1. Introduction

With a glorious history of more than one hundred and seventy years, internal combustion engines (ICEs) contribute to mobility development for people and goods and to energy generation in different fields of application. Currently, it is quite difficult to make a reliable prediction about their future, as strong competitors are available, such as electric propulsion systems based on batteries or fuel cells. In most of the countries, policies for decarbonization generally aim at their replacement to fulfil targets for the reduction of Green House Gas (GHG) emissions. From a European perspective, Fit for 55 package of the European Union [

1] and the IMO strategies for the decarbonization of the maritime sector [

2] can be mentioned among the most well-known acts.

On the other hand, considering their advantages and extended use, the investments required for their substitution, and the difficulties in replacing them for applications such as long hauling heavy-duty vehicles and deep-sea shipping [

3], development of ICEs is still of the largest relevance [

4,

5,

6], while their life can be expected not to come to an end in a short period of time, even in the private mobility sector [

7].

Together with electro-fuels, biofuels may represent an option as an alternative energy source [

8,

9], to reduce the use of fossil fuels, to recycle waste materials, and to create additional jobs and incomes in the rural sector. Furthermore, alternative fuels are an unavoidable measure to tackle the problem of legacy fleet and the corresponding CO

2 emissions.

As far as the decrease of CO

2/GHG emissions is concerned, the reduction strongly depends on the primary feedstock and the production process. As reported in Renewable Energy Directive II [

10] and III [

11], biodiesel obtained from waste cooking oil allows for GHG emissions saving around 86%, representing the largest one among the biodiesel types listed in these Directives. Moreover, waste cooking oil methyl esters (WCOME) is classified as a 2

nd or 3

rd generation biofuel, as no land use change is required [

12].

Methodology described in RED II and III is based on a Well-to-Wheels (or Well-to-Wake) approach. Within this analysis, contributions to GHG emissions are related to the extraction or cultivation of raw materials, delivery of the primary feedstock to the production sites, their processing, transport and distribution of the fuel, and its end-use. The same approach is followed by the Regulation Fuel EU Maritime [

13]. Therefore, all these legislation acts give rules, set procedures for GHG emissions evaluation, and provide numerical estimations of GHG emissions potential reduction for alternative fuels following a comprehensive approach. An example of the application of WtW approach in the maritime sector is presented in [

14].

But GHG emissions are only one side of the problem. For diesel engines, the effects of biofuels on efficiency and emissions must be considered for an overall evaluation of benefits and disadvantages. Due to the large number of papers presenting tests on a wide range of biofuels, selecting engines of different characteristics and applying several approaches, the analysis of review papers may allow to define a general behavior of biofuels, outlining their influence on energy and environmental parameters. As far as brake thermal efficiency (bte) is concerned, while a consistent conclusion was not obtained from the investigations analyzed in [

15], a general agreement for enhanced values was shown in [

16]. In a recent paper [

17], bte does not change when replacing diesel with a B30 blend based on waste cooking oil, but in this case the tested engine was a single cylinder naturally aspirated unit with a mechanical fuel pump, confirming that outcomes are strongly dependent on engine type and experimental operating conditions. In the same paper, other results adding TiO

2 nanoparticles (a common approach in recent studies) show some benefits on bte for high levels of engine rotational speed.

For PM emission, significant reductions are presented in [

15,

18,

19], because of biodiesel oxygen content and lower sulfur level. A negative influence on nanoparticles is outlined in [

16].

Effects on NO

X emissions are still an open issue, because of controversial outcomes reported in different review papers [

15,

16,

18,

20,

21]. Even if most of the investigations shows an increase of NO

X emissions (with percentages of selected papers presenting this conclusion ranging from 48.5% [

21] to 85% [

15]), the number of studies showing emission decreases is not negligible. Among the main parameters affecting the results, biodiesel feedstock, engine characteristics (displacement, air management system, fuel injection systems, etc.), tested operating conditions, biodiesel content, and control strategies of engine sub-systems can be mentioned. For NO

X emission, counteracting effects of the considered variables are also detected, therefore non-monotonically influence of biodiesel on raw NO

X emission may be identified, as presented in [

22].

Considering investigations on WCOME, basic characteristics related to combustion, physical, and chemical properties are presented in [

23,

24], comparing fuels obtained from different feedstock or testing blends and neat biodiesel. In [

25], effects of diesel, WCOME and two types of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) on high pressure pumps are analyzed.

Focusing on investigations at engine test bench, available literature covers a wide range of engines for different applications (marine [

26], stationary [

27], agricultural [

28]) with single [

28,

29] or multi-cylinder [

26,

27,

30] layout. In these papers, several blends are considered (ranging from B10 to B50), while fuel injection is based on electronically controlled common rail systems [

26,

30] or mechanical pumps [

27,

28]. Despite this variety, a general agreement is observed for emissions, with increased levels of nitrogen oxides and reduction in HC and soot. The same outcome is shown in [

31], when fueling an urban bus with B10 and B20.

Taking into account the current knowledge on WCOME and the main features of available literature, several goals were identified for the present investigation:

give a contribution to the assessment of WCOME influence on NOX emission considering an engine fitted with state-of-the-art sub-systems (HP EGR circuit, fuel injection system with electronic control, turbocharging system including a variable nozzle turbine).

Analyze biodiesel application considering blends with high content or even neat WCOME, whose behavior is less available in literature.

Verify if a proper management of selected control variables, following the experience gained in previous investigations [

32,

33], may compensate for the negative effects of WCOME or to further enhance its advantages.

Propose integrated control strategies for EGR rate and rail pressure, to improve benefits offered by biodiesel, matching a proper management of EGR circuit to compensate the increase of NOX emission, a higher rail pressure values to limit soot emission, and blends with high WCOME content or neat biodiesel to minimize CO2 emission on a WtW base.

Propose integrated control strategies for EGR rate and rail pressure, to improve benefits offered by biodiesel, matching a proper management of EGR circuit to compensate the increase of NOX emission, a higher rail pressure values to limit soot emission, and blends with high WCOME content or neat biodiesel to minimize CO2 emission on a WtW base.

In the paper, applied methodologies are presented in

Section 2. The main characteristics of engine and measuring system are firstly described. Then, details on indicating technique and related combustion parameters are given. Finally, the main characteristics of the reference diesel oil, biodiesel, and related blends are analyzed, together with the experimental program. In

Section 3, the most important results are presented and discussed, referring to operating, energy, environmental, and combustion parameters. The effects of EGR rate and rail pressure control are analyzed, identifying integrated control strategies allowing for overall benefits when replacing diesel oil with blends including high biodiesel content or neat renewable fuel.

2. Materials and Methods

This section summarizes the main aspects related to engine, instruments, assessment of heat release and combustion parameters, engine management system, tested fuels/blends, and investigation program. The goal is to provide information to allow the comparison between this investigation and other studies on biodiesel application.

2.1. Tested Engine

The main characteristics of the tested engine are listed in

Table 1. The unit is an automotive turbocharged engine, with a downsized displacement, fitted with subsystems still representing state-of-the-art technologies. The Diesel Particulate Filter was not installed during the test, to simplify engine operations. Measurements referred to raw emissions, to identify the influence of blends and neat biodiesel on the engine output, excluding variations related to after-treatment devices.

2.2. Instruments and Measuring System

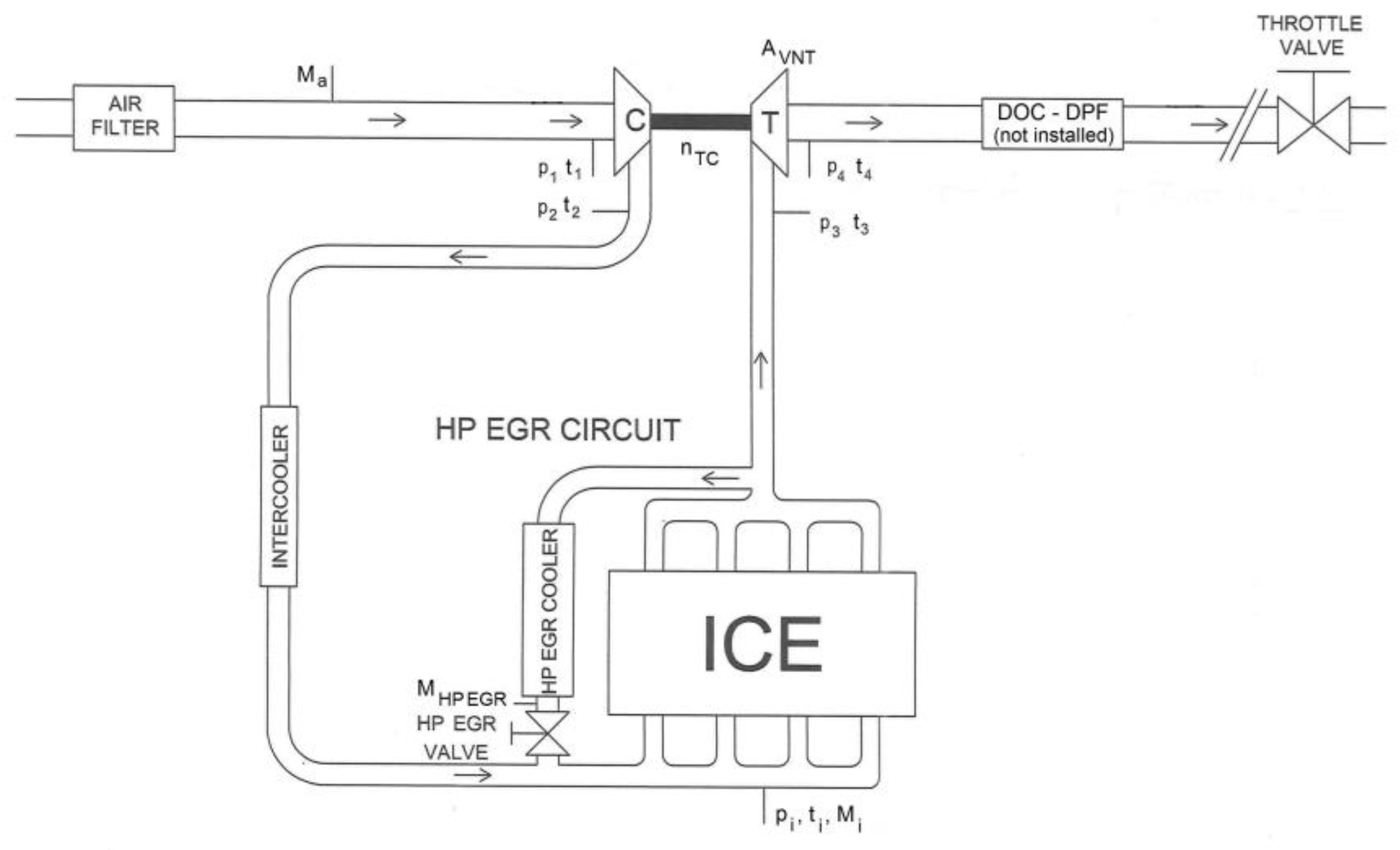

Figure 1 shows the scheme of the experimental test bench, based on a steady-state eddy current dynamometer, presenting the relevant nomenclature and the location of the transducers. Instrumentation aims at the acquisition of a wide set of quantities, according to the list of

Table 2. Temperature and pressure values were measured in different sections of intake and exhaust circuits, using platinum resistance thermometers, K-type thermocouples, and strain gauge transducers. Temperature levels of coolant, lubricant oil and intake charge were managed to minimize their influence on engine performance and to obtain a proper range of intercooler efficiency, controlling thermostatic circuits and water flow rate.

Nitrogen oxide concentration was measured by an exhaust gas analyzer. Exhaust smoke, expressed in Filter Smoke Number (FSN), was measured by a variable sampling smoke meter. Soot concentration (expressed in [mg/m3]) was calculated as a function of exhaust smoke according to a correlation provided by the instrument manufacturer. For specific emissions evaluation, density of gases was assessed measuring pressure and temperature in the sampling sections of the NOX analyzer and the smoke meter. Volumetric flow rates of exhaust gases were then calculated, allowing for the assessment of NOX and soot mass flow rates, then divided by the effective power to give the relevant specific emission (bsNOX and bsS).

Low frequency measurements in steady-state conditions were made by an automatic data acquisition system, based on virtual instruments developed in Labview®. Data was processed in Excel®, calculating statistical parameters of measured quantities (average, standard deviation, coefficient of variation) and the main engine parameters.

As far as uncertainties are concerned, the relative uncertainty depends on the measured level of the considered parameter. For fuel consumption, the accuracy depends on the mass of fuel injected into the engine during the measurement time interval (10 s). The overall uncertainties were evaluated according to [

34]. They change according to operating conditions, as shown in

Table 3, presenting the maximum relative uncertainties for brake specific fuel consumption (bsfc), NO

X and soot emissions. Experimental points are identified with the corresponding values of engine rotational speed n and brake mean effective pressure (bmep). Higher uncertainties are apparent for soot values, due to the reduced accuracy of the smoke meter compared with the other instruments (

Table 2).

In the case of maximum in-cylinder pressure levels, the experimental procedure was based on the acquisition of 60 cycles for each tested mode. Therefore, the standard deviation of this parameter was evaluated and then compared to the uncertainty of the whole measuring chain, showing similar values. The estimation of overall uncertainty (again through the procedure defined in [

34]) led to estimate levels around 1.5% for the different operating modes of the tested conditions.

2.3. Pressure Diagrams, Heat Release Rate, and Combustion Parameters Evaluation

A dedicated high-frequency sampling system measured in-cylinder pressure diagrams. Four signals were acquired at a rate defined according to the engine rotational speed, to obtain a sampling period corresponding to a 0.1 crank angle rotation (i.e., 120 kHz for n = 2000 rpm). In-cylinder and fuel pressure upstream of the injector were measured through sensors and amplifiers listed in

Table 2. Injector energizing current was assessed by a current sensor. Crank angle was gauged with a photoelectric incremental encoder.

Data processing was made by dedicated virtual instruments developed in LabVIEW

® environment, to calculate absolute pressure levels, to filter in-cylinder pressure signal, and to assess the average pressure diagram, peak pressure, and the relevant crank angle. As mentioned in

Section 2.2, 60 diagrams were sampled for each operating mode. Values of average and standard deviation of maximum pressure were calculated, as well as the corresponding coefficient of variation, allowing to check combustion stability when replacing conventional fuel with blends or neat biodiesel, as discussed in

Sections 3.3 and

3.4.

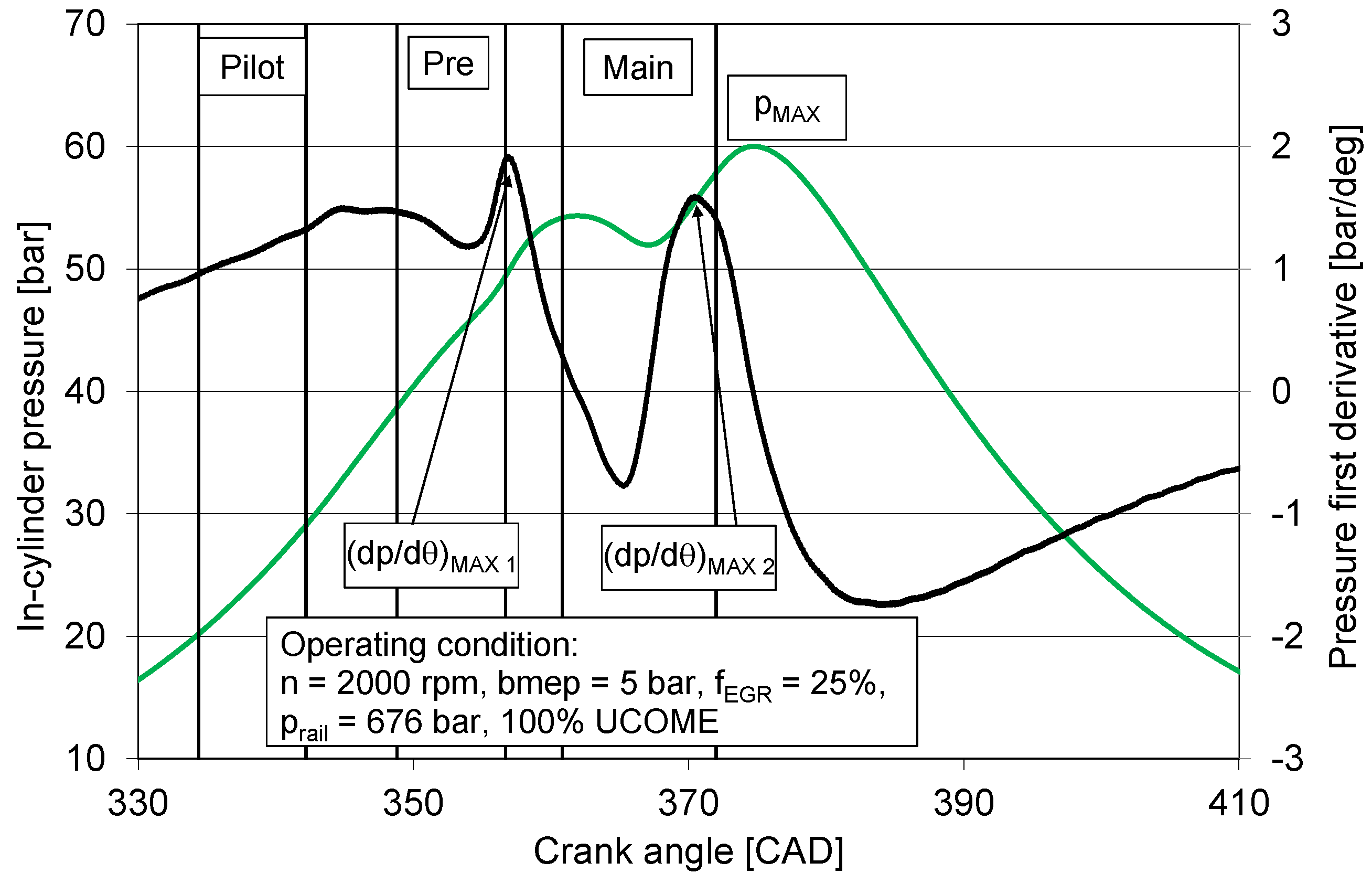

The proper filtering of pressure signal allows to calculate its first derivative (dp/dθ). An example of the two curves is shown in

Figure 2. As three fuel delivery events (pilot, pre and main) were actuated in the standard injection strategy, their timing and duration are also presented. Zero crank angle degree corresponds to the beginning of the intake stroke. Therefore, combustion TDC occurs at 360 crank angle degrees. Two maximum values are apparent from the pressure diagram. The first is related to the compression stroke and to the combustion of pilot and pre injections. The second maximum is given by the main combustion. The first derivative of pressure signal shows two maximum values as well, (dp/dθ)

MAX 1 and (dp/dθ)

MAX 2, having the same relationship with the injection strategy.

Pressure gradient at the beginning of the combustion can be related to noise emissions. A combustion noise indicator I

n was therefore evaluated, applying Equation 1 [

35]:

where n is the engine speed of the tested condition, n

idle is the engine speed in the idling mode, and (dp/dθ)

MAX is the maximum value of the pressure derivative of the compression-expansion signal in the unfired engine, calculated at the same intake conditions. Even if Equation 1 is based on an indirect approach, the strong relationship between combustion noise and the rate of in-cylinder pressure rise in diesel engines is confirmed in [

36], where it is concluded that this quantity represents a consistent indicator of noise levels in diesel engines.

The calculation of experimental rate of heat release for each tested engine operating condition was based on Equation 2, implemented in a Fortran code developed by the main author:

ΔQ is the heat released during a crankshaft rotation Δθ. The three terms of the equation are obtained through the application of the first law of thermodynamics to cylinder gas, assuming complete combustion and neglecting the variation of mass due to fuel injection [

37,

38]. The first term of Equation 2 is related to the measured level of in-cylinder pressure, multiplied by the corresponding variation of instantaneous cylinder volume. The second term is related to the pressure gradient between two subsequent samples. The third term represents heat transferred to the coolant, estimated using the Hohenberg correlation [

39]. The instantaneous cylinder volume is computed from measured crank angle and engine geometrical characteristics.

The evaluation of specific heats and their ratio was based on the composition of intake charge, the amount of the different chemical components inside the cylinder during combustion, and their temperature, applying thermodynamic property functions of different gases available in [

40].

Injected fuel mass flow rate in each calculation step was derived from experimental data. Actual values of pilot, pre and main injections start, and their duration were estimated by adding proper delays at the start and end of the current signal, according to [

41].

The burned mass fraction is obtained through the integration of heat release rate. It is then possible to identify the crank angles corresponding to the release of 10, 50 and 90% of the total thermal energy available when burning the fuel. θ50 represents the centre of combustion, generally considered for its control. The difference between θ90 and θ10 is assumed as an index of combustion duration, neglecting the initial and final phases, as the estimation of actual burning start and end angles may be affected by high uncertainties.

As in previous investigation [

42,

43], measured and calculated quantities obtained from pressure diagrams were considered to compare tested fuels and blends also referring to their combustion.

2.4. Engine Management System

The engine management system includes an open electronic control unit (ECU), an EPROM emulator module, an ETAS® MAC2F interface, and a personal computer with the INCA® software. INCA manages the ETK module to perform three main tasks, that is, real time visualization of engine parameters, selection of the required maps stored in the ECU, and change of control variables to actuate the experimental program.

The variable nozzle turbine is controlled either with open or closed loop strategies, according to the engine operating condition. The first option is applied at low levels of engine speed and load. In this case, the duty-cycle of an electro-pneumatic valve (DC

VNT) is selected. Consequently, a fixed value of variable nozzle turbine opening degree (A

VNT) is actuated. This parameter is defined by Equation 3.

S is the displacement of the turbine nozzle ring push rod (measured with a linear potentiometer). SMAX and SMIN are its maximum and minimum value. AVNT ranges from 0 to 100 percent, corresponding to the minimum and maximum values of turbine swallowing area.

At higher levels of engine speed and load, ECU switches to the closed loop control strategy, comparing an intake pressure set point with the measured level. DCVNT is then modified, if necessary, to reduce the calculated difference.

Fuel rail pressure (prail) control is based on a closed loop approach. A pressure regulator is properly managed to reduce the difference between the prail set point (evaluated by the ECU according to the engine operating condition or fixed according to the experimental program) and the measured value, given by the on-board sensor fitted on the common rail.

High pressure (HP) EGR system is also managed through a closed loop scheme, considering proper set point values of excess air ratio (λ). The actual level is obtained by the measurement of air mass flow rate. Fuel mass flow rate is calculated by the ECU to produce the engine torque requested by the driver. The duty-cycle of the electric HP EGR valve (DCEGR) is then modulated to reduce the difference, defining its opening degree and the mass flow rate of recirculated gases. To increase the mass of recirculated gases, lower values of λ must be set. EGR valve opening is then raised, achieving the requested reduction of air mass flow rate. On the other hand, a high value of λ (typically 6) is selected to close the valve and deactivate the EGR circuit.

EGR rate (f

EGR) is defined as the ratio between recirculated gas and total engine mass flow rate, given by the sum of air (M

a), fuel (M

f) and EGR (M

EGR) mass flow rates (Equation 4).

MEGR is calculated by applying an energy balance in the mixing section, considering the energy input of air and recirculated gases and the energy output of charge mass flow rates. To simplify the procedure, differences between specific heats at constant pressure and heat losses are neglected.

2.5. Tested Blends

Some of the main properties of reference fuel (diesel B7), WCOME, and their blends are presented in

Table 4. Tested biodiesel was supplied by an Italian refinery and is used to produce commercial B7 diesel. Therefore, its physical and chemical characteristics comply with the requested European standard for its application in the automotive sector. Fuel density was measured in the laboratory before each test. Biodiesel has higher level than diesel, with an increase of 5.3%. Therefore, blends with higher content of biodiesel show rising levels of density. Other characteristics were defined according to literature. Lower Heating Value (LHV) for WCOME is the average of values presented in [

44,

45,

46,

47]. Decreasing figures for this quantity were estimated for the different blends. Corresponding percentage reductions referred to B7 are also shown in

Table 4.

Oxygen, carbon and hydrogen content were obtained from [

44]. The stoichiometric values of air-fuel ratio (AFR) were then calculated, showing decreases below the reference one, due to the oxygen availability in renewable fuel. WCOME cetane number (CN) is very close to the reference one.

The composition of the waste cooking oil methyl esters was not available. An average content of the main fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) was defined considering different references [

17,

44,

48,

49,

50,

51]. As WCOME generally includes olive and sunflower oils [

44], the fatty acids content of their methyl esters is also reported. The largest percentages presented in

Table 5 are generally associated with oleic and linoleic unsaturated fatty acid.

2.6. Investigation Program

Two part load engine operating conditions were selected for tests, with increasing levels of brake mean effective pressure at the same rotational speed (

Table 6). In each point, high pressure EGR circuit was first controlled, starting with the EGR valve fully closed, then applying three decreasing levels of excess air ratio (i.e., increasing EGR rate), including λ standard value and a lower level. In these four operating modes, rail pressure standard level was applied. Then, at the higher EGR rate, rail pressure was increased, firstly of +7.5%, then of +15% compared to the standard set point.

HP EGR control leads to variations of turbine and compressor working conditions, so that engine pressure gradient is modified, affecting fuel consumption and brake thermal efficiency. Variable nozzle turbine was therefore managed to keep the intake pressure at a constant level, selecting proper values of DC

VNT (listed in

Table 6), as both the tested operating conditions belong to the area of open loop control scheme.

Constant values were applied to injection event parameters (injections timing, quantity of fuel delivered in the pilot and pre injections), to exclude the impact of their variations on engine behavior.

The listed operating modes were applied to all the fuels and blends considered in the experimental campaign (

Table 4). The only exception was the neat biodiesel, for which only the second operating condition (2000x5) was tested.

3. Results and Discussion

Results are presented firstly considering the influence of high-pressure EGR system control on operating, energy, environmental, and combustion parameters in the two tested operating conditions for reference diesel oil, blends, and neat biodiesel. Therefore, trends are analyzed as a function of EGR rate, while keeping fuels/blends composition as a parameter.

Then, the effect of rail pressure control is shown for the maximum value of EGR rate, considering most of the same quantities. In this case, trends are presented as a function of rail pressure, for the tested fuels in both operating conditions. Referring to brake thermal efficiency and specific emissions, the comparison with the standard conditions will be also presented, to assess if an integrated control strategy of the three engine sub-systems allows for the enhancement of the different parameters when switching to blends with a high content of renewable fuel (or even 100% WCOME). In some cases, only outcomes for the 2000x5 experimental point are shown, for the sake of clarity.

3.1. Influence of HP EGR System Control on Operating Parameters

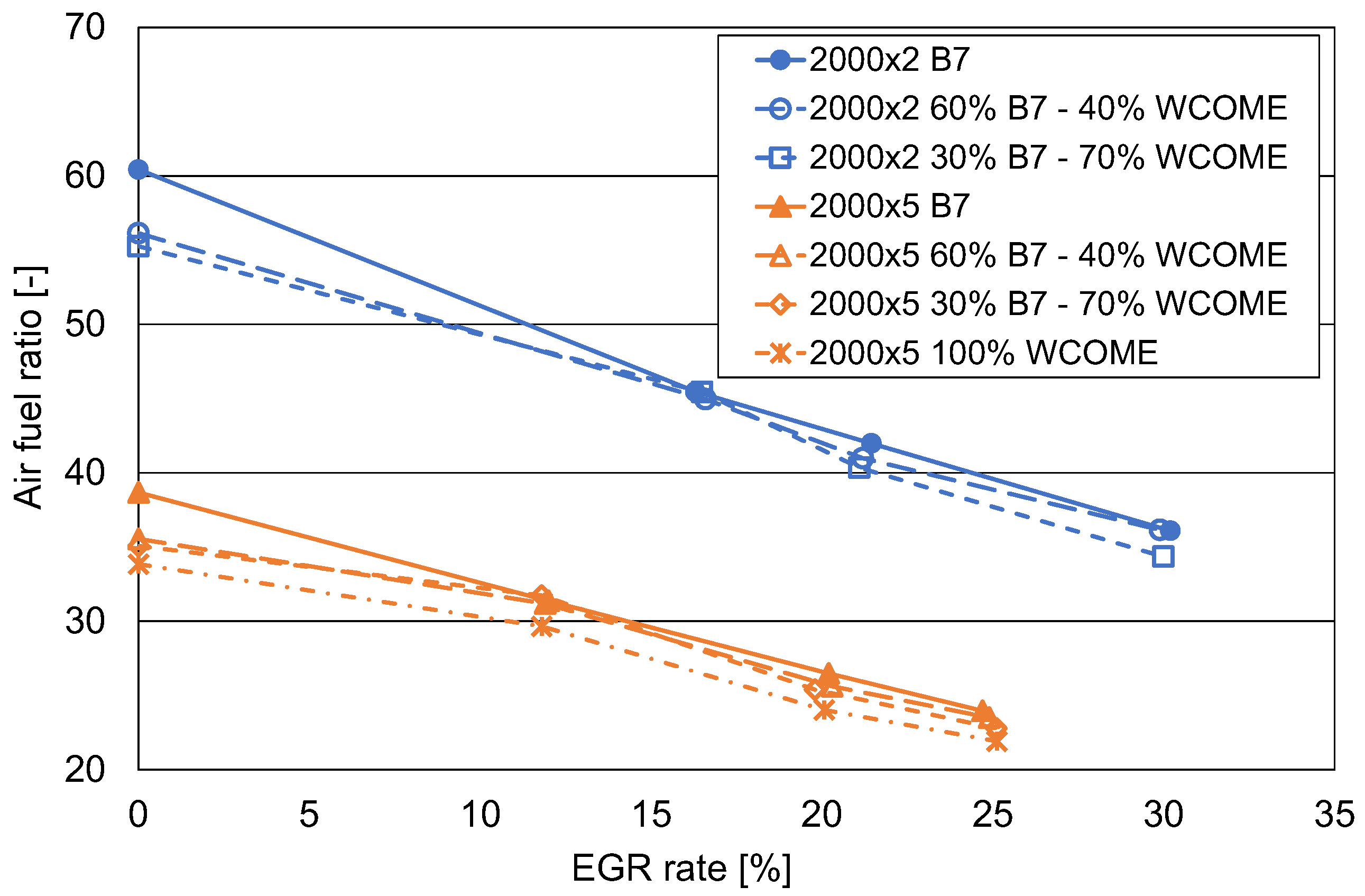

Figure 3 provides values of air fuel ratio, showing decreasing trends for higher levels of EGR rate, due to the wider replacement of fresh air with recirculated gases. For bmep = 5 bar, AFR is of course lower, because of the larger amount of fuel required by the increased engine load. When introducing biodiesel, at constant load and EGR rate, slightly lower level of AFR is observed, because of the increase in fuel consumption (

Figure 6).

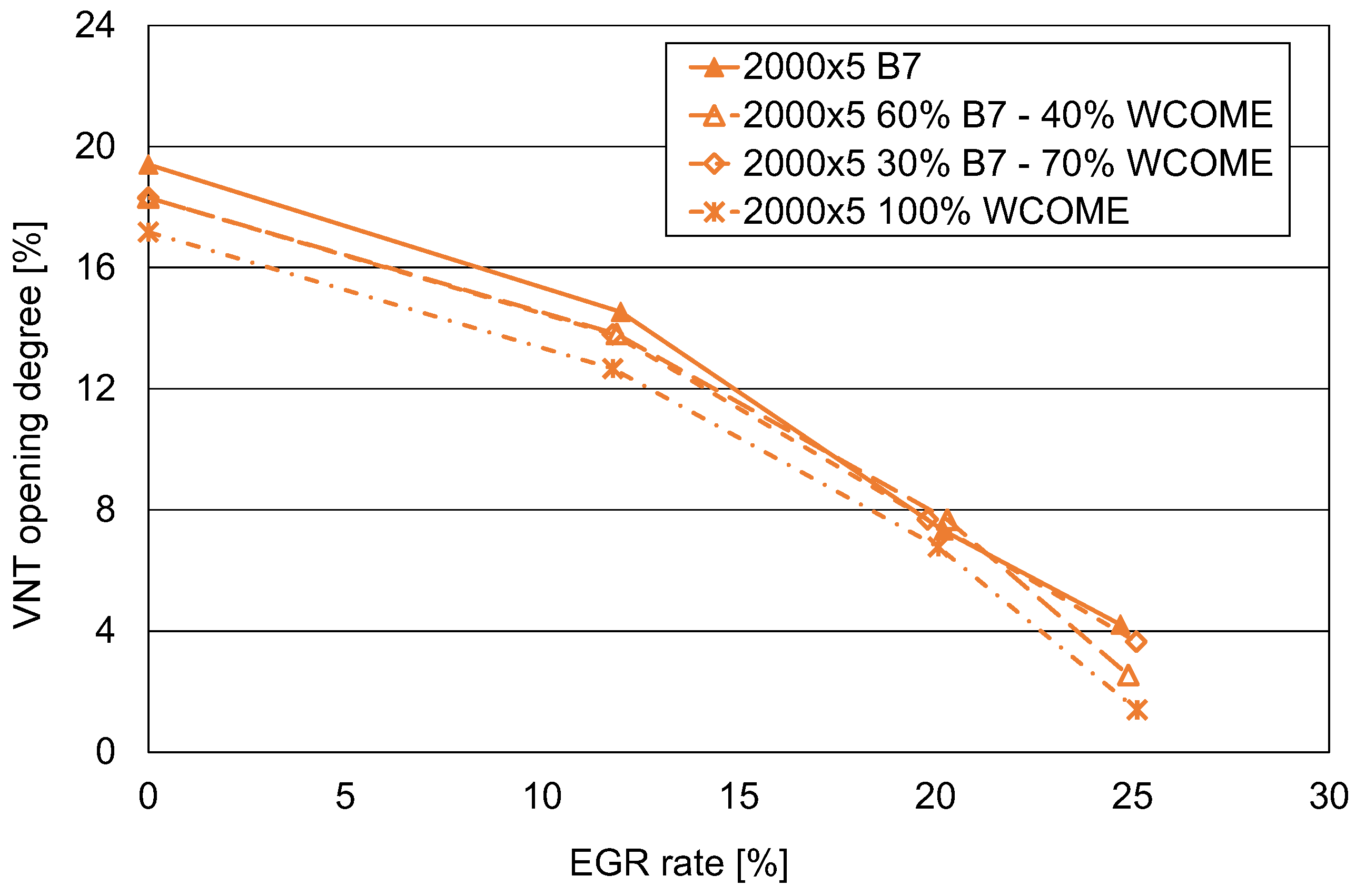

Variable nozzle turbine opening degree is presented in

Figure 4, referring only to 2000x5 experimental condition. The graph allows to identify that, to keep the intake pressure at a constant value when higher EGR rates are applied (i.e., to fulfil the target related to the turbocharger control), it is necessary to reduce the turbine inlet area available for the gases entering the machine, to compensate for their mass flow rate reduction. For the maximum EGR rate, A

VNT is very close to zero. This behavior justifies the corresponding trends of engine pressure gradient (calculated as turbine inlet pressure – intake pressure, i.e., p

3 – p

i), presented in

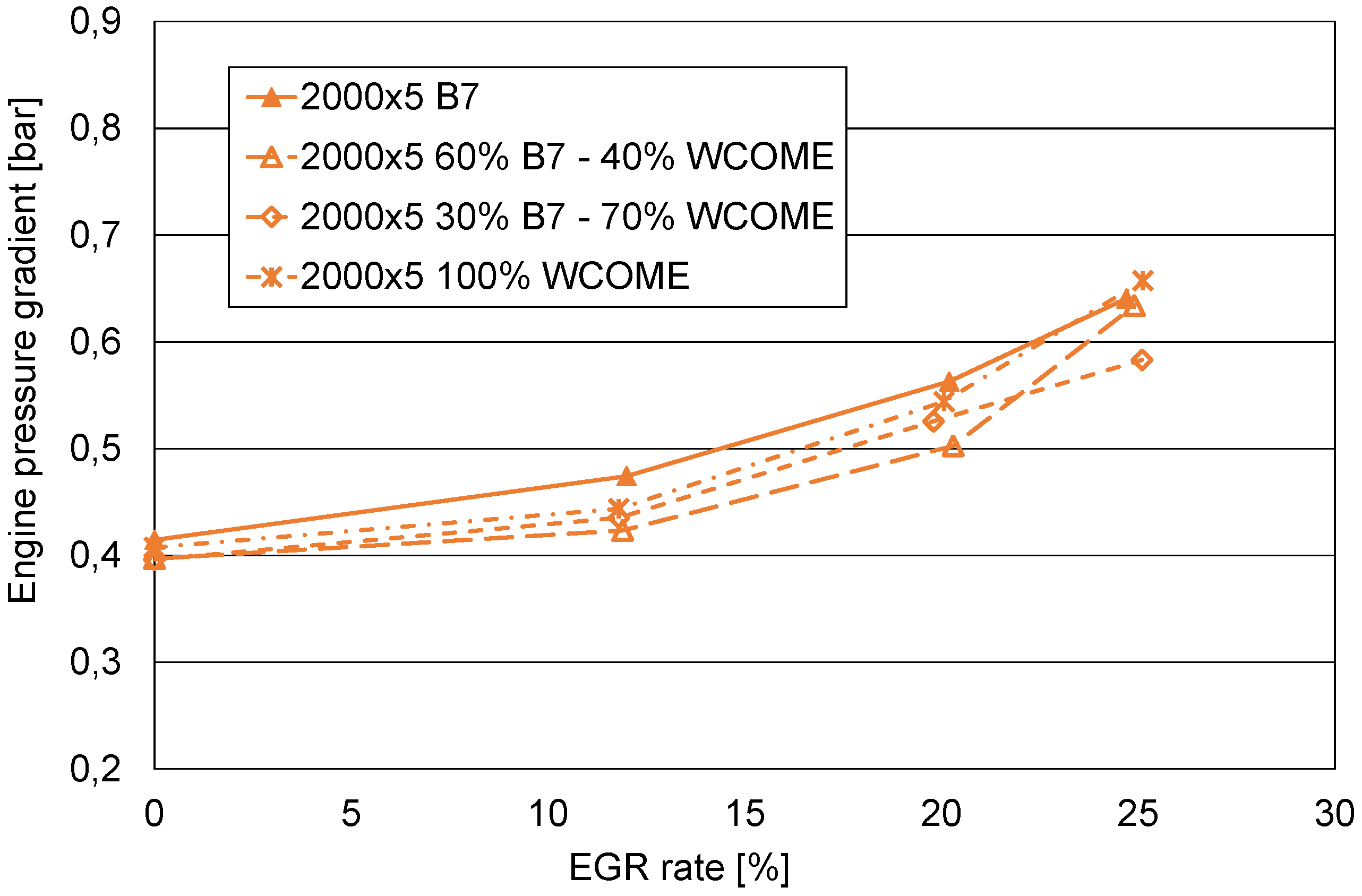

Figure 5. Due to the closure of the nozzle, increased levels of turbine inlet pressure are detected, leading to the rise of this quantity for higher EGR rate. Therefore, pumping losses are also increased, negatively affecting fuel consumption. Other choices are available for the management of turbine operations, modifying the interactions between HP EGR circuit, turbocharging system, and the engine. For example, a constant value of variable nozzle turbine opening degree can be applied. In this case, EGR activation would lead to a reduction of engine pressure gradient, pumping losses and fuel consumption, as discussed in [

33,

52]. Finally, intermediate strategies for A

VNT management can be also considered. Limited variations of engine pressure gradient are outlined comparing values at constant operating mode when changing the fuel, therefore their effects can be neglected.

3.2. Influence of HP EGR System Control on Efficiency and Emissions

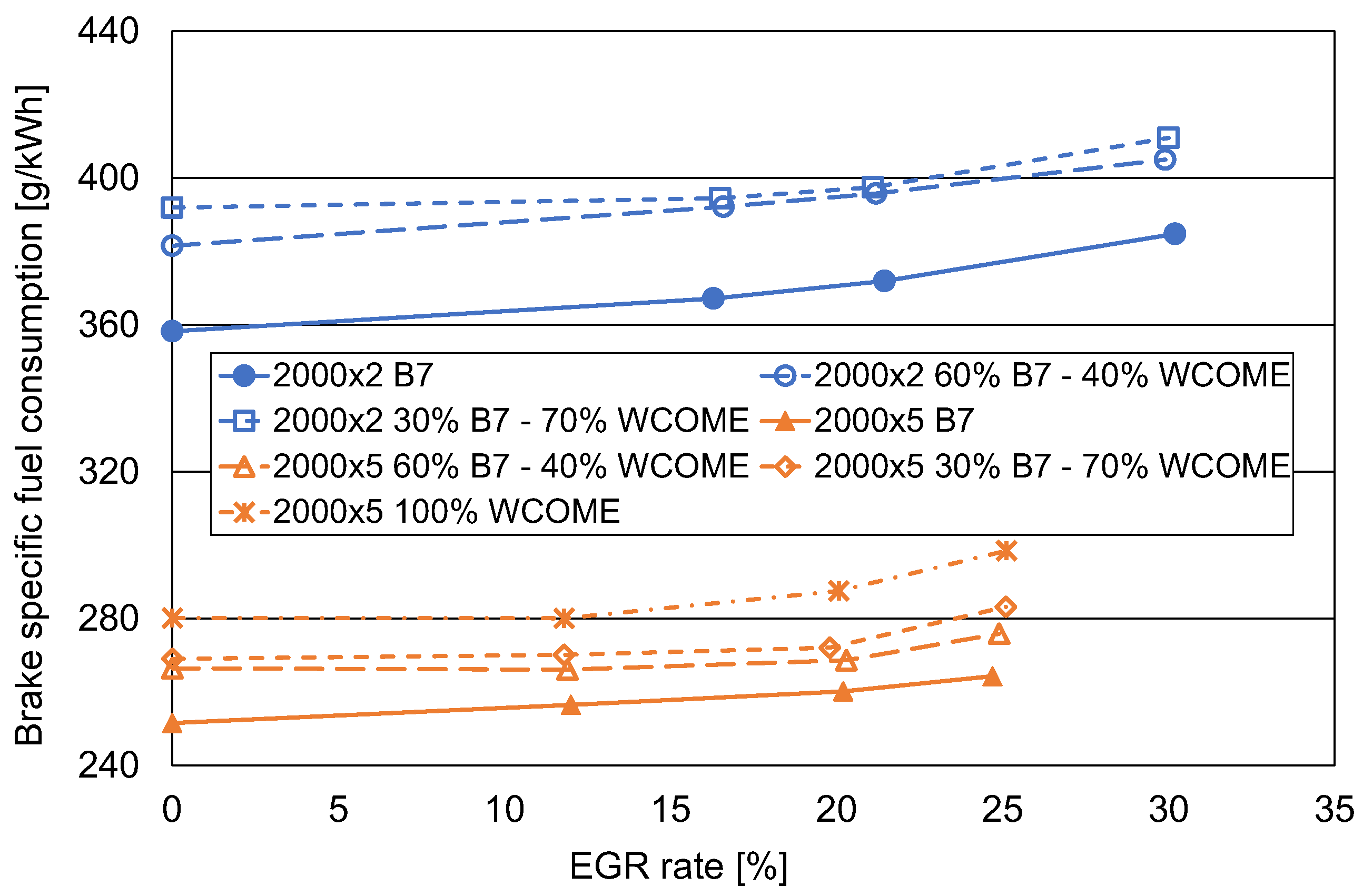

Trends of brake specific fuel consumption are shown in

Figure 6. At constant operating condition and fuel/blend, bsfc values increase with EGR rate, because of VNT control affecting engine pressure gradient and pumping losses, as outlined in Figs.4 and 5. Compared to levels measured without EGR, the highest percentage variations are detected for the maximum EGR rate, ranging between 4.8 ÷ 7.4% in experimental point 2000x2 and between 3.5 ÷ 6.6% in operating condition 2000x5, depending on the fuel. In any case, these variations are well above the corresponding uncertainties (

Table 3).

When comparing values at constant operating condition and EGR rate, higher values of bsfc can be observed replacing conventional B7 with the blends. Increasing WCOME content leads to a reduction in Lower Heating Value (

Table 4). To supply the same amount of energy to the engine, it is therefore necessary to have a higher amount of fuel. The largest increase is measured when using pure biodiesel.

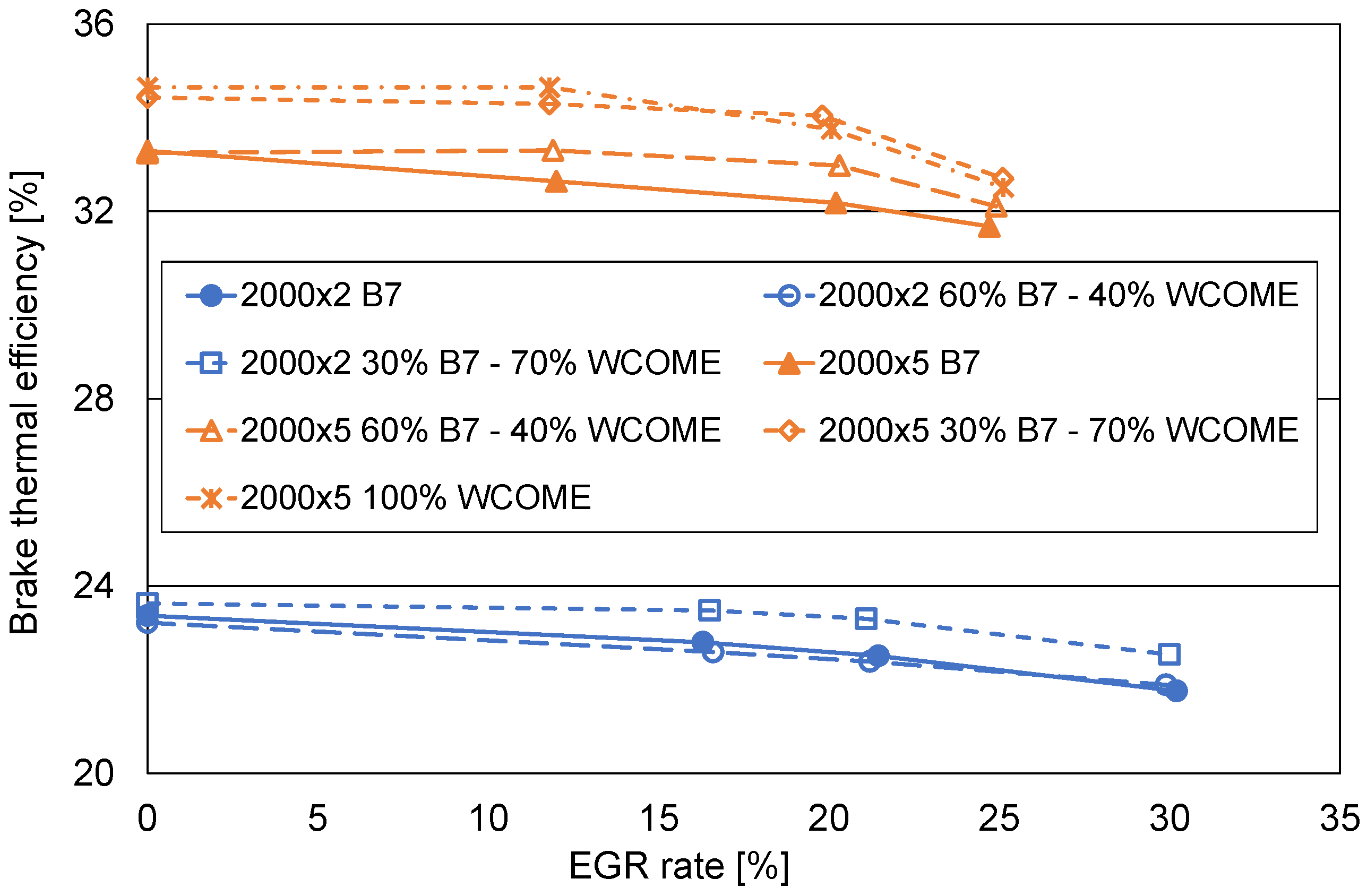

The effects on engine operations can be better identified considering brake thermal efficiency, presented in

Figure 7, because the influence of LHV is removed by directly comparing energy input and output. At constant operating condition and EGR rate, better efficiency is obtained for larger WCOME content (even if in point 2000x5, blend with 70% of WCOME is better than 100% WCOME for standard and maximum EGR rate). It is worth noting that percentage variations are quite interesting, ranging between 3 ÷ 6% in different operating modes. This output can be justified by a better development of the combustion process, outlined by the reduction of the combustion duration shown in

Figure 12, as also assessed in [

12,

53]. Better bte is generally observed when testing biodiesel, as already outlined in the Introduction [

12,

16] and observed in an investigation on WCO [

54].

On the other hand, at constant operating condition and fuel/blend, a reduction in efficiency is observed at higher EGR rate, because of the increase of fuel consumption. Of course, the higher bmep level is associated with higher values of efficiency and lower levels of bsfc, because of the reduced negative influence of thermal and mechanical losses.

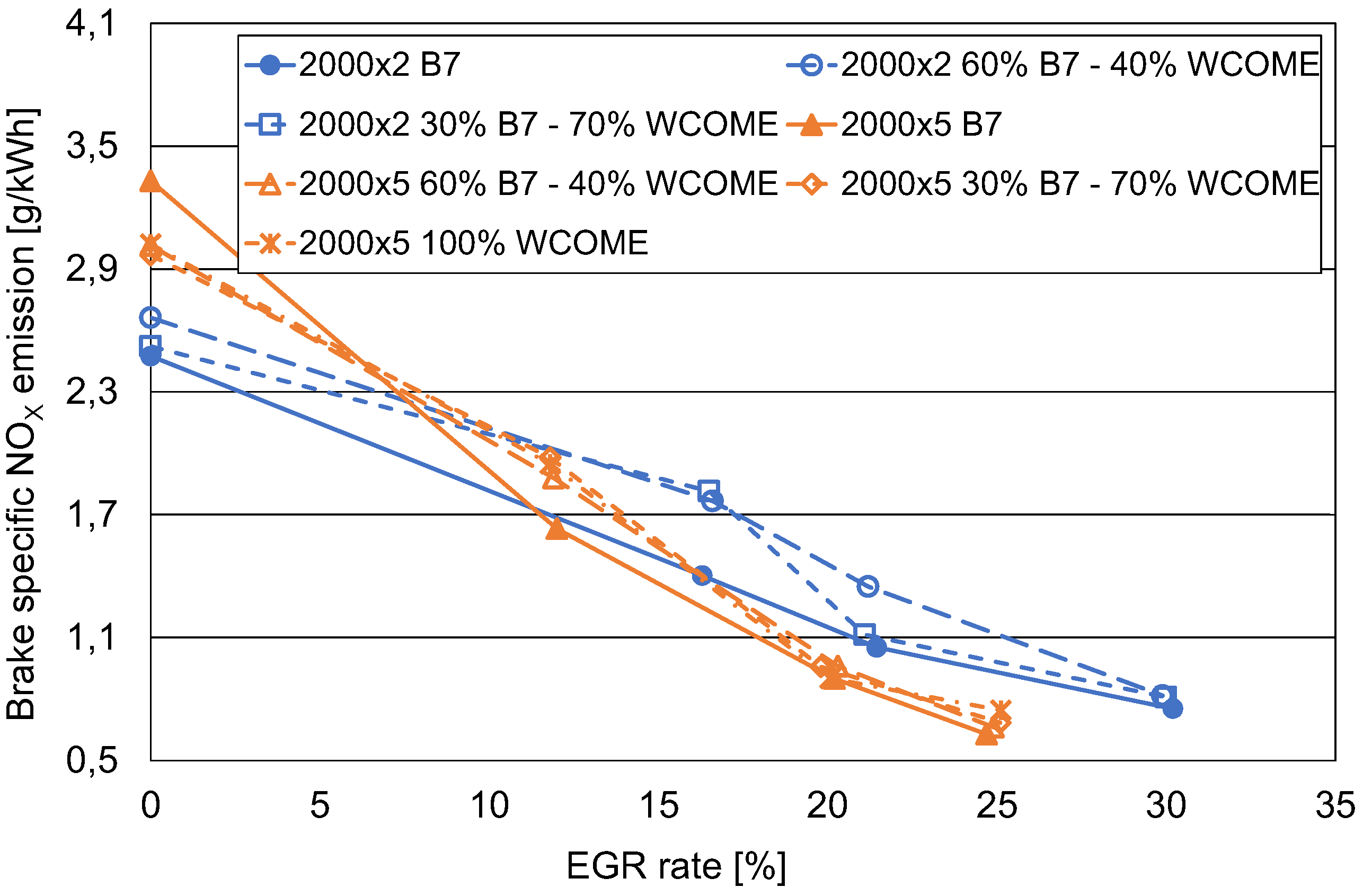

Brake specific NO

X emission is presented in

Figure 8. The expected influence of EGR is confirmed, thanks to the dilution effect, decreasing the oxygen concentration in the combustion chamber. Referring to the operating mode without EGR, reductions are around 55% and 68% in the two experimental conditions when adopting the standard value of excess air ratio, corresponding to an EGR rate equal to 20% in both cases. When the EGR valve is further opened, EGR rate reaches 30% in point 2000x2 and 25% in point 2000x5 and the decreases in NO

X emission are around 70 and 80%, respectively. Even if trends are not so clear as in the case of fuel consumption and efficiency, at constant operating condition and EGR rate, the use of blends and neat biodiesel leads to the increase of NO

X emission. As already discussed in the Introduction, the influence of biodiesel on NO

X emission can be different, according to the prevailing effects related to involved phenomena.

On one side, a larger formation of NO can be related to the oxygen content of biodiesel [

15] and to the reduction of heat dissipated by radiation, because of lower formation of soot, leading to higher temperature in combustion chamber [

15,

16]. Other aspects are the variations of cetane number (but minimal changes are estimated for tested blends,

Table 4), changes of injection parameters (avoided in this study, as discussed in

Section 2.6) and interactions between the characteristics of renewable fuel and engine control strategies, as discussed in [

15]. Fuel physical properties and the relevant changes in flame structure and temperature are mentioned in [

12] as main influencing factors of NO

X formation.

On the other hand, lower NO

X emissions can be related to local effects with a positive influence, such as the reduction of LHV (

Table 4), because of the lower amount of heat locally available in the combustion chamber, resulting in lower temperature levels, as discussed in [

47]. Furthermore, adiabatic flame temperature can decrease, because of the differences in carbon and hydrogen content between diesel and biodiesel, as outlined in [

20], while a different distribution of mixture air-fuel ratio can be observed, related to the oxygen availability in biofuel molecules. Finally, biodiesel chemical composition influences the combustion process development. This is mainly due to the number of double carbon bonds [

55], resulting from the content of unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters and the iodine number. Referring to this aspect, controversial effects can be found in literature. On one side, a negative influence on NO

X emissions is generally associated with these quantities, even if with minor effects in the case of common rail engines [

15]. But in other studies [

49,

56], a new parameter was proposed, namely the Degree of Unsaturation (DOU). Methyl esters of vegetable oils generally show DOU values lower than diesel oil (e.g., 1.7 for olive methyl ester, 2.6 for sunflower methyl ester, 3.0 for diesel oil [

49]). Lower DOU values lead to a decrease in NO

X emissions.

In this investigation, negative effects prevail, leading to the observed increase shown in

Figure 8.

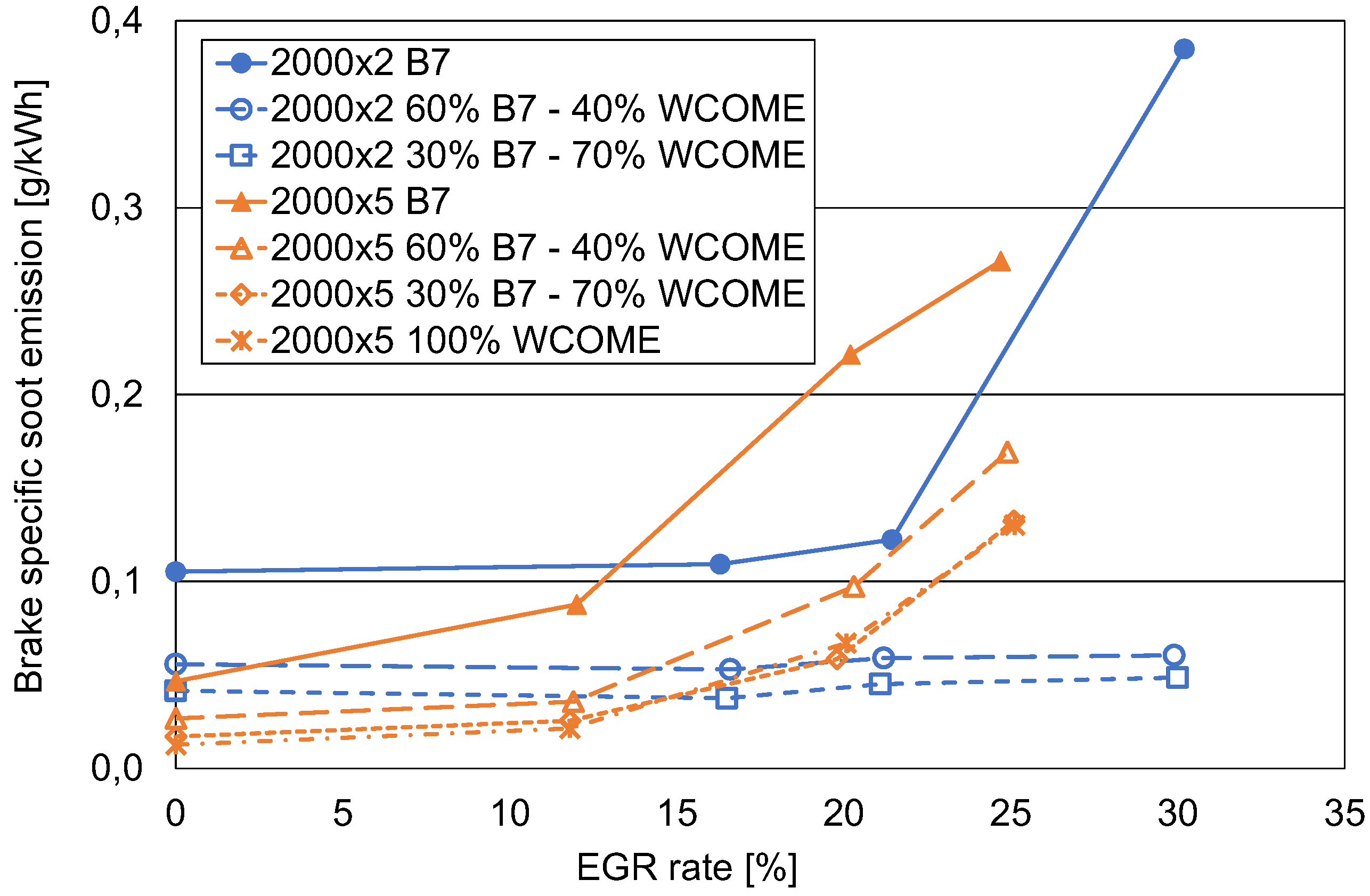

Brake specific soot emission is presented in

Figure 9. EGR activation leads to the increase of this pollutant, because of the reduction of oxygen availability [

15,

18,

19]. The increase is larger for the conventional B7 diesel oil. When switching to blends, the oxygen content of biodiesel partly (2000x5) or totally (2000x2) compensates for the dilution effect induced by EGR. Differences between the two points are probably related to the different levels of AFR. Oxygen coming from WCOME is directly involved in the combustion process, reducing the extension of local fuel rich zones inside the cylinder, especially at the ignition of the mixture [

12]. There is a general agreement on the reduction in soot emissions when using WCOME [

26,

28,

30,

31,

54], even if the overall effects on limited soot formation and modified soot oxidation are quite complex [

12].

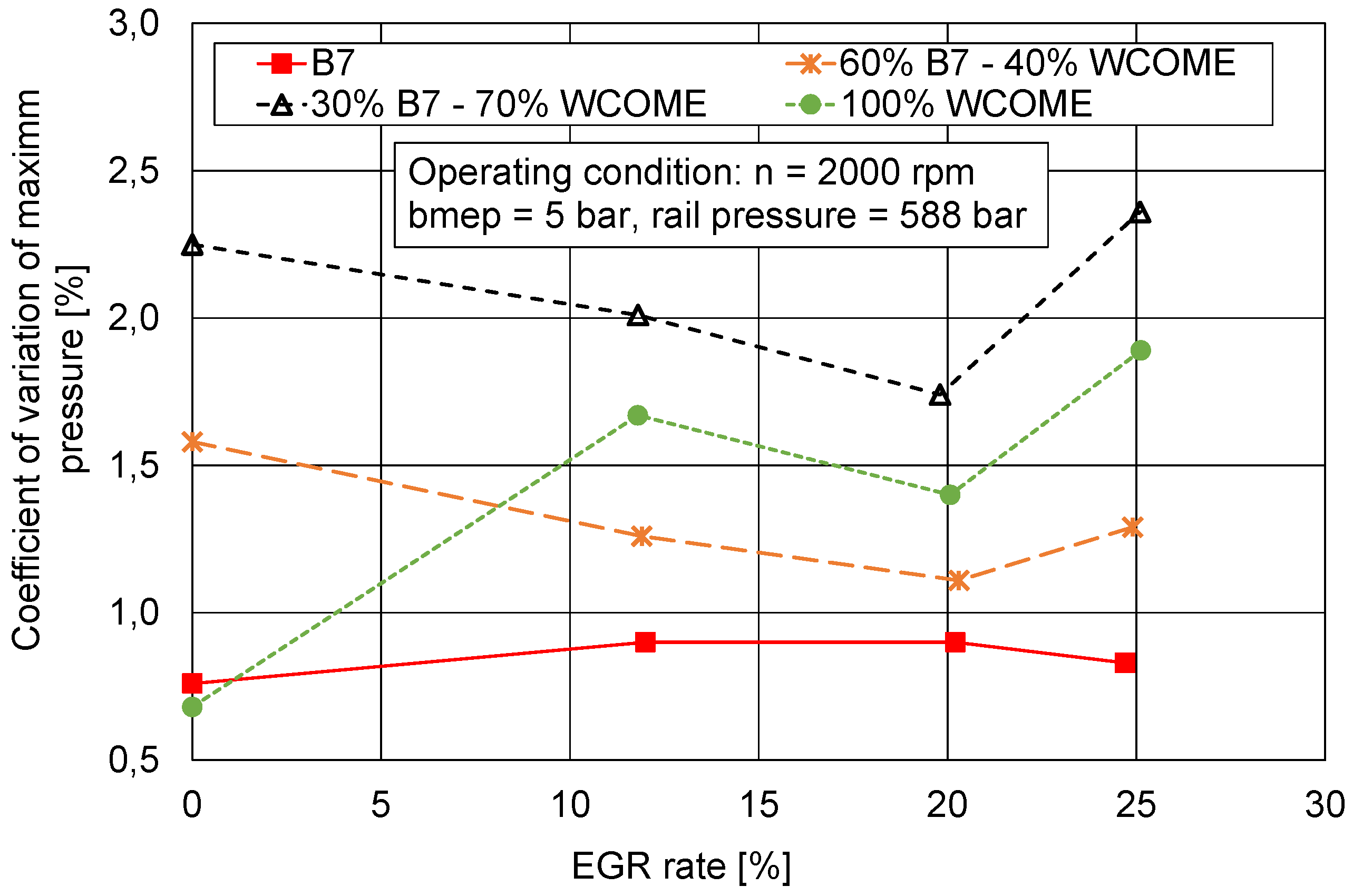

3.3. Influence of HP EGR System Control on Combustion Parameters

Figure 10 presents trends of the coefficient of variation of maximum pressure for one of the tested operating conditions (2000x5), obtained from the processing of indicated pressure diagrams described in

Section 2.3. This quantity is an index of combustion stability, which is verified if CoV is lower than 2-3% [

57]. There is not a clear influence of EGR rate on this parameter. Lowest values are apparent for the reference B7 diesel oil, while a slight increase can be observed when considering blends or neat biodiesel. Anyway, combustion stability is always granted.

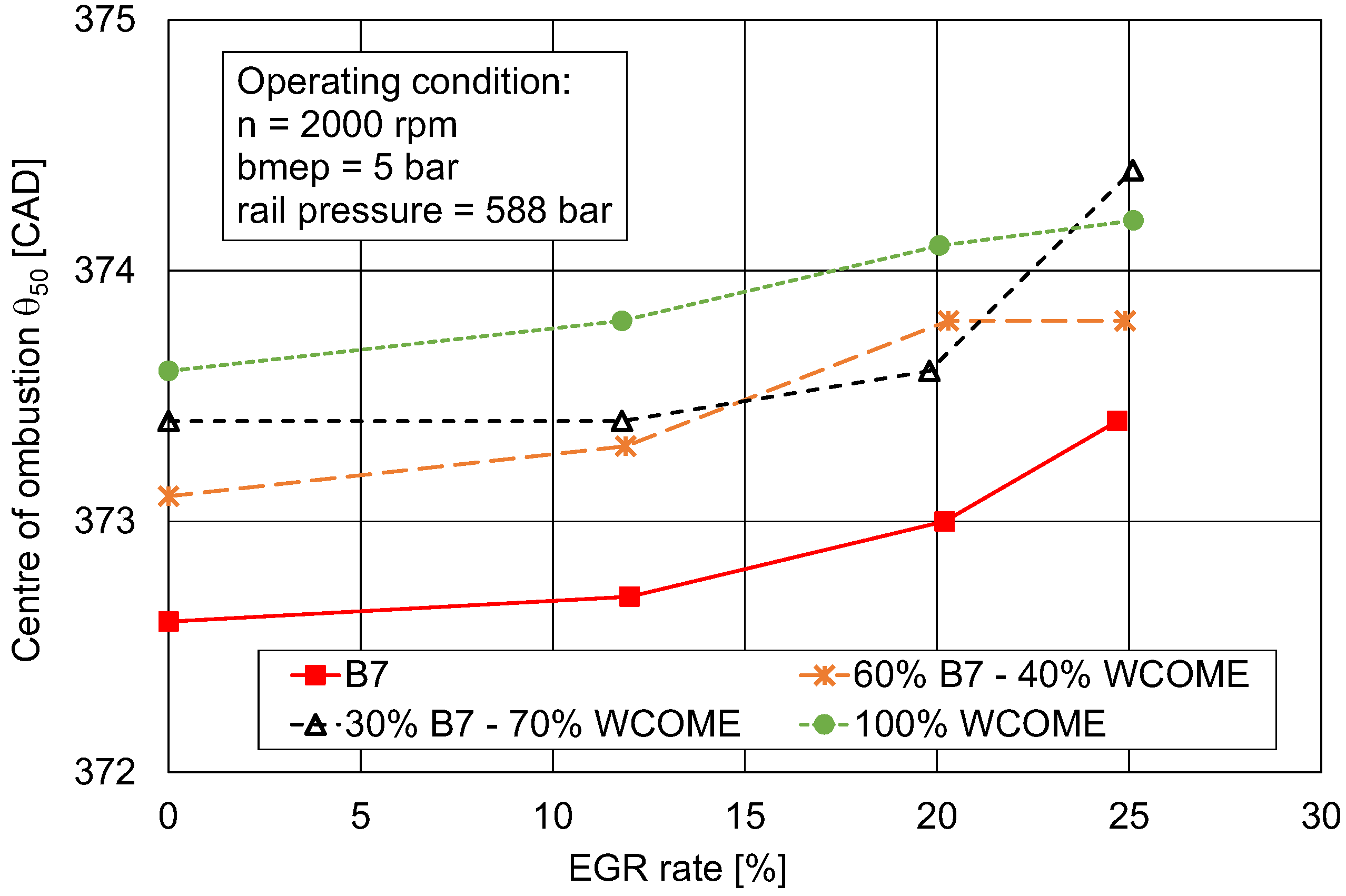

Figure 11 shows the behavior of the centre of combustion θ

50. The increase of EGR rate leads to a shift of the combustion within the expansion stroke, as θ

50 values are slightly higher moving on a line for each tested fuel/blend. A similar outcome is apparent when comparing levels measured for B7 diesel oil with those corresponding to blends and neat biodiesel at the same operating mode (load, EGR rate, rail pressure). Replacing the conventional fuel with the alternative one or its blend leads to higher values of θ

50. This outcome is justified in [

12] with the higher viscosity of biodiesel, leading to poorer atomization and longer ignition delay. A further contribution to the slower development of the combustion process in the initial phase may be related to the higher density of WCOME and its blends (

Table 4).

When analyzing values of the combustion duration θ

90 - θ

10 (

Figure 12), opposite effects are apparent for EGR and renewable fuel. While EGR leads to a slower combustion process because of the dilution effect, a shorter duration is obtained for blends and 100% WCOME, at constant operating mode. Therefore, it can be deduced that the use of biodiesel results in a slightly slower process at the start of the combustion (as θ

50 moves far from TDC), but in a shorter duration considering the overall reaction. The same result is reported in [

12,

53]. Biodiesel combustion accelerates near the end of combustion, overtaking the process of diesel. In the turbulent diffusive flame front typical of diesel combustion, the oxygen supply to the unburned fuel is gradually reduced. In the case of biodiesel, fuel-bound oxygen content compensates for the effects of locally insufficient oxygen.

The initial phase of the combustion is also affected by the physical characteristics of WCOME. As explained in [

15,

18,

20], the spray characteristics, the distribution of fuel droplets diameter, and the mixture formation depend on viscosity and density. Furthermore, the evaporation rate is related to the distillation curve of biodiesel [

15] and to the oxygen content [

18].

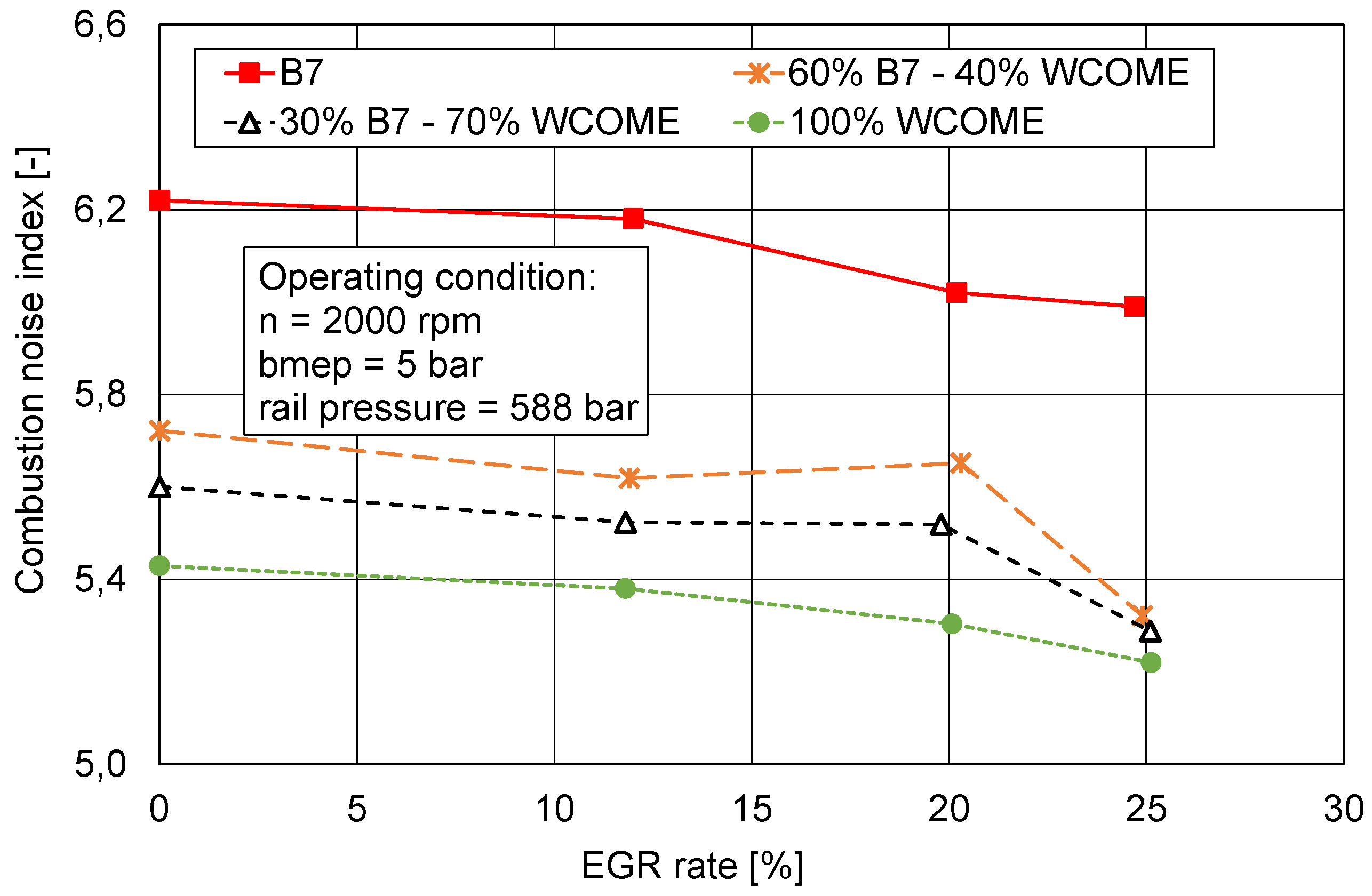

A further effect is apparent when analyzing combustion noise index I

n, defined by Equation 1 and presented in

Figure 13. In this case, when EGR increases, a slight reduction in the index is assessed, because of the slower combustion process in the first phase involving fuel delivered by the pilot and pre injections and at the beginning of the main injection, with decreased levels of maximum pressure gradients. At constant EGR rate, increasing WCOME content also leads to a reduction of I

n, because of the decreased speed of combustion in the first phase [

12].

3.4. Influence of Rail Pressure Control at Maximum EGR Rate

Effects of rail pressure control are widely investigated. The author presented them in previous papers [

33,

43], supported by an extended bibliography. Summarizing, higher fuel injection pressure results in better atomization of the fuel droplets, with faster evaporation and an enhanced mixture preparation. The expected consequences are a reduction in the ignition delay, a faster premixed phase of the combustion process, with a rise in peak pressure and pressure gradient, and a shorter duration of the combustion. On the emissions side, better combustion leads to an increase of NO

X emission, but better atomization corresponds to a reduction in pyrolysis reactions, limiting formation of soot particles.

In this section, the effects of the rail pressure increase will be analyzed, considering the maximum value of EGR rate for each tested condition and the use of biodiesel, to point out the different aspects listed in the Introduction. For thermal efficiency and emissions, reference values will be also shown in the relevant graphs, to highlight if the integrated control strategy of EGR and common rail allows for the achievement of benefits compared to the standard management, thanks to the replacement of conventional fuel with biodiesel.

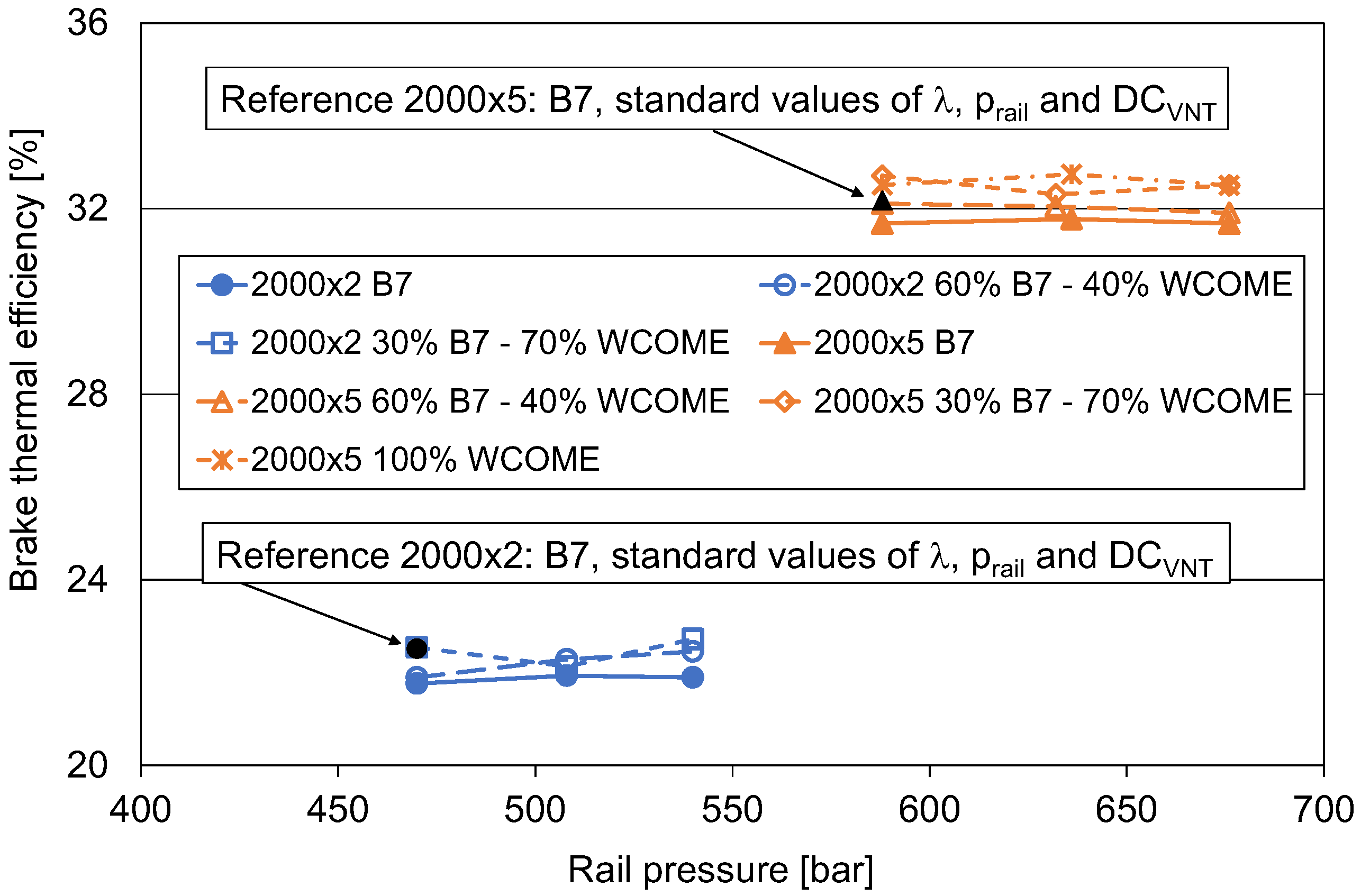

Trends of brake thermal efficiency are shown in

Figure 14. For a selected fuel/blend, no changes are apparent when increasing rail pressure. When comparing reference condition to operating modes with blends and neat WCOME, in the first operating condition (2000x2), benefit was not observed. In 2000x5 experimental point, the largest increase is equal to 1.74% for 100% WCOME and rail pressure = 636 bar.

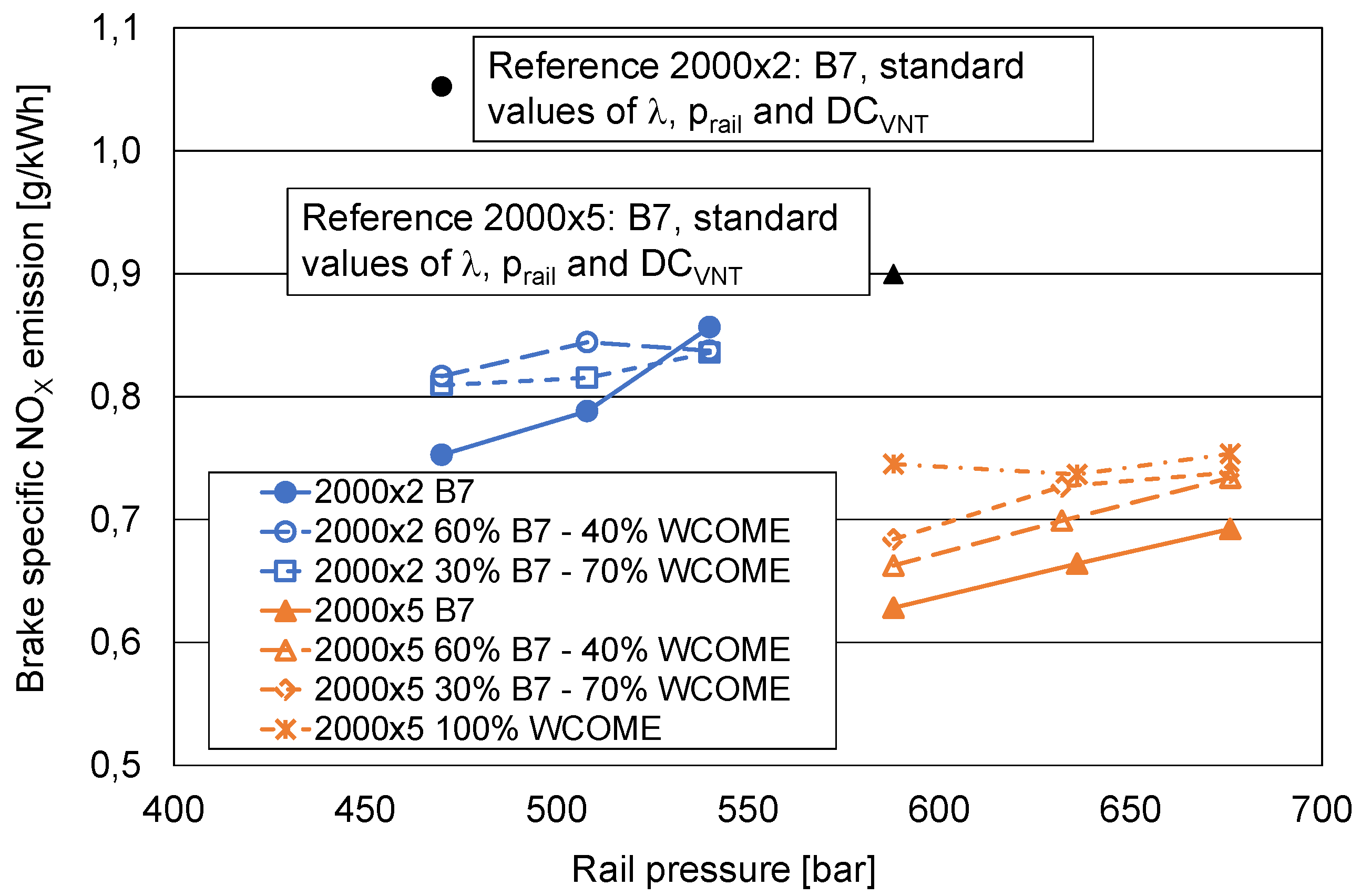

Values of brake specific NO

X emission are presented in

Figure 15. As expected, emission increases with rail pressure, because of the phenomena previously described. The use of biodiesel results in higher emission, as already explained in the analysis of

Figure 8. Nonetheless, in these operating modes the higher EGR rate allows for a significant reduction compared to the level in reference conditions. In both experimental points, the average decrease is around 22%.

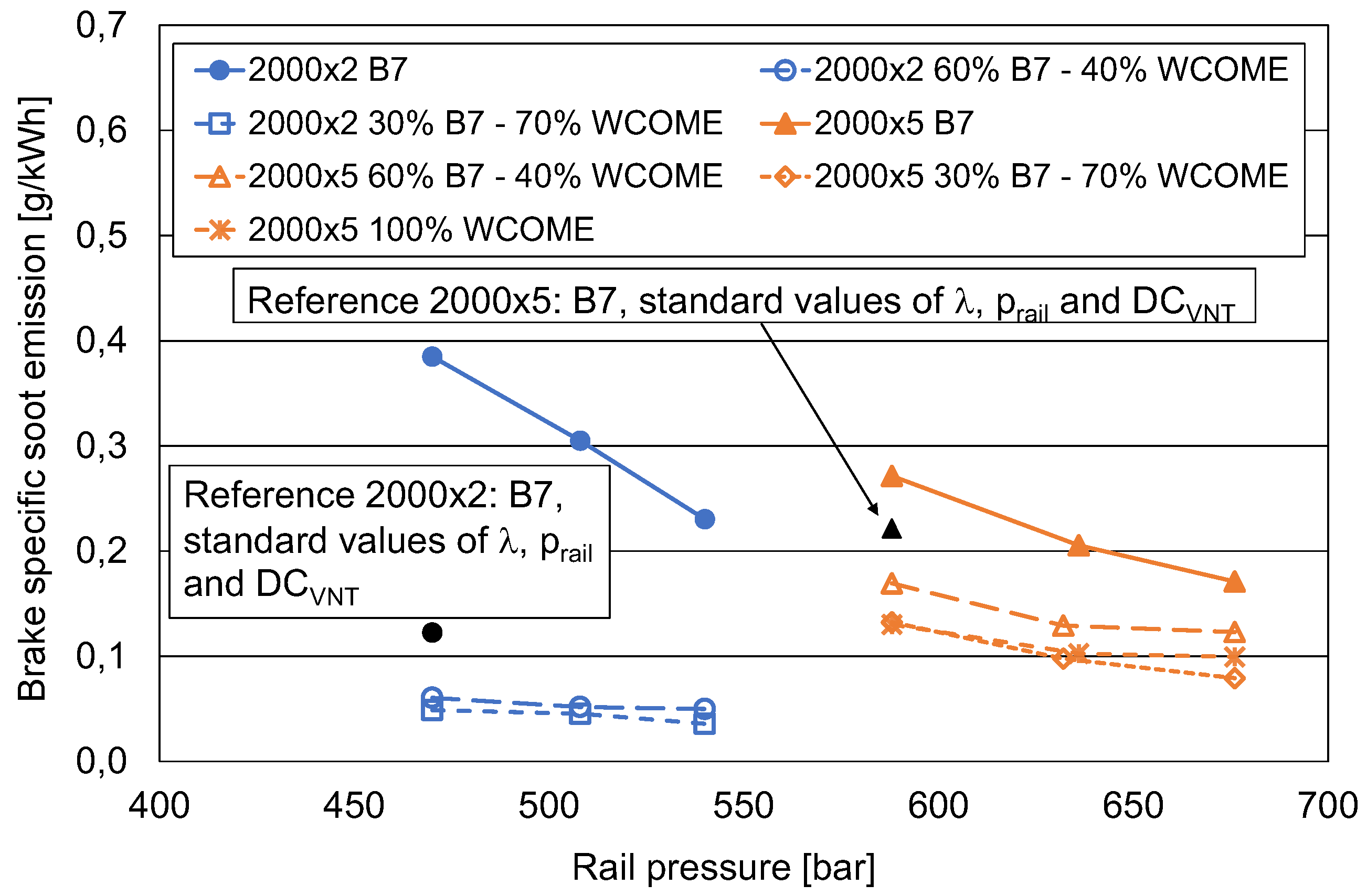

Levels of brake specific soot emission are presented in

Figure 16. When using conventional fuel, the higher EGR rate leads to an increase of soot, because of the larger dilution effect with lower oxygen availability compared to the standard mode. Each line shows a reduction when higher values of rail pressure are applied, because of the lower occurrence of pyrolysis reactions. Finally, the beneficial effect of oxygen provided by WCOME allows to largely compensate the negative influence of EGR. On average, soot emission reduction compared to the reference value is around 45% in the first operating condition (2000x2) and 58% in the second point (2000x5).

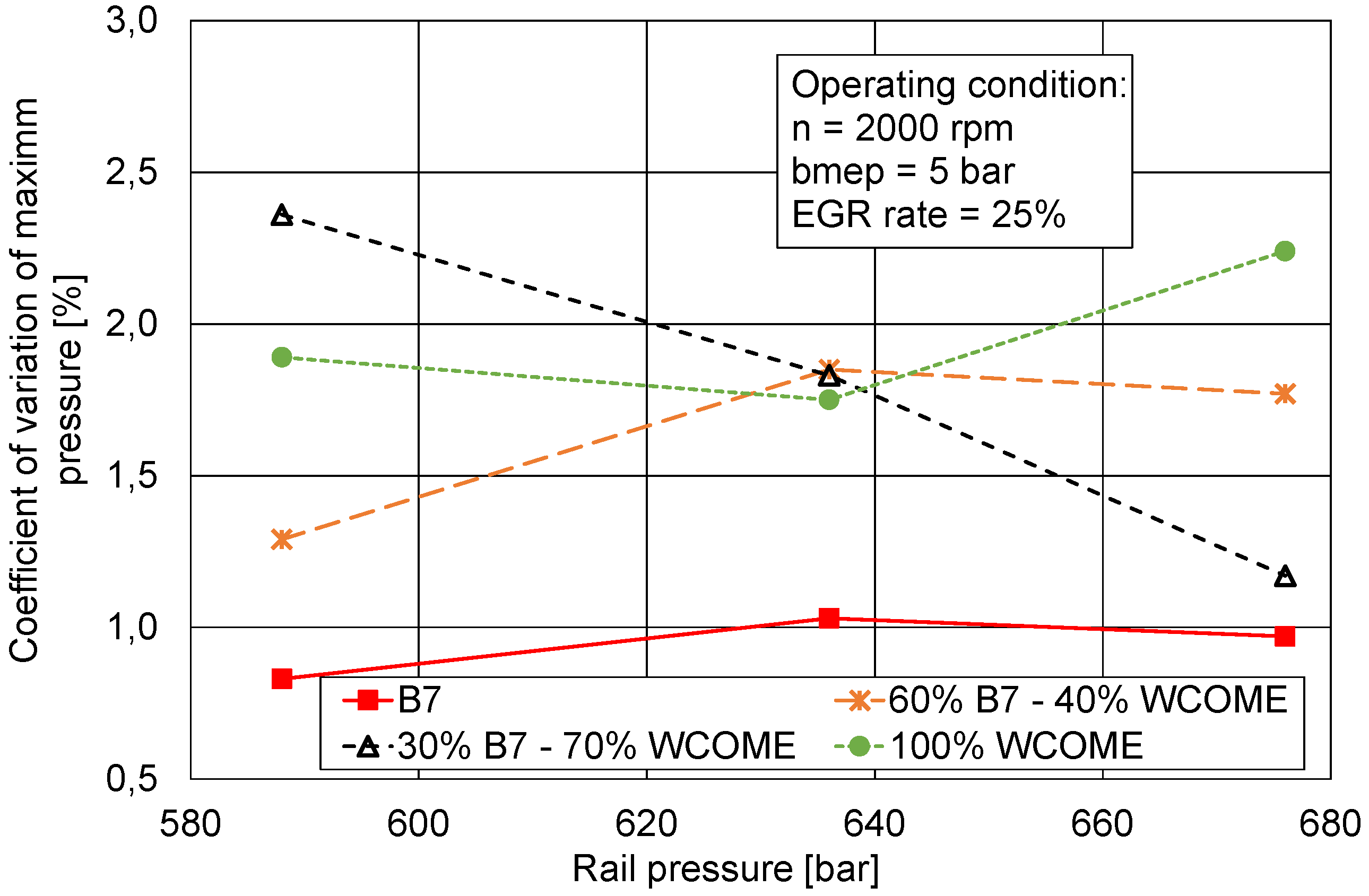

Moving to the analysis of combustion parameters, the coefficient of variation of maximum pressure is shown in

Figure 17. As for the influence of EGR (

Figure 10), there is no clear effect of rail pressure on this quantity, but values are below 2.5%, granting for combustion stability. It is also confirmed that blends and neat biodiesel show levels of CoV higher than the conventional B7.

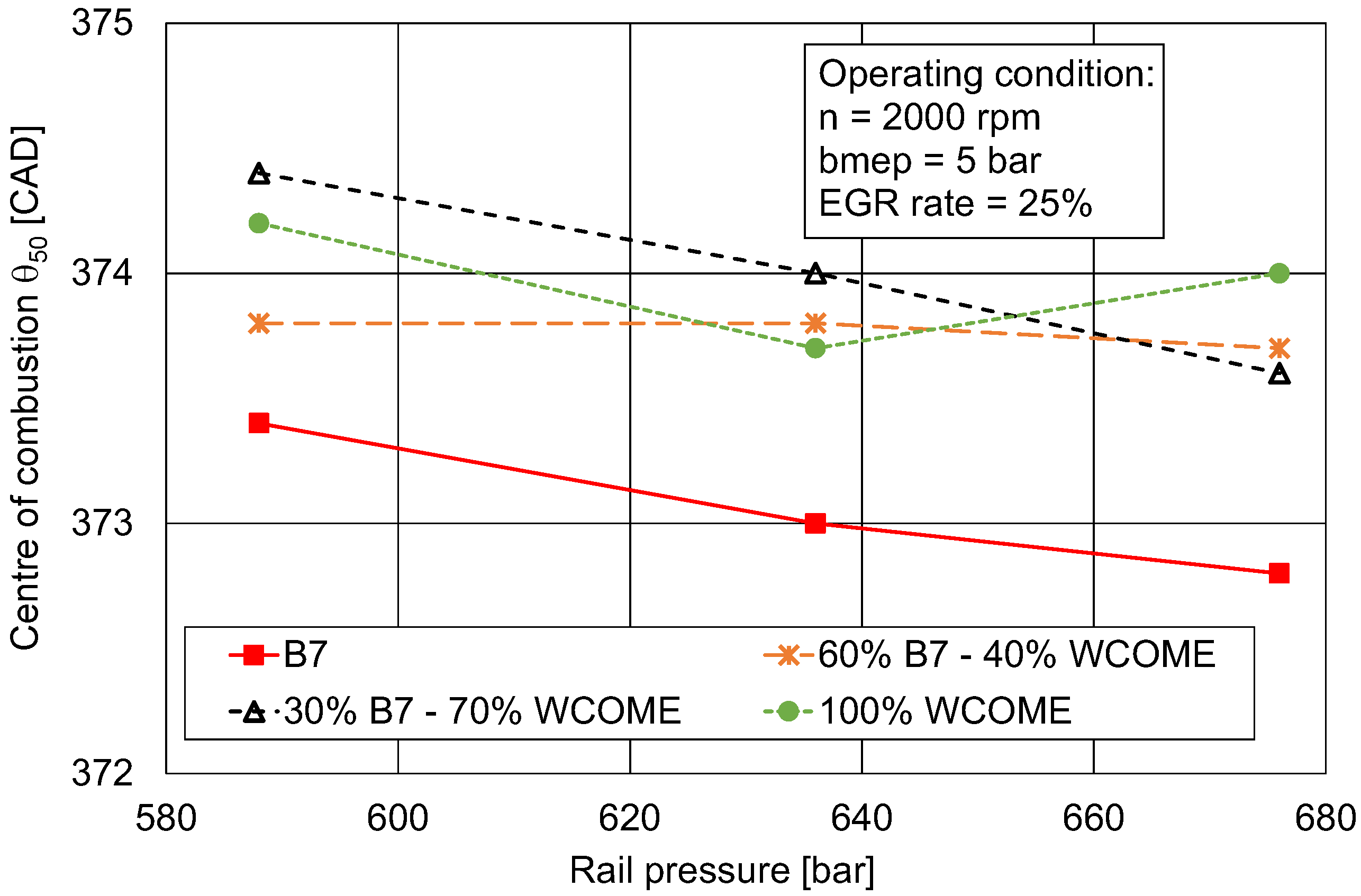

As far as the centre of combustion is concerned (

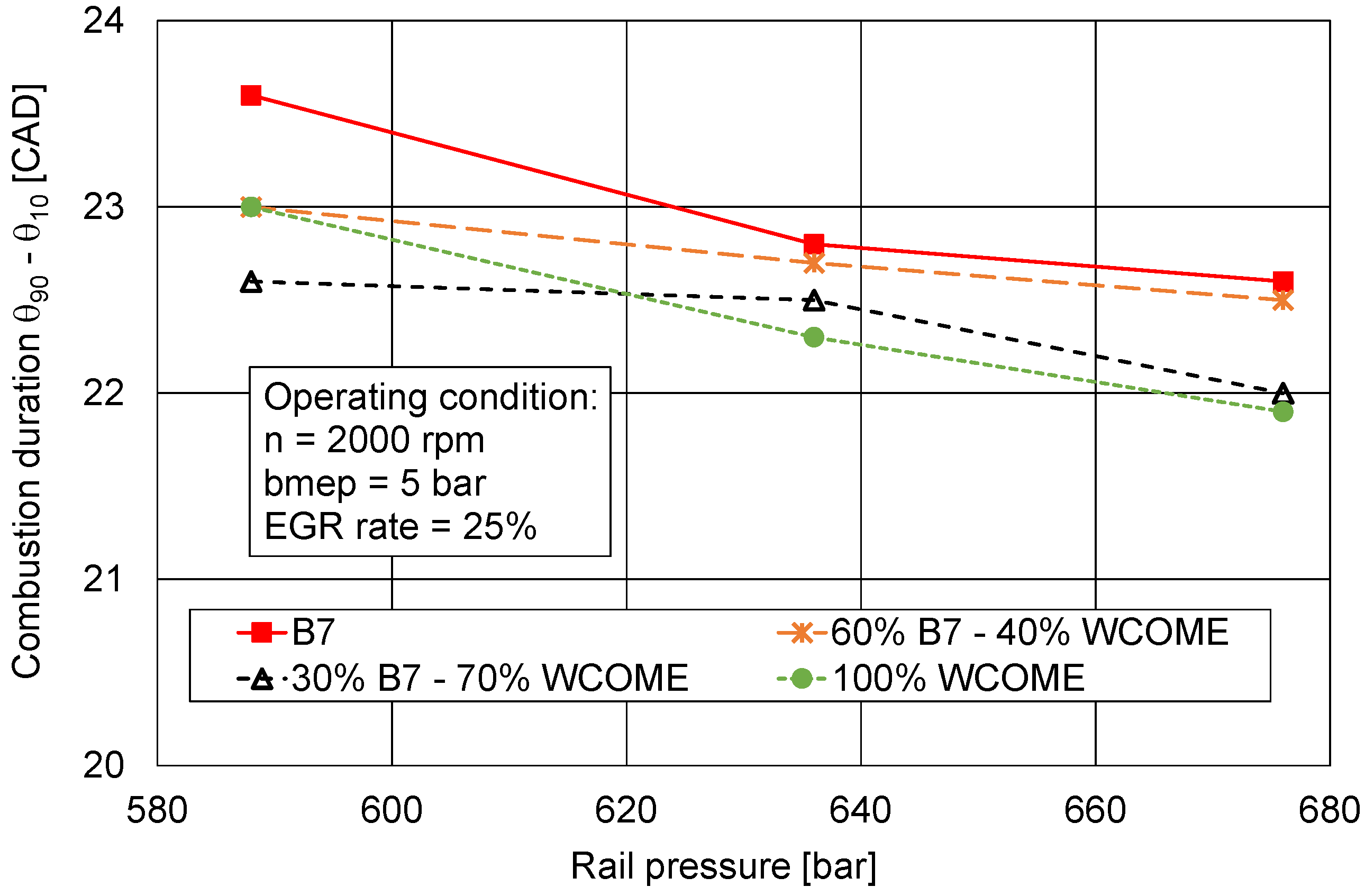

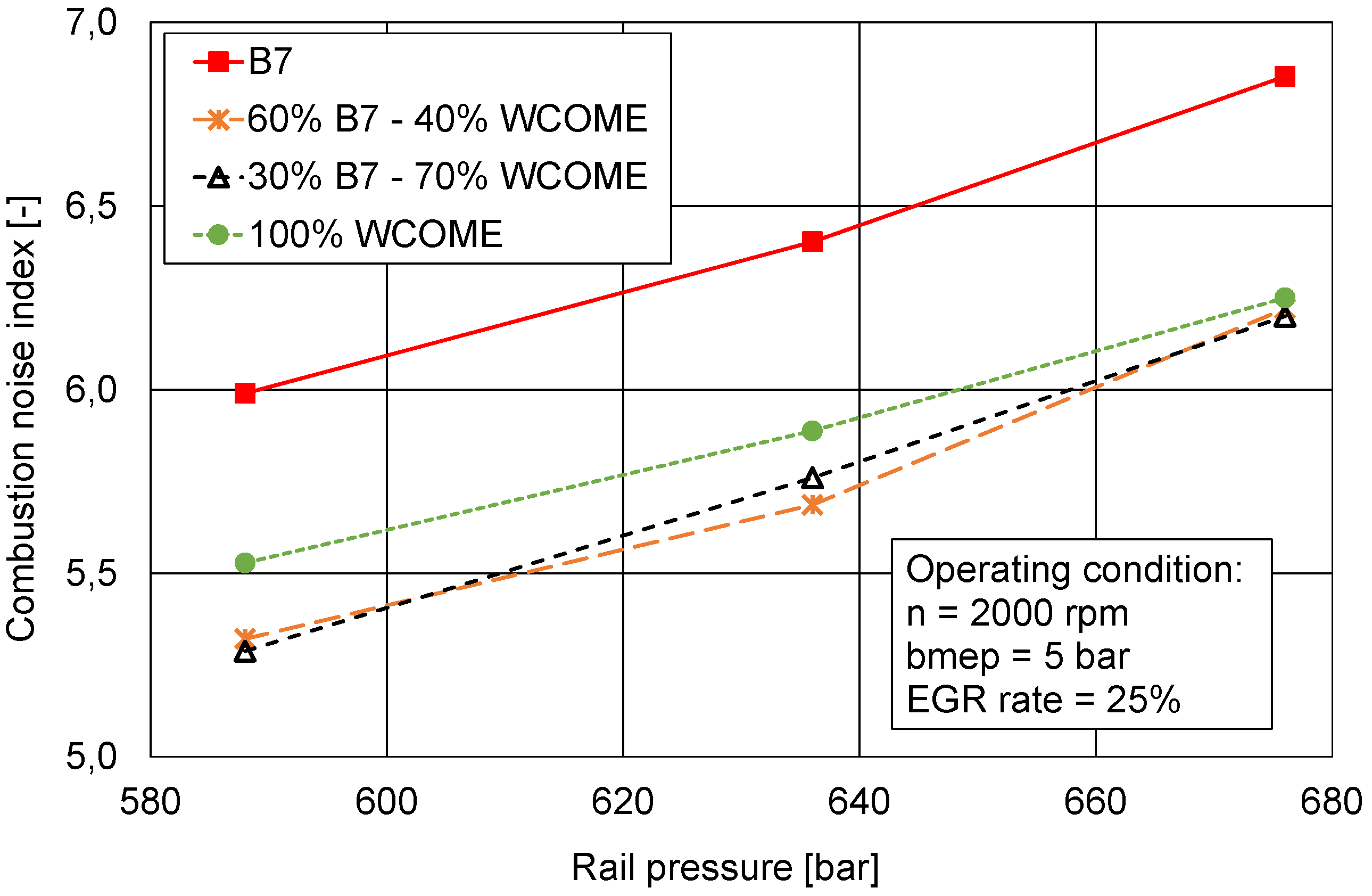

Figure 18), the increase of rail pressure results in a slight reduction in this quantity for all the tested fuels, confirming the influence of this control variable on fuel distribution, mixture formation and combustion development previously described. The same conclusion is valid for the combustion duration, presented in

Figure 19. Trends of combustion noise index are presented in

Figure 20, further illustrating effects related to a higher level of rail pressure. The faster mixture formation and combustion result in higher levels of pressure rise rate, increasing I

n. For all these parameters, the influence of biodiesel shown in

Figure 18,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 is the same outlined in

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13. In fact, at constant operating mode, a slight shift within the expansion stroke is observed for θ

50 for the slower combustion at the start of the process, leading also to decreased values of the combustion noise I

n. Reductions can be detected for θ

90 – θ

10, because of the acceleration caused by the oxygen provided by the biodiesel [

12,

52].

Figure 1.

Scheme of the test rig.

Figure 1.

Scheme of the test rig.

Figure 2.

Example of indicated pressure diagram and pressure first derivative and related parameters.

Figure 2.

Example of indicated pressure diagram and pressure first derivative and related parameters.

Figure 3.

Air-fuel ratio as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 3.

Air-fuel ratio as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 4.

Variable nozzle turbine opening degree as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 4.

Variable nozzle turbine opening degree as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 5.

Engine pressure gradient as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 5.

Engine pressure gradient as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 6.

Brake specific fuel consumption as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 6.

Brake specific fuel consumption as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 7.

Brake thermal efficiency as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 7.

Brake thermal efficiency as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 8.

Brake specific NOX emission as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 8.

Brake specific NOX emission as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 9.

Brake specific soot emission as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 9.

Brake specific soot emission as a function of EGR rate.

Figure 10.

Trends of CoV of maximum pressure controlling EGR rate.

Figure 10.

Trends of CoV of maximum pressure controlling EGR rate.

Figure 11.

Trends of centre of combustion controlling EGR rate.

Figure 11.

Trends of centre of combustion controlling EGR rate.

Figure 12.

Trends of combustion duration controlling EGR rate.

Figure 12.

Trends of combustion duration controlling EGR rate.

Figure 13.

Trends of combustion noise index controlling EGR rate.

Figure 13.

Trends of combustion noise index controlling EGR rate.

Figure 14.

Brake thermal efficiency as a function of rail pressure at the higher EGR rate.

Figure 14.

Brake thermal efficiency as a function of rail pressure at the higher EGR rate.

Figure 15.

Brake specific NOX emission as a function of rail pressure at the higher EGR rate.

Figure 15.

Brake specific NOX emission as a function of rail pressure at the higher EGR rate.

Figure 16.

Brake specific soot emission as a function of rail pressure at the higher EGR rate.

Figure 16.

Brake specific soot emission as a function of rail pressure at the higher EGR rate.

Figure 17.

Trends of CoV of maximum pressure controlling rail pressure.

Figure 17.

Trends of CoV of maximum pressure controlling rail pressure.

Figure 18.

Trends of centre of combustion controlling rail pressure.

Figure 18.

Trends of centre of combustion controlling rail pressure.

Figure 19.

Trends of combustion duration controlling rail pressure.

Figure 19.

Trends of combustion duration controlling rail pressure.

Figure 20.

Trends of combustion noise index controlling rail pressure.

Figure 20.

Trends of combustion noise index controlling rail pressure.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of tested engine.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of tested engine.

| Characteristic |

Value |

| Engine type |

Four-stroke, Diesel |

| Cylinders |

4 in-line |

| Bore [mm] x stroke [mm] |

69.9 x 82 |

| Displacement [cm3] |

1248 |

| Compression ratio |

16.8:1 |

| Valves for cylinder |

4 |

| Maximum Power [kW] |

70 @ 4000 rpm |

| Maximum Torque [Nm] |

200 @ 1500 – 3000 rpm |

| Fuel injection system |

Direct injection, Multijet II common rail with solenoid injectors, maximum pressure 1650 bar |

| Turbocharging system |

Single stage, variable nozzle turbine, intercooler |

| EGR system |

High pressure, cooled |

Table 2.

Measured parameters and instrumentation.

Table 2.

Measured parameters and instrumentation.

| Measured quantity |

Instrument |

Range |

Accuracy |

| Engine speed |

Inductive pick-up |

0 ÷ 5000 rpm |

± 10 rpm |

| Engine torque |

Eddy current dynamometer |

0 ÷ 250 Nm |

± 1.25 Nm |

| Fuel mass flow rate |

AVL 733S dynamic measuring equipment |

0 ÷ 37.5 kg/h |

0.81% for a measured value of 5 g, 0.42% for 10 g, 0.2% for 25 g |

| Air mass flow rate |

Hot wire air flow meter |

0 ÷ 1000 mg/stroke |

± 5 mg/stroke |

| Exhaust smoke |

AVL 415 variable sampling smoke meter |

0 ÷ 10 FSN |

± 0.1 FSN |

| NOX concentration |

Rosemount 951 CLA analyzer |

0 ÷ 250 ppm

0 ÷ 1000 ppm |

± 1.25 ppm

± 5 ppm |

| Turbocharger rotational speed |

Eddy current probe |

200 ÷ 400000 rpm |

36 rpm |

| Temperatures (intake circuit, lubricant, coolant, etc.) |

4-wire RTD |

0 ÷ 350 °C |

0.15 °C + 0.002 × measured value |

| Temperatures (exhaust and EGR circuits) |

K type TC |

0 ÷ 1200 °C (class 2)

|

± 2.5 °C or

± 0.75% × measured value (class 2) |

| Pressures |

Strain gauge |

-1 ÷ 0.6 bar |

< ± 0.2% × full scale |

| In-cylinder pressure |

Kistler 6125B |

0 ÷ 2.5 bar |

< ± 0.5% × full scale |

| Kiag Swiss 5001 charge amplifier |

< ± 1% × full scale |

| Fuel pressure |

Kistler 4067A2000 |

0 ÷ 2000 bar |

< ± 0.5% × full scale |

| Kistler 4618A2 amplifier |

< ± 0.2% × full scale |

Table 3.

Estimated maximum relative uncertainties (in [%]) for brake specific fuel consumption (bsfc), NOX (bsNOX) and soot (bsS) emissions.

Table 3.

Estimated maximum relative uncertainties (in [%]) for brake specific fuel consumption (bsfc), NOX (bsNOX) and soot (bsS) emissions.

| |

Operating condition

ID = n x bmep

[rpm x bar] |

| |

2000 × 2 |

2000 × 5 |

| bsfc |

1.5 |

1.3 |

| bsNOX

|

1.8 |

1.8 |

| bsS |

3.2 |

3.1 |

Table 4.

Properties of fuels and tested blends.

Table 4.

Properties of fuels and tested blends.

| Fuel/Blends |

Density @ 15 °C [g/dm3] |

LHV |

Oxygen content [%] |

Stoichiometric Air-Fuel Ratio |

Cetane Number |

| B7 |

830 |

43 |

- |

14.57 |

52 |

| WCOME |

874 |

37.1 (-13.7%) |

10.9 |

12.55 |

51.9 |

| 60% B7 + 40% WCOME |

843 |

40.6 (-5.5%) |

4.8 |

13.80 |

52 |

| 30% B7 + 70% WCOME |

853 |

38.9 (-9.6%) |

7.9 |

13.41 |

51.9 |

Table 5.

Composition of different biodiesel.

Table 5.

Composition of different biodiesel.

| Fatty acid |

Sunflower oil |

Olive oil |

Waste cooking oil |

| C16:0 Palmitic |

6-7a/6.40b

|

5-13a/11.47b

|

1-30a/6.7c/28.78d/10.54e/6f

|

| C18:0 Stearic |

3-5a

|

1-3a

|

2-6a/1.6c/6.41d/4.02e/0.8f

|

| C18:1 Oleic |

17-29a/17.70b

|

71-75a/74.52b

|

5-53a/18.3c/34.94d/54.74e/54f

|

| C18:2 Linoleic |

58-74a/72.90b

|

10-18a/9.54b

|

2-51a/73.4c/21.19d/28.03e/25.7f

|

Table 6.

Investigation program.

Table 6.

Investigation program.

| Operating mode |

Engine speed [rpm] |

Brake mean effective pressure [bar] |

Excess air ratio [-] |

Rail pressure [bar] |

DCVNT [%] |

| 1 |

2000 |

2 |

6.0 |

470* |

82.0 |

| 2 |

3.2 |

89.0 |

| 3 |

2.8* |

93.0* |

| 4 |

2.4 |

95.0 |

| 5 |

2.4 |

508 |

95.0 |

| 6 |

2.4 |

540 |

95.0 |

| 7 |

2500 |

5 |

6.0 |

588* |

78.0 |

| 8 |

2.2 |

82.0 |

| 9 |

1.8* |

87.4* |

| 10 |

1.65 |

92.0 |

| 11 |

1.65 |

636 |

92.0 |

| 12 |

1.65 |

676 |

92.0 |