Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

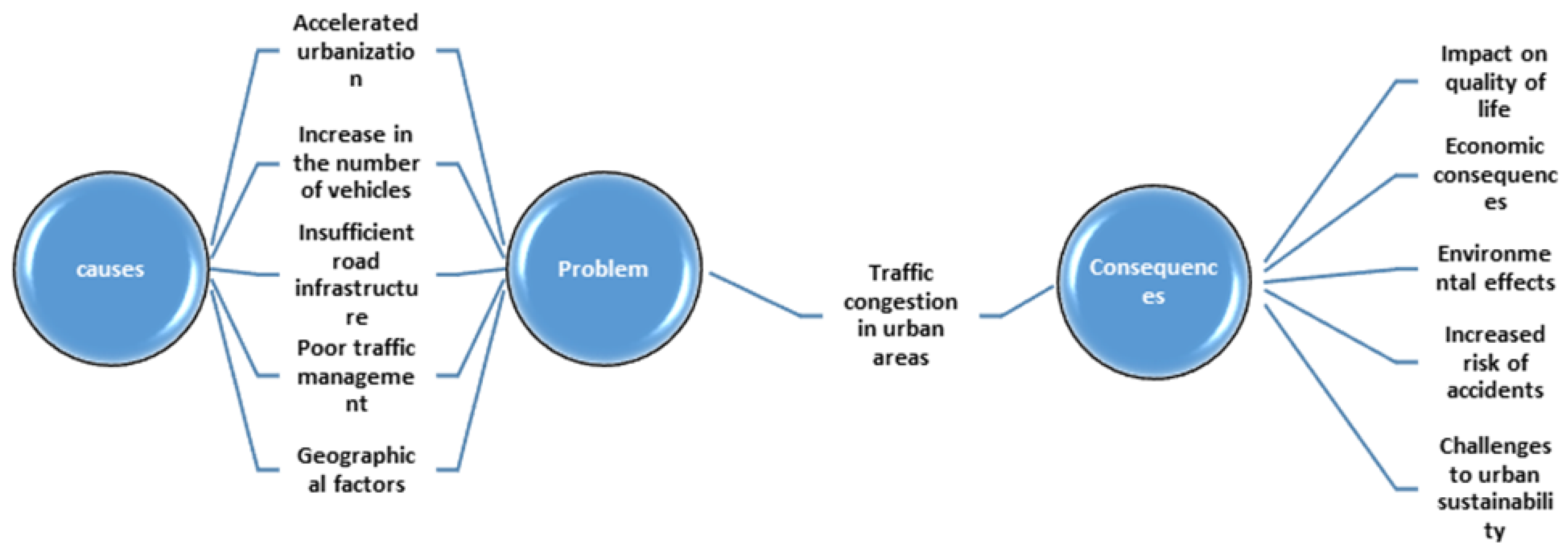

1. Introduction

2. Background

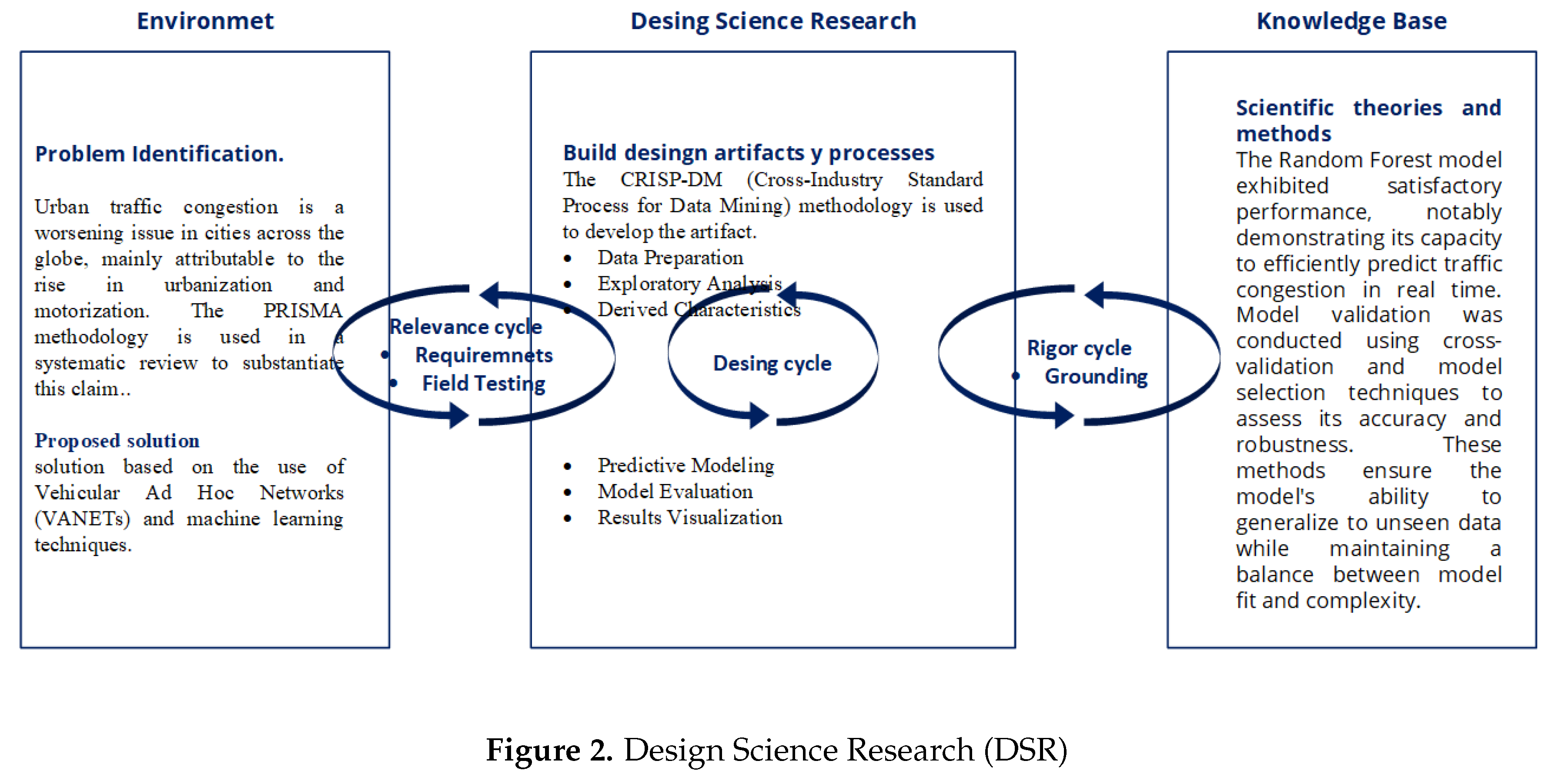

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Relevance Cycle

3.2. Desing Cycle

-

Data preparation: In the first phase, a CSV file containing detailed information about vehicular traffic was used. This file included relevant variables such as vehicle speed, time intervals, and lane. To ensure the quality and usefulness of the dataset, various preprocessing tasks were performed, including:Date Conversion: Dates were converted to datetime format to enable temporal operations and analysis, such as grouping by time intervals. Time Interval Creation: Data was grouped into 10-minute intervals, facilitating temporal analysis and aggregation of values related to traffic dynamics. Average Speed Calculation: The average speed of vehicles was determined for each time interval and lane, providing a key measure for identifying patterns and trends.

-

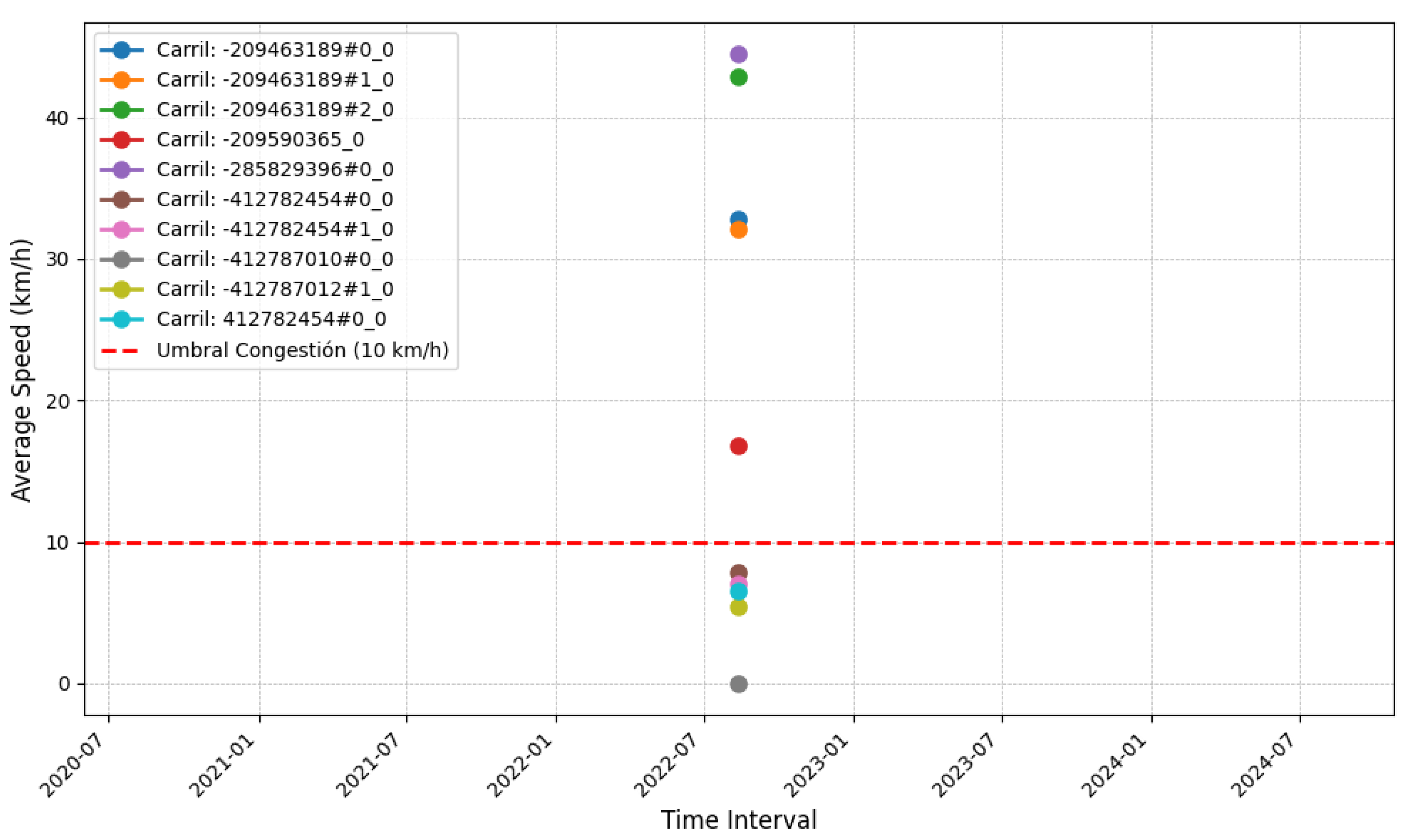

Data exploration: The initial analysis focused on detecting and visualizing relevant patterns in traffic behavior. Among the activities carried out, the following stand out:Congestion Detection: A speed threshold of 10 km/h was defined as a criterion for identifying intervals with vehicular congestion. This definition allowed for data labeling and establishing clear differences between normal and congested conditions [29] . Temporal Visualization: Graphs were generated representing average speeds as a function of time for each lane, using a reference line to highlight moments when the speed fell below the established threshold [30].

-

Derived features: To enrich the dataset and improve the predictive capability of the model, new features were derived:Congestion Labeling: A binary column was added to classify each interval as congested (1) or not congested (0), based on the previously defined threshold. Temporal Variables: Additional features were added, such as time of day and day of the week, providing temporal context and allowing for capturing seasonal patterns in traffic [31].

-

Predictive modeling: The modeling stage involved training a machine learning algorithm to predict vehicular congestion. This process included:Model Selection: A Random Forest Classifier was used, known for its ability to handle large datasets and detect complex interactions between variables [32].Data Splitting: The dataset was split into an 80% training set and a 20% test set, ensuring a fair and representative evaluation of the model. Training and Prediction: The model was trained using historical data and evaluated through predictions on the test set.

-

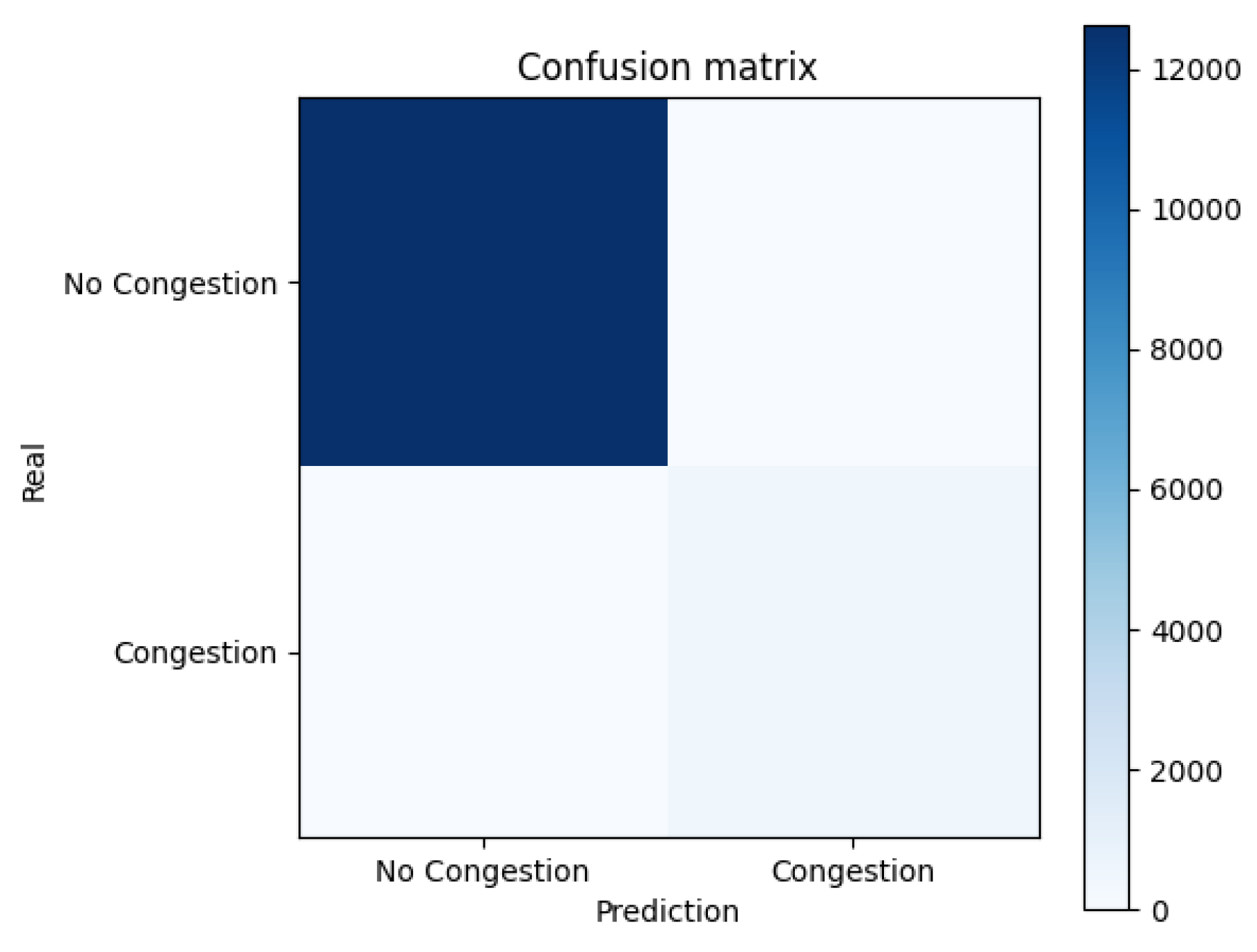

Model evaluation: The predictive model’s performance was evaluated using standard machine learning metrics:Classification Report: Metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were generated, demonstrating the model’s high ability to correctly identify intervals with and without congestion. Confusion Matrix: This matrix illustrated the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, providing valuable information for interpreting results and making future adjustments [33].

-

Results visualization: To facilitate the interpretation of findings and communicate the results, key visualizations were developed:Average Speed Graph: Graphs clearly and comprehensibly displayed average speed patterns by lane, highlighting critical congestion moments [34]. Confusion Matrix Visualization: The confusion matrix was presented in a graphical format, allowing for a visual understanding of the model’s performance and identification of areas for improvement. This systematic and evidence-based approach provided a comprehensive view of vehicular traffic behavior and established a solid foundation for the development of intelligent traffic management systems in urban environments.

3.3. Rigor Cycle

4. Results

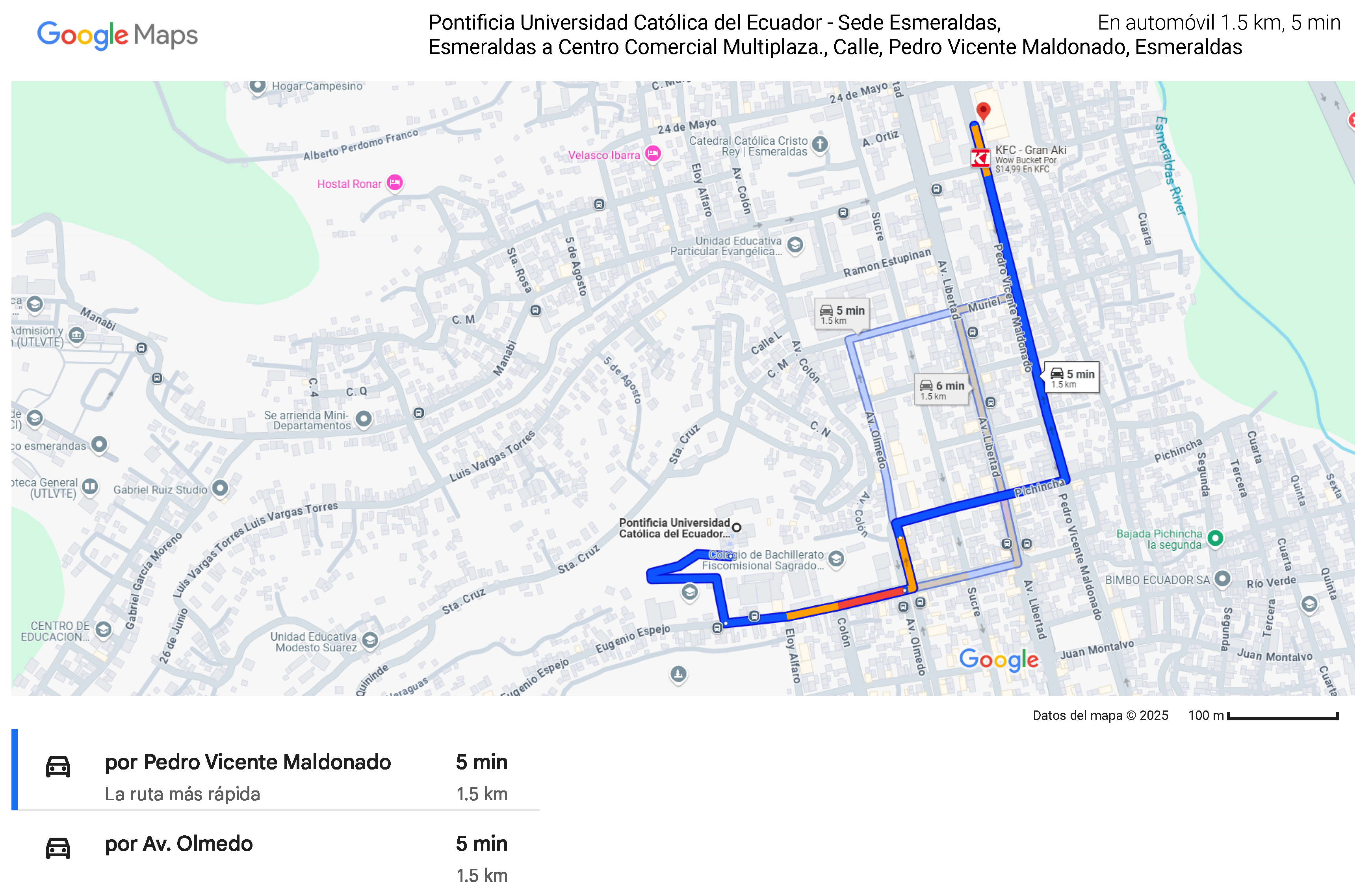

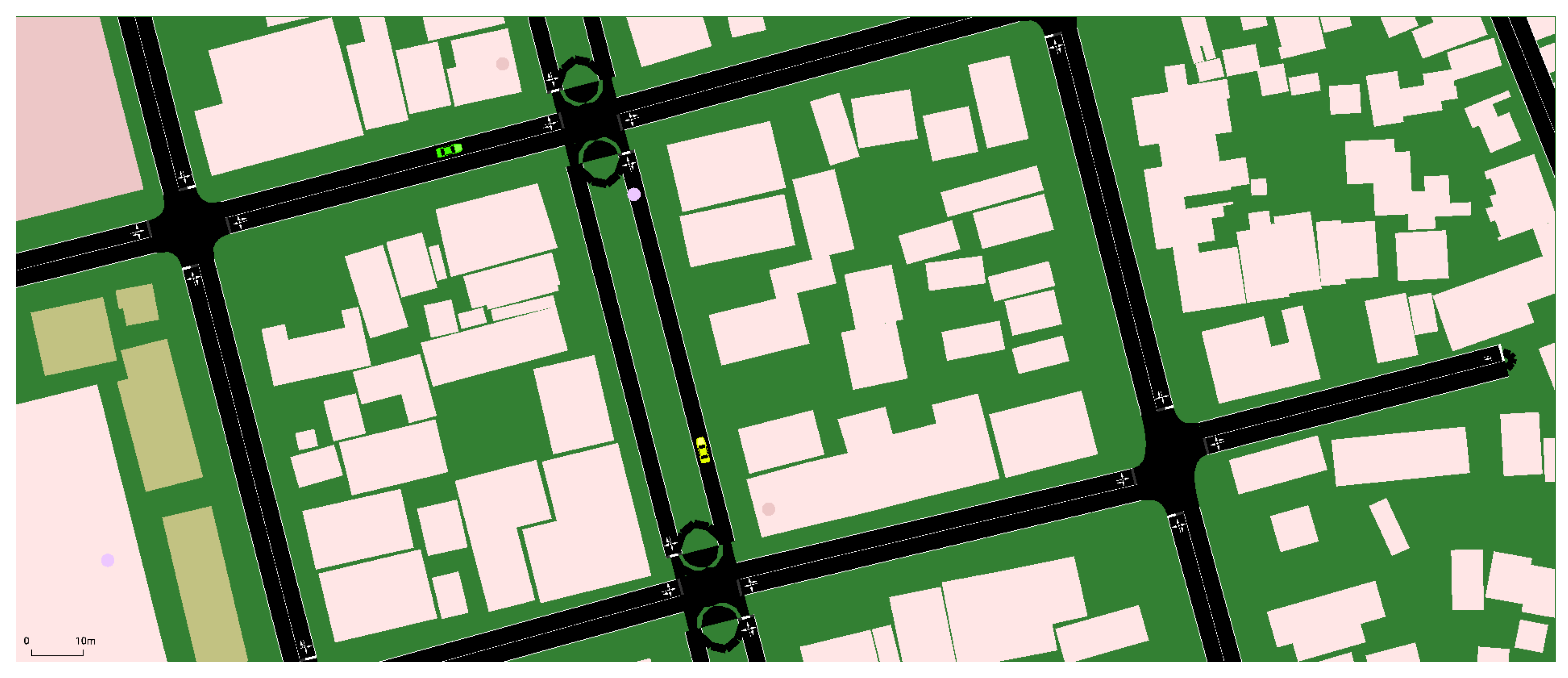

4.1. Vanet Simulation

| 1lAvenue | Nodes |

|---|---|

| 1143925089 | |

| Espejo | 1143926012 |

| 1143931858 | |

| Olmedo | 1143931858 |

| 1143925281 | |

| Pichincha | 1143925281 |

| 1143927931 | |

| Maldonado | 1143927931 |

| 1143927077 | |

| 1142711596 |

4.2. Average Speeds per 10-Minute Interval and Lane

4.3. Congestion Prediction (Machine Learning Model)

5. Discussion

5.1. Addressing the Research Question

5.2. VANET Modeling and Simulation

5.3. Congestion Detection Based on Average Speeds

5.4. Performance of Predictive Models

5.5. Potential of Machine Learning in Congestion Prediction

5.6. Potential of Machine Learning in Congestion Prediction

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, P.G.; Lekhana, P.; Tejaswi, M.; Chandrakala, S. Effects of vehicular emissions on the urban environment- a state of the art. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 45, 6314–6320. [CrossRef]

- Chango, W.; Logroño, S.; Játiva, M.; Aguilar, P. Vehicular Ad-Hoc Network (VANET). Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 2024, 870 LNNS, 160–176. [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, Y.; Alemayehu, E.; Schröder, D. Examining Car Accident Prediction Techniques and Road Traffic Congestion: A Comparative Analysis of Road Safety and Prevention of World Challenges in Low-Income and High-Income Countries. Journal of Advanced Transportation 2023, 2023, 6643412. [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.S.; Hasan, M.K.; Hassan, R.; Saeed, R.A.; Hassan, M.B.; Islam, S.; Nafi, N.S.; Bevinakoppa, S. Machine Learning Technologies for Secure Vehicular Communication in Internet of Vehicles: Recent Advances and Applications. Security and Communication Networks 2021, 2021, 8868355. [CrossRef]

- Boukerche, A.; Tao, Y.; Sun, P. Artificial intelligence-based vehicular traffic flow prediction methods for supporting intelligent transportation systems. Computer Networks 2020, 182, 107484. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, L.L.; Mezher, A.M.; Barbecho Bautista, P.A.; Astudillo León, J.P.; Igartua, M.A. A Multimetric Predictive ANN-Based Routing Protocol for Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 86037–86053. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Campoverde, J.J.; Rivera-Campoverde, N.; Molina Campoverde, P.A.; Bermeo Naula, A.K. Urban Mobility Pattern Detection: Development of a Classification Algorithm Based on Machine Learning and GPS. Sensors 2024, Vol. 24, Page 3884 2024, 24, 3884. [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.G.; Pedreira, C.E. Recent advances in decision trees: an updated survey. Artificial Intelligence Review 2022 56:5 2022, 56, 4765–4800. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, S.; Ahad, M.A.; Tripathi, G.; Feroz, N.; Casalino, G. Enabling Technologies for Urban Smart Mobility: Recent Trends, Opportunities and Challenges. Sensors 2021, Vol. 21, Page 2143 2021, 21, 2143. [CrossRef]

- Faheem, H.B.; Shorbagy, A.M.E.; Gabr, M.E. Impact Of Traffic Congestion on Transportation System: Challenges and Remediations - A review. Mansoura Engineering Journal 2024, 49, 18. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Rafay, M.; Khan, R.D.A.; Sorn, M.K.; Jiang, H.; Ali, Y.; Rafay, M.; Khan, R.D.A.; Sorn, M.K.; Jiang, H. Traffic Problems in Dhaka City: Causes, Effects, and Solutions (Case Study to Develop a Business Model). Open Access Library Journal 2023, 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.A.; Malami, S.I.; Alanazi, F.; Ounaies, W.; Alshammari, M.; Haruna, S.I. Sustainable Traffic Management for Smart Cities Using Internet-of-Things-Oriented Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS): Challenges and Recommendations. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 9859 2023, 15, 9859. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, S.M.; Mirzahossein, H. Efficiency and Safety of Traffic Networks Under the Effect of Autonomous Vehicles. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology - Transactions of Civil Engineering 2024, 48, 1861–1885.

- Verma, S.K.; Verma, R.; Singh, B.K.; Sinha, R.S. Management of Intelligent Transportation Systems and Advanced Technology. Energy, Environment, and Sustainability 2024, Part F2419, 159–175. [CrossRef]

- Laanaoui, M.D.; Lachgar, M.; Mohamed, H.; Hamid, H.; Villar, S.G.; Ashraf, I. Enhancing Urban Traffic Management Through Real-Time Anomaly Detection and Load Balancing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 63683–63700. [CrossRef]

- Aouedi, O.; Vu, T.H.; Sacco, A.; Nguyen, D.C.; Piamrat, K.; Marchetto, G.; Pham, Q.V. A Survey on Intelligent Internet of Things: Applications, Security, Privacy, and Future Directions. IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials 2024, [2406.03820]. [CrossRef]

- Tshibangu-Muabila, J.; Mouelhi, S.; Leserf, P.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. Refining SUMO Simulation Strategies for Realistic Traffic Patterns: Insights from Field Experience. 2023 7th International Conference on System Reliability and Safety, ICSRS 2023 2023, pp. 237–246. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yan, H.; Lang, Z. A study on traffic congestion prediction based on random forest model. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology 2024, 101, 738–749. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Subhani, M.M.; Roullier, B.; Anjum, A.; Zhu, R. Congestion prediction for smart sustainable cities using IoT and machine learning approaches. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 64, 102500. [CrossRef]

- Blanka, C.; Krumay, B.; Rueckel, D. The interplay of digital transformation and employee competency: A design science approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 178, 121575. [CrossRef]

- Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Batelaan, O.; Fadaee, M.; Hinkelmann, R. Ensemble machine learning paradigms in hydrology: A review. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 598, 126266. [CrossRef]

- Schjerven Id, F.E.; Lindseth, F.; Steinsland, I. Prognostic risk models for incident hypertension: A PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis. PubMed Central 2024. [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.B.; Ayton, L.J. A Periodic Extension to the Fokas Method for Acoustic Scattering by an Infinite Grating. Applied System Innovation 2025. [CrossRef]

- Angarita-Zapata, J.S.; Maestre-Gongora, G.; Calderín, J.F. A Bibliometric Analysis and Benchmark of Machine Learning and AutoML in Crash Severity Prediction: The Case Study of Three Colombian Cities. Sensors 2021, Vol. 21, Page 8401 2021, 21, 8401. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, E.; Alavi Moghaddam, M.R.; Kowsari, E. A systematic and critical review on development of machine learning based-ensemble models for prediction of adsorption process efficiency. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 379, 134588. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Ulvi, H.; Yerlikaya, M.A.; Yildiz, K. Urban Traffic Mobility Optimization Model: A Novel Mathematical Approach for Predictive Urban Traffic Analysis. Applied Sciences 2024, Vol. 14, Page 5873 2024, 14, 5873. [CrossRef]

- Kiangala, S.K.; Wang, Z. An effective adaptive customization framework for small manufacturing plants using extreme gradient boosting-XGBoost and random forest ensemble learning algorithms in an Industry 4.0 environment. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 4, 100024. [CrossRef]

- Chiabaut, N.; Faitout, R. Traffic congestion and travel time prediction based on historical congestion maps and identification of consensual days. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2021, 124, 102920, [2011.05073]. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Lee, E. Congestion boundary approach for phase transitions in traffic flow. Transportmetrica B: Transport Dynamics 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ul Abideen, Z.; Sun, X.; Sun, C. Traffic flow prediction: A 3D adaptive multi-module joint modeling approach integrating spatial-temporal patterns to capture global features. Journal of Forecasting 2024, 43, 2766–2791. [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, A.; Lambert-Lacroix, S.; Poggi, J.M. Random forests for global sensitivity analysis: A selective review. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021, 206, 107312. [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Masarone, S.; Watson, D.; Barnes, M.R. The benefits and pitfalls of machine learning for biomarker discovery. Cell and Tissue Research 2023, 394, 17–31.

- Shen, Y.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, E.; Jin, X.; Fan, Y.; Campbell, K.D. To Explain or Not to Explain: A Study on the Necessity of Explanations for Autonomous Vehicles. preprints 2020, [2006.11684].

- Feroz Khan, A.B.; Ivan, P. Integrating Machine Learning and Deep Learning in Smart Cities for Enhanced Traffic Congestion Management: An Empirical Review. Journal of Urban Development and Management 2023, 2, 211–221. [CrossRef]

- Somanath, S.; Naserentin, V.; Eleftheriou, O.; Sjölie, D.; Wästberg, B.S.; Logg, A. Towards Urban Digital Twins: A Workflow for Procedural Visualization Using Geospatial Data. Remote Sensing 2024, Vol. 16, Page 1939 2024, 16, 1939. [CrossRef]

- Shaygan, M.; Meese, C.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.G.; Nejad, M. Traffic prediction using artificial intelligence: Review of recent advances and emerging opportunities. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2022, 145, 103921, [2305.19591]. [CrossRef]

- Fremont, D.J.; Kim, E.; Pant, Y.V.; Seshia, S.A.; Acharya, A.; Bruso, X.; Wells, P.; Lemke, S.; Lu, Q.; Mehta, S. Formal Scenario-Based Testing of Autonomous Vehicles: From Simulation to the Real World. 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, ITSC 2020 2020, [2003.07739]. [CrossRef]

| Colors | Legend |

|---|---|

| Green | No traffic delay |

| Orange | Average amount of traffic |

| Red | Traffic delay |

| Dark red | Very slow traffic speed or stopped vehicles |

| Location | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|

| Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador, Esmeraldas Campus | 0.9697314545985082 | -7.965.741.360.677.340 |

| Multiplaza Shopping Mall | 0.9765167208899496 | -796.534.656.373.013 |

| osm.net.xml, osm.passenger.trips.xml and osm.poly.xml files |

|---|

| <configuration xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:noNamespaceSchemaLocation="http://sumo.dlr.de/xsd/sumoConfiguration.xsd"> <input> <net-file value="osm.net.xml"/> //Road network archive <route-files value="osm.passenger.trips.xml"/> //Vehicle demand <additional-files value="osm.poly.xml"/> //polygons </input> <processing> <ignore-route-errors value="true"/> </processing> <routing> <device.rerouting.adaptation-steps value="18"/> <device.rerouting.adaptation-interval value="10"/> </routing> <gui_only> <gui-settings-file value="osm.view.xml"/> </gui_only> </configuration> |

| No. | Vehicle | GPS Coordinates | Speed (km/h) | Edge | Lane | Displacement (m) | Rotation Angle |

| 1 | veh0 | [-79.6527244472348, 0.9724697345761849] | 0.00 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 0.00 | 256.58 |

| 2 | veh0 | [-79.65274218875825, 0.9724654799800492] | 7.31 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 2.03 | 256.58 |

| 3 | veh0 | [-79.6527770144728, 0.972457128422303] | 14.34 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 6.01 | 256.58 |

| 4 | veh0 | [-79.65283420828086, 0.9724434127688836] | 23.55 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 12.56 | 256.58 |

| 5 | veh0 | [-79.65290650082167, 0.9724260762846564] | 29.77 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 20.83 | 256.58 |

| 6 | veh0 | [-79.6529912316884, 0.9724057569608561] | 34.90 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 30.52 | 256.58 |

| 7 | veh0 | [-79.653090648525, 0.9723819157880809] | 40.94 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 41.89 | 256.58 |

| 8 | veh1 | [-79.65547536705684, 0.9726013953539084] | 0.00 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 0.00 | 151.07 |

| 9 | veh0 | [-79.65320457887624, 0.9723545941209514] | 46.92 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 54.93 | 256.58 |

| 10 | veh1 | [-79.65546332004871, 0.9725893245511535] | 6.81 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 1.89 | 143.21 |

| 11 | veh0 | [-79.6532899510483, 0.9723341209944739] | 35.16 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 64.69 | 256.58 |

| 12 | veh1 | [-79.65543637050122, 0.9725623217742456] | 15.23 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 6.12 | 134.85 |

| 13 | veh0 | [-79.65334443155311, 0.972321056006417] | 22.44 | 416064999#0 | 416064999#0_0 | 70.93 | 256.58 |

| 14 | veh1 | [-79.65540097928533, 0.972526860655301] | 20.01 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 11.68 | 134.85 |

| 15 | veh1 | [-79.65535672981196, 0.972482523782328] | 25.01 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 18.63 | 134.85 |

| 16 | veh1 | [-79.655299346461, 0.9724196949266831] | 33.97 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 28.07 | 137.78 |

| 17 | veh0 | [-79.65343859808162, 0.9721813555896256] | 28.01 | 99172472#8 | 99172472#8_0 | 94.52 | 165.66 |

| 65508 | veh1 | [-79.65523237359902, 0.972335033453903] | 43.12 | -98769545#0 | -98769545#0_0 | 40.04 | 143.35 |

| Lane | Cluster start | Cluster end | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| -376593940#1 | 1143927076 | P_Don_Bosco | 22,2 |

| -376593940#0 | P_Don_Bosco | P_I_Cementerio | 22,2 |

| -98881766#7 | cluster_1143931389_1143931671 | 1389_1143931671 | 22,2 |

| -98881766#5 | cluster_1143931389_1143931671 | cluster_1143925301_1143931836 | 22,2 |

| -98881766#3 | 1143931858 | cluster_1143925301_1143931836 | 22,2 |

| -98881766#2 | 1143931858 | cluster_1143925021_1143927211 | 22,2 |

| 285832009#0 | cluster_1143925021_1143927211 | cluster_1143929880_1143932435 | 22,2 |

| 285832009#1 | cluster_1143929880_1143932435 | cluster_1143926346_1143929933 | 21,2 |

| 285832009#2 | cluster_1143926346_1143929933 | cluster_1143926446_1143932048 | 22,2 |

| 285832009#3 | cluster_1143926446_1143932048 | cluster_1142711217_1142713649 | 22,2 |

| 98769527#2 | cluster_1142711217_1142713649 | 1142711596 | 13,9 |

| -98739478#6 | 1142711596 | cluster_1142544813_1142545892 | 27,8 |

| Average | 21,9 | ||

| N° | Interval_10min | Vehicle_travel_lane | Average_speed | Congestion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | -412782454#0_0 | 7,82 | True |

| 2 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | -412782454#1_0 | 7,62 | True |

| 3 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | -412787010#0_0 | 9,32 | True |

| 4 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | -412787012#1_0 | 5,40 | True |

| 5 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | :1142348508_0_0 | 9,53 | True |

| 6 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | :1142349518_7_0 | 8,94 | True |

| 7 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | :1142545047_10_0 | 9,52 | True |

| 8 | 12/8/2022 18:20 | :1142545329_1_0 | 9,86 | True |

| 310 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 1cMetrics | Accuracy | Recall | F1-score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 12628 |

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 474 |

| accuracy | 1 | 1.00 | 13102 | |

| macro avg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 13102 |

| weighted avg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 13102 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).