1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women worldwide and significantly contributes to cancer-related morbidity and mortality. It accounts for approximately 7% of cancer deaths globally, highlighting the urgent need for effective management strategies [

1]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the burden is particularly heavy, with breast cancer representing 25% of all cancers among women [

2]. Despite advancements in diagnostics and treatment modalities, the incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer continue to rise, underscoring formidable systemic challenges in managing this disease [

3,

4]. In South Africa specifically, breast cancer is increasing at an alarming rate of 5% annually [

5]. The pressing need for timely diagnosis and intervention is paramount for improving treatment outcomes. However, many patients in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) present with late-stage breast cancer, as a significant number of cases remain unreported [

6]. It is projected that nearly three-quarters of all cancer deaths will occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by 2030 [

7], underscoring the urgency for effective cancer control policies and therapeutic resources. Furthermore, the global cancer burden is anticipated to rise dramatically over the next few decades, with an expected 400% increase in incidences within low-income countries [

7]. This situation has been further exacerbated by diseases like the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disrupted healthcare delivery systems worldwide. Cancer patients have faced significant barriers in accessing care, with treatment delays and increased anxiety becoming a common narrative [

8,

9]. Specifically, the challenges posed by the pandemic have demanded rapid adaptations in treatment protocols to accommodate safety concerns and resource limitations, creating an opportune context for exploring treatment strategies that minimise patient burden while maintaining efficacy.

Radiation therapy (RT) has historically represented a cornerstone of breast cancer management. Pioneers like Marie Curie laid the groundwork for RT, transitioning it from experimental procedures to a fundamental component of oncological care [

10]. Over recent decades, the field of radiation oncology has witnessed a paradigm shift towards innovative therapeutic approaches, particularly hypofractionated radiotherapy (HFRT). This technique involves delivering higher doses of radiation over fewer treatment sessions, thereby streamlining patient care and potentially improving clinical outcomes [

11]. Despite the compelling evidence supporting hypofractionation (HF), its acceptance varies significantly across geographical regions and institutional settings. Factors such as institutional capabilities, treatment paradigms, and physician preferences contribute to this variability [

12,

13]. The COVID-19 pandemic has spotlighted these discrepancies, as hypofractionation has emerged as an attractive option aimed at reducing the risks associated with prolonged treatments and minimising patient exposure in healthcare settings [

14,

15]. The rising interest in HF coincides with an urgent need to understand the biological mechanisms underlying the varying tumour responses to altered radiation schedules. Comprehensive

in vitro studies can provide essential insights into the cellular responses that can support the optimisation of treatment regimens tailored to individual patient profiles. Understanding the differential biological effectiveness of hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiation schedules is particularly critical considering the high incidence of breast cancer in LMICs, where resource constraints often complicate access to advanced therapeutic options.

The primary goal of this study was to generate in vitro evidence supporting the use of hypofractionation as an effective treatment strategy for breast cancer compared to conventional fractionation (CF). By systematically investigating the cellular responses of breast cell lines to varying radiation doses and schedules, this research aimed to inform clinical protocols and enhance treatment strategies, particularly in resource-limited contexts. The study assessed the radiobiological responses of breast cancer cell lines to both HFRT and conventionally fractionated radiation therapy (CFRT), thereby contributing valuable insights into optimising the therapeutic ratio of radiation therapy with a focus on maximising tumour control while minimising damage to surrounding normal tissue. This research underscored the critical need for innovative, evidence-based approaches to breast cancer management that aligned with contemporary clinical practices. Given the escalating burden of breast cancer and the additional challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, rigorous investigation of HFRT was essential for enhancing treatment efficacy and improving patient outcomes. Ultimately, the findings of this study aimed to not only provide insights applicable to clinical practices but also to address the pressing healthcare challenges faced by underserved regions, including those in Sub-Saharan Africa, paving the way for more effective management of breast cancer in the context of global health disparities.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive investigation was carried out to assess the impacts of HF and CF irradiation on breast cancer cell lines. The radiation doses were determined using the clonogenic survival assay and were modified to ensure a comparable biologically effective dose (BED) across both treatment protocols. The cellular responses to radiation were analysed by tracking cell proliferation and conducting radiobiological assays, aimed at clarifying the influence of HF and CF on cellular behaviour and contributing to the development of optimal treatment strategies. Notably, the use of

in vitro models involving isolated cells facilitated the control of multiple variables, allowing for the specific examination of the effects related to different fractionation schemes. For HF, a single fraction was chosen to represent the higher dose delivered, as demonstrated by previous studies [

16,

17].

2.1. Breast Cell Lines

This study utilised the following human breast cell lines: cancerous cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231), and a non-cancerous cell line (MCF-10A). The MCF-7 cell line was cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM-F12) (Catalogue number 11320074), while MDA-MB-231 was maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (Catalogue number 21875034). MCF-10A was cultured in DMEM-F12 supplemented with insulin, epidermal growth factor (EGF), and hydrocortisone. All media and supplements were obtained from Merck Life Science (Pty) Ltd. The cancerous cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 are characterised by distinct biological traits, with MCF-7 being a hormone-sensitive breast adenocarcinoma cell line that expresses estrogen (ER+) and progesterone receptors (PR+), while demonstrating wild-type p53 status [

18,

19]. In contrast, MDA-MB-231 is classified as a triple-negative breast cancer cell line, inherently resistant to hormonal therapy, and characterised by mutant p53 status along with high metastatic potential [

18,

19]. MCF-10A, as a non-cancerous breast epithelial cell line, exhibits wild-type p53 status and possesses characteristics typical of normal breast tissue [

20]. This makes MCF-10A crucial for establishing a baseline against which cancerous cell line responses can be compared when assessing radiation treatment outcomes.

2.2. Cell Culture Irradiation

Cell cultures were exposed to cobalt-60 γ-rays emitted from a source with an activity of 292 TBq. The cobalt-60 source, with a decay constant (λ) of 3.6 × 10⁻⁴ per day, produces photons at energies of 1.17 and 1.33 MeV, with an effective energy of 1.25 MeV. Irradiation occurred between a 5-mm acrylic sheet and a 50-mm backscatter material, delivering a mean dose rate of 0.24 Gy/min (range: 0.23 - 0.25 Gy/min).

2.3. Doubling Time, Adaptive Response and Clonogenic Survival Assay (CSA)

The doubling time of the cell lines was calculated using a standard formula [

21,

22]. Cells were seeded at a predetermined density, and initial counts were recorded. Subsequent counts were taken at 24-hour intervals over 72 hours to monitor proliferation. Prior to experimentation, cells were cultured for several weeks to ensure active growth. A priming dose of 0.5 Gy was administered to assess the adaptive doubling time, with additional serial counts performed to evaluate the effect of low-dose radiation (0.5 Gy) on cell proliferation.

For the clonogenic survival assay (CSA), doses were administered in increments of 2 Gy, ranging from 2 to 10 Gy, with treatment durations adjusted to account for source deterioration per established standards. The CSA was used to assess the surviving fraction of cells following exposure to varying doses of radiation [

23]. The CSA served as the primary endpoint for evaluating radiation sensitivity and α/β ratios of the cell lines. Each cell line was seeded in 6-well plates at densities corresponding to each radiation dose and subsequently irradiated. A total of three technical replicates were performed for each experimental condition, alongside 6 biological replicates per cell line and endpoint to ensure the reliability of the results. After incubating the cell cultures for six doubling times for colony formation, the surviving fractions at all doses were calculated. Cell survival data were fitted to the linear-quadratic (LQ) model using non-linear regression analysis with the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm [

24] to generate survival curves. The LQ model equation:

was employed to model the relationship between radiation dose and survival fraction, where S(D) represents the surviving fraction at dose D, and α and β are parameters extracted from the curve fit. The fitted curve allowed for the extraction of the LQ model parameters (α) and (β), representing the coefficients of the linear and quadratic components of cell killing, respectively. Additionally, D

50, the absorbed radiation dose required for 50% cell killing, was calculated using the LQ model equation. The relative sensitivity (RS), indicating the ratio of D

50 values between non-cancerous and cancerous cell lines, was also determined. The extracted α and β values were interpreted in the context of radiosensitivity, with higher α/β values suggesting greater sensitivity to radiation.

2.4. Biological Effective Dose (BED)

The biologically effective dose (BED) quantifies the biological effectiveness of radiation therapy by considering the dose per fraction and the radiobiological parameters, alpha (α) and beta (β), across different regimens [

25]. BED provides a standardised measure for comparing the effects of radiation doses delivered over varying schedules, thereby facilitating the optimisation of radiation therapy protocols. In the HF model, the BED for a single fraction was calculated using Equation (2):

where D is the total dose, d is the dose per fraction, and α/β is the ratio of alpha to beta [

25]. By substituting the calculated BED from conventional fractionation of 2 Gy per fraction over 4 fractions (totalling 8 Gy), the required dose for hypofractionation (D = d for a single fraction) can be determined. In this context, the dose (D) for hypofractionation can be calculated as the only unknown variable in the BED equation, given that all other variables have been established using the conventional fractionation scheme.

2.5. Split Dose Experiment and the Clonogenic Survival Assay

To investigate the effects of varying time gaps between radiation fractions on cell survival, cells were seeded in T25 flasks and irradiated with a total dose of 2 Gy, divided into 2 fractions with intervals of 1 to 6 hours. The cells first received 1 Gy, followed by incubation for the respective times. After this, a second 1-Gy fraction was delivered, and the flasks were incubated for a duration equivalent to six doubling times to allow for colony formation and surviving fractions. For staining, a 0.5% crystal violet solution (w/v) was prepared by dissolving 500 mg of crystal violet (Merck Life Science, Catalogue number: 179337) in a mixture of 25 mL AR-grade methanol (Merck Life Science, Catalogue number: 179335) and 75 mL distilled water. This solution was utilised after the cells were fixed using ice-cold 100% methanol for 10 minutes. Cells were washed with cold PBS, then incubated with 3 mL of 0.5% crystal violet in 25% methanol for 10 minutes at room temperature. Excess dye was removed, and the plates were rinsed with water to halt the staining process, followed by air drying. Colonies were manually counted by visually identifying distinct morphologically viable colonies. The surviving fraction at each interval was compared to that of cells irradiated with the full 2 Gy dose without time gaps. The repair factor was calculated as the percentage change in survival due to each time interval, providing insight into the cells' capacity to repair DNA damage.

2.6. Gamma-H2AX Foci Assay

The γH2AX foci assay, as described by Nair et al. (2021), was employed to investigate DNA damage and repair kinetics following radiation exposure [

26]. One million cells were irradiated with 2 Gy and incubated for 0-6 hours. For fixation, cells were treated with PBS containing 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA, freshly prepared) for 20 minutes, followed by overnight storage in PBS with 0.5% PFA. Immunostaining was performed using a primary anti-γ-H2AX antibody (catalogue number: 613402, Biocom Africa) and a secondary rabbit anti-mouse FITC antibody (catalogue number: 31561, LTC Tech South Africa), prior to quantification. The average number of γH2AX foci per cell was evaluated using the MetaCyte software module of the Metafer version 4 scanning system (MetaSystems, Germany). A minimum of three slides were scored for each exposure condition.

To illustrate the repair processes of DNA damage induced by radiation, the efficiency of radiation-induced DNA damage repair was calculated using equation 3:

where RE

t represents the repair efficiency at timepoint (t), γ-H2AXmax represents the maximum amount of foci observed in response to 2 Gy, γ-H2AXt the amount of foci observed at the given timepoint in response to 2 Gy.

This methodology outlines the experimental steps and analysis involved in assessing DNA damage response through immunostaining of γ-H2AX foci following 2 Gy irradiation at different time points. The repair efficiency (RE) was calculated based on the methodology outlined by Panek and Miszczyk (2019), with slight modifications to accommodate our experimental conditions [

27].

2.7. Clonogenic Survival Assay: Comparative Responses and Radiation Adaptation

The CSA was employed to evaluate the cellular responses of breast cancer cell lines (MCF-10A, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231) to the various radiation dose regimens. The conventional fractionation regimen administered a total of 8 Gy, delivered in four fractions of 2 Gy each, with a 3-hour interval between fractions. Concurrently, hypofractionated doses of 4.88 Gy, 5.23 Gy, and 5.45 Gy were given to MCF-10A, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. In addition, a prime dose of 0.5 Gy was applied at least one doubling time prior to administering the fractional doses to compare the adaptive response of the cell lines. This approach enabled the evaluation of how prior exposure to the prime dose affected initial survival rates different fractionated irradiation treatment.

2.8. Migration Assay

The migration assay was performed to examine the migratory behaviour of the MCF-10A cell line, a non-cancerous model for breast tissue. This study aims to elucidate the effects of radiation on normal breast tissue, thereby offering valuable insights into the responses of non-cancerous cells compared to their malignant counterparts. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing effective radiotherapy strategies that minimise damage to non-cancerous cells while effectively targeting tumour cells. Cells were seeded in T25 flasks at a density that ensured 100% confluence after 24 hours. The cell cultures were trypsinised and cell suspensions were prepared and added to each well of the Culture-Insert 2 Well (Culture-Insert 2 Well ibidi® GmbH, Catalogue number: 80209-150, ibidi®, GmbH). After confluence was reached, each insert was carefully removed, and non-attached cells and debris were washed away with cell-free medium. Fresh cell culture medium was then added before irradiation.

Irradiation was administered at a dose of 2 Gy per fraction, totalling 8 Gy delivered in 4 fractions with a 3-hour interval between each conventional fractionation. For the HF approach, a single dose of 4.88 Gy was applied. The doses for both fractionation schemes were to yield a biologically effective dose (BED) of 14.41 Gy, allowing for a comparative analysis of the effects on cell migration under different radiotherapy regimens. Following irradiation, cells were monitored using the CytoSMART™ System, a compact live cell imaging system acquired from Lonza, (supplied locally by Whitehead Scientific), which enables time-lapse observation every 4 hours without disturbing the cultures. Images were captured at regular intervals with a 10x objective lens and analysed using ImageJ software (Version 1.54i) to quantify cell migration dynamics. The change in the area left by the removed insert over time was plotted, and linear regression analysis was conducted to calculate the slope of the linear phase, representing the migration speed of the cells.

2.9. Invasion Assay

The invasion assay is a crucial tool in cancer research for assessing the invasive potential of tumour cells, mimicking the intricate process of cancer metastasis [

23]. This assay provides insights into the molecular and cellular determinants of tumour invasion. The transwell invasion assay was employed to investigate the invasive properties of breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231), using Geltrex® (catalogue number: A1413202), obtained from LTC Tech South Africa (Pty) Ltd, as a substrate. The assay was performed per the manufacturer’s instructions, involving preparation, staining, and quantification. Briefly, irradiated cells were treated with a total dose of 8.00 Gy in four fractions for both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, with each fraction delivered at 2.00 Gy and a 3-hour gap between fractions, while in the hypofractionation scheme, cells received single doses of 5.23 and 5.45 Gy, respectively (i.e. the BED of 11.90 and 10.95 Gy respectively), before being added to the upper chamber, while complete media with 10% FBS was added to the lower well. The insert (LTC Tech South Africa Pty LTD, catalogue number 140640) was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. After incubation, the insert was removed, washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and stained with Crystal Violet. Invaded cells were quantified at 10x magnification using the CytoSMART Lux 10 imaging system (Lonza, Basel, supplied locally by Whitehead Scientific) and expressed as a percentage of the total number of seeded cells.

2.10. Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay

The LDH assay, a well-established method for evaluating cellular health, was utilised to assess cytotoxicity by quantifying the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme into the culture supernatant. LDH, a ubiquitous cytoplasmic enzyme, serves as an indicator of cellular damage when detected extracellularly [

23]. The LDH-Cytox Assay Kit (Biocom Africa, Catalogue: 426401) was employed following the manufacturer's instructions, which included careful cell preparation and incubation with test substances. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines, along with the non-cancerous MCF-10A cell line, were cultured in complete growth medium under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2) and prepared at a concentration of 5 × 10

5 cells/ml. A total of 500,000 cells were irradiated in suspension prior to seeding into a flat-bottom 96-well plate. These cells were then subjected to either conventional fractionation (2.00 Gy × 4 fractions for a total of 8.00 Gy with a 3-hour inter-fractional interval) or hypofractionation (single doses of 4.88 Gy for MCF-10A, 5.45 Gy for MDA-MB-231, and 5.23 Gy for MCF-7). Following irradiation, the cells were allowed to recover in the incubator for 24 hours. After the recovery period, lysis buffer (600 μL) was added to the designated high-control wells to induce lysis, while low control wells remained untreated. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Subsequently, the LDH levels in the cell culture supernatant were measured. The assay mixture was prepared as per the instructions of the assay kit, and 100 µL of the reaction solution was added to each well containing the supernatant. The plate was incubated at room temperature for an additional 30 minutes to allow the reaction to develop. Finally, absorbance was recorded at 490 nm using a microplate reader (Berthold Technologies, Version 2.2.2.1).

2.11. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted meticulously to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results. This study aimed to compare the responses of various cell lines to two radiotherapy techniques: conventional fractionation and hypofractionation. Multiple assays were performed to assess the effects of these radiotherapy methods on breast cell lines in vitro. Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office Standard 2019) was utilised for initial data organisation and basic statistical analysis. Means and standard deviations for each experimental condition were calculated to describe the variability in cell responses, with standard deviation derived from the formula that quantifies the dispersion of data points around the mean.

Logarithmic plots were generated using GraphPad Prism (version 10.0.0 for Windows), with the radiation dose plotted on the x-axis and the survival fraction on the y-axis. To analyse the cell survival data, nonlinear regression analysis was performed using the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm in GraphPad Prism. This approach facilitated the fitting of survival curves to the LQ model, effectively modelling the relationship between radiation dose and cell survival. During this analysis, the estimated parameters (α and β) were derived, providing critical insights into the cellular responses to radiation exposure. The α and β values obtained from the survival curves were compared across the various cell lines. Statistical analyses were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess differences among the different fractionation conditions. For all statistical tests, p-values were calculated to assess the significance of the observed differences. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated that the differences in radiation response metrics among the treatment conditions were unlikely to have occurred by chance, thereby allowing for meaningful conclusions regarding the effects of conventional versus hypofractionation radiotherapy.

4. Discussion

The evaluation of radiosensitivity provides insight into how various breast cell lines respond to differing radiation doses and treatment regimens, which can significantly affect therapeutic outcomes. The clonogenic survival assay (CSA) was employed to determine the α/β ratios of different breast cell lines, specifically MCF-10A, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231. The order of radiosensitivity identified was as follows: MDA-MB-231 exhibited the greatest sensitivity, followed by MCF-7, and MCF-10A, which showed a lower total sensitivity in a clinical context due to its characteristics as a normal breast cell line. MCF-10A had a lower α/β ratio of 2.5 ± 0.3 Gy, while the ratios for MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were 4.1 ± 1.1 and 5.4 ± 1.7 Gy, respectively. Importantly, the larger β component of 0.08 Gy

-2, as indicated in

Table 2, suggests that MCF-10A cells recover more effectively from radiation damage compared to cancerous cell lines. This implies that while higher doses in a hypofractionated regimen may cause significant initial damage to normal tissues, they also allow sufficient time for recovery between treatment sessions. Consequently, hypofractionation can be advantageous as it takes advantage of the superior repair capacity of normal tissues relative to the more radiation-sensitive tumour tissues that may not recover as efficiently. There is substantial documentation regarding the variability in radiosensitivity among breast cancer cell lines [

11,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. This heterogeneity is critical to consider when developing personalised treatment protocols, as patient responses to radiation can differ vastly based on the specific characteristics of their tumours. For example, studies by Savoca et al. (2020) and Pereira et al. (2021) presented conflicting findings regarding the radiosensitivity of MDA-MB-231 (triple-negative, lacking estrogen and progesterone receptors, as well as HER2) and MCF-7 (ER-positive and PR-positive, HER2-negative) cell lines [

29,

30]. These discrepancies highlight the need for a detailed understanding of individual tumour biology in clinical applications.

While the prevalent reported α/β value for breast cells hovers around 4 Gy (van Leeuwen et al. 2018), this discrepancy is corroborated by other literature suggesting heightened sensitivities of breast cancer cells to dose variations [

33,

34,

35]. Such insights emphasise the potential necessity of recalibrating treatment strategies to account for varying cellular responses to radiation. Furthermore, the selection of accurate LQ parameters (α, β, and α/β) is crucial for making reliable predictions about radiation responses. Many factors, including tumour site, histology, and genetic background, contribute to significant heterogeneity in LQ parameters [

36,

37]. This variability necessitates a careful consideration of individual biological factors in clinical settings where LQ models are employed for treatment planning. When comparing the α and β values among cell lines, the results show that the cancerous cell lines possessed lower α values than the non-cancerous MCF-10A cells. Specifically, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 had α values of 0.16 Gy

−1 and 0.15 Gy

−1, respectively, compared to a higher value of 0.19 Gy

−1 for MCF-10A cells. Lower α values indicate that cancerous cells have reduced intrinsic sensitivity to radiation. Moreover, the higher β value observed in the non-cancerous MCF-10A cells is indicative of enhanced repair mechanisms, suggesting a potential for greater therapeutic gain when targeting cancer cells with fractionated doses. This observation implies that the cancer cell lines may respond differently to varying doses of radiation, with potentially heightened susceptibility to fractionated treatments, which could be advantageous in therapeutic designs that exploit these differences.

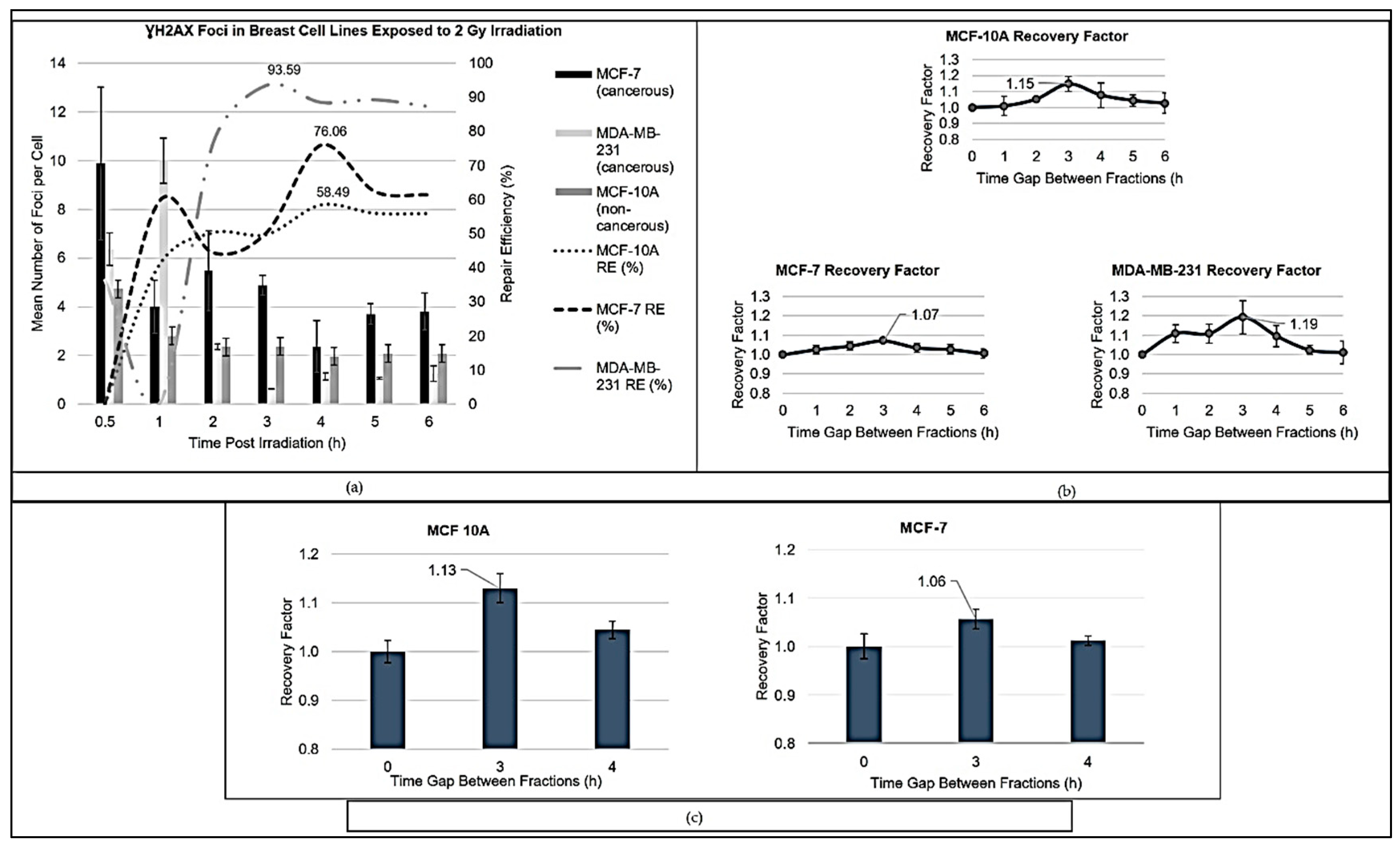

The relative sensitivity (RS) of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells was below 1, underscoring their decreased sensitivity to radiation. This lower radiosensitivity could be attributed to differences in the shoulder region of the survival curves, where lower α/β ratios yield a more gradual decrease in survival following irradiation. Such subtleties in cell-line responses have vital implications for structuring tailored treatment regimens aimed at maximising tumour control while protecting normal tissues. A comprehensive assessment of repair dynamics following irradiation revealed distinct patterns across the breast cell lines. MCF-10A exhibited steady increases in repair efficiency, while MCF-7 demonstrated a biphasic response, and MDA-MB-231 displayed a rapid escalation in repair effectiveness, as observed in

Figure 1a. These differences speak to the underlying molecular pathways that govern cellular responses to radiation and stress the need for additional research. Factors involved in DNA repair, such as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination repair (HRR), likely contribute to the observed dynamics of radiosensitivity and adaptive responses in breast cell lines. For instance, MCF-7 cells show a biphasic repair kinetics profile, initially characterised by a rapid increase in error-prone NHEJ activity followed by a transition to more accurate HRR pathways, emphasising the delicate balance between these mechanisms in maintaining genomic stability [

38]. In contrast, MCF-10A non-cancerous cells exhibit a steady increase in repair efficiency, which, while aligned with findings of elevated HRR levels in breast cancer cells, illustrates the complex interplay between repair pathways in both healthy and malignant cells [

39]. Similarly, MDA-MB-231 cells display an initial decline in repair efficiency, indicative of delayed repair responses, followed by a surge, demonstrating their adaptability to DNA damage. Furthermore, HRR and alternative NHEJ show strong cell-cycle dependency and are likely to benefit from radiation therapy-mediated redistribution of tumour cells throughout the cell cycle [

40]. Understanding these intricate repair dynamics reinforces the critical need for individualised treatment approaches. While hypofractionation presents a promising strategy to exploit the vulnerabilities of cancer cells, its effectiveness will likely depend on the specific cellular responses observed across different breast cancer phenotypes.

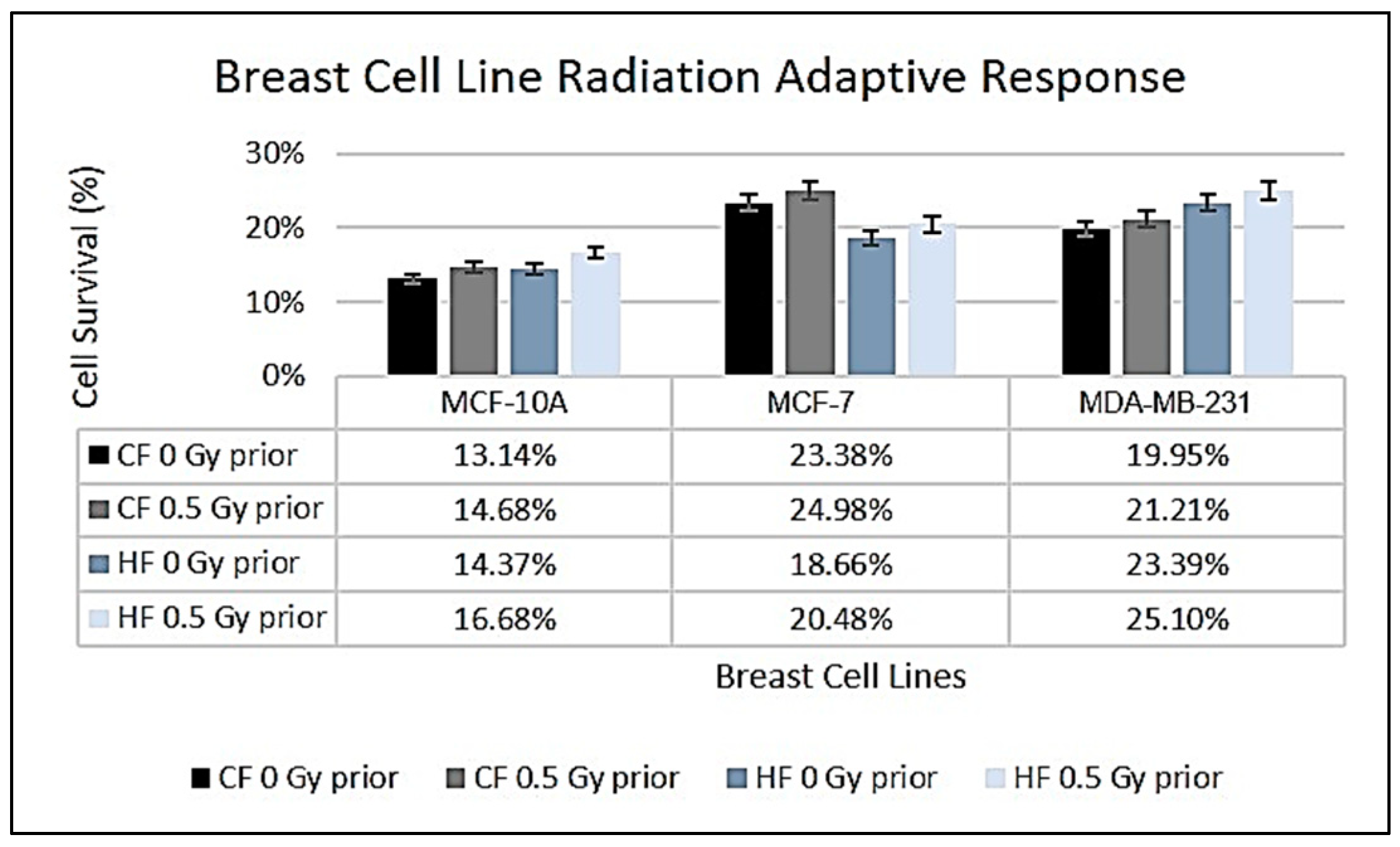

Examining the impact of HFRT on non-cancerous MCF-10A cells versus cancerous MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 lines further illustrates these concepts (

Figure 2). The non-cancerous MCF-10A cells showed a slight increase in survival under HF (14.37%) compared to CF (13.14%), although this difference was not statistically significant (

p = 0.497). The resilience observed in MCF-10A cells may be attributed to their intact DNA repair mechanisms and wild-type p53 status, which are critical for maintaining genomic stability [

41,

42]. In contrast, the cancerous MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines displayed considerable differences in survival rates between CF and HF regimens. MCF-7 exhibited a survival fraction of 23.38% under CF, which decreased to 18.66% under HF. The receptor status of MCF-7 (oestrogen receptor-positive and progesterone receptor-positive) likely influences this response to radiation, whereby hormonal signalling may modulate survival and stress responses initiated by increased radiation doses [

43]. Notably, MDA-MB-231 cells—being a triple-negative breast cancer line—demonstrated increased survival under HF (23.39%) compared to CF (19.95%). Their lack of hormone receptors and presence of mutant p53 contribute to a more aggressive phenotype, enabling them to rely on alternative repair mechanisms under HF [

44,

45]. The observed enhanced survival of MDA-MB-231 cells under HF may also facilitate interactions with immune responses, complicating treatment outcomes [

46].

The adaptive responses of breast cell lines MCF-10A, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 to low-dose radiation exposure were assessed following a priming dose of 0.5 Gy. Analysis revealed that all cell lines exhibited delays in cell proliferation, with MCF-10A experiencing a 13.2% increase, MCF-7 an 18.5% rise, and MDA-MB-231 an 11.1% increase in doubling times. Notably, the MCF-7 line exhibited the most significant delay in proliferation, possibly linked to their robust DNA repair mechanisms. According to Jabbari et al. (2019), MCF-7 cells release vascular endothelial growth factor A into the growth media instead of utilising it for growth, contributing to the observed delay in proliferation [

47]. This delay aligns with the concept of cell cycle arrest, which allows cells sufficient time to repair radiation-induced DNA damage. MCF-7 cells appear to display characteristics of senescence, as noted by Karimi-Busheri et al. (2010), providing a protective mechanism against genetic alterations [

48]. The adaptive responses across all three cell lines, illustrated in the study, emphasise the interplay between DNA damage repair pathways and cellular proliferation dynamics. All cell lines presented increases in survival rates following exposure to the priming dose of radiation, with notable survival increases for MCF-10A under hypofractionation. These findings highlight varying degrees of adaptive responses shaped by cell type and radiation exposure, underscoring the importance of these mechanisms in influencing radiotherapy outcomes [

49,

50].

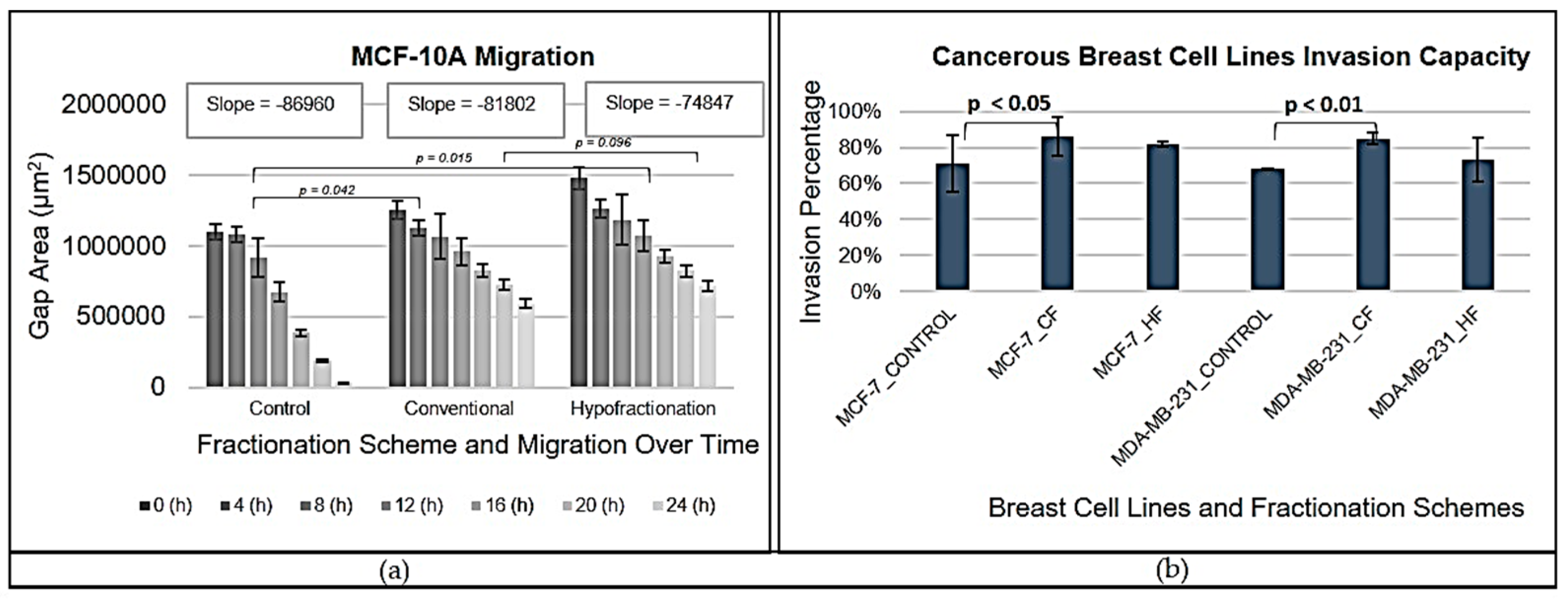

The migration capabilities of MCF-10A cells illuminated how radiation therapy affects cell motility. Unirradiated cells exhibited the steepest slope in gap closure curves, indicating the highest migration speed, which is consistent with previous studies suggesting untreated cells maintain unrestricted migratory capabilities [

51]. Conversely, both CF and HF treatments resulted in shallower slopes, indicating a reduction in migration speed due to radiation exposure. This finding mirrors observations in other cancer types, where radiation may inhibit motility and simultaneously promote proliferation [

52,

53].

There was no statistically significant difference in migration rates between CF and HF (

p = 0.096), indicating that both regimens possess similar inhibitory effects on migration. However, these rates were significantly slower than those compared to the control conditions (

p < 0.042 for CF and

p = 0.015 for HF). The observed reduction in motility may be primarily attributed to the cytotoxic effects of radiation, rather than changes in the extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness, highlighting the necessity for further exploration of these underlying mechanisms [

54]. Invasion assays conducted on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines provided critical insights regarding the effects of radiation therapy on cellular invasiveness. Results indicated that irradiated cells typically exhibit enhanced invasion irrespective of the fractionation regimen employed. Notably, CF treatments generally produced the highest invasion rates across both cell lines, implying that radiation-induced cellular stress may encourage invasive behaviour. Statistical analyses indicated no significant difference in invasion between CF and HF regimens; however, clear trends suggest that the pronounced responses of both cell lines to CF warrant further investigation into the distinct adaptations driven by their molecular profiles. MCF-7 cells, with hormone receptor positivity and intact p53 function, may benefit from enhanced DNA repair mechanisms, enhancing their survival under CF [

43]. In stark contrast, MDA-MB-231 cells, characterised by mutant p53 and being triple-negative, endure reduced survival rates post-radiation but maintain a trend toward increased invasiveness. These findings suggest a potential role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in radiation-induced invasion. Alterations in EMT marker expression may contribute significantly to the observed behaviour in irradiated cells [

55]. Additionally, changes in Rho-GTPase activity, linked to cytoskeletal rearrangements, may facilitate increased invasion following radiation [

56].

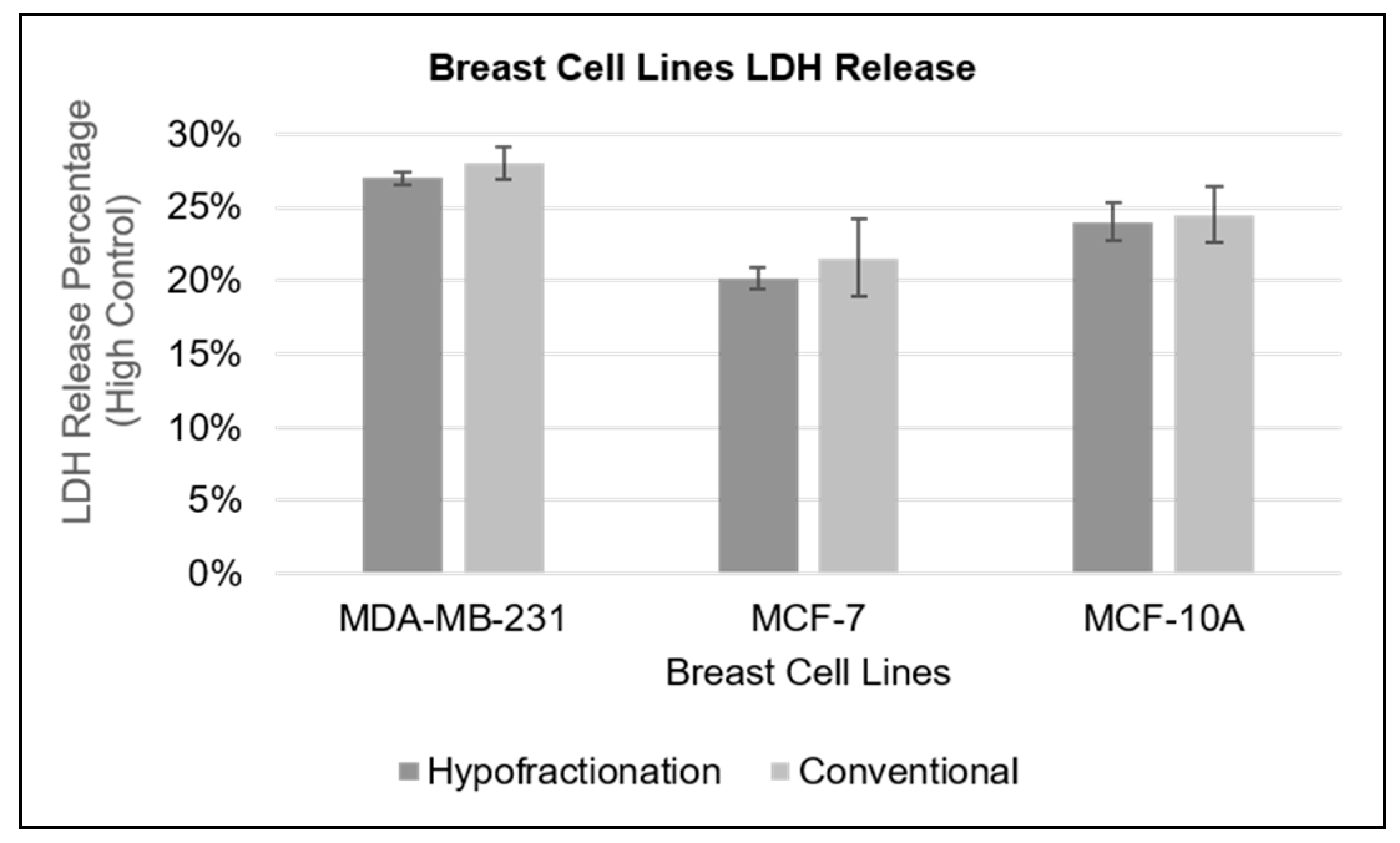

Overall, these data indicate that while CF may escalate invasiveness—particularly in hormone receptor-negative MDA-MB-231 cells—it concurrently compromises survival. Conversely, MCF-7 cells, despite exhibiting higher survival rates under CF, do not demonstrate a notable increase in invasiveness. This divergence underscores the complex relationship between invasion capacity, cell survival, and treatment regimens, suggesting that hypofractionation represents a more balanced approach for minimising invasiveness in hormone receptor-negative breast cancer while preserving cell viability in hormone receptor-positive cells. Continued exploration into the underlying mechanisms driving these adaptive responses is necessary to optimise radiation therapy strategies for improved patient outcomes. The study's findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the radiosensitivity of various breast cell lines, revealing a complex interplay between radiation response, adaptive mechanisms, and cellular behaviours. The differences highlighted among MCF-10A, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells underscore the importance of personalised treatment approaches, particularly in tailoring radiation therapies. Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular processes underpinning these differences and refining treatment protocols to enhance clinical efficacy tailored to individual patient needs. Such efforts will ultimately advance our capacity to improve outcomes in breast cancer therapy, making strides toward personalised oncology.

5. Conclusions

Breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer diagnosed globally among women, with a significant burden on healthcare systems, particularly in resource-constrained settings. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing disparities in cancer care, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment for many patients. Such delays can contribute to advanced-stage diagnoses and poorer treatment outcomes. It is within this context that the need for effective and personalised treatment strategies, particularly in radiotherapy, has become ever more urgent. This study highlights the critical importance of personalising radiotherapy strategies in breast cancer treatment, especially given the distinct cellular responses observed across different breast cancer sub-types. The findings indicate that HF may be particularly advantageous for patients with hormone-receptor positive breast cancers. This approach preserves non-cancerous tissues while effectively targeting malignant cells, thus minimising long-term side effects associated with radiation therapy.

Conversely, CF seems to be more effective for managing TNBC, known for its aggressive nature. The data revealed that aggressive cancer sub-types, such as TNBC, may not respond as favourably to hypofractionation, underscoring the necessity for tailored treatment modalities that consider the specific features and behaviours of each cancer type. The in vitro evidence elucidates the differential sensitivity of hormone-receptor positive and TNBC cell lines to radiation, reinforcing the importance of developing personalised radiation therapy pathways. This is vital for optimising treatment effectiveness and achieving favourable patient outcomes. The study advocates for the broader implementation of personalised radiotherapy approaches, recommending hypofractionated regimens for hormone-receptor positive breast cancers and conventionally fractionated therapy for more aggressive variants.

Furthermore, the findings emphasise the urgent need for additional research to validate these in vitro results within in vivo settings. Establishing robust, evidence-based guidelines for radiation therapy in breast cancer will be essential for enhancing overall treatment effectiveness while mitigating adverse effects. In a landscape shaped by both the prevalence of breast cancer and the challenges posed by the pandemic, a tailored approach to radiotherapy not only optimises patient outcomes but also addresses the complexities inherent in treating diverse cancer types. By refining treatment strategies, healthcare providers can improve care quality and enhance the quality of life for breast cancer patients navigating their journeys amidst ongoing challenges.