1. Introduction

Considered as a basic component of human intelligence, language is very important for our cognitive capacity. In terms of vocabulary, poetry stands out as a polished and sophisticated kind of artistic expression. Poetry transcends national boundaries, countries, and cultural variety to be always popular and significantly influences the progress of human society [

1]. The first form of literary expression within the Arabic language is poetry. Arab self-identity, collective past, and future aspirations have always found great expression in Arabic poetry. Common classifications for Arabic poetry are classical and contemporary ones [

2]. Most of their research on Arabic prosody—also known as Arud—has been on morphology and phonetics. It has been continuing for some years. Examining meters in poetry helps us ascertain whether a certain piece of work features broken or sound meters [

3].

Modern and traditional Arabic respectively utilize long and short vowels. Diacritics mark the short vowels in written language; the long vowels are shown in their whole form [

4]. In the eighth century, renowned philologists Al-Farahidi researched ancient Arabic poetry utilizing meters [

5]. The metric structure of a word consists of short and lengthy syllables. The classical Arabic poetry involves sixteen meters. Arabic prosody makes use of several often-used terms like these:

Tafilah: Each distinct foot.

Bayt: A poem with single line including a pair of half verses.

Sadr: The initial segment of the half-verse.

Ajuz: The subsequent segment of the half-verse.

Arud: The last segment of Sadr.

Darb: The last segment of Ajuz.

Because of the variety and complexity of the Arabic language, the categorization of Arabic poetry is a difficult chore requiring sophisticated natural language processing (NLP) methods [

6]. The linguistic complexity of Arabic poetry, involving its morphology, semantics, and syntax, remains beyond conventional rule-based and statistical techniques.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has advanced significantly over the past several years toward ever-increasing relevance and applicability. Deep learning (DL) and transformer-based models have let academics make major progress in text categorization, sentiment analysis, and other NLP chores. Including these contemporary designs in Arabic poetry classification offers a good path for better comprehension and accuracy [

7,

8,

9].

Transformer models have profoundly transformed the field of NLP since its introduction in the 2017 paper "Attention is All You Need" [

10]. These approaches handle incoming input concurrently utilizing self-attention techniques, therefore allowing the capture of long-term dependency and associated contexts inside text. Many advanced NLP applications, including text classification, now use transformers as a fundamental building piece. Recent studies reveal that transformer models outperform conventional ML methods in the scope of text categorization challenges. Comparative investigation showed that the text classification across multiple domains, improved accuracy in updated Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) models [

11,

12].

In this study, we employed a public dataset for Arabic meter classification, MetRec [

13], and evaluated the data with different transformers and DL models. We utilized BERT base Arabic (AraBERT), Arabic Efficiently Learning an Encoder that Classifies Token Replacements Accurately (AraELECTRA), Multi-dialect Arabic BERT (MARBERT), modern Arabic BERT (ARBERT), Computational Approaches to Modeling Arabic BERT (CAMeLBERT), and Arabic-BERT models for meter classification. Apart from transformer-based models, DL architectures such as Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) and Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Units (BiGRU) models were also employed. The BiLSTM and BiGRU networks record long-range relationships in sequential data. These designs enable the categorization model to learn both spatial and contextual information, thus fitting the intricate structure of Arabic poetry.

We also analyzed feature significance and model efficacy utilizing the Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) interpretability technique. The findings of the proposed study offer insightful analysis of the appropriateness of several architectures for processing Arabic poetry, hence furthering the evolution of more efficient NLP models for the Arabic language.

The major contributions of the study are as follows:

The study compares and evaluates the performance of different pretrained transformer models such as Arabic-BERT, AraBERT, MARBERT, AraELECTRA, CAMeLBERT, and ARBERT with BiLSTM, and BiGRU DL models.

The study evaluates the half-verse poem and tunes the model with different hidden layers for the DL models and batch sizes for the transformer models.

Different encoding methods were employed in this study such as pretrained tokenizer (WordPiece, and SentencePiece) for transformer models and character-level encoding for DL models.

Using LIME, the study investigates model behavior and feature significance to clarify the model's decision-making procedures.

This study opens the path for future developments and helps the expanding area of Arabic NLP by assessing the interpretability and applicability methods for poetry categorization.

The subsequent sections of this work are organized as follows:

Section 2 presents an extensive literature overview of transformer models and deep learning methodologies.

Section 3 outlines the technique and specifies the model architecture.

Section 4 discusses the experimental results, succeeded by a comprehensive discussion in

Section 5. It also explores prospective areas for further research. Ultimately,

Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review

Talghalit et al., [

14] proposed a strong method based on contextual semantic embeddings and a transformer model for Arabic biomedical searches. Preprocessing Arabic biomedical text, creating vector representations that capture spatial and semantic knowledge, and fine-tuning BERT, AraBERT, Biomedical BERT, the robustly optimized BERT technique (RoBERTa), and Distilled BERT using a designated Arabic biomedical dataset constitute part of the procedures. With an F1-score of 93.35% and an accuracy of 93.31%, the suggested approach essentially groups biomedical research into known categories. Notwithstanding these positive results, the authors draw attention to many study limitations including the complex morphology of the language and the absence of specific datasets for Arabic biomedical text classification. They underline the need for contextual semantic embeddings and more datasets to improve the performance of transformer models in this domain and thus develop NLP applications in Arabic biomedical settings.

Combining AraBERT comprehension with a long short-term memory (LSTM) for sequence modeling, a sentiment analysis model is proposed in a work by Alosaimi [

15]. On four Arabic benchmark datasets, the performance of the model is assessed against conventional ML and DL methods employing several vectorizing strategies. In the work by Al-Onazi [

16], the meter classification was implemented using the Hawks optimization method with LSTM and convolutional network model on the MetRec dataset. The accuracy reached 98% while the precision and recall were 86.5.

In sentiment analysis, ensemble learning, which combines many models to improve classification accuracy, has become a powerful method. Combining many deep learning architectures has been demonstrated in studies to enhance sentiment classification performance above single models [

17,

18]. Experimental findings show notable accuracy increases, therefore underlining the possibilities of models based on transformers for Arabic sentiment assessment. Another study by Zhou employed a convolutional network and LSTM model for text classification [

19]. The convolutional network model captures local textual features while LSTM captures complete information.

Arabic-language version of Generative Pre-trained Transformer-2 (AraGPT-2) meant to provide new text samples improving Arabic text classification. The three components of the method described in Refai's [

20] work were using similarity measures to assess sentence quality, generating improved Arabic text with AraGPT-2, and assessing sentiment classification performance with the AraBERT model. Common in Arabic datasets, they addressed the challenges given by class imbalance in sentiment classification tasks.

The research by Al Deen [

21] investigates Arabic Natural Language Inference using transformer models, AraBERT and RoBERTa, and a novel pretraining method combining Named Entity Recognition. Conflicts and entailments may be found by using a specific dataset derived from publicly accessible resources and linguistically informed pretraining providing semantic understanding for models. AraBERT, with 88.1% accuracy, beats the RoBERTa model when boosted with language expertise. In the work by Qarah [

22], a linguistic model for Arabic poetry analysis, Arabic poetry processing with BERT, was presented. Pretrained from scratch on an extensive corpus of Arabic poetry, this employs BERT architecture. The model provides 768 hidden layers, 10 encoder layers, and 12 attention heads per layer. The 50,000-word vocabulary catches a broad range of Arabic poetry forms and idioms.

The categorization of Arabic news articles is proposed to be enhanced by a hybrid methodology that integrates deep learning with text representation approaches [

9]. After text cleaning, tokenization, lemmatization, and data augmentation—a whole preparation process—a proprietary attention embedding layer logs contextual associations in the text. With data augmentation, the model beats the state-of-the-art Arabic language model AraBERTv2 in classification accuracy to reach 97.69% [

23]. In a work by Alshammari [

24], the authors offer a novel AI text classifier primarily geared to handle the particular challenges in Arabic identification of AI-generated texts. Using two independent datasets, the method consists of optimizing two transformer models: Cross-lingual Language Model and AraELECTRA [

25]. With an 81% accuracy, the proposed models beat current AI detectors. The CAMeLBERT model was trained on an Arabic poetry dataset and achieved a performance of 80.9% accuracy [

26].

Although BERT has been somewhat popular in NLP, the study [

27,

28,

29] underlines that its usage of Arabic text classification is still rather rare. Particularly due to their training in more comprehensive Arabic corpora, the results demonstrate that models specially suited for Arabic, notably CAMeLBERT, AraBERT, and MARBERT, are particularly successful. This extensive research offers future possibilities to solve current constraints and improve the effectiveness of NLP usage scenarios in the Arabic language in addition to an intriguing analysis of the present situation of Arabic text categorization using BERT.

3. Materials and Methods

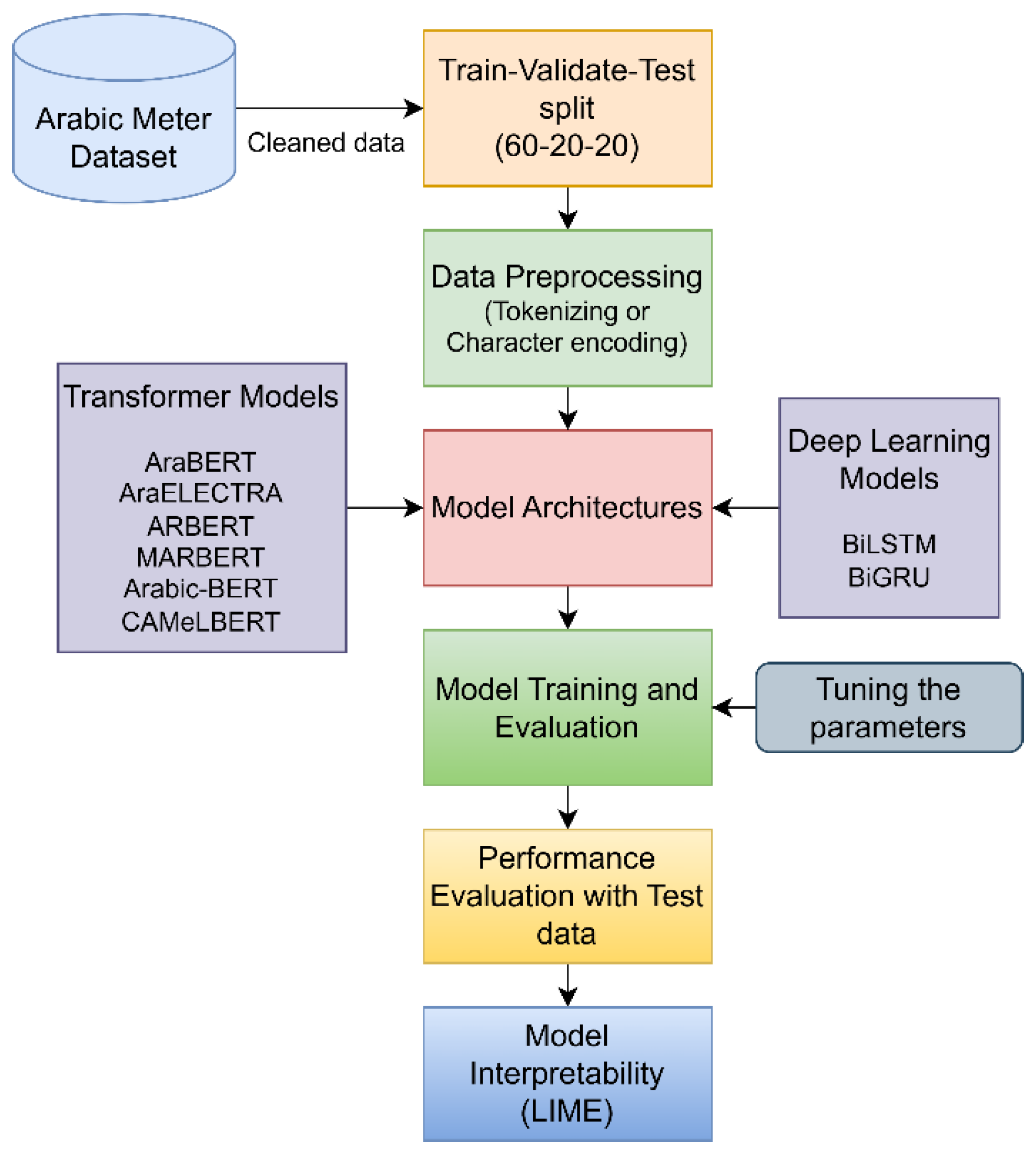

The proposed study consists of phases such as data preprocessing, splitting to train and test, implementing the model, evaluating the model on different parameters, testing the model, and LIME interpretability for the model. The workflow is described in

Figure 1.

3.1. Dataset

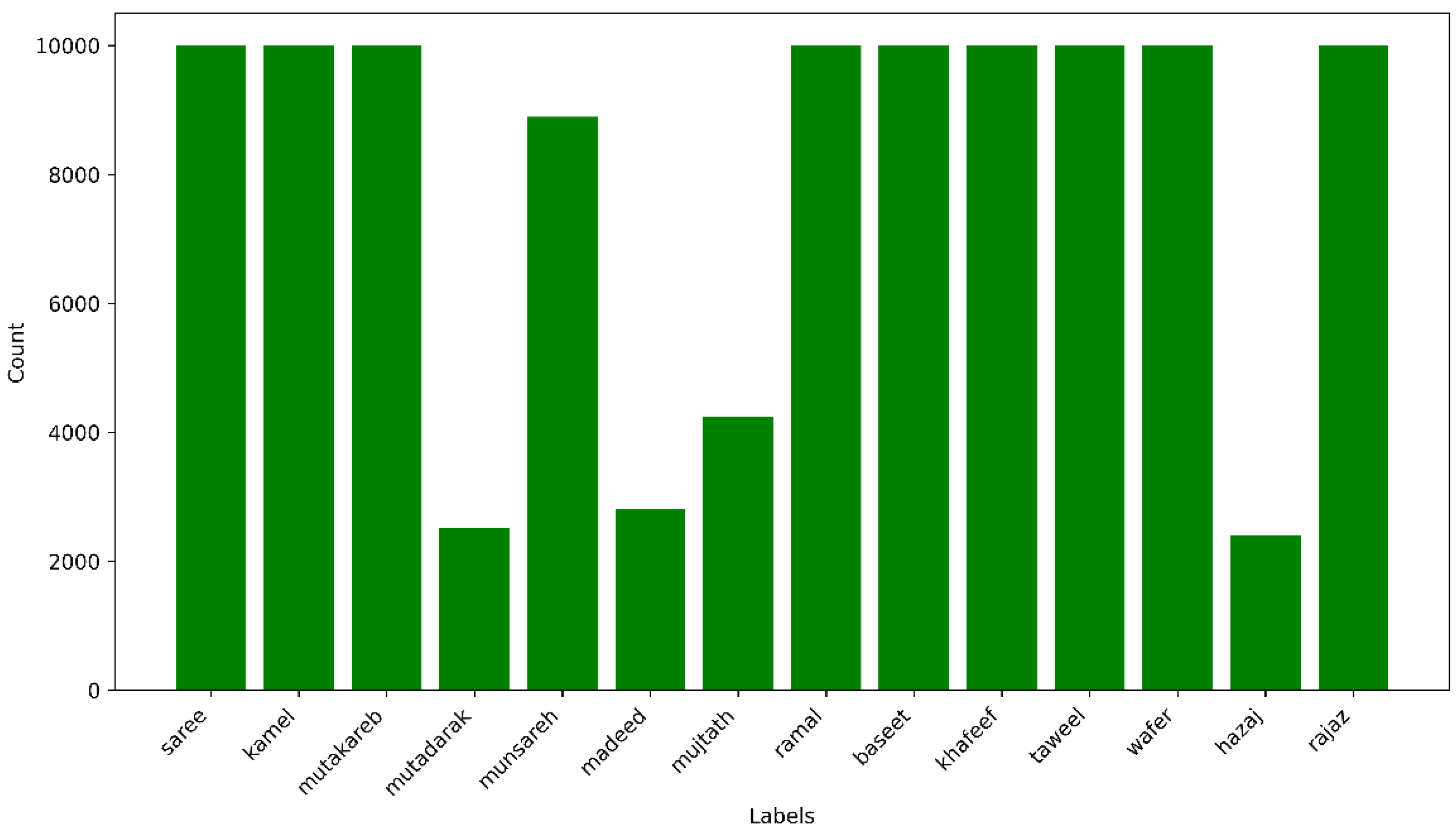

Arabic poetry dataset, MetRec, with 55,440 verses and 14 meters [

30] is the one used in this work. The symbol ‘#’ marks the separation between the left and right verses. The left and right verses are vertically concatenated to produce half-verse data. Therefore, the total number of half-verses is 110,880, as depicted in

Figure 2.

Figure 3 illustrates the word cloud from this dataset.

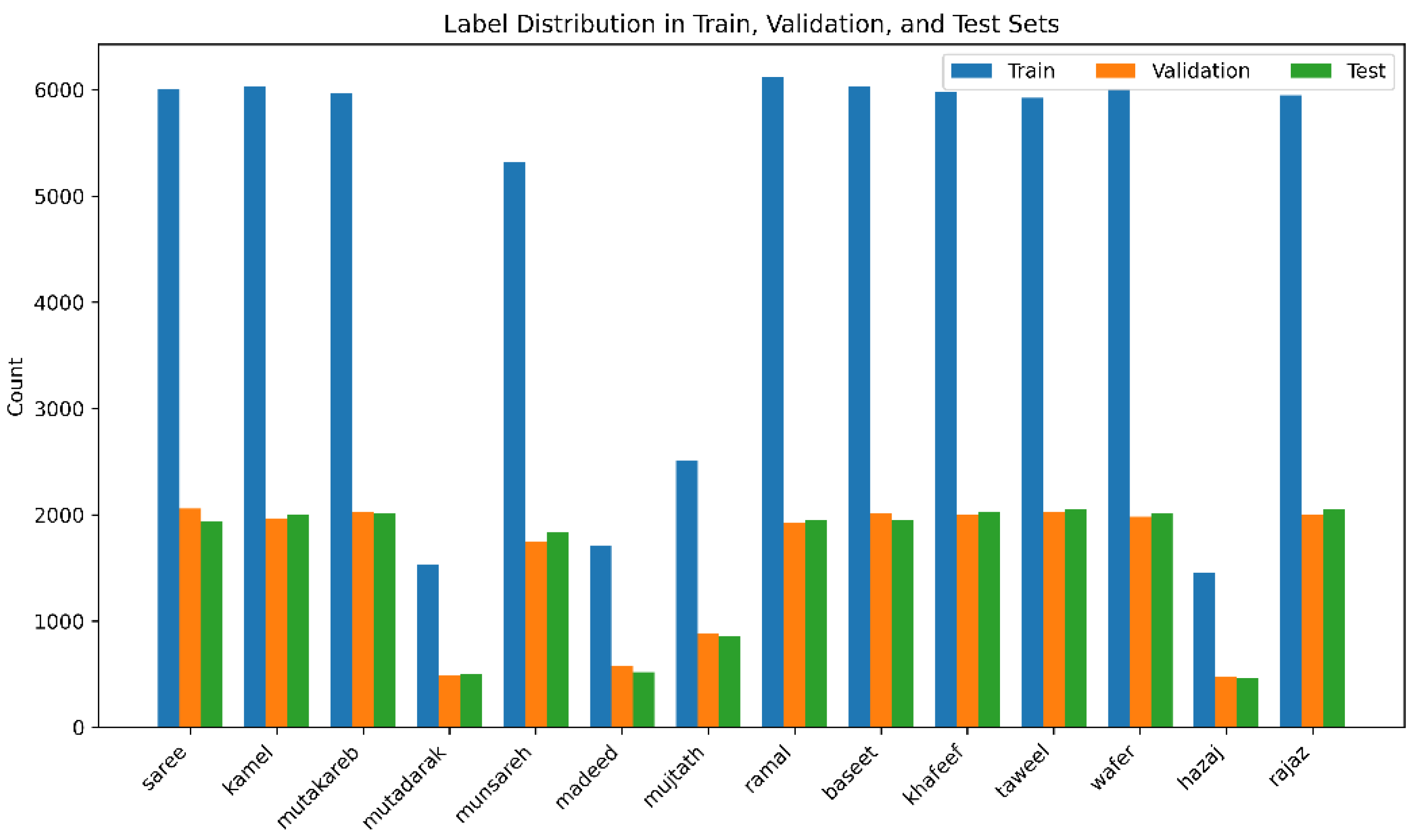

The cleaned data after removing unwanted characters, alphabets, and punctuations are then given to train-validate-test split. The data is split into 60% for training, 20% for validation, and the remaining 20% for testing the model. The total verse count for the train set is 66,528, and validation and test have 22,176 verses each. Each meter count for the splits is shown in

Figure 4.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Maximizing the efficiency of the proposed models depends on proper preprocessing. We use two alternative preprocessing methods considering the language's complexity and the varied architectures: character-level encoding for DL-based models and tokenization for transformer-based models.

3.2.1. Tokenization

In NLP, tokenizing, and dissecting text into smaller bits, is a basic first step. Based on the tokenizing technique employed, these tokens could be characters, subwords, or words. WordPiece and SentencePiece have become somewhat well-known among the several tokenizing methods because of their flexibility in many languages and applications [

31].

Created for the BERT concept, WordPiece is a subword tokenizing tool [

32,

33]. It works by building a vocabulary with every character found in the text. And then determines which most often occurring pair of neighboring tokens should be merged into a new token. It is then continued merging until either no more pairs can be merged, or a specified vocabulary size is achieved, hence optimizing the probability of the training data.

Google has developed another subword tokenizing tool called SentencePiece. It employs a data-driven technique to learn the vocabulary and treats the input text as a series of characters whereas WordPiece depends on frequency-based merging. Subword tokens can be produced by using Byte Pair Encoding or Unigram language models. The result is a collection of subword tokens fit for several NLP applications [

31].

Table 1 shows the tokenization methods for the pretrained transformer models employed in the study.

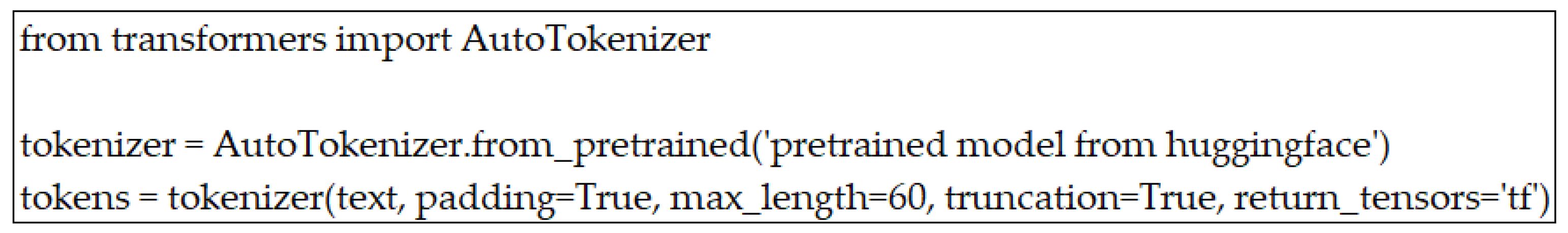

For the proposed study, we employed pretrained tokenizers while using the models. The code snippet for the tokenizer is shown in

Figure 5. The maximum length of the model is kept at 60, and the padding is set to True.

3.2.2. Character-Encoding

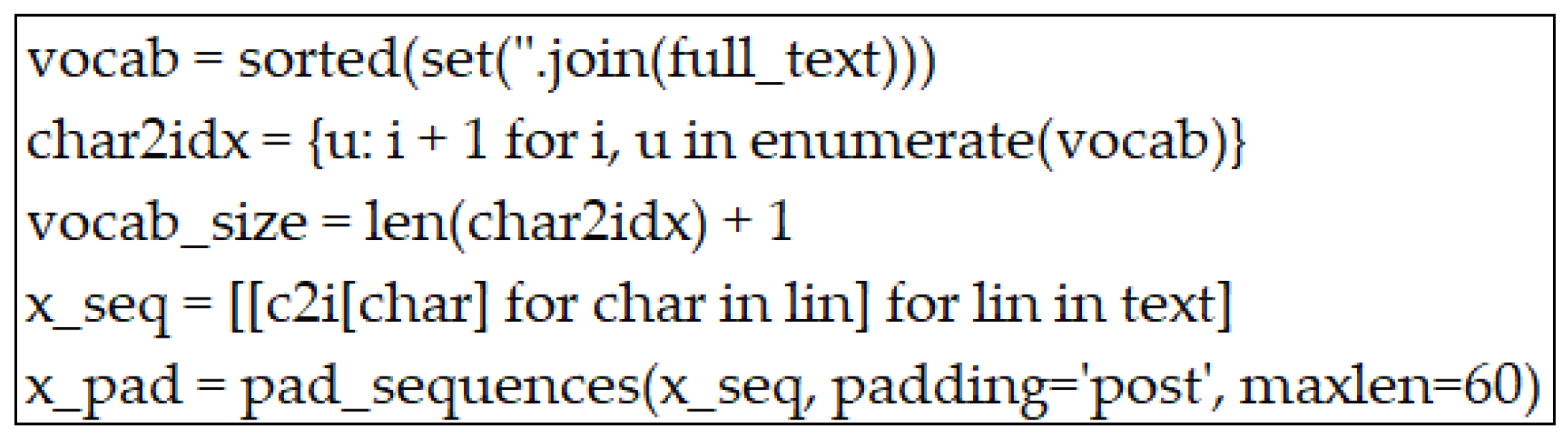

Character encoding is the process by which characters are turned into a format computer can readily access and control. In this work, we also address the complexity of the Arabic language which is rich in morphological structures employing character encoding. By removing special characters from the dataset and omitting spaces, the proposed study creates a vocabulary using character-level encoding [

30]. Each character was then assigned an index designed to produce a mapping dictionary. This mapping translated every text occurrence into a sequence of numerical indices, therefore preserving distinct characters. From the longest text in the dataset, we found the maximum sequence length by ensuring consistent input size using sequence padding. Especially helpful for handling spelling variations, and noisy text, this encoding method preserves character-level patterns. The code snippet for character encoding is depicted in

Figure 6.

3.3. Model Architectures

Different models were employed in this study for classifying the Arabic meters. The models such as AraBERT, ARBERT, MARBERT, CAMeLBERT, Arabic-BERT, AraELECTRA, BiGRU, and BiLSTM were used.

3.3.1. Transformer Models

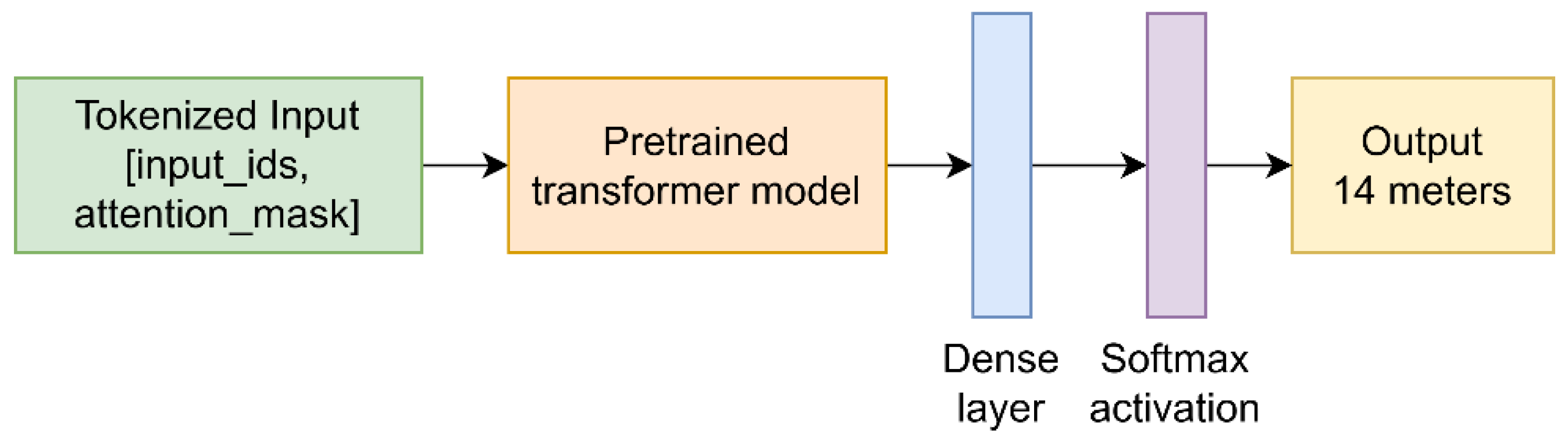

Transformers are suitable for high-stakes situations where performance is crucial as they can analyze large volumes and complex models. The workflow of the transformer model in the study is depicted in

Figure 7.

AraBERT is a transformer model pretrained primarily for the Arabic language [

34]. The creation sought to address the difficulties the Arabic language provided, notably its complicated morphology and several dialects. AraBERT shows outstanding performance on several Arabic NLP challenges, including sentiment analysis [

35]. It is constructed on BERT design. AraBERT is projected to greatly improve the performance of Arabic NLP applications as research develops, hence improving precision and efficacy in many different fields.

AraELECTRA is a pretrained transformer model designed exclusively for comprehending the Arabic language [

25]. The model extends to the ELECTRA architecture, which has shown significant efficacy across several NLP applications. Rather than teaching a model to retrieve masked tokens, ELECTRA uses a discriminator model to distinguish between real input tokens and damaged tokens, produced by a generator network. This approach makes improved learning efficiency possible with the same data amount.

Built on many Arabic dialects, classical Arabic, and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), CAMeLBERT is another robust transformer model for Arabic text processing [

26]. Unlike AraBERT, CameLBERT is taught on a combination of MSA and dialectal Arabic, which could help to capture stylistic variances in poetry. Built on BERT-based architecture, CAMeLBERT is improved in comprehension of poetry forms and word morphology by extensive Arabic data tuning.

MARBERT and ARBERT are two sophisticated transformer models designed for Arabic NLP-related activities [

36]. Recognized for their success in many NLP applications, this model improves BERT architecture and adapts it to fit the characteristics of the Arabic language. Utilizing a bidirectional attention mechanism, both models may assess the context of a word by examining both its left and right surroundings. Using a large corpus of Arabic literature, the MARBERT model was focused on several dialects and MSA. While the ARBERT model was focused on MSA.

Designed to expand the powers of the original BERT concept to the Arabic language, Arabic-BERT is specially designed for Arabic, concentrating on MSA and its language characteristics unlike other models [

37]. All the pretrained transformer models use 12 hidden layers, and 12 attention layers in the architecture.

3.3.2. Deep Learning Models

DL architectures like BiLSTM and BiGRU are extensively employed for the processing of sequential data, including NLP, time-series forecasting, and speech recognition. Both methods tackle the vanishing gradient issue inherent in conventional recurrent neural networks while effectively capturing long-term interdependence.

BiLSTM improves contextual learning by extending LSTM by considering the input sequences in forward as well as reverse directions [

38,

39]. The LSTM model includes three gates such as input, output, and forget gate.

where f

t is the forget gate with time stamp t, sigmoid activation function (σ), v

f and w

f denote the f

t’s weight matrices, I

t signifies the data input, a

f is the error vector, L

t-1 denotes the previous time step's concealed state result.

where the input gate is i

t; v

i and w

i denote the i

t’s weight matrices, and a

i is the error vector.

where

= candidate memory cell, the error vector is a

c, and v

c and w

c are the weight matrix.

where CS

t is the cell state, CS

t-1 represents the memory state vector from the previous timestamp, f

t is calculated from equation (1), i

t from equation (2), and

from equation (3).

where the output gate is o

t; v

o and w

o denote the o

t’s weight matrices, and a

o is the error vector.

where the hidden state is L

t, o

t is calculated from equation (5), and CS

t from equation (4). The BiLSTM analyzes the input sequence in both directions.

where the

is the output of LSTM in the forward state,

is LSTM in a backward state. The sign 'ʘ' may denote several operations, including multiplication, average, summation, and concatenation functions.

Less parameters and computing efficiency make the GRU a simpler substitute for LSTM. Like BiLSTM, BiGRU handles sequences both ways [

30]. It has two gates, namely the reset and update gate.

where RS

t is the reset gate, v

r, and w

r denote the RS

t’s weight matrices, G

t-1 denotes the previous time step's concealed state result, and a

r is the bias vector.

where P

t is the update gate, v

p and w

p denote the P

t’s weight matrices, and a

p is the error vector.

where

is the new hidden state, a

h is the error vector, v

h and w

h denote the weight matrices, and RS

t is evaluated from equation (8).

where G

t is the final updated hidden state, P

t is calculated from equation (9), and

is from equation (10).

where the

is the output of GRU in the forward state,

is GRU in a backward state. The sign 'ʘ' may denote several operations, including multiplication, average, summation, and concatenation functions.

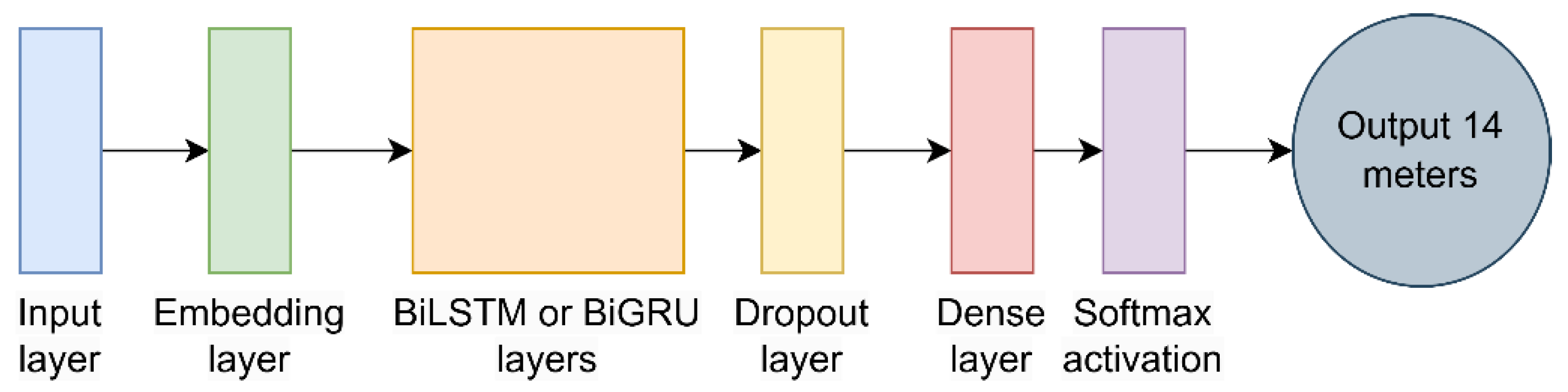

The BiLSTM and BiGRU model architecture is illustrated in

Figure 8. The approach initially transforms a sequence into an integer index using a character encoder. A particular vocabulary character is associated with this index. The input layer has the shape of the train set. The embedding layer transforms input tokens into dense vectors of predetermined size. The embedding dimension is set to 128. The BiGRU or BiLSTM layer analyzes the sequence in both forward and backward orientations, capturing dependencies from previous and future instances. If the layer is greater than 1 then the return-sequence variable is turned to True. The bidirectional dimension is set to 256. One regularizing method to stop overfitting is to set the dropout layer. It is set as 0.2 in the study. The fully connected layer, dense layer, is mapped to the total class length, of 14 in this study. The Softmax is kept as the activation function. The ultimate prediction is the category with the highest likelihood derived from the Softmax output.

3.4. Model Evaluation and Parameter Tuning

The system environment for the study is as follows:

Windows 10 operating system

16 GB RAM

Inter core i7 processor

GPUS - Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti

Deep learning libraires - TensorFlow 2.7, Transformers 4.48.1

Other evaluation libraries - Scikit-learn 1.0, PyArabic 0.6.14, lime 0.2.0.1

The models are compiled before fitting to train the data. The Adaptive moment estimation (Adam) is used as the optimizer. It requires smaller memory and is notably effective [

40]. The loss function employed is sparse categorical cross entropy as the labels are sparse matrix.

The study's tuning parameters are based on the models. The DL models are tuned using several hidden layers. The transformer model is optimized according to batch size. This study employs EarlyStopping and ReduceLRonPlateau approaches as regularization methods to mitigate overfitting. The model will cease training when achieving the ideal result based on the specified parameters, before the onset of overfitting. The EarlyStopping parameter monitors validation loss; if it remains constant or increases during eight epochs, the model ceases iteration and retains the optimal model. The ReduceLRonPlateau method adjusts the learning rate by a multiplier of 0.1 when the loss value stands unchanged for two epochs.

Table 2 shows the parameters used in the study.

3.5. Performance Evaluation

The model is evaluated based on the test data. The confusion matrix and the classification report are analyzed for each model. For multi-class classification, this study assesses criteria like accuracy, F1-score, recall, and precision. Each metric's formulas are given below.

The classification of a meter is accurate, as it is assigned to its proper category (Tpos). For instance, if a verse composed in saree meter is predicted to be saree, this is a genuine positive circumstance. A line that deviates from a specified meter is accurately recognized as not conforming to that meter (Tneg). One misclassifies a meter as yet another meter (Fpos). A meter that truly falls within a certain class is misclassified as belonging another class is Fneg. For example, if a verse from kamel meter is classified as madeed, then it is a Fpos for madeed meter and Fneg for kamel meter.

3.6. Explainability with LIME

LIME is a method that employs an interpretable model to locally approximate predictions, thereby clarifying the prediction [

41]. It can highlight the words or characters that most significantly influence the categorization choice in the classification model. LIME approximates the model's decision in a relatively small area surrounding a specific instance by influencing the input data and tracking the way the model's prediction changes.

LIME aids in discerning which words significantly influence the model's predictions within the framework of Arabic meter categorization, hence facilitating the analysis of the patterns identified by the transformer models.

4. Results

The dataset used in this study is MetRec data with 55,440 verses. The total number of half-verses is 110,880. There are no studies based on the half-verse and transformer models. The data is split to 60-20-20 for the train-validate-test. The labels are encoded from 0 to 13.

4.1. Deep Learning Models

In the DL models the text data are encoded using the character-encoding method. The BiLSTM and BiGRU models are tuned with layers. The complete performance results are shown in

Table 3. The BiGRU model shows the best performance in layer 5 with 90.39% testing accuracy, and 0.90 F1-score, recall, and precision scores. The BiLSTM model shows the best results in 6 layers with 90.53% testing accuracy, 0.90 recall, and 0.91 F1-score and precision score. The EarlyStopping parameter exits the training process when the validation loss keeps increasing or stable for eight epochs. So, the training stops at epochs are mentioned in the table for each layer.

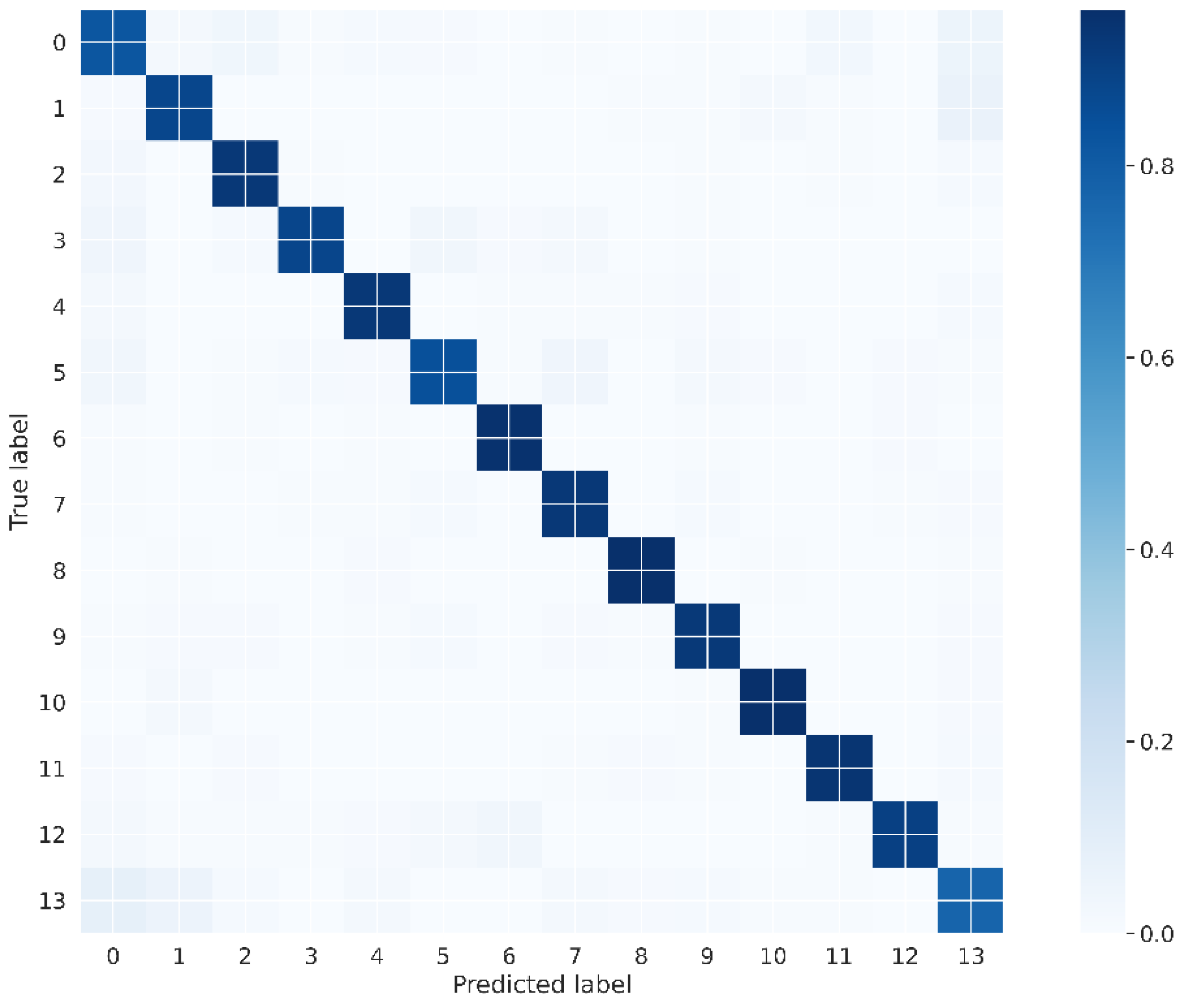

Each class results for the BiLSTM model with 6 layers are depicted in

Table 4. The highest F1-score is shown by baseet and Taweel meters with a 0.96 score. While the rajaz meter shows the lowest F1-score with 0.79 score. The confusion matrix for the best model (BiLSTM) with 6 layers is depicted in

Figure 9.

4.2. Transformer Models

In the transformer model, the text data are encoded using the tokenizer method. The models are tuned with batch size. The complete performance outcomes are depicted in

Table 5. The CAMeLBERT model with batch size 64 shows the best performance with 90.62% testing accuracy, and 0.91 recall, F1-score, and precision scores.

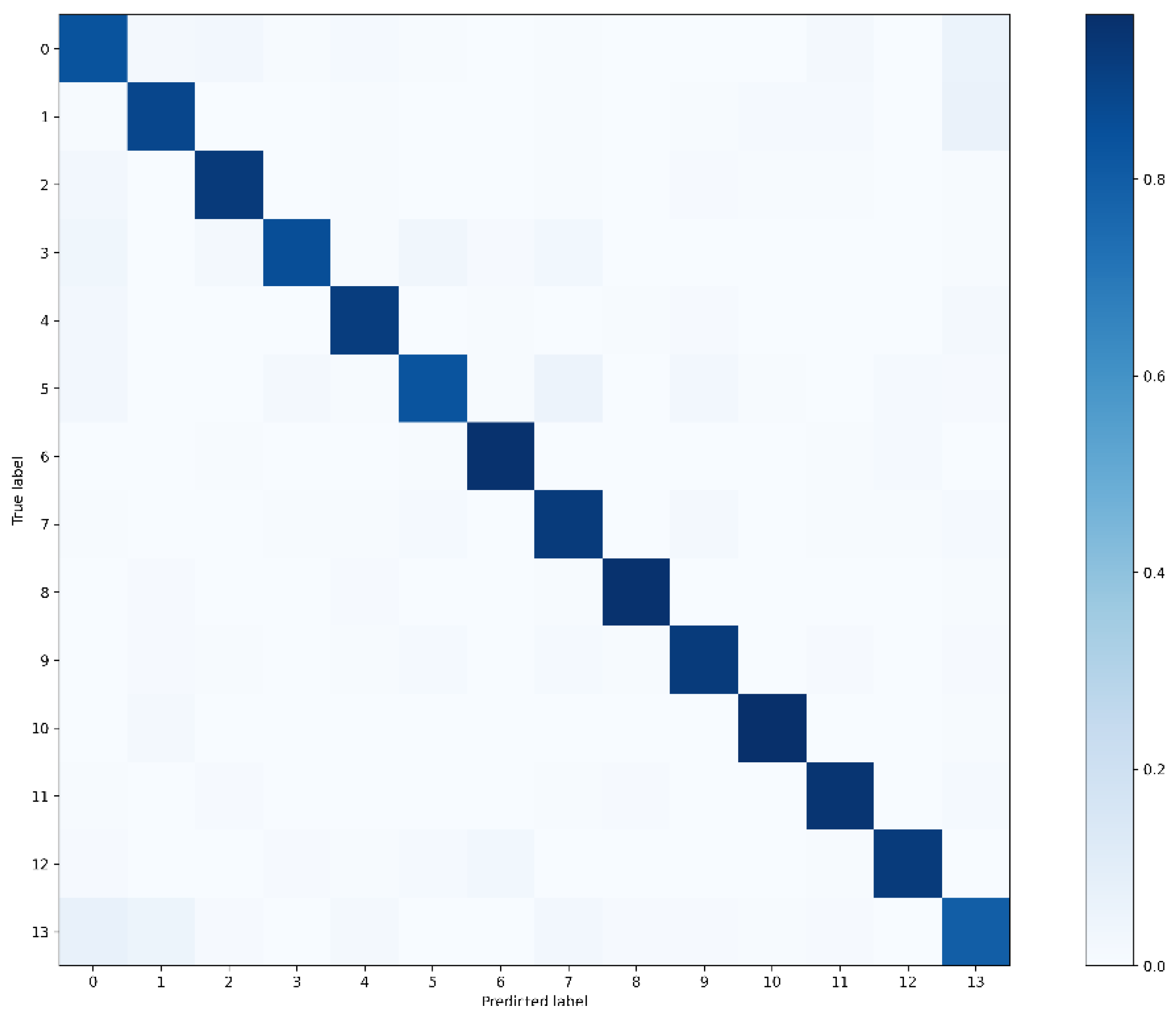

Each class results for the CAMeLBERT model with batch size 64 is depicted in

Table 6. The highest F1-score is shown by baseet and Taweel meters with a 0.96 score. While the rajaz meter shows the lowest F1-score with a 0.80 score. The CAMeLBERT model’s confusion matrix is shown in

Figure 10.

5. Discussion

In this study, we analyzed different models such as pretrained transformer models and bidirectional DL models. The half-verse data with 14 meters is investigated in this study. Slightly surpassing the BiLSTM model, which got 90.53%, the CAMeLBERT model attained the best accuracy of 90.62%.

The tokenizers were also evaluated on the BiLSTM model. Both SentencePiece (AraBERT) and WordPiece (CAMeLBERT) were analyzed. The model is tested with two layers, as depicted in

Table 7. It does not show much performance on the BiLSTM model, and hence we considered the character encoding on DL models.

BiLSTM uses long-term memory's advantages to extend traditional LSTM by handling both directions of processing sequences [

42]. LSTMs with memory cells more effectively capture long-range dependencies than GRUs. Al-shathry [

43] carried out further research using a balanced dataset on full-verse poems. To create this dataset, 1000 poetry verses of every 14 meters were chosen at random. Their study applied the BiGRU model, producing a score of 0.90 for recall or sensitivity, precision, and F1-score, along with 98.6% accuracy.

Transformer models have greatly enhanced NLP challenges including Arabic meter categorization. These models use deep contextual embeddings to pick out intricate language patterns exclusive to Arabic [

15,

44]. The CAMeLBERT model was trained on different datasets, and one among them is the poetry dataset. But the model achieved only 80.9% accuracy [

26]. The exceptional performance of transformer models arises from their self-attention mechanism, which allows for more efficient modeling of long-range relationships compared to recurrent systems such as BiLSTM or BiGRU. They excel at capturing complex linguistic attributes [

28].

Poetry in Arabic frequently adheres to systematic metrical structures, which may be concisely encapsulated within half verse. Examining half verses preserves crucial rhythmic and structural characteristics. The comparison with previous studies based on the dataset is mentioned in

Table 8.

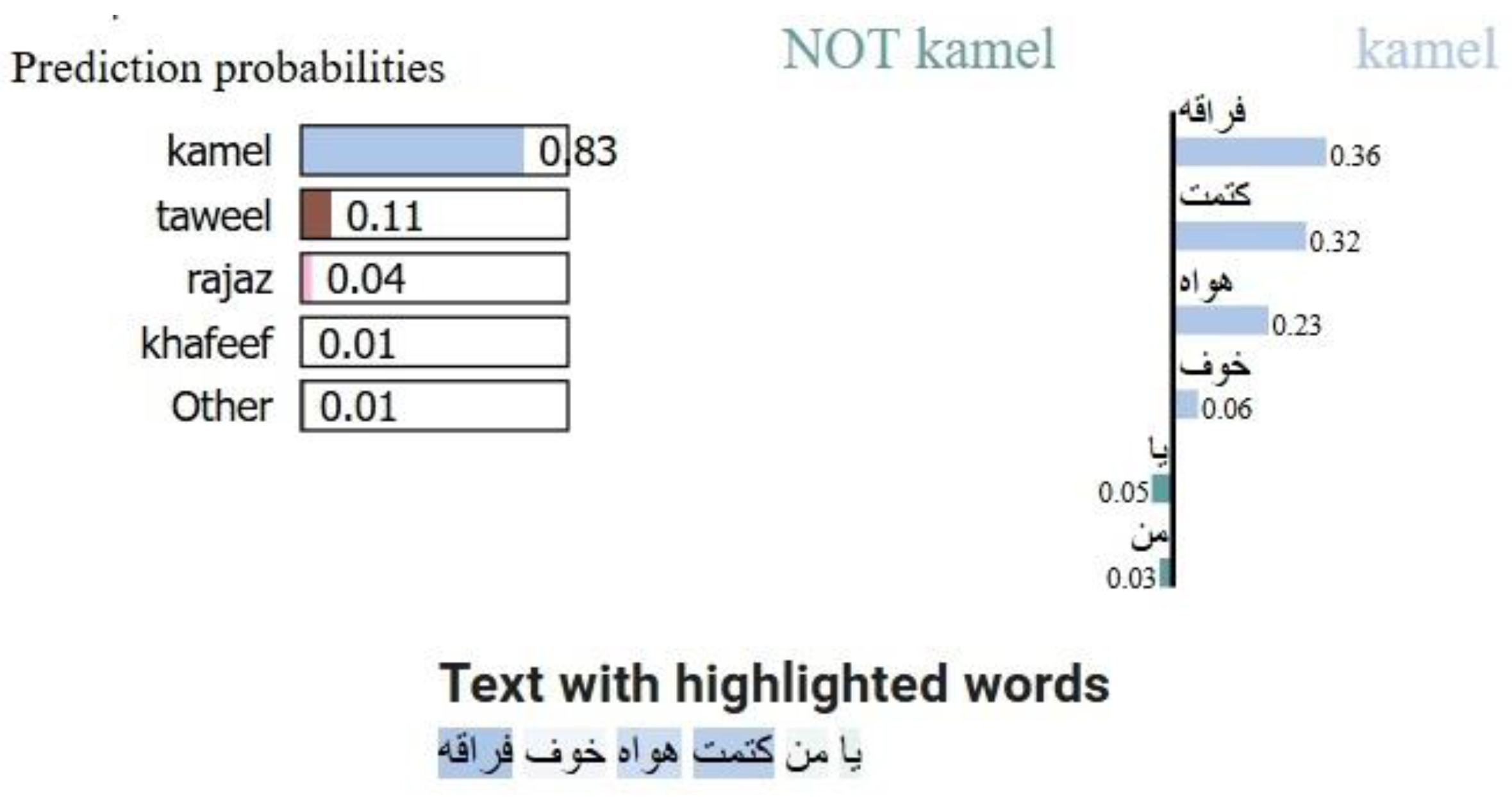

The LIME explainability of the model is illustrated in

Figure 11 for sample text 1,

Figure 12 for sample text 2, and text 3 in

Figure 13. It explains how the model helps in prediction by showing the importance of the word. The figure depicts a text sample where LIME has underlined terms in many colors. These colors show the value of every word in the model's categorization choice. The text with highlighted words and the probabilities of top meters can be identified in each figure. LIME clarifies which syllables or phrases most support the categorization of a certain meter.

5.1. Practical Implications

The proposed study's conclusions hold considerable practical significance for the analysis of Arabic poetry, and AI-driven literature purposes. The enhanced accuracy achieved using half-verse data demonstrates that meter classification may be efficiently automated without requiring whole verses, making the approach more applicable in real-world contexts. Moreover, transformer and DL models’ ability to capture metrical patterns creates new opportunities for educational tools whereby academics and students may use AI to rapidly examine and categorize Arabic meters.

This research has significance for NLP implementations in Arabic, especially for challenges necessitating rhythmic comprehension. The present research demonstrates that half-verse data is adequate for precise categorization, hence diminishing processing demands and enhancing the accessibility of AI-driven meter classification for organizations, academics, students, and developers engaged in Arabic language technology.

5.2. Limitation and Future Works

Although the proposed study employs half-verse data to attain an increased level of accuracy in Arabic meter classification, it has certain limits. One of the restrictions is that it depends on a certain dataset, which might not have been able to adequately depict the diversity of Arabic poetry. Future research should investigate the possibilities of broadening the dataset to cover a larger diversity of poetic styles, as well as emotions to evaluate the generalizability of the models. Furthermore, multimodal methodologies that combine textual elements with audio inputs may be explored to improve the study of Arabic poetry.

6. Conclusions

The proposed work examined Arabic meter categorization under many DL and transformer models including AraBERT, AraELECTRA, Arabic-BERT, ARBERT, MARBERT, CAMeLBERT, BiGRU, and BiLSTM models. With 90.62%, CAMeLBERT models show the best accuracy; closely behind BiLSTM at 90.53%. These results show how well the transformers may capture intricate metrical systems in Arabic poetry. The results imply that automatic meter categorization may enable several NLP tasks, involving poetry translation, and text-to-speech synthesis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. Mutawa; Data curation, Sai Sruthi; Formal analysis, Sai Sruthi; Funding acquisition, A. Mutawa; Methodology, A. Mutawa and Sai Sruthi; Project administration, A. Mutawa; Resources, A. Mutawa; Software, Sai Sruthi; Supervision, A. Mutawa; Validation, A. Mutawa; Writing – original draft, A. Mutawa and Sai Sruthi; Writing – review & editing, A. Mutawa.

Funding

This research was funded by Kuwait University, grant number EO06/24.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is publicly available at [

13].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yi, X.; Sun, M.; Li, R.; Li, W. Automatic poetry generation with mutual reinforcement learning. Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing 2018, 3143–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawī, M.M. A critical introduction to modern Arabic poetry; Cambridge University Press: 1975.

- Scott, H. Pegs, cords, and ghuls: Meter of classical Arabic poetry. 2010.

- Abandah, G.A.; Suyyagh, A.E.; Abdel-Majeed, M.R. Transfer learning and multi-phase training for accurate diacritization of Arabic poetry. Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 3744–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkiyumi, M. The creative linguistic achievements of Alkhalil bin Ahmed Al-Farahidi, and motives behind his creations: A case study. Cogent Arts & Humanities 2023, 10, 2196842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Al-Azani, S. Enhancing Arabic NLP Tasks through Character-Level Models and Data Augmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2025; pp. 2744-2757.

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Megra, K.T. Transformer enabled multi-modal medical diagnosis for tuberculosis classification. Journal of Big Data 2025, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihal, M.; Hamza, L. Efficient arabic and english social spam detection using a transformer and 2D convolutional neural network-based deep learning filter. International Journal of Information Security 2025, 24, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzeh, M.; Qusef, A.; Alabboushi, O. Arabic Fake News Detection in Social Media Context Using Word Embeddings and Pre-trained Transformers. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2025, 50, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.M.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rabie, E.M.; Hashem, A.F.; Alsheref, F.K. Recognition model for major depressive disorder in Arabic user-generated content. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2025, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcamonico, D.; Baraldi, P.; Macêdo, J.B.; Moura, M.D.C.; Brown, J.; Gauthier, S.; Zio, E. A systematic procedure for the analysis of maintenance reports based on a taxonomy and BERT attention mechanism. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2025, 257, 110834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shaibani, M.S.; Alyafeai, Z.; Ahmad, I. MetRec: A dataset for meter classification of arabic poetry. Data in Brief 2020, 33, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talghalit, I.; Alami, H.; Ouatik El Alaoui, S. Contextual Semantic Embeddings Based on Transformer Models for Arabic Biomedical Questions Classification. HighTech and Innovation Journal 2024, 5, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosaimi, W.; Saleh, H.; Hamzah, A.A.; El-Rashidy, N.; Alharb, A.; Elaraby, A.; Mostafa, S. ArabBert-LSTM: improving Arabic sentiment analysis based on transformer model and Long Short-Term Memory. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AL-ONAZI, B.B.; ELTAHIR, M.M.; ALZAIDI, M.S.A.; EBAD, S.A.; ALOTAIBI, S.D.; SAYED, A. AUTOMATING METER CLASSIFICATION OF ARABIC POEMS: A HARRIS HAWKS OPTIMIZATION WITH DEEP LEARNING PERSPECTIVE. Fractals 2025, 0, 2540008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karfi, I.E.; Fkihi, S.E. A combined Bi-LSTM-GPT Model for Arabic Sentiment Analysis. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering 2023, 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Meng, Y.; Qiu, X.; Yu, Z.; Wu, X. Sentiment analysis of comment texts based on BiLSTM. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 51522–51532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. Research of Text Classification Based on TF-IDF and CNN-LSTM. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2022, 2171, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refai, D.; Abu-Soud, S.; Abdel-Rahman, M.J. Data Augmentation Using Transformers and Similarity Measures for Improving Arabic Text Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 11, 132516–132531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Deen, M.M.S.; Pielka, M.; Hees, J.; Abdou, B.S.; Sifa, R. Improving Natural Language Inference in Arabic Using Transformer Models and Linguistically Informed Pre-Training. 2023 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), 05-08 December 2023, Mexico City, Mexico 2024, 318-322. [CrossRef]

- Qarah, F. AraPoemBERT: A Pretrained Language Model for Arabic Poetry Analysis. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:abs/2403.12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Safran, M.; Alfarhood, S.; Alfarhood, M.; Mridha, M.F. A Hybrid Attention-Based Transformer Model for Arabic News Classification Using Text Embedding and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 198046–198066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, H.; El-Sayed, A.; Elleithy, K. AI-Generated Text Detector for Arabic Language Using Encoder-Based Transformer Architecture. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, W.; Baly, F.; Hajj, H. AraELECTRA: Pre-training text discriminators for Arabic language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Sixth Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop, Kyiv, Ukraine (Virtual), 2020; pp. 191–195.

- Inoue, G.; Alhafni, B.; Baimukan, N.; Bouamor, H.; Habash, N. The Interplay of Variant, Size, and Task Type in Arabic Pre-trained Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Sixth Arabic Natural Language Processing Workshop, Kyiv, Ukraine (Virtual), 2021; pp. 92–104.

- Alruily, M.; Manaf Fazal, A.; Mostafa, A.M.; Ezz, M. Automated Arabic Long-Tweet Classification Using Transfer Learning with BERT. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammary, A.S. BERT Models for Arabic Text Classification: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammary, A.S. Investigating the impact of pretraining corpora on the performance of Arabic BERT models. The Journal of Supercomputing 2024, 81, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shaibani, M.S.; Alyafeai, Z.; Ahmad, I. Meter classification of Arabic poems using deep bidirectional recurrent neural networks. Pattern Recognition Letters 2020, 136, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, S.; Kim, W. A study on the evaluation of tokenizer performance in natural language processing. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, A.; Yıldız, O.T.; Özer, S. ORTPiece: An ORT-Based Turkish Image Captioning Network Based on Transformers and WordPiece. 2023 31st Signal Processing and Communications Applications Conference (SIU) 2023, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 최용석; 이공주. Performance Analysis of Korean Morphological Analyzer based on Transformer and BERT. Journal of KIISE 2020, 47, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, W.; Baly, F.; Hajj, H. AraBERT: Transformer-based model for arabic language understanding. In Proceedings of the In Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Open-Source Arabic Corpora and Processing Tools, with a Shared Task on Offensive Language Detection, Marseille, France, 2020; pp. 9–15.

- Hussein, H.H.; Lakizadeh, A. A systematic assessment of sentiment analysis models on iraqi dialect-based texts. Systems and Soft Computing 2025, 7, 200203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mageed, M.; Elmadany, A.; Nagoudi, E.M.B. ARBERT & MARBERT: Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Arabi. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2021; pp. 7088–7105.

- Safaya, A.; Abdullatif, M.; Yuret, D. KUISAIL at SemEval-2020 Task 12: BERT-CNN for Offensive Speech Identification in Social Media. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fourteenth Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, Barcelona (online), December, 2020; pp. 2054–2059.

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M. Bilstm Personalised-Style Poetry Generation Algorithm. 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Power, Electronics and Computer Applications (ICPECA) 2023, 836-840. [CrossRef]

- Atassi, A.; El Azami, I. COMPARISON AND GENERATION OF A POEM IN ARABIC LANGUAGE USING THE LSTM, BILSTM AND GRU. Journal of Management Information & Decision Sciences 2022, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1412.6980 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Garreau, D.; Luxburg, U. Explaining the explainer: A first theoretical analysis of LIME. In Proceedings of the International conference on artificial intelligence and statistics; 2020; pp. 1287–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, B.; Thomas, A.; Verma, R.K. Innovative abstractive Hindi text summarization model incorporating Bi-LSTM classifier, optimizer and generative AI. Intelligent Decision Technologies 2025, 0, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Al-shathry, N.; Al-onazi, B.; Hassan, A.Q.A.; Alotaibi, S.; Alotaibi, S.; Alotaibi, F.; Elbes, M.; Alnfiai, M. Leveraging Hybrid Adaptive Sine Cosine Algorithm with Deep Learning for Arabic Poem Meter Detection. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharsa, R.; Elnagar, A.; Yagi, S. BERT-Based Arabic Diacritization: A state-of-the-art approach for improving text accuracy and pronunciation. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 248, 123416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The methodology of the proposed study.

Figure 1.

The methodology of the proposed study.

Figure 2.

The count of labels in half verse data. The highest count is 10,000 (9 meters) while the lowest count is 2402 by hazaj meter.

Figure 2.

The count of labels in half verse data. The highest count is 10,000 (9 meters) while the lowest count is 2402 by hazaj meter.

Figure 3.

The word cloud of the MetRec half-verse data.

Figure 3.

The word cloud of the MetRec half-verse data.

Figure 4.

Meter counts for train, validation, and test splits.

Figure 4.

Meter counts for train, validation, and test splits.

Figure 5.

Code-snippet for calling the tokenizer from the pretrained model.

Figure 5.

Code-snippet for calling the tokenizer from the pretrained model.

Figure 6.

Code-snippet for calling the character encoding method for the DL models.

Figure 6.

Code-snippet for calling the character encoding method for the DL models.

Figure 7.

Transformer models architecture.

Figure 7.

Transformer models architecture.

Figure 8.

The BiLSTM and BiGRU model architecture.

Figure 8.

The BiLSTM and BiGRU model architecture.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of the BiLSTM model with 6 layers.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of the BiLSTM model with 6 layers.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of the CAMeLBERT model with batch size 64.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of the CAMeLBERT model with batch size 64.

Figure 11.

LIME explanation with a sample text-1.

Figure 11.

LIME explanation with a sample text-1.

Figure 12.

LIME explanation with a sample text-2.

Figure 12.

LIME explanation with a sample text-2.

Figure 13.

LIME explanation with a sample text-3.

Figure 13.

LIME explanation with a sample text-3.

Table 1.

Tokenization for different pretrained transformer models.

Table 1.

Tokenization for different pretrained transformer models.

| Model |

Tokenizer |

| AraBERT |

SentencePiece |

| AraELECTRA |

WordPiece |

| ARBERT |

WordPiece |

| MARBERT |

WordPiece |

| Arabic-BERT |

SentencePiece |

| CAMeLBERT |

WordPiece |

Table 2.

Parameters used in the proposed study for each model.

Table 2.

Parameters used in the proposed study for each model.

| Model |

Parameter |

Values |

Tuning |

| Transformer model |

Batch size |

[32, 64, 128] |

Yes |

| Epoch |

50 |

No |

| Learning rate |

5e-5 |

No |

| Bidirectional model |

Batch size |

128 |

No |

| Layers |

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] |

Yes |

| Epoch |

50 |

No |

| Learning rate |

1e-3 |

No |

Table 3.

The performance of the DL models in the proposed study.

Table 3.

The performance of the DL models in the proposed study.

| Model |

Hidden layers |

Training Time (in seconds) |

Validation Accuracy (%) |

Testing Time (in seconds) |

EarlyStopping epochs |

Testing Accuracy (%) |

Recall |

Precision |

F1-score |

| BiGRU |

1 |

184.51 |

86.34 |

10.09 |

14 |

86.42 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

| 2 |

439.77 |

89.16 |

16.57 |

18 |

88.88 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

| 3 |

636.27 |

90.07 |

26.29 |

18 |

90.06 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 4 |

1236.31 |

90.21 |

31.20 |

27 |

90.34 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 5 |

1090.65 |

90.44 |

36.79 |

18 |

90.39 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 6 |

2295.92 |

90.25 |

47.03 |

34 |

90.04 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 7 |

3135.84 |

90.53 |

56.34 |

39 |

90.09 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| BiLSTM |

1 |

200.68 |

86.09 |

8.59 |

14 |

85.83 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

| 2 |

390.16 |

88.88 |

15.88 |

14 |

88.68 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

| 3 |

712.73 |

88.79 |

23.63 |

17 |

89.13 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

| 4 |

907.06 |

89.84 |

32.77 |

16 |

89.66 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 5 |

1144.01 |

90.20 |

38.75 |

16 |

90.05 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 6 |

1632.94 |

90.37 |

47.11 |

18 |

90.53 |

0.90 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

| 7 |

2022.12 |

90.56 |

54.70 |

20 |

90.33 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

Table 4.

The complete results of each meter for BiLSTM with 6 layers.

Table 4.

The complete results of each meter for BiLSTM with 6 layers.

| Meters |

Encoded meters |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| saree |

0 |

0.82 |

0.82 |

0.82 |

| kamel |

1 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

| mutakareb |

2 |

0.92 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| mutadarak |

3 |

0.90 |

0.88 |

0.89 |

| munsareh |

4 |

0.92 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| madeed |

5 |

0.80 |

0.85 |

0.82 |

| mujtath |

6 |

0.94 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

| ramal |

7 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| baseet |

8 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

| khafeef |

9 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| taweel |

10 |

0.95 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

| wafer |

11 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

| hazaj |

12 |

0.91 |

0.90 |

0.91 |

| rajaz |

13 |

0.80 |

0.77 |

0.79 |

Table 5.

The performance of the transformer models in the proposed study.

Table 5.

The performance of the transformer models in the proposed study.

| Model |

Batch size |

Training Time (in seconds) |

Validation Accuracy (%) |

Testing Time (in seconds) |

EarlyStopping epochs |

Testing Accuracy (%) |

Recall |

Precision |

F1-score |

| AraBERT |

32 |

2561.87 |

84.36 |

66.83 |

10 |

85.24 |

0.85 |

0.85 |

0.85 |

| 64 |

2017.41 |

79.91 |

60.01 |

10 |

79.95 |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

| 128 |

1505.03 |

78.76 |

61.73 |

10 |

78.85 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

| Arabic-BERT |

32 |

2167.33 |

81.44 |

81.31 |

9 |

62.71 |

0.81 |

0.81 |

0.81 |

| 64 |

1566.64 |

78.93 |

62.03 |

8 |

79.04 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

| 128 |

1148.03 |

76.08 |

57.26 |

8 |

75.92 |

0.76 |

0.76 |

0.76 |

| AraELECTRA |

32 |

2204.53 |

87.59 |

60.23 |

14 |

87.14 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

| 64 |

1901.09 |

83.46 |

56.83 |

10 |

83.72 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

| 128 |

1623.86 |

79.63 |

55.83 |

12 |

79.60 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

| ARBERT |

32 |

2299.88 |

72.92 |

58.11 |

9 |

73.21 |

0.73 |

0.74 |

0.73 |

| 64 |

1546.04 |

78.01 |

57.02 |

8 |

78.37 |

0.78 |

0.79 |

0.78 |

| 128 |

1094.12 |

77.57 |

53.76 |

8 |

77.23 |

0.77 |

0.77 |

0.77 |

| CAMeLBERT |

32 |

2431.07 |

90.59 |

35.18 |

12 |

90.26 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| 64 |

1769.59 |

90.49 |

54.08 |

12 |

90.62 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

0.91 |

| 128 |

1232.03 |

90.57 |

52.28 |

12 |

90.21 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

| MARBERT |

32 |

1875.58 |

83.95 |

59.64 |

7 |

83.43 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

| 64 |

1348.81 |

82.79 |

57.97 |

7 |

82.69 |

0.82 |

0.83 |

0.82 |

| 128 |

929.73 |

83.07 |

62.54 |

7 |

83.35 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

Table 6.

The complete results of each meter for CAMeLBERT with batch size 64.

Table 6.

The complete results of each meter for CAMeLBERT with batch size 64.

| Meters |

Encoded meters |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

| saree |

0 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

0.84 |

| kamel |

1 |

0.89 |

0.88 |

0.89 |

| mutakareb |

2 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| mutadarak |

3 |

0.90 |

0.86 |

0.88 |

| munsareh |

4 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

| madeed |

5 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

0.83 |

| mujtath |

6 |

0.93 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

| ramal |

7 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

| baseet |

8 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

| khafeef |

9 |

0.93 |

0.92 |

0.93 |

| taweel |

10 |

0.96 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

| wafer |

11 |

0.93 |

0.95 |

0.94 |

| hazaj |

12 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

| rajaz |

13 |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.80 |

Table 7.

The result of the BiLSTM model with transformer tokenizer.

Table 7.

The result of the BiLSTM model with transformer tokenizer.

| Tokenizer |

Layers |

F1-score |

Accuracy (%) |

Recall |

Precision |

| AraBERT |

1 |

0.45 |

45.66 |

0.45 |

0.45 |

| 5 |

0.52 |

52.28 |

0.52 |

0.53 |

| CAMeLBERT |

1 |

0.40 |

40.98 |

0.40 |

0.41 |

| 5 |

0.40 |

40.24 |

0.39 |

0.41 |

Table 8.

Comparison of the proposed study with previous studies with the same half-verse data.

Table 8.

Comparison of the proposed study with previous studies with the same half-verse data.

| Reference, year |

Model |

Verse length |

Accuracy (%) |

F1-score |

| [30], 2020 |

BiGRU 5 layers |

110,880 |

88.80 |

- |

| The proposed study |

BiLSTM 6 layers |

110,880 |

90.53 |

0.91 |

| CAMeLBERT |

90.62 |

0.91 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).