Introduction

Alcohol and psychoactive substance misuse is not uncommon among individuals experiencing a first-episode psychosis (FEP), with cannabis consumption being particularly prominent. According to the World Drug Report, 4% of the world's population has used cannabis in the past years [

1] Notably, Canadian youth have been reported to have one of the highest rates of cannabis consumption among their peers worldwide, with up to 50% reported [

2] whereas the other illicit substances, such as cocaine, ecstasy, methamphetamines, hallucinogenic, and heroin, were only 3% [

3]. In recent decades, with drug policy and legislative shifts, cannabis was initially legalised for potential medicinal benefits [

4]. Underpinned by public health concerns, a desire to reduce the availability of illicit cannabis, the risk of harm to youth and regulate its distribution [

4,

5] whilst monitoring the impact of safer access to cannabis and potential harms including mental health outcomes. Since Canada legalised cannabis in 2018, there has been a noticeable increase in the potency of cannabis products. Many commercially available items now have much higher levels of THC compared to strains before legalization. For instance, the concentration of THC in legal cannabis flowers has risen from approximately 15% to 25% or even higher in some instances. This trend presents an opportunity to address potential public health concerns, particularly regarding the effects of higher-potency products on consumers. By focusing on education and responsible use, especially for first-time users and teenagers, we can work together to minimize the risk of negative outcomes such as cannabis use disorder and mental health challenges (Mahamad et al 2020) [

5].

According to the 2021/2022 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol, and Drugs Survey (CSTADS), Cannabis use is prevalent among students, with 18% of students in grades 7-12 reporting use in the past year [

2]. In Ontario, 17% of students in grades 7-12 report using cannabis within the past year, with 41% reporting that it is "fairly easy" or "very easy" to obtain the drug. [

6]. Notably, the age of exposure to cannabis use, consequent risk of harmful cannabis use and the development of cannabis use disorders (CUD) appear younger than alcohol or other substance use disorders, indicating a typical pattern [

7,

8].

According to epidemiological research, teenagers and young adults who use high-potency cannabis, particularly products with higher THC concentrations, are at a higher risk of suffering mental health concerns, including increased rates of anxiety, depression, and psychosis [

9,

10].

The use of cannabis has increased in Ontario associated with cannabis-related psychosis reported around 25-30%, especially among those 18-23 years who visited the emergency department [

10,

11]. Early cannabis users had a 50% increased risk of developing schizophrenia [

13,

14]. These findings are further supported by a British study, which reported a prevalence of cannabis use in patients with first-episode psychosis at 64% [

15], while in Ontario, Canada, 60% of patients receiving treatment from early psychosis intervention services were found to use cannabis [

16].

Differentiating first-episode substance-induced psychosis from primary psychotic disorders is essential, as individuals with current cannabis use disorder were 15 times more likely to have a substance-induced psychosis than those with a family history of psychosis, who were more prone to primary psychotic disorders [

17]. According to Ferraro et al. (2013), persons who use cannabis and have a first episode psychosis (FEP) have a greater premorbid level of functioning, particularly in terms of cognitive ability, than those who have never used cannabis and suffer an FEP. This study suggests that cannabis users may have a higher cognitive baseline before the onset of psychosis, but this does not imply that cannabis usage is protective against the development of psychosis [

18].

Given the high rate of cannabis use among Canadian youth and young adults, interventions targeting at-risk individuals have become an integral component of Early Psychosis Intervention (EPI) services [

19,

21]. EPI programs aim to provide timely and comprehensive support to individuals experiencing their first episode of psychosis to improve outcomes and minimize the long-term impact of the condition [

20,

21,

22]. Targeting at-risk individuals is anticipated to allow EPI services to intervene early and reduce the progression of mental health disorders, including those potentially related to substance use, such as cannabis-induced psychosis [

23]. With cannabis use being one of the few modifiable risk factors for psychosis [

23], its reduction is critical for EPI services to be effective. Consequently, our study aimed to ascertain the self-reported prevalence of cannabis use among 14-35-year-old individuals attending an EPI program in Southeast Ontario. By examining these aspects, we seek to contribute to understanding cannabis use patterns and its potential impact on psychosis among this vulnerable population.

Methods

Study Population

This study meticulously conducted a cross-sectional clinical record review involving a cohort of 116 individuals who were participants in the Southeast Ontario Early Psychosis Intervention (EPI) program, known as Heads Up!, located in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. The review covered an extensive period from 2016 to 2019, employing a consecutive sampling technique to ensure a representative sample of the population served by the program.

The EPI program is specifically designed to provide comprehensive support and intervention for individuals aged between 14 and 35 years who are undergoing their first episode of psychosis and current cannabis use at the time of program enrolment. These individuals may be experiencing a range of psychotic symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking, and impairments in functioning. Furthermore, the program targets those who have not previously received any form of treatment for a psychotic illness within the region, fulfilling the necessary provincial criteria for eligibility. The aim is to facilitate early intervention and promote optimal recovery outcomes for young people facing these significant mental health challenges.

Sociodemographic Measures

The data collection process involved extracting demographic information, including age, all genders, and educational status, from the contemporaneous clinical records. Additionally, data on self-reported cannabis use and concurrent use of other drugs were gathered during the comprehensive initial assessment.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to present and summarize the demographic characteristics, cannabis use (yes/no), and other relevant variables. Furthermore, inferential statistics were employed to explore potential associations between cannabis use and demographic factors. Statistical analyses were performed to examine the prevalence of cannabis use, its correlation and association with alcohol and other substance use, and the association with psychotic disorders.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

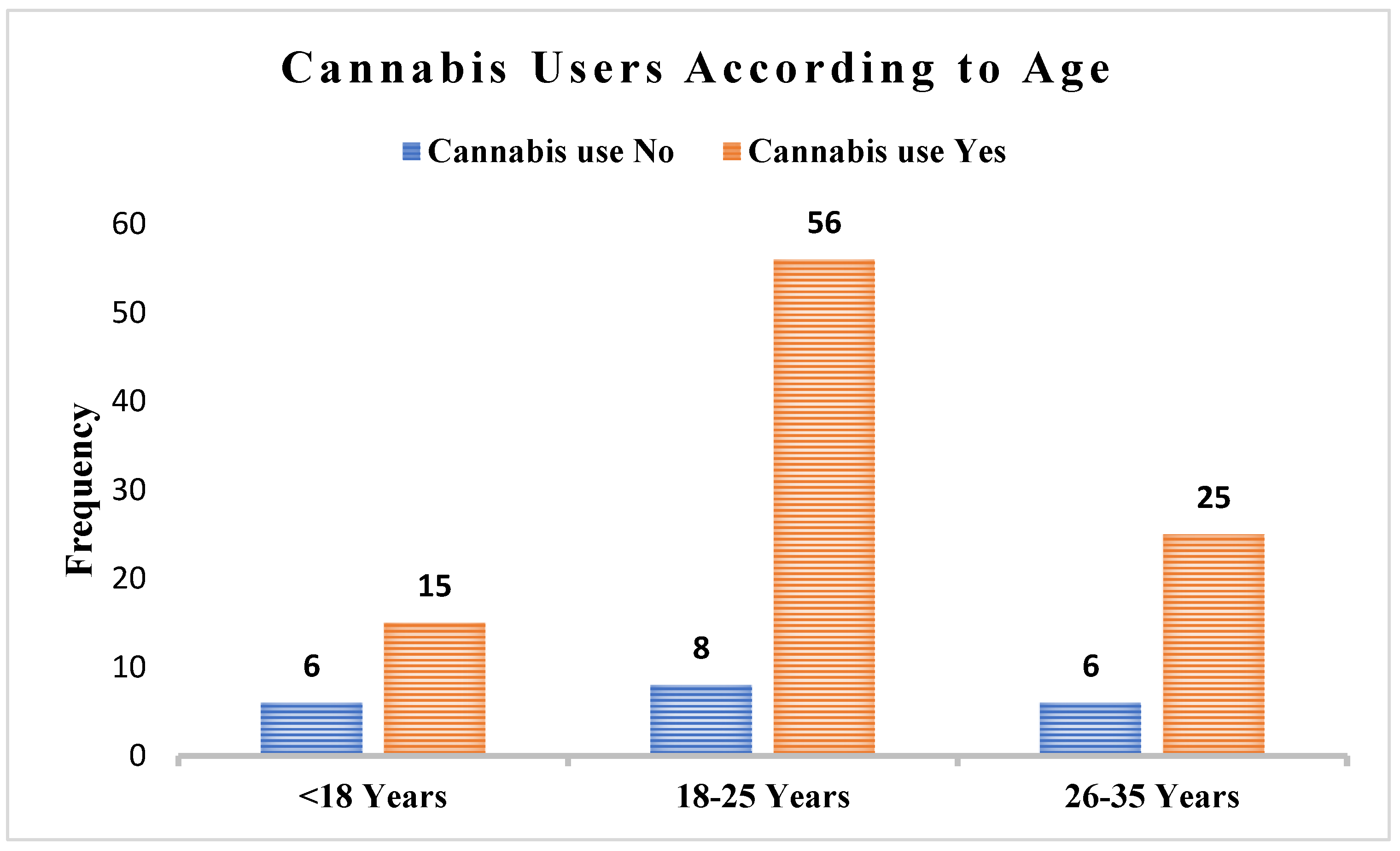

Cannabis use was significantly prevalent among men indicating 71.9%, compared to 60.0% of non-users. Conversely, the proportion of female among cannabis users was lower (28.1%) and the proportion of non-users was higher (40.0%) (P-value > 0.05). The data show that the majority of cannabis users were in the 18-25 age group, accounting for 58.3% of users. This suggests that young adults were the most common age group for cannabis use. In contrast, a significant proportion of non-users were under the age of 18 (30.0%), which was significantly higher than the 15.6% of cannabis users in this age group. (P-value > 0.05). This discrepancy could be due to legal and developmental factors influencing cannabis use among younger people. In terms of education, a significant difference was observed. None of the cannabis users had only secondary education, whereas 10% of non-users did (p=0.004). Among cannabis users, 18.4% had completed high school, compared to 81.5% of non-users, and 18.1% of cannabis users had completed graduation, compared to 81.1% of non-users. Only 2 participants reported post-graduation education, both of whom were cannabis users. These results highlight significant differences in educational attainment between cannabis users and non-users, particularly in secondary education. (

Table 1,

Figure 1).

Association Between Psychiatric Diagnosis and Cannabis Use

Among cannabis users, 43(44.8%) had a diagnosis of psychosis, 54(56.3%) with substance-induced psychosis (SIP), 14(14.6%) have substance use disorder, 19(19.8) had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), 24(25.0%) with anxiety disorder, 18(18.8%) have depression, only 8(8.3%) had Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and 133(13.5) had bipolar disorder. (

Table 2). Among cannabis users diagnosed with psychosis, a significant proportion had substance-induced psychosis (p-value < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study aimed to explore the prevalence of cannabis use among individuals attending an EPI program in Southeast Ontario and to assess the burden of cannabis use in a specific geographical region of Canada among YAY attending an EPI service. The findings from this study offer valuable insights into the prevalence of cannabis use, its associations with other substances, and its potential impact on mental health outcomes among this vulnerable population of youth and young adults at a critical developmental stage.

The prevalence of cannabis use among the study participants was found to be substantial, with 82.8% of individuals self-reporting cannabis use during the initial assessment. This prevalence is notably higher than that observed in age-matched peers in the Canadian population, as evidenced by data from the Canadian Tobacco Alcohol and Drugs Survey [

3]. The prevalence of cannabis use among younger individuals is notably higher, and this discrepancy can largely be attributed to a combination of legal and developmental factors. Legal frameworks surrounding cannabis vary significantly across regions, with some areas decriminalizing or legalizing its use, which may lead to increased access and acceptance among youth. Additionally, developmental factors, including peer influence, social normalization, and the curiosity typical of younger age groups, contribute to the greater likelihood of cannabis consumption during adolescence and early adulthood. Understanding these influences is crucial for addressing public health concerns and developing effective educational and prevention strategies [

23,

24].

Another survey on Cannabis use is notably widespread in British Columbia (BC), with approximately 1.84 million people in the province having tried cannabis at least once, according to the 2004 Canadian Addiction Survey (CAS). BC residents exhibit a more permissive attitude toward cannabis compared to the rest of Canada, with only 42% believing that cannabis use should be illegal. [

25]

Moreover, the study identified a male predominance in cannabis use, with males being more than twice as likely to report cannabis use as females. This is similar to another study conducted in Israel [

26]. A scoping review by Hemsing and Greaves (2020) also asserts that men and boys generally have a higher preponderance of cannabis use [

25]. In the present study, the peak age of cannabis use was observed at 21 years, during early adulthood and a critical period of brain maturation up to the age of 25 years. Other studies show that the median age of first use is around 14 years [

23,

25]. This may be an age of experimentation among some youth, and the frequency of use continues to increase with age.

However, this was not the case in another study that surveyed drivers. In this instance, self-reporting had low sensitivity but high specificity [

26]. A scoping review of studies conducted among women of reproductive age showed that self-reporting was only reliable among participants with a prior known history of cannabis use [

27].

In this study, a significant co-occurrence or association between cannabis use and psychosis and SIP diagnoses was evident, signifying the potential role of cannabis in the development exacerbation or perpetuation of these psychiatric conditions. Ongoing use of cannabis is also a negative prognostic factor in the trajectory of psychosis. Previous research has shown that cannabis use is associated with an early onset and increased frequency of psychotic, mood, anxiety, and personality disorders [

28,

29,

30]. Most mental illnesses may also be associated with higher reward-seeking states, prompting affected individuals to use cannabis and other substances more frequently and more heavily as a form of self-medication [

31].

The current study's findings underscore the importance of screening, identification and cannabis-related therapeutic interventions with a harm reduction or less harmful use focus, particularly in youth and young adults already at heightened risk attending an EPI program [

32]. This requires specific training in comorbid or concurrent disorders to effectively deliver this care and we would recommend such training as a part of working in EPI service delivery. The co-occurrence of cannabis with other substances and its potential impact on mental health outcomes necessitate comprehensive and integrated approaches to address both substance use and mental health simultaneously.

The descriptive nature of the study from a service with a primary focus on psychosis limits the interpretation of diagnosis in this population. Longitudinal studies are required to understand better the temporal relationships between cannabis use and psychosis, as well as the naturalistic history of therapeutic interventions on the course and severity of illness. Moreover, the study with a relatively small sample size was confined to a specific geographical region, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future research should involve more diverse and representative samples to strengthen the external validity of the results. Most data on cannabis use are based on self-report with significant limitations such as recall bias, the lack of object verification of the substance consumed and confounding with other substance use. This approach may lead to either denial or underreporting of cannabis use, particularly in substance-using adolescents who fear personal consequences, and legal sanctions or fail to recognize their cannabis use as problematic. Failure to establish the presence of cannabis use may limit the comprehensive range of therapeutic interventions offered in an EPI service and the illness trajectory. However, the primary objective to assess the prevalence of cannabis use in a disaggregated population in Canada was met.

Conclusion

The study highlights a significant prevalence of cannabis use among youth and young adults attending an Early Psychosis Intervention program in Southeast Ontario. This finding underscores the need for targeted interventions to address cannabis use in this vulnerable population. The association between cannabis use and psychiatric diagnoses, particularly psychotic disorders including substance-induced psychosis and schizophrenia, as well as Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD), emphasizes the importance of considering cannabis in mental health interventions. Healthcare providers in early intervention programs should assess cannabis use and provide appropriate interventions to minimize potential short-term and lifelong outcomes. Further research is required to understand the underlying causes of this association and develop effective interventions to reduce harmful cannabis use among young adults with psychosis.

Ethical Considerations

The study adhered to all ethical guidelines and principles. The research was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by The Queen's University Health Sciences & Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (HSREB#6025629) on January 14, 2019.

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Funding

This research received no specific funding support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that could have influenced the design, execution, or reporting of this research.

References

- UNODC World Drug Report 2022. 2022 Available from: www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.

- Canadian Cannabis Survey 2022: Summary - Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/research-data/canadian-cannabis-survey-2022-summary.

- Mehra, V.M.; Keethakumar, A.; Bohr, Y.M.; Abdullah, P.; Tamim, H. The association between alcohol, marijuana, illegal drug use and current use of E-cigarette among youth and young adults in Canada: results from Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey 2017. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, J.L.; Watson, T.M.; Owusu-Bempah, A.; Hyshka, E.; Wells, S.; Robinson, M.; Rueda, S. Overpoliced and underrepresented: perspectives on cannabis legalization from members of racialized communities in Canada. Contemporary drug problems 2023, 50(1), 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamad S, Wadsworth E, Rynard V, Goodman S, Hammond DJD, review a.. Availability, retail price and potency of legal and illegal cannabis in Canada after recreational cannabis legalisation. 3: 2020, 39, 2020.

- Boak, A.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Hamilton, H.A. The well-being of Ontario Students: Finding from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey (OSDUHS). Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Secades-Villa, R.; Garcia-Rodríguez, O.; Jin, C.J.; Wang, S.; Blanco, C. Probability and predictors of the cannabis gateway effect: a national study. International Journal of Drug Policy 2015, 26(2), 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipari, R.N.; Hedden, S.L.; Hughes, A. Substance use and mental health estimates from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: overview of findings. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ishrat, S.; Levey, D.F.; Gelernter, J.; Ebmeier, K.; Topiwala, A. Association between cannabis use and brain structure and function: an observational and Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ Ment Health. 2024, 27(1).

- Myran, D.T.; Pugliese, M.; Roberts, R.L.; Solmi, M.; Perlman, C.M.; Fiedorowicz, J.; Anderson, K.K. Association between non-medical cannabis legalization and emergency department visits for cannabis-induced psychosis. Molecular psychiatry 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayonrinde, O.A. Cannabis and psychosis: revisiting a nineteenth-century study of ‘Indian Hemp and Insanity’in Colonial British India. Psychological medicine 2020, 50(7), 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myran, D.T.; Harrison, L.D.; Pugliese, M.; Solmi, M.; Anderson, K.K.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Tanuseputro, P. Transition to Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder Following Emergency Department Visits Due to Substance Use With and Without Psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Marconi, A.; Di Forti, M.; Lewis, C.M.; Murray, R.M.; Vassos, E. Meta-analysis of the association between the level of cannabis use and risk of psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2016, 42(5), 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Forti, M.; Quattrone, D.; Freeman, T.P.; Tripoli, G.; Gayer-Anderson, C.; Quigley, H.; van der Ven, E. The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): a multicentre case-control study. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6(5), 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.R.; Mutsatsa, S.H.; Hutton, S.B.; Watt, H.C.; Joyce, E.M. Comorbid substance use and age at onset of schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2006, 188(3), 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archie, S.; Rush, B.R.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Norman, R.; Malla, A.; Roy, P.; Zipursky, R.B. Substance use and abuse in first-episode psychosis: prevalence before and after early intervention. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2007, 33(6), 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S.; Hides, L.; Philips, L.; Proctor, D.; Lubman, D.I. Differentiating first episode substance induced and primary psychotic disorders with concurrent substance use in young people. Schizophrenia Research 2012, 136(1-3), 110-115.

- Ferraro, L.; Russo, M.; O'Connor, J.; Wiffen, B.D.; Falcone, M.A.; Sideli, L.; Gardner-Sood, P.; Stilo, S.; Trotta, A.; Dazzan, P.; Mondelli, V. Cannabis users have higher premorbid IQ than other patients with first-onset psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2013, 50, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, H.V.; Hindocha, C.; Morgan, C.J.; Shaban, N.; Das, R.K.; Freeman, T.P. Which biological and self-report measures of cannabis use predict cannabis dependency and acute psychotic-like effects? Psychological medicine 2019, 49(9), 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nolin, M.; Malla, A.; Tibbo, P.; Norman, R.; Abdel-Baki, A. Early intervention for psychosis in Canada: what is the state of affairs? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2016, 61(3), 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S.; Jordan, G.; MacDonald, K.; Joober, R.; Malla, A. Early intervention for psychosis: a Canadian perspective. The Journal of nervous and mental disease 2015, 203(5), 356–364. [Google Scholar]

- Correll, C.U.; Galling, B.; Pawar, A.; Krivko, A.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Kane, J.M. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA psychiatry 2018, 75(6), 555–565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Gutiérrez T, Fernandez-Castilla B, Barbeito S, González-Pinto A, Becerra-García JA, Calvo A. Cannabis use and nonuse in patients with first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing neurocognitive functioning. European psychiatry. 2020, 63, e6.

- Cox, C. The Canadian Cannabis Act legalised and regulated recreational cannabis use in 2018. Health Policy. 2018, 122, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Hemsing, N. , & Greaves, L. Gender norms, roles and relations and cannabis-use patterns: a scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17(3), 947.

- der Linden, T. V. , Silverans, P., & Verstraete, A. G. Comparison between self-report of cannabis use and toxicological detection of THC/THCCOOH in blood and THC in oral fluid in drivers in a roadside survey. Drug testing and analysis 2014, 6(1-2), 137-142.

- Skelton, K.R.; Donahue, E.; Benjamin-Neelon, S.E. Validity of self-report measures of cannabis use compared to biological samples among women of reproductive age: a scoping review. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 2022, 22(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, B.W.; Khokhar, J.Y. Cannabis use and mental illness: understanding circuit dysfunction through preclinical models. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021, 12, 597725. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M.S. Is there a link between marijuana use and the risk of having psychiatric disorders? Semergen 2017, 43(4), 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin, D.; Walsh, C. Cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and comorbid psychiatric illness: A narrative review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 10(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Urits, I.; Gress, K.; Charipova, K.; Li, N.; Berger, A.A.; Cornett, E.M.; Viswanath, O. Cannabis use and its association with psychological disorders. Psychopharmacology bulletin 2020, 50(2), 56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischer, B.; Robinson, T.; Bullen, C.; Curran, V.; Jutras-Aswad, D.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Hall, W. Lower-Risk Cannabis Use Guidelines (LRCUG) for reducing health harms from non-medical cannabis use: A comprehensive evidence and recommendations update. International journal of drug policy 2022, 99, 103381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).