Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Model

2.1. Subordination Procedure

2.2. Einstein Universe

2.3. Kinematic Model for the Scale Factor

2.3.1. Fundamentals

- 1.

- Drawing an analogy with the Bohr model of the atom, we assume that the primordial Universe, in internal time , can only exist in sharply defined stationary states with unique energies, which are described by Einstein Universes. The ability for transitions between these states is also postulated.

- 2.

- The internal and physical times are interconnected via a Lévy-type subordinator. It is hypothesized that the corresponding Lévy exponent accounts for the aggregation of ticks from two independent clocks, representing ordinary matter and dark matter.

- 3.

- The observable scale factor in physical time t is conceptualized as the mean outcome of a scale factor jump between two stationary states of the primordial Universe, averaged over an ensemble of realizations of the inverse subordinator.

2.3.2. Subordinated Scale Factor

3. Asymptotic Behavior of the Scale Factor

3.1. The Short-Time Limit

3.2. The Long-Time Limit

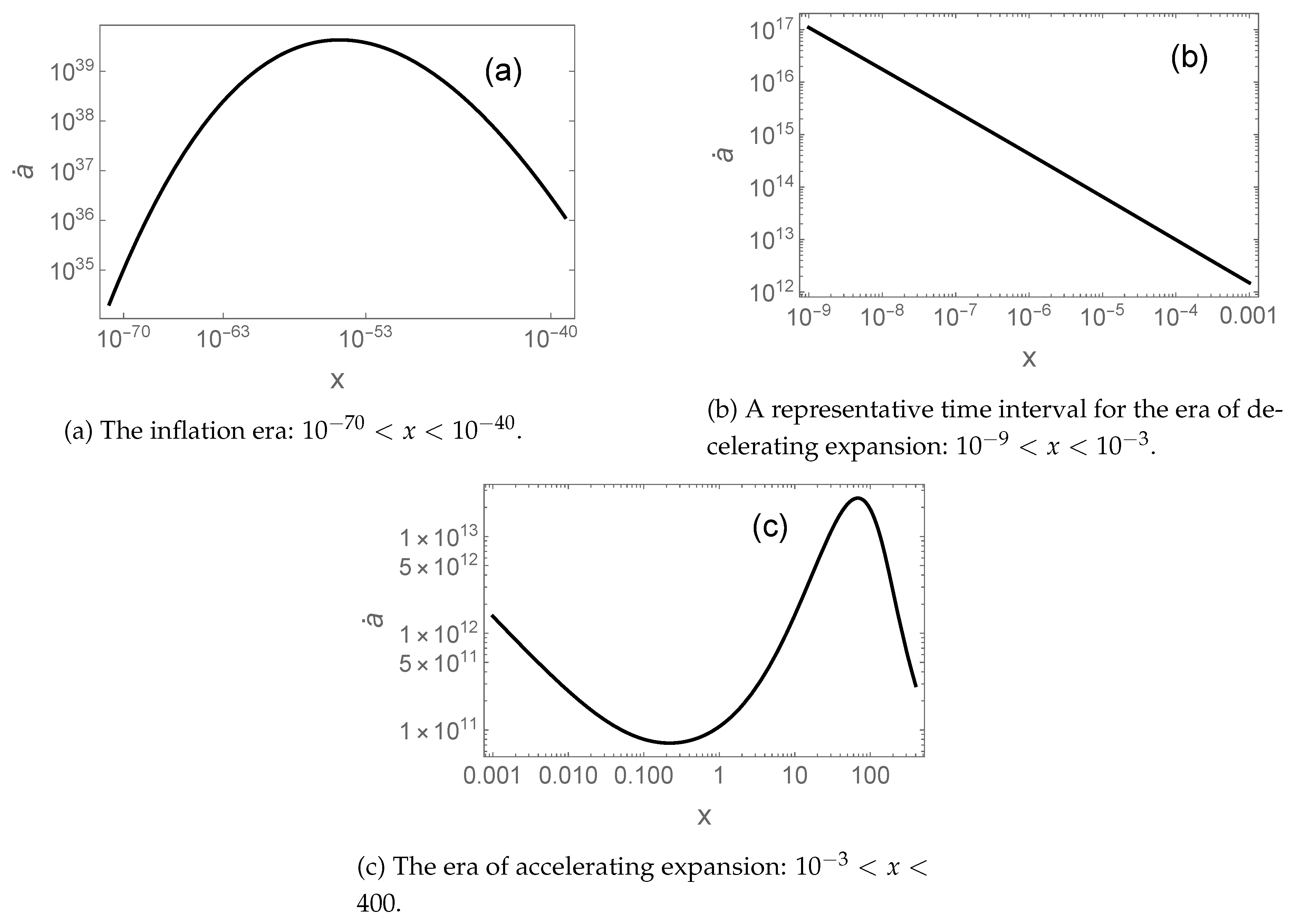

4. A Numerical Illustration of Kinematic of the Scale Factor

5. Matter and Radiation in the Universe

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDM | -cold dark matter |

| CMB | cosmic microwave background |

| BAO | baryon acoustic oscillation |

| CTRW | continuous-time random walks |

| RW | Robertson–Walker |

| JWST | James Webb Space Telescope |

| OM | our model |

| CCC+TL | tired light model with covarying coupling constants |

Appendix A. Completely Monotone and Bernstein Functions

- (1)

- The completely monotone function appears as Laplace transforms of non-negative densities:with a non-negative function . They are defined on the nonnegative half-axis and have a property that for all whole numbers n and for all , .

- (2)

-

The Bernstein functions are non-negative functions whose first derivative is completely monotone. The following properties would be of importance:

- (a)

- If and are two completely monotone functions, their product is a completely monotone function.

- (b)

- If and are two complete Bernstein functions, their linear combination with nonnegative weights , is a complete Bernstein function.

- (c)

- If is a complete Bernstein function, then the function is also a complete Bernstein function.

- (d)

- If is a complete Bernstein function, then the functions and , , are such as well.

- (e)

- If is complete Bernstein function, the functions and , , are completely monotone.

- (f)

- The function with is complete Bernstein function.

More details can be found in Ref. [23].

Appendix B. Asymptotic Behavior of gα(z)

Appendix C. Derivation of Eqs. (48) and (49)

References

- Frieman, J.A.; Turner, M.S.; Huterer, D. Dark energy and the accelerating universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 46, 385–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Valentino, E.; Mena, O.; Pan, S.; Visinelli, L.; Yang, W.; Melchiorri, A.; Mota, D.F.; Riess, A.G.; Silk, J. In the realm of the Hubble tension—a review of solutions. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2021, 38, 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, M.P. Information dark energy can resolve the Hubble tension and is falsifiable by experiment. Entropy 2022, 24, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.; Bartolo, N.; Basak, S.; et al. Planck 2018 results-VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A.G.; Casertano, S.; Yuan, W.; Bowers, J.B.; Macri, L.; Zinn, J.C.; Scolnic, D. Cosmic distances calibrated to 1% precision with Gaia EDR3 parallaxes and Hubble Space Telescope photometry of 75 Milky Way Cepheids confirm tension with ΛCDM. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2021, 908, L6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.P. JWST early Universe observations and ΛCDM cosmology. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2023, 524, 3385–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, W. Curvature tension: Evidence for a closed universe. Physical Review D 2021, 103, L041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, I.; Cox, E.C. Physical nature of bacterial cytoplasm. Physical review letters 2006, 96, 098102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskin, N. Time fractional quantum mechanics. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2017, 102, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mankin, R.; Rekker, A. Effects of transient subordinators on the firing statistics of a neuron model driven by dichotomous noise. Physical Review E 2020, 102, 012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankin, R.; Rekker, A.; Paekivi, S. Statistical moments of the interspike intervals for a neuron model driven by trichotomous noise. Physical Review E 2021, 103, 062201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfling, F.; Franosch, T. Anomalous transport in the crowded world of biological cells. Reports on Progress in Physics 2013, 76, 046602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutner, R.; Masoliver, J. The continuous time random walk, still trendy: Fifty-year history, state of art and outlook. The European Physical Journal B 2017, 90, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, S.C.; Xie, X.S. Generalized Langevin equation with fractional Gaussian noise: subdiffusion within a single protein molecule. Physical review letters 2004, 93, 180603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, E. Fractional langevin equation. Physical Review E 2001, 64, 051106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankin, R.; Laas, K.; Lumi, N.; Rekker, A. Cage effect for the velocity correlation functions of a Brownian particle in viscoelastic shear flows. Physical Review E 2014, 90, 042127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankin, R.; Laas, K.; Laas, T.; Paekivi, S. Memory effects for a stochastic fractional oscillator in a magnetic field. Physical Review E 2018, 97, 012145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montroll, E.W.; Weiss, G.H. Random walks on lattices. II. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1965, 6, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, I.M.; Klafter, J. From diffusion to anomalous diffusion: A century after Einstein’s Brownian motion. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2005, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scher, H.; Montroll, E.W. Anomalous transit-time dispersion in amorphous solids. Physical Review B 1975, 12, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eule, S.; Friedrich, R. Subordinated Langevin equations for anomalous diffusion in external potentials—biasing and decoupled external forces. Europhysics Letters 2009, 86, 30008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanislavsky, A.; Weron, K.; Weron, A. Anomalous diffusion with transient subordinators: A link to compound relaxation laws. The Journal of chemical physics 2014, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandev, T.; Sokolov, I.M.; Metzler, R.; Chechkin, A. Beyond monofractional kinetics. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2017, 102, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Paekivi, S.; Mankin, R. Bimodality of the interspike interval distributions for subordinated diffusion models of integrate-and-fire neurons. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2019, 534, 122106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzeł, S.; Mydlarczyk, W.; Jurlewicz, A. Accelerating subdiffusions governed by multiple-order time-fractional diffusion equations: Stochastic representation by a subordinated Brownian motion and computer simulations. Physical Review E 2013, 87, 032110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, J.; Magdziarz, M. Fractional Fokker-Planck equation with tempered α-stable waiting times: Langevin picture and computer simulation. Physical Review E 2010, 82, 011117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandev, T.; Chechkin, A.V.; Korabel, N.; Kantz, H.; Sokolov, I.M.; Metzler, R. Distributed-order diffusion equations and multifractality: Models and solutions. Physical Review E 2015, 92, 042117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feynman, R.; Hibbs, A. The path integral formulation of quantum mechanics; McGraw-Hiill: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Birell, N.; Davies, P. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ibragimov, I.A.; Chernin, K.E. On the unimodality of geometric stable laws. Theory of Probability & Its Applications 1959, 4, 417–419. [Google Scholar]

- Barkai, E. Fractional Fokker-Planck equation, solution, and application. Physical Review E 2001, 63, 046118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israelit, M.; Rosen, N. A singularity-free cosmological model in general relativity. Astrophysical Journal, Part 1 (ISSN 0004-637X), vol. 342, July 15, 1989, p. 627-634. 1989, 342, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijjas, A.; Steinhardt, P.J. A new kind of cyclic universe. Physics Letters B 2019, 795, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D.; Brout, D.; Carr, A.; Riess, A.G.; Davis, T.M.; Dwomoh, A.; Jones, D.O.; Ali, N.; Charvu, P.; Chen, R.; et al. The Pantheon+ analysis: The full data set and light-curve release. The Astrophysical Journal 2022, 938, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, F. Introduction to Asymptotic Analysis. In Introduction to Asymptotics and Special Functions; Academic Press, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | CDM | CCC+TL | OM | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 72.6 | 72 | ||

| -0.64 | -0.78 | -0.69 | NA | |

| 13.8 | 26.7 | 34.5 | Gyr | |

| 0.03 | Gyr | |||

| 0.5 | 5.8 | 11.5 | Gyr | |

| 0.2 | 3.5 | 7.8 | Gyr |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).