Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Non-Commutative BCQG: Triad-Extended Formulation

3. BCQG Friedmann’s-Type Equations and Hubble Rate

4. Dynamical Equations

4.1. First-order Hamilton dynamical equations

4.2. Second-order Hamilton dynamical equations

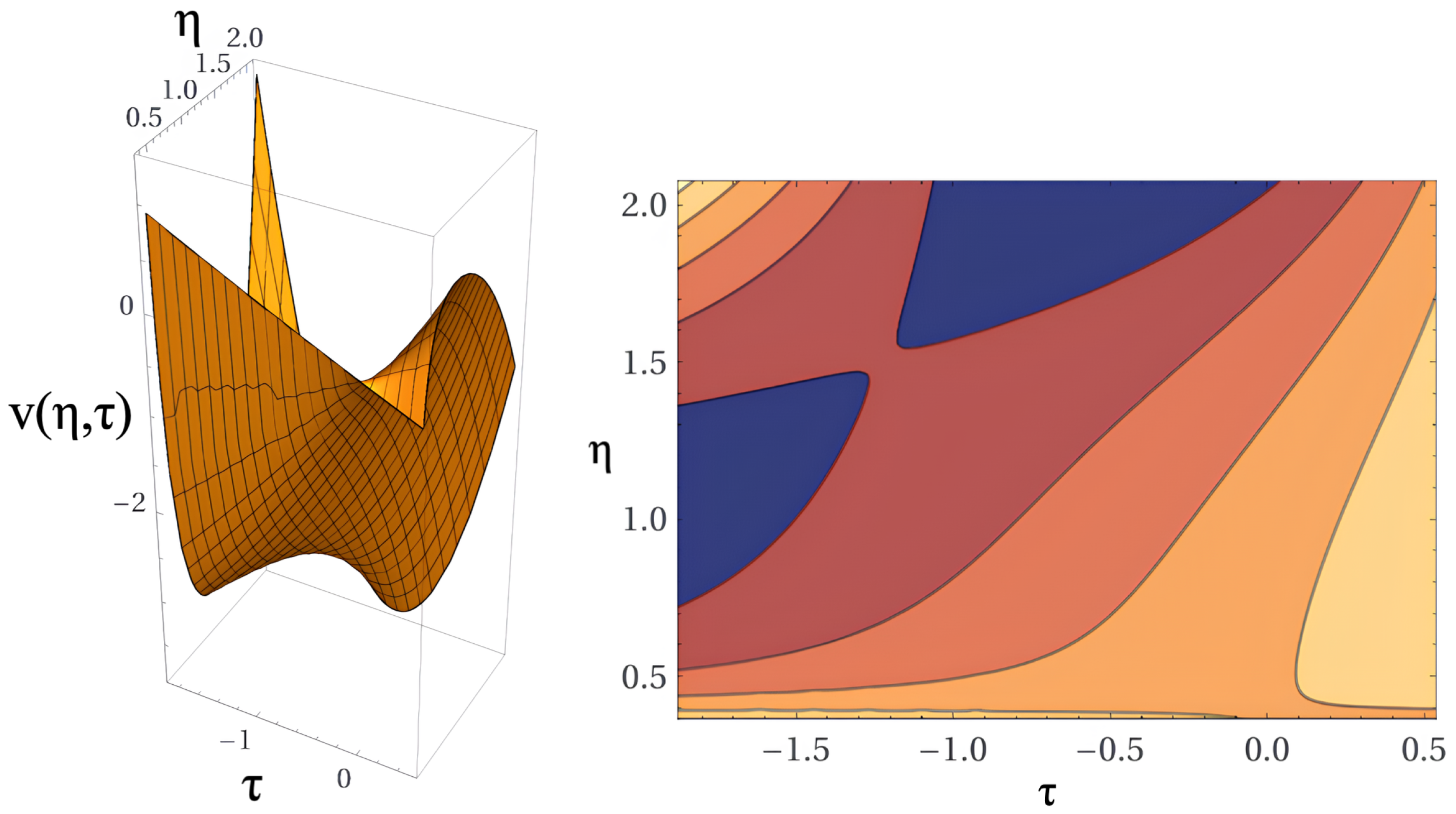

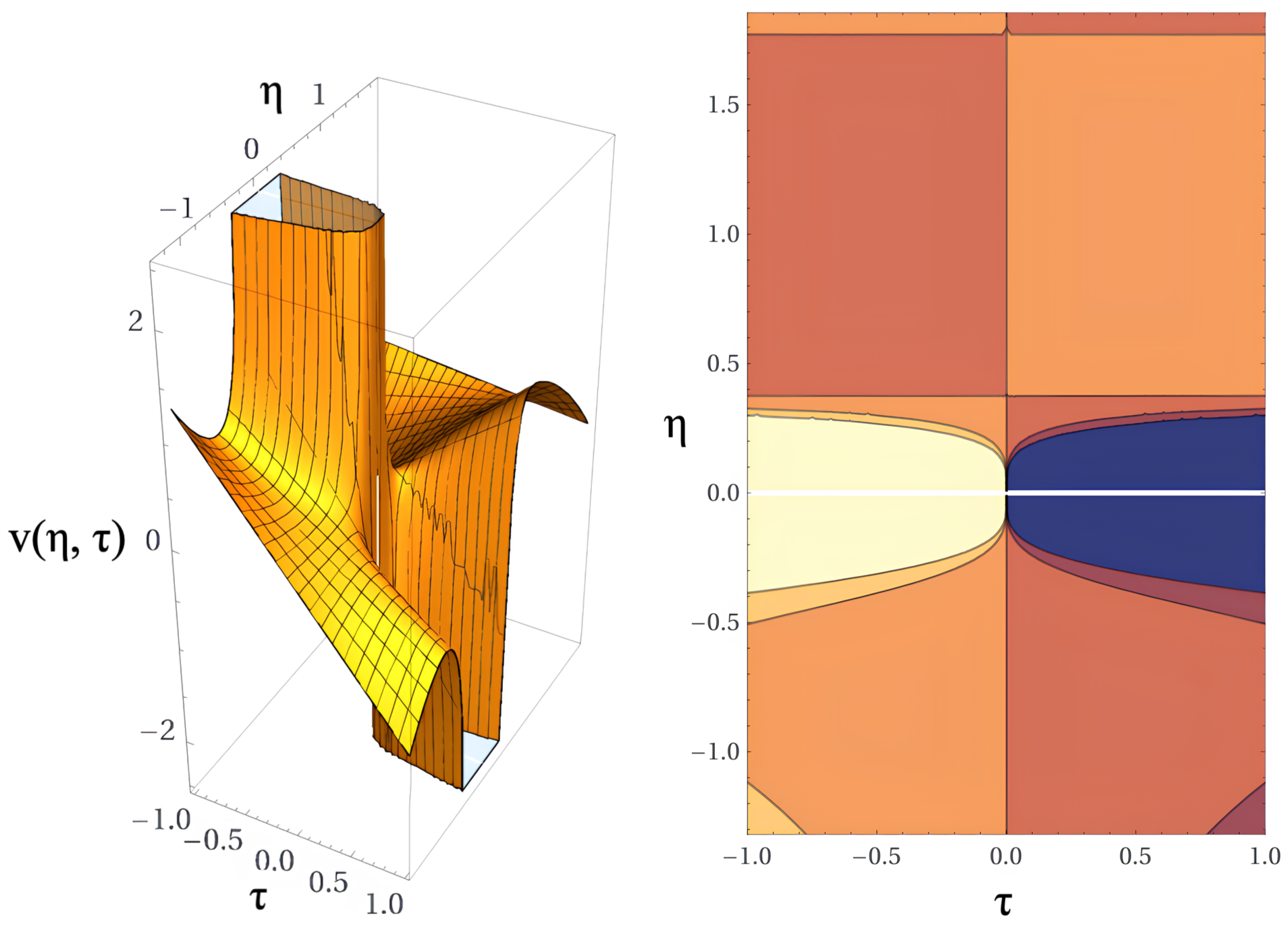

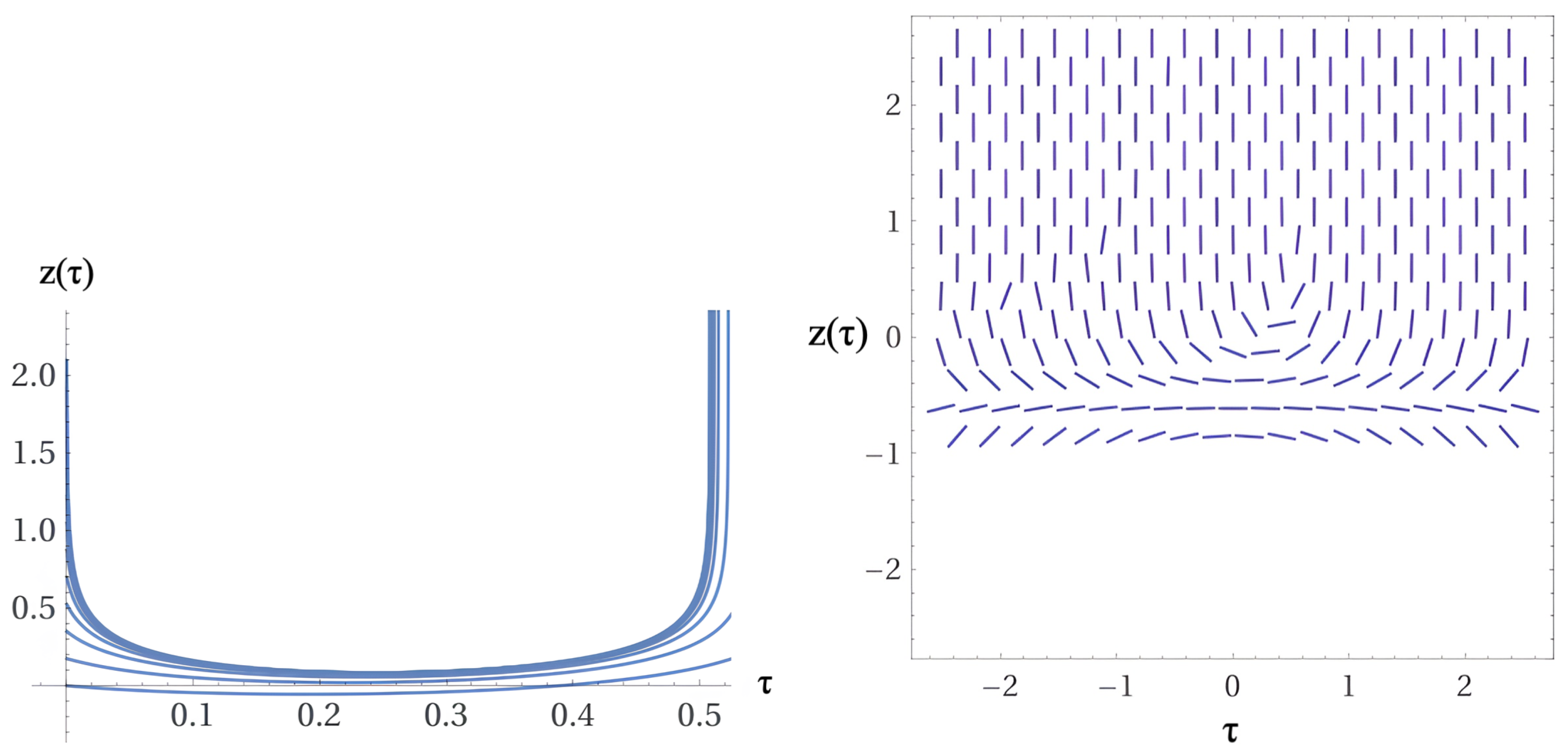

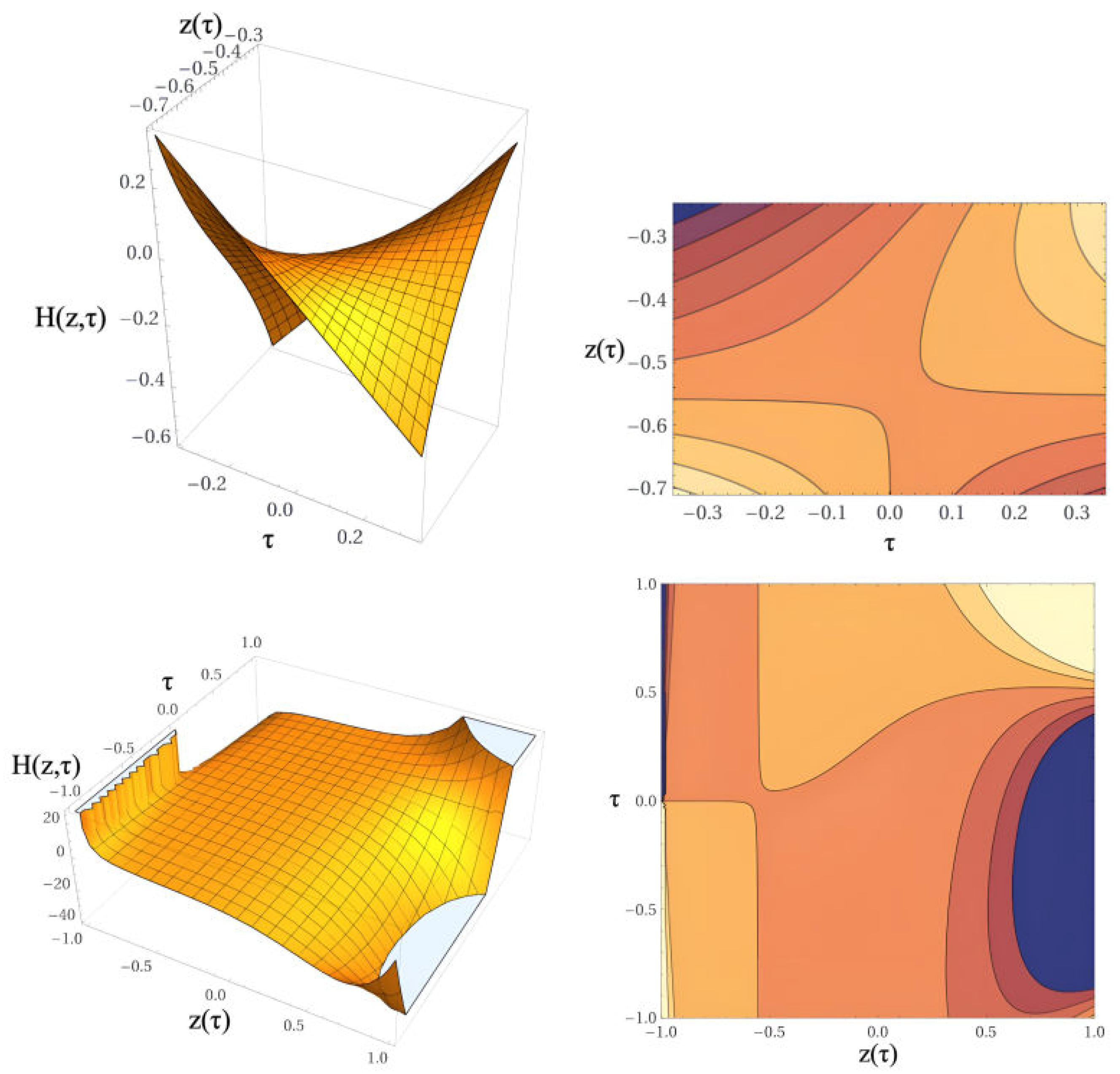

4.3. Solutions

5. BCQG Cosmological Parameters

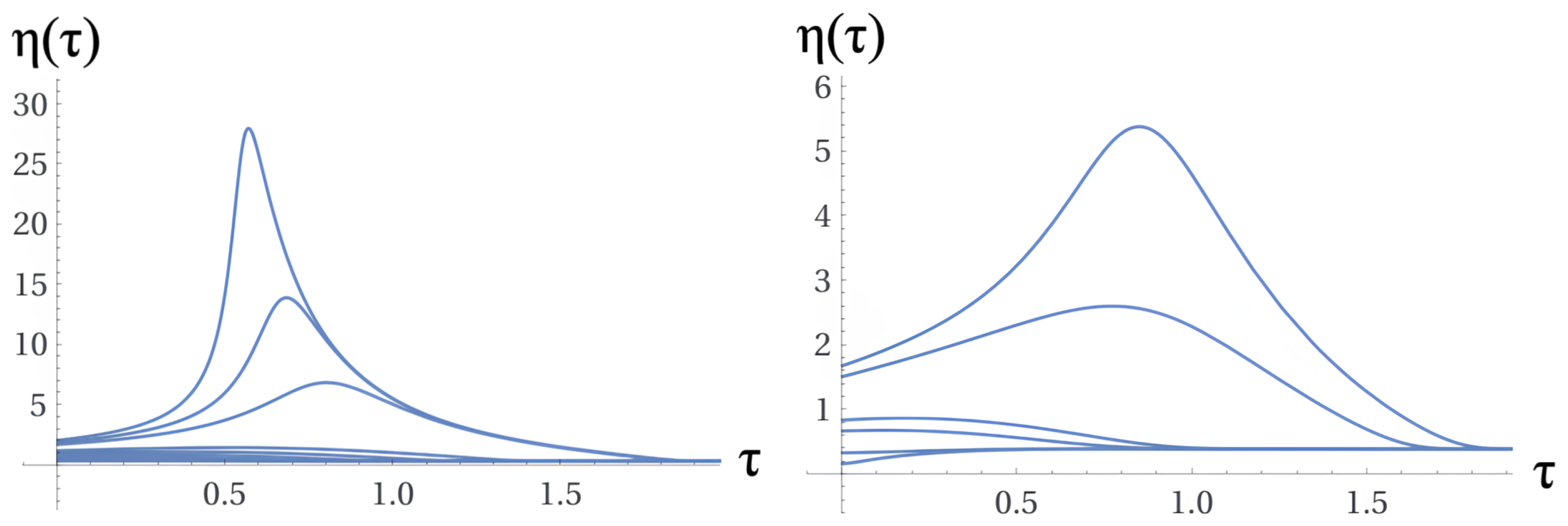

5.1. Solutions - recursive approach

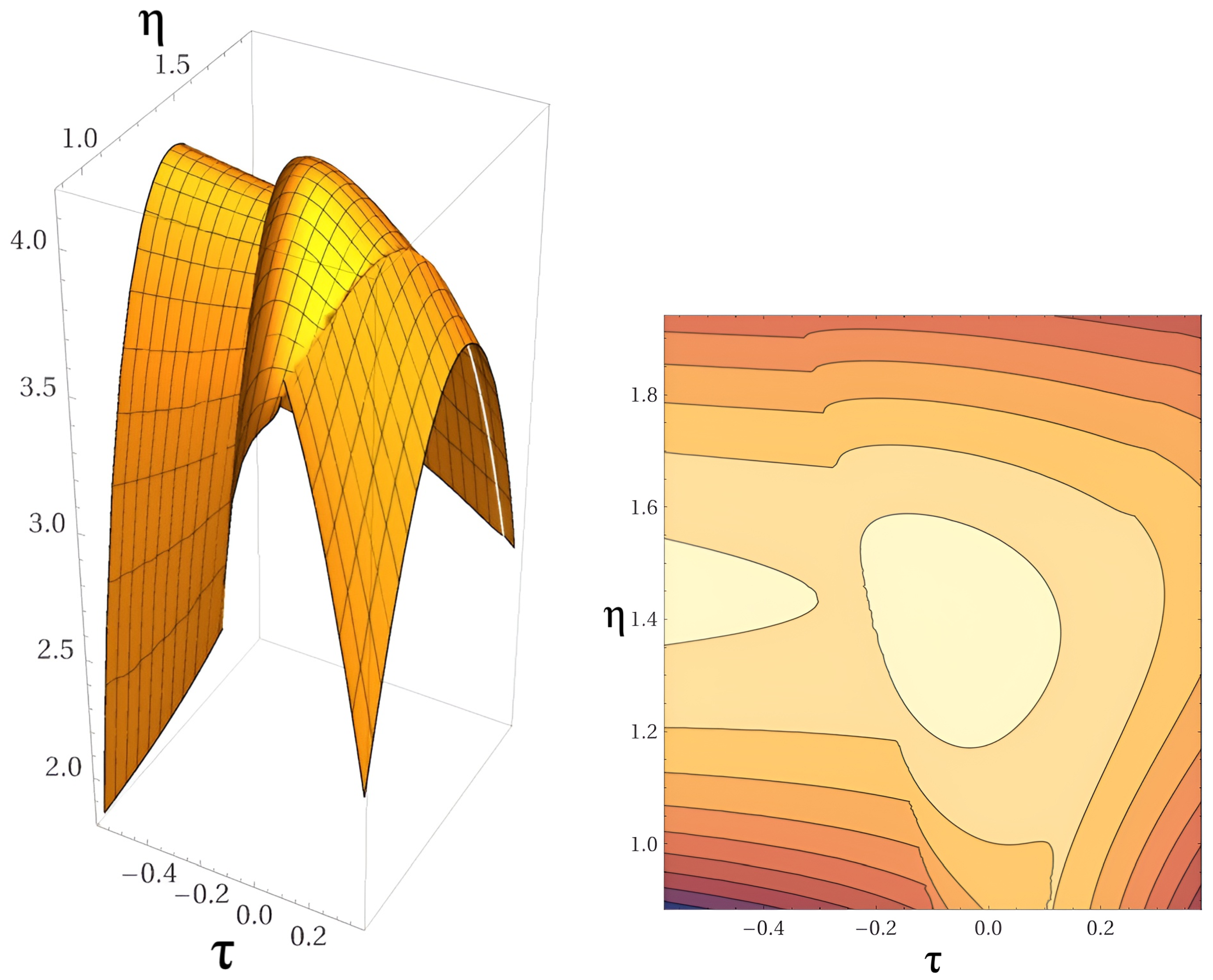

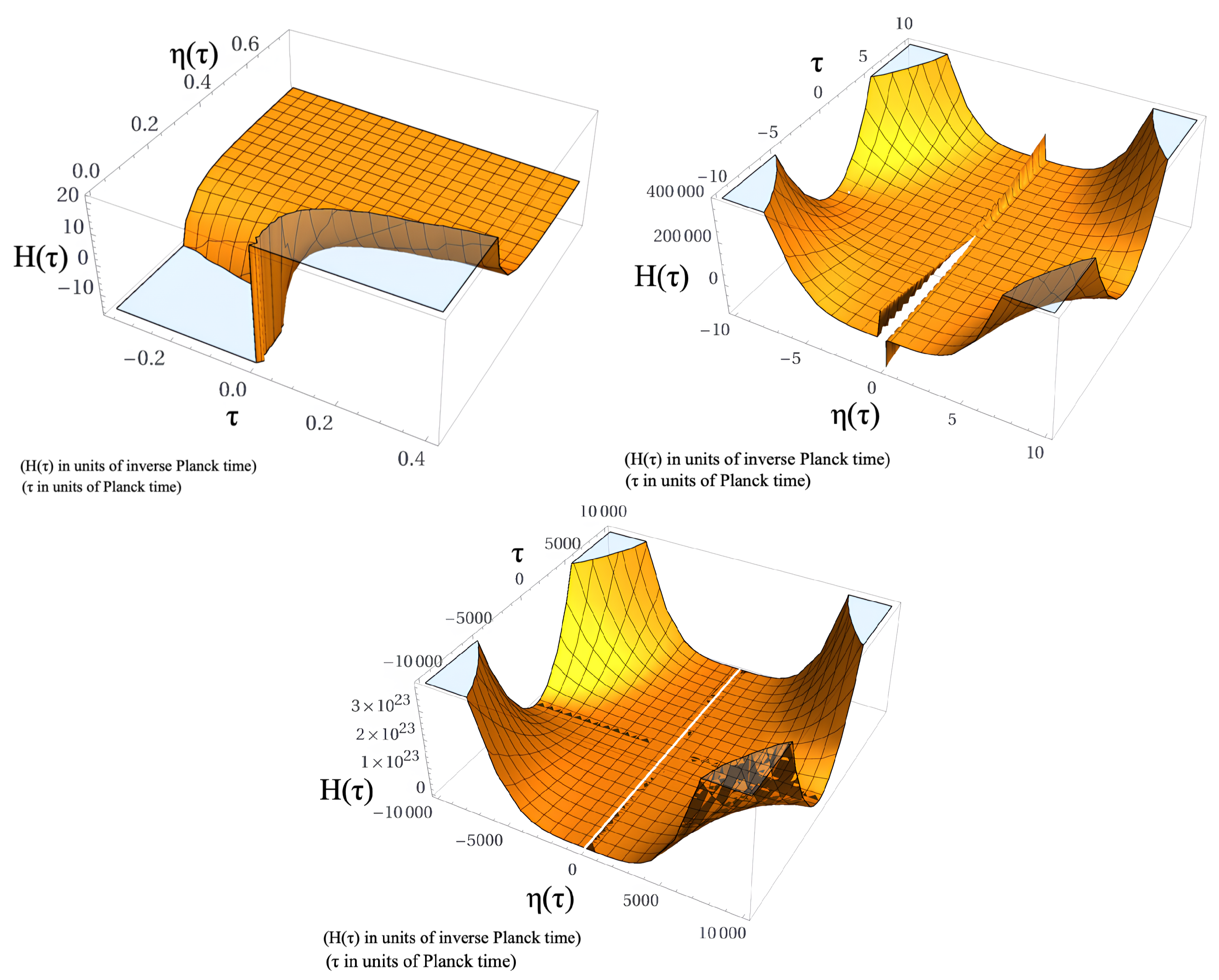

5.2. BCQG Hubble parameter (Hubble rate)

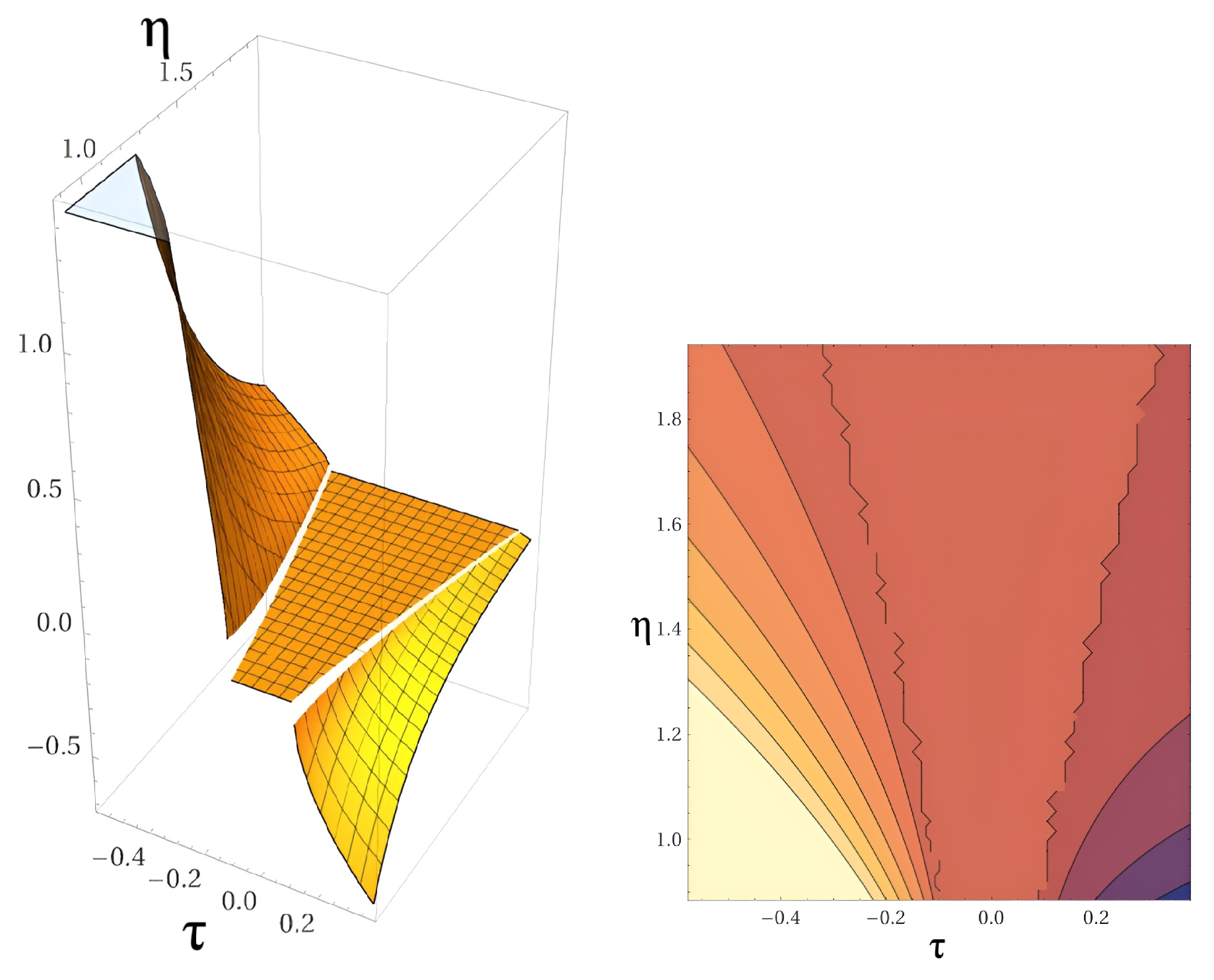

5.3. BCQG redshift cosmological parameter

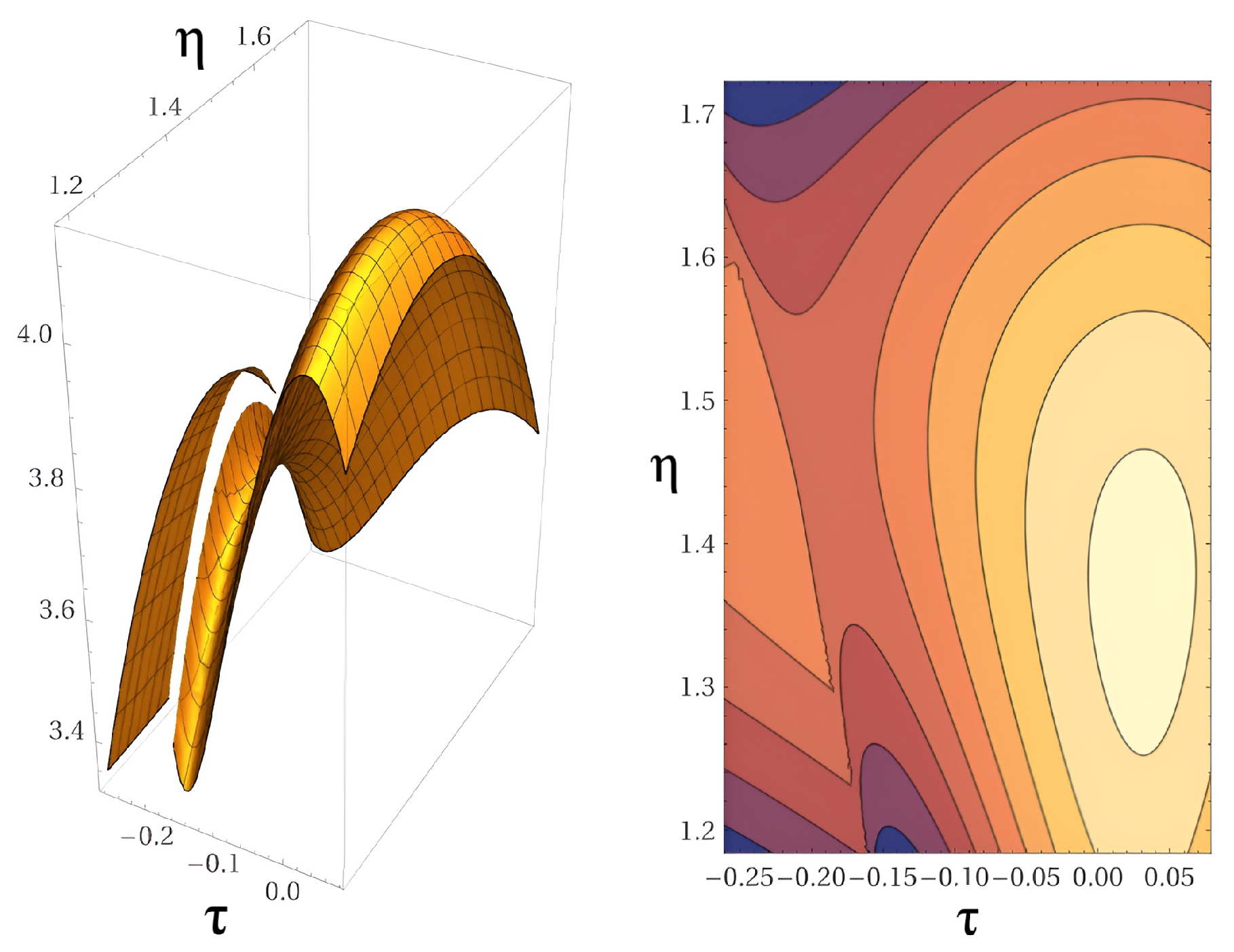

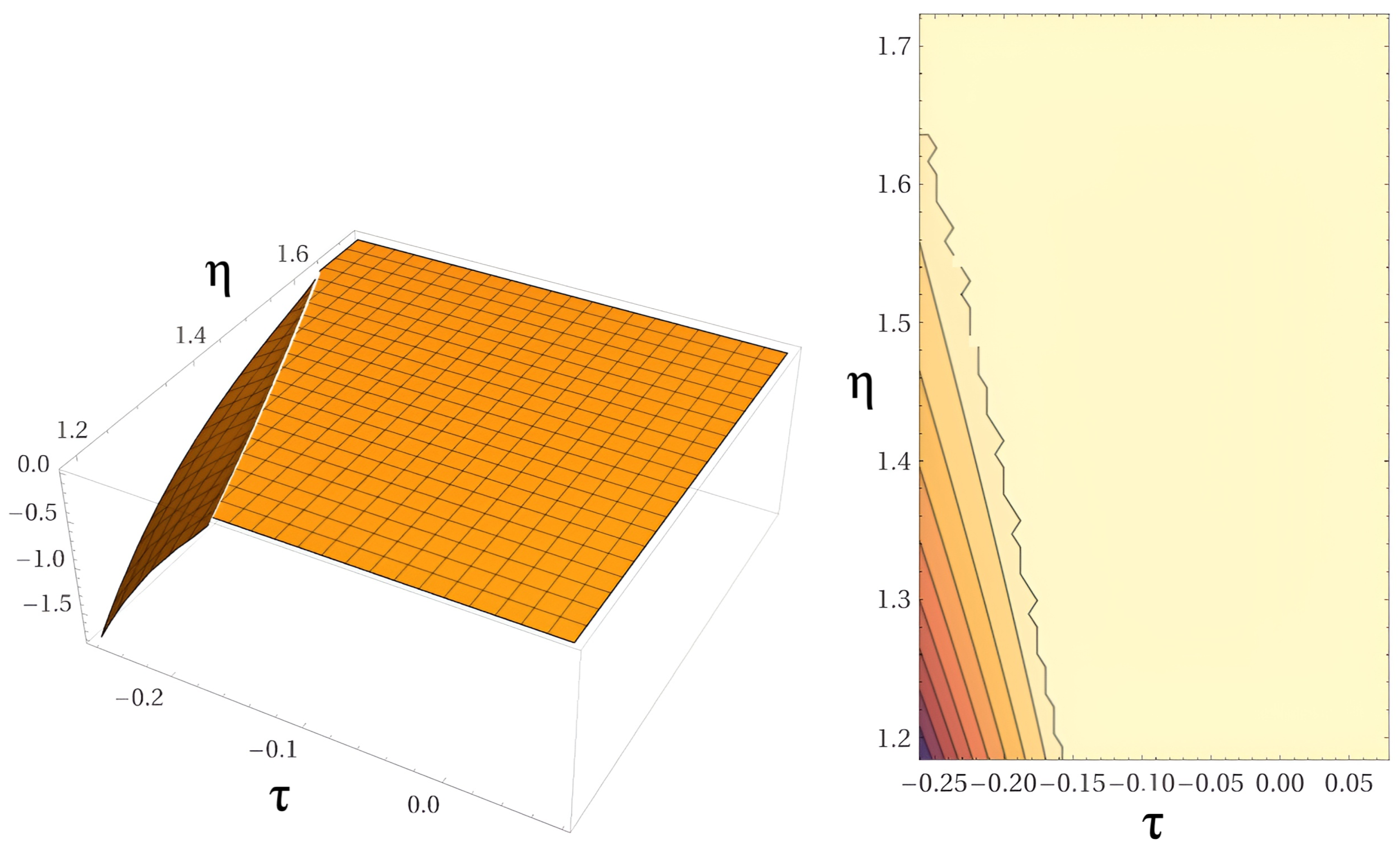

5.4. Redshift dependence of the BCQG Hubble parameter

6. Final Remarks and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Zen Vasconcellos, C.A.; Hess, P.O.; de Freitas Pacheco, J.; Weber, F.; Bodmann, B.; Hadjimichef, D.; Naysinger, G.; Netz-Marzola, M.; Razeira, M. The Accelerating Universe in a Noncommutative Analytically Continued Foliated Quantum Gravity. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2024.

- Zen Vasconcellos, C.A.; Hess, P.O.; de Freitas Pacheco, J.; Weber, F.; Bodmann, B.; Hadjimichef, D.; Naysinger, G.; Netz-Marzola, M.; Razeira, M. Cosmic inflation in an extended non-commutative foliated quantum gravity: the wave function of the universe. Submitted to Universe 2025.

- Friedman, A. Über die Krümmung des Raumes. Zeitschrift für Physik 1922, 10, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G. Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques. Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles 1927, A47, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, H.P. Kinematics and World-Structure. Astrophysical Journal 1935, 82, 248–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.G. On Milne’s Theory of World-Structure. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 1937, 42, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnowitt, R.; Deser, S.; Misner, C.W. The dynamics of general relativity (republication). General Relativity and Gravitation 2008, 40, 1997–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen Vasconcellos, C.A.; Hadjimichef, D.; Razeira, M.; Volkmer, G.; Bodmann, B. Pushing the Limits of General Relativity Beyond the Big Bang Singularity. Astron. Nachr. 2019, 340, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen Vasconcellos, C.A.; Hess, P.O.; Hadjimichef, D.; Bodmann, B.; Razeira, M.; Volkmer, G.L. Pushing the Limits of Time Beyond the Big Bang Singularity: The branch cut universe. Astron. Nachr. 2021, 342(5), 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen Vasconcellos, C.A.; Hess, P.O.; Hadjimichef, D.; Bodmann, B.; Razeira, M.; Volkmer, G.L. Pushing the Limits of Time Beyond the Big Bang Singularity: Scenarios for the branch-cut Universe. Astron. Nachr. 2021, 342(5), 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmann, B.; Zen Vasconcellos, C.A.; Hess, P.O.; de Freitas Pacheco, J.A.; Hadjimichef, D.; Razeira, M.; Degrazia, G.A. A Wheeler–DeWitt Quantum Approach to the Branch-Cut Gravitation with Ordering Parameters. Universe 2023, 9(6), 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmann, B.; Hadjimichef, D.; Hess, P.O.; de Freitas Pacheco, J.; Weber, F.; Razeira, M.; Degrazia, G.A.; Marzola, M.; Zen Vasconcellos, C.A. A Wheeler-DeWitt Non-commutative Quantum Approach to the Branch-cut Gravity. Universe 2023, 9(10), 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyl, H. Reine Infinitesimalgeometrie. Math. Zeit. 1918, 2, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyl, H. Über die Definitionen der mathematischen Grundbegriffe. Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Blatter 1910, 7, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Guth, A.H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Phys. Rev. 1981, D23, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, A.H. Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series, Vol. 2: Measuring and Modeling the Universe; W. L. Freedman (ed.); Cambridge Univ. Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolami, O.; Zarro, C.A.D. Hořava-Lifshitz quantum cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 044042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.I.; Misonoh, Y.; Kobayashi, T. Oscillating Bianchi IX Universe in Hořava-Lifshitz Gravity. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 064024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alfaro, V.; Fubini, S.; Furlan, G. Conformal invariance in quantum mechanics. Nuovo Cimento A 1976, 34, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, J.; Peleg, Y. Self-adjoint Wheeler-DeWitt operators, the problem of time, and the wave function of the Universe. Phys.Rev. D 1995, 52, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A. Über die Möglichkeit einer Welt mit konstanter negativer Krümmung des Raumes. Zeitschrift für Physik 1924, 21, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W.; Hertog, T.J. A smooth exit from eternal inflation? High Energ. Phys. 2018, 04, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.; Bazin, M.; Schiffer, M. Introduction to General Relativity; McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.F.R. The arrow of time and the nature of spacetime. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 2013, 44 (3), 242–262.

- Ellis, G.F.R. Time really exists! The evolving block universe. euresis journal 2014, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. The strange equation of quantum gravity. Class. Quantum Grav. 2015, 32, 124005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Venn, A.; Vasak, D.; Kirsch, J.; Struckmeier, J. Torsional dark energy in quadratic gauge gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 2023, 83, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).