The interaction between monetary policy and the structure of the banking sector has become increasingly relevant, especially in a context of constantly changing interest rates and the use of unconventional monetary policy instruments (NCMP). Recent literature highlights that the effectiveness of monetary policy transmission is not only influenced by the stance of central banks but also by the competitive and concentration dynamics within the banking system, and that monetary policy decisions can, in turn, affect the levels of competition in the banking system.

Determinants of Concentration in the Banking System

The structure of financial markets has been a central topic of economic research, especially in the context of bank concentration and its effects on competition, financial stability, and consumer welfare. The banking sector has unique characteristics that differentiate it from other sectors, such as high barriers to entry, network externalities, and strict regulatory oversight. Traditionally, banking competition has been analyzed through two opposing views: the structure-conduct-performance hypothesis (SCP) and the efficient structure hypothesis (ES) (Bain, 1951; Demsetz, 1973).

The SCP hypothesis postulates that higher concentration in the banking sector reduces competition, leading to higher placement rates, lower deposit rates, and lower financial inclusion (Berger & Hannan, 1989). In contrast, the ES hypothesis argues that concentration is due to increased efficiency, as larger banks achieve economies of scale and scope that allow them to offer better services and lower consumer costs (Berger, 1995). In addition, spatial competition models, such as Hotelling's (1929) model, have been widely used to analyze product differentiation and competition among banks (Salop, 1979). These models have been extended to include digital banking, emphasizing how neo banks and fintech firms disrupt traditional banking structures (Philippon, 2019)

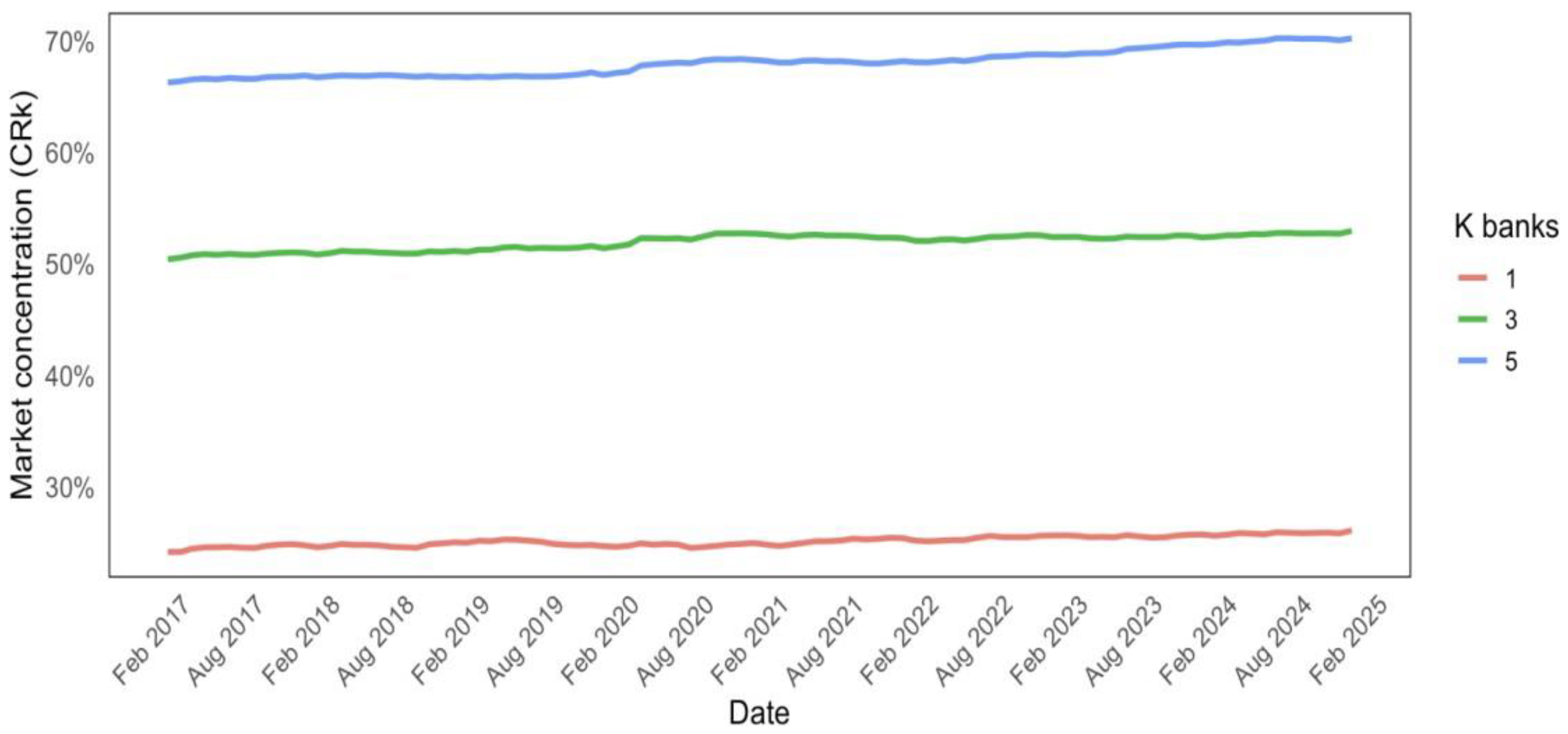

Research in emerging markets, including Latin America, reveals that greater concentration correlates with increased financial exclusion and higher loan collateral requirements, particularly for SMEs. A concentrated banking market can significantly affect corporate financing. Studies have shown that firms in highly concentrated banking sectors often face higher collateral requirements, which can disproportionately affect small and medium-sized firms (Thein et al., 2024). In markets characterized by high concentration, financial institutions tend to exhibit risk-averse behavior, increasing the propensity to require collateral for SMEs and large corporations. Consequently, this increased concentration puts additional pressure on credit-seeking firms, limiting their ability to invest and expand. A comparative analysis of financial systems across Latin America suggests that bank concentration in Colombia is above the regional average, leading to increased barriers to credit access. Research by Cao-Alvira and Gómez-González (2025) on regional banking concentration in Colombia indicates that firms operating in highly concentrated banking environments tend to have higher accounting leverage, reflecting limited financing options.

The emergence of neobanks can disrupt traditional banking structures by offering low-cost digital financial services. Unlike traditional banks, neobanks operate without physical branches and leverage innovations in financial technologies to reach underserved populations. In Colombia, neobanks such as Nu and Lulo Bank have introduced services with reduced fees, simplified account-opening processes, and increased accessibility through mobile platforms (Frost, 2020). However, while neobanks provide greater financial inclusion, they also face regulatory challenges and infrastructure limitations that may hinder their ability to compete effectively with traditional banks. A study on competition in the banking sector in Latin America concluded that regulatory frameworks often favor established financial institutions, creating an uneven playing field for new entrants (Banco de la República de Colombia, 2022). In addition, research on the impact of FinTech on traditional banking suggests that while neobanks increase competition in deposit markets, their influence on banks' market power remains limited.

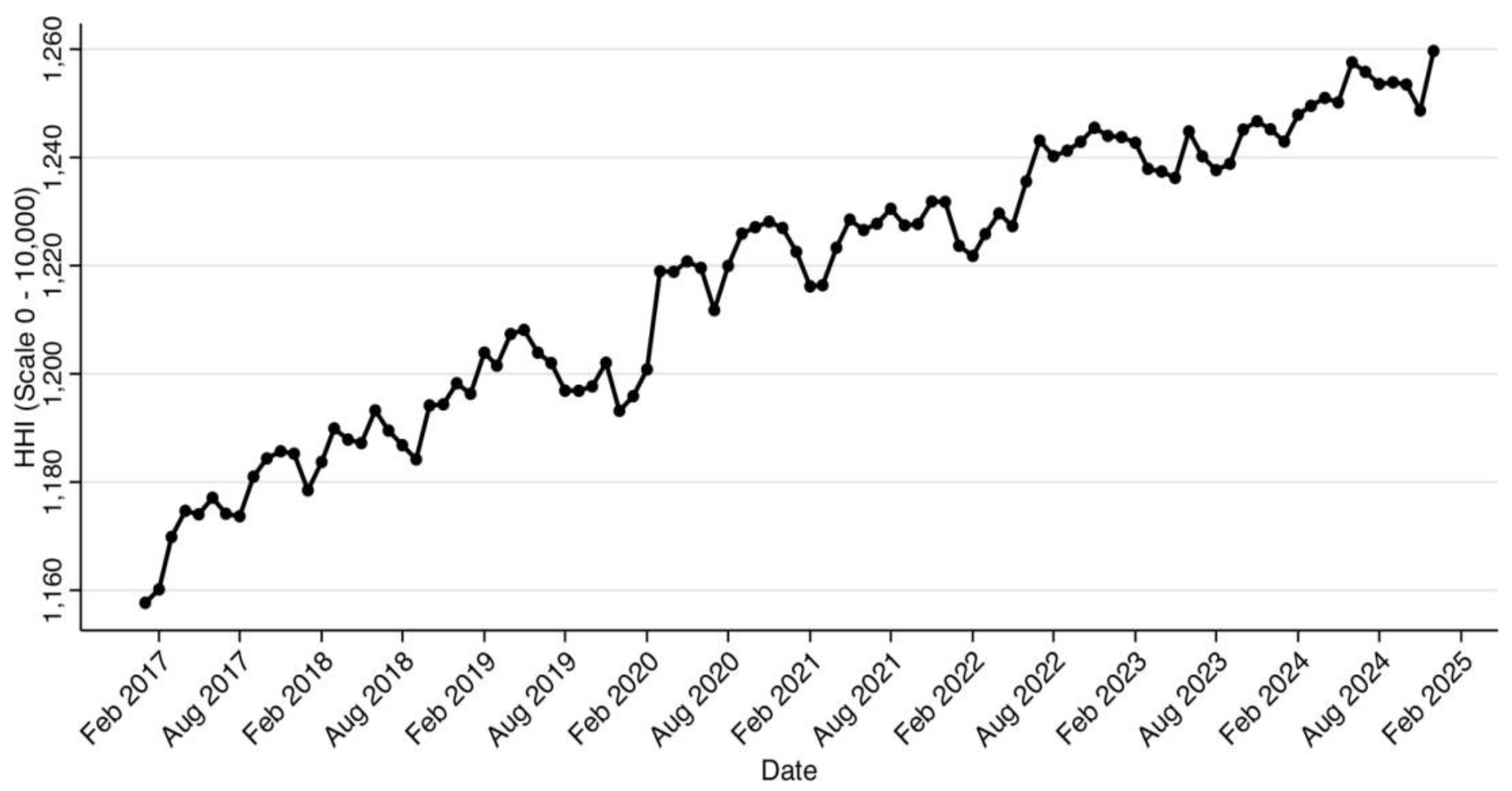

On the other hand, regulatory supervision plays a crucial role in shaping the competitive dynamics of the banking sector. Historically, the Colombian financial sector has undergone important transformations, including the financial liberalization reforms of the 1990s, which aimed to increase competition and improve market efficiency (Holmes et al., 2015). Despite these efforts, the country's banking market remains highly concentrated, with the three largest banks concentrating approximately 60% of total credit issuance. Research suggests that regulatory barriers limit market entry for smaller banks and FinTech firms. Strict capital requirements, licensing restrictions, and compliance costs create challenges for new entrants, reinforcing the dominance of traditional banks. Studies on banking regulation in Latin America emphasize the need for open banking initiatives, which could facilitate competition by allowing new entrants to access customer data from established financial institutions (Makhlouf et al., 2023).

The elasticity of substitution between traditional banks and neobanks provides a quantitative measure of how price, service, or other attributes affect the likelihood that consumers will switch from one type of bank to another. If the elasticity is high, neobanks represent a strong competitive force, exerting downward pressure on fees and interest rate spreads. If elasticity is low, traditional banks can retain their market power, allowing them to maintain higher fees and interest rates without significantly losing customers.

A key factor in the debate on monopolistic competition in the banking sector is financial inclusion. Despite advances in bankarization, a significant portion of the Colombian population remains unbanked or relies on informal financial services (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2021). Neobanks have the potential to close this gap by offering simplified digital banking solutions with minimal fees, allowing people without access to traditional banking services to participate in the formal financial system.

However, regulatory restrictions, lack of digital literacy, and limited financial education programs hinder the rapid adoption of these alternatives, especially in rural and low-income populations (Camara & Tuesta, 2017). Government policies promoting digital literacy and financial education will be crucial to ensure the widespread adoption of neobanks and fintech innovations (OECD, 2023). In addition, regulatory adjustments that enable greater interoperability among financial service providers could increase competition and improve consumer outcomes.

Empirical evidence suggests that the elasticity of substitution between traditional banks and neobanks is increasing, meaning that consumers are more willing to switch providers based on service quality, fees, and accessibility (Frost, 2020). The adoption of mobile banking services has grown significantly, especially among younger generations and urban populations (IMF, 2023).

However, the persistence of high switching costs, including regulatory requirements for account portability and reliance on traditional banking rails for transactions, limits the full exploitation of competitive advantages (Gomber et al., 2020). In addition, banks' control over digital payment infrastructure allows them to impose higher costs on neobanks, reducing their competitive advantage (World Bank, 2023).

However, traditional banks dominate the financial infrastructure, including payment networks, ATM access, and interbank transactions, making it difficult for neobanks to operate independently (Banco de la República de Colombia, 2021). Many new banks rely on

Partnerships with traditional banks for transaction processing can increase operational costs and dependence on traditional banks (González-Páramo, 2021).

In addition, consumer confidence in fully digital banks remains a challenge, as many users still prefer traditional banking institutions' perceived security and stability (Klapper et al., 2021). Although neobanks have lower costs and greater accessibility, concerns about cybersecurity, fraud, and gaps in financial literacy limit their adoption, especially among older and rural populations (World Economic Forum, 2022).

Monetary Policy and Bank Concentration

An important line of literature has studied the relationship between monetary policy and banking market structure. For example, Adams and Amel (2010) investigate whether increasing bank concentration in the United States has led to increased market power, concluding that, although consolidation has increased, it has not necessarily translated into greater pricing power. Their findings suggest that structural indicators, such as concentration ratios, may not fully reflect how consolidation affects bank behavior or market competition. This is important when assessing monetary policy transmission in increasingly concentrated markets.

In the context of the euro area, Baarsma and Vooren (2018) analyze how competition within the banking sector conditions the effectiveness of monetary policy, using a panel error correction model for 14 euro area countries, they show that in more competitive banking environments, the transmission of monetary policy-measured through the pass-through of monetary stimulus to long-term interest rates-is faster and more complete. They also highlight the inadequacy of traditional concentration measures (e.g., the HHI) to capture real competitive pressures. They propose using indicators such as the Boone indicator and the Panzar-Rosse H-statistic for more accurate assessments.

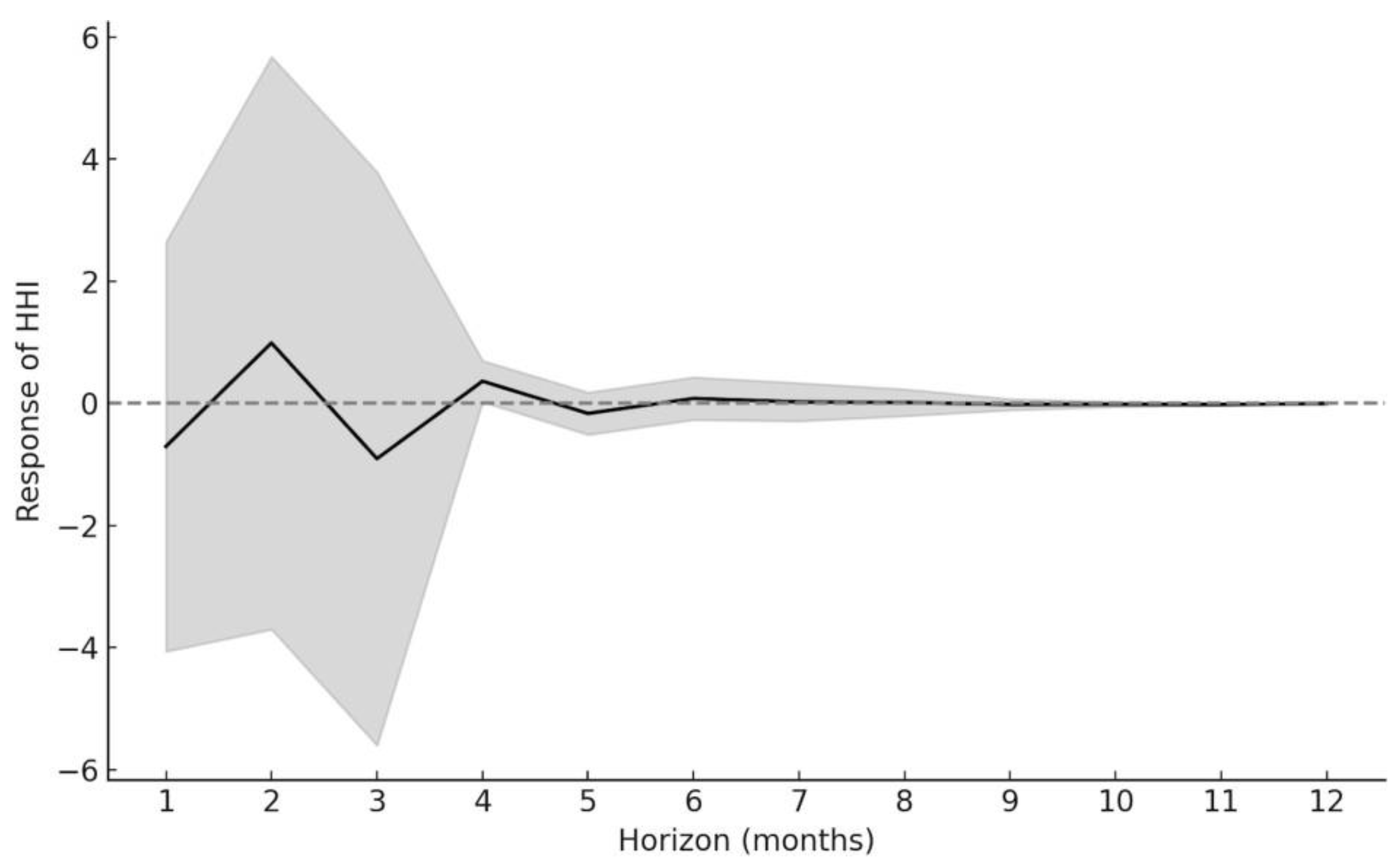

Building on these insights, Jović (2025) advances the debate by examining the reverse causal relationship: whether expansionary monetary policy affects bank concentration. His empirical analysis based on VARs and SCVs of 33 European countries between 2008 and 2020 shows that central bank policy rate cuts - in particular by the ECB - led to significant increases in bank concentration, especially in countries with low initial levels of profitability and weaker

Financial stability. This is known as the second wave of monetary policy effects: the first is a decline in profitability, and the second is a structural shift towards greater market concentration. In particular, the study finds evidence of monetary policy spillovers: ECB policy decisions significantly influenced concentration dynamics even in non-euro area countries such as Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Serbia, where national monetary policies had weaker effects.

Severe (2016) empirically demonstrates that bank concentration significantly dampens the macroeconomic effects of monetary policy. Using panel data from 22 OECD countries on 59 manufacturing sectors, he finds that countries with more concentrated banking systems exhibit lower growth and respond less to interest rate changes. For example, a 100-basis-point reduction in interest rates boosts industrial growth by 0.049% at the average concentration level. However, the policy change almost doubles its effect when the concentration is 5% lower. Severe's study highlights that monopolistic or oligopolistic banking structures limit the effectiveness of monetary policy by reducing the elasticity of lending and investment responses. This idea extends and deepens the microeconomic inefficiency arguments by Berger and Hannan (1998).

Taken together, these studies paint a comprehensive picture of the dual role of bank concentration in the monetary transmission mechanism: on the one hand, it can dampen the responsiveness of lending rates to changes in monetary policy, as dominant banks may be less reactive to interest rate changes; on the other hand, monetary policies themselves can catalyze further concentration by disproportionately benefiting larger and more resilient banks. These findings raise important concerns about the long-term implications of low-interest rate environments, especially for the design of prudential regulation and coordination between monetary and financial stability policies.

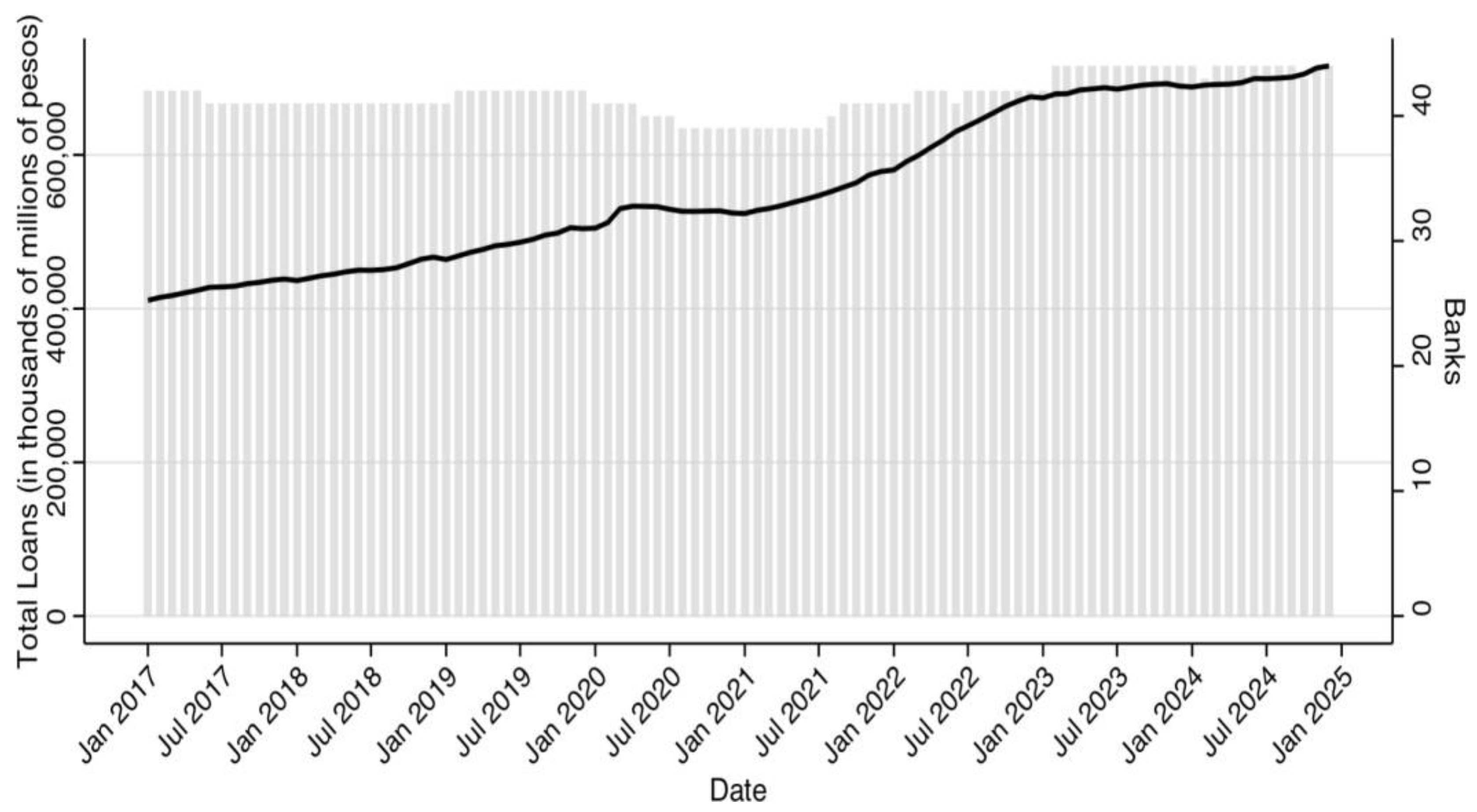

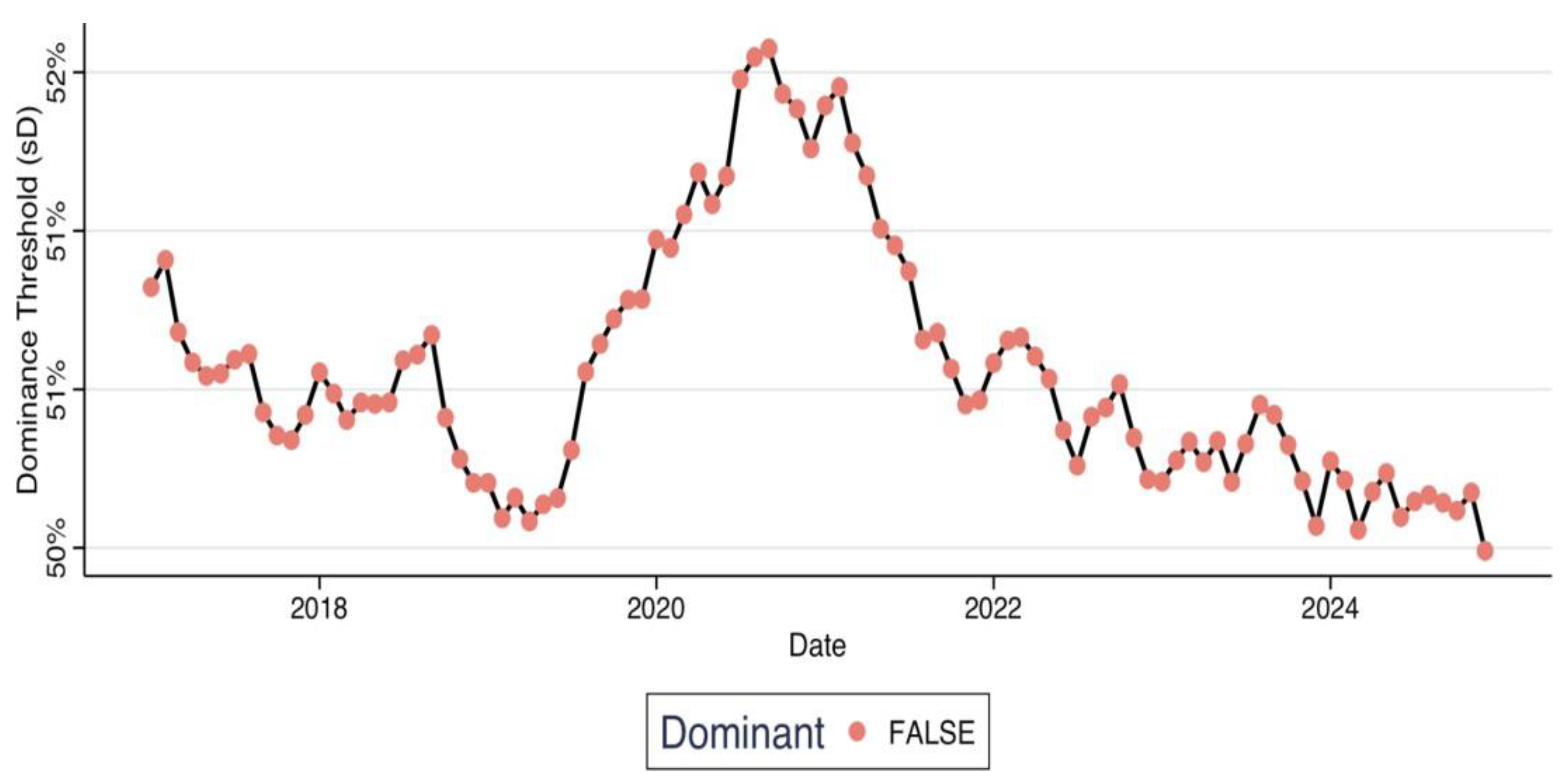

This paper builds on these contributions to explore how market structure conditions banks' responsiveness to monetary impulses in Colombia, while considering whether changes in concentration may be a consequence of monetary policy, not just a moderator. The empirical analysis will apply dominance indices and concentration metrics over time, contextualizing the Colombian banking system within global monetary dynamics and offering new insights into how structure and policy co-evolve.