Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The transition to renewable energy is a crucial step toward sustainability and integrating photovoltaic (PV) systems with battery storage and electric vehicle (EV) charging plays a key role in optimizing energy consumption and reducing reliance on fossil fuels. This study examines the design, performance, and impact of a grid-connected PV system in Constanta, Romania, assessing its ability to enhance energy efficiency, improve self-sufficiency, and contribute to environmental sustainability. By leveraging battery storage, surplus solar power is retained for later use, reducing dependency on the grid and ensuring a stable electricity supply. The study further investigates the economic and environmental benefits of renewable energy integration, including reductions in carbon emissions and operational costs. The analysis was conducted using PV*SOL for system simulation and performance evaluation, while Global Solar Atlas provided solar irradiance data for accurate energy yield assessment. The results demonstrate that integrating PV systems with battery storage and EV charging significantly enhances energy independence, with 92.2% of total consumption covered by solar energy and a reduction of 6239 kg in CO₂ emissions annually. This research provides a comprehensive model for renewable energy adoption, supporting the transition toward a cleaner and more sustainable energy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Configuration and Installation

2.2. Energy Consumption and Monitoring

2.3. Simulation and Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

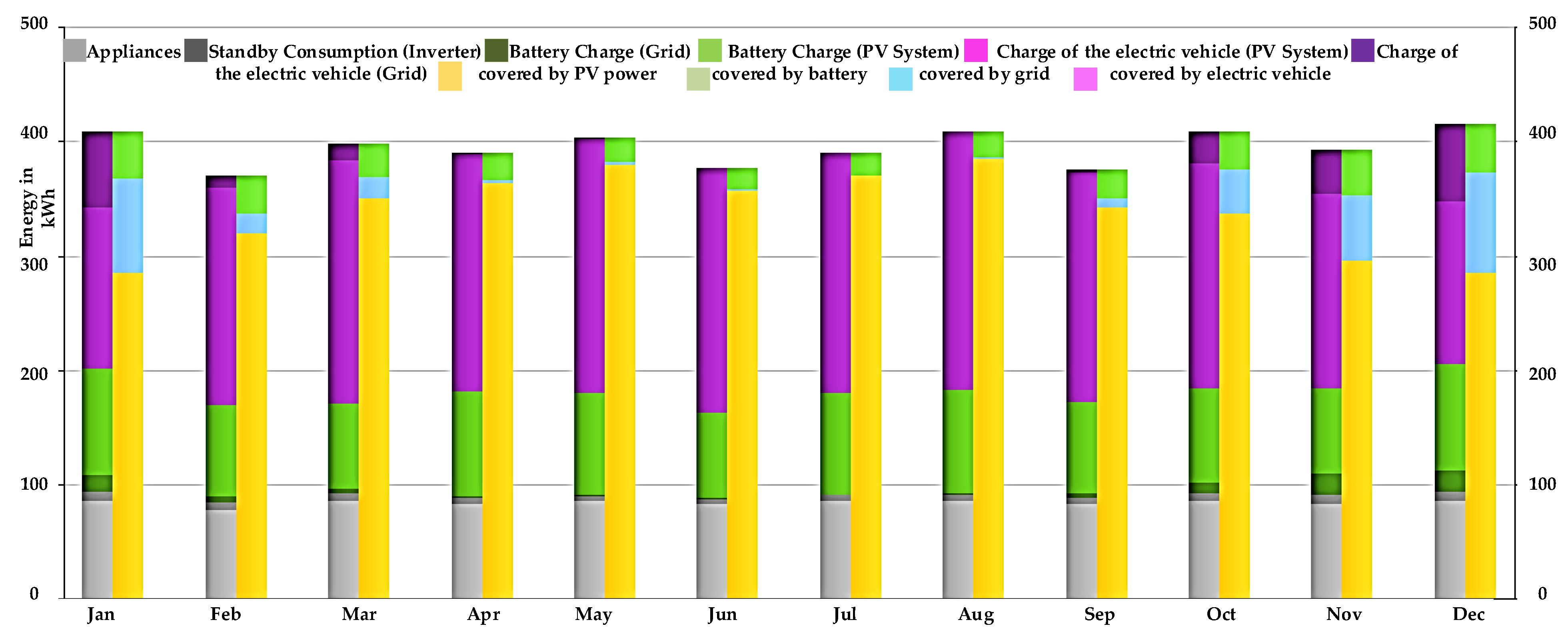

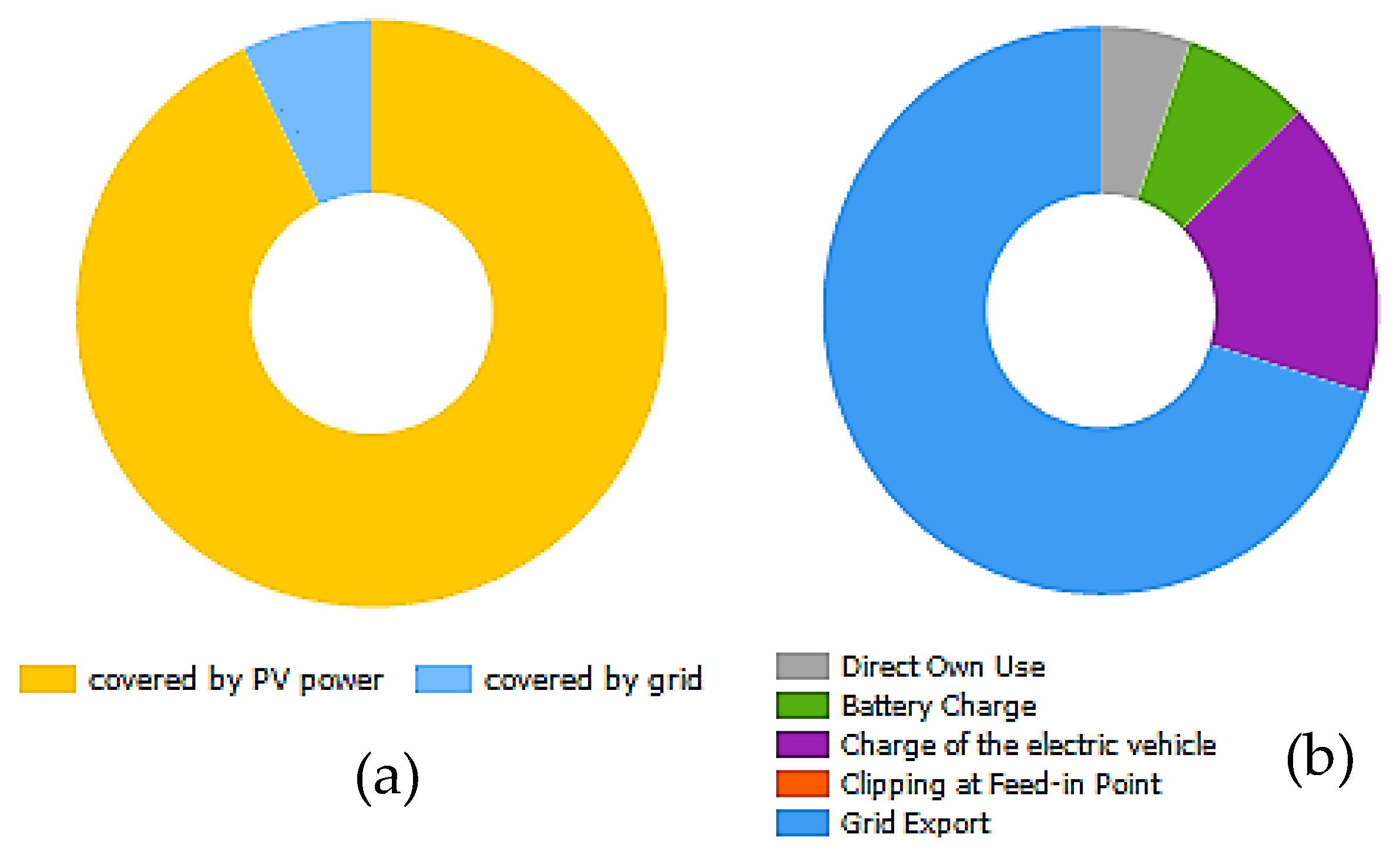

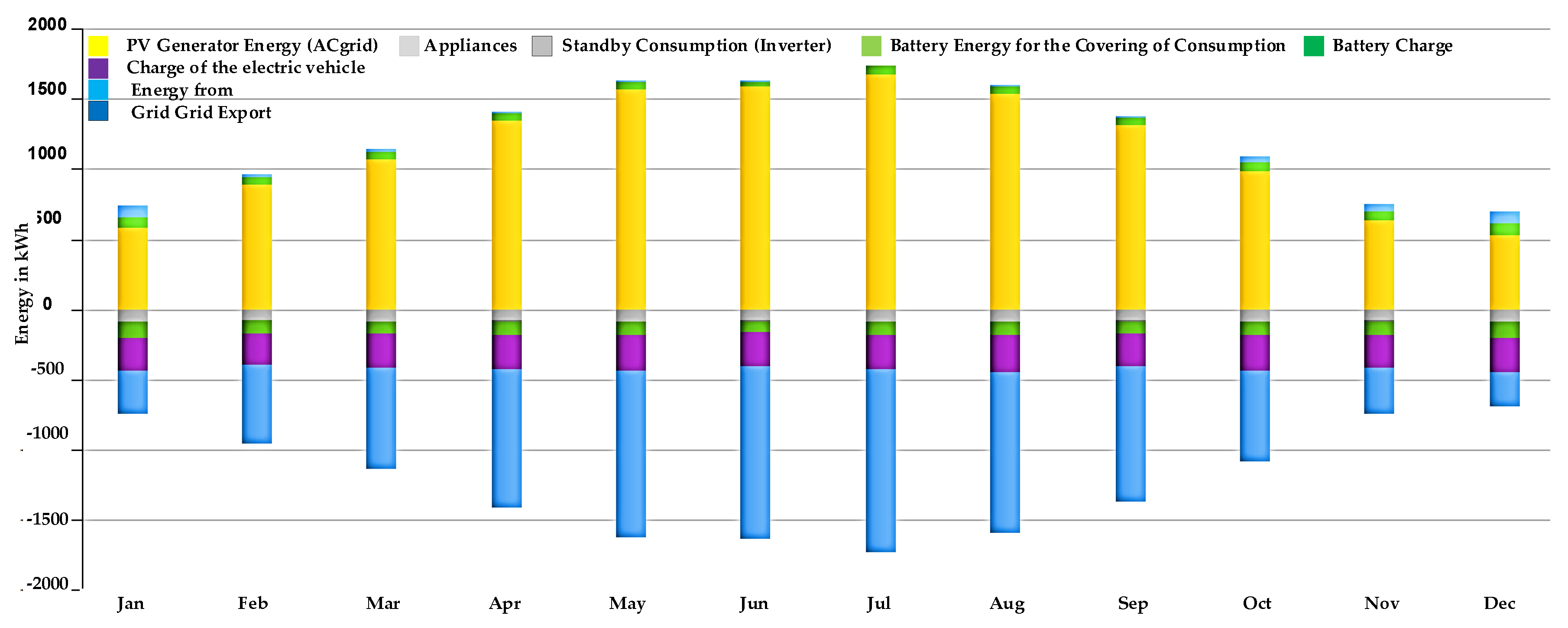

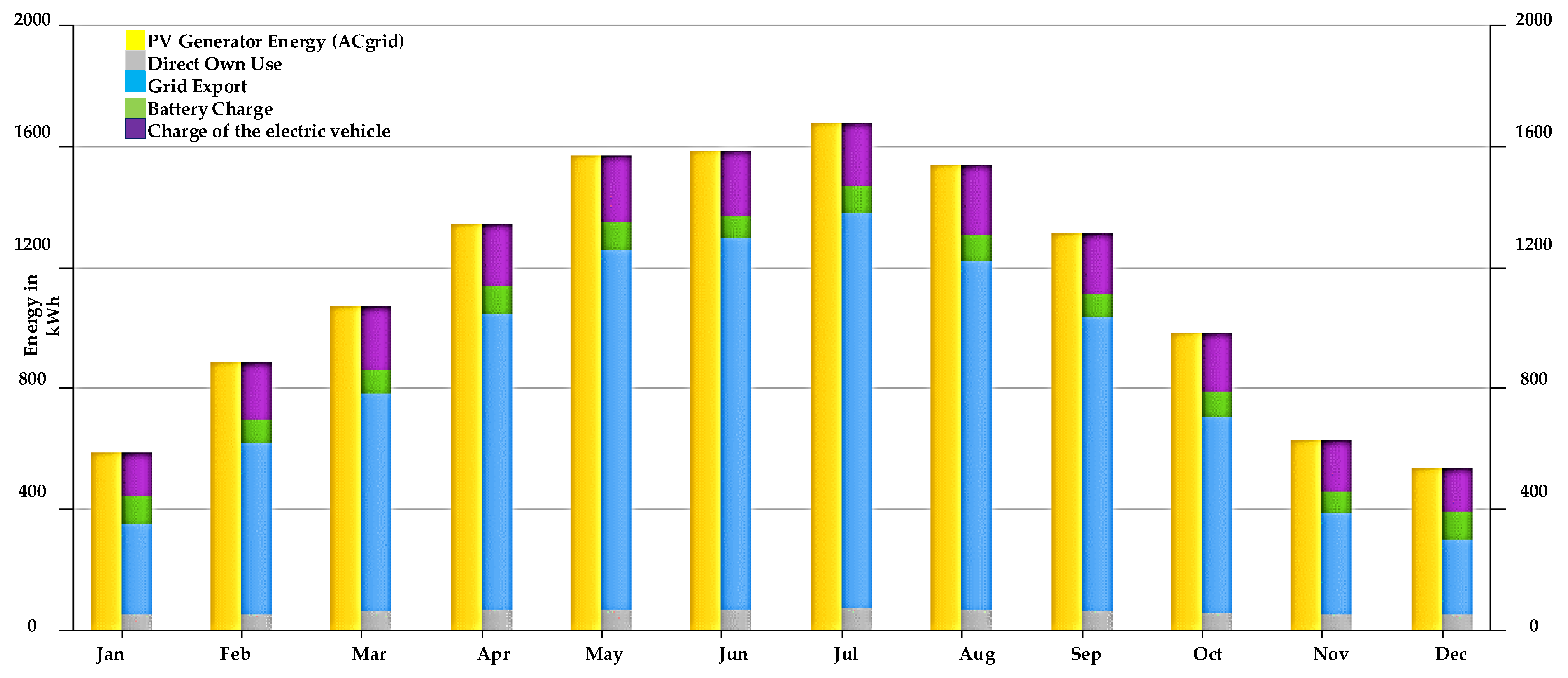

- Gray sections represent direct own use, which remains relatively stable across all months.

- Blue sections indicate grid export, showing that during high-production months (May–August), a significant portion of solar energy is sent to the grid.

- Green sections represent battery charge, which increases during months of higher solar production, allowing for energy storage [49].

- Purple sections show energy used for charging the electric vehicle, demonstrating that a portion of PV energy is directly allocated to EV charging.

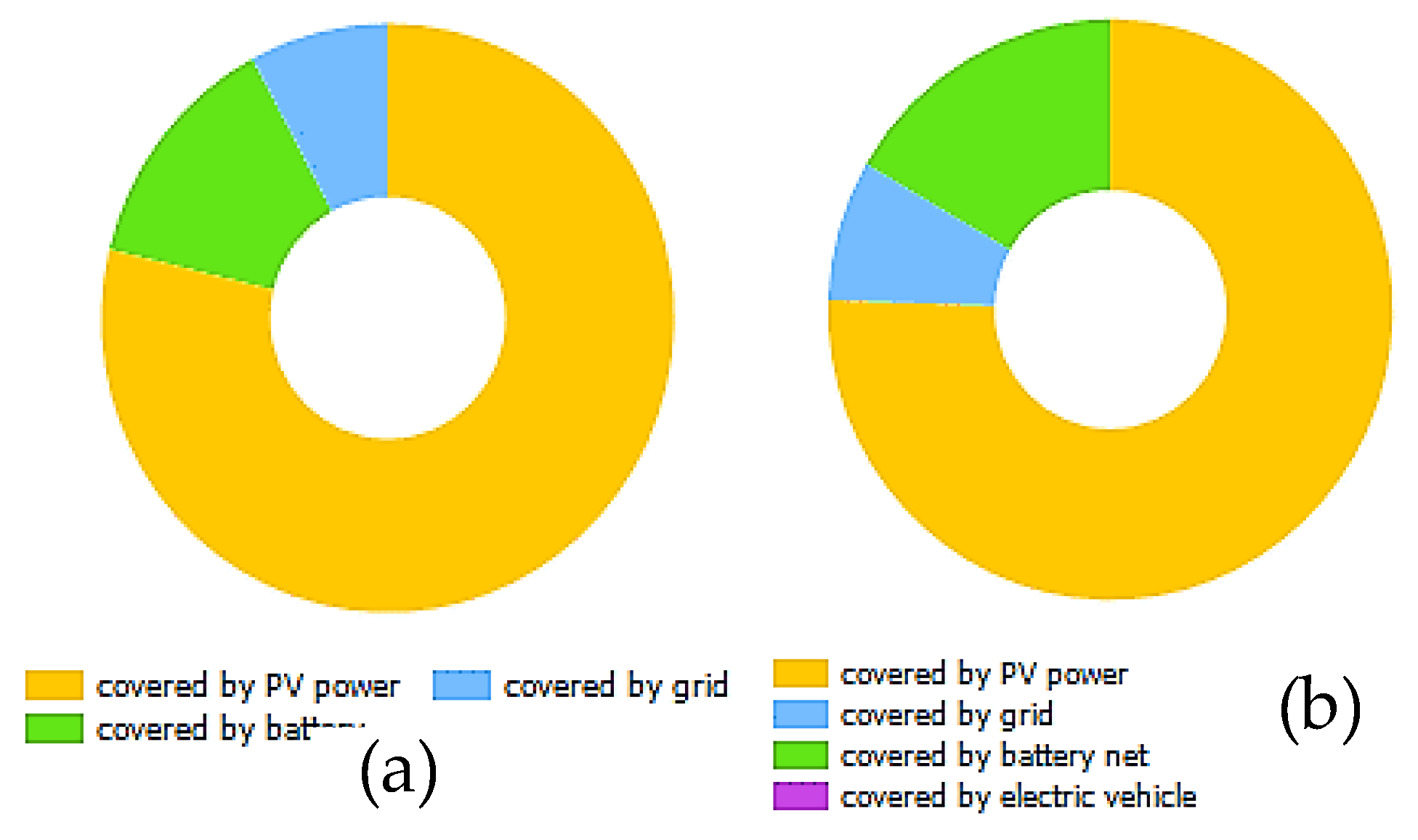

- Yellow sections representing energy covered by PV power, which fluctuates based on solar generation, with higher coverage in summer and lower in winter.

- Green sections indicating energy covered by the battery, showing that stored solar energy is used to supplement consumption.

- Small blue sections representing energy covered by the grid, which appear mainly in winter months when solar and battery power are insufficient.

- Purple sections indicating energy covered by the electric vehicle, showing the portion of PV or battery power used for EV charging. [50]

- Yellow sections represent energy covered by PV power, which remains a significant contributor throughout the year, with higher values in summer months.

- Green sections indicate battery energy use, including battery charge from PV (light green) and battery charge from the grid (dark green), showing how stored energy supports consumption.

- Purple sections represent energy used for charging the electric vehicle, with contributions from both PV and the grid.

- Blue sections show grid energy use, which appears more prominently in winter months (November–February) when solar generation is lower, indicating an increased reliance on the grid.

- During summer months (May–August), a larger portion of energy is covered by PV power and battery storage, reducing dependence on the grid.

- In winter months (November–February), grid energy contribution increases, as solar production is lower, requiring additional support from external sources.

- Battery storage plays a key role in balancing energy use, ensuring that stored solar energy can be utilized efficiently across different months.

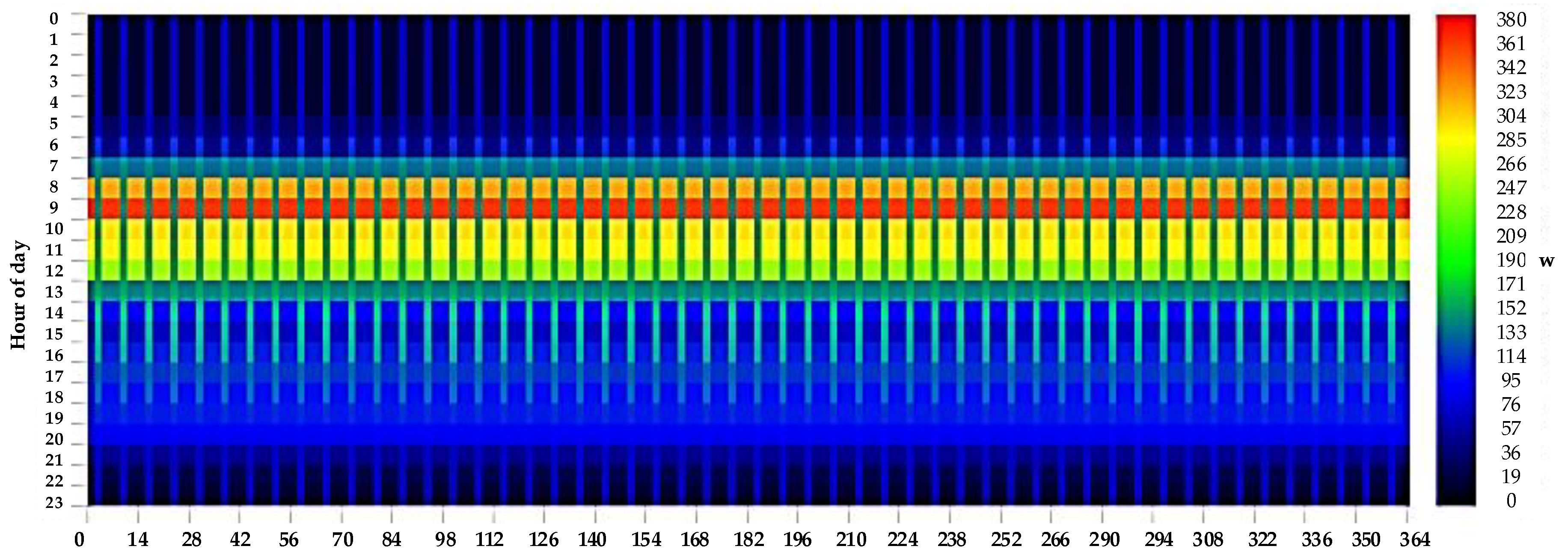

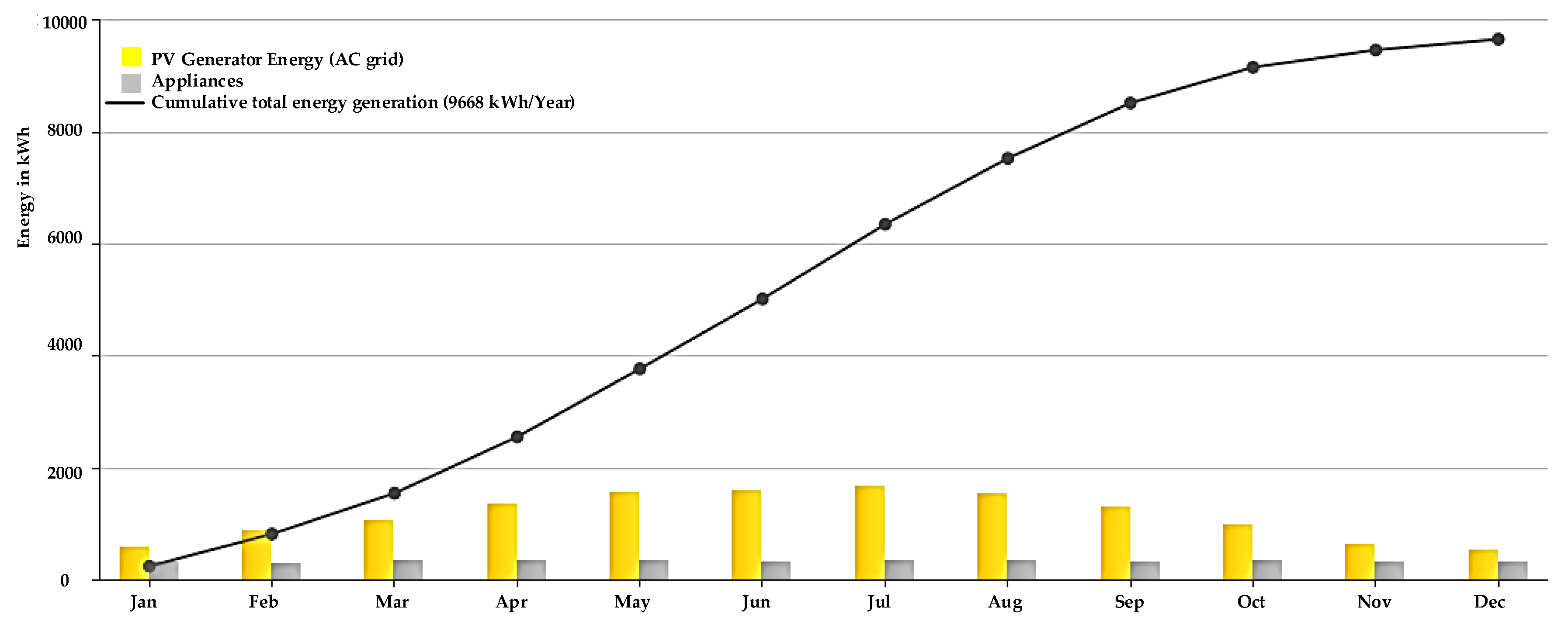

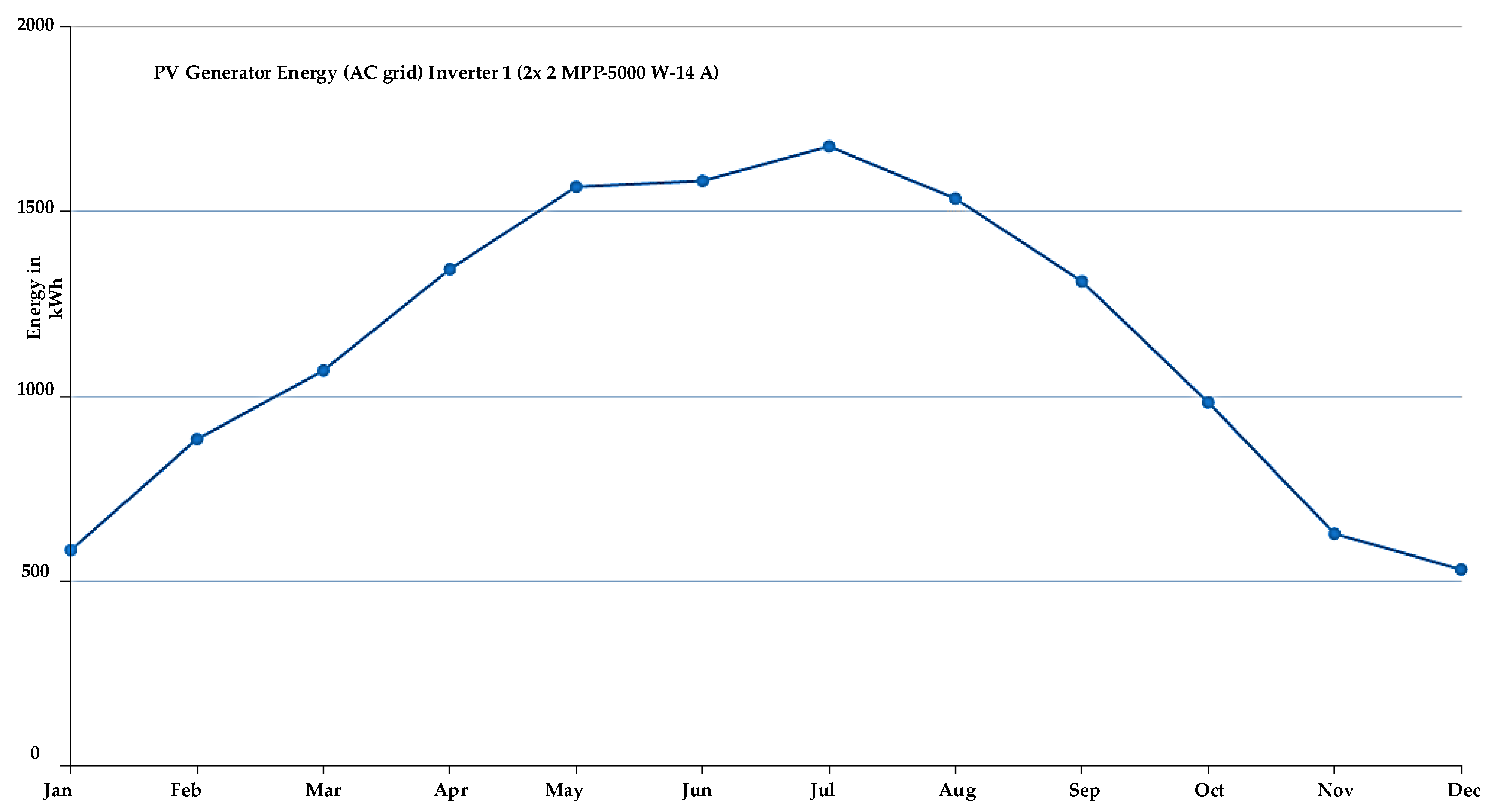

- The energy output is lowest in January and December, with values below 600 kWh.

- As sunlight increases, generation rises steadily from February to May, reaching over 1500 kWh.

- The peak production occurs in June and July, with the highest monthly output exceeding 1700 kWh.

- After July, generation gradually declines, following a downward trend from August to November due to reduced sunlight hours.

- The curve mirrors seasonal solar availability, with higher production in spring and summer and lower production in autumn and winter.

- The inverter efficiently processes PV energy, ensuring stable performance across the year.

- This seasonal variation is typical for solar power systems, as sunlight duration and intensity fluctuate annually.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- H. Feng, J. Liu, Y. Zhang, and D. Liu, “Solar energy storage in an all-vanadium photoelectrochemical cell: structural effect of titania nanocatalyst in photoanode,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 12, p. 4508, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Gmal Osman M., Strejoiu CV., Panait C., Lazaroiu G., Lazaroiu AC. Renewable energy integration, climate analysis, and efficiency optimization for greener transportation - case study in Dobrogea. International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference-SGEM; 2023; (pp. 675-687).

- POWER | Data Access Viewer.” Accessed: Sep. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/.

- M. Firoozzadeh, A. H. Shiravi, and M. Shafiee, “Experimental and Analytical Study on Enhancing Efficiency of the Photovoltaic Panels Using Polyethylene-Glycol 600 (PEG 600) as a Phase Change Material,” Iranian (Iranica) Journal of Energy & Environment, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 23–32, 2019. [CrossRef]

- O. M. Babatunde, J. L. Munda, and Y. Hamam, “Off-grid hybrid photovoltaic–micro wind turbine renewable energy system with hydrogen and battery storage: Effects of sun tracking technologies,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 255, p. 115335, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Strejoiu, C.V., Osman, M.G. and Cernat, A.C., 2023. Towards sustainable transportation: modeling and simulation of pv panel implementation on national highways for charging electric vehicles which leads to mitigate carbon emission. UPB Scientific Bulletin, Series C: Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, 85(4), pp.321-334.

- Ma, Y., Chen, L., & Zhao, H., 2021. Optimization of water heating systems using solar energy and air-source heat pumps. Journal of Renewable Energy Studies, 48(2), pp.145-157.

- Osman, M.G., Strejoiu, C.V., Panait, C., Lazaroiu, G. and Lazaroiu, A.C., 2023. Renewable energy integration, climate analysis, and efficiency optimization for greener transportation-case study in Dobrogea. International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM, 23(6.2), pp.675-687.

- Green, M.A., 2000. Photovoltaics: technology overview. Energy policy, 28(14), pp.989-998.

- Firoozzadeh, M., Shiravi, A.H. and Shafiee, M., 2019. Experimental and Analytical Study on Enhancing Efficiency of the Photovoltaic Panels Using Polyethylene-Glycol 600 (PEG 600) as a Phase Change Material. Iranica Journal of Energy & Environment, 10(1), pp.23-32.

- Babatunde, O.M., Munda, J.L. and Hamam, Y., 2022. Off-grid hybrid photovoltaic–micro wind turbine renewable energy system with hydrogen and battery storage: Effects of sun tracking technologies. Energy Conversion and Management, 255, p.115335.

- Gangopadhyay, U., Jana, S. and Das, S., 2013. State of art of solar photovoltaic technology. In Conference papers in science (Vol. 2013, No. 1, p. 764132). Hindawi Publishing Corporation.

- Kumar, S. and Tiwary, K.P., 2022. Cadmium selenide thin film deposition and characterization for photovoltaic applications. In Nanomaterials for Innovative Energy Systems and Devices (pp. 333-367). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Osman, M.G., Ciupagenau, D.A., Lazaroiu, G. and Pisa, I., 2022, September. Increasing Renewable Energy Participation in Sudan. In 2022 11th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Application (ICRERA) (pp. 169-173). IEEE.

- Zakaria, Z.A., Chen, B.C. and Hassan, M.O., 2008, October. Modeling of photovoltaic power plants. In 2008 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (pp. 3835-3839). IEEE.

- Zhu, C.X., Sun, T., Liu, Y., Zhou, Y. and Chen, Y., 2021. Capacity matching and operation optimization of solar energy and air source heat pump combined heating system. Acta Solar Energy Sinica, 42(08), pp.215-222.

- Dubey, S., Sarvaiya, J.N. and Seshadri, B., 2013. Temperature dependent photovoltaic (PV) efficiency and its effect on PV production in the world–a review. Energy procedia, 33, pp.311-321. [CrossRef]

- Oulis Rousis, A., Tzelepis, D., Konstantelos, I., Booth, C. and Strbac, G., 2018. Design of a hybrid AC/DC microgrid using Homer Pro: Case study on an islanded residential application. Inventions, 3(3), p.55. [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, A.J. and Pearce, J.M., 2012. Open-source development of solar photovoltaic technology. Energy for Sustainable Development, 16(3), pp.379-388. [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.G., Ciupageanu, D. and Stan, A., 2022. Analysis of Solar Radiation in Sudan and Optimal Location of Photovoltaic Panels. UPB Sci. Bull. Series C, 84(4).

- Abarro, J.M.E., Gavan, J.N.L., Loresca, D.E.D., Ortega, M.A.A., Esparcia Jr, E.A. and Paraggua, J.A.D., 2023. A Tale of Nickel-Iron Batteries: Its Resurgence in the Age of Modern Batteries. Batteries, 9(7), p.383.

- Faraji, F., Majazi, A. and Al-Haddad, K., 2017. A comprehensive review of flywheel energy storage system technology. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 67, pp.477-490. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, T., Adams, M. and Walker, T.R., 2021. Role of sustainability in global seaports. Ocean & Coastal Management, 202, p.105435. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Min, H., Sun, W. and Yu, Y., 2021. Research on optimal charging of power lithium-ion batteries in wide temperature range based on variable weighting factors. Energies, 14(6), p.1776. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Zhang, X., Cheng, Q., Guo, B. and Yang, J., 2019. Classification and review of the charging strategies for commercial lithium-ion batteries. Ieee Access, 7, pp.43511-43524.

- Vade, A., Sharma, P., & Kiran, D., 2017. Carbon emissions in wool wet processing: Renewable energy solutions. Journal of Environmental Impact Studies, 29(2), pp.567-574.

- A. K. Zahra Vahidinasab, Alireza Javadi, “Performance and Reliability of Photovoltaic Modules: A Review of Testing Methods. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications,” vol. 26(5), pp. 393-412.

- Z. A. Zakaria, B.-C. Chen, and M. O. Hassan, “Modeling of photovoltaic power plants,” in 2008 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, IEEE, 2008, pp. 3835–3839.

- U. Gangopadhyay, S. Jana, and S. Das, “State of art of solar photovoltaic technology,” in Conference papers in science, Hindawi, 2013.

- Dorel S, Gmal Osman M, Strejoiu CV, Lazaroiu G. Exploring Optimal Charging Strategies for Off-Grid Solar Photovoltaic Systems: A Comparative Study on Battery Storage Techniques. Batteries. 2023 Sep 18;9(9):470.

- S. Kumar and K. P. Tiwary, “Cadmium Selenide Thin Film Deposition and Characterization for Photovoltaic Applications,” in Nanomaterials for Innovative Energy Systems and Devices, Springer, 2022, pp. 333–367.

- S. Dubey, J. N. Sarvaiya, and B. Seshadri, “Temperature dependent photovoltaic (PV) efficiency and its effect on PV production in the world–a review,” Energy Procedia, vol. 33, pp. 311–321, 2013.

- A. Oulis Rousis, D. Tzelepis, I. Konstantelos, C. Booth, and G. Strbac, “Design of a hybrid AC/DC microgrid using Homer Pro: Case study on an islanded residential application,” Inventions, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 55, 2018.

- A. J. Buitenhuis and J. M. Pearce, “Open-source development of solar photovoltaic technology,” Energy for Sustainable Development, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 379–388, 2012.

- Lazaroiu, G., Gmal Osman, M. and Strejoiu, C.V., 2023. Performance Evaluation of Renewable Energy Systems: Photovoltaic, Wind Turbine, Battery Bank, and Hydrogen Storage. Batteries, 9(9), p.468. [CrossRef]

- J. M. E. Abarro, J. N. L. Gavan, D. E. D. Loresca, M. A. A. Ortega, E. A. Esparcia Jr, and J. A. D. R. Paraggua, “A Tale of Nickel-Iron Batteries: Its Resurgence in the Age of Modern Batteries,” Batteries, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 383, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dow, 2001. Product Information: SYLTHERM 800. Available at: https://www.npl.washington.edu/TRIMS/sites/sand.npl.washington.edu.TRIMS/files/manuals_documentation/syltherm-800-technical-data-sheet.pdf (Accessed: Jul /05/2024).

- O.-L. Harpalete, “Estimating Travel Demand with a Multimodal Transport Model Including E-Scooters in Iași, Romania,” Promet-Traffic&Transportation, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 349–363, 2023.

- “PZU: Raport PIP si Volum Tranzactionat.” Accessed: Jul. 16, 2024.[Online]. Available: https://www.opcom.ro/grafice-ip-raportPIP-si-volumTranzactionat/ro.

- K. B. Hueso, M. Armand, and T. Rojo, “High temperature sodium batteries: Status, challenges and future trends,” Energy Environ Sci, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 734–749, 2013,.

- S. M. Mousavi G, F. Faraji, A. Majazi, and K. Al-Haddad, “A comprehensive review of Flywheel Energy Storage System technology,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 67, pp. 477–490, 2017.

- Lazaroiu, A.C., Gmal Osman, M., Strejoiu, C.V. and Lazaroiu, G., 2023. A comprehensive overview of photovoltaic technologies and their efficiency for climate neutrality. Sustainability, 15(23), p.16297. [CrossRef]

- A. A. Bashir, M. Pourakbari-Kasmaei, J. Contreras, and M. Lehtonen, “A novel energy scheduling framework for reliable and economic operation of islanded and grid-connected microgrids,” Electric Power Systems Research, vol. 171, no. February, pp. 85–96, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Spertino, G. Malgaroli, A. Amato, M. A. E. Qureshi, A. Ciocia, and H. Siddiqi, “An Innovative technique for energy assessment of a highly efficient photovoltaic module,” in Solar, MDPI, 2022, pp. 321–333. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Adeagbo, F. K. Ariyo, K. A. Makinde, S. A. Salimon, O. B. Adewuyi, and O. K. Akinde, “Integration of solar photovoltaic distributed generators in distribution networks based on site’s condition,” in Solar, MDPI, 2022, pp. 52–63. [CrossRef]

- S. Chtita, A. Derouich, A. El Ghzizal, and S. Motahhir, “An improved control strategy for charging solar batteries in off-grid photovoltaic systems,” Solar Energy, vol. 220, pp. 927–941, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Al. Ismail and S. M. Hashim, “An economic evaluation of grid connected photovoltaic system for a residential house in Khartoum,” in 2018 International Conference on Computer, Control, Electrical, and Electronics Engineering (ICCCEEE), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

- E. Vartiainen, G. Masson, C. Breyer, D. Moser, and E. Román Medina, “Impact of weighted average cost of capital, capital expenditure, and other parameters on future utility-scale PV levelised cost of electricity,” Progress in photovoltaics: research and applications, vol. 28, no. 6, pp. 439–453, 2020.

- T. Hossain, M. Adams, and T. R. Walker, “Role of sustainability in global seaports,” Ocean Coast Manag, vol. 202, p. 105435, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang, H. Min, W. Sun, and Y. Yu, “Research on optimal charging of power lithium-ion batteries in wide temperature range based on variable weighting factors,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 6, p. 1776, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, L. Wen, X. Gong, J. Liang, X. Hou, and F. Hou, “Piezoelectric-Based Energy Conversion and Storage Materials,” Batteries, vol. 9, no. 7, p. 371, 2023. [CrossRef]

| Category | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| System Type, Climate and Grid | Type of System | Grid-connected PV system |

| Climate Data | Constanta, ROU | |

| AC Mains | 230 V, 3-phase, cos φ = 1 | |

| Consumption | Total Consumption | 1000.0 kWh |

| Load Peak | 0.4 kW | |

| PV Modules | Module Area | Module Area |

| Module Data | 0.4 kWp - Si monocrystalline | |

| Number of PV Modules | 24 | |

| PV Generator Output | 9.6 kWp | |

| Inclination | 30° | |

| Orientation | 180° | |

| Installation Type | Roof parallel | |

| Inverters | Total Power | 10 kW |

| Inverter | 2 MPP - 5 kW - 14 A | |

| Configuration | MPP 1+2: 1 x 12 | |

| Sizing Factor | 96% | |

| Electric Vehicles | Electric Vehicle Group | Group 1 |

| Electric Vehicle Model | Honda e: Ny1 (AC charging) | |

| Charging Power | 11 kW | |

| Battery Capacity | 68.8 kWh | |

| Range (as per standard) | 512 km | |

| Battery System | Battery System Group | Group 1 |

| Battery System | 2 kW - AC Coupling - 14.4 kWh | |

| Type of Coupling | AC coupling | |

| Nominal Output | 2 kW | |

| Battery Type | 12V 1050 Ah valve regulated | |

| Battery Capacity | 14.4 kWh |

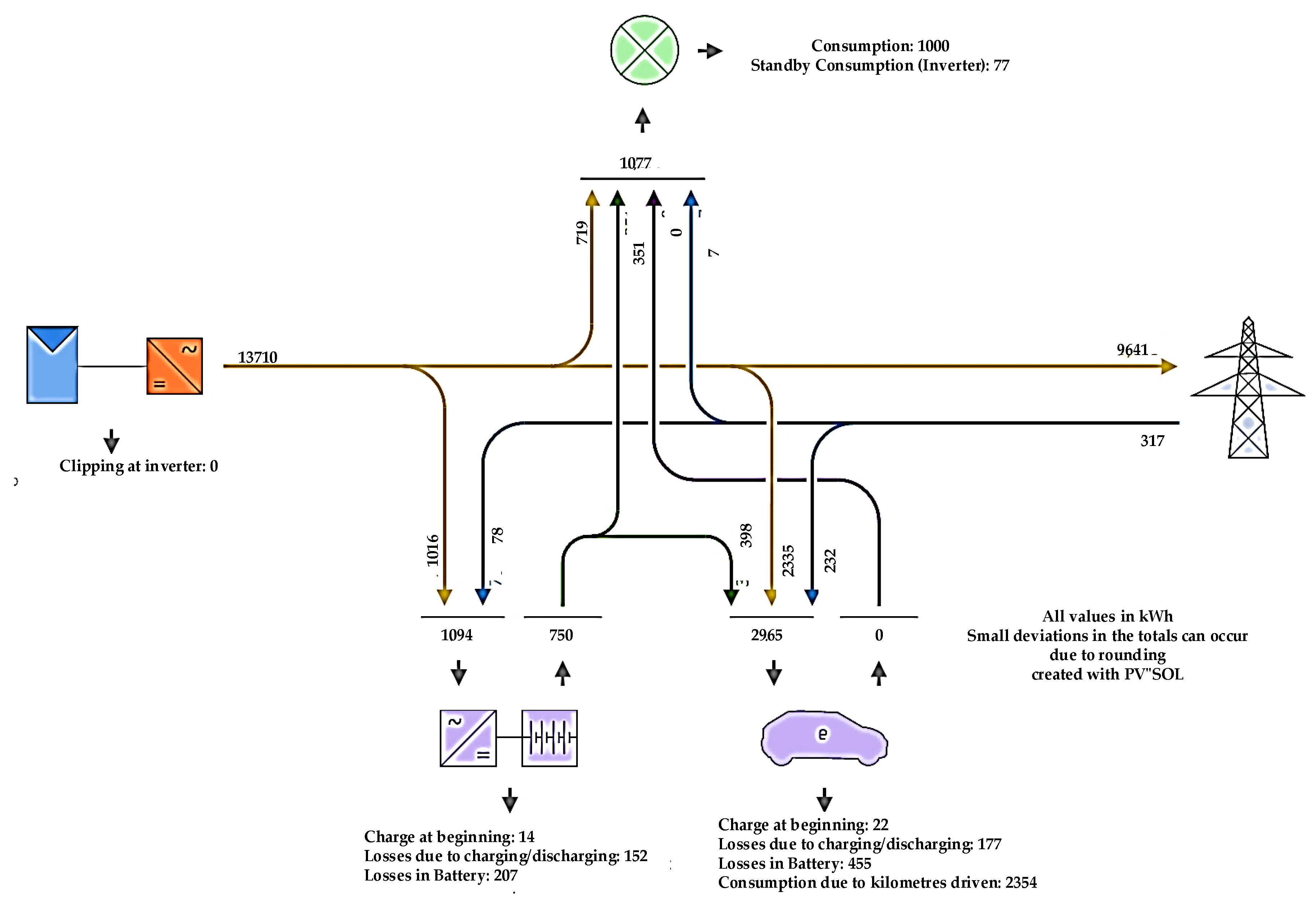

| PV Generator Output | 9.60 kWp | Battery Charge | 1016 kWh/Year |

| Spec. Annual Yield | 1420.18 kWh/kWp | Charge of the electric vehicle | 2335 kWh/Year |

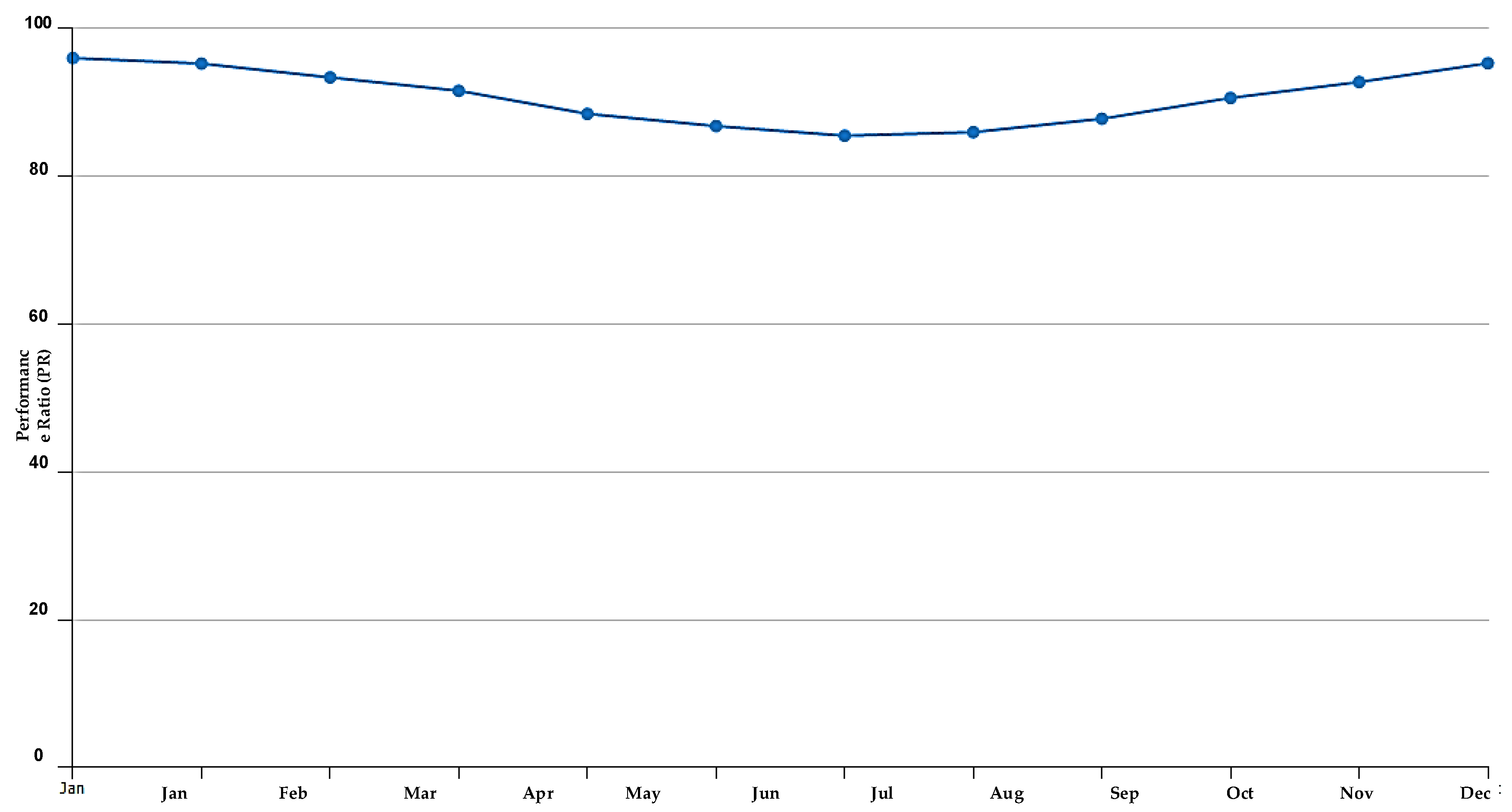

| Performance Ratio (PR) | 88.48 % | Clipping at Feed-in Point | 0 kWh/Year |

| Grid Export | 9641 kWh/Year | ||

| PV Generator Energy (AC grid) | 13710 kWh/Year | Own Power Consumption | 29.3 % |

| Direct Own Use | 719 kWh/Year | CO₂ Emissions avoided | 6239 kg / year |

| Appliances | 1000 kWh/Year | covered by grid | 317 kWh/Year |

| Standby Consumption (Inverter) | 77 kWh/Year | covered by battery net | 672 kWh/Year |

| Charge of the electric vehicle | 2965 kWh/Year | covered by PV power | 3053 kWh/Year |

| Total Consumption | 4042 kWh/Year | Solar Fraction | 92.2 kWh/Year |

| Charge at beginning | 22 kWh | Losses due to charging/discharging | 177 kWh/Year |

| Charge of the electric vehicle (Total) | 2965 kWh/Year | Losses in Battery | 455 kWh/Year |

| covered by PV power | 2335 kWh/Year | Consumption due to km driven | 2354 kWh/Year |

| covered by battery | 398 kWh/Year | Mileage per year | 18250 km/Year |

| covered by grid | 232 kWh/Year | of which is solar | 16820 km/Year |

| Charge at beginning | 14 kWh | Consumption | 351 kWh/Year |

| Battery Charge (Total) | 1094 kWh/Year | Losses due to charging/discharging | 152 kWh/Year |

| covered by PV power | 1016 kWh/Year | Losses in Battery | 207 kWh/Year |

| covered by grid | 78 kWh/Year | Cycle Load | 0.8 % |

| Battery Energy for Covering Consumption | 750 kWh/Year | Service Life | >12 Years |

| Charge of the electric vehicle | 398 kWh/Year |

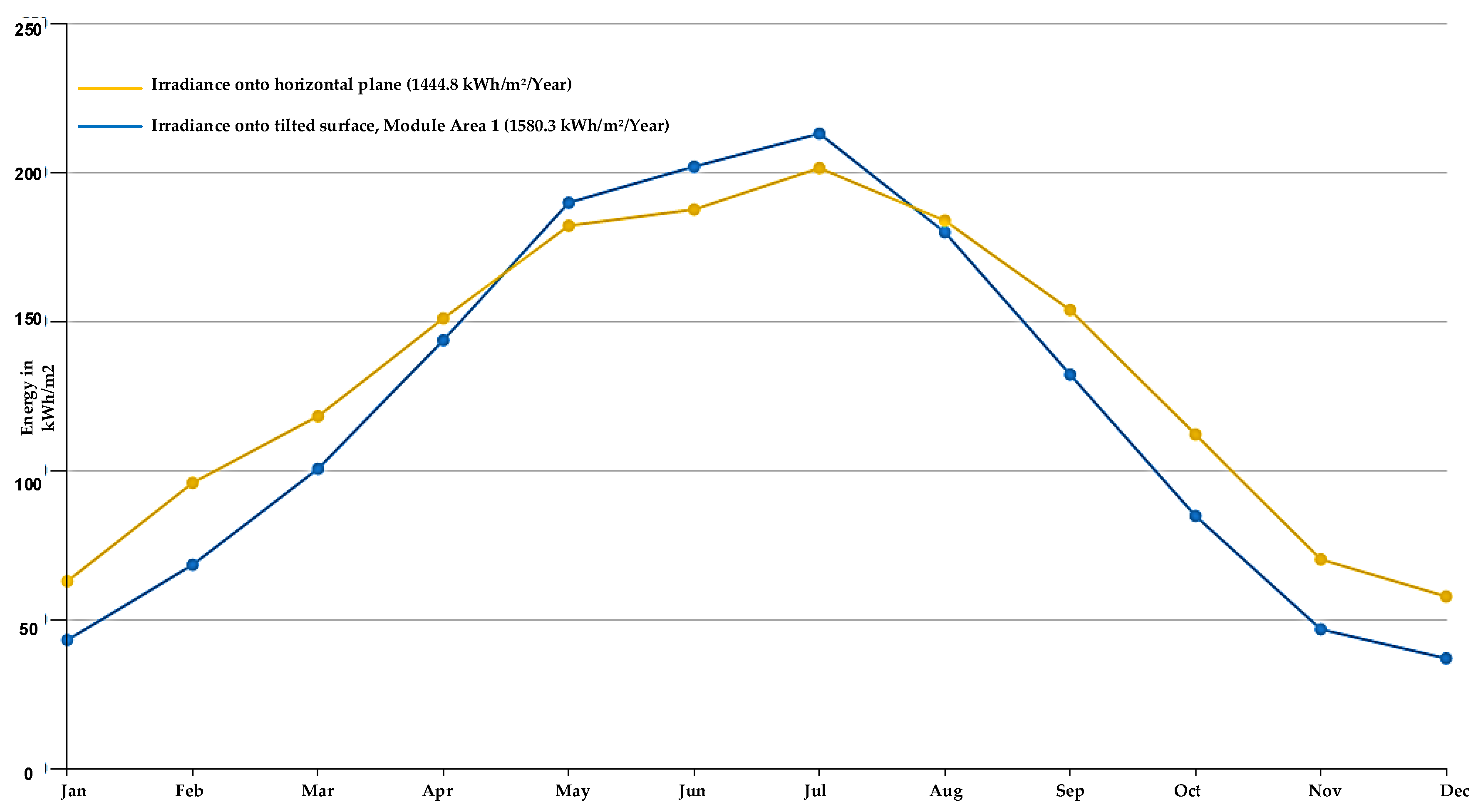

| Module Area | ||

| PV Generator Output | 9.60 | kWp |

| PV Generator Surface | 46.89 | m² |

| Global Radiation at the Module | 1580.30 | kWh/m² |

| Global Radiation on Module without reflection | 1607.93 | kWh/m² |

| Performance Ratio (PR) | 88.98 | % |

| PV Generator Energy (AC grid) | 13710.45 | kWh/Year |

| Spec. Annual Yield | 1428.17 | kWh/kWp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).