1. Introduction

An increased resting heart rate (RHR) has long been associated with a higher incidence of heart failure (HF) in both healthy women and men. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study demonstrated a graded association between RHR and the risk of developing HF in apparently healthy individuals, indicating that elevated RHR is a significant risk factor for HF [

1]. This association remained strong even after multivariable adjustments for various covariates, suggesting that RHR is crucial in predicting HF in men. However, the same study did not observe a similar relationship in women, which raises the question of whether the prognostic value of RHR may differ by gender. Similarly, the Rotterdam Study also found an association between RHR and HF in men but not in women, particularly after excluding patients taking heart rate-modifying medications [

2].

In contrast, the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) established a graded relationship between RHR and the risk of developing HF in both healthy women and men. The study further reinforced the idea that baseline RHR serves as a critical predictor of both HF and cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality, emphasizing its importance as a prognostic tool [

3]. A more recent study in a Chinese population identified a J-shaped association between RHR and HF risk, indicating that very low and very high RHR values are linked to an increased risk of HF [

4]. This nuanced finding underscores the complexity of the relationship between RHR and HF across different populations and suggests that RHR may have differing implications for HF risk in diverse racial and ethnic groups.

An insidious onset and progressive deterioration of cardiac function characterize heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). In the early stages, patients with HFrEF are often asymptomatic, which makes early diagnosis and intervention difficult. Over time, as cardiac function declines, patients develop symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance. This progressive decline in cardiac function is often accompanied by a compensatory increase in heart rate, driven by the activation of neurohormonal systems, primarily the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [

5]. These systems are activated in an attempt to maintain cardiac output and meet the body’s increasing demands. However, as the heart’s ability to pump blood effectively deteriorates, the compensatory mechanisms become overwhelmed, leading to worsening symptoms and eventually to clinical heart failure.

The current standard of care for patients with HFrEF revolves around inhibiting neurohormonal systems to prevent further deterioration of cardiac function [

6]. Beta-blockers, which work by blocking the effects of the sympathetic nervous system, have become a cornerstone of HFrEF therapy. Clinical trials have demonstrated that beta-blockers improve survival rates and reduce hospitalizations in patients with HFrEF [

7]. However, these trials have primarily included male patients and the data on women have been limited. This gender imbalance in clinical trials has raised concerns that the results may not be adequately powered to detect the specific benefits or risks for female patients. As a result, the safety and efficacy of specific treatments, such as beta-blockers, may not be fully understood in women, potentially leading to suboptimal care for female patients with HFrEF [

8].

Elevated RHR in HFrEF patients is a well-established predictor of higher mortality and poor clinical outcomes, making it a critical focus in HF management [

9]. Reducing RHR to approximately 60 beats per minute (bpm) has become a common therapeutic goal in managing HFrEF, as it has been associated with improved survival and reduced hospitalization rates. However, the target RHR may not be the same for women as it is for men, primarily due to the underrepresentation of women in randomized controlled trials. The physiological response to treatment, including heart rate reduction, may differ between men and women, and women may not need as significant a reduction in RHR to achieve optimal outcomes.

Gender disparities in the impact of RHR on HF outcomes may influence the management of HFrEF. While the relationship between elevated RHR and increased mortality in men with HFrEF is well-established, the effects of RHR on mortality and other prognostic factors in women remain less clear. While men typically have a target RHR of 60 bpm for managing HFrEF, women may not require such a drastic reduction in RHR. Moreover, women with HFrEF in sinus rhythm may experience different outcomes and have different predictors of mortality associated with RHR compared to their male counterparts. The existing literature has not fully explored these potential gender-specific differences in RHR’s effects on HFrEF outcomes, particularly in women.

This study investigated gender-specific differences in the effects of RHR targets on HF outcomes, including mortality predictors, in patients with HFrEF. By exploring how RHR affects women differently from men, the goal is to develop more personalized and effective treatment strategies for female patients with HFrEF. The findings from this research could help refine treatment protocols and ultimately lead to improved care and clinical outcomes for women, ensuring that female patients receive the most appropriate and effective therapies for managing their condition. Understanding the nuanced role of RHR in female HFrEF patients is crucial for advancing gender-tailored treatment approaches in heart failure care.

2. Materials and Methods

From February 2017 to January 2022, we evaluated the impact of RHR on all causes of death. We identified predictors of death in women and men with HFrEF in sinus rhythm, defined as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%. The study included patients diagnosed with HF based on the Framingham criteria for HF diagnosis and echocardiographic measurements. Baseline data encompassed various clinical characteristics and echocardiographic parameters. Clinical characteristics analyzed were age, body mass index (BMI), the prevalence of comorbidities, and the number of HF hospitalizations. The comorbidities examined were diabetes (defined as glycemia ≥126 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin > 6.5% or under hypoglycemic drug), significant chronic kidney disease (CKD) (defined as creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL), myocardial infarction, and stroke. Echocardiographic data included LVEF and left ventricular diastolic diameters (LVDD) at baseline and the end of the study.

The study’s primary outcome was that RHR related all causes of death in patients with HFrEF in sinus rhythm. We stratified the RHR into two groups: ≤60 beats per minute (bpm) and >60 bpm, and ≤70 bpm and >70 bpm. Subsequently, within each of these RHR groups, we conducted a comparative analysis between women and men. This analysis examined RHR-related differences in demographic characteristics, clinical profiles, and echocardiographic findings. We aimed to identify any sex-specific variations of RHR on death rates and the main prognostic predictors. Mortality data were obtained from the patient’s medical records or through the individual registration status on the Federal Revenue’s website [

10]. Our approach allowed us to discern whether the impact of RHR on all causes of death differed between women and men with HFrEF in sinus rhythm. The HR values used were the closest to the end of the follow-up period (January 2022) or the death event. The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CAPpesq) of the Hospital das Clinicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Sao Paulo (nº 4.436.791). Statistical analysis was conducted by presenting continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The normality of the data was assessed using the Equality of Variances test. Continuous variables were compared between groups using Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA), while the chi-square test was employed for categorical variables. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided probability value of <0.05. Multiple imputation was used to impute missing baseline and follow-up LVDD values and final LVEF. Multiple imputations used the MCMC method to deal with missing data. The imputed datasets were analyzed separately and combined to produce a single result, considering the uncertainty caused by missing data. The cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier (K-M) method with Šidák adjustment for multiple comparisons p values. Cox proportional hazard models were applied to identify variables independently associated with all-cause mortality. The chi-square score of the Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the most robust predictors of mortality. The dependent variables in the Cox model were death, and covariates included those with a p-value <0.25, such as age, gender, BMI, baseline LVEF, and final HF. Statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS

® Studio software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

We analyzed a cohort of 2,984 patients, with a mean age of 61 ± 13.8 years, comprising 1,922 (64.4%) male participants. Baseline characteristics, including age, BMI, history of MI, diabetes, CKD, stroke, beta-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), hydrochlorothiazide, carvedilol dosage, hospitalization rates, basal LVEF, pacemaker and CRT implantation, and transplant were comparable between women and men. Spironolactone and furosemide use were higher in women. IDC implantation, CABG, and PCI were higher in men. Final LVEF was higher (38 ± 13.4 vs. 36.7 ± 12.9%; p = 0.016), and basal (63.3 ± 7.9 vs. 65.4 ± 8.7 mm; p < 0.001) and final (61.2 ± 9.9 vs. 63.1 ± 10.6 mm; p < 0.001) LVDD were lower in women. Throughout the follow-up period, which averaged 3.7 ± 1.6 years, we observed an increase in LVEF and a decrease in LVDD in women and men. (

Table 1)

Table 2 presents RHR categorized by RHR in ≤ 60 > bpm and ≤ 70 > bpm. Basal LVDD was lower in patients with RHR > 60 bpm than those with HR ≤ 60 bpm (66.2 ± 8.7 mm vs. 64.6 ± 8.5 bpm; p = 0.041). Among the patients studied, only 4.1% achieved an RHR of ≤ 60 bpm while taking a mean daily dosage of 42.4 ± 15.2 mg of carvedilol, and 42.5% achieved an RHR of ≤ 70 bpm with 40.8±16.2 mg. Throughout the follow-up period, we observed a higher death incidence in patients with RHR > 70 bpm compared with RHR ≤ 70 bpm (42,8% vs. 39.1%; p = 0.044) and an increase in final LVEF for patients with RHR ≤60> and ≤70>.

Table 3 presents data for RHR categorized by sex and ≤ 60 bpm and > 60 bpm. RHR was similar between women and men in each categorized group. Age was higher in women with RHR ≤ 60 bpm compared to RHR > 60 bpm (65±11.9 vs. 58.4±13.5 years; p = 0.011). Women with RHR > 60 bpm had higher final LVEF and lower basal and final LVDD. Spironolactone and furosemide use were higher in women with RHR > 60 bpm. The incidence of death was higher in men with RHR > 60 bpm. There was a significant increase in final LVEF compared to basal LVEF among male and female patients with RHR ≤ 60 bpm and > 60 bpm.

Table 4 presents data for RHR categorized by sex and ≤ 70 bpm and > 70 bpm. RHR was similar between women and men in each categorized group. Women with RHR ≤ 70 bpm had higher final LVEF. Basal and final LVDD were lower in women with RHR ≤ 70 bpm and > 70 bpm. Spironolactone use was higher in women with RHR > 70 bpm. CABG, PCI, and ICD implantation were higher in men, and pacemaker implantation was higher in women with RHR ≤ 70 bpm. Spironolactone use and CRT implantation were higher in women. The incidence of death was marginally higher in men with RHR ≤ 70 bpm (p = 0.095) and significantly higher in men with RHR > 70 bpm (p = 0.001).

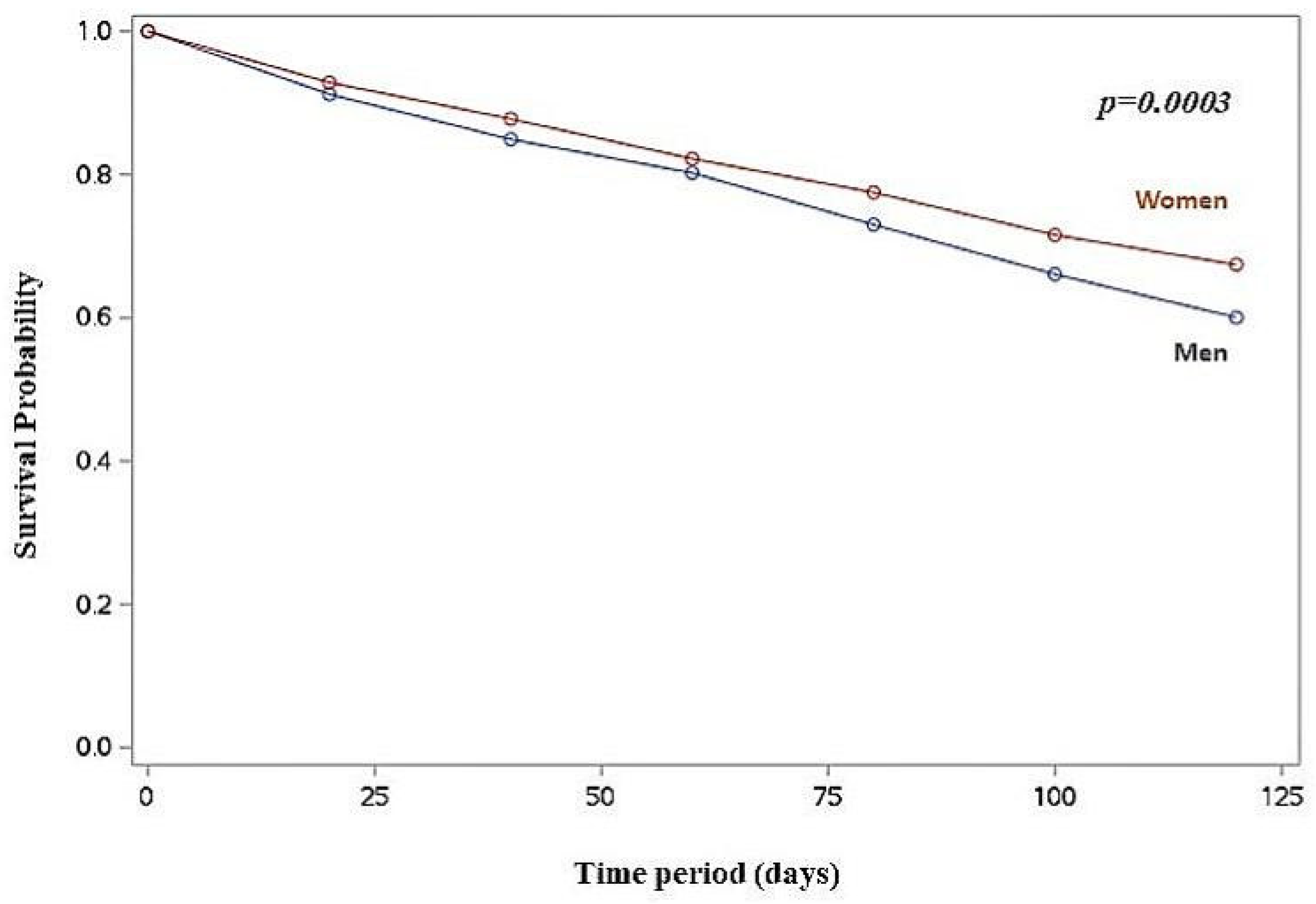

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed a higher cumulative death incidence in men compared to women (log-rank p < 0.001) (

Figure 1), and in men with RHR >60 bpm (log-rank p < 0.001) and RHR >70 bpm (log-rank p = 0.002) compared to women.

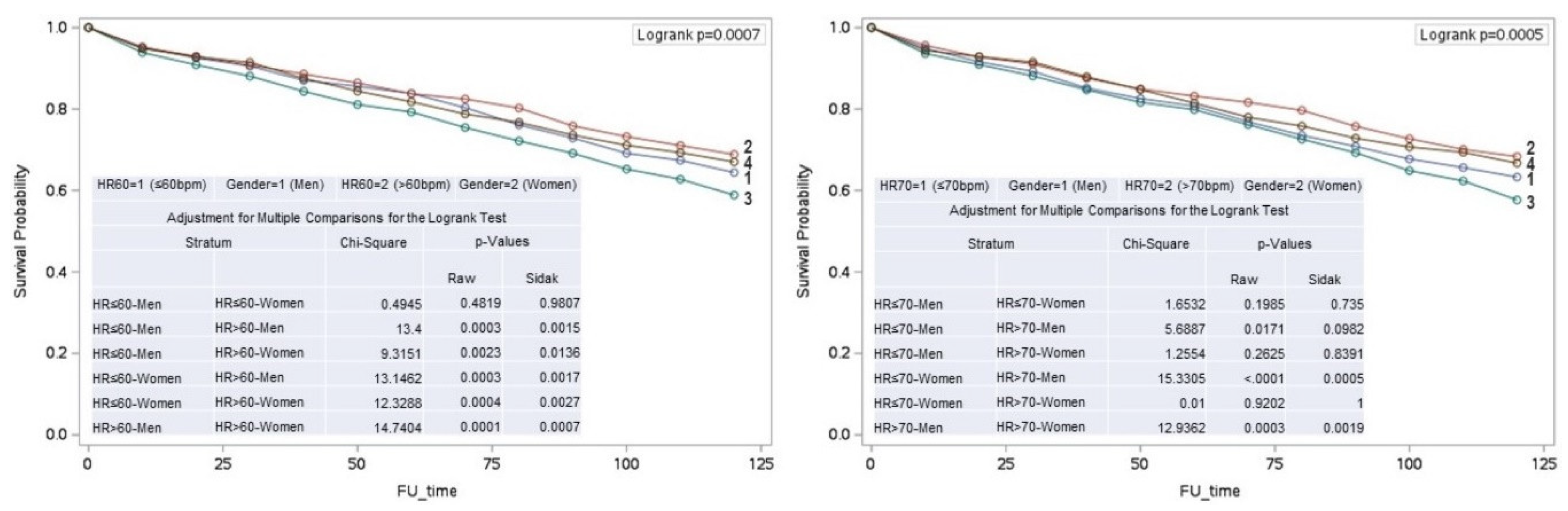

In men, an RHR > 60 bpm was associated with increased mortality compared to those with an RHR of ≤ 60 bpm (p = 0.001). Conversely, in women, mortality was higher in those with an RHR of ≤ 60 bpm compared to those with an RHR of > 60 bpm (p = 0.003). (

Figure 2)

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, adjusted for covariates with p < 0.25, identified age (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.008-1.017; p < 0.001), men (HR = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.71-0.90; p < 0.001), LVEF (HR = 0.986; 95% CI: 0.98-0.99; p = 0.001), and RHR (HR = 1.005; 95% CI: 1.00-1.01; p = 0.025) as independent death predictors. Further stratified Cox proportional hazards regression analysis indicated that age (HR = 1.01; 95% CI: 1.01-1.02; p = 0.002), LVEF (HR = 0.98; 95% CI: 0.97-0.99; p = 0.001), and RHR (HR = 1.008; 95% CI: 1.00-1.01; p = 0.008) were significant independent death predictors in men. For women, age emerged as the only significant predictor (HR = 1.02; 95% CI: 1.01-1.02; p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the association between RHR and all-cause mortality in a cohort of 2,984 patients. The results revealed sex differences in mortality rates and their predictors. Men with an elevated RHR (>60 bpm) exhibited higher mortality rates compared to women. Interestingly, women with an elevated RHR (>60 or >70 bpm) had lower mortality rates than men, highlighting potential differences in the prognostic significance of RHR between sexes.

Our cohort’s baseline clinical and echocardiographic characteristics, including age, BMI, history of MI, diabetes, CKD, stroke, carvedilol dosage, hospitalization rates, and basal LVEF, were comparable between women and men. This comparability suggests that any observed differences in outcomes are less likely due to baseline disparities, thereby strengthening the reliability of our results. Additionally, it is noteworthy that while women and men started with similar baseline characteristics, the progression and outcomes showed distinct patterns influenced by sex.

The EPIC-Norfolk study demonstrated distinct patterns in HF incidence related to RHR in apparently healthy subjects. In the overall population, HF incidence was higher for individuals with an RHR exceeding 80 bpm. Among men, a higher HF incidence was observed beginning earlier at an RHR of 71 bpm, whereas, for women, the HF incidence was more significant in the RHR of 81 to 90 bpm range when adjusted only for age. However, after applying a multivariate adjustment, the HF incidence was higher for an RHR between 81 and 90 bpm, with similar rates observed in both women and men [

1]. Other studies also showed the relationship between higher RHR and HF incidence. However, specific studies of the RHR influence in women and men with HFrEF are scarce.

Our study found that age, LVEF, and RHR were independent variables for death in men with HFrEF in sinus rhythm. In contrast, age was the only independent variable for women. The finding that RHR was a significant predictor of mortality in men but not in women suggests that interventions aimed at reducing RHR may need to be more aggressively pursued in men. On the other hand, the fact that age was the only significant predictor for women highlights the importance of focusing on age-related comorbidities and possibly different therapeutic RHR targets in female patients. We know that aging is one of the most significant factors associated with a higher incidence of heart failure. Despite population aging, the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 reported a substantial reduction in the primary diseases causing heart failure, such as ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, and myocarditis, except for hypertensive heart disease, which increased from 2007 to 2017 [

11]. A UK population-based study in models standardized for age and sex also showed a decrease in the incidence of heart failure from 2002 to 2014 [

12]. This overall decline was consistent across most age groups, except those with ≥ 85 years. However, a population-based study conducted in the United States revealed a reversal in HF mortality trends, showing an increased death rate among both women and men after 2012 [

13]. A key limitation of the study is its reliance on death certificate data, which may incorrectly attribute some deaths, particularly in cases where HF symptoms are similar to those of other conditions.

The sex differences in mortality observed in our study suggest that men with higher RHR are at a greater risk compared to their female counterparts. Although the mechanisms involved are unknown, several possible mechanisms could explain why RHR was an independent variable for HFrEF in men but not women. This could be due to biological differences, such as hormonal influences on cardiovascular function and possibly sex-specific responses to treatment and lifestyle factors [

14,

15,

16]. Women and men have different autonomic nervous system responses, with men typically exhibiting higher sympathetic and lower parasympathetic activity than women. Likewise, a recent study showed different pathophysiological pathways in women and men with HF, with more significant activity of neuro-inflammatory markers in men [

17]. This higher neurohumoral activity could be associated with more significant myocardial dysfunction, sympathetic activity, and RHR, and, consequently, worse prognosis in men with HFrEF. However, studies revealed conflicting results, showing that women tend to have a more significant humoral immune reaction. This heightened immune response in women is modulated by the attenuating effects of endogenous estrogen [

18,

19] Women generally exhibit higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukins (IL-6, IL-1β), and signaling proteins that mediate and regulate immunity and inflammation. They also show increased activation of inflammatory T cells, including Th1 and Th17 cells, which are crucial in driving inflammatory responses. Pro-inflammatory gene expression is up-regulated in the female myocardium, suggesting a greater propensity for inflammatory reactions at the genetic level in heart tissue. These differences could adversely influence RHR regulation and its impact on HF development and outcome. Conversely, women might benefit from the cardioprotective effects of estrogen [

20,

21], which might mitigate the impact of a higher immune response and RHR on HF risk in women [

22].

Our findings also suggest that maintaining a lower RHR could reduce death risk, particularly among men. Clinicians should consider incorporating RHR management into the routine care of patients with HFrEF, but the best RHR in women still needs to be defined. Strategies to address age-related risk factors should also be prioritized in female patients. Additionally, the lower mortality rates in women suggest that they benefit from different or additional protective mechanisms that could be further explored to enhance treatment approaches for men.

Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. The observational design cannot establish causality, and the cohort’s specific characteristics may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the influence of unmeasured confounding factors could impact the findings. It is a retrospective study in a specialized tertiary care center where selection biases may occur, including patients with a more complex clinical picture. An adequate definition of symptoms is missing, especially dyspnea NYHA functional class, as well as other variables associated with a worse prognosis, such as ventricular arrhythmia and a 6-minute walk test. We were also unable to detail the cause of death adequately. Our analysis included cardiac and non-cardiac causes, including the deaths from COVID-19, which occurred between the pandemic months of March and September 2020. Finally, adequate information regarding drug treatment and dosages needs to be included. However, our center advocates that HF treatment be as close as possible to current guidelines, as shown by the high percentage of HF common medications in the Tables. The significant improvement in LVEF observed in our cohort also emphasizes the potential benefits of optimized medical therapy and lifestyle modifications in enhancing cardiac function over time. Additionally, the study did not explore the potential impact of hormonal status, menopausal status, or hormone replacement therapy on HF outcomes, which could be relevant factors in sex-based differences.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study underscores the significance of resting heart rate (RHR) as a predictor of mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), revealing distinct sex-specific differences. Elevated RHR appears to pose a greater risk for men, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to maintain RHR near 60 bpm. Conversely, our findings suggest that women may benefit from a slightly higher target RHR, with levels closer to 70 bpm, indicating that individualized RHR management strategies may improve outcomes based on sex.

Future research should focus on interventional strategies to optimize RHR and improve outcomes, especially in men who appear to be at higher risk. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of these sex differences could lead to more personalized and effective treatments for both men and women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.P.M.; methodology: A.P.M., A.C.P.-B., C.H.d.C.; formal analysis, A.P.M., A.C.P.-B.; investigation, A.P.M., M.E.B., G.B.M., G.S.M., C.H.d.C., S.D.A., E.A.B., A.C.P.-B.; resources, A.P.M., M.E.B., G.B.M., G.S.M., C.H.d.C., S.D.A., E.A.B., A.C.P-B.; data curation, A.P.M., A.C.P.-B., C.H.d.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.M.; writing—review and editing, A.P.M., M.E.B., G.B.M., G.S.M., C.H.d.C., S.D.A., E.A.B., A.C.P.-B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research project was approved on December 3rd, 2020, by the Research Ethics Committee (CAPpesq) of the Hospital das Clinicas da Faculdade de Medic-ina da Universidade de Sao Paulo (No. 4.436.791).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as it was a retrospective study, and the patients could not be identified.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The patients’ data were provided by José Antonio Ramos Neto and André Abreu of the Medical Information Unit of the Instituto do Coracao (InCor), Hospital das Clinicas HCFMUSP, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy; LVDD: left ventricular diastolic diameter; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

| RHR |

Resting heart rate |

| HFrEF |

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| HF |

Heart failure |

| LVEF |

Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVDD |

Left ventricular diastolic diameters |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| ACEI |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| ARB |

Angiotensin receptor blocker |

| CABG |

Coronary artery bypass graft |

| CRT |

Cardiac resynchronization therapy |

| ICD |

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| PCI |

Percutaneous coronary intervention |

References

- Pfister R, Michels G, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Resting heart rate and incident heart failure in apparently healthy men and women in the EPIC-Norfolk study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(10):1163-70.

- Nanchen D, Leening MJ, Locatelli I, Cornuz J, Kors JA, Heeringa J, et al. Resting heart rate and the risk of heart failure in healthy adults: the Rotterdam Study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:402–410.

- Ho JE, Larson MG, Ghorbani A, Cheng S, Coglianese EE, Vasan RS, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risks associated with an elevated heart rate: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000668.

- Agbor VN, Chen Y, Clarke R, Guo Y, Pei P, Lv J, et al.; China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Resting heart rate and risk of left and right heart failure in 0.5 million Chinese adults. Open Heart. 2022;9(1):e001963.

- Hartupee J, Mann DL. Neurohormonal activation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(1):30-38.

- Packer, M. Neurohormonal antagonists are preferred to an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in preventing sudden death in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(10):902–906.

- Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Parkhomenko A, Borbola J, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS). Eur Heart J. 2005;26(3):215–225.

- Shah RU, Klein L, Lloyd-Jones DM. Heart failure in women: epidemiology, biology and treatment. Womens Health (Lond). 2009;5(5):517-27.

- Weeks PA, Sieg A, Gass JA, Rajapreyar I. The role of pharmacotherapy in the prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2016;21(4):415–431.

- Brasil. Receita Federal. Brasília. 2022. Available online: https://servicos.receita.fazenda.gov.br/Servicos/CPF/ConsultaSituacao/ConsultaPublica.asp (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736-1788.

- Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Crespillo AP, et al. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):572-580.

- Sayed A, Abramov D, Fonarow GC, Mamas MA, Kobo O, Butler J, et al. Reversals in the Decline of Heart Failure Mortality in the US, 1999 to 2021. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9(6):585-589.

- Neves VF, Silva de Sá MF, Gallo L Jr, Catai AM, Martins LE, Crescêncio JC, et al. Autonomic modulation of heart rate of young and postmenopausal women undergoing estrogen therapy. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40(4):491-9.

- Rosano GM, Patrizi R, Leonardo F, Ponikowski P, Collins P, Sarrel PM, et al. Effect of estrogen replacement therapy on heart rate variability and heart rate in healthy postmenopausal women. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80(6):815-7.

- Chyou JY, Qin H, Butler J, Voors AA, Lam CSP. Sex-related similarities and differences in responses to heart failure therapies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21(7):498-516.

- Ravera A, Santema BT, de Boer RA, Anker SD, Samani NJ, Lang CC, et al. Distinct pathophysiological pathways in women and men with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(9):1532-1544.

- Bouman A, Heineman MJ, Faas MM. Sex hormones and the immune response in humans. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(4):411-23.

- Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626-38.

- Piro M, Della Bona R, Abbate A, Biasucci LM, Crea F. Sex-related differences in myocardial remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Mar 16;55(11):1057-65.

- Powell BS, Dhaher YY, Szleifer IG. Review of the Multiscale Effects of Female Sex Hormones on Matrix Metalloproteinase-Mediated Collagen Degradation. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2015;43(5-6):401-28.

- Umetani K, Singer DH, McCraty R, Atkinson M. Twenty-four hour time domain heart rate variability and heart rate: relations to age and gender over nine decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(3):593-601.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).