1. Introduction

Modern software development is entering a new era, defined not just by faster frameworks or smarter IDEs, but by the emergence of intelligent agents that can understand intent and generate code accordingly. As demand for scalable, secure, and high-performance applications intensifies, traditional development workflows are increasingly seen as bottlenecks often limited by human pace, syntax constraints, and repetitive boilerplate tasks.

In this evolving landscape, transformer-based AI models are emerging as powerful co-developers. Originally built for natural language processing tasks, these models now demonstrate remarkable proficiency in interpreting developer intent, understanding structural programming patterns, and producing coherent, executable code. Their ability to parse natural language and align it with formal syntax bridges a long-standing gap between human design thinking and machine-level execution.

Rather than serving as passive code autocompleters, these models are now being reimagined as intelligent assistants capable of full-spectrum development tasks ranging from code generation and summarization to optimization, defect detection, and even security auditing. Such capabilities not only accelerate prototyping but also empower a broader audience including non-programmers to contribute to software development using simple, descriptive prompts.

This paper presents a comprehensive exploration of these next-gen development assistants,” with a focus on transformer-based architectures. We investigate how these models are trained, fine-tuned, and evaluated using standardized benchmarks such as HumanEval, MBPP, CodeXGLUE, and CONCODE

Zheng et al. (

2024). We also explore the systemic challenges they face, including interpretability, safety, and generalization beyond training data.

By reframing code generation as an intent-driven task and transformer models as collaborators rather than tools, we outline a vision for how software engineering can evolve into a more creative, efficient, and inclusive discipline.

2. Related Work

The pursuit of automating software development has undergone a dramatic transformation over the past decade. Early strategies relied heavily on handcrafted rule-based systems and rigid template-based code generators

Nguyen et al. (

2014). While effective in narrowly defined domains, such approaches lacked flexibility and struggled with dynamic logic, non-linear dependencies, and diverse syntactic structures found in real-world codebases.

The advent of statistical machine translation (SMT) introduced a probabilistic approach to the problem, mapping natural language to code based on learned alignments from large datasets

Koziolek et al. (

2020). However, SMT techniques faced limitations in capturing long-range dependencies, maintaining syntax validity, and generalizing across languages or frameworks. As coding tasks grew more complex, the research community shifted toward deep learning models capable of understanding hierarchical patterns within both code and natural language.

Initial neural models leveraged recurrent architectures such as RNNs and LSTMs to generate code token-by-token. While these models offered improved fluency and flexibility, their sequential nature often led to degradation in performance over longer code sequences. Transformers, introduced in the NLP space with their self-attention mechanisms

Vaswani et al. (

2017), quickly emerged as a powerful alternative enabling parallelism, global context understanding, and superior generalization.

Recent transformer-based models like CodeT5, PLBART

Ahmad et al. (

2021), and CodeBERT

Feng et al. (

2020) have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across a wide range of tasks including code summarization, translation, and defect detection. These models benefit from massive pretraining on source code corpora combined with natural language descriptions, allowing them to serve as both encoders and generators in software engineering workflows.

The landscape of benchmarks has also evolved to keep pace. HumanEval

Nijkamp et al. (

2023), MBPP, CodeXGLUE

Lu et al. (

2021), CONCODE, and APPS provide diverse and structured datasets that enable consistent evaluation across code generation, translation, and reasoning tasks. As such, transformer-based approaches now dominate research in intelligent code assistance, pushing the boundaries of automation beyond completion and into full-spectrum software synthesis.

In this work, we build upon these foundations to explore a new framing of transformer models not just as tools for code generation, but as intent-driven development assistants that collaborate with human developers, adapt across languages, and integrate seamlessly into real-world development environments.

3. Intent-Driven Transformer Models for Code Synthesis

The core of modern AI-powered development assistants lies in transformer architectures models originally designed for language tasks

Vaswani et al. (

2017), but now adept at understanding and generating code with impressive fluency and accuracy

Zhang et al. (

2023). These models leverage attention mechanisms to process large input sequences in parallel, enabling them to reason about complex programming logic, long-range dependencies, and multi-line structures.

Unlike older approaches such as LSTMs or GRUs, transformers do not rely on sequential token processing. Instead, they capture global context through self-attention, allowing them to maintain consistency across entire functions or scripts. This characteristic is vital for tasks like conditional logic, loop management, and interdependent variable handling areas where earlier models often struggled

Masoumzadeh (

2023).

Transformers fine-tuned for code have evolved into specialized variants, each optimized for specific use cases such as summarization, translation, completion, or vulnerability detection

Ahmad et al. (

2021);

Lu et al. (

2021). These models often benefit from pretraining on both natural language and code repositories, enabling them to align human intent with executable logic.

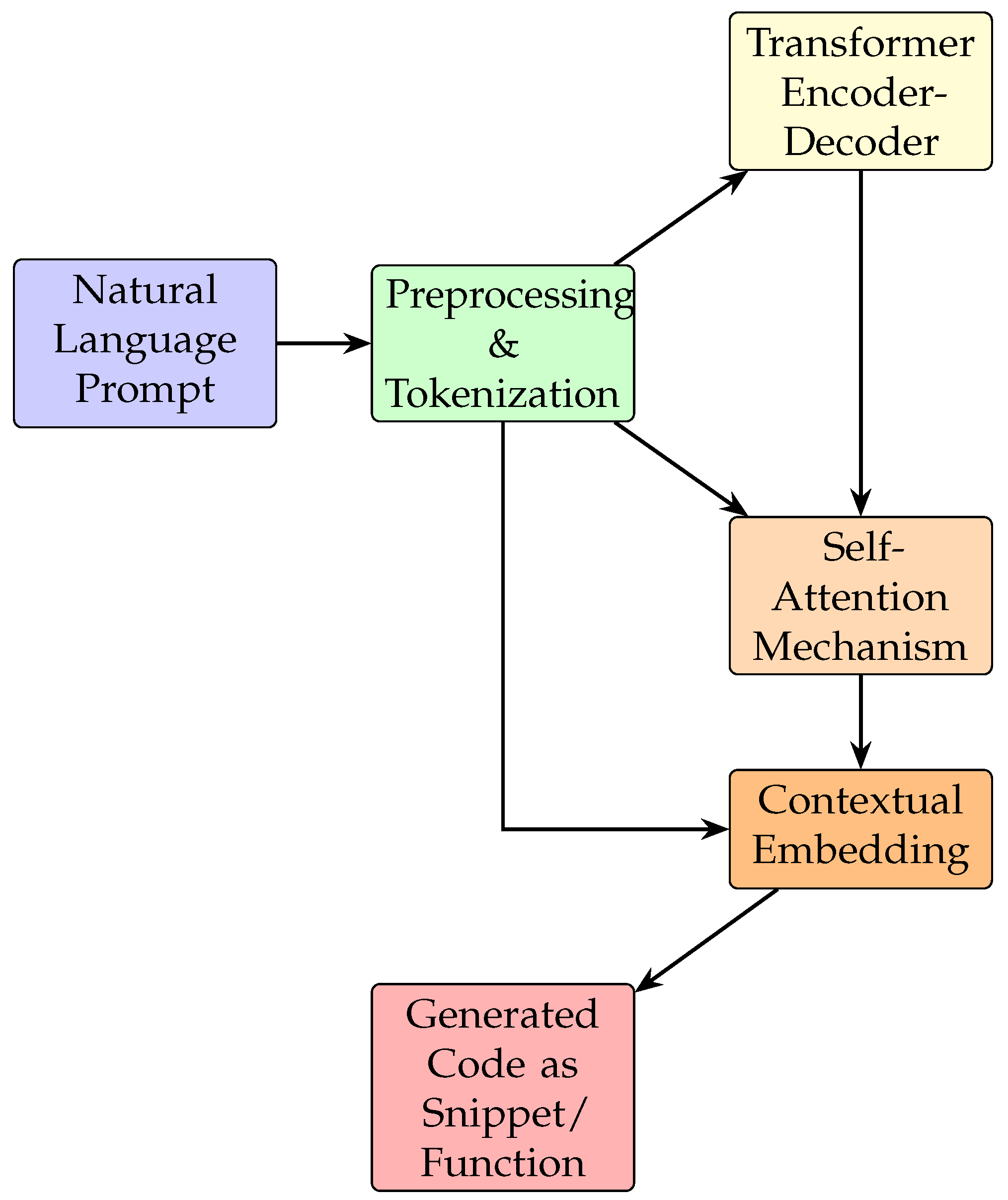

3.1. Input Understanding and Tokenization

The first stage of any intent-driven code generation system is to process and interpret natural language prompts. These prompts often contain programming instructions, feature descriptions, or logic patterns written in informal syntax. Using advanced tokenization techniques such as subword encoding via Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) or SentencePiece the system converts user intent into machine-readable sequences that retain semantic meaning and syntactic cues

Perera and Perera (

2018).

These tokenized sequences are then passed into a transformer-based architecture for context extraction, code generation, or transformation. The preprocessing pipeline ensures that the source language (e.g., English instructions) is aligned with target code tokens across multiple programming languages.

3.2. Transformer Encoding and Context Modeling

Once tokenized, the input is fed into a multi-layered transformer model that leverages self-attention mechanisms to encode positional and contextual relationships. This allows the model to handle complex constructs such as nested conditions, interdependent variables, and function calls with improved accuracy and coherence

Feng et al. (

2020).

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of our code synthesis pipeline using transformer-based development assistants.

The encoder maps the input into dense contextual embeddings, which the decoder then transforms into syntactically correct and semantically relevant code. This process allows for both zero-shot and few-shot generalization

Ahmad et al. (

2021), enabling the model to generate working code for novel problems, provided it has seen similar structural patterns during pretraining.

Beyond architectural innovations, the real power of intent-driven code synthesis lies in the model’s ability to generalize across unseen tasks and adapt to user context in real time. With the increasing adoption of in-IDE coding assistants and chat-based interfaces

Kamatala (

2024), transformer models are now expected to operate in interactive loops refining outputs based on user feedback, contextual cues, and changing requirements. This shift demands not just static generation capability, but dynamic reasoning, code reuse, and incremental completion. Consequently, the design of these systems now includes additional components such as memory buffers, session-based personalization, and reinforcement mechanisms that learn from developer preferences. Such adaptive capabilities mark the transition from passive code generators to proactive collaborators, moving toward truly intelligent development environments.

4. Evaluation Benchmarks and Metrics

Evaluating the capabilities of intent-driven transformer models for code synthesis requires a diverse and standardized set of benchmarks that reflect real-world programming conditions. These benchmarks should span various task types, language domains, and difficulty levels to ensure fair comparison and reproducibility across models

Ahmad et al. (

2021);

Lu et al. (

2021).

Among the most widely used is HumanEval, a benchmark introduced alongside OpenAI Codex

Nijkamp et al. (

2023), which evaluates functional correctness through unit test execution. It includes function-level problems where models are expected to generate complete and correct Python implementations. Similarly, the MBPP (Mostly Basic Programming Problems) dataset targets beginner-friendly coding challenges and is suitable for evaluating prompt sensitivity and few-shot learning performance

Zheng et al. (

2024).

CodeXGLUE offers a more comprehensive platform by combining multiple sub-tasks such as code summarization, code-to-code translation, defect detection, and clone identification across multiple programming languages

Lu et al. (

2021). It serves as a rigorous testbed for general-purpose code understanding and generation capabilities. CONCODE, on the other hand, focuses specifically on Java code generation, mapping textual specifications to class-level or method-level outputs

Nguyen et al. (

2014). This makes it particularly valuable for testing models on formal software engineering tasks. The APPS benchmark extends the evaluation to competitive programming, presenting algorithmic problems that often require multi-step reasoning, logical planning, and abstraction beyond syntactic pattern matching

Zheng et al. (

2024).

To complement these datasets, evaluation metrics play a critical role in quantifying model performance. Commonly adopted metrics include BLEU

Papineni et al. (

2002), which measures n-gram overlap between generated and reference code, and CodeBLEU

Feng et al. (

2020), which incorporates additional dimensions such as AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) similarity and variable matching. These metrics ensure that syntactic fidelity and semantic alignment are both accounted for. Exact Match (EM) is used for strict equivalence comparison, especially in translation tasks. The Pass@k metric, popularized by Codex evaluations

Nijkamp et al. (

2023), determines whether any of the top-k generated outputs pass the associated test cases, providing insight into model confidence and sampling effectiveness.

Despite the effectiveness of these metrics, they also have limitations. BLEU, for instance, may reward superficial overlap without capturing functional correctness. Pass@k may inflate scores when test coverage is sparse or underspecified. Therefore, combining multiple metrics, along with qualitative analysis and human inspection, is often essential for a complete evaluation

Myakala (

2024).

Table 2 presents an overview of the core benchmarks used in this study, including their supported languages and evaluation focus.

As the field matures, there is also a growing emphasis on holistic evaluation frameworks that go beyond isolated metrics. Modern development environments require models to exhibit robustness under ambiguous or incomplete prompts, resilience to adversarial perturbations, and consistency across iterative generations. Therefore, new directions in benchmarking are beginning to incorporate user-centric metrics such as usability, latency, edit distance from final solutions, and even developer satisfaction through human-in-the-loop studies

Le et al. (

2022). These trends highlight the evolving expectations from code generation systems not merely as output generators, but as context-aware assistants that must adapt and improve continuously within complex software engineering pipelines.

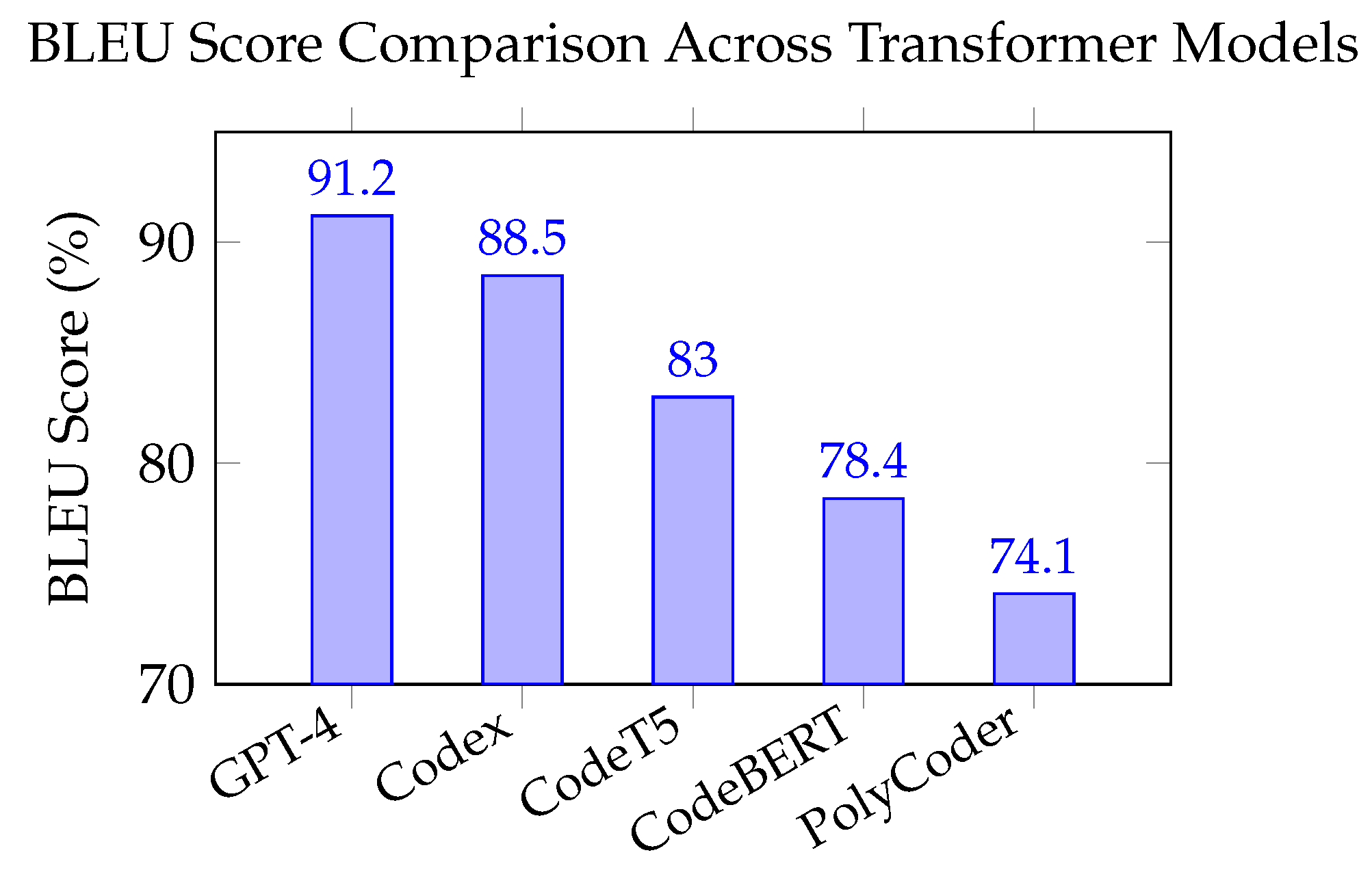

While tabular benchmarks offer structured comparison points, visualizing metric-based performance can often reveal underlying trends more intuitively. BLEU score, in particular, provides a quantifiable view of how closely a model’s output matches ground truth code in terms of surface-level similarity. Though it may not fully capture functional correctness, BLEU remains a widely accepted metric for evaluating sequence generation tasks

Papineni et al. (

2002). Plotting the BLEU scores across leading transformer models allows us to observe the impact of architecture size, training corpus scale, and domain-specific tuning. Such comparative visualizations help in identifying not only the top performers but also the trade-offs associated with lighter, faster models that may still deliver acceptable accuracy in constrained environments.

Figure 2 illustrates the comparative BLEU scores of five prominent transformer-based models evaluated on standard code generation benchmarks. As expected, GPT-4 outperforms other models with a BLEU score of 91.2%, reflecting its advanced language reasoning and few-shot learning capabilities. Codex follows closely at 88.5%, benefiting from its fine-tuning on GitHub-scale repositories. CodeT5 and CodeBERT achieve moderate performance, scoring 83.0% and 78.4% respectively, with strengths in code summarization and classification. PolyCoder, while more specialized in legacy language support, scores 74.1%, indicating its niche utility but limited generalization. These results demonstrate a clear performance gradient tied to model scale, training data diversity, and architectural design validating BLEU as a useful, though not exhaustive, metric for assessing natural language to code generation quality.

5. Integration and Deployment Strategies

The practical impact of transformer-based code generation systems depends not only on their accuracy but also on their ability to integrate seamlessly into existing development environments

Pei Breivold et al. (

2012);

Zhang et al. (

2023). For these models to move from research prototypes to production-grade assistants, they must align with the workflows, performance expectations, and safety requirements of professional software engineering teams.

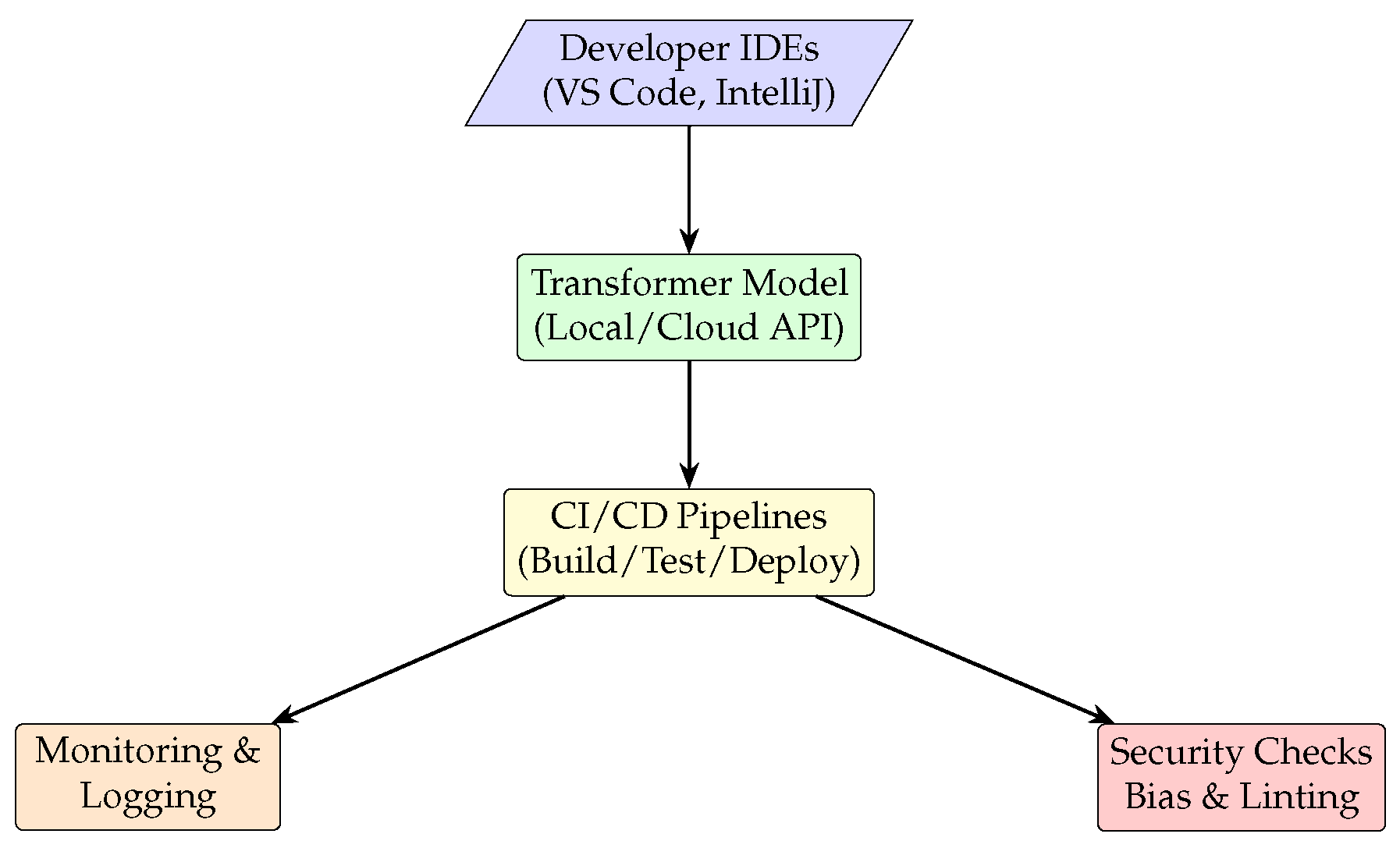

A common integration pathway involves embedding transformer models directly within modern integrated development environments (IDEs) such as Visual Studio Code, IntelliJ, or PyCharm. These integrations enable real-time code suggestions, documentation generation, and context-aware autocompletions. Systems like GitHub Copilot and Amazon CodeWhisperer have already demonstrated the feasibility and productivity benefits of such tooling

Zheng et al. (

2024). These tools leverage model APIs either locally or via cloud endpoints, allowing for interactive feedback loops where developers can refine outputs, accept suggestions, or retrigger completions with modified prompts.

Beyond IDE integration, transformer models are increasingly being deployed in backend engineering workflows such as continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines. For example, models can automatically suggest patches for failing builds, refactor legacy modules, or generate unit tests for new commits

Nguyen et al. (

2014). When integrated with static analysis tools, they can highlight potential bugs or code smells and even generate secure remediation suggestions based on organizational coding standards.

However, successful deployment also requires careful attention to resource constraints, latency, and model adaptability. Lightweight or quantized versions of large transformer models are often preferred in edge or latency-sensitive environments. Similarly, fine-tuning strategies such as parameter-efficient adaptation (e.g., LoRA or adapters) help personalize the assistant’s behavior without incurring the full cost of retraining

Bura (

2025). For organizations concerned about data privacy or IP leakage, hosting models on-premises or within VPC-isolated environments becomes essential

Myakala et al. (

2024).

Finally, monitoring and governance play a critical role in production environments. Logging generated code, flagging potentially insecure or biased outputs, and providing human-in-the-loop override mechanisms ensure responsible use of AI-powered assistants. Such controls allow development teams to benefit from automation while preserving accountability, compliance, and trust

Myakala (

2024).

Figure illustrates a standard deployment pipeline for transformer-based development assistants. It begins with developer interaction in IDEs, where prompts are sent to a transformer model hosted either locally or via cloud APIs. As shown in

Figure 3, the generated code is passed downstream into CI/CD pipelines to support tasks such as test generation, patch suggestions, or code review enhancement. The final stages involve monitoring and security validation, where outputs are logged, analyzed, and checked for quality, bias, and compliance. This modular setup enables flexible integration into engineering workflows, while also supporting operational needs such as scalability, observability, and model governance. Together, the pipeline forms a secure and adaptive framework for deploying AI-powered development tools in real-world environments.

6. Challenges and Ethical Considerations

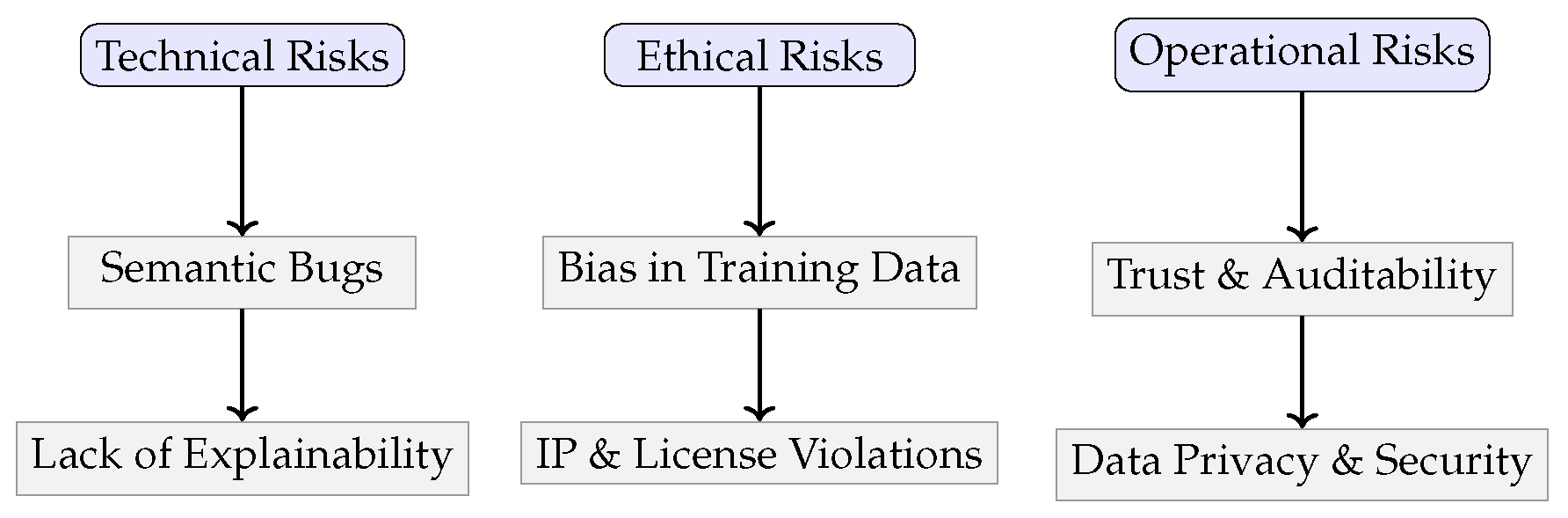

Despite their impressive capabilities, transformer-based code generation systems face several challenges that hinder seamless adoption in production environments

Zhang et al. (

2023). These challenges span technical limitations, ethical implications, and operational risks each of which must be addressed to ensure safe and responsible use of these models.

A primary concern lies in the area of functional reliability. Transformer models, even when pre-trained on vast code repositories, may generate syntactically correct but semantically incorrect code. Such errors, when unnoticed, can introduce security vulnerabilities, runtime failures, or logical bugs

Myakala (

2024). This issue is exacerbated by the lack of interpretability in deep neural architectures, making it difficult for developers to understand why a particular output was generated or how confident the model was in its prediction

Masoumzadeh (

2023).

Equally important are ethical considerations surrounding data provenance and intellectual property. Many transformer models are trained on public code scraped from open-source platforms, often without explicit licensing validation

Koziolek et al. (

2020). As a result, generated code may inadvertently replicate copyrighted patterns, violating software licensing agreements. There is also a risk of bias embedded in training data where models may favor popular frameworks, languages, or styles, potentially marginalizing alternative technologies or underrepresented coding communities

Kamatala et al. (

2025b).

From an operational standpoint, the integration of these systems into enterprise environments raises questions about trust, auditability, and compliance. Development teams need mechanisms to trace model outputs back to decisions, especially in safety-critical domains such as healthcare or automotive software

Myakala et al. (

2024). Governance frameworks must also include human-in-the-loop controls, logging, and override mechanisms to ensure that AI-generated code aligns with organizational policies and ethical standards

Bura (

2025).

Finally, the dynamic nature of software ecosystems introduces challenges in model staleness and generalization. As libraries evolve and languages update, models trained on static corpora may fail to reflect the latest best practices or security patches. Ongoing fine-tuning, continual learning, or retrieval-augmented techniques must be employed to keep these systems current and trustworthy

Kamatala et al. (

2025a).

To better organize and address these multifaceted challenges, it is helpful to categorize them into technical, ethical, and operational risk domains. Technical risks focus on model behavior, accuracy, and reliability; ethical risks emphasize fairness, licensing, and intellectual property; and operational risks pertain to deployment, governance, and compliance. Visualizing these categories not only clarifies their scope but also highlights the intersections where multiple dimensions of risk may influence model adoption and trust.

Figure 4 presents a visual breakdown of these categories, followed by

Table 3 summarizing mitigation strategies for each challenge type.

While the categorization of risks provides conceptual clarity, translating these insights into actionable practices is vital for real-world adoption. Organizations must proactively map each identified risk to corresponding safeguards that align with their engineering, legal, and compliance frameworks. Technical risks require robust evaluation pipelines; ethical risks demand data governance and fairness checks; and operational risks call for mature deployment practices that incorporate traceability and oversight.

Table 3 outlines pragmatic mitigation strategies tailored to each risk category, enabling developers and stakeholders to address vulnerabilities at every stage of the AI-assisted development lifecycle.

As the integration of AI assistants becomes more widespread in professional software engineering workflows, the application of structured mitigation strategies becomes essential not optional. Addressing each risk category with tailored interventions not only reduces technical debt and operational overhead but also fosters organizational trust in AI-enabled tools. Moreover, embedding these strategies early in the development lifecycle during model design, dataset curation, and deployment planning can prevent downstream failures and ethical dilemmas. Ultimately, this risk-aware approach to transformer-based code generation enables teams to harness the benefits of automation while maintaining rigorous control over quality, fairness, and accountability

Bura et al. (

2024).

7. Conclusion and Future Work

Transformer-based development assistants represent a transformative shift in how code is authored, reviewed, and optimized. Through intent-driven synthesis, these models bridge natural language understanding with software logic, enabling developers to rapidly translate ideas into executable code. This paper explored the architectural design of such systems, benchmarked their performance across standard datasets, and analyzed integration strategies that align with modern software engineering practices.

While current transformer models exhibit impressive capabilities in tasks such as code completion, summarization, and translation, their deployment in production settings still demands careful attention to accuracy, ethics, and operational reliability. We presented a holistic breakdown of the associated risks technical, ethical, and operational and mapped them to mitigation strategies that development teams can adopt across the lifecycle of AI-assisted tooling.

Furthermore, the integration of these models into development workflows is evolving beyond IDE plugins. CI/CD pipelines, static analysis, security patching, and compliance monitoring are becoming high-value targets for intelligent assistants. This shift highlights the growing need for explainable and accountable AI systems capable of maintaining development velocity while ensuring governance and trust.

Looking ahead, the future of intelligent development assistants lies in adaptability, modularity, and real-time responsiveness. Techniques such as retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), on-device transformer inference, and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF) are poised to play central roles in making models more context-sensitive and cost-efficient. In particular, hybrid pipelines that combine large language models (LLMs) with symbolic reasoning or rule-based systems may unlock more reliable code synthesis in high-stakes domains such as finance, automotive, and aerospace.

Another promising direction is the development of domain-specialized foundation models fine-tuned on narrow corpora such as cybersecurity codebases, scientific computing libraries, or embedded systems. These models could act as expert assistants within vertical industries, improving both precision and trust in generated outputs. Complementary advances in multi-modal learning (e.g., incorporating GUI layouts or UML diagrams) may also enable assistants to reason across design layers, bringing us closer to full-stack AI-powered engineering.

As transformer-based assistants continue to mature, their long-term success will depend on fostering transparency, human-AI collaboration, and responsible deployment practices. By embedding principles of safety, fairness, and user feedback into model development cycles, the next generation of AI-powered tools can evolve from passive generators into proactive teammates augmenting human creativity, reducing engineering overhead, and accelerating the future of software development.

Acknowledgments

All the authors contributed equally and would like to acknowledge the contributions of researchers and industry experts whose insights have shaped the discourse on Next-Gen Development Assistants- Leveraging Transformer Architectures for Intent-Driven Code Synthesis. This independent research does not refer to any specific institutions, infrastructure, or proprietary data.

References

- Ahmad, W. U., Chakraborty, S., Ray, B., and Chang, K.-W. (2021). Unified pre-training for program understanding and generation.

- Bura, C. (2025). Enriq: Enterprise neural retrieval and intelligent querying. REDAY - Journal of Artificial Intelligence & Computational Science.

- Bura, C., Jonnalagadda, A. K., and Naayini, P. (2024). The role of explainable ai (xai) in trust and adoption. Journal of Artificial Intelligence General science (JAIGS) ISSN: 3006-4023, 7(01):262–277.

- Feng, Z., Guo, D., Tang, D., Duan, N., Feng, X., Gong, M., Shou, L., Qin, B., Liu, T., Jiang, D., and Zhou, M. (2020). Codebert: A pre-trained model for programming and natural languages.

- Kamatala, S. (2024). Ai agents and llms revolutionizing the future of intelligent systems. International Journal of Scientific Research and Engineering Development, 7(6).

- Kamatala, S., Jonnalagadda, A. K., and Naayini, P. (2025a). Transformers beyond nlp: Expanding horizons in machine learning. Iconic Research And Engineering Journals, 8(7).

- Kamatala, S., Naayini, P., and Myakala, P. K. (2025b). Mitigating bias in ai: A framework for ethical and fair machine learning models. Available at SSRN 5138366.

- Koziolek, H., Burger, A., Platenius-Mohr, M., Rückert, J., Abukwaik, H., Jetley, R. P., and Abdulla, P. (2020). Rule-based code generation in industrial automation: Four large-scale case studies applying the cayenne method. 2020 IEEE/ACM 42nd International Conference on Software Engineering: Software Engineering in Practice (ICSE-SEIP), pages 152–161.

- Le, H., Wang, Y., Gotmare, A. D., Savarese, S., and Hoi, S. (2022). CodeRL: Mastering code generation through pretrained models and deep reinforcement learning. In Oh, A. H., Agarwal, A., Belgrave, D., and Cho, K., editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Lu, S., Guo, D., Ren, S., Huang, J., Svyatkovskiy, A., Blanco, A., Clement, C., Drain, D., Jiang, D., Tang, D., Li, G., Zhou, L., Shou, L., Zhou, L., Tufano, M., Gong, M., Zhou, M., Duan, N., Sundaresan, N., Deng, S. K., Fu, S., and Liu, S. (2021). Codexglue: A machine learning benchmark dataset for code understanding and generation.

- Masoumzadeh, S. S. (2023). From rule-based systems to transformers: A journey through the evolution of natural language processing. Accessed: 2025-04-19.

- Myakala, P. K. (2024). Beyond accuracy: A multi-faceted evaluation framework for real-world ai agents. International Journal of Scientific Research and Engineering Development, 7(6).

- Myakala, P. K., Jonnalagadda, A. K., and Bura, C. (2024). Federated learning and data privacy: A review of challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 5(12).

- Nguyen, A. T., Nguyen, T. T., and Nguyen, T. N. (2014). Migrating code with statistical machine translation. In Companion Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Software Engineering, ICSE Companion 2014, page 544–547, New York, NY, USA. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Nijkamp, E., Pang, B., Hayashi, H., Tu, L., Wang, H., Zhou, Y., Savarese, S., and Xiong, C. (2023). Codegen: An open large language model for code with multi-turn program synthesis.

- Papineni, K., Roukos, S., Ward, T., and Zhu, W.-J. (2002). Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL ’02, page 311–318, USA. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Pei Breivold, H., Crnkovic, I., and Larsson, M. (2012). A systematic review of software architecture evolution research. Information & Software Technology, 54:16–40.

- Perera, K. J. P. G. and Perera, I. (2018). A rule-based system for automated generation of serverless-microservices architecture. In 2018 IEEE International Systems Engineering Symposium (ISSE), pages 1–8.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser,., and Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 30.

- Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Wang, S., and Zou, X. (2023). Transformers for natural language processing: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13504.

- Zheng, Q., Xia, X., Zou, X., Dong, Y., Wang, S., Xue, Y., Wang, Z., Shen, L., Wang, A., Li, Y., Su, T., Yang, Z., and Tang, J. (2024). Codegeex: A pre-trained model for code generation with multilingual benchmarking on humaneval-x.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).