Submitted:

08 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

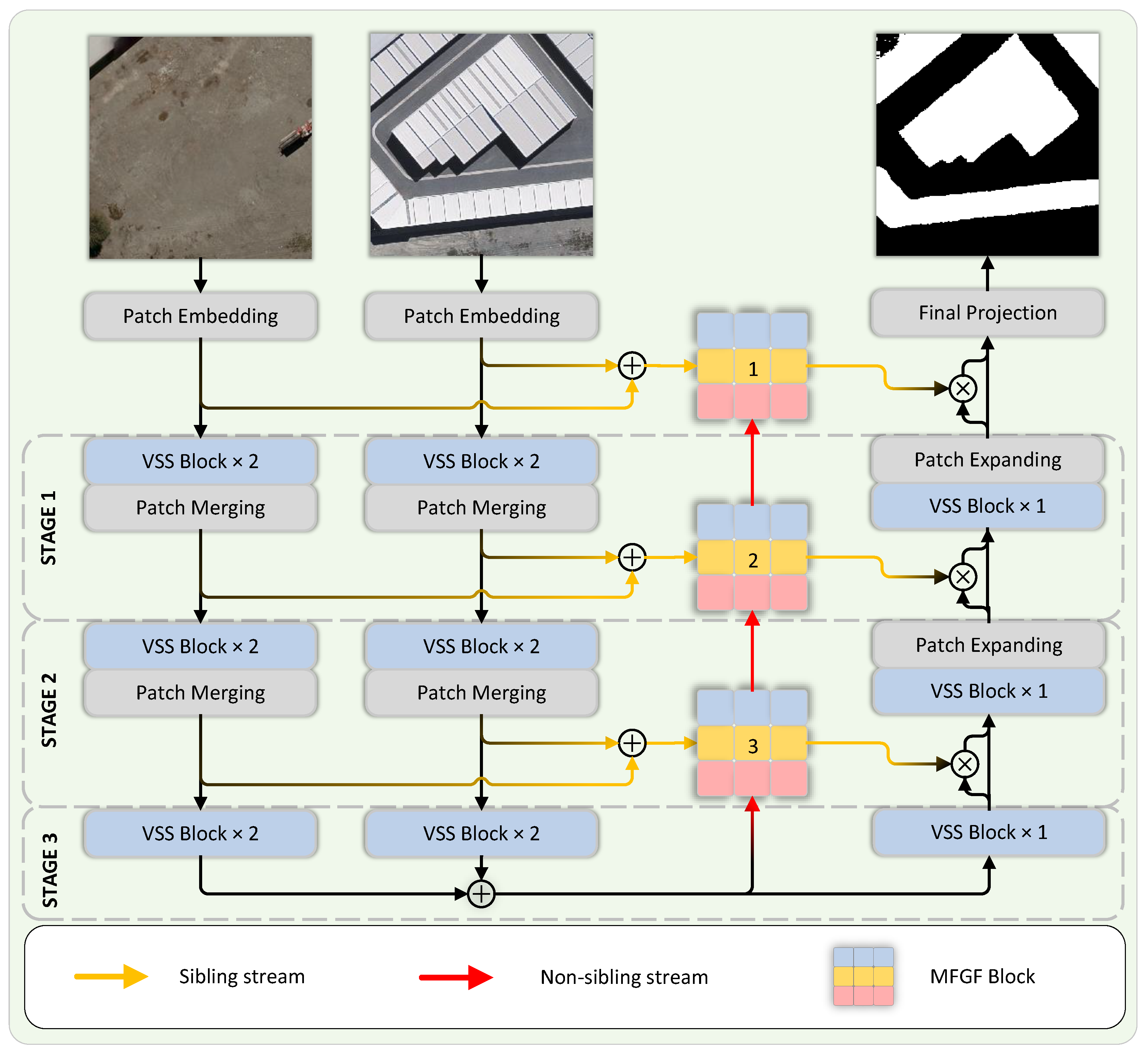

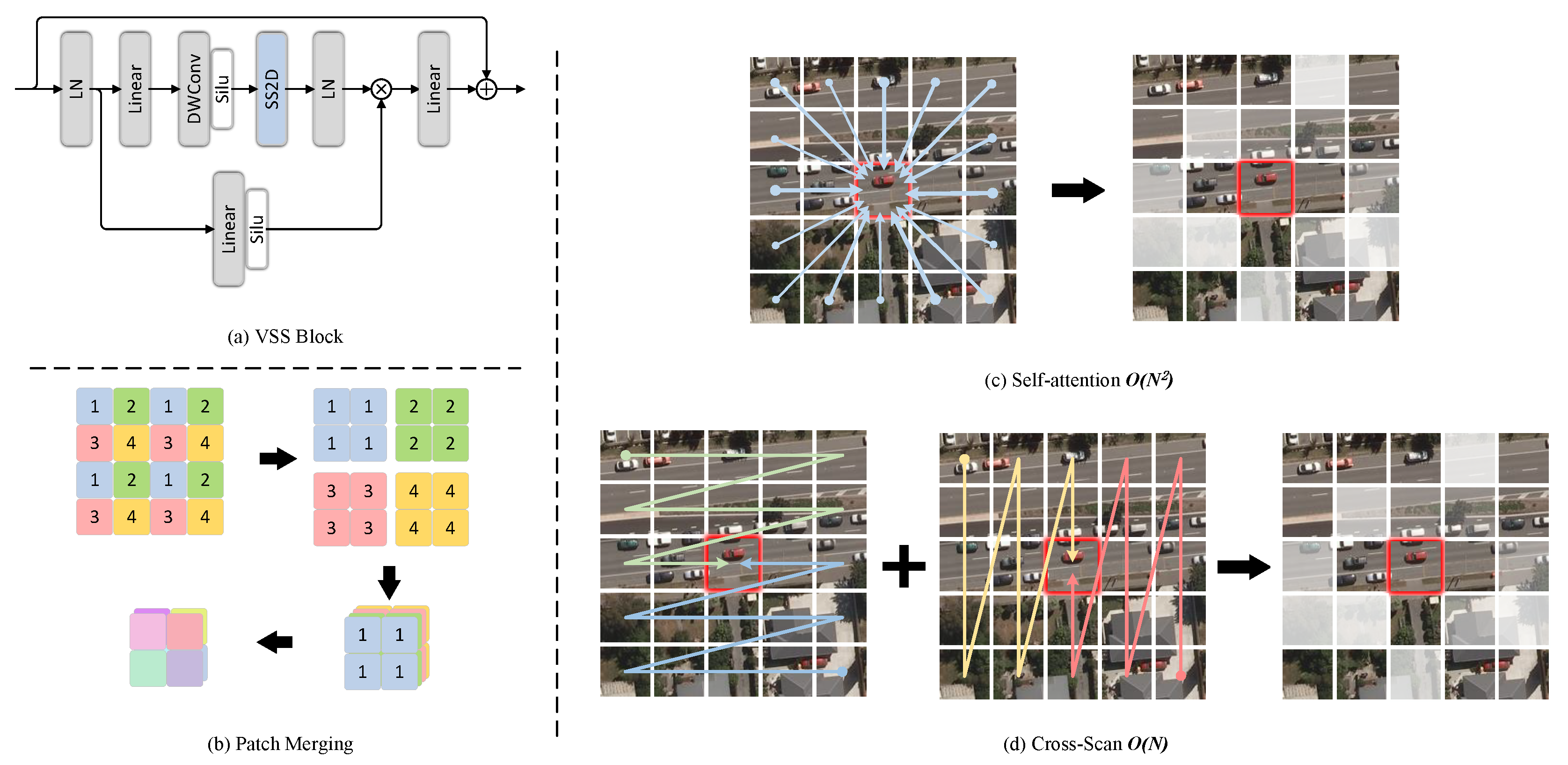

- In light of the characteristics of the VMamba model, a simple yet effective model, VMMCD, is proposed. The architecture of this model has been subject to a lightweight design and employs Patch Merging to conduct hierarchical processing of tokens across various scales, thereby facilitating the global spatiotemporal modeling based on tokens by the VMamba backbone, which effectively guarantees both speed and accuracy.

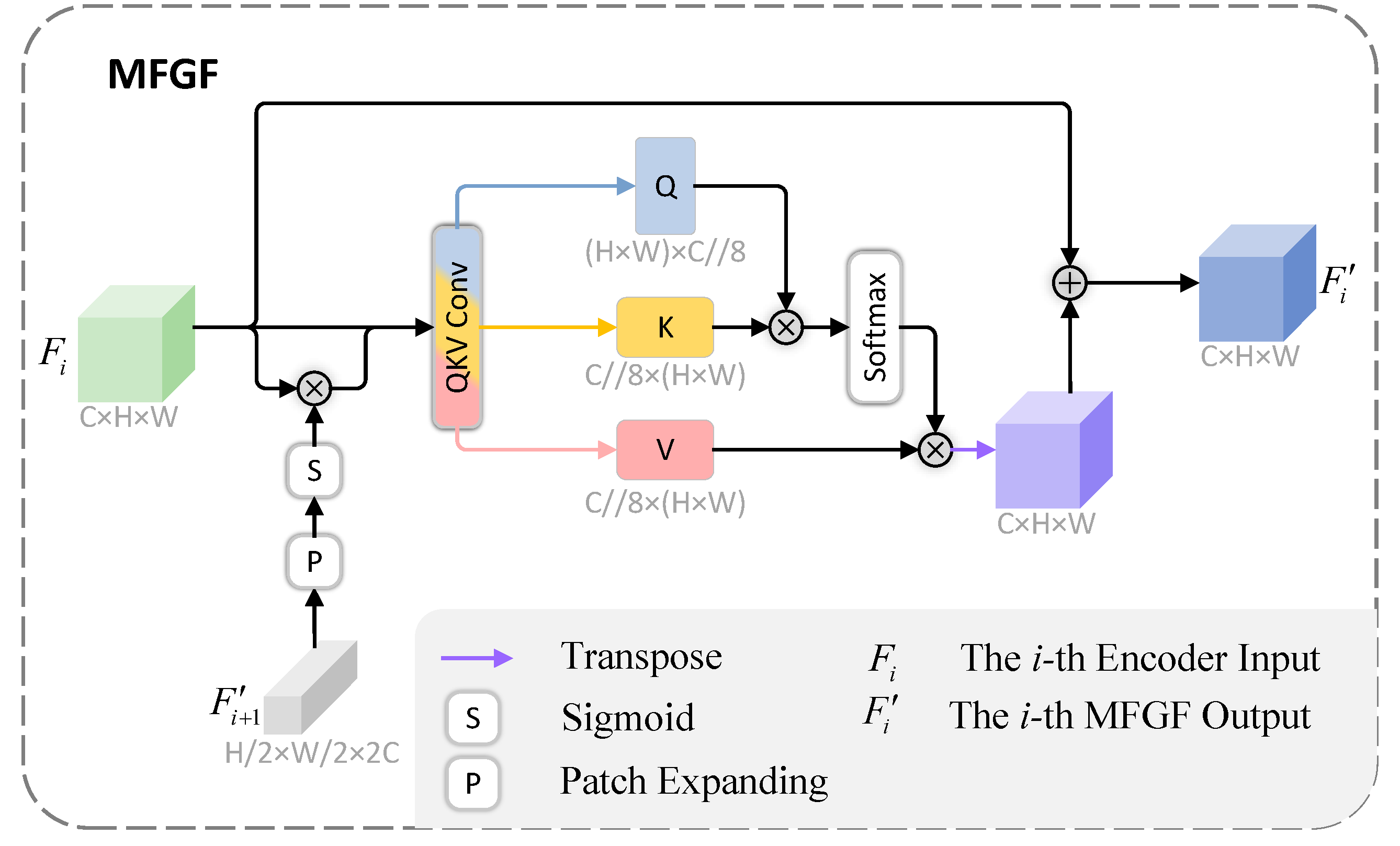

- A proposed plug-and-play Multi-scale Feature Guiding Fusion (MFGF) module is capable of leveraging deep features to conduct layer-by-layer fusion of shallow features. This process fortifies the information exchange across each scale, which augment the utilization efficiency of feature information. It bolsters the global modeling capabilities of VMMCD, and efficiently mitigates or resolves the issue of missed detection.

- To validate the efficacy of our proposed methodology, a comprehensive set of qualitative and quantitative experiments were carried out on three datasets: SYSU-CD, WHU-CD, and S2Looking. The results of these experiments indicated that VMMCD exhibited satisfactory performance and, in certain aspects, achieved state-of-the-art results.

2. Related Works

2.1. VMamba Model

2.2. Feature Fusion and Interaction

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overall Architecture

3.2. VMamba-Based Encoder and Decoder

3.3. Multi-Scale Feature Guiding Fusion (MFGF) Module

3.4. Loss Function

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. SYSU-CD

4.1.2. WHU-CD

4.1.3. S2Looking

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.2.1. Implementation Details

4.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

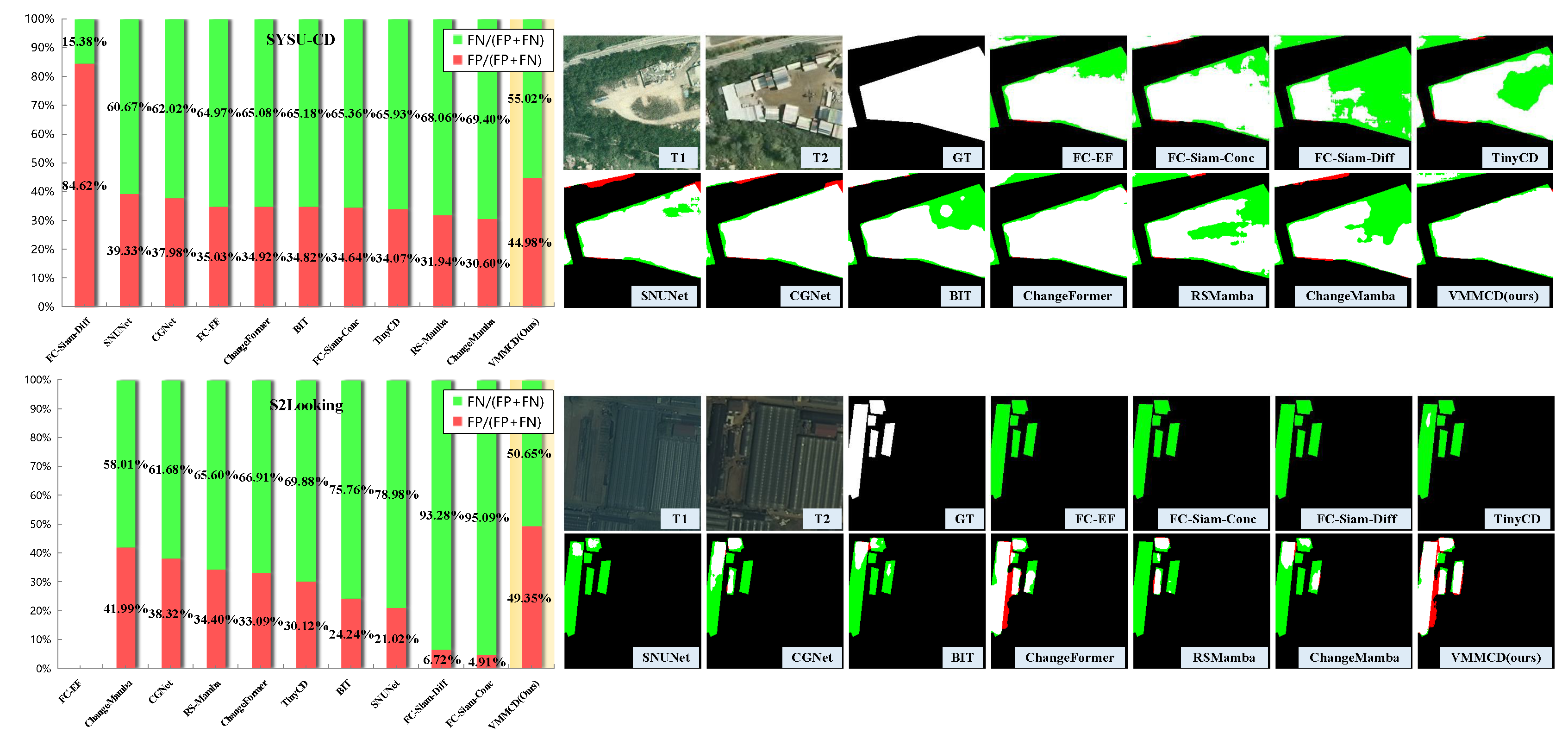

4.3. Comparison to State-of-the-Art (SOTA)

4.3.1. Quantitative results

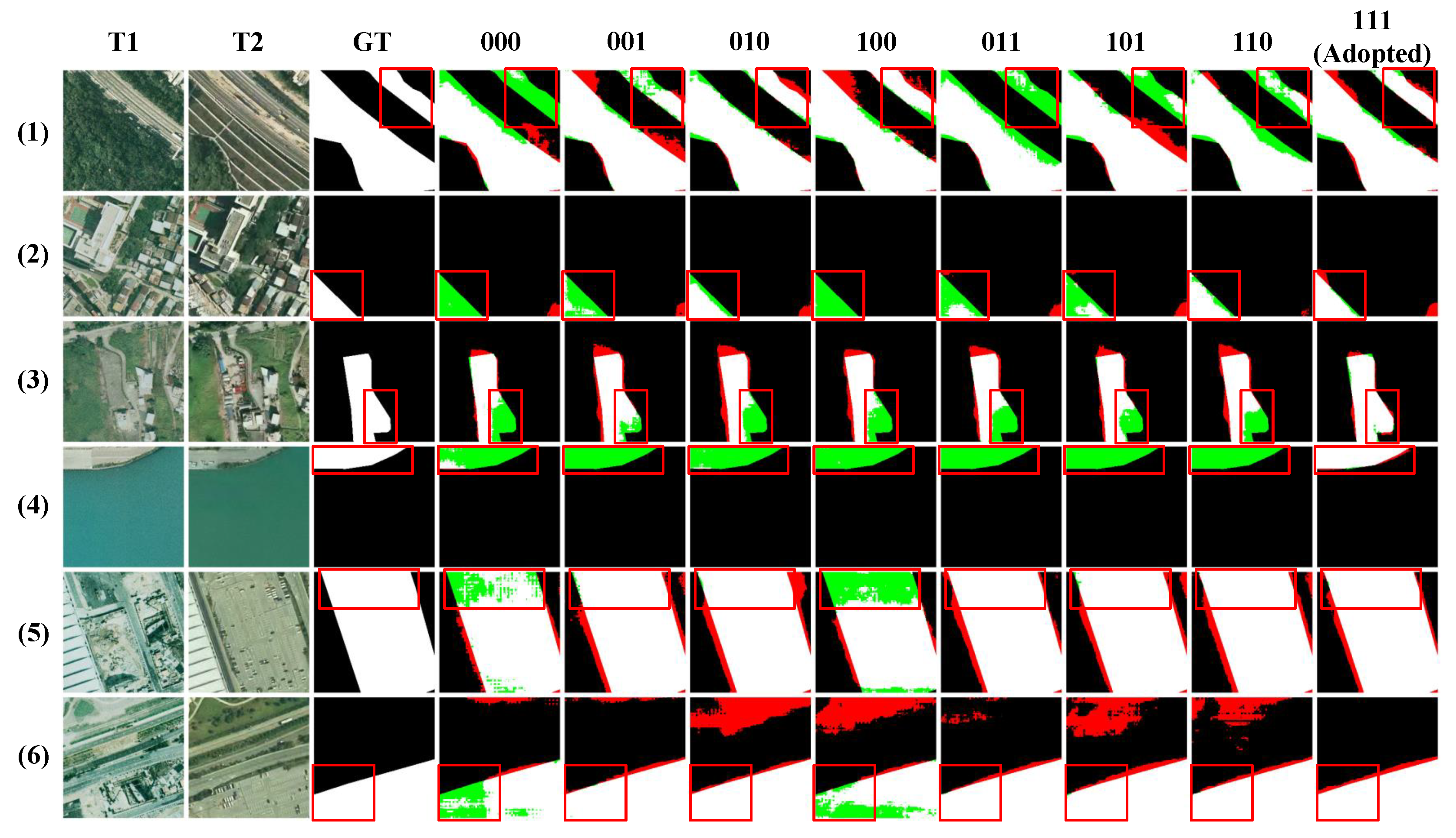

4.3.2. Qualitative Visualization Results

4.3.3. Model Efficiency

4.4. Ablation Study

- Backbone networks.

- Model magnitude.

- The number of MFGFs.

- The coefficient of the loss function.

4.4.1. Ablation on Backbone Networks

4.4.2. Ablation on Model Magnitude

4.4.3. Ablation on MFGFs

4.4.4. Ablation on the Coefficient of the Loss Function

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Desclée, B.; Bogaert, P.; Defourny, P. Forest change detection by statistical object-based method. Remote Sensing of Environment 2006, 102, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolorinos, J.; Ajami, N.K.; Rajagopal, R. Consumption Change Detection for Urban Planning: Monitoring and Segmenting Water Customers During Drought. Water Resources Research 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridd, M.K.; Liu, J. A Comparison of Four Algorithms for Change Detection in an Urban Environment. Remote Sensing of Environment 1998, 63, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, I.R.; Kaloop, M.R. Monitoring urban growth and land use change detection with GIS and remote sensing techniques in Daqahlia governorate Egypt. International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 2015, 4, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, A.F.; Kumar, L. Investigating the Use of Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques to Detect Land Use and Land Cover Change: A Review. Advances in Remote Sensing 2013, 2, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sublime, J.; Kalinicheva, E. Automatic Post-Disaster Damage Mapping Using Deep-Learning Techniques for Change Detection: Case Study of the Tohoku Tsunami. Remote Sensing 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Se, S.; Firoozfam, P.; Goldstein, N.; Wu, L.; Dutkiewicz, M.; Pace, P.; Naud, J.L.P. Automated UAV-based mapping for airborne reconnaissance and video exploitation. In Proceedings of the Airborne Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR) Systems and Applications VI; Henry, D.J., Ed. International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2009, Vol. 7307, p. 73070M. [CrossRef]

- D. Lu Corresponding author, P. Mausel, E.B.; Moran, E. Change detection techniques. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2004, 25, 2365–2401.

- Nielsen, A.A. The Regularized Iteratively Reweighted MAD Method for Change Detection in Multi- and Hyperspectral Data. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2007, 16, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, M.H.; A, D.C.; A, A.C.; B, H.W.; B, D.S. Change detection from remotely sensed images: From pixel-based to object-based approaches - ScienceDirect. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2013, 80, 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Daudt, R.C.; Saux, B.L.; Boulch, A. Fully Convolutional Siamese Networks for Change Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, M.; Yang, G.; Zhang, L. ESCNet: An End-to-End Superpixel-Enhanced Change Detection Network for Very-High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, PP, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Yang, G.; Zhang, H. Transition Is a Process: Pair-to-Video Change Detection Networks for Very High Resolution Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2023, 32, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yue, P.; Tapete, D.; Jiang, L.; Shangguan, B.; Huang, L.; Liu, G. A deeply supervised image fusion network for change detection in high resolution bi-temporal remote sensing images. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 166, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Wang, J.; Ning, H.; Wang, X.; Xue, D.; Wang, Q.; Nandi, A.K. Difference Enhancement and Spatial–Spectral Nonlocal Network for Change Detection in VHR Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codegoni, A.; Lombardi, G.; Ferrari, A. TINYCD: A (Not So) Deep Learning Model For Change Detection. 2022; arXiv:cs.CV/2207.13159. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Li, K.; Shao, J.; Li, Z. SNUNet-CD: A Densely Connected Siamese Network for Change Detection of VHR Images. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yuan, Z.; Peng, J.; Chen, L.; Huang, H.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. DASNet: Dual Attentive Fully Convolutional Siamese Networks for Change Detection in High-Resolution Satellite Images. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xu, G.; Chen, K.; Yan, M.; Sun, X. Triplet-Based Semantic Relation Learning for Aerial Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2019, 16, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, W. A Feature Difference Convolutional Neural Network-Based Change Detection Method. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 7232–7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Heess, N.; Graves, A.; kavukcuoglu, k. Recurrent Models of Visual Attention. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ghahramani, Z.; Welling, M.; Cortes, C.; Lawrence, N.; Weinberger, K., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2014, Vol. 27.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), September 2018.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale, 2021. arXiv:cs.CV/2010.11929.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, Vol. 30.

- Chen, H.; Shi, Z. A Spatial-Temporal Attention-Based Method and a New Dataset for Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hang, R.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q. DiFormer: A Difference Transformer Network for Remote Sensing Change Detection. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qi, Z.; Shi, Z. Remote Sensing Image Change Detection With Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xue, L.; Wang, X.; Li, G. ConvTransNet: A CNN–Transformer Network for Change Detection With Multiscale Global–Local Representations. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shi, Q.; Chai, Z.; Li, J. PA-Former: Learning Prior-Aware Transformer for Remote Sensing Building Change Detection. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Brock, A.; Berrada, L.; De, S. ConvNets Match Vision Transformers at Scale. ArXiv 2023, abs/2310.16764.

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces, 2024. arXiv:cs.LG/2312.00752.

- Gu, A.; Goel, K.; Ré, C. Efficiently Modeling Long Sequences with Structured State Spaces, 2022. arXiv:cs.LG/2111.00396.

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual State Space Model. ArXiv 2024, abs/2401.10166. arXiv:abs/2401.10166.

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model, 2024. arXiv:cs.CV/2401.09417.

- Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Ren, S.; Wei, G.; Mei, J.; Shao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yuille, A.; Xie, C. Mamba-R: Vision Mamba ALSO Needs Registers, 2024. arXiv:cs.CV/2405.14858.

- Ye, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. P-Mamba: Marrying Perona Malik Diffusion with Mamba for Efficient Pediatric Echocardiographic Left Ventricular Segmentation, 2024. arXiv:cs.CV/2402.08506.

- Patro, B.N.; Agneeswaran, V.S. SiMBA: Simplified Mamba-Based Architecture for Vision and Multivariate Time series, 2024. arXiv:cs.CV/2403.15360.

- Ruan, J.; Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation, 2024. arXiv:eess.IV/2402.02491.

- Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P.; Bai, L.; Ouyang, W. RS-Mamba for Large Remote Sensing Image Dense Prediction. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, J.; Han, C.; Xia, J.; Yokoya, N. ChangeMamba: Remote Sensing Change Detection With Spatiotemporal State Space Model. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Wu, C.; Guo, H.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Change Guiding Network: Incorporating Change Prior to Guide Change Detection in Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2023, 16, 8395–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Patel, V.M. A Transformer-Based Siamese Network for Change Detection. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; 2022; pp. 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. SCConv: Spatial and Channel Reconstruction Convolution for Feature Redundancy. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023; pp. 6153–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Kamata, S.I.; Wang, H.; Wong, M.S. Huiying.;Hou. Mamba-in-Mamba: Centralized Mamba-Cross-Scan in Tokenized Mamba Model for Hyperspectral Image Classification, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2405.12003].

- Qiao, Y.; Yu, Z.; Guo, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, M.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J. VL-Mamba: Exploring State Space Models for Multimodal Learning, 2024. arXiv:cs.CV/2403.13600.

- Fang, S.; Li, K.; Li, Z. Changer: Feature Interaction is What You Need for Change Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2023, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; RoyChowdhury, A.; Maji, S. Bilinear CNN Models for Fine-Grained Visual Recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Du, Z.; Shen, H. Spatiotemporal Enhancement and Interlevel Fusion Network for Remote Sensing Images Change Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, X.; Tan, K.; Mango, J.; Pan, C.; Zhang, D. Position-Aware Graph-CNN Fusion Network: An Integrated Approach Combining Geospatial Information and Graph Attention Network for Multiclass Change Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S.; Li, Y. SwinSUNet: Pure Transformer Network for Remote Sensing Image Change Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection, 2018. arXiv:cs.CV/1708.02002.

- Shi, Q.; Liu, M.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L. A Deeply Supervised Attention Metric-Based Network and an Open Aerial Image Dataset for Remote Sensing Change Detection. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wei, S.; Lu, M. Fully Convolutional Networks for Multisource Building Extraction From an Open Aerial and Satellite Imagery Data Set. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2019, 57, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Lu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wei, H.; Xie, D.; Yue, J.; Chen, R.; Lv, S.; Jiang, B. S2Looking: A Satellite Side-Looking Dataset for Building Change Detection. Remote Sensing 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization, 2019. arXiv:cs.LG/1711.05101.

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. CoRR 2014, abs/1409.1556.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2015, pp. 770–778.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. ArXiv 2019, abs/1905.11946.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 2021, pp. 9992–10002.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 2012, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Method | SYSU-CD[52] | WHU-CD[53] | S2Looking[54] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre. / Rec. / F1 / IoU | Pre. / Rec. / F1 / IoU | Pre. / Rec. / F1 / IoU | |||||||||||

| CNN-based | FC-EF[11] | 80.22 | 68.62 | 73.97 | 58.69 | 74.56 | 73.94 | 74.25 | 59.05 | - | - | - | - |

| FC-Siam-Conc[11] | 81.44 | 69.93 | 75.25 | 60.32 | 38.47 | 84.25 | 52.82 | 35.89 | 84.16 | 21.53 | 34.29 | 20.69 | |

| FC-Siam-Diff[11] | 40.54 | 78.95 | 53.57 | 36.58 | 40.54 | 78.95 | 53.57 | 36.58 | 80.70 | 23.14 | 35.97 | 21.93 | |

| TinyCD[16] | 85.84 | 75.80 | 80.51 | 67.38 | 89.62 | 88.44 | 89.03 | 80.22 | 72.47 | 53.15 | 61.32 | 44.22 | |

| SNUNet[17] | 83.31 | 76.39 | 79.70 | 66.25 | 80.79 | 87.03 | 83.80 | 72.11 | 75.49 | 45.05 | 56.43 | 39.30 | |

| CGNet[41] | 85.60 | 78.45 | 81.87 | 69.30 | 90.78 | 90.21 | 90.50 | 82.64 | 70.18 | 59.38 | 64.33 | 47.41 | |

| Transformer-based | BIT[27] | 83.22 | 72.60 | 77.55 | 63.33 | 84.62 | 88.00 | 86.28 | 75.87 | 75.35 | 49.44 | 59.71 | 42.56 |

| ChangeFormer[42] | 86.47 | 77.42 | 81.70 | 69.06 | 95.58 | 89.83 | 92.62 | 86.25 | 73.33 | 57.62 | 64.54 | 47.64 | |

| Mamba-based | RS-Mamba[39] | 85.38 | 73.27 | 78.86 | 65.10 | 93.70 | 91.08 | 92.37 | 85.83 | 71.49 | 56.80 | 63.30 | 46.31 |

| ChangeMamba[40]* | 88.79 | 77.74 | 82.89 | 70.79 | 91.92 | 92.36 | 94.03 | 88.73 | 68.59 | 61.25 | 64.71 | 47.84 | |

| VMMCD(ours) | 84.76 | 81.97 | 83.35 | 71.45 | 93.84 | 91.23 | 92.52 | 86.08 | 65.45 | 64.86 | 65.16 | 48.32 | |

| Type | Method | GFlops | Params | fps | SYSU-CD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M) | (pair/s) | F1 / IoU | ||||

| FC-EF[11] | 3.24 | 1.35 | 160.26 | 73.97 | 58.69 | |

| FC-Siam-Conc[11] | 4.99 | 1.55 | 119.75 | 53.57 | 36.58 | |

| FC-Siam-Diff[11] | 4.39 | 1.35 | 122.77 | 75.25 | 60.32 | |

| TinyCD[16] | 1.45 | 0.29 | 85.47 | 80.51 | 67.38 | |

| SNUNet[17] | 11.73 | 3.01 | 67.46 | 79.70 | 66.25 | |

| CGNet[41] | 87.55 | 38.98 | 74.70 | 81.87 | 69.30 | |

| BIT[27] | 26.00 | 11.33 | 62.82 | 77.55 | 63.33 | |

| ChangeFormer[42] | 202.79 | 41.03 | 58.58 | 81.70 | 69.06 | |

| RS-Mamba[39] | 18.33 | 42.30 | 22.58 | 78.86 | 65.10 | |

| ChangeMamba[40] | 28.70 | 49.94 | 16.89 | 82.89 | 70.79 | |

| VMMCD(ours) | 4.51 | 4.93 | 73.05 | 83.35 | 71.45 | |

| Backbone | GFlops | Params | SYSU-CD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M) | F1 / IoU | |||

| VGG16[56] | 50.41 | 18.62 | 75.92 | 61.19 |

| ResNet18[57] | 5.49 | 13.21 | 78.50 | 64.61 |

| EfficientNet-B4[58] | 2.71 | 1.44 | 81.57 | 68.87 |

| Swin-small[59] | 15.27 | 24.61 | 68.85 | 52.50 |

| VMamba-small(Ours) | 4.51 | 4.93 | 83.35 | 71.45 |

| Model | Dims | SYSU-CD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 / IoU | |||

| VMMCD-S4 | OOM | ||

| 80.42 | 67.25 | ||

| 80.23 | 66.98 | ||

| VMMCD-S3 | 80.49 | 67.36 | |

| (Ours) | 81.12 | 68.24 | |

| 80.25 | 67.02 | ||

| Model | MFGF | SYSU-CD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | F1 / IoU | ||

| VMMCD-S4 | × | × | × | × | 81.88 | 69.33 |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 82.63 | 70.41 | |

| VMMCD-S3 | × | × | × | - | 82.36 | 70.01 |

| × | × | √ | - | 82.98 | 70.90 | |

| × | √ | × | - | 82.70 | 70.50 | |

| √ | × | × | - | 82.83 | 70.69 | |

| × | √ | √ | - | 83.00 | 70.94 | |

| √ | × | √ | - | 82.99 | 70.92 | |

| √ | √ | × | - | 83.13 | 71.13 | |

| √ | √ | √ | - | 83.35 | 71.45 | |

| SYSU-CD | WHU-CD | S2Looking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 / IoU | F1 / IoU | F1 / IoU | ||||

| 0 | 83.34 | 71.44 | 92.45 | 85.97 | 64.83 | 47.97 |

| 0.1 | 83.30 | 71.38 | 92.47 | 86.00 | 65.18 | 48.35 |

| 0.2 | 83.35 | 71.45 | 92.52 | 86.08 | 65.16 | 48.32 |

| 0.3 | 83.26 | 71.32 | 92.50 | 86.04 | 65.07 | 48.22 |

| 0.5 | 83.25 | 71.30 | 92.50 | 86.05 | 64.90 | 48.03 |

| 1 | 83.23 | 71.28 | 92.59 | 86.20 | 65.21 | 48.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).