1. Introduction

Water body segmentation holds significant application value in environmental governance policies and advancements in USV technologies. In the context of environmental monitoring, real-time water detection enables hydrological disaster monitoring through water body segmentation [

1,

2,

3].For autonomous systems, precise delineation of water bodies is essential for vessel navigation [

4,

5,

6]. Recently, the applications of water body segmentation have been further expanded to include ecosystem assessment [

7,

8] and climate change impact analysis [

9].

Traditional water detection systems employ sensors including contact-based devices, radar, sonar, and optoelectronic cameras. However, contact sensors are constrained to static, fixed scenarios with short-range detection capabilities. Fog and intense water surface reflections introduce noise artifacts in radar data, whereas turbulent waves degrade sonar signal integrity. These environmental factors compromise the performance of direct detection systems.In contrast, optoelectronic cameras—functioning as non-contact indirect sensors—require only image acquisition, offering superior adaptability to diverse aquatic environments and cost advantages over radar/sonar systems. Real-time semantic segmentation of optoelectronic camera imagery therefore offers a cost-effective and efficient solution for water surface detection.

This study addresses machine vision-based identification of water regions in outdoor scenes, which is critical for intelligent video surveillance in aquatic environments. Furthermore, water surface segmentation represents a quintessential case of complex image segmentation, providing insights into broader segmentation challenges. Existing water body segmentation methodologies are typically classified into image processing-based and machine learning-based frameworks. Image processing frameworks depend on empirical features (e.g., gradients, textures, edges), which exhibit limitations in generalizability and robustness. For instance, Zhao et al. [

10] employed an adaptive-threshold Canny edge detection algorithm for river boundary detection. However, these frameworks demand a priori environmental knowledge and exhibit performance degradation under substantially varying conditions. With the proliferation of deep learning, machine learning-based frameworks have been deployed for water body segmentation. For example, Zhan et al. [

11] developed an online learning framework leveraging Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for water region detection in unknown navigation scenarios. Han et al. [

12] pioneered the use of Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) for urban flood segmentation. Although these frameworks attain high accuracy, their computational complexity poses significant hardware demands.

Most state-of-the-art deep learning-based water segmentation frameworks require significant computational resources. Given practical deployment constraints and real-time inference requirements, this study proposes a network architecture that balances segmentation accuracy with computational efficiency.The primary challenge involves balancing model parameter complexity and inference efficiency. Therefore, designing a lightweight yet accurate segmentation network specifically optimized for water region recognition has significant academic and practical implications.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

A Global-Local Feature (GLF) Extraction module is proposed to enhance hierarchical feature representation within network depth and width constraints, thereby improving segmentation performance.

A Gated Attention (GA) Module is designed with skip connections to enable efficient feature utilization, enhancing segmentation accuracy and interference robustness.

GFANet is implemented using a lightweight backbone integrated with the proposed modules. Under standardized training protocols, GFANet achieves segmentation accuracy comparable to complex models while demonstrating fewer parameters, lower computational complexity, and faster inference speed.

2. Related Work

Deep learning-driven image semantic segmentation has established itself as a prominent research domain in the past decade. Although deep learning-based segmentation has been widely adopted in autonomous driving for lane detection, its application to complex water body segmentation scenarios remains significantly underexplored, offering a promising research trajectory with substantial potential.

2.1. Feature-Enhanced Image Segmentation

Accurate segmentation of complex boundaries and ambiguous edges poses significant challenges. Continuous advancements in feature representation learning have improved segmentation performance. UNet [

13] employs skip connections for multi-level feature fusion, integrating high-resolution shallow encoder features with deep decoder semantic features via channel-wise concatenation to preserve local details and global context. Traditional CNNs, constrained by limited receptive fields, face challenges in modeling long-range dependencies. PSPNet [

14] addresses this limitation with a pyramid pooling module, which downsamples feature maps via multi-scale pooling, followed by bilinear upsampling and concatenation to enable explicit global context modeling. Concurrently, the DeepLab series [

15] pioneered dilated convolutions, exponentially expanding receptive fields by adjusting dilation rates without parameter increase.

However, uncontrolled receptive field expansion risks local detail loss, introducing a trade-off between global and local feature representation. To resolve this, BiSeNet [

16] introduced a dual-path architecture incorporating a feature fusion module with channel attention weighting to balance speed and accuracy. DANet [

17] pioneered a dual-attention mechanism that captures channel correlations using covariance matrices and adaptively fuses outputs via learnable parameters, thereby improving segmentation precision for complex boundaries. CCNet [

18] further optimized computational efficiency through a recursive criss-cross attention mechanism. This architecture aggregates contextual information along horizontal/vertical axes via two sequential criss-cross attention modules, concatenated with local feature maps to achieve superior segmentation performance.

These works demonstrate that integrating local and global semantic features is essential for segmenting complex boundaries. Building on this foundation, GFANet integrates two novel modules—Global-Local Feature Fusion (GLF) and Global Attention (GA)—to enhance semantic segmentation performance.

2.2. Water Body Segmentation

Early water body segmentation was primarily based on handcrafted features and a priori knowledge. Rankin et al. [

19] developed classification rules using color and texture analysis, though generalization remained limited by scene-specific lighting and terrain variations. Yao [

20] proposed a hybrid framework integrating region growing and texture analysis: initial segmentation using brightness thresholds, followed by K-Means clustering on 9×9 image patches to identify water regions via minimal texture variance. However, shadow interference required stereo vision, thereby increasing computational complexity. To reduce manual intervention, Achar et al. [

21] developed a self-supervised algorithm leveraging RGB, texture, and elevation features for patch-level binary classification, aiming to reduce manual intervention. However, missegmentation persisted in complex boundary regions.

With the proliferation of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), data-driven methodologies gained prominence. Elias et al. [

22,

23] pioneered encoder-decoder architectures for Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) water detection, achieving real-time segmentation. However, single-scene training limited architectural generalization. Eltner et al. [

24] integrated CNN segmentation with structure-from-motion (SfM) for 3D water level measurement. However, cross-river applications necessitated manual parameter calibration. Blanch et al. [

25] addressed this limitation by training a universal CNN on multi-basin heterogeneous datasets, achieving significant improvements in cross-regional river segmentation. Cao et al. [

26] and Miao et al. [

27] proposed high-low feature connection methods but neglected receptive field mismatches. Meanwhile, Liang et al. [

28] enhanced Deeplabv3+ for USV navigable area detection, improving F1-score by 6.8% over baselines.

Recent advancements have focused on lightweight hybrid architectures to balance segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency. Kang et al. [

29] developed CoastFormer, incorporating axial attention in the encoder to capture long-range coastline features while maintaining high-resolution outputs using a CNN decoder. Zhang et al. [

30] developed MSF-Net, leveraging complementary infrared and visible-light data to enhance turbid water detection, thereby achieving a Dice coefficient of 91.5%.

Notwithstanding these advancements, key challenges remain: limited discriminative capability under complex lighting and turbid conditions, and the challenge of balancing lightweight designs with high segmentation precision. This study introduces a multi-modal adaptive network featuring dynamic feature selection and hierarchical attention mechanisms to balance robustness and real-time computational performance.

3. Materials and Methods

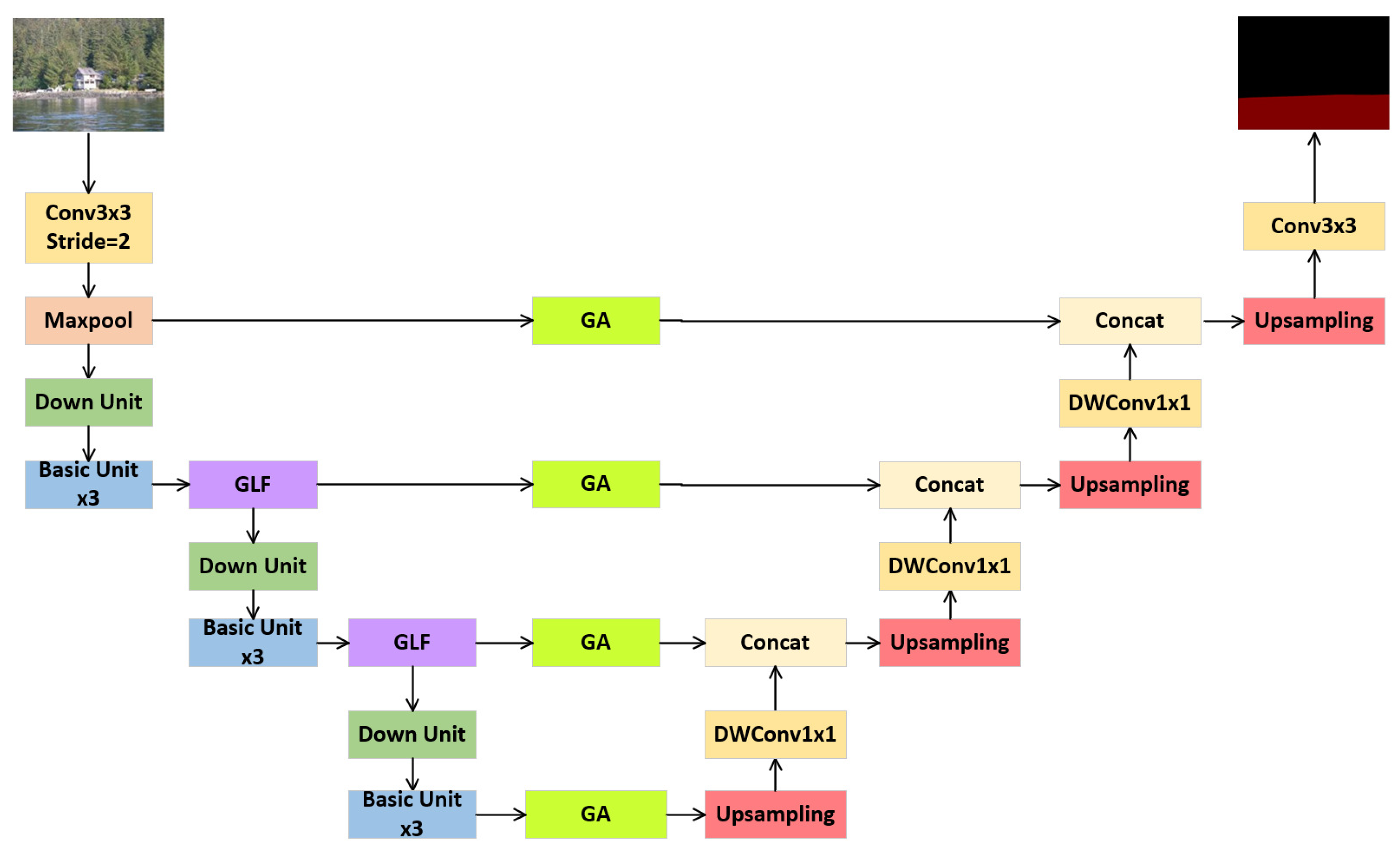

To address the speed-accuracy trade-off in practical applications, this study introduces GFANet (Global-Local Feature Attention Network), a lightweight architecture designed for real-time water surface semantic segmentation. GFANet employs an encoder-decoder architecture comprising three core components: (1) a backbone, (2) a Global-Local Feature (GLF) Extraction module, and (3) a Gated Attention (GA) module.

3.1. Backbone

A lightweight and efficient backbone was developed to enhance inference speed. Ma et al. [

30] developed ShuffleNetV2, demonstrating its superiority over competing lightweight architectures. Therefore, to satisfy real-time inference requirements, ShuffleNetV2 was adopted as the backbone architecture.

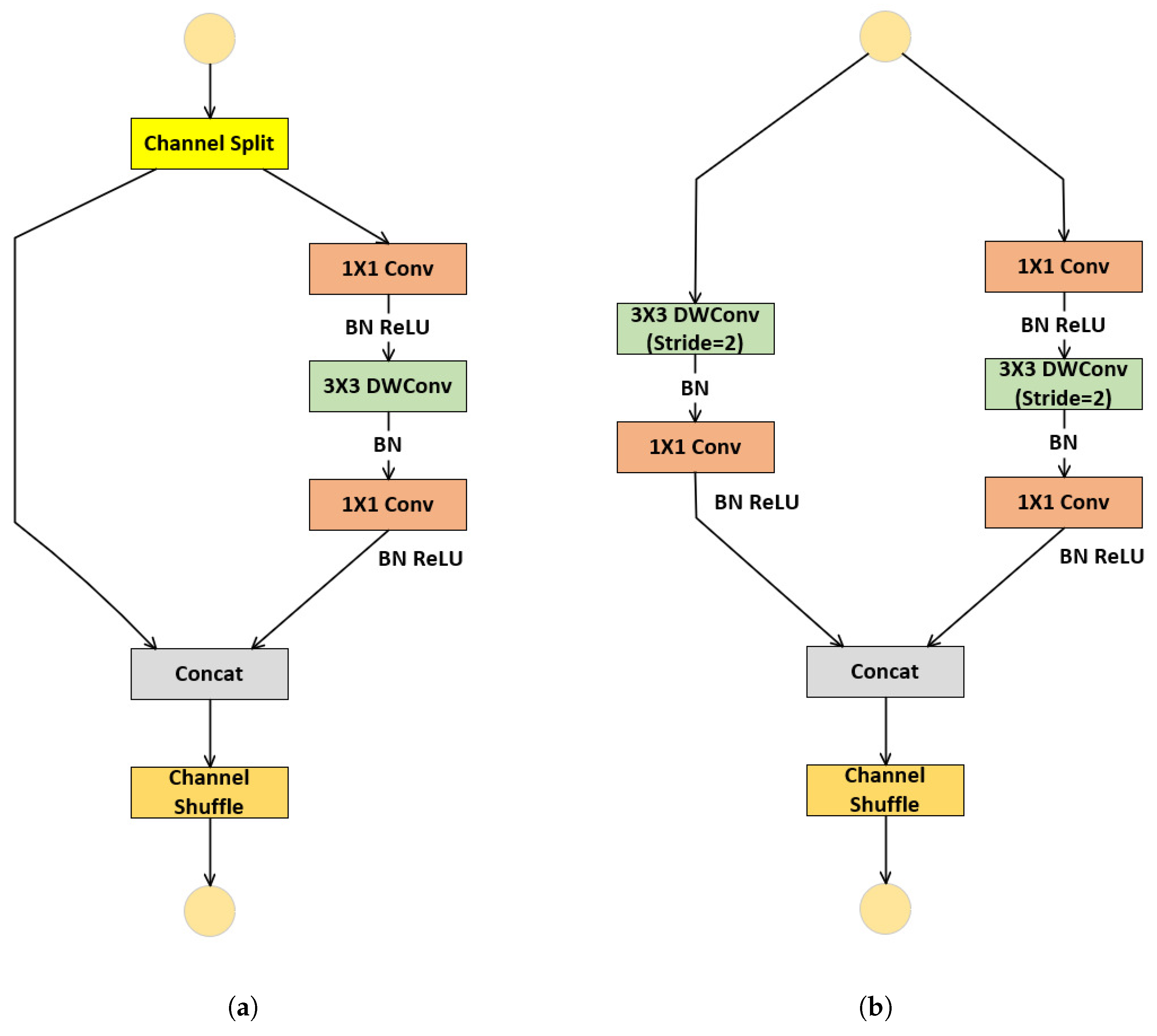

The main design of ShuffleNetV2 includes the Basic Unit for feature representation, as shown in

Figure 1(a), and the Down Unit for downsampling, as shown in

Figure 1(b). In the basic unit, the input with

c feature channels undergoes channel splitting into two branches. One branch preserves the identity mapping, while the other branch applies three convolutions with consistent input/output dimensions. The branch outputs are concatenated, maintaining channel count consistency. Channel shuffle is employed to fuse features and facilitate inter-branch communication. In the Down Unit, channel splitting is omitted, and convolution stride is increased to double output channels while halving spatial resolution.

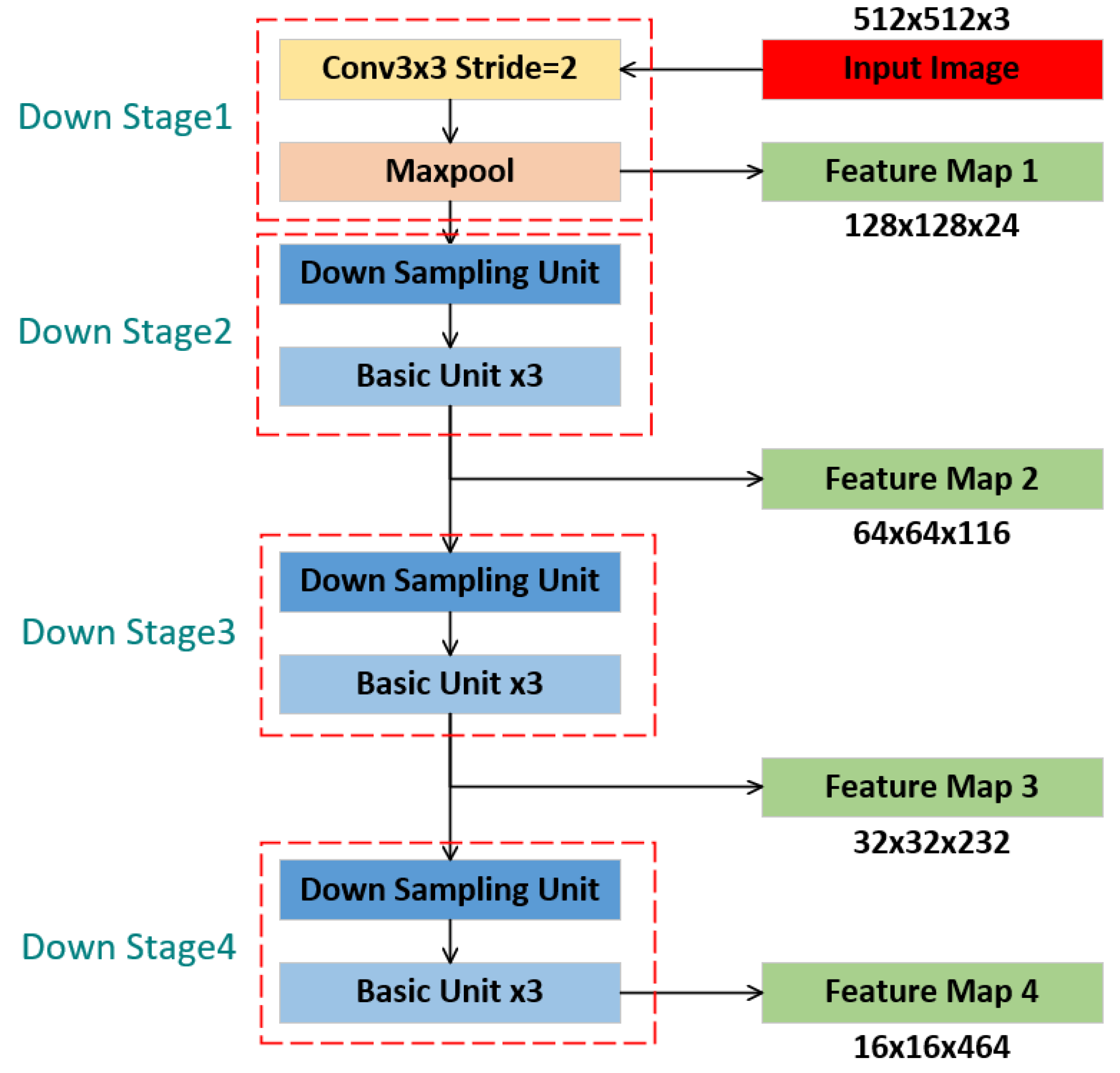

Based on these two fundamental units and with reference to the design of ShuffleNet V2, we constructed the encoder backbone, as depicted in

Figure 2. The encoder consists of four downsampling stages. The first stage involves feature transformation and extraction using a downsampling convolution, followed by max pooling. Subsequent feature extraction is carried out through three additional downsampling stages, which capture deeper semantic information. To ensure model efficiency and a lightweight design, the last three downsampling stages uniformly utilize one downsampling unit and three basic units. Feature maps from each downsampling stage are retained for skip connections.

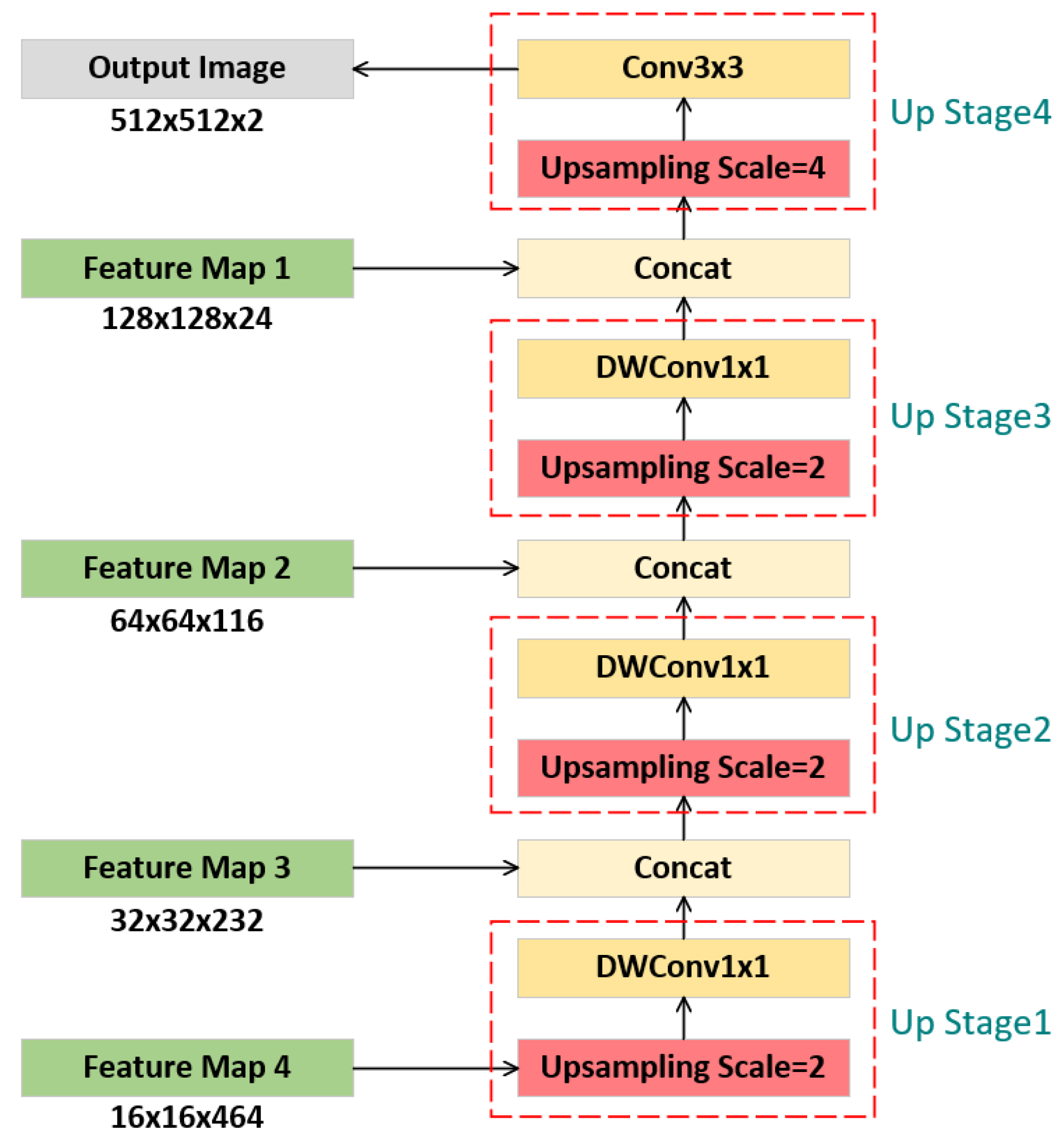

Corresponding to the encoder, the decoder comprises four upsampling stages aimed at progressively restoring image resolution. The detailed architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3. Stage 4 utilizes a 4× upsampling ratio, whereas the other stages employ 2× upsampling. The outputs of upsampling stages 1-3 are fused with feature maps 3-1 from the encoder via channel-wise concatenation, thus supplementing deep semantic features with shallow spatial details. To achieve model lightweighting, we apply 1×1 kernel depthwise separable convolutions subsequent to upsampling operations. This design significantly reduces the parameter count and computational overhead, while preserving feature representation capability. Lastly, upsampling stage 4 reconstructs the image to its original resolution and conducts pixel-wise semantic classification to accomplish the segmentation task.

3.2. GLF

To improve the detailed information extraction and enhance the feature extraction capability of the network, we introduce the Global-Local Feature Extraction (GLF) module. The architecture of this module is depicted in

Figure 4.

The GLF module integrates local and global information, multi-scale features, attention mechanisms, and channel shuffling techniques. These strategies augment the diversity and expressive capacity of feature extraction, thereby allowing the module to tackle challenges like complex backgrounds in computer vision tasks and limited feature extraction capabilities of networks.Consequently, the network training performance becomes more stable.

Specifically, the module executes dual-branch feature extraction and aggregation processes on the input feature maps. One branch extracts local features by applying four dilated convolutions with varying dilation rates.

The input feature maps (x) undergo four concurrent dilated convolution operations. The concatenated outputs from these four operations constitute the initial local features, as detailed below:

Subsequently, a channel shuffle operation is utilized to thoroughly blend features originating from diverse convolutional layers, thereby significantly improving the flow of inter-channel information. Furthermore, a 1×1 convolutional layer is employed to transform the blended features into dimensions that match the input, yielding the ultimate local feature output, as detailed below:

The alternative branch utilizes a self-attention mechanism for extracting global features. This methodology facilitates global weighting, enabling each position to directly access and dynamically modify attention weights across all spatial positions, thus augmenting contextual understanding. Initially, the branch extracts the Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) tensors via pyramid pooling operations. The subsequent implementation steps are as follows:

As Equation (

4), the dot product between Q and K is computed, followed by scaling with a factor of

(where c represents the feature dimension) to ensure numerical stability and address gradient vanishing or exploding problems. Subsequently Equation (

5), a softmax function is applied along the sequence dimension (usually the last axis) to transform attention scores into normalized probability distributions, indicating the relative significance of various spatial positions. Finally, the attention weights are utilized to compute the weighted sum of the Value (V) tensor, as shown in (

6), thereby generating aggregated global contextual information. Subsequently, a linear transformation using convolution is applied to adjust the feature dimensions, resulting in the refined global features, as presented in (

7).

Equation (

8) represents the output of the Global-Local Fusion (GLF) model. The features from both branches are combined through element-wise addition to produce the final feature extraction output. This fusion strategy integrates fine-grained spatial details from local features with contextual semantics derived from global representations in a synergistic manner, ultimately resulting in a comprehensive feature map suitable for segmentation tasks.

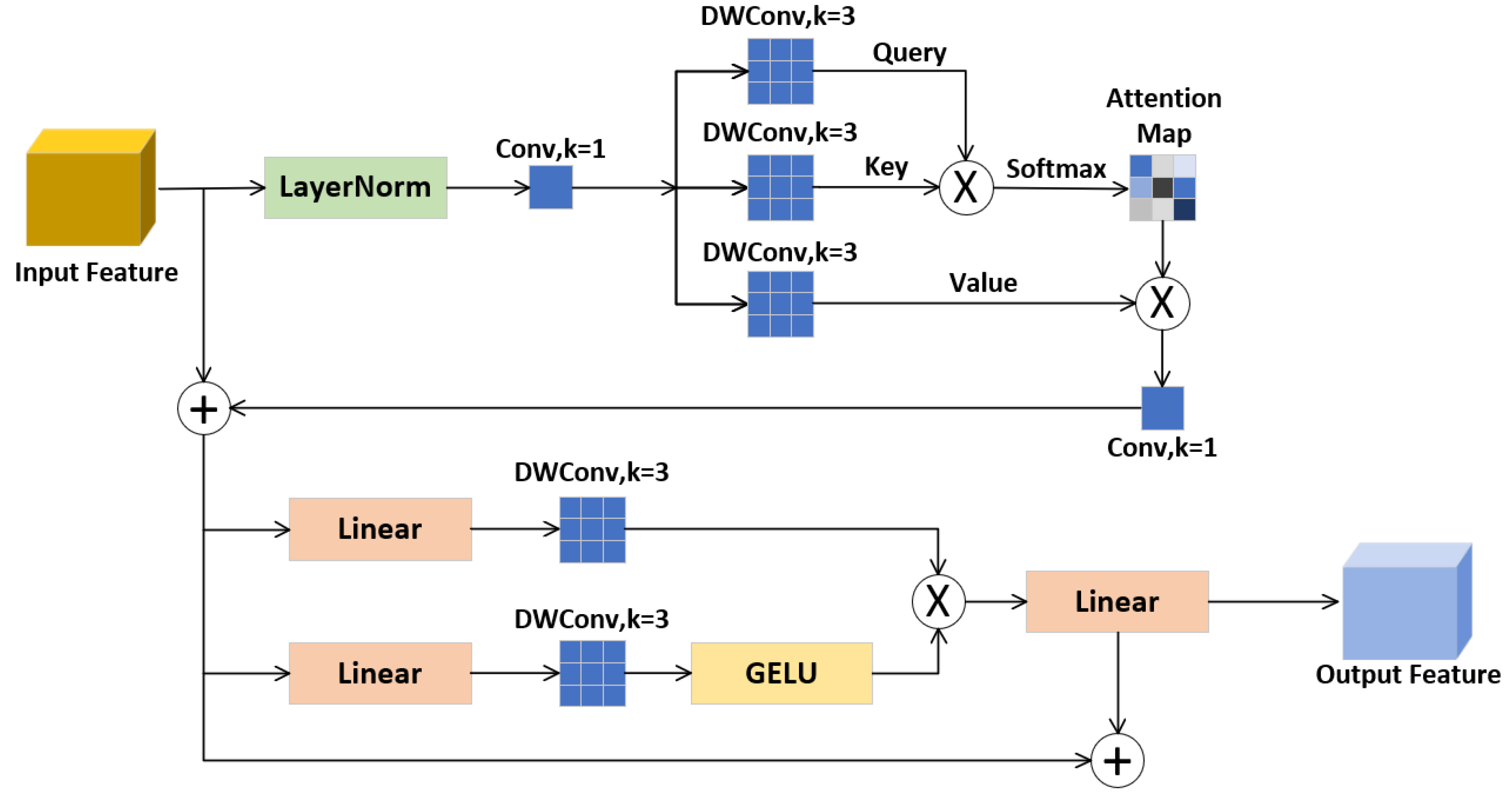

3.3. GA

In semantic segmentation models, skip connections play a crucial role in establishing a feature bridge between the encoder and decoder, reducing the loss of spatial details due to continuous downsampling, which consequently enhances the accuracy of target boundary localization. However, skip connections based on direct addition often introduce substantial amounts of low-level textures and noise, making it difficult to effectively distinguish important features.

To overcome these limitations, we propose the Gated Attention Module (GA), which aims to address the issues associated with direct skip connections. The structure of the GA module is illustrated in

Figure 5. The Gated Attention (GA) module achieves its functionality through two residual-connected operations that synergistically integrate attention and gating mechanisms.The GA module initially applies Layer Normalization (LN) to standardize the input features. Then, it extracts attention parameters via parallel convolutions, facilitating the integration of spatial attention (for identifying key regions) and channel attention (for adjusting feature importance). This results in a dual-dimensional attention mechanism that is spatially sensitive and channel-adaptive, significantly improving feature discriminability in complex scenes.The implementation principle of this part of the attention mechanism is as follows:

Lastly, a dual-branch gating mechanism is utilized to suppress irrelevant features, as detailed below:

The output of GA model as Equation (

14). The GA module enhances the expressive power of low-level features by aggregating multiple enhancement results, reducing redundancy while preserving critical details.

3.4. GFANet

The lightweight backbone guarantees exceptionally high baseline inference speeds for the model. Integration of the GLF (Global-Local Feature) and GA (Gated Attention) modules results in a slight decrease in inference efficiency compared to the original backbone, but significantly enhances segmentation accuracy. This design allows GFANet to maintain competitive inference speeds while achieving high-precision performance, thereby achieving an optimal balance between computational efficiency and segmentation quality.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, the complete GFANet architecture is realized by strategically integrating the GLF and GA modules into appropriate positions within the backbone network. GFANet’s primary objective is to achieve segmentation accuracy comparable to advanced semantic segmentation networks, while significantly reducing memory usage and execution time.

4. Experiment

Comparative experiments were conducted between GFANet and representative semantic segmentation architectures. Three benchmark datasets widely used in water body segmentation were employed to evaluate GFANet’s performance against state-of-the-art approaches.

4.1. Experiment Configuration

Experiments were conducted on a Windows 10 OS with an Intel Core i5-12400 CPU (2.5 GHz, 32 GB RAM) and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU (11 GB VRAM).The deep learning framework comprised PyTorch 2.2.2 (Python 3.11.9), CUDA 12.1, and cuDNN 8.8.

Network parameters were empirically optimized to ensure consistent testing conditions across models, accounting for baseline model complexity and computational demands. Input resolution was fixed at 512×512, and the Adam optimizer (momentum = 0.9) was adopted. An initial learning rate of 1e-4 was used with a warm-up cosine decay scheduler. Batch size was 8, and maximum training epochs were 150. Models were trained to convergence, defined by stabilized loss and evaluation metrics.

Data augmentation was applied during training to enhance dataset diversity and evaluate model robustness to interference.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

This study employs five evaluation metrics: mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), mean Pixel Accuracy (mPA), GigaFLOPS (GFLOPs), parameter count (Params), and frames per second (FPS). Among these, mIoU quantifies segmentation region accuracy, while mPA measures the proportion of correctly classified pixels. Both metrics quantify segmentation performance.GFLOPs quantify computational complexity, reflecting GPU computational efficiency. Params quantify model complexity by parameter count, indicating memory footprint. FPS quantifies real-time performance by measuring video stream processing rate. The mIoU and mPA are calculated as follow:

where TP (True Positive) represents the count of pixels accurately predicted as positive. TN (True Negative)signifies the count of pixels accurately predicted as negative. FP (False Positive) indicates the count of pixels incorrectly predicted as positive. FN (False Negative) indicates the number of pixels that are incorrectly predicted to be negative. N is the number of categories.

4.3. Experiments Based on the Riwa Dataset

To evaluate the performance of the proposed network, we compared it with various architectures, including UNet [

13], DeeplabV3+ [

15] (backbone = Xception), PSPNet [

14] (backbone = ResNet50), and SegNet [

32], which are large-scale CNNs, as well as LEDNet [

32], a lightweight CNN. To ensure fairness, no pre-trained weights were used across all models. Comparative results, including evaluation metrics and model parameters, are presented in

Table 1. GFANet outperforms all baseline architectures across evaluated metrics. GFANet attains mIoU 82.59% and mPA 90.05%, outperforming all baselines except SegNet (mIoU -0.27%, mPA -0.41%)—minimal accuracy gaps. GFANet maintains 4.41M parameters and 7.15 GFLOPs—substantially fewer than large-scale CNNs and marginally higher than lightweight LEDNet.GFANet exhibits real-time inference speed (FPS:

Table 1), outperforming large-scale CNNs and closely matching lightweight LEDNet.Detailed results are provided in

Table 1.

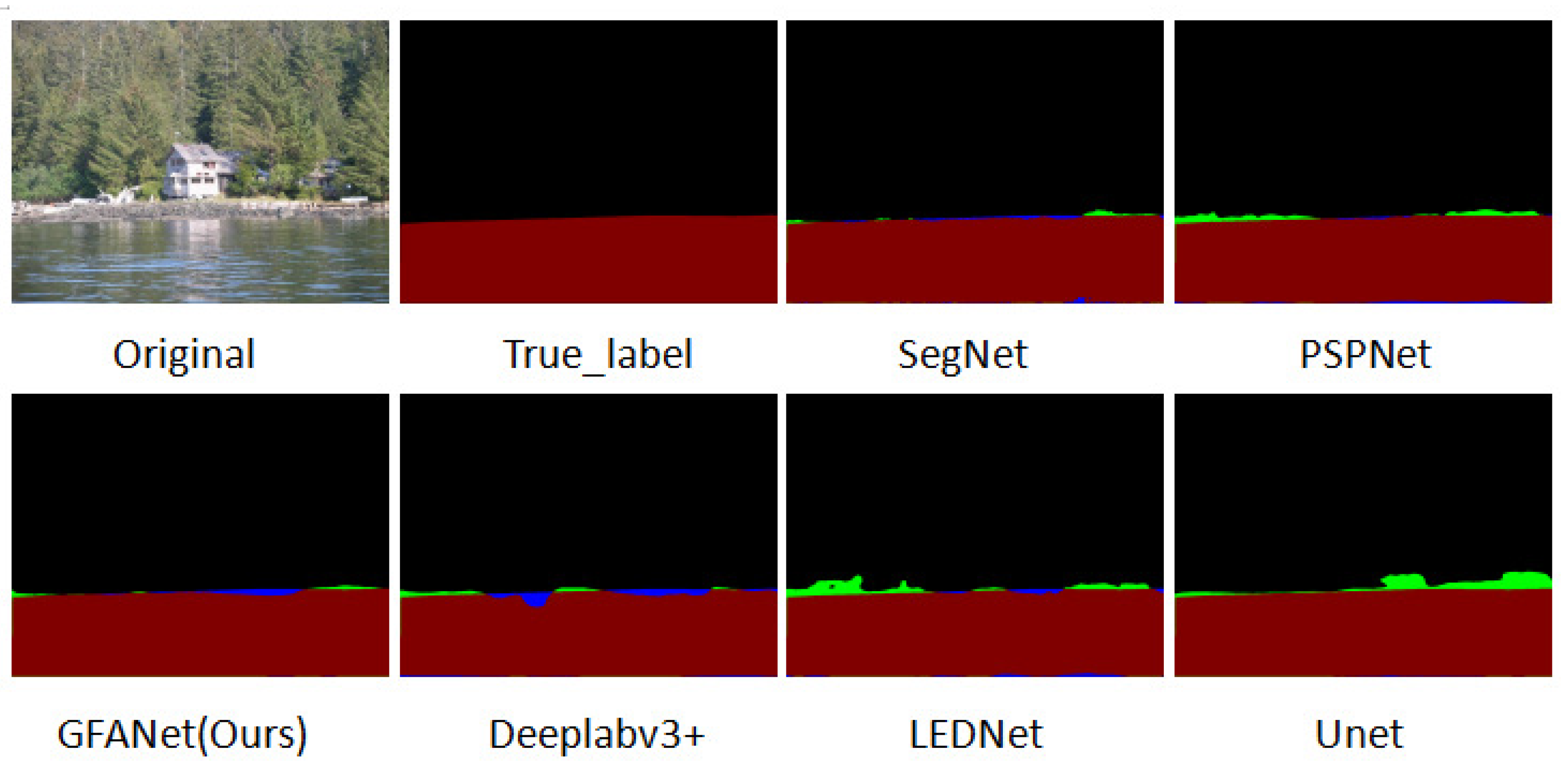

Segmentation results of representative architectures are visualized in

Figure 7 with misclassified pixels: green (false water) and blue (false background). GFANet achieves performance comparable to top-performing SegNet while outperforming other architectures, exhibiting superior edge delineation precision. The original image accentuates this difference: all architectures except GFANet and SegNet exhibit significant errors at riverbank edges. While SegNet misclassifies a small bottom-right water region as background, GFANet accurately segments the entire water area.

Although GFANet exhibits marginally inferior edge discrimination performance compared to SegNet, the discrepancy is negligible. GFANet attains nearly fourfold faster inference speed than SegNet, alongside significantly reduced computational complexity and parameter count. This highlights GFANet as a balanced architecture, achieving a favorable trade-off between minimal accuracy reduction and substantial inference speed gains.

4.4. Experiments Based on the WaterSeg Dataset

The Water dataset was proposed by Liang et al. [

34] for water segmentation in videos and images within Video Object Segmentation (VOS) research. Adopting the DAVIS dataset format, it has gained widespread adoption.The dataset can be downloaded from

.

Given fixed model parameter counts and input size-proportional computational costs, subsequent results exclude model size metrics, focusing on mIoU and mPA for comparative analysis. Quantitative results of models on the WaterSeg dataset are presented in

Table 1 .

GFANet maintains superior performance on the WaterSeg dataset (

Table 2), achieving mIoU 88.49% and mPA 93.68%—marginally lower than PSPNet (<0.5%) and significantly outperforming other architectures.

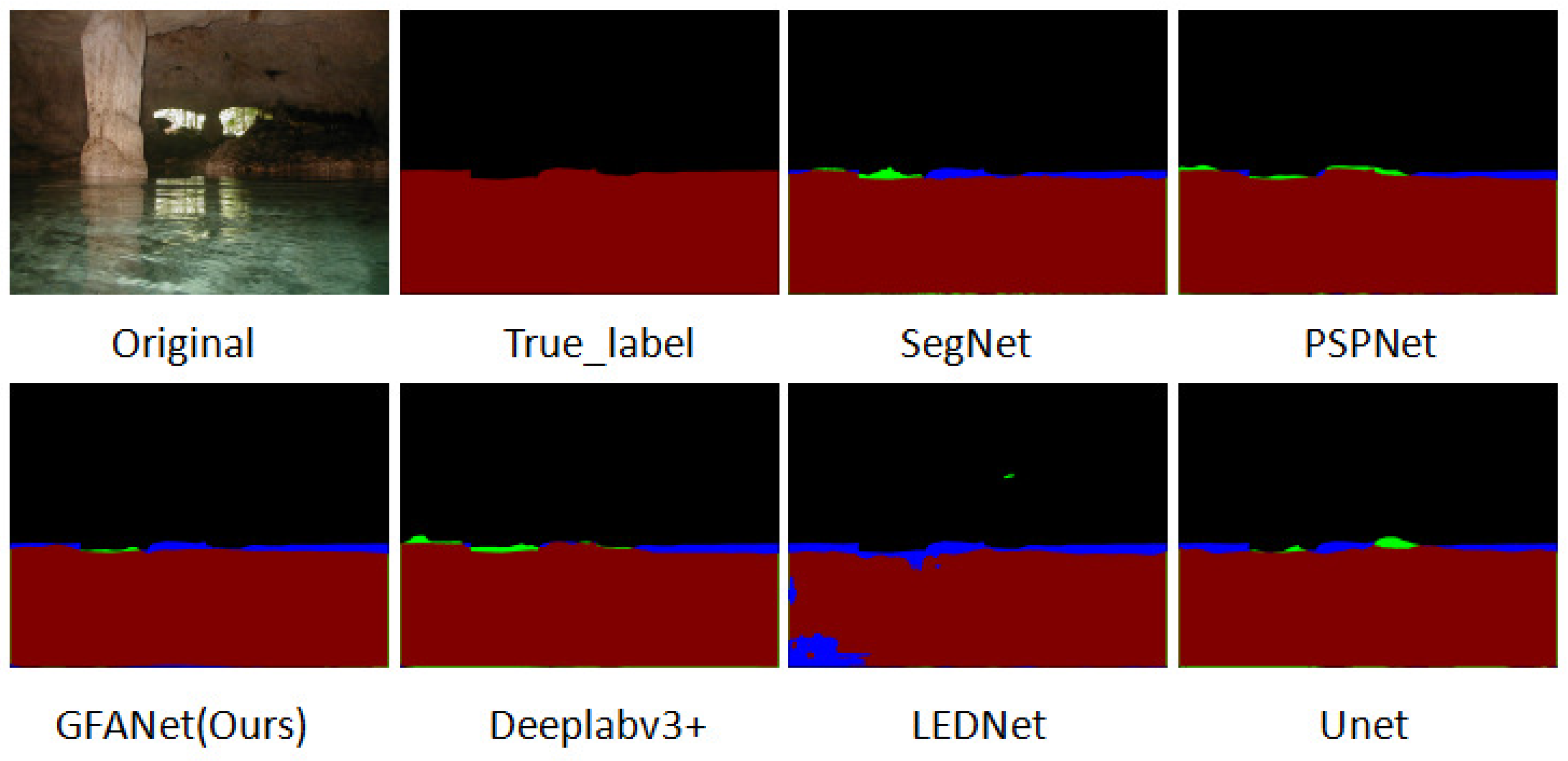

Visualization results on the dataset are presented in

Figure 8. Under low-light conditions, all architectures exhibit significant edge detection performance degradation.

Under these scenarios, SegNet—previously the top performer—exhibits accuracy degradation, while PSPNet achieves the highest segmentation precision. GFANet maintains competitive performance, exhibiting comparable overall error to PSPNet. GFANet retains significant advantages in inference speed and model complexity over other architectures.

4.5. Experiments Based on the USVInland Dataset

The USVInland dataset [

35] developed and released by Orca-Tech researchers, focuses on inland waterway scenarios.

Quantitative results of architectures on the USVInland dataset are presented in

Table 3. All architectures achieve higher accuracy on USVInland, attributed to the dataset’s simpler image characteristics compared to other benchmarks. Under these conditions, performance disparities between architectures diminish, yet GFANet outperforms competitors—closely matching PSPNet (mIoU: +0.02%, mPA: +0.04%).

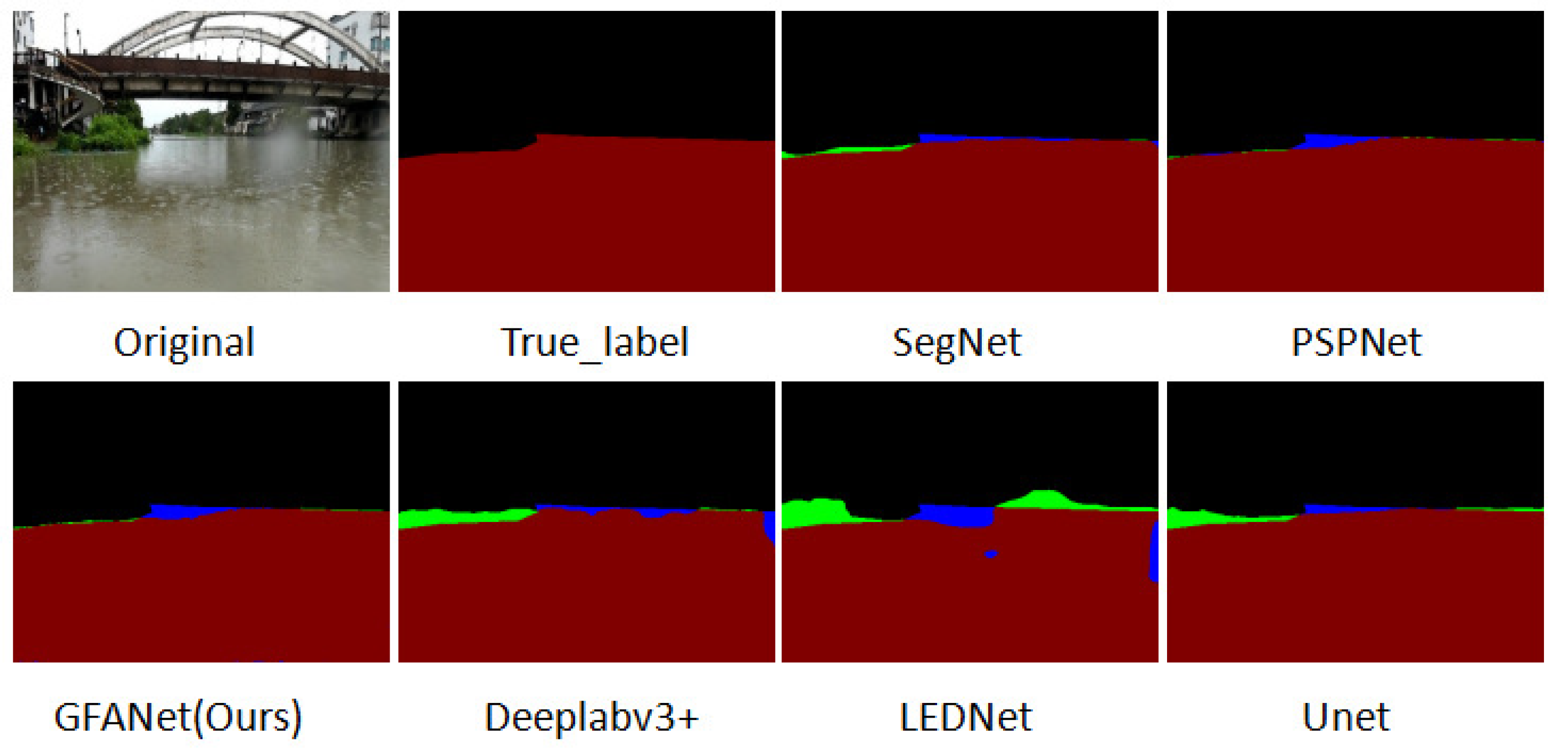

To further characterize architectural differences, rainy interference experiments are presented on challenging imagery. Results are visualized in

Figure 9. All architectures except GFANet and PSPNet exhibit substantial segmentation errors in the left riverbank region. For distant riverbank details challenging for all architectures, GFANet and PSPNet demonstrate comparable performance.

Experiments on three datasets (Riwa, WaterSeg, USVInland) encompassed images under diverse lighting conditions: bright, dim, and partially occluded scenarios. Results reveal GFANet exhibits superior performance in high-brightness environments and reduced performance in low-light conditions. Nevertheless, GFANet consistently delivers more precise water area and boundary segmentation than competing architectures across diverse environments. This highlights GFANet’s superior transferability and enhanced robustness, enabling effective adaptation to diverse environmental conditions in water segmentation. Collectively, GFANet is ideally suited for real-world water surface semantic segmentation applications.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces GFANet (Global-Local Feature Attention Network), a real-time water surface semantic segmentation architecture leveraging local-global feature extraction and gated attention mechanisms. Comprehensive experiments were performed on three benchmark datasets: RIWA, WaterSeg, and USVInland. Evaluation was assessed across four dimensions: segmentation accuracy, computational complexity, model size (parameters), and inference speed. Experimental results (as detailed in

Table 1 and

Figure 7) reveal GFANet achieves a favorable balance between segmentation precision and computational efficiency, maintaining high accuracy with significantly reduced parameters and computational complexity compared to conventional CNN architectures.

While this study simulated three common real-world environmental scenarios (bright, low-light, and rain-interfered conditions), practical deployment tests on unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) or surveillance devices were not included.

Future research will focus on deploying GFANet on unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) to address real-world operational challenges. This entails systematic exploration of: (1) hardware-software co-design for embedded implementation, (2) computational graph optimization for resource-constrained edge devices, and (3) dynamic video stream analysis with multisensor fusion extensions. These efforts aim to: (1) resolve deployment-specific bottlenecks, (2) expand application scenarios in marine environmental monitoring and intelligent navigation systems, and (3) validate GFANet’s practical utility in real-world contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J.; methodology, S.X.; writing—original draft preparation, S.X; writing—review and editing, S.X. and L.J.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have used publicly available data in this manuscript. The dataset link is mentioned in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yadav, A.; Nascetti, A.; Ban, Y. Attentive Dual Stream Siamese U-Net for Flood Detection on Multi-Temporal Sentinel-1 Data. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17-22 July 2022; pp. 5222–5225. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Fuentes, L.; Rossi, C.; Skinnemoen, H. River segmentation for flood monitoring. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Boston, MA, USA, 11-14 December 2017; pp. 3746–3749. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, H.; Katayama, T.; Song, T.; Shimamoto, T. Semantic Segmentation of River Video for Smart River Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 13th Global Conference on Consumer Electronics (GCCE), Kitakyushu, Japan, 29 October - 01 November 2024; pp. 678-681. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.J.; Luo, W.T.; Xu, F.H.; Wei, C.Y. River boundary recognition algorithm for intelligent float-garbage ship. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Electronic Design, Xi’an, China, 15-17 August 2018; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Marine Robotics Lab. Real-time semantic segmentation for USV obstacle avoidance. In Autonomous Navigation Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2023; pp. 1023–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, H.; Xiao, C. DMTN-Net: Semantic Segmentation Architecture for Surface Unmanned Vessels. Electronics 2024, 13, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Global Coastal Ecosystem Monitoring, 2nd ed.; United Nations Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Wu, H.; Huang, J.; Zhong, H.; He, M.; Su, M.; Yu, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J. HA-Unet: A Modified Unet Based on Hybrid Attention for Urban Water Extraction in SAR Images. Electronics 2022, 11, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC Technical Annex: CNN-based glacial lake outburst flood early warning. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Zhao, J.; Yu, H.; Gu, X.; Wang, S. The edge detection of river model based on self-adaptive Canny Algorithm and connected domain segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2010 8th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, Jinan, China, 7-9 July 2010; pp. 1333–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, W.; Xiao, C.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, H.; Xiu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, X.; Liu, X.; Li, Q. Autonomous Visual Perception for Unmanned Surface Vehicle Navigation in an Unknown Environment. Sensors 2019, 19, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Nguyen, C.; You, S.; Lu, J. Single Image Water Hazard Detection using FCN with Reflection Attention Units. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8-14 September 2018; pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5-9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition(CVPR), Hawaii, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 2881-2890. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semanticimage segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8-14 September 2018; pp. 801-818. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Wang, J.; Peng, C.; Gao, C.; Yu, G.; Sang, N. Bisenet: Bilateral segmentation network for real-time semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8-14 September 2018; pp. 32-341. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual attention network for scene segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CA, USA, 15-20 June 2019; pp. 3146-3154. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, C.; Wei, Y. ; Liu,W. In Ccnet: Criss-cross attention for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, South Korea, 27 October - 2 November 2019; pp. 603-612. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, A.L.; Matthies, L.H.; Huertas, A. Daytime water detection by fusing multiple cues for autonomous off-road navigation. In Transformational Science And Technology For The Current And Future Force; World Scientific: Bukit Timah, Singapore, 2006; pp. 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, J.; Xu, D. Multi-feature fusion based outdoor water hazards detection. In Proceedings of the 2007 International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Harbin, China, 5-8 August 2007; pp. 652–656. [Google Scholar]

- Achar, S.; Sankaran, B.; Nuske, S.; Scherer, S.; Singh, S. Self-supervised segmentation of river scenes. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9-13 May 2011; pp. 6227–6232. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, M.; Kehl, C.; Schneider, D. Photogrammetric water level determination using smartphone technology. Photogramm. Rec. 2019, 34, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Maas, H.G. Measuring water levels by handheld smartphones – A contribution to exploit crowdsourcing in the spatio-temporal densification of water gauging networks. Int. Hydrogr. Rev. 2022, 27, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltner, A.; Bressan, P.; Akiyama, T.; Gonçalves, W.; Junior, J. Using deep learning for automatic water stage measurements. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR027608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanch, X.; Wagner, F.; Hedel, R.; Grundmann, J.; Eltner, A. Towards automatic real-time water level estimation using surveillance cameras. Proceedings of EGU General Assembly 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23-27 May 2022; pp. 3225. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R. Water body extraction from high spatial resolution remote sensing images based on enhanced u-net and multi-scale information fusion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, R.; Ren, T.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, Y. A method of water body extraction based on multiscale feature and global context information. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 12138–12152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L; Xiong, R; Wu, J. R.; Yan, X.M.; Yang, C.L.; Zhang, Y.J.; He, Y.Z. Fast Segmentation Algorithm of USV Accessible Area Based on Attention Fast Deeplabv3. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 24168–24177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Guan, H.Y.; Ma, L.F.; Wang, L.Y.; Xu, Z.S.; Li, J. Waterformer: a coupled transformer and cnn network for waterbody detection in optical remotely-sensed imagery. ISPRS-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 206, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Ma, F.; Yin, Q. Superpixelwise likelihood ratio test statistic for polsar data and its application to built-up area extraction. ISPRS-J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 209, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F.; Eltner, A.; Maas, H.; Yin, Q. River water segmentation in surveillance camera images: A comparative study of offline and online augmentation using 32 CNNs. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 119, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Xiong, j.; Gao, G.W.; Wu, X.F.; Latecki, L.J. Lednet: A Lightweight Encoder-Decoder Network for Real-Time Semantic Segmentation. Proceedings of 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22-25 September 2019; pp. 1860-1864. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.Q.; Jafari, N.; Luo, X.; Chen, Q.; Cao, Y.P.; Li, X. WaterNet: An adaptive matching pipeline for segmenting water with volatile appearance. Comput. Vis. Media 2020, 6, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.W.; Jiang, M.X.; Zhu, J.N.; Liu, Y.M. Are We Ready for Unmanned Surface Vehicles in Inland Waterways? The USVInland Multisensor Dataset and Benchmark. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 3964–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).