1. Introduction

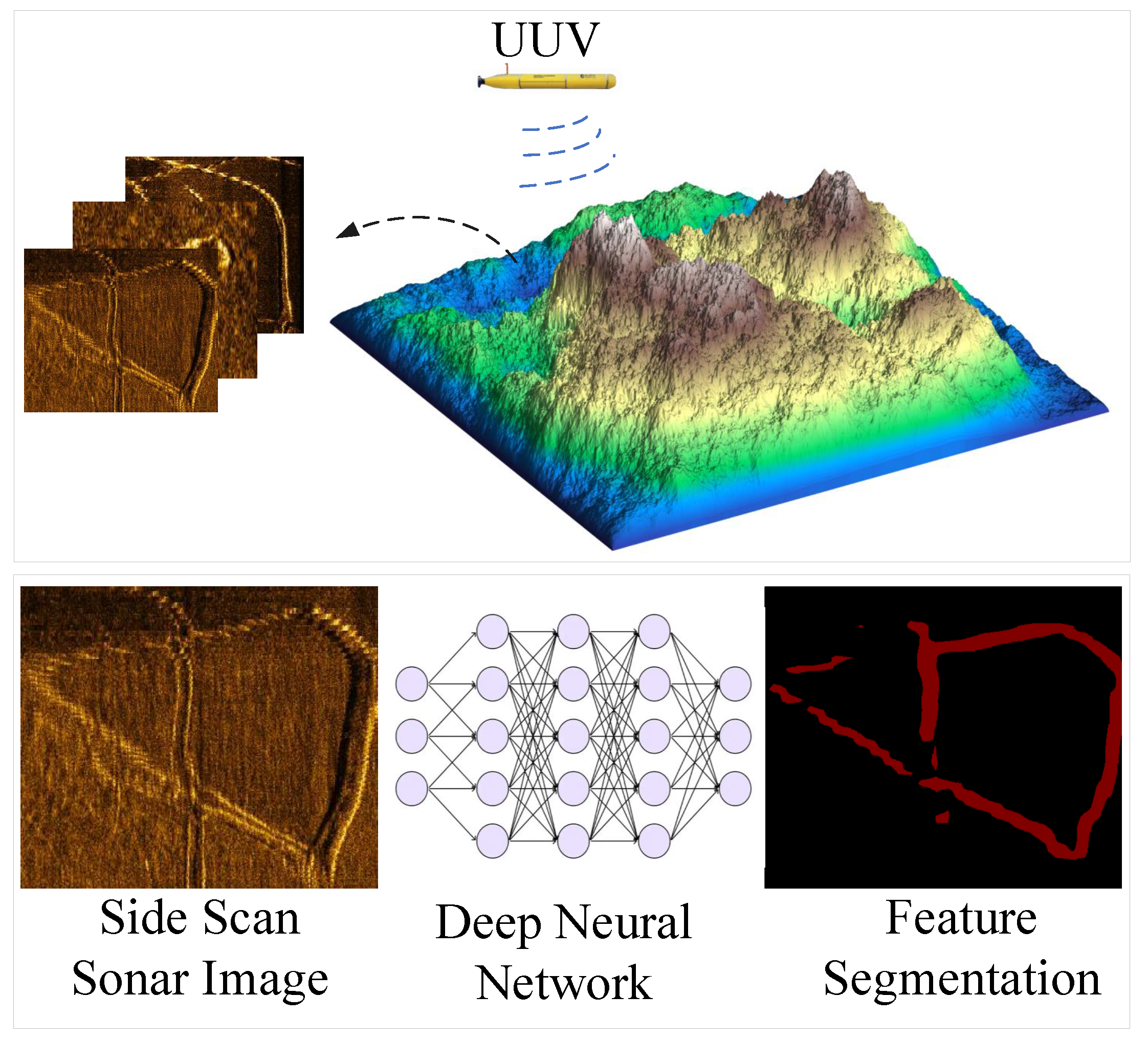

Underwater target detection and segmentation in SSS imagery are critical for marine exploration, wreck recovery, and pipeline inspection. However, SSS data exhibit intrinsic challenges such as speckle noise, geometric distortions, and low signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs) due to acoustic scattering and seabed heterogeneity [

1]. Traditional methods rely on handcrafted features (e.g., texture descriptors [

2] or SVM classifiers [

3]), but their performance degrades under complex underwater conditions. Recent advances in deep learning have improved accuracy, yet three critical gaps persist: (1) limited adaptability to SSS-specific noise patterns, (2) inefficient multi-scale feature fusion for distorted targets, (3) excessive computational costs.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have dominated SSS target detection and segmentation. U-Net variants [

4] achieved pixel-level segmentation of seabed textures by leveraging skip connections [

5], while Mask R-CNN [

6] enabled joint detection and segmentation through region-based optimization [

7]. Topological Data Analysis (TDA) [

8] was introduced into sonar analysis for the first time to extract the persistent homology features of sonar images and enhance the interpretability of CNN decisions. But the computational complexity is high and the efficiency is optimized. However, standard convolutions struggle to model SSS noise distributions, leading to false positives in low-SNR regions [

9]. To enhance robustness, attention mechanisms like Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [

10] were integrated into FPNs [

11], but their fixed-weight filters limit adaptability to dynamic acoustic conditions [

12]. Sparse Attention U-Net [

13] focuses on the target area through the dynamic sparse attention mechanism to reduce the interference of background noise. It provides a new idea for weak supervised sonar segmentation, but the generalization ability is limited by the data quality.

In image segmentation and detection, Zhang et al. [

14] proposed an enhanced model integrating Ghost modules and a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN). This model improves segmentation accuracy for small leaves in complex backgrounds through multi-scale feature fusion, addressing the limitations of traditional methods in recognizing overlapping leaves and low-contrast regions. Wang et al. [

15] aimed at the challenges of low contrast and blurred boundaries in CT images of kidney tumors, introduced a lightweight network design and cross-modal feature fusion strategy, optimizing the model’s inference efficiency and segmentation accuracy in medical imaging. Li et al. [

16] developed a lightweight instance segmentation algorithm tailored for chip pad detection. By optimizing the model architecture for this specific task, the algorithm reduces false detection rates and enhances detection precision. Zheng et al. [

17] enhanced the model’s ability to distinguish blurred targets and complex backgrounds in underwater sonar images by integrating spatial-channel attention mechanisms. Weng et al. [

18] proposed an improved Spatial-Channel Reconstruction (SCR) module that integrates spatial features with channel attention mechanisms to effectively suppress noise interference in underwater sonar images and enhance the detection capability for blurred targets. Chen et al. [

19] introduced the AquaYOLO framework based on YOLOv8. By leveraging multi-scale feature fusion and adaptive feature selection mechanisms, the framework significantly improves detection robustness in complex underwater scenes. Current research focuses on multi-task architecture optimization, noise robustness enhancement, and edge computing compatibility. Existing methods, such as attention mechanisms and multi-scale fusion, often rely on fixed-weight filters or static architectures, limiting adaptability to dynamic noise patterns and geometric distortions in SSS imagery, while sacrificing parameter efficiency.

Real-time processing on UUVs demands model compression. MobileNet [

20] and EfficientDet [

21] reduced parameters via depthwise convolutions, yet sacrificed segmentation precision [

22]. YOLO-based approaches [

23] balanced speed and accuracy but lacked dedicated modules for SSS geometric distortions [

24]. Yolov4-Tiny [

25] introduces channel pruning and 8-bit quantization to achieve real-time detection of 45 FPS. The feasibility of model compression in UUV deployment is verified, but the accuracy and speed need to be balanced. Dynamic Neural Architecture (DNA-UUV) [

26] adjusts the depth and width of the model in real-time based on hardware resources, reducing energy consumption by 40%. It provides flexible computing solutions for heterogeneous UUV platforms, but needs to optimize the switching mechanism. The two-stage model [

27] achieves end-to-end optimization of small sample sonar segmentation for the first time. Firstly, the target shadow feature is used to locate the initial area, and then combined with the level set algorithm for fine segmentation, to transfer optical image data and enhance small sample performance. But the computational efficiency needs to be improved. The lightweight network U-Net combined with heterogeneous filters [

28] achieves 25 FPS real-time segmentation on an FPGA embedded platform, with energy consumption < 5W, providing a low-power solution for UUV deployment. However, in strong noise environments, the segmentation mIoU decreases by about 10%, and it is necessary to enhance the generalization ability in complex environments.

Knowledge distillation [

29] and quantization [

30] further optimized efficiency, but most methods ignored the interplay between noise suppression and multi-task learning. Spline-based networks [

31] and Kolmogorov-Arnold representations [

32] recently gained traction for interpretable feature learning. For example, B-spline CNNs [

33] achieved noise-adaptive filtering in medical imaging, while deformable kernels [

34] improved geometric invariance. However, these works focused on optical or synthetic aperture sonar (SAS) data [

35], leaving SSS-specific adaptations unexplored. In addition, the MAML framework based on meta [

36] learning only requires 10 annotated images to adapt to new audio devices, with a mIoU of 75.2%. It solves the problem of small sample sonar segmentation, but requires strengthening the domain adaptation module. Meanwhile, the generalization ability of cross device noise distribution is unstable (

mIoU fluctuation).

To bridge these gaps, we propose CKAN-YOLOv8, a lightweight multi-task network integrating KANConv into the YOLOv8 framework. Our key innovations include:

KANConv Blocks: replacing standard convolutions with learnable B-spline activations to dynamically suppress SSS noise while preserving edge details;

KANConv-PAN: A deformable feature pyramid network using spline-parameterized kernels to correct geometric distortions and fuse multi-scale targets;

Dual-Task Head: combining CIoU Loss for detection and segmentation with Dice Loss to refine boundary-sensitive segmentation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work of sonar data and YOLOv8,

Section 3 details the architecture of CKAN-YOLOv8,

Section 4 presents experimental results, and

Section 5 discusses conclution.

3. Proposed Method

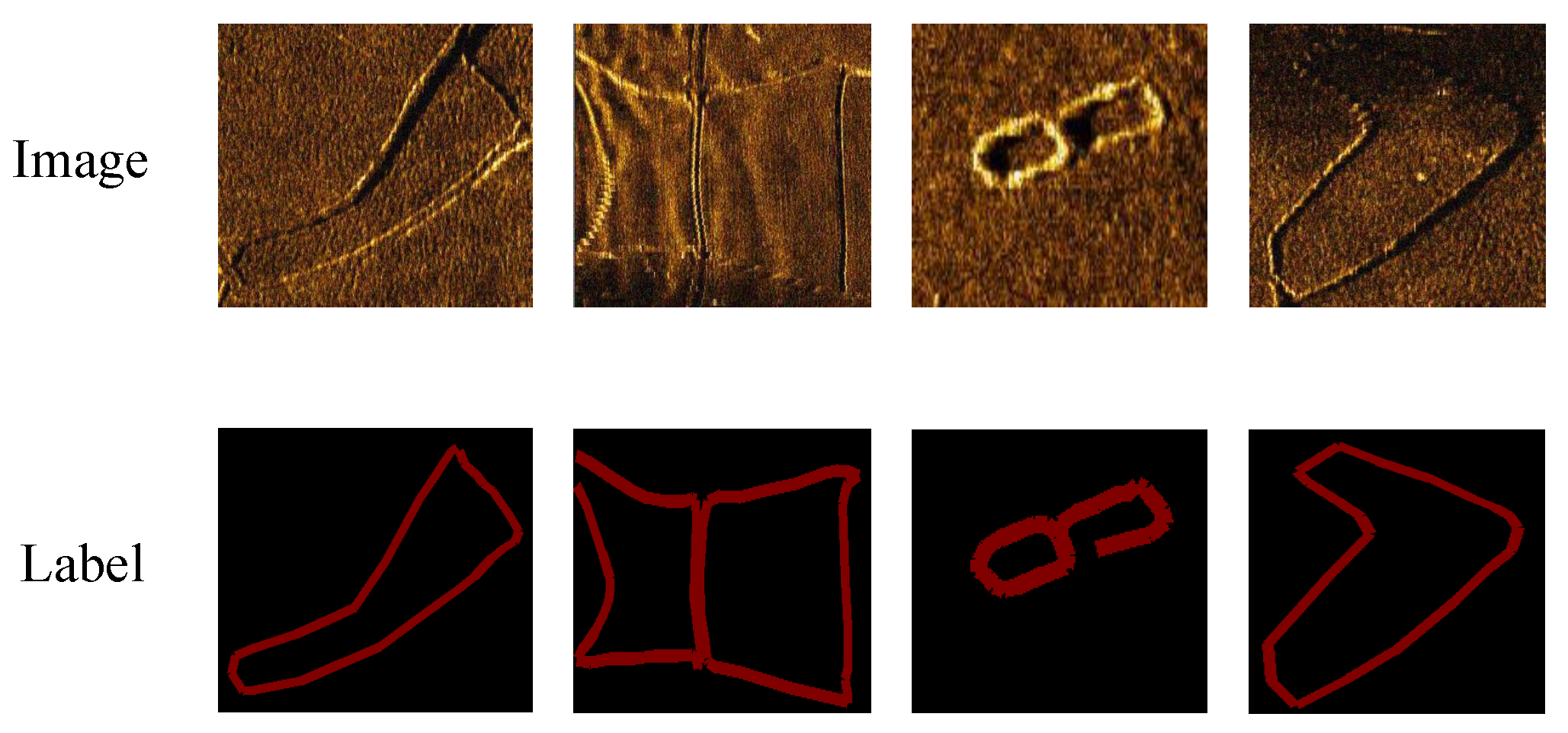

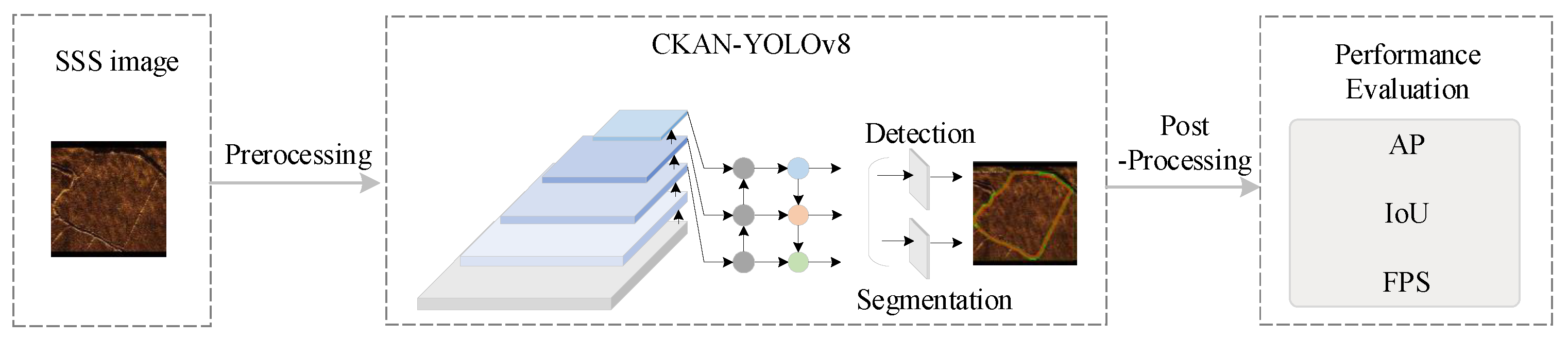

The procedure of this study is shown in

Figure 3. First, SSS images were processed to prepare the input data. Second, the CKAN-YOLOv8 model, which includes C2f-KANConv modules, KANConv-PANet, and a cascade loss function, was used for processing the SSS images. This step aims to enhance the model’s ability to segment and detect. Finally, the model’s predictions were validated to ensure accuracy and reliability.

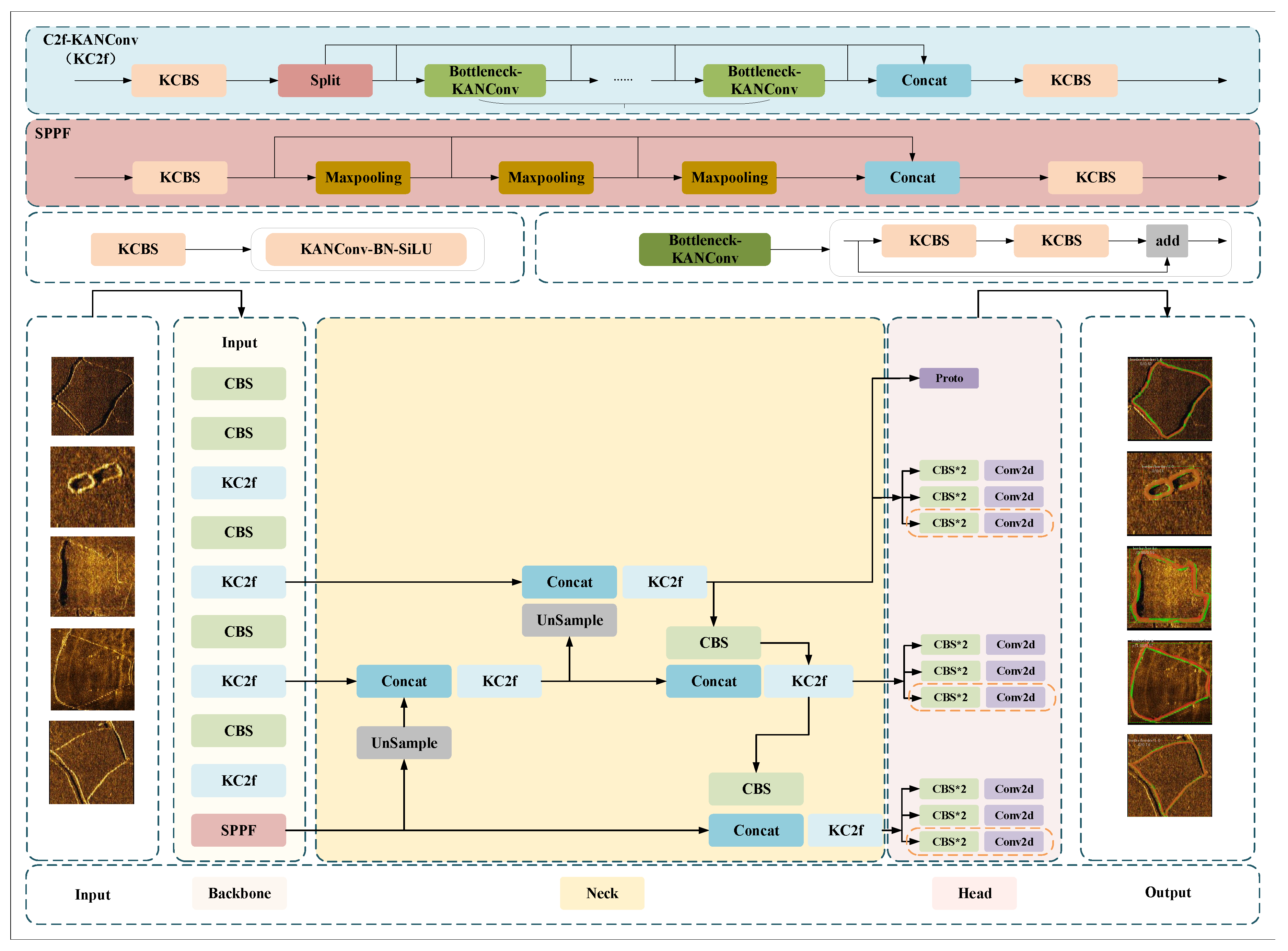

3.1. Structure of the CKAN-YOLOv8 Model

YOLOv8 represents the latest advancement in the YOLO series, developed by Ultralytics as an upgraded successor to YOLOv5. This object detection framework is divided into four core components:

Input Preprocessing: Utilizes noise-based augmentation, adaptive scaling, and grayscale padding to optimize raw image data for diverse detection scenarios;

Backbone Architecture: Incorporates convolutional layers, C2f modules, and spatial pyramid pooling (SPPF) blocks for hierarchical feature extraction through convolutional operations and multi-scale pooling;

Neck Network: Leverages a modified path aggregation network (PANet) topology to integrate multi-level features via bidirectional sampling (upsampling/downsampling) and concatenation operations;

Detection: Employs decoupled prediction heads to independently handle classification tasks, bounding box regression.

The architecture implements a task-driven positive sample matching strategy, dynamically weighting classification confidence, localization accuracy during anchor assignment. For loss optimization, it combines:

Classification: Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) for object/non-object differentiation;

Localization: Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) for probability distribution-aware regression;

Bounding Box Refinement: CIoU metric to address aspect ratio discrepancies.

Enhanced by its modular design and adaptive training protocols, YOLOv8 achieves state-of-the-art performance in real-time detection and segmentation while maintaining computational efficiency across varied environmental conditions. Building upon this architecture, a mask branch are integrated into the detection head with corresponding loss function modifications that incorporate Dice loss, while utilizing the P3 layer (the highest-resolution feature map) extracted from the feature pyramid network as input to the Protonet, whose output prototypes serve as primitive mask templates for network predictions; the prediction head is enhanced to simultaneously generate bounding box coordinates, class probabilities, and mask coefficients that dynamically weight the prototypes, with post-NMS processing combining these coefficients and primitive masks through matrix multiplication to synthesize instance-specific masks, followed by coordinate-aligned crop operations based on predicted bounding boxes and threshold-based binarization to produce final segmentation results.

Figure 4 shows the structure of CKAN-YOLOv8.

3.2. KAN Convolutions

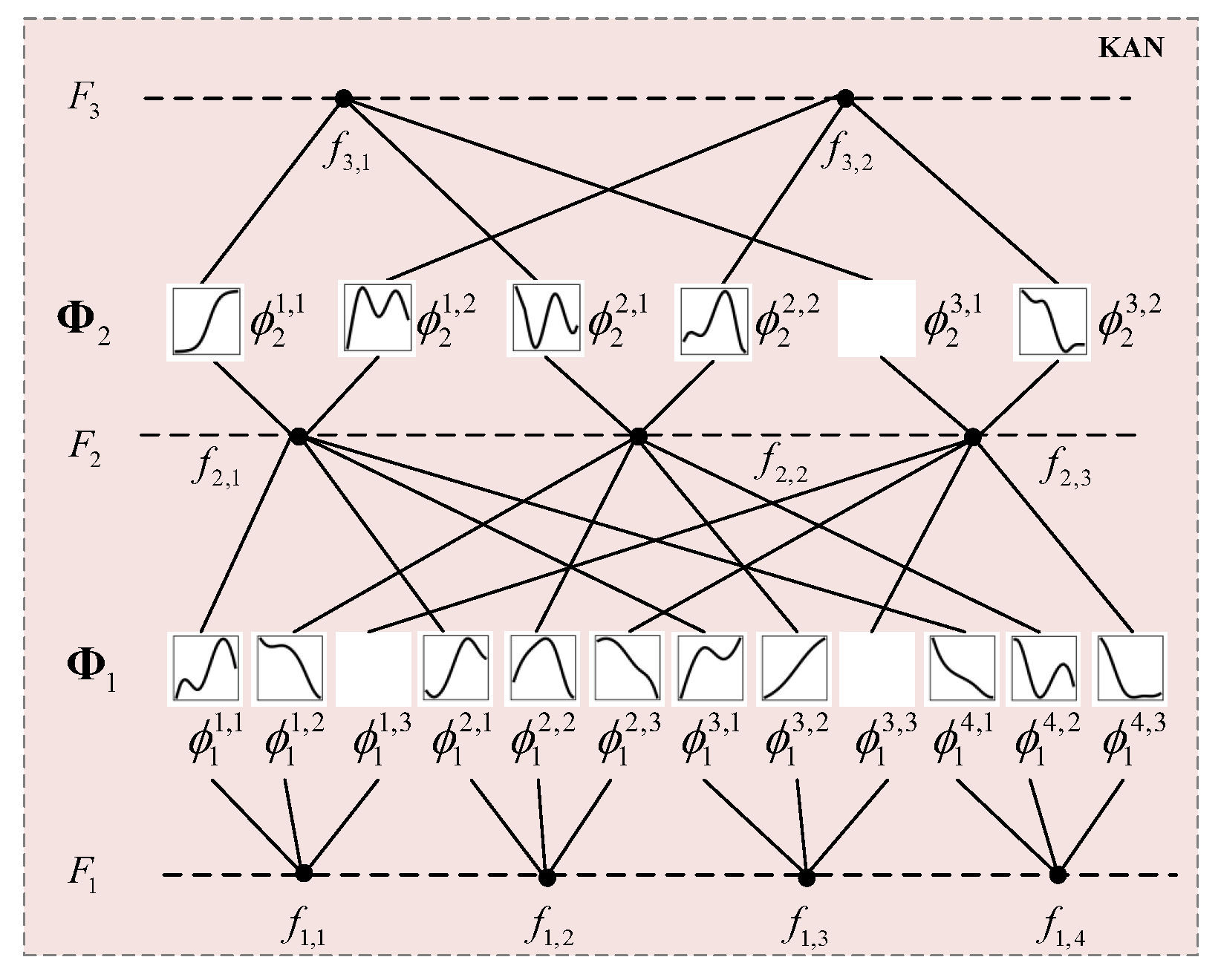

Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) [

37] are a novel deep learning architecture inspired by the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem, which posits that any multivariate continuous function can be decomposed into a finite superposition of univariate functions. Distinguished from traditional multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), KANs place learnable activation functions on network edges (weights), typically parameterized via B-splines, enabling adaptive nonlinear transformations. This structural innovation enhances their capability in modeling complex patterns, demonstrating superior performance in time-series analysis, graph-structured data processing, and convolutional operations.

Figure 5 shows the structure of KAN.

Its mathematical form is as follows:

In the mathematical formulation of KAN,

denotes the

j-th dimension of the input vector,

represents the learnable univariate function applied to the

j-th input along the

i-th computational path, and

constitutes the learnable univariate function at the output layer that synthesizes intermediate results into final predictions. By stacking multiple KAN layers (as Equation 8), deep networks can be constructed through hierarchical composition of these adaptive nonlinear transformations, where KAN’s divide-and-conquer strategy decomposes high-dimensional functions into combinations of low-dimensional univariate function components, thereby circumventing the gradient vanishing issues inherent in traditional multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) caused by the curse of dimensionality while maintaining both parametric efficiency and interpretability through its spline-based function approximation framework.

where

is the function matrix of the

l-th layer, and each element is a learnable unary activation function.

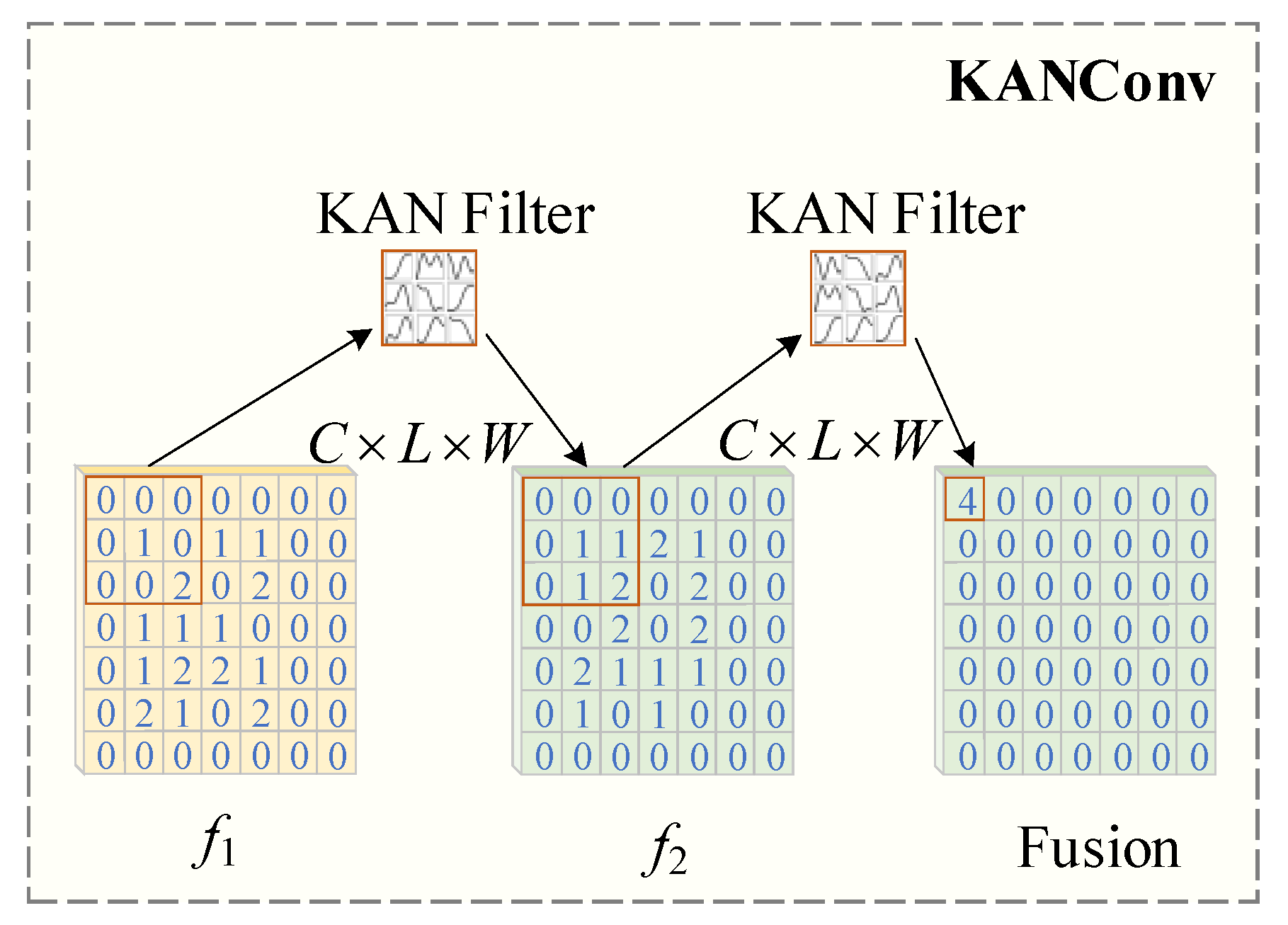

KAN Convolutions (KANConv) integrates the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem into convolutional neural networks by replacing standard convolution with learnable nonlinear operations. Unlike traditional convolutional layers that combine linear convolution with fixed nonlinear activations (e.g., ReLU) for structured data feature extraction, KANConv employs spline-based learnable nonlinear activations to enhance expressive power. Its advantages in noise suppression, multi-scale modeling, and computational efficiency make it particularly optimized for underwater target detection and segmentation tasks.

Figure 6 shows the structure of KANConv.

The mathematical expression of KANConv is described as follows:

where

is Combination of learnable nonlinear basis functions for the

c-th input channel and convolution kernel

position. All basis functions can be dynamically adjusted by training parameters to replace the linear convolution kernel weight of traditional CNN. Moreover, the coefficients of the basis function are optimized by back propagation to make the model adaptive to the data distribution. Among them, the training gradient of univariate function is more stable, which can alleviate the gradient disappearance problem of traditional CNN deep network.

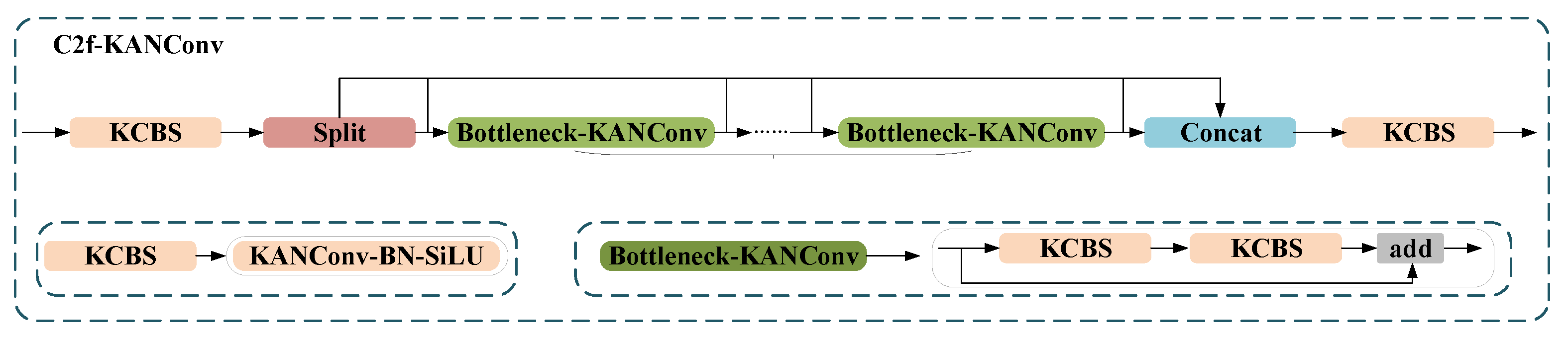

3.3. Cross Stage Partial Fusion with 2 KAN Convolutions

The traditional Cross Stage Partial (CSP) module separates feature streams and concatenates multi-branch outputs, which introduces channel dimension expansion and increased computational overhead15. To address the redundant computation and gradient fragmentation in conventional CSP modules, YOLOv8 introduces the C2f module [

38]. This enhanced architecture optimizes cross-stage feature interaction mechanisms and incorporates lightweight branch designs, achieving a significant improvement in the accuracy-speed balance for underwater target detection.

The core architecture of C2f comprises dual-convolution lightweight branches and a cross-stage gradient enhancement mechanism. The dual-convolution lightweight branch compresses the multi-branch convolutions in traditional CSP modules into two parallel lightweight branches. These branches then perform

convolution for channel reduction and

depthwise separable convolutions for spatial feature extraction. Its mathematical expression is as follows:

The cross-stage gradient enhancement mechanism introduces residual shortcut connections that add the original input to the outputs of the dual branches. This design mitigates gradient vanishing, with the mathematical formulation expressed as:

Thereby enhancing the integration continuity between shallow-layer texture features and deep-layer semantic representations.

KANConv enhances model adaptability to complex features (e.g., edges and textures of underwater targets) by dynamically adjusting convolutional kernel weights through learnable nonlinear activation functions, such as the per-pixel nonlinear operations. Compared to traditional CNNs, it achieves higher accuracy with fewer parameters, which is critical for real-time detection models like YOLO to improve performance without sacrificing inference speed. In the C2f module, which fuses multi-scale features via a dual-branch structure, replacing convolutions with KANConv strengthens the continuity of fusion between shallow-layer textures and deep-layer semantics through its nonlinear activation mechanism, reducing feature loss. Traditional CNN linear kernels struggle to fully model complex nonlinear relationships, while KANConv significantly improves feature representation capability via adaptive nonlinear transformations.

Figure 7 shows the structure of C2f-KANConv (KC2f). As illustrated in the figure, the original CBS (Conv-BatchNorm-SiLU) module, composed of a convolutional layer, batch normalization, and an activation function, has been redesigned into KCBS (KANConv-BatchNorm-SiLU) by replacing the traditional

convolution with KANConv while retaining the BN layer for training stability, ensuring that the input/output channel dimensions, stride, and padding remain consistent with the original CBS to prevent feature map size alterations.

The original Bottleneck structure, which consisted of two CBS modules and a residual connection, has been modified such that its main path now incorporates two sequentially connected KCBS modules for enhanced deep feature extraction. Furthermore, the original C2f module, which employs a Split-Concat architecture to fuse multi-scale features, retains the dimensionality-reduction convolution ( CBS) to avoid information loss, replaces the original Bottleneck with Bottleneck_KANConv while maintaining the stacking quantity, and utilizes KCBS instead of the original CBS for channel fusion, thereby achieving adaptive nonlinear feature integration while preserving structural compatibility.

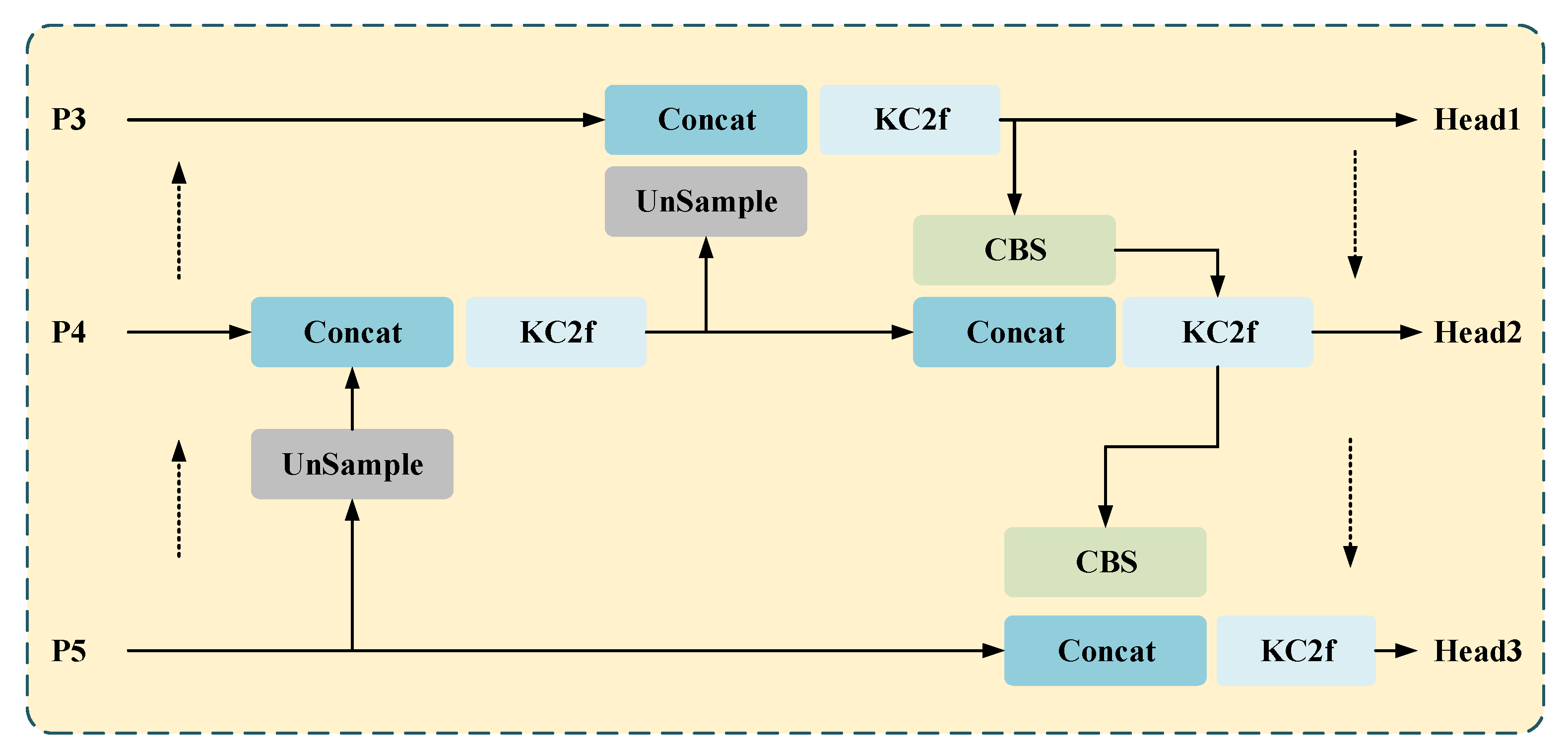

3.4. KANConv-PANet

The conventional CSB module in PANet relies on fixed convolutional kernel parameters, making it difficult to dynamically adjust response intensity to multi-scale targets. In scenarios with significant geometric distortions like sonar imagery, fixed kernels fail to adaptively fuse cross-resolution features, leading to degraded small object detection accuracy. Meanwhile, the linear superposition nature of traditional convolutions struggles to capture complex nonlinear feature relationships, while PANet’s multi-layer feature fusion heavily depends on nonlinear representation capabilities. KANConv addresses these limitations through learnable edge-weight functions that implement higher-order nonlinear mappings, enhancing cross-layer feature interaction effectiveness. Though CSP modules reduce parameter redundancy via channel splitting, their parallel branches still employ duplicated fixed kernels, resulting in suboptimal parameter utilization. During PANet’s upsampling phase, concatenating multi-scale feature maps with traditional dense parameter matrices causes high GPU memory consumption, creating bandwidth bottlenecks on embedded hardware. KANConv’s sparse-storage B-spline basis functions achieve memory footprint reduction, alleviating resource constraints during real-time inference while maintaining spatial adaptation through trainable activation curvature parameters.

Figure 8 shows the structure of KANConv-PAN, and KC2f in the structure is equivalent to C2f-KANConv. KANConv replaces the fixed kernel parameters of traditional convolution with B-spline activation functions, enabling dynamic adjustment of activation function shapes based on input features. This characteristic proves particularly critical in PANet’s multi-scale feature fusion, adaptively handling geometric distortions and scale variations in sonar imagery to enhance cross-resolution feature alignment. When fusing high-level semantic features (small target detection) and low-level detail features (boundary localization), KANConv’s differentiable B-spline basis functions exhibit heightened sensitivity to local texture variations compared to conventional convolutions. Additionally, KANConv employs sparse matrix storage for its B-spline basis functions, substantially reducing memory footprint versus dense parameter matrices in traditional convolutions, a feature that significantly alleviates GPU memory pressure during feature map concatenation in PANet’s upsampling stages.

The replacement of the CSB module in YOLOv8’s PAN-neck with KANConv achieves a balance between accuracy and speed through dynamic nonlinear modeling, parameter efficiency optimization, noise robustness enhancement, multi-scale object scenarios such as underwater sonar imaging and medical diagnostics. This method introduces a novel paradigm for lightweight real-time detection systems by leveraging B-spline-based adaptive kernels to resolve acoustic scattering artifacts and tissue boundary ambiguities, while maintaining computational frugality through sparse tensor decomposition in feature fusion pathways.

3.5. Loss Function

In sonar image classification, YOLOv8’s Decoupled Head offers the advantage of improved convergence speed by assigning prediction cells through IOU calculations between feature map cells and ground truth. However, the optimal cells for classification and regression often diverge, leading to misalignment between classification and regression tasks. To address this, YOLOv8 employs TAL (Task Alignment Learning) [

39], a task-aligned assignment technique for positive/negative sample allocation. It integrates DFL with CIoU Loss (as shown in Equation 10-14) as the regression branch’s loss function, while adopting BCE (as shown in Equation 16) for classification loss. This combination enhances alignment consistency between classification and regression tasks.

Drawing on the segmentation design of YOLACT [

40], this approach generates instance masks by parallel prediction of prototype masks for the current image and mask coefficients for each bounding box instance, followed by a linear combination of prototypes and coefficients. This eliminates the need for traditional two-stage RoIPool operations, preserving high output resolution and improving segmentation accuracy. For sonar image tasks, the segmentation head mirrors the detection structure, with extended branches at the Head layer: feature maps at three scales generate predictions for boxes, classifications, and mask coefficients, while Prototype Mask feature maps of equal size are generated on the largest-scale feature maps to serve as the native segmentation foundation. In segmentation tasks, Dice Loss is used for region overlap optimization:

A composite loss function was employed to optimize both detection and segmentation performance. The final total loss is as follows:

This loss function design comprehensively enhances model performance by balancing the importance of each component through weighting coefficients , combining accurate regression of detection boxes, distribution optimization for localization, classification accuracy, and segmentation boundary continuity. Ultimately, the multi-task joint optimization, enhanced noise robustness, and improved gradient stability significantly boost the network’s capability in sonar image detection and segmentation tasks.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

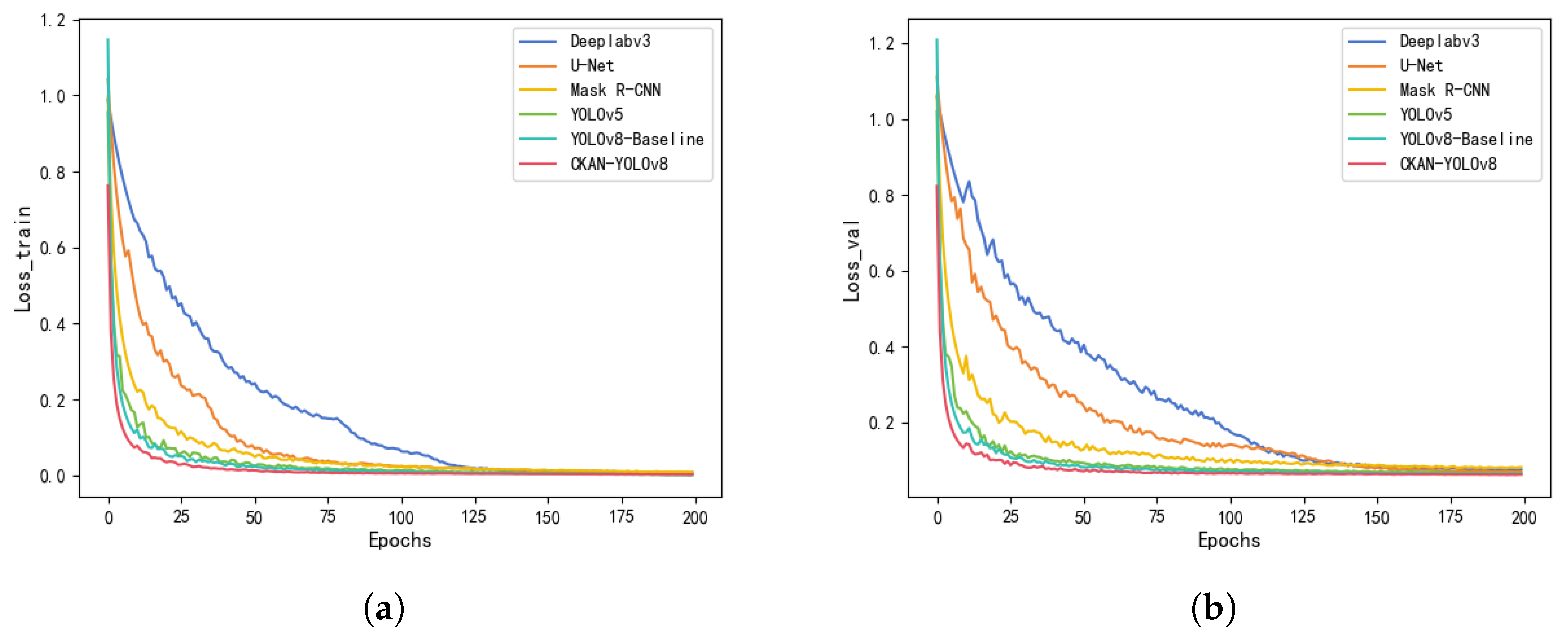

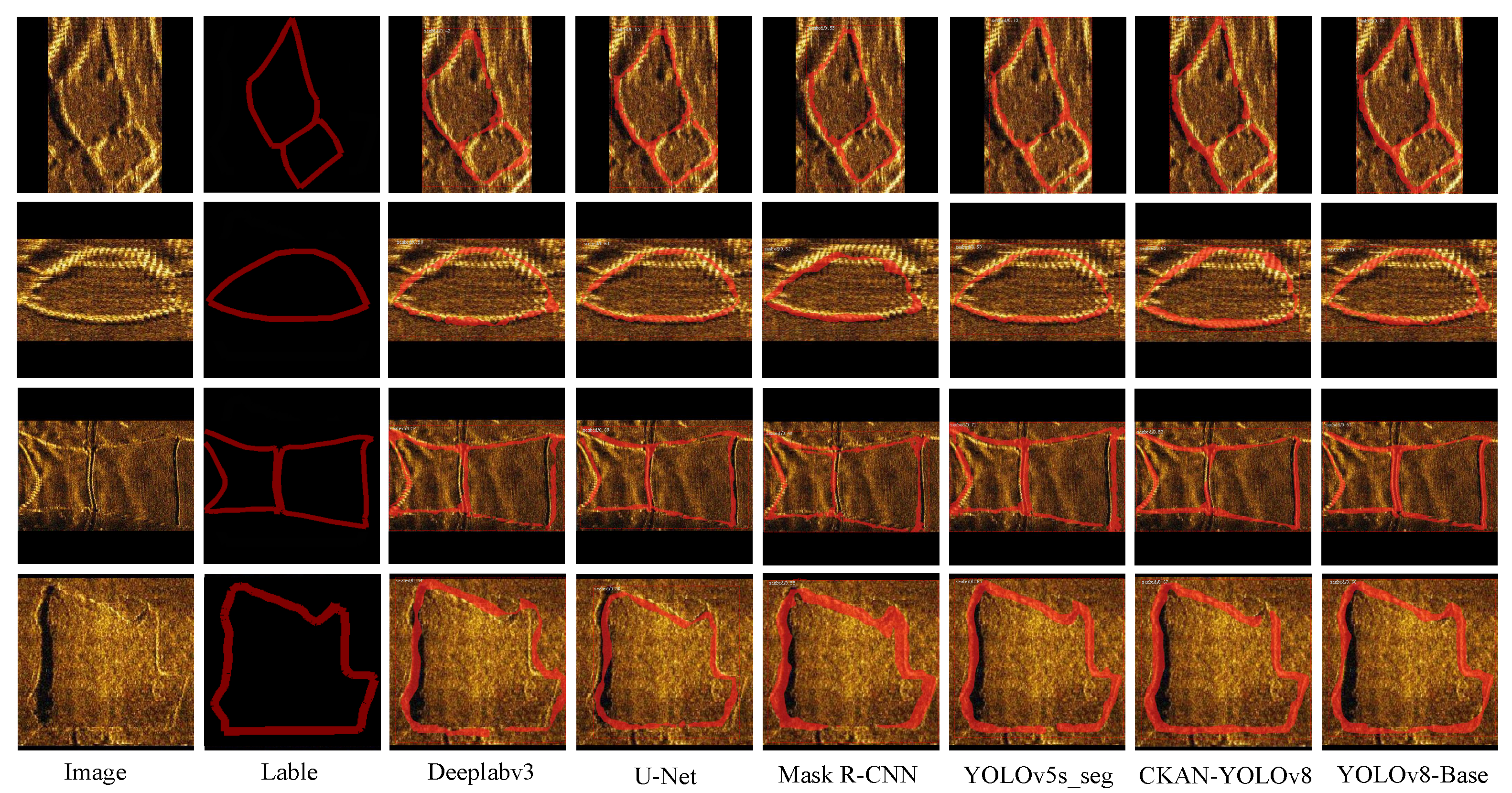

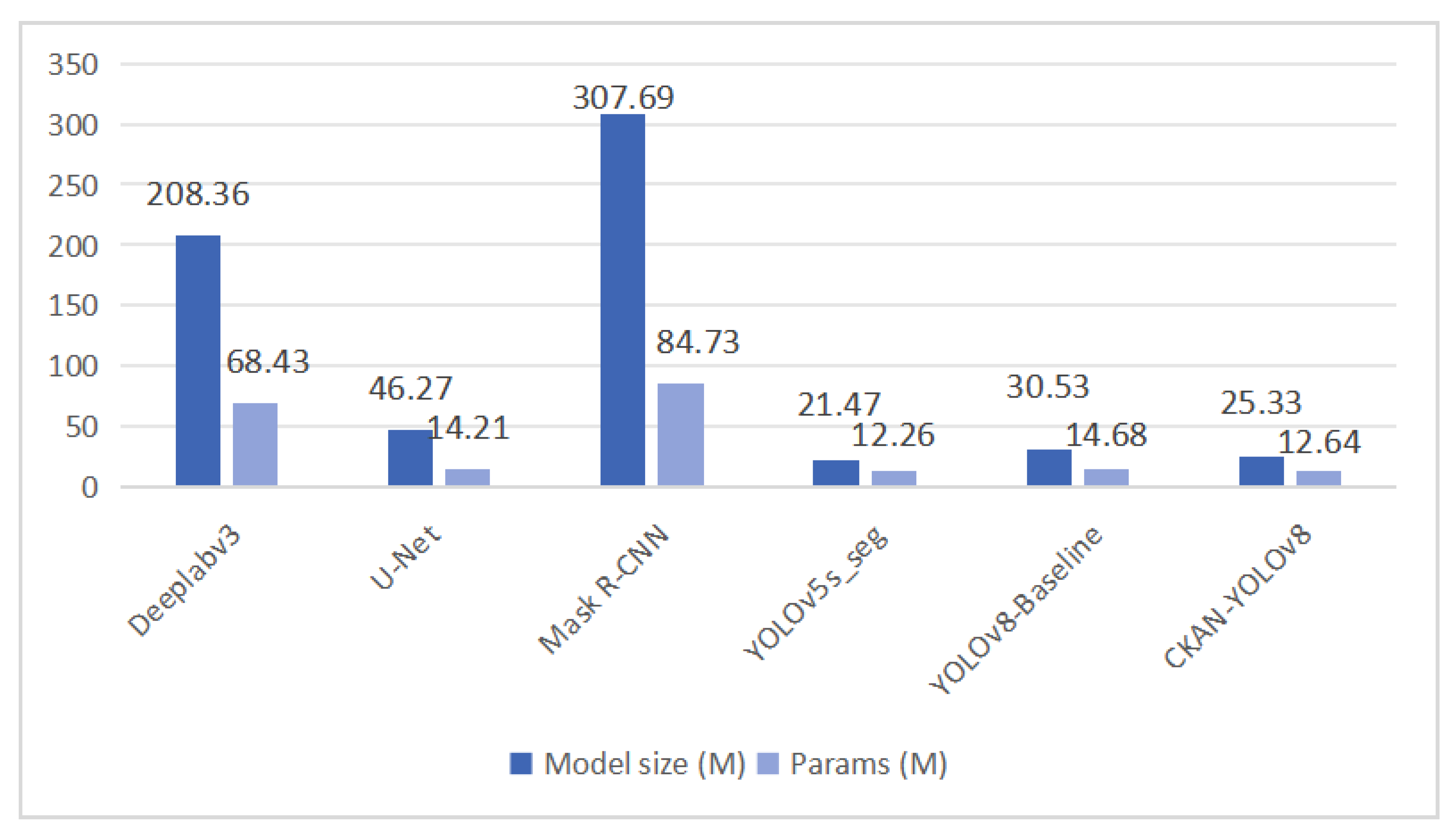

This study presents YOLO-CKAN, a lightweight multi-task network tailored for underwater target detection and segmentation in SSS imagery. By integrating CKAN into the YOLO framework, we address critical challenges including low signal-to-noise ratios, geometric distortions, and computational constraints on UUVs. The proposed CKAN blocks replace traditional convolutions with learnable B-spline activation functions, enabling dynamic adaptation to sonar-specific noise and multi-scale targets while reducing parameter counts by 14% (12.64M vs. 14.68M). The deformable KANConv-PAN further mitigates geometric distortions through spline-optimized multi-scale fusion, ensuring robust feature alignment across varying resolutions. A dual-task head synergizes detection and boundary-sensitive segmentation, achieving state-of-the-art performance with 0.869 AP@0.5 and 0.72 IoU.

The framework’s lightweight design and real-time capability highlight its practicality for UUV deployment. Notably, YOLO-CKAN preserves topological consistency of seabed features, a critical requirement for marine navigation and mapping. While the method demonstrates strong performance on limited datasets, future work will expand to multi-modal data fusion (e.g., bathymetry and AIS) and explore hardware-specific optimizations (e.g., FPGA acceleration) for broader marine engineering applications. This work bridges theoretical advancements in spline-based networks with real-world underwater perception needs, offering a solution for resource-constrained environments.