Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

Sample Collection

The Analysis of Water Quality

| Water Quality indicators | Analytical instruments |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Thermometer |

| Total dissolved solid | Total dissolved solids, Mettler Toledo, Model CH-8603 |

| Dissolved oxygen | DO meter, Mettler Toledo, Model 966 |

| Electro-conductivity | EC meter, Mettler Toledo, Model CH-8603 |

| pH | pH meter, Eutech, Model EcoScan pH 5 |

Measurement of Heavy Metal Concentration in Water

Measurement of Heavy Metal Concentration in Sediment

Measurement of Heavy Metal Concentration in Tilapia Fish

Quality Control and Quality Assurance

Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF)

Estimated Daily Intake (EDI)

The Health Risk Index (HRI)

Carcinogenic Risk (CR)

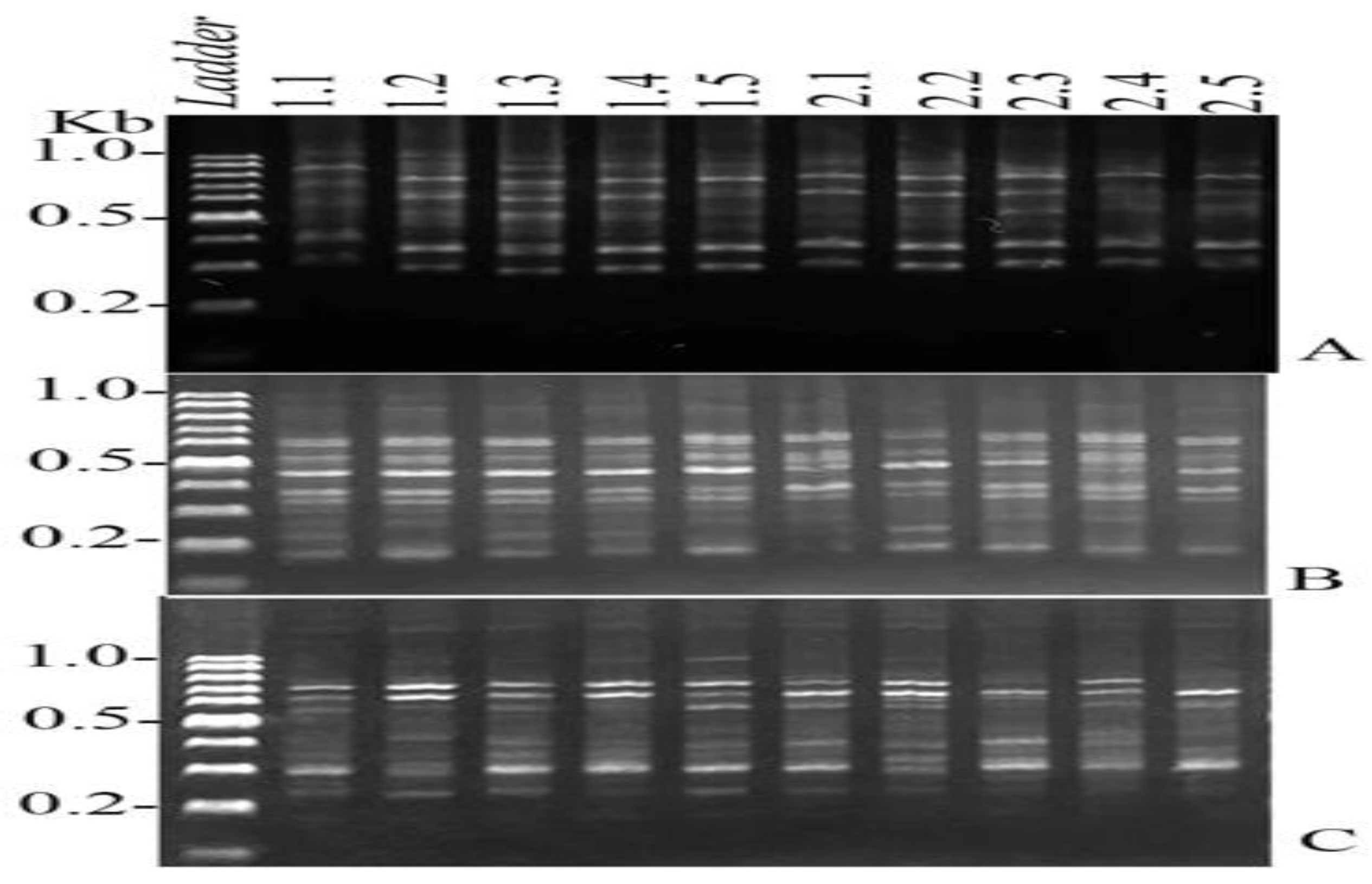

DNA Extraction and PCR Analysis

Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

Statistical Analysis

Results

Water Quality

Heavy Metal Concentrations in Water and Sediment

Heavy Metal Concentrations in Tilapia Fish

The Fish Sample's BAFs of Heavy Metals

Possible Hazards to Human Health from Consuming Fish That Contains Heavy Metals

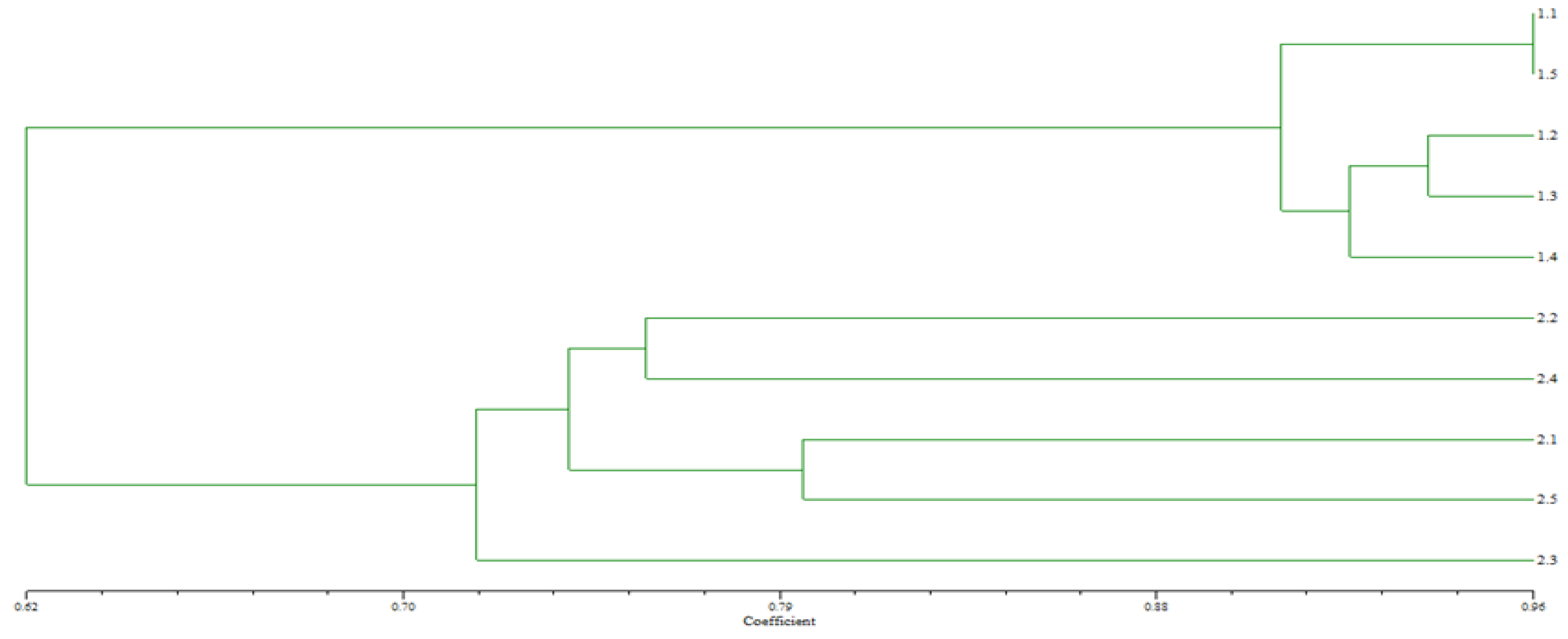

Genotoxicity

Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

Discussion

Water Quality Parameters

Heavy Metal Concentrations in Water, Sediment and Tilapia Fish

BAFs of Heavy Metals in the Fish Samples

Possible Harmful Effects of Heavy Metals on Health via Fish Consumption

Genetic Differentiation

Oxidative Stress

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Siriratpiriya, O. Municipal Solid Waste Management in Thailand: Challenges and Strategic Solution. Municipal solid waste management in Asia and the Pacific Islands: Challenges and strategic solutions.

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Sajad, M. A. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals-Concepts and Applications. Chemosphere, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chuangcham, U.; Wirojanagud, W.; Charusiri, P.; Milne-Home, W.; Lertsirivorakul, R. Assessment of Heavy Metals from Landfill Leachate Contaminated to Soil: A Case Study of Kham Bon Landfill, Khon Kaen Province, NE Thailand. Journal of Applied Sciences 2008, 8, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intamat, S.; Buasriyot, P.; Sriuttha, M.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Neeratanaphan, L. Bioaccumulation of Arsenic in Aquatic Plants and Animals near a Municipal Landfill. International Journal of Environmental Studies 2017, 74, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchuwararak, P.; Intamat, S.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Neeratanaphan, L. Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in Local Edible Plants near a Municipal Landfill and the Related Human Health Risk Assessment. Human and ecological risk assessment: an international journal.

- Ruchuwararak, P.; Intamat, S.; Neeratanaphan, L. Genetic Differentiation and Bioaccumulation Factor After Heavy Metal Exposure in Edible Aquatic Plants Near a Municipal Landfill. EnvironmentAsia 2020, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Thanomsangad, P.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Sriuttha, M.; Neeratanaphan, L. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Frogs Surrounding an E-Waste Dump Site and Human Health Risk Assessment. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal.

- Ali, H.; Khan, E. Bioaccumulation of Non-Essential Hazardous Heavy Metals and Metalloids in Freshwater Fish. Risk to Human Health. Environ Chem Lett 2018, 16, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-González, M. I.; Méndez-Armenta, M. Heavy Metals: Implications Associated to Fish Consumption. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2008, 26, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authman, M. M. N.; Zaki, M. S.; Khallaf, E. A.; Abbas, H. H. Use of Fish as Bio-Indicator of the Effects of Heavy Metals Pollution. J Aquac Res Dev 2015, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S.; Molla, A. H.; Saha, N.; Rahman, A. Study on Heavy Metals Levels and Its Risk Assessment in Some Edible Fishes from Bangshi River, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Food Chem 2012, 134, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeratanaphan, L.; Khamlerd, C.; Chowrong, S.; Intamat, S.; Sriuttha, M.; Tengjaroenkul, B. Cytotoxic Assessment of Flying Barb Fish (Esomus Metallicus) from a Gold Mine Area with Heavy Metal Contamination. International Journal of Environmental Studies 2017, 74, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Oost, R.; Beyer, J.; Vermeulen, N. P. E. Fish Bioaccumulation and Biomarkers in Environmental Risk Assessment: A Review. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2003, 13, 57–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuemesi, F. E.; Onuba, L. N.; Chiaghanam, O. I.; Anudu, G. K.; Akanwa, A. O. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Fish of Ivo River, Ishiagu Nigeria. Research Journal of Environmental and Earth Sciences 2013, 5, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association (2005). APHA Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. American Water Works Association and Water Environment Federation.

- Sriuttha, M.; Khammanichanh, A.; Patawang, I.; Tanomtong, A.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Neeratanaphan, L. Cytotoxic Assessment of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) from a Domestic Wastewater Canal with Heavy Metal Contamination. Cytologia (Tokyo) 2017, 82, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. I.; Li, Y.; Xj, G.; Ma, X.; Yan, Q. Comparison of Dry Ashing, Wet Ashing and Microwave Digestion for Determination of Trace Elements in Periostracum Serpentis and Periostracum Cicadae by ICP-AES. Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society 2013, 58, 1876–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, V.; Prasad, S. ICP-OES Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination in Tropical Marine Sediments: A Comparative Study of Two Digestion Techniques. Microchemical Journal 2013, 111, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingkhwan, R.; Worakhunpiset, S. Heavy Metal Contamination near Industrial Estate Areas in Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya Province, Thailand and Human Health Risk Assessment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrhovnik, P.; Arrebola, J. P.; Serafimovski, T.; Dolenec, T.; Šmuc, N. R.; Dolenec, M.; Mutch, E. Potentially Toxic Contamination of Sediments, Water and Two Animal Species in Lake Kalimanci, FYR Macedonia: Relevance to Human Health. Environmental pollution 2013, 180, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. 2017. Regional Screening Level (RSL) Resident Soil to GW Table (TR = 1E-06, HQ = 1) 17. Available at https://semspub.epa.gov/work/HQ/197049. 20 November.

- Shaheen, N.; Irfan, N. M.; Khan, I. N.; Islam, S.; Islam, M. S.; Ahmed, M. K. Presence of Heavy Metals in Fruits and Vegetables: Health Risk Implications in Bangladesh. Chemosphere 2016, 152, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeratanaphan, L.; Kamollerd, C.; Suwannathada, P.; Suwannathada, P.; Tengjaroenkul, B. Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Experimental Hybrid Catfish Exposed to Heavy Metals in a Municipal Landfill Reservoir. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohlf, F. J. NTSYSpc Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis System Version 2. 0 User Guide. 1998.

- Farombi, E. O.; Adelowo, O. A.; Ajimoko, Y. R. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Heavy Metal Levels as Indicators of Environmental Pollution in African Cat Fish (Clarias Gariepinus) from Nigeria Ogun River. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2007, 4, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartono, E.; Yunanto, A.; Firdaus, R. T. Chronic Cadmium Hepatooxidative in Rats: Treatment with Haruan Fish (Channa Striata) Extract. APCBEE procedia 2013, 5, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S. A.; Nambi, K. S. N.; Taju, G.; Vimal, S.; Venkatesan, C.; Hameed, A. S. S. Cytotoxicity, Genotoxicity and Oxidative Stress of Malachite Green on the Kidney and Gill Cell Lines of Freshwater Air Breathing Fish Channa Striata. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, 13539–13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadwan, M. H.; kadhum Ali, S. New Spectrophotometric Assay for Assessments of Catalase Activity in Biological Samples. Anal Biochem 2018, 542, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thailand Pollution Control Department (TPCD), 2001, Water Quality Standards. Notification in Ministry of Public Health. No. 98, (Bangkok: Thailand Pollution Control Department).

- Thailand Pollution Control Department (TPCD) 1994. Surface Water Quality Standards. Notification of the National Environmental Board, No. 8. Thailand Pollution Control Department (TPCD) 1994. Surface Water Quality Standards. Notification of the National Environmental Board, No. 8. TPCD, Bangkok.

- Thailand Pollution Control Department (TPCD) 2004. Soil Quality Standards for Habitat and Agriculture. Notification of the Nation al Environmental Board, No. 25. Thailand Pollution Control Department (TPCD) 2004. Soil Quality Standards for Habitat and Agriculture. Notification of the Nation al Environmental Board, No. 25. TPCD, Bangkok.

- Ministry of Public Health. Standard of Contaminants in Food, Notification of the Ministry of Public Health No. 273/2; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A. K. M. A.; Maksud, M. A.; Khan, S. R.; Lutfa, L. N.; Quraishi, S. B. Dietary Intake of Heavy Metals from Eight Highly Consumed Species of Cultured Fish and Possible Human Health Risk Implications in Bangladesh. Toxicol Rep 2017, 4, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simachaya, W.; Yolthantham, T. Policy and Implementation on Water Environment in Thailand. Pollution Control Department of Thailand. Bangkok, Thailand.

- Ip, Y. K.; Chew, S. F.; Randall, D. J. Ammonia Toxicity, Tolerance, and Excretion. Fish physiology 2001, 20, 109–148. [Google Scholar]

- Buet, A.; Banas, D.; Vollaire, Y.; Coulet, E.; Roche, H. Biomarker Responses in European Eel (Anguilla Anguilla) Exposed to Persistent Organic Pollutants. A Field Study in the Vaccarès Lagoon (Camargue, France). Chemosphere 2006, 65, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rocha, A. M.; De Freitas, D. P. S.; Burns, M.; Vieira, J. P.; De La Torre, F. R.; Monserrat, J. M. Seasonal and Organ Variations in Antioxidant Capacity, Detoxifying Competence and Oxidative Damage in Freshwater and Estuarine Fishes from Southern Brazil. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2009, 150, 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska, B.; Witeska, M. Metal Toxicity to Fish. Monografie. University of Podlasie (Poland).

- Promsid, P. Chromosomal Aberration Assessment of Fish in Reservoir Affected by Leachate in Municipal Landfill. Master of Science Thesis, Department of Environmental Science, Faculty of Science, Khon Kaen University 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Noudeng, V.; Pheakdey, D. V.; Xuan, T. D. Toxic Heavy Metals in a Landfill Environment (Vientiane, Laos): Fish Species and Associated Health Risk Assessment. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2024, 108, 104460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriuttha, M.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Intamat, S.; Phoonaploy, U.; Thanomsangad, P.; Neeratanaphan, L. Cadmium, Chromium, and Lead Accumulation in Aquatic Plants and Animals near a Municipal Landfill. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2017, 23, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, T.; Kargın, D.; Çoğun, H. Y.; Temiz, Ö.; Varkal, H. S.; Kargın, F. Accumulation and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Tissues of the Shrimp and Fish Species from the Yumurtalik Coast of Iskenderun Gulf, Turkey. Heliyon 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, M.; Dalia, M.; Ghada, S. Impact of Some Heavy Metals on Muscles, Hematological and Biochemical Parameters of the Nile Tilapia in Ismailia Canal, Egypt. Egypt J Aquat Biol Fish 2023, 27, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waichman, A. V; de Souza Nunes, G. S.; de Oliveira, R.; López-Heras, I.; Rico, A. Human Health Risks Associated to Trace Elements and Metals in Commercial Fish from the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2025, 148, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuphisut, O.; Sangrajang, S. Electronic Waste and Hazardous Substances. Thai Journal of Toxicology 2010, 25, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Thitiyan, T.; Pongdontri, P.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Neeratanaphan, L. Bioaccumulation and Oxidative Stress in Barbonymus Gonionotus Affected by Heavy Metals and Metalloid in Municipal Landfill Reservoir. International Journal of Environmental Studies 2022, 79, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseem, H.; Banerjee, T. K. Metal Bioaccumulation in Fish Labeo Rohita Exposed to Effluent Generated during Metals Extraction from Polymetallic Sea Nodules. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 2015, 12, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sadaawy, M. M.; El-Said, G. F.; Sallam, N. A. Bioavailability of Heavy Metals in Fresh Water Tilapia Nilotica (Oreachromis Niloticus Linnaeus, 1758): Potential Risk to Fishermen and Consumers. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B 2013, 48, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Li, X. Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in Fish Species from the Meiliang Bay, Taihu Lake, China. Toxicol Rep 2018, 5, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezemonye, L. I.; Adebayo, P. O.; Enuneku, A. A.; Tongo, I.; Ogbomida, E. Potential Health Risk Consequences of Heavy Metal Concentrations in Surface Water, Shrimp (Macrobrachium Macrobrachion) and Fish (Brycinus Longipinnis) from Benin River, Nigeria. Toxicol Rep 2019, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, P. K.; Malik, D. S.; Yadav, K. K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Kamyab, H. Bioaccumulation and Potential Sources of Heavy Metal Contamination in Fish Species in River Ganga Basin: Possible Human Health Risks Evaluation. Toxicol Rep 2019, 6, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoonaploy, U.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Neeratanaphan, L. Effects of Electronic Waste on Cytogenetic and Physiological Changes in Snakehead Fish (Channa Striata). Environ Monit Assess 2019, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P. B.; Yedjou, C. G.; Patlolla, A. K.; Sutton, D. J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. Molecular, clinical and environmental toxicology: volume 3: environmental toxicology.

- Pavesi, T.; Moreira, J. C. Mechanisms and Individuality in Chromium Toxicity in Humans. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2020, 40, 1183–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of Lead: A Review with Recent Updates. Interdiscip Toxicol 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, H.; Haris, P. I.; Brima, E. I. Estimated Dietary Intakes of Toxic Elements from Four Staple Foods in Najran City, Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laohasiriwong, W.; Srathonghon, W.; Pitaksanurat, S.; Nathapindhu, G.; Setheetham, D.; Intamat, S.; Phajan, T.; Neeratanaphan, L. Factors Associated with Blood Zinc, Chromium, and Lead Concentrations in Residents of the Nam Pong River in Thailand. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2016, 22, 1583–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sratlionghon, W.; Laohasiriwong, W.; Pitaksanurat, S.; Nathapindhu, G.; Setheetham, D.; Intamat, S.; Phajan, T.; Neeratanaphane, L. Factors Influencing Blood Cadmium and Mercury Concentrations in Residents of Agro-Industries along Nam Phong River, Thailand. EnvironmentAsia 2016, 9. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. 2015. Risk Based Screening Table. Composite Table: Summary Tab 0615. Available at http://www2.epa.gov/risk/risk based screening table generic tables.

- Debnath, B.; Singh, W. S.; Manna, K. Sources and Toxicological Effects of Lead on Human Health. Indian Journal of Medical Specialities 2019, 10, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.-S.; Song, K.-H.; Chung, J.-Y. Health Effects of Chronic Arsenic Exposure. Journal of preventive medicine and public health 2014, 47, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R. D.; Mitchell, M.; Sgouros, J.; Lindahl, T. Human DNA Repair Genes. Science (1979) 2001, 291, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monserrat, J. M.; Martínez, P. E.; Geracitano, L. A.; Amado, L. L.; Martins, C. M. G.; Pinho, G. L. L.; Chaves, I. S.; Ferreira-Cravo, M.; Ventura-Lima, J.; Bianchini, A. Pollution Biomarkers in Estuarine Animals: Critical Review and New Perspectives. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology.

- Vilela, C. L. S.; Bassin, J. P.; Peixoto, R. S. Water Contamination by Endocrine Disruptors: Impacts, Microbiological Aspects and Trends for Environmental Protection. Environmental pollution 2018, 235, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, D. K.; Yashvardhini, N.; Bhattacharya, S.; Sayrav, K.; Kumar, A.; Khan, P. Study of Arsenic Genotoxicity in a Freshwater Fish (Channa Punctatus) Using RAPD as Molecular Marker. 2021.

- Castaño, A.; Becerril, C. In Vitro Assessment of DNA Damage after Short-and Long-Term Exposure to Benzo (a) Pyrene Using RAPD and the RTG-2 Fish Cell Line. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis.

- Waalkes, M. P. Cadmium Carcinogenesis. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2003, 533 (1–2), 107–120.

- Wise, S. S.; Holmes, A. L.; Wise John Pierce, Sr. Hexavalent Chromium-Induced DNA Damage and Repair Mechanisms. Rev Environ Health 2008, 23, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velma, V.; Tchounwou, P. B. Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage Induced by Chromium in Liver and Kidney of Goldfish, Carassius Auratus. Biomark Insights 2013, 8, BMI–S11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, K. D.; Annamalai, S. K.; Kuruva, J. K. In-Vivo Evaluation of Hexavalent Chromium Induced DNA Damage by Alkaline Comet Assay and Oxidative Stress in Catla Catla. Am J Environ Sci 2013, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbergeld, E. K. Facilitative Mechanisms of Lead as a Carcinogen. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis.

- Bolognesi, C.; Hayashi, M. Micronucleus Assay in Aquatic Animals. Mutagenesis 2011, 26, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, A.; Widodo, M. A.; Kristianto, Y. Albumin and Zinc Content of Snakehead Fish (Channa Striata) Extract and Its Role in Health. IEESE International Journal of Science and Technology 2012, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Luoma, S. N.; Rainbow, P. S. Sources and Cycles of Trace Metals. Metal contamination in aquatic environments: science and lateral management. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, 66.

- Gaweł, S.; Wardas, M.; Niedworok, E.; Wardas, P. Malondialdehyde (MDA) as a Lipid Peroxidation Marker. Wiad Lek.

- Doherty, V. F.; Ogunkuade, O. O.; Kanife, U. C. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Heavy Metal Levels as Indicators of Environmental Pollution in Some Selected Fishes in Lagos, Nigeria. Am Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci 2010, 7, 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Bacanskas, L. R.; Whitaker, J.; Di Giulio, R. T. Oxidative Stress in Two Populations of Killifish (Fundulus Heteroclitus) with Differing Contaminant Exposure Histories. Mar Environ Res.

- Bayir, A.; Sirkecioglu, A. N.; Haliloglu, H. I.; Aksakal, E.; Gunes, M.; Aras, N. M. Influence of Season on Antioxidant Defense Systems of Silurus Glanis Linnaeus (Siluridae) and Barbus Capito Capito Güldenstädt (Cyprinidae). Fresen Environ Bull 2011, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Suhartono, E.; Triawanti; Yunanto, A. ; Firdaus, R. T.; Iskandar. Chronic Cadmium Hepatooxidative in Rats: Treatment with Haruan Fish (Channa Striata) Extract. APCBEE Procedia 2013, 5, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, Y.; Ratn, A.; Prasad, R.; Kumar, M.; Trivedi, S. P. An in Vivo Analysis of Cr6+ Induced Biochemical, Genotoxicological and Transcriptional Profiling of Genes Related to Oxidative Stress, DNA Damage and Apoptosis in Liver of Fish, Channa Punctatus (Bloch, 1793). Aquatic Toxicology 2018, 200, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighodaro, O. M.; Akinloye, O. A. First Line Defence Antioxidants-Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Catalase (CAT) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX): Their Fundamental Role in the Entire Antioxidant Defence Grid. Alexandria journal of medicine 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm Filho, D. Fish Antioxidant Defenses--a Comparative Approach. Braz J Med Biol Res 1996, 29, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A. A.; Sales, C. F.; de Souza Faria, F.; Melo, R. M. C.; Bazzoli, N.; Rizzo, E. Effects of Metal Contamination on Liver in Two Fish Species from a Highly Impacted Neotropical River: A Case Study of the Fundão Dam, Brazil. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2020, 190, 110165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Usmani, N.; Firdaus, F.; Zafeer, M. F.; Ahmad, S.; Akhtar, K.; Dawar Husain, S. M.; Ahmad, M. H.; Anis, E.; Mobarak Hossain, M. In Vivo Induction of Antioxidant Response and Oxidative Stress Associated with Genotoxicity and Histopathological Alteration in Two Commercial Fish Species Due to Heavy Metals Exposure in Northern India (Kali) River. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology.

| No. | Nucleotide Sequences | Total bands | Monomorphic band | Polymorphic band |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A4 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAA | 47 | 2 | 6 |

| A11 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAAA | 73 | 1 | 8 |

| A12 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAAC | 49 | 2 | 5 |

| A14 | AGAGAGAGAGAGAGAAT | 68 | 3 | 5 |

| P4 | CACACACACACAAC | 32 | 3 | 1 |

| P5 | CACACACACACAGT | 36 | 1 | 5 |

| P6 | CACACACACACAAG | 38 | 2 | 5 |

| P7 | CACACACACACAGG | 18 | 1 | 1 |

| P10 | GAGAGAGAGAGACC | 47 | 4 | 1 |

| P12 | CACCACCACGC | 52 | 2 | 4 |

| P13 | GAGGAGGAGGC | 43 | 1 | 5 |

| P14 | CTCCTCCTCGC | 50 | 2 | 4 |

| P15 | GTGGTGGTGGC | 68 | 3 | 6 |

| Total | 621 | 27 | 56 |

| Samples | Indicators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | TDS (mg/L) | DO (mg/L) | EC (µs/cm) | pH | ||

| Reference | 31.36±0.72 | 0.47±0.03 | 6.57±0.24 | 317.62±6.08 | 7.65±0.46 | |

| Landfill | 29.06±0.65 | 0.51±0.06 | 4.51±0.38 | 456.72±4.88 | 7.16±0.61 | |

| Standard | N/A | N/A | ≥4.00 | N/A | 5-9 | |

| Concentration (mg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Site | As | Cd | Cr | Pb |

| Reference | 0.0028±0.0008 | 0.03±0.006 | 0.015±0.011 | 0.031±0.007 |

| landfill | 0.0848±0.142 | 0.536±0.139 | 1.23±0.445 | 0.73±0.19 |

| P-value | 0.268 | 0.001* | 0.004* | 0.001* |

| Standard | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Concentration (mg/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study site | As | Cd | Cr | Pb |

| Reference | 0.556±0.236 | 0.0523±0.126 | 12.64±2.35 | 5.32±0.97 |

| landfill | 1.274±0.436 | 1.162±0.428 | 16.68±2.08 | 14.19±3.15 |

| p-value | 0.012* | 0.013* | 0.019* | 0.002* |

| Standard | 3.9 | 1 | 100 | 100 |

| Concentration (mg/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Site | As | Cd | Cr | Pb |

| Reference | 0.0352±0.0069 | 0.0272±0.0024 | 1.17±0.36 | 0.094±0.08 |

| Landfill | 0.0758±0.0173 | 0.096±0.033 | 1.83±0.09 | 0.69±0.63 |

| p-value | 0.001* | 0.009* | 0.014* | 0.103* |

| Standard | 2 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 0.5 |

| Heavy metals | O. niloticus | |

|---|---|---|

| BAF values based on water | As | 0.282±1.83 |

| Cd | 0.179±0.112 | |

| Cr | 1.487±0.663 | |

| Pb | 0.945±1.557 |

| Heavy metals | EDI (μg/kg/day) | HRI | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| O. niloticus | |||

| As | 0.0016297 | 0.00543 | 0.000001086 |

| Cd | 0.002064 | 0.00206 | - |

| Cr | 0.039345 | 0.013333 | - |

| Pb | 0.014835 | 0.0025 | 0.0011 |

| Unacceptable risk levels | - | >1 [20] | >1×10−4 [33] |

| Fish No. | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| 1.2 | 0.8765 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| 1.3 | 0.9103 | 0.9383 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| 1.4 | 0.8734 | 0.9259 | 0.9125 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 1.5 | 0.9600 | 0.9136 | 0.9487 | 0.8875 | 1.0000 | |||||

| 2.1 | 0.6184 | 0.6173 | 0.6000 | 0.6282 | 0.6364 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 2.2 | 0.4737 | 0.4634 | 0.4810 | 0.4684 | 0.4935 | 0.6250 | 1.0000 | |||

| 2.3 | 0.6316 | 0.6098 | 0.6125 | 0.6203 | 0.6076 | 0.6349 | 0.6140 | 1.0000 | ||

| 2.4 | 0.5946 | 0.5750 | 0.5769 | 0.5844 | 0.5921 | 0.6441 | 0.6226 | 0.6333 | 1.0000 | |

| 2.5 | 0.6757 | 0.6500 | 0.6538 | 0.6410 | 0.6933 | 0.7167 | 0.6140 | 0.6000 | 0.6333 | 1.0000 |

| Parameter | Reference | Landfill | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDA (mmol/MDA/g liver) | 31.11±0.75 | 56.8±8.93 | 0.003* |

| H2O2 (mmol/g liver) | 13.54±0.906 | 20.65±3.12 | 0.001* |

| SOD (%) | 33.45±2.95 | 20.41±6.51 | 0.004* |

| CAT (Units/mg protein) | 23.51±2.96 | 14.85±3.48 | 0.003* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).