1. Introduction

In the last few years, several types of noninteger calculus constructed with new derivatives and integrals have been presented [1,2]. Which have generated many applications in several fields such as Physics, Engineering, Finance, Biology, Medicine, Chemistry and other disciplines [3–5]. Also, theoretical developments related to these new calculations, for example in differential equations, inequalities, and dynamical systems, among others [6,7]. Some of these operators have been produced from modifications of previously formed operators. Among these operators are fractional operators of distributed order, fractional operators of variable order, and fractional operators that depend on a function [8–10]. Adding new characteristics to the new operators and therefore generating new possibilities of applications and theoretical developments.

When some phenomenon or system presents non-local properties or persistent memory that may vary with respect to time, space, or other variables, it is necessary to resort to variable order (VO) operators.

Several proposals have been made in recent years, starting with the Scarpi derivative based on the Laplace transform [11], which has been restated at [12–14], with several applications and considering time-dependent dynamics in the variable order of the derivatives. On the other hand, Lorenzo [15], proposes multivariable order operators. Sun et al., in [16] propose Caputo-type operators of variable order dependent on the state variable of the original system.

A topic little studied to date, is when a fractional operator has variable order, but this has a dynamics that may depend on the same order and other variables such as the state variables of the system [13,17]. The relevance of studying these cases lies in the wealth of answers that can be obtained from simple systems, such as those governed by first-order linear ordinary differential equations. These have well-known answers, but restricted in the possible solutions and consequently in limitations in the dynamics that they can present to model. Considering the need for new models that are more flexible and exhibit richer dynamics for many current applications, we believe that it is valuable to explore simple fractional systems with more complex dynamics in their order. This will help to better understand the potential they offer for modeling, studying, and simulating phenomena and systems that have posed challenges in their modeling, often being approached with nonlinear equations or equations featuring more complex variable coefficients. Continuing in this direction, this article presents three examples and a lemma, where we obtain different types of dynamics in the order of one derivative. To construct these examples, we decided to use the Scarpi derivative because of the advantages it presents with its Laplace transform and the advances that have been recently developed [12ဓ,14,17].

In this article, we explore new ways to define the dynamics of the variable order in Scarpi’s fractional derivatives, with an emphasis on expanding their potential, without delving into the physical implications of the results. The novel aspects introduced in the three study cases are as follows:

1) In the first case, we proposed a novel dynamics for described by a first-order differential equation that incorporates the state variable and its first derivative . To our knowledge, this approach is unprecedented, as previous works have defined the dynamics of solely as a function of the state variables [16] or in terms of a differential equation (ordinary or fractional) with and t as dependent and independent variables, respectively [14].

2) In the second case, we proposed a second-order dynamics for , which combines an ordinary derivative, a fractional derivative, and the state variable . This example highlights the possibility of using combinations of different types of derivatives to define the dynamics of the variable order.

3) The third case presents a recursive system based on Scarpi derivatives of variable orders , , and , which interact and influence each other. This approach, still unexplored in the literature, proposes a novel dynamic model that exhibits significant differences compared to the classical case.

Finally, a Lemma generalizing Example 3 is proved. Showing that the “nested” dynamics of example 3 is recursive and therefore it is possible to use mathematical induction.

2. Preliminaries

We begin this section by presenting Scarpi’s approach to variable order calculus based on [13,17] and for a more detailed treatment we recommend the reader to see [18].

We begin considering a function

such that

with the following properties:

1) exists and its analytical expression is known;

2) exist and belong to ;

3) is locally integrable on for some T known.

Now we define following operators

and its inverse operators as

Definition [17] If

f is absolutely continuous, the Scarpi fractional derivative of variable order

is

If

f is an integrable funcion, the Scarpi fractional integral of variable order

is

It is known that

and

satisfy the Sonine equaton

Then, in the Laplace domain we have

Therefore,

and

form a Sonine pair and satisfy

When

is constant the definitions of Scarpi’s derivative and integral reduce to the usual definitions of Caputo derivative and Riemann-Liouville integral, respectively. The Laplace transform of

is given by

where

and

is known.

3. Examples with Various Dynamics for (t)

This section presents results corresponding to three examples in which different types of dynamics have been proposed to characterize the behavior of the dynamic variable order based on a simple case of first-order dynamics with Scarpi derivative, similar to the one presented in [19], but with linear nonhomogeneity in the temporal variable.

3.1. Case 1.

After applying the Laplace transform to equations (10) and (11), we are obtained, respectively:

Substituting equation (12) into equation (13), we have the following equation

After some basic algebra and applying the Lambert function

W we obtain the following exact solution for

Table 1 shows different combinations of values for the parameters

,

b,

c and

d included in equation (11), which correspond to some study sub-cases.

The inverse Laplace transform of equation (15) was obtained by using the Talbot numerical method [5].

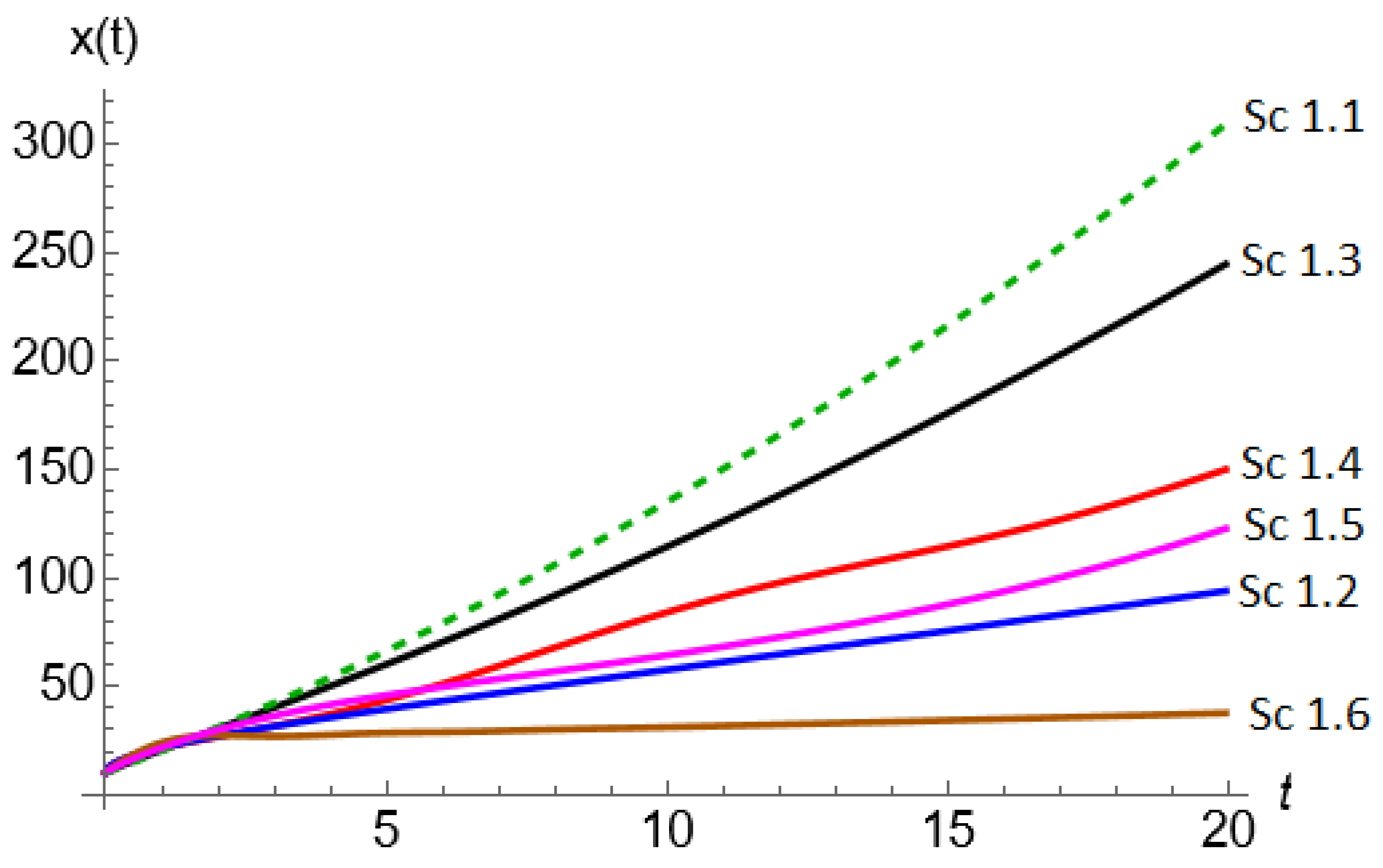

Figure 1 shows the solutions for

according to the six sub-cases compiled in

Table 1. The dashed curve corresponds to the classical integer-order model,

, which from a physical point of view can represent the uniformly accelerated rectilinear motion in “Newtonian” mechanics. The continuous curves for

=0.5 and 0.9 (sub-cases 1.2 and 1.3, respectively) correspond to the solutions of the system (10) and (11) in terms of fractional Caputo derivative operators, which physically could represent anomalous behavior (deviations) of the classical dynamics. However, this interpretation is not explored in detail in this paper, as it exceeds the scope of the present work. The curve corresponding to sub-case 1.4 was obtained for a pre-specified cosine function that describes the time evolution of the fractionl order

. What can be observed are low amplitude fluctuations in

, indicating a sort of memory effect in which the oscillations defining the behavior of

have been propagated to a certain degree in the solution curve, something similar has been reported recently in [21]. It is worth mentioning that the use of pre-established functions to define the temporal behavior of

using the Scarpi derivative has already been explored in [12] where exponential and Mittag-Leffler-type transition functions were used to define

. However, it is only very recently that a type of dynamics of the variable order

has been proposed in terms of differential equations [14], with

and

t as the dependent and independent variables, respectively. In sub-cases 1.5 and 1.6 we have considered a dynamics for

in terms of a first order differential equation in which we have also included the state variable

, as in sub-case 1.5, and the state variable

and its ordinary first derivative

, as in sub-case 1.6. These last two sub-cases, to our knowledge, represent a novelty, since a type of dynamics for

has been explored separately in terms exclusively of the state variables as in [16] or a dynamics for

has been proposed in terms exclusively of itself and its first derivative comprising a differential equation [14], as pointed out above. In

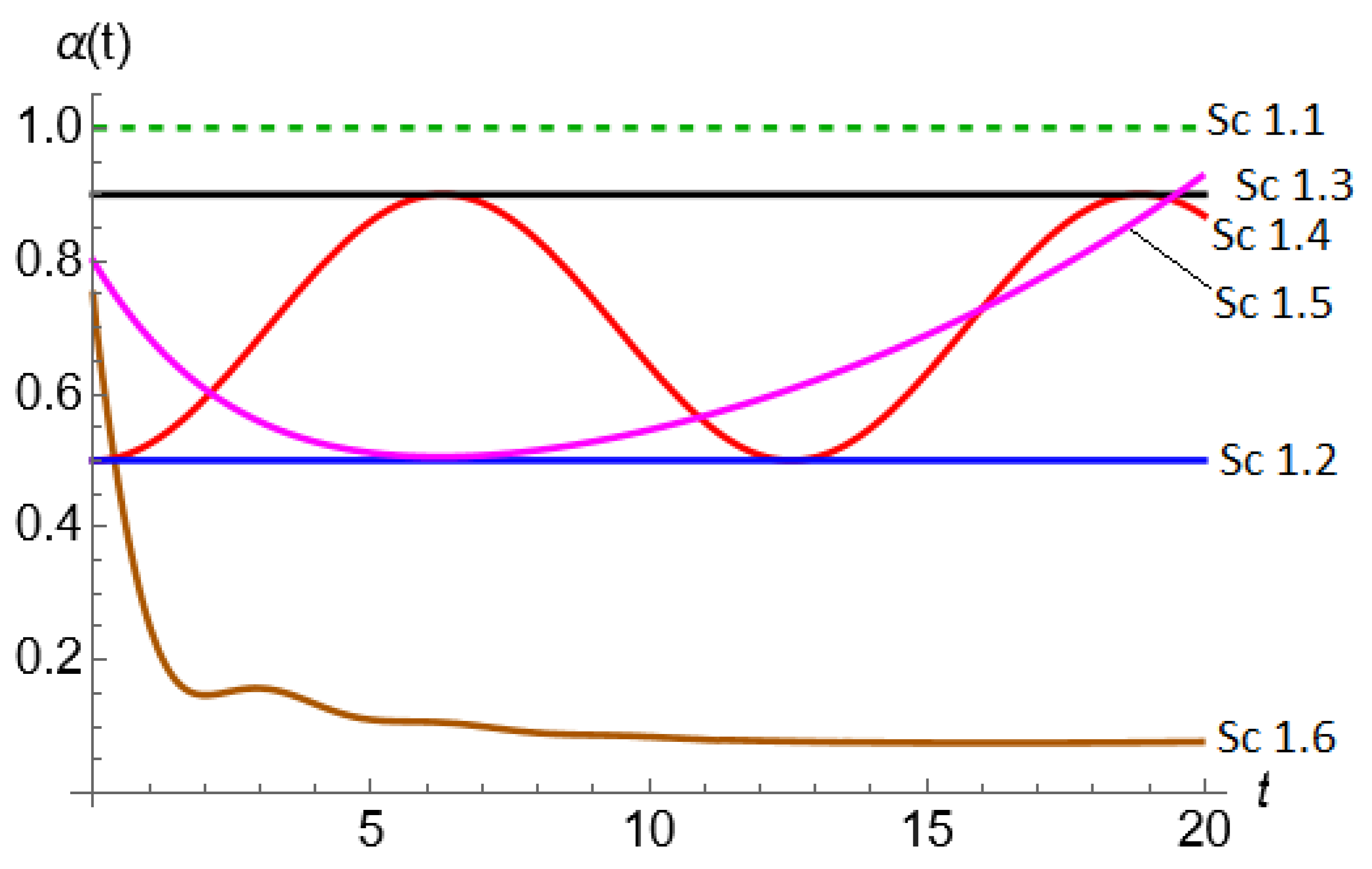

Figure 2, the different behaviors of

for the considered sub-cases are shown. One key point to emphasize in sub-cases 1.5 and 1.6 is that the dynamics of

affect the dynamics of

x and vice versa. An additional aspect to consider is that the values of

in

Figure 2 are bounded, such that they can only vary between 0 and 1. This restriction can be imposed, for example, by the physical characteristics dictated by the analyzed problem. However, by setting limits on

, it also restricts the possible number of solutions. Thus, solving sub-cases 1.5 and 1.6 involves search problems within the parameter space

so that it holds

3.2. Case 2

After applying the Laplace transform to equations (16) and (17), the following results are obtained, respectively:

The system of algebraic equations (18) and (19) has the following exact solution in terms of the Lambert function

:

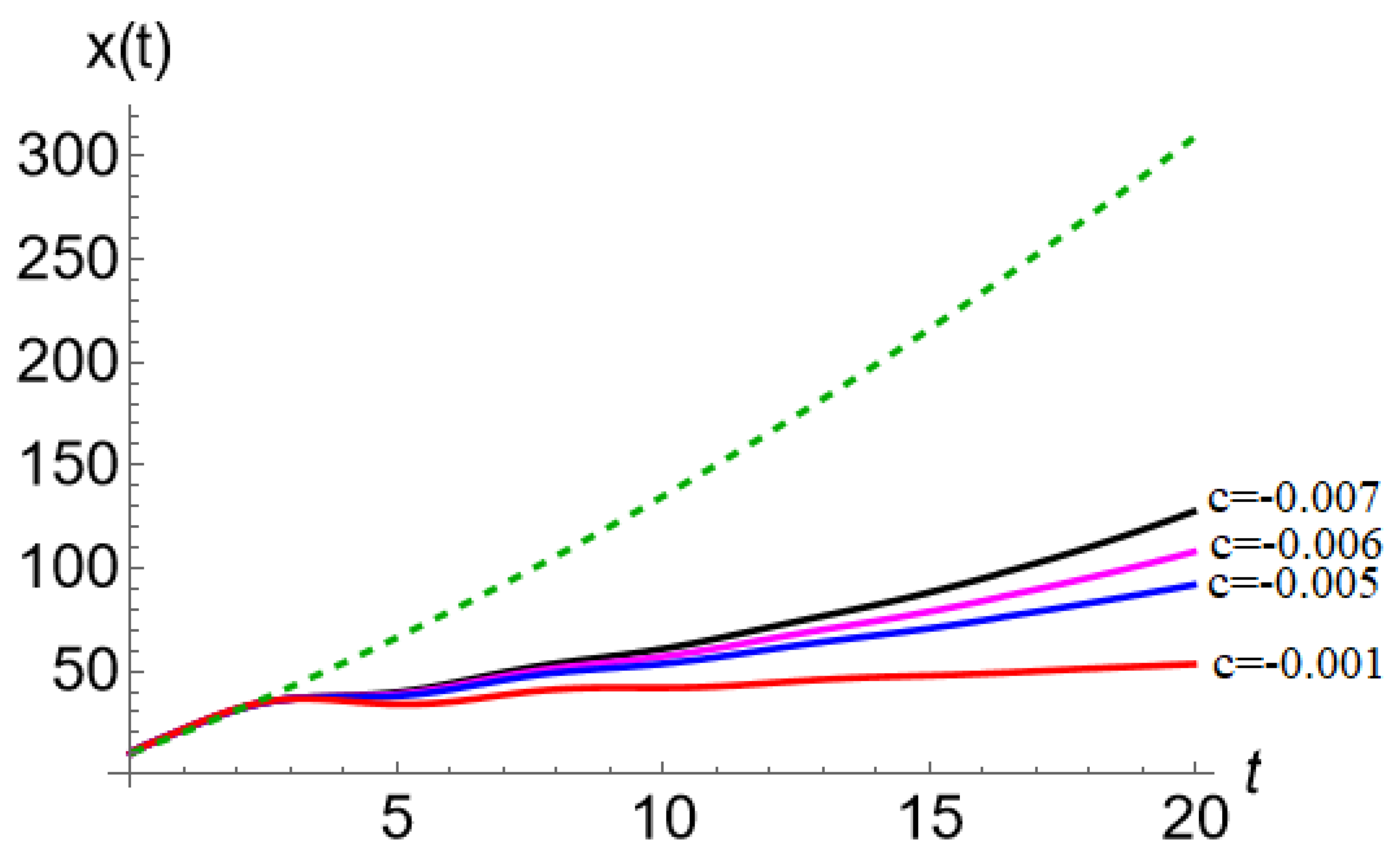

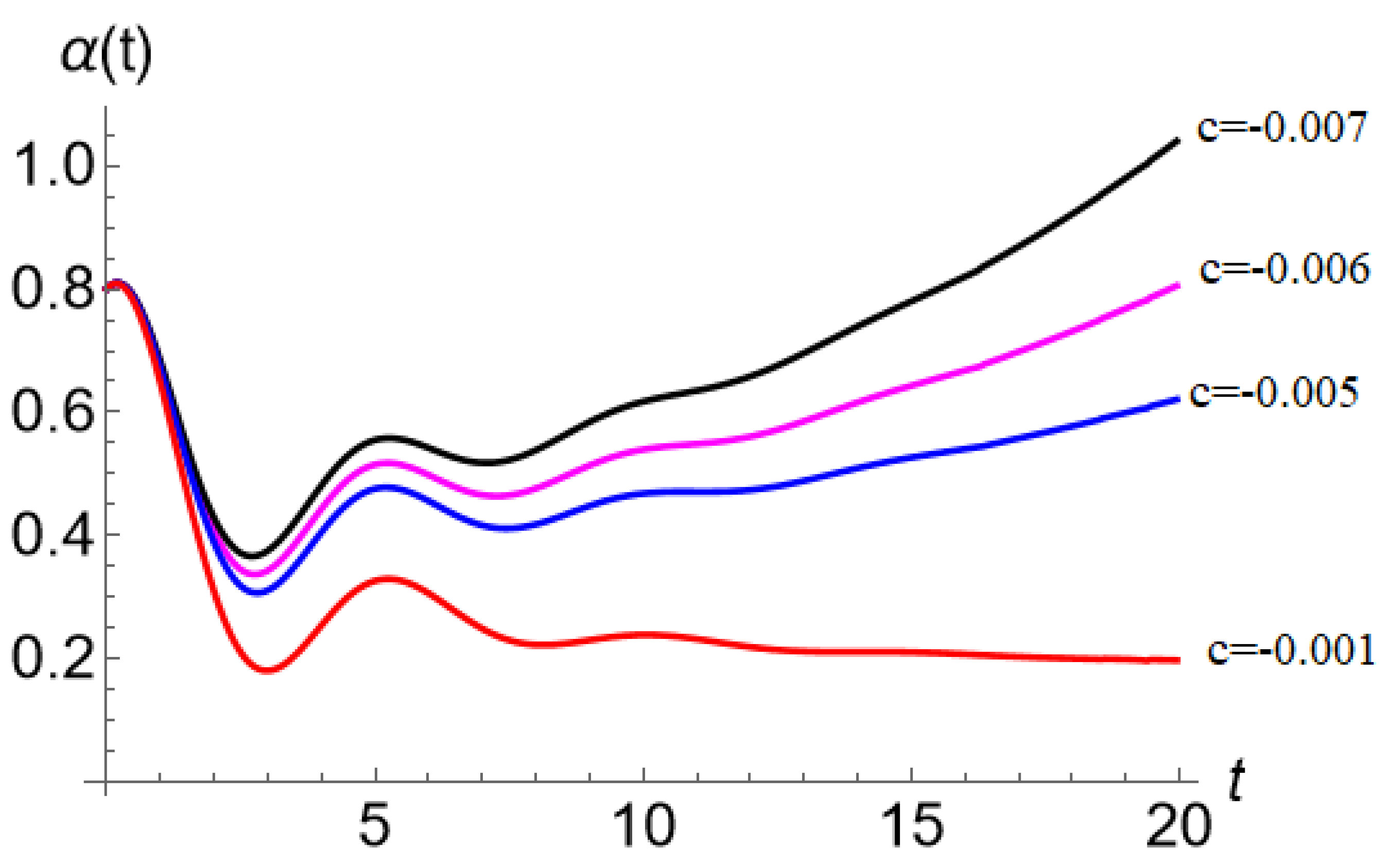

In this case, a dynamics for

is proposed in terms of an equation that combines a second-order ordinary derivative with a Caputo derivative and also includes the state variable

. The first three terms of Equation (7) set to zero represent the famous Bagley-Torvik equation [20], which is used, among other things, to model the motion of a rigid plate in a viscous fluid. For the chosen values of the parameters

b and

c, attenuated oscillatory behaviors for

are obtained; see

Figure 4. These behaviors, in turn, propagate through the solution curves

in the form of low-amplitude fluctuations, as shown in

Figure 3, following the same attenuation period of approximately 15 time units; all of which can be interpreted as a long-period memory effect [21].

3.3. Case 3

After applying the Laplace transform to Equation (24) it is obtained:

Substituting equation (25) into the result of applying the Laplace transform to equation (23), and then solving for

, yields:

Substituting equation (26) into the result of applying the Laplace transform to equation (22), and then solving for

, results in the following:

Substituting equation (27) into the result of applying the Laplace transform to equation (21), and then solving for

, yields:

In Case 3, a system has been defined in which the dynamics of

is described in terms of a Scarpi derivative of variable order

. But the order

exhibits in turn a dynamics defined by a Scarpi derivative of order

. Thus, case 3 poses a recursive process. To our knowledge, this iterative process has not been reported in the literature and offers a promising approach for modeling dynamic systems.

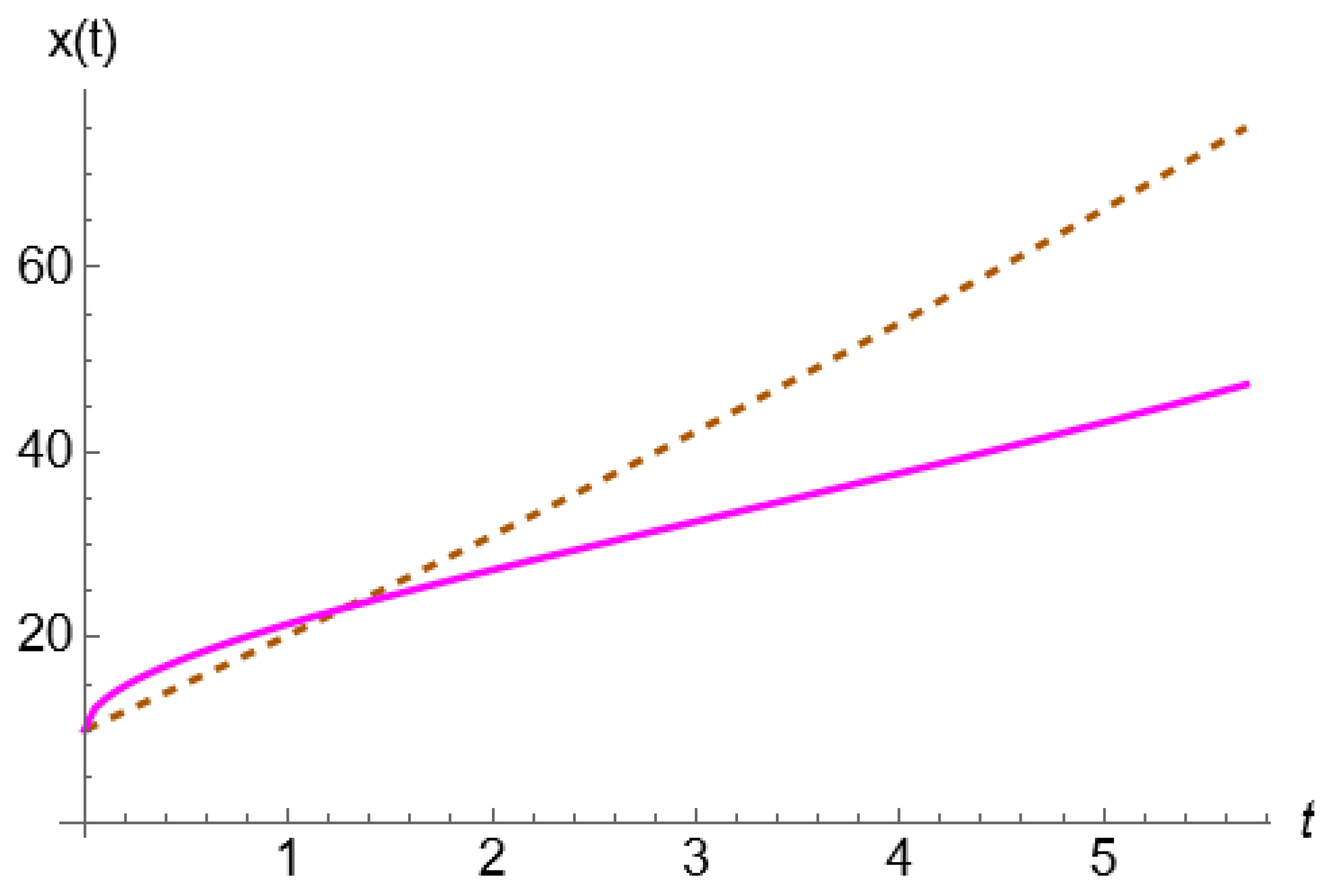

Figure 5 shows the solutions for

belonging to the classical (dashed line) and recursive (solid line) cases. There are clear differences between the two models.

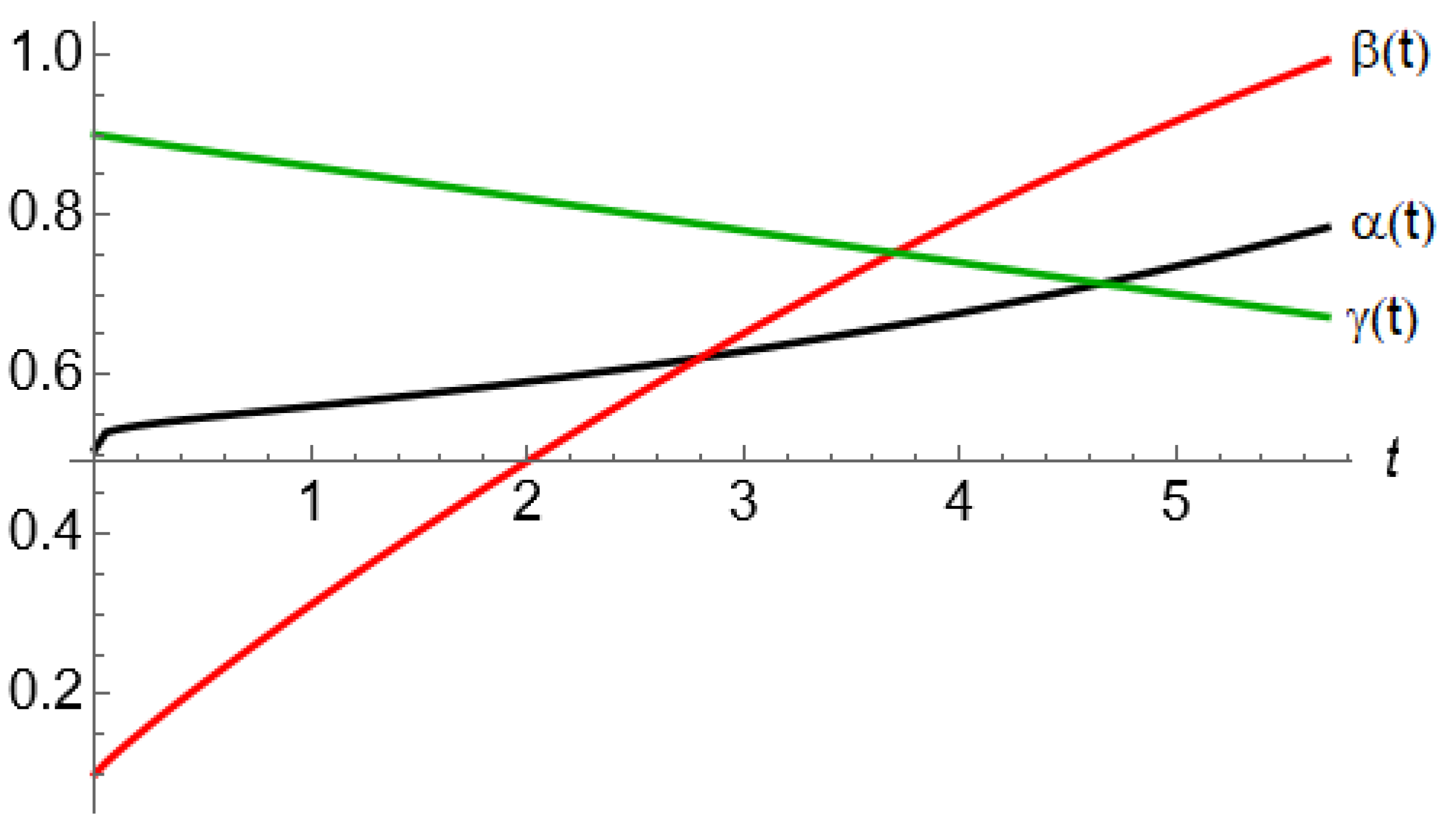

Figure 6 shows the temporal evolution of each of the three orders

,

, and

. As expected, having a system with three Scarpi derivatives (with their respective variable order) implies more restrictions in the solution search process than the one shown and discussed before in relation to Case 1. An important point to highlight is that the dynamics of

,

, and

affect the dynamic behavior of x(t), and this influence is mutual.

In the following, we present a result that generalizes Case 3.

Lemma 1. Assume a recurrent structure for the dynamic orders of the Scarpi derivatives of the following equation:

where

are positive constants and suppose all the initial conditions. Then performing the full recursive inverse dynamics for the equation

, in the domain of the Laplace transform, we obtain the following.

Proof Applying the Laplace transform to each equation, we obtain

We now proceed to make the recursive substitutions in inverse sequence, for simplicity we suppose all the initial conditions. We then use mathematical induction to obtain the result

4. Conclusions

This article presents new approaches for defining the dynamics of variable order in Scarpi’s fractional derivatives, aiming to expand their potential without delving into the physical implications. The key contributions in the three case studies are as follows:

1) The first case introduces a new dynamic for , described by a first-order differential equation that includes the state variable and its derivative , which, to our knowledge, has not been previously explored.

2) The second case proposes a second-order dynamic for , combining ordinary and fractional derivatives with the state variable , illustrating the use of different types of derivatives in defining variable order dynamics.

3) The third case presents a recursive system involving variable orders , , and , which interact and influence each other. This novel approach has not yet been addressed in the literature and contrasts significantly with traditional models.

Expanding the use of Scarpi derivatives requires the development of implicit numerical schemes to perform the Laplace inverse transform. This would eliminate the need to solve equations (14), (19), and (28) for exactly or approximately, followed by performing the inverse transform using an explicit numerical scheme like the Talbot method. The implicit schemes would enable the exploration of more complex linear models beyond the one represented by Equation (10). Moreover, it is necessary to investigate dynamic systems associated with various applications, incorporating Scarpi derivatives. Such systems could involve dynamics similar to those we have proposed or variations thereof. However, this poses two challenges: First, the use of variable-order dynamics must be justified. Second, additional work will be needed to understand its implications and interpretations within the context of the specific application being modeled. On the other hand, and to conclude, imposing limits on the order of the Scarpi derivative restricts the number of solutions to the study system, which involves a problem of searching for relevant parameters. It is necessary to find combinations of values that satisfy the imposed limits and the solution domain of interest. This approach opens new research avenues related not only to parameter search but also to system stability, among other aspects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F.A. and F.A.G; methodology, G.F.A., A.Q.A., M.P.L, R.V. and F.A.G.; Formal analysis, G.F.A. and F.A.G.; project administration, G.F.A. and F.A.G.; writing-original draft preparation, G.F.A., A.Q.A., M.P.L, R.V. and F.A.G.; writing-review and editing, G.F.A., A.Q.A., M.P.L, R.V. and F.A.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

F. A. G. is grateful for the financial support received from the DGAPA PAPIIT UNAM project number IN103124.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

In this appendix, we show how to obtain equations (15), (20) and (30). In all the solutions, we used the basic algebra, Lambert’s W function, and then we obtain .

Equation (15) was obtained as follows:

Equation (20) was obtained thus:

Equation (30) as follows:

References

- Feng, X., & Sutton, M. (2021) A new theory of fractional differential calculus. Analysis and Applications, 19(04), 715-750. [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, A. B., Mozyrska, D., & Sajewski, Ł. (2018, September). Advances in non-integer order calculus and its applications. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Non-Integer Order Calculus and Its Applications, Białystok, Poland (pp. 20-21).

- Patnaik, S., Hollkamp, J. & Semperlotti, F. Applications of variable-order fractional operators: a review. Proceedings Of The Royal Society A. 476, 20190498 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Chang, A., Zhang, Y., & Chen, W. (2019). A review on variable-order fractional differential equations: mathematical foundations, physical models, numerical methods and applications. Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis, 22(1), 27-59. [CrossRef]

- Polo-Labarrios, M., Godinez, F. A. & Quezada-Garcia, S. Numerical-analytical solutions of the fractional point kinetic model with Caputo derivatives. Annals Of Nuclear Energy. 166 pp. 108745 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. (2023). Basic theory of fractional differential equations. World scientific.

- Xu, S., Wang, X. & Ye, X. (2022). A new fractional-order chaos system of Hopfield neural network and its application in image encryption. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 157, 111889. [CrossRef]

- Ding, W., Patnaik, S., Sidhardh, S., & Semperlotti, F. (2021). Applications of distributed-order fractional operators: A review. Entropy, 23(1), 110. [CrossRef]

- Ayazi, N., Mokhtary, P. & Moghaddam, B. P. (2024). Efficiently solving fractional delay differential equations of variable order via an adjusted spectral element approach. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 181, 114635. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R., Martins, N., & Sousa, J. V. D. C. (2024). Fractional tempered differential equations depending on arbitrary kernels. AIMS Mathematics, 9(4), 9107-9127. [CrossRef]

- Scarpi, G. (1972). Sulla possibilità di un modello reologico intermedio di tipo evolutivo. Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Classe di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche e Naturali. Rendiconti, 52(6), 912-917.

- Garrappa, R., Giusti, A. & Mainardi, F. Variable-order fractional calculus: A change of perspective. Communications In Nonlinear Science And Numerical Simulation. 102 pp. 105904 (2021).

- Garrappa, R., & Giusti, A. (2023). A computational approach to exponential-type variable-order fractional differential equations. Journal of Scientific Computing, 96(3), 63. [CrossRef]

- Giusti, A., Colombaro, I., Garra, R., Garrappa, R. & Mentrelli, A. On variable-order fractional linear viscoelasticity. Fractional Calculus And Applied Analysis. pp. 1-15 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C. & Hartley, T. Variable order and distributed order fractional operators. Nonlinear Dynamics. 29 pp. 57-98 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Sheng, H., Chen, Y., Chen, W. & Yu, Z. A dynamic-order fractional dynamic system. Chinese Physics Letters. 30, 046601 (2013).

- Horvat, M. A., & Sarajlija, N. (2024). On the fractional relaxation equation with Scarpi derivative. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.03317.

- Cuesta, E., Kirane, M., Alsaedi, A., & Ahmad, B. (2021). On the sub–diffusion fractional initial value problem with time variable order. Advances in Nonlinear Analysis, 10(1), 1301-1315. [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, C. Mechanics with variable-order differential operators. Annalen Der Physik. 515, 692-703 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Atanackovic, T. & Zorica, D. On the Bagley–Torvik equation. Journal Of Applied Mechanics. 80, 041013 (2013).

- Godinez, F. A., Quezada-Garcia, S., Fernandez-Anaya, G., Quezada-Tellez, L. A. & Polo-Labarrios M. A. Variable-Order Fractional Neutron Point Kinetics Model to Nuclear Reactor. Submitted to Fractals. , (2024).

Figure 1.

Solution curves, x versus t. Numerical solutions were obtained for , , , for sub-case 1.5 and for sub-case 1.6.

Figure 1.

Solution curves, x versus t. Numerical solutions were obtained for , , , for sub-case 1.5 and for sub-case 1.6.

Figure 2.

as a function of t for different sub-cases.

Figure 2.

as a function of t for different sub-cases.

Figure 3.

Solution curves, x versus t. Numerical solutions were obtained for , , , ,. The different values of c are indicated and associated with the corresponding curve.

Figure 3.

Solution curves, x versus t. Numerical solutions were obtained for , , , ,. The different values of c are indicated and associated with the corresponding curve.

Figure 4.

versus t, for different values of the parameter c.

Figure 4.

versus t, for different values of the parameter c.

Figure 5.

Solution curves, x versus t. The discontinuous curve corresponds to the classical model of integer order, and the continuous line represents the solution for the recursive case. The following parameters were used for the solutions: , , , , , , , , , .

Figure 5.

Solution curves, x versus t. The discontinuous curve corresponds to the classical model of integer order, and the continuous line represents the solution for the recursive case. The following parameters were used for the solutions: , , , , , , , , , .

Figure 6.

Solutions corresponding to , , and . Clearly, the values taken by each of the orders, within the considered domain, are between 0 and 1.

Figure 6.

Solutions corresponding to , , and . Clearly, the values taken by each of the orders, within the considered domain, are between 0 and 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of the six subcases examined.

Table 1.

Parameters of the six subcases examined.

| Subcase |

|

b |

c |

d |

e |

|

| Sc 1.1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

1 |

| Sc 1.2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

0.5 |

| Sc 1.3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

0.9 |

| Sc 1.4 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

-1 |

|

| Sc 1.5 |

1 |

0.2 |

-0.002 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Sc 1.6 |

1 |

0.2 |

-0.001 |

0.03 |

0 |

0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).