Submitted:

27 March 2025

Posted:

30 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. What Is Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis (ESDA)

2. Basic Univariate ESDA

2.1. For Continuous Variables

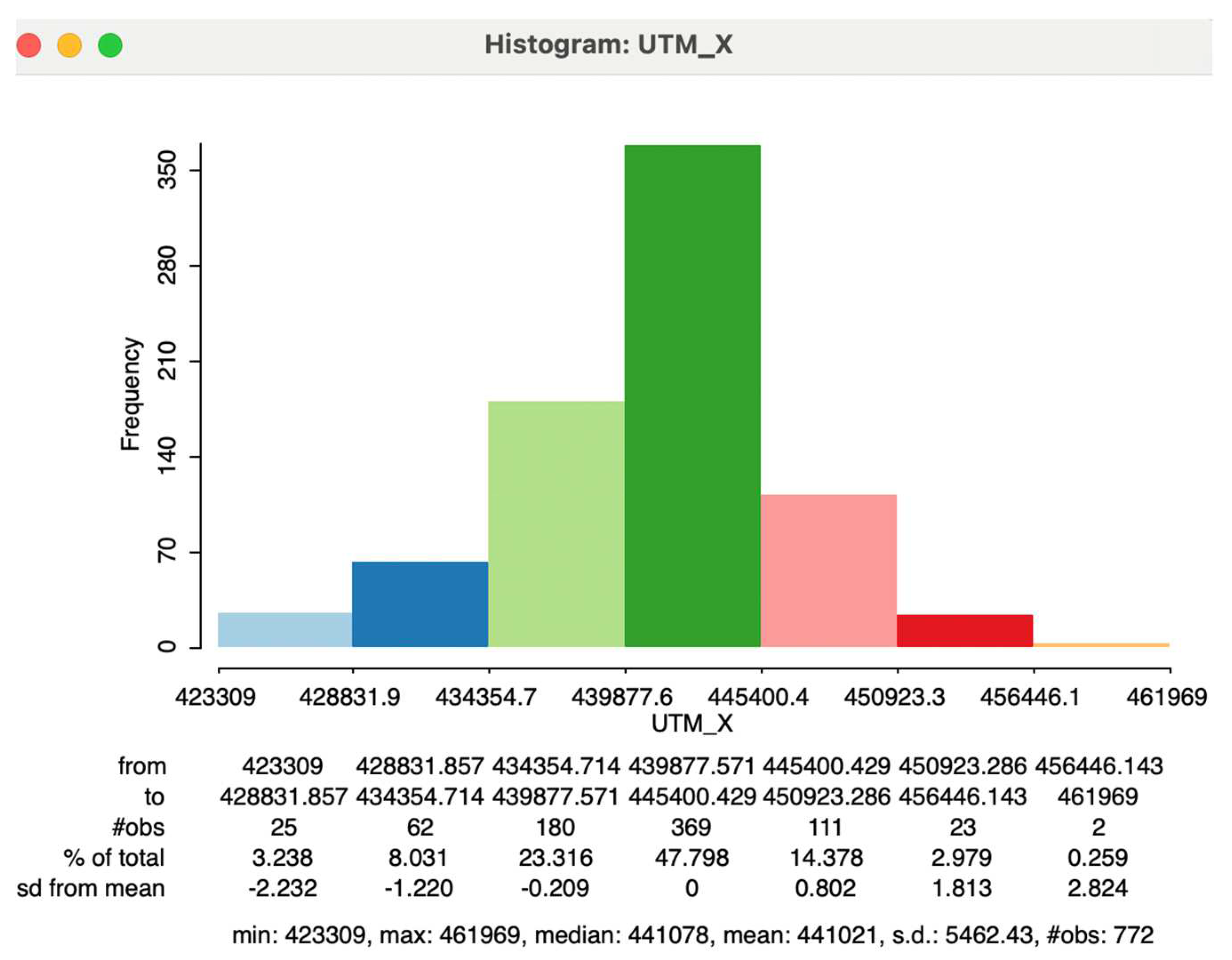

2.1.1. Histogram

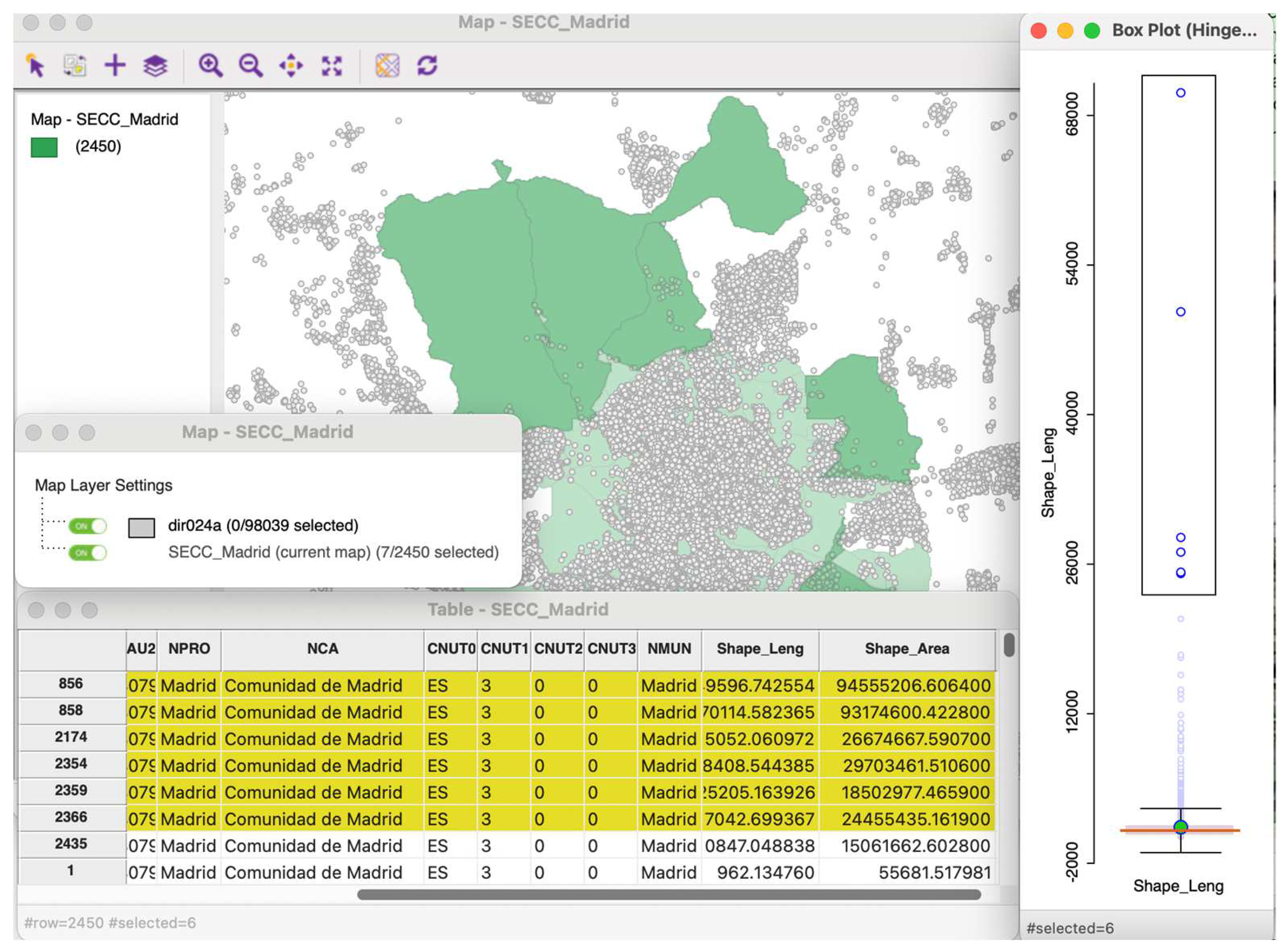

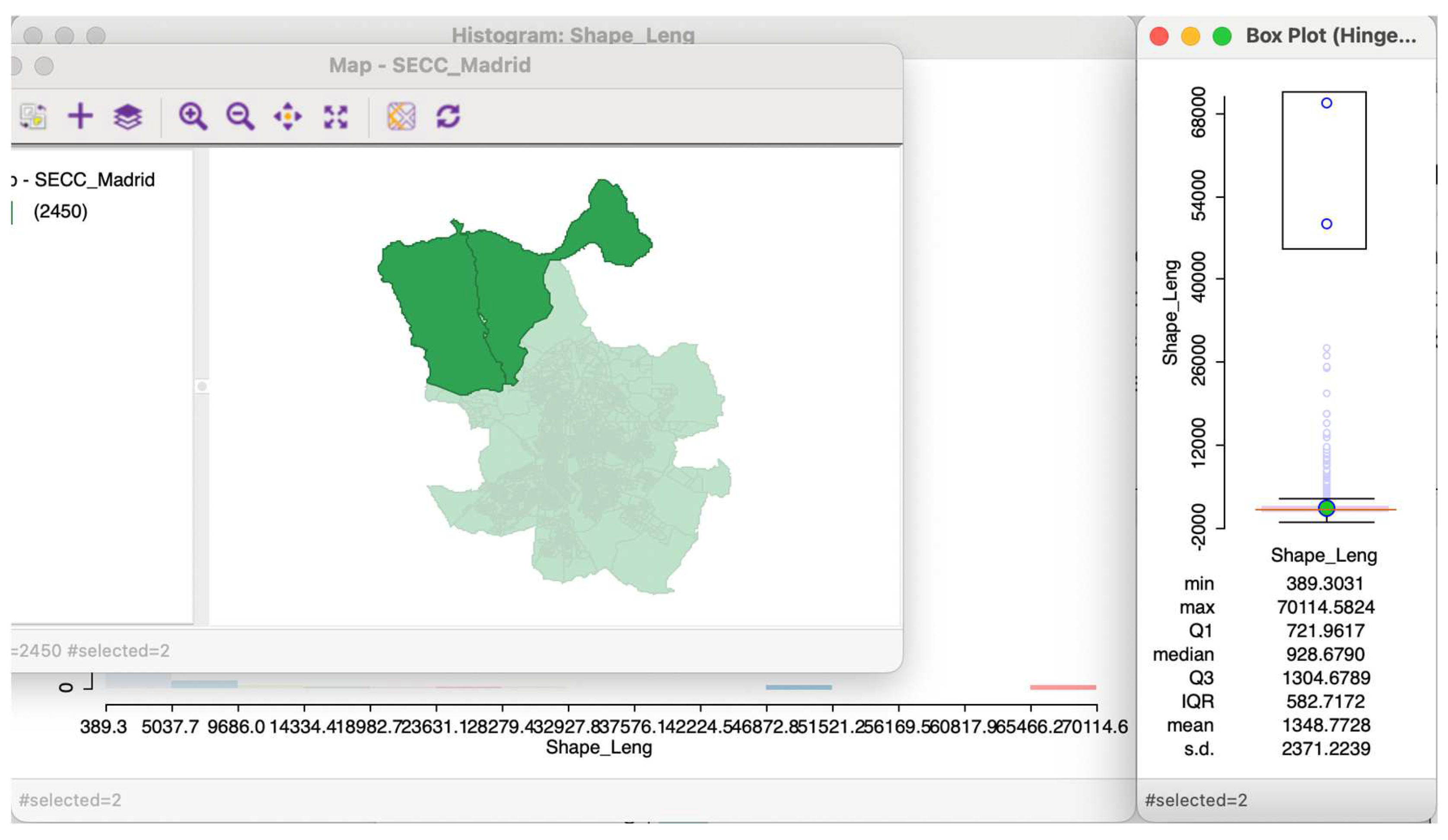

2.1.2. Box Plot

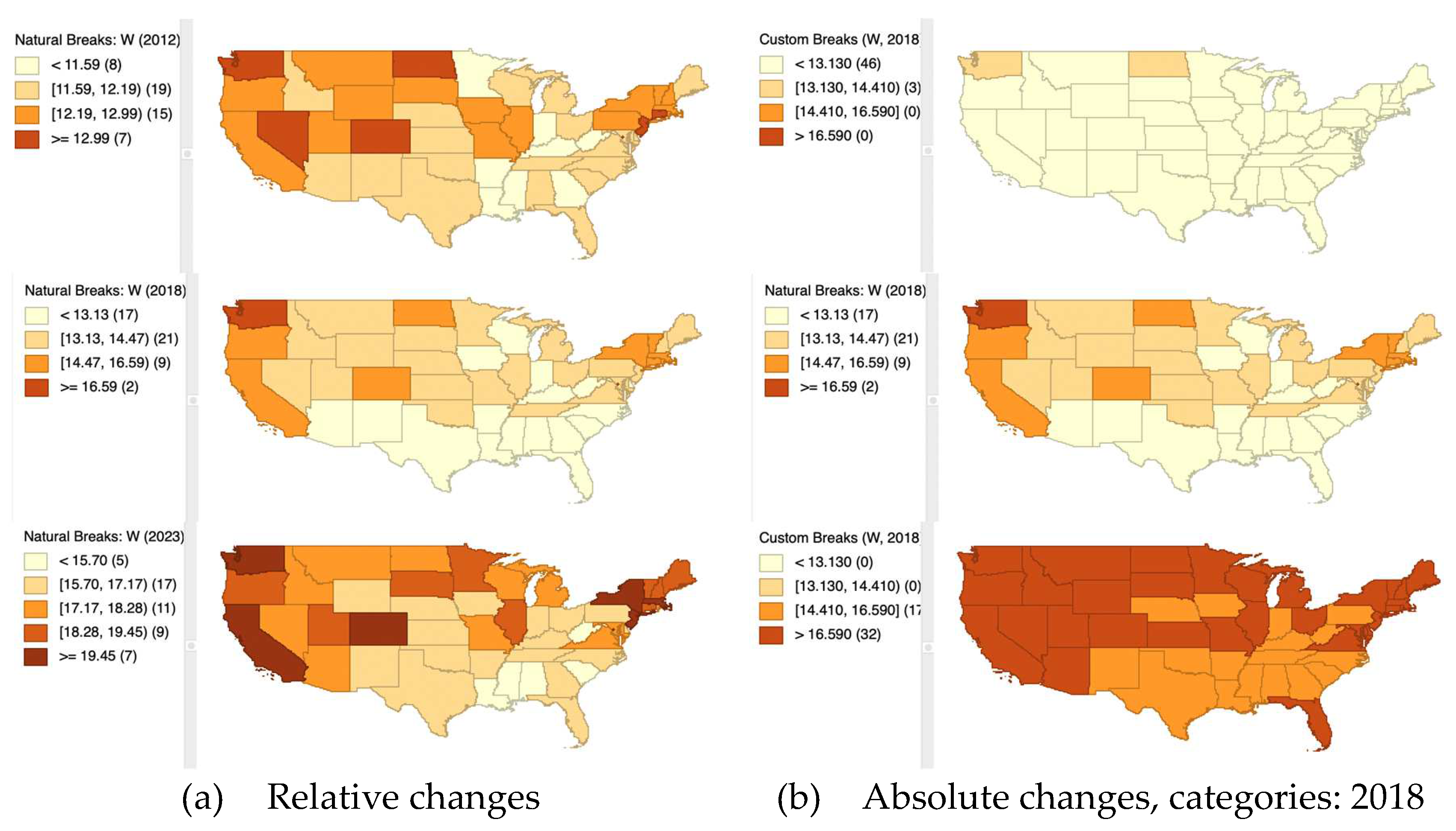

2.1.3. Thematic Maps

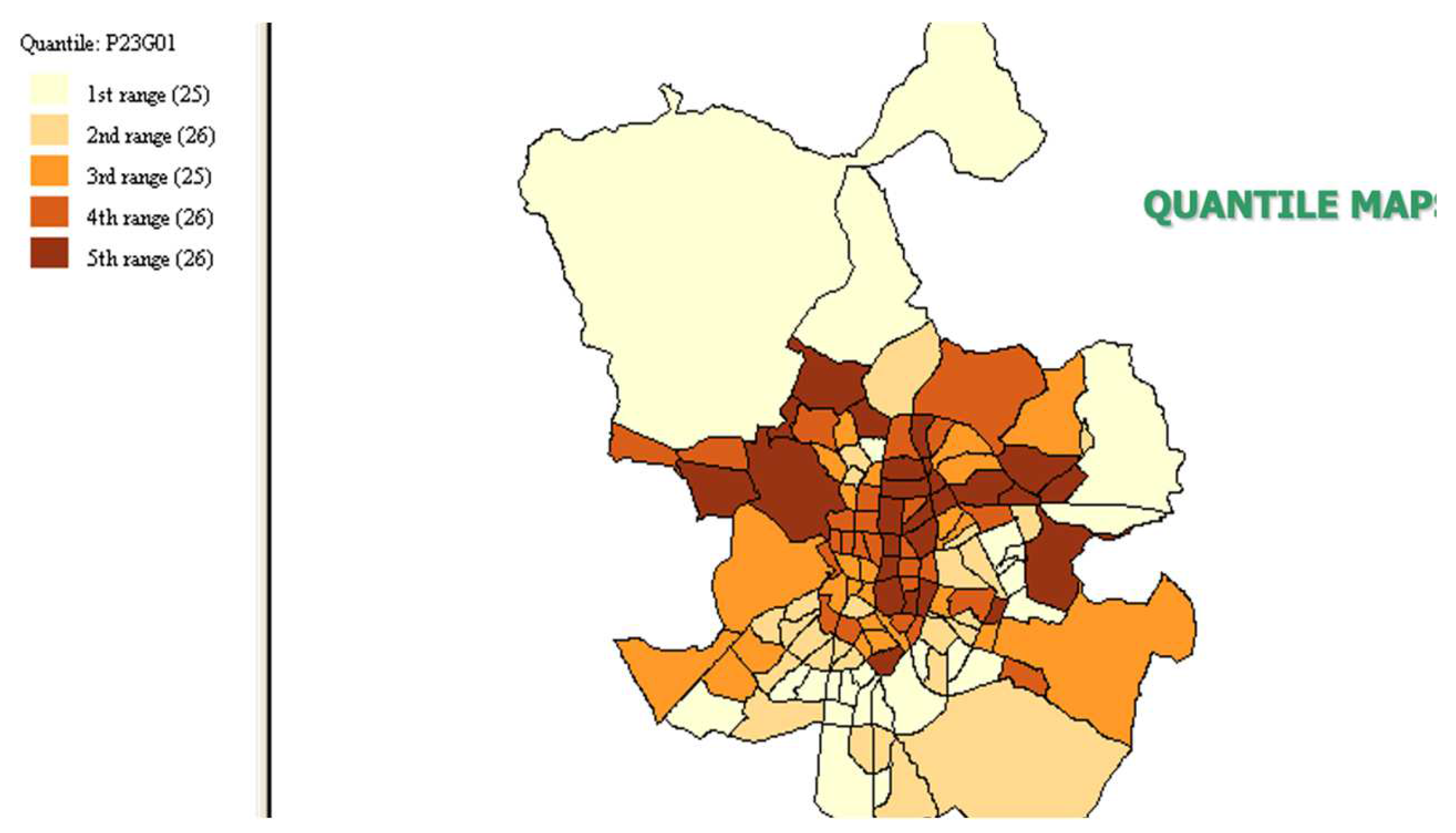

- (1)

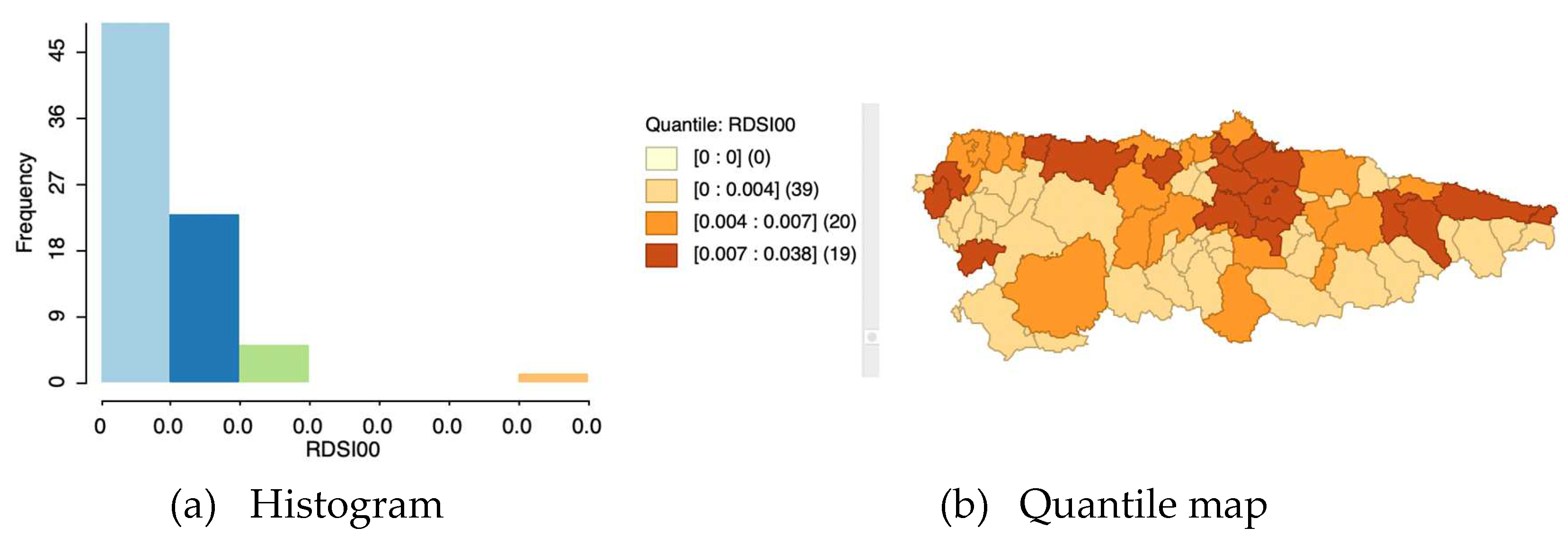

- Quantile map

- (2)

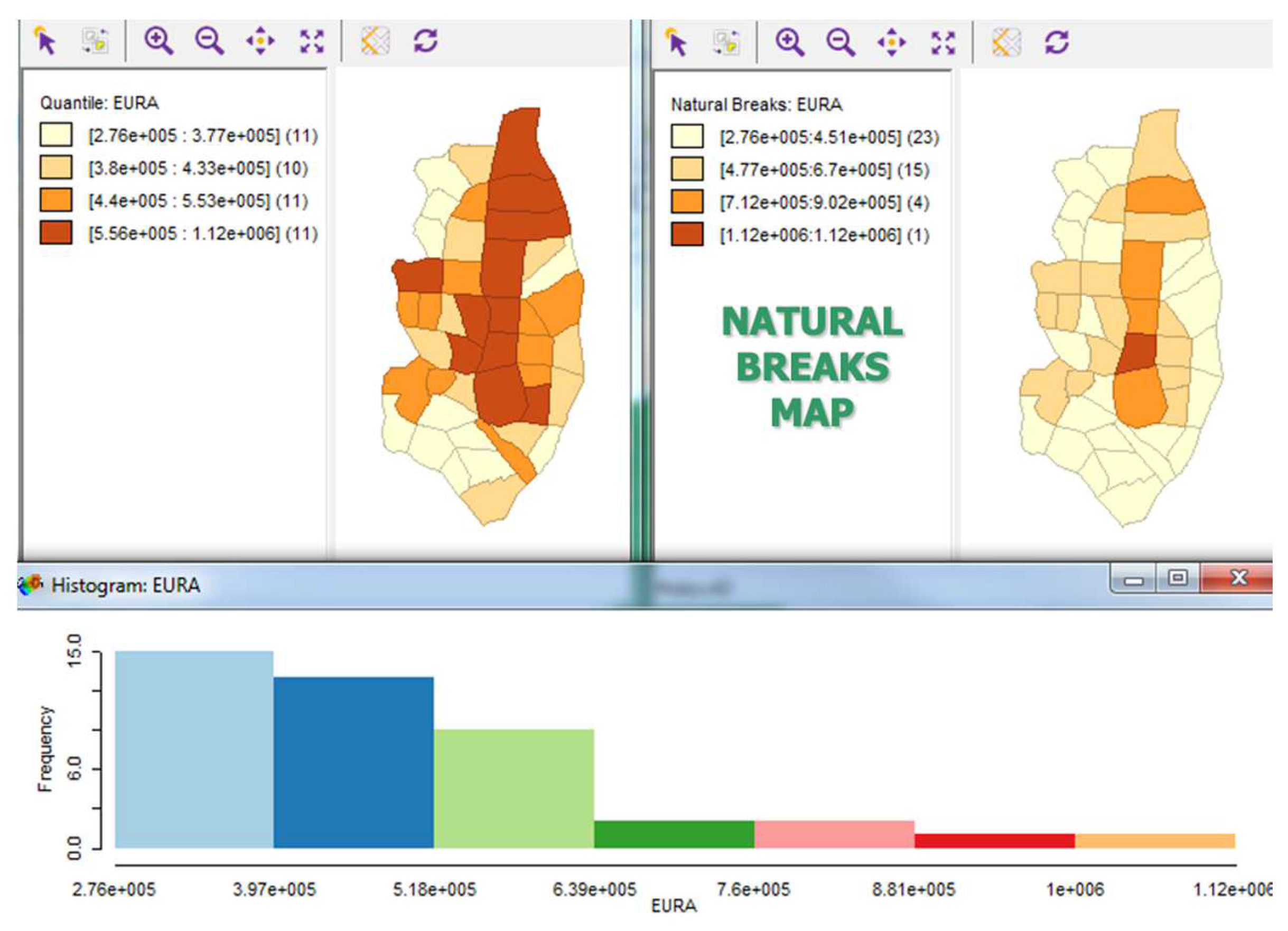

- Natural breaks map

- (3)

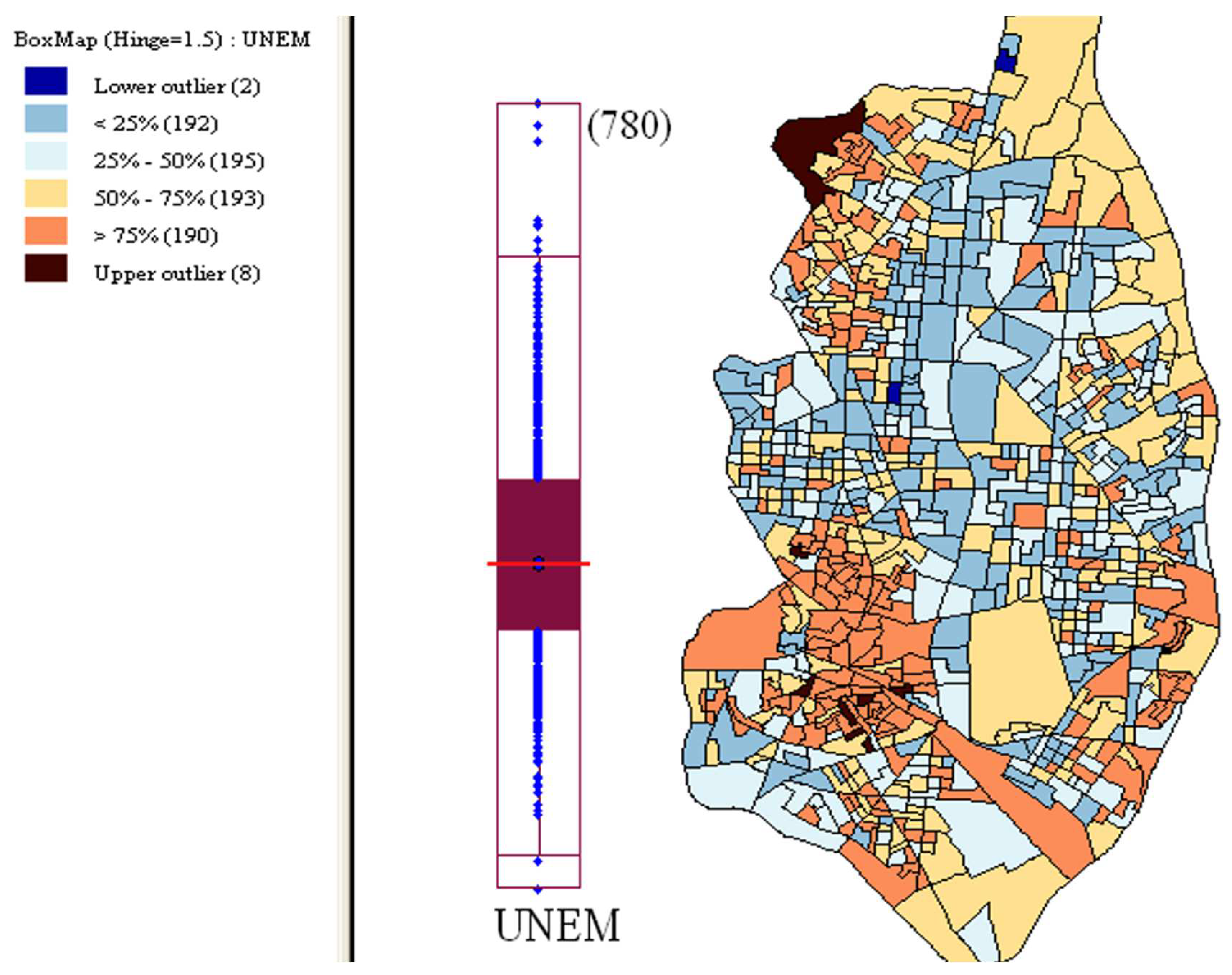

- Box map

2.2. For Discrete Variables

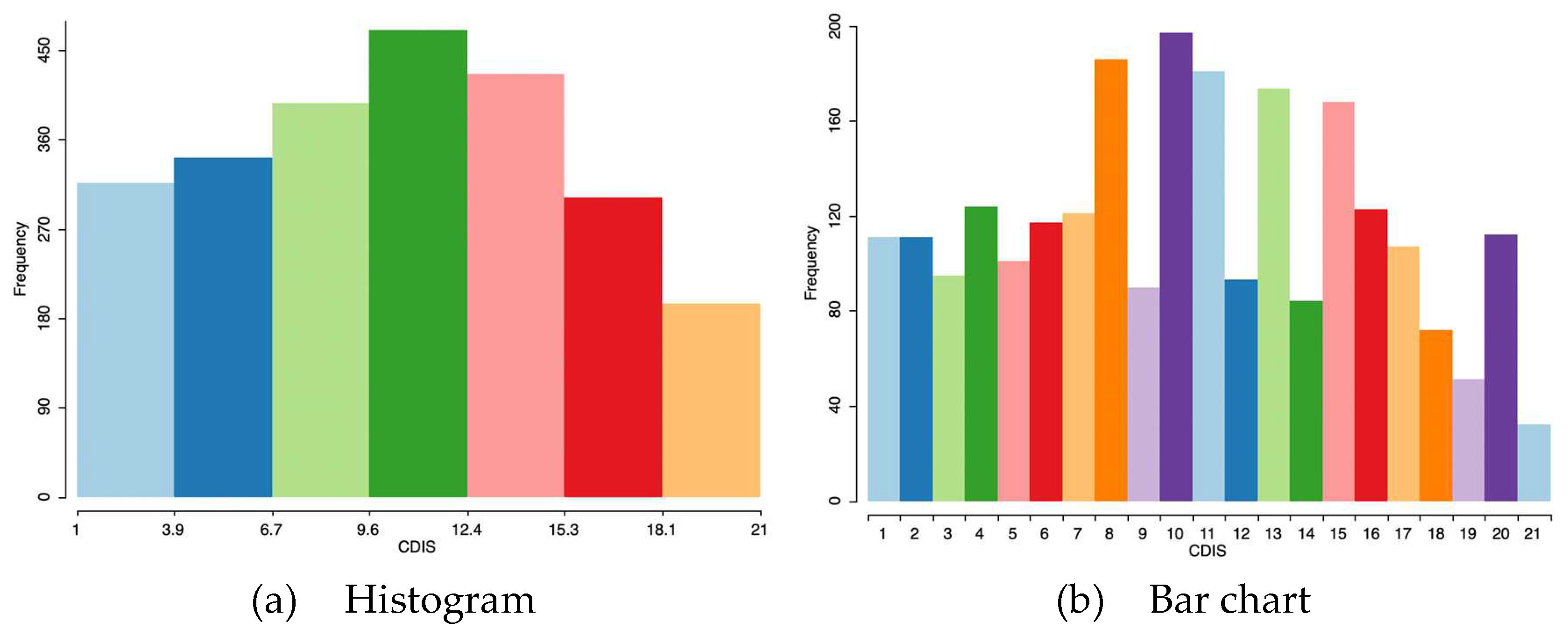

2.2.1. Bar Chart

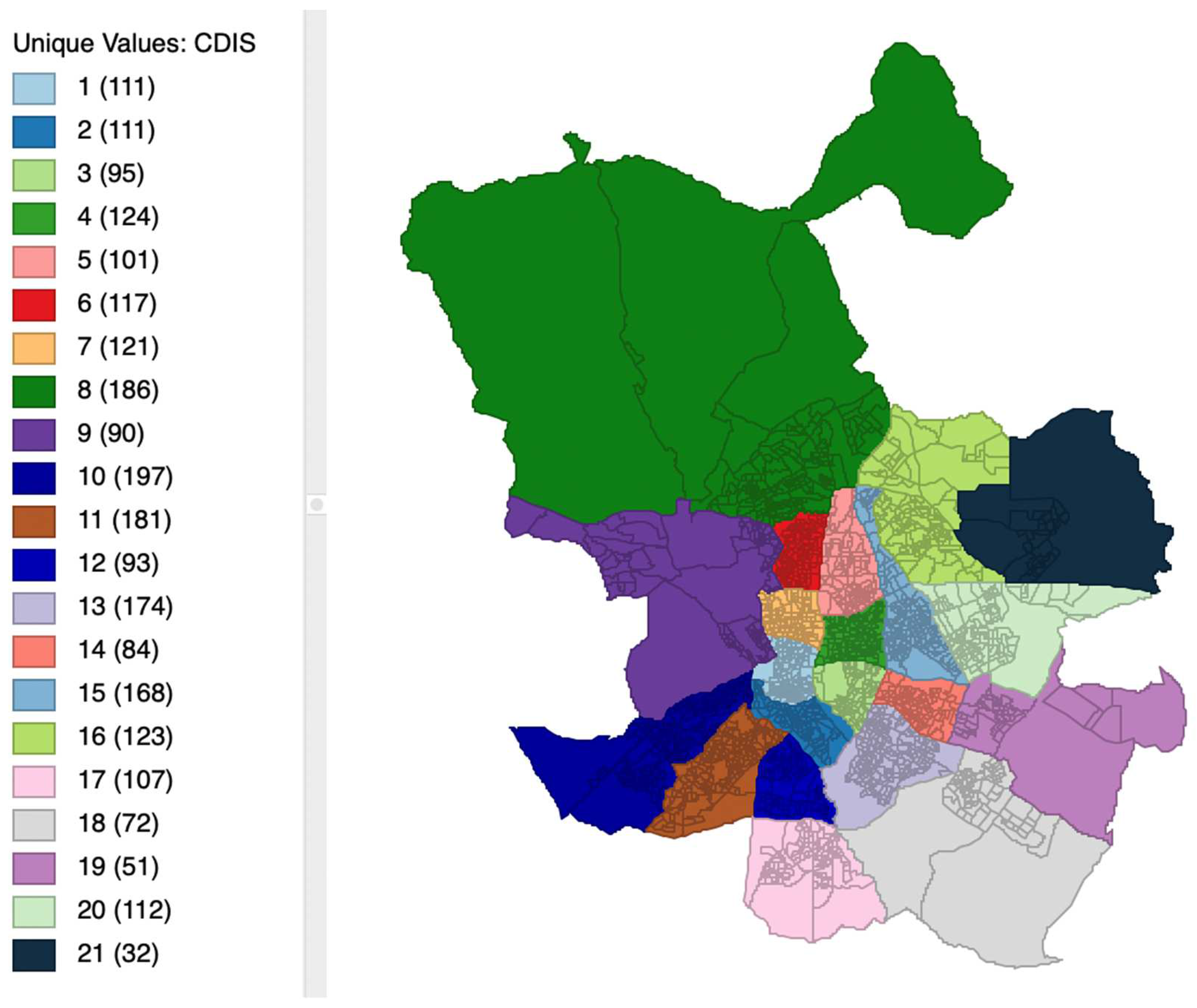

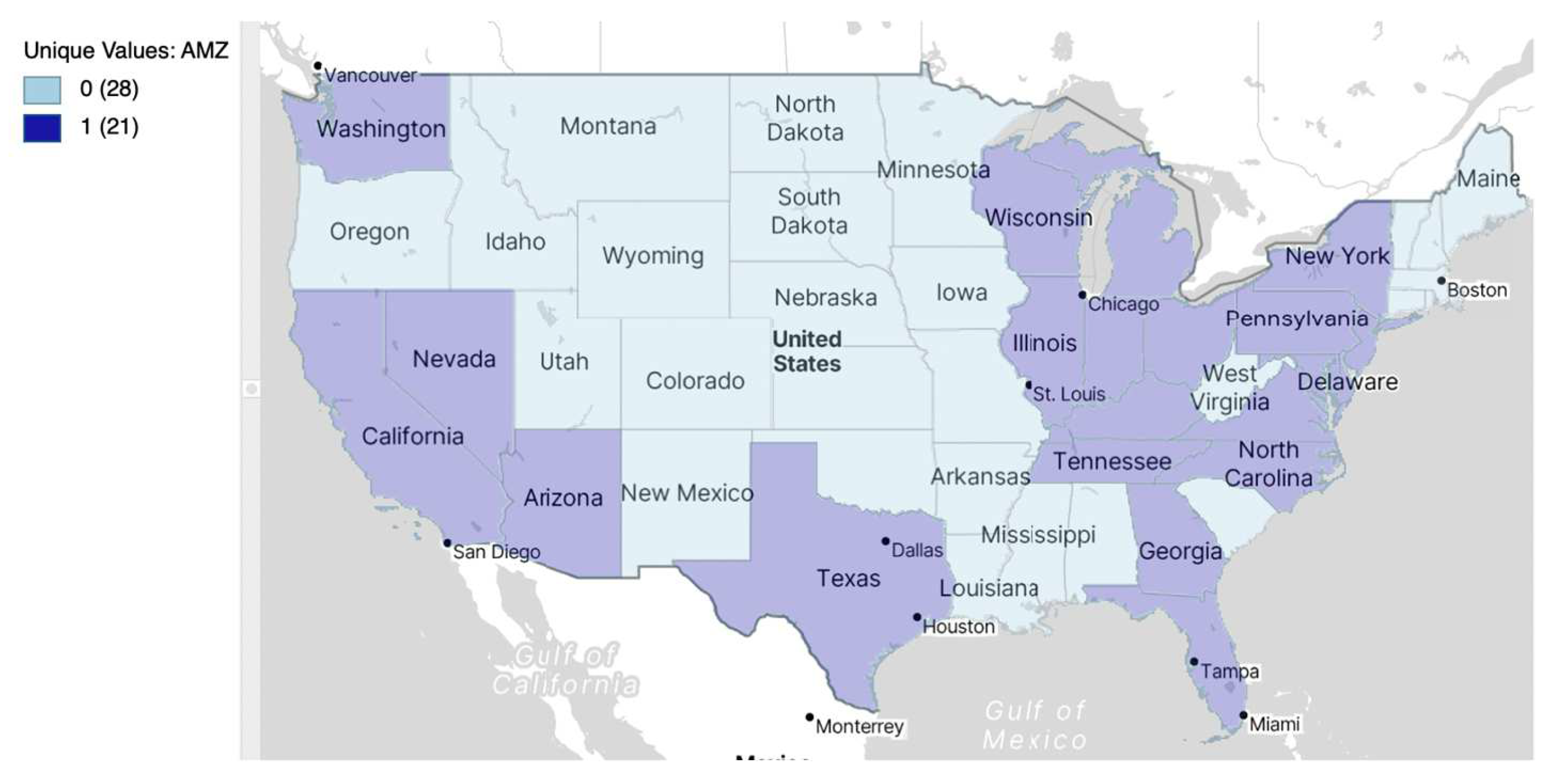

2.2.2. Unique Values Map

2.3. Map Classification, Legends and Colors

- (a)

- For maps where the values represented are ordered and follow a single direction, from low to high, a sequential legend is appropriate. Such a legend typically uses a single tone and associates higher categories with increasingly darker values.

- (b)

- In contrast, for the maps representing the extreme values of a variable, the focus should be on the central tendency (mean or median) and how observations sort themselves away from the center, either in downward or upward direction. An appropriate legend for this situation is a diverging legend, which emphasizes the extremes in either direction. It uses two different tones, one for the downward direction (typically blue) and one for the upward direction (typically red or brown).

- (c)

- Finally, for categorical data a qualitative legend is appropriate; that is, no order should be implied (no high or low values) and the legend should suggest the equivalence of categories.

3. Basic Multivariate ESDA

3.1. For Continuous Variables

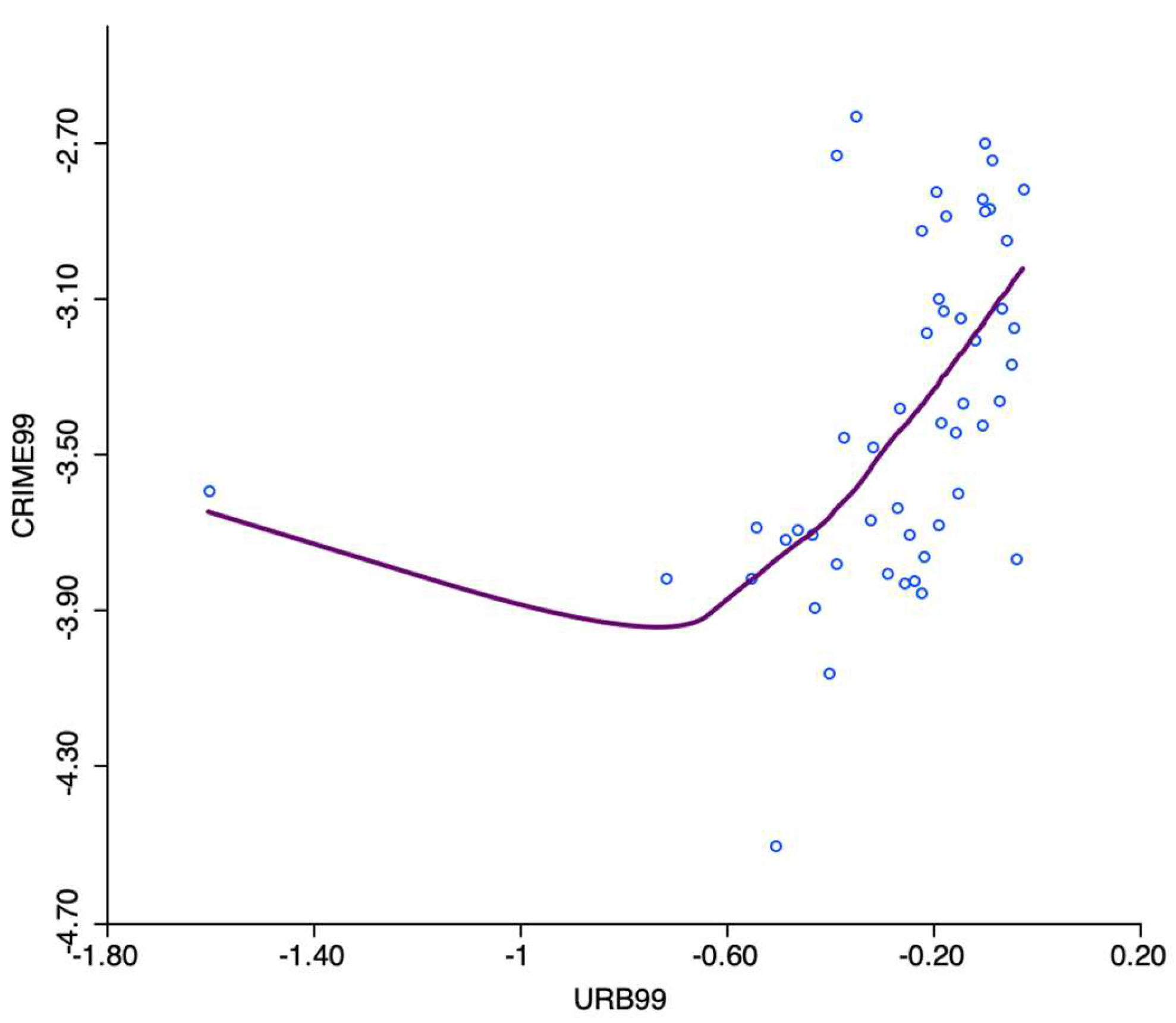

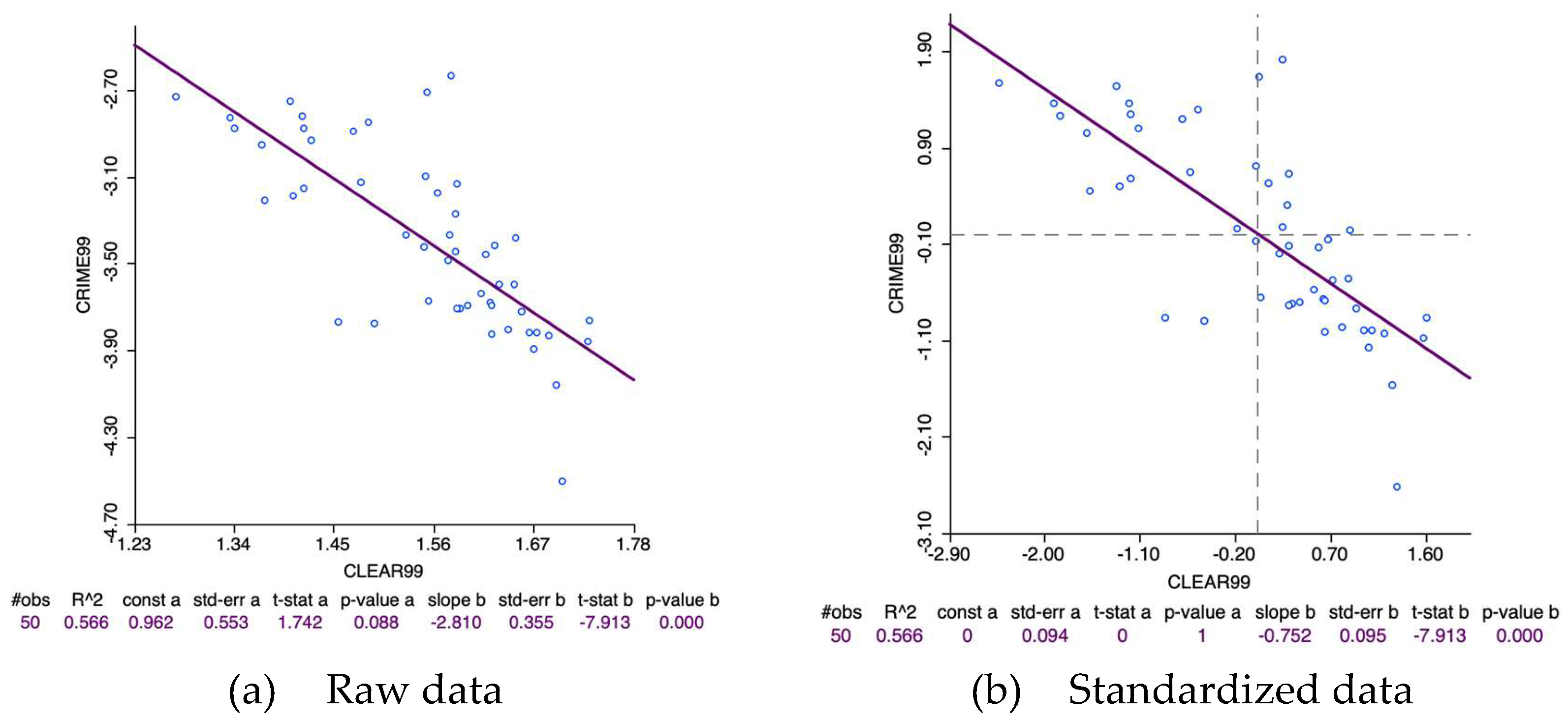

3.1.1. Scatter Plot

- (1)

- Non-linear relationships

- -

- The bandwidth is the proportion of points in the plot that influence smoothing at each value, so as larger values give more smoothness. For example, the default bandwidth of 0.20 implies that for each local fit (centered on a value for X), about one fifth of the range of X-values is considered.

- -

- Iterations: are the number of “robustifying” iterations which should be performed. Using smaller values will speed up the smoothing.

- -

- Delta factor: Small values of delta speed up computation because local polynomial fit is only computed for a small amount of data at each data point, filling in the fitted values for the skipped points with linear interpolation.

- (2)

- Standardization of the x, y variables

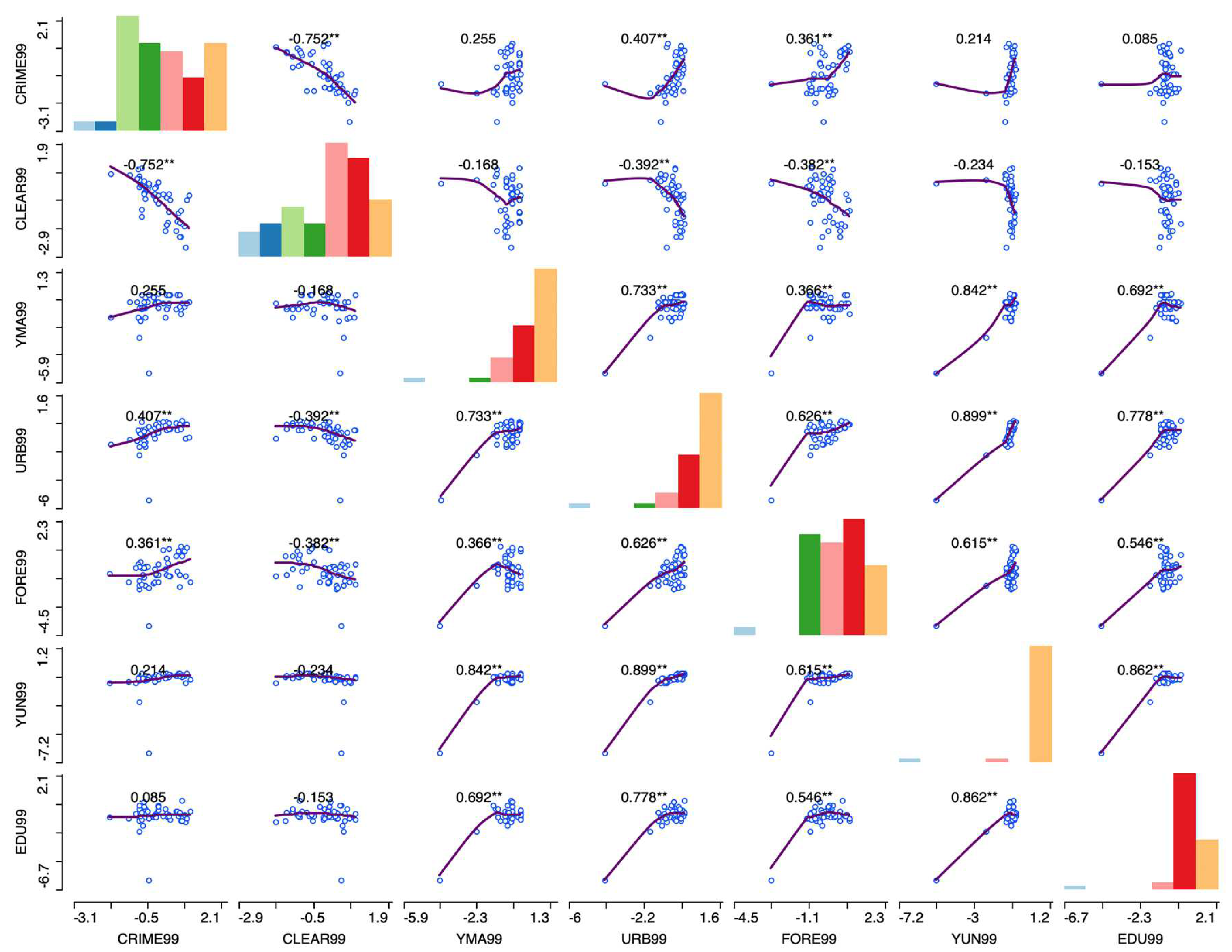

3.1.2. Scatter Plot Matrix

3.1.3. Parallel Coordinate Plot

3.2. For Discrete Data: Co-Location Map

3.3. For Rates or Proportions

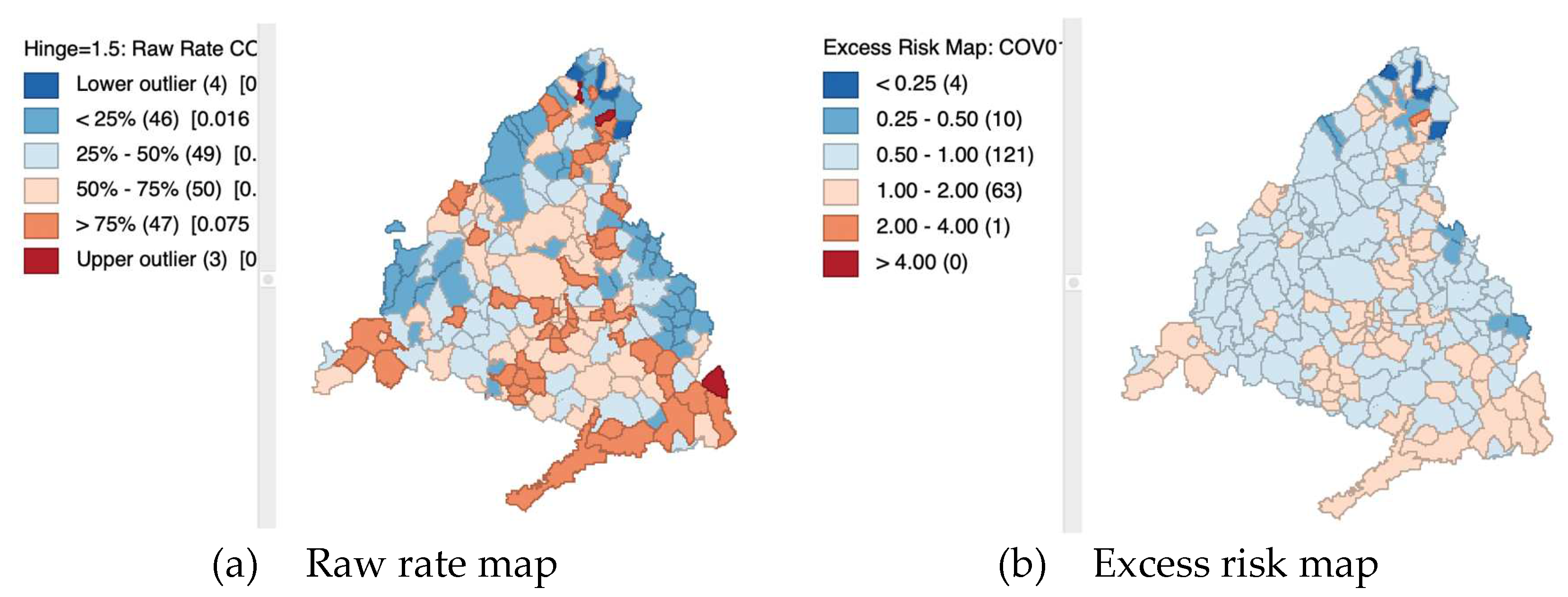

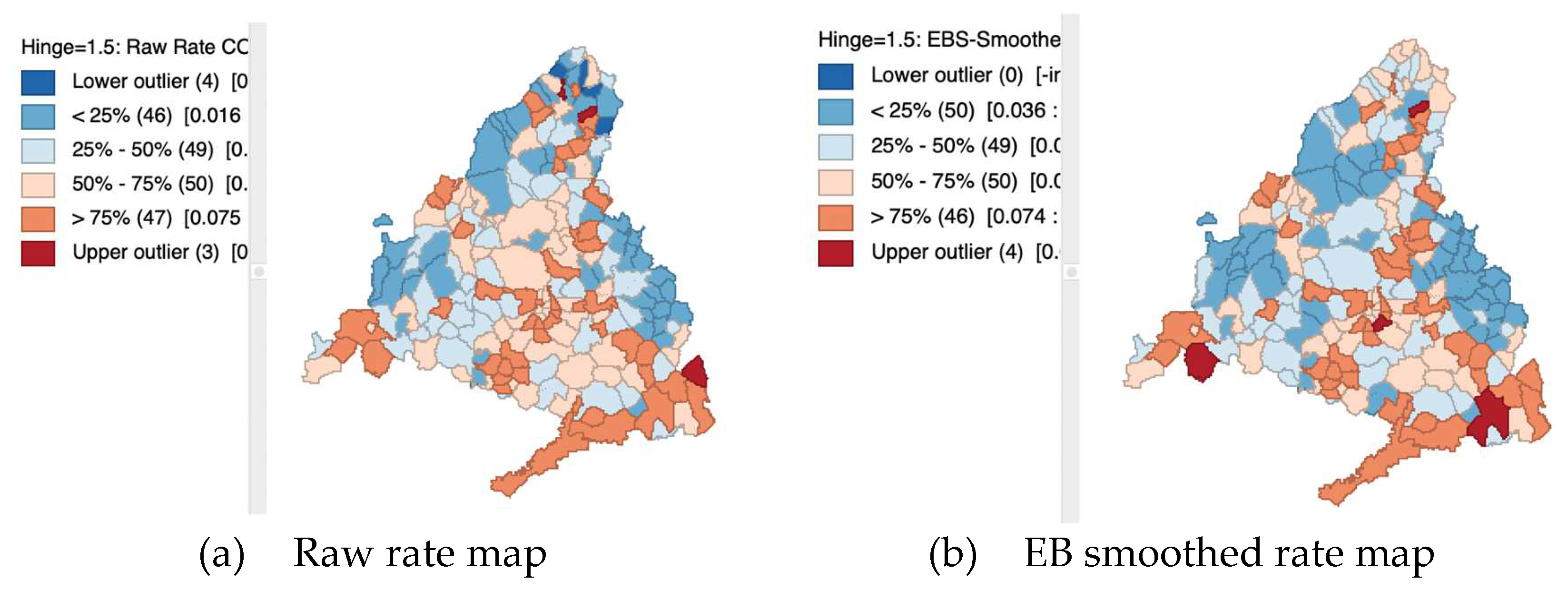

3.3.1. Raw Rate Map

3.3.2. Relative Risk or Rate

3.3.3. Excess Risk Map

3.3.4. Empirical Bayes Smoothed Rate Map

3.4. For Space-Time Data

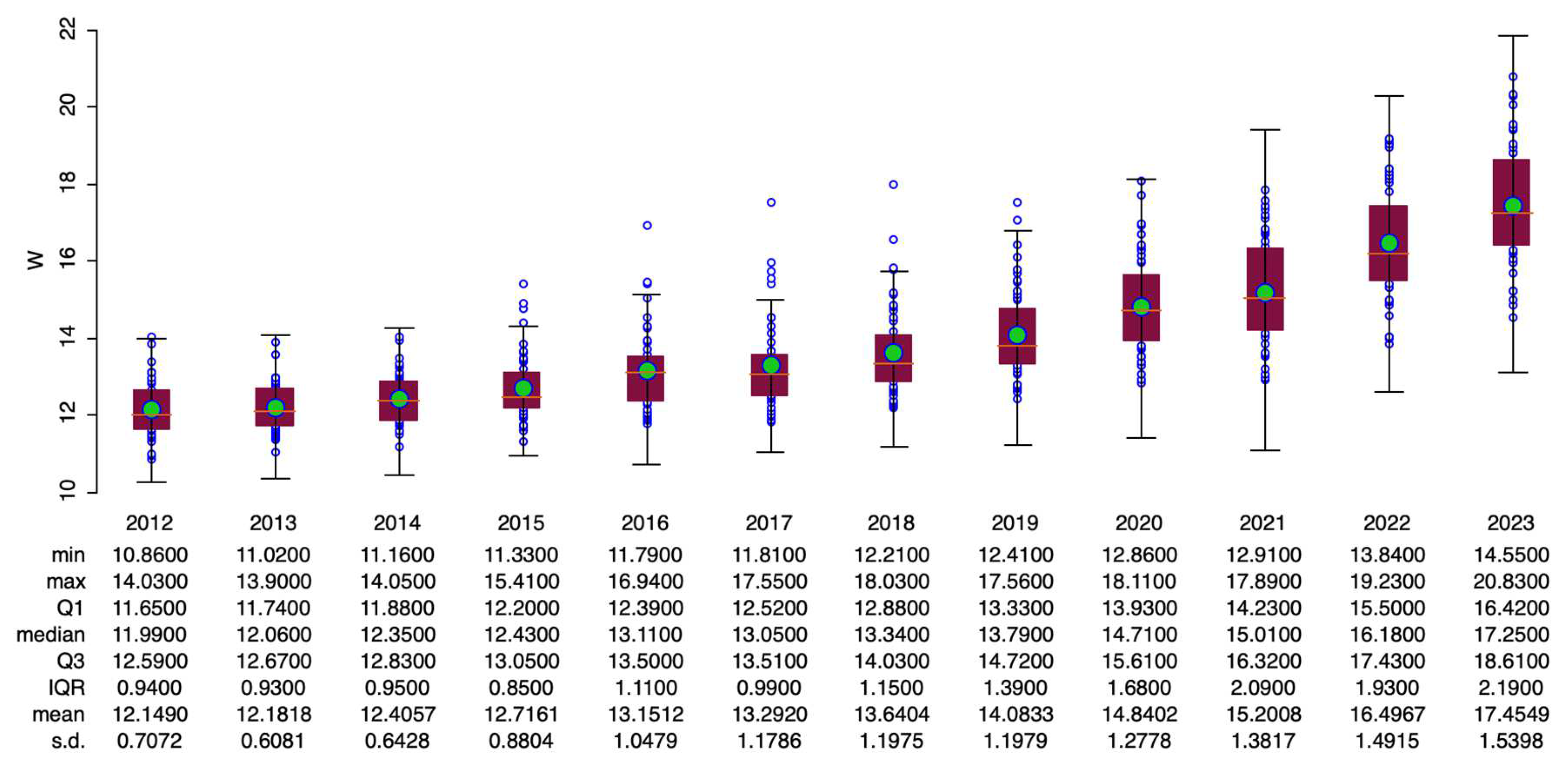

3.4.1. Space-Time Box Plot

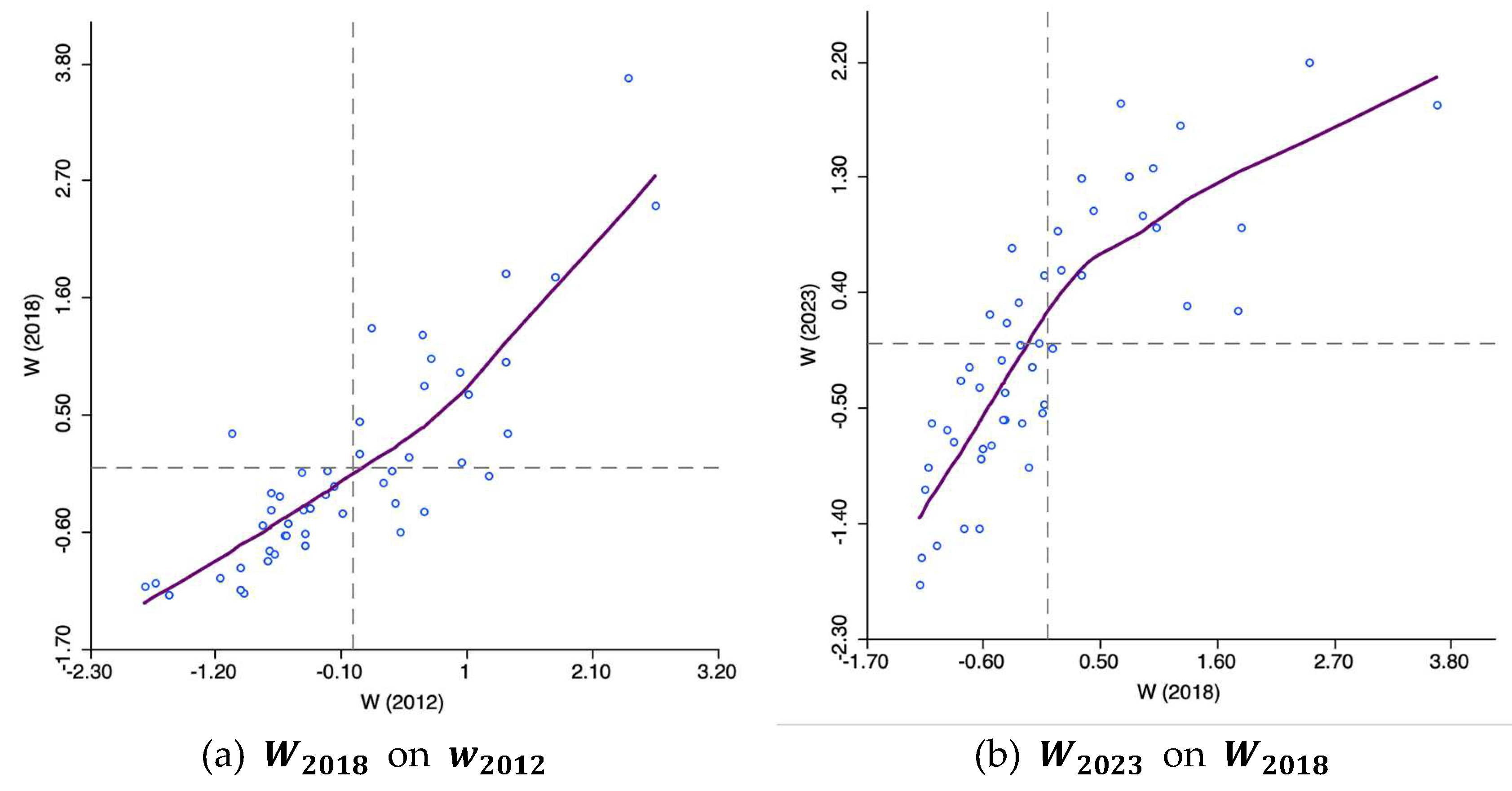

3.4.2. Time-Wise Autoregressive Scatter Plot

3.4.3. Space-Time Choropleth Map

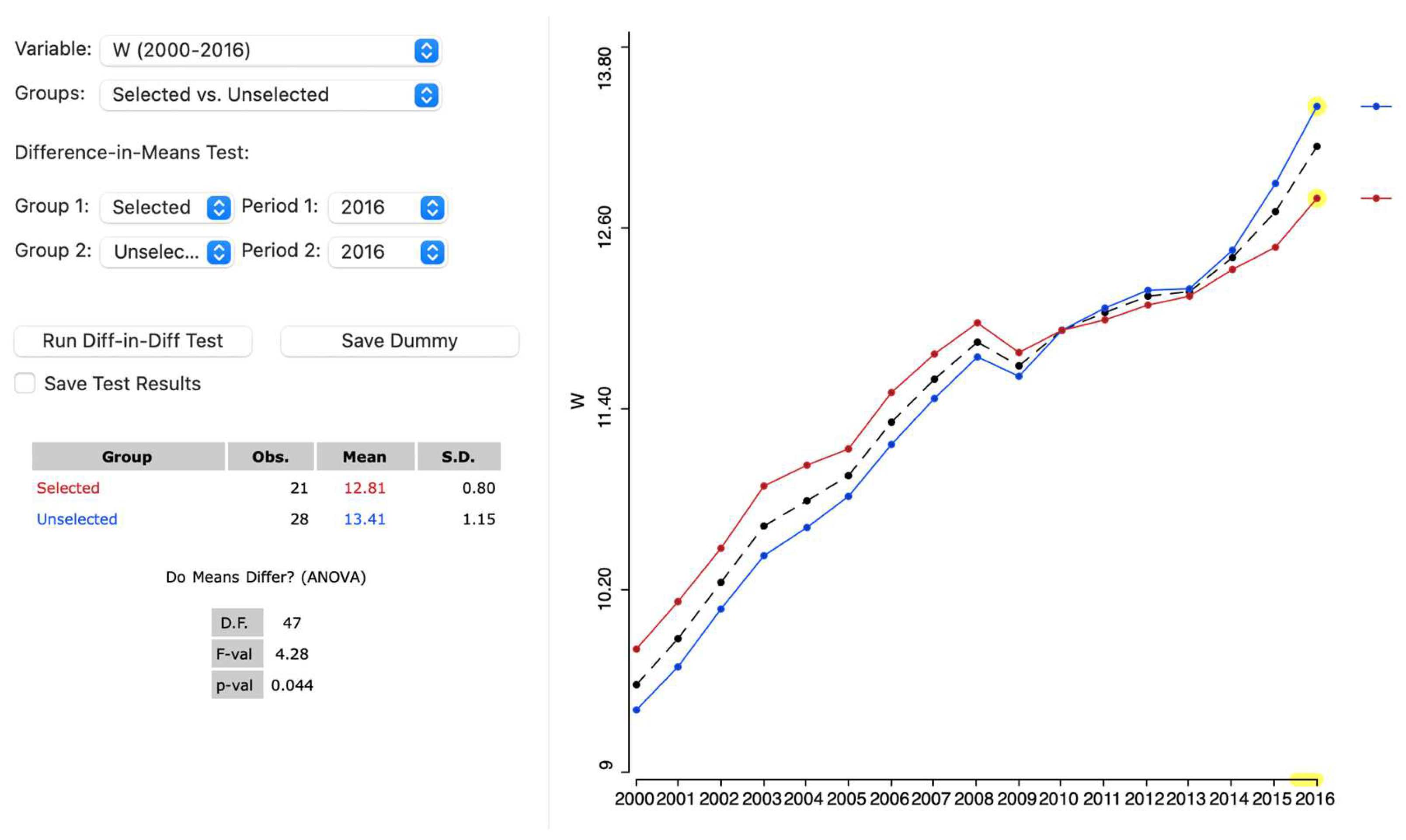

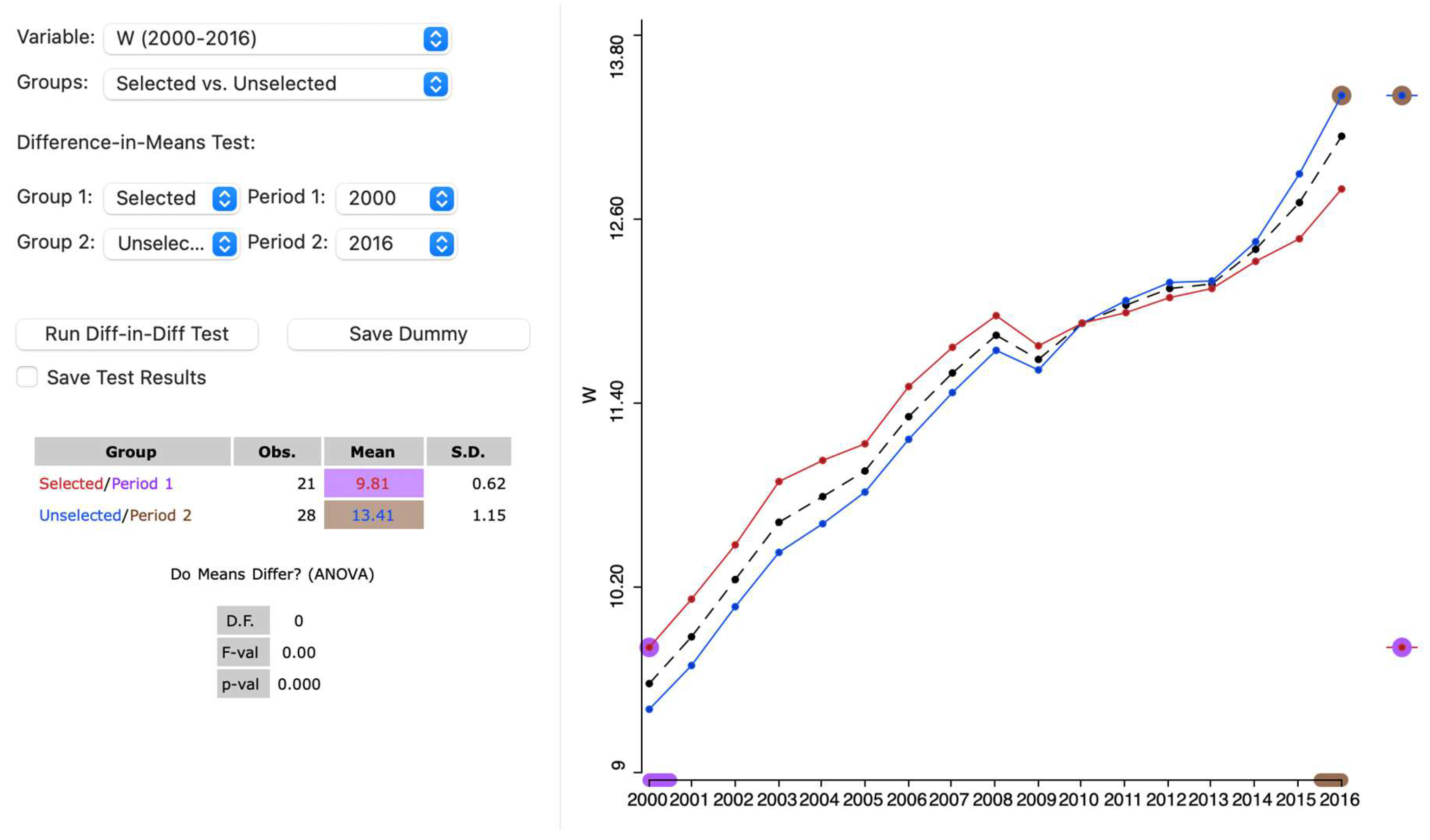

3.4.4. Treatment Effect Analysis: Averages Chart

- (1)

- Difference-in-Means test

- (2)

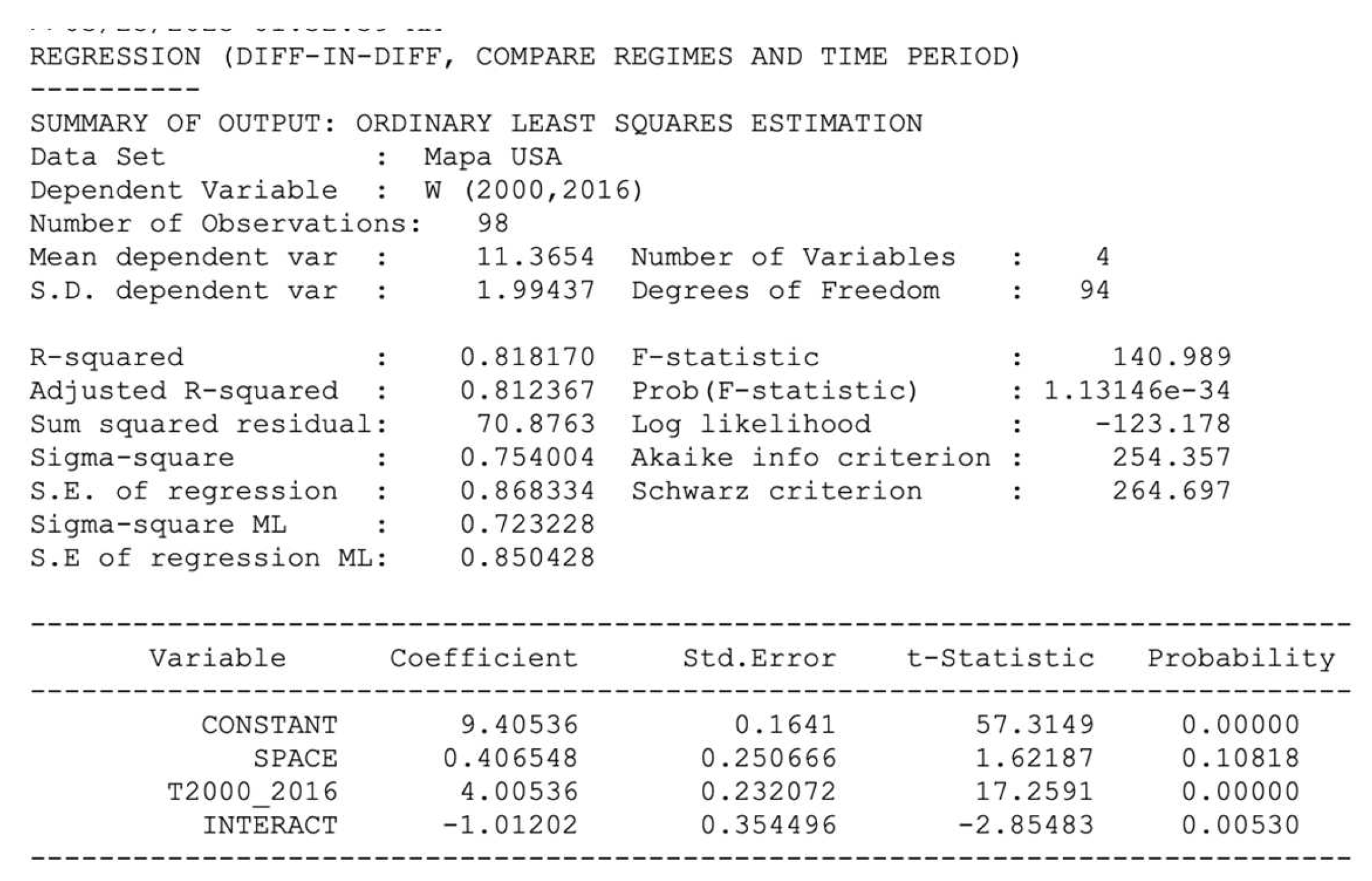

- Difference-in-Difference test

4. Conclusions

Appendix A. Mapping Smoothed Rates (See Anselin 2023)

- (1)

- Variance instability of rates

- (2)

- Borrowing strength

- (3)

- Bayes Law

References

- Angrist, J, Pischke, J-S (2015) Mastering Metrics, the Path from Cause to Effect. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Anselin, L. (2023) An Introduction to Spatial Data Science with GeoDa. Volume 1: Exploring Spatial Data. https://lanselin.github.

- Anselin, L, Rey, S.J. (2014) Modern Spatial Econometrics in Practice, a Guide to Geoda, Geodaspace and Pysal. Chicago, IL: GeoDa Press.

- Anselin, L, Lozano-Gracia, N, Koschinky J (2006) Rate Transformations and Smoothing. Technical Report. Urbana, IL: Spatial Analysis Laboratory, Department of Geography, University of Illinois.

- Bivand, R.S. (2010) Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis. In Fischer, M.M., Getis, A., Eds.; Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg; pp. 219–254 ISBN 978-3-642-03647-7.

- Brewer, C.A. Spectral Schemes: Controversial Color Use on Maps. Cartography and Geographic Information Systems 1997, 49, 280–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasco, C. , Vallone, A. (2023). Introduction to Cross-Section Spatial Econometric Models with Applications in R. [CrossRef]

- Inselberg, A. (1985) The Plane with Parallel Coordinates. Visual Computer.

- James, W, Stein, C (1961) Estimation with Quadratic Loss. Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability 1: 361–79.

- Jenks, G. F. (1977) Optimal Data Classification for Choropleth Maps. Occasional. Paper no. 2. Lawrence, KS: Department of Geography, University of Kansas.

- Lefebvre, H. (1992) The Production of Space; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford (UK) & Cambridge (USA), 1992; ISBN 978-0-631-18177-4. [Google Scholar]

- Loader, C. (2004) Smoothing: Local Regression Techniques. In Gentle, J.E., Härdle, W., Mori, Y. (eds.) Handbook of Computational Statistics: Concepts and Methods, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, pp. 539–63.

- Scribbr (2025) An Introduction to t Tests | Definitions, Formula and Examples. Accessed in 25. https://tinyurl. 20 March.

- Tobler, W.R. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Economic Geography 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J. (1977) Exploratory Data Analysis. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Wikipedia (2025a) Gamma distribution. Accessed in 25. https://tinyurl. 20 March.

- Wikipedia (2025b) Bar chart. Accessed in 25. https://tinyurl. 20 March.

- Wikipedia (2025c) Bayesian inference. Accessed in 25. https://tinyurl. 20 March.

| Dependent variable | ESDA tool | Econometric model |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Histogram Box plot Quantile map Natural break map Box map |

Spatial linear regression models Spatial Expansion models Geographically Weighted Regres. Trend surface models Spatial ridge and lasso models Spatial Partial Least Squares |

| Discrete | Bar chart Unique values |

Spatial count data models Binary Spatial models Spatial logit models Spatial probit models |

| Rates | Raw rate map Excess risk map Empirical Bayes smoothed rate map |

Spatial beta regression models Spatial fractional response mod. Spatial logit, probit, tobit mod. |

| Space-Time | Box plot over time Scatter plot with time lagged vars. Thematic map over time Difference in means Difference-in-difference |

Spatiotemporal models Spatial panel data models Difference-in-difference models |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).