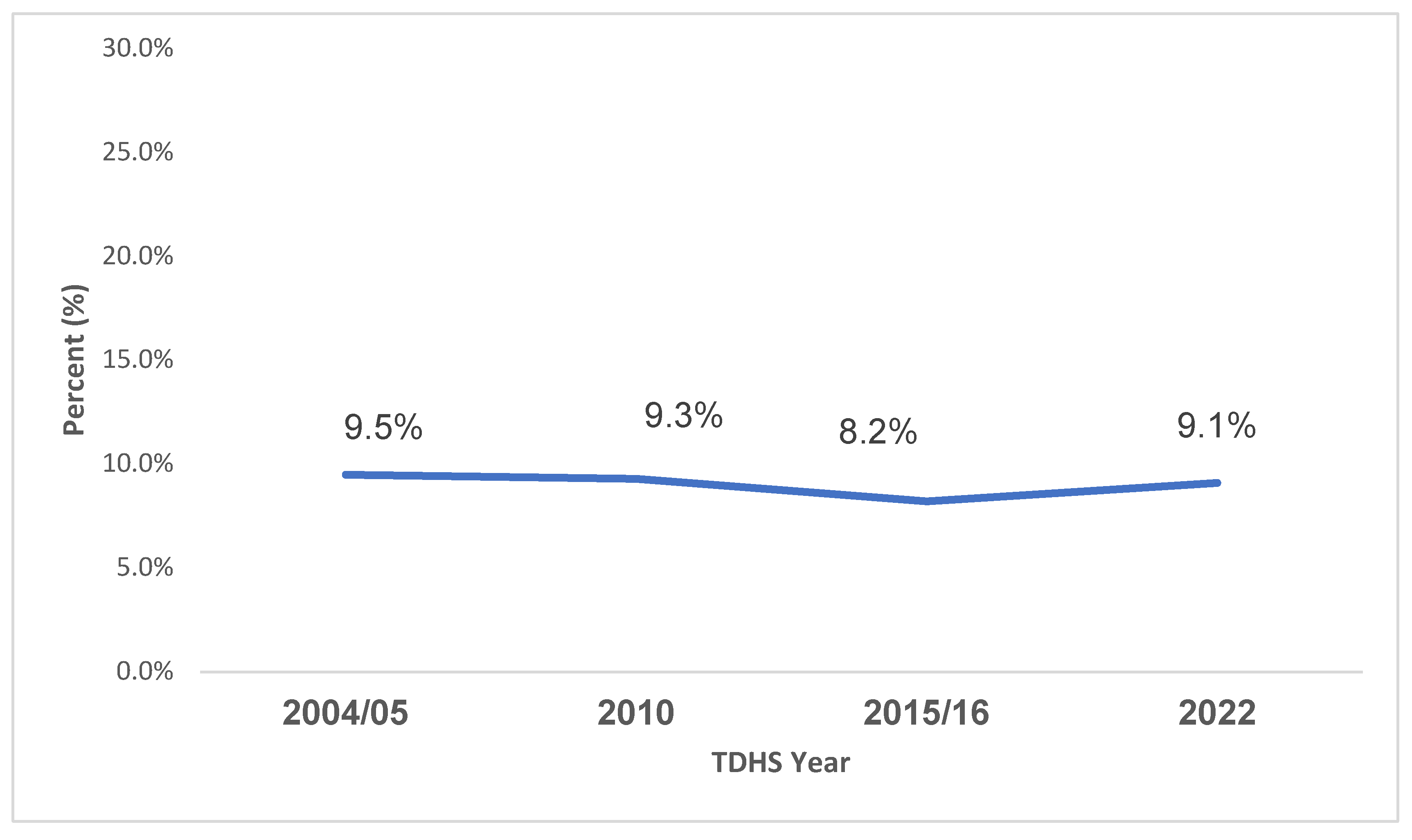

3.Prevalence and trend of pregnancy termination

The present study estimated the overall pooled weighted prevalence of pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania to be 9.0% (95% CI: 8.4–9.6). Specifically, the prevalence varied by year: 9.5% in 2004/05, 9.3% in 2010, 8.2% in 2015/16, and 9.1% in 2022.

Figure .

Trend of pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania from 2004/05–2022.

Figure .

Trend of pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania from 2004/05–2022.

3.The trend of pregnancy termination across female youth’s characteristics

Table 2 indicates the trend and statistical significance for different sociodemographic characteristics across the four survey years. Age group, marital status, working status, and geographical zones were statistically significant in various years, indicating that these factors had a meaningful impact on the prevalence of pregnancy termination. Education level, media exposure, and sexual initiation showed varying levels of significance depending on the survey year.

The prevalence of pregnancy termination for the 15-19 age group decreased from 7.1% in 2004/05 to 4.7% in 2022, though there were fluctuations in between (such as a slight increase in 2015/16). The 20-24 age group showed a slight decrease in prevalence over the years but remained relatively stable at around 10-12%. Women with no formal education had a higher prevalence of pregnancy termination compared to those with primary or secondary/higher education, though the trends varied across the years. There is a notable decrease in the prevalence among women with no formal education from 12.3% in 2004/05 to 9.9% in 2022.

Early sexual initiation (<15 years) showed a notable spike in 2010 (13.2%) but returned to a level similar to late initiation (≥15 years) in Women using any method of contraception consistently showed a lower prevalence of pregnancy termination, with a slight increase in 2022, particularly among those who used contraception. Women from poorer households had a consistently higher prevalence of pregnancy termination than those from wealthier households across the years, though the richest women showed an increase in 2022 (10.9%).

In terms of geographical locations, Urban women had a higher prevalence of pregnancy termination in 2022, with 10.9%, compared to rural women (8.2%). There were noticeable geographical differences, particularly in the Eastern zone of mainland Tanzania, where the prevalence of pregnancy termination increased dramatically to 15.9% in Other zones, like Central and Southern, showed a decrease over time, particularly in 2022 (

Table 2).

3.Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with pregnancy termination

The results from

Table 3 indicate an association between different predictors and pregnancy termination. In the adjusted analysis, female youth aged 20-24 years (AOR=1.79, 95%CI: 1.48-2.16) had a higher likelihood of pregnancy termination compared to their counterparts. Female youth with secondary or higher education were 31% less likely to have pregnancy termination compared to those with no formal education (AOR=0.69, 95%CI: 0.52-0.92). In terms of engaging in sexual intercourse, female youth who had late initiation (AOR=0.68, 95%CI: 0.56-0.83) had lower odds of pregnancy termination compared to their counterparts. Female youth who were currently abstaining had lower odds of pregnancy termination compared to their counterparts (AOR=0.60, 95%CI: 0.47-0.78). Female youths who use contraception (AOR=0.66, 95%CI:(0.54-0.79) had decreased odds of pregnancy termination compared to their counterparts. Regarding geographical zones., female youths in Eastern (AOR=1.77, 95%CI:1.28-2.43)) and Zanzibar (AOR=1.53, 95%CI: 1.08-2.15) had higher odds of pregnancy termination (

Table 3).

Discussion

Our study aimed to assess the trends and factors associated with pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania by using the 2005 to 2022 TDHS. This study showed a pooled weighted prevalence of pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania was 9.0%, which aligns with existing literature concerning the complexity of reproductive health challenges in the region and East Africa [

25]. The reported prevalence is higher than that in some SSA countries but also lower compared to some other countries [

25]. Previous studies have shown that Tanzania exhibits relatively high rates of unintended pregnancies, with approximately one million women facing unintended pregnancies yearly, 39% of these resulting in pregnancy termination [

23]. The observed pooled prevalence still calls for necessary attention to minimize this rate and ultimately contribute to safe maternal health.

The observed trends in prevalence rates in this study suggest a trajectory during the monitored years, reflecting varying socio-economic and policy environments affecting women's reproductive choices [

1]. This trend showed a decline and a slight increase in the prevalence that correlate with several factors that hinder effective family planning initiatives in Tanzania [

28]. In comparison, the study by Ahinkorah emphasized that socio-economic factors are significant determinants in maintaining the trend of pregnancy termination rates [

7]. The slight uptick in 2022 implies a resurgence of unplanned pregnancies linked to the socio-political climate impacting women's health services during the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in substantial service interruptions, as reported by a study assessed by several SSA countries [

29]. Hence, while the reported prevalence is suboptimal, it also highlights the necessity for more robust health policy initiatives aimed at improving reproductive health education and access to safe pregnancy termination services in Tanzania.

This study also established several factors that influence pregnancy termination among female youths in Tanzania. The same factors can inform public health interventions in Tanzania, but in other SSA countries. The findings from the adjusted analysis reveal that female youth aged 20-24 years have a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing pregnancy termination compared to their younger counterparts. This aligns with existing literature, which suggests that older female youths often face more complex social and economic pressures that contribute to unintended pregnancies and resultant terminations [

1]. Another study also showed a similar trend, where older youth not only exhibit higher sexual activity but also face systemic barriers to accessing reproductive health services, thus increasing their vulnerability to unintended pregnancies that end up being terminated [

25].

Educational attainment emerged as a crucial factor in reducing pregnancy termination rates. This finding is consistent with the assertion that education equips young women with knowledge and agency over their reproductive choices [

30]. Tanzania has ongoing discussions on whether pregnant adolescents can continue with their schooling [

31], whereby these findings inform policymakers on the importance of education in preventing pregnancy termination. Recent research indicates that increased education levels correlate with improved access to contraception and a proactive approach to sexual health decision-making [

7,

9]. Conversely, disparities in education amongst Tanzanian youth often exacerbate the prevalence of unintended pregnancies, as those with no formal schooling have reported higher rates of sexual initiation and limited contraceptive use [

32].

Considering the timing of sexual initiation, female youth who engaged in late initiation of sexual activities reported lower odds of pregnancy termination. This observation underscores the benefits of promoting delayed sexual initiation as a programmatic strategy for addressing adolescent pregnancy in Tanzania [

33]. Previous studies advocate for comprehensive sex education programs that emphasize the value of abstinence during formative years, which results in fewer unintended pregnancies among youths [

34]. Such interventions are effective in reducing pregnancy rates across various regions, including SSA [

33].

Furthermore, the importance of family planning services is shown by the finding that higher contraceptive uptake is associated with lower termination rates, which corroborates the previous findings that access to modern contraceptive methods is crucial for mitigating unintended pregnancies among young women and hence reducing pregnancy termination for non-medical reasons [

35]. Additionally, geographical variations were evident, with higher odds of pregnancy termination in Eastern regions and Zanzibar. This finding is similar to the previous study, which was conducted in Arusha, which is found in Eastern regions and Zanzibar [

36]. These regions were also found to have higher odds of early sex initiation in the previous study [

33]. This regional disparity reflects underlying structural and socio-cultural differences that impact access to healthcare services, as provinces with restricted reproductive rights often exhibit higher rates of unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions [

33,

36]. These findings support an urgent need for tailored reproductive health policies that address the unique challenges faced by youths in different geographic contexts within Tanzania.

4.Strength and limitations

The strengths of this study include its use of a large, nationally representative, weighted sample derived from four TDHS rounds and its ability to provide valuable policy insights through the analysis of national survey data. Spanning nearly two decades, allowing for robust trend analysis and generalizability across Tanzania's diverse regions Nonetheless, limitations must be acknowledged. Potential underreporting of pregnancy terminations due to self-reported data, which may be subject to recall, social desirability bias, legal restrictions, and stigma surrounding the practice in Tanzania. The DHS questionnaire design likely captures only a portion of actual pregnancy terminations, as it does not explicitly distinguish between induced abortions and spontaneous miscarriages, potentially masking the true prevalence. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of each survey wave limits causal inference, and the study may miss important contextual factors such as specific cultural practices, quality of local healthcare services, and individual decision-making processes that cannot be captured through standardized survey instruments. These findings can be interpreted with the above notations.

Conclusion

This study reveals that pregnancy termination among sexually active female youth in Tanzania remains a public health concern, influenced by various sociodemographic factors including age, educational attainment, timing of sexual initiation, and regional disparities. Implementing comprehensive, age-appropriate sexual education programs in schools that emphasize delayed sexual debut and responsible reproductive choices will help decrease the rate of unsafe pregnancy termination. Healthcare systems should prioritize expanding youth-friendly contraceptive services with particular attention to older female youth (20-24 years) who demonstrate higher odds of pregnancy termination. Regionally tailored interventions are essential, especially targeting Eastern regions and Zanzibar where pregnancy termination rates are elevated. Additionally, strengthening educational opportunities for young women appears crucial, as higher education levels correlate with lower pregnancy termination rates. Policy reforms should focus on removing barriers to reproductive healthcare access while considering the socio-cultural contexts unique to each region. Finally, continuous monitoring of pregnancy termination trends through improved data collection methods would enable more effective evaluation of interventions and guide resource allocation to address this critical reproductive health challenge among Tanzania's female youth population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EES, TPM, VGM and MJM; methodology, EES and MJM; software, MJM; validation, AAJ, FVM, SK and MJM.; formal analysis, MJM; investigation, (NA, conducted by DHS); resources, EES and MJM; data curation, MJM; writing original draft preparation, EES, TPM, AAJ, FVM, SK, VGM and MJM.; writing, review and editing, EES, TPM, AAJ, FVM, SK, VGM and MJM; visualization, MJM; supervision, EES, AAJ, FVM and MJM; project administration, EES and MJM; funding acquisition, (NA, No funds). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study is based on the publicly available 2004/05-2022 TDHS datasets, which are accessible online and have been de-identified. The initial survey was approved by the National Institute of Medical Research Ethics Committee in Tanzania and the ICF Macro Ethics Committee in Calverton, New York. We obtained permission to use the DHS data from MEASURE Tanzania Demographic and Health Surveys after submitting a request outlining our data analysis plan. Upon receiving approval, we downloaded the dataset from the DHS Program’s website. Informed consent was obtained from participants before the interviews. All methods were conducted following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the DHS study

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation. The complete dataset is available at

https://dhsprogram.com

Acknowledgements

We thank the DHS program for making the data available for this study and TILAM International for statistical consultations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AOR |

Adjusted odds ratio |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| COR |

Crude odds ratio |

| DHS |

Demographic Health Survey |

| EAs |

Enumeration areas |

| HIV/AIDS |

Human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| LMIC |

Low-Middle Income Countries |

| Ns |

Not significant |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| PHC |

Population and Housing Census |

| PPS |

Probability proportional to size |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SSA |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

| TDHS |

Tanzania Demographic Health Survey |

| VIF |

Variance inflation factor |

References

- Kassa RN, Kaburu EW, Andrew-Bassey U, Abdiwali SA, Nahayo B, Samuel N, et al. Factors associated with pregnancy termination in six sub-Saharan African countries. PLOS Glob Public Health 2024, 4, e0002280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabetha K, Soepnel LM, SSewanyana D, Draper CE, Lye S, Norris SA. A qualitative exploration of the reasons and influencing factors for pregnancy termination among young women in Soweto, South Africa: a Socio-ecological perspective. Reprod Health 2024, 21, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obiyan MO, Olaleye AO, Oyinlola FF, Folayan MO. Factors associated with pregnancy and induced abortion among street-involved female adolescents in two Nigerian urban cities: a mixed-method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngoma-Hazemba A, Chavula MP, Sichula N, Silumbwe A, Mweemba O, Mweemba M, et al. Exploring the barriers, facilitators, and opportunities to enhance uptake of sexual and reproductive health, HIV and GBV services among adolescent girls and young women in Zambia: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2024, 24, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson AJ, Root L. Trends in Maternal Death Post-Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health. JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7, e2430035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederico M, Michielsen K, Arnaldo C, Decat P. Factors Influencing Abortion Decision-Making Processes among Young Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:329.

- Ahinkorah, BO. Socio-demographic determinants of pregnancy termination among adolescent girls and young women in selected high fertility countries in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:1–8.

- Engelbert Bain L, Amu H, Enowbeyang Tarkang E. Barriers and motivators of contraceptive use among young people in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of qualitative studies. PloS One. 2021;16:e0252745.

- Hinson L, Bhatti AM, Sebany M, Bell SO, Steinhaus M, Twose C, et al. How, when and where? A systematic review on abortion decision making in legally restricted settings in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:415.

- Adde KS, Dickson KS, Ameyaw EK, Amo-Adjei J. Contraception needs and pregnancy termination in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis of demographic and health survey data. Reprod Health. 2021;18:177.

- Zia Y, Mugo N, Ngure K, Odoyo J, Casmir E, Ayiera E, et al. Psychosocial experiences of adolescent girls and young women subsequent to an abortion in sub-Saharan Africa and globally: a systematic review. Front Reprod Health 2021, 3, 638013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, DG. The turnaway study: ten years, a thousand women, and the consequences of having—or being denied—an abortion. Simon and Schuster; 2021.

- Paltrow LM, Harris LH, Marshall MF. Beyond abortion: The consequences of overturning Roe. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:3–15.

- Yazdkhasti M, Pourreza A, Pirak A, Abdi F. Unintended pregnancy and its adverse social and economic consequences on health system: a narrative review article. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:12.

- Raza S, Banik R, Noor STA, Jahan E, Sayeed A, Huq N, et al. Assessing health systems’ capacities to provide post-abortion care: insights from seven low-and middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2025;15:04020.

- Warren CE, Mayhew SH, Hopkins J. The current status of research on the integration of sexual and reproductive health and HIV services. Stud Fam Plann. 2017;48:91–105.

- Latt SM, Milner A, Kavanagh A. Abortion laws reform may reduce maternal mortality: an ecological study in 162 countries. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19:1.

- Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.

- Keogh SC, Kimaro G, Muganyizi P, Philbin J, Kahwa A, Ngadaya E, et al. Incidence of Induced Abortion and Post-Abortion Care in Tanzania. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0133933.

- Rosser BS, Mgopa L, Leshabari S, Ross MW, Lukumay GG, Massawe A, et al. Legal and ethical considerations in the delivery of sexual health care in Tanzania. Afr J Health Nurs Midwifery. 2020;3:84.

- Bwana VM, Rumisha SF, Mremi IR, Lyimo EP, Mboera LE. Patterns and causes of hospital maternal mortality in Tanzania: A 10-year retrospective analysis. PloS One. 2019;14:e0214807.

- Woog V. Unsafe Abortion in Tanzania: A Review of the Evidence. 2013 [cited 2025 Apr 12]; Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/unsafe-abortion-tanzania-review-evidence.

- Mbona SV, Chifurira R, Ndlovu BD, Ananth A. Prevalence and determinants of pregnancy termination for childbearing women using the modified Poisson regression model: a cross-sectional study of the Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS) BMC Public Health. 2025;25:56.

- Mesiäislehto V. Sexual and reproductive health and rights through the lens of belonging: Intersectional perspectives on disability, gender, and adolescence in Tanzania. JYU Diss. 2023.

- Hailegebreal S, Enyew EB, Simegn AE, Seboka BT, Gilano G, Kassa R, et al. Pooled prevalence and associated factors of pregnancy termination among youth aged 15–24 year women in East Africa: Multilevel level analysis. Plos One. 2022;17:e0275349.

- The United Republic of Tanzania (URT), Ministry of Finance and Planning, Tanzania, National Bureau of Statistics and President’s Office - Finance and Planning, Office of the, Chief Government Statistician, Zanzibar, Chief Government Statistician, Zanzibar. The 2022 Population and Housing Census: Administrative Units Population Distribution Report; Tanzania Zanzibar, [Internet]. The United Republic of Tanzania (URT); Available from: https://sensa.nbs.go.tz/publication/volume1c.pdf.

- Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Hagan JE, Archer AG, Budu E, Adoboi F, et al. Predictors of Pregnancy Termination among Young Women in Ghana: Empirical Evidence from the 2014 Demographic and Health Survey Data. Healthcare. 2021;9:705.

- Kassim M, Ndumbaro F. Factors affecting family planning literacy among women of childbearing age in the rural Lake zone, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:646.

- Semaan A, Banke-Thomas A, Amongin D, Babah O, Dioubate N, Kikula A, et al. ‘We are not going to shut down, because we cannot postpone pregnancy’: a mixed-methods study of the provision of maternal healthcare in six referral maternity wards in four sub-Saharan African countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e008063.

- Moshi FV, Tilisho O. The magnitude of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenagers in Dodoma Tanzania: a community-based analytical cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2023;20:28.

- Mkumbugo S, Shayo J, Mloka D. Moral challenges in handling pregnant school adolescents in Tanga municipality, Tanzania. South Afr J Bioeth Law. 2020;13.

- Metta E, Chota A, Leshabari M. Experiences of girls dropping out of secondary school due to unplanned pregnancies in Southern Tanzania. Int J Sci Res. 2020;9:687–92.

- Eliufoo E, Mtoro MJ, Godfrey V, Bago M, Kessy IP, Millanzi W, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of early sexual initiation among female youth in Tanzania: a nationwide survey. BMC Public Health. 2025;25:812.

- Millanzi WC, Kibusi SM, Osaki KM. Effect of integrated reproductive health lesson materials in a problem-based pedagogy on soft skills for safe sexual behaviour among adolescents: A school-based randomized controlled trial in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellizzi S, Pichierri G, Menchini L, Barry J, Sotgiu G, Bassat Q. The impact of underuse of modern methods of contraception among adolescents with unintended pregnancies in 12 low-and middle-income countries. J Glob Health. 2019;9:020429.

- Nyalali K, Maternowska C, Brown H, Testa A, Coulson J, Gordon-Maclean C. Unintended pregnancy among teenagers in Arusha and Zanzibar, Tanzania. Situat Anal Marie Stopes Int. 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).