1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death throughout the world. [

1] From 1990 to 2019, the South Asian region witnessed a substantial increase in CVD prevalence, rising by 49.6% from 3304.2 to 4944.1 cases per 100,000 individuals. CVD mortality also surged by 30.3%, climbing from 139.8 to 182.1 deaths per 100,000. [

2] These trends highlight significant health challenges, particularly in Pakistan, where CVD affects 17% of the population and constitutes the leading cause of mortality, contributing to approximately 30% of all recorded fatalities. [

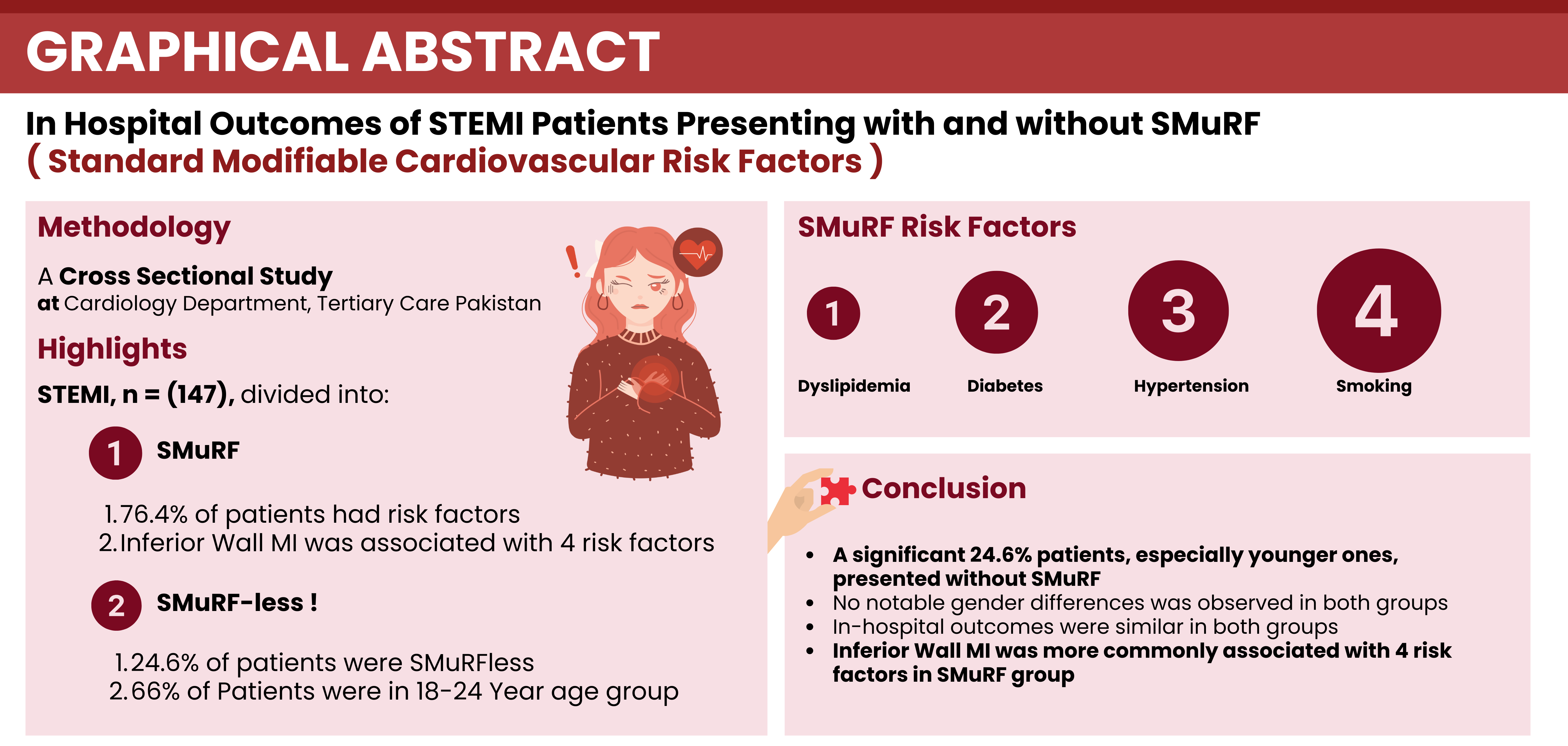

3] There are multiple conventional risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, i.e., smoking, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemias, and hypertension. These risk factors are collectively called Standard Modifiable Cardiovascular Risk Factors (SMuRFs), and patients devoid of these risk factors are called SMuRF-less. [

4] Vernon et al. collected data from the Australian registry and found that there are significant number of patients presenting without conventional risk factors and this proportion kept on increasing over time. [

5] Later on, studies were conducted in India, the, U.S.A.; and China, and results were consistent with a study conducted by Vernon et al. [

6]. Advancements in reperfusion therapies have improved AMI outcomes, but patients with delayed revascularization or large infarcts remain at risk for severe complications, including structural and arrhythmic complications with increased mortality. [

7] A significant gap exists in the outcomes of SMuRF-less STEMI patients compared to those with conventional risk factors. This study aims to find the prevalence of SMuRF-less patients and compare differences in outcomes of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients with and without traditional risk factors.

2. Materials and Methods

The data was collected from the cardiology department of a tertiary care hospital from December 2022 to December 2023. The Institutional Review Board approval was obtained under reference number Ref No. 46/IRB/SZMC/SZH. Out of the 160 patients enrolled, 10 patients' forms were missing records of complications related to myocardial infarction (MI), such as heart failure and mitral regurgitation. Therefore, these 10 patients were excluded from the study. Consultant cardiologist made the diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI). A cross-sectional descriptive type study was employed, and data was collected through a non-probability sampling technique.

The inclusion criteria for the study comprised adult patients (≥18 years) who were diagnosed with STEMI, presented within 12 hours of symptom onset with their first episode of STEMI, and underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Exclusion criteria included non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients, those under 18 years of age, and individuals with terminal conditions such as end-stage liver disease and renal disease or congestive heart failure. Patients diagnosed with STEMI at the cardiology ward were enrolled in the study if they met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and provided informed written consent. The subjects were categorized into STEMI with SMuRF and SMuRF-less STEMI. Patients with any of the following risk factors—diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, and dyslipidemia—were classified as STEMI with Standard Modifiable Cardiovascular Risk Factors (SMuRF). Those lacking these risk factors were categorized as SMuRF-less STEMI.

Data collection involved recording patient biodata, ECG findings, angiographic and echocardiographic results, and assessing complications and mortality during a 3-day hospital stay. The in-hospital outcomes included mortality, heart failure, renal failure, heart blocks, mitral regurgitation, and recurrent infarction. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23, presenting qualitative variables such as age and gender in terms of frequency and percentages. Age, sex, SMuRF, and SMuRF-less categories were controlled through stratification, and post-stratification Chi-Square tests were applied with a significance level set at p<0.05. We used logistic regression to control for confounders such as age and gender, adjusting for SMuRF status to predict in-hospital outcomes. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each outcome, and p-values were used to assess statistical significance. Risk factors were also categorized into 1-4 and compared with the type of, M.I.; angiographic findings, and left ventricular ejection fraction.

3. Results

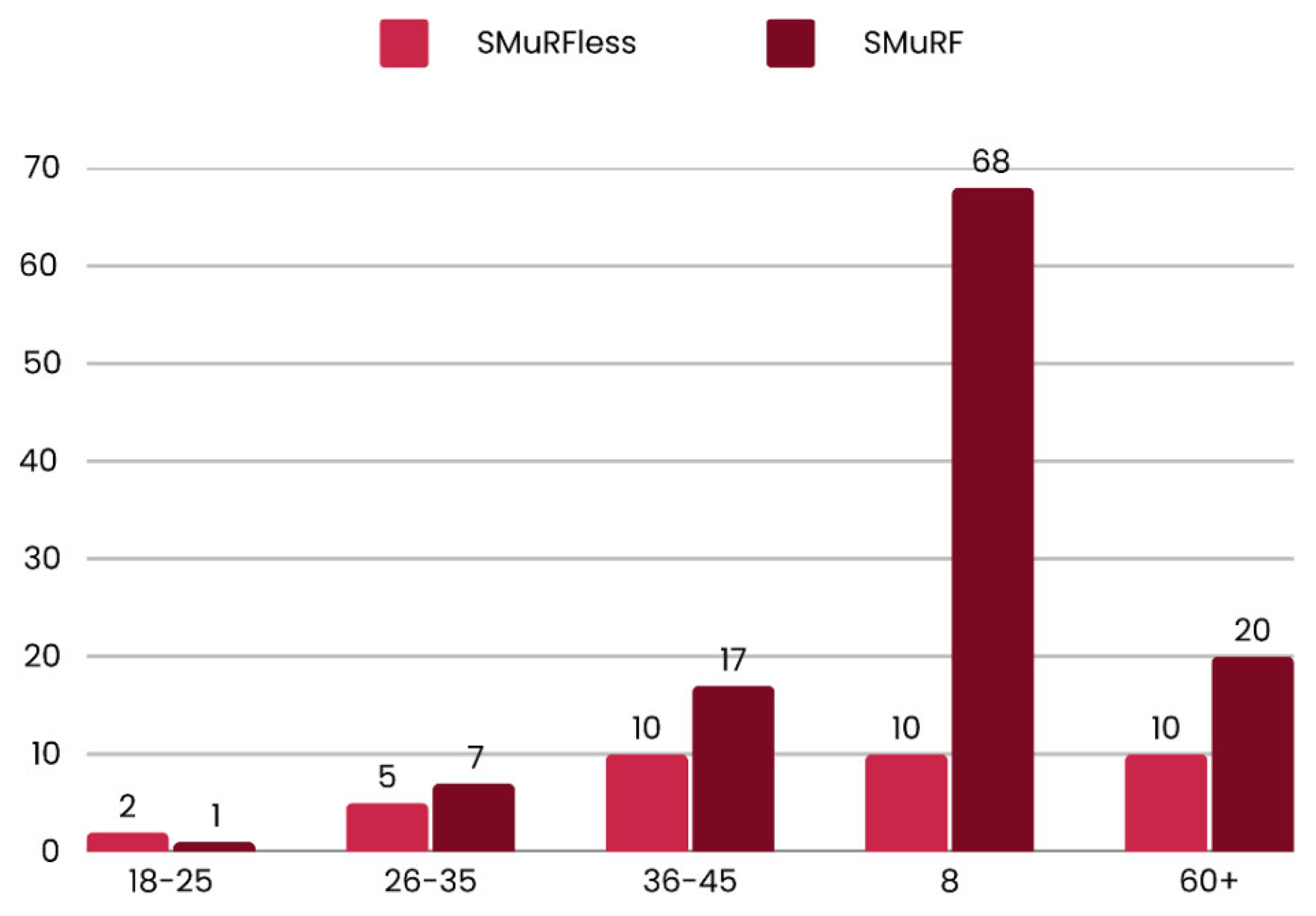

The study compared STEMI patients with SMuRF and those without SMuRF (SMuRF-less). The SMuRF-less group comprised 37 (24.6%) of the total sample 150. The age distribution of the two groups showed that the SMuRF-less group had a higher proportion of younger patients (18-25 years) than the SMuRF group (66% vs 33%). The SMuRF group had a higher proportion of middle-aged patients (46-60 years) than the SMuRF-less group (n=68, 87.17% vs n=10, 12.82%, p<0.05). These findings are depicted in

Figure 1.

The gender distribution revealed a higher proportion of male patients in the SMuRF group (72.41%) compared to the SMuRF-less group (27.58%), with a more asymmetrical distribution of female patients between the two groups (SMuRF-less=14.7% and SMuRF=85.3%) resulting in an overall sample of 77.33% male and 22.66% female. The prevalence of risk factors in the SMuRF group included smoking (50.44%), dyslipidemia (38.94%), diabetes mellitus (38.05%), and hypertension (55.75%). Family history was found in 16.21% of the SMuRF-less group and 24.13% of the SMuRF group.

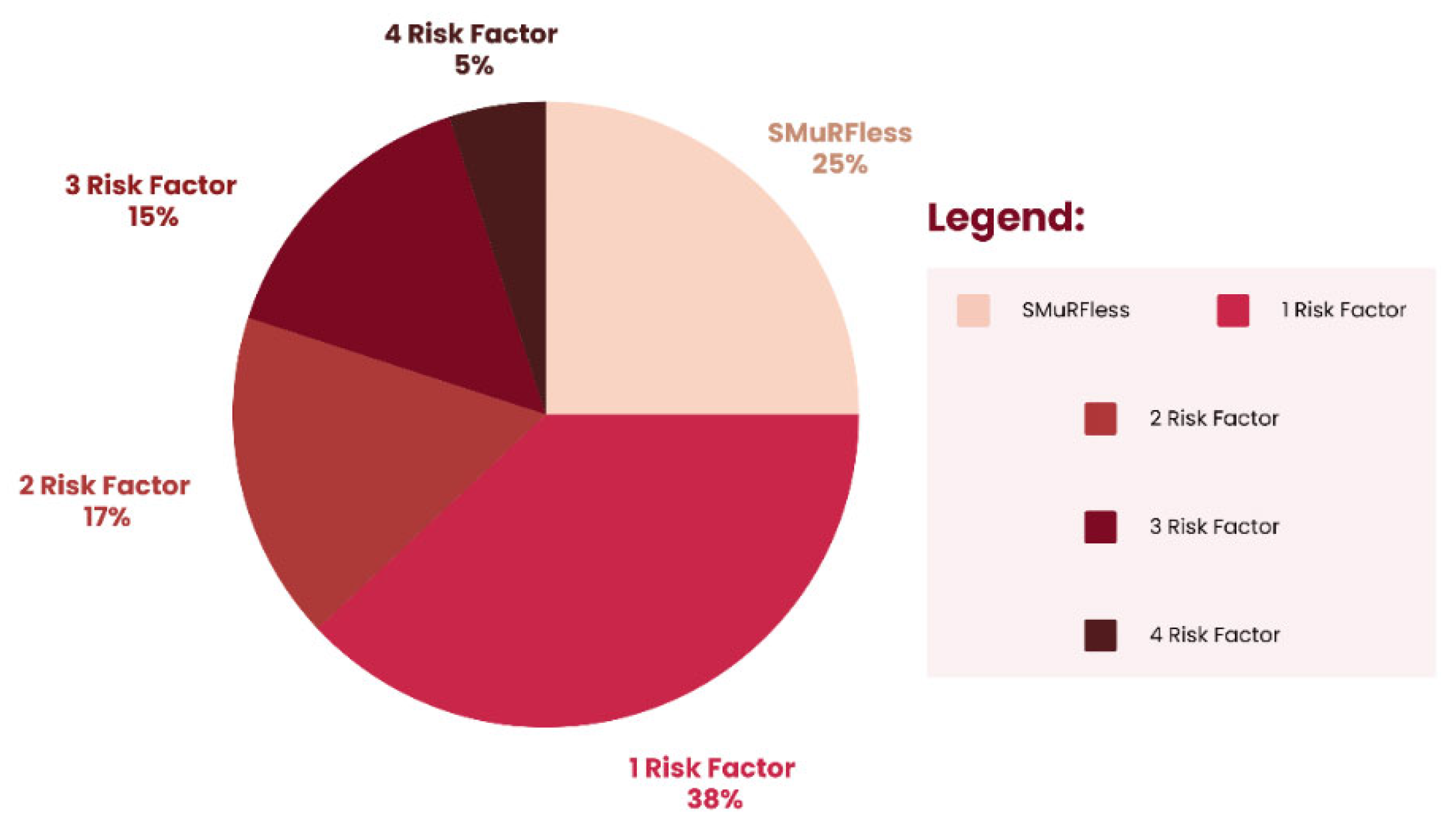

Table 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the distribution of individuals based on the number of risk factors they possess. Most (38%) have one risk factor, followed by 25% with no risk factors. Smaller percentages are seen for those with 2, 3, or 4 risk factors.

AWMI in the SMuRF group was 71.56%, compared to 28.43% in the SMuRF-less group, while IWMI in the SMuRF group was 83.33%, compared to 16.67% in the SMuRF-less group. The research investigated the distribution of coronary artery disease across three categories: SVCAD (SMuRF = 76.29%, SMuRF-less = 23.70%), 2VCAD (SMuRF = 55.55%, SMuRF-less = 44.44%), 3VCAD (SMuRF = 83.33%, SMuRF-less = 16.67%). We explored the distribution of patients across various ejection fraction ranges, including 51-60, 41-50, 31-40, and below 30. Most patients were in the 31-40 range; nine (23.07%) were SMuRF-less, and 30 (76.92%) were from the SMuRF group as shown in

Table 2.

Table 3 shows that SCVAD was most commonly associated with one risk factor, 52 (50.98%). MVCAD is predominantly exhibited by four risk factors, 40% vs 4.9% SVCAD, with a significant association of p<0.05. Among patients with one risk factor, 39.13% had an ejection fraction in the 51-60% range, while 50% had an ejection fraction below 30%. In contrast, among patients with four risk factors, 13% had an ejection fraction in the 51-60% range, and 5.5% had an ejection fraction below 30%.

The provided data outlined the distribution of MI types, categorized as AWMI and IWMI, across different risk factor categories. IWMI was predominantly associated with four risk factors as compared to AWMI (12.5% vs. 2.7%) with a statistical significance (p=0.021).

Table 4 illustrates in-hospital outcomes among patients categorized as SMuRF and SMuRF-less. These outcomes include heart failure, mitral regurgitation, heart block, recurrent infarction, renal failure, and death. No deaths were reported among the patient cohort during the observation period. While there were variations in the incidence of specific complications between the SMuRF and SMuRF-less groups, the differences observed were not statistically significant for most outcomes.

4. Discussion

The study found that the SMuRF-less group had a higher proportion of younger patients, while the SMuRF group had more middle-aged patients. Inferior wall myocardial infarction (IWMI) and multi-vessel coronary artery disease (MVCAD) were more common in the SMuRF-less group. In-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups, with no deaths reported.

The present study compared the SMuRF and SMuRF-less proportion (75.33% vs 24.6%), which is consistent with other studies conducted in India (25.4%), USA (26.6%), and Australia (19%). [

6,

7,

8] Another study in Pakistan reported that 15% of patients without SMuRFs had a greater mortality rate. [

9] The presence of SMuRF-less STEMI patients underscores the necessity of identifying new biomarkers and pathophysiology of atherosclerosis beyond traditional risk factors. This study showed no significant gender difference between SMuRF and SMuRF-less groups. Studies showed that more males were SMuRF-less than females, consistent with various studies and another study by Paul et al. SMuRF-less status is more common in females (27.1%). [

10,

11,

12] These contrasting results suggest that the prevalence of SMuRF-less status may vary between different populations or study cohorts. Understanding these differences can help develop targeted interventions and strategies for preventing and managing cardiovascular diseases in specific populations. SMuRF-less status is more common in the younger age group, which varies with other studies. [

11,

13] The incidence of STEMI is generally low in younger age groups. However, the absence of traditional risk factors for STEMI in younger individuals may be attributed to genetic predisposition. Therefore, genetic testing should be considered for high-risk individuals in this age group.

Among the SMuRF group, Hypertension was the most prevalent risk factor, preceded by diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemias, and smoking. [

6,

11,

12] It is important to note, however, that there may be a risk of patients underreporting their actual smoking habits, which could result in an exaggerated number of patients classified as former smokers, as well as cases of undiagnosed hypertension. The SMuRF group had a higher proportion of AWMI than the SMuRF-less group, consistent with a study conducted in India. [

6] Research is needed to fully understand the underlying reasons for the observed differences in AWMI between the SMuRF and SMuRF-less groups. SVCAD was most prevalent among the SMuRF group, while 2VCAD and 3VCAD were also found predominantly in the SMuRF group. [

13] This suggests that individuals within the SMuRF group may have a higher propensity or risk for coronary artery diseases compared to the SMuRF-less group. Environmental factors such as exposure to pollution, socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, and quality of healthcare can influence the development and progression of coronary artery disease. The SMuRF group may be more susceptible to certain environmental factors that contribute to the development of these conditions.

Discussing the ejection fraction and its comparison with SMuRF vs. SMuRF-less groups, most SMuRF group patients lie in the 31-40% ejection fraction group. In contrast, the number of SMuRF-less group patients potentially decreases from higher to lower ejection fraction, which shows that SMuRF-less group patients experience less severe consequences than the SMuRF group, consistent with other studies. [

9] However, a study conducted in India shows that the SMuRF-less group experiences decreased ejection fraction compared to the SMuRF group. Still, none of the studies showed this relation to be significantly associated (p<0.05). [

6]

SCVAD is most frequently associated with a single risk factor, whereas MVCAD is primarily observed in patients with four risk factors. These findings are consistent with those reported by Li S et al. in their study. [

14] In clinical practice, understanding the association between several risk factors and the type of coronary artery disease can help in risk assessment, prevention strategies, and treatment planning. Preserved ejection fraction is most commonly associated with one risk factor, while in 4 risk factors, this proportion consistently decreased. [

15,

16] In the present study, AWMI was most dominantly present, while IWMI showed an increased incidence in patients with four risk factors with a statistical significance of p<0.05. [

17] Understanding these patterns can inform clinical practice risk assessment, treatment strategies, and preventive measures. Further analysis may be warranted to explore these findings' underlying mechanisms and implications.

We didn’t observe any hospital mortality in either of the study groups (SMuRF vs SMuRF-less). Our findings align with those of GJ Paul et al., while Vernon et al. reported higher mortality in the SMuRF-less group. [

5,

6] Vernon et al. suggested that the increased mortality could be attributed to the heart muscles' inability to tolerate ischemia or biological variations. In our study, the lack of difference in mortality between the two groups may be due to focusing solely on in-hospital mortality. However, Figtree et al. examined 30-day and 1-year mortality rates in both groups and found similar results. The debate on mortality differences between the groups has been ongoing, and further research is needed to investigate the underlying mechanisms. We couldn’t find any statistically significant difference between both groups while comparing hospital outcomes, including Heart Failure, Mitral Regurgitation, Heart Block, re-infarct (Recurrent Infarction), and Renal Failure. Research has shown that non-modifiable factors, such as age, genetics, and the extent of coronary artery disease at presentation, can independently affect outcomes regardless of the SMuRF status. [

18] In the acute setting, factors such as the severity of infarction, timely medical response, and patient adherence to treatment can play a more critical role in determining in-hospital outcomes than the mere presence or absence of conventional risk factors.

5. Conclusions

The study's findings underscored that a significant number of patients (25%) present without SMuRF, particularly in the younger age group. In addition, inferior wall myocardial infarction was predominantly associated with the presence of four risk factors. Interestingly, the study revealed no discernible difference in in-hospital outcomes between patients with SMuRF and those without, suggesting that the SMuRF-less status does not necessarily correlate with worse outcomes during hospitalization.

6. Limitations

The study acknowledges several limitations. Firstly, the sample size of 150 patients was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the exclusive focus on in-hospital outcomes limits the ability to assess long-term differences between both groups. Moreover, excluding NSTEMI patients may have omitted potentially significant findings that could apply to a broader range of acute coronary syndromes. Future research should aim to explore the long-term outcomes of SMuRF-less patients and examine potential genetic or environmental factors that may contribute to their risk profiles. Such studies would provide more robust data to accurately evaluate and compare outcomes between SMuRF and SMuRF-less patients, offering valuable insights into cardiovascular risk assessment and management strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Muhammad Khalid Razaq, Anfal Hamza, Muhammad Umair Choudhary; Methodology: Anfal Hamza, Hanzala Jehangir; Formal analysis and investigation: Ali Ayan, Brijesh Sathian, Anfal Hamza; Writing - original draft preparation: Anfal Hamza, Mohammad Hamza Bin Abdul Malik, Saman Firdous, Muhammad Arham; Writing - review and editing: Muhammad Khalid Razaq, Mohammad Hamza Bin Abdul Malik, Syed Muhammad Ali, Muhammad Arham; Funding acquisition: Javed Iqbal, Brijesh Sathian, Syed Muhammad Ali; Resources: Muhammad Khalid Razaq; Supervision: Muhammad Khalid Razaq

Funding

The Qatar National Library supported this research through its funding for open-access publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were by the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Medical College (Ref No. 46/IRB/SZMC/SZH).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the nursing staff of the cardiology ward for their invaluable cooperation and dedication in facilitating the follow-up of patients throughout the study. We also sincerely thank Dr. Gemma Figtree for her invaluable feedback and guidance during the review of this article. Finally, we thank the Qatar National Library for funding this research's publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The funding support from the Qatar National Library did not influence the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the results.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used Grammarly to ensure a formal tone, improve rephrasing, and correct punctuation. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SMURF |

Standard Modifiable Risk Factors |

| IWMI |

Inferior Wall Myocardial Infarction |

| AWMI |

Anterior Wall Myocardial Infarction |

| STEMI |

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

References

- Cardiovascular diseases. Who.int. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases.

- Shaikh, N.A.; Talpur, M.F.H.; Shah, S.A.; Kumar, R.; Bhatti, K.I.; Ashraf, T.; Samad, A.; Hussain, S.T. Awareness and knowledge sharing among physicians regarding influenza and pneumococcal vaccines for cardiovascular patients. Pak Hear J 2022, 55, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, Z.; Hanif, B. Cardiovascular diseases in Pakistan: Imagining a postpandemic, postconflict future. Circulation 2023, 147, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, G.; Chin, Y.H.; Chong, B.; Goh, R.S.J.; Lim, O.Z.H.; Ng, C.H.; Muthiah, M.; Foo, R.; Vernon, S.T.; Loh, P.H.; Chan, M.Y.; Chew, N.W.S.; Figtree, G.A. Higher mortality in acute coronary syndrome patients without standard modifiable risk factors: Results from a global meta-analysis of 1,285,722 patients. Int J Cardiol 2023, 371, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernon, S.T.; Coffey, S.; D’Souza, M.; Chow, K.C.; Kilian, J.; Hyun, K.; Shaw, J.A.; Adams, M.; Robert-Thomson, P.; Brieger, D.; Figtree, G.A. ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients without standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors—how common are they, and what are their outcomes? J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, G.J.; Sankaran, S.; Saminathan, K.; Iliyas, M.; Sethupathy, S.; Saravanan, S.; Prabhu, S.S.; Kurian, S.; Srinivas, S.; Anurag, P.; Srinivasan, K.; Manimegalai, E.; Nagarajan, S.; Ramesh, R.; Nageswaran, P.M.; Sangareddi, V.; Govindarajulu, R. Outcomes of, S.T. segment elevation myocardial infarction without standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors – newer insights from a prospective registry in India. Glob Heart, 2023; 18. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.K.; Hellkamp, A.S.; Armstrong, P.W.; Cohen, E.; Kleiman, N.S.; O’Connor, C.M.; Holmes, D.R.; Hochman, J.S.; Granger, C.B.; Mahaffey, K.W. Mechanical complications after percutaneous coronary intervention in, S. T.-elevation myocardial infarction (from, A.P.EX-AMI). Am J Cardiol 2010, 105, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Shamaki, G.R.; Safiriyu, I.; Kesiena, O.; Mbachi, C.; Anyanwu, M.; Zahid, S.; Rai, D.; Bob-Manuel, T.; Corteville, D.; Alweis, R.; Batchelor, W.B. Prevalence and outcomes in, S.T.EMI patients without standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors: A national inpatient sample analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol 2022, 47, 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, S.; Peerwani, G.; Hanif, B.; Virani, S. Clinical characteristics, management, and 5-year survival compared between no standard modifiable risk factor (SMuRF-less) and ≥ 1 SMuRF ACS cases: an analysis of 15,051 cases from Pakistan. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.; Lan, N.S.R.; Phan, J.; Hng, C.; Matthews, A.; Rankin, J.M.; Schultz, C.J.; Hillis, G.S.; Reid, C.M.; Dwivedi, G.; Figtree, G.A.; Ihdayhid, A.R. Characteristics and outcomes of young patients with, S.T.-elevation myocardial infarction without standard modifiable risk factors. Am J Cardiol 2023, 202, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.L.; Knight, S.; May, H.T.; Le, V.T.; Almajed, J.; Bair, T.L.; Knowlton, K.U.; Muhlestein, J.B. Cardiovascular outcomes of, S.T.-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients without standard modifiable risk factors (SMuRF-less): The Intermountain Healthcare experience. J Clin Med 2022, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazhar, J.; Ekström, K.; Kozor, R.; Grieve, S.M.; Nepper-Christensen, L.; Ahtarovski, K.A.; Kelbæk, H.; Høfsten, D.E.; Køber, L.; Vejlstrup, N.; Vernon, S.T.; Engstrøm, T.; Lønborg, J.; Figtree, G.A. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with, S.T.-elevation myocardial infarction and no standard modifiable risk factors–A DANAMI-3 substudy. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 945815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazhar, J.; Ekström, K.; Kozor, R.; Grieve, S.M.; Nepper-Christensen, L.; Ahtarovski, K.A.; Kelbæk, H.; Høfsten, D.E.; Køber, L.; Vejlstrup, N.; Vernon, S.T.; Engstrøm, T.; Lønborg, J.; Figtree, G.A. Ethnic disparities in, S.T.-segment elevation myocardial infarction outcomes and processes of care in patients with and without standard modifiable cardiovascular risk factors: A nationwide cohort study. Angiology 2024, 75, 742–753. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Gao, X.; Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Fu, R.; Dong, Q.; Sun, H.; Yan, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, C.; Li, W.; Yang, Y. Number of standard modifiable risk factors and mortality in patients with first-presentation, S.T.-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from China Acute Myocardial Infarction registry. BMC Med, 2022; 20. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, T.; Kusunose, K.; Zheng, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hirata, Y.; Nishio, S.; Saijo, Y.; Ise, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yagi, S.; Yamada, H.; Soeki, T.; Wakatsuki, T.; Sata, M. Association between cardiovascular risk factors and left ventricular strain distribution in patients without previous cardiovascular disease. J Echocardiogr 2022, 20, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled, S.; Matahen, R. Cardiovascular risk factors profile in patients with acute coronary syndrome with particular reference to left ventricular ejection fraction. Indian Heart J 2018, 70, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Chomayil, Y.; Karim, F.A.; Poovathum Parambil, V. Incidence and risk factors of acute coronary syndrome in younger age groups. Int J Emerg Med 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incalcaterra, E.; Hoffmann, E.; Averna, M.R.; Caimi, G. Genetic risk factors in myocardial infarction at young age. Minerva Cardioangiol 2004, 52, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of, M.D.PI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).